Oxford University Press's Blog, page 99

August 27, 2021

Six summer reads from Oxford World’s Classics

Summer is the perfect time to escape into a good book. This year, more than ever, we can appreciate the power of losing yourself in a great story. Here is a selection of six classic novels to see you through the rest of summer…

Daniel Deronda Discover George Eliot’s final novel, which centres on the figure of Gwendolen Harleth. Trapped in an increasingly destructive relationship, only her chance encounter with the idealistic and eponymous Deronda seems to offer the hope of a brighter future…

Discover George Eliot’s final novel, which centres on the figure of Gwendolen Harleth. Trapped in an increasingly destructive relationship, only her chance encounter with the idealistic and eponymous Deronda seems to offer the hope of a brighter future…

George Eliot’s powerful novel is set in a Britain whose ruling class is decadent and materialistic. The novel’s exploration of sexuality, guilt, and the will to power anticipates later developments in fiction, and its linking of the personal and the political in a context of social and economic crisis gives it especial relevance to the dominant issues of the twenty-first century.

Read Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

Emma Delight in the schemes of Emma Woodhouse, the lovely, lively, wilful, and fallible heroine of Jane Austen’s fourth published novel…

Delight in the schemes of Emma Woodhouse, the lovely, lively, wilful, and fallible heroine of Jane Austen’s fourth published novel…

Emma is written with matchless wit and irony, judged by many to be Austen’s finest work and considered the most representative novel by many modern readers. She evokes for her readers a cast of unforgettable characters and a detailed portrait of a small town undergoing historical transition. A perfect summer read!

Read Emma by Jane Austen

Gulliver’s Travels With our usual travel plans unconfirmed this summer, why not live vicariously through the travel adventures of Gulliver! Though not a laid-back beach trip we’d envisage for ourselves, this classic tale is brimming with colour and fantasy, with extraordinary experiences and encounters…

With our usual travel plans unconfirmed this summer, why not live vicariously through the travel adventures of Gulliver! Though not a laid-back beach trip we’d envisage for ourselves, this classic tale is brimming with colour and fantasy, with extraordinary experiences and encounters…

Though travel may be what sparks you to pick up this novel, it is the skilful blend of fantasy and realism which will keep you turning the pages. Swift plays tricks on the reader and delivers a satire of the human condition that is hilarious, frightening, and profound.

Read Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

Little Women Be inspired this summer by the lives of the characters in Little Women. This novel has remained enduringly popular since its publication in 1868, becoming the inspiration for a whole genre of family stories…

Be inspired this summer by the lives of the characters in Little Women. This novel has remained enduringly popular since its publication in 1868, becoming the inspiration for a whole genre of family stories…

Set in a small New England community, it tells the story of the March family: Marmee looks after her daughters in the absence of her husband, who is serving as an army chaplain in the Civil War, and Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy experience domestic trials and triumphs as they attempt to supplement the family’s small income.

Read Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Pride and Prejudice As one of the most famous love stories of all time, this classic novel has also proven itself as a treasured mainstay of the English literary canon. Lose yourself in the world of the Bennett sisters as they navigate society…

As one of the most famous love stories of all time, this classic novel has also proven itself as a treasured mainstay of the English literary canon. Lose yourself in the world of the Bennett sisters as they navigate society…

Whether it’s your first summer reading this novel, or you’re rediscovering a favourite, it is impossible not to feel uplifted by this tale. As a story that celebrates the happy meeting-of-true-minds more unflinchingly than any of Austen’s other novels, and one that has attracted the most fans over the centuries, Pride and Prejudice sets up an echo chamber of good feelings in which romantic love and the love of reading amplify each other.

Read Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Vanity Fair If your summer reading list is lacking an anti-heroine, you’d do well to add Vanity Fair to your to-be-read pile. Indulge in the wit and vitality of Becky Sharp and the fierce battle for social success…

If your summer reading list is lacking an anti-heroine, you’d do well to add Vanity Fair to your to-be-read pile. Indulge in the wit and vitality of Becky Sharp and the fierce battle for social success…

This classic novel is a must-read story, where the satire is at once biting and profound, sparing none in a clear-eyed exposure of a world on the make. Thackeray’s scepticism of human motives borders on cynicism, yet Vanity Fair is among the funniest novels of the Victorian age.

Read Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray

This list is just six of the hundreds of 18th and 19th century works available on Oxford World’s Classics, so if you’ve already checked off all six of our recommendations from your reading list then browse the online collection for more summer-reading inspiration!

Featured image by Patrick Tomasso via Unsplash

August 26, 2021

Science denial: why it happens and 5 things you can do about it

Science denial became deadly in 2020. Many political leaders failed to support what scientists knew to be effective prevention measures. Over the course of the pandemic, people died from COVID-19 still believing it did not exist.

Science denial is not new, of course. But it is more important than ever to understand why some people deny, doubt or resist scientific explanations—and what can be done to overcome these barriers to accepting science.

In our book “Science Denial: Why It Happens and What to Do About It,” we offer ways for you to understand and combat the problem. As two research psychologists, we know that everyone is susceptible to forms of it. Most importantly, we know there are solutions.

Here’s our advice on how to confront five psychological challenges that can lead to science denial.

Challenge #1: social identityPeople are social beings and tend to align with those who hold similar beliefs and values. Social media amplify alliances. You’re likely to see more of what you already agree with and fewer alternative points of view. People live in information filter bubbles created by powerful algorithms. When those in your social circle share misinformation, you are more likely to believe it and share it. Misinformation multiplies and science denial grows.

Action #1: Each person has multiple social identities. One of us talked with a climate change denier and discovered he was also a grandparent. He opened up when thinking about his grandchildren’s future, and the conversation turned to economic concerns, the root of his denial. Or maybe someone is vaccine-hesitant because so are mothers in her child’s play group, but she is also a caring person, concerned about immunocompromised children.

We have found it effective to listen to others’ concerns and try to find common ground. Someone you connect with is more persuasive than those with whom you share less in common. When one identity is blocking acceptance of the science, leverage a second identity to make a connection.

Challenge #2: mental shortcutsEveryone’s busy, and it would be exhausting to be vigilant deep thinkers all the time. You see an article online with a clickbait headline such as “Eat Chocolate and Live Longer” and you share it, because you assume it is true, want it to be or think it is ridiculous.

Action #2: Instead of sharing that article on how GMOs are unhealthy, learn to slow down and monitor the quick, intuitive responses that psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls System 1 thinking. Instead turn on the rational, analytical mind of System 2 and ask yourself, how do I know this is true? Is it plausible? Why do I think it is true? Then do some fact-checking. Learn to not immediately accept information you already believe, which is called confirmation bias.

Challenge #3: beliefs on how and what you knowEveryone has ideas about what they think knowledge is, where it comes from and whom to trust. Some people think dualistically: There’s always a clear right and wrong. But scientists view tentativeness as a hallmark of their discipline. Some people may not understand that scientific claims will change as more evidence is gathered, so they may be distrustful of how public health policy shifted around COVID-19.

Journalists who present “both sides” of settled scientific agreements can unknowingly persuade readers that the science is more uncertain than it actually is, turning balance into bias. Only 57% of Americans surveyed accept that climate change is caused by human activity, compared with 97% of climate scientists, and only 55% think that scientists are certain that climate change is happening.

Action #3: Recognize that other people (or possibly even you) may be operating with misguided beliefs about science. You can help them adopt what philosopher of science Lee McIntyre calls a scientific attitude, an openness to seeking new evidence and a willingness to change one’s mind.

Recognize that very few individuals rely on a single authority for knowledge and expertise. Vaccine hesitancy, for example, has been successfully countered by doctors who persuasively contradict erroneous beliefs, as well as by friends who explain why they changed their own minds. Clergy can step forward, for example, and some have offered places of worship as vaccination hubs.

Challenge #4: motivated reasoningYou might not think that how you interpret a simple graph could depend on your political views. But when people were asked to look at the same charts depicting either housing costs or the rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over time, interpretations differed by political affiliation. Conservatives were more likely than progressives to misinterpret the graph when it depicted a rise in CO2 than when it displayed housing costs. When people reason not just by examining facts, but with an unconscious bias to come to a preferred conclusion, their reasoning will be flawed.

Action #4: Maybe you think that eating food from genetically modified organisms is harmful to your health, but have you really examined the evidence? Look at articles with both pro and con information, evaluate the source of that information, and be open to the evidence leaning one way or the other. If you give yourself the time to think and reason, you can short-circuit your own motivated reasoning and open your mind to new information.

Challenge #5: emotions and attitudesWhen Pluto got demoted to a dwarf planet, many children and some adults responded with anger and opposition. Emotions and attitudes are linked. Reactions to hearing that humans influence the climate can range from anger (if you do not believe it) to frustration (if you are concerned you may need to change your lifestyle) to anxiety and hopelessness (if you accept it is happening but think it’s too late to fix things). How you feel about climate mitigation or GMO labeling aligns with whether you are for or against these policies.

Action #5: Recognize the role of emotions in decision-making about science. If you react strongly to a story about stem cells used to develop Parkinson’s treatments, ask yourself if you are overly hopeful because you have a relative in early stages of the disease. Or are you rejecting a possibly lifesaving treatment because of your emotions?

Feelings shouldn’t (and can’t) be put in a box separate from how you think about science. Rather, it’s important to understand and recognize that emotions are fully integrated ways of thinking and learning about science. Ask yourself if your attitude toward a science topic is based on your emotions and, if so, give yourself some time to think and reason as well as feel about the issue.

Everyone can be susceptible to these five psychological challenges that can lead to science denial, doubt and resistance. Being aware of these challenges is the first step toward taking action to meet them.

Read a free introductory chapter “What Is the Problem and Why Does It Matter?” from Science Denial, freely available until 31 October 2021.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Feature image by fauxels from Pexels

August 25, 2021

The henchman’s dilemma

The origin of some words is hard to find, and researchers dispute one another’s conclusions with the vehemence perhaps worthy of a better cause. Any good etymological dictionary lists a series of conjectures and often concludes: “Origin unknown,” that is, conjectures (clever or unreasonable) exist, but the solution is wanting. Such is the recognized format outside so-called dogmatic dictionaries, which lay down conventional wisdom as they interpret it. Yet I am aware of only two English words whose origin has provoked enough passion and bad blood to inspire a thriller. The first such word is cockney. At the beginning of my career as blogger, fourteen years ago, I posted a short essay on cockney (11 July 2007). It gives no idea of the spirit of the controversy, and I have a great mind to rewrite that post and tell the whole story anew. In my book An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction, I did discuss everything in detail, but that entry is too long for a busy reader to enjoy, and the book is, alas, not on everybody’s desk. The old exchange on cockney reads like a chapter in the history of a civil war.

The second word in this small group is henchman. The discussion played itself out in the pages of the periodical Notes and Queries and lasted with no letup for nine years (!), from 1887 to 1896. If republished, it might fill a small thriller. (Book proposal: “The Greatest Battles in the First Etymological World War: Cockney and Henchman.”) Most unfortunately, the 1887-1896 controversy has left only few vague, unrecognizable traces in our dictionaries. Those who today volunteer to write about henchman on the Internet are, as far as I can judge, unaware of it. James A. H. Murray, the main editor of the OED, contributed a short explanation about the word’s sources to that polemic but offered his opinion only in the dictionary entry and there stayed away from bibliographical references.

Boss and his henchmen. (Image © Astor Pictures – 1946 re-release, CC0 Public Domain)

Boss and his henchmen. (Image © Astor Pictures – 1946 re-release, CC0 Public Domain)The main opponents in that battle were Walter W. Skeat, a great scholar of Middle English and the author of our still most authoritative, even if in parts outdated, etymological dictionary of English, and Frank Chance, a medical doctor and extremely knowledgeable philologist, who, unfortunately, published almost only in Notes and Queries and is therefore all but forgotten. The readers of this blog know that I have a soft spot for him and advertise his achievements at every opportunity. Though it is not in my power to rescue him from oblivion, I hope that the professional teams at the OED and perhaps also at Merriam-Webster will, as the result of my efforts, turn to Chance’s heritage more often than is usually done (my Bibliography of English Etymology contains a long list of his notes). Frank Chance died in 1897 and deserves at least as much fame as his namesake, the celebrated baseball player. Several other scholars and amateurs participated in the controversy, but only Chance and Skeat are its heroes: Chance attacked, and Skeat defended himself without the passion so typical of his belligerent polemic spirit. His mind was apparently set, and counterarguments did not impress him.

Walter Scoot revived many obsolete words in Modern English. (Image: Snapshots of the Past, )

Walter Scoot revived many obsolete words in Modern English. (Image: Snapshots of the Past, )The word henchman surfaced in English texts in 1360 (thus, in Middle English) and has been recorded in the forms hengest (note this form!), henxst-, and hensman, among others. It first seems to have meant “a squire or page,” though the rank of that person and his original duties are not quite clear. Perhaps simply “attendant” was meant. In the seventeenth century, henchman was defined as “domestic, or one of a family” by Thomas Blount, the author of the book Glossographia, first published in 1656; he called the word German, without giving reasons for this attribution. Henchman has not fallen into oblivion, only because Walter Scott revived it. The sense “mercenary adherent, venal follower” developed in the United States and is the only one still known to the speakers of American (and probably British) English: “so-and-so and his henchmen”. The family names Henchman, Hensman, Hincksman, and the like bear witness to the word’s vitality (I have borrowed the last piece of information from The Century Dictionary).

The oldest etymologies connected henchman with Latin anculus “servant” (compare English ancillary) or with English haunch (henchman “a person at the haunch of his superior”; this was Walter Scott’s opinion). Compare the following quotation from The Quarterly Review, 1846-47, p. 344, note: “There is a curious etymological indication of an intermediate state of servitude in our olden time, when personal attendants, in public, were called henchmen, men at the haunch or side; in the Scotch dialect lackeys are still called flunkies…, which is from French flanchier.” The comparison between henchman and flunkey is commonplace; henchman designated “a personal attendant or chief gillie of a Highland chief” as early as the eighteenth century (gillie “attendant on a Highland chief”). Whether flunkey is indeed flanker need not concern us here. Neither etymology (from anculus or from haunch) has anything to recommend it, though even in the 1880s some people defend them.

Two points must be made here.

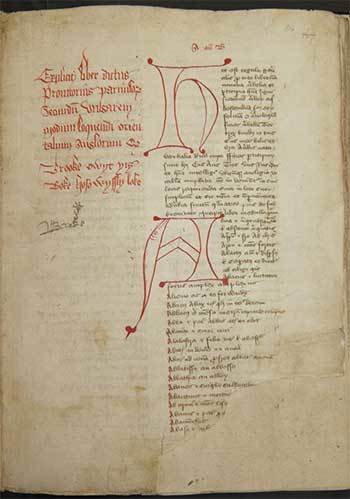

A page from an edition of Promptorium Parvulorum. (Image via British Library, Add MS 37789)

A page from an edition of Promptorium Parvulorum. (Image via British Library, Add MS 37789)First. The word hengst “stallion” did exist in Old English. Among other things, the legendary leaders of the invasion of England by Germanic tribes in the fifth century were called Hengest and Horsa (if the legend can be trusted). Horsa looks familiar: it is hors “horse” with an added masculine ending of the weak declension. Hengist is also recognizable, but only from Scandinavian hengst, where both words have survived (the Scandinavian cognate of horse is hros, that is, ross: the interplay of the or ~ ro type is called metathesis). In English, the word hengst died out early: no records of it postdate the beginning of the thirteenth century. Henchman, it will be remembered, surfaced only in 1360. If henchman goes back to hengstman, the question arises how hengst became part of a compound a century and a half after its disappearance from the language. Even in 1200 it must have been an archaism. Moreover, nothing in the early or later history of henchman indicates that henchmen were riders par excellence.

Second. In 1440, a most remarkable English-Latin dictionary titled Promptorium Parvulorum…., that is, “Storehouse for Children,” was written in Norfolk. The text is of course available in modern editions. The word hengstman appears there and is glossed gerolocista or gerelocista. Unfortunately, the meaning of this rare Medieval Latin word is not quite clear, but it, most certainly, does not refer to horses, mares, or stallions. In the 1887-1896 exchange, a good deal of space was devoted to gerolocista. The zeal expended on this word was not wasted, because the distance between 1360 and 1440 is not too great, and the meaning of the word may not have changed too radically over eighty years.

I decided not to hurry and divided this essay into two parts. Next week, I’ll return to both mysterious words—henchman and gerolocista—and offer my cautious conclusion about the origin of the first one, the only item, as most will agree, that interests us here.

Feature image: Piper Ribbon via Max Pixel (CC0 Public Domain)

August 24, 2021

What does the history of Victory Day tell us about Russia’s national identity?

Every year on 9 May, Russia observes Victory Day as its most important national holiday. It celebrates the end of the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945) by staging events that dwarf those of any other country. In 2021, the performance in Moscow included 12,000 Russian troops marching through Red Square, followed by tanks and missile launchers, and it concluded with an aerial show of 76 jets and helicopters—one for every year since the victory over Nazi Germany.

This holiday is designed above all to remind the world of the enormous contributions Russia made in the Great Patriotic War. A few surviving veterans attend the event as a reminder that the Red Army inflicted nearly 90% of all Germany’s combat losses, and civilians across the country solemnly commemorate the 27 million Soviet citizens who died in the conflagration (compared, for example, to about 420,000 Americans deaths).

But Victory Day is not just about the past. It is also about national identity in the present, and as this identity project has changed, so has the memory of the war. In years immediately following 1945, 9 May received scant attention. The country was busy pursuing its global ideological mission of Marxism-Leninism and also in repairing the massive damage it had sustained. But by the end of the 1980s, the declining legitimacy of Communist ideology led authorities to search for other ways to mobilize the population and, in this context, they turned increasingly to Russian nationalism. Among other things, this required a new usable past, giving new meaning to the aphorism: “nothing is so unpredictable as Russia’s past.”

These transitions were much in evidence in how the Communist Party was depicted in the Great Patriotic War. During the Soviet era, Party members were presented as dedicated, courageous, and selfless fighters at the vanguard of the effort to liberate the USSR and the rest of the world from German fascism. A 1964 Soviet history textbook, for example, told of how troops going on the most dangerous missions said their greatest wish was to be considered a Communist. Textbooks of that era also encouraged students to visit history museums where they could see Communist Party members’ cards pierced by bullet holes and soaked in blood. In this telling, the Party was presented as the leader of the masses as they struggled to rout class enemies in the form of fascist murderers.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, this picture underwent a drastic revision. The Party’s legitimacy declined and citizens began expressing doubts and criticisms that would never have been heard in public discourse a few years earlier. Comments that might have been part of private debate “in the kitchen” in Soviet parlance surfaced in the media, memoirs, and even official history textbooks. In the exhilarating discussions of the time, well-established Soviet truths about the Great Patriotic War were replaced by claims that would have landed authors in prison in previous decades.

For example, a 1995 Russian history textbook blamed the Party-led regime for the fact that the Germans reached the Volga at Stalingrad, something that had never before happened in Russian history. In this new version, it was only when the Party was pushed aside to allow true military professionals to take over that Soviet fortunes improved in the Great Patriotic War, making the Party an impediment rather than a hero in the war effort. The most important new heroes to appear in this post-Soviet narrative were the Russian masses, the Russian nation.

In short, the transition from the Soviet to post-Soviet era in Russia witnessed a drastic revision in official memory about the most important existential threat of the twentieth century. This might seem to make national memory a fickle servant of political needs, but to leave it at that misses a larger picture. This picture is one a deeper narrative in which the leading actors may change, but the basic plot remains the same. What appears on the surface to be a radical rewrite of national memory turns out to involve the same underlying storyline, and the transition from Soviet to post-Soviet accounts turns out to be a case of telling the same basic story with different characters.

The stable, underlying story at work in such cases is a “narrative template.” This unconscious narrative code gives rise to mental habits that shape the national memory and national identity more generally. These habits form a coherent perspective that is resistant to change, but one that is also sufficiently protean to accommodate varying accounts of events with their specific dates, places, events, and actors. In the Russian case, the “Expulsion-of-Alien-Enemies” narrative template provides the formula for both the Soviet and post-Soviet account of the Great Patriotic War, and also for other events from previous centuries. It helps explain why the expression “Great Patriotic War” caught on so quickly for Russians in 1941, where the conflict was viewed as another instantiation of the same basic plot for the “Patriotic War” waged against Napoleon more than a century earlier.

This is a narrative template that shapes Russian understanding of many events in the present as well as the past. For example, it lies behind Vladimir Putin’s frequent beliefs about NATO as a threat—beliefs shared by many Russians but rejected as paranoid by Westerners. All this makes Victory Day an annual event, which, to be sure commemorates the massive losses of the Great Patriotic War, but is also an occasion on which Russians renew their commitment to a national narrative that defines who they are in the twenty-first century.

August 21, 2021

Closing the Brain Health Gap: addressing women’s inequalities

There is a clear sex and gender gap in outcomes for brain health disorders across the lifespan, with strikingly negative outcomes for women. This understanding calls for a more systematic way of approaching this issue of inequality. The “Brain Health Gap” highlights and frames inequalities in all areas across the translational spectrum from bench-to-bedside and from boardroom-to-policy and economics. Closing the Brain Health Gap will help economies create recovery and prepare our systems for future global shocks. It is a testament to the imperative of the “Brain Health Gap” that this conversation is moving beyond the inner circles of women’s convenings to more global platforms like the Organisation of Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and the Virtual Lausanne Dialogues in May 2021, convened ahead of the World Health Assembly by the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease (CEOi), the World Economic Forum (WEF), and the Davos Alzheimer’s Collaborative (DAC).

Alongside economic projections on the global prevalence and expanding burden of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, the Virtual Lausanne Dialogues saw the release of a new US-centric economic study. The WHAM Report (Women’s Health Access Matters) shows that high network countries cannot afford inaction. Commissioned by a group of leading US business women and conducted by the non-profit RAND Corporation, the report was designed to study the impact of accelerating sex- and gender-based health research on women, their families, and the economy across diseases, like Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, that impact women differently and differentially.

The WHAM Report found that women are 66% of the nearly 7 million people in the US with Alzheimer’s, and yet just 12% of 2019 NIH Alzheimer’s fund went to projects focused on women. Even more, the report showed the following: a) doubling the funds for women’s Alzheimer’s research pays for itself three times over; b) this 224% return on investment adds 15% more to our economy than general Alzheimer’s research; and c) adding $300 million for research on women generates $930 million in economic gains, adds back 4,000 years of life, eliminates 6,500 Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, and saved 3,500 years of nursing home care and costs.

Disparities in prevalence, detection, and treatment are especially widespread and problematic in women’s brain health. The current brain health crisis—where brain health disorders span mental disorders like depression and anxiety to neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s disease—has disproportionately affected women. From a clinical and neuroscience perspective, there is a clear sex and gender gap in outcomes for brain health disorders across the lifespan, with strikingly negative outcomes for women. For example, two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients worldwide are women. Further, US women over 60 are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease as breast cancer. In Australia, England, and Wales, dementia has become the leading cause of death for women, surpassing heart disease. Further, women have a higher lifetime risk of stroke than men and are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders and migraines. These are all specific risks factors to develop dementia.

“Women’s symptoms are often overlooked, dismissed, or misdiagnosed due to poor understanding of female-specific symptoms.”

In addition, women’s symptoms are often overlooked, dismissed, or misdiagnosed due to poor understanding of female-specific symptoms. For instance, this is the case for mild cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, which is often overlooked due to the capacity of women to compensate due to a higher verbal memory reserve. This results in vast health inequities, which are aggravated by the higher level of poverty among women resulting in lower access to healthcare services.

Despite many mental and brain health conditions inexplicably affecting women, and the compelling economic case for funding women-focused studies as shown in the WHAM Report, there has been a lack of research to understand why. Across the age continuum women experience the changes in sex hormones (i.e., estrogen, progesterone, and androgens) induced by pregnancy and aging. Thus, it is probably not just the changes at menopause that impact modifications in behavior, cognition, mood, and sleep in women. More research is needed to understand the link between hormone changes in aging and the role of endogenous hormones in neural and cognitive processing.

Indeed, there is a large sex and gender data gap in medical research and textbooks. A large factor in the current sex and gender data gap is the exclusion or underrepresentation of females from cell, animal, and human clinical studies. From 1977 to 1993, the US Food and Drug Administration banned women of childbearing potential from participating in clinical trials. To this day, women are often excluded from clinical studies due to unsubstantiated beliefs that fluctuations in female hormones make women more difficult and expensive to study. When women are included, the data are often not analyzed for sex and gender differences. Thanks to the pioneering work of organizations such as the Women’s Brain Project, WHAM, WomenAgainstAlzheimer’s, the Global Alliance on Women’s Brain Health, and other scientific institutions around the world aimed at understanding sex and gender differences impacting brain and mental diseases, research has revealed significant sex and gender differences—such as with Alzheimer’s disease. It is now the time to implement these learnings into clinical development setting.

“Medical school curriculum continues to uphold that male and female bodies are generally the same besides for sex organs—a belief known as ‘bikini medicine’.”

For example, a 2005 Dutch study found that sex- and gender-related issues were “scarce or absent” across medical textbooks related to coronary heart disease, depression, alcohol abuse, and pharmacology, even though significant sex- and gender-related differences in prevalence and disease manifestation have been found across these conditions. Further, a 2016 study analyzed the online database for med-school courses in the United States (known as CurrMIT) and then had first- and second-year medical students audit the medical school curriculum for sex-and gender-related curriculum. The study demonstrated that schools integrating sex- and gender-related differences into curriculum was “minimal” and “haphazard and poorly defined.” Most of the content that did exist was “focused on the physiological/anatomical sex differences or gender differences in disease prevalence, with minimal coverage of sex- or gender-based differences in diagnosis, prognosis, treatment and outcomes.” In other words, medical school curriculum continues to uphold that male and female bodies are generally the same besides for sex organs—a belief known as “bikini medicine”—causing particularly large gaps in approaching treatment of disease and use of drugs. Interestingly, there was a significant positive association between the schools that offered the most comprehensive sex- and gender- related topics and having a women’s health program or female dean.

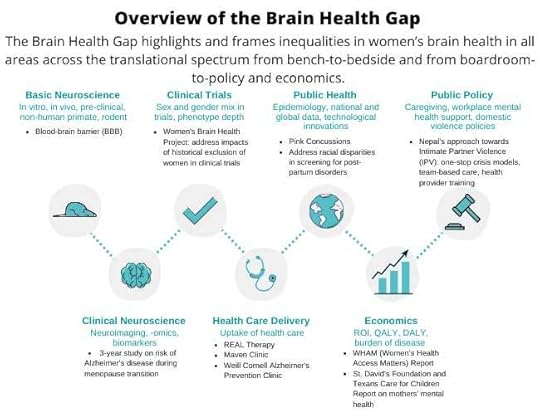

Beyond clinical implications of the lack of research on sex and gender differences in brain health, there are profound societal and economic ramifications. In addition to the WHAM Report, another recent report found that in the state of Texas alone, over $2.2 billion is lost by not treating mothers’ mental health issues from pregnancy until their child is five years old. This number does not account for how untreated mental health issues will affect the children and next generation. Indeed, a “Brain Health Gap” exists in all areas across the translational spectrum from bench-to-bedside to boardroom-to-policy. These inequities exist from science to clinical trials, to investment, to healthcare delivery, to economics. Figure 1 provides a graphical overview.

Figure 1

Figure 1“Women—especially those who are racial-ethnic minorities and part of other underserved and marginalized groups—often bear the brunt of health inequities.”

COVID-19 has amplified and perpetuated the existing Brain Health Gap, exposing deeply entrenched societal inequities. The pandemic has magnified social and structural determinants of health and centuries of health inequity resulting from racism, colonization and imperialism, casteism, neighborhood segregation, income inequality, sexism and patriarchy, homophobia and transphobia, and anti-immigrant and xenophobia. Women—especially those who are racial-ethnic minorities and part of other underserved and marginalized groups—often bear the brunt of these health inequities. Thus, it is imperative that the conversation about women’s equality is not limited to cisgender, white females.

Despite the challenges of COVID-19, evidence indicates that women are more proactive than men in taking advantage of opportunities to improve, rebound, and strengthen their brain health and resilience and translate this charge to their families, communities, and the workplace. In a recent study, women across the life span enrolled in the BrainHealth Project at three times the rate of men. The results showed comparable gains between men and women in three factors contributing to global BrainHealth:

clarity (innovation, reasoning, optimism, compassion)fortitude (emotional balance)resilience (social support, purpose).These gains were achieved at some of the worst times in our lives with a majority experiencing heightened depression, anxiety, social isolation, and brain fog as many had been furloughed, had to leave their jobs to homeschool their children, and were suffering from an unpredictable future. This suggests that, while women carry the weight during times of crises, they also are a powerful force to take up the mantle to be proactive about building brain health for themselves, their families, and their communities. Giving major attention to the pivotal role of women in boosting economic and societal resilience may help shore up the weakening foundation of our families, communities, and workforce.

“Closing the brain health gap can be remedied only at the social, political, policy, and diplomatic level.”

Closing the brain health gap can be remedied only at the social, political, policy, and diplomatic level. Taking sex and gender into account—including biological factors and social influences—is critical for equality in brain health and precision medicine. The OECD’s Neuroscience-inspired Policy Initiative seeks to tackle the Brain Health Gap. We aim to reconceptualize and revitalize the economy and how it works in new ways, laying the groundwork to identify relevant metrics while building a transdisciplinary network of stakeholders. The effort draws on experts from medicine, neuroscience, gender analysis, economic policy, philanthropy, and business. The Initiative will rapidly refine and advance women’s brain health via a series of research projects, economic modelling, seminars, and clear policy analyses and recommendations. In doing so, we hope to address the Brain Health Gap, leading to greater health justice for all people and a new era of innovation and progress.

August 20, 2021

The expanding horizons of national security and the China-US strategic competition—where are we heading?

From Wall Street to Beijing Finance Street and beyond, one of the most important issues in international business and law is the changing conceptualization of national security. Corporations, businesses and investors are all affected by governmental decisions with respect to defending national security in the contexts of international investment, trade, and finance. The recent US ban on solar panels from Xinjiang and China’s restriction of Tesla vehicles exemplify the China-US hegemonic rivalry’s transformative impact on the conceptualization of national security.

Solar panels, electric vehicles, and social media do not comport with traditional notions of defending national security. However, although once ensconced in the context of military defense and territorial integrity, two primary and often inter-related factors are driving a new conceptualization of national security. One factor is the sweeping and revolutionary new technologies such as AI, 5G, blockchain-based central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and robotics. Such technologies may offer a pathway to degrade an adversary without resort to a military option. For example, non-US dollar (USD) CBDCs could serve as a pathway for bypassing the US-centric financial system depriving the US from imposition of USD sanctions, which the former US Treasury Secretary admitted was a replacement for US military intervention. Fostering the ability for a payments system which does not touch upon the US financial system (thus depriving the US of the power to track or stop the transaction) is a form of attack on the US although no US territory is invaded or threatened. The potential of a digital Yuan and China’s global digital leadership undoubtedly is considered as a threat by the US, and the threat encompasses any related technology to a digital Chinese currency.

Another proximate cause driving the re-conceptualization is the comprehensive rivalry between China and the US, which is rapidly expanding notions of security beyond emerging technology and into the economic and ideological realms. By doing so, political-economic ideology, social media, as well as capital markets are subject to enhanced scrutiny and regulation. China’s unique and successful state-centric economic governance—the partnering of private actor businesses with state-direction and often governmental ownership—is increasingly viewed by US authorities as possessing unfair advantages whereby US businesses cannot compete fairly. In response, China argues that measures against China are cloaked in the language of security but are in reality attempts to contain China’s rise and/or constitute economic jealousy and attempts to constrain her ascendancy.

To be sure, several important factors demonstrate that a more liberal conceptualization of national security is worthy of consideration. Military attacks are no longer the sole means of degrading or conquering another state; territorial integrity is not the only marker of sovereignty that is subject to being attacked. To a large degree, economic battle is a replacement for military conflict. Moreover, emergent technology such as AI does have significant military application besides civilian use. Furthermore, security threats may in fact be completely virtual such as computer viruses that devastate infrastructure leading to economic breakdown and social instability; cause missiles to self-detonate; or manipulate elections to elect a favorable candidate. Thus, degrading an enemy can be accomplished by ideological, economic, and technological means and territorial integrity or armed conflict is not necessarily implicated or needed to accomplish the goal of proximately causing substantial harm to an enemy state.

“Where does legitimate security end and improper protectionism commence?”

From a legal perspective, the ever-expanding conceptualization of security is a slippery slope and risks invoking the security exception in investment and trade agreements as a cover for protectionism. There are no easy answers nor is there a bright-line test. Where can legitimate lines be drawn; does legitimate national security encompass any and all social media and payments platforms? Data is crucial to AI, but does that translate into all devices and virtually all apps being data transfer points that constitute security threats? Where does legitimate security end and improper protectionism commence? Is there a difference between imposing national security measures against allies versus adversaries or is doing so sometimes legitimate? Moreover, is defending technological dominance or national champions in emerging technologies a legitimate exercise in defending national security? Is wielding technological superiority the equivalent of defending national security?

And as the slippery slope exists with respect to technology, the slope appears in the economic realm as well; both economic powers are at risk of expanding the security exception to such a degree that the exception can overtake the rule. Indeed, the new US security conceptualization does not stop at the technological or ideological but encompasses the economic as well. The US has been in the process of, or is discussing, numerous measures: de-listing of Chinese ADRs traded on US capital markets; advising US academic institutions to avoid investing in Chinese shares; considering eliminating the exemption for foreign issuers on audit inspections in a move widely acknowledged as targeting Chinese shares; and prohibiting US government pension funds from investing in Chinese shares. While economic superiority has not been considered as constituting an essential security interest, the line between defending property and defending economic dominance is not demarcated. Indeed, the broadening of the exception to include relative economic performance or dominance would unquestionably risk creating an exception that dwarfs the rule.

China is also vigorously expanding notions of security including social and economic stability as well as including extraterritorial application of new laws such as the Data Security Law and the Hong Kong National security Law. In early 2021, China enacted a Blocking Statute which might serve to counter-act foreign measures believed to threaten Chinese national interests. The language in China’s Export Law related to banning exports to nations or regions based on security threats to China may be a far-sighted assessment of the potential forming of coalitions based on mutual security interests.

The current trend of broadening the horizons of national security does not comport with international cooperation and globalization but supports decoupling and enhanced de-globalization and realignment of supply chains . There are indications that the main economic powers are at-risk of de-coupling as the US endeavors to maintain its edge and China is also preparing. Moreover, the injection of human rights in the rivalry may also be a harbinger of increasing regionalism or a split into coalitions as allied nations may begin forming coalitions based upon mutual economic self-interest. The formation of US and Chinese allied trade and investment coalitions may lead to increasing economic nationalism, regionalism, protectionism, and retaliation and ultimately to a fracturing of the existing trade and investment architecture.

Conceptualizing security as a fusion of economic, ideological, and technological supremacy has immense implications on international economic governance and law. Going forward, sovereigns may need to select which hegemonic contestant to form an alliance with. Doing so may take time but would likely cause a dramatic re-alignment of international trade into blocks of allies and/or regions. Moreover, future dispute resolution arbitrations will come under pressure to test the contours of the exception. Future rulings on the security exception will need to carefully balance the legitimate security interests of nations while guarding against an unfettered expansion of the conceptualization of security. While there are no absolute answers, one aspect is certain: the conceptualization of national security will become increasingly vital to global trade, investment, and economic governance.

Featured image by Markus Spiske. CC0 public domain.

August 18, 2021

The proverbial ninepence

The popularity of ninepence in proverbial sayings is amazing. To be sure, nine, along with three and seven, are great favorites of European folklore. No one knows for sure why just those numerals achieved such prominence. The reference to the fact that all of them are primes does not go far. Twelve has reached us from Mesopotamia, and we still have twelve hours in a day, twelve months in a year, and (in the United States) buy a dozen eggs. A nonstop orator “speaks nineteen to the dozen” (at least so in British English). I would not be in a hurry to trust the idiom’s etymology offered on the Internet, because every proverbial phrase with nine has a formulaic base and may have no foundation in historical fact (compare my discussion of nine tailors make a man: April 6, 2016): the “evidence” is usually invented in retrospect, to justify an obscure saying and therefore looks deceptively convincing. Remember also seven by nine politician (see the post for August 7, 2019), to look nine ways for Sunday, dressed up to the nines (in which nines is, most probably, a later substitution for eyes with the definite article in the plural dative before it!), nine days wonder, Cloud Nine, possession is nine points of the law (the latter phrase once served as the subject of a fine article by James A. H. Murray), and quite a few others. In 2017, I devoted a series of posts to nine of diamonds and the curse of Scotland. Ninepins are perhaps also worthy of mention.

However, ninepence is not only the mainstay of popular phrases: such a coin existed and became a common favorite. People went out of their way to find alliterative epithets that could go with it. Ninepence was called nice and nimble (though also plain, fine, grand, and right). Many reference books quote the 1840 Numismatics Chronicle (I retain the original spelling): “The nine-pence was formerly much favoured by faithful lovers in humble life as a token of their mutual affection. It was for this purpose broken into two pieces, and each party preserved with care one portion until, on their meeting again, they hastened to renew their vows.” A shilling, as is known, consisted of twelve pence, so that a stupid person acquired the reputation of being no more than ninepence in the shilling (that is, lacking three pence and therefore not all there), but the same phrase was applied to the greedy and avaricious people who always wanted to have a greater value for their shilling.

Just for your edification: a nimble ninepence is better that a slow shilling! The reference is to the fact that people are reluctant to spend large sums but spend small amounts easily. However, in the world of idioms, there is always a saying that contradicts another saying, because human wisdom is relative and limited. If you watch your pennies, your dollars will take care of themselves. Right? Yet some people are penny-wise but pound foolish. In any case, you may spend a nimble ninepence or break it into two halves, or let it roll—the result is unpredictable. In any case, give the old woman her ninepence, whatever that obscure recommendation means (I have once written about it).

A groat and a five-kopek coin. Four pence by Jerry Woody, CC-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Five-kopek coin via Picryl.

A groat and a five-kopek coin. Four pence by Jerry Woody, CC-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Five-kopek coin via Picryl.In my database, I have a few less “famous” sayings. A hundred and fifty years ago, in Ireland, they said about a stingy person: “As narrow in the nose as a pig at ninepence.” The alliteration is obvious, but the image is not: what is a pig at ninepence and why narrow? A pig’s snout perhaps resembles a coin, though hardly a narrow one (in Russian, it is called piatachók; the same word for a very narrow piece of land and a five-kopek coin: a kindred idea?). Also, long ago, the phrase Ninepence, Nanny! Two groats and a penny occurred in Derbyshire. This rigmarole was an evasive answer to somebody’s question: “What did so-and-so say?” (Such humorous phrases are many; only their humor is sometimes hard to grasp.) Now, a groat, which was worth four old pence, went out of use in the second half of the seventeenth century (the word is akin to grit). Its name probably did not die out because of the phrase “I don’t care a groat.” Nanny alliterates with ninepence and may be said to rhyme with penny, but the whole makes little sense. In any case, since two groats and a penny constituted a small sum of money, the mocking remark might perhaps intimate that the question did not deserve an answer.

Is it narrow? Pig via Pixaby, public domain.

Is it narrow? Pig via Pixaby, public domain.Bring a noble to ninepence and ninepence to nothing (alliteration galore) and his noble has come down to ninepence are slightly more familiar. The latter is said about a person who has been brought down in the world, and from a state which in his own estimation had been rather an important one, while the first refers to those who live beyond their means.

I think something should also be said about a shilling. Perhaps the best-known phrase with this word is to cut one off with a shilling. In the past, it was discussed by many people. My references go all the way from 1854 to 1928. The meaning of the act (rather than of the idiom) is, as far as I can judge, noncontroversial: “To be disinherited from a will by being bequeathed a single shilling rather than nothing at all.” The phrase is not particularly old: the OED has no citations predating 1762, but I seem to have a 1754 reference. It has been suggested that for a testator to prove that he was mentally alert, he had to leave the child at least something. An old law allowed fathers and husbands to disinherit their children and wives by leaving them only a sixpence (thus, even less than a shilling).

A haunting word, a terrible thing. The Coat of Arms of Sir Winston Churchill (1620-1688). CC-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A haunting word, a terrible thing. The Coat of Arms of Sir Winston Churchill (1620-1688). CC-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Not versed in legal history, I wonder: could an Anglo-Saxon nobleman, in the twelfth or thirteenth century, disinherit his son? Since my childhood, I remember that Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe, the hero of Walter Scott’s novel (years ago, it was part of high school curricula but is no longer such, because our young people’s minuscule vocabulary does not allow them to read nineteenth-century books in their native language: the common verdict is: “Boring”). Anyway, Ivanhoe’s father disinherited Ivanhoe for his allegiance to King Richard Lionheart and for falling in love with Lady Rowena, Cedric’s ward, destined for a most unprepossessing native nobleman. Ivanhoe appears at a tournament incognito, with the Spanish word Desdichado on his shield. This mysterious word meaning “disinherited” haunted me for years, but it reflected the protagonist’s status well. Is there documentary evidence for Walter Scott’s description of Ivanhoe’s situation? Probably fathers could disinherit their children in all centuries.

I wonder whether many of our readers were troubled by such mysterious words in their “green years.” Along with Desdichado, the magic word mutabor from Wilhelm Hauff’s Caliph Stork filled me with awe. To return to their human form, the Caliph and his retainer had to say mutabor, but they had been enjoined not to laugh while in their bird form for fear of forgetting the word. In fairy tales, interdictions exist only to be violated. Of course, the two men laughed. Years later, when I took my first course in Latin, I discovered that mutabor means “I’ll change” (mutate, as it were) and was disappointed: the magic of the incomprehensible charm was gone. Fortunately, nowadays, children don’t study Latin, just as they don’t study grammar, or read Walter Scott, for none of the three is “fun.” The opposite of in for a penny, in for a pound, I believe.

Feature image: Cigogne en envole by Groteddy via Wikimedia Commons

August 16, 2021

SHAPE and societal recovery from crises

The SHAPE (Social Sciences, Humanities, and the Arts for People and the Economy) initiative advocates for the value of the social sciences, humanities, and arts subject areas in helping us to understand the world in which we live and find solutions to global issues. As societies around the world respond to the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, research from SHAPE disciplines has the potential to illuminate how societies process and recover from various social crises.

In recognition of the essential role these disciplines play for societal recovery, we have curated a hub of SHAPE research which looks back on how we have rebuilt from social crises in the past, how societies process living through extraordinary times, and considers the next steps societies can take on the road to recovery.

Lessons from the pastThroughout history, individuals and societies have encountered periods of crisis caused by factors including war, natural disasters, and health pandemics. Responses to these crises can provide a vital insight into how we respond to future global threats.

In a review of how societies respond to peril, Robert Wuthnow suggests that, “nothing, it appears, evokes discussion of moral responsibility quite as clearly as the prospect of impending doom.” Wuthnow examines how societies have responded to four major threats: nuclear holocaust, weapons of mass destruction, concern about a global pandemic, and the threat of global climate change, and finds that, “the picture of humanity that emerges in this literature is one of can-do problem solvers. Doing something, almost anything, affirms our humanity.”

Looking further back, the US Civil War also had a profound impact on many people and touched women’s lives in contradictory ways. Hannah Rosen’s chapter “Women, the Civil War, and Reconstruction” examines the wartime and postwar experiences primarily of black and white but also Native American women and provides insights into how we can reconstruct a fairer society following conflicts. Meanwhile, in Total War: An Emotional History, Claire Langhamer examines the role emotions played in the immediate aftermath of WWII, approaching our relationship to feeling through the lens of social, as well as cultural, history.

How we choose to commemorate the past is also a key question, explored by Joshua Gamson in an article published in Social Problems about the US National AIDS Memorial Grove.

Looking back on the economic implications of social crises, Mark Bailey discusses how the plague acted as a catalyst for the vast transformation of trading routes in North Sea economies. This economic shift has been reflected in the COVID-19 pandemic and, in response, authors from the Journal of Consumer Research have created a conceptual framework for understanding how consumers and markets have collectively responded over the short term and long term to threats that disrupt our routines, lives, and even the fabric of society.

Literature, classics, and the arts also provide an avenue to explore the effects of social crises. Laura E. Tanner’s blog post explores the works of author Marilynne Robinson. According to Tanner, these works provide us with tools for coping during lockdown by exploring the familiar, whilst her characters also navigate the threat of mortality and how trauma disrupts the comforts of the everyday.

In her chapter “Post-Ceasefire Antigones and Northern Ireland”, Isabelle Torrance traces the evocation of Antigone in the context of the Northern Irish conflict. In this way, literature provides a mirror to explore and process contemporary social crises.

Music history also provides a window into past responses to social traumas. In her chapter “Embodying Sonic Resonance as/after Trauma – Vibration, Music, and Medicine”, Jillian C. Rogers shows that interwar French musicians understood music making as a therapeutic, vibrational, bodily practice which offered antidotes to the unpredictable and harmful vibrations of warfare.

Living through extraordinary timesAs the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects have spread across the globe, nations and individuals have adapted rapidly to dramatic shifts in how we experience the world.

Recent history can provide a fascinating insight into how communities have lived through extraordinary times in the past. In Pandemics, Publics, and Narrative, the authors explore how the general public experienced the 2009 swine flu pandemic by examining the stories of individuals, their reflections on news and expert advice given to them, and how they considered vaccination, social isolation, and other infection control measures.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, historians have considered how we will write the histories of 2020. In “Documenting COVID-19”, Kathleen Franz and Catherine Gudis explore people’s keen awareness of the “historic” moment in which we are living, and the questions it poses for historians: how do we ethically document our current social, public health, and economic crises, and in doing so help to dismantle structural inequalities?

In her article “Slow History”, published in The American Historical Review, Mary Lindemann asks whether the pandemic provides an opportunity to evaluate the “doing” of history and to isolate what really matters in research, writing, and instruction. Arguing that we should learn to value a slow, painstaking approach to our work, Lindemann argues that “historians are, after all, long-distance runners not sprinters.”

Among the many frontline workers enduring the COVID-19 pandemic are social workers, who continued to support people through a period of unprecedented change. A 2020 article from Social Work—“Voices from the Frontlines: Social Workers Confront the COVID-19 Pandemic”—explores how these key workers operated in the US, how they were coping with their own risks, and how social work as a profession anticipated the needs of vulnerable communities during the early stages of the US health crises. The pandemic has also presented specific challenges for social workers interacting with children; a paper from Children & Schools delves into nine ethical concerns facing school social workers when they must rely on electronic communication platforms.

A philosophical approach allows us to explore human emotions and ethics during major world threats. In their chapter on “Emotional resilience”, Ann Cooper Albright explores resilience in the face of threats—from natural disasters to school bullies—finding that emotional resilience provides the opportunity for lasting transformation: “often in returning and remembering, we find that we no longer want what we had before.“

The road to recoveryLiving through these extraordinary times, the COVID-19 pandemic poses some important questions for the future. How do we rebuild from the economic, social, and emotional traumas of the past?

Charlotte Lyn Bright’s Social Work Research article considers the vital role social workers play in supporting society and individuals by looking at the unique skills they employ in their work during difficult times. Meanwhile, in her paper on “Community development in higher education”, Lesley Wood explores how academics can ensure their community-based research makes a difference by discussing the socio-structural inequalities that influence community participation.

In piece for the OUPblog, Nicole Hassoun calls for universal, legally enforced human rights access to essential medicines and healthcare, arguing that, “protecting human rights can help us increase our Global Health Impact.”

The study of the past provides a vital tool to help societies rebuild in the future. In “Making Progress: Disaster Narratives and the Art of Optimism in Modern America”, Kevin Rozario examines the role of disaster writings and “narrative imagination” in helping Americans to conceive of disasters as instruments of progress, arguing that this perspective has contributed greatly to the nation’s resilience in the face of natural disasters.

In this blog piece “Listen now before we choose to forget”, oral historian Mark Cave describes how memory is pliable; our recollections are continually reshaped by our own changing experiences and the influence of collective interpretations. In 2020, Cave writes, the Black Lives Matter protests, divisive partisan politics, and anger over extended lockdowns were all influencing our memories of the pandemic. Cave further explores an oral history project conducted among New Orleans residents following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which “filled a deep need within our community to reflect and make sense of the experience of the storm and its aftermath.” Cave’s research will be vital for future historians considering how to study and understand the COVID-19 pandemic “at a time when history is clearly ‘in the making’.”

Literature continues to provide our society with a tool to understand and process trauma. In her blog post “Why literature must be part of the language of recovery from crisis”, Carmen Bugan explores trauma and social recovery in poetry, and its pertinence during the COVID-19 crises.

Pandemic life has underscored how digital technology can foster intimate connections. Research from Nathan Rambukkana discusses how this influx of digital connection has fostered a mode of interaction know as “distant sociality,” and asks whether this is here to stay following life under lockdown.

Looking much further to the future, Pasi Heikkurinen discusses the end of the human-dominated geological epoch and the potential technological advances needed to make a non-human dominated planet sustainable. Heikkurinen’s chapter provides sustainability scholars and policymakers with an opportunity “to deliberate not only on the proper kind of technology or the amount of technology needed, but also to consider technology as a way to relate to the world, others, and oneself.”

The impact of COVID-19 on the global economy is profound, and yet economists must grapple with how this impact will shape the future. In their chapter “The Interactional Foundations of Economic Forecasting”, Werner Reichmann explores how economic forecasters produce legitimate and credible predictions of the economic future, despite most of the economy being transmutable and indeterminate. Meanwhile, in “Why we can be cautiously optimistic for the future of the retail industry”, Alan Treadgold explores the new retail landscape following the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there is unprecedented uncertainty for retail outlets, Treadgold argues “there are substantial opportunities for reinvention also.”

Music also has the power to enact social healing and transformation following crises. In their chapter “Unchained Melody: The Rise of Orality and Therapeutic Singing”, June Boyce-Tillman explores therapeutic approaches to singing, finding that “singing has the ability to strengthen people physically and emotionally,” which brings “individuals and communities together in order to provide healing at the deepest level.”

SHAPE researchSHAPE research is an essential component of all societies and will be critical for rebuilding from the global COVID-19 crisis. In “Humanities of transformation: From crisis and critique towards the emerging integrative humanities”, Sverker Sörlin evaluates the efforts to enhance and incentivize the humanities in the among Nordic countries in the last quarter century, finding a far richer and more complex image of quality in the humanities following structural education reform in 1990.

Meanwhile, Jack Spaapen and Gunnar Sivertsen assess the societal impact of SHAPE subjects, arguing that the social sciences and humanities have an obligation to assist the main challenges faced by people and governments.

As governments, universities, and research institutions consider where and how they focus their efforts as the world tentatively begins to explore the idea of recovery, the range of research that we’ve gathered here demonstrates that, while science and technology must play a crucial role, a recovery without SHAPE will be no recovery at all.

Featured image by Ryoji Iwata via Unsplash

August 13, 2021

Native conquistadors: the role of Tlaxcala in the fall of the Aztec empire

The Spanish invasion of Mesoamerica, leading to the collapse of the Aztec empire, would have been impossible were it not for the assistance provided by various groups of Native allies who sensed the opportunity to upend the existing geopolitical order to something they thought would be to their advantage. No group was more critical to these alliances than the Tlaxcaltecs. From their city-state of Tlaxcallan, roughly corresponding to the contemporary Mexican state of Tlaxcala (figure 1), the Tlaxcaltecs had successfully resisted incorporation into the empire for decades prior to the Spanish arrival. They made the fateful decision to join the bearded foreigners and offer tens of thousands of seasoned warriors, tactical knowledge of the local landscape and military practices, and food and safe harbor during the Aztec-Spanish War. Following it, the Tlaxcaltecs advocated for their semi-autonomy from Spain as a recognized “Indian Republic” during the remainder of the sixteenth century, while also continuing to assist in wars of conquest from Central America to the Southwestern United States. Who were these key actors and how does their initial encounter with the expedition, led by Hernando Cortés, dispel common myths in what has traditionally be known as the “conquest of Mexico”?

Figure 1. Map depicting entry route into Tlaxcala, with battle sites of Tecoac and Tzompantepec, and continued route to Tenochtitlan, retreat to Tlaxcallan, and final assault on the Aztec capital by the joint Spanish-Mesoamerican forces. Map by David Carballo.

Figure 1. Map depicting entry route into Tlaxcala, with battle sites of Tecoac and Tzompantepec, and continued route to Tenochtitlan, retreat to Tlaxcallan, and final assault on the Aztec capital by the joint Spanish-Mesoamerican forces. Map by David Carballo.I have been fascinated by researching Tlaxcala over the last twenty years, and doing so inspired me to write a book on the violent encounter between Spaniards and Mesoamericans that took place five hundred years ago, titled Collision of Worlds. As an archaeologist, my lens on these events emphasizes elements of the physical world, such as material culture and landscape, and a temporal depth that considers the millennia of societal development on both sides of the Atlantic prior to the typical focal period of 1519–1521. The relevant texts from the period have been reinterpreted by historians since the sixteenth century and remain critical to any retelling of these events. Yet through archaeology we also gain the tangible authenticity of a historical understanding that includes the houses people lived in, the things they used in their daily lives, and the terrain they navigated (figure 2). Together with colleagues such as Keitlyn Alcantara and Aurelio López Corral, I have considered the archaeology of this encounter and its legacies today in how people commemorate and identify with it.

Figure 2. Landscape of the entry point into Tlaxcala near Tecoac. Photo by David Carballo.

Figure 2. Landscape of the entry point into Tlaxcala near Tecoac. Photo by David Carballo.Among the prevalent myths that historian Matthew Restall calls out in his book Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest is that Cortés and a mere 500 Spaniards toppled the Aztec empire, due to some combination of superior military technology, tactical skill, and courage. This blatant falsehood ignores the contributions of tens of thousands of Mesoamericans in driving historical change, whether as skilled guides, fierce warriors, or savvy translators. The myth of the small but heroic group of Spaniards emerged from historical narratives penned by Europeans and Euro-Americans. Within Mexico and other parts of Mesoamerica, the contributions of Native peoples have been appreciated for centuries but, in pushing back against the narrative, have generated a corollary myth: that Native allies, especially the Tlaxcaltecs, were “traitors” to their people. The initial encounters between the people of Tlaxcala and the Spaniards provide an excellent example of how a more critical reading of history that includes archaeology can help us to dispel these sorts of myths.

Eyewitness accounts by Cortés and other conquistadors report that they entered Tlaxcallan in early September of 1519, having begun this part of the expedition from the town of Ixtacamaxtitlan—still occupied today in the north of Puebla. They arrived through a forested pass called Iliyoacan (“place of abundant alder trees”) where they encountered a few Otomis, who inhabited Tlaxcala’s northern frontier and whose descendants in the area today call themselves Hñähñu or Yühmu. This initial encounter was followed by battles with the Otomi and the larger forces of the Nahuatl-speaking Tlaxcaltecs at Tecoac and Tzompantepec, the latter still a town in central Tlaxcala. Our archaeological excavations have focused primarily on earlier time periods, but populations in central Mexico were the highest during the Postclassic (“Aztec”) period and, as a result, we have also recovered pottery and other materials from sites just outside of Tecoac and Tzompantepec (figure 3). The analysis of the first by Laura Heath-Stout shows that the northern Otomis had slightly different trade contacts from the Tlaxcaltec but were very much tied into the commercial and stylistic networks of the day; they were far from peripheral ruffians. The prehispanic alliance between these two groups also attests to the sorts of indirect control that Native politics observed—where one city-state, even Tenochtitlan as an imperial capital, might build its power through alliances or conquests but didn’t seek to directly control the politics, religions, or economies of others, just to establish their own dominance and tax their subjects. This was a very different model from the direct control empire that Spain was beginning to impose in the Americas, and the difference in understanding of how politics worked explains why Native allies to the Spaniards expected different outcomes from assisting the foreigners.

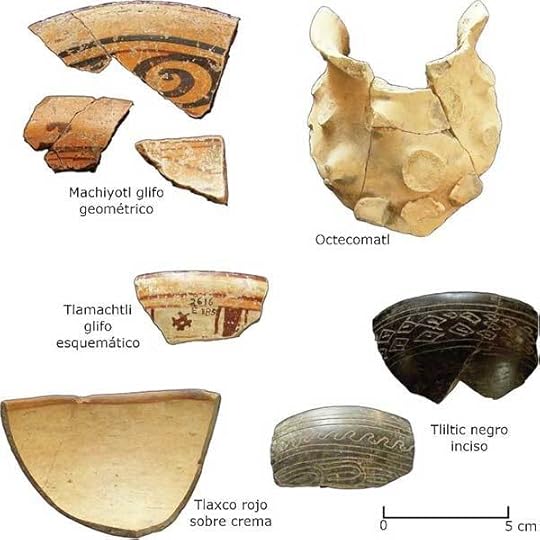

Figure 3. Pottery types excavated near Tecoac. Photo by Laura Heath-Stout and used with permission.

Figure 3. Pottery types excavated near Tecoac. Photo by Laura Heath-Stout and used with permission.To counter the Eurocentric narratives of these events we can look to pictorial manuscripts illustrated by Otomi and Tlaxcaltec scribes, often with accompanying hieroglyphic and alphabetic texts. The most textually detailed of these is the Historia de Tlaxcala, compiled by the mestizo (mixed ancestry) historian Diego Muñoz Camargo, who sailed from Mexico to Spain in order to present a history of his people to the King Phillip II. This was part of a larger effort on the part of the Tlaxcaltecs to portray themselves as having been steadfastly loyal to Spain, as a means of negotiating some autonomies within the exploitative system of colonial New Spain. The text is accompanied by illustrations such as the entry through Iliyoacan (figure 4), depicting an alder tree as a place-name, Cortés on horseback, the Native translator Malintzin as interlocutor, and local inhabitants (Otomis or Tlaxcaltecs) gifting provisions, rather than the armed conflict we know occurred from other sources.

Figure 4. Depiction of initial encounter at Iliyoacan from the Historia de Tlaxcala, showing locals of Tlaxcala provisioning Cortés with turkeys and other local foods and Malintzli and an alder tree in center. Drawing by Pedro Cahuantzi Hernández and used with permission.

Figure 4. Depiction of initial encounter at Iliyoacan from the Historia de Tlaxcala, showing locals of Tlaxcala provisioning Cortés with turkeys and other local foods and Malintzli and an alder tree in center. Drawing by Pedro Cahuantzi Hernández and used with permission.We are presented with a very different image of this initial armed encounter at Tecoac and Tzompantepec in the Otomi-authored Huamantla Map, a large (23 x 6 ft) rendition of the history and sacred landscapes of the people of this region, dating from the later sixteenth century but illustrated on bark paper in a very prehispanic style. David Wright-Carr discusses how the large size of the map would have lent itself to oral accounts of Otomi history and its embodiment through performance with the map as a backdrop. By scrolling through the digitized document, one can appreciate a narrative that includes the origins of the Otomi as a people in a sacred cave located somewhere to the northwest (page 6); their migration eastward passing the ruined pyramids of the pre-Aztec city of Teotihuacan, where the Fifth Sun of creation was set into motion (page 1); various episodes of Otomi political history (pages 2-4); and the arrival of the Spaniards (page 5). The painted scene on the upper right corner of this page presents a very different history from the Tlaxcaltec depicted in illustrations of the Historia de Tlaxcala and related Lienzo de Tlaxcala. Native peoples also engaged in the diplomacy of gifting and supplying the Spaniards but are also shown being decapitated by bearded conquistadors on horseback, in what is a much bloodier rendition of the initial encounter, one indicating armed conflict and resistance prior to the alliance and eventual invasion of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

The combination of archaeology and Native texts from Tlaxcala thereby provide a counternarrative to Eurocentric history and simplistic myths of courageous conquistadors or treasonous Tlaxcaltecs—one in which Indigenous and colonizing understanding of alliance were misaligned and where strategic actors marshalled history in navigating this violent encounter and its colonial aftermath.

August 11, 2021

Word namesakes, also known as homonyms

Several weeks ago (21 July 2021), I posted an essay on homonyms and promised to develop this theme further. No one urged me to do so, but the subject is so rich that even without encouragement I think I have the right to return to it.

Some homonyms are truly ancient: the words in question might sound alike or be nearly identical more than a millennium ago. But more often a newcomer appears from nowhere and pushes away his neighbors without caring for their well-being. This is especially true in the realm of monosyllabic words, which tend to be sound-imitative or sound symbolic. Think of dud. Such formations (one syllable beginning with and ending in the same consonant, usually b, d, g, or p, t, k: bib, gig, gag, pip, pop, pup, tit, tat, kick, cock, and the rest) are a nightmare to an etymologist. They can be coined at any time and mean almost anything. Examples abound. Dud is only one such. In dialects, dud is not too different from dude, a word that has been discussed in minute detail. Dud means “a contemptible person” and “a worthless object.” Then, of course, we have duds “clothes; rags, tatters.” Dud “coarse cloak” turned up in the sixteenth century, and dud “worthless object” three hundred years or so later. Are we dealing with two words or with two senses of one symbolic “unit”? Chronology is of course a significant factor, but such words often linger in rural speech and popular usage (let alone low slang) “forever,” without becoming known to the rest of the world. A lexicographer and an etymologist are at a loss about how to organize the entry.

Identical but different. (Image via Instagram: @saylerstwins.)

Identical but different. (Image via Instagram: @saylerstwins.)Or take dock, another monosyllable (a dock for ships). In the fourteenth century, the word came to English from Dutch or Low (= northern) German, where its origin is lost. Once again, we have a sound complex that may mean practically anything (like duck or dick), and indeed, side by side with this dock, stands dock “part of a horse’s tail.” The earlier meaning of this dock seems to have been “bunch, bundle.” Finally, dock “herb” exists. All three traveled from language to language (when the meaning is almost arbitrary, why stay at home?). Their antiquity (dock “herb” surfaced in Old English, the other two in the fourteenth century) explains nothing and proves nothing except that the sound group dock can designate various objects, most of them solid.