Oxford University Press's Blog, page 84

March 2, 2022

Religious terminology continued: bless your heart, my dear!

From God (or rather, god) to bless. But before turning to the history of the word bless, I would like to respond to the questions asked in connection with the good God dilemma (see the previous post). It might be better to leave the answers for my next gleanings, but I receive comparatively few letters and comments, so that the gleanings, meant to be a monthly affair, now appear at irregular intervals. Therefore, I’ll ignore the proverbial back burner and begin with the digression.

Good and godAs I wrote, until the beginning of the nineteenth century, etymologists considered good and god to be related. The question was: “Who are those etymologists?” Before Rasmus Rask and Jakob Grimm—the founders of modern historical linguistics, that is, of the comparative method—etymology was an exercise in intelligent (sometimes, very intelligent) guessing. Also, journals, both scholarly and popular, began to appear, just a trickle first, only around the time when Rask and Grimm brought out their foundational books. The earliest English etymological dictionaries were published in 1617 (John Minsheu), 1671 (Stephen Skinner), and 1743 (Franciscus Junius). All three were written in Latin. Those authors did not insist on the kinship between god and good but mentioned the possibility of their relatedness.

Rasmus Rask, 1787-1832, a linguistic genius and a polyglot (a rare mixture: most modern linguists don’t study languages: they explore LANGUAGE)

Rasmus Rask, 1787-1832, a linguistic genius and a polyglot (a rare mixture: most modern linguists don’t study languages: they explore LANGUAGE)(Via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The statement from Noah Webster, quoted in the previous post, is correct. I also referred to Walter W. Skeat, who fought the good/god etymology in all the editions of his dictionary. Later, popular journals flooded England and the United States, and still later, numerous philological periodicals appeared. The word god has been discussed multiple times. The incompatibility of the vowels in god and good seems to make further discussion fruitless.

In principle, there is nothing impossible in having positive connotations in the word for “god,” despite the fact that pagan gods were rarely or never looked upon as benevolent. For example, Slavic bog– “god” has the same root as the word for “rich.” Though it sounds like the Iranian word for god, it need not be a borrowing. But it also resembles Engl. bug (as in bugbear). Slavic bog– predates Christianization by many centuries. At that time, the Slavs had no concept of one Supreme Deity. Though as a general rule, the invisible forces above were feared, rather than thanked for their generosity, exceptions are of course possible. As far as I know, Slavic bog– and the numerous b-g words for evil creatures all over Eurasia have almost never been compared. In any case, let me repeat: from the linguistic point of view, god and good have different roots. The English-Greek pair good-agathós should also be left in peace for the reasons given last week. Agathós has experienced a semantic shift comparable to the one observed in Germanic: from “efficient, proper”—a frequent epithet in Homer—to “pleasant, nice.” This conclusion is the result of a detailed study of Classical Greek by generations of specialists, rather than a product of anyone’s scholarly bias (see the comment on the previous post).

Perun, the Slavic thunder god. His name is related to Latin quercus “oak.”

Perun, the Slavic thunder god. His name is related to Latin quercus “oak.”(12th century figurine from Veliky Novgorod by Driewenij Novgorod, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another reader and my old correspondent pointed out that the Germanic word for “good” has a close counterpart in Hebrew and Aramaic. He, if I am not mistaken, suggests that there is some affinity between Germanic and Semitic here and refers to Ernest Klein’s etymological dictionary. Every time we encounter monosyllabic words beginning with and ending in a voiced stop (b, d, g), we observe similar meanings attached to them across language borders. I am not quite sure what my answer should be. Common heritage? Borrowing? A thought-provoking typological coincidence? My attitude toward Klein’s dictionaries of Hebrew and English is less than enthusiastic. In any case, one should consult the two-volume book by Saul Levin Semitic and Indo-European.

Finally, a correspondent referred to my statement that before Christianization, Europeans had no idea of monotheism. My statement, he pointed out, ignored the religion of the Jews living in Europe in the early Middle Ages. He is right, and I should have modified my formulation accordingly. I would like to thank this reader of the blog for his remark and for the friendly tone of the letter. Usually those who disagree with what I say are irritated by my ignorance and recalcitrancy and, contrary to me, know the ultimate truth.

The origin of the verb to blessNow, the origin of the verb to bless (Old Engl. blēdsian). This was an important item in the early vocabulary of the converted Anglo-Saxons, and one could expect that it would owe its origin to Latin. Such is the situation in German (segnen) and Dutch (zegenen), both from Latin signare “to make a sign.” The Old Icelandic verb was borrowed from English. I am now returning to Minsheu, our first English etymologist, who at bless mentioned Latin benedicere “to bless.” The entries in his dictionary are a mixture of putative cognates and synonyms, so that one often wonders how to appraise them. Did he really derive bless from benedicere? Considering the level of etymological knowledge at the beginning of the seventeenth century, today this question might not even have been worth asking if Friedrich Kluge, one of the luminaries of Germanic philology, had not indeed derived Engl. bless from benedicere.

Kluge, I suspect, had no access to Minsheu, but he would hardly have consulted such a source even if he had been aware of its existence. He opened his short note (1923) with the following statement: “No etymologist has probably made bold to equate Engl. bless with benedicere.” It is easier to find a needle in a haystack than a note on the origin of an English word. Greek and Latin etymological research has been systematized quite well. In the past, the two Classical languages were researched so meticulously that for a long time, linguistics was a synonym of Greek and Latin scholarship. By contrast, Germanic has been seriously studied for three centuries at most. There now exists a huge bibliography of English etymology, but not of German or French, or Russian. And even in the English volume, words are listed with reference to thousands of articles, not books. If you have a new hypothesis about the origin of a word outside Greek and Latin, never presume that you are the first to offer it. You may not even be the second.

This is a modern idea of a bugbear. Hardly a divinity, but it takes all sorts.

This is a modern idea of a bugbear. Hardly a divinity, but it takes all sorts.(Mike Ploog via Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Kluge’s derivation of bless is, most probably, indefensible. He cited a few cases of n becoming l in Germanic and elsewhere, but the difference between benedicere and Old Engl. blēdsian is too great to justify his idea, though we may have to return to it in the future. I don’t think that Kluge’s reconstruction has found any support. Apart from the benedicere—bless comparison, for many years, English lexicographers attempted to trace bless to blithe and bliss. Blithe “joyous, carefree, happy-go-lucky” is today rather rare, but blithely does occur, more often in an ironic context, as in “blithely unaware of the danger” and the like. However, the root vowel of blithe was long i (ī), like the vowel in Modern Engl. be, fee, see, while bless has always had e. Short e and long i did not alternate in the same root. We have here the same type of obstacle that drove a wedge between god and good.

What then is the origin of bless?

To be continued.

Feature image by Raimond Klavins on Unsplash

Healing conversation in medical care

Every day thousands of people have conversations with healthcare providers (HCPs) about their medical condition. Such meetings can be profoundly comforting or extremely distressing to the patient and caregiver. This medical encounter by Carla and her mother-in-law illustrates the latter.

When Carla accompanied her shy mother-in-law Jean for a follow-up visit after treatment for ovarian cancer, she expected kind, considerate, and clear communication. Jean had suffered through her chemotherapy, which actually made her feel worse than her cancer. However, what she saw was a distracted doctor, standing at the computer, hurriedly going over tests, using medical jargon, and making little effort to connect with and listen to Jean. Carla watched patiently hoping for a sign of empathic concern from the doctor. When she tried to clarify something the doctor said, her question was disregarded. The meeting included hopeful information. However, it was delivered in a way that left Jean feeling informed but not cared for. They both left the meeting disappointed even though the news she received was good, as the treatment was effective and Jean’s cancer had not progressed.

In this example of a disappointing medical appointment, the basic elements of a healing conversation, listening carefully and responding honestly and thoughtfully, were missing, even though the information imparted was good news. The outcome went beyond the meeting itself and resulted in a damaged relationship between Carla, Jean, and her doctor.

Healing conversation: definition and basic elementsA healing conversation (HC) is one in which the patient feels cared for, heard and where suffering is addressed. It can be a positive emotional experience at a time when the patient may have physical symptoms that cannot be completely eradicated or a chronic illness that can be managed but not cured. It is an encounter where the patient experiences relief of suffering due to the care, prescription, and information provided by the HCP. For example, in cancer medicine, fatigue may be caused by the treatment itself rather than disease progression. Patients who learn their fatigue is secondary to chemotherapy and not cancer will likely receive some relief from that information alone since the meaning of the symptom has changed. Of course, treatment that solves the problem of debilitating, nagging fatigue will also help. In fact, almost all medical encounters involve a problem-solving component. However, it is the empathic concern of their provider, the key to healing conversation that can make all the difference. These conversations can be simple when medical problems are easily identified and cured, such as an ear infection requiring medication. However, the more complex conversations involving a life-threatening or chronic illness exposing a patient’s vulnerability require and benefit from deep listening and a trusting relationship.

Two elements in good communication form the foundation in HC. The first is active, deep listening where the listener makes an effort to hear the words, the feelings expressed, and their meaning. Yet, it is not sufficient to hear the patient; the hearing must be communicated to and felt by the patient. One method of demonstrating this is to reflect empathically the content and emotional tone of the patient. This is done with words as well as physical and emotional presence. In order to listen carefully, the HCP needs to be in the moment with the patient, to make the “click of contact” by looking and seeing the patient. It is likely that Jean felt overlooked when her HCP spent so much time focused on the computer. Among other good outcomes, when the HCP is a good listener and communicator, patients are more likely to listen to what is said. Not only does thoughtful communication heal emotionally, it has the potential to facilitate physical healing as well. The type of HC emphasized here reduces patient suffering.

The second element is responding thoughtfully and honestly. This may be the more challenging element in HC as honesty often requires giving information that is alarming, such as news that the patient’s illness has not responded to treatment. The manner in which this distressing information is given reflects the training and thoughtfulness of the clinician. In academic medical centers, communication-training programs have been developed to enhance relationship and provider skills (see the Academy of Communication in Healthcare’s Communication Rx, for example). One physician uses the phrase “I am afraid the news is not good” rather than “I have bad news for you”. Choosing words carefully is part of the thoughtfulness as well because words can hurt or heal. How words are given to patients can make all the difference in the world. Words well spoken can help balance realism and hope in any medical encounter. While the facts of the matter (the treatment is not working as well as hoped) may not be altered by the method of the delivery, how patients experience such information can be tinctured with the hope that comes from future possibility, even when that means what was originally hoped for (cure) must now change to managing a chronic condition.

A skilled HCP alone cannot create healing conversation. Any conversation is created by its participants. Therefore, the possibility of healing in such encounters depends not only on a perceptive professional provider but on patients as well and their ability and interest in dialogue where honesty and kindness meet the reality of the situation. Difficult medical conversations can also be healing conversations, even when they hurt.

Encounters in the doctor’s office do not always result in healing dialogue. However, careful listening combined with honest and thoughtful responding in a trusting relationship improve the likelihood that patients can experience even difficult encounters as healing. If a majority of these appointments could be informed by deep listening and the quality and skill of empathy, imagine the reduction in suffering that could occur in a busy medical practice every day.

Featured image by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

February 28, 2022

How well do you know your library quotes? [Quiz]

Do you know what Neil Gaiman once said about librarians? Or remember Mr Darcy’s opinion on libraries in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice? Perhaps you share Sir Francis Bacon’s taste for books?

The famous quotes about librarians, libraries, and all things bookish in our quiz have either featured in renowned novels or have been articulated by influential people throughout history.

Think you’ve got what it takes to complete these quotes? Give our quiz a go and tweet us how you did at @OUPLibraries. Good luck!

The quotes featured in our quiz have been derived from either Oxford World’s Classics or Oxford Reference from Oxford University Press:

Interested in purchasing these products for your institution? Contact us at library.marketing@oup.com for more information.

February 26, 2022

Why does justice for animals matter?

The health and environmental crises of the past two years have taught us that our lives are increasingly connected across nations and generations. Many of our current activities are not only harming vulnerable populations but also contributing to global health and environmental threats that harm us all. And when disruptions occur, they disproportionately impact the most vulnerable among us. Thus, many of us now appreciate, pursuing health and climate justice requires pursuing social and economic justice too. And in the same kind of way, I believe, pursuing justice for humans requires pursuing justice for animals too.

Of course, justice for animals is important for its own sake. Humans kill trillions of animals per year, often unnecessarily. For instance, we kill more than 100 billion farmed animals and an estimated 1-3 trillion wild animals for food each year, in spite of the fact that we increasingly have access to humane, healthful, sustainable plant-based foods. We also kill countless captive and wild animals every year for research, clothing, and entertainment, as well as through habitat destruction, “pest” control, and air, water, and noise pollution. We need to reduce these harms as much as we realistically can simply for the sake of our nonhuman victims.

But justice for animals is important for our sakes as well. Industries like factory farming, deforestation, and the wildlife trade not only kill trillions of animals per year but also increase the risk of global health and environmental threats like pandemics and climate change. For instance, since factory farming keeps animals in crowded, toxic conditions and administers high quantities of antimicrobials, it contributes to health threats like bacterial and viral outbreaks. And since it consumes so much land and water and produces so much methane and nitrous oxide, factory farming contributes to environmental threats like climate change too.

And when outbreaks or extreme weather events occur, they can impact animals as well. For instance, many animals have died during COVID-19, either because they were exposed to the virus or because they were exposed to violence or neglect from humans, who viewed them as “vectors” or were unable or unwilling to care for them. Similarly, many animals have died during recent floods, fires, and other extreme weather events, either because they were exposed to the extreme weather or, again, because they were exposed to violence or neglect from humans, who viewed them as “invasive” or, again, were unable or unwilling to care for them.

There are more basic links between human and nonhuman justice too. While human and nonhuman oppressions are different in many ways, they all stem in part from our basic tendency to construct in-groups and out-groups, and to then favor policies that benefit in-groups more than out-groups. Additionally, part of how humans oppress other humans is by comparing them with nonhumans who are presumed to be “lesser than” because of social, biological, physical, or cognitive differences. In these respects, too, efforts to end human and nonhuman oppressions are not only independently important but also mutually reinforcing.

What can we do to achieve justice for animals?While many basic changes will be necessary to address these harms, we can make three general observations for now. First, we need to reduce our use of animals as part of our pandemic and climate change mitigation efforts. Reforming industries like factory farming, deforestation, and the wildlife trade is not enough to limit the damage to animals, global health, and the environment. We need to reduce our support for these industries and increase our support for alternatives as much as we can, for instance by divesting from factory farming and investing in plant farming, plant-based meat, and cultivated meat instead.

Second, we need to increase our support for animals as part of our pandemic and climate change adaptation efforts. Our current infrastructure is designed to accommodate some humans more than others and is also designed to accommodate humans more than nonhumans. As we work to build a more resilient and sustainable infrastructure, we need consider the interests and needs of humans and nonhumans alike. This will allow us to co-exist with other animals more successfully in the future, and it will also allow us to harm them less and help them more not only during normal times but also, and especially, during disruptions.

Third, we need to do this work holistically, structurally, and comprehensively. When we consider human and nonhuman needs holistically, we can find shared solutions to shared problems. When we consider our needs structurally, we can create social, political, economic, and ecological structures that make it easier for everyone to build resilience against the threats that we face. And when we consider our needs comprehensively, we can build resilience not only against, say, outbreaks and extreme weather events, but also against the ordinary threats like hunger, thirst, illness, injury, violence, and neglect that these disruptions can amplify.

When we consider how much progress we still need to make for humans, the idea of making progress for other animals too might seem premature. But it would be a mistake to wait until we achieve justice for humans to pursue justice for other animals. Both projects are important, and we can make progress on them more effectively and efficiently when we pursue them together. We should thus broaden the search for justice now by considering the interests and needs of everyone impacted by our activity and by seeking to build shared structures that can accommodate all of us, rather than only the privileged few.

Featured image by Jorge Maya on Unsplash

February 25, 2022

The VSI podcast season three: ageing, Pakistan, slang, psychopathy, and more

The Very Short Introductions Podcast offers a concise and original introduction to a selection of our VSI titles from the authors themselves. From ageing to modern drama, Pakistan to creativity, listen to season three of the podcast and see where your curiosity takes you!

Ageing

In this episode, Nancy A. Pachana introduces ageing, an activity with which we are familiar from childhood, and the lifelong dynamic changes in biological, psychological, and social functioning associated with it.

Listen to “Ageing” (episode 43) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

PakistanIn this episode, Pippa Virdee introduces Pakistan, one of the two nation-states of the Indian sub-continent that emerged in 1947 but has a deep past covering 4,000 years.

Listen to “Pakistan” (episode 42) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Henry James

In this episode, Susan Mizruchi introduces American author Henry James, who created a unique body of fiction that includes Daisy Miller, The Portrait of a Lady, and The Turn of the Screw.

Listen to “Henry James” (episode 41) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

SecularismIn this episode, Andrew Copson introduces secularism, an increasingly hot topic in public, political, and religious debate across the globe that is more complex than simply “state versus religion.”

Listen to “Secularism” (episode 40) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Demography

In this episode, Sarah Harper introduces demography, the study of people, which addresses the size, distribution, composition, and density of populations, and considers the impact certain factors will have on both individual lives and the changing structure of human populations.

Listen to “Demography” (episode 39) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

PsychopathyIn this episode, Essi Viding introduces psychopathy, a personality disorder that has long captured the public imagination. Despite the public fascination with psychopathy, there is often a very limited understanding of the condition, and several myths about psychopathy abound.

Listen to “Psychopathy” (episode 38) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Modern drama

In this episode, Kirsten Shepherd-Barr introduce modern drama, the tale of which is a story of extremes, testing both audiences and actors to their limits through hostility and contrarianism.

Listen to “Modern drama” (episode 37) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

SlangIn this episode, Jonathon Green introduces slang. Slang has been recorded since at least 1500 AD, and today’s vocabulary, taken from every major English-speaking country, runs to over 125,000 slang words and phrases.

Listen to “Slang” (episode 36) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

CreativityIn this episode, Vlad Glăveanu introduces creativity, a term that emerged in the 19th century but only became popular around the mid-20th century despite creative expression existing for thousands of years.

Listen to “Creativity” (episode 35) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

New York City: The Great Fire of 1835

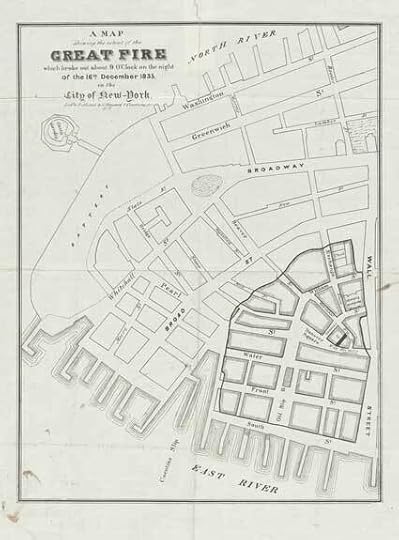

In the 1830s, New York was a small city. While the island of Manhattan had a prosperous community at its southern end, its northern area contained farms, villages, streams, and woods. Then on the evening of 16 December 1835, a fire broke out near Wall Street. It swept away 674 buildings and though the devastation seemed absolute, citizens quickly rebuilt. They pushed development up the island, so that by the Civil War homes lined the streets near the new Central Park.

Learn about the Great Fire of 1835, and the city that existed before and grew after that blaze in this series of blog posts from Daniel S. Levy, author of Manhattan Phoenix: The Great Fire of 1835 and the Emergence of Modern New York.

The Great Fire of 1835All day on 16 December 1835, a gale blanketed Manhattan with snow. The Pearl Street merchant Gabriel Disosway remembered how when night fell it was “the coldest one we had had for thirty-six years.” At nine that evening, members of the City Watch discovered a fire burning at Comstock & Andrews, a brick dry goods store on Merchant Street. Officer William Hays recalled how “We found the whole interior of the building in flames from cellar to roof… Almost immediately the flames broke through the roof.”

Chief Engineer James Gulick and fire crews raced to the blaze. Firemen tapped the nearby hydrants. In search of more water, crews headed to the foot of Wall Street to break through the ice on the East River and pump water. But it was so cold out that when they got the water moving, the strong wind slapped it back into their faces.

Lower Manhattan was filled with crooked streets, and within 15 minutes of the alarm, Watchman Hays realized that “fully fifty buildings were blazing.” Merchants desperately sought for places to move their goods before they were destroyed. Throughout downtown Manhattan—for a third of a mile from Broad to South Streets and a similar distance down to Coenties Slip—businesses emptied their buildings and piles of mahogany tables, sideboards, sofas, silks, satins, broadcloths, boxes of cutlery, and crates of expensive wine littered the streets. A prominent spot on the city’s eastern edge was the triangular-shaped Hanover Square through which Pearl Street ran. But as merchandise piled up, people streamed through and they trampled fabrics into the snow and mud, broke furniture, splintered boxes, and scattered bottles. Then, according to the Sun, “a gust of flame, like a streak of lightning,” came from the northeast corner building, and it shot “across the square, blown by the strong wind, and set fire to the entire mass, which it in a few moments consumed to cinders, and then communicated to the houses opposite.”

[image error]Soon after the Great Fire, William and Henry Hanington unveiled their depiction of the blaze, a moving diorama accompanied by flashing lights, the sound of rattling fire engines and the shouts of citizens.(The Great Fire: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By 10 PM, everything seemed to be engulfed: “The bells ringing—the fire engines rolling—the foremen bawling—the wind blowing—the snow driving—the whole heavens above illuminated, formed altogether a terrific spectacle,” reported the New York Herald. It didn’t help that many of the firemen were exhausted from fighting fires on Water and Chrystie Streets from the night before. To compound matters, those fires had largely drained the city’s reservoir, and made it impossible to get enough pressure to shoot the water high enough.

Since there seemed to be little else that they could do, Gulick ordered his men to assist businessmen and others in rescuing goods. Soon, though, the South Reformed Dutch Church, which stood south of Wall Street and was seen as a safe place to store goods, caught on fire. As the church burned, organ music wafted out with the billowing smoke. The organist, wrote Disosway, had “commenced performing upon it its own funeral dirge.” Then, reported the Star, “The bright gold ball and star above it on the highest point of the spire, gleamed brilliantly.” The organ music only stopped when the ceiling took fire. Then the steeple “gave one surge and fell in all their glory into the heap of chaos beneath them.”

“The blaze indiscriminately destroyed the grand Merchants’ Exchange, homes, churches, banks, and stores, the heat so intense it melted metal shutters, doors, roofs, and gutters.”

The Journal of Commerce’s office stood near the church. Seeing what happened to the sanctuary, editor Gerald Hallock felt it “prepared us fully to expect a similar fate.” He and his staff emptied the office as best they could. By luck, Thomas Downing, the African American restauranter whose popular oyster house stood on Broad Street, noticed a hogshead of vinegar in a shed. The cold had not frozen the liquid, so Hallock, Downing and others carried around pails of liquid and splashed the Journal and the oyster house, and, as Hallock noted, “by this one feat with waterpails and dippers, we have no doubt that at least a million dollars was saved from destruction.”

The blaze indiscriminately destroyed the grand Merchants’ Exchange, homes, churches, banks, and stores, the heat so intense it melted metal shutters, doors, roofs, and gutters. Disosway then reported how “a terrible explosion occurred nearby with the noise of a cannon. The earth shook. We ran for safety, not knowing what might follow.” Soon “a second explosion took place, then another and another.” The blasts were produced by bags of saltpeter stored in a warehouse. Liquor casks also exploded, as did barrels of gunpowder. On Manhattan’s docks, storehouses filled with barrels of sperm and other oils ignited. Along Manhattan’s shoreline, barrels of turpentine spilled from their containers, and the Evening Post reported that the contents “poured down into the slip like a stream of burning lava, and spread out over the surface of the river for several hundred yards, sending up a bright flame, and giving the appearance of the river being on fire.”

The fire that broke out on the evening of 16 December 1835 swept away 674 buildings in the commercial center of New York.

The fire that broke out on the evening of 16 December 1835 swept away 674 buildings in the commercial center of New York.(The Great Fire of 1835, from The New York Public Library)

At one in the morning, all the hoses used to put out the fire laid frozen. After the Dutch church steeple fell, Mayor Cornelius Lawrence, Gulick, James Hamilton—Alexander Hamilton’s son—and others decided that they needed to blow up buildings to create a fire break to staunch the flames. Hamilton, Lawrence, and Alderman Morgan Smith scoured stores for gunpowder. The Army Corps of Engineers sent cartridges and powder. But they didn’t have enough, so New York American editor Charles King set off for the Brooklyn Navy Yard to seek more powder. Army Lieutenant Robert Temple meanwhile headed to Governors Island. There he obtained kegs of powder and headed back with a number of men, landing on Manhattan after 3 AM.

Forty-Eight Exchange Place had been chosen as the building to blow up. It stood across the street from the remains of the Dutch church. Fire was falling through the hatchway as they carried a cask into the cellar. A piece of calico was attached to the container. A train of powder was then spread across the floor. Hamilton lit the fuse, and as former fire chief Uzziah Wenman recalled, “the whole building seemed to rise up and quiver.”

Unfortunately, the blast did not go exactly as planned, and they had to then blow up No. 52. By then King had made it ashore with the powder and the marines and sailors placed the barrel in the cellar. That explosion slowed the fire, and other buildings were soon also destroyed. In the early hours of 17 December, the seemingly relentless march of the fire that consumed 674 buildings, destroyed much of the city’s business district, and cost the equivalent of $600 million today, had been stopped. Hamilton returned to his family at the City Hotel on Broadway, and recalled, “My work was done. My cloak was stiff with frozen water. I was so worn down by the excitement that when I got to my parlor I fainted.”

Featured image: The Great Fire of the City of New York, 16 December 1835, from The New York Public Library

February 23, 2022

If God is not good, what is the origin of “good”?

Last week’s blog post was devoted to the origin of the word god and the proof that it is not related to good. There, I half-promised to write about the etymology of the adjective good, though I knew that there is very little to say, not because the word lacks interest but because I can only repeat what other people have written about it. Still, the notes that follow, though unoriginal, may be of some interest to our readers.

Good is a Common Germanic adjective and turns up more than once even in Gothic, the oldest recorded Germanic language. The Gothic text is a translation from Greek of parts of the New Testament. Goths ~ gods (modernized spelling) render in it Greek agathós, khrestós, and kalós, that is, “good, kind, able, beautiful.” It occurs as an attribute of a servant, a soldier, and a shepherd and carries rather obvious connotations of efficiency, rather than “goodness.” Also, the words for “heart” and “work” occur in Gothic with this adjective, and there, too, the same overtones are obvious. We use the adjective good freely: good man, good food, good house, and so forth, but in Old Germanic, this word had the connotations “worthy, noble” and was much more often applied to people than things. In the Old English heroic poem Beowulf, an early line praises a good (possibly, strong, kind, and generous) king. Elsewhere, gōd (ō designates a long vowel) also means “efficient, strong, brave.” In Old Norse, this adjective can be safely translated as “efficient, noble.”

Medieval Scandinavia is rich in rune stones. They contain memorial inscriptions, mostly to the relatives fallen in battle, and the word for “good” occurs there with great regularity. The dead son or brother is often called good, obviously, “courageous, valiant, brave.” With time, the Christian overtones “virtuous, pious” (as in a good Samaritan, Good Friday, the exclamation Goodness gracious, and the like) became more and more prominent, and nowadays, good is a colorless epithet of approval (compare good for you). As always in such cases, the best etymology of good should reckon with the oldest senses of this word, among which “efficient” is the most prominent. (A parenthetic remark. Pay attention to the irregular degrees of comparison: good—better. A similar case is bad—worse. It seems that good and bad were qualities that could not be “quantified,” like small—smaller, big—bigger, or old—older. This is an intriguing aside on so-called suppletive forms. See the post for 9 January 2013: “How come that the past of go is went?” Don’t missthe numerous comments following that old post.)

Why is bad ~ badly but good ~ well? One can spend a goodly part of one’s life thinking about the best answer.

Why is bad ~ badly but good ~ well? One can spend a goodly part of one’s life thinking about the best answer.In the etymology of good, the thorniest question is whether the Germanic word has anything to do with agathós. The Greek adjective has the same overtones as its Germanic counterpart. Homer’s usage is unmistakable. Agathós often occurs in his poems because, among other things, it fits the hexameter so well. And yet, the two words are, almost certainly, not related (I’ll skip references to the rich literature devoted to this question). The origin of agathós is unknown, and it is unclear whether, from the historical point of view, it is aga-thós “very fit for war, running fast” or a-gathós, with the obscure element a. According to an often-invoked rule, one word of unknown origin can provide no help in a search for the etymology of another opaque word. (Sorry for repeating this maxim with such regularity.)

The Germanic root of good was gōth-, but in the process of reconstructing an ancient root of Indo-European, Greek th does not correspond to Germanic th. Direct borrowing is out of the question. Other Greek words have been cited as possible cognates of good, but those hypotheses died without issue. With some regret, historical linguists began to look for a different etymology of good, and, it seems, discovered it. This is the etymology one can find, even if sometimes with a bit of hedging, in all modern dictionaries.

Goody Two Shoes: who could be better?

Goody Two Shoes: who could be better?(Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons)

Here are some words, presumably having the same root as good: Engl. gather (from Old Engl. gaderian) and (to)gether, Sanskrit gadh– “to cling to,” Latvian goùdas “honor, glory,” and especially the Slavic words with the root god-. Those words mean “fit, usable; to please, pleasing; profit; in advance; good weather” and in dialects, also “considerable; worthy, valuable; pleasant, pretty.” Equally instructive are Old Engl. (ge)gada and gæde-ling (both mean “companion, comrade”), with several cognates in Germanic denoting “friend; relative.” They always refer to being connected or fitting. Russian god means “year,” initially, as it seems, “a proper, good season for some work.” This semantic leap should not surprise us. In the remote past, people seldom needed a word for “a whole year,” perhaps mainly or only when they described a lamb or a calf as a yearling. Only later, some noun acquired the modern sense. The same is true of Engl. year. Its cognates outside Germanic usually mean “season; spring; summer.” Elsewhere, this root occurs in words meaning “to go, pass.” In Slavic studies, the root god– has also been compared with Greek agathós, but there, too, this comparison was eventually given up. Above, I wrote that the Germanic adjective could under no circumstances be borrowed form Greek. The solid Slavic connection makes the idea of borrowing from Greek into two branches of Indo-European even more improbable.

As a general rule, abstract meanings go back to concrete, more tangible ones. Before such a vague idea as that contained in the adjective good became universal, people seem to have asked themselves: “Good for what?” In our case, the answer is “good for being connected or fastened, for belonging together,” that is, “proper, fitting.” Today, as noted above, a man, a book, food, and anything, including weather and life, can be good or bad. Such was not the situation at the dawn of civilization.

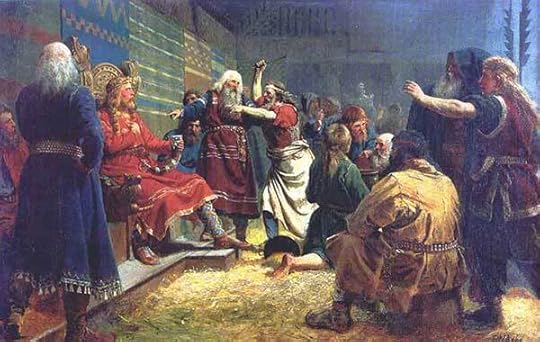

King Hakon the Good, c. 920-961, one of the greatest Norwegian kings of the Middle Ages.

King Hakon the Good, c. 920-961, one of the greatest Norwegian kings of the Middle Ages.(Håkon den Gode og bøndene ved blotet på Mære, by Peter-Nicolai Arbo via Wikimedia Commons)

Rather long ago, I wrote several posts about the word bad (17 June, 24 June, 8 July, and 15 July 2015). One can see that the opposite of good is, from an etymological point of view, an even harder word than good. This result makes sense: “good” is, at least to a certain extent, concrete, but “bad” is only “not good” and can evolve from any unpleasant fact or sensation.

Let me finish this dry post on a lighter note. The poet Vladimir Mayakovski (or Mayakovsky) wrote several poems for children. One of them is called “What Is Good and What Is Bad.” On the Internet, I found two translations of it into English but will quote my own version of the opening lines:

“Once a boy approached his dad,

And he asked his parent:

‘Something isn’t quite apparent:

What is good, and what is bad?’”

A long series of answers follows, but, predictably, none of them deals with etymology, so that I think I should stop here.

Featured image: Runestone U 240, Vallentuna by Berig via Wikimedia Commons.

February 22, 2022

The color line: race and education in the United States [podcast]

Black History Month celebrates the achievements of a globally marginalized community still fighting for equal representation and opportunity in all areas of life. This includes education.

In 1954, the United States’ Supreme Court ruled “separate but equal” unconstitutional for American public schools in “Brown v. Board of Education.” While this ruling has been celebrated as a pivotal victory for civil rights, it has not endured without challenge.

On today’s episode, we spoke with Zoë Burkholder, author of An African American Dilemma: A History of School Integration and Civil Rights in the North and Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900-1954, and Nina M. Yancy, author of the upcoming How the Color Line Bends: The Geography of White Prejudice in Modern America, examining issues around education, integration, and segregation through their scholarship. In particular, we discussed segregation in northern schools and a recent case study from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Check out Episode 69 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The Color Line: Race and Education in the United States – Episode 69 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingIn this episode, we discussed Nina M. Yancy’s How the Color Line Bends and Zoë Burkholder’s books An African American Dilemma and Color in the Classroom.

Zoë Burkholder is also the co-author of Integrations: The Struggle for Racial Equality and Civic Renewal in Public Education. Here you can find the introductions to An African American Dilemma and Integrations. Burkholder also wrote a blog post for the OUPblog entitled “Which is better: school integration or separate, Black-controlled schools?”

In 2019, Nina Yancy wrote an article in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics called “Racialized Preference in Context: The Geography of White Opposition to Welfare“, which reported some of her research for How the Color Line Bends.

You can also check out Takeover: Race, Education, and American Democracy, which offers a systematic study of state takeovers of local school districts.

Additionally, you can visit The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education for entries such as “Critical Race Theory and Qualitative Methodology in Education” and “Critical Whiteness Studies.”

Featured image: Photo by CDC on Unsplash.

February 21, 2022

Breathing life into statistics: stories of racism within the criminal justice system

You don’t need to look far to see how recent events have put the issue of racial inequality in the criminal justice system front and centre. The Black Lives Matter movement has brought the issue of institutional racism to the forefront of the public’s consciousness, kickstarting conversations and spurring communities into action to confront this inequality head on. This shift must be reflected in educational resources, and many textbooks in the field of criminology will be updated with statistics, news clippings, and quotes from prominent figures charged with reform in this area.

Yet the increased focus on and discussions surrounding racial inequality since the murder of George Floyd on 25 May 2020 have shown that it is human stories that have the greatest impact.

The Oxford Textbook on Criminology includes hard-hitting statistics, news extracts, and the latest scholarship, but it also goes further. Through the inclusion of numerous “Conversations” boxes, the book incorporates the voices and experiences of people we all need to hear from, breathing life into statistics and theoretical academic discussions.

This blog post takes extracts from just three conversations on the topics of racism and justice.

Gang members? Call us humans Omar Sharif, former gang member and now coach, mentor, and speaker, and winner of a Prince’s Trust Award.

Omar Sharif, former gang member and now coach, mentor, and speaker, and winner of a Prince’s Trust Award. “My first gang was my family. This gang met all my key needs so this should have been a space where I could feel safe and flourish. However, family support couldn’t make up for the fact that I felt failed by the system and excluded by society.

“I joined a ‘real’ gang at the age of 14 for my own safety and in order to feel more significant. Yes, it was partly to boost my fragile and immature masculine ego, but this only needed boosting because I felt excluded and purposeless.

“One memory that will always stay with me is when I was stopped and searched on Edgware Road, a stone’s throw away from my house. I offered no resistance but still the officers felt the need to put my face against the cold, wet slab of concrete, multiple knees pressing into my body. This was simply because I fitted the description of someone they were looking for, and it happened in front of my mum—I’d gone to help her carry her shopping.

“This is only one example, and I’ve experienced many similarly unjust events, but I have never forgotten the humiliation of it and the anger I felt towards those white police officers. The situation deepened my hate for the police force and anything that had to do with the law because yet again, I was the victim of police autocratic behaviour and received no apology. It was just a ‘routine check’, in the words of the officer.

“We must remember that everyone is a human. Gang members are just people looking for a sense of belonging in a society which constantly excludes them. If we strive for humanity then instead of creating division and amplifying a way of life that is particularly damaging for young people, we will be able to offer support and guidance to those who need it most.”

Extract from Conversations 9.1 with Omar Sharif, former gang member and now coach, mentor, and speaker, and winner of a Prince’s Trust Award.

The police force or the police service? Leon-Nathan Lynch, a barrister at 25 Bedford Row, London.

Leon-Nathan Lynch, a barrister at 25 Bedford Row, London. “I have been stopped and searched by police seven times. On the first occasion I was 14 years old, in my school uniform and walking home with a group of friends. The police stopped and searched me and my black friends for weapons whilst my white friends watched on.

“On another occasion I was on my way to work and was singled out on a busy train platform. I was told that I was being searched for drugs. Whilst I was being searched, the officers allowed their sniffer dog to place its paws all over my suit. Imagine having to explain to your work colleagues why you were late and why you were covered in paw prints . . . It appears that that neither the innocence of a school uniform nor the professionalism of a suit is enough to protect you from police racial profiling.

“Statistics continue to show the presence of racial profiling, which is problematic when the police are the main gateway into the criminal justice system. These kinds of policing practices explain to some degree the reason we see a disproportionate number of ethnic minorities within the Criminal Justice System.

“In my most recent encounter with the police they searched me at gunpoint [because] they said that they had reason to believe that I had a firearm in my possession. In my bag, instead of finding a firearm, they found law books.

“It appears that that neither the innocence of a school uniform nor the professionalism of a suit is enough to protect you from police racial profiling.”

“It felt like the officers had decided that I was a problem and were trying to create a narrative to fit. I’d done nothing wrong, I’d cooperated, and yet they tried their best to put me in a situation that could have devastated my career. Thankfully, they didn’t succeed and I’m a barrister now.”

Extract from Conversations 10.2 with Leon-Nathan Lynch, a barrister at 25 Bedford Row, London.

The CPS’ efforts to tackle institutional racism Grace Moronfolu MBE, Chair of the National Black Crown Prosecution Association (NBCPA).

Grace Moronfolu MBE, Chair of the National Black Crown Prosecution Association (NBCPA). “I joined the CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] as an administrative officer in 1988, soon after it came into existence in 1985. The 1990s was a challenging time for race relations in the UK. It felt like there was little social or criminal justice for Black African Caribbean or Asian communities.

“My personal experiences working for the CPS at that time were not particularly positive. During that period, I experienced a lot of negative behaviours from managers and colleagues, which I was unable to articulate as ‘racism’ at the time; it was just ‘the way things were’. As a Black woman and primary caregiver I was excluded in more ways than one.

“The Equality Act came into law in 2000, and in light of the new statutory obligations and the issues raised previously, the CPS invited Sylvia Denman QC OBE to investigate race equality in the service. Her report found that the CPS was institutionally racist and that this had wide ranging impacts on both the treatment of staff and the approach to criminal casework.

“To the CPS’s credit, senior leaders responded swiftly and in less than three years went beyond the recommendations of the report. For example, the Denman review brought to light the mistreatment of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic staff across the service. The senior team at the time said they weren’t aware this was happening so the report recommended that the CPS establish a network for these staff to give them direct access to key decision makers. In 2001, the National Black Crown Prosecution Association (NBCPA), the first CPS staff network, was born.

“In 2020, the NBCPA is now one of eight CPS staff networks—covering a broad span of interests including race, religion, disability, and most recently social mobility. . . we not only look to promote equality and diversity within the CPS but also more broadly in the criminal justice system. We act as a critical friend to the CPS. We work closely with the HR team to develop programmes and training events to support the progression and development of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic staff and to educate all CPS staff about the realities of structural racism and intersectionality in the UK today.”

Extract from Conversations 24.1 with Grace Moronfolu MBE, Chair of the National Black Crown Prosecution Association (NBCPA).

The voices featured in The Oxford Textbook on Criminology reveal many different perspectives on how race intersects with crime and the criminal justice system. However, there is a clear common thread: though it may now manifest in subtle ways, racial inequality continues to pervade society and the criminal justice system, from our streets to our courtrooms.

So how can we work towards a truly “just” justice system? Theory, statistics, and academic debates can help us understand the issues and develop potential solutions, but the events of summer 2020 showed that it is lived experiences that engage, mobilise, and ultimately spark change.

February 16, 2022

Religious terminology: the etymology of “god”

A few days ago, I received a letter from a well-educated reader, who asked me whether the English words god and good are related. Dictionaries, he added, deny the connection, but he preferred to think they are cognate. I answered him that the dictionaries are right and promised to answer his query in this blog. I might have added that no one should have an opinion about the origin of words, because their past should be investigated, not guessed.

To be sure, everything depends on what dictionary one uses. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, lexicographers did not doubt the god / good connection. But as early as 1828, Noah Webster, despite his penchant for fanciful etymologies, wrote: “…I believe no instance can be found of a name given to the Supreme Being from the attribute of goodness. It is probably an idea too remote from the rude conceptions of men in early ages.” He was quite right, even though the epithet rude cannot satisfy us today. Almost a hundred years later, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, an excellent multivolume reference work, repeated Webster’s conclusion almost verbatim. Perhaps I’ll devote another post to the adjective good, but first things first.

Both god and good are very old words, and the definitive origin of neither has been found. Both are etymologically obscure, and their similarity is due to chance. In Old English, the word god sounded as it does today, that is, god, with a short vowel. By contrast, the Old English for “good” was gōd, in which the vowel was long, approximately as in Modern Engl. Shaw (if you don’t pronounce it like Shah) or horse, but without r. Short and long o never alternated in the same root, and, to make the case quite hopeless, o in god goes back to a form with the vowel u. This is the easy part. Good god sounds fine, but not to a language historian or a student of religion.

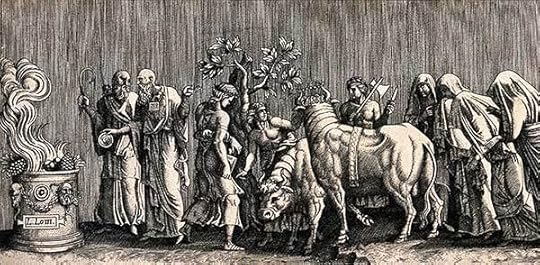

A pagan invocation.

A pagan invocation.(Engraving after L. Lombard, Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia Commons)

We have no way of knowing when the word god was coined, but assuming that it is native, it did not refer to a single deity, because before the Conversion, the ancestors of the Germanic-speaking people, like the Greeks and the Romans, believed in multiple gods. Pay attention to the evasive statement in the previous sentence (“assuming that it is native”). More than once, cautious scholars suggested that we are dealing with a borrowing, though they of course could not pinpoint the lender. When a word refuses to yield its etymology, the idea of borrowing occurs as a way out. Saying that a word is a loan from some lost language (substrate) is tantamount to admitting that we’ll never reconstruct its source. To be sure, god may have been adopted by Germanic speakers from the religious practices of some native tribe, but we’ll continue our story in the hope that the word does have an ascertainable origin.

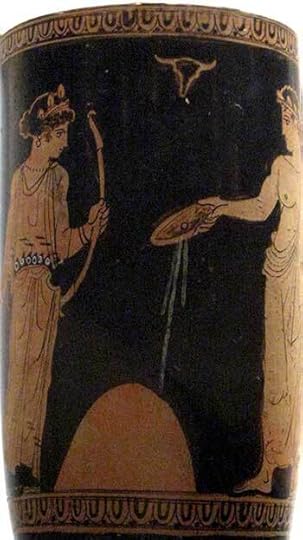

A religious libation.

A religious libation.(“Libation of Artemis and Apollo at omphalos” via Wikimedia Commons)

Monotheism came to Europe with Christianity. Moreover, whatever forces were believed to control people’s destiny, let me repeat: they appeared to humans as collective forces (gods, not God), and the words designating them tended to occur only in the plural. Three grammatical genders were distinguished: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Characteristically, the plurals just mentioned were often neuter plurals: no idea of male or female humanoids stood behind them. The same holds for the noun meaning “god.” Germanic mythology is lost, though some bits and pieces can still be picked up, and there is one shining exception. In Iceland, in the first half of the thirteenth century, two books, both now referred to as Edda, were written, and they remain our main sources of Germanic (or at least Scandinavian) pagan mythology. The word we need appears there in the neuter plural form goð (ð has the value of th in Engl. the). Later, in Iceland, the word was changed to guð, acquired the masculine gender (because of the reference to Jesus), and even changed its pronunciation.

For some time, etymologists looked on Persian khodá “deity” as a possible source of god, but it turned out that khodá appeared in Persian late, and the idea had to be abandoned. Later, two hypotheses began to compete. 1) Supposedly, there was some word like Germanic guthom, perhaps meaning “the being who is worshipped.” In Sanskrit, we find hu “to sacrifice” and huta “one to whom sacrifice is offered.” Sanskrit h– and Germanic g– go back to the same source, so that the phonetic correspondence is fine. God turned out to be a noun derived from a past participle with the sense “one invoked.” This is an old hypothesis. Both Walter W. Skeat, the author of the still most authoritative etymological dictionary of English, and James A. H. Murray, the great first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, knew it. As far as I can judge, today, this reconstruction has no supporters.

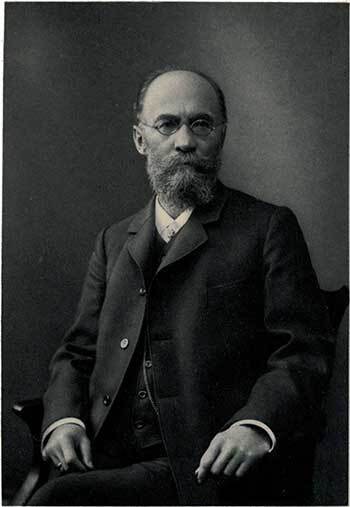

Karl Brugmann, 1849-1919

Karl Brugmann, 1849-1919(By Louis Pernitzsch via Wikimedia Commons)

The other old etymology, also known to Skeat and Murray, though modified half-a-century ago, starts with Sanskrit juhóti “he sacrifices; pours oil into fire” and its cognates in other languages. This reconstruction suggests that the idea of pouring was later transferred to the god, the receiver of the sacrifice. Thus, we are left with two choices: god means either “the one invoked” or “the one libated.” Though some specialists have cautiously endorsed the second etymology, no consensus on the subject exists, and indeed, one wonders how an ancient past participle, either “the invoked one” or “the libated one,” became an Old Germanic noun. I’ll skip a host of technical details that seemingly compromise the first reconstruction but will add that no one seems to be bothered by the fact that the singular form for the Old Germanic word designating “god” hardly existed: people, as noted above, did not believe in God, but in a multitude of higher forces we call gods. Such is the state of the art. As usual, it is easier to refute a suspicious or wrong etymology than to prove the worth of an allegedly reasonable one.

In 1889, two scholars (one of them being the great Karl Brugmann) suggested, independently of each other, that god is related to the Sanskrit word ghōrás “horrible.” This idea (now forgotten, though at one time, it was known to the best etymologists) seems to be more realistic than those mentioned above, but it shares the weaknesses of both: the cognate is remote, and it turned up in Sanskrit, with no supporting material in Greek, Latin, Celtic, Baltic, or Slavic. By the time of the conversion to Christianity, the speakers of Old Germanic knew the word guþ and used it for the name of the Supreme Being, but it remains a riddle why they chose it and what it meant before the conversion. It certainly did not possess the connotations of goodness, as evidenced by the related adjective giddy. This adjective turned up in Old English and meant “mad, possessed,” rather than “dizzy, with one’s head swimming.” Contact with gods was understood as a situation fraught with danger. Enthusiastic (an adjective containing the root of the Greek word for “god”) also carries the overtones recognizable in giddy: no invocation, no libations.

A modern idea of being giddy.

A modern idea of being giddy.(By Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash)

God may but need not be a borrowing from some unknown language. It may or may not have a cognate outside the Germanic group, but, if its truly convincing etymology happens to be discovered, the root will probably refer to fear of the forces beyond our control or their power over humans, or their being shining, omnipotent, and beyond reach.

Featured image: “The Council of the Gods” by Raphael via Wikimedia Commons

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers