Oxford University Press's Blog, page 91

November 16, 2021

The musical genius of Tommy Tune: “old plus old equals new”

From the beginning, Tommy Tune was pulled as if by centrifugal force toward dance and the Broadway musical. He was taking dancing lessons by the age of five, but his early ambition to be a ballet dancer was abandoned when he shot up in height during his teenage years. He later joked about his extreme height, saying, “Sometimes, instead of thinking of myself as six-foot-six, I tell myself I’m only five-foot-eighteen.”

Nevertheless, he made a smooth transition from staging backyard musicals in his native Texas to standing tall (literally) in Broadway chorus lines. His friend and early mentor, Michael Bennett, provided Tune with both his first opportunity to choreograph on Broadway and his breakthrough as a performer. When Bennett took over the direction of the struggling musical Seesaw, he recruited Tune to join the show’s choreographic team and promoted him to the role of a gay choreographer. Refreshingly, the character was not sad and lonely, nor a focus for easy laughs. It was one of musical theater’s first attempts to portray gays as more than stereotypes.

Tune’s showstopping number, “It’s Not Where You Start,” which he choreographed, served as a template for much of his later work. Throughout his career, he brought the Broadway musical forward by looking backward, drawing on well-worn show business performing styles and tropes and infusing them with contemporary energy and attitude. Here, in both his staging and performance, Tune blended the old and the new into something fresh and original.

Tune won the Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical for Seesaw, but his towering height made it difficult to translate this success into a sustained performing career on Broadway and he soon distinguished himself as an exciting new choreographer and director. The hits started adding up: The Club and Cloud 9 off-Broadway won him Obie Awards, A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the Ukraine and Nine brought him Tonys. In between, he gave Irish step dancing an athletic and homoerotic energy in The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.

Despite his success as a director-choreographer, Tommy Tune still thought of himself as a performer first. For My One and Only, a reworking of the 1927 Gershwin musical Funny Face, he was happy to star with his friend Twiggy and co-choreograph with his frequent collaborator Thommie Walsh. But when the director was fired, Tune and Walsh were pressed into service as co-directors, meaning that Tune now wore three hats: as director, choreographer, and star actor. Tune turned My One and Only into a fleet, fast-moving entertainment built around a parade of prime Gershwin songs––an early example of the jukebox musical. Its bold staging used movement and lighting to drive the story forward against a series of bright geometric drops and flats that evoked the 1920s with stylish minimalism.

Tune took styles and motifs of the past and remade them as fresh, exciting new performances. In the show’s penultimate number, Tune evoked first generation film musicals with their frenetic dance ensembles and screwball performers, as in this number from 1929’s Show of Shows. Tune joyously updated this style of dance for “Kickin’ the Clouds Away.”

In an evening full of stellar dances, perhaps the high point was a second act duet between Tune and Charles “Honi” Coles. Coles, who turned 72 just before My One and Only opened, was known for his legendary partnership with Cholly Atkins in the 1940s and 50s. Theirs was a “class act,” in which they appeared in elegant attire, performing a relaxed, graceful tap style that incorporated glides and turns, all danced in mirror-like precision. Their most famous number was a slow, deliberate tap routine to “Taking a Chance on Love.”

When Tune and Coles dance to the show’s title song, it is a number steeped in the earlier Coles and Atkins style, exhibiting an extraordinary economy of movement and sound. Tune later reflected on Coles’s influence on his own dancing, saying, “Honi was always saying, ‘More nonchalant, Tommy, more nonchalant. Besides the sounds that you’re making, it’s the spaces that count.’ It’s the way great painters leave things out,” Tune noted.

After the long-running Grand Hotel, which won him more Tonys, Tune reconfirmed his status as the last of the superstar director-choreographers with his next musical, The Will Rogers Follies, the story of the beloved star of radio, vaudeville, and films, and one of the most popular headliners of the Ziegfeld Follies. For this look back at a bygone theatrical era, Tune’s staging drew upon a trove of forgotten show business antecedents, revisiting the showgirl lineups and dramatic tableaux of the Ziegfeld Follies with both authenticity and ironic detachment.

Busby Berkeley’s cowgirl chorus, with its “hat-ography,” in the 1930 film, Whoopee, was an inspiration for Tune. Tune took Berkeley’s idea and streamlined and refined it for The Will Rogers Follies’ opening number.

The showstopping “Favorite Son” celebrated Rogers’s bipartisan appeal and offered up his formula for a fresh approach to politics. It was a dazzling expansion of a precision number performed by the Russell Markert Dancers in the 1930 film, King of Jazz.

In Tune’s reincarnation, the pace is quickened to capture the rhythm of the lyrics. The routine, flawlessly performed, creates a delicious blur of whizzing colors and crisscrossing limbs. Without ever rising to its feet, “Favorite Son” became the dazzling dance highlight of The Will Rogers Follies.

In the 1980s, Tune created a concert act for himself, harvesting American songbook standards for a song and dance presentation that he sometimes referred to as “contemporary nostalgia.” “Old plus old equals new,” Tune said. But there was nothing gauzy or dated about the performance. Tune performed the material with fresh exuberance and delight, as if it had just been created.

The act proved remarkably flexible and durable, playing nightclubs and concert halls across the country and the world for more than thirty years. Tune’s enthusiasm for touring brought him a unique kind of celebrity. For many, he became the quintessential “Broadway Baby,” a man who summoned the spirit and continuity of the theater, even for those with little knowledge of the art form. Long after his contemporaries had stopped dancing, Tune continued to perform with precision and panache, as in this clip from the New York City Center Encores! 2015 production of Lady Be Good.

By the time Tune received a special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2015––his tenth, altogether––he had inspired a new generation of director-choreographers like Susan Stroman, Jerry Mitchell, and Casey Nicholaw. In musicals like The Producers, Kinky Boots, and The Book of Mormon, they absorbed Tune’s creative use of show business motifs and his ability to move forward by drawing on the past—“old plus old equals new”—and successfully adapted them to a new, faster-paced era.

Feature image: Tommy Tune directing “Cloud 9” in 1982. Photo by Bernard Gotfryd, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

November 15, 2021

Why increasing deglobalization is putting vulnerable populations at risk

The record of globalization is decidedly mixed. Whereas proponents tend to associate globalization with beneficial developments such as the expansion of democracy and improved access to goods and services, critics highlight the human costs: rising inequality and political and economic exploitation. Some of these critics might welcome the argument put forward by some observers that globalization has peaked and we are now witnessing the obverse side of the coin—decreasing interconnectedness termed deglobalization. Given the staggering number of serious human rights violations across the globe (exploitation of garment workers in Cambodia or Bangladesh, the use of human slaves in the fisheries off the coast of Indonesia, and the uprooting of farmers from their land to make room for hydroelectric dams or palm-oil plantations), debates about the impact of deglobalization on human security are urgently needed.

In an effort to understand the implications of deglobalization for human security, it is helpful to disaggregate deglobalization into physical and social technological components. Globalization is usually understood in terms of physical technologies—notably advances in transportation and telecommunications (ICTs)—and the processes built on them (trade, financial flows). In physical technology terms, globalization remains robust.

But physical technologies are only part of the story; globalization has also involved the development and spread of social technologies—norms and institutions—that guide the integration of physical technologies into domestic and international society. These social technologies, usually grouped together under the term “Liberal International Order,” are the primary site of deglobalization. While the spread of human rights norms, the emergence of transnational human rights advocacy networks, and the diminution of the ability of states to abuse human rights without penalty are important elements of a liberal international order associated with globalization, deglobalization is likely to reverse what progress has been made in terms of human security. Many countries are likely to turn inward and can be expected to pay less heed to human rights abuses and to international institutions, norms and rights.

Potential implications of deglobalization for human security in the case of Myanmar (Burma)Myanmar, one of the poorest countries in the world, has experienced decades of civil war and mass human rights violations at the hands of a military government in place since 1962. The catalogue of crimes is voluminous, including the large-scale assault on Rohingya civilians starting in 2017, pushing nearly 1 million to flee to Bangladesh. When, by the end of the 1980s the country was nearing economic ruin, the military regime began to accept calls for greater democracy and civil rights—opening the way for the emergence of a new political movement under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi. Democratization reached its apogee in 2015 with the election of Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy to a parliamentary supermajority.

Significantly, the emergence of the democratic movement in Myanmar coincided with the rapid growth of ICTs in the West and subsequent global spread. Whereas, prior to the emergence of ICTs, the government controlled traditional media outlets and limited domestic and international awareness of events on the ground, ICTs now undermined government control of information flows. Activists were able to upload images directly on their mobile phones and draw attention to the mistreatment of Burmese citizens. In this aspect, the tandem of ICTs and global democracy norms drove domestic political reforms. But the physical technology element of globalization cuts in other directions as well. The integration of globalization’s ICT physical technological foundations played an important role in the repression of the Rohingya. Facebook enabled the rapid distribution of innuendo and rumour targeted at ethnic and religious minorities. It also enabled mob violence by allowing provocateurs to generate and harness outrage and organize individuals into collective action. In a society without institutionalized minority-rights protections and with a government unable to invoke moderating civil society norms, violence has flared repeatedly with destructive results.

So then, how has the international community reacted to the persistent human security threats in Myanmar? Responses vary in terms of the social technologies they seek to promulgate. The UN has actively sought to bring human rights norms to bear on Myanmar in conjunction with the physical technologies of globalization. The UN special rapporteur Yanghee Lee has pressed social media companies and foreign investors to promote human security in Myanmar. Lee has also called for states to take action, warning that democracy is failing in Myanmar and that the UN Security Council should establish an international tribunal to adjudicate crimes against humanity and war crimes perpetrated since 2011. The EU has taken a similar approach, though more often emphasizing economic development and capacity building. The United States, much like the EU, imposed unilateral sanctions and, instead of engaging with the junta, tried to isolate it further. Clearly, the US, EU, and elements of the UN system are working to apply social technology—global human rights norms—to the case of Myanmar, operating in tandem with social media exposure of abuses. These efforts, however, are running up against the countervailing social technologies—national/ethnic majoritarianism, national sovereignty—that underpin deglobalization.

Notably, China’s policy employs a different set of social technologies—emphasizing sovereignty and non-intervention—that distinguishes its approach clearly from the West. When the US and the EU imposed sanctions, China, like Russia, protected Myanmar by casting a veto against UNSC Draft Resolution S/2007/14-12/01/2007, arguing that the situation did not constitute a threat to regional or international peace. As with China, for ASEAN, of which Myanmar is a member, the bottom line for many years has been to protect the sovereignty of its member states, even if this meant looking the other way in the face of severe human rights violations. Gradually, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines began to see a need to relax the principle of non-interference and support national reconciliation in Myanmar.

Should international pressure in favor of human rights and good governance subside as deglobalization unravels the social technological threads of the Liberal International Order, the implications for Myanmar and other countries in similar situations are dire. The modern state’s capacity to control and manipulate information flows and bring to bear material capabilities—including elements of the physical technologies underpinning globalization—on its own citizens gives it great scope for inflicting human suffering.

More physical technology cannot resolve this emerging human security crisis.

Featured image by Jéan Béller via Unsplash

November 13, 2021

Fake news, misinformation, and disinformation: journalism today?

Fake, false, inaccurate, misleading, and deceptive. This rhetoric is all too familiar to the news consuming public today. But what is fake news and how does it differ from misinformation and disinformation?

Referring to falsified or inaccurate information, “fake news” can be defined as “false information that is broadcast or published as news for fraudulent or politically motivated purposes,” whereas “misinformation” refers to any false information with intent to deceive its audience. “Disinformation,” by contrast, refers to false information that has the intent to mislead and usually refers to “propaganda issued by a government organization to a rival power or the media.”

Given this language and skepticism surrounding the news industry, can the media and journalists regain public trust?

The five books in this reading list explore communication challenges facing the media. Sample open chapters and discover how the industry can bridge the gaps between the public, journalism, and academia.

News After Trump: Journalism’s Crisis of Relevance in a Changed Media Culture by Matt Carlson, Sue Robinson, and Seth C. Lewis

News After Trump: Journalism’s Crisis of Relevance in a Changed Media Culture by Matt Carlson, Sue Robinson, and Seth C. LewisIn News After Trump, the authors provide an in-depth look at former President Donald Trump’s relationship with the press and examine the place of journalism within a shifting media environment. Taking a forward-focused approach they propose a future in which journalists can reclaim public trust by developing a moral voice and building relationships.

Learn more in the introductory chapter, “Decentering Journalism in the Contemporary Media Culture.”

Journalism Research That Matters edited by Valérie Bélair-Gagnon and Nikki Usher

Journalism Research That Matters edited by Valérie Bélair-Gagnon and Nikki UsherIs journalism still relevant? Journalism Research That Matters explores contemporary media industry challenges. Including perspectives from academics and journalists, this book provides a blueprint for bridging the current gap between scholarship and practice. Can they cumulatively overcome industry disruption?

In this chapter, discover “Why News Literacy Matters.”

Imagined Audiences: How Journalists Perceive and Pursue the Public by Jacob L. Nelson

Imagined Audiences: How Journalists Perceive and Pursue the Public by Jacob L. NelsonIn Imagined Audiences, Jacob L. Nelson addresses the current crisis facing the news industry by considering the relationship between journalists and their audiences. Do the audiences that journalists imagine match their actual readership?

Read chapter three, “The Promise of Audience Engagement,” and explore differing perspectives on whether journalists should increase their focus on audience engagement to increase media success.

Democracy without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society by Victor Pickard

Democracy without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society by Victor PickardContrasting current belief that the media industry has only recently fallen into crisis, in Democracy without Journalism Victor Pickard expresses that today’s misinformation society is a symptom of a flawed media structure stemming from its commercialization in the 1800s.

Read the introductory chapter and explore what happens “When Commercialism Trumps Democracy.”

The Epistemology of Fake News edited by Sven Bernecker, Amy K. Flowerree, and Thomas Grundmann

The Epistemology of Fake News edited by Sven Bernecker, Amy K. Flowerree, and Thomas GrundmannIn The Epistemology of Fake News explore an in-depth account of the concept of fake news, the structural mechanics that help promote it, and what can be done to rectify the current situation.

In the chapter “Speaking of Fake News,” uncover an expansive review of literary definitions and discover the importance of defining of fake news if the industry is ever to overcome such threats.

Featured image by Gerd Altmann via Pixabay

November 11, 2021

Police-free schools: the new frontier in ending the school-to-prison pipeline

On 25 October 2015, a Black high school student named Niya Kenny filmed a white school police officer body slamming her classmate, a Black sixteen-year-old girl, to the floor at Spring Valley High School in Columbia, South Carolina. Deputy Sherriff Ben Fields placed Shakara in a headlock, flipped her desk over, and then dragged and threw her across the classroom floor, all for allegedly refusing to hand over her cell phone. Yet it was Niya and her classmate who were arrested, charged with criminal “disturbing school,” and sent to juvenile detention.

Niya’s video went viral. Students across the country involved in the Alliance for Educational Justice and local groups working to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline wrote and delivered love letters to Niya at a national youth power conference. The movement delivered a petition with 150,000 signatures to drop the charges against Niya and Shakara, and the incident served to accelerate the growing, but at the time little known, movement for police-free schools.

Community organizing and police-free schoolsRiding the wave of mass protests against police violence and racism in 2020, Black and Brown parents and students won their first victories in defunding or removing police from schools. Since even before the Niya Kenny incidents, these local activists had been patiently organizing for police-free schools for many years. They had built a base of student and parent leaders knowledgeable about the issue, had developed and even submitted policy proposals, and had been lobbying school board members. When the protest wave opened up new opportunities, these organizing groups were ready. They won some quick and early victories and sparked a movement that spread across the country.

Long-established organizing campaigns won quick victories in 2020, cutting the school police budget by 35% or $25 million in Los Angeles in 2020 (and by another $25 million in 2021), ended the contracts between the Madison and Denver school districts and their police departments, and entirely eliminated the Oakland Schools Police Department, reinvesting its $6 million budget into a non-carceral safety plan. Since June 2020, over 138 school districts have announced that they will remove police from schools.

Police do not make students safePolice-free school advocates spent years developing the argument that school police, also known as school resource officers (SROs), do not make schools safe. There is, in fact, no research-based evidence that demonstrates that police improve safety in schools.

“There is, in fact, no research-based evidence that demonstrates that police improve safety in schools.”

As opposed to promoting safety, school police target students of color and those with disabilities, which starts them on the road to prison. During the 2017-18 school year, nearly 230,000 students were referred to law enforcement, with about a quarter leading to arrests, often for minor behavioral issues. In schools with police presence, students are five times more likely to be arrested and charged than students in schools without SROs. Overall, Black students are twice as likely to be arrested in school as white students. Many young people have their first encounter with police in schools. One study found that in North Carolina, school-based referrals make up about 40% of the referrals to the juvenile justice system and most of these referrals are for minor, nonviolent offenses.

The rise of armed security personnel in schools came with zero tolerance approaches to the so-called war on drugs in the 1980s and escalated in the 1990s as part of the move towards mass incarceration of Black and Brown people, which Michelle Alexander has called the “New Jim Crow.” In the late 1970s, there were fewer than one hundred police officers in schools in the US. By 2003, there were almost 15,000 and the proportion of schools with armed security continued to grow.

The fact of the matter is that public schools in low-income communities of color invest in systems of discipline, control, and punishment rather than student support. The result is that 1.7 million students attend schools with police but no counselors; 10 million students attend schools with police but no social workers.

Alternatives to zero tolerance and policingAdvocates working to end zero tolerance and create police-free schools are organizing for alternative approaches to criminalization like restorative justice. When students misbehave or fight, rather than being disciplined or arrested, school staff and student peers hold restorative circles—dialogic processes that get at the root causes of the issue and help resolve conflicts. The main problem, however, may not be student misbehavior. Rather, when teachers start to learn about restorative justice, it often leads them to realize that they must break with zero tolerance mentalities and practices that result in punishing and criminalizing students rather than supporting them. In this way, the movement for police-free schools seeks to create supportive school climates and to reimage public schooling as safe, humane, and empowering for low-income students, students of color, and all students.

The movement to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline“The movement for police-free schools seeks to … reimage public schooling as safe, humane, and empowering for low-income students, students of color, and all students.”

In the early 2000s, a new movement arose to challenge the school-to-prison pipeline. Its focus was primarily on ending zero tolerance school discipline policies that suspend and expel students of color and those with disabilities at high rates, pushing them out of school and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Black students were and still are three times as likely to be suspended as white students; in Texas, over 75% of Black students are suspended at some point in their high school years.

When parents and students of color first named the school-to-prison pipeline and called for an end to zero tolerance, few were listening. After fifteen years of organizing, in 2014, the US Departments of Education and Justice issued joint guidance calling for an end to zero tolerance and warning school districts against racially discriminatory discipline practices. Organizing groups won a rolling series of victories in states and districts across the country that ended zero tolerance discipline policies. As a result, suspension rates have begun to fall, in some places dramatically. In Los Angeles, a coalition of organizing groups won a series of victories in campaigns to reduce exclusionary discipline, culminating in the end to suspensions for “willful defiance” in 2011. Lost days of instruction due to suspensions fell from about 75,000 in 2007-18 to 8,300 by 2013-14 and fewer than 5,600 lost days in 2017-18.

Ten years ago, the Black Organizing Project in Oakland declared the goal of completely removing police from schools by 2020. Few were listening. Now, the demand for police-free schools is gaining momentum across the country. It is the new frontier of the movement to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline and transform public education towards racial equity and educational justice.

Featured image by NeONBRAND via Unsplash.

November 10, 2021

Many words for a small world and a little-known centennial

What do we call the world in which we live? The specifically Germanic noun world (German Welt, Old English werold) is perhaps the most puzzling word known in this area. It was once a compound consisting of “man” (wer-, related to Latin vir: compare English virility) and “age” (-old). The word referred to the time one spent on the earth, rather than space—from our point of view, an odd confusion of concepts. The Scandinavians had a similar word, but it appeared in the extant texts late and was probably borrowed from their neighbors. The Old Scandinavian native word for “world” was heimr “home,” a cozy name indeed. Someone who never traveled, a stay-at-home, was called heim-sk- “stupid.” They named “inhabited earth” mið-garðr (ð, as th in English the), that is, “middle yard,” a territory fenced in, or perhaps their “yard” was situated on the vertical axis, between heaven and earth.

Other than that, we observe a surprisingly wide list of words for the place people inhabit. Earth has a few recognizable cognates. Apparently, th was some kind of suffix. The phrase some kind of conceals our ignorance of this element’s function; historical linguists call it an enlargement. Once, in an old German religious text, ero “earth” turned up. In an Old English incantation (charm), some goddess apostrophized as Erce seems to be invoked. The beginning is: “Erce, erce, erce, earth’s mother.” Nothing is known about her; perhaps this treble repetition of the same word is magic rigmarole (not even a name). Yet the syllable er- is suggestive, because er- was indeed the ancient root of the word earth.

The triumph of etymology: Bears are brown, grass is green.

The triumph of etymology: Bears are brown, grass is green.(Image by mana5280 via Unsplash)

We of course would like to ask why er– was chosen as the root of the planet’s name. But wherever we dig, we encounter the same syllable. For example, in Homeric Greek, ‘éra-dze meant “to earth.” An Old Icelandic noun with another “enlargement” was jörfi, that is, jör-f-i (from the reconstructed earlier form er-wan) “sand mound”; the word is still current in Icelandic. Even if we assume that the root er- meant “sand” or “soil,” we’ll be none the wiser. To repeat: why er-? This is of course the main question that interests us. Those who ask etymologists why a fish is called fish and why summer is called summer want to know only this. A list of cognates and discussion of enlargements and of vowel or consonant alternations interest only professional linguists. Sometimes an answer is available. For example, the name of the animal name bear is rather probably derived from the color word “brown.” Grass and green are related to grow. I am aware of only one, perhaps successful, attempt of making sense of the root er. In 1921 (so a hundred years ago!), Otto Hoffmann, a distinguished Classical scholar, cited several er-words that refer to splitting and sundering, referred to a convincing parallel, and suggested that the earth had been conceived as a “separate territory.” To be sure, we are left wondering why er– should have been endowed with such a meaning, but sooner or later etymologists always run into this wall (unless, to repeat, the roots are obviously expressive). To make our task even more complicated, we note that in Ancient Egypt, A’aru was the name of the field of the dead. Can earth be a migratory word (Wanderwort)? Probably not, though some evidence of the world-wide currency of this root is suggestive.

We may be less ignorant when it comes to land, because the words that are related to it display a wider variety of senses. This was the main problem with earth: all the cognates mean just “earth.” The Celtic cognates of land refer to “open space, enclosure.” The idea of enclosing one’s territory played an important role in the coining of words by our ancestors. One should only not carry this valid point to its extreme, as was done by the prominent German linguist Jost Trier, who saw fences everywhere. Some of his suggestions were inspiring, while others look fanciful. In any case, Irish land ~ lann does mean “enclosure, open space, plain,” while the Slavic cognates mean “heath, desert.” If we assume that in the history of words concrete senses usually precede the more abstract ones, land-, it seems, first meant “uncultivated field” or something like it. Yet the main (crucial!) question of course remains: “What was there in the syllable land that suggested to speakers the idea of an open space (overgrown with grass)?

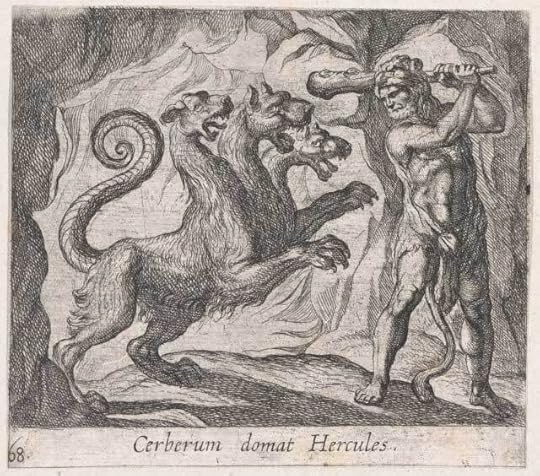

The hell dog Cerberus was one of the most famous chthonic creatures.

The hell dog Cerberus was one of the most famous chthonic creatures.(By Antonio Tempesta, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When we deal with short roots, we can often answer those who want to know where a certain word came from only when it is sound-imitating (onomatopoeic) or obviously expressive. Perhaps this is what happened in the history of ground. In Old English, ground meant “bottom of the sea.” Ships can still run aground and are sometimes grounded. Ground is, most probably, related to the verb grind by ablaut (vowel alternation). The initial cluster gr- is indeed expressive, and I have often written about it: grit, grip, grumble, groan, grim, grouch, gruesome, and quite a few others arose as sound symbolic words, even though gr- may evoke dissimilar associations. The Old English monster Grendel did not get his name for nothing. Among others, gr– might produce the idea of a strong effort, so that the word ground perhaps made people think of breaking the resistance of the soil on which they built their houses or grew their crops. The verb break, which begins with br-, a similar sound combination, is almost certainly expressive. The same holds for the adjective brittle, related to the Old English verb brēotan “to break,” allegedly of unknown origin! (Br– is fine, but where did the rest of the verb come from?)

While travelling over the world of Indo-European speakers, we observe again and again how many words for “earth” we encounter. Latin terra comes to mind first, because it has left so many traces in English (terrain, territory, terrestrial, subterranean, and so forth). Perhaps terra is related to torrid. If so, its first sense may have been “very dry earth.” The oldest Indo-European word for “earth” seems to have been humus, and it is widely believed that Latin homo “human being” has the same root. (While we live, we cannot be lower than the ground; hence, via French, English humiliate and humble, the latter with an excrescent b in the middle). Humus (no connection with Arabic hummus) is related to Russian zemlia “earth” (stress on the second syllable).

This what the Greeks thought of Gaea’s appearance.

This what the Greeks thought of Gaea’s appearance. (“The Birth of Erichthonius. Gaea, goddess of Earth … presents the young Erichthonius to Minerva.” Via The New York Public Library Digital Collections.)

The adjective autochthonous “indigenous” is bookish but not too rare. Khtōn is still another Greek word for “earth.” It is related to Latin humus, mentioned above. A more specialized adjective with the same root is chthonic, often used in mythology: the chthonic deities lived in the underworld. And finally, let us not forget Gaea, “the earth,” so familiar from geology, geometry, and geography. It is comforting to know that Gaea is both the child and the wife of Heaven (Ouranós), but, sadly, nothing is known about the origin of her name (the root is gē; it must have referred to something very earthy). Perhaps the guttural beginning of khton and Gaea had some sound-symbolic value, but this is unproductive guesswork.

Feature image by NASA via Unsplash

The Arctic Paradox: why the Arctic is caught in the conflicting pressures of global climate change

In October 2021, the British Antarctic Survey launched a new immersive exhibition called Polar Zero in the city of Glasgow to coincide with the COP26 conference between 1 and 12 November. The ice-covered poles have been used repeatedly to convey the urgency of the climate emergency. Melting ice, thawing permafrost, and retreating glaciers are very visible reminders of what is happening on our warming Earth. The exhibition features an Antarctic ice core containing trapped ice bubbles dating from 1765—a moment before the onset of the industrial and urban revolution that transformed human life and the carbon cycle.

In 1765, a German theologian and missionary David Cranz published his Historie von Grönland, which described the natural and cultural life he encountered on the island during a year-long stay. The Arctic he encountered was being subjected to ever greater external scrutiny and interest. The quest for a Northwest Passage was popular with national and commercial sponsors alike. In the 1770s, the Hudson’s Bay Company was sponsoring Samuel Hearne to travel to northern Canada and discover an ice-free passage to Asia. Arctic whaling was well established by the 18th century with Dutch and other European ships harvesting whales off Greenland and Svalbard. Mining and smelting were already part and parcel of life in northern Sweden with mines operating in the 17th century. Well before 1765, therefore, the Arctic’s rich resources—actual and potential—were being realised.

This view of the Arctic as a resource storehouse sits uneasily with the experiences of the indigenous communities who call the far north home. In today’s Arctic about 1 million people are indigenous in origin and many of those communities have had direct experiences of resource projects and settler colonialism. In the 19th and 20th centuries, resource exploitation expanded to take on a raft of objects from oil and coal to opportunistic discoveries of mammoth ivory. Across the Arctic, national governments, military engineers, and commercial enterprises built a network of roads, pipelines, ports, airports, and other forms of infrastructure. Cold War tensions and the oil crises of the 1970s added further impetus for this push for exploitation and development.

A paper published in Nature in 2005 referred to an “Arctic paradox.” It drew attention to the fact that the Arctic was a pollution sink whereby human and animal communities were on the receiving end of environmental change originating elsewhere. In the 1980s and 1990s, attention was often drawn to the problem of airborne pollution and “acid rain” rather than global climate change. Indigenous groups, including the Inuit, criticised this widespread tendency to represent the Arctic as a pristine wilderness. This not only mis-read the Arctic’s historical experiences of exploitation and degradation by outsiders, but also under-estimated the damage being done by global flows of airborne pollutants in the 20th century. In 2005, Shelia Watt-Cloutier was Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference and she filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) highlighting the harmful impact of climate change caused by the United States.

Figure 1. Global and Arctic temperature change since 1850.

Figure 1. Global and Arctic temperature change since 1850.The Arctic is warming much more rapidly than the global average (Figure 1). This tension between the Arctic being in the frontline of climate change and the continued desire amongst some Arctic states such as Canada, Russia, and Norway to extract oil, gas, and coal epitomises this paradox. Indigenous and northern communities can benefit directly from fossil fuel extraction and mining even if they appreciate only too well in their daily lives the costs of climate change. What does aggravate, however, is when communities are neither consulted nor benefit from revenue streams associated with mining. For the last four or five decades, indigenous communities such as the Iñupiat in Alaska have become notable land and resource rights holders via the 1972 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Climate warming is driving permafrost thaw, sea ice loss, and ecological change across the Arctic. Just before COP26, an EU policy paper for the Arctic published in October 2021 called for oil, coal, and gas in the Arctic to stay in the ground in the name of addressing the climate emergency. Well intentioned? Possibly. But the EU is heavily dependent on Russian gas supplies from the far north and no EU state has substantial Arctic-based resource potential. Campaigning to “save” the Arctic can lead to the worst kind of virtue signalling and indigenous groups are very critical of what they think of as green colonialism. Petro-states such as Canada, Norway, and Russia are deeply invested in oil and gas extraction (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Gazprom Arctic gates oil loading terminal on the Yamal Peninsula in Siberia.

Figure 2. The Gazprom Arctic gates oil loading terminal on the Yamal Peninsula in Siberia.(Image credit: Gazprom Neft PJSC)

Extracting further hydrocarbons makes no sense in a region that is experiencing warming three times higher than the global average. But what makes sense in Brussels and Paris may not make sense in the eight Arctic states since such directives commonly ignore the interests and wishes of indigenous communities. Whatever happens, as Arctic landscapes warm and thaw, CO2 and methane won’t stay in the ground, wildfires will raze trees to the ground, and infrastructure will collapse into the ground.

In our work we have explored the changing environment and explained why the Arctic is caught up in a series of conflicting pressures. The Arctic is now exceeding climate change predictions by decades—it features prominently in the Sixth IPCC Assessment Report (AR6) of the IPCC due in 2022, especially in relation to climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability relating to the people of the Arctic. A vast human-induced experiment in rapid climate and ecological change is playing out at the top of the world. These environmental changes have consequences for all of us.

Featured image by Annie Spratt via Unsplash

November 8, 2021

Wondering about the subjunctive

“He wondered if he were hallucinating.” I came across that use of the subjunctive while listening to the audiobook of Neil Gaiman’s American Gods.

To me, the subjunctive mood—the “if he were”—sounded odd with the verb “wondered,” and it stuck in my ear. Then again, I don’t use the subjunctive very often. I tend to use it sparingly, on the rare occasions when I am being directive or when I say things like “If I were you, I’d …”

Grammarians will tell you that mood is the way that a speaker’s stance toward a statement is shown, whether it is a statement, command, wish, etc. Experts differ on how many moods English has, but the language is not particularly moody. The indicative is used to make statements. The imperative is for commands and prohibitions. The conditional is used for various prerequisites (like “If you wash the dishes, I’ll put them away” or “I’ll give you a ride, if I can.”).

The subjunctive mood with a bare verb is used after verbs that express a demand, recommendation, request, or necessity (as in “I insist that everyone be punctual,” “I suggest you be careful,” or “It’s required that everyone show identification”). The subjunctive with were is used in expressions that set up situations that are unreal, hypothetical, or contrary-to-fact, or in suppositions or wishes (“Were I living on Mars, I might have super-strength because of the gravity,” “If I were at my computer, I could look that up,” “Were I stranded on a desert island, I don’t suppose I’d survive long.”).

The subjunctive also crops up in some fixed phrases, like “As it were,” “Be that as it may” and “So be it.” It had been a more vital feature of grammar in Old and Middle English where the subjunctive was used to signal indirect speech and a range of dependent clauses. Over the centuries, many of its functions were taken over by other grammatical tricks.

Getting back to American Gods, I was puzzled by the use of “if he were” after the verb “wondered,” since the wondering seemed to me to conflict with the idea of things being hypothetical or unreal. The character Shadow just wasn’t sure if he was hallucinating. (Spoiler alert: he probably was, because he had just been talking to his dead wife, and a squirrel is about to offer him a drink of water from a walnut shell.)

It seemed to me that I would write things like:

He wondered if he was ill.

She wondered if she was winning.

I wondered if I was overthinking things.

All of these sound odd to me with the subjunctive were substituted for was.

He wondered if he were ill.

She wondered if she were winning.

I wondered if I were overthinking things.

But it turns out that Gaiman’s use of the subjunctive is not all that unusual. Print usage seems split. A quick search of Google books revealed authors using examples like:

He wondered if he was still alive … .

And she wondered if she was really interested in him.

He wondered if he was dying.

But also examples like these:

He wondered if he were the only one alive,

She wondered if she were dreaming.

He wondered if he were going to sleep, … .

Writers and editors I asked were split. Some said they would use “was” in casual conversation, but use “were” in writing. A couple indicated that their intuitions on the matter were influenced by French or Spanish grammar, where a more robust subjunctive is used to indicate uncertainty as opposed to fact. Perhaps Neil Gaiman (or his editor) was influenced by French.

What’s more likely is that Gaiman is using the were-subjunctive as a purposeful bit of formality to add some drama to the character’s perplexity. At an earlier key moment in American Gods, we find another example: “Czernebog looked as if he were about to protest; and then the fight went out of him.” Here too, the subjunctive seems to underscore the uncertainty of the moment. Yet, at other places in the novel, where there is less tension, Gaiman uses the simple past tense: “He wondered if she was taking tranquilizers,” “Shadow wondered, coldly and idly, if he was going to die,” “For one moment, he wondered if the man was crazy.”

H. W. Fowler called the subjunctive “moribund” in his 1926 Dictionary of Modern English Usage, but noted that a few uses were surviving. For writers of narrative, this may be may be one of them.

Feature image: “Long shadows from trees behind in winter times in the fields” by Thomas Lendt. CC BY SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

November 6, 2021

The ultimate reading list for every academic librarian

Whether you are looking to escape into the histories of some libraries or looking to expand your knowledge on the future of reading and research we’ve got something for every librarian with this reading list.

How many have you read? Which ones are interested in? Let us know your thoughts below.

Scholarly Communication: What Everyone Needs to Know® by Rick Anderson

Scholarly Communication: What Everyone Needs to Know® by Rick AndersonNeed an overview of what’s happening in the world of journals and books? Then this is the book for you! Offering an examination of books, journals, copyright law, digital archiving, metadata, and much more, discover the many problems that arise due to conflicts between the various values and interests at play within these systems and how the implications of these issues extend far beyond academia.

Information Hunters: When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies Banded Together in World War II Europe by Kathy Peiss

This book tells the story of an unlikely band of librarians, archivists, and scholars who travelled abroad to collect books and documents to aid the military cause during World War II.

In this fascinating account, cultural historian Kathy Peiss reveals how book and document collecting became part of the new apparatus of intelligence and postwar reconstruction. Focusing on the ordinary Americans who carried out these missions, she shows how they made decisions on the ground to acquire sources that would be useful in the war zone as well as on the home front.

Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World by Naomi S. BaronRead: Information Hunters: When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies Banded Together in World War II Europe

In 2007, Amazon introduced its first Kindle. Three years later, Apple debuted the iPad. Meanwhile, as mobile phone technology improved and smartphones proliferated, the phone became another vital reading platform.

In Words Onscreen, Naomi Baron, an expert on language and technology, explores how technology is reshaping our understanding of what it means to read and explains why the virtues of eReading are matched with drawbacks.

Read: Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World

How We Read Now: Strategic Choices for Print, Screen, and Audio by Naomi S. Baron

How We Read Now: Strategic Choices for Print, Screen, and Audio by Naomi S. Baron The digital revolution has transformed reading, and with the recent turn to remote learning, onscreen reading may seem like the only viable option. Yet selecting digital is often based on cost or convenience, not on educational evidence. In this book, author Naomi Baron connects research insights to concrete applications, offering practical approaches for maximizing learning with print, digital text, audio, and video.

Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library by Wayne WiegandRead: How We Read Now: Strategic Choices for Print, Screen, and Audio

Despite dire predictions in the late twentieth century that public libraries would not survive the turn of the millennium, their numbers have only increased, which makes us ask, why do Americans love their libraries?

Drawing on newspaper articles, memoirs, and biographies, Part of Our Lives paints a clear and engaging picture of Americans who value libraries not only as civic institutions but also as public places that promote and maintain community.

The Oxford Guide to Library Research: How to Find Reliable Information Online and Offline (4ed) by Thomas MannRead: Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library

This book is not “about” the Internet: it is about the best alternatives to the Internet. It shows researchers how to do comprehensive research on any topic and explains the variety of search mechanisms available so that the researcher can have reasonable confidence that they have not overlooked something important. This includes not just lists of resources, but discussions of the ways to search within them.

Read: The Oxford Guide to Library Research: How to Find Reliable Information Online and Offline (4ed)

Follow us on Twitter to stay up-to-date with the latest from Oxford Libraries.

Think your library should be featured in our #LibraryOfTheWeek? Email us with their information or send us a message via Twitter.

Feature image by Augstin Gunawan via Unsplash

November 5, 2021

Engineering a new capitalism for the 21st century

Former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney has observed that society has, unfortunately, come to embody Oscar Wilde’s old aphorism: “knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing.” There is a growing consensus that values should include all forms of capital—natural, human, and social as well as the financial. Unfortunately, modern liberal capitalism pays little heed, and the obsession with profit crowds out other motivations, making the world a more selfish place and less resilient. Our economic system is dominated by the assumption that people want to maximise utility (the amount of satisfaction or fulfilment that a consumer receives through the consumption of a specific good or service) with least effort, and that no-one works except for a reward. This hollow vision is debilitating. Carney’s seven key values are: solidarity, fairness, responsibility, resilience, sustainability, dynamism, and humility—all with compassion. His vital components of any good society are fairness between the generations, in the distribution of income and of life chances. Economics should be about increasing social well-being, but instead it is obsessed with market pricing. Nevertheless, there are glimpses of hope. The imperative of climate change is forcing us to change through, for example, the “green” agenda. Here I want to put the case for a re-examination of the moral fundamentals of our value systems to build a new form of capitalism needed to address twenty-first-century challenges such as climate change.

But why is this an engineering issue? Engineering and technology were a major driver of the first English Industrial Revolution. Now they drive the information revolution. Since technical development is integral to our economic and political systems, engineers have a duty to help change the ways in which we account those forms of capital that are currently not properly considered. I propose that we follow the suggestions of Tom Settle, outlined in his 1976 text In search of a third way, to develop a “principled capitalism” to replace liberal capitalism. He argues that moral principles should be driving our individual and collective decisions rather than utility and profit.

“moral principles should be driving our individual and collective decisions rather than utility and profit”

Prior to the agricultural and industrial revolutions, raw materials, land or space, and labour were goods not commodities. Then Britain changed from a society with markets to a market society, which we now know as capitalism, and goods became commodities. We should think of “goods” as opposite to “bads,” for example the feelings we get when we do something fulfilling—they have experiential value. Commodities, on the other hand, can be traded and have an exchange value or price—worth in exchange for something else. Consequently, today we tend to treat anything that has no price as worthless. Nowhere is this truer than in economic accounting. We seem not to recognise that attempts to treat goods as commodities will eventually fail. For example, less blood is collected in countries where people are paid, than in countries where people donate it freely. In recent times we have turned more and more of our products into commodities—even a mother’s womb. The “green agenda” is also taking this approach by, for example, allocating financial values to biodiversity data.

Tom Settle sees utilitarianism (consumer satisfaction) as telling us what we ought to do but not why. It is egoistic in that it treats self-interest as the foundation of morality. It is based on Adam Smith’s concept of the invisible hand—a force that brings a free market to equilibrium with levels of supply and demand by actions of self-interested individuals. The influential economist John Maynard Keynes did not totally reject this but believed that the only way out of an economy struggling with a recession (as in the early twentieth century) is government intervention. For an economy to come out of recession and boost aggregate demand, Keynes prescribed government expenditure expansion to achieve full employment and price stability. Friedrich Hayek argued that this would result in inflation and that money supply would have to be increased by the central bank to keep levels of unemployment low, which would in turn keep increasing inflation. The debates continue about levels of government interventions.

Settle suggests a theory of human nature based on five key integrated ingredients: rationality, autonomy, emotionality, sociality, and obligation. For example, sympathy and benevolence are impossible without emotion and directionless without rationality. He proposes replacing egoistic assumptions with a theory of categorical obligation—one in which obligation is not instrumental but absolute or unconditional to promote the public good. Politics should not be the art of the expedient but the art of promoting the public good. I have been developing this idea in my recent academic work, making analogies between gravitational and electromagnetic fields of forces and fields of human obligation interactions. An “obligation” is defined as an underived unit of “stuff” analogous to gravitational “mass” or electromagnetic “charge” in a field of interacting processes. Obligations are not for trading, so I propose that we measure them by voting as the best means we have for exercising power for the common good in a liberal democracy. In market trading, effectively the number of votes you have depend upon your wealth—the more you buy, the greater the weight of your opinion. The votes of shareholders will never protect those whose homes are affected by extremes of weather due to climate change when profit is their only motive. Obligations are too important for trading (but can be discharged), so deciding who votes for what is a political issue.

Engineering is traditionally identified as making things that work and making them work better or the art and science of practical applications to construct engines, bridges, etc. In a society based on “principled capitalism” both engineering and economics would be redefined as “helping life on earth to flourish” in their respective disciplines. It would help to reorient us to manage our changing climate and make respect for each other a central plank for our thinking, and, ultimately, prioritising social need over private profit will make us more resilient.

Featured image by Chris Briggs on Unsplash

November 4, 2021

Five books on climate change you need to read

The world’s attention is now squarely on climate change and the COP26 Climate Summit this November. Join in the conversation and keep abreast of the latest science by delving into this reading list. It contains five books on climate change which will keep you informed at this crucial moment.

Rebalancing our Climate: The Future Starts Today, by Eelco J. Rohling

Rebalancing our Climate: The Future Starts Today, by Eelco J. RohlingThis new book is the first to provide a comprehensive overview of the state-of-the-art measures to protect our environment from the impact of climate change. Eelco J. Rohling lucidly explains the different options we have to adjust the trajectory of climate change and looks at both the advantages and disadvantages of taking action.

Read Rebalancing our Climate: The Future Starts Today

Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change, by Joan Fitzgerald

Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change, by Joan FitzgeraldCities take up a tiny proportion of the Earth yet emit 72% of greenhouse gases. Urban policy can therefore make a huge difference when it comes to tackling climate change. In this book, urban policy scholar Joan Fitzgerald sets out her agenda for “greenovating” cities, drawing on interviews with practitioners in more than 20 North American and European cities.

Read Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change

Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know, by Joseph Romm

Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know, by Joseph RommThe definitive book on climate change, written in a question-and-answer format ideally suited to quick navigation and reference. New York Magazine called it “the best single-source primer on the state of climate change.”

Read Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know

Jet Stream: A Journey Through Our Changing Climate, by Tim Woollings

Tim Woollings takes readers on an atmospheric journey through the history of the jet stream, showing how it’s connected to dramatic contrasts between climate zones. In lively and readable prose, he examines how climate change is expected to affect the jet stream and what that means for the extreme weather events of tomorrow.

Read Jet Stream: A Journey Through Our Changing Climate

Meltdown: The Earth Without Glaciers, by Jorge Daniel Taillant

We hear about pieces of ice the size of continents breaking off Antarctica. But does it really matter? Will melting glaciers change our lives? In this book, Jorge Daniel Taillant demonstrates how glacier melt will impact society, public infrastructure, and our economy. He walks us through the little-known realm of the periglacial environment, takes us into the cryosphere, and connects the dots between climate change, glacier melt, and the impacts that receding glacier ice bring to livability on Earth.

Read Meltdown: The Earth Without Glaciers

To read a selection of free climate change content, visit our Climate Change Hub.

Feature image by Ivan Radic from Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers