Oxford University Press's Blog, page 80

April 13, 2022

On buying and selling

Strange as it may seem, the origin of the verb buy remains a matter of uninspiring debate, at least partly because we don’t know what this verb meant before it acquired the modern sense. To us the process of buying or purchasing contains no mystery: it refers to obtaining goods in exchange for money. However, in the remote past, people did not buy goods: they produced them for their own consumption or exchanged them for other goods. Characteristically, money and mint are words of Romance origin. Purchase is also a borrowing from Old French, and it, too, meant “to obtain, to acquire,” rather than “to buy.” In our oldest Germanic texts, gifts were often exchanged but hardly ever sold and bought. Though the corpus of Old English texts is not so small, the verb bycgan, the ancestor of buy, occurred in the extant literature only in the twelfth century (that is, with regard to Old English, very late). At that time, it meant “to redeem, to ransom.” A century later, this verb turned up with the sense “to expiate.” The sense known today is later.

In the Germanic-speaking world, only Icelandic preserved rich old native prose, and, while reading the sagas, one notices with surprise how seldom any goods are bought or sold. Money existed and was greatly valued, but no one ever “went shopping.” Silver and gold, and artifacts made of precious metals, were constantly used as gifts and as compensation for murder and other crimes, but banks, money lenders, usurers, and the many appurtenances of later economy did not exist. Yet one could buy a ship and a slave. One of the central characters in The Saga of Njal tried, at the time of famine, to buy hay and cheese from a neighbor, but this is not a typical case. Anyway, the neighbor turned down the request, and we don’t know the details of a possible bargain. In another story, the king wanted to buy a polar bear. Thus, trade was not the backbone of their economy. Curiously, a cognate of bycgan existed in Old Icelandic, but this verb, spelled byggan, meant “to buy a wife; marry” (exactly as in Hebrew: makar!) and “to lend or lease.”

Obtaining a wife in the Middle Ages.

Obtaining a wife in the Middle Ages.(Marriage of Bohemond I, Prince of Antioch, and Constance, daughter of King Philip I of France, circa 1106, Chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Trésorier. British Library, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.)

In the fourth-century Gothic Bible, translated from Greek, bugjan (also used with various prefixes) occurs many times. It renders the Greek verb meaning “buy.” And with a prefix the same verb means “to sell.” The word that Bishop Wulfila, the translator of the Gothic Bible, saw in Greek is agorádzein. Now, Greek agorá meant “(a public place of) assembly; marketplace.” It occurs in Luke XIV: 18. Wulfila of course knew the meaning of the noun agorá, but it is not clear how he understood the verb. Characteristically, a verbal noun with the same root as in bugjan and a prefix, namely faur-bauhts (the variation in the vowels is regular and consonants is regular) meant “redemption” and corresponded to Greek apolútrōsis,” and we have seen that Old English bycgan also meant “to redeem.”

The oldest sense of the verb that has come down to us as Old English bycgan seems to have meant “make a bargain; redeem; obtain a wife” and had something to do with exchange. Several attempts connect buy with the Germanic verb meaning “to bend,” such as, for example, German biegen. English bow “to bend” is an exact match for biugan. The development from “bend” to “submit, bring something under one’s control” is thinkable but not too persuasive. Goods change hands, that is, “move,” as evidenced, for instance by Greek pōléō “to sell” versus pélō “to move.” The posited tie to “bending” is not unreasonable. Predictably, even those researchers who accept it are not too enthusiastic, while the more cautious dictionaries prefer to say about buy “origin undisclosed.”

Mercurius, the great protector of merchants and thieves.

Mercurius, the great protector of merchants and thieves.(Archaeological museum Gunzenhausen via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 1.0)

The odd spelling of buy recurs in busy and build. Old English had a vowel like German ü. (That is why the oldest form was spelled bycgan.) This vowel changed differently in different Middle English dialects: it either became short i or developed into short e or short u (as heard in today’s pet and put). The modern form buy has the pronunciation of the south and the spelling of the west (one of the pleasures of our unreformed spelling).

Some other hypotheses concerning the origin of buy are either not better (perhaps from the root meaning “to enjoy,” that is, “to acquire and enjoy the use of, to own, to possess,” with a single reference to Sanskrit) or fanciful (b- is a prefix, etc.). Only one thing is probable: in the past, buy meant “to strike a bargain; to free by paying ransom” or something like it. “Bending” does not come close enough to such senses to arouse universal enthusiasm.

The verb sell exists in the same clear obscure. Its Gothic form –saljan occurs in Wulfila’s text twice, both times with a prefix (hence my hyphen), and the prefixes differ. However, it means “to offer sacrifice.” The verb has regular cognates everywhere in Germanic, but German lost it (the German for “sell” is kaufen, related to English cheap; this word is of Latin origin). The trouble is that, as just noted, Gothic saljan meant “to sacrifice,” rather than “to get for a payment.” Obviously, for sell to mean what it does to us, people needed a system of exchanging goods for money. Words with the same root and more or less corresponding meanings exist outside Germanic: in Greek and Celtic. But s and l are not subject to the Germanic Consonant Shift, which turned non-Germanic p, t, and k into f, th, and h, so that all kinds of chance coincidences (unrelated s-l formations) are possible in this group of words. In Gothic, another saljan “to be a guest of” has also been recorded. The few attempts to reduce them to the same etymon, though ingenious, do not carry conviction.

If saljan is indeed related to Greek ‘eleîn “to take” (the initial aspiration in the Greek verb goes back to s), then Gothic saljan “to sacrifice,” which, naturally, presupposed offering, giving something, must be twisted into the sense “to be given, to receive.” This tour de force is not unthinkable, because verbs do sometimes combine opposite meanings, but in reconstructing the origin of an obscure word, the fewer assumptions we make, the better.

Books on word origins are always in demand.

Books on word origins are always in demand.(Jeremy Brooks via Flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0)

It is curious to observe how all our simplest commercial words originated. For example, trade is a loan from a fourteenth-century Low German dialect and meant “track, course, way.” It is related to the verb tread. Modern German Handel means simply “doings” (corresponding to the verb handeln “to operate, perform”). Merchant and merchandize are Romance loans (via Old French). Don’t forget Mercurius, the patron of merchants and, alas, thieves. Unfortunately, the etymology of the two English most basic verbs of commerce (buy and sell) remains partly undiscovered. I am sorry to say so but very much hope that our readers will buy this unsastisfactory conclusion without chagrin and complaints.

Featured image by Khuc Le Thanh Danh on Unsplash. Public domain.

April 10, 2022

Contraction distraction

A few years ago, a student dropped a linguistics course I was teaching because the textbook used contractions. The student had done some editorial work and felt that contractions did not belong in a college textbook, much less one he was paying 50 dollars for. It was probably all for the best. If he didn’t like contractions, he probably would’ve hated the course.

When the matter came up, I mentioned that the formality of earlier times had passed and that writing in the twentieth century and twenty-first had moved in the direction of colloquial speech, with its contractions and reductions. Contractions, I suggested, often made writing more readable and accessible.

And I recommended Garner’s Modern English Usage to him for a second opinion. I recalled Garner writing that contractions were acceptable in “most types of writing,” though he noted many people “feel uncomfortable” with them. My secret hope was that someone in the class would get interested enough in contractions to write a paper on the subject.

That didn’t happen, but the episode got me to think more about contractions—when they are smooth and when they are clumsy or even impossible. Garner, for example, notes the orthographic illusion of contracting who are to who’re, and he reminds us of the sketchiness of multiple contractions such as I’d’ve. And of course, there’s the potential for misspelling when could’ve, would’ve and should’ve become internalized as could of, would of, and should of.

The lesson is that it pays to keep track of different types of contractions and some of their surprising intricacies.

Consider the adverb not, which can be contracted as n’t on most auxiliary verbs: isn’t, aren’t, haven’t, didn’t, and so on. The big exception is the contraction of am and not as ain’t, which is still frowned upon in speech and proscribed in conventional writing. But contraction is also impossible with may: there is no mayn’t (or main’t).

Not can be contracted ontoauxiliary verbs, but auxiliaries themselves also contract to a preceding subject noun (Sally’s going) or pronoun (I’d, you’ll, they’re, etcetera). However, you can’t do both types of contraction at once: there is no Sally’sn’t or they’ren’t.

Contraction is not anything-goes simplification; it’s got its patterns. The contraction ‘ll refers to will not shall (though there are some historical counter-examples). And the contracted ‘d represents had or would (I’d just gotten home… or I’d help if I could …).But ’d isnever understood as could or should, a quirk noticed long ago by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen.

Still another curiosity has to do with the strange behavior of the main verb be. The auxiliaries have and be contract quite easily. But main verb have resists contraction in American English (hence the oddness of I’ve a new car in American English). The main verb be, however, contracts freely (as in Everyone’s very happy). Be is a main verb that behaves like an auxiliary.

Contraction is also impossible before the omission created by ellipsis. So, sentences such as Sarah is a better speaker than I’m or Jo has read as many novels as she’s are decidedly unEnglish.

Linguists love such intricacies of contraction for what they can tell us about how language works. For working writers, there is this advice from Rudolf Flesch’s 1949 The Art of Readable Writing:

Contractions have to be used with care. Sometimes they fit, sometimes they don’t. It depends on whether you would use the contraction in speaking that particular sentence (e.g. in this sentence I would say you would and not you’d).

That’s good advice. When in doubt, read it aloud and see how it sounds.

Featured image: “Rock formation in in Joshua Tree National Park, Southern California.” by Brocken Inagory. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

April 7, 2022

Three times systemic racism hindered Buck and Bubbles’s show business career

Since George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police in 2020, social justice advocates have targeted systemic racism in housing, education, and law enforcement. Less attention has been paid to entertainment. As the recent controversy over racial bias in the Academy Awards suggests, however, this problem has always existed in show business. The career of legendary vaudeville team Buck and Bubbles shows how it worked.

Buck and Bubbles (aka tap dancer John Bubbles and pianist Buck Washington) were Black contemporaries of such well-known white duos as Laurel and Hardy and Abbott and Costello. Buck and Bubbles might have become well-known, too, if nameless forces hadn’t blocked their progress at pivotal moments in their career. Here are three examples:

RKO VaudevilleIn September 1928, Buck and Bubbles had reason to hope for an upsurge in their professional standing. For eight years they had been denied headliner status despite consistently (according to the critics) outpacing their white competitors. Now, they had just dominated a high-profile gig at the New York Palace, upstaging the headliners and securing a rare and much-coveted second-week booking (the first time such an honor had been given a Black act, according to the Pittsburgh Courier). Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO) immediately offered them a contract at $750 a week the first year, $850 the second, and $900 the third. The clear expectation was that RKO would send them out as headliners themselves.

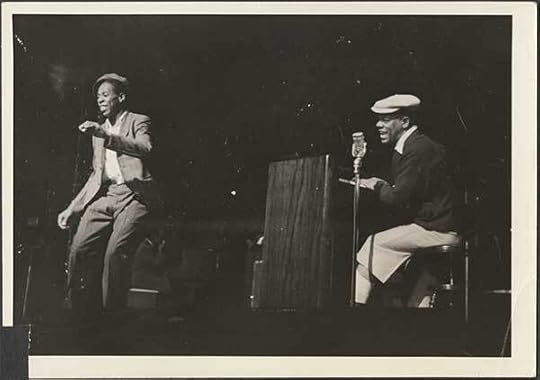

Buck and Bubbles in performance. “They were an act no one wanted to follow,” recalled a contemporary.

Buck and Bubbles in performance. “They were an act no one wanted to follow,” recalled a contemporary.(Used with permission.)

But this did not happen. Instead RKO booked Buck and Bubbles for a California tour headed by comedienne Frances White. What followed was an all-too-familiar pattern as Buck and Bubbles again overshadowed the headliner, making themselves “the hit of the bill” and “[casting] a spell over the audience that some critics have called ‘hypnotic.’” When White left the show after a few months, RKO replaced her with another white headliner, bandleader Gus Arnheim. Again, Buck and Bubbles stole the show, becoming the only act to be held over for a second week at the Los Angeles Orpheum. RKO’s shabby treatment of them continued for another year and a half, until outside circumstances intervened to dissolve their contract.

The Ziegfeld FolliesIn early 1931, one of their childhood dreams came true when Buck and Bubbles were invited to join the celebrated Ziegfeld Follies. They were only the second Black act to do so, after Bert Williams. In a huge company of over a hundred people, Buck and Bubbles were part of a large cast supporting the four headliners. On opening night of the tryout in Pittsburgh, Buck and Bubbles received an ovation that lasted a full five minutes. And when the company opened in New York, Buck and Bubbles were spotted “next-to-closing,” the penultimate spot on a program normally reserved for the most important act on the bill. Why? According to Bubbles, it was because after two weeks in Pittsburgh none of the other acts wanted to follow them. In this bright spotlight they again thrived, “[hitting] that opening house like a ton of granite.”

Yet for unknown but almost certainly racially-motivated reasons, the white entertainment papers of New York concealed this triumph. In Pittsburgh Variety barely mentioned the team, and when the show opened in Manhattan the critic merely expressed annoyance that Buck and Bubbles had been spotted next-to-closing. We only know of the duo’s audience popularity from reports in Black newspapers and the Pittsburgh press. The Follies of 1931 appeared in New York for five months. The experience should have given Buck and Bubbles a substantial career boost, but the unconscionable silence of white New York critics killed their momentum.

Varsity ShowIn 1937, Buck and Bubbles got their first chance to appear in a white feature film. Cast as janitors in Varsity Show, a college musical, they were given a bit more than three minutes of camera time to perform two set pieces. Their presence was so slight that Variety didn’t even mention them in its review of the film. By contrast, the Ritz Brothers, white competitors of Buck and Bubbles in vaudeville who made their feature film debut the previous year, were given five times as much camera time plus a written plug from the studio at the end of the movie. The Ritz Brothers went on to make fourteen more features in the next seven years; Buck and Bubbles’ contract, meanwhile, was not renewed.

Among other reasons for this failure, the studio was undoubtedly alarmed by Bubbles’s potent sexuality. Reports of his work in vaudeville and on Broadway (especially in Porgy and Bess) attested to his masculine allure. These rumors were confirmed on the set of Varsity Show, where, according to the Chicago Tribune, the young women of the cast flocked around Buck and Bubbles during breaks. The director took note. For the team’s first set piece Bubbles was asked to perform his dance feature down in the boiler room of a frat house, where only a few male students sat watching. For the second set piece, Buck and Bubbles performed on a fantasy set with no spectators at all. It was crucial to seal them off from the student body, to never present Bubbles alongside admiring white coeds. Apparently, despite his talent—and because of his race—he was too radioactive for a prominent role in Hollywood.

Buck and Bubbles in Varsity Show.

Buck and Bubbles in Varsity Show.(Used with permission.)

What’s the lesson of these examples? It’s not that the entertainment world didn’t value Buck and Bubbles. On the contrary, gatekeepers very much saw the team as a golden goose. Threading a devilish needle, they wanted to showcase Buck and Bubbles but not too much, lest they overshadow their white competitors. So, they gave them big contracts but withheld headliner status. Or they recruited them for the Ziegfeld Follies but refused to report their success. One critic voiced the patronizing attitude of the white establishment: “The colored young fellows are great entertainers in their own little way, and theirs is an act that is a decided asset to the big time.” In other words, they had a role to play, but only if they did not forget their subordinate place. No single showbiz chieftan can be blamed for hindering their careers. Buck and Bubbles fell victim to a racist system in which the need to subjugate them for their skin color was taken for granted by people across the industry.

Featured image: Domino Johnson (John W. Bubbles) in MGM’s Cabin in the Sky, 1943. Used with permission.

April 6, 2022

Etymology gleanings for March 2022

Native speakers and word history

Native speakers and word historyThe question came up in connection with the possible ties between English good (which has related forms elsewhere in Germanic) and Greek agathós. In all probability, those words are not cognate. Two points have been made: 1) foreign scholars cannot draw fully convincing conclusions about words of old languages because they are guided by context, rather than by native intuition, and 2) the modern meaning of agathós fits English good very well. (On the second point see also below: good and God.)

Obviously, the meaning of an old word can be deduced only from the context. Therefore, words that occur in Old English or even in Latin once or very few times are hard or impossible to gloss with precision. Agathós is an epithet often applied to the noun meaning “hero, warrior.” Obviously, neither “nice” nor “pleasant” will fit such a context. To a certain extent, native speakers are even at a disadvantage when reading old texts in their language because they do not realize that in the past the words familiar to them might not mean what they think. (For comparison: while teaching Middle High German texts in the English-speaking world—Minnesang, Parzival, etc.—it is more profitable to translate them into English than into German, to avoid false associations.)

I’ll cite a few adjectives belonging more or less to the same semantic sphere as good and indicate their recorded development in English through the centuries.

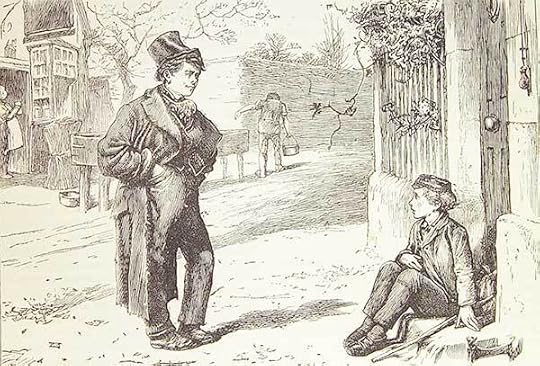

Pretty: crafty, wily; clever, ingenious; attractive ; considerable (we can still say not only pretty late but if we choose to be facetious, even pretty ugly).Clever: adroit, dexterous (in dialects), nimble, active, smart . The way from “adroit” to “smart” is perhaps shorter than from “crafty” to “attractive,” but it cannot be taken for granted.Cunning: learned (“knowing”), skillful, artful (the latter as in Dickens’s Artful Dodger).Nice (perhaps the most dramatic case): stupid; wanton; difficult to manage or decide; minute and subtle; dainty; agreeable, delightful .Shakespeare’s favorite epithet is sweet “dear,” as preserved in sweetheart, and it means many different things. A foreigner would not have produced the Iliad or Hamlet, but the same person can sometimes explain every word in them better than forty thousand native speakers. So much for Greek agathós.

Artful Dodger.

Artful Dodger.(“Hullo, My covey! What’s the row?”, illustration by F. Barnard in The Adventures of Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0)Soul

I think we are chasing a rainbow. If the meaning of a word is unknown, we cannot discover its origin. What substance was called soul? Our remote ancestors did not associate death with a complete disappearance of the deceased. Either their shadows languished in Hades, or they moved to another realm and continued to live there forever. Yet some substance of life was probably believed to have left the dead person. Perhaps this substance is what we today call soul. Breath fits such an idea, but this is not what is called “soul” in the Bible, and only the Bible interests us at the moment, because we want to know how Bishop Wulfila found an equivalent for the Greek word in the New Testament.

The Hebrew word ne-phesh (I used the hyphen to indicate the correct pronunciation), as it is used in the Old Testament means approximately “living substance,” and it is characteristic that translators into English had some trouble with it. My source is the King James Bible. In Genesis I:20, the word occurs for the first time: “Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life…” And in II:7, we read: “And the Lord god formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.” The word I italicized above (life, ne-phesh) is also “soul” in the original. Wulfila’s saiwala is opaque. It does not resemble any Germanic noun for “life” or “breath.” And the most ingenious attempts to “decipher” it have yielded no durable result. Most of the proposed etymologies are clever, but none of them carries conviction.

Monkey A man with a monkey. What is their origin?

A man with a monkey. What is their origin?(“The Savoyard and the Monkey” by Alexandre Gabriel Decamps. Public domain.)

On 23 January 2013, I posted an essay on the origin of the word monkey (Wrenching an Etymology out of a Monkey) and said, among other things, that all kinds of improbable ideas on the origin of this word exist. In a later set of gleanings, I also wrote a few sentences about monkey “mortgage.” Incidentally, the phrase to have a monkey on the house is very late British slang (no known occurrences before the eighteen-sixties), but this is an aside. In my 2013 story, I noted that many more nonsensical attempts to account for the origin of the animal name monkey existed, and our correspondent asked me to list them. The list is not inspiring. Old etymologists (and in England there is nothing to read on the subject before 1617—as far as English etymology is concerned) always tried to trace the words of their languages to Hebrew, Greek, or Latin. Hence references to Greek mîmeo “to imitate” and Latin homunculus. But other etymons have also turned up, for instance, Spanish (??) mouna, with reference to monk, and French manqué “a creature falling short of a human being.” Those who proposed such sources seldom realized that a convincing etymology presupposes more than discovering a putative source. If a word is a borrowing, it is necessary to find out why it has been taken over by the speakers of another language, who brought it home, and why this loan suddenly became popular and even universally known.

Odds and endsDanish bavenhøj seems to have always had this form and this sense. Balefire turned up in Beowulf (see the word in the OED), then disappeared from use, and reemerged later. Perhaps it has been coined twice, which is not improbable, because balefire is a typical tautological compound (both components mean approximately the same, as in pathway, courtyard, and German lauwarm “tepid, lukewarm,” actually, “warm-warm.” See the post on tautological compounds for 21 January 2006. Such words are much more common than it appears at first sight, especially among place names.

The Greek word echo is indeed an onomatopoeia. All sources agree on this point.

Good and god may be connected in some languages, but no analogy will bridge the difference between the vowels in the two English words. They cannot be derived from the same root. I am the first to admit that sound correspondences often fail us, and in such cases all kinds of explanations are called forth. For instance, the English preposition to corresponds to German zu, and the match is perfect. But their Gothic cognate is du, and this d- is inexplicable: though the words must be related, the consonants violate the rule (Gothic should have had t-, as in English). In such cases, historical linguists bend over backwards to account for the irregular form. But why break a lance for a lost cause? Only because we want the Supreme being to be good? God will survive without false etymologizing. By the way, old etymologists believed that Devil and evil are related. But they are not.

Featured image: “The fight for the body of Patroclus” via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

April 4, 2022

What is the French presidential election about? [Long read]

In this series of blog posts, the historians Michael C. Behrent and Emile Chabal have teamed up with award-winning French journalist, Marion van Renterghem to offer an in-depth look at the stakes, issues, themes, and big ideas that underpin the 2022 French electoral cycle.

This first blog post focuses on the unique character of this presidential election campaign, which exposes profound changes in the French political landscape in the context of a major European war. The second blog post in late April will take stock of the results of the French presidential election. The final blog post, looking back at the entire electoral cycle, will appear in late summer, after the French legislative elections. The entire series will be published at the end of the year in the journal French History.

The upcoming French presidential election presents something of a paradox. On the one hand, the outcome seems—at this stage—a foregone conclusion. Every single poll has the outgoing president, Emmanuel Macron, on course for re-election, often by a double-digit margin in both rounds. Not since Charles de Gaulle contested the first direct presidential election of the Fifth Republic in 1965 has one candidate’s success seemed so inevitable. Such is the weight of expectation that the entire political class and a good chunk of the French electorate have accepted this fait accompli with little more than a shrug.

Nevertheless, while such an overwhelming electoral narrative could easily be interpreted as a mere continuation of the status quo, nothing could be further from the truth. This presidential election, more than any other in recent memory, exposes much deeper transformations that have been taking place in French politics—and does so in a remarkably volatile geopolitical context. What this election lacks in suspense, it more than makes up for in its complexity. Indeed, it is likely that the main story—Macron’s re-election—will turn out to be one of the least interesting things about it.

Macron, the inevitable president?Long before the crisis in Ukraine took a decisive turn for the worse, Macron had set himself on course for re-election. The pandemic neutered the most sustained grassroots opposition to his rule, which came from the multifaceted gilets jaunes movement in 2018-9. This months-long protest movement focused on some of the most unpopular aspects of Macron and his politics, from his excessive presidentialism to his rhetorical commitment to a more “flexible,” climate-compatible economic model. It also solidified the view, with which Macron has struggled throughout his public career, that he belongs to a “globalized elite” that is insensitive to the struggles of ordinary people. But the lockdown in the spring of 2020—one of the harshest in Europe—stopped all protest in its tracks. As the pandemic wore on, and despite the gradual reopening of French society from summer 2020, criticisms of Macron ebbed away.

“This presidential election, more than any other in recent memory, exposes much deeper transformations that have been taking place in French politics”

It helped that Macron’s biggest political gamble of the pandemic—the introduction of a comprehensive vaccine passport (passe sanitaire) in June 2021—was a success. This was not a foregone conclusion. France was the first country in Europe to adopt a domestic vaccine passport across many sectors of the economy, and it was exactly the sort of unilateral intervention that many French people have come to resent from their state. And yet most French people responded exactly in the way that Macron had hoped, not by pouring out into the streets but by flocking to vaccination centres. Within a few months and after a faltering start, France had one of the highest COVID-19 vaccination rates in Europe.

The pandemic also provided precious few opportunities for political opponents to gain traction. The right and far-right’s inconsistent attempts to harness discontent with the passe sanitaire quickly floundered. And the unprecedented state intervention that was used to prop up the French economy caught the French left completely off-guard. Whereas, in the first few years of his presidency, Macron struggled to shake off his Napoleonic image as the président des riches, his steady handling of the COVID-19 crisis had, by 2022, made him into the archetype of the Gaullist président protecteur.

It is easy to take this transformation for granted, but it is worth remembering that Macron was very inexperienced when he came to power in 2017. He was uniquely unqualified for the job of president, and he faced significant challenges from the right and left of the political spectrum. His ability to cannibalise the different factions on the centre-right and centre-left is reminiscent of François Mitterrand’s well-documented success in eliminating his opponents on the French left in the 1970s and 1980s. One might even want to suggest a parallel between Mitterrand’s re-election campaign in 1988 and Macron’s re-election campaign in 2022.

The difference is that Mitterrand got re-elected by moderating the left and making his party—the Parti socialiste—a formidable electoral vehicle against the right. By contrast, Macron has so monopolised the centre that only the far-ends of the political spectrum are in a position to challenge him.

What happened to France’s political parties?“Macron has so monopolised the centre that only the far-ends of the political spectrum are in a position to challenge him.”

French political parties come and go; they have none of the staying power of their counterparts in other major democracies. Yet rarely have they seemed quite as ephemeral as at present. The issue is not just the party-as-institution, but the political framework to which parties belong: the left-right spectrum.

In 2017, to support his presidential campaign, Macron invented a party—La République en marche, or LREM—out of thin air, while campaigning on the slogan “neither right nor left.” His gambit succeeded, with the help of a perfect political storm, including an unpopular socialist incumbent and the implosion of the conservative frontrunner, François Fillon. Before 2017, seven out of the nine previous presidential races resulted in runoffs between candidates belonging to or supported by centre-left and centre-right parties. In 2017, neither the centre-right Les Républicains nor the centre-left Parti socialiste made it to the second round. Instead, the runoff was between Macron and the representative of the far-right Front National, Marine Le Pen. Macron won by a landslide margin of 66% to 34%.

In 2022, these trends are continuing and solidifying. The Parti socialiste, at least as far as presidential politics go, is in its death throes. As its candidate, it has chosen Anne Hidalgo, who is not only intelligent and politically savvy, but, as mayor of Paris, has more governing experience than any candidate besides Macron. Yet she is polling around 2%—only slightly ahead of candidates calling for a proletarian revolution. As for Les Républicains, they have selected Valérie Pécresse, the head of the Île de France’s regional government. With poll numbers ranging between 10 and 16%, she faces an uphill struggle to overcome Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen, the two far-right candidates, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the main far-left candidate.

The primary beneficiary of this situation is Macron and the political vision he embodies. Thanks to his combination of pro-business policies with an unflinchingly pro-European outlook, he and his party have held on to a segment of centre-left votes—the Parti socialiste, after all, often practiced surreptitiously the policies that Macron is pursuing overtly—while also appealing to some centre-right voters. This tells us something important about the reconfiguration of the left-right spectrum in France. In his classic 1957 study An Economic Theory of Democracy, the economist Anthony Downs argued that parties had an interest in splitting their differences in the political spectrum’s centre, allowing each to claim one swathe of the electorate. Something quite different is happening in France. Macron has monopolized the political centre: he has gobbled up the moderately pro-business and pro-European electorate, leaving a bevy of smaller parties to fight over the less digestible morsels (comprised, in part, of voters who feel disenfranchised and tempted by the extremes).

“Today, the most dynamic parties appear to be nothing more than vehicles for an increasingly personalized political process.”

The role of parties in political life is changing, too. Although de Gaulle famously disdained independent parties and used them simply as a form of parliamentary validation, this was not the norm. Most parties were recognisable coalitions based on ideological affinity and shared interests. Today, the most dynamic parties appear to be nothing more than vehicles for an increasingly personalized political process. Macron’s LREM is the most successful example of this, but the same can be said of Zemmour’s Reconquête!, and, to a degree, Le Pen’s recently rebranded Rassemblement national and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France insoumise. Party-related activities that have long shaped French politics—including internal processes for selecting candidates, recruiting candidates for local contests, or writing the party platform (projet)—are losing their importance. It is not impossible that the traditional coalition party in France will disappear over the next few years.

France’s great moving right showIt is only a slight exaggeration to say that, at least at the national level, the only significant political competition in France is now between factions of the right. The novelty of the current race is the presence of a second far-right candidate, the journalist Zemmour, alongside the old stalwart, Le Pen, whose party (and family) have run in every presidential race since 1988. If one includes Macron, the right side of the spectrum is currently supported by around 70% of the electorate.

But the right’s growing share of the electorate comes with greater competition among the right. Macron’s politics are a complex mix of the French liberal tradition and elements of the centre-left and centre-right, but many of his policies belong recognisably to the playbook of the European centre right, including supply-side economics, pro-flexibility labour market reforms, and a staunchly pro-European outlook. Further to the right, both Le Pen and Zemmour embrace a nationalist, anti-immigrant program. But whereas Le Pen has doubled down on restricting access to citizenship alongside her protectionist and populist economic agenda, Zemmour has emphasized a “civilizational” definition of Frenchness, centred on the country’s Christian heritage, and advocates pro-business policies. Pécresse has struggled to nudge her way into this debate, presenting herself as a bit more nationalistic than Macron, but not as risky as the far-right candidates.

What explains this rightward tilt—this “droitisation” of French politics? First, the Parti socialiste clearly bears some responsibility for the loss of its hegemonic status on the left. Its blending of an increasingly disingenuous rhetoric of social progress with de facto neoliberalism not only undercut its credibility, but also scuttled its ability to unite the left’s multiple constituencies. The disastrous presidency of François Hollande (2012-2017) sealed the party’s fate. Second, as our collaborator Marion van Renterghem has noted, the left has found it hard to find the right approach on a set of issues that clearly preoccupy the French: immigration and the integration of minorities. Consequently, the right’s obsessions have drowned out alternative perspectives. This was brought home in spectacular fashion during the television debate between Pécresse and Zemmour on 10 March. Despite disagreeing over which categories of immigrants to expel and whether Islam should be conflated with Islamism, both candidates took the need for a hard line on these issues for granted.

“It is only a slight exaggeration to say that, at least at the national level, the only significant political competition in France is now between factions of the right.”

Finally, the rightward bias of French politics is a consequence of the obsolescence of parties. Before it collapsed, the Parti socialiste had only to appear slightly left-leaning to capture a significant chunk of the electorate. As it fades into oblivion, its more moderate supporters have shifted their support to Macron simply to find the most palatable option on the political market. Meanwhile, the various parties and social movements of the French left appear to be locked in an internecine struggle that has little relevance to the wider electorate. One only needs to look at the ill-fated Primaire Populaire, which was designed to help select the main candidate of the left, to see how disconnected the concerns of the left and its activists are from the main centre of gravity of this electoral cycle.

The spectre of war in EuropeOne of the most unusual aspects of this campaign has been the brutal eruption of all-out war in Europe. Never before has a French presidential election campaign been so violently interrupted by an unexpected foreign policy crisis. In and of itself, the Russian invasion of Ukraine would have been a major inflection in the campaign, but it was made more acute by Macron’s pivotal role in attempting to negotiate with Vladimir Putin. In less than 48 hours, Macron went from brokering a deal he thought would keep Russian forces at bay to watching helplessly as these same forces poured across the border in the biggest geopolitical disaster for Europe since the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. For several days, there was wall-to-wall coverage on French television of Macron’s negotiations and then the war itself; the presidential election, normally the dominant news item at this point in the campaign, was virtually non-existent.

It is too early to guess where the conflict in Ukraine will go or what its long-term impact on French politics will be. But we do know that it has upended an already confusing presidential race. For Macron, it has been a blessing in disguise. The threat of conflict has only enhanced the image he has been cultivating of the président protecteur, and the exigencies of war leadership have kept him above the fray. He seems not to have been blamed for agreeing a deal with Putin that turned out to be a complete fiction, and he has expertly managed the delicate transition from president to candidate. The word that returns again and again in media coverage of Macron is “intouchable.” He appears untouchable—and his opponents have been left fighting over the scraps.

But the war in Ukraine has also had a direct impact on the opposition. Most obviously, the almost universal public consensus—in France and elsewhere in Europe—that Russia’s war is illegitimate, immoral, and driven by Putin’s personal quest for imperial hegemony poses a serious problem for the far-right. In this respect, the difficulties facing Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen are no different to those facing Viktor Orbán and Matteo Salvini. After years of public support for Putin, they now need to find a way to make people forget their public statements and uncomfortable allegiances. As the war unfolded, Le Pen was the first to backtrack in an effort to stay aligned with public opinion. Zemmour has been slower to recant—and, in some cases, has held fast to his earlier positions. Either way, their association with Putin has turned into a liability.

More generally, the wider issues raised by the war have exposed weaknesses in the central themes of the far-right. The outpouring of sympathy towards Ukrainians is at odds with both Le Pen and Zemmour’s insistence that immigration must be halted at all costs. Meanwhile, the threat of military escalation has made their vocal campaign promise of a disengagement from the EU and an exit from NATO high command appear extremely unwise. A longstanding hostility towards NATO is also a problem for Mélenchon, but the far-left candidate’s anti-imperialist critique appears less compromised than the far-right’s open admiration for Putin.

“There may not be much in the way of suspense, but this election could well turn out to be a key indicator of the ideological and geopolitical world to come.”

It is striking, too, how the war in Ukraine has resurrected domestic issues that had passed into the realm of technocratic management rather than electoral politics. The implications of the war for France’s energy security featured prominently in the “grand entretien” on 14 March, which featured two journalists interviewing the top eight candidates separately in a television studio. All the candidates—including Macron—grappled with the future of France’s civil nuclear programme as a potential response to energy insecurity, and the classic theme of “pouvoir d’achat” (standard of living) was framed almost exclusively in terms of the war. Issues such as food prices, petrol prices, and taxation, which form the bread-and-butter of most French election campaigns, were given a distinctive wartime twist.

Of course, the Ukraine crisis may have no impact on the way the French vote in April. After all, in most democracies, foreign policy questions do not rank highly on voters’ list of reasons for choosing one candidate over another. Nevertheless, the omnipresence of this crisis in the key weeks running up to the election seems likely to inflect certain tendencies. Zemmour’s intransigence and inexperience—previously seen as assets by his electorate—are less likely to be attractive, whereas Macron’s technocratic competence will be enhanced by the surrounding chaos. Beyond these individual narratives, the Ukraine crisis has raised the stakes of this election. There may not be much in the way of suspense, but this election could well turn out to be a key indicator of the ideological and geopolitical world to come.

Featured image by Alice Triquet on Unsplash

April 2, 2022

A more holistic approach to fisheries management: including all the players

Fishing in the United States is a multi-billion-dollar industry. Its importance is reflected in the historical contributions of US fisheries to maritime culture, and certainly in the many iconic seafood dishes found along America’s coasts. From the frigid waters of Alaska, where groundfish and king crabs thrive, to the warmer-water shrimp, snapper, and grouper fisheries of the Gulf of Mexico, the livelihoods of many US residents depend on the sustainability of these species. While consumers may focus their attention on a particular favorite fish or shellfish, populations of these species don’t live in a vacuum. In addition to the direct impacts of fishing, they are subject to effects from multiple environmental stressors and other ocean uses (such as energy, transportation, and tourism) on their ecologies and habitats, while interacting with other species throughout the food web.

In many ways, an orchestra serves as a great illustration of a marine ecosystem, with all components functioning at different levels while still being interconnected. The setting of a single factor influences the whole and its other parts, including how they meld together throughout the system. If one string or reed gets warped or breaks, or the timing of a key element gets shifted, not only does it affect the harmony of the same instruments of a given section, but it has major ramifications across the full ensemble of instruments. All parts need to be conducted (or managed) to minimize discordance, with the functioning of the whole depending on the quality and composition of its parts. These concepts are likewise considered when cumulatively managing the key elements of fisheries systems through ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM).

Thus, EBFM is rapidly becoming the default approach in global fisheries management, with the clarity of its definition and approaches for its implementation sharpening each year in US and international jurisdictions. An EBFM policy for the US is now in effect, with regional implementation plans for all major US marine regions. Fishery Ecosystem Plans (FEPs) are also in development, or have been developed and refined, for all major regions and several subregions. Given these recent advances, there has been a need to evaluate progress and assess the effectiveness and impacts of EBFM. The challenge is to objectively and quantitatively ascertain progress towards EBFM, and ensure wide-ranging applicability of the findings.

For assessing this progress, recent work has illustrated the utility of examining an ecosystem through a socioecological focus. This approach recognizes that a system’s natural and human environments set the basis for the status, quality, and composition of its living marine resources (i.e., fishery and protected species) and marine socioeconomics. Factors like primary production (the growth of aquatic plants or animals that conduct photosynthesis and serve as the base of the food web for most marine life) set foundational limits on the total harvest or economic revenue of a given fisheries system, which need to be considered when managing at the ecosystem level. Environmental and human stressors like climate change, climate oscillations (e.g., El Niño events), overfishing, coastal and offshore development, ocean siting, and many other variables, directly affect future primary production, marine species, coastal communities, and their interconnectivity. EBFM accounts for the effects and interrelationships of these factors within fisheries systems, as well as their trade-offs, to allow for more holistic, improved management of living marine resources.

As with an orchestra’s performance, it’s important to recognize that when we’re out of tune on one factor, it also affects things down the line, at multiple scales, and can potentially throw the system out of harmony. Understanding these effects and working to maintain (or restore) that balance is a key element of EBFM, especially given the many implications for numerous components throughout the ecosystem. While much work still remains to be done in carrying out EBFM, significant progress has been made to better address many of the challenges facing the sustainable management of living marine resources.

Featured image by Kristin Snippe on Unsplash

April 1, 2022

Announcing the winner of the 2022 Grove Music Online spoof contest

Happy April Fool’s Day! I’m pleased to announce that the winner of this year’s Grove Music Online Spoof Article Contest is David W. Barber, for an entry on “L.O.L. Bach.”

This year’s judges were:

Deane Root, Editor in Chief of Grove Music Online, and Professor of Music emeritus, Director and Fletcher Hodges, Jr. Curator of the Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh. Root has been immersed in Grove style since he worked with Stanley Sadie on the first New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.Walter A. Clark is Distinguished Professor of Musicology at the University of California, Riverside, where he is the founder/director of the Center for Iberian and Latin American Music. He serves as Editor in Chief of the Grove Music Online Latin American and Iberian Music Update, a multi-year update and expansion to Grove’s content in that area.Scott Gleason is Acquisitions Editor for Music Reference at Oxford University Press, a position that includes editing for Grove Music Online.Here’s this year’s winning entry by David W. Barber:

Bach, Ludwig Odense Lämmerhirt (b Titz, Germany 29 February 1656; d Feuchtwangen, Germany 29 February 1688)

Westphalian-German krummhornist and composer. Born in the Westphalian town of Titz in the upper Rhine region, L.O.L. Bach is a lesser-known ancestor of the famous J.S. Bach, with whom he shares a double family connection through the Lämmerhirts on Bach’s mother’s side. Scholars are divided on how this double connection came about. Some have decided it’s research best not pursued. L.O.L. Bach studied krummhorn and various other instruments with a local Titz teacher, eventually earning a spot as third-chair krummhornist in the town wind band. He might have had a more promising career on the instrument, but was later expelled from the band for making rude duck noises with the double reed during a ribbon-cutting by the town mayor, who had forbidden Bach to court his daughter. They later eloped (Bach and the daughter, that is) to the Bavarian town of Feuchtwangen and had nine children in quick succession – three sets of triplets. Turning his studies to the clavichord sent Bach off on a tangent to begin composing for the keyboard. A rare surviving work from this period is Die Fugue der Kunst (The Flight of Art), a collection of 11 fugues and preludes (each pair appears in that order, the fugue first, followed by the prelude), each of them in the key of C major. Bach’s keyboard skills being minimal, it was the only key he felt comfortable playing in. His output as a composer would doubtless have been greater had he not died suddenly at the age of 32 after choking on a krummhorn reed he had been moistening before a performance of his Sonata in C for Krummhorn and Clavichord.

Bibliography

A. Chtung, Der Teufel Krummhorn (Wankendorf, 1817)

Judge Clark noted that he “got the biggest laugh out of L.O.L. Bach, with its ‘rude duck noises’ and Die Fuge der Kunst, with its exclusive emphasis on C major.”

Judge Root wrote that the author “has quite cleverly incorporated real if seemingly fictive details: there really is a Bavarian town named ‘Wet Cheeks’ (Feuchtwangen), for example, and J.S. Bach’s maternal family name was indeed ‘Lamb Herder’ (Lämmerhirt). The author’s name in the Bibliography is a good touch. Instrumental humor has long been a source of merriment for orchestral musicians, and this article serves that tradition well.”

For his winning entry David will receive $100 in OUP books and a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online.

Our first runner up was Robert Stein for his spoof entry, La Sorella della Principessa di Malta, ossia nuovi modi per confondere i critici:

La Sorella della Principessa di Malta, ossia nuovi modi per confondere i critici [‘The Princess of Malta’s sister, or new ways to confuse the critics’]

Opera buffa by Luigi Strudello, libretto by Orazio Boggi; Parma, September 1734 (3 act version), Venice S Moisè, 1735 (4 act version), Modena 1737 (1 act version), Modena 1738 (2 act version), Bologna 1755 (5 act version).

The work, as we know from Strudello’s diaries, was intended as a humorous pastiche of 18th century operatic plot devices as well as a gentle satire on the ignorance of the music critics of the day.

However, although implausible dramatic contrivances and characters’ duplicities were conceived as the basis of the opera’s humour, the fraying relationship between composer and librettist explains how confusion multiplied beyond the need for comic effect despite, or because of, frequent re-workings. This might explain both the misalignment of setting, music, character, costume, sets and text and the subsequent duel between Strudello and Boggi.

Following his release from prison in 1753, Strudello revised the opera once more, but the final five-act version – with a revised libretto by Ugo Farfalone – is still largely resistant to synopsis. Bolognese audiences were left so confused that there was no contemporary agreement if the opera’s final scene depicted the heroine Susana’s betrothal, coronation or suicide.

Although the opera – in any of its versions – remained unperformed since 1755, a revival in Utrecht in 1970 in a radically revised version directed by Bart van der Aart sparked some interest in its overture.

Bibliography

Strudello, L. Diari e altre confessioni dal carcere (Rome, 1754)

Burger, H. and Frys, T. C. ‘Laugh? You’re killing me. Strudello, Boggi and the belligerent barons of the Buffa tradition’ in Critical Perspectives on Italian Opera 1705 – 1765 (Baton Rouge, 1988)

Norman Bloor

Judge Clark noted: “Another splendid spoof was La Sorella della Principessa di Malta. This one’s genius has to do with its actual resemblance to a real article, before it goes noticeably off the scholarly rails. Susana’s ‘betrothal, coronation or suicide’ had me in stitches, even as Bart van der Aart’s revival ‘sparked some interest in its overture.’”

For his entry Robert will receive a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online.

Please join me in congratulating David W. Barber and Robert Stein and thanking all those who submitted! We look forward to next year’s contest.

March 31, 2022

A life documented: Winkfield, an enslaved man in colonial Virginia

The odds are long against learning much about any individual among the millions of people once enslaved in America. At the University of Virginia, for example, a monument to the enslaved who built and maintained the university from 1817 to 1865 commemorates some 4,000 workers identified in school records. But fewer than a thousand have names, and most of those lack family names. The rest are noted on the monument by their job or relation, “midwife,” “cook,” “laborer,” and so on. More than 3,000 are remembered only by marks or jobs.

At the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, the case is the same.

With one exception: Winkfield.

As part of a new memorial, a team of historians identified some 180 people that the university either owned or hired, or who were associated with the school during its first 172 years. Some have —Lemon, Adam, Betty, Priscilla—but most are known only by what we call “sightings” in local records: “paid hire a Negro wench 2 years,” “paid Mr Allen hire of a Negro.”

We can recover a few details for some. We know a bit about Joe, for example, from his work assignments, recorded in 1837:

That Joe the College Servant is required to cut four cords of wood weekly during the recess, and that Mr. Pryor the constable be employed to measure such wood and see that this order is fulfilled. Likewise that Joe whitewash and clean the College chambers and Lecture rooms.

And for Lemon, the namesake of the Lemon Project, the College’s investigation into its complicity in slavery and segregation, we have records of his selling produce, of a Christmas bonus to him in 1808, medicine in 1816, and, finally, a coffin in 1817. He is also evoked in a novel by a former student as “Old Lemon,” helpful in a student’s arrival at the College and in running errands, and much remembered for his oyster suppers.

But about Winkfield we know enough to get a sense of his being, his personality, and his stature at the College and in Williamsburg. And, especially striking, we have what are likely his own words affirming an equality with whites.

We don’t know precisely where or when Winkfield was born, but a notation (big reveal to come) in a 30 November 1775 issue of the Virginia Gazette records that he was “the son of Old Liverpool, the ferryman.” A number of ferries plied the waters near Williamsburg, so likely Winkfield was born locally.

College records describe him as helpful, responsible, and respected from at least 1763 to at least 1780, for some or all of that time in charge of the Great Hall.

The Great Hall was the heart of the College, where meals were served and talks, meetings, and concerts were held. Running that enterprise, especially under the demanding scrutiny of multiple masters and students, was a complex undertaking.

The Bursar’s books and the Faculty minutes reveal that Winkfield earned an elevated stature. In two different lists of the enslaved at the College, in 1779 and 1780, his name is at the top—and the 1779 list is of the enslaved that the College will not sell, even at a time of financial stress.

Even more telling is his apparently receiving a supplementary payment for stepping in during the summer and fall of 1763, seemingly a reward for helping overcome a staffing problem recorded in the Faculty Minutes. One entry notes that Winkfield received a payment, 6 September 1763, of £6: “pd. cook ^in part for wages pd. Winkfield.” A further entry the same month, 23 September 1763, records a second payment: “By Mr. Nicolson, the house keeper by order of the Presidt, paid to Winkie 10 [pounds].”

On 23 July 1763, the housekeeper, Mrs Isabella Cocke, having “behaved much amiss in her Office,” was fired and replaced temporarily by the Steward, James Nicolson, until the appointment of Mrs Garrett, 8 November 1763. Nicholson was “allowed the usual Salary of Housekeeper for his Trouble.” It appears that Winkfield was helpful to Nicholson during a difficult time, especially because of his work at the Great Hall, which gave him some working connection with those in the kitchen beneath.

Several years later Winkfield was twice entrusted to deliver large amounts of cash, virtually a year’s wages, to Samuel Klug, a sub-usher (and then usher) at the College: an 8 December 1766 entry records a payment, £51, cash, “(sent per Winkie).” A similar entry is also for cash, £60: 30 July, “Do. [Cash] Sent him on his note per Winkie.”

Thomas Jefferson, who likely knew Winkfield from his own years at William and Mary (1760–1762), turned to him in October 1772. Jefferson’s brother, Randolph, was quitting the College, and Jefferson records in his papers, “Pd. Winkfeild [sic] at College for R. Jefferson for findg. knives & forks, cleaning shoes &c. 22/6 as per acct. & rect.” (in his fee book Jefferson records the payment to “Winkey at College”).

But the strongest testament to Winkfield’s stature comes when he is directly addressed in that 1775 letter in the Virginia Gazette. The writer, possibly one of the faculty at William and Mary, addresses him with an honorific and attests to his character:

To Mr. WINKFIELD. Superintendent of the hall of William and Mary college. No one, of your colour, has ever established a more respectable character than yourself…. you have ever been distinguished for your spirit and candour. I myself once knew you did possess these excellent qualifications in no small degree.

Though this is the last of Winkfield’s appearances in all known records (and here comes the promised big reveal), we have one last glimpse of him thanks to Samuel Henley. Henley would have known Winkfield well from their daily interactions in the Great Hall; Henley taught at William and Mary from 1770 to 1775 before he returned to England, where he made his mark as an antiquarian.

And in that role, Henley added a note to a 1785 edition of The Merchant of Venice where the Prince of Morocco proclaims, “Bring me the fairest creature northward born, / Where Phoebus’ fire scarce thaws the icicles, / And let us make incision for your love, / To prove whose blood is reddest, his or mine” (II, I, 4-7).

In his note, Henley quotes “a negro slave in Virginia,” clearly a man of “spirit and candour,” in his blunt asservation of equality. It is surely Winkfield who replies to Henley’s interrogation:

to try his acuteness, I had asked, ‘—How it happened that, as Adam and Eve were white, he, their descendant should be black?’— His reply was: ‘I don’t know: but, prick your hand and prick mine, my blood is as red as your’s [sic].’

Feature image: William & Mary College, Williamsburg, USA by Mateus Campos Felipe. Public domain via Unsplash .

Scientific myopia: proof triumphs over conviction in the study of yellow fever

The Oxford Advanced American Dictionary lists one entry for myopia as “the inability to think about anything outside your own situation.” We likely are all guilty of myopic thinking to one degree or another. We likely all are equally guilty of believing we are keeping an open mind and are not myopic. And, really, in most everyday events, myopia doesn’t rise to the level of causing harm. It may prevent us from thinking things through, to consider consequences of our actions or beliefs, or may cut us off from what could be new experiences. No harm, no foul.

However, myopia in science is not so simple, nor so benign. Consequences can be huge. Preconceived ideas are not the problem. After all, an initial idea forms the basis of a hypothesis to be tested. An idea is posited and an appropriate test is made to support or reject the hypothesis. Hypotheses are never proven, at least not if science is practiced openly and thoroughly; they are falsified, not proven.

The problem occurs when testing hypotheses is not done well—or not done at all. When jumping to a conclusion, based on a “gut feeling” or one’s background, precludes open scientific inquiry. And that sort of approach can cut off productive directions of investigation, delaying or even preventing finding solutions. In the case of medical inquiry, in which cause or treatment for a disease are sought, delays caused by myopia can kill people.

Yellow fever: Dr George M Sternberg and Dr Carlos FinlayIn the late 1800s, yellow fever epidemics were near-annual occurrences, killing thousands throughout the Americas. One source of infection for the United States seemed to be Cuba, with its shipments of goods and people into the southern states. When infections reached military bases, the ensuing illnesses and deaths caught the attention of military medical professionals, to seek solutions that would protect troops.

Dr George M. Sternberg was a figure larger than life. After receiving his medical degree in 1860, he was appointed assistant surgeon in the US Army. He served in the Battle of Bull Run, where he was captured, later escaping. In military postings after the war he contracted and survived infections from both typhoid fever and yellow fever, with his scientific publications on the latter earning him status as a leading expert on the disease. His use of the latest technology allowed him to use photomicrography to study the blood of yellow fever patients and his expertise as a bacteriologist landed him a role as one of the members of the 1879 Havana Yellow Fever Commission. In 1893, he was named by President Grover Cleveland as US Army Surgeon General and promoted to Brigadier General.

By all accounts, Sternberg was a careful observer, a good scientist, a decent person. He was a pioneer in the field of bacteriology and his expertise earned him world acclaim. Along with Louis Pasteur, he announced the discovery of pneumococcus as the cause of pneumonia, and he demonstrated that bacteria caused typhoid fever and tuberculosis. Germ theory ruled the day. In the vernacular of today, Sternberg was at the top of his game.

But he also suffered from scientific myopia.

Sternberg was a bacteriologist, one of the best in the world. His discoveries still benefit humanity. Sternberg spent long hours at the microscope and produced more than 100 photomicrographs of the blood of yellow fever patients. Because of his training and background, he knew that yellow fever was caused by bacteria, with his conviction bordering on obsession. Despite his efforts and determination, he failed to find the causal bacteria. Germ theory explained many of the maladies of the day, but no one understood that there were pathogens smaller than bacteria, so small that they could not be detected by the microscopes of the late 1800s. His obsession with bacteria forced him to miss the clues that were there in front of him. He failed to find the bacteria that caused yellow fever because the disease was not caused by bacteria. Because of his convictions, Sternberg failed to test hypotheses. Instead, he sought to prove his ideas.

Dr Carlos Finlay, Cuban physician and fellow Havana Yellow Fever Commission member, had been equally obsessed. But his obsession was with mosquitoes as the means of spread of the disease. He didn’t know about bacteria, and viruses were not even conceived of in the years he proposed mosquitoes as the source of infections. But he used experiments to test his hypotheses. Not perfect experiments, by any stretch. But experiments, nonetheless.

Finlay’s ideas and evidence were ignored for more than two decades, while Sternberg’s ideas were followed. Whether it was due to Sternberg’s stature and experience and Finlay’s relative obscurity is open to conjecture. But the twenty-year delay in finding the causative agent of yellow fever, a virus carried by mosquitoes, caused the deaths of countless people, military and civilian alike. Certainly, many of those deaths can be attributed to scientific myopia.

Sometimes what we know to be true is not so, and the inability to think about anything outside our own situation keeps us from finding the truth.

Feature image by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org via Wikimedia

March 30, 2022

Osteological folklore: “bonfire”

Deep are the roots of the oldest words. Who coined earth? Someone who dug-dug-dug and said er-er-er? Slang is also tough. Who coined tizzy? Someone who was in a swivet and felt dizzy-tizzy? We resigned ourselves to the fact that most of old words and of old and late slang came from “nowhere” (“origin unknown”). My today’s word is bonfire, which turned up in texts at the end of the fifteenth century. Seven years ago, I devoted a post to it (“Dancing around a bonfire”),and it was followed by a few comments, but today I know more about this tricky compound and can write the story in a different way, even though, as a matter of course, I will refer to some of the same sources.

Samuel Johnson, the author of the famous 1755 dictionary, did not doubt that bonfire means “good fire”: the first half of the word allegedly came from French, the second from English. Johnson, an outstanding lexicographer, knew very little about etymology (not that in 1755 there was too much to know about this subject) and copied his information from the 1671 dictionary by Stephen Skinner, who wrote in his entry: “Ignis bonus…”. Johnson’s etymologies were improved by John Todd in the 1818 edition (usually referred to as Johnson-Todd; incidentally, a very useful source). Much to his credit, he believed that bon– in bonfire goes back to bone. Nor was he the first to thinks so. As early as 1725, Henry Bourne, a curate from Newcastle upon Tyne, wrote that according to Belithus (known to modern scholars as “a ritualist of old times”), “to prevent the Infections before mentioned, they were wont to make on (sic) Fires of Bones, that the Smoke might drive away the Dragons” (quoted here from Bourne’s Antiquitates Vulgares; or the Antiquities of the Common People; in the Latin text, no dragons are mentioned: just “animals of this sort,” with reference to the previous statement).

Are bones the fuel here?

Are bones the fuel here?(By Nikodem Zieliński via Wikimedia Commons)

Other more or less fanciful suggestions about bon– in bonfire abound. It has not too rarely been traced to Dutch bonne “district” (sometimes “village”), as though a bonfire were a fire typical of some one place: “Bon-fire means then properly district fire. A bon-fire is a fire to celebrate festivals, and, in case of general rejoicing, each district would have, indeed has, its own bonne-fire.” One wonders how those people imagined the process of coining hybrid compounds. What could make speakers of provincial English take a noun from Dutch and add another noun from English to produce bonfire?

The editor of Notes and Queries once wrote: “…there can be no doubt that the word Bon is from the Danish Baun, a beacon.” Amazingly, Hensleigh Wedgwood, the author of a once widely used dictionary of English etymology (1859; two more editions), adopted this idea. Time and again one encounters the phrase no doubt introducing the most nonsensical conclusions. As a curiosity, I may add that bon– has also been traced to boon or rather boons: bonfire emerged as a fire “made of materials obtained by begging.” Reference to Welsh ban “lofty, conspicuous” has also turned up in the literature. A surprisingly late (1977) fantasy derived bon– in bonfire from Old Icelandic bana “murderer,” the source of English bane. So much for refereed journals. (Other than that, my sources are articles in Notes and Queries and The Athenæum between 1858 and 1903.)

Long before the OED received its name, it was referred to as English Dictionary of or prepared for the Philological Society, and quite early, almost all the hypotheses mentioned above were known to those who worked on the great project. With regard to bonfire, Robert W. Griffith summarized the state of the art in 1866. Peter Gilliver, the author of a definitive book on the making of The Oxford English Dictionary, probably knows who Robert Griffiths was and what role he played in the Society’s work. The University of Minnesota, where I teach, owns his book, but someone is reading it, and I could not look up Griffith.

A bone of contention.

A bone of contention.(Via Pxfuel, public domain.)

A thoughtful contributor to Notes and Queries supported the bone-fire idea but asked: “Did bones originally form the principal material for the fire, and give it the name it bears?” This is undoubtedly the main question in the present context. Many people tried to find a religious explanation for the word bonfire. The following is from Daniel Garrison Brinton, a nineteenth-century polymath and folklorist:

“Bones were burned as symbolic of a sacrifice… To this day [1890], in the remoter parishes of Munster and Connaught great fires are lighted on St. John’s eve, in each of which a bone is burnt, a survival of the sacrifices which once celebrated the midsummer night and the summer solstice. The bone in the bonfire was something more than a symbol. Its presence grew out of and illustrates the deepest and most remarkable phase of osteological folk-lore. It represented the animal or man burned in the ancient sacrifice, because the notion is nigh universal in primitive mythology and modern superstitions that the immaterial part of creatures, their indestructible element or soul, is connected with or resident in the bones.”

(Bred in the bone?) The rest of that paper is also interesting. See Notes and Queries, March 29, 1890, p. 259. Brinton may have been right, but in this case religion and economy are sometimes hard to separate. Parties of boys used to range the fields in search of bones for the fires that were lighted on the eve of St. John (23 June), because bones were supposed to yield enough oil, to revive the illumination toward the close of the display. No religion here.

The captain of our souls?

The captain of our souls?(By svetjekolem on Unsplash)

Yet Walter W. Skeat also once suggested that bonfire refers to the practice of burning the relics of saints. I don’t know what evidence he had for that conclusion, but one of the correspondents to Notes and Queries made an important point. If bonfire goes back to burning bones, why did the word appear in English so late? Skeat defended his etymology and ridiculed the idea that bone in bonfire goes back to bail, Baldr, or Bel, and “all the old rubbish” but never discussed the word’s chronology. Indeed, why did bonfire not turn up before the reign of Henry VIII? I have recently posted two blog posts on the origin of soul (part one; part two). Perhaps we should try to associate soul with a more solid substance than breath, butterflies, and their likes?

Those of our readers who know Russian will remember the word kostyor “bonfire” (stress on the second syllable). Kost’ means “bone,” but the root of kostyor has nothing to do with bones. The etymology of English bonfire is settled: this compound goes back to bone-fire. The vowel of bone– was shortened, as also happened in such compounds as Monday “Moon-day,” Christmas (as opposed to Christ), and so forth. But a few puzzles have not been solved. In the Modern English noun balefire, bale– is a remnant of the old word meaning “fire,” “funeral fire,” and “bonfire.” For some reason, this word went out of use, and bone-fire took its place. Why? What event in people’s religious life or customs resulted in the triumph of the newcomer? The unwieldy word must have been frequent enough in popular speech, for had it occurred rarely, its root vowel would have withstood shortening. It is those unanswered (hardly ever asked) questions that made me return to my old essay.

Featured image by Delphine Ducaruge on Unsplash

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers