Oxford University Press's Blog, page 96

September 29, 2021

Take a virtual tour of America’s national parks: the Grand Staircase

Visitors to “scientific treasures” (sites with significant science content) often treat each site on its own. While this may be fine in many cases, in others it leaves the visitor without a complete picture of a certain aspect of science. Sometimes scientific treasures ought to be visited together with other, similar sites.

One example of a synergistic relationship between scientific treasures in the United States is the trio of National Parks: Grand Canyon, Zion Canyon, and Bryce Canyon. Here a visitor to all three is treated to a more complete picture of the West’s geology than from each park on its own. This triad of National Parks makes up the Grand Staircase, a formation of multiple cliffs retreating to the north.

Explore the images for the complete picture of the Grand Staircase formation:

[See image gallery at blog.oup.com]We hope that you have a chance to gain a fuller picture of the geology of the southwestern United States by visiting all three scientific treasures. Which other sites would you recommend viewing as a group to give visitors a more complete idea of their scientific significance?

September 28, 2021

What is public debt? [podcast]

What do you think of when you hear the term “public debt?” If you’re familiar with the phrase, you might think about elected officials debating budgets and how to pay for goods and services. Or maybe it’s a vague concept you don’t fully understand.

On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we are joined by two researchers who study the effects of public debt on economies.

Our first guest, Barry Eichengreen, is a professor of economics and political science at UC Berkeley and one of the authors of the newly published book In Defense of Public Debt. The book recounts 2,000 years of public debt history, putting contemporary political concerns in context. We spoke about how the role of public debt has changed throughout history and about misconceptions of public debt.

Our second guest, Jonathan Ostry, is Deputy Director of the Asia and Pacific Department at the International Monetary Fund. He recently co-authored an article on inequality and pandemics in the journal Industrial and Corporate Change. We spoke about how pandemics, especially COVID-19, can affect inequality and the role of public debt in these situations.

Check out Episode 65 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · What is Public Debt? – Episode 65 – The Oxford Comment Recommended readingTo learn more about public debt, check out Barry Eichengreen’s book, In Defense of Public Debt, exploring the history of public debt. Eichengreen is also the author of several other books, including The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era, Hall of Mirrors: The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the Uses-and Misuses-of History, and Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System.

You can also read Jonathan Ostry’s article “The rise in inequality after pandemics: can fiscal support play a mitigating role?” in the journal Industrial and Corporate Change. Ostry is also the author of Confronting Inequality: How Societies Can Choose Inclusive Growth from Columbia University Press.

Additionally, you can learn more about public debt and inequality in The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, an entry on “Post-Disaster Recovery and Social Capital” in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health, and an entry on “Sovereign Debt: Theory” in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance.

Featured image: Photo by @jaredmurray on Unsplash.

Does “overeating” cause obesity? The evidence is less filling

The usual way of thinking considers obesity a problem of energy balance. Take in more calories than you expend—in other words, “overeat”—and weight gain will inevitably result. The simple solution, according to the prevailing Energy Balance Model (EBM), is to eat less and move more.

Variations on this recommendation have been advocated to the public by government and professional health organizations for decades. For instance, the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans state, “Losing weight …requires adults to reduce the number of calories they get from foods and beverages and increase the amount expended through physical activity.” Health care providers almost invariably prescribe low-calorie diets (typically restricted in fat, the most calorie dense nutrient) and exercise to their patients.

In a new Perspective article in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, my 16 coauthors and I argue that viewing body weight control as an energy balance problem is fundamentally wrong, or at least not helpful, for three reasons:

1. It hasn’t workedThe obesity pandemic continues to worsen worldwide despite an incessant focus on calorie balance. Of particular concern is an emerging pandemic vicious cycle. Obesity is among the most important risk factors for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity, after advanced age. Conversely, the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate obesity, at least according to preliminary data in children. We need a more effective approach to weight control, now more than ever.

2. It doesn’t consider biologyThe relationship between energy balance and body fat reflects a law of physics (conservation of energy), providing no information about biology. It’s like considering fever a problem of “heat balance”—too much heat being generated by the body, not enough heat dissipated. Although technically true, this view doesn’t address the critical questions: what’s causing the fever and how we can cure it?

3. It can’t distinguish cause from effectThe law of energy conservation holds that the relationship between energy balance and body weight is inseverable but provides no information about the direction of cause and effect. During the growth spurt, an adolescent may consume hundreds of calories more than he burns. But does this “overeating” make him grow taller, or does the rapid growth make him hungry and eat more? Clearly, the latter … as no amount of “overeating” will make an adult grow any taller.

The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model (CIM), an alternative obesity paradigm considered in our Perspective, makes a bold claim: we’ve had it backwards all along! Overeating doesn’t cause obesity; rather, increasing body fatness—resulting from the effects of diet on hormones and metabolism—drives overeating.

The processed, rapidly digestible carbohydrates that flooded the food supply during the low-fat diet craze (think Fat-Free Snackwells Cookies) have raised insulin and suppressed glucagon levels. This highly anabolic hormonal state after a meal directs an excessive amount of incoming calories toward storage in fat tissue. As a result, too few calories are available to fuel the needs of metabolically active organs, like muscle. The brain responds by increasing hunger in an attempt to solve this “energy crisis”—driving us to consume extra calories to replace those being diverted into fat tissue. If we try to resist hunger, and cut back calories, energy expenditure (calorie burn) may slow down, explaining why so few people succeed on low-calorie diets over the long term. Eventually, biology trumps willpower.

If the CIM is right, then a focus on what you eat will be more effect than on how much. By replacing processed carbohydrates (white bread, white rice, potatoes, cookies, cakes, sugary beverages) with healthy high-fat foods (nuts and nuts butters, full fat dairy, avocado, oil olive, even dark chocolate), we can lessen the drive to “overeating” at the source, by shifting calories away from deposition in fat tissue. As a result, hunger naturally decreases, and weight loss may occur more easily, like the reduction in body temperature that follows treatment of fever with aspirin. For individuals with more severe metabolic dysfunction, such as type 2 diabetes, more intensive carbohydrate restriction (such as a ketogenic diet) may be optimal.

Although rapidly digestible carbohydrates (technically, high-glycemic load) play a key role in the CIM, the model provides a way of understanding how many dietary factors (amount and type of protein, type of fat, micronutrients fiber, pre- and probiotics) and other environmental factors can influence body fat storage, other than directly through “overeating.”

Although the CIM is not proven, our Perspective highlights the extensive supportive basic and clinical research that already exists. We argue that the CIM better reflects a century of accumulated knowledge on the biology of obesity than the EBM. And we call for better funding to conduct the definitive research. As highlighted in our Perspective, versions of this debate have raged for a century!

Featured image by Rod Long via Unsplash

September 27, 2021

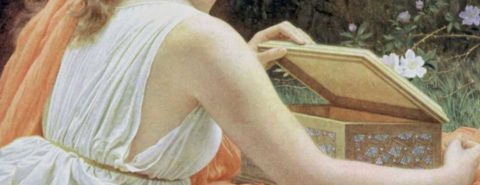

Can interpretations of the Pandora myth tell us something about ourselves?

According to the early Greek poet Hesiod (ca. 700 BC), the primordial human community consisted only of men, who lived lives of health and ease, enjoying a neighborly relationship with the gods. That relationship soured, however, after Prometheus deceived the Olympian gods for the benefit of mankind. In retaliation, Zeus schemed to punish men by inserting woman into their community. At Zeus’s instruction, Hephaistos fashioned a maiden from earth, Athena dressed her, the Graces and Peitho (Persuasion) ornamented her with necklaces, the Hours placed a garland of flowers on her head, and Hermes put lies and deceit in her breast, gave her a voice, and named her Pandora (All-Gift), since all the gods had gifted her. Zeus then directed Hermes to take this irresistible creation to a certain Epimetheus, who accepted her. Pandora presently took the lid off a great jar, scattering countless spirits of misery, including diseases and toil, among mankind. The only spirit to remain in the jar was Hope, since Zeus had Pandora replace the lid before she escaped (Works and Days 53-105).

The first woman is made to be physically attractive in order to induce a human male to accept her. That man is the foolish Epimetheus (Afterthought), brother of Prometheus (Forethought). In addition to making the primordial community gendered, the maiden releases from a mysterious jar numerous evils in the form of silent supernatural beings, who now become part of the world, introducing mortal men for the first time to labor and sickness, including fatal illnesses, and so to death. Hesiod does not say where the jar came from, but since he calls it a pithos, a large storage vessel some five or six feet in height, Pandora will not have brought it with her; indeed, she will not have carried it at all. Notice that in this earliest text of the myth, the vessel is a jar, not a box. The international expression “Pandora’s box” goes back to a mistranslation by Erasmus of Rotterdam, who rendered Pandora’s pithos “jar” as pyxis “box” when he retold the myth in Latin in 1508.

A similar narrative is found elsewhere in Greek literature, not as a myth but as an Aesopic fable. In this form of the story, the character who lifts the lid off the jar is described simply as an anthropos “person” (that is, a human but not specifically female or male), and the jar contains good things rather than evils. According to the fable, Zeus once gathered together everything good, placed it in a pithos, put a lid on it, and set it down beside an unnamed human being. Eager to know what was inside, the person opened the jar, with the result that the good things flew up to the habitation of the gods; only Hope remained below, for it was still in the jar when the anthropos replaced the lid. So only Hope remains among humans, promising us each of those good things that escaped (Babrios Fables 58).

The basic message of the myth and the fable is the same: at some time in the past humans enjoyed conditions of ease like that of the gods, but thanks to the actions of a particular human all that changed such that mortals now have lives of misery, though we carry on, motivated by hope. The difference between the two forms of the story is that one image presents the conditions of human life in terms of evils (there used to be no evils, and now there are), whereas the other presents it in terms of good things (there used to be all good things, and now there are not). Depending upon which image is employed, the jar either shields humans from its contents or makes them available. Strictly speaking, the motif of Hope makes good sense only in the second kind of jar, the jar of blessings, for only in this form of the story do things within the vessel affect persons outside of it. Although Hesiod’s intended meaning is clear, his narrative somewhat confusingly mixes the two images.

Why does Pandora open the jar at all? Hesiod says only that, as she lifts the lid, “she ἐμήσατο grievous cares for human beings” (Works and Days 95). The verb he employs can suggest a range of agency from “devised,” implying knowledge and intent, to simply “wrought,” suggesting innocence or even nothing at all. So, Pandora may act from malice, indifference, curiosity, or something else, but the poet does not specify, probably because what was important to him was, not why she releases miseries into the world, but that it is a woman who does so. In any case, all modern attributions of motive to Pandora are necessarily conjectural, possibly revealing more about the attributor than about the maiden.

Feature image: “Pandora’s box” by Charles Edward Perugini, via Wikimedia Commons

September 26, 2021

Stereotypes of atheist scientists need to be dispelled before trust in science erodes

Coping with a global pandemic has laid bare the need for public trust in science. And there is good news and bad news when it comes to how likely the public is to trust science. Our work over the past ten years reveals that the public trusts science and that religious people seem to trust science as much as non-religious people. Yet, public trust in scientists as a people group is eroding in dangerous ways. And for certain groups who are particularly unlikely to trust scientists, the belief that all scientists are loud, anti-religious atheists is a part of their distrust. Our research with atheist scientists in the US and UK shows that atheist scientists are radically different than the loudest voices would lead us to believe.

A small but vocal subset of atheist scientists (think Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion) speak derisively about religion and give the false impression that most scientists are anti-religious. It is thus no surprise that many religious individuals believe scientists are anti-religion. (Furthermore, given that women and communities of color are more likely to be religious than white men—who predominate in science—it is unsurprising that the scientific community struggles to recruit and retain individuals from such backgrounds). Our data, however, turn the notion of hostile atheists on its head. After surveying 1,293 atheist scientists at universities and research institutes in the US and the UK, and conducting 81 in-depth interviews with survey participants, we identified three groups of atheist scientists. To be sure, we did encounter some anti-religion sentiment among one group we refer to as modernist atheists. These are scientists who are not part of religious institutions and believe there is no way of knowing outside of science. A subset of modernist atheists are concerned about religion’s potential impact on the promotion of cognitive rationality in society. And more than two-thirds do view the relationship between science and religion as one of conflict. But conflict does not necessarily entail personal hostility. Indeed, many modernist scientists espoused positive views of religion’s role in society and rejected the discourse of vocal anti-religious atheists as hyperbolic and damaging to science.

Another group of atheist scientists we identify as culturally religious, (less than 40% of whom embrace the conflict perspective), who value including elements of religion in their day-to-day lives through social ties such as marriage to religious individuals, the religious schooling of their children, or formal religious affiliation—despite these culturally religious atheists own irreligion. Many of these atheists see value in being a part of a religious community. The lack of anti-religious sentiment among other culturally religious atheists is observed in their commitments and ties to religious individuals and organizations.

A third group, spiritual atheists, we label as such because they construct alternative value systems—oriented around the transcendent—but without belief in God or religious affiliation. For these scientists (again, less than 40% of whom embrace the conflict perspective), spirituality often imbues wonder and motivates their work. Spiritual atheist scientists rarely espouse negative views of religion, perhaps in part because they see limits to what science can explain and appreciate that both religious and non-religious forms of understanding can inform ethics, morals, and other non-material dimensions of the world.

These patterns, coupled with our previous work that demonstrates that more scientists are religious than most people think, indicate that most scientists—even atheist scientists—are not hostile to religion. They also suggest that science may have a marketing problem. By one logic, the public sphere entails a marketplace of ideas where multiple views of an issue can be presented for debate. At present, a small but vocal group of anti-religion atheist scientists maintains a monopoly over discourse related to science and religion. Unless a broader variety of both atheist and religious scientists begin to contribute to such conversations, the erosion of trust in scientists is unlikely to change.

Feature image by ThisisEngineering RAEng from Unsplash

September 25, 2021

Keeping the peace: property and community

In 1975, the State of California passed a law that allows union organizers to enter agricultural facilities for up to three times a day, one hour at a time, and up to 120 days per year. Several farms challenged the law as a violation of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution saying that it was a per se physical taking of their private property without just compensation. A lower court ruled against the growers and the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit denied a rehearing. The case, Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, then went to the Supreme Court, which, on 23 June 2021, ruled 6-3 in favor of the growers. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts held that “a physical appropriation is a taking whether it is permanent or temporary,” for, as he explained, “[t]he right to exclude is ‘universally held to be a fundamental element of the property right’” in land.

When we think about the origins of property, we naturally, like Jean-Jacque Rousseau, think of land, of “the first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him.” With typical pithy flair, the property law scholar Carol Rose poses the problem as “trac[ing] out what seems to be property’s quintessential moment of chutzpah: the act of establishing individual property for one’s self simply by taking something out of the great commons of unowned resources.” The seventeenth-century Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius frames the origin of property as the successor era to an imagined “golden age” when “in the eyes of nature no distinctions of ownership were discernible.” The common supposition is that at some point in time some human beings were the first creatures to declare something to be “Mine!,” and that something was a resource lying free for any taker.

At the core of this mythical “frontier” notion of property is the idea that property is necessarily based on violence or the threat of violence. After I put a fence around the land, the image of property is me sitting on the front porch with a loaded shotgun threatening to use violence against anyone who dares enter without my consent. It’s a “me against the world” mentality that equates a claim of property with the right to use physical force to exclude others from using it. It’s also a fundamentally anti-social view of humanity that property violates the liberty of others. Maybe the quintessential moment of property is not about grasping something lying free for any taker. And maybe it’s not based ultimately or purely on an individual exercising coercion and violence against all others. Perhaps the origins of property lie somewhere else: in the very human act of creating something new, something that did not previously exist in the great commons of nature. A piece of raw land becomes a strawberry farm.

Thinking about the origins of property in this way allows us to consider that the value of property lies within the fundamentally humane confines of a community—of other people and me, not other people or me. This is true of property all over the world. Not every human community has property in land, but all human groups have property in tools, utensils, or ornaments. I did say “all.” Every human community distinguishes things that belong to the individual from things that belong to others. However minimal it may be, there are some things about which only a particular individual can say, “This is mine.” Not all spears or ceremonial ornaments are the same. Like lacrosse sticks and Hello Kitty backpacks, the custom is such that there is but one individual who can wield or wear it.

Property is not merely my claim “That spear is mine,” nor just about me confronting an interloper who tries to grab my spear. Property is embedded as custom in the community that surrounds me. To claim property in anything is to have learned from my mentors when other people can know that what I say about such a thing is true. I draw upon the approval of my community to make such a claim. It is a “me with my community” mentality to say “Hey, that spear is mine!”

My community backs me up because I respect their claims to the property in the spears they create. We honor each other’s claims to the things we individually create because doing so prevents quarrels and violence in our community.

That’s not to say we are a community of angels. Human beings are an insolent, rapacious breed, particularly when resources are scarce. But it is a mistake to confuse human fallibility for the ultimate explanation of property. That people quarrel and dispute claims of property does not mean property is inherently violent. When someone comes to take a spear I claim as mine, the question for the community is whether my claim is indeed true, for I too could be in the wrong or simply mistaken. Moreover, even if the community punishes the interloper for taking my spear without my consent, the ultimate explanation of property is still not violence. It is peace for the rest of the community who says to me, “That spear is yours.”

In 1975, the State of California unintentionally created conflict when it allowed union organizers in October 2015 to burst into a Cedar Point Nursery facility with bullhorns. The reason why the Constitution requires just compensation for physical takings of property is that it maintains peace. In Cedar Point the Supreme Court ruled that the government cannot authorize people to enter an owner’s land without paying just compensation. In other words, it ruled for keeping the peace, here and now and for the unforeseeable future.

September 23, 2021

Five models of peer review: a guide

Identity is inherently entwined within the peer review process by virtue of the numerous models available, which results in varying levels of anonymity for individuals involved in the process. This blog post looks at five peer review models currently in use, describing what they mean for authors, reviewers and editors, and examines the various benefits and consequences of each.

Single Anonymised Peer ReviewWe start with the most commonly used and well-established peer review model. In Single Anonymised Peer Review the author’s identity is known to both the editor and the reviewers, with the reviewers’ identities remaining hidden from the authors. This is the simplest model to implement and, because it is well-established, is easily understood by all of the individuals involved in the process. Reviewers are protected and can feel comfortable being candid in their assessments should constructive negative feedback be required. However, authors are not protected from any conscious or unconscious biases the reviewers or editors may hold, and decisions could be influenced by judgements based on their name, institution, or other identifying information.

Double Anonymised Peer ReviewIncorporating an additional layer of anonymity, Double Anonymised Peer Review ensures that the author’s identity is hidden from reviewers and that reviewer identities are hidden from authors. The journal editor is the only individual with oversight of author and reviewer names, protecting both the authors from potential bias during the review process, and reviewers from any potential repercussions from making less favourable comments. This can be particularly important for early career researchers who are reviewing the work of influential senior researchers in the field.

Triple Anonymised Peer ReviewJournals using the Triple Anonymised Peer Review model ensure that author identities are hidden from the journal editor as well as from reviewers, and reviewer identities remain hidden from authors. The editorial office has oversight of all reviewer and author names, but the decision-making editors do not.

Unfortunately, anonymity is not guaranteed in either double or triple anonymised peer review: it can be easy for reviewers to guess an author’s identity should they work in a particularly niche field, or even for authors to guess a reviewer’s identity based on their comments, and there is an additional burden for authors and the editorial office staff to ensure that all work is sufficiently anonymised at the outset before it is submitted for peer review.

Non-anonymised Peer ReviewAlso known as Open Peer Review, in journals using this model the author, reviewer, and editor identities are known and shared between all parties; this model maximises openness and transparency. Everyone involved in the process is incentivised to provide fair, justified, and constructive comments due to the public and open nature of the model, and reviewers can receive public recognition for the report they have provided—via services such as Publons, for example. This model can also facilitate additional dialogue between parties, for example in a collaborative peer review process where the reviewers and editor discuss the paper and provide a single agreed list of comments. This can be of great help to authors and avoids conflicting comments for improvement being provided by individual reviewers and editors.

Transparent Peer ReviewThe Transparent Peer Review model can vary depending on how individual journals choose to operate. The review process itself can be conducted in any of the methods described above (Non-, Single, Double, or Triple Anonymised), but once a paper is accepted the reviewer comments are published alongside the final manuscript. A combination of the original submission, author’s response to reviewers, and editor comments may also be published, providing additional context for the article and demonstrating the positive improvements which have been made as a result of peer review.

This model increases transparency of the peer review system whilst allowing protection of the identities of reviewers and authors before acceptance (depending on the review model used) and can be flexible according to the priorities of authors, reviewers and editors. Some journals using this model offer optional Transparent Peer Review without it being required; authors have the option to publish the reviewer comments they received during the peer review process, and reviewers have the option to reveal their identity and receive public recognition for their work on that particular manuscript.

Whilst the Transparent Peer Review model can provide the flexibility for authors and reviewers to choose their own preferences, it can also add complexity for journals, authors, and reviewers. It is vital to ensure absolute clarity for all parties involved around how the peer review process will operate pre-acceptance, and to set out clear policies around what exactly will be made available on publication of the final manuscript.

Oxford University Press publishes across a very broad range of disciplines in Arts and Humanities, Social Sciences, Law, Science, Technology and Medicine. As such, we recognise that we cater to a diverse authorship, with peer review preferences, norms and expectations that differ depending on the field. We therefore offer a range of peer review models across our journals, in order to best meet the needs and expectations of our authors—each journal’s author guidelines contain information on which peer review model it operates under. We continue to experiment with new innovations and carefully consider models which will benefit our authors and the broader research community.

From immigrants to Americans: race and assimilation during the Great Migration

In recent decades, immigration has reshaped the demographic profile of many Western countries. The economic and political effects of immigration-induced diversity have been investigated by a growing number of studies across the social sciences. Specifically within political economy, most studies have focused on the impact of immigration on the preferences and behavior of the native population (see the recent review by Alesina and Tabellini for a summary). Yet, while population inflows can have broader effects on receiving societies, including on earlier generations of migrants, such effects have remained relatively understudied. Do new groups facilitate the incorporation of existing minorities by redirecting prejudice away from the latter, or do they hinder it by fueling native-born backlash against all minorities? More broadly, how does the arrival of a new minority group affect the majority’s attitudes towards other minorities and shape boundaries across social groups?

Building on insights from social psychology, specifically self-categorization theory, we devised a conceptual framework for identifying how ingroup members (i.e., native whites) discriminate against outgroups (i.e., racial and ethnic minorities). The latter can partly counteract discrimination by exerting costly effort to assimilate. Discrimination by the ingroup decreases in line with the perceived distance of outgroup members, which is context-dependent. Figure 1 depicts this framework graphically. Context-dependence follows the meta-contrast principle, which posits that categorization minimizes within group differences and maximizes across group differences. According to our framework, when an outgroup of high actual distance to the ingroup appears, the perceived distance of existing outgroup members drops. This, in turn, results in recategorization of some outgroup members to the ingroup. In anticipation of higher acceptance, outgroup members also adjust their assimilation effort—sufficiently close outgroup members can enter the ingroup with lower effort levels, while more distant outgroup members may increase their efforts.

Building on insights from social psychology, specifically self-categorization theory, we devised a conceptual framework for identifying how ingroup members (i.e., native whites) discriminate against outgroups (i.e., racial and ethnic minorities). The latter can partly counteract discrimination by exerting costly effort to assimilate. Discrimination by the ingroup decreases in line with the perceived distance of outgroup members, which is context-dependent. Figure 1 depicts this framework graphically. Context-dependence follows the meta-contrast principle, which posits that categorization minimizes within group differences and maximizes across group differences. According to our framework, when an outgroup of high actual distance to the ingroup appears, the perceived distance of existing outgroup members drops. This, in turn, results in recategorization of some outgroup members to the ingroup. In anticipation of higher acceptance, outgroup members also adjust their assimilation effort—sufficiently close outgroup members can enter the ingroup with lower effort levels, while more distant outgroup members may increase their efforts.

We tested the predictions of the model in the context of US history. Between 1850 and 1915, during the Age of Mass Migration, more than 30 million European immigrants moved to the US, where the foreign-born share of the population peaked at 14%. Like today, concerns about immigrant assimilation were widespread, and nativism and anti-immigration sentiment dominated the political debate. Opposition was particularly strong against Eastern and Southern Europeans, who were religiously and culturally different from white Anglo-Saxons. Despite such antagonism, early-twentieth-century immigrants, albeit at varying rates and less quickly than originally thought, eventually assimilated economically and culturally into American society fueling the myth of the American melting pot.

We tested the idea that the migration of another group—African Americans—played a key role in the assimilation of European immigrants. While this idea has been suggested by historians, it has never been formally tested before. From 1915 to 1930, approximately 1.6 million Black people migrated for the first time from the US South to cities in the North and West. This unprecedented migration episode—termed the First Great Migration—was triggered by wartime manufacturing needs in the North during WWI, as well as declining agricultural productivity and racial discrimination in the South. To identify the effects of Black in-migration on the assimilation of Europeans, we compare immigrants across Northern cities that received different numbers of African Americans, before and after the Great Migration. To deal with the possibility that Black individuals might have sorted into more rapidly growing (or declining) cities where immigrants were assimilating at different rates, we follow the migration literature to predict Black in-migration. This strategy exploits geographic variation in historical (pre-Great Migration) settlements of Black Americans born in different Southern states and living in different non-Southern cities. It combines such settlements with differential emigration rates of African Americans across Southern states from 1910 to 1930.

Relying on the full count US Census of Population, we find that immigrants living in cities that received more Black migrants between 1910 and 1930 were more likely to become naturalized citizens—a proxy for assimilation effort—and to marry a native white spouse of native parentage—a proxy for successful integration. Reassuringly, neither naturalization rates nor intermarriage were trending differentially across Northern cities before the First Great Migration. This suggests that our findings cannot be explained by Black migrants systematically settling in cities where European immigrants were assimilating at a faster rate.

Our research also investigates the mechanisms through which Black in-migration favored the assimilation of European immigrants. Native discrimination against immigrants decreased following the arrival of Black migrants, as group boundaries were re-defined in terms of skin color rather than language or religion. Data from the historical press reveals that, in cities that received more African Americans, local newspapers were less likely to mention words reflecting fears of immigration or concerns about immigrant assimilation. Notably, the Great Migration reduced the frequency of disparaging ethnic stereotyping, such as the association of Italians with the word “mafia” or Irish with the word “violence” or “alcohol.” The drop in negative stereotyping against European immigrants was accompanied by an increase in the probability that non-Southern newspapers described African Americans using negative terms.

Consistent with our theoretical framework, assimilation exhibited an inverted U-shape. Immigrant groups that experienced the largest assimilation response were those at intermediate cultural distance (proxied using linguistic and genetic distance) from native whites. As predicted by the model, those groups were sufficiently distant to be excluded from the ingroup before the inflow of Black migrants, but close enough to benefit from the arrival of the new outgroup. Groups such as the Chinese—too distant to be recategorized as white even after the Great Migration—saw no changes in their assimilation outcomes.

Our model also predicts that assimilation effort and assimilation success should peak at different points of the distribution of immigrant distance from natives. As before, the data support this idea. Immigrants who were culturally closer to natives (e.g. Northern and Western Europeans) were more likely to successfully assimilate in response to the Great Migration, and to do so with lower effort. Such groups experienced higher intermarriage rates—an outcome heavily influenced by the preferences of native society—but lower naturalization rates—a measure less impeded by host society barriers and more reflective of immigrant effort. The pattern is reversed for “new source” immigrants, such as Eastern and Southern Europeans. These groups, which were culturally more distant from native whites, showed the largest increase in their efforts to assimilate through naturalization. However, such efforts did not necessarily translate into successful assimilation in the form of successful intermarriage.

We can rule out the possibility that social assimilation resulted from certain groups (i.e. Northern and Western Europeans) benefitting from Black inflows due to labor market complementarities, and others (i.e. Eastern and Southern Europeans) suffering due to economic competition. In contrast with effects on social outcomes, which depended on the cultural distance of different immigrant groups from native Anglo-Saxons, the economic effects of the Great Migration were homogeneous across immigrant groups: all European immigrants, regardless of their country of origin, left the “immigrant-intensive” (and low paying) manufacturing sector at similar rates. This provides additional evidence that native attitudes played a central role in driving our results.

Our results show that inflows of one group can change the salience of particular attributes, influencing ingroup members’ perceptions of previous outsiders. This, in turn, can have important implications for immigrant assimilation. Research has examined the effects of inclusive or assimilationist policies on the integration of immigrants. Our work instead suggests that, especially in multi-ethnic and multi-cultural societies, much assimilation happens organically through the interaction of new and old minority groups.

The First Great Migration in the US may have unique features. However, existing evidence suggests that the mechanisms we identified in this specific context might apply in a variety of settings. In a related study, Fouka and Tabellini document that the 1970 to 2010 Mexican immigration to the US ameliorated whites’ attitudes towards African Americans and reduced hate crimes against Black people. These patterns are consistent with immigrant origin becoming more salient relative to race, thereby improving the status of Black Americans. The framework put forward in our work highlights the multidimensional effects of immigration for social boundaries in diverse societies.

Elderspeak: the language of ageism in healthcare

Scene: A long-term care facility. A nurse is helping an older resident with dementia as she takes a shower.

Nurse: “There we go, sweetie, just lift your arm up a little bit for me. We’ll get you all cleaned up in no time, won’t we?”

Resident (swatting away the nurse’s hand):“Get outta here—I don’t want your help!”

This fictional scenario exemplifies the nature of elderspeak, or babytalk to older adults, and the typical context in which it occurs—used by younger caregivers providing care to older adults. The example also illustrates a potential side-effect of elderspeak: resistance to care by persons living with dementia.

The past 40 years have seen a growing awareness of elderspeak, its characteristics, antecedents, and consequences. But research efforts have been limited by a lack of coherence. The concept, historically referred to as baby-talk, secondary baby-talk, infantilization, patronization, and over-accommodation, has been studied using a range of experimental paradigms by ethnographers, psycholinguists, and healthcare professionals. Upon reviewing four decades of elderspeak research, we propose a new and comprehensive definition of elderspeak that aims to capture its core attributes, its primary antecedents, and its potential consequences:

Elderspeak is a form of communication over-accommodation used with older adults that:

is evidenced by inappropriately juvenile lexical choices and/or exaggerated prosody;arises from implicit ageist stereotypes;carries goals of expressing care, exerting control, and/or facilitating comprehension; andmay lead to negative self-perceptions in older adults and challenging behaviors in persons with dementia.To elaborate, elderspeak is comprised of modifications in both linguistic and paralinguistic domains. Examples of linguistic attributes, including childish terms, diminutives, simplified sentences, and tag questions, have been reported globally. For example, in German nursing homes, staff urged residents to “wash the little bottom” while assisting with bathing. Staff in Swedish nursing homes administered medication with the phrase “here comes little pills on the spoon here.” In Singapore care homes, staff equated residents to children, saying “just like little kids, we should only play after finishing our homework.” The hallmark paralinguistic feature of elderspeak is a change in prosody, including excessive pitch modulation and a sing-song intonation that matches the tone and pattern of communication in nursery schools.

Elderspeak is often produced with the goal of appearing caring while also exerting control. Care interactions recorded in a South African nursing home documented a nurse instructing a resident to “move up, be a darling.” Similarly, a carer in an adult day center in the US was observed telling a resident, “Sweetie, you need to sit down until I’m finished.” In healthcare settings, control by staff may be required in order to achieve health goals, especially for frail older adults. When staff want to soften their controlling directives, they may adopt excessively “caring” language. Issues arise when the language is perceived negatively. Cognitively intact older adults generally perceive elderspeak to be patronizing and infantilizing, and believe that those who use elderspeak are less respectful, nurturing, and competent. Even more concerning, elderspeak has been demonstrated to double the probability of resistiveness to care by nursing home residents with dementia. When elderspeak is reduced by nursing home staff, resistiveness declines, which also reduces the need for chemical restraints.

Why, then, do care providers use elderspeak if it is perceived as patronizing and elicits potentially harmful behaviors in persons with dementia? The answer lies in the ubiquitous ageism embedded in societal views of older adults. Although often implicit, the message typically portrayed in the media is that elders are as incompetent and dependent as children. The emergence of the baby-boomers as senior citizens has begun to change this picture. But positive portrayals of aging tend to set a lofty standard of “successful aging” enacted by improbably young and attractive older adults, with the implication that anything else constitutes unsuccessful aging.

Although the examples of elderspeak cited here occurred in healthcare contexts, it is important to note that elderspeak extends beyond healthcare settings. Children as young as seven years old have been found to adopt attributes of elderspeak when speaking to older adults. By adulthood, age-related stereotypes are so thoroughly entrenched that even the most considerate caregivers may be susceptible to implicit ageism. Thus, behaviors stemming from ageism are common in healthcare, and elderspeak is an example of how communication that is meant to be caring can actually come across as prejudiced to older adults. To combat elderspeak, a systemic shift in our attitudes toward older adults is needed. In the shorter term, intervention through policy change and education can help reduce the implicit bias of ageism that leads to elderspeak.

September 22, 2021

Ice: a forlorn hope

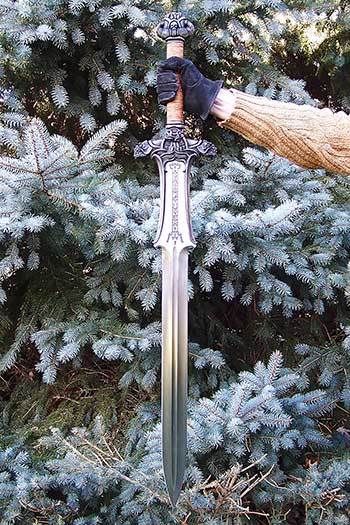

Why a forlorn hope? Because all the Germanic-speaking people had the same word for “ice,” and yet we don’t know where it came from. Some of our readers may be aware of the statement that the Eskimo (Aleut) language has fifty (just fifty!) words for “snow.” This statement aroused a long controversy, which is none of our business, but, in principle, it should not surprise anyone that the better we are acquainted with an object, the more nuances we can recognize in it and the more words will or may be coined to describe its features: compare the endless number of color words in a painter’s vocabulary. Icelandic, a language spoken by the people who have dealt with cold since the day they settled in their country (nor were they ignorant of it in Norway!), distinguishes between “ice in general,” “hollow ice,” “ice on a skating rink,” and “ice as frozen ground.” We tend to believe that the ancient Germanic word ice, from īs, was a generic term denoting “frozen water.” This belief may be true but may be an illusion.

Not exactly an icicle. (Image by Alto Crew via Unsplash)

Not exactly an icicle. (Image by Alto Crew via Unsplash)The speakers of Medieval Icelandic and German did not ponder the etymology of īs, but they heard that īs sounded very much like īsarn, their word for “iron.” (Though the Old English for “iron” was īren, the protoform mut have had s in the root.) For a substance to be called “ice,” it had to be cold, hard, and under some circumstances glittering or gleaming. Old Icelandic poetry testifies to an almost complete merger of íss “ice” and ísarn “iron, metal” in some contexts. In that poetry, another word for “ice” (svell “hollow ice”) functioned as a synonym for “a gleaming sword.” Curiously, in Old English, the word ice especially often occurred in connection with melting, and in the poetry of that period, swords tended to melt (this once happened to Beowulf’s weapon)! Scyld Scefing, the great ancestor, extolled in Beowulf, died and was given a splendid sea burial. His ship, ready for departure, is called īsig. Perhaps “all aglitter”? “Icy” makes no sense. Despite all that, ice cannot be shown to be related to iron. (The etymological connection between ice and iron has been tentatively suggested in several sources, including The Century Dictionary, usually a reliable reference work.) Words that are pronounced in a similar way but have different meanings are called paronyms. Such were the Old Germanic names for “ice” and “iron.”

Ice and steal may gleam but the words for them are not related. (Image by One lucky guy via Flickr)

Ice and steal may gleam but the words for them are not related. (Image by One lucky guy via Flickr)Those who will take the trouble to look up ice in etymological dictionaries will read that this word occurred in all the Germanic languages except Gothic. From fourth-century Gothic we have part of the New Testament. Icebergs and frozen rivers cannot be expected to grace the Biblical landscape. Yet in the Old Testament, ice does occur more than forty times (especially often as part of the compound ice-storm). Most of them are concentrated in Exodus, but we also read in Job: “My brethren have dealt deceitfully as a brook, and as the stream of brooks they pass away, which are blackish by reason of the ice, and wherein the snow is hid…” VI: 15-16. (Snow and ice… Why blackish?) Also, in Job 38: 29: “…out of whose womb came the ice.” Nor are Psalms free from ice (for instance: “He casteth forth his ice like morsels”—147: 1; like morsels? All the passages are from the Revised Version), but only once do we come across ice in the New Testament (Revelations). So even if all four gospels had been extant in Gothic, we would still have not found the word in that text. (I’ll stay away from the ludicrous idea that Jesus walked on the ice.) Yet a Gothic rune has come down to us. It has the strange name iiz. No one knows the value of the last letter. Yet the rune certainly means “ice.” Thus, īs was indeed the Common Germanic word for “ice.”

When in an ancient language a long vowel occurs before s, there is a suspicion that once the word began with a short vowel followed by n or m (the nasal consonant was allegedly lost, and the vowel acquired length by compensation, as, for instance happened in English five, which once had in or im in the root: compere German fünf). Germanic īs may have at one time begun with in-, but this idea was refuted almost as soon as it was offered. Yet one can see references to it in some good modern dictionaries, even though presented hesitatingly. An often-cited cognate of ice is Russian inei “rime.” However, the origin of inei has not been discovered. In this blog, I keep repeating that one word of unknown etymology cannot be called upon to elucidate another equally or even more obscure word (obscurum per obscurius).

Ice has a few lookalikes in Celtic (in Gaelic and Irish; for instance, Middle Irish aig). Some words for “ice” that occur in the Iranian languages (isu-, aēxa, yex, and so forth; read x as kh) also have a similar shape: a long vowel and a guttural sound after it. The similarity between all of them and Germanic īs (or its putative Indo-European form eis) can hardly be called striking. Basque izos “frost” begins with iz– and appears to be a good match for Germanic īs, but why should the speakers of Germanic have borrowed a Basque name for “ice”? This etymology has been proposed within the framework of a hypothesis that looks upon numerous words of questionable origin as loans from Basque. By contrast, in Latin, we find only glaciēs “ice,” familiar from English glacier and German Gletscher. This is a typical Alpine word, like English avalanche and possibly German Lawine (the same meaning). Such words made it into our modern languages from Alpine dialects, and their origin can seldom, if ever, be recovered.

What grows with its head down? (Image by Kiwihug via Unsplash)

What grows with its head down? (Image by Kiwihug via Unsplash)Several fanciful etymologies of ice exist. They need not concern us here: unproductive guesswork. More important is the fact that Old Icelandic jaki “ice floe” (the root of jökull) is supposed to be related to the Celtic words mentioned above (for instance, Middle Irish aig “ice”). If so, jaki and ice emerge as closely related, almost as doublets. Is icicle a tautological compound “ice-ice”? (See the posts for 21 June 2006 and 26 July 2006, in which such words are discussed.) This conclusion does not sound fully convincing. Perhaps Germanic did have at least two words for “ice.”

As usual, when rambling becomes confusing, it may be worthwhile to look back and draw some conclusions, however tentative. In dealing with the etymology of ice, we have encountered several conjectures. Perhaps ice is not an Indo-European noun but a so-called migratory word (German Wanderwort) for “frost” or some variety of ice (solid ice, hollow ice, packed ice, crushed ice, iceberg, glacier, or whatever), later generalized. Or perhaps it was coined far away from the historical habitat of the Scandinavians and Germans and reached them along with many other words later used to describe their native landscape. Those who adopted īs seem to have some doubts about how to use it: the noun was masculine in Scandinavian but neuter in West Germanic! Or ice might be a word that had a transparent origin, but we have no way of guessing it.

Feature image by Aleksi Aaltonen via Flickr

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers