Oxford University Press's Blog, page 89

December 14, 2021

The sovereign duties of humanity: re-examining Bodin’s theory

Sovereignty is the grand prize of statehood in public international law, the touchstone of political independence. Its value derives from the monopoly it confers upon its holder, empowering it to do things that no else can—making and unmaking law, declaring war, signing treaties, establishing courts, laying taxes.

In principle, only states are supposed to enjoy this monopoly on sovereign rights. The historical record of the past half-century, however, reveals a different reality as these “sovereign functions” of states, as Frédéric Mégret has recently described them, have been delegated away to international governing bodies and courts or, in some cases, privatized entirely. The sudden de facto sovereignty acquired by the Taliban over Afghanistan in 2021 is only the most recent example illustrating the steady pace of sovereignty’s seemingly irreversible erosion and reconstitution in global politics.

The result has been an uneasy ambivalence about the place of sovereignty in the twenty-first century. Of course, populist politicians—the Bolsonaros, the Trumps, the Johnsons of the world—will continue to find ways to exploit sovereignty as a useful tool for electoral politics and as a justification for rejecting multilateralism. Indeed, the Brexit referendum of 2016 and the American withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord in 2017 have been characterized as “reassertions” of a dormant national sovereignty directed against faceless “global” elites.

At the same time, a general skepticism about sovereignty, in general, as an organizing principle of law and politics, has emboldened critics who would prefer to see a world without sovereignty. Only then can it be possible to realize what has been described as the “last utopia,” a durable regime of borderless global justice and human rights.

Realizing this vision of a sovereignty-free world has necessarily involved looking to the past, if only to understand the origins of this inheritance. One name always stands out above others in this search: the early modern French jurist and philosopher, Jean Bodin (c.1530-1596). More than anyone else, Bodin is credited with the (dis)honor of inventing the concept of sovereignty in its recognizably modern form in his monumental treatise on the state, Six Livres de la République, first published in 1576. In that work, Bodin offered what has become the canonical definition of sovereignty in the history of political and legal thought—the “absolute power” of the state, a quality essential to securing political independence.

“Bodin’s theory of sovereignty was never intended to be a license for complete lawlessness”

For generations, commentators treated Bodin’s analysis as a recipe for absolutism and a portentous vision of a modern “Westphalian” international order made up of territorially bound states, each with “absolute power” over its realm and people. Yet, Bodin’s theory of sovereignty was never intended to be a license for complete lawlessness, a point which he underlined with the observation that even sovereigns are bound by peremptory norms and requirements deriving from the law of nature [ius naturale] and the law of nations [ius gentium].

In my book, The Right of Sovereignty, I’ve documented many of the ways that Bodin repurposed the ius naturale and ius gentium as peremptory devices to constrain sovereignty, by burdening sovereign states with obligations which must be performed. While the classic example is the repayment of sovereign debts owed to private creditors, these sovereign duties arising from such peremptory norms also included a class of duties known generally as officia humanitatis, the “duties of humanity.”

Originally a term used in classical literature by writers such as Cicero, Quintilian, and Lactantius to indicate everyday common courtesies, officium humanitatis would later come to be associated with supererogatory duties in general, such as duties of hospitality, gratitude, courtesy, beneficence, and fidelity. Early modern jurists such as Grotius, Pufendorf, and Wolff would later characterize these humane duties as “imperfect,” because their performance, while virtuous and expected, was always optional. So, while it is morally upright and decorous to show, say, hospitality to strangers or gratitude to one’s benefactor, these are not strictly obligatory or actionable in a legal sense. Though it may be indecorous, discourteous, and, as Pufendorf once put it, even “boorish” in failing to observe such duties, one cannot, at least in modern law, be sued for inhospitality or ingratitude.

Bodin invoked these “humane” duties to reinforce a radically democratic point: even the mightiest of sovereigns, in spite of all their “absolute” sovereignty, remain bound to observe the same duties of humanity that the lowliest of subjects are always required to follow. He even borrows from the most advanced legal theories of contract enforcement then available, developed by canon lawyers of the Church, to argue that courts, as agents of equity, play an indispensable role in ensuring that even sovereigns perform these duties.

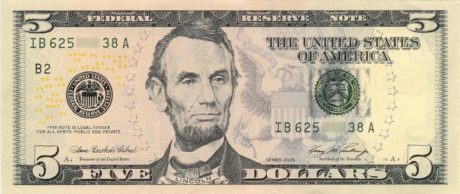

Applied to sovereign states, these humane duties translate into concrete policy prescriptions. For example, cash-strapped debt-burdened sovereigns, tempted to clip their coins or otherwise devalue currency, are strictly prohibited from doing so, in Bodin’s analysis, because it would be a direct violation of the humane duty of fidelity and fair-dealing owed to other sovereigns and to potential creditors. Reliably maintaining the value of one’s money as instruments of commerce, Bodin’s argument goes, reinforces the faith that sovereigns must keep not only with foreigners, but also with their own citizens who rely on stable monetary instruments.

Even more striking is the humane duty of mutual aid. Applied to sovereign states, Bodin translates it into the broad duty not only to receive and protect refugees fleeing oppression and sectarian violence, but also the duty of non-refoulement, prohibiting sovereigns from repatriating refugees to their country of origin, where they may be tortured or killed.

Bodin, traditionally viewed as the prophet foretelling the advent of the classical Westphalian theory of sovereignty, actually turns out then to undermine some of its foundational principles. What seems to have mattered more were the international duties entailed by the concept of sovereignty. So much of modern state-centric international law has been constructed on the assumption of the “absolute” rights of states, not only against other states, but even against their own citizens. But that leaves out the other half of the picture that Bodin—along with Gentili, Grotius, Pufendorf, Vattel—all acknowledged: the humane duties of sovereign states. Reimagining international law might well begin by recapturing these duties.

December 13, 2021

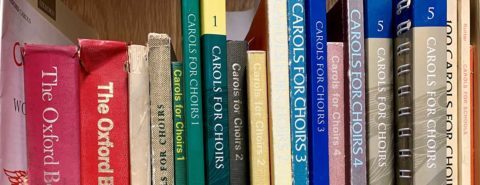

A history of the Carols for Choirs angel [gallery]

First published in 1961, the Carols for Choirs series has for many singers become synonymous with the Christmas season, used in festive concerts and services across the world. While many things have changed since that first edition, one thing has remained constant: the illustrated angel on the cover. We did some investigating in the archives recently to uncover the history of the Carols for Choirs angel, looking at how it came about and how it has evolved over the past 60 years.

[See image gallery at blog.oup.com]

December 12, 2021

Down the rabbit hole

If you are a writer, you’ve probably gone down a rabbit hole at one point or another. The idiom owes its meaning to Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in which Alice literally does that. She falls for a long time, Carroll tells us, as the rabbit hole turns into a tunnel, then a well:

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Research is like that, and we sometimes find ourselves bewitched, bothered, and begoogled by odd facts, ideas, and puzzles we come across. I went down one after learning that nineteenth-century Congressman David Crockett lent his name to a scathing 1835 hit job called The Life of Martin Van Buren: Heir-apparent to the “government,” and the Appointed Successor of General Andrew Jackson. I found myself wondering why Crockett disliked Van Buren so intensely. I never found out, but the database JSTOR led me to an article by Thomas E. Scruggs called “Davy Crockett and the Thieves of Jericho: An Analysis of the Shackford-Parrington Conspiracy Theory.” There I learned of the robust historical debate surrounding Crockett, his celebrity, and the authorship of his books. And I learned that while running for re-election to Congress in 1934, Crockett announced that if the people of Tennessee didn’t want him, “They can go to hell and I will go to Texas.” After losing re-election in 1934, he did just that and died at the Alamo in March 1835, before Van Buren was elected. My curiosity satisfied for the moment, I climbed out of the rabbit hole and I made a note to get a biography of Crockett so I could fill out my understanding of the “King of the Wild Frontier.”

I fell in a rabbit hole again listening to the audiobook of M. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became. I noticed the words cop-dar and city-dar, referring to characters’ abilities to sense police and to recognize aspects of the book’s animated city.These got me thinking of other extensions of –dar, the word part that arose from blending gay plus radar to gaydar.

Now, it seemed, –dar had become a new productive morpheme.Searching dar itself was pointless since Google doesn’t allow wildcards for partial words. A search of the quoted phrase “morpheme -dar” brought up couple of posts on the Language Log, yielding grammardar, sarcasmdar, humordar, sexdar, fishdar, and –dar connected with various ethnic identities. A 2016 “Among the New Words” roundup in the journal American Speech added nerdar and assholedar. The Urban Dictionary had more, including Qdar, for the ability to recognize Q-Anon followers.

Eventually, it occurred to me to search “dar is broken” since so many of the examples occurred in that context. And in this way, I found meme-dar, boy-dar, bi-dar, love-dar, fake-dar, man-dar, racism-dar, asshole-dar, bullshit-dar, troll-dar, and even shoe-dar. There were also examples of ‘dar standing alone when the context made things clear. I put –dar aside, confident that here was something deserving more study when there was time.

Often a rabbit hole involves a quote. I was curious about the description of Herber Hoover as “a fat, timid capon.” Who said it? Some sources attributed it to supporters of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. Others attributed it to FDR himself. But a search of Time magazine turned up something, from 1928, four years before the FDR-Hoover matchup:

An insult from Editor William Allen White, Republican, of the Emporia, Kan., Gazette to Candidate Hoover which will not soon be forgotten was the following, circulated in public prints last week:

“In the Republican shambles, he [Mr. Hoover] is vaguely reminiscent of a plump and timorous capon, fluttering anxiously on the outskirts of a free-for-all cockfight.”

A Newpapers.com search confirmed the capon dust-up as occurring well before the 1932 election. It’s likely that FDR or his supporters (or both) picked up the capon jab from White and recycled it four years later. And the wording shifted over the years from plump to fat and from timorous to timid. When I did the section on Hoover in my book Dangerous Crooked Scoundrels, I left out the capon line since it had too many twists and turns for easy explanation. But at least I had satisfied my rabbit-hole curiosity.

Rabbit-holes are inevitable. And as writers it’s okay to indulge ourselves every now and then. Alice and company would certainly approve.

Feature image: “Page 110 Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Carrol, Robinson, 1907)” by Charles Robinson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

December 10, 2021

Christmas with Ralph Vaughan Williams and The Oxford Book of Carols

The Oxford Book of Carols (1928) was the brainchild of Reverend Percy Dearmer. Dearmer was a socialist, high church Anglican liturgist who believed that music should be at the core of Christian worship, and was the author of The Parson’s Handbook, published in 1899:

“The parson should beg his people to discourage small boys from begging in Advent under the pretext of singing carols—if it can be called singing. It is really a sin to give pence to children for degrading themselves and dishonouring sacred things. Perhaps the best remedy is for members of the congregation or the choir themselves to sing carols in the streets.”

From The Parson’s Handbook

He worked with musical editors Ralph Vaughan Williams and Martin Shaw. The three of them had recently collaborated on Songs of Praise, and Vaughan Williams and Dearmer had edited The English Hymnal in the early years of the century.

Dearmer wrote that “Carols are songs with a religious impulse that are simple, hilarious, popular, and modern.” “Hilarious” must mean light-hearted in this context, and “modern” for their time: he dates them from the fifteenth-century “because people wanted something less severe than the old Latin office hymns, something more vivacious than the plainsong melodies.” Many early carols survived only as folk songs after the temporary abolition of Christmas celebrations under the Puritans in 1647. The Oxford Book of Carols (OBC) was an attempt to bring together the best of what had survived both at home and abroad, in its original form as far as possible, with the addition of several new tunes.

The OBC covered far more than just material for December. Certainly, there were carols for Advent, Christmas Eve (both sacred and secular) and Christmas, but also for Epiphany, Candlemas, Lent, Passiontide, Easter, Ascension, Whitsun, and Trinity. Seasonal carols for spring, May, summer, harvest, autumn, and winter were joined by a selection of Nativity carols that were also appropriate for general use, carols for saints’ days and dedication festivals, and carols “suitable for use in procession.” And there were a number of general carols, some of which were labelled cradle songs, medieval, legendary, and carols of praise.

It is argued that 1928 was the annus mirabilis of the carol, particularly the Christmas carol. Not only was OBC published, but the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols was broadcast from the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge for the first time.

The King’s Carol Service has become a global phenomenon, and its repertoire over the years relied heavily on the late-Victorian Christmas Carols New & Old and the modern Carols for Choirs. In between those multi-volume series, the inter-war OBC shone as a beacon of experimentation within tradition. It is that ritualised innovation that made OBC what it remains today: a visionary musico-poetic collection of the most profoundly partisan nature.

We have become used to atmospheric settings, with spectacular last verses, to be enjoyed as a performance. Vaughan Williams was writing more for carol singers and congregations than for cathedrals and choirs, and the settings are straightforward. However, Dearmer’s preface suggests that variety in the method of singing is important, with a mixture of harmony and unison verses, and antiphonal effects; he also endorsed the abbreviation of longer carols.

Albion Records (the recording arm of The Ralph Vaughan Williams Society) has recently released its second album of carol settings by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The new album, An Oxford Christmas draws heavily on OBC, with 20 arrangements from that book (including two with contributions from Martin Shaw), as well as two later carols.

The preceding album was A Vaughan Williams Christmas. This includes four original carols by Vaughan Williams and 19 of his arrangements, including Nine Carols For Male Voices written in 1941 for British troops serving in an army of “friendly occupation” in Iceland. The reviewer for Gramophone magazine wrote that the austerity of these nine carols “can stop you in your tracks; it’s difficult to hear the Mummers’ Carol without considering the British troops for whom it was written, stationed in windswept Iceland during the Second World War.”

The performers on Albion’s two Christmas albums are the Chapel Choir of Royal Hospital Chelsea, directed by William Vann, with organists Hugh Rowlands and Joshua Ryan. There are many solo verses, which are sung by about half of the members of the choir.

Ralph Vaughan Williams’s 150th birthday in October 2022 will be marked by a wide range of events around the world throughout the year.

Featured image by Aaron Burden via Unsplash

Protecting the protectors: how safe is life for humanitarian workers in conflict zones?

In a world affected by brutal civil conflicts, endless proxy wars, violent extremism and warlordism, and now reckoning with the impact of COVID-19, the need to assist vulnerable people will continue to expand. In parallel, the security conditions in which humanitarian workers are deployed and operate in various conflict zones will become an increasingly relevant issue. Although debates among scholars and practitioners are growing, the severity and urgency of the issue continues to be underestimated, particularly at the UN level.

Although it is common to hear about bombings, kidnapping and murder, sexual harassment, armed robbery, and individuals caught in crossfire, incidents reported by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) do not always draw the attention of media and public concern. According to the Aid Worker Security Database, from 1997 to the present, incidents involving aid workers have been frequent and are growing, along with the spread of conflicts and crises. “Humanitarian aid workers” is a broad category, including staff of local and international NGOs, international organisations and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Among them, NGO workers, especially local ones, are most often exposed to violence, although UN and ICRC staff have not been exempted.

Humanitarian workers may be involved in generic attacks aimed at civilians, but most often they are victims of targeted attacks and deliberate violent strategies by local non-state armed groups (NSAGs) or more organised groups like Taliban, Al-Nusra, Al-Qaida, ISIS, and Al Shabaab. Such attacks are often instigated because humanitarian workers are perceived as having colluded with the “enemy” and associated with an opposing party. Their presence on-field and their roles in communities can be easily distorted among the local population and manipulated to justify violence against them.

What can we do to protect humanitarian workers?What can be done to protect them while allowing them to do their jobs even in highly dangerous zones? Humanitarian workers are usually subject to proper training courses and basic knowledge of logistics. Additionally, they are aware of the on-field risk they may encounter. However, this may not be enough to safeguard them and guarantee the assistance they provide to local communities.

The most important factor is understanding the extent to which local conditions either allow their mission with some adaption or become so difficult that they require partial or total suspension. A reduction of activities and personnel may be a common practice in such instances, though this always implies a shift in the approach, which may cause political and ethical issues. The practice of remote management, the operational response to insecurity involves a large reduction of international and sometimes national personnel from the field. It consists of the transferral of larger programme responsibilities to local staff or local partner organisations. This is not always perceived as a productive strategy: it interrupts the direct monitoring of project implementation and coordination that is one of the most important added values aid workers may provide, particularly in those contexts in which local civil society actors are more vulnerable. The partial transferral of tasks may also expand the criticality and sensitiveness of the programmes, reduce the feasibility of technical aspects, and challenge the expertise and availability of local partners. Still, remote management practices are preferred to the complete suspension of activity, a drastic decision that impacts the organisation’s performance and humanitarian work and can be the last resort.

The worsening of security conditions for humanitarian workers is a problem that cannot be definitively solved; it is a consequence of the deep changes that global and regional security are encountering. Multi-layered and complex civil conflicts and proxy wars require integrated humanitarian interventions in which the civilian dimension is dominant. The more humanitarian workers continue to be deployed on-field and involved in various tasks, the less secure their working conditions will be.

Despite the visibility of attacks in media reports, problems encountered by NGOs in conflict zones remain an under-researched and undervalued issue that deserves more attention. More comparative data analysis concerning not only general reflections on the level, cause, and consequences of violent attacks on humanitarian workers but specific contexts and their correlation with the most striking contemporary conflicts is desperately needed to build knowledge and inform policy.

The strengthening of security conditions for all humanitarian workers should enter the political agendas of international and regional organisations and be part of debates on conflict management and external interventions. It should become a concern for all major humanitarian agencies to promote a broader collective reflection on the actual preparation of workers and the dynamics of mission tasks.

Feature image source: US National Archives

December 8, 2021

The wiles of folk etymology

Words, as linguistics tells us, are conventional signs. Some natural phenomenon is called rain or snow, and, if you don’t know what those words mean, you will never guess. But everything in our consciousness militates against such a rupture between word and thing. That is why we love words that reveal their origin: sound-symbolic formations and onomatopoeias. Take Henry Fielding’s Squire Allworthy, Oliver Twist’s tyrant Mr Bumble, David Copperfield’s tormentor Mr Creakle, and their ilk. It is gratifying to learn that Mr Allworthy was the very embodiment of worth, that Mr Bumble was a cross between a pernicious bumblebee and a bungler, and that Mr Creakle had no voice. Etymologists try to show that once upon a time all words had meaningful beginnings, and occasionally they succeed. When they fail, people take control of the business and (to give one example) begin to discuss among themselves whether a certain project is hare- or hairbrained. This is not a silly question, especially if you remember how quick hares are and how thin a hair may be. To add more confusion to this type of reasoning, stained sycamore wood is hare– or hairwood, though it has nothing to do with either hares or hair.

The process of turning the incomprehensible foreign word asparagus into a decipherable monster called sparrowgrass is known as folk (or popular) etymology. The term Volksetymologie was coined in the nineteenth century by a German scholar and soon spread all over the world. In English, sparrowgrass has given a rich yield. The history of some words in this group is instructive and amusing. Below, I’ll speak about two of them.

Wormwood A regular worm wood.

A regular worm wood.Image by Danna & Curious Tangles via Flickr

This plant name goes back to Old English, where it sounded wermōd and had very similar cognates elsewhere in West Germanic. We cannot decide whether wermōd was werm-ōd or wer-mōd. In no Old Germanic language was the worm called werm; the recorded forms were wurm, wyrm, wirm, and so forth. Though absinthium “wormwood” was indeed used as a remedy against worms, the vowels in the words that interest us do not match. Alas, vowels, not worms, bother etymologists. If our starting point is wer-mōd, it is perhaps possible to associate wer– with Old Engl. werian “to protect, defend” (compare German wehren, familiar to many from Wehr-macht “the defense branch of the Third Reich”). Mōd will then emerge as the ancestor of Modern Engl. mood, which in the Old English period meant “mind, thought.” Thus, “keep-mind, thought-preserver,” from a belief in its medicinal virtue? Similar beliefs associated with the plant world, though not specifically with wormwood, have been recorded.

But if werm– in wermōd refers to worms, what is –od? Such a suffix did exist in Germanic. It has been well-preserved in several forms in Modern German, for example, in Heim-at “homeland” (heim “home”), Arm-ut “poverty” (arm “poor”), Ein-öd-e “desert, wasteland” (ein “one), and others. It is no longer understood as a suffix (hence the multiplicity of forms, and the words with the remnants of it can belong to any of the three grammatical genders). Unfortunately, werm– makes little sense. An old etymology tried to associate wormwood with warmth, “on account of the warmth this plant produces in the stomach.” Wormwood is widely used in medicine. I do not know whether wormwood warms the stomach or perhaps even the cockles of one’s heart, but the vowels u ~ a (again vowels!) in the Old English roots are incompatible. Perhaps even in Old English, the word fell victim to the pressure of folk etymology and m did appear under the influence of worm? Then the root is wer-, but, even if so, it hardly meant “to defend.”

A reincarnation of the plant.

A reincarnation of the plant.Image by Kenneth C. Zirkel via Wikimedia Commons

I have often referred to the mysterious prefix known as s-mobile, that is, “movable s.” It attaches itself to roots for the reasons no one has been able to explain with sufficient clarity. (Since I am speaking about wood, I might perhaps mention the fact that Francis A. Wood, an extremely knowledgeable and prolific etymologist of the Chicago school, mocked the idea of s-mobile; however, this spurious but intractable element exists.) There is a Celtic root swer-, which means “bitter.” Celtic is an Indo-European language, like Germanic, so that light from Old Irish and Welsh should never be ignored in discussing a Germanic word. But in this case the light is dim, and the etymology of wormwood as a bitter plant (the plant is indeed bitter) is no more than a guess. Given this interpretation, the second syllable will remain a suffix. It is no wonder that our dictionaries call wormwood a word of unknown or obscure origin. Yet one thing seems to be rather certain. The plant name has nothing to do with worms; werm-ōd or wer-mōd, the association with worms seems to be a product of folk etymology. In English, the second w (wormwood) arose under the influence of the first or is another tribute to folk etymology: wormwood is a rather woody plant! A bitter story: etymological gall and wormwood. One consolation is that the German cognate of wormwood is Wermut (Anglicized as Wermouth or Vermouth and now producing another wrong association, this time with mouth!)—that is, if you are not teetotal and have a taste for fortified wines.

MassacreI am sorry if my today’s examples happen to leave a bitter taste. Such was not my intention. The word massacre surfaced in English in the sixteenth century and is a borrowing from Old French, but its origin in that language has not been found. Only folk etymology has no problems with massacre: “of course,” it means “mass killing.” No, it does not. In Old French, the word had several variants: massacre, maçacre, macecre, and macecle. This instability shows that the origin of the word was even then not clear to the speakers and that the root mass– may have been associated with the noun mass long ago. According to an ingenious hypothesis, massacre is a blend of (am)mazzare “‘to slaughter, kill” (compare Engl. macerate and emaciate) and sacrare “to consecrate” (both forms are given here in their Modern Italian forms). Such blends exist. For example, vituperate goes back to Latin vitium “blemish” and parare “to prepare.” But the existence of a blend, unless the blending has occurred before our eyes (as in Brexit, blog, or smog), is hard to prove.

Old or new, massacres are equally horrifying.

Old or new, massacres are equally horrifying.“Claudius Civilis Defeats the Roman Troops near the Rhine in 69 AD”, Rijksmuseum via Picryl.

A more reasonable hypothesis traces the French word to Germanic. German metzeln means “to butchery, slaughter,” and the corresponding noun is Metzelei. Its source is Latin mactare “to sacrifice a victim; destroy.” (Those familiar with German will recognize Metzger “butcher,” now a northern word, but formerly current in the south.) If this derivation is correct, massacre was coined in the Germanic-speaking area, traveled to France, and then returned—indeed, not exactly home but closer to the place of birth. But we cannot be sure that such is the true story of massacre. As in the discussion of wormwood, my goal was to show how people try to make words mean what words are supposed to mean. With massacre the fit is perfect: the word indeed presupposes the destruction of great masses of people, but in the story of wormwood folk etymology leads us astray: the plant is not wormy, and wood has very little to do with it. Yet worms are indeed afraid of wormwood. Poetic justice can be expected everywhere, even in etymology and pharmacology.

Feature image by Eddideigel via Wikimedia Commons

December 7, 2021

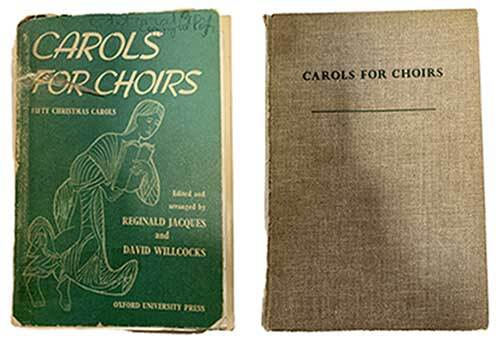

Carols for Choirs: the journey to press

In 1928, Oxford University Press (OUP) published The Oxford Book of Carols. This was one of the earliest productions of the Press’s own new music department, founded in 1923. The Oxford Book of Carols (OBC) was a hugely popular landmark publication and remains in print to this day. It gathered together for the first time the music and words of many traditional British Christmas and Easter carols which, having been passed on orally, were in real danger of disappearing for all time. The editors Ralph Vaughan Williams, Percy Dearmer, and Martin Shaw also selected some “original” choral compositions on Christmas themes, and these were loosely embraced in the book as “carols” too. Christmas hymns such as “O little town of Bethlehem,” and “O come, all ye faithful,” however, were excluded on the basis that they were not really “carols.”

A meeting of Willcocks, Jacques, Morris, and Alan Frank on 2 January 1961, revealing some of the planning process behind the book.

A meeting of Willcocks, Jacques, Morris, and Alan Frank on 2 January 1961, revealing some of the planning process behind the book.Source: OUP Archive, Carols for Choirs Book 1 editorial files. Reproduced by kind permission of the Secretary to the Delegates of Oxford University Press

By the late 1950s, OUP was beginning to consider a revision to OBC to include the by-now enormously popular Christmas hymns, which of course were included in almost every hymn book going (including OUP’s own English Hymnal and Songs of Praise). It was found, however, that the original contracts with the OBC editors prevented any form of later revision. Christopher Morris, the music editor for OUP in 1960 (who later became Head of Music), decided that OBC was “miles out of date” and that, because he was unable to revise it, a new carol book that was modern, practical, and inexpensive, giving the same accessibility to material but under one cover, was required.

In Cambridge in 1958, David Willcocks (then Director of Music at King’s College) had given a hugely successful Christmas concert featuring several of his own carol arrangements and descants. This piqued the interest of OUP editors and led to several of his arrangements being published. In an interview given in 2004 for A Life in Music (a book celebrating the musical life of Sir David Willcocks) Christopher Morris recalled how he approached Willcocks about a new anthology:

David … said it would be very nice if we could find a book, for instance, for choral societies’ annual carol concerts, that had everything included, so that the singers, instead of having fifteen sheets of paper under their seats, could merely turn to page seventeen for the next carol! So we worked on the idea of having a book which would provide music for a whole concert.

Preparation began with Willcocks working with Reginald Jacques (conductor of the Bach Choir of London) as joint editors. The selection of what became the now familiar contents list of the first Carols for Choirs was essentially complete by the summer of 1960. The archive files give a picture of what was not included, items considered but then, for one reason or another, rejected: a new carol from Britten, The Holy Son by Peter Hurford, and Lullay my liking by Holst, amongst others. Two crucial changes were made as work progressed: first, the original working title, Carols for Concerts, was altered to Carols for Choirs, opening the book’s market to choirs of all descriptions rather than choral societies only; and second, a decision was made to include an order of service for the benefit of church choirs, which modelled their services on the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at King’s—by then enormously popular through the BBC’s annual live radio relays.

Limp and board first edition of Carols for Choirs 1, published 24th August 1961

Limp and board first edition of Carols for Choirs 1, published 24th August 1961The content embraced at last the standard Christmas hymns, several with powerful descants and last verse arrangements by Willcocks, alongside four newly commissioned works (William Walton contributed What Cheer? and Arnold Cooke the delicate and pastel shaded O men from the fields), and, of course, traditional carols (some drawn from OBC). The editors also decided to orchestrate several of the items, and the orchestral parts were made available on hire: this alone contributed significantly to the eventual success of Carols for Choirs.

Carols for Choirs was published on 24 August 1961 in boards and limp editions. A note from Alan Frank dated 25 August 1961 reveals the atmosphere of excitement around the publication, with Frank noting “my colleagues and I have rarely felt as excited as we have done during the production of this book.” 30,000 copies were printed in the first run, and these had sold out completely by November. Barry Rose, then organist at Guildford Cathedral, succinctly encapsulated general reaction in a letter of thanks to Alan Frank: “… you obviously don’t need me to tell you that this is going to be a ‘winner.’ Never before, have I seen such a sensible & delightful collection of Carols under one Cover.” There was unanimous agreement, and since that August publication day Carols for Choirs has sold over 467,000 copies.

December 2, 2021

Knowing one’s opinion is worth hearing

In her mid-80s, Mary Midgley mused that she might never have become a philosopher if it weren’t for the extraordinary circumstances of wartime Oxford. In September 1939, one year into her university education, nearly all Britain’s men between 18 and 41 were conscripted into military service. For a few years, then, the University of Oxford was populated mostly by women.

“The effect,” Midgley wrote, “was to make it a great deal easier for a woman to be heard in discussion than it is in normal times. Sheer loudness of voice has a lot to do with the difficulty, but there is also a temperamental difference about confidence—about the amount of work that one thinks is needed to make one’s opinion worth hearing.”

What’s undeniable is the shift. Before the 1940s, only a few women in the English-speaking world had ever made careers in philosophy. In 1939, only two of Oxford’s women’s colleges even had a philosophy tutor. But the war years produced four of the most original writers on ethics of the second half of the twentieth century: Midgley, Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, and Iris Murdoch.

They found their voices, perhaps, because suddenly no one was speaking over them. But Midgley’s second conjecture, about confidence, seems a more powerful explanation.

What builds confidence? The experience of being taken seriously by people one respects, certainly. And during their university years, Midgley and her peers had the full attention of their tutors. That might not have happened if they had come up in 1935 rather than in 1937, 1938, 1939. Until 1939, up-and-coming philosophers had a profile: educated at elite boys’ schools, masterfully proficient in Greek and Latin, quick-spoken and combative. Women didn’t fit the stereotype. When Anscombe—the most self-possessed and brilliant of the quartet—sought a recommendation from her post-graduate mentor, Ludwig Wittgenstein, he wrote that she was the most capable “female student” he had taught since 1930, and perhaps in the top ten overall. Others saw more quickly who she was. Gilbert Ryle, the acknowledged leader of the Oxford philosophy subfaculty, wrote that he and his colleagues were in awe of her. But even an impressed and attentive mentor like Wittgenstein needed time to recognize what was in front of him. It simply wasn’t what he was used to seeing.

Anscombe, Midgley, Foot, and Murdoch were all gripped by self-doubt at the start of their careers. In Anscombe’s first scholarly publication, “The Reality of the Past,” she belittles her work as “a weak copy” of Wittgenstein’s. It would be almost a decade before she would begin to speak for herself in print. It was outrage that finally made her self-forgetful. As a Catholic in anti-Catholic England, Anscombe had always had moral courage. She had no problem standing alone. It was only as a scholar that she doubted herself. But when Oxford, where she now taught, proposed to give former US President Harry Truman an honorary degree, Anscombe commenced a stream of publications, first denouncing Truman for his murder of the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (“Mr Truman’s Degree”), then denouncing her colleagues for refusing to take her objection seriously (“Does Oxford Moral Philosophy Corrupt Youth?”). Outrage finally led her too to in-depth reflections about human action—whereupon she promptly published her short monograph, Intention, which Donald Davidson called “the most important treatment of action since Aristotle.”

The other three were no less debilitatingly self-conscious, early on. Murdoch was as overawed by Anscombe as Anscombe was by Wittgenstein. Murdoch wrote to Foot in 1947 that she doubted her “reality as a thinker.” And she never fully overcame these doubts. Her best work, such as the essays collected in The Sovereignty of Good, was idiosyncratic, synthesizing and comparing contemporary French and British thought in ways that no one else in her milieu even attempted. Working so alone, Murdoch was especially vulnerable to losing faith in herself as a philosopher. After 1963, she turned chiefly to her fiction. She never stopped writing philosophy, but she also never silenced her inner critic. She lamented to Foot that her Gifford lectures were “senseless.” It is only in the past couple of decades that philosophers have begun to reckon with her significance.

Foot’s path to philosophical self-confidence was the most straightforward. She too adulated Anscombe and for a time wondered if she herself had anything worthwhile to contribute. But for the nearly two-and-a-half decades that they worked together at Somerville College, Oxford, Foot apprenticed herself to her older colleague. They met every weekday afternoon in the Somerville Senior Common Room, where Anscombe gave Foot an open-ended, advanced tutorial. After a decade of this, in 1957, Foot knew what she wanted to say. Foot’s career from that point is a testimony to the power of sustained mentorship, and of one woman’s capacity to empower another. Foot for her part became the best mentor of any of the four, doing for a generation of women and men, first at Oxford and then at UCLA, what Anscombe had done for her.

Midgley was perhaps the most self-possessed of her friends. But she was also the last to truly find her voice.

Like Murdoch, she had unconventional interests. Midgley saw that an adequate ethics had to connect seriously to biology and psychology. It is no good talking about the good life for humans without considering the kind of animals we are. But the scope of Midgley’s questions struck even her friends (Foot, for one) as unprofessional. It was painful and disorienting. “It is so difficult,” she wrote at the time, “to insist that a thing is interesting when one’s colleagues are bored with it.” Absent from the academy while she raised her three sons, though, Midgley had her family and colleagues in the sciences (and her fellow outsider, Murdoch) to support her belief in the value of her work. She published Beast and Man, the first of sixteen books, at age 59.

Her story—and not only hers—is a lesson in the difference it makes when someone listens, and when someone encourages someone else to speak.

December 1, 2021

Winter etymology gleanings

When in March 2006 this blog came into existence, the idea was that I would be inundated with letters, comments, and questions to which I would respond once a month. The flood did not materialize; yet a trickle has never run dry. In recent weeks, even comments have become rare. I assume that the COVID horror and the political climate in the whole world do not foster people’s interest in historical linguistics, though, whenever I speak on the radio or by Zoom, sizable crowds gather to listen to the “news” (the origin of obscure words, the vagaries of modern usage, Spelling Reform, or whatever). Our regular readers may have noticed that my gleanings have become scarce. Yet some questions and comments keep coming my way, and, since the year is drawing to an end, I decided to inspect my archive and post the last gleanings of 2021.

UsageAn occasional contributor to the Minneapolis StarTribune (I live in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and subscribe to the largest local newspaper) often received letters about the misuse of the apostrophe. It is an old hat, but some of the examples are mildly amusing. A CEO reminds the shop workers to pay their due’s. Some company advertises taco’s. In the same vein, quite a few of my students have never learned the difference between its and it’s. Long, long ago, we were told that grammar is not FUN, and as a result, we provide the world with due’s and taco’s. One often reads that language is changing and that only old fogies resist progress. True enough. “Me and him are going on a ski trip in Colorado,” “It’s a gift to you and I,” and so forth. Since the days of King Alfred, English has lost nearly the whole of its morphology. Why not lose what little is still left? I agree and only refuse to be the standard-bearer of progress, just as I refuse to say and write: “President Joe Biden is mistaken to now hope….” Whether he is mistaken or justified in cherishing some hopes, I keep saying to be or not to be, rather than to be or to not be.

Serving an enlightened populace

Serving an enlightened populaceImages: (left) © Copyright Neil Theasby (CC BY-SA 2.0), (right) Brian Kelly (CC BY 2.0)

I would like to reproduce a comment from my colleague Dr Ari Hoptman and wonder whether other opinions on this point exist. He writes: “Apparently, a couple of generations ago, a 50 dollars fine and a two weeks vacation were normal. [My spellchecker asks me whether I want the noun to be in the singular or in the plural. It also inquires whether I need week’s or weeks’. It is a very particular spellchecker.] For some reason, a two weeks vacation still sounds a bit more OK than a 50 dollars fine. I don’t think you could ever say a five dollars bill.” Likewise, he adds, a five minutes’ walk and a three weeks anniversary have become a five-minute walk and a three-week anniversary. His usage agrees with mine, but it’s curious to read nineteenth- and twentieth-century grammars, both British and American, on this point. Comments, as noted, are welcome.

Equally often I receive complaints about the overuse of buzzwords. Weeds are ineradicable. If I am not mistaken, the ubiquitous phrase you know has all but disappeared (“I came, you know, and he says, you know: ‘Well, you know, of all people!’.” I was once present at a dissertation defense, and half of the introductory speech by the prospective PhD consisted of you know; I forget the other half: it was rather trivial.) Now it is like (“I came, like, half an hour before the beginning, and, like, there was not a single free seat.”). One of my students always says like before the first word: it is like clearing the throat. At a recent linguistic conference, a keynote speaker was invited with a presentation on the profundity of this phenomenon. As a clever nineteenth-century author wrote on another occasion: “The futile pastime of misguided acumen.”

There is not, like, a free seat here

There is not, like, a free seat hereImage by Jim Bahn via Wikimedia Commons

Here is a short list of such cliches from newspapers. When two heads of state meet, they always huddle together or hunker down for discussion. The invariable European context for Donald Trump was: “In Germany, where he is deeply unpopular…” Tragic situations begin to sound trivial because the same shopworn words are used to describe them. After a long battle with cancer, a person dies, shocks go through the community (or the community is stunned). Counselors arrive and teach people to cope with grief, after which the process of healing begins. “Tired of all this, for peaceful death I cry”: no counselors, no coping, no postmortem healing. My list of hackneyed words is endless. This vocabulary is particularly irritating, because journalists are trained to avoid everyday words and stun the public with exotic synonyms, just to show off (loquacious for eloquent or glib and “such-like” stuff).

EtymologyOn October 20, 2021, I wrote a post on the origin of the word spook. In a comment, a Dutch scholar offered his etymology of it. He derived the word from the root of early Modern Dutch spoken “to reflect” and noted that Dutch spook also once meant “omen.” In his opinion, the word owes its existence to the concept of divination. The Indo-European root allegedly meant “see, look, observe.” This may be a correct etymology, but, like mine, it has a few weaknesses. Ghosts have no obvious ties to divination but have everything to do with frightening people and leading them astray. Also, in this context, I would stay away from Icelandic spá-kona “seeress,” for here special pleading is needed to justify the sound correspondence. After all our efforts, spook will remain a word “of unknown origin,” but every new effort may be a step in the right direction. (And in answer to another comment: yes, h in ghost owes its existence to Caxton.)

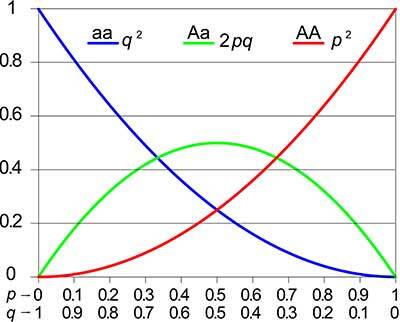

The Hardy-Weinberg principle, or mind your p’s and q’s (suggested by a geneticist and a friend of the Oxford Etymologist)

The Hardy-Weinberg principle, or mind your p’s and q’s (suggested by a geneticist and a friend of the Oxford Etymologist)Image by Johnuniq via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)Distant etymologies

I am in regular correspondence with two people. One is the Rumanian etymologist Ion Carstoiu, the name of the other I won’t disclose, but he allowed me to post his letter. After some of my essays, he suggests a Hebrew-Yiddish origin of the word I discuss. Here is the letter.

The published etymology for pumpernickel (in etymonline, for instance) is too ridiculous for dispute. I suspect it has a Yiddish origin.

It was a bread first eaten by the “common people”, not the elite. The borrowed-into-Hebrew word for the public is PuMBi. This bread was and often still is made with fermented dough, usually called sourdough. The word FeRMent was borrowed into both Hebrew and Yiddish. And NicKeL looks like a reversal of LeKheM (bread), a Hebrew word that every Yiddish speaker would know. But (RN)iKeL may be a reversal of Yiddish meL Ka(RN) = rye flour. And PuMBi may also be a reversal since the MB has become an MP.

In other words, it looks like a bread made with fermented rye flour and that is exactly what it is.

I stand in awe of his ingenuity but try to save my approach. Why is it so easy to come up with such solutions? Mr Constantinos Ragazas keeps insisting that numerous English words are not cognates of the related words in Greek but borrowings of very early Greek nouns and verbs. In “my” etymology, every step is shaky, while in “theirs” everything is fully convincing. I am beginning to lose ground. Are we back in the Middle Ages? Did Rasmus Rask and Jacob Grimm ever live? By contrast, Mr Carstoiu has no historical “agenda,” and, as far as I can judge, he is not an advocate of Nostratic linguistics. Yet he has put together numerous lists that show that all over the world words denoting a certain object sound alike. Those words are seldom expressive, as are those in Wilhelm Oehl’s lists. For instance, words for “earth” tend to begin with the syllable re. Why do they? He asks me: “Are those numerous coincidences due to chance?” Food for thought, isn’t it?

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons

City spaces, pace bias, and the production of disability

How does our body shape our experience of living in a city? How do urban spaces support or undermine the well-being and agency of people with bodies of particular shapes and capacities? Most obviously, spaces may be inaccessible to wheelchair users or those with other kinds of limited mobility. But there are all sorts of other ways in which spaces can include or exclude those with different capacities. Deaf people need to be able to see one another to converse, so their ability to use spaces with narrow, single-file-only walking areas for normal kinds of social interactions is curtailed. Noisy or chaotic areas may be unusable for people with sensory processing disorders. Theaters with small seats, or hotels or hospitals with narrow beds, may be unusable by large people.

More generally, Susan Wendell argues,

The public world is the world of strength, performance, and production … We have built spaces around the idea that “normal” bodies can lift things, move quickly, and be available any time for ‘production.’ Public space has been structured as though no one of any importance in the public world… has to breast feed a baby or look after a sick child…. Much of the public world is also structured as though everyone were physically strong, as though all bodies were shaped the same, as though everyone could walk, hear, and see well, as though everyone could work and play at a pace that is not compatible with any kind of illness or pain, as though no one were ever dizzy or incontinent or simply needed to sit or lie down. (For instance, where could you rest for a few minutes in a supermarket if you needed to?).

Wendell, 1997, 40

Her point about supermarkets was especially striking to me when I first read it; everyone needs food, yet we have created physical spaces for obtaining food that are built upon ableist assumptions, and around the principle of getting people through the store as quickly and efficiently as possible, never mind who gets excluded or left behind. These assumptions of ability and “productivity” are built into the material form of most of our shared city spaces, and into our embodied norms for how to use them.

I want to focus on one fascinating dimension along which bodies are included in or excluded from spaces, namely pace. Wendell explores pace differences as a socially powerful form of bodily diversity, and pace bias as a pervasive form of ableism. She points out that we are trained up to value speed of work and motion, and we treat those who move or “produce” at a slower pace as less valuable, rather than as simply temporally different.

My recognition of pace bias in myself when I read Wendell’s book was a major revelation for me; while I had tried to critically reflect on my own racism, sexism, fatphobia, and the like, it had never occurred to me that my own pride in my fast pace, and my frustration with those who moved or talked slowly (whether because of biological or cultural differences), was a form of ableist bigotry. But the quality and value of what one does isn’t connected in any obvious way to how fast one does it. It is an internalized piece of insidious capitalist ideology to think that those who are slower-paced are less valuable because they are less “productive.”

City spaces each have their own entrenched pace. Places are structured by what David Seamon calls place ballets—bodily habits and routines that are intertwined with their environments. People move in distinctive ways in train stations, grocery stores, and school yards, for instance, and these movements are shaped by and give meaning to the physical structure of these spaces. You cannot coherently move as you would in a grocery store if you’re standing on a train platform, and vice-versa: place ballets are essentially constituted by the material places in which they are situated. The point that is important to me here is that place ballets have a rhythm and a pace to them. This pace, although culturally variable, usually develops around the assumption that these spaces are for traditional “productive” bodies, and that faster is better. If someone cannot keep up with the pace of a space’s place ballets then this will put them out of sync with that space and make it less usable for them. This mismatch between the pace of a person and the pace of a space may literally produce disability, even in someone who would not be disabled in a space with a slower-paced place ballet.

We see this regularly in busy city spaces, where some bodies can’t keep up, and get pushed around or left behind. To some extent, this kind of exclusion is no one’s “fault.” City spaces develop paced place ballets through slow sedimentation, and we cannot plausibly expect everyone to slow down to match the pace of someone slower than the norm. The problem is that a slower pace is not just a mere difference that causes a spatial mismatch; it is deeply disvalued. City spaces don’t just happen to be fast paced; this fast pace is valued as integral to “productivity.” Because speed is valued by most users of city spaces, the pace of their place ballets is maximized. As the pace of a space increases, a larger number of people can’t keep up, and more people end up disabled by their material context. Capitalist ideology thus produces disability, as well as a built-in lack of interest in accommodating this kind of disability.

There are ways in which we could remake spaces to accommodate a wider range of paces, without directly altering people’s “normal” pace. To give one example, on university campuses, classes are generally scheduled ten minutes apart, on the assumption that ten minutes is how long it takes a “normal” student to hurry across campus. Notice that hurrying is taken without question as the way that an able-bodied student should move through campus space. This scheduling directly shuts slower-paced students out of many classes. Increasing the time between classes to twenty minutes, even if this is more than most people strictly speaking need, would directly reduce disability on campus and accommodate more students.

While some spaces can be re-paced, it seems to me impossible that all spaces can be designed to accommodate all bodies and all paces. Some spaces will be fast-paced by their essential nature: the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, in virtue of its function, it’s material structure, and its entrenched practices, will always be an extremely fast-paced space. But the goal of creating inclusive cities is not to create cities in which everyone is at home in and able to use all spaces, despite starry-eyed myths of universal design. It’s ok that cities are to some extent territorialized, and that some spaces have insiders and outsiders; having our own territory within our city is an essential part of living well within it. The Black men’s barbershop down the street from me is not a space for me; my boxing gym is not a space for wheelchair users, and that’s ok. That some spaces must remain fast-paced is not itself an injustice.

Supporting every city dweller’s right to be included in their city means making sure as best we can that everyone has meaningful access to a wide range of spaces, sufficient to support a flourishing urban life. We need to recognize that right now, access to spaces is not just differentiated, but unequal, in the sense that privileged city dwellers have more and better access to a wider range of spaces, and more agency within those spaces. In particular, people with fast-based, non-disabled, normatively shaped and sized bodies have privileged access to most city spaces. We must think about who spaces are built by and for, and who they have come to accommodate as they have developed place ballets over time. We need to build cities that allow everyone access to a variety of spaces that support their well-being and agency.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers