Oxford University Press's Blog, page 81

March 30, 2022

Five classics to read if you enjoy shows like Bridgerton or Sanditon [reading list]

“It is a truth universally acknowledged…” that there is no such thing as too many period dramas—at least, this remains true for those of us who are drawn to them, time and time again. Watching period dramas bring with them a sense of comfort as they transport the viewer to a world that is so unlike their own, where intense emotions are given space to breathe. In the same manner, reading books about such drama and emotion provides the reader an opportunity to closely reflect on how these situations relate back to real life.

With the start of the new seasons of Bridgerton and Sanditon—the former based on the book series by Julia Quinn and the latter based on Jane Austen’s last but unfinished novel of the same name—readers may find that they are drifting toward reading books, particularly classics, of the same nature where themes of love, betrayal, innocence, jealousy, and so much more are explored.

With that in mind, here are five books that we recommend you read if you enjoy shows like Bridgerton and Sanditon:

Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell, edited by Angus Easson

Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell, edited by Angus Easson

Wives and Daughters is Gaskell’s last novel that is regarded by many as her masterpiece. Subtitled as “An Every-Day Story”, the reader is presented with observations of early nineteenth-century English life—about the hierarchies, social values, and social changes—through the eyes of Molly Gibson, daughter of the doctor in the small provincial town of Hollingford. In essence, the novel is a timeless representation of human relationships and judging people for what they are, not what they seem.

Read: Wives and Daughters

Middlemarch by George Eliot, edited by David Carroll and David Russell

Middlemarch by George Eliot, edited by David Carroll and David Russell

Middlemarch is considered the greatest “state of the nation” novel as it is about living with others, about growing up, losing one’s ideals, and finding them again. Set in a fictional English Midland town, the story follows the lives of many characters whose distinct stories intersect with one another’s. The novel grapples with issues such as the status of women and the nature of marriage, and explores themes of self-interest, idealism, hypocrisy, and education.

Read: Middlemarch

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, edited by Margaret Smith, Herbert Rosengarten, and Janet Gezari.

Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, edited by Margaret Smith, Herbert Rosengarten, and Janet Gezari.Shirley is Brontë’s only historical novel and her most topical one, and it expresses Brontë’s sense of bereavement following the deaths of her three siblings. Set against the backdrop of the Luddite uprisings in the Yorkshire textile industry, Shirley is a social novel set in 1811-12 Yorkshire where the residual effects of the industrial depression due to the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 is greatly apparent.

Read: Shirley

Lorna Doone by R. D. Blackmore, edited with an introduction and notes by Sally Shuttleworth

Lorna Doone by R. D. Blackmore, edited with an introduction and notes by Sally Shuttleworth

A story set in seventeenth century rural bliss around the East Lyn Valley area of Exmoor, Lorna Doone is a tale of love and high adventure based on a group of historical characters. Sally Shuttleworth’s introduction finds a startling sub-text that rigidly defends Victorian values and portrays a “manly” hero constantly having to prove his masculinity to himself. This edition is the only critical edition of this perennially popular story.

Read: Lorna Doone

Evelina by Frances Burney, introduction by Vivien Jones and edited by Edward A. Bloom

Evelina by Frances Burney, introduction by Vivien Jones and edited by Edward A. Bloom

Evelina is Burney’s first, shortest, and most popular novel as it deals with themes still relevant today, such as the position of women in society and social ambition. This richly comic and entertaining novel delves deep into how young women navigate across the complex layers of eighteenth century society. Burney satirizes the society in which the story is set in and is a perfect read for people who enjoy the work of Jane Austen whose novels explore many of the same issues.

Read: Evelina

Featured image by Joyce McCown on Unsplash

March 29, 2022

Women’s economic empowerment, past and future [podcast]

In the western world, discussions about the gender pay gap have dominated discussions for the last few decades, but the issues around the economic status of women, and women’s roles in the workforce are far more nuanced, incorporating issues of race, class, consumerism, and ongoing shifts in the legal status of women in subtle and often invisible ways.

On today’s episode, we discussed the global and historical implications of women, work, and economic empowerment.

First, we welcomed Laura M. Argys and Susan L. Averett, the authors of Women in the Workforce: What Everyone Needs to Know, to share their research on women’s growing role in the workforce and the problems with definitively measuring the gender wage gap. We then interviewed, Laura Edwards, the author of Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States, looking at the 19th century legal status of textiles and how they provided a unique path to economic empowerment for women and people of color.

Check out Episode 70 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Women's Economic Empowerment, Past and Future – Episode 70 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about Laura Argys and Susan Averett’s work on women in the work force, please enjoy the introduction from The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, which they also edited: “Women, the Economy, and Economics”.

This article—“Labor and Gender”–from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies provides a broader global perspective on women in the global economy.

Through the end of June, you can read the introduction to Laura Edward’s Only the Clothes on Her Back, which tells the stories of Elizabeth Billings and an enslaved women, Caty, and how their rights to the clothes they wore provided them a narrow claim to property.

For further context on women’s economic status in 17th and 18th Century America, please enjoy this article from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia, “Women in Early American Economy”.

Featured image: Couturières bretonnes ou Atelier de couture (1854) by Jean-Baptiste Jules Trayer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Brexit referendum, five years on: can future generations “rebuild Europe”?

Five years ago today, the British government “triggered” (an apt term in the circumstances) Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon which permitted any member state to secede from the European Union “in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.” Five years of bitter, muddled wrangling later, Britain has finally departed from the Union, the first—and most in Europe hope the only—state to do so. Britain had, of course, never really ever been a part of Europe—not at least of the Europe which ever since 1951 has been edging itself steadily, if often in Jean Monnet’s words “by stealth,” towards a species of con-federal state, a “United States of Europe.” “We are with Europe,” as Winston Churchill said firmly in 1930, “but not of it. We are linked but not compromised. We are interested and associated but not absorbed.”

And so, it has been ever since. The economic impact of Brexit, although severe, has not been so dire as most “remainers” had predicted, and perhaps hoped. Britain seems to be prepared to co-operate with its European neighbours—what choice does it have?—even while it struggles, as the crisis in Ukraine continues to show all too clearly, to re-assert itself as an independent regional power, if no longer a global one. But it has certainly brought no obvious benefits, nor is it likely to, in particular for the younger generations who were given no say in matter.

“If the EU is finally to become ‘the model for new world order,’ it still needs to do more.”

The future for Europe, by contrast, seems in many respects far brighter than it was in 2016. The impact of Brexit has tamed many of the xenophobic populist parties within Europe. Even the most extreme of the candidates in the upcoming French presidential election, Eric Zemmour, who speaks loudly of closing France’s borders, has not yet raised the spectre of a “Frexit” (although how he could achieve one without the other he cannot explain.) And with the British no longer there to slow it down, the Union is better placed to expand its “soft power.” The so-called “Green Deal” endorsed by the member states in December 2019, which aims to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050, will inevitably have a massive impact even on those “many international partners”—which must now include Britain—who, in the measured words of the Commission, “do not share the same ambition as the EU.” It is taking new initiatives to reform globalization and is playing an ever-increasing role in global governance by building “a European regulatory state” based upon a system of intergovernmental networks—as described by Anu Bradford, in her remarkable book, The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World. It is steadily, if all too slowly in the face of the growing power of China and Russia and of a barely controlled mass immigration, building a new, more humane, more varied, more flexible, more far-seeing political community.

“If Europe is to fulfill the promises implicit in the phrase ‘ever-greater union,’ it will need to develop a far more powerful sense of its own political identity.”

But if it is finally to become what the American political theorist and diplomat Anne-Marie Slaughter once called “the model for [the] new world order” it still needs to do more. It will need to develop a common policy of social welfare for its citizens and a single unified pension scheme. It will need to create a network of common health policies and common medical institutions, the absence of which has been such an obstacle in battling the current pandemic. It will need, as the French economist Thomas Piketty’s “Manifesto for the Democratization of Europe” insists, to create a common system of taxation and a fiscal control capable of fulfilling the promise of the Treaty of Rome of 1957, to bring about an “equalization in the progress of conditions of life and work.”

Most pressing of all, if Europe is to fulfill the promises implicit in the phrase “ever-greater union,” it will need to develop a far more powerful sense of its own political identity. European citizenship—of which all the peoples of Britain were stripped in January—has none of the emotive and cohesive power that citizenship of any nation-state is intended to offer. It must be made to count. And to do that, it should, as the European Court has so often insisted, in the last instance, trump the demands imposed by the member states. It should, in short, be a true transnational citizenship. It needs, as the ill-fated Constitution of 2004 claimed to offer, a union which “places the individual at the heart of its activities, by establishing the citizenship of the Union and by creating an area of freedom, security and justice.” This might then give some real substance to the slogan: “ever-closer union.”

“It can only be hoped that wiser generations might be able to ‘rebuild Europe,’ just as their ancestors had hoped to do after 1815, 1918, and 1945.”

It can only be hoped that, in this way, wiser, more experienced generations in some not too remote future might be able to “rebuild Europe,” just as their ancestors had hoped to do after 1815, 1918, and 1945. This might well then bring Europe far closer to the vision of “a community of others” or a “persistent plurality of peoples,” closer to being a true European people, varying perhaps as little in their cultural assumptions and political and social aspirations between the citizens of the member states as two centuries ago they did between the villages and parishes within a single nation. And if that happens then perhaps a new more far-sighted, more cosmopolitan Britain might be prepared to re-join the Union and become, at last, not merely with Europe, but also of it.

March 28, 2022

Celebrating women in STEM [timeline]

March is Women’s History Month, an annual occurrence dedicated to commemorating and highlighting the contributions that women have made throughout history. Many of these contributions have gone unsung or undervalued, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and medicine, where women have historically been underrepresented. Celebrating and recognizing the work of women in these field remains a priority for Oxford University Press, and this month and every month we are proud to support diverse voices across our publishing. We seek to create an inclusive space to highlight the work of women in STEM, and celebrate the contributions of trans and cis women, and women of all races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations.

The timeline—first published in 2018, now updated in 2022—provides a curated selection of achievements, discoveries, and innovations made by women in STEM, from the foundation of modern nursing to critical contributions in the effort to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. This is just a small picture of the countless women making an impact in STEM. For more on this subject we also offer two collections featuring the work of women in STEM: women in medicine and women in science.

Featured image by Dmytro Zinkevych via Shutterstock.

Reconstructing Claudius’ arch in Rome

In 41 CE, Roman emperor Claudius’ position in Rome was weak. He needed a military victory to assert his authority after predecessor Caligula’s assassination. No Roman leader had conquered Britain—the fabulous land set in the endless waters of “Ocean.” Julius Caesar was the first to cross Ocean to invade Britain in 55 and 54 BCE but had not been able to conquer the island, instead establishing an annual tribute to be paid to Rome. Claudius chose Britain as the venue for his ambitions of conquest.

Why did the island of Britain hold such an appeal to the Roman imagination? In Greek mythology, as inherited by the Roman elite, Ocean was endless and surrounded the inhabited world. Oceanus, the Greek god of the sea was one of the Titans and, as the Romans gained experience of the Atlantic Ocean, the domain of this ancestral god was pushed further to the north. Britain, as a vast island set within Ocean, had a special and unworldly identity that reflected the lack of knowledge of its peoples and lands. This gave the invasion of Britain a particular status for Roman generals and emperors looking to increase their power—hence the invasion of Britain. Therefore “Ocean” is capitalized here, to indicate its personification in the Greek and Roman tradition.

Claudius invaded Britain in 43 CE, exploiting the political instability following the recent death of the most dominant king of southern Britain, Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s “Cymbeline”), to achieve a famous victory. The initial phases of the conquest of southern Britain progressed speedily under the leadership of the general Aulus Plautius, who won several battles before many of the Britons surrendered. Plautius then summoned Claudius to travel from Rome to Camulodunum (Colchester)—the most important political centre (oppidum) in Britain prior to the Roman invasion—after these initial victories. Other information from a classical writer indicates that Claudius spent only 16 days in Britain, and probably spent most of his time travelling to Camulodunum from Kent and back again. At Camulodunum, Claudius received the submission of the “kings” of around 11 peoples. After the initial weeks of the invasion, much of southern Britain appears to have surrendered without serious fighting within a few months. The propaganda of Claudius played up the degree of fighting in what was a fairly swift campaign of conquest.

The triumphal archThe Roman senate awarded Claudius with the honorary title “Britannicus” and granted him a triumph in Rome. An annual festival was proclaimed, indicating the importance attached to the conquest of south-eastern Britain in 43 CE, and the senate decreed the construction of a triumphal arch in Rome to celebrate Claudius’s victory.

Arch of Constantine

Arch of Constantine(Livioandronico2013, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The arch was a material expression of the importance of the conquest of Britain to the senatorial elite in Rome. It was built into the Aqua Virgo aqueduct over the road leading north out of the city, the Via Lata, as part of a rebuilding programme. There are a number of triumphal arches in the city of Rome, including the famous examples of Titus and Constantine, which still exist. Only fragments of Claudius’ arch survive, but we have some antiquarian drawings of lost fragments and image on Roman coins.

The arch bore an inscription, which only survives in part, which provides very important information of the conquest that is not recorded in the available classical accounts of Tacitus and Dio. The surviving inscription tells us that Claudius had received the surrender of a number of kings of the Britons, conquered without loss, and was the first to bring the barbarian peoples across the Ocean under the authority of Rome. Unfortunately, the number of kings that submitted is uncertain due to the fragmentation of the inscription but is usually interpreted as 11.

It also helps provide the date of the arch. It appears to have taken several years for the arch to be constructed and there may have been an earlier arch constructed a few years after 43 CE, which might then have been modified in 51–2. By the time the arch was completed, Rome had come into conflict with the people named the Silures and Ordovices in western Britain. These battles resulted in a Roman victory in central Wales where the leader of the resistance, Caratacus, a son of Cunobelin, was captured and the Britons defeated. Caratacus and his family were paraded in Rome in 52 and this may be when the arch was finally completed (or reconstructed).

The significance of water in the design of the archThe inscription on the arch refers to the control that Claudius had established over people beyond Ocean and the arch itself had a fascinating relationship to water.

Oceanus, the Greek god of the Ocean, was the father of water in all its forms, including rivers, springs, wells and rainfall. This meant that the divinities who were felt to inhabit them were seen as children of Ocean. The Aqua Virgo, one of the 11 aqueducts supplying Rome, carried water into the city by a channel that ran over the top of Claudius’ arch. Numerous works in Rome and Italy during Claudius’ reign built upon the idea that he was master of water in all its forms. Other celebrations across the empire also commentated the emperor’s role, including the marble relief from Aphrodisias in Turkey showing Claudius receiving the submission of the land and sea in the form of two divinities.

The original design concept of this triumphal arch was fundamentally concerned with the control of flowing water by being constructed into the Aqua Virgo aqueduct. It complemented the arch of Drusus, the father of Claudius, which celebrated his triumph over Germania, constructed over the road south from Rome, the Via Appia. Travellers arriving and leaving the city by these routes would be affected by the powerful impact of these magnificent gateways.

It seems probable that the decoration of Claudius’ arch included scenes derived from the idea of conquering “Ocean,” including sea monsters and ships. No fragments depicting these beings are known to have survived, while the most impressive battle scene thought to be derived from arch was recorded in a sixteenth-century drawing showing Roman soldiers fighting Britons.

Though it no longer survives, there is enough information about the monument to undertake a colour reconstruction.

The reconstruction of Claudius’ triumphal archThe reconstruction

The reconstruction of Claudius’ triumphal archThe reconstructionThe reconstruction image is intended to convey the impact of Claudius’ British conquest at his powerbase in Rome. Although the exact original appearance of the arch is unknown, the reconstruction brings together the information from different types of material records and remains and draws upon the symbolic significance of water to Claudius’ conquest.

Building the reconstruction for Conquering the Ocean was greatly assisted by information in Anthony Barrett’s article in the archaeological journal, Britannia, which considered the composition of the general design of the arch and the evidence for its imagery and materials in some detail. Barrett reviews the surviving sculpted fragments that have been attributed to the arch, and others that have only been recorded in drawings made during the sixteenth century. Following the first recorded excavations on the site of the arch in 1562, the Neapolitan architect and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio recorded that the arch lay in a heap of marble fragments. He reconstructed an elevation of the arch, built into the aqueduct, noting the locations of some sculpted details. After this, all traces of the arch were removed but parts of the Aqua Virgo aqueduct survive.

The starting point for reconstructing the arch was planning the scale of the edifice. This was generally informed by surviving examples, such as the triumphal arch at Orange in France, and in more detail by the dimensions of the main inscription slab that was originally displayed over the gateway; this measured around six metres long and stood around three metres high.

Triumphal Arch of Orange

Triumphal Arch of Orange(Florent Pécassou, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

As all classical sculpture was at least partly coloured, either by painting or through the use of particular media, it was essential to reconstruct the arch in colour to convey the dramatic visual impact of the original design. The use of yellows and reds was informed by the fragments of the fluted marble columns referred to by the antiquarian Giacinto Gigli in the seventeenth century. These were carved from a deep yellow marble veined with red that may have been sourced from North Africa, fragments of which were found near the site of the arch in 1923. A blue-based green was also used for contrast, similar to the reconstruction of a column capital in green, red and yellow on display at the Harbour Museum at Xanten in Germany.

Bringing all this information together while filling the conceptual gaps—to build an entire architectural design with a dramatic appearance appropriate to the subject—was an engaging challenge. Every image reflects our stances (intentional or unintentional) and current agendae. If we know this, we can articulate these things in our image-making, to critique and question, as well as try out new “ways of seeing” things.

Although the arch does not survive, the conquest of southern Britain was the greatest achievement of Claudius’ successful reign. Because of the way that the Roman conquest of Britain played on the island’s status as an Oceanic realm, we felt it was important to reconstruct the arch in colour to communicate its significance. Much of the information for the conquest of Roman Britain is highly fragmentary and derives from a combination of classical texts and archaeological information. The reconstruction of the arch helps exemplify the challenges involved in piecing together the story of Roman conquest of Britain from Julius Caesar to Hadrian.

Feature image by Scailyna – own work, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

March 27, 2022

Why “the all-male stage” wasn’t

Why is “the all-male stage” inadequate as shorthand for the early modern stage? For one thing, it enforces a gender binary that has little to do with the subjects, desires, audiences, and practices of the time. Gender was elusive, plural, and performative, especially on the stage, where attractive androgynous boys played women, or switched back and forth between genders. The importance of female spectators, artisans, and backers gives the lie to total exclusion, and so does mounting evidence that women played in many spheres adjacent to the professional stage. Queens and aristocrats acted and danced in court masques, girls took roles in shows at great houses; mountebanks, tumblers, and rope walkers drew crowds on city streets; and women played in parish drama and danced in morrises. Similar performances by women show up on the professional stage, albeit in parts played by boys.

Not all this female talent came from England. Some came from abroad, especially Italy. In the mid-1570s versatile Italian troupes, some with star actresses, visited England and played for Elizabeth and for popular audiences. Their impact was immediate: writers began to turn out plays starring bold, exotic, and charismatic women. Each is a variant on the innamorata accesa (woman inflamed with passion), the trademark of the foreign diva. Suddenly boys were playing enticingly hot-blooded and Italianate heroines: the love-struck, cross-dressed virgins in Lyly’s Gallathea, the desperate Queen Dido in Marlowe’s The Tragedie of Dido, Queen of Carthage, and the strong-willed avenger, Bel-Imperia in Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy. From the start of his career, Shakespeare featured vividly theatrical Italian women, including Julia of Two Gentlemen of Verona, Beatrice of Much Ado About Nothing, Portia of The Merchant of Venice, and Juliet of Romeo and Juliet.

All bear a distinct resemblance to the prodigious innamorata shaped by divas such as Isabella Andreini, Vittoria Piissimi, Angelica Martinelli, and Diana Ponti. Like Shakespeare’s boy player, they were highly skilled professionals who began performing very young. All were trained in music and memorization, and some grew famous for singing. Both actresses and boys offered androgynous appeal and protean volatility, especially useful in comedies of cross-dressing. Both women and boys inspired writers to exploit their crowd-pleasing talent, training, and beauty, leading to more plays centered on women’s choices and desires. But there the resemblance ends.

As full company members, actresses had far more autonomy than boy apprentices. They also took far greater risks, traveling constantly in often hostile territories far from home, and some became leaders of their troupes. Successful actresses enjoyed social as well as geographic mobility. Most came from the courtesan class, where they gained their educations; but in the theater, they played refined young women. Unlike boys, some became international stars, with kings and queens as protectors and patrons. A few were literary prodigies, such as Isabella Andreini, who wrote and published poetry and a pastoral, and was admitted to an all-male academy. Whether playing the innamorata in comic, pastoral, or tragic modes, the diva always spoke in literary Tuscan, spinning out witticisms, conceits, or poetic laments. She gained this facility through constant study and memorization of choice passages from romances, novelle, and poetry.

To the English the diva was a glamorous prodigy, a novelty with tremendous stage appeal. Emulating the innamorata she created, they invented a “boy diva” capable of bravura displays—sung laments, swordfights, clever cross-dressing, riveting suicides—in plays of all kinds. To stress her alienness, the English stepped up the type’s metatheatricality. She stands out by alluding often to acting and theater, and leaps at the chance to perform. The audience is rarely far from her mind, and she connects to them by speaking in asides and soliloquys. She milks her big scenes by drawing out suspense, like Portia before the court in The Merchant of Venice, and delights in her own witty acting, like Rosalind in As You Like It. Proud of her greatness she seeks glory and fame, like Cleopatra. One of the most difficult star turns is the full-tilt mad scene, a specialty of Isabella Andreini, whose celebrity inspired Shakespeare, Webster, Middleton and others to include madwomen in their plays. All such roles relied on sprezzatura and improvisatory ability, qualities that were not easily imitated. By loading a boy’s role with alien literariness and emotional volatility, and cuing him artfully, playwrights created the illusion of Italianate improvisatory genius.

Because she is foreign, passionate, and theatrical, the diva-type is also scandalous and strange. English stage characterizations range in tone from fascinated ambivalence to savage caricature and bewhoring. Despite this animus, boys won applause and admiration as they portrayed Juliet, Desdemona, Vittoria Corombona, and other stellar roles, showing the power of the diva type in performance. Given the fervent attacks on theater and on actresses in particular, it’s remarkable that two vulnerable groups—women players and boy actors—did so much to increase the complexity and importance of female roles in this period. To return to my title, this phenomenon shows why “the all-male stage” is such a misnomer. Many of the best female parts written for boys, from Viola to the Duchess of Malfi, are marked indelibly by the creative labors of women.

Feature image: Calcografia in Iconografia italiana degli uomini e delle donne celebri: dall’epoca del risorgimento delle scienze e delle arti fino ai nostri giorni, Milano, Antonio Locatelli, 1837. Available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

A legal right to work from home? Here’s what the law says

Do you have a legal right to work from home? Can you insist on working a four-day week for the same wage? What if your employer refuses? In this blog post, we look at what UK law says about your right to work flexibly and the reality of the situation facing many employers and employees.

With the lifting of the remaining coronavirus restrictions across the UK, there is now no requirement for those who can work from home to continue to do so. As we have seen, however, the past two years have shown many people that they can do their jobs just as well from home and have a better work-life balance. A YouGov survey conducted at the end of January found that 71% of people preferred to work from home and 58% felt more productive when they did so. While some employers have been flexible, a number, such as Goldman Sachs, have insisted on staff returning to the office and the daily commute. Are they within their rights to do so?

The legal rightFirst of all, it should be noted that currently there is no legal right to work from home, or to be granted another type of flexible working—unless a person’s contract of employment says otherwise. The right is only one to make a request to work flexibly and have the employer consider that request “in a reasonable manner.” It is nothing more than that. The employer must, however, show that they have considered it reasonably—simply dismissing the request out of hand would not be legally acceptable.

The requestThe right to ask for a variation currently applies only to employees who have been employed for at least 26 weeks. They are allowed only to make one request in any 12-month period. The right does not just cover working from home, but also other changes to the contract, such as hours, times, and place of work.

The application has to be in writing, stating the change applied for and the date the employee wants this to take place. It must explain what effect, if any, the change will have on the employer’s business and how this effect may be dealt with.

The employer’s responseThe only obligation that an employer has is to consider the request in a reasonable manner. The employer can only refuse on one of eight grounds set out in the legislation. These are: the burden of additional costs; the detrimental effect on ability to meet customer demand; the inability to reorganise work among existing staff; the inability to recruit additional staff; the detrimental impact on quality; the detrimental impact on performance; the lack of work during the periods when the employee proposes to work; and planned structural changes to the organisation.

The employer has to make a decision and notify the employee within three months (or a longer period by agreement).

If the application is accepted, then the change will be permanent, and the employee would have to wait 12 months to make another one, unless the employer agrees otherwise.

If the employer refusesIf the application is refused, the employer may allow the employee to appeal internally, and this has to be heard within three months, unless an extension has been agreed between employer and employee.

If the request is not granted, the employee can bring a complaint to an employment tribunal within three months.

A tribunal cannot investigate the rights and wrongs of the refusal, it can only consider whether the employer has followed the procedure in a reasonable manner, or if the reason given for refusal was not one of the ones listed or was based on incorrect facts. If the tribunal finds that the complaint is well founded, it may make an order for the employer to reconsider the application and can award compensation to the employee of up to eight weeks’ capped pay. It cannot force the employer to grant the request.

An employee must not be treated detrimentally by the employer or dismissed just because they have made such an application. If they are, they can also complain about this to a tribunal within three months and obtain compensation for detriment or unfair dismissal (and unlike most unfair dismissal claims, they do not have to have been employed for two years to claim).

As an alternative to going to tribunal, the parties have the option of asking an arbitrator to deal with the case under the ACAS arbitration scheme. (Note that ACAS has also produced a guide to flexible working.)

The commercial realityEven before the pandemic, businesses were finding that flexible working arrangements enabled them to retain skilled staff and reduce their recruitment costs, to lessen absenteeism, and to react more readily to changing market conditions. Since then, market forces have heightened these considerations: another recent international survey found that up to 72% would leave if not satisfied with their company’s work location rules.

There is therefore strength in numbers. Many employers may find that if they do not accede to the requests, then they will lose valued staff, and it may end up not being a matter of law, but one of market forces. Indeed, looking ahead on how to retain staff, some employers are considering not just working from home but also a four-day week and reduced hours without reduction of salary, with a trial currently underway in the UK, and some countries, such as Belgium, are in the process of making this a legal right. Goldman Sachs may find that it becomes increasingly an outlier.

The law is looking increasingly outdated, although it may yet catch up. There is currently a government consultation considering making flexible working the default position, and whether to make it a “day one” right, so that someone does not need to have been an employee for 26 weeks before making such a request. As it stands, the law only gives someone a right to make a request, but commercial reality is on the side of employees, notwithstanding what the law says.

Please note that this an overview of the law and is not intended to be legal advice, and each case depends on its own specific facts.

Feature image by TheStandingDesk on Unsplash

March 26, 2022

Revenge of the hungry cockatoos? Spite and behavioural ecology

“How do I stop a cockatoo from attacking my property?” This is the title of a real, honest-to-goodness Australian government webpage and advice document on the New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment website. The webpage notes that flocks of cockatoos—sulphur-crested cockatoos especially—are known to “aggressively attack wood… decks, outdoor furniture, window sills, and houses” and that they particularly like the soft woods used in construction. The advice given ranges from making a scarecrow (or scarecockatoo, I suppose), to painting wood white, to spraying the birds with the hose (!), and it is recommended to persist in one’s chosen strategies until the birds leave, noting that this can take more than a week.

Most curiously, the page carefully elides the important question of why cockatoos attack—it says simply “there are many theories why they do this.” Ask an Australian, though, and the answer will be quickly forthcoming: the cockatoos are acting out of spite.

Most often, the supposed slight that caused the spite is the taking away of bird feeders. It may well be a case of confirmation bias, or simply of populations of hungry birds correlating within site of former bird feeders, but the story is usually told the same. “I normally put out bird seed in my garden, and all sorts of birds come and eat it, including the big cockatoos. One day, I forgot to put out the seed, and the cockatoos were clearly angry, and took it out on my house—they chewed right through my deck railing, and tore the weather stripping of my back windows!”

This superimposes a very human impulse onto the observed behaviour of the cockatoos: it looks and feels like revenge.

The idea that cockatoos are capable of human-like spite is a common one in Australia, driven both by the house-destructive behaviours and by videos and news stories of sulphur-crested cockatoos tearing off and destroying (seemingly with glee) the anti-bird spikes affixed to buildings to keep them away. I once saw a video of an activist who campaigns for better care for pet parrots destroying a small birdcage in front of the cockatoo who had been inappropriately kept in it, as the cockatoo squawked and head-bobbed and fanned his crest in what could only be described as celebration of the act of destruction. As human observers, watching the behaviours of these big, bold, intelligent birds, who are unafraid of showing us their emotions, it is very hard not to project human emotion onto the cockatoos.

” Spite is a very controversial matter when it comes to evolutionary biology and animal behaviour—and not everything that strikes us as spite at first look should really be given that name.”

But we have to be careful! Spite is a very controversial matter when it comes to evolutionary biology and animal behaviour—and not everything that strikes us as spite at first look should really be given that name. Take for example the anti-bird spikes. For a cockatoo that lives in a city, building ledges, street signs, and lamp posts are part of the bird’s (not-quite natural, but adopted) habitat. The bird has no concept of the purpose of the anti-bird spikes, because it has no concept of what is being prevented: property damage, cleaning costs, and public sanitation are not front-of-mind concerns for large parrots. The cockatoo does not see the spikes as an uncomfortable deterrent deliberately installed to keep it away, but merely as an environmental annoyance to be removed—like an ill-placed twig in a tree where it is trying to roost. So, like the twig, it destructively removes the spikes to make its environment more comfortable. The observing humans only see this as spiteful because we know what the bird does not—that the spikes were precisely designed and installed to make life less comfortable for the cockatoo.

Even supposing the cockatoo knew why the spikes were there, it still would not be spite because it has a material benefit to the cockatoo. It makes adaptive sense for the cockatoo to remove the spikes because it creates more space so that the cockatoo can comfortably and safely roost. A bit like having a car towed that has been improperly parked in your driveway, there may be a gruesome little bit of satisfaction, but it also has straightforward material benefit—you can park your own car in its proper place.

Animal behaviours that deal damage to other animals in exchange for benefit to the actor make evolutionary sense. Nature may be red in tooth and claw, but from the point of view of natural selection, dealing damage to obtain benefit is an easy calculation. From crippling parasites to territorial jostling to sexual competition, gaining a benefit at the expense of another animal is, unfortunately, how the natural world, and evolution, must often work.

What twists up the minds of evolutionary biologists though is the question of true spite: dealing damage to someone else at no benefit to yourself—just to hurt them. The human impulse to revenge has driven a lot of bad decisions in our history but it doesn’t make much evolutionary sense. Any action an animal takes, particularly violent and destructive actions, have a cost. That cost can be the chance of injury, the risk of retaliation, or just the physical energy expended; whatever it is, a well-adapted behaviour should not involve wasting energy and cost where there is no possible benefit to the actor. The cockatoos tearing up weather stripping are more like true spite. If the popular interpretation is true, and the cockatoos are retaliating after the house’s owner has stopped feeding them, the house destruction is costly spite on behalf of the birds. Cockatoos cannot eat wood or weather stripping, and in taking the time to rip up the house, they are wasting time that could be spent foraging elsewhere and risking potentially harmful retaliation (remember that hose?). The effort undertaken to destroy the house is pure spite—harming another with no chance of benefit to the cockatoos.

” Whilst we have to be careful about projecting our own emotions onto the behaviours of animals, that intelligence and social lifestyle is something we share with birds.”

Even here, though, we have to be careful. Part of a cockatoo’s natural behaviour includes chomping through wood in search of grubs and other food sources. It is conceivable that, in finding the usual bird-seed tray empty, the birds have sought to conserve energy by seeking other food sources in the immediate vicinity before moving on—including by searching the deck’s balustrade for tasty wood-boring grubs. As with every animal behaviour, we have to carefully interrogate the total environmental context of any behaviour before we draw conclusions about what might be going through the animal’s mind.

Spite, or revenge, is a very human idea. Our high level of intelligence and our highly social nature have resulted in our own species being all too capable of visiting non-adaptive, costly, damaging spite on our fellow humans—often harming ourselves in the pursuit of vengeance upon others. It is one of the uglier consequences of our remarkable brains. Whilst we have to be careful about projecting our own emotions onto the behaviours of animals, that intelligence and social lifestyle is something we share with birds, and especially with big, smart birds like cockatoos. Spite remains a controversial question in evolutionary biology—but it’s not surprising that one place we see truly spiteful behaviours that might just be real is in a bird that has so much in common with ourselves.

March 25, 2022

What are viruses for?

What are viruses for? What use are they? These are questions that my frustrated grandson asked during the first lockdown in 2020, when he was deprived of friends, school, and sports, all because of a virus.

Of course, these questions can be discussed at several levels from the philosophical to the practical to the scientific, but the bottom line is that although viruses are well known for causing potentially lethal infectious diseases in animals and plants, they are not all bad. Here I discuss the nitty gritty of the world of viruses—the virosphere—including what viruses are, how they survive, how they impact on life on earth and how we are beginning to harness them for our own good.

What are viruses?First, I must clarify what viruses are: plants? Animals? Fungi? Bacteria? Archaea? The answer is none of the above. Because viruses are not built of cells like all other life forms, they don’t fit into any domains of life. So the question becomes: are viruses actually alive or are they inanimate entities? And on this issue scientists disagree. Viruses are particles that possess some attributes of life, such as an inherited genetic code, but they lack others, like the ability to metabolise. So, viruses are obligate parasites; the particles that carry their genetic code as either DNA or RNA (meaning ribonucleic acid, similar to DNA but a long, single-stranded chain of cells that processes protein and carries genetic information) are inert until they infect a living cell. Then they highjack the cell’s organelles to download viral genes and translate them into virus proteins from which new viruses can be assembled. Then finally thousands of offspring are released from the cell to infect other cells in a never-ending trail of destruction.

How do viruses cause disease?Viruses cause disease by damaging or killing the cells they infect, and so the profile of a disease induced by a virus is determined by the type of cells a particular virus infects, be it the pneumonia induced by the SARS coronaviruses, the skin rash of measles, or the terminal immunodeficiency of HIV. Only a tiny minority of viruses, estimated at 220, cause disease in humans, yet the dimensions of the virosphere are astonishingly vast. Viruses are the smallest, most abundant, most diverse, and most widespread infectious agents on the planet and kill more living things than any other creature. There are around 200,000 different virus species, with more individual viruses on Earth than there are stars in the universe, estimated at something like 200 billion trillion (^2×1023).

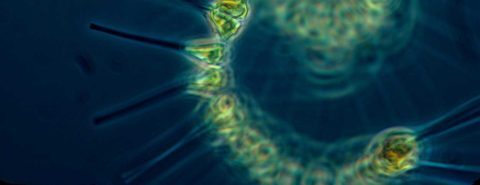

Why are viruses important?Viruses infect all living things, most of which are microbes. For example, every litre of sea water contains around 10 billion bacteria and approximately 100 billion viruses, mostly bacteriophages (phage for short). As their name suggests, these infect and kill co-resident bacteria, and in doing so they perform an essential role in controlling bacterial populations, thereby stabilising marine ecosystems. Phytoplankton, the oceans’ floating population of tiny marine organisms including bacteria and archaea, are vital for marine life. They form the base of a vast food-web that begins with zooplankton, which sustain young marine animals, which feed fish, which in turn fall prey to large marine carnivores. Phytoplankton generate energy by photosynthesis, and in doing so are essential for atmospheric stability. By converting atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) into oxygen (O2) and water, this vast population generates around half of the world’s oxygen while also removing CO2 from the atmosphere. Marine phage control and stabilise the dynamics of this reaction by infecting and killing phytoplankton microbes that would otherwise grow uncontrollably.

Also, phage, with a generation time measured in hours, can react rapidly to any population imbalance. For instance, when nutrient levels in estuarine waters suddenly increase, often due to fertiliser runoff from agricultural land, this can cause the rapid proliferation of certain phytoplankton microbes which then cover the surface of the ocean in an algal bloom. By blocking out sunlight and producing algal toxins, this has the potential to destabilise phytoplankton ecosystems, seriously depleting O2 levels. But the rapid response of co-resident phage, with thousands of offspring released from each infectious cycle, can restore order in a matter of days.

Marine phage are also adept at initiating gene swapping. By mistakenly picking up a gene from one host and carrying it to another, the transferred gene can occasionally cause a beneficial behavioural change in its new host. Such changes may involve an increased tolerance to alterations in water temperature or chemical composition, which will allow the host to rapidly outcompete its neighbours and become the dominant population.

This neat trick for transferring foreign genes is now being utilised by scientists, both in the laboratory and more recently in the clinic. Certain designer vaccines consist of a harmless carrier virus genetically engineered to carry pieces of DNA or RNA that, when administered to a new host, will express the chosen vaccine sequence and induce the desired immune response. Several new COVID-19 vaccines presently in clinical trials have been engineered in this way, as has the Ebola vaccine that played a key role in ending a recent large outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

I hope that I have said enough to convince you (and my frustrated grandson) that viruses are essential for life on earth, but nevertheless, the present COVID-19 pandemic certainly underlines how fast-spreading, unpredictable, and lethal viruses can be. COVID-19 caught the world unprepared, with collective failures in pandemic preparedness, prevention, and response, thereby precipitating a global health and economic disaster. Clearly our present focus must be on preventing another such event occurring in the future. But how to approach this massive task? Can we avoid virus spill-over from animals by implementing human behavioural changes? Could we spot potential pandemic microbes in animals and take evasive action? Or should we settle for setting up early warning systems that would prevent a potential pandemic microbe from spreading among us?

If the next pandemic microbe is a bacterium rather than a virus then it may be possible to copy the natural marine cycles that control phytoplankton populations by using phage treatment to kill the infecting bacteria before they can cause terminal illness. This type of treatment has been used experimentally in people infected with multidrug resistant bacteria and may still come to our aid if such organisms become more widespread.

Featured image by NOAA on Unsplash

March 24, 2022

Memory, truth, and justice as Argentina honours the victims of state terrorism

24 March is a public holiday in Argentina, officially designated as The Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice. The date commemorates the 1976 coup d’état that unleashed seven years of military dictatorship, a period that most Argentinians refer to today as the time of state terrorism.

The legacy of the coup on Wednesday 24 March 1976, continues to echo in Argentina, especially for the tens of thousands of families who lost loved ones during the military’s euphemistically-styled “national re-organization process.”

It has been nearly 45 years since the end of military rule in 1983 but, still, no one knows precisely how many people were killed or disappeared during el Proceso. Argentinian human rights organizations estimate the number to be 30,000, a figure that has occasionally sparked denialist reactions from apologists for the military regime.

The fact is, the reason no one knows the number is the regime’s deliberate strategy of “disappearing” its opponents (the word became an active verb in Argentina during this time). Disappearance of people with dangerous ideas, or even sometimes those connected to them, was one of the most effective tactics in the toolbox of state terrorism. It not only got rid of “subversives” and their sympathizers, it terrorized and neutralized everyone in their environment, from those who feared they could be next to those who feared that something they said or did could endanger someone close to them who disappeared but might still be alive.

Since the restoration of democracy in 1983, there have been waves of reckoning in Argentina. The liberal, centrist government that replaced the generals prosecuted and convicted nine top military leaders in a Nuremberg-style trial in 1985. But the government gave in to pressure not to pursue lower-level perpetrators who carried out the criminal designs of their leaders.

In 2005, however, Argentina’s supreme court opened the way for new trials for human rights abuses under the dictatorship, designating them as “crimes against humanity committed in the context of the international crime of genocide.”

Since that time, more than 1,000 perpetrators have been convicted and are serving terms up to life in prison for acts including torture, murder, kidnapping, and “a thousand types of humiliation,” in the words of one of the federal prosecutors who has worked on the cases. Many of the convicted are serving their sentences at home, under loosely-supervised conditions of house arrest.

Last December, president Alberto Fernández announced the creation of a new “memory space” at the former Campo de Mayo military base in Buenos Aires, which served as one of the country’s most notorious clandestine detention centres—as well as the take-off point of regular “death flights” of illegally detained prisoners during the dictatorship.

There are now several memorial sites, at selected symbolically significant locations around the country. New places where atrocities occurred are still being discovered. A government commission identified 341 clandestine detention centres in 1984; the latest count stands at more than 520.

I visited one of these locations in April 2018, on an “alternative walking tour” of Buenos Aires that included a stop outside the Olimpo clandestine detention centre in the residential district of Floresta. A one-time tramway and bus terminal in a quiet neighbourhood, protected from outside view by high brick walls and accessible through a steel front gate, the location was taken over by the federal police after the coup. Olimpo reminded me of Buchenwald, not because of any physical resemblance but because of the utter banality of its setting. Like Buchenwald, a mere bus ride away from the centre of Weimar, Olimpo is right there in the middle of Buenos Aires and it is inconceivable that neighbours of the camp had no idea that something terrible was going on there.

Unidentified remains of disappeared victims are still being discovered in unmarked graves in Argentina. Using DNA samples collected from family members, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), an NGO established in 1984, has been able to identify 800 people, out of some 1,400 sets of remains that it has recovered.

Children who were appropriated from disappeared parents continue to surface as well. At latest count, around 130 of the 500 appropriated children identified by the human rights organization las Abuelas (grandmothers) de Plaza de Mayo have had their identities restored. In 2021, the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs, along with the Abuelas and Argentina’s National Commission for the Right to Identity (or CONADI) launched an international campaign entitled Argentina te busca (literally “Argentina is looking for you” but officially translated as “Help us find you”), inviting anyone in the world who suspects that they might have been an appropriated child to contact their local embassy or consulate. Alongside this government initiative, the EAAF has begun collecting DNA samples from foreign donors to add to their forensic data base.

For Argentine society at large, the trials of perpetrators and other government efforts constitute a semblance of accountability—but they are little solace for the survivors. Perpetrators almost never reveal anything about the fate of their victims, even when they acknowledge their roles, as they sometimes do, justifying their crimes as having been “necessary” for the preservation of “Western, Christian civilization.”

Outside Argentina, remarkably, little attention is being paid to this ongoing drama. Yet, Argentina is making international jurisprudence regarding accountability for state terrorism. At least there’s that.

Feature photo courtesy of the author, Marc Raboy.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers