Oxford University Press's Blog, page 85

February 16, 2022

Grove Music’s 2022 spoof article contest is now open!

I am pleased to announce the semi-annual Grove Music Online Spoof Article Contest is now open for 2022!

Spoof articles have had a long history within Grove Music. Grove’s particular style and format have long inspired parodies of all kinds. Last year, Lisa Colton won with a spoof on “Lip Synch,” and Andrew Gaydos was singled out for a spoof entry on “Bach-Bach Bach, Johann Egbert.”

This year’s winner will receive a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online and $100 in OUP books.

Submission Guidelines:Entries should be no longer than 300 words.Entries will be judged by Grove Music’s Editor in Chief Deane Root, Acquisitions Editor Scott Gleason, and a guest to be named later.Judges will consider the following criteria:Does the article adhere to Grove style?Is it entertaining?Could it pass for a genuine Grove article?Send submissions by email to GroveMusic.Editor@oup.com as follows.Subject should read “Grove Music fake article contest-[title]”.In the body of the email, include the title of the article and your full name and contact information (street address, email, phone).Include the entry in an attached document. Do not include your name. This is to facilitate blind judging.You may send as many as three articles, but please send each submission separately. No more than three entries will be accepted from a single author.All submissions must be received by 23:59 EST on 11 March 2022. Manuscripts received after that time will not be considered.

The winning article(s) will be announced on 1 April 2022 on the OUPblog.The winner will receive USD100 in OUP books, a year’s personal subscription to Grove Music Online, and bragging rights. There is no cash alternative, and the prize is not transferable.We reserve the right not to award a prize if we feel the submissions do not meet our criteria.Feature image: Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

February 15, 2022

François Truffaut: why we crave great fiction

François Truffaut is among the few French directors whose work can be labeled as “pure fiction.” He always professed that films should not become vehicles for social, political, religious, or philosophical messages. As Bunuel used to say: “My cinema is not meant to be understood. When you understand, you reach a meaning. If you reach a meaning, there is no use for images.” Martin Scorsese flatly declared: “If I could put it in words, I would not have to put it in films.” The specificity of images is to transpose something that goes beyond the linguistic and the cognitive. Truffaut called it emotion as opposed to ideas and he was supremely gifted at delivering this precious good in his work. What exactly is emotion? This innocent word covers a fearfully complex process.

Truffaut grew up in an atmosphere of secrets and lies. He was unwanted child and found out when he was 10 that his father was not Monsieur Truffaut, but another, unknown, man. Early on, he confronted a world where words could not be trusted and learned to rely on the accuracy of non-verbal signs. His fictions expertly reactivate the silent grasp of the external world associated with pre-linguistic perceptions and create a pregnant reality alive with telling gestures, lights, colors, motions, sounds, music. A brilliant film critic and script writer, Truffaut also worshipped the formidable power of language. His films abound with letters and literary texts and cultivate elegant dialogues. He devoted one of his most beautiful films to the duality of language, verbal and non-verbal. In The Wild Child, he confronts a scientist—played by himself—writing his diary and a little savage who will never master the use of words, but still displays a natural gift for deep connections.

Truffaut translated a rich perceptual world into hallucinatory landscapes. Under a deceptively realistic guise, images of his heroes chasing magical women in the streets of Paris become beautiful and universal metaphors for human destiny. His fictions give a geographic reality to emotions, memories, perceptions we cannot grasp or control. These metaphors suggest a hidden order organizing this buried material and bring it to light with exhilarating clarity. We are suddenly face to face with subterranean passions and we love what we see, instead of experiencing them amidst fear and confusion.

Truffaut often declared that human destiny is imprinted by what happens to a man between the ages of 8 and 12. To illustrate how his metaphoric constructions are charged with deep autobiographical overtones, I want briefly to compare two films dealing directly with these years in his life: The 400 Blows (1959) and The Last Metro (1980). More than 20 years separate these works. The 400 Blows is Truffaut’s first film and The Last Metro his antepenultimate one. He would only make two more films before his death in 1984. Besides covering the same time-period, they share another characteristic: both were his two biggest financial successes. They obviously delivered a powerful emotion to audiences. In every other respect, however, they completely differ.

First, style: realistic in The 400 Blows filmed in black and white and natural decors; elliptical and allusive in The Last Metro, which uses a studio-like set and a rich palette of colors where a deep red dominates. Second, narrative: The 400 Blows follows the social exclusion of a lonely 12-year-old boy who is successively expelled from school, home and Paris, and is ultimately locked up in a center for delinquents in Normandy. The Last Metro depicts the life of a theater during the German occupation, with a large cast of characters who closely interact in a series of subplots dealing with secrets, transgressive love, and creativity. A third difference sends us back to dates. Truffaut, born in 1932, was between 8 and 12 years old during WWII. He chose to film The 400 Blows in a 1959 setting, while The Last Metro is set in the Paris of the French Occupation. In The 400 Blows, we have the child, but not the décor; in The Last Metro, the décor but not the child.

Or so it seems. One feature common to both films is the presence of a formidable woman: in one, the child’s mother; in the other, Marion Steiner, played by Catherine Deneuve. Enigmatic, lonely, distant, somewhat scary but totally fascinating, both women harbor a secret: the former is hiding a lover; the latter a husband. The main dramatic twist in both narratives will be the unveiling of this secret by the hero: Antoine Doinel, will run into his mother and her lover in the streets; Bernard Granger (Gérard Depardieu) will discover Marion’s hidden Jewish husband in the cellar of the theater. From the beginning, Granger is associated with a young boy, the concierge’s son— who will be Deneuve’s illegitimate son in the play the theater is rehearsing. In The Last Metro, we also have a second major male figure: Deneuve’s husband, the creator in the cellar. In other words, in The Last Metro, Truffaut is present under three different personas: as a child, as a lover, as a celebrated creator.

Like Antoine Doinel, the creator is in jail, hiding and threatened because he is Jewish. Truffaut suspected that his unknown biological father was Jewish, and Catherine Deneuve was one of his great loves after their meeting on the set of The Mississippi Mermaid in 1969. Their break-up broke his spirit in 1971. “Love hurts” a line from The Last Metro, is a quote from The Mississippi Mermaid. The 400 Blows and The Last Metro form a diptych; they’re two complementary facets of Truffaut’s childhood. The 400 Blows evokes the loneliness of a rejected child, The Last Metro the healing art can dispense. The theater it depicts, with its red velvet seats, is a wonderful space, protected from the threats of the outside world (the Gestapo) and dominated by a radiant star figure in a splendid red dress (Marion Steiner). This is Truffaut’s everlasting image of the cinemas of his childhood.

Autobiographical material in The Last Metro is ubiquitous, albeit most cryptic—

so cryptic that it eluded even Truffaut’s directorial eye. I wrote my first essay on The Last Metro while Truffaut was still alive. He read my analysis and told me he was “staggered” by it. Knowing nothing about his illegitimate birth and his Jewish father, I was explaining that Bernard was in the position of a child who explores the maternal space and discovers the hidden father. Under the guise of a historical film, Truffaut had unknowingly projected, within a beautiful metaphor, the secret of his birth. This anecdote is meant to make an essential point: metaphors belong to the pre-linguistic perceptions; they escape the control of the cognitive mind. This is true for both the creator and the spectator.

Metaphor seems to be a key word to define Truffaut’s art. In each of his films, he seems to craft a new one almost more elegant, arresting, and poignant than the one before. The metaphoric constructions are embedded in formal elements that are peripheral to the main narrative. While analyzing The Last Metro, I decrypted the metaphor by focusing only on spaces, colors, and movements and ignoring the plot. Truffaut’s first film, The 400 Blows, is already profoundly metaphoric. Jean-Pierre Léaud was instructed not to express any explicit emotion while acting. The film’s form, in appearance naturalistic, furnishes secretly, through images, the key to the child’s inner rift. One example: the camera work sets up a contrast between the streets of Paris filmed in long mobile tracking shots and the inside scenes where fixed close ups dominate. The use of space captures a fantastic vitality frozen by the constraints of school and family life. Antoine’s long run at the end of the film brilliantly picks up both this spatial energy and its counterpoint in the last frozen shot by the sea.

Truffaut’s metaphoric constructions have a double function. While displaying a subterranean reality through formal arrangements, they generate a light hypnosis in the spectator. This perceptual mode differs radically from our normal ways of perceiving. It is not only different, it is accessible only through fiction and its metaphoric language. Emotion is hypnosis. Fiction opens a perceptual experience otherwise unreachable except, possibly, with alcohol and drugs, which however both lack the harmony inherent in art and, clearly, its safety. Mystical rapture would be another avenue, albeit much less within everyman’s reach than a film ticket. As the anthropologist Gregory Bateson writes: “What unaided consciousness (unaided by art, dreams and the like) can never appreciate is the systemic nature of the mind.” Art, in all its forms through the centuries, is not a luxury, but an adjuvant, an ancillary to our equilibrium and even survival, as Bateson suggests: “Unaided consciousness must always tend toward hate.” The systemic mind fosters empathy.

Great films also have moments when the hypnotic process breaks down because the images suddenly concentrate, in a fantastic coda, all the formal elements of the metaphor. This overload of effects wakes up the viewers and imprints the scene forever in their memory. It becomes what we call “an iconic scene”: Marilyn Monroe on the subway grate; Anita Ekberg in the fountain of Trevi, De Niro in the “You’re talking to me” scene of Taxi Driver and, of course, Antoine Doinel facing the viewer, his back to the sea, at the end of The 400 Blows. This last image is, by general consensus, one of the most memorable shots in the history of cinema.

At this point we may well ask two questions: Did Truffaut know he was putting this architecture in place? Do viewers realize it exists? As I suggested earlier, the answer to both questions is almost certainly no. Knowledge implies a conscious, deliberate cognitive operation, one that is lacking on the parts of both creator and spectator. Truffaut conceived his films as a trajectory in space, as rhythms and forces in movement. The logic of this vision instinctively guided his creation of the mise en scène; the viewer responds unknowingly to the call of these forms. They trigger the pleasure of the film, which becomes the locus of a passionate dialogue between two unconscious minds, one forcefully leading the other. Such is, in fact, the film’s raison d’être. When we go to the movies, this is what we crave. Basking in the dim light of great films, we rejoice in this pause in our daily routine—a pause as indispensable as it is blissful.

Feature image: from Nationaal Archief via Wikimedia Commons.

February 10, 2022

Chief Justice Roberts’ court questions the religious neutrality of secular schools

Having chosen “entanglement” as the best word to describe religious and secular cultures interacting, I noted with interest the oral arguments in Carson v. Makin, heard 8 December, 2021. This Supreme Court case involves public support for Maine schools and issues surrounding the First Amendment Establishment Clause. Justice Kagan uses “entanglement” first in a comment to counsel for the petitioners; later, addressing counsel for the state, Justice Gorsuch offers up “entanglement” as bait for argument. Is my favorite word taking on constitutional meaning, the sort that effects real change in society?

It turns out that the word’s constitutional use dates back half a century to Lemon v Kurtzman (1971), when Chief Justice Warren Burger injected “entanglement” into the Supreme Court’s critical vocabulary. The Court faced the question, “Do statutes that provide state funding for non-public, non-secular schools violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment?” Eight justices answered “Yes,” and Burger set out the following test for any proper statute: “The statute must not foster an excessive government entanglement with religion.”

Although subsequent Supreme Courts have interpreted the Establishment Clause less strictly, they have not overturned Lemon in principle. Hence it made sense for Kagan to invoke Burger’s terminology as she argued with Michael Bindas, counsel for parents who have contested funding decisions. “It would lead to too great entanglement,” she said of state support for religious schools. At this point in the argument, the entanglement in question referred only to entanglement of government with religion.

When the word returns in the second half of the session, however, it refers to a different entanglement of religion and secularity—something that will pose thornier questions. This new entanglement emerges with the Court’s comparison of religious and secular curricula. Gorsuch reintroduces the term as he questions counsel for Maine, Christopher Taub. “So a private entity can provide a public education in Maine?” “Yes.” “It just can’t have too much religious entanglement? . . . I believe that was your answer to the Chief Justice.” Taub swerves away from Gorsuch’s formula, and for good reason. Chief Justice Roberts had just finished leading Taub down a rabbit hole of hypothetical curricula. The resulting entanglement of religious and secular schools produced nothing like a satisfactory legal distinction.

Roberts had posited two schools. School A is nominally religious but has a secular curriculum. School B has a curriculum that is infused with religious belief through and through. School A would likely receive funding, they agree, and School B would not. Then Roberts alters School B to something half-secular, half-religious: “Some subjects are more susceptible to religious infusion than others. So half of the classes are religious. When they teach literature, it’s from a religious perspective. When they teach calculus or chemistry, it’s not. Do they get the full amount?” After Taub hedges but suggests they would not, Roberts sharpens the hypothetical School B to a curriculum with a single suspect class: “Let’s just say they take a religious perspective on history, just that. They have a particular view of the Crusades that not everybody might share.” Now Taub backs away from the challenge. “Your Honor, as I sit here today, I cannot answer that—that would be a much tougher situation.”

What’s so tough about Roberts’ hypothetical? It’s not the overt numbers game he seems to be playing, a tolerable fraction of non-secular curricular elements; Taub must know that’s a dead end. The tough thing is that Roberts has managed to tempt counsel into doubting his own foundational argument. All morning, Taub has relied on one (apparently) simple test: a school can receive funding only if it manifests religious neutrality. Secular schools are assumed to be religiously neutral. Enter School B. School B has only this one history class left that separates it from secular schools. No doubt Taub and every member of the Court who attended a secular school remembers a history class in which the Crusades were taught from an implicitly Christian perspective. What, then, was “religiously neutral” about this secular school’s history class? As secular and religious schools thereby entangle, Taub’s primary test at the very least needs fine tuning.

Justice Alito later offers his own challenge to the religious neutrality of secular schools—he asks about a school that might “inculcate a purely materialistic view of life”—but it is Roberts’ history class that makes the subtler, better point. Here’s the underlying complication: teaching history as a secular subject involves interpreting events through filters of values and assumptions that cannot neatly be separated from those associated with religious communities. The same goes for other core humanities subjects, English and philosophy, with their interpretive projects. Counsel Bindas seems to have picked up on this complication for his closing rebuttal. “In a philosophy class, apparently, you can teach Aquinas and Augustine,” he begins. “But if you say Augustine and Aquinas were right, then apparently, you’re out. . . . That is discrimination.”

No: that is poor teaching. A good teacher would never just say any philosopher worth reading was right or wrong. A Supreme Court operates differently, of course, and it seems likely at least five of these justices will say Mr Bindas is right.

Featured image by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

February 9, 2022

The incomprehensible word “understand”

For three weeks, we have been examining scholars’ attempts to explain why we say see and hear (the post for 2 February 2022, and the two preceding ones). I would like to finish this miniseries with an essay on understand. See and hear are short and opaque verbs (from an etymological point of view). Understand is a teaser: each of the two elements of this compound is clear, but why does it mean what it does? Understand refers to a highly abstract concept, and, apparently, something concrete and even obvious must be at the bottom of it, but still why stand under?

Perhaps the most transparent verb synonymous with understand is comprehend, borrowed from Old French or directly from Latin. It contains the prefix com “together” and a root meaning “to seize” (Latin prehendere). Dutch begrijpen and German begreifen have a similar inner form; compare Engl. grip, gripe, and (!) grippe “flu.” Russian poniat’ is opaque to modern speakers, but from a historical point of view it also means the same, and indeed, “to understand” is “to get hold of a meaning, to be able to size up the situation, to come to grips with it.” The Latin verb intelligere goes back to inter “between” + legere “choose, pick up” (compare Engl. “I gather you did not like the book I sent you”). In Germanic, the analogs of understand are ubiquitous. German has verstehen (that is, stehen “to stand” with a different prefix), corresponding to Dutch verstaan, Frisian ferstean, and Old Engl. forstandan (!) competing with understandan. It follows that the verb “stand” could be combined with more than one prefix and yield the same meaning.

Here are a few more examples reinforcing this impression. German unterstehen means “to be subordinate, etc.” and has nothing to do with understanding. Or consider Engl. undergo, alongside German untergehen “to go under.” Earlier, undergo did mean “to pass under.” It has often been said that under in such contexts means “between, among” rather than “under,” but neither combination with stand yields the sense “understand,” even though indeed, when one “stands under,” one may get to the bottom of things, and standing between or among things results in acquiring the power of discrimination. Understand, it seems, must originally have referred to the process of observation and learning rather than the result.

Coming to grips.

Coming to grips.(By Irish Tug of War via Wikimedia Commons)

It is of course the prefix under, rather than the root stand, that puzzles us. Heroic attempts have also been made to interpret ver– in German verstehen. For example, Latin prae-stāre meant “guarantee, vouch for,” but its Old High German equivalent fir-stān never had the meaning “to present a case in court” or carried any other legal overtones. Anyway, Engl. understand begins with a different prefix. To increase the idea that at one time, speakers experimented with several nearly or fully interchangeable formations conveying the idea of understanding (or even indulged in learned wordplay?), we note that in Old English, understandan had several synonyms, while the modern verb understand has no competitors in the native vocabulary.

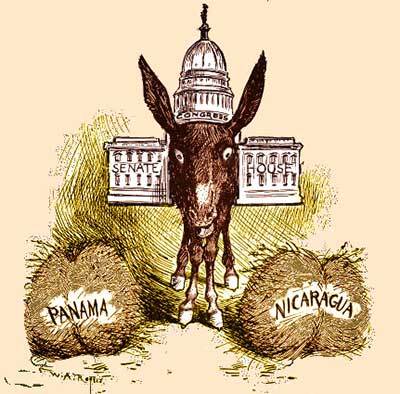

Buridan’s ass: a most discriminating creature.

Buridan’s ass: a most discriminating creature.(By William Allen Rogers – New York Herald, via Wikimedia Commons)

Above, mention has been made of the Latin verb prehendere (here, the root is given in bold). In –hend-, the sound n is an “infix,” an insertion, so that the genuine root is hed (this is by far not a unique case: compare Engl. stand and its past tense stood). The Germanic cognate of hed is Engl. get, from Old Engl. gietan (only the pronunciation of g- goes back to Scandinavian) and, surprisingly, we find Old Engl. under-gietan “to understand.” All in all, Old English had at least five verbs beginning with under-, followed by different roots, all of which meant “to understand.” The various shades of meaning attached to those words are hard to reconstruct, and there is no certainty that our reconstruction, produced from a limited number of examples, reflects the true picture of past usage.

We also watch with amazement how fluid the meaning of Old Engl. far-standan, an analog of German verstehen, was: “to defend, resist, withstand; to benefit; to understand, be equal.” One even wonders whether we have a single word or a group of homonyms derived from several sources. Verbs with the same root and different prefixes and verbs with the same prefix and different roots often meant different things (which is not surprising), but the results are often unpredictable. Compare Modern Engl. overlook and oversee: if we did not know what each of them referred to, we would not be able to guess or explain their meanings. German übersehen means both “oversee” and “overlook”!

One gets the impression that speakers of Old English and perhaps of the other West Germanic languages (German, Dutch, Frisian) were in the process of coining one or more words for rendering Latin intelligere. They played with several roots and several prefixes. The wealth of synonyms is amazing. Such a situation may not be too rare, but usually the differences between the synonyms is obvious. For instance, comprehend, unlike understand, is bookish. Or one may say: “I am unable to fathom this mystery,” but fathom carries special overtones (one fathoms depths). The same holds for grasp. The contexts in Old English texts suggests that some synonyms carried more abstract connotations than the others, but one cannot be sure. That is why the most learned attempts to reconstruct the meaning of under– and for– in such verbs carry little conviction. The literature on the etymology of understand and its synonyms in and outside English is huge; yet no truly persuasive conclusion has been reached. One can only see that all such verbs developed from spatial metaphors, whose idea was that standing in a certain position allows the observer to get to know the properties of the object. This conclusion is rather trivial, but the details evade us.

An overseer: he does not overlook anything.

An overseer: he does not overlook anything.(By dalbera from Paris, France – Musée égyptien (Turin), via Wikimedia Commons)

The situation described above is especially puzzling in light of the fact that elsewhere in Old Germanic, speakers had no problems with the verbs of understanding. In fourth-century Gothic (a fourth-century East Germanic language), we find the verb frathian (the spelling has been modernized), derived from an adjective meaning “clever, wise,” while the Old Icelandic for “understand” was skilja, that is, “to divide; to separate.” In Modern English, the art of “separating” things, the ability to differentiate and distinguish is called skill, an English word borrowed from Scandinavian. Yet neither Gothic nor Scandinavian had any influence on the way the speakers of West Germanic referred to the process of understanding, and to this day we keep wondering where we stand in relation to the odd verbs understand, verstehen, and their likes. I cannot help believing that in West Germanic, too, some simple, transparent verb existed but was ousted by learned coinages, influenced by medieval Latinity and multifarious attempts to find a proper equivalent of intelligere—an example of relatively unintelligent guessing.

Featured image by Sebastian Bill on Unsplash

February 8, 2022

Which anti-vaxxers are irrational?

Consider two different characters: Alanna and Brent. Both Alanna and Brent refuse to get the COVID-19 vaccine, but their motivations are different. Alanna believes that the vaccine is extremely unsafe and ineffective. Brent, on the other hand, believes that the vaccine is safe and effective. However, he is young and healthy, and he isn’t that worried about the effects that contracting COVID-19 would have on him. Some people have pointed out to Brent that even so, his getting vaccinated would help to protect others that he comes into contact with, some of whom are immunocompromised and so more vulnerable to the virus. However, Brent simply doesn’t care much about protecting others, and so he can’t be bothered to get vaccinated.

Are these characters irrational? Many philosophers and social scientists, and perhaps many ordinary people too, would give different answers for Alanna and Brent. Alanna, they would say, is irrational. Let’s suppose, for the sake of argument, that Alanna has plenty of evidence that the vaccine is safe and effective: she’s seen the data that shows that the vaccinated are far less likely to die from COVID-19 than the unvaccinated, and that serious side effects of vaccination are extremely rare. If she continues to believe that the vaccine is extremely unsafe and ineffective, then, she has a belief that flies in the face of her evidence, and this seems like a paradigm case of irrationality. Brent, on the other hand, may be cruel and uncaring, but this—many would say—isn’t a matter of irrationality.

Drawing on some arguments in my book, Fitting Things Together: Coherence and the Demands of Structural Rationality, I will suggest that this differential verdict—that Alanna is irrational but Brent is not—is not ultimately defensible. In the book, I distinguish two different kinds of rationality: substantive rationality, and structural rationality. Substantive rationality is about being reasonable, or responding correctly to your reasons. When we say that it’s irrational to believe in fairies, for example, we’re usually using “irrational” in its substantive sense. You have no good evidence for the existence of fairies, and so you have no good reason to believe in them; such a belief is unreasonable. By contrast, structural rationality is about being coherent—or having beliefs, intentions, and other attitudes that do not clash with each other in bizarre ways. Suppose someone believes that all Trump supporters are morally bad people, yet knows that their plumber is a Trump supporter, and admits, when pressed, that their plumber is not a morally bad person. Such a person is structurally irrational: they have a set of beliefs that are jointly incoherent, or don’t fit together right.

With this distinction in view, let’s return to Alanna and Brent. Alanna is substantively irrational, since she does not have good reasons for her belief that the vaccine is extremely unsafe and ineffective. However, she might nevertheless be structurally rational: that is, her beliefs and other mental states might be totally coherent. For example, she might also hold some complex conspiracy theory that claims that all the data regarding the vaccine’s safety and efficacy has been faked. Again, we can suppose that she has no good reasons for holding this conspiracy theory. Yet, if she holds it, her beliefs may be completely internally consistent and coherent. In summary, she is substantively, but not structurally, irrational.

What about Brent? Brent prefers avoiding the inconvenience of getting the vaccine to protecting the immunocompromised people that he comes into contact with. Like Alanna, there certainly needn’t be anything incoherent, or structurally irrational, about Brent. He may quite generally always put his own convenience over others’ wellbeing and hold a worldview according to which there’s nothing wrong with doing this. However, in order to determine whether Brent is substantively rational, we need to ask whether his preference for his own convenience over the wellbeing of the immunocompromised is actually reasonable or supported by good reasons. And I suggest that it is not: his own convenience is simply not as important as the wellbeing of the immunocompromised, and it is not reasonable to prefer the former over the latter. If this is so, Brent is substantively irrational. And so, Alanna and Brent are on a par: they are both structurally rational, but substantively irrational.

The view that says that Alanna is irrational but Brent is not effectively treats the rationality of belief differently from the rationality of preference. When it comes to belief, it assumes that you actually need good reasons for your belief in order to be rational: mere coherence isn’t enough. But when it comes to preferences, it assumes that as long as your preferences are coherent, they are rational: they don’t need to be based on actually good reasons. But it is hard to see what justifies this differential treatment of the rationality of belief and the rationality of preference.

You might suggest that the answer is that there are no objective facts about which preferences are reasonable and which are not. After all, Brent would say that his preference is reasonable, and it seems hard to conclusively prove, from premises that Brent would accept, that he’s wrong about this. If this is right, perhaps it explains why Brent’s preference can’t be irrational, even substantively speaking. But if you think that, why not say the same about beliefs? After all, the claim that Alanna’s evidence really supports believing that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe and effective—rather than her wild conspiracy theory according to which all the data was faked and the vaccine is highly unsafe and ineffective—is also one that she contests, and it is surprisingly hard to conclusively prove, from premises that Alanna would accept, that her take on the evidence is an unreasonable one. So, if this line of response saves Brent from irrationality, it threatens to save Alanna from irrationality too. Whatever we say, then, it seems that there is no relevant difference between Alanna and Brent when it comes to rationality.

February 6, 2022

What are light verbs?

English verbs show tremendous variety. Some have a lot of semantic content and serve as the main predicate of a sentence—as transitive or intransitive or linking verbs. Others are auxiliary (a.k.a. “helping”) verbs, which indicate the tense, aspect, modality, or voice of the predicate.

Then there are light verbs.

That term was coined by the famous Danish linguist Otto Jespersen in his Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. It refers to verbs which get their main semantic content from the noun that follows rather than the verb itself. Hence, the verb is “light.” The noun that follows typically describes an action, and light verbs include take (take a walk, take a nap), give (give a talk, give a call, give a demonstration), have (have a cry, have a look, have a drink), make (make a claim, make a fuss) and do (do battle, do business, do the wash).

Many light verb phrases have a corresponding expression with a verb that actually expresses the action: walk, nap, talk, demonstrate, look, drink, claim, wash. There can be small differences too: to give a talk is not the same thing as to talk and to do the wash is not the same thing as to wash.

The set of verbs that can be lightened is broader than you might think. You can create a ruckus, hold an opinion, harbor a resentment, effect a change, and more. And the set of nouns that can contribute their semantic heft is wide as well. You can have a drink, but also have a beer, have coffee, have breakfast, a snack, a bite to eat, and so on. Often, such light verb constructions with have lack full verb expressions (when was the last time you used breakfast as a verb?).

Some light verbs, especially those with give, employ a second noun to create an interrupted compound verb like give the sheets an airing, give the counter a wipe. In the first, give ____ an airing is the light verb, and the sheets can be replaced by sundry things than might need an airing (a blanket, a room, a car). In the second, the light verb is give ____ a wipe, andthe noun counter can be replacedby things to be wiped (the floor, a tabletop, the baby).

And some light verbs seem lighter than others in that they resist the passive voice. It seems odd to say a nap was taken or a walk was taken, but it is less odd to say a resentment was harbored or an opinion was held.

Why does English have light verbs? Part of the answer is the inevitable bleaching of meaning of words—the same process by which awesome and terrific come to simply mean good. The likely evolution is that verbs like take, have, give, and make lost some of their meaning and acquired new meaning as the complex predicates take a nap, take a walk, and so on.

The light verb construction adds flexibility to English: it allows us to have and take all manner of things without requiring specific verbs for them. We do not need a dedicated word for creating a ruckus or doing homework. And we can distinguish ineffable matters of nuance: the difference between having coffee and drinking coffee, for example, or between napping and taking a nap.

With that, we’ll take a break.

Feature image by Johannes Andersson on Unsplash

February 2, 2022

“A man of genius makes no mistakes”: Joycean misapprehensions

Joyce invites misapprehension in many ways. He overtly signals the importance of error with Stephen’s famous line in “Scylla and Charybdis”: “A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery”. This is a particularly shrewd move on Joyce’s part. Since a man of genius makes no mistakes, anything that seems like a mistake must actually be something ingenious that can only be discerned by a suitably astute reader. In effect, Joyce implies that there are no mistakes in this text, just artistic brilliance that may or may not be properly apprehended.

This, of course, can drive readers crazy, or at least, a little paranoid. This is further compounded by the many misapprehensions have circulated around Joyce. The famous line about errors being volitional and the portals of discovery has itself been misapprehended and misquoted. On Wikiquote, it was formerly rendered as “Mistakes are the portals of discovery”. This mistake has since been corrected, but the misquotation endures and can be found in many places and has even succumbed to further misquotation. On the façade of a pub in central Dublin it has now become the curious “A man’s errors are his portals of discovery”.

Joyce was even misquoted on the commemorative €10 coin Ireland issued in 2013. They picked the first few lines from “Proteus”, one of the more famously difficult passages in Ulysses: “Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot’. The coin has instead, “Signatures of all things that I am here to read”. Of course, there is some humour here in the fact that in this passage Stephen is thinking about the problems of apprehension, specifically visual apprehension: what it is to see and to understand what one sees, the signatures of all things to be readand that are to be misread and, eventually, misattributed on a commemorative coin.

The Central Bank admitted that the whole thing was a mistake, but initially they tried to pull their blunder through a “portal of discovery” and claim it was a deliberate aesthetic choice. In their first press release on the matter they said, “it should be noted that the coin is an artistic representation of the author and text and not intended as a literal representation.”

This was of course mildly embarrassing for the Central Bank, but these kinds of typos have infected the Joycean corpus for years. The first edition of Ulysses is famously riddled with errors because it was printed in France, by a French printer who did not understand English. In 1921 when he was going through the page proofs for Ulysses and seeing all the mistakes that were being made, Joyce groused, “I am extremely irritated by all those printer’s errors. … Are these to be perpetuated in future editions? I hope not.” But, the following year, after the first edition was published, Joyce and Harriet Weaver and John Rodker began compiling a list of corrections to make for the second printing. Joyce wound up vetoing many of the emendations suggested by Weaver and Rodker since, as he explained to Weaver, “These are not misprints but beauties of my style hitherto undreamt of”.

Sometimes, editorial mangling winds up creating something evocative, such as the word “enchanced” instead of the more conventional “enhanced”—an “enchanced” emendation that originally appeared in the 1936 Bodley Head edition and which survived through several more printings. This particular misprint is all the more intriguing since it seems like a Joycean effect even though it was the result of some typesetter’s error: a word enhanced by a chance mistake.

To claim that something is wrong, you have to know what is right, or, improving ourselves, you have to thinkyou know what is right. There are several ranges of response to error, for example, one can be a pedant and criticise. This is the scholarly response, something academics are paid to do. There is obviously a place for such nit-picking. But it’s not necessarily an end in itself. In a human world, there has to be a place for human quirks and foibles and blunders. Indeed, life itself can be considered a mistake, or rather, the result of a lot of mistakes. Biological evolution—the slow accumulation of alterations in the genetic code—could be characterised as an erroneous transmission of information across generations and across domains, kingdoms, phyla, and so on. If there hadn’t been erroneous—that is, imperfect—transmission of genetic data, then human life would never have evolved. It’s not just that error makes us human, but rather, error made humans. And so, this leads to another type of response to error: acknowledgement and acceptance. This is perhaps the lesson of Ulysses, the affirmation of the messier parts of life, even typos. Ulysses, like life, is“enchanced.” Misapprehension is fundamental to being a Joycean and fundamental to being human.

Feature image: Portrait of James Joyce (1882-1941), Author, Jacques-Emile Blanche from the National Gallery of Ireland used under Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Monthly gleanings for January 2022

See was the subject of the most recent post (26 January 2022). In this blog, I usually try to do without exact references, and last time, I also mentioned an authoritative recent book but gave no names. In my database, 74 references to see can be found, that is, to 74 articles in which the origin of see is discussed. No doubt, I have not licked the plate clean. But our readers may be curious to know that even the most recent hypotheses are old and that the conjectures current today were not only discussed but often refuted or at least called into question long ago. Etymologists tend to revive old conjectures because it is extremely difficult to cull all of them. Take the most popular one, according to which see has developed from a verb meaning “to follow.” It has been around for a hundred years. Also, the derivation of say and see from the same root looks like a daring recent hypothesis. Yet nothing can be further from the truth.

As early as in 1892, it was pointed out that the Gothic noun siuns, derived from the root of the verb saihwan “to see,” meant only “face” and “vision.” If “follow” had been the root’s nuclear meaning, the noun would probably have meant “following; sequence” or something similar. And around the same time, it was said that the development from “follow” to “see” is hard to imagine. Eighty years later, similar doubts about the derivation of “see” from “follow” were repeated, and an additional consideration was cited, namely, that in no recorded language, including Hittite, does a cognate of see mean “follow.” This may not be a crushing blow to the favored etymology, but it should be taken seriously. I’ll skip some other arguments: they are too technical to be discussed here. The string “to be seen”—“to show, indicate”—“to say” was also reconstructed more than a century ago. Indeed, Latin dicere means “to say,” while indicere means “to show, indicate.” The semantic reconstruction of this type does without the intermediate link “to cut,” discussed not unfavorably last week. Where then is the truth?

Echo and Narcissus

Echo and Narcissus(By John William Waterhouse, via Wikimedia Commons)

This excursus is meant to illustrate how shaky almost any etymology is and how cautiously one has to take dogmatic statements even in good etymological dictionaries. One needs a complete picture, with multiple references, in order to get an informed opinion about the statements given there. They are not wrong, because no one knows the truth: they are lopsided. It does seem that see has nothing to do with following or hunting, among other things because to see is to keep something in sight, rather than follow a moving target (this consideration is also old!). It remains somewhat unclear to what extent see and say are related, and we are unlikely to reach a fully persuasive conclusion. Lithuanian sakýti “to say,” as opposed to sèkti “to follow the track” (mentioned in the previous post), both seemingly related to the Germanic verb, will haunt us as long as we remain on this perilous track. An enlightened reader needs a full discussion of all the existing conjectures, which means that every etymology, the references included, should be many pages long—apparently, a utopian project. A lay reader will be satisfied with a short summary of the state of the art and can dispense with a long list of cognates if it leads nowhere. Only apodictic statements should be avoided, because in too many cases the etymologist is doomed to offer a mildly intelligent guess, rather than a solution.

Echo Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga(By Darelle via Pixabay)

This word came up in connection with the origin of the verb hear, from Germanic hausjan. The Greek word had no initial aspiration. In mythology, Echo was a nymph, vainly pursued by Pan, who sent mad shepherds to tear her to pieces, but earth hid the fragments, which imitate other sounds. Another version connects Echo with Hera, who detested Echo, an incorrigible chatterbox, and allowed her only to repeat what other people said. More tales of the same nature have been recorded. Especially famous is the tale of Echo (she could hear only herself) and Narcissus (he could enjoy only his own image: the version is suspiciously too symmetrical to be genuine). The word echo resembles interjections (akh!, okh!, ekh!). Do all our readers remember that in nineteenth-century grammar books and even later, interjection was called ejaculation? Those innocent grammarians! Echo is probably a sound-imitating word, like the echo itself. Not even by the wildest stretch of imagination can one connect echo and Germanic hausjan.

More mythology: Baba YagaBaba Yaga (stress on the last syllable!) is a character in Slavic folklore. Her roles are many. Perhaps the most ancient one is that she guards the checkpoint between the world of the living and the world of the dead and will or will not allow the hero to cross the border. She lives in a revolving hut on chicken legs, and her nose is stuck in the ceiling. But in many tales, she steals small children and tries to thwart the heroine who comes to her sibling’s rescue. She flies on a broomstick and sweeps her tracks with the help of that implement. Baba means “woman” or “old woman” and has finished its career oversees in the perfectly innocuous sweet babka (at least so in the US) and babushka “kerchief” (also stressed on a wrong syllable!). The question was about the etymology of Yaga. The conjectures are rather many. In some Slavic languages, the cognates of Yaga mean “superstitious fear; awe; torture,” and outside Slavic, the proposed related forms mean more or less the same. Perhaps the name always meant “Lady Fright.”

These are babushka: the image is right, the stress on the second syllable is not.

These are babushka: the image is right, the stress on the second syllable is not.(By Лариса Горбунова via Wikimedia Commons)Masher

On 12 January 2011, I published a post on the word masher. Quite recently, Mr Michael Hocken discovered that post and sent me a series of photos by Samuel Hey of so-called black mashers. The main point, he says, is to confirm that the term black mashers does appear to have been in the late 1880s—and in the UK—to describe the performance more generally known as black minstrels. They appear in “blackface” in one of the images. It would be most interesting to hear from our readers what they know about those minstrels. Please post you answers in the “comments,” rather than in emails addressed to me.

Odds and endsMaga ~ MacA correspondent asked me why Tamil maga “young man” sounds so much like Celtic Mac “son.” Knowing nothing about Tamil and very little about Proto-Celtic, I can only risk saying that this is a coincidence. Yet the consonant m often occurs in words for “we” and “one’s own.” The lips are pressed together, and this image provides a feeling of belonging. I have read some works explaining the otherwise incomprehensible change of wir “we” to mir in some German dialects and Yiddish. Russian for “we” also begins with m. But of course, this is not an answer to the question I received. More informed replies are welcome!

Mussorgsky – Pictures at an Exhibition – XIV. The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba-Yagá)Hebrew shekel ~ Indian siklaThose are related. This monetary unit was known widely: Hebrew sheqel, Syrian shāqual, Persian síglos, Greek síglos ~ síklos, Late Latin siklus. Engl. lop-sided. Lop is usually referred to lob (the variation p ~ b in such monosyllables is not uncommon, and at one time loppe and lobbe alternated as the name for the spider. The verb lob, of Low German or Dutch provenance, meant “to drop.” Lop-eared has a similar origin.

German hören “to hear” and aufhören “to stop”I wrote that aufhören is a puzzle: Why should a combination of the adverb (or preposition) auf “on” and hören “hear” yield “stop?” In the comment, it was pointed out that aufhorchen also means “to listen attentively,” allegedly, “to stop, in order to listen.” But horchen without auf means the same! If the emphatic or frequentative suffix ch (from k) suggests “to listen with great attention” (and hence “to stop”), what follows with regard to aufhören without this suffix?

On staying in bedYes, indeed, German Gardinenpredigt is an excellent equivalent of Engl. curtain lecture, but the German phrase seems to have originated later than the English one. Could it be a translation loan from English? And yes, when a bed is beaten, a cloud of dust may rise, but bedposts don’t twinkle (apropos the post about the twinkling of a bedpost).

IdiomsThose interested in the history of a white elephant may consult the website White Elephant party Origin Mental Floss. (I may add that the idiom is discussed in numerous websites.)

I’ll leave without comment a few interesting observations because I have nothing to add. The Hittites, as I learned from a very knowledgeable reader, seem to have believed that stars imbue water with magical properties and left vessels on the roofs. Likewise, I absorb comments and am very grateful for them, even when I resist their magic.

Featured image by Zeledi via Wikimedia Commons

January 29, 2022

Silver linings from the COVID-19 shutdowns at music schools

“Our teachers and students and families are so excited to be back, to see everyone again,” said Brandon Tesh, director of the Third Street Music School in New York City. His school resumed in-person classes in September 2021 after 18 months of online instruction, caused by government-ordered school shutdowns aimed at slowing the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Other music schools and music programs also resumed in-person instruction last fall, but in early January 2022, his school and others had to switch back to online learning for a while because of an upsurge in COVID infections in their cities. His school was back in-person by mid-January, although with enhanced COVID testing options and additional safety measures in place.

“We are rolling with the punches, making music and keeping our students active,” said Rebecca Henry, string department co-chair at Peabody Preparatory, which also reverted to virtual learning in January. “We had to cancel our big January Performance Academy Festival Orchestra and are trying to re-schedule to February.” Nick Skinner reports that his OrchKids program, which provides free music instruction for more than 1,900 students in Baltimore’s public schools, “has developed virtual and modified in-person plans for all our sites so we can be flexible week to week based on COVID testing at each school,” shifting back to virtual whenever needed.

These educators and their students have become experts at pivoting quickly, a skill they had to master as the pandemic started in March 2020, when they suddenly had to learn to use Zoom and other video-conferencing programs along with apps for recording music so students could continue to interact with their teachers and create virtual performances.

After in-person instruction resumed at many schools last September—albeit with mask and social-distancing precautions making the learning experience far different than pre-pandemic—one might imagine that students and teachers would have gladly waved goodbye to the online tools they used during the shutdown. But many educators kept using some virtual tools last fall, as part of their in-person toolkit because they felt those techniques enhanced the learning experience, providing surprising silver linings to the shutdown ordeal.

“One of the best silver linings is Zoom. It changed everything we do,” said Nick Skinner, Senior Director of OrchKids. He and others have found that Zoom is a great tool for holding faculty meetings, professional development workshops, and get-togethers with parents, eliminating travel time for everyone as people simply connect with each other from home.

Because of video conferencing, “we were able to start planning collectively,” said Jessica Zweig, Program Director for Play on Philly, a free after-school program for more than 300 students who meet at five different centers in Philadelphia. Before, it had always been hard to bring all the teachers together from the program’s different sites for meetings, but now Zweig reports that teachers “are getting together in virtual meetings every two weeks to find ways of creating consistency and continuity among our teaching strategies.”

The shutdown also had an impact on the OrchKids curriculum. For the first time they offered a weekly private online lesson to all students who were able to connect with them virtually. That was totally different than the teaching strategy they had been using—the El Sistema group-playing approach. “We saw that there’s nothing that can compare with the mentorship of one-on-one instruction,” said Skinner. “We’ll still do group lessons for younger students who are just starting. But we’re thinking of bringing private lessons more into the program as students progress.”

“We will use Zoom lessons for snow days and make-up lessons,” said Rebecca Henry, string department co-chair at Peabody Preparatory. “We will include some online repertoire classes for students who cannot always be at our in-person events.” Peabody and others are allowing some students who aren’t comfortable returning to in-person instruction to have virtual lessons instead.

In April 2021 orchestra students at Third Street Music School in New York City took over the street in front of the school for their first, in-person performance after a year of remote learning.

In April 2021 orchestra students at Third Street Music School in New York City took over the street in front of the school for their first, in-person performance after a year of remote learning.(Photo credit: Courtesy Third Street Music School, Mark Torres Photography.)

Another silver lining that was popular with the educators we spoke with was the chance to bring in professional musicians during the shutdown to meet with students in virtual master classes and workshops “at a fraction of the expense,” said Skinner. There’s no need to cover airfare and hotel costs with virtual gatherings. He and the others plan to continue these virtual visits. “We’ve upped some of our equipment and our technical know-how,” noted Tesh, “so that digital master classes can be really good quality. We will also be live-streaming more of our performances because we’re limiting capacity at our in-person performances,” a process that started last spring with this video of an in-person performance that took place when New York City began allowing outdoor concerts on certain streets.

Zweig’s program commissioned composers to create new pieces for Play on Philly students. Iranian-Canadian composer Dr. Iman Habibi wrote a piece that “the kids learned virtually by themselves. We did individual recordings and put it together. He was able to give them feedback from Canada.” Now Play on Philly is commissioning composers to write new pieces that are appropriate for beginners but that are “written by people who are reflective of the kids who are playing them.”

Online group performance projects sparked a lot of student creativity. OrchKids had always offered collective composition workshops in which students would improvise together around a theme to create a new piece, which they would then perform in a concert. “We found another way in the virtual space,” said Skinner. “Students would each record themselves playing their own stuff and send it in. We hired a producer to weave it all together and create a track. The kids were so free with their recordings.” In addition, a piece created during a live in-person performance “doesn’t live much past the concert. With the virtual workshop, we have the video that can keep being enjoyed.” They also used this approach to record different student groups performing when COVID concerns prevented the holding of a winter concert in December, as did Play on Philly.

Rebecca Henry was impressed with the creativity students showed in their online concerts during the shutdown, as they added “art, poetry and improvisations to stories that had more variety than our usual concerts. We will look for similar opportunities going forward.” So will Katrina Wreede, whose high school students put together a multimedia piece about water, adding their own photos to go with the music—one of the many creative projects in the Young Musicians Program that she coordinates and teaches in at the San Francisco Community Music Center. She is encouraging her students to keep developing the recording skills they learned during the pandemic and “create something and put it out into the world on YouTube. Some students did a project on their own this year. They created a video for new kids who came into the group, with tips on how to practice and other helpful things. It was so welcoming.”

Wreede also explored musical recordings on YouTube with students during the shutdown, doing more listening and analysis with them than she had before. So did Henry. Both hope to blend this into their in-person teaching. Both also noted another benefit of their weekly online lessons with students—they were important for the students’ well-being, creating “a safe place of peace, creativity, and music-making,” said Wreede. Henry added that the isolation caused by the shutdown was especially hard on teens. “Our weekly connections were more personal than before, as we all navigated the meaning of making music.”

Feature image: Play on Philly students performing at this Philadelphia program’s St. Rose of Lima Music Center. Courtesy Play on Philly, photo by Daniel Kontz.

January 28, 2022

“No jab, no job”? Compulsory vaccination and the law

The issue of so-called “compulsory vaccination” is an emotive one for many, and now with the rise of action being taken against unvaccinated employees it has become an employment law issue too. This is having an impact in two main areas: in the field of statutory sick pay and also whether employees in health and social care must be vaccinated.

Action against unvaccinated employeesIn recent weeks, a number of large British employers have followed their United States counterparts in withdrawing enhanced statutory sick pay from unvaccinated employees who have to self-isolate, leaving them to claim only the statutory amount of £96.35. These have included Pimlico Plumbers, Morrisons, IKEA, Next, and Wessex Water, and the number is increasing.

In addition, since November 2021, anyone who enters a registered care home (including employees) has had to be vaccinated unless they are exempt. This will be extended to those working in a patient-facing role in a health or social care workplace from April 2022, leading to fears that up to 80,000 NHS employees could be dismissed if they cannot be redeployed.

Compulsory vaccination?There have been claims that such requirements effectively impose a rule that employees must be vaccinated. Is it compulsory vaccination by any other name?

To force someone to be vaccinated against their will would almost certainly be an abuse of human rights (at the time of writing Austria has moved one step closer to being the first European country to introduce a mandatory vaccine order as their parliament’s lower house voted in favour of proposals.)

Insisting that a person is vaccinated, however, is not what these rules say. What the government and employers have done is to put conditions on those who are unvaccinated, whether it be the terms on which they are employed, or, in some countries (but not the United Kingdom (UK)), on what they can do (the latter are sometimes called “vaccine passports”). This is intended to encourage take-up of vaccines, but also has the effect of limiting the liberty and choices of those who are not vaccinated. The question considered here is whether such conditions are legal.

European Court of Human Rights casesThe issue of “compulsory vaccination” has not yet been tested in the British courts, but in the past year there have been cases in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)—of which the UK is still a member as it is unrelated to the European Union (EU)—which may give a flavour of what could happen here.

In the first, a non-COVID-19 case but similar scenario, Czech parents of children unvaccinated against childhood diseases were fined and their children refused admission to pre-school. The parents’ claims were made under Article 8 “the right to respect for private and family life” and Article 9 “freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.”

In some cases, rights under the European Convention—and thus the Human Rights Act, which brings these into British Law—can be justified in situations where the law is “lawful, necessary and proportionate.” Here, the court found against the parents even though their Article 8 right was breached because the purpose of the law was to guard against major disruptions to society caused by serious disease, namely the interests of public safety, the economic well-being of the country, or the prevention of disorder. This was necessary in a democratic society. It was also emphasised that there is an obligation on states to place the best interests of the child, and also those of children as a group, at the centre of all decisions affecting their health and development. When it comes to immunisation, the objective should be that every child is protected against serious diseases.

Since then the same court has refused to pause mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations for French fire fighters and Greek medics before the full trials are heard later this year.

Legal arguments for UK casesThere are also some laws specific to the UK that could be considered in any case brought here, and there are three main limbs of argument.

Note that for the legislation imposed on care providers, the avenue for that would be a court challenge to the legislation itself against the government, not against an employer, and this relates to the first two limbs of argument below. In other circumstances, however, if an employee is subjected to a detriment by their employer, they may have one or more of the following three arguments.

Human Rights ActThe first is under the Human Rights Act 1998, which can be used to bring a claim under the European Convention on Human Rights in the national courts.

As well as the Article 8 argument in the ECHR case above, the parents contended that vaccination was contrary to their Article 9 right. This claim was dismissed because the parents’ particular beliefs did not have sufficient “cogency, seriousness, cohesion, and importance” to be covered. Even if they did have, it is almost certain that the justification found for Article 8 in that case would also have applied to Article 9, and so the claim would have failed on that basis too, although here a court may find that someone does have a belief that is strong enough to be covered—it depends on the facts of each case.

There could be similar claims in the UK, although in the care providers’ case a justification by the government that it is necessary for the health of the population may be weakened compared to the childhood vaccinations given the huge numbers of people that may be affected and the consequent risk to the NHS.

Equality ActThe second argument comes under the Equality Act. There are a number of possible claims here. A pregnant employee who refused to get a vaccine could claim pregnancy discrimination, or there may be claims of race discrimination or discrimination against “religion and belief.”

Any conditions imposed on unvaccinated employees that put them at a disadvantage to vaccinated employees could disproportionately impact, for example, certain racial groups which have a lower take-up of vaccination. It may also impact more on people of certain religions, or those for whom anti-vaccination could be so cogent as to amount to a religious belief. This disproportionate impact is known as “indirect discrimination” but, like Articles 8 and 9, it may be justified, and it is possible, as in the ECHR case, that a court will find in such a case that the national interest in protecting the population or the interest of the other employees, patients, or other relevant persons would be sufficient to defeat the claim.

Contractual claimThe third area of claim in relation to the statutory sick pay issue (not the care providers’ legislation) would is related to employment law.

Any change to an employment contract would either have to be by agreement or the contract would have to allow an unilateral change by the employer, so there is a risk of breach of contract—although this is unlikely to be the case here as in most cases statutory sick pay for coronavirus illness is unlikely to be incorporated into the contract.

Any such change or requirement to be vaccinated can also be argued to be a breach of the employer’s duty of trust and confidence. If an employee feels that they have to leave their job because this duty has been breached by the employer, then this could amount to constructive dismissal.

There is also an issue about asking employees or potential employees about their health data, but again this may be justifiable.

The main issue to note is that any requirements or changes introduced by private employers must be thought about carefully and done after consultation, having checked employees’ contracts, to avoid legal action. In summary, there are a number of legal avenues under European and UK law that can be taken by those affected by the new “no jab, no job” rules imposed by employers and by the government, although, as discussed, success is not guaranteed as there are arguable cases for both sides.

Please note that this an overview of the law and is not intended to be legal advice, and each case depends on its own specific facts.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers