Oxford University Press's Blog, page 90

November 30, 2021

COVID-19 and mental health: where do we go from here? [podcast]

The effects of COVID-19 reach far beyond mortality, triggering widespread economic and sociopolitical consequences. It is unsurprising to learn, after everything that has transpired in the past two years, that COVID-19 has also had a detrimental effect on our mental health. Recent studies in the US and UK have shown a huge increase in the number of adults who have experienced symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder over pre-pandemic figures.

On today’s episode, we spoke with Professor Seamas Donnelly, editor of QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, and Dr John C. Markowitz, author of In the Aftermath of the Pandemic: Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Anxiety, Depression, and PTSD, to explore the factors behind these figures, COVID-19’s impact on our mental health, and where we go from here.

Check out Episode 67 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · COVID-19 and Mental Health: Where do we go from here? – Episode 67 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingTo learn more about COVID-19 and mental health, check out John C. Markowitz’s book In the Aftermath of the Pandemic, which addresses specific clinical issues that arise in the context of the pandemic, and provides specialized tools for handling them. Dr Markowitz is also the author of other books, including Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and The Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy.

QJM: An International Journal of Medicine has published several articles related to COVID-19 and mental health, including:

“The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population”“Dealing with Community Mental Health post the Fukushima disaster: lessons learnt for the COVID-19 pandemic”“The importance of studying the increase in suicides and gender differences during the COVID-19 pandemic”The journal also published articles related to healthcare professionals (“The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals”) and those living with long COVID (“Post-COVID syndrome and suicide risk”).

Additionally, you can find more resources on Oxford University Press’s Mental Health and COVID-19 content hub. The hub features journal articles on mental distress among US adults during the pandemic, the psychological impact of lockdowns, the ramifications of the pandemic on Medicare in the US, and much more.

You can also explore a chapter from Oxford Clinical Psychology on “Helping People Cope with Disasters” and a chapter from the Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention on “Evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Featured image: Photo by Heike Trautmann on Unsplash.

November 29, 2021

Homi K. Bhabha on V.S. Naipaul: in conversation with William Ghosh

Literature, we’re told, is the immortality of speech, but in fact reputations fade quickly. The work of V.S. Naipaul once drew bombastic statements from large names: “to understand the modern state, we are often told we must read V. S. Naipaul” (Pico Iyer); his “writings are a sort of baseline for thinking about certain things” (Barack Obama); the modern literary public sphere in India “really began with Naipaul” (Amitav Ghosh); “the sweep of Naipaul’s imagination [is] without equal today” (Elizabeth Hardwick); or, from a different perspective, “the most immoral move has been Naipaul’s…” (Edward Said). But today, undergraduates arriving at university are unlikely even to have heard of him. “His equals are Joseph Conrad, Toni Morrison, and John Coetzee,” Homi K. Bhabha writes in the proposal for his new book-in-progress, V.S. Naipaul and the State of Literature. But “V.S. Naipaul’s literary legacy is in danger of being lost somewhere between elegiac celebration and fierce controversy.”

Bhabha spoke to me across the Atlantic, from his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. My own book on Naipaul, a study of his entanglements with twentieth-century Caribbean writers, artists, and intellectuals, had recently been published, and—a perpetual student of Naipaul’s work—Bhabha had been reading it. “Very thoughtful, beautifully written, very careful,” he said, with smiling understatement, acknowledging that speaking on the subject of V.S. Naipaul can sometimes cause anger and offense. So why do we continue to read, study, and teach him? Why does Naipaul matter today?

A foundational figure in postcolonial theory, Bhabha first read Naipaul as a student in what was then Bombay. He wrote a DPhil on Naipaul’s work at Oxford in the early ‘80s. It started with recognition, he tells me. “When I read Naipaul—particularly the early works—I encounter a vernacularized, provincialized English. That’s the way we often spoke in Bombay. It legitimized that form of writing, and the thinking that goes with it.” With time and careful study, moving onto the denser works of Naipaul’s middle period, he began to see more. “For me,” he says, “Naipaul was a translational figure, moving between the most classical formulations of the English literary canon, whilst at the same time opening windows in the House of Fiction onto the experience of the downtrodden, the marginalized, those whose ambitions so far outstripped their ability to realize them. And yet who held onto them!”

What Bhabha’s essays taught me to see, as a student, was how Naipaul allowed these “translations” of dialogue, setting, milieu, to distort the literary forms he was using. Naipaul’s characters were educated to respect English, yet its grammar became new in their mouths; his narrators have an exaggerated respect for the classical forms of English prose, yet trying to replicate them in colonial settings, they end up refracting them. A House for Mr Biswas, for example, “had the capaciousness of a great bildungsroman, and yet everything about it subverted the traditions of the bildungsroman.” One word Bhabha returns to is “strangeness”: “that enormously educative awkwardness, which was not an awkwardness of style—the work is polished and elegant and brilliant—but rather of concepts. The books are montages of generic fragments, but the sum of the parts provocatively don’t add up to the whole.”

Today, Bhabha’s ideas percolate far beyond literary scholarship. His 1994 book The Location of Culture quickly became a key text for students of postcolonial history, culture, and politics (one bot on the publisher’s website claims 59,351 citations). It is striking how many of the key terms from Bhabha’s later work—ambivalence, vernacular cosmopolitanism—crop up again and again in his discussion of Naipaul. Did this early and diligent study of Naipaul shape his later concepts? “Absolutely,” he says. “Naipaul was the matrix of some of my earliest ideas.” Rebarbative, patrician, wilfully provocative, Naipaul had by this point become a favourite witness for imperial apologists in Britain and American. Bhabha’s interest in Naipaul did nothing to dispel suspicions among some left-wing thinkers that postcolonial theory was not sufficiently politically radical: Brahminical in its interests and expressions, and focused on language and culture at the expense of material inequality. Where Naipaul was concerned, Bhabha admits, “I wasn’t betting on the horse that most people thought would be an important breakthrough for anti-colonial politics. Naipaul had many views that weren’t compatible with anti-colonial thinking. As you know, I didn’t agree with him about many things. Much of my work critiques it. But I felt that the problems Naipaul threw up needed to be explored.”

One problem, I speculate, is that “anticolonial” and “postcolonial” aren’t really synonyms, and postcolonial theory often addresses a specific cultural question. That is, how do we talk about the differential aspects, the strangeness, the points of resistance and awkwardness found in the manners, writings, and ideas of people from the formerly colonised world who were in many ways quite assimilated? “I completely agree with you,” Bhabha says, “and that is the Naipaul predicament, and the predicament of many postcolonial writers. At the time, people were trying to fix people as being either anti-colonial or collaborators. So Naipaul had to be a collaborator. But it was obviously more complicated than that. What Naipaul requires you to do is to live with ambivalence, like Mr Biswas or Ralph Singh, his characters live with ambivalence. They have to tolerate ambivalence as a condition of survival. But in the end, it affords creativity.”

Naipaul has passed away now, but his subjects are still with us. Bhabha describes finding himself in New York with a driver listening to Hindi bhajans (devotional songs). Talking to him, Bhabha realised that the man was not Indian but Trinidadian. “I asked him if he enjoyed the bhajans. He said, ‘Yes, but I don’t understand them. Do you? Could you explain it to me?’’. “I was raised in India to think that people who grew up between languages, between cultures, were really second-class citizens. Even the elites would listen to compilations mostly, a little Wagner, a little Strauss and so on. But what we aspired to was the virtuosity of knowing Wagner entirely, all of it. That’s why Naipaul was important. He said, ‘The mosaic, the compilation, the half-known, the amalgam, this has value in itself. This will be my subject.’ So the taxi driver in New York was quintessentially Naipaulian.”

At the heart of Bhabha’s interest in Naipaul is a vision of cosmopolitanism he derives from Naipaul’s downtrodden characters who, he says “aspire to worldly relations found in the midst of the metropolitan traffic of ideas and images while keeping their eyes trained on an horizon of hope elsewhere. Sometimes the traffic bypasses the island, but the creative imagination refuses to renounce the freedom of writing from elsewhere while never ceasing to recreate the landscape of home.” This is not the cosmopolitanism of the rich, he explains, in which mobile citizens move from one nation to another, mastering the language and national literatures. Rather, it is a non-elite, “vernacular” cosmopolitanism of the migrant, the displaced, the diasporic, living in between languages and cultural traditions, and insecurely—even contradictorily—attached to different visions of culture. “This,” Bhabha says, “is why Naipaul is important today, because he is ambivalent, asymmetric, strange. When everything seems to be going in the other direction.”

Feature image: Trinidad – Port of Spain (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.)

November 27, 2021

Green libraries tackling environmental challenges: University College Cork

In the 21st century, we are faced with news about the global environmental crisis on a regular basis. Rising temperatures, melting polar ice caps, loss of wild life, and deforestation are but a few examples of the coverage we are all too accustomed to. When faced with something with a global all-encompassing impact, it is sometimes difficult not to feel helpless and struggle to see the value individual contributions can have on fighting these challenges.

So, what might libraries do to help reduce the carbon footprint and what could the impact of such efforts be?

We spoke to Martin O’Connor, the Communications Coordinator at University College Cork’s (UCC) Library & Information Services, to find out how UCC Library chose to tackle the challenge and make their library greener with their “Love our Library” campaign.

What is “Love our Library” and what inspired the library to launch it?As part of a national effort to improve energy efficiency across Ireland by 2020, which has a public sector goal of 33% energy reduction, in 2016 UCC conducted an extensive review of the energy usage across its campus. The discoveries from this review led to the initiation of the “Love our Library” campaign by the library staff at the university.

While the campaign initially started as an energy saving campaign, the newly founded Green Library Team quickly found out that focusing on energy alone would not be enough to tackle all the environmental challenges they were hoping to address. This led to the expansion of the campaign in an effort to further decrease the carbon footprint generated by the library.

O’Connor, speaking to us on behalf of the Green Library Team UCC, shared the team’s revised campaign goals: to reduce energy consumption, increase recycling rates, reduce waste generation, increase the use of water fountains, improve staff and student behaviour, and increase both staff and student engagement with these sustainability projects.

What has been done to meet the campaign goals?Having started as an energy saving campaign, the initial focus was on just that. “We rebalanced air ventilation and heating systems to improve the office and reading room environmental conditions,” O’Connor explains, which was one of the main ways in which the library began to reduce its energy consumption alongside efforts like turning off the lights in low usage areas of the library during the summer months. In 2018 and with the money saved from reducing the annual energy consumption, the library was able to install a Living Wall. This wall of indoor plants not only acts as a natural air purifying system and toxin eliminator but also helps reduce odours, enhances concentration and memory and reduces stress and fatigue.

To tackle waste generation and increase recycling rates, UCC Library created binless offices, installed compost bins in the library, and centralised waste collection points while also campaigning to encourage students to use these new points. However, they did not stop there. O’Connor also tells us some of the more creative actions taken in support of these objectives. These include ”Ditch the Disposable” an initiative under which library users are only permitted to bring in drinks in reusable travel mugs, and the installation of Gum Drops which allow the UCC community to recycle their chewing gum. The library even utilised charitable actions in their recycling efforts. “We recycled computers into the local community via local schools and to developing countries via the charity Camera,” O’Connor told us.

Finally, to increase the usage of the library’s water fountains, the library has also upgraded their water fountains and included campaign posters talking about the issues with single-use plastics at the water-filling stations. As a green alternative, visitors to Boole Library can purchase reusable water bottles made from sugar cane which are sold at the library desk.

What has the impact of the campaign been?Having been positively received across the university, with both student and staff body involved, it comes as no surprise that the “Love our Library” campaign has been a massive success. Since 2016, the library has saved approximately 615,000 kWh of energy with an annual reduction of 2% in their electrical consumption which has translated into over 65,000 euros in energy savings. Offering us a couple of fun factoids, O’Connor explains how this is “enough energy to power a light bulb for 2,300 years or travel around the world 66 times in an electric car.” As an equally exciting result, recycling has gone up an impressive 700%. The number includes specifics such as saving over 10,000 plastic bags each year. “With the moneys saved we were able to: invest in an air curtain, which will contribute to energy savings going forward, our Living Wall, and an E-Car as well as two E-Bikes,” O’Connor says.

Boole library has received both national and global recognition for “Love Our Library”, including winning Best Library Team at Irish Education Awards in 2018, “Best Public Sector Category” in Cork Environmental Awards Ceremony December in 2017, being the runner up for the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) Green Library Awards in 2019, shortlisted for Packman Awards – Innovation Waste Management 2018, and shortlisted for Sustainability Team of the Year at Irish Green Awards 2019.

What advice would you give to other libraries hoping to reduce their carbon footprint?“The first thing we would say is ‘go for it’. Your library can make a difference!” O’Connor starts. “Bring together a dedicated team with an interest in the environment and engage with the student population and your user base. Get them on board as soon as possible,” he continues. For any library interested in sustainability projects of their own, getting the support of all the stakeholders right from the start is absolutely vital. If the library is part of an institution with its own sustainability team, O’Connor also encourages library staff to go them for advice and assistance. An important point is also made about publicising any savings a library makes following any green campaigns of their own. These types of figures are powerful and the most concrete way of demonstrating the fruits of your labour.

To finish off our discussion, O’Connor wants to offer some words of reassurance to any libraries interested in similar projects of their own, “Learn from those who have gone before you. In the spirit of sustainability, borrow ideas from others. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel.”

November 26, 2021

How research abstracts succeed and fail

The abstract of a research article has a simple remit: to faithfully summarize the reported research. After the title, it’s the most read section of the article. It’s freely available on the publisher’s website and in online databases. Crucially, it makes the case to the reader for reading the article in full.

Alas, not all abstracts succeed.

Some take the notion of abstraction to extremes. This example is from a physics article:

Unitarity and geometrical effects are discussed for photon-photon scattering.

It has just ten words. Fortunately, most abstracts say rather more, though it’s possible to say too much. The next example, from a geology article, has over 370 words. It starts:

Diagenesis of the Holocene-Pleistocene volcanogenic sediments of the Mexican Basin produced, in strata of gravel and sand, 1H2O- and 2H2O-smectite, kaolinite, R3-2H2O-smectite (0.75)-kaolinite, R1-2H2O-smectite (0.75)-kaolinite, R3-kaolinite (0.75)-2H2O-smectite and R1-1H2O-smectite (0.75)-kaolinite. Smectite platelets…

It continues in a similar vein for a further 350 words, accumulating more and more detail. The reason for the work is hinted at, but only becomes clear in the full article, at which point it’s too late.

Some abstracts introduce citations to previous research to provide background, contrary to the expectation that abstractions stand alone. In practice, citations can block the reader’s progress, as in this example from a remote-sensing article:

The purpose of this paper is to extend the stationary stochastic model defined in [1] to a time evolving sea state and platform motion.

The reference pointed to by “[1]” isn’t attached to the abstract, and the source article is obviously elsewhere. Yet without it, the rest of the text is difficult to appreciate. Similar problems can occur with abbreviations explained only in the article.

Some abstracts confuse their remit by summarizing the paper rather than its content. The shift to meta-reporting can lead to uninformative boiler-plate text. This example is from a medical education article:

Implications of these results are discussed.

It’s uninformative because readers already know that most research articles contain a discussion section where, by definition, results and their implications are discussed.

Some abstracts expand their remit to include personal research plans. This example is from a clinical article:

We plan to investigate why general practitioners are not complying with the pathway.

It’s common to find research aspirations in internal reports and in research grant applications, where they have a specific function. But published in an abstract, they can present a reader working in the same area with a difficult choice.

Some abstracts expand their remit even further with a self-evaluation of the research. This example is from a finance article:

We believe this study will benefit academics, regulators, policymakers and investors.

The problem is that the reader may not see these pronouncements as truly impartial, with the result that the authority of the article is weakened, not strengthened.

Abstracts can of course fail in many other ways, for example, omitting caveats, adding new information, exaggerating certainty, or providing no more than an advertisement, a piece of puffery.

How to write a successful abstractIn the light of all this, what should go into a successful abstract? Some clinical journals settle the matter by imposing a structured format. But most journal and conference proceedings don’t and may offer little or no detailed guidance to the author, who may be left confused about what’s needed.

One starting point is to think of the abstract not as a condensed version of the paper that preserves the original structure and proportions, but as a mini- or micro-paper in its own right, with certain basic elements:

the context or scope of the workthe research question or other reason for the work, if relevantthe approach or methodsa key result or twoa conclusion, if appropriate, or other implications of the work.Naturally the weight given to each element depends on the research—whether it’s experimental, observational, or theoretical, and whether the expected audience is general or specialized. How much to write about each element is then a balance between including detail and retaining the reader’s interest.

Within those constraints, it’s important to identify any critical assumptions, non-standard methods, and limitations on the findings so that the scope and potential application of the research is clear. The reader shouldn’t discover on reading the article that the abstract was misleading.

Here’s an example of a well-written abstract from a neuroscience article:

An unresolved question in neuroscience and psychology is how the brain monitors performance to regulate behavior. It has been proposed that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), on the medial surface of the frontal lobe, contributes to performance monitoring by detecting errors. In this study, event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging was used to examine ACC function. Results confirm that this region shows activity during erroneous responses. However, activity was also observed in the same region during correct responses under conditions of increased response competition. This suggests that the ACC detects conditions under which errors are likely to occur rather than errors themselves.

From C. S. Carter et al., Science 1998, 280, 747-749. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

Successive sentences describe the context, the reason for the work, the methods, some results, and an implication. According to Elsevier’s Scopus database, the article has been cited over 2,500 times.

Encapsulating a body of research so effectively usually takes repeated rewriting. The timing, though, can be a challenge, since the abstract is often prepared last, when the main sections of the paper have found a settled form. It then risks being rushed while material is assembled for submission for publication.

Despite these pressures, the abstract needs as much attention as any other section of the paper. After all, if it doesn’t do its job, the reader may turn to other abstracts that do. And the published article may languish unretrieved and unseen, waiting in vain for the recognition it deserves.

November 25, 2021

Mapping international law

International law is the discipline that covers legal issues that are of concern to more than one state. The international society that we have today is, first and foremost, a society of individual nation states. It is this understanding that helps explain the purpose of international law, because it is only when an issue arises that involve the interests of more than one sovereign state that international law even becomes relevant.

The map below highlights some fascinating examples of international law in action; examples across the globe examining how the law can, or cannot, be enforced across sovereign states. You’ll find brief insights into maritime law and state violations involving kidnappings and poison, to name a few. Click on the links to listen to a longer podcast on the topic from author Anders Henriksen.

November 24, 2021

From Halloween to Thanksgiving

In the continental United States, Thanksgiving is celebrated on the fourth Thursday of November. Before this date, some newspaper usually sends me questions about the origin of turkey, because turkey is the most conspicuous ornament of the traditional Thanksgiving dinner. But, for a change, I’ll deviate from this practice and turn to another subject. Both thank and give deserve our attention! And it is those two outwardly unexciting words that I’ll offer today as part of our etymological feast. The verb give is harder, and it may be more practical to begin with it.

Some of our readers may be surprised to learn how much trouble give has caused word historians. Only one thing is clear about it: though give is a Common Germanic verb, from a broader, that is, Indo-European, perspective it is an innovation. The ancient Indo-European root has been preserved in Greek, Latin, Slavic, and elsewhere, but not in Germanic. The Latin for I give is do, which we recognize in the English verb do-nate. Hence the formula do ut des “I give, so that you may give (back).” Donatus (that is, “a gift from God”) and Donatello are well-known names; they derive from the past participle of Latin do, dedi, datum, dare.

Since the earliest days, gifts presupposed a return gesture (hence the phrase gift exchange), and the idea of exchange that underlies giving resulted in an outwardly surprising confusion of “give” and “take” in the languages of the world. For example, Old Irish gaibim means “I take”; yet the root vowels ai in Irish and e in Germanic geban are incompatible, and despite the endorsement of this etymology by many good scholars, it remains unclear whether the two words are related. However, the ancient custom of exchange is a fact.

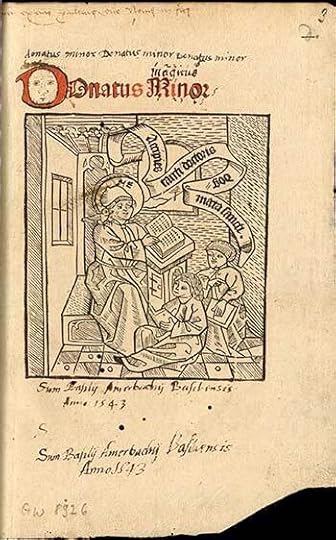

This is a picture of possibly the first edition of Ars Minor by Donatus, an immensely popular grammar by a Roman scholar.

This is a picture of possibly the first edition of Ars Minor by Donatus, an immensely popular grammar by a Roman scholar.(Donatus, Aelius: [Ars minor]. [Basel] : [Michael Furter], [1496?]. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, DC V 13:3, https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-16603 / Public Domain Mark)

The Old English form of give was g(i)efan, pronounced y(i)evan. Its Scandinavian cognate was geba, and the Modern English form with hard g- is the result of borrowing. But for the Viking victories in the Middle Ages, give (as well as get) would have begun with the sound we today have in yield and yearn, both of which withstood the pressure of Old Danish. If the ancient form geban (compare Modern German geben) was an innovation, how did it arise? Words, unless they are sound-imitative (like oink-oink and thump, among many others) or symbolic (like probably the verb spit), are produced from the requisite stock-in trade.

Two more or less similar look-alikes suggest themselves as the material from which give (that is, geban) was formed. One is the verb have (the earliest recorded Germanic form—so in Gothic—is haban). The association between “give” and “have” hardly needs proof. According to the traditional point of view, Indo-European had the consonants bh, dh, and gh. From the third of them, g-, as in geben, and h and haban, could have evolved. I am sorry for repeating the same dictum again and again, but experience shows that one obscure word cannot shed light on another word of unknown origin, and as regards etymology, Germanic haban is indeed obscure. It is a seemingly illegitimate twin of Latin habeo (the same meaning). Germanic h (as in haban) should correspond to non-Germanic k- (as between Engl. head versus Latin caput “head”; compare Engl. capital, decapitate, and so forth), not h. Many pages have been devoted to the origin of the Germanic verb. Could it be taken over from Latin? Of course, it could, but why should people have borrowed such a basic word as have? Since the original form of have remains a matter of debate, we cannot decide whether give was derived from it.

The other close neighbor of Germanic geban is Latin capio “to catch” (compare Engl. capture). The correspondence is again imperfect. This time, we need Germanic h-: see the caput ~ head pair above. But words people coin to refer to getting hold of objects are indeed expressive. The Swiss linguist Wilhelm Oehl, to whose half-forgotten works I keep referring with some regularity, devoted an illuminating essay to them. People catch objects and say hop, hap, gop, gap, and the like all over the world. I may cite Russian khapat’ “to seize” and gop!, a shout accompanying a successful jump. Oehl offered long lists of similar words. These exclamations do not obey regular sound correspondences, cross language barriers, and finally become fully respectable items in our vocabulary.

Hop, gop!

Hop, gop!(Photo by Chris Chow on Unsplash)

This is all true, but the relation between give and have is at best a clever hypothesis. Those who will take the trouble to look up give in good etymological dictionaries will find a list of secure cognates and a sad admission to the effect that the ultimate answer evades us. I can only repeat: “Do ut des!” and, if you need more Latin, carpe diem! “seize the day,” that is, enjoy the glorious present. You may not think that the present moment is glorious—enjoy it all the same.

We can now go over to thank. It is related to think. The same picture emerges from other Germanic languages. For example, German has danken “to thank” and denken “to think.” It should be remembered that the original root vowel of think was a. The oldest Germanic verb was pronounced thank-j-an (j has the value of Engl. y in yes). The suffix j caused umlaut, which changed the root vowel a to e. The Dutch and German for think is still denken, that is, from the historical point of view it is dänken. And thank has always been thank-! English has widened the distance between the two words even more, because the root vowel e became i before n: hence think.

Is he harboring only kind thoughts?

Is he harboring only kind thoughts?(“Le penseur de la Porte de l’Enfer (musée Rodin)” by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, via Wikimedia Commons)

If, while dealing with give, we were in trouble with phonetics (the consonants refused to math), here we are puzzled by the development of meaning. Think and thank had the same root, namely thank-, but how did the meaning develop? The tie between thinking and thanking goes back to the beginning of recorded time. In Old English, the noun thank meant “thought” and (specifically) “kindly thought.” The Old Icelandic senses are even more revealing: “thought” and “joy.” Apparently, think, in addition to the expected senses (“conceive, consider”), suggested the idea of remembering and remembering things well or kindly. Such secondary overtones must have been primary. To think “cogitate” is an extremely abstract concept. It probably developed from a more concrete nucleus, such as “remember; consider things in their true light; appreciate the fact of knowing an important fact.” In an oral culture, such associations must have sprung up in a natural way. Only one step separated kind thoughts from gratitude.

This conclusion seems to be a proper way for an etymologist to celebrate Thanksgiving. Catch and enjoy the day of rest and think kindly of the world, even though it does not always treat you kindly.

Featured image by Viktor Talashuk via Unsplash

The society of Holocaust victims: what was life inside a Nazi camp like?

What was society like in the Nazi concentration camps and ghettos? Can we even speak of “society” in this context given the suffering of uprooted and imprisoned people, almost all of whom were eventually murdered? There is a widespread notion that the camps destroyed people and atomized society. Hannah Arendt, for example, argued that the totalitarian regime stripped detainees of all their characteristics of humanity until they were no longer moral persons.

By contrast, The Last Ghetto offers a new, systematic exploration of social relations in a Nazi camp. Using the ghetto of Theresienstadt (or Terezín in Czech) as a case study, my investigation shows how people imprisoned in this central European ghetto made sense of a terrifying new place in which they found themselves deciding with whom to share food and accommodation, or whom to join on transport to the East, connecting with friends old and new, and even falling in love. I interpret these moments in the context of everyday life in the camp.

To mark the 80th anniversary of the first transport to Theresienstadt on 24 November 1941, it is worth having a closer look.

Pavel Fischl was a young Czech poet who arrived to Theresienstadt with the second transport of young men deployed to set up the transit ghetto, known as the “construction detail.” He described how people got used to their frightening new surroundings:

“Not for nothing is it said that one even gets used to the gallows. We have all gotten used to the noise of steps in the barracks’ hallways. We have already gotten used to those four dark walls surrounding each barracks. We are used to stand in long lines, at 7am, at noon, and again at 7pm, holding a bowl to receive a bit of heated water tasting of salt or coffee, or to get few potatoes. We are wont to sleep without beds, live without radio, record player, cinema, theatre, and the usual worries of average people. [W]e have gotten accustomed to see people die in their own dirt, to see the sick in filth and disgust […] we are habituated to wear one shirt one week long; well, one gets used to everything.”

For Central and Western European Jews sent to Theresienstadt by the SS, their imprisonment was a shock. Most of them had come from the middle and upper-middle class. The crowded accommodation, meagre food, dirt, high mortality that particularly addressed the elderly, and fear of transports to the East had an equally chaotic and terrifying effect. Some of the newcomers met old friends who helped them navigate this seeming netherworld; others were curious and charmed people to get by. Within weeks, the new prisoners started fitting in. The Jewish self-administration assigned them accommodation, food rations, and a job (there was a universal labor duty). Often, the employment was not one that the person desired, yet with their growing knowledge of Theresienstadt, some individuals acquired the connections and persuasive skills they needed to be hired elsewhere. Fear of the Germans was widespread and people heard about executions in the early months. At the same time, they quickly realized that the SS were the controllers, not the managers, of the ghetto. This job the Germans forced on the Jewish functionaries. Weeks would pass without a detainee even seeing a Nazi.

Settling in was particularly hard for older prisoners. They received the worst accommodation and food rations, and this detrimental treatment was reflected in high death rates. They nevertheless fought to stay alive and embraced the ghetto with curiosity rather than horror. Some seniors described their lodgings as “The Lower Depths”, a reference to Gorky’s play of the same name. They shared stories about the places they came from, about their former positions of power, which they sometimes exaggerated, and at other times they laughed. A famous joke went: “A dachshund in Terezín says: back in the day I was a St Bernard in Prague!”

The society of the Theresienstadt ghetto reflected and engendered class differences. Stratification was expressed not only in access to material resources (food, accommodation, and protection from transports to the East), but also in status and prestige. For instance, bakers, butchers, and cooks were considered the best positions, not least because of their access to food (they received extra rations to discourage theft). In addition, among those assigned to these professions were the 1,342 men who had arrived on the two construction detail transports to set up the first barracks for the thousands who arrived after them and were thus considered particularly deserving. The SS promised these men protection from further transports, which was extended to their immediate families. Unsurprisingly, these young men became much sought-after for marriageable women in the camp and their privileges elevated them to the position of a social elite.

When the young Arnošt Reiser visited his attractive friend Lilly, he found her living in her own room with her boyfriend, a member of the construction detail, who was smoking a cigarette. Smoking was prohibited in Theresienstadt, and the SS imposed draconic punishments if anyone was caught with cigarettes. They were smuggled in by Czech gendarmes and sold for about 8 Reichsmark (RM) apiece. A loaf of bread was sold for about 40 RM on the ghetto black market. A cigarette was an expensive treat.

To our eyes, social differences in Theresienstadt may appear minimal—whether one slept in a crowded room or had a tiny room of their own. But if we want to understand the experience of the ghetto prisoners, we need to discern their choices and take them seriously, whether it was a decision over whom to share dinner with or join on a transport to the East. This was the agency that Holocaust victims had, and it was immensely important to them.

Camp society during the Holocaust was one of the many versions of what human society can be. It was neither just nor equal (despite often being remembered and depicted in historiography as such). Nor should analyzing social difference within the camp gloss over the fact that it was the German state that did the work of organizing and implementing genocide. The Jews in Terezín behaved like people always do: they created distinctions and made friends, fought for resources and shared them with their loved ones. The ways in which they expressed their social ties was sometimes different to our “normal world.” Interrogating the operation of class in the ghetto gives complexity to a place usually narrated in sentimental clichés. Even more importantly, it brings agency and individuality back to the people of whom we otherwise only know that they were slaughtered.

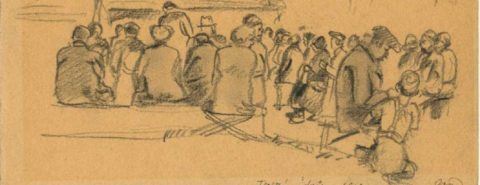

Feature image is Norbert Troller sketching of Terezin Yard 82.295, Courtesy of the Leo Bacek Institute

November 20, 2021

Voicing 1960s femininity: not just a “girl singer” [playlist]

“The disc charts cannot stand many girls, no matter how gorgeous they look,” claimed Beatles manager Brian Epstein in A Cellarful of Noise, his memoir of the 1960s. He was explaining why he’d only ever represented one female performer—Cilla Black. His justification falls back on the then-conventional wisdom that girl singers were an anomaly, were each other’s competitors, and that there wasn’t an audience for their work. He was wrong, but his comments are indicative of the assumptions of music industry gatekeepers—assumptions that created roadblocks for women and girls.

For those who did pursue pop music careers, “girl singer” could be a tough label to bear. For pop singers who start their careers young it could feel like a trap; a categorization that made it hard to experiment stylistically as they grew older and their musical tastes changed. It could be used dismissively, to imply that a singer was naive and lacked the know-how to navigate the music industry on her own, or to dismiss her musical skill. This dismissiveness undermines the impact of girl singers’ voices. Their voices sounded out different ways of being and new ways of imagining the world and shaped what it meant to be a modern young woman. Sandie Shaw, Marianne Faithfull, Millie Small, Dusty Springfield, Lulu, Cilla Black, PP Arnold, and other singers in 1960s Britain, often confounded assumptions about what it meant to have a controlled, respectable voice.

This playlist lets us hear how the singers featured in Freedom Girls navigated the often-fraught territory that came with being a “girl singer.” Sandie Shaw’s path took her from Burt Bacharach tunes to surprising rock covers to becoming an alt-rock darling who recorded with the Smiths. Cilla Black went from being the coat check girl at the Cavern Club who made her mark with Merseybeat to the stage of the London Palladium—but she always made her Liverpool connection clear. In songs like “Liverpool Lullaby,” which she sings with an exaggerated Liverpool accent, she vocalizes her link to her home city, just as fellow Liverpool natives the Vernons Girls had done a few years earlier with “You Know What I Mean.”

Lulu on Dutch TV-programme Fanclub, 11 Dec. 1965.

Lulu on Dutch TV-programme Fanclub, 11 Dec. 1965.Photo by R. Frings, CC BY-SA 3.0 NL via Wikimedia Commons

Millie Small, the chart-topping ska singer who came to England from Jamaica, had a voice that spoke to changing attitudes towards race. In Jamaica, she had been a local star as half of the duo Roy and Millie; in England she became an international sensation with “My Boy Lollipop;” and towards the end of the 1960s, she released the anti-racist anthem “Enoch Power.” American singers like Madeline Bell, Doris Troy, and Martha Reeves helped soul proliferate in the UK and singers like Dusty Springfield learned the sounds of soul from their voices. Lulu, too, sang with a voice informed by soul. Her career began when she was only 14, and she found it particularly difficult to be taken seriously in the rock world due to her “girl singer” reputation.

Marianne Faithfull was framed as an ingenue at the outset of her career but in the aftermath of sexist backlash her voice and musical style were utterly transformed. Her recent work, particularly songs like “Born to Live,” often looks back to the 1960s with a combination of nostalgia and critique. PP Arnold, too, often harkens back to her 1960s days, when she provided crucial backup vocals on tracks like the Small Faces’ “Tin Soldier” and recorded the first version of “The First Cut is the Deepest.” Released for the first time in 2018, her album The Turning Tide, which was recorded in the late 1960s, re-imagines some of the iconic rock songs of the period.

Finally, this playlist closes with three songs inspired by the singers who gave voice to 1960s girlhood. Candie Payne’s “One More Chance” hearkens back to the epic pop ballads of Cilla Black and Sandie Shaw. V.V. Brown’s “Crying Blood” evokes 1960s soul and rhythm and blues, and Shelby Lynne’s version of “I Don’t Want to Hear it Anymore,” from her album of Dusty Springfield covers, is a tribute to Springfield’s voice and legacy.

Feature image by Ray on Unsplash

November 19, 2021

20 people you didn’t know were Prohibitionists

Speakeasies, rum runners, and backwoods fundamentalists railing about the ills of strong drink are just one small part of the global story of prohibition. The full story of prohibition—one you’ve probably never been told—is perhaps one of the most broad-based and successful transnational social movements of the modern era. The call for temperance motivated and aligned activists within progressive, social justice, labor rights, women’s rights, and indigenous rights movements advocating for communal self-protection against the corrupt and predatory “liquor machine” that had become rich off the misery and addictions of the poor around the world.

From the slums of South Asia, to the beerhalls of Central Europe, to the Native American reservations of the United States, discover 20 key figures from history that you didn’t know were prohibitionists.

[See image gallery at blog.oup.com]

November 17, 2021

The sky’s the limit

Last week’s post was devoted to the word earth. Time to move on, as they say after a serious but unresolved crisis (not the best Wellerism in the world). We can progress to Cloud Nine or seventh heaven, or wherever, but in all cases, we will notice that English (uncharacteristically) has two, if not even three, words for the sphere above us: sky, heaven, and firmament. The case of English is not unique but rare: usually a single word suffices. Sky and heaven can be used in the plural (for heavens’ sake; praise to the skies, and in more mundane contexts), while earth is just earth. We stand on the ground with both feet, and even though we distinguish between earth, land, ground, and soil, each word has its sphere of application and refers to something solid.

But what is the sky, that infinite expanse over us and the habitat of the gods? In the past, people had the same trouble defining the home of the sun, the moon, and the stars as we do. The medieval Scandinavians distinguished at least three skies. In the highest of them, the goat Heiðrún (ð = th in English this) lived, devoured the leaves of the world tree, thereby accelerating the end of the world, but produced a never-ending stream of mead for the gods and the warriors of Valhalla. Firmament means “the vault of heaven.” Apparently, it is firm. In ancient astronomy, the firmament was the eighth sphere, containing the fixed stars that surrounded the seven spheres of the planets. The sky is indeed the limit. The plural use of heaven and sky goes back to the oldest Hebrew tradition. By way of postscript, I may add that in the ancient mythology of the Indo-Europeans, the sky was represented as a male impregnating the earth (see the end of the previous post). With great regularity, the words for “earth” are feminine and the oldest words for “heaven” masculine. Latin caelum (it will reemerge below), which is neuter, has not preserved the original grammatical gender.

Heaving and supporting the heavens

Heaving and supporting the heavens(Atlas and the Hesperides by John Singer Sargent, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sky and firmament appeared in Middle English at approximately the same time (in the thirteenth century). Both are borrowings: the first from Old Norse and the second from Old French, the two languages that shaped the vocabulary of English in the most decisive way. As could be expected, the Scandinavian loan became a homey word, while the French one belongs to a more solemn register. Though the import from Old Norse meant “cloud,” rather than “sky,” ský drove out Old English (native) scēo. Thus, from a historical point of view, the word refers to a cloudy sky. The meaning of the ancient root has not been ascertained, and I will pass it by but note that a few related nouns in Germanic mean “mirror.” How are “mirror” and “cloud” connected? Presumably, the image in a mirror was understood as a shadow cast by the person or object in front of it. “Cloud” and “shadow” are indeed not incompatible.

From an etymological point of view, the most interesting word of those mentioned above is heaven, going back to Old English heofon. To begin with, it sounds like the related Old Saxon noun but does not quite match Dutch hemel ~ German Himmel. The difference between the final syllables –el and –on (Old Saxon –an) can probably be explained away: they were either always different or changed, for whatever reason, in Old English and Old Saxon. Since in Gothic, the earliest Germanic language from which we have a long consecutive text (a fourth-century translation of parts of the New Testament), the word for “sky” was himins, it seems that the ancient root was hem– (in Gothic, every short e became i), rather than hef-.

The meaning of this root remains an object of debate. The earliest guess was that heaven is something that has been heaved. Indeed, in some mythologies, the sky does mean a sphere raised, but we need a clue to the root hem-. The great German language historian Friedrich Kluge suggested that the word’s root is hai– and cited Modern German hei-t-er “bright.” This was a clever move. Old English hādor (from haidor) means “serene,” and close by we find the Latin word cael-um “sky, heaven” (cf. English celestial). Contrary to the Scandinavian-English cloudy sky, the southern sky of the Romans was bright. But the root Kluge cited meant too many things. Thus, the Modern English suffix –hood (as in childhood; Old Engl. –hād) and its cognates, meant “quality,” with many ramifications, from “sex” to “rank.” It did also refer to brightness, but only among others. Also, let us not forget that we need a root sounding like hem-.

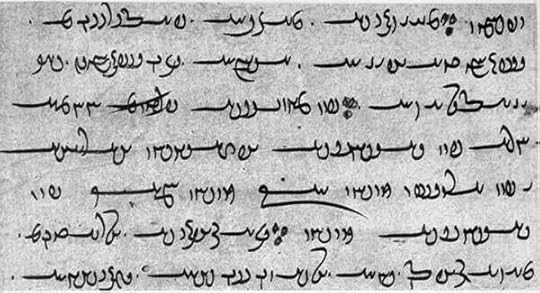

A page of the Zend Avesta

A page of the Zend Avesta(From Bodleian Library via Wikimedia Commons)

Kluge’s successors preferred to compare Himmel and heaven with words referring to “cover,” such as Old English hama “cloth; skin,” German Hem-d “shirt,” and so forth. Himmel ~ heaven emerged from this interpretation as “the cover of the world.” Old Engl. heofon-hūs ~ hūs-heofon, literally “heaven-house ~ “house-heaven” meant “the ceiling of the house.” One can find this etymology in several good dictionaries. Latin cam-ur “vaulted” (as well as nearly the same word in Greek) also corresponds to the Germanic root. (I need hardly remind our readers that k in Latin, Greek, and other non-Germanic languages corresponds to Germanic h by the First Consonant Shift, as in English heart versus Latin cor, cordis.) As regards meaning, “vaulted” and “heaven” certainly belong together.

I am now coming to the last hypothesis for today. The root of Himmel reminds us of the word hammer. Can the sky (heaven) be associated with a hammer? The most ancient hammers were made of stone. Consequently, our question should be reformulated so: “Can heaven and stone have anything in common”? In the text of the Avesta, a collection of religious texts in an old Iranian language (and it seems only there), the word asman– means both “stone” and “heaven.” The idea that in the past, the sky and stone were in some way connected in people’s minds was offered long ago (I believe, in 1913) and has both opponents and supporters. At present, supporters seem to predominate. We have already met the Old Scandinavian goat. We can now turn to the formidable god Þórr (Thor), the fearless giant-killer, but originally Thor was a (or the only) thunder god of the medieval Scandinavians. His main weapon is the hammer Mjöllnir, transliterated in English texts with one l (Mjölnir or Mjolnir).

Thor and his hammer

Thor and his hammer(Figure of god Thor, National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik, via Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps the sky was associated with thunder, and thunder made people think of a shower of stones falling from the sky (or of meteorites?). In mountainous regions, the sky god is usually associated with thunderbolts because of the terrifying echo, while in the landscapes with predominating plains, the supreme sky god more often kills his victims with lightning (as did Zeus-Jupiter).

Such is the state of the art. English has sky, heaven, and firmament. They have divided their spheres of application and coexist in peace. The sky is not always cloudy, the heavens are not necessarily made of stone, and only the firmament remains firm. It will be fair to say that the origin of heaven remains undisclosed. Yet we seem to be wandering not too far from the truth. In etymology, the goal often evades us, and movement toward it is sometimes all we can offer. The same is true of our journey heavenwards.

Feature image by Jelleke Vanooteghem on Unsplash

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers