Oxford University Press's Blog, page 102

July 13, 2021

Navigating digital research methods: key principles to consider

I was approached by Epigeum to review their existing research methods courses and explore the possibility of helping to develop a new course that would provide an introduction to research methods. In particular, they were interested in updating the existing courses and providing new material to cover digital research methods.

It was an intriguing prospect: I have taught research methods courses at university for a number of years and have written books on research methods and teaching research methods. My latest book was specifically on digital research methods.

We liaised and the ideas developed. Yes, it was a very good idea to develop a course that introduced research methods, and yes, it was extremely important to include digital research methods. Would I be able to write the course? Yes!

The new course developed gradually: it was to cover the principles of research methods. I had to go back to the basics: what, exactly, did learners need to know when they were introduced to research methods? Do learners from all disciplines need to know the same things? What would go in the course: what would be left out? How would digital research methods be incorporated? Ten principles emerged from these questions.

What are these principles?Studying the nature of human knowledge and how it is acquired. Understanding the nature and structure of the world and how it can be articulated. Relating these issues to research design and goals, choice of methodology, type of theory generation and the way that knowledge is built.Developing a clear, concise and well-formulated question around which research is focused. Generating aims and objectives. Avoiding personal prejudice, assumptions or bias when producing a research question and aims and objectives.Knowing about and choosing a suitable research methodology (the guideline system or framework for research). Understanding the difference between methodology and method. Justifying and defending the chosen methodology.Knowing about a variety of qualitative, quantitative and mixed research methods and digital research methods. Understanding how choice of research method is framed and guided by methodology.Understanding sampling techniques and procedures, choosing sample sizes and overcoming sampling problems and dilemmas.Knowing about and choosing data analysis methods for qualitative, quantitative or mixed data. Choosing and using data analysis software and tools.Reflecting on the different types of connection that can be made between and across disciplines (interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary research, for example).Knowing how to identify and address data protection and security challenges and produce a data management plan.Communicating research using a variety of communication, dissemination and publishing methods, platforms and channels. Identifying and addressing potential challenges when communicating research.Producing and submitting a successful research proposal.That was summer 2019: we had no idea how important digital research methods and working online would be, nor how relevant and timely course content would become.

For example, I thought it would be very useful for learners to follow three examples of researchers working their way through each principle. One of these researchers is conducting research into tools that can be used to trace contact for respiratory disease infection. These tools include a survey (questionnaires completed by an individual, covering who they come into contact with) and wearables, in the form of a badge or wristband (with embedded sensors that record levels and time of contact). At the time of developing this character, the novel coronavirus in humans had not been identified.

The digital research methods provided in this example, and in other examples given in the course, illustrate that there are many possibilities available for research, despite limits on face-to-face contact. With these new possibilities, however, come increased ethical implications.

Informed consentIn social network analysis what does a researcher do when the person identifying their social network has given consent, but others within the network have not given consent?In wearables-based research, what happens in cases where the wearer records others who are not part of the study?How can researchers address issues of informed consent when data are collected through methods about which participants are unaware (location tracking and data mining, for example)?Confidentiality and privacyWhen using mobile phone interviews, how can researchers maintain confidentiality and privacy when participants choose to conduct their conversations in public places?How can researchers ensure confidentiality and privacy when participants may not have the same concerns (when they are used to sharing mobile data with friends, family and organisations, for example)?Do software companies have a clear and robust privacy policy regarding the collection, use and disclosure of personally identifiable information?Anonymity and online identitiesHow can researchers cite information found online (from blogs and social networks, for example) yet respect anonymity and online identities?How might individuals present themselves differently in public and private online spaces?Have does the online identity and presence of the researcher influence the investigation?The inevitable move to online study and digital research in the face of limited contact and movement opens up huge possibilities. Digital methods enable us to reach a wide audience, across geographical boundaries and in places that may be hard to access. They can be cheaper, quicker and more efficient than traditional face-to-face methods.

However, not all data are freely and equally available in the digital environment. Individuals might produce public and/or private data, and commercial organisations might restrict access or provide only partial access to data.

We must all become familiar with rules and regulations about what, when and how digital data can be used for research purposes. We also need to think about how partial, restricted or limited accessibility might affect our research design and methods. And, most importantly, we must ensure that all ethical implications are identified and addressed, and that issues of integrity and scholarship are at the forefront of our digital research and study.

July 11, 2021

The VSI podcast season two: Homer, film music, consciousness, samurai, and more

The Very Short Introductions Podcast offers a concise and original introduction to a selection of our VSI titles from the authors themselves. From Homer to film music, the Gothic to American business history, listen to season two of the podcast and see where your curiosity takes you!

Homer In this episode, Barbara Graziosi introduces Homer, whose mythological tales of war and homecoming, The Iliad and The Odyssey, are widely considered to be two of the most influential works in the history of western literature.

In this episode, Barbara Graziosi introduces Homer, whose mythological tales of war and homecoming, The Iliad and The Odyssey, are widely considered to be two of the most influential works in the history of western literature.

Listen to “Homer” (episode 25) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

CalvanismIn this episode, Jon Balserak introduces Calvinism, which has gone on to influence all aspects of contemporary thought, from theology to civil government, economics to the arts, and education to work.

Listen to “Calvanism” (episode 26) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

CanadaIn this episode, Donald Wright introduces Canada, a country of complexity and diversity, which isn’t one single nation but three: English Canada, Quebec, and First Nations.

Listen to “Canada” (episode 27) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Film music In this episode, Kathryn Kalinak introduces film music, which began as an accompaniment to moving pictures and is now its own industry, providing a platform for expressing creative visions and a commercial vehicle for growing musical stars of all varieties.

In this episode, Kathryn Kalinak introduces film music, which began as an accompaniment to moving pictures and is now its own industry, providing a platform for expressing creative visions and a commercial vehicle for growing musical stars of all varieties.

Listen to “Film music” (episode 28) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

American immigrationIn this episode, David Gerber introduces immigration, one of the most contentious issues in the United States today which has shaped contemporary American life and fuels strong, divisive debate.

Listen to “American immigration” (episode 29) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

ConsciousnessIn this episode, Susan Blackmore introduces the last “great mystery for science”—consciousness and the questions it poses for free will, personal experience, and the link between our mind and body.

Listen to “Consciousness” (episode 30) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Samurai In this episode, Michael Wert introduces samurai, whose influence in society and presence during watershed moments in Japanese history are often overlooked by modern audiences.

In this episode, Michael Wert introduces samurai, whose influence in society and presence during watershed moments in Japanese history are often overlooked by modern audiences.

Listen to “Samurai” (episode 31) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

The GothicIn this episode Nick Groom introduces the Gothic, a wildly diverse term which has a far-reaching influence across culture and society, from ecclesiastical architecture to cult horror films and political theorists to contemporary fashion.

Listen to “The Gothic” (episode 32) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

The animal kingdomIn this episode, Peter Holland introduces the animal kingdom and explains how our understanding of the animal world has been vastly enhanced by analysis of DNA and the study of evolution and development in recent years.

Listen to “The animal kingdom” (episode 33) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

American business history In this episode, Walter A. Friedman introduces American business history and its evolution since the early 20th century when the United States was first described as a “business civilization.”

In this episode, Walter A. Friedman introduces American business history and its evolution since the early 20th century when the United States was first described as a “business civilization.”

Listen to “American business history” (episode 34) via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Subscribe to The Very Short Introductions Podcast and never miss an episode!

July 10, 2021

A Roman road trip: tips for travelling the Roman Empire this summer

As Europe reopens, consider a Roman road trip that takes inspiration from an ancient travel guide. The Vicarello itineraries describe what we might call the scenic route from Cádiz to Rome. Glimpses of the empire’s superlative architecture can be found along the way, and emerging digital tools can put primary sources at your fingertips.

Tools for traveling like a RomanUse your preferred mapping tool to navigate the modern highway and let ORBIS plot a parallel journey along Roman roads. ORBIS, meaning “world” in Latin, is a geospatial model of the Roman transit system. Just enter your origin and destination and choose your season of travel. You can even compare modes of transit in terms of time and cost, in case you are wondering how your ancient counterpart would have fared by foot or by carriage. The trick to using ORBIS is knowing what Romans called the places you want to visit, and to that question Pleiades provides answers. Named for the mythical constellation, Pleiades is an online atlas of ancient Mediterranean places. Just type the ancient placename in a general search or the modern placename in an advanced search, and the resulting entry will tell you how the name has changed over time: the city we call Cádiz, for instance, the Romans called “Gades.” Pleiades entries also link related resources, such as Topostext, which will tell you what your favorite Roman author had to say about your destination.

Sites Romans visited, from Spain to ItalyWith a dazzling seaside setting, Cádiz (Gades) is a delightful place to begin a journey. Founded by Phoenicians, the city was one of the oldest in the Roman realm. The site’s multi-cultural history can be traced in person at the Museo de Cádiz and from afar via Google Arts and Culture. Don’t miss the Phoenician gold, the statues of Roman emperors, or the ancient graffito of a lighthouse. Little from antiquity survives around town, aside from the impressive theater. This was one of the earliest in Roman Spain and had as its patron Lucius Cornelius Balbus the Elder, who rose to the office of consul during the Roman Republic. Follow his potential path to Rome and witness imperial transformations. Seville (Hispalis) has one of Spain’s largest archaeological museums. At Córdoba (Corduba), the theater is preserved in the archaeological museum’s basement, and tombs and a temple can still be seen in the cityscape. Further afield is Tarragona (Tarraco), with a circus and amphitheater overlooking the sea, and another of Spain’s fantastic museums.

Theater of Balbus at Cádiz, Spain

Theater of Balbus at Cádiz, SpainOn the other side of the Pyrenees, Nîmes (Nemausus) beckons. Recent cleaning campaigns have restored sparkle to the amphitheater and the influential temple known as the Maison Carrée. The surviving Roman gates called the Porte d’Auguste and the Porte de France highlight the boundaries of the ancient city within the modern one. The recently unveiled Musée de la Romanité has glass walls, an undulating design intended to resemble a toga, and great views of the amphitheater. Collection highlights include rare statues from the era of Gallic rule, as well as spectacular Roman paintings, mosaics, and sculptures salvaged during urban construction work. Just beyond Nîmes is the breathtaking aqueduct known as the Pont du Gard. Nearby sites also lie on the Vicarello route. Arles (Arelate) has an amphitheater, a theater, and an excellent museum. Glanum is a mini-Pompeii nestled in the Alpilles foothills.

Amphitheater at Nîmes, France

Amphitheater at Nîmes, FranceBeyond the Alps, the Vicarello itineraries take you through Susa (Segusio), Turin (Augusta Taurinorum), and Bologna (Bononia), before reaching Rimini (Ariminum) on Italy’s Adriatic coast. Excellent signage here highlights the Roman remains, including a gateway, a fragmentary amphitheater, an elegant bridge commissioned by the emperors Augustus and Tiberius, and an arch monument dedicated by the Senate and Roman People (SPQR) to Augustus for repairing the Via Flaminia. Beautiful mosaics can be seen at the recently excavated House of the Surgeon, while other striking finds from the city are displayed at the nearby museum.

SPQR Arch for Augustus at Rimini, Italy

SPQR Arch for Augustus at Rimini, ItalyDepart Rimini via the arch for Augustus, and let the Via Flaminia take you to Rome. Start at the Crypta Balbi, part of a theater complex constructed by Lucius Cornelius Balbus the Younger from Cádiz. Then walk to the nearby Pantheon, constructed by the emperors Trajan and Hadrian (both from Italica, a suburb of Seville). The Pantheon’s many adjacent cafés offer ideal settings for reminiscing. Did you prefer the design of the Pantheon or the Maison Carrée? Was the sea more beautiful at Cádiz or Rimini? With these sites in mind, conclude with a visit to the Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Massimo, where the four silver cups engraved with the Vicarello itineraries are displayed in the basement. With gallery openings here and elsewhere still subject to pandemic protocols, be sure to inquire ahead. If you need to plan a return trip, remember that the Roman Empire is always best viewed from the road.

Feature image by Kimberly Cassibry

July 9, 2021

Whitman and the America yet to be: reconceptualizing a multiracial democracy

My research on the ten years that Whitman lived in Washington, DC, (1863-1873) led to my argument in Whitman in Washington: Becoming the National Poet in the Federal City that his experience with the federal government—its bureaucracy, its hospitals, its soldiers, its efforts to realize the proposition that all men are created equal—transformed him. His identity as the poet of America was of course formed while he lived in Brooklyn and wrote Leaves of Grass (1855), but what has often seemed to many to be a loss of his early political and poetic radicalism after the war is better understood as his own effort to reconceptualize a multiracial democracy. His failures, and his successes, parallel those of the federal government and the Union itself.

As an example, consider his “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors,” a poem first published in 1871 and slightly revised a decade later to take its final form:

WHO are you dusky woman, so ancient hardly human,

With your woolly-white and turban’d head, and bare bony feet?

Why rising by the roadside here, do you the colors greet?

(‘Tis while our army lines Carolina’s sands and pines,

Forth from thy hovel door thou Ethiopia com’st to me,

As under doughty Sherman I march toward the sea.)

Me master years a hundred since from my parents sunder’d,

A little child, they caught me as the savage beast is caught,

Then hither me across the sea the cruel slaver brought.

No further does she say, but lingering all the day,

Her high-borne turban’d head she wags, and rolls her darkling

eye,

And courtesies to the regiments, the guidons moving by.

What is it fateful woman, so blear, hardly human?

Why wag your head with turban bound, yellow, red and green?

Are the things so strange and marvelous you see or have seen?

Like most of Whitman’s poetic reflections on the Civil War, it is notable for not directly addressing slavery, or emancipation, or civil rights, or even the sacrifices of the black soldiers whom Whitman cared for in Washington hospitals. It does not in any explicit way express the poet’s sympathy with fugitives, or the enslaved, as he had in 1855.

However, Whitman does speak in the poem as the black woman, a device that recalls his very powerful claim of 1855 to represent the silenced:

Through me many long dumb voices,

Voices of the interminable generations of slaves,

Voices of prostitutes and of deformed persons,

Voices of the diseased and despairing, and of thieves and dwarfs,

Voices of cycles of preparation and accretion,

And of the threads that connect the stars—and of wombs, and of the fatherstuff,

And of the rights of them the others are down upon,

Of the trivial and flat and foolish and despised,

Of fog in the air and beetles rolling balls of dung.

Through me forbidden voices,

Voices of sexes and lusts . . . . voices veiled, and I remove the veil,

Voices indecent by me clarified and transfigured.

To do so, he employs Black dialect, which White writers often wielded as a comic or satirical device. Indeed, one of the standard tropes of the war was the elderly, often caricatured female slave in a kerchief, who watches from the porch of a grand southern plantation the march of Union troops, their arrival promising her, too, a new mobility. Whitman’s imagining of the interaction between an African American woman and Sherman’s army was almost certainly shaped by such depictions in the popular press.

But his poem is both less politically programmatic and less racist than Harper’s Weekly cartoons. The white soldier baldly states what most European Americans believed: people from Africa, like the elderly woman he observes, were “hardly human.” But the woman herself contradicts this, and might even be described as more than human. That is, she has a venerable antiquity, not only in her appearance, but in her poetic diction (internal rhymes, chiasmic heroic simile, inversions like “caught me as the savage beast” which speaks back to and disputes the soldier’s claim that she is “hardly human”). Ethiopia was understood as the ancient birthplace of African civilization, and this woman is Ethiopia. She has survived, then, despite the savagery of the Middle Passage, still proudly wearing the colors of her African past. If her hovel sounds derogatory to modern ears, to Whitman’s peers it spoke of poverty to be sure, but also of a kind of peasant independence—she is not a worker on someone else’s plantation, but has her own place.

Situating that place on Carolina sands points directly to the question mark hanging over Ethiopia’s future. General Sherman’s famous Field order of 16 January 1865, gave African Americans “possessory rights” to a strip of coastland stretching from Charleston, South Carolina to northern Florida. By the time Whitman wrote, he knew that promise of land (land confiscated from fleeing whites) had been rescinded, and his Ethiopia greets the “colors” of the Sherman’s army with full understanding that her path forward will be on shifting sands. As she watches the guidons—a medieval-flavored word for the pennants of a military company—the question of whether and how her colors, her loyalties, her arms, will march forward with them, whether they will share the same road, is left uncertain. She has undoubtedly seen the strange and marvelous; will fate allow for the US, too, to be marvelously transfigured, to undergo a sea change?

Whitman’s work as a clerk in the Department of the Interior and then the Attorney General’s office exposed him to the rise of paramilitary groups. He inscribed at least thirty letters treating the Ku Klux Klan when he served as a clerk copying letters in the latter’s office. He saw both the federal government’s efforts to expand American citizenship in the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments, and its failure to reconstruct society along anything but segregated and unequal ground. His correspondence even suggests that he accepted this result matter of factly; in his prose book of 1871, Democratic Vistas, he was unsuccessful in rebutting Thomas Carlyle’s cynical claim that the United States was doomed in trying to achieve a multiracial rather than ethnically homogenous nation. But deliberately, in his poetry, inserting “Ethiopia” into Leaves of Grass in 1871 and thenceforward, Whitman kept alive the idea that on Carolina sands, within the American republic, the colors of all the nations could greet each other proudly and courteously. Perhaps that is why Langston Hughes called this poem “one of the most beautiful poems in our language concerning a Negro subject.” If Whitman’s self-styled claim to be the poet of democracy has any merit, it lies in his ability to evoke more hopeful vistas, or as Hughes put it so wistfully,

O, let America be America again—

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where every man is free.

Feature image: Portret van de dichter Walt Whitman. Via Wikimedia Commons

Shakespeare and the sciences of emotion

What role should literature have in the interdisciplinary study of emotion? The dominant answer today seems to be “not much.” Scholars of literature of course write about emotion but fundamental questions about what emotion is and how it works belong elsewhere: to psychology, cognitive science, neurophysiology, philosophy of mind. In Shakespeare’s time the picture was different. What the period called “passions” were material for ethics and for that part of natural philosophy dealing with the soul; but it was rhetoric that offered the most extensive accounts of the passions. This—to us strange—disciplinary situation had ancient roots: Aristotle’s most expansive discussion of the passions appears in his Rhetoric. Since early modern literary theory was based on rhetoric, this forges a direct relationship between literature and the study of passions.

What does it mean to think about passion rhetorically? One answer takes us to a famous Hamlet soliloquy:

Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That from her working all his visage wann’d,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in his aspect,

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing! (2.2.545–51)

This is about more than effective performance: it encodes an account of the cognitive underpinnings of passion that emphasizes the rhetorical functioning of the mind. The “fiction” Hamlet is thinking of is a mental fiction: a “conceit” or phantasm, which is a fiction in the sense that it is a made thing: a product of our souls. In the sequence traced here, an imagined conceit alters the soul and that alteration in turn alters the body. All passions are fictional in the sense that all are based on “nothing”: that is, on mental images. A second sense of “fiction” is relevant as well: fiction as that kind of made thing that is an invented story. The actor describes Hecuba at the fall of Troy; in doing so, he is both himself moved and moves those who hear him. The transmission of passion is not a secondary issue separate from what passion “is” but follows directly from passion’s relation to imagination: that is, its “fictional” standing. Literature can address the passions because passions are quasi-mimetic: they are ways of seeing and evaluating the objects of our concern.

The knowledge produced by a rhetoric of the passions is remote from what the early modern period called “scientia”: certain, demonstrative knowledge of universals. Even Aristotle’s chapters on the passions in the Rhetoric do not offer anything like that: they give brief definitions of each passion, but mostly offer ramified lists of the kinds of situations producing each. Early modern writers expanded on such accounts. The second edition of Thomas Wright’s Passions of the Mind—printed 1604, the same year as Q2 Hamlet—spends nearly 20% of its length surveying the “motives to love”: the means to move love in others. The discussion is divided into seventeen topics, from pardoning of injuries to gift-giving; that last is subdivided into fourteen further “circumstances,” addressing the nature of the gift, the giver, and the receiver, and the specifics of how the gift is given. There is nothing finished about either list: one could easily add more motives, more circumstances. And this is the point. Since passions are responses to the situations in which we find ourselves, they vary in as many ways as those situations vary. According to a common early modern phrase, passions are “accidents” of the soul, where “accident” means both a contingent qualitative alteration and an event. We study passions by looking out at the world of events. But the knowledge we can attain in this way is at best probable: as a series of seventeenth-century books argue, passions are caused by their objects; those objects are qualified and circumstanced particulars; they are infinite; and the passions too are infinite. Passions are at the limits of the knowable.

Rhetoric knows the passions by tracing them to their circumstances. That is, it knows them narratively, and it construes narrative as a means of producing knowledge about passions in their particularity. This way of knowing is evoked in Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning: “poets and writers of Histories” have been passion’s “best Doctors”—that is, best scholars—because in them we find depicted “how affections are kindled and incited: and how pacified and refrained: and how again contained from act and further degree: how they disclose themselves, how they work, how they vary, how they gather and fortify, how they are enwrapped one within another, and how they do fight and encounter.”

Bacon wants a natural history of the passions to displace this unsystematic poetic and historical knowledge. It is tempting to say that this is exactly what happened in the next two centuries, as forms of empirical psychology took over a space that once belonged to rhetoric. But it matters that these psychologies reoccupied rhetoric’s terrain. The knowledge they offer is closer to the one Bacon ascribes to poets and historians than to scientia: in the sphere of the passions, rhetoric is the forerunner of an empirical knowledge of particulars. One can trace its continuing if hidden influence on new psychologies from Locke—who recommended Aristotle’s Rhetoric as part of the study of the passions—to Hume and Smith, whose models of the mind echo the psychology of the vivid image articulated by Hamlet and the circumstantial analysis of passions practiced by Wright. Scholars sometimes claim that a “psychological” approach to Shakespeare is anachronistic, because his period had no psychology. That is not entirely accurate, but the main point is that, in a sense, the period’s literature was its psychology: a circumstantial, open-ended, narrative knowledge of the passions grounded in rhetoric. That knowledge, which thrives beyond the limits of any system, still has something to tell us about how we know the emotions now—not as experts, but as people engaged in everyday life.

Feature image: Infant Shakespeare Attended by Nature and the Passions, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949

July 8, 2021

Outlandish but not crazy

The study of language has generated a lot of outlandish ideas: various bits of prescriptive dogma, stereotypes and folklore about dialects, fantasy etymologies, wild theories of the origin of language. Every linguist probably has their own list. When these ideas come up in classes or conversations, I have sometimes referred to them as crazy, wacky, loony, kooky, or nutty. I’m going to try to stop doing that.

It’s not because these ideas have gotten any more sensible. It’s because of those adjectives themselves. Over the years, some of my students shared their own experiences with neurodiversity. A recurring theme is the sting they feel when someone refers to something as crazy or insane or loony.

Thinking about their experiences and reading their essays about the ways in which words have hurt them helped me realize that I can do a better job of talking about foolish ideas when they come up. If I refer to things instead as preposterous, absurd, ludicrous, or ridiculous, I’ll doubtless sound overly professorial and pedantic. That’s a small price to pay. And perhaps being more professorial will encourage me to expand on why the bad ideas are so silly.

I’m probably not going to succeed at first. I’ve been using crazy, wacky, and other terms for a long time—and there are a lot of silly ideas out there in the world. But it is possible to change how you use the words that make others feel devalued if you pay attention to your vocabulary.

One of the ways to pay attention to your vocabulary is by looking into the history of words. Insane is quite literally “not sound of mind.” It seems matter of fact, but it calls up literary images of psychiatric hospitals from works like Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, among many others. We no longer call psychiatric hospitals “insane asylums,” so I feel justified in dropping insane from my casual vocabulary.

Ridding myself of crazy may take more work. The word is deeply entrenched in Modern English and there are some uses I will probably want to keep. Referring to a fad as a craze seems fine to me—that dates from the early nineteenth century. And crazy about, like mad about, can be used when someone is particularly enamored of another person or a thing. Yet when I look it up, I see that crazy goes back to the verb acraze meaning “to crack in pieces” or “be cracked into pieces,” like glass might be. It soon also meant “to be driven mad,” as King Lear was by grief: “The greefe hath craz’d my wits.” The image of crazy as “cracked” and “broken” is going to stick with me.

Loony (which can also be spelled with an “e” as in the long-running Warner Brothers Looney Tunes) is thought to have come about by way of Latin borrowings like lunacy and lunatic, and thus related to things lunar. But this usage may have also been influenced by the English dialect word loun, which referred to a lout or worthless person, and by the bird known as the loon. Unpleasant images all.

Wacky, nutty, and kooky seem less harsh, but I’ll probably still avoid them. Wacky (or whacky, the spelling of with an “h” seems to come and go) found its earliest uses as a synonym for crazy in American slang of the 1930s (even appearing in an issue of The Journal of Abnormal Psychology). The usage is related to the phrase “out of whack,” meaning “disordered” or “malfunctioning.” By the 1950s, its meaning had softened to mean “odd” or “peculiar,” at least when used of people.

As for nutty and nuts, they were first used to refer to zesty seeds. Their piquant nature led their meaning “very fond of” or “infatuated by,” which was later extended to the idea of insanity. Kooky and kook are more recent English words, becoming prominent in the late 1950s and used as the nickname of a hipster character on television’s 77 Sunset Strip. The usual etymology is as a shortening and respelling of cuckoo, like the bird or clock. But another view relates it to the Hawaiian expression kūkae, meaning “feces,” and neophyte surfers were sometimes referred to as kooks.

Word use can change, at a personal level and socially as well. Retarded is no longer used. Nor is the noun clipped from it. The words moron and imbecile too are increasingly rare except in the lowest discourse. However, idiot is still pretty widely used, notably in a popular book series celebrating our collective befuddlement, so we are probably stuck with it.

A word’s etymology is not its destiny of course, but looking at these word histories has reinforced my decision to try to stop referring to the outlandish and eccentric as crazy, insane, loony, wacky, kooky, or nutty. I may not succeed, but I’ll be thinking about where these words come from and how others may take them.

Featured image: “Loons on Lake Wawa” by Helena Jacoba. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Why did evolution create conscious states of mind?

When we open our eyes in the morning, we take for granted that we will consciously see the world in all of its dazzling variety. Likewise, when we consciously hear conversations with family and friends, consciously have feelings about them, and consciously know who they are.

The immediacy of our conscious experiences does not, however, explain how we consciously see, hear, feel, and know; where in our brains this happens; or, perhaps more importantly, why evolution was driven to invent conscious states of mind. I will summarize some of the reasons here, starting with why we consciously see. My answer will propose, in brief, that we consciously see in order to be able to reach.

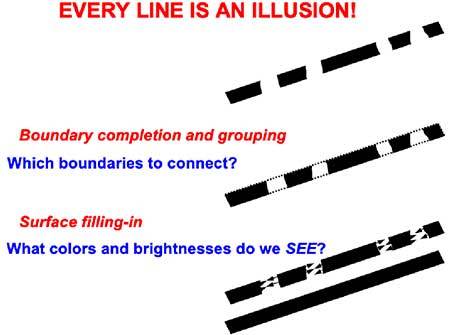

Being able to make an arm movement that reaches a nearby object cannot be taken for granted, if only because of the way our eyes process light from the world. Seeing begins when light passes into our eyes through a lens and hits our photosensitive retinas, much as occurs in a camera. However, our retinas are not manmade. They are made from living cells that need to be nourished at a very fast rate. In addition, the light-sensitive photoreceptors that comprise a retina send their signals to a brain using an optic nerve. These two factors force our retinas to pick up visual signals from the world in a very noisy and incomplete way, as the first two images illustrate.

Figure one (top); figure two (bottom)

Figure one (top); figure two (bottom)Figure one shows a cross-section through the eye, showing the lens on the left and the retina on the right. The photodetectors send their light-activated signals down pathways, called axons. All the axons are collected together to form the optic nerve, which sends all the signals to the brain.

Figure two shows that the part of the retina behind which the optic nerve forms is called the blind spot because there are no photodetectors there. Note that the blind spot is about as large as the fovea. The fovea is where the retina can form images with high acuity. Our eyes move incessantly through the day to point our foveas to look directly at objects that interest us.

In addition, retinal veins that nourish retinal cells lie between the lens and the retina, and thereby prevent light from reaching retinal positions behind them.

We can now begin to understand what it means to claim that conscious seeing is for reaching. This is true because, as illustrated in figure three, visual images are occluded by the blind spot and retinal veins. Even a simple blue line that is registered on the retina is sufficient to illustrate why this is a problem. Suppose that, as in the figure, the blue line passes through positions of the blind spot. Because the blue line is not registered at those positions, without further processing we could not reach for the blue line at any of these positions. The brain reconstructs the missing segments of the blue line at higher processing stages so that we can, in fact, reach all positions along the line. The same problem occurs no matter what object is occluded by the blind spot or the retinal veins.

Figure three

Figure threeThis is not a minor problem because, as I already noted, the blind spot is as big as the fovea.

But what does this have to do with consciousness?!

As I will indicate below, it takes multiple processing stages for our brains to complete representations of images that are occluded by the blind spot and retinal veins. But then how do our brains know which of these processing stages generates a complete enough representation with which to control reliable reaches? Choosing an incomplete representation with which to control actions could have disastrous consequences.

The answer lies in the claim that “all conscious states are resonant states.” I will explain what a resonance is in a moment. For now, the main point is that, a resonance between a complete surface representation of an object and the next processing stage renders that surface representation conscious. Once such a complete surface representation is highlighted by consciousness, it can control actions. And because it is complete, this representation can successfully control accurate reaches to any position on an attended object that is sufficiently near.

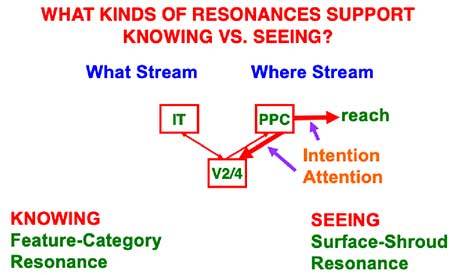

Figure four

Figure fourThe selection of complete surface representations occurs in prestriate visual cortical area V4, which resonates with the posterior parietal cortex, or PPC, to generate a surface-shroud resonance. As illustrated in figure four, spatial attention from the PPC can highlight particular positions of the V4 surface representation via a top-down interaction, at the same time that spatial intention can activate movement commands upstream to look at and reach for a desired goal object.

A resonance is a dynamical state during which neuronal firings across a brain network are amplified and synchronized when they interact via reciprocal excitatory feedback signals during a matching process that occurs between bottom-up and top-down pathways, like the pathways between V4 and PPC. Resonant states focus attention on patterns of critical features that control predictive success, while suppressing irrelevant features. They also trigger learning of critical features—hence the name adaptive resonance—and buffer learned memories against catastrophic (sudden and unpredictable) forgetting.

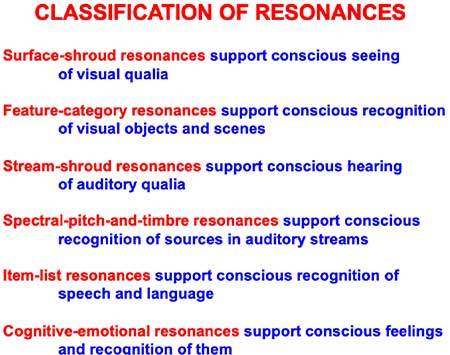

The conscious states that adaptive resonances support are part of larger adaptive behavioral capabilities that help us to adapt to a changing world. Accordingly, resonances for conscious seeing help to ensure effective looking and reaching; for conscious hearing help to ensure effective auditory communication, including speaking; and for conscious feeling help to ensure effective goal-oriented action.

Figure five summarizes six types of resonances and the functions that they carry out in different brain regions.

Figure five

Figure fiveSurface-shroud resonances derive their name from the fact that surface representations resonate with spatial attention that covers the shape of the attended object, a so-called attentional shroud. Surface-shroud resonances support conscious seeing of the object, whereas feature-category resonances support conscious recognition of them. When both kinds of resonances synchronize, we can consciously see and know about familiar objects.

What processes are needed to form a complete surface representation from the noisy retinal images that are occluded by the blind spot and retinal veins? First, the blind spot and retinal veins themselves are removed from this representation. This happens because they are attached to the retina, which continually jiggles in its orbit, thereby creating persistent transient signals on the photoreceptors from objects in the world. Retinally stabilized images like the blind spot and retinal veins fade because they do not cause such transients. Next, our brains compensate for changes in illumination that occur through the day and that could undermine the processing of object shapes. Finally, our brains need even more stages to complete the boundaries and fill-in the surface brightnesses and colors that are occluded by the blind spot and retinal veins, as illustrated by figure six. Conscious states enable our brains to select the complete boundaries and surfaces that result from all of these processes.

Figure six

Figure sixFeature image: S Migaj via Pexels

July 7, 2021

Monthly gleanings for June 2021: odds and ends

Two birds (no stones): fieldfare and sparrow

Two birds (no stones): fieldfare and sparrowIn one of the comments on the etymology of fieldfare (23 June 2021), a reader took issue with my “disdainful demolition” of other points of view. Disdain is not among my vices (decades of research teach one modesty), and being able to reject a wrong solution makes one neither overweening nor smug. For example, I refuse to accept the idea suggested in the comment that –fare in fieldfare means “food.” Though in its present form fieldfare appeared only in the Middle period, its ancestor was known around the year 1100, while fare “food” turned up considerably later. Fare means “passage”; hence the later sense “the food needed for travel.” I cannot find a single bird in any European language in whose name, old or new, a similar idea is present. Fieldfare as “field food” sounds improbable. Also, while proposing an etymology, it is recommended to explain why the previous hypotheses are wrong.

The original meaning of sparrow has been the subject of protracted research. From Classical Greek several words have come down to us: sparásion, sporgílos, and (s)pérgoulos. They resemble the sparrow’s name in the languages all over Eurasia, with or without s- at the beginning (Latin parra, Gothic sparwa, and so forth). Perhaps the word meant “hopper” (if so, then the English verb spurn may be related: its present-day sense “to reject” developed from the concrete sense “to trample”). All the rest is guesswork. (Even, when dealing with such a pair as German Sperling and Spatz, both of which mean “sparrow,” it is not evident that they are cognate. (Russian vorobei is equally tough.)

Aftermath A common bird with an uncommon etymology. (Image by David Friel via Wikimedia Commons)

A common bird with an uncommon etymology. (Image by David Friel via Wikimedia Commons)This is one of the few words about which I will not say: “Of disputed origin.” Math (here) has the same unproductive suffix as in length, breadth, width, strength, warmth, and sloth. In aftermath, the root is a noun related to the verb mow “to cut grass.” Hence aftermath “a second crop of grass (the grass that grew after the first mowing)”; see the picture at the head of the post. The figurative sense has almost superseded the direct one; therefore, the etymology of this word is no longer clear to modern speakers.

Heifer and beyondThe post on heifer (16 June 2021) was no. 800 in this blog. Several readers sent me their greetings on this “anniversary.” My sincere thanks to them and to everybody who has been paying attention to “The Oxford Etymologist.” And I am not a bit surprised that méchant ended up with a wrong accent in that post. Méchant is one of the first French words I learned in my life, but words tend to live up to their etymology and sense (this is a law of my own discovery). How could such an adjective surface without a typo?

From my archiveI have a sizable supply of quotes from newspapers and books, some of which may be interesting to our readers.

Folk etymology: the adjective snide Snide but usable clothes. (Image by Bbensmith via Wikimedia Commons)

Snide but usable clothes. (Image by Bbensmith via Wikimedia Commons)Strangely, next to nothing is known about the origin of this relatively late Americanism, but since a snide remark (for example) is a “cutting” remark, there may (must?) be some connection with the root of such words as Dutch snijden or German schneiden “to cut.” This is what I read in American Notes and Queries, Vol. 4, for 12 April 1890. Someone asked the editor about the etymology of snide defined in the letter as “tricky, worthless, etc.” This was the reply: “I am told that men born in New York can remember in their boyhood a custom by which all tailors were called ‘Schneiders’ by the street boys,” says NY Sun. “Out of that grew the abbreviated word snide, which was at first applied only to cheap or poor clothing such as was made by German tailors in the little side-street shops. Now the word is applied to every mean, poor, or fraudulent thing.” If you have a better conjecture or if you know the origin of the phrase zoot suit, kindly share your information with me.

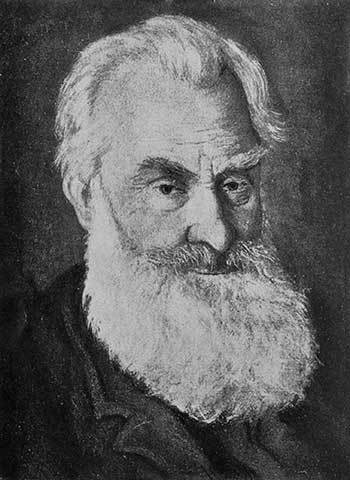

What is good English? T. Adolphus Trollope, 1810-1892, a prolific novelist and a stickler for beautiful English. (Image by Harper and Bros via Wikimedia Commons)

T. Adolphus Trollope, 1810-1892, a prolific novelist and a stickler for beautiful English. (Image by Harper and Bros via Wikimedia Commons)This is a message from T. Adolphus Trollope, one of the most popular writers of his time. It appeared on 29 October 1892, three or four weeks before his death (Notes and Queries, 8th Series, vol. II, p. 357):

“In less vulgar times than these ‘fin de siècle’ days English custom was wont to sanction such modes of speech as writers—recognized to be good writers—and cultured people used. And neologisms became acclimatized and sanctioned slowly. In these days the process is a very much quicker one. Some fool with a very limited vocabulary at his command hears some word or combination of words—possibly a happy and suggestive one, but very far more likely an extremely stupid and ungrammatically constructed—which is new to him, and he forthwith delightedly seizes it and adds to his meagre store. Seven other fools worse than himself hear it, and each of them appropriates it and is in turn imitated, each by other seven spirits of his own kind. Some newspaper reporter, writing in hot haste, picks it up. Others plagiarize the ‘happy thought’. And the trick is done. English custom sanctifies the use of the newest phrase. Words thus not only change, but in some cases altogether lose their proper meaning.”

This is disdain indeed (and I hope the accent in siècle is correct). For decades, I have been telling my students (and once wrote in this blog and was even praised for the sentiment) that the history of language is an extremely interesting subject but that nothing is sadder than to be part of it.

Some things Trollope would probably have winced atThe so-called s possessive is natural when used with names (Tom’s, Dick’s, Harry’s, etc.). We often see it elsewhere (the town’s destruction, the country’s progress, and the like), but here are two examples: “English’s lack of a third-person singular gender-neutral pronoun is a problem centuries old” (from the NY Times Book Review, 2 Febr 2020, p.12). “Investigators… were on the scene well into Tuesday afternoon, but had yet to pinpoint the fire’s origin or cause” (from the Minneapolis Star Tribune). English’s lack, fire’s origin… Isn’t that usage odd? (On the other hand, the misuse of the apostrophe has been ridiculed more than once. I, for example, was delighted to read a recent letter from a person occupying a high post who sent her greetings to all dad’s.)

Long ago, I wrote in this blog that, if I am not mistaken, the split infinitive of the to not do type is an Americanism from the south, because Huck Finn says so six times; only once does he use this construction with always. No one commented on my hypothesis, and no one explained why this type of splitting suddenly became ubiquitous. It is even hard to understand what makes some speaker go to such lengths to make their message incomprehensible. “Our process calls for this type of message to only be sent via email”; “I promised to only write one email a day.” Any thoughts on the subject?

Perhaps you applied for a grant and your application was rejected. Take solace in the following note: “When in January 1932, Dr. Grant, the Editor of the Scottish National Dictionary, appealed for financial aid in his great work to about 270 Burns Clubs, he received one donation of £1.”

Next week, I’ll write about the word beacon (as promised).

Feature image: UGA CAES/Extension via Flickr

Where have you gone, Jimmy Gatz? Roman Catholic haunting in American literary modernism

The year is 1924: the restriction acts designed to turn the tide of Eastern and Southern European immigration into a trickle have been signed into US law. Nativist panic continues apace, however, even among the upper classes, perhaps especially among the educated upper-middle classes—whose strengthened churches and preparatory schools and country clubs guard the Anglo-Protestant marriage market and the not-so-free masonry of finance capital. What is to become of America when these newcomers of swarthy complexion and strange conviction succeed as money-brokers and culture-makers and partners-in-varied-intimacies? In quick succession three titans of US literary modernism weigh in, each with the novel still judged their best: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House (1926), Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926).

Consider, first, their archetypal Jews. In The Great Gatsby, gangster-gambler Meyer Wolfsheim signifies Jewish finance (a.k.a., usury) as the criminality that links the fixed betting of the East-Side underworld to the insider trading of the Oyster Bay elite, the genealogically suspect Gatsby laundering the money of whiteness. In The Professor’s House, venture entrepreneur Louie Marcellus brings Tom Outland’s theoretical physics to industrial market after marrying the fiancée of the deceased war hero—a desecration of Outland’s reputed purity in terms of both dollars and sons. And, in The Sun Also Rises, Robert Cohn’s Princeton credentialing and athletic virility allow him to crash the Anglo-American expatriate partying elite, only to be nastily dismissed for the impassioned show of taking a tryst with affianced Brett to heart—rejection-to-ejection confirming the codes and modes of in-bred whiteness.

In all three novels, what it means to be a Jew is to pose a social threat to the household economies and networked intimacies of the power elite—and the limitedness of that vision, that it is solely an issue of blood and money, may be the most anti-Semitic element of all. In outing anti-Semitism in these novels, no one has noted a simple corollary: in none of them does Jewishness seem to have anything to do with the Hebraic G-D.

Now consider, in a preliminary yet provocative way, the nearly unaddressed figuration of Catholicism in the triptych.

In The Great Gatsby, the one explicit reference to a Catholic identity is a fabrication underscoring Myrtle’s poor-white hope. But Nick’s pointed speculation on Gatsby’s background—the East Side of NY or the swamps of Lousiana?—recalls the original prologue regarding Gatsby’s youth, published separately in 1924. “Absolution” treats a priest in faith crisis, Father Schwartz, and a boy, Rudolph Miller, who is facing the onset of puberty under his father’s viciously doctrinal Irish-German Catholicism. The plot turns on foundational catechetical issues—differences between mortal and venial sin, perfect and imperfect contrition, truth of heart and veracity of speech—that escalate in the transactional dynamics of the Confessional, thrice staged. While young Rudolph decides there is “something ineffably gorgeous somewhere” that has “nothing to do with God,” the concluding death swoon of the priest witnesses, in martyred mysticism, just exactly the reverse. The reader, so tutored, pronounces an interpretive conundrum: when it comes to your future as Jay Gatsby, where have you gone, Rudy Miller?

The Professor’s House appears to be a perfect display of Leslie Fiedler’s mythography of male homosocial bonding, one (Tom for Roddy) nestled inside another (Professor for Tom), the first big-brotherly, the second classically pederastic, both subject to idealizations of memory and both seemingly as pure as the water of mesa and lake. Yet it is the Professor himself who bewails the lost “magnificence” of the discourse of sin. His real-life fairy godmother is a devout German Catholic by the name of Augusta (Augustine, in Marian female form), who not only teaches him doctrine but rescues him from the ultimate trespass against God’s gift of human life. The Professor’s name is even “Godfrey St. Peter,” an oxymoronic gesture simultaneously to a will to atheism (God-free; get it?) and to the persistence of missionary practice in the contemporary Americas—less Pauline in its sexual ethos yet devoutly responsible to others, in the manner of his Quebecois ancestors. Another interpretive dilemma: what does the Professor’s understanding of the seven deadly sins (three of which remain “perpetually enthralling”) have to do with the events of the novel?

Third, it could be merely a curious conceit of Hemingway—that narrator Jake Barnes, our quintessential love-struck yet impotent stoic—is a lapsed Catholic, if it weren’t for many such insinuations. The novel is staged as an anti-capitalist pilgrimage along the historical route of St. James, with Jake ducking into churches for intercessory prayer and encountering earnest pilgrims along the way. The famous bullfights are pagan preservations within the devout festival of San Fermín—where the Parisian Jansenist arithmetic of monetary exchange yields to peasant Marian communions of bread and wine, body and blood. In the denouement, when Brett cougars matador Pedro Romero, she does so in full reliance upon her very special pimp-and-rescue relationship to bewitched yet eyes-wide-open Jake. For Jake, the radiant, always-desired yet ever-desiring Lady Brett is the end-all and be-all despite her endless repudiation by critics—who take her either as The Whore of misogynistic projection or simply a ruthless nymphomaniac. The reader puzzles meanwhile: what does Catholicism have to do with that?

Cohort biography alerts us to three-way convergence. “Papa” Hemingway, that icon of hearty secular manhood, had the most anti-Catholic and puritanically Calvinist upbringing unto adulthood imaginable in post-Victorian America, yet he periodically claimed conversion to the Roman Church, remarrying into it as well. By the time Cather wrote The Professor’s House, she had in fact converted from her Southern Baptist raising to a lesbian-hospitable Episcopalian Catholicism and would soon write her own extraordinary mission tale, Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927). Fitzgerald of course was raised in an observant household and educated in Jesuit prep school, then fiercely mentored through adulthood by a flamboyant and erudite priest, of the order seen in Cather’s and Hemingway’s novels, too. All three thought in doctrinal terms and practiced vernacular—not always catechetical!—devotions.

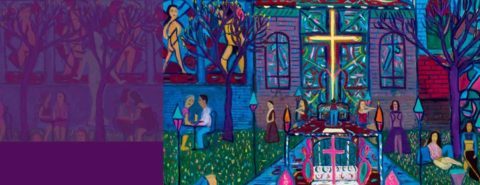

In 1925, Protestant America feared for the future of America as no-longer strictly Protestant, not quite white or Anglo-Saxon. Its anxiety was manifested in closing economic and marital ranks against Catholics and, especially, Jews—the very nativism that Hemingway, Cather, and Fitzgerald dramatized and, to varying extents, ironized, in storied couplings. But there is another dimension, arguably a larger dimension, to the story of how mid-20s ethnocentrism played out in our iconic novels—which has long escaped us, in part because the Lit-Crit establishment is still loath to give American Catholicism its transfigurative due. What I wonder is whether the Catholic signs and personae dogging all three novels are matters not only of class and race but also of sex, violence, and sanctity—theologically comprehended whilst vernacularly (re)imagined. For are not all three novels, which have been disdained since the 1970s as “melodramas of beset sexuality,” even better characterized as martyr tales of forbidden love, and thereby mystery plays in something akin to an American Counter-Reformation, gorgeous unto themselves and possibly tempting even Jews? Afterall, as the Hollywood moguls have liked to quip ever since the mid-twenties, “we are Jews selling Catholic stories to Protestants.”

Featured image from the cover of Transgression and Redemption in American Fiction by Thomas J. Ferraro.

July 6, 2021

How well do you know Louis Armstrong? [Quiz]

With a career that spanned five decades and different eras in jazz, Louis Armstrong is perhaps one of the best-known jazz musicians. This year’s 6 July marks the 50th anniversary of his death and to celebrate this influential entertainer, we have put together a short quiz about his life.

Test your knowledge below! All answers can be found in Armstrong’s entry on Grove Music Online, which is free to access until 31 July 2021.

Feature image: Louis Armstrong, 1953. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers