Oxford University Press's Blog, page 95

October 6, 2021

After ice expect snow

Ice was the subject matter of a previous post (22 September 2021). Winter is round the corner, and the best way to prepare for it is to read a few murky stories about the etymology of the relevant words. Ice, as has been shown, is local (Germanic). By contrast, snow has wide connections outside Germanic. Each situation produces endless trouble. In etymology, you are damned if you are single and damned if surrounded by a large family.

Snow sounds so much alike all over Germanic that listing its multiple cognates would be a waste of space. I’ll only mention the fact that, unlike ice, the word for “snow” does occur once in the fourth-century Gothic Bible (snaiws; Mark IX, 3: “And his raiment became shining, exceeding white as snow; so as no fuller on earth can white them”; as always, I quote the English text from the Revised Version). The closest forms can be found in Slavic and Baltic: Russian sneg, Latvian snìega, and so forth. The forms for “it is snowing” are also regular, but there is an unexpected hitch: Lithuanian sniêga means “it is snowing,” while Old Irish snigid meant “it is raining or dripping” (also: Old Irish snige “drop, rain” alongside snecht ~ snechtae “snow”!). In some languages, the word for “snow” begins with the consonant n, as in Welsh nyf, Lat nix (genitive nivis), and Greek nípha (accusative). But this is a familiar complication, covered by the term s-mobile (many words have this elusive s before consonants).

A snow maiden in her element (until she melts).

A snow maiden in her element (until she melts).Image by Victoria_Borodinova

Once we leave Europe, we find Sanskrit snih “to be sticky” and nij– “to wash.” In Sanskrit, stickiness predominates to such an extent that some words with this root came to mean “loyalty, friendship,” apparently, a figurative sense from “sticking together.” Similar semantic transfers must have occurred elsewhere. Thus, Finnish olla pihkassa “to be in resin” means “to be in love.” One wonders: did the story of snow begin in the north, while in India, the original sense was forgotten, and “snowflakes” changed into “sticky substance”? Or did the ancient Indo-Europeans, those who needed the word, know only sticky snow, rather than snowdrifts and snowstorms? Let us not forget that in Irish, a language spoken by the people who have an excellent idea of what cold (and not necessarily sticky) snow looks like, our cognate means “rain.” Unexpectedly, in India, speakers seem to have experienced some discomfort while using such an odd word for “snow,” for they coined vafra, which means “snow,” with the sense familiar to people in colder regions. In southern Greece, too, nífa was replaced with khiōn, a synonym related to the word kheîon “winter.” (English hibernate, from Latin, has a root cognate with those two Greek words.).

What follows is not a law but a factor to be reckoned with: the most archaic forms of language and culture tend to be preserved on the periphery of the area to be investigated. The rationale is that every change starts somewhere and, while radiating in several directions, loses strength toward the margins. Therefore, Irish and Sanskrit may have (!) retained the initial sense of “snow.” But peripheral languages are like all the others: they change too. The surprising thing is the similarity between the Celtic and the Sanskrit words (“rain, dripping; stickiness”): if they deviated from the proto-meaning, it is remarkable that they changed in a similar way. Equally surprising is the fact that the rest of the world is so uniform in its attitude toward the connotations of the word snow.

This is not rain.

This is not rain.Image by Mark Smilyanic

Every time we come across some basic words for natural phenomena, we encounter similar difficulties: ice, snow, and rain, for example, are among the hardest items in etymological dictionaries. At one time, Chicago was the seat of a flourishing school of Indo-European studies. Its best-known product was Carl D. Buck’s A Dictionary of Selected Synonym in the Principal Indo-European Languages (1949). Buck’s verdict sounds discouraging: “Words for ‘snow’ are mostly inherited form an I[ndo]-Eu[ropean] noun and verb meaning ‘snow’, any further analysis of which is futile.” This is perhaps going too far.

The problem confronting us today should be familiar to our readers from the post on ice. We hope to reconstruct a generic term, but it may never have existed. Snow looks quite different in India and Norway, and we remember the talk about fifty Eskimo words for snow. Be that as it may, packed snow, drifting snow, wet snow, plowable snow, snow in the mountains, snow on the ground, and so forth do exist, and there may be (and often are) different names for each of them. We can reconstruct neither the area in which the Indo-European word for “snow” was coined nor the mental process behind the coining. Also, it is not unthinkable that people distinguished between snow as an atmospheric phenomenon and snow on the ground. One of the attempts to decipher the intractable word is through an Old Iranian verb that means “to slobber, salivate.” If this approach is correct, the clue to snow is not so much through the noun as through the verb to snow.

The attacks on snow, briefly mentioned above and reflected in many dictionaries and publications, seem to have an easily noticeable flaw. They assume that there once was a highly specialized sense, something like “to stick to the ground; to pin to the ground” or “to slaver, salivate,” or “grease, moisture, oil” (all of them abstracted from the texts in the Indo-Iranian languages), with a later generalization known to most of the Indo-European world as “flakes falling from the sky.” All that is of course possible, but on the face of it not too probable.

Enjoy snow while it lasts. It too shall pass.

Enjoy snow while it lasts. It too shall pass.Image by Linda via Flickr

The discrepancy between “to snow” and to “rain” has been explained away by reconstructing the root meaning “to fall from the sky,” though it seems odd that ancient people had an undifferentiated word (verb) for “to snow” and “to rain.” As late as 2009 a book of conference proceedings was published (the meeting took place five years earlier), in which Anna Helene Feulner, a scholar from Berlin, gave an excellent survey of the previous attempts to explain the origin of snow. She missed only the Semitic connection. A less detailed survey was offered in 1980 by Liam Mac Mathúna in the Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. In parts, Feulner shares the opinions of her predecessors.

Indeed, the story may have begun with the verb, because we notice the movement of snowflakes from the sky in our direction before we look at the ground. If, as has been suggested, to snow meant “to fall from the sky and remain lying, attached to the ground,” we can understand all the figurative senses cited above. But we’ll remain in the dark about the origin of the sound complex sn(e)igwh(s), the supposed oldest form of snow. The first consonant (s-) might be a prefix: s-mobile. Supposedly, the ancient similar-sounding Indo-European root nighw– “to wash” existed. Any connection with snow, remembering that our word sometimes means “rain”? In which part of the Indo-European world was the word coined? What kind of snow prevailed there? There is little hope that we’ll be able to discover the answer to those questions. Yet the attempts to decipher the word have not been quite “futile.”

Featured image by Colin Lloyd via Unsplash

The activism of Fannie Lou Hamer: a timeline

Fannie Lou Hamer was a galvanizing force of the Civil Rights movement, using her voice to advance voting rights and representation for Black Americans throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Faced with eviction, arrests, and abuse at the hands of white doctors, policemen, and others, Hamer stayed true to her faith and her conviction in non-violent progress. She helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, ran for Congress, and was one of the first three Black women in American history to be seated on the floor of the United States House of Representatives. Hamer dedicated herself fully as a grassroots organizer of the Civil Rights movement, inspiring countless activists and pushing progress forward. This is her story.

[See image gallery at blog.oup.com]Images are from Walk with Me, except where otherwise noted and linked.

October 4, 2021

A cosmic census

A new census of the Universe will allow scientists to understand more about how galaxies are born, age, and die. The millions of galaxies that have been painstakingly catalogued come in many shapes and sizes and this new work shines a light on every variety that we can see.

The new measurements, which were published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, will allow many other people to look for unusual and new types of galaxy hidden within the data. It will also help them to look at whole “populations” to better understand how they evolve. It has already been used to find interesting rare galaxies and to understand how and why they stand out from the crowd.

The international group of scientists, led by astronomers working with Professor Seb Oliver at the University of Sussex, decided to create the Herschel Extragalactic Legacy Project. This project was set up to understand images from the Herschel Space Observatory; a huge telescope in space which measured the far infrared light that is emitted from the cool dust in galaxies.

Illustration of the Herschel Space Observatory which is at the center of the work

Credit: Ève Barlier

They brought together observations from across the electromagnetic spectrum; from the bluest light emitted by hot young stars to the reddest which comes from cool dust. The team then used all this information to weigh galaxies, measure how far away they are, and count how many stars are being born within them.

Usually scientists use a small area of the night sky, but this new work brings together all of the best-studied regions allowing them to search through an unprecedented volume of the Universe. The more sky that we observe, the more rare objects we can find in order to understand all types of galaxies. One unusual object already found in the data was a giant black hole discovered only 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang.

By bringing together public data from many different telescopes and making sure everything is freely available, the team believe it will also open up data to more groups and maximise how many people can get involved. First author Raphael Shirley said: “it will be like a digital library of galaxies where anyone can take out a book on any galaxy that can be seen.” He is keen that this “open science” practice will be more widely adopted as it also means the public can use it. “Maybe there is an intrepid school student who might find an exciting new discovery hidden amongst the millions of galaxies that has been missed by the professionals.”

Featured image: © 2021, Ève Barlier

Oftener and oftener

When I was growing up, someone in authority told me that the way to pronounce often was offen, like off with a little syllabic n at the end. Often was like soften, listen, and glisten, I was warned, with a silent t. I was young and impressionable, and the t-less pronunciation stuck with me.

Later I learned that the pronunciation with the t, off-ten, was completely acceptable: the preference I had developed for offen was just a bit of linguistic prejudice someone had saddled me with.

Over the last several years, some colleagues and I have been surveying West Coast students about their pronunciation of often (and other things as well). What we found is that the pronunciation off-ten, with the t, is vastly preferred. Speakers report using it by about three to one, though some noted that they might pronounce the word either way. In class discussions, a few students also report an experience similar to mine—being warned against that telltale t.

It seems clear that the pronunciation of often has shifted away from the idea of a t-less offen. Listen and you’ll probably notice the change too. So where did the prejudice against off-ten come from?

Historically, often is from oft, so it had a t originally. The writers of pronunciation guides in the 16th and 17th centuries (called orthoepists) were split on the right pronunciation. During the 17th century the t pronunciation was widely adopted by educated speakers, perhaps as a spelling pronunciation. (That’s the phenomenon where speakers pronounce a word according to its spelling, like saying salmon with an l.) Over time, the pronunciation with a t came to be treated as a hypercorrection, and the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary even said that the pronunciation off-ten “which is not recognized in dictionaries, is now frequent in the south of England, and is often used in singing.”

Henry Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage spared the singers, but called off-ten a pronunciation practiced by “academic speakers who affect a more precise enunciation than their neighbours… & the uneasy half-literates who like to prove that they can spell.” Other writers were just as snarky, but more concise: Henry C. Wyld called the off-ten pronunciation “vulgar” and “sham-refined” in his 1932 Universal Dictionary of the English Language, and Alan C. Ross in his 1954 paper on social practices in England simply said that offen was upper-class pronunciation and off-ten was not. In the United States, The Harper Dictionary of Contemporary Usage (from 1975) was flat out prescriptive: “Often should be pronounced OFF-un, not OFF-tun, though the latter pronunciation is often affected, especially by singers.” They must have consulted the OED.

Today’s Merriam Webster online dictionary is more realistic and, thankfully, less judgmental. It cites the pronunciation as \ˈȯ-fən, ÷ˈȯf-tən\. The ÷ sign (called an obelus mark) indicates “a pronunciation variant that occurs in educated speech but that is considered by some to be questionable or unacceptable.”

When people speak in public, my ears are tuned to how they pronounced often. From what I hear, off-ten is the predominant form, and I sometime notice speakers switching from one pronunciation to the other. Perhaps there is even a pattern to the switching. That’s something to investigate down the road.

It is only a matter of time, I suspect, before Merriam Webster drops the obelus and recognizes often as one of those polyphonic words with alternative standard pronunciations. Like either, economics, apricot, and pajamas.

Feature image: “Hong Kong Park 44” by Wilfredor. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

October 2, 2021

10 books on palliative medicine and end-of-life care [reading list]

The demand for end-of-life care is growing with an ageing population. Each year an estimated 40 million people are in need of palliative care, 78% of whom live in low- and middle-income countries. In children, this increases to 98%. With the EAPC 17th World Congress Online starting on 6 October, and World Hospice and Palliative Care Day on 9 October, this reading list of recent titles can help you to reflect on palliative medicine as a public health need.

What’s in the Syringe?: Principles of Early Integrated Palliative Care by Juliet Jacobsen, Vicki Jackson, Joseph Greer, and Jennifer Temel

What’s in the Syringe?: Principles of Early Integrated Palliative Care by Juliet Jacobsen, Vicki Jackson, Joseph Greer, and Jennifer TemelWhat’s in the Syringe? teaches clinicians how to help patients live well and acknowledge the ends of their lives. It explores how patients can develop prognostic awareness, confront their hopes and worries, and see themselves with clarity and empathy. As patients use these skills, they improve their quality of life, helping them make informed medical and personal decisions as they approach end of life.

Read: What’s in the Syringe? Principles of Early Integrated Palliative Care

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (6th ed.) edited by Nathan I. Cherny, Marie T. Fallon, Stein Kaasa, Russell K. Portenoy, and David C. Currow

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (6th ed.) edited by Nathan I. Cherny, Marie T. Fallon, Stein Kaasa, Russell K. Portenoy, and David C. CurrowThe sixth edition of the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine takes us into the third decade of this definitive award-winning textbook. This comprehensive book covers all-new and emerging topics, updated to reflect major developments in the field. It covers the multi-disciplinary nature of palliative care, from ethical and communication issues, to the treatment of symptoms, and the management of pain. Plus, purchasers will get free online access for five years!

Read: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (6th ed.)

The Nell Dialogues: Conversation in Mortal Time by Richard P. McQuellon

The Nell Dialogues: Conversation in Mortal Time by Richard P. McQuellonNell M. came to her therapist with an unusual problem. She was disappointed that her metastatic breast cancer was not progressing as predicted. She had hoped breast cancer would lead to death, preventing her from witnessing her spouse’s mental deterioration from Alzheimer’s disease. The Nell Dialogues: Conversation in Mortal Time consists of twelve of Nell’s illness narratives that explore the challenges of managing the physical and emotional demands of cancer, relationship issues with family and health care professionals, and disturbing, anxiety-provoking thoughts as well as the mourning that accompanies the end of life.

Read: The Nell Dialogues: Conversation in Mortal Time

The Art and Science of Compassion, A Primer: Reflections of a Physician-Chaplain by Agnes M.F. Wong

The Art and Science of Compassion, A Primer: Reflections of a Physician-Chaplain by Agnes M.F. WongCompassion is an essential skill for those working in palliative medicine. Drawing on her diverse background as a clinician, scientist, educator, and chaplain, author Agnes M.F. Wong presents evidence that compassion is both innate and trainable. The training described helps individuals to develop cognitive, attentional, affective, and somatic skills that are critical for the cultivation of compassion. This book also contains striking illustrations to demonstrate key concepts.

Read: The Art and Science of Compassion, A Primer: Reflections of a Physician-Chaplain

Palliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual (4th ed.) edited by Susan MacDonald, Leonie Herx, and Anne Boyle

Palliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual (4th ed.) edited by Susan MacDonald, Leonie Herx, and Anne BoylePalliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual is an accessible and practical guide to providing high quality palliative and end-of-life care for patients and their families. It walks through the management of the most common situations found in palliative medicine, from diagnosis and managing symptoms through to grief and bereavement, using real patient case scenarios.

Read: Palliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual (4th ed.)

Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully: An Evidence-Based Intervention for Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers by Gary Rodin and Sarah Hales

Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully: An Evidence-Based Intervention for Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers by Gary Rodin and Sarah HalesManaging Cancer and Living Meaningfully, also known by the acronym CALM, is a brief supportive-expressive intervention that can be delivered by a wide range of trained healthcare providers as part of cancer care or early palliative care. This can help patients and families living with advanced cancer to live meaningfully, while also facing the threat of mortality.

Reflecting on the Inevitable: Mortality at the Crossroads of Psychology, Philosophy, and Health by Peter J. Adams

Reflecting on the Inevitable: Mortality at the Crossroads of Psychology, Philosophy, and Health by Peter J. Adams Death studies have, over the last twenty years, witnessed a flourishing of research and scholarship particularly in areas such as dying and bereavement, cultural practices, and fear of dying. But, despite its importance, a specific focus on the nature of personal mortality has attracted surprisingly little attention. This book focuses on the challenge of thinking and talking about one’s death and explores practical ways that engagement with one’s own death can be incorporated into daily life.

Read: Reflecting on the Inevitable: Mortality at the Crossroads of Psychology, Philosophy, and Health

Caring for the Family Caregiver by Elaine Wittenberg, Joy Goldsmith, Sandra L. Ragan, and Terri Ann Parnell

Caring for the Family Caregiver by Elaine Wittenberg, Joy Goldsmith, Sandra L. Ragan, and Terri Ann Parnell Family caregivers in chronic illness face high cost and poorly addressed needs. Caring for the Family Caregiver explores the four profiles of caregivers: the Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Lone caregiver. These care styles emerge from family systems with different patterns of conversational sharing and expectations of conformity. In this book, the authors deliver an unflinching gaze at the journey of the caregiver, through the lens of communication.

Read: Caring for the Family Caregiver

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (3rd ed.) edited by Richard Hain, Ann Goldman, Adam Rapoport, and Michelle Meiring

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (3rd ed.) edited by Richard Hain, Ann Goldman, Adam Rapoport, and Michelle Meiring The third edition of Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children identifies the medical, psychological, practical, and spiritual issues of caring for terminally ill children and their families. Comprehensive in scope, exhaustive in detail, and definitive in authority, this new edition has been thoroughly updated to cover new practices, current epidemiological data, and the evolving models that support the delivery of palliative medicine to children.

Read: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (3rd ed.)

Palliative and Serious Illness Patient Management for Physician Assistants edited by Nadya Dimitrov and Kathy Kemle

Palliative and Serious Illness Patient Management for Physician Assistants edited by Nadya Dimitrov and Kathy KemleThe first resource of its kind, Palliative and Serious Illness Patient Management for Physician Assistants provides a fundamental framework for physician assistants and physician associates to incorporate palliative care medicine, including end-of-life care, into their practice.

Read: Palliative and Serious Illness Patient Management for Physician Assistants

Explore our other titles in Palliative Medicine.

Is food addiction contributing to global obesity?

Right now, scientists are actively debating whether highly processed foods are addictive and whether this contributes to our continued failure to reduce obesity and diet-related disease around the globe. Two experts share their perspectives from different sides of the debate: Dr Ashley Gearhardt contends that these foods are addictive, while Dr Johannes Hebebrand argues that “food addiction” is not responsible for obesity rates.

Highly processed foods are addictiveDr Ashley Gearhardt: In our society, there is widespread knowledge that excess consumption of highly processed foods—like chocolate, pizza, and pastries—contributes to excessive weight gain and poor health. Millions of people try to cut down on highly processed food intake every year, but few find lasting long-term success. People fail to change their diet even when they are facing severe negative health consequences, like amputations, blindness, and early death. As highly processed foods spread around the globe, we see rates of obesity and disease rise with them.

What is it about highly processed foods that causes such a public health threat? Why are people unable to quit even when they are highly motivated to do so? Evidence is growing that highly processed foods are capable of triggering addictive processes akin to addictive drugs like tobacco. Our brains are designed to find high-calorie foods rewarding to ensure we survive the periods of famine. Carbohydrates (like sugar) and fat are high in calories and trigger the release of feel-good chemicals in the brain. For much of human history, the best hit of sugar we could hope for was finding some fruit. Fat would come from hunting down an animal or finding some nuts. While our brains are still in the Stone Age, the food industry has become skilled in jacking up carbohydrates and fats to unheard of levels and combining them with scores of additives to create unnaturally rewarding foods. These highly processed foods trigger reward responses in the brain that far exceed the levels associated with naturally occurring foods.

Addictive drugs and highly processed foods are created using very similar processes. For example, humans refine and process a naturally occurring substance (like a tobacco leaf) and process it into a product (like cigarettes) that has unnaturally high levels of a rewarding substance (like nicotine) and then add scores of additives (like ammonia and menthol) to further enhance it. These addictive drugs hijack the same reward centers of the brain that are so powerfully activated by highly processed foods. In fact, highly processed foods and addictive drugs are often consumed for the same reason—to experience a sense of pleasure and to reduce negative emotions. Whether it is a highly processed food or a drug, a substance can become so highly rewarding that it can trigger compulsive behavior (i.e., the person can’t stop even if they really want to). This is good news for industries that profit from selling these substances, but bad news for the rest of us.

Highly processed foods are not addictiveDr Johannes Hebebrand: The food industry thrives on selling its products. In an attempt to increase sales, thousands of novel food products are marketed annually. Foods need to be tasty and must in some way fulfill a market niche. A sufficiently large number of people need to be attracted to a specific food for it to stay on the shelves of a supermarket. Obviously, a cheap price guarantees a potentially large market. The operations of the food industry depend on cultural, social, economic, legal, regulatory, and political factors.

Should we use the term food addiction to explain overeating and obesity? Most people with obesity would definitely not view themselves as food addicts. Only a subgroup would answer affirmatively. Yes, they experience “grazing,” food cravings, and binge eating attacks, and cannot stop eating despite experiencing negative health implications and negative social consequences. They may report an eating behavior suggestive of tolerance and experience withdrawal symptoms.

But exactly to what are they addicted? There is no clear-cut evidence for one or more substances in food that elicit(s) a reward comparable to that achieved upon legal or illegal drug use. Try a limited amount of any drug—let’s say you deeply inhale cigarette smoke or drink a half a glass of wine. You will quickly experience an alteration in the way you experience yourself and your environment. This rapid onset, which if rewarding may represent the first initial step in the development of a drug addiction does not occur upon ingestion of food. People who view themselves as addicted to food will resort to many foods. They will not develop an addiction to a single food.

Why then do some people state that they are addicted to food? People with obesity require more food than others to maintain their body weight. They encounter difficulties in maintenance of a reduced body weight, which may be experienced as “food addiction.” Other people will experience a strong urge to overeat upon experiencing stress, anxiety or depression. Obesity usually runs in families with genetic factors accounting for the familial loading. In conclusion, the need or urge to overeat may subjectively be perceived as food addiction but in reality, depends on a range of genetic, physiological, social, and psychological reasons and not the intake of a particular substance.

The verdict? Further research requiredFood industry practices contribute to overeating and obesity; however, disagreement remains in determining whether highly processed foods meet the criteria to be considered addictive. Future research will help inform this debate and guide next steps on the best ways to promote healthy eating.

Featured image by RitaE via Pixabay

October 1, 2021

OUP celebrates their BMA 2021 Award winners

We are delighted to announce that the following OUP published titles have been presented with awards at this year’s British Medical Association Medical Book Awards.

BMA Medical Book of the Year 2021 and the Public Health category winnerHealth Equity in a Globalizing Era: Past Challenges, Future ProspectsAuthors: Ronald Labonté and Arne Ruckert

“In this tour de force, Labonté and Ruckert provide a comprehensive and critical view on major issues in globalisation such as trade and investment liberalization, labour migration, and neoliberalism. A must-read for all those working and studying global health.”

Devi Sridhar, Professor of Global Health, University of Edinburgh

Health Equity in a Globalizing Era: Past Challenges, Future Prospects examines how globalization processes since the on-set of neoliberalism affect equity in global health outcomes, and emphasises access to important social determinants of health. With a basis in political economy, the book covers key globalization concepts and theory, and presents a thorough background to the field.

Find out more about Health Equity in a Globalizing Era: Past Challenges, Future Prospects.

Winner in the Oncology categoryOxford Textbook of Cancer in Children seventh editionEdited by Hubert N. Caron, Andrea Biondi, Tom Boterberg, and François Doz

“This seventh edition has been thoroughly revised and updated, including brand new chapters on cancer immunotherapy in children, and cancer in adolescents and young adults, plus expanded treatment of tumours of the brain and central nervous system. The book primarily provides clear and up-to-date clinical guidance for use in treatment settings whilst offering a useful background to the biology of individual tumour types and the history of the development of specific treatments.“

Anticancer Research

With an international and multi-disciplined authorship comprising of paediatric oncologists, surgeons, radiotherapists, imaging specialists, psychologists, nurses, and many others, the text illustrates how the paediatric oncology community works globally and collaboratively in order to drive forward new therapies, build our knowledge of these diseases, and achieve the common aim of curing childhood cancer.

Find out more about the Oxford Textbook of Cancer in Children, seventh edition.

Winner in the Anaesthesia, critical care, and emergency medicine categoryA Field Manual for Palliative Care in Humanitarian CrisesEdited by Elisha Waldman and Marcia Glass

“The manual should serve as a reference document for policymakers seeking to promote the provision of palliative care in humanitarian crises, and project managers and health care practitioners seeking to improve the quality and holistic nature of care.”

James Smith, MBBS, MA, MSc, MSc, Journal of Palliative Medicine

As humanitarian aid organizations have evolved, there is a growing recognition that incorporating palliative care into aid efforts is an essential part of providing the best care possible. A Field Manual for Palliative Care in Humanitarian Crises represents the first-ever effort at educating and providing guidance for clinicians not formally trained in palliative care in how to incorporate its principles into their work in crisis situations.

Find out more about A Field Manual for Palliative Care in Humanitarian Crises.

Winner in the Hospital medicine categoryOxford Handbook of Palliative CareEdited by Max Watson, Stephen Ward, Nandini Vallath, Jo Wells, and Rachel Campbell

“This is a superb update to an already excellent book and especially for primary care, this is a great support for helping to manage a particular patient… This book is full of gems and offers excellent clinical support for a health care professional involved in providing direct patient palliative care.”

Dr Harry Brown, MBChB, Glycosmedia

Featuring an increased emphasis on non-malignant diseases such as dementia, this authoritative text combines evidence-based care with the bedside experience of experienced palliative care professionals to give the reader a complete overview of the physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of care for the end-of-life patient. Symptom management is covered in detail, with updated formulary tables and syringe driver protocols, and a new chapter on international perspectives to broaden the reader’s perception of methods for delivering end-of-life care.

Find out more about the Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care.

The reader observed: from Saint Jerome to Scott of the Antarctic

Across the centuries, in paintings and eventually in photography, one of the most common subjects for representation has been the reader.

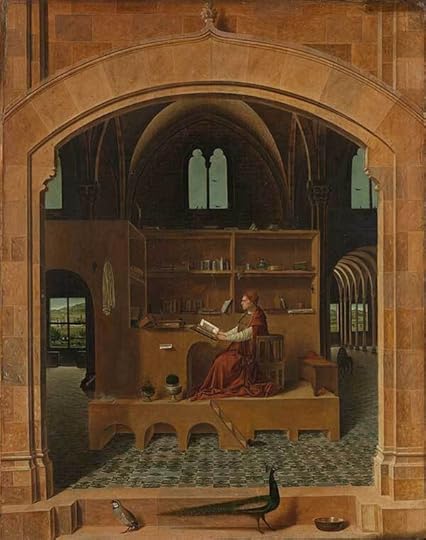

More than simply remarkable artistic objects in themselves, such images can reveal a great deal about contemporary attitudes and beliefs about books and reading. It was common for Renaissance artists to surround Saint Jerome with the equipment of learning—bookshelves, manuscripts, reading desk—in order to convey the image of the great scholar in the sublime isolation of his study, at once a repository for the synthesis of texts and at the same time a place for the production of new kinds of knowledge. Many of these images—take the iconic portraits by Albrecht Dürer and Antonella da Messina—present Jerome as an idealised reader, poring timelessly over his books in blissful isolation from the temporal world beyond the walls of the study.

Saint Jerome in his Study – Antonello da Messina

Saint Jerome in his Study – Antonello da Messina National Gallery – London, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The same potent imagery finds confirmation in later iconography. In the great period of British emigration, involving the displacement of millions of nineteenth-century Crusoes, the same iconography would prove particularly resilient as attempts were made to contain the experience of living at a colonial distance. It is something to which a number of illustrated editions of Crusoe–leaning over his Bible with his precious shelf of hard-won trophies behind him–pay uncanny tribute.

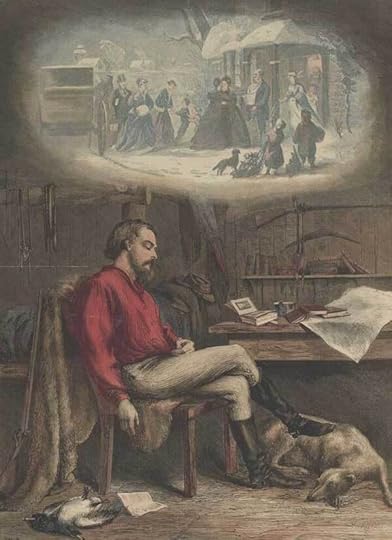

The Bushman’s Dream – Thomas Selby Cousins (Antique Map Room – Sydney)

The Bushman’s Dream – Thomas Selby Cousins (Antique Map Room – Sydney)As reproduced in Crusoe’s Books (Oxford 2021)

The artist Thomas Selby Cousins emigrated to New Zealand in the 1860s and then on to Victoria, where he was soon making himself a reputation for scenes of Australian life. The Bushman’s Dream (pictured here) was reproduced in the Illustrated Sydney News in 1869. If we compare it to early illustrations for Robinson Crusoe, we get a sense of how this visual tradition was now becoming enmeshed in a colonial context. Such images describe the way in which reading conjures up in the imagination other events and places prompted by its encounter with the printed word. The dreaming bushman, sitting at his makeshift table in the outback, is carried back in his mind to an English scene. In the isolation of his hut, it says, the printed word can bridge the tyranny of distance through a vicarious return to a familiar world.

Despite its celebration of reading as a lonely act, we should not forget that The Bushman’s Dream appeared in a mass circulation newspaper, not unlike the one that appears in Cousins’ image. By this time, these tokens of global communication were part of a vast network involving steam trains, cargo ships, and the telegraph lines lately introduced to the Antipodes. Three-volume novels, such as the one that sits in front of him, were by then being produced on industrial presses and regularly arriving in their thousands at Australian ports by steam packet.

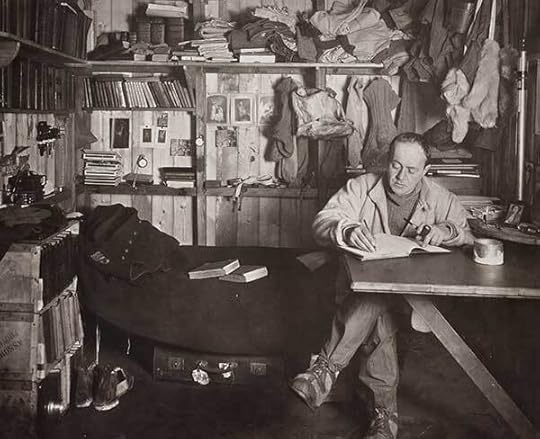

Robert Falcon Scott in the Winterquarters Hut – Herbert Ponting (Bonhams – London)

Robert Falcon Scott in the Winterquarters Hut – Herbert Ponting (Bonhams – London)As reproduced in Crusoe’s Books (Oxford 2021)

In the early twentieth century such images of the reader in exile were still finding purchase in even the most surprising of circumstances. In the fateful Antarctic spring of 1911, before Robert Falcon Scott and his sledging team set out on the journey from which they would not return, this same visual tradition was on Herbert Ponting’s mind as he posed the expeditionary leader for a remarkable portrait in his hut on Ross Island (above). Despite the apparently makeshift arrangement—books shelved in upturned packing crates, equipment hanging casually around, memento mori in the form of the pocket watch that the hangs beside the bed—what results is a tableau vivant, a pastiche of Jeromes.

Dora Thornton remarks on the way that such portraits, rehearsed from the sixteenth century on, were elaborately coded. The architectural setting, the choices of appurtenance, the very posture of the sitter, together convey messages about the status, education, and self-awareness of their subject. In this one moment, with his library ranged behind him, pen in hand, Scott takes his place in a lineage of individuals who had for generations taken refuge among their books. On the very edge of the known world, it seems to say, civilization continues, and the familiar practices of reading and writing make it possible.

Such images can be seen over the years as evidence of prevailing attitudes towards the history of reading. Even in an industrial age of print production the romantic appeal of the reader in solitary isolation is evident. The act of reading is both public and private at turns. Elizabeth Leane finds an analogy for Antarctic reading in the way that splinters of ice break away from an iceberg to form their own independent bodies:

text acted like ice in Heroic-Era expeditions, at times insulating expedition members from those around them, calving off little imaginative islands on which they could maroon themselves; and at other times solidifying the gaps between them.

In such instances, reading appeals to interiority, gesturing towards the privacy of cognitive experience; at others, it can be an explicitly social practice, mediating relations in ways that involve commonly held communal values.

Featured image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Saint Jerome in His Study (1514) by Albrecht Dürer. Bequest of Ida Kammerer, in memory of her husband, Frederic Kammerer, M.D., 1933.

September 30, 2021

Black History Month: celebrating 10 people who made British history

Each year during October the UK celebrates Black History month, an event which celebrates the achievements and contributions made to society by people of Black heritage and their communities and aims to educate all on the importance of Black history.

To observe this important event, we have curated a collection of Oxford Dictionary of National Biography articles exploring the lives of people of Black/African descent who had an impact on, or a connection to, the UK during their lifetime and the ways in which they made history.

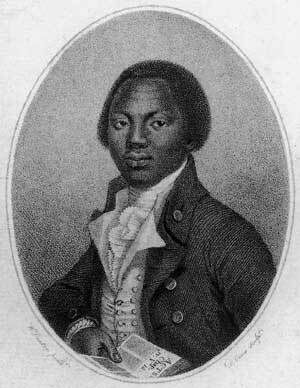

Olaudah EquianoOlaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa (c. 1745–1797)

Olaudah EquianoOlaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa (c. 1745–1797)Olaudah Equiano (renamed Gustavus Vassa—the name he used throughout most of his life) was an author and slavery abolitionist, and in the words of his own Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano born “in a charming vale, named Essaka,” most likely in present-day Nigeria. Equiano’s autobiography remains a classic text of an African’s experiences in the era of Atlantic slavery.

Read more about Olaudah Equiano in the ODNB

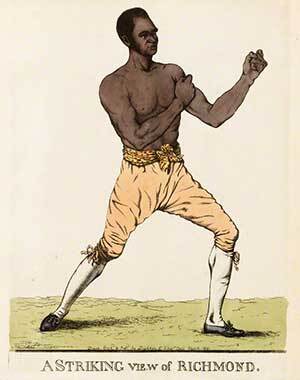

Bill Richmond (1763–1829) Bill Richmond

Bill RichmondBill Richmond was born in to slavery on 5 August 1763 on Staten Island, New York, and later became a pugilist in Britain. Earl Percy Hugh (later the second duke of Northumberland), in 1777 took Richmond to England, where he sent him to school in Yorkshire and later apprenticed him to a cabinet-maker in York. However, his career soon took a different turn.

Read more about Bill Richmond in the ODNB

William Craft (c. 1825–1900) & Ellen Craft, née Smith (1825/6–1891)William and Ellen Craft were both born in to slavery in Georgia, and married about 1847. In December 1848 the two made a daring escape to the north. In November 1850 the couple travelled to England—England was the safest, most logical haven; it had harboured fugitive slaves from America for many years. The couples many public lectures undoubtedly did much to further the abolitionist cause in both Britain and America.

Ellen Craft

Ellen CraftRead more about William Craft and Ellen Craft in the ODNB

Sarah Parker Remond (1826–1894)Sarah Parker Remond, born in Salem, Massachusetts, was a slavery abolitionist and doctor. In January 1859, Sarah Remond arrived in Liverpool and almost immediately began her work as an anti-slavery lecturer. Starting in Liverpool she lectured in Warrington, Manchester, London, and Leeds before the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 took her life and lectures in a new direction.

Read more about Sarah Parker Remond in the ODNB

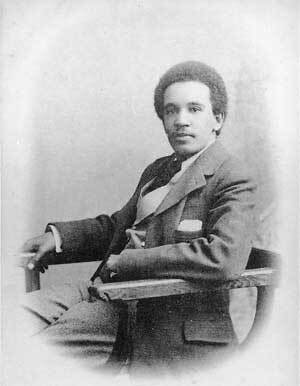

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912) Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-TaylorSamuel Coleridge-Taylor was and English composer and conductor. Having won a violin scholarship to the Royal College of Music for four years, he changed his mind and decided to study composition under Charles Villiers Stanford. Coleridge-Taylor was a man of gentle disposition and great personal dignity; his works enjoyed enormous popularity, and although his significance has come to be seen primarily as that of an icon of black success, his achievements as a composer of light orchestral and choral music were noteworthy.

Read more about Samuel Coleridge-Taylor in the ODNB

Rita Evelyn Cann, performing name Rita Lawrence (1911–2001)Rita Evelyn Cann, pianist and singer, was born on 24 January 1911 at Heathfield, Box Ridge Avenue, Beddington, Surrey. As one of the few visible black women in London society she was in demand as a singer and dancer for nightclubs and stage-shows, although neither was the true métier for an academically trained pianist and singer.

Read more about Rita Evelyn Cann in the ODNB

Rita Evelyn CannBeryl Agatha Gilroy, née Answick (1924–2001)

Rita Evelyn CannBeryl Agatha Gilroy, née Answick (1924–2001)Beryl Agatha Gilroy, teacher and author, was born on 30 August 1924 at Springlands, Berbice, British Guiana. Gilroy is remembered as a prolific author, psychologist, and London’s first black head teacher. In 1976 she published the autobiographical Black Teacher about her first years of teaching in London. This was one of the most interesting accounts of West Indian experience in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s.

Read more about Beryl Agatha Gilroy in the ODNB

Samuel Beaver “Sam” King (1926–2016)Samuel Beaver King was born at Priestmans River, Portland, Jamaica. King joined the Royal Air Force in 1944 and remained in the RAF until he was demobilized in 1947. In 1948 King returned to England as one of the passengers on the MV Empire Windrush. Known in Britain’s black community as “Mr Windrush”, in 1995 King, together with Arthur Torrington, set up the Windrush Foundation, a charitable organization dedicated to keeping alive the memories of Britain’s post-war Windrush generation.

Read more about Sam King in the ODNB

James Marshall “Jimi” Hendrix (1942–1970)James Marsall “Jimi” Hendrix, rock musician and songwriter, was enlisted in the US army in May 1961. After leaving the army he toured as a backing musician for Little Richard, Ike and Tina Turner, the Isley brothers, Jackie Wilson, and Sam Cooke. Hendrix went on to be part of several bands: Jimmy James and the Blue Flames, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Band of Gypsies, and The Cry of Love. Hendrix made London his home, and his influence was lasting and profound, and can be detected in many modern rock genres, including heavy metal and rap.

Read more about Jimi Hendrix in the ODNB

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi HendrixFeatured image by James Eades via Unsplash

September 29, 2021

Bimonthly etymology gleanings: September 2021

This past summer we experienced a severe drought. Even clover did not grow close to the place where I live. Nor did my correspondence with the world burst into bloom. Or perhaps the prevailing spirit of the time caused by the pandemic is at fault. I had to skip the August gleanings for lack of material, but by now I have enough tidbits to deal with. I’ll tackle them in the order of appearance, beginning with the earliest one.

The origin of flow. My indomitable opponent who keeps finding Greek sources of multifarious English words suggested pléo as the etymon of flow and predicted that I would reject his etymology. He was right. I will ignore his reference to the data that allegedly explain when the ancestors of Germanic-speaking people might pick up so many Greek words. That fact is irrelevant. But I hasten to note that the verb pléo meant “to swim; float; sail, navigate; progress; swing” (thus, “move along,” not “flow”) and had a short vowel in the root. The Old English for “flow” was flōwan (with long o). Pléo is an impossible cognate or source of flow.

By the way, among my correspondents one writes me almost after every post and shows that the words I discuss go back to Hebrew. I admire his ingenuity but stubbornly refuse to understand how the connections could come about, though he usually offers an explanation. I have seen works tracing English to Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Irish and have little enthusiasm for those theories (excuse my understatement). The real problem here, as I wrote two months ago, is that Latin fluere, which, in dictionaries is diplomatically said to have influenced the English verb, cannot be its cognate. One is forced to admit that fl- was a sense-symbolic group evoking the idea of moving with or along the stream. However, it seems that pl- could also refer to water: compare Greek plēo (cited above) and Latin pluit “it rains,” with immediately recognizable reflexes in the Modern Romance languages.

Väinamöinen. (By Robert Wilhelm Ekman via Wikimedia Commons.)

Väinamöinen. (By Robert Wilhelm Ekman via Wikimedia Commons.)One of the posts was about the words ninepence and nine. I made a ridiculous mistake and wrote that the attraction of 3, 7, and 9 might be in the fact that they were prime numbers. It is curious how we come up with such statements and remain blind to what we have produced. Don’t I know that 9 = 32? But numerology remains one of the toughest problems in folklore reconstruction. I am sure I am not the first to think so, but couldn’t the near-universal attraction of nine be explained by the mysterious fact that pregnancy lasts nine months? Even in such an archaic poem as the Finnish Kalevala the creation of the world lasts nine long epochs, at the end of which the great singer Väinamöinen is born.

In my discussion, of monkey as slang (monkey “mortgage”), I asked whether anybody had ideas about this strange sense of the word. But first I would like to call our readers’ attention to my post for 23 January 2013 with its punning title “Wrenching an etymology out of a monkey.” In it the origin of the word monkey was discussed, and I expressed my strong disagreement with the derivation offered in Online Etymology Dictionary, the only source of inspiration for hundreds of readers. But more important than the post are the numerous comments, some of which were added several years after the publication of that essay. I have written more than once that anyone who wishes to say something about an old post should add a comment after the most recent one, with reference to the original date, for otherwise, how can I know that some additions were made much later? I find one conjecture about the origin of monkey extremely interesting, but I stumbled on it by chance, while consulting my old post for the benefit of this one. The OED suggests that monkey business goes back to a phrase in Bengali. If so, our reader’s proposal that the word monkey is a borrowing from the Gypsy language gets additional support. Gypsy showmen often traveled with performing animals.

A monkey on the house. (Image by Devanath on Pixnio.)

A monkey on the house. (Image by Devanath on Pixnio.)In the comments on the recent post, it was pointed out that monkey lends itself well to such phrases as monkey’s uncle on account of the internal rhyme. The idea looks plausible. Another reader wrote that monkey was slang for £500 and suggested a possible connection. I also wonder: didn’t the proximity of the words money and monkey play a role in the coining of some words and phrases mentioned above?

Mother “sediment” (the post on homonyms). I agree with the comment that in mother of pearl, rather than in mother of vinegar, it is hard to decide which sense is meant. But that is probably the reason English and some other Germanic languages so readily accepted the clash of such seemingly irreconcilable homonyms. Mother as “the lowest layer” and mother as “producer” tend to get into each other’s way quite naturally.

The history of henchman. This was the subject of two consecutive posts. According to one suggestion, German Henker might be akin to the English word. Henker is related to the verb hang, that is, German hängen, and means “executioner.” However little we know about the early duties of the henchman (attendant? helpful servant?), those were not related to hanging, even if that servant was his master’s hanger-on. Dutch (om)heining (both were mentioned in a comment) has a transparent etymology: its root is related to English haw (remembered mainly from hawthorn and the name Hawthorn) and hedge, German Hecke, etc. In the same comment, Finnish hangas was mentioned. How could the English and the Finnish words interact?

Mr. Pickwick, Esq. (By Joseph Clayton Clarke via Wikimedia Commons.)

Mr. Pickwick, Esq. (By Joseph Clayton Clarke via Wikimedia Commons.)While discussing henchman, I mentioned the fact that no name of an English attendant or servant begins with horse or its synonym. Equerry came up in a comment. This word surfaced in English texts only in the sixteenth century and meant “royal or princely stables,” later “an officer in charge of such stables,” and still later “an officer of the royal household in attendance on a prince.” The root of the word can be seen in Medieval Latin scura ~ scuria “stable” (French écurie “stable”). The origin of the Latin word is unknown. The sense “officer in charge of stables” seems to depend on Old French escyer d’escuyrie “squire of the stables.” However convoluted the history of English esquire and its aphetic form squire may be, both words go back to the French phrase cited above, though the modern spelling and the pronunciation of the word were influenced (again influenced!) by Latin equus “horse.” Thus, the connection with horses is even here a product of folk etymology.

P.S. Walter W. Skeat (1887) on the state of the art: “The remarkable article on this word [icicle in Notes and Queries] is of great interest, as showing the determined way in which Englishmen prefer guess-work [sic] to investigation when they have to do with a word belonging to their own language. …when it comes to English, …speculation becomes a pleasure and delight to the writer. I can only say that some readers at least feel a most humiliating sense of shame and indignation at seeing such speculations in all the ‘glory’ of print.” (The great James A. H. Murray also used to say that he needed facts, not opinions.)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers