Oxford University Press's Blog, page 104

June 28, 2021

Innovation in libraries: the University of Johannesburg Library

Innovation has been a buzzword in all industries amidst this “new normal” and libraries are having to change their approach rapidly in these challenging times. OUP representatives set out to find examples of truly innovative libraries from across the world and the first one in our series is focused on the University of Johannesburg (UJ) Library, in Johannesburg, South Africa.

It was most certainly a year of challenge and change for everyone within the UJ Library, similarly to the rest of the world, but amidst this the UJ Library has launched many new initiatives—from their very own bot to a new free mobile application. We spoke to library representatives from the university, including their Marketing & Special Projects representative Ms Reneka Panday, to get an idea of some of the interesting and unique projects that their library is working on.

Tell us about an innovation in your library?BOTsa, the UJ Library chatbot, was officially launched on 29 January 2020. BOTsa means “ask” in Setswana. The chatbot was developed to answer basic library-related questions and user queries 24/7 and refer enquiries that could not be answered by the bot to the library staff to respond to via email.

The library chatbot is an open source-based chatbot powered by Snatchbot, a bot-building platform. It was at the beginning of 2019 when the library thought of putting in place an automated customer service mechanism to alleviate the pressure presented to staff by the huge number of students that flocked into the library’s information desk with similar library queries, particularly at the beginning of the academic year. This became hugely successful during the lockdowns in 2020 as the university learnt to move to a virtual classroom option.

What is your library doing differently during the pandemic to enable people to access library resources?As a result of COVID-19 and a national lockdown in South Africa, the UJ made an unprecedented decision that has necessitated a shift to online teaching and learning. UJ Library launched its new e-library app with the goal of providing students with the UJ Library in their pocket.

The library has seen the digital transition of our students and institution, and we have seen and identified the challenges that digital has brought to the institution.

The app provides hassle-free access to the university’s books, guides, information, bots, and online training, among other functionalities.

If budget was not an issue, what innovative feature would you add to your library?UJ Library is on a quest to be the largest e-Library in Africa and would like to experiment with augmented reality, which is a hot topic in the tech world. “People are curious about its deployment in various domains, from medicine to gaming. So why not implement it in libraries too and combine digital with reality?” says Ms Alrina de Bruyn, Director of Marketing and Events, UJ Library.

Some of the areas that UJ Library would experiment with if budget was not a constraint are:

Virtual reality events—like visit the library from anywhere in the worldExperience your favourite book through virtual realityVirtual reality teaching and library training experiencesHigh-end, state-of-the-art online international conference platforms.Additionally, UJ Library is already looking at blockchain technology, which we are hoping to use to build an enhanced metadata system for libraries to keep track of digital-first sale rights and ownership, connect networks of libraries and universities, or even to support community-based borrowing and skill sharing programmes.

OUP wishes UJ Library the best in their quest for becoming the largest e-resources library in Africa!

Feature image by Sergey Zolkin

Missing the forest for the trees: interpreting the composer’s message

Several years ago, I decided to make the switch to drinking tea in place of other beverages. I treated myself to “top shelf” teas and stored them where the previously small collection had been housed—literally on the top shelf. Not being very tall, every time I wanted a cup of tea I had to climb on the kitchen counter to reach my new-found friends. I did this for a couple of years until I finally stepped back, looked at the overall situation instead of each tin of tea, and decided to simply move them down a shelf! It can be this way with music scores too. We can get so bogged down with mysterious notation that we miss the point of the score: the composer’s message. Obsession over details—why did the composer use newly available extra keys in one piece but not another? Why did the composer use particular articulation in this spot but fail to maintain consistency later? What does this notation mean?—can become the ends rather than the means to the ends.

For instance, in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in G Major, Op. 14, No. 2, I, ms. 43, Beethoven clearly omits f-sharpᶟ, creating a different contour of line in the exposition compared to the recapitulation at ms. 170. This was a common practice when dealing with the five-octave fortepiano of the time. Yet, he had already used f-sharpᶟ in Op. 14, No. 1, and Czerny tells us that Beethoven’s piano at that time contained the notes. So why not use it in Op. 14, No. 2?

There are plausible “forest” explanations. From a practicality standpoint, Beethoven knew that what he wrote must sell—we oftentimes forget that even Beethoven struggled to make a living at his art! Only some of his writing employed notes (or other elements) that would not work on instruments available to the general public. So, although Beethoven was acutely aware of available instruments and their qualities (not just those he owned) and composed to the outer limits in terms of range, dynamics, and other capabilities, he also sometimes took a more conservative approach. Creatively, perhaps he was saving an ascending gesture for the recapitulation at ms. 170. Whether his choice was practicality or inspiration, we will never know. I would like to think it was a little of both.

Or, we can wrack our brains trying to understand why Mozart changed articulation ever so slightly during the retelling of the motive at mm. 37-38 to mm. 41-42 and later, in the recapitulation, at mm. 131-132 to mm. 135-136 in Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 309:

Mozart, Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 309, I, mm. 37-38.

Mozart, Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 309, I, mm. 37-38. Mozart, Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 309, I, mm. 41-42.

Mozart, Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 309, I, mm. 41-42.A “forest” explanation arises when we look through the eighteenth-century notational practice lens. Longer notes were not just longer, they had the capacity to be more expressive. Perhaps Mozart was leaving us a clear indication that on the repeat of the motive we must do something different with it: longer, louder, caress the second note, more…

Even more perplexing (so much so that it has resulted in several scholarly articles) is the mysterious rhythmic notation at ms. 5 in the third movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A-flat major, Op. 110:

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, Op. 110, iii, ms. 5.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, Op. 110, iii, ms. 5.To the modern notation reader this measure makes no sense. What is up with tied notes that also contain a fingering change? Logistically, if Beethoven had meant an 8th note, he never would have taken the time to tediously write two 16th notes with a tie. The comical reminiscence of Seyfried trying to serve as page turner for Beethoven when many pages were almost blank save a few “Egyptian hieroglyphs… since, as was often the case, he had not had time to put it all down on paper,” makes it quite clear that time and efficiency of notation was of the essence. And, Beethoven simply wouldn’t have instructed a fingering change on a tied note. So, it must have meant something.

Historically, eighteenth-century notational practices were still developing, and this may have been as close as he could get. Notational practice of the day tells us that portato was as close to legato as one could get and that notes under a slur are a natural decrescendo:

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, Op. 110, iii, ms. 5.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, Op. 110, iii, ms. 5.Musically, Beethoven was known for his exquisite legato. This may have simply been the best way for Beethoven to relay the message to make the repeated notes as legato as possible but still articulated.

In On the Proper Performance of all Beethoven’s Works (1970), Carl Czerny (Beethoven’s student and protégé) provides a first-person detailed explanation for executing this most expressive figure:

“It is important that the second note of each tied pair be struck much more weakly than the first. Beethoven’s original fingering ‘caresses’ the second note almost by itself. If this instruction is disregarded, however, the passage will not sound like a vocal swell but like a piano tuner at work.”

So here we are, having examined a fair number of trees. If we are looking for consistency in the details, we will be sorely disappointed. The larger question, the forest question, is “What musical message is the composer describing and how can I convey it in my playing?” How can we use the trees to see the forest? Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn knew exactly what they were doing with the notational language and instruments available (the trees) and were inspired to use those tools to create beauty beyond imagining (the forest). With each piece I encounter, my role is to examine the score, study any pertinent information available, grapple with what I think the composer is telling me, and then ask myself how I may bring that message to light on my instrument. If I strive to do this, I believe I am pleasing the composer while creating my own art… my own forest.

Feature image: Forest by Steven Kamenar. Public domain via Unsplash .

June 27, 2021

The mermaid in the fishbowl: the rise of optical illusions and magical effects

The nineteenth century saw the publication of several books explaining how magical effects and spectral appearances could be performed using the science of optics. It started in 1831, when Sir David Brewster (famed for his discovery of Brewster polarization and inventing the kaleidoscope) published Letters on Natural Magic. In this book, Brewster showed how to produce images of ghosts using partially silvered mirrors and by using a magic lantern to project images onto screens or onto clouds of vapor.

Brewster’s work inspired generations of stage magicians including Henry Dircks and John Henry Pepper, who eventually patented what came to be called the “Pepper’s Ghost” illusion. Pepper’s Ghost, impressive as it was, barely scratched the surface of what was possible using optical engineering. It’s a little surprising that more sophisticated optical tricks did not appear until the twentieth century, considering that the rules of imaging had been derived well over two hundred years earlier. But in 1909 something new and impressive burst forth in its fully formed glory. Antoine Francois Sallé, an engineer living in Paris, was granted a United States patent on a “Means for Producing Theatrical Effects” (US 922,722).

Pepper’s Ghost, via Wikimedia CommonsSallé’s holographic invention

Pepper’s Ghost, via Wikimedia CommonsSallé’s holographic inventionSallé’s invention used the Newtonian rules of imaging, which hold both for lenses and for curved mirrors. Under the correct circumstances, one can create a “real” image (through which light rays pass, as opposed to a “virtual” image, which light rays do not pass through; if you place a screen where a real image is located, it will show up on the screen—a virtual image will not) that is the same size as the object, or magnified, or reduced, depending upon the relative positions of the lens or mirror, the object, and the focal length of the optic. The image will, however, be upside-down, but this can be corrected with an image inverter.

“an image produced using a curved mirror can look much more convincingly real, and over a larger range of angles, than an image produced by a lens.”

Using mirrors has advantages over using lenses to work this trick. There is no separation of colors as with a simple lens. In addition, a curved mirror can be used to cover a larger angular region, letting the image be viewed farther off-axis than can be seen with a lens, unless a very large and expensive lens is used. The result is that an image produced using a curved mirror can look much more convincingly real, and over a larger range of angles, than an image produced by a lens. With a subject that is brightly illuminated, the result was that a viewer on the other side of the apparatus saw a perfect reduced image of the subject. If the subject was a person, it could walk around and interact with things. Moreover, the image appeared to be three-dimensional, since each eye of the observer saw the image from a slightly different angle that provided a stereoscopic effect. The word wasn’t yet being used in this context, but a later generation would describe such images as holographic—perfect miniature 3D images of a moving person.

Sallé licensed his invention throughout Europe, and it was displayed in a number of places, including the Crystal Palace in London, the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne, Germany, and the 1914 Jubilee Exposition in Norway. It was also exhibited in a limited way in the United States at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City and at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, but the image’s bigger splash in the United States was yet to come.

Tanagra Theater reaches the United StatesIn 1922, the German Edward B. Schreyer bought the North American rights to Sallé’s patent, moved to the United States, and set up the Tanagra Theater Company at 229 West 42nd Street, in the heart of New York’s Theater District.

Schreyer arranged for a Miniature Fashion Show at the 71st regiment Armory, featuring miniaturized models wearing the latest clothes from the Bijou Dress company of Fifth Avenue. Meanwhile, the illusion was also on display at Coney Island, New York. A behind-the-scenes description (which wasn’t quite accurate) of how it worked was published in Huge Gernsbach’s popular technology magazine Science and Invention.

At about the same time, a production of Karel Čapek’s science fiction play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) was staged in Berlin and Vienna with sets designed by Frederick Keisler, who had seen the effect at the Werkbund Exhibition eight years earlier and incorporated it into the design for the show. Sallé’s effect, now called Tanagra Theater (because the miniature images resembled the tiny figurines that had been unearthed in Tanagra in Greece), had finally made the big time.

The wide use of the Tanagra Theater illusion for advertising and for displays in front of small groups of people is due to the technical limitations of the illusion. Although it provides a perfect miniature illusion, this can only be viewed over a small range of angles, which are limited by the size of the mirror. If you can’t see the mirror, then you can’t see the image.

Tanagra Theater is inherently made for small, close-packed audiences. You can have a situation where you limit the viewing time of your audience and keep moving them through so that everyone gets a view, paying for a necessarily time-limited seat. Or you can use it for advertising, luring viewers in with the promise of seeing something interesting, but which repeats the same things after a short period so that you get high turnover. Tanagra Theater was limited to short ads or to peep show experiences. Kiesler’s use of it in a stage show has to be seen as a stunt, since most of the audience would have been unable to see the miniature image at all.

Peep shows and nude exhibitionsPatents at the time only had a twenty-year lifespan. By 1928, Sallé’s original patent had expired and anyone was free to use the invention without having to pay royalties. Not surprisingly, the field opened up, with many people exploiting the liberated technology. Anthony “Tony” Sarg was already famous as a puppeteer, children’s book artist, and producer of unusual artworks. He is credited with reviving interest in puppets and marionettes. His huge inflatable sculptures were a hit at his Cape Cod studio, and he eventually filled them with helium, effectively creating the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade. Possibly because of his love of puppetry, he experimented with the Tanagra Theater. He installed a Tanagra Theater in the display window at Filene’s Department store in downtown Boston. Like Schreyer’s Tanagra Theater, it was used for miniature fashion shows.

“The Car in the Clouds [was] an advertisement for the Ford Motor company that featured a miniature woman in a miniature latest-model Ford car that appeared to be flying over a landscape”

Later he created The Car in the Clouds, an advertisement for the Ford Motor company that featured a miniature woman in a miniature latest-model Ford car that appeared to be flying over a landscape. There was a microphone hidden in the steering wheel that connected to speakers outside, so the woman could hear questions from viewers and reply. The Car in the Clouds showed up at the Ford pavilion at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, the 1937 Great Lakes Expo in Cleveland, and at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City (where there was a long-running automobile display).

Image of The Car in the Clouds illusion from The Coast Star, 8 May 1936

Image of The Car in the Clouds illusion from The Coast Star, 8 May 1936Others discovered the extremely powerful draw of sex and started exhibiting miniature nude women using the Tanagra apparatus. In 1931, the 365 Club in San Francisco (later Bimbo’s 365 Club) began showing Dolphina, the mermaid at their bar. Dolphina didn’t have a fish tail, but she was naked. Being reduced to fantasy size and clearly untouchable probably helped keep the show from being shut down, but this was the golden age of burlesque and the Depression, and public mores had loosened somewhat—Sally Rand’s Bubble Dance and Fan Dance were the hit of the 1933 Exposition. Dolphina still appears at Bimbo’s today.

Naturally, there were imitators. Billy Rose’s Casino de Paree in New York featured its own nude mermaid. When that nightclub shut down after a very short life, other nightclubs in New York started featuring them. There appears to have been a Fishbowl Mermaid at the 1933 Exposition, as well. The 1937 Great Lakes Exposition featured a “Little French Nudist Colony” that lived up to its name, literally.

A traveling show called the “French Follies” or the “Parisian Spices” toured the United States. As an enticement, they featured a Mermaid in a Bowl in the theater lobby. This might not always have been a nude mermaid, but the one displayed in Washington, D.C. in 1935 apparently was. The Daughters of the American Revolution took offence and protested to the theater owners. They responded by putting a “strawberry colored” bathing suit on the mermaid.

The Fishbowl MermaidA Miniature Mermaid display, compact and transportable enough to be displayed in a theater lobby, sounds like something that wouldn’t work with the full Tanagra Theater. It might work with Bostock’s negative lens, but it’s likely that it was around this time a third major method of producing the illusion debuted. This is likely the same one that later ended up being used by traveling carnivals. It’s very simple and uses very inexpensive and easy-to-obtain components, rather than expensive and hard-to-fabricate curved mirrors or large lenses.

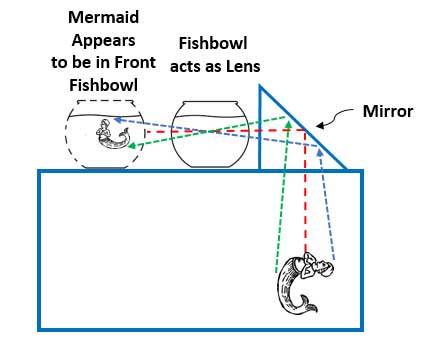

The fishbowl in which the mermaid appears is also the optical element responsible for the illusion (see diagram below). The bowl is filled with water. Better still, it is filled with clear mineral oil, which won’t let algae grow in it and won’t evaporate. This fluid-filled spherical bowl acts like a lens. It’s not a perfect lens, because it doesn’t have constant power across its face and has lots of chromatic aberration. But that’s okay, because it does make the mermaid appear to be truly underwater. The bowl sits atop a large rectangular box. There’s a large mirror behind the bowl, angled downward at 45 degrees, directing up light rays from inside the box.

Author’s diagram of the Mermaid in the Fishbowl illusion

Author’s diagram of the Mermaid in the Fishbowl illusionInside the box is a woman dressed as a mermaid, and maybe some undersea props. Her image is upside-down, but that’s not a big deal—she’s lying down and can lie with her feet in either direction, but appears to be upright. Her image is actually projected forward beyond the fishbowl, but most customers won’t notice—her image is a line with the fishbowl, so she appears to be in it. If you want to make the illusion perfect, put a second fishbowl in front of the first one, into which her image is projected (amazingly, this innovation isn’t documented until it showed up in a 1978 patent).

“The Fishbowl Mermaid became a fixture of traveling carnivals and freak shows.”

The proliferation of nude illusions bothered one entrepreneur who had worked at Billy Rose’ nightclub and had seen the nudes in 1933. Mike Todd felt that this use limited the potential audience. Children were the ideal targets for this technology, and he proposed using Santa Claus as the miniaturized subject (wasn’t he, according to Clement Clark Moore, “a right tiny old elf” with “eight tiny reindeer”? How else could he slip down chimneys?). This individual re-invented Bostock’s device, using war-surplus lenses bought for pennies on the dollar. Like the woman in The Car in the Clouds advert, he could speak to the audience using a telephone on a stand at his side. It was granted a patent and licensed to major department stores at Christmas in the big cities and made a small fortune for its creator. He was later to become a film producer and the driving force behind the Todd-AO widescreen process.

Interest in the illusion fell off after the second World War. The novelty was gone. The Girl in the Fishbowl still showed up at Bimbo’s and a few other nightclubs as an eccentricity. The Fishbowl Mermaid became a fixture of traveling carnivals and freak shows. Carnival operators could learn how to build one from the plans in “Brill’s Bible”, the mail-order guide for carnies.

Ultimately, the Tanagra Theater illusion suffered from its inability to play to a large enough audience to justify its expense. In many ways, Tanagra Theater resembles a much later optical effect—3D holographic movies. Such movies exist and are restricted to small sizes (being limited by the size of the holographic film) and small audience size, and limited range. Holographic movies, like Tanagra Theater, produce amazing 3D images, but they are expensive to make, have limited interest, and can only play to a small “house”. Both technologies, unable to pay their own way, have been reduced to the status of curiosities.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons

June 26, 2021

Saint Napoleon? How Napoleon used religion to bolster his power

Though not a believer himself, Napoleon was well aware that religion was a vital tool for any ruler, especially when many of his subjects were believers. As he said to his secretary, Emanuel Las Cases, on St Helena at the end of his life: “from the moment that I had power, I hastened to re-establish religion. I used it as foundation and root. It became the support of good morals, of true principles, of good manners.” The Catholic religion had been suppressed in France during the French Revolution and was still anathema to Republicans but, during his time as First Consul three years before becoming emperor, Napoleon reinstated it. He signed a Concordat with Pope Pius VII on 15 June 1801 which allowed Sunday worship again and permitted clergy who had gone into exile to return to France. However, the church was to be subordinate to the state, confiscated church property was not returned, feast days and processions were cut to a minimum, only a handful of teaching and nursing orders were allowed to exist, and Judaism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism were to have equal status with Catholicism. Napoleon also retained the right to appoint bishops and oversee church finances. On the first Easter Sunday after the signing of the Concordat, 18 April 1802, he processed to Notre-Dame to mass with trumpets blaring, accompanied by the Papal Nuncio Cardinal Caprara.

Although he had been elected emperor in a plebiscite in 1804, Napoleon organised a coronation ceremony in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris to demonstrate that he was not just the people’s choice but God’s. He brought the pope to Paris to preside over it and to anoint him and his consort. In 1806 he issued the Imperial Catechism as the basis for religious instruction in French schools. Lesson VII of this document states of Napoleon that God “has established him as our Sovereign and has made him the minister of His power and image on earth. To honour and serve our emperor is then to honour and to serve God Himself.” A divine mandate could not be expressed more clearly.

Napoleon wanted a patron saint to enable him to celebrate his name day, so the Cardinal Caprara produced Neopolis, a third-century Roman martyr who had resisted Emperor Maximianus (ca. 250-310 CE). This saint, whose very existence is doubtful, was then declared to be St Napoleon. He was very suitable for the emperor’s purposes, for he could be presented as the patron saint of warriors and as someone who was prepared to die for his people. Napoleon then created the feast of St Napoleon as a public holiday in 1806, decreeing that it should be celebrated on 15 August, thereby piggybacking on the popular Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. This date happened also to be Napoleon’s birthday, so he was able to link homage to God with homage to himself.

Pope Pius VII was not just the head of the church, he was also a temporal ruler who stood in the way of Napoleon’s conquest of Italy. In January 1808, French forces occupied Rome and took the pope prisoner, bringing him to Savona on the French Riviera, and later to Fontainebleau where he remained Napoleon’s prisoner for five years. Though the Pope excommunicated Napoleon in September 1809 and annulled the Concordat, Napoleon carried on using the church to legitimize his rule and to celebrate important occasions such as military victories.

Because he wanted a son, Napoleon divorced his first wife Joséphine in 1810 and chose the Habsburg princess Marie Louise as his second wife. He ordered all twenty-seven French cardinals to attend his wedding in the Louvre but thirteen of them staged a revolt and did not attend. Napoleon was still married to Joséphine in their eyes and they were not prepared to endorse a ceremony which was against the laws of the church nor to lend credence to the man who had imprisoned the pope. Napoleon punished them by removing them from their bishoprics, forbidding them to appear as cardinals, and depriving them of their pensions. Ultimately, however, Napoleon failed in his attempt to bend the church to his will. In 1814 the pope returned to Rome from his French exile, his journey resembling a triumphal procession. In the same year Napoleon abdicated and died in exile on St Helena in 1821, while Pius VII continued to hold office until his death in 1823.

Featured image by Jacques-Louis David via Wikimedia Commons

June 25, 2021

Exploring the choral music of Rebecca Clarke

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) is most commonly known as a violist and composer, in particular for her famous Viola Sonata (1919), which has remained one of the most significant in the instrument’s repertoire since its composition. Her Shorter Pieces for viola and piano, as well as a number of solo songs, have gained increasing recognition since the turn of the millennium, as more of her music has begun to be published and researched.

Clarke’s choral music remains less well-known. She was, however, composing choral music from her earliest studies at the Royal College of Music, as Charles Stanford’s only female composition student, right up to 1944, before she stopped composing almost completely for the last 35 years of her life. She worked alongside some of the most influential English choral composers of her day, singing in a choir at the Royal College under the direction of Ralph Vaughan Williams, alongside George Butterworth and Gustav Holst, and with Hubert Parry even sponsoring some of her tuition. Her choral music weaves together influences from many of these composers, while maintaining her own characteristic style.

Clarke’s earliest choral works draw influences from old English forms such as the madrigal, glee, and part-song, which were undergoing a revival during the early twentieth century, as part of the “British musical renaissance.” Pieces such as Lover’s Dirge and When Cats Run Home and Light is Come, which set texts by Shakespeare and Tennyson, are inspired by the old English ‘madrigal’ form, while Now Fie on Love, her earliest work, is described by Christopher Johnson as a “rapid-fire glee.”

During the 1910s and 20s, Clarke began to develop a more distinctive style in her choral music. Works such as My Spirit Like a Charmed Bark Doth Float and Music When Soft Voices Die are in some ways reminiscent of some of Parry’s Songs of Farewell, in their ebb and flow of expressive textures and dramatic interpretation of the text, but are characterised by Clarke’s signature chromaticism and harmonic shifts. Philomela sets another beautifully expressive text, telling the Greek myth of Philomela from the perspective of her sister Procme, and conveys the narrative through deft changes in texture and harmony.

When she came to write her first sacred setting, He that Dwelleth in the Secret Place of the Most High, Clarke was much more comfortable in the medium, writing in her diary how exciting she was finding this particular setting. Powerful climaxes on passages such as “a thousand shall fall at thy side” convey real drama, giving way to lighter, more peaceful harmonies on “There shall no evil befall thee.”

During the 1920s, Clarke’s choral composing seems to have given way to her increasingly demanding performing career. Clarke was one of the most prominent English violists of her day, performing with musicians such as Pablo Casals, Jacques Thibaud, Artur Rubinstein, and Myra Hess, and had been among the first women to be (controversially) admitted to Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1913. Towards to end of the 1920s, however, she returned briefly to the old English forms that had sparked her interest in choral composing. She arranged a few of her solo vocal works for choir—Weep you no more, sad fountains, inspired by Renaissance lutenist and composer, John Dowland, and the lilting Come, oh come, my life’s delight—as well as writing a new arrangement of the fifteenth-century English carol, There is no rose.

Clarke’s final two choral compositions, Ave Maria (1937) and Chorus from Shelley’s Hellas (1943), are both scored for upper voices. Marin Ruth Tollefson Jacobson suggests that her decision to focus purely on women’s voices may have reflected her growing interest in supporting women musicians and composers in later life. While earlier in her career Clarke was involved in the newly founded Society of Women Musicians (1911) and was an advocate for women musicians to receive equal opportunities and rights as their male counterparts, she was often less outspoken than some of her contemporaries, such as Ethyl Smyth, and was adamant that composers be judged solely on merit above all else. In later life, however, as she reflected on her career and her decision to use the male alias “Anthony Trent” for some of her earlier compositions, Clarke seems to have acknowledged some of the barriers she faced due to her gender, remarking wryly how on occasions critics seemed to prefer the pieces by “Anthony Trent” to the pieces by Rebecca Clarke.

Regardless of the motivation behind her choice of scoring, these final pieces seem a fitting culmination of her compositional style, with the mix of inspiration drawn from Renaissance music alongside impressionistic, chromatic harmonies, and an incredible sensitivity to text.

June 24, 2021

Extraordinary times: revisiting the familiar through the novels of Marilynne Robinson

Last week, after more than a year of living in pandemic lock-down, my husband, my son, and I drove from our home outside Boston to the outer tip of Cape Cod, where we parked in a near empty lot and walked down a steep hill through the dunes to the ocean. “It’s still here,” I said aloud, trying to breathe in the sweeping expanse of the curved shore, the June light illuminating the water, the sound of waves and the sweep of terns. Like the trip we took as a young family to watch the sunset at Race Point Beach just days after 9/11, this encounter with the sublime felt like a blessing, a visceral recollection of the way that beauty opens us up to something larger than ourselves.

When I read Marilynne Robinson’s first novel, Housekeeping, in graduate school, its lyrical beauty transfixed me in a similar way. Over the years, I have taught that book to undergraduates (some mesmerized, some confused), recited favorite lines aloud, and written out passages in notes to friends. At my wedding, perched above the rocky shore of Maine, my sister read from the novel:

Having a sister or a friend is like sitting at night in a lighted house. Those outside can watch you if they want, but you need not see them. You simply say, “Here are the perimeters of our attention. If you prowl around under the windows till the crickets go silent, we will pull the shades. If you wish us to suffer your envious curiosity, you must permit us not to notice it.” Anyone with one solid human bond is that smug, and it is the smugness as much as the comfort and safety that lonely people covet and admire. (154)

Robinson scholars and fans share my passion for the grace of her writing and the way that she transforms the ordinary world into something extraordinary. The power of her prose and the framework of religious faith distinguish her fiction from much contemporary writing, offering the solace of beauty and the possibility of belief.

Often, that beauty emerges out of the awareness of loss. In Gilead, Robinson’s second novel, Ames’s journal offers a series of achingly beautiful images of a world detailed by a narrator whose awareness of his impending death intensifies his every perception. Seeing his wife and child play outside, he observes,

I saw a bubble float past my window, fat and wobbly and ripening toward that dragonfly blue they turn just before they burst. So I looked down at the yard and there you were, you and your mother, blowing bubbles at the cat, such a barrage of them that the poor beast was beside herself…. Some of the bubbles drifted up through the branches, even above the trees. You two were too intent on the cat to see the celestial consequences of your worldly endeavors. They were very lovely. Your mother is wearing her blue dress and you are wearing your red shirt and you were kneeling on the ground together with Soapy between and the effulgence of bubbles rising, and so much laughter. Ah, this life, this world. (9)

The intensity of Ames’s vision emerges as compensation for his inability to participate in this quotidian moment; Robinson’s protagonist observes a scene made all the lovelier by virtue of his anticipation of its loss.

Even for those of us who have not gotten sick or lost a loved one to COVID-19, this period of crisis has generated an awareness of vulnerability that pushes us to appreciate all that we have taken for granted. Seeing the ocean, hugging a family member, even lingering over fresh produce in the supermarket, assumes an intensity usually reserved for doing something for the first time. The prospect of loss encourages us, like Robinson’s narrator, to re-experience the familiar, perceiving it anew.

Her novels, however, also explore the way that the threat of mortality and the reverberations of trauma disrupt the comforts of the everyday. Scarred by illness, addiction, and grief, Robinson’s characters inhabit a world of transcendent beauty suffused with the terrifying threat of loss. As consciousness haunts her protagonists, returning them again and again to the inevitability of loss, the everyday world that might cushion them only throws into relief their panic. In contrast to the luminous images of textured presence that we often associate with her portrayal of the ordinary, Robinson’s characters also huddle, hunched and anxious, in an uncomfortable everyday. Stiffly perched on the edge of uncushioned furniture or propped awkwardly in the midst of someone else’s conversation, they inhabit the margins of a lived experience they are often forced to observe self-consciously and vigilantly. The novels stage, again and again, scenes in which their protagonists look down at the unfolding activity of daily life from a window or a podium, summon its textures only through memory and imagination, retreat from its touch into dim and isolated spaces that strain to echo the lived rhythms of home.

As it defamiliarizes the familiar world, the inexplicability of loss pushes us into a state of hyperawareness that transforms the way we inhabit the everyday. For many of us lucky enough not to be on the front lines of the pandemic, this endless period of lockdown has unfolded with a sameness edged in horror. Locked into circumscribed spaces, we have been isolated but not necessarily protected; as days blend into one another and weeks pass, we labor to make ourselves at home in our most familiar spaces. The abstractions of daily death tolls, combined with the invisible, omnipresent threat of the virus, have forced us into new routines that might return us to the realm of safety. New habits—wiping groceries, quarantining packages, washing hands—seemed designed not only to keep the virus at bay physically but psychically, to restore the illusion of security and the grounding of the familiar destroyed by the horrors of the pandemic.

In Housekeeping, Ruth’s grandmother responds to the sudden death of her husband by desperately reenacting the domestic routines that represent the ordinary rhythms of the taken-for-granted, everyday world:

And she whited shoes and braided hair and turned back bedclothes as if re-enacting the commonplace would make it merely commonplace again, or as if she could find the chink, the flaw, in her serenely orderly and ordinary life, or discover at least some intimation that her three girls would disappear as absolutely as their father had done. So when she seemed distracted or absent-minded, it was in fact, I think, that she was aware of too many things, having no principle for selecting the more from the less important, and that her awareness could never be diminished, since it was among the things she had thought of as familiar that this disaster had taken shape. (25)

The unassimilable disaster of the pandemic has settled uneasily into our familiar lives, piercing the protective cushion of routine and rendering the ordinary uncomfortable. As we take off our masks and begin to venture out into a larger world, we wait to see what it means to live with a newfound awareness of our own vulnerability. Although a return to the everyday as we once knew it seems impossible, the aching beauty of lived experience, thrown into relief by all that we can no longer take for granted, calls us back into the world.

Feature image by Caleb George on Unsplash

June 23, 2021

Now in the field with a fieldfare

Last week, I wrote about the troublesome origin of heifer. The oldest recorded form of heifer is HEAHFORE. In Old English, o and a alternated rather freely before r, so that the last element of heahfore might be –fore or –fare. My previous post dealt mainly with the enigmatic element heah-, and I promised to return to the equally enigmatic- fore. I even wrote that perhaps the etymology of the bird name fieldfare would throw additional light on heifer. Birds often follow herds of cattle for sustenance, so that my idea is, on the face of it, not unreasonable. Just for those who may be not quite sure what bird a fieldfare is, let me explain: it is a thrush (and see the header).

The earliest attestations of the word (1100) pose some problems. Moreover, since all kinds of forms of fieldfare appear in modern dialects, we cannot know which one is “correct,” that is, initial, original. Chaucer pronounced feldefare in four syllables. Regardless of such complications, the bird’s name seems to be in some way connected with field. I say cautiously “seems to be,” because feolo– also occurred as the first element of the compound. Etymologists who relied on feolo– offered a derivation that has nothing to do with field-. Yet Old English feldefare looks like the best form to work with, and we’ll stay with it. Most modern scholars understand the word as “field-farer.” This interpretation poses the natural question whether fieldfares are known for a specific way of crossing or traversing fields. They are not. Despite the support of some of the most authoritative dictionaries, –fare in this word has probably nothing to do with “faring.”

Two bird names may be relevant for chasing the fieldfare: one is Old English scealfor “diver, cormorant,” the other Dutch ooievaar “stork.” That old word for “stork” has not continued into Present-day English. Yet it has a Modern Dutch cognate, namely schollevaar. I have highlighted –for and –vaar, because it is my hope that they will tell us something about –fare in fieldfare. However, my optimism is restrained, because, as I have written more than once, an etymologically obscure word cannot furnish a reliable clue to another equally obscure one. Knowing all that, I still hope that it may be better for the dubious group to stay together than die in isolation.

A stork in its natural habitat. (Image by Leszek Leszczynski via Flickr,

A stork in its natural habitat. (Image by Leszek Leszczynski via Flickr, Ooievaar has been discussed many times. It has a close look-alike in German, namely, Adebar “stork.” At first sight, ade– does not correspond to ooie– (in fact, they do), but the second elements match well. Our great teacher Jacob Grimm thought that Adebar goes back to some form like Gothic uddja–baira or addja-baira “egg carrier” (ai has the value of short e here), with reference to the widespread belief that storks bring luck and to the custom of telling children that babies are brought by storks. He compared his uddja– with uterus (-baira was of course supposed to be related to the verb bear); the Germanic word auda– “luck” also comes to mind. Grimm’s explanation of Adebar dominated German and Dutch dictionaries for ninety years. Friedrich Kluge, the author of the greatest etymological dictionary of German, first shared this interpretation but later made rather unsuccessful attempts to modify it.

There is little doubt that even a thousand years ago, the German-Dutch (and we should add, Frisian) name of the stork was as impenetrable to speakers as it is to us (which testifies to the word’s antiquity; freshly minted words are more often transparent). Last week, I said the same about English heifer. Such opaque words often fall victim to folk etymology (compare the trite example of asparagus becoming sparrow grass) or keep changing in unpredictable directions. I’ll pass by several fanciful (even bizarre) old conjectures about the history of this word and leave out a few dubious interpretations of ooie– ~ Ader-, because the first component seems to have been explained correctly (see below) and because here I am interested only in the possible congeners of –fare in fieldfare.

The best image of an elver we could find. (Image by Peter Harrison via Flickr, )

The best image of an elver we could find. (Image by Peter Harrison via Flickr, )In 1938, Willy Krogmann, a serious etymologist, disposed of the luck idea and explained that the root of ooievaar ~ Adebar meant “wetland,” but he failed to discover the origin of –vaar ~ -bar. He conceded that, whatever the meaning of that element might be, it was later reinterpreted as –bar “carrier.” No such process can, however, be reconstructed for the Dutch word. Before returning to my idea that –fore ~ -fare was some sort of suffix, occasinally used in animal names, I would like to mention the little-known English noun elver “young eel” (first recorded in 1640), a variant of eelfare “brood of young eels.”

This suffix –fore, I believe, meant “in the presence of, in front of” and can be seen in Old English inneforan ~ innefaran “intestines, entrails.” If such a suffix existed, the origin of all the words cited above will fall into place. A heifer will stay in its enclosure (see the meaning of hei– in the previous post). The stork will be confined to the wetlands, leave babies alone, and hunt for frogs. The first element of Old English scealfor ~ Dutch schollevar will remain obscure, but it may refer to some body of water or the creature’s behavior, because the bird’s other name is “diver,” and its other Dutch name is dompel-aar, from dompeln “to dive” (-aar, which later speakers associated with aar ”eagle,” goes back, almost certainly, to the familiar –vaar). Elver hardly ever meant “young eel.” The word’s sense must have been “an eel confined to its brood”; later the sense “brood” superseded the original one. William B. Lockwood, perhaps the greatest modern specialist in the history and origin of bird names, noted that the concept “goer” or “dweller” is alien to the popular ornithological nomenclature. The fieldfare was, consequently, not a field-farer or a field-dweller but a bird whose search for food is restricted to a field, which makes much better sense.

This is a real field-farer! (Image by Jean-François Millet via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

This is a real field-farer! (Image by Jean-François Millet via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)All the words examined today and a week ago must have been coined long before they surfaced in our texts. By the time of their attestation, their original meaning had become as obscure to the speakers as it is to modern etymologists. Nothing could be more natural! Those who spoke about thrushes, storks, sparrows, swallows, and heifers, had no idea why the birds were called this. After all, if we disregard Gothic (recorded in the fourth century) and the ancient Scandinavian runes, Germanic texts do not antecede the eighth century, while the names that interest us may have been coined in the hoariest antiquity.

Here I’ll stop and leave my characters in their enclosures, fields, and ponds. I hoped that the fieldfare might help the heifer, and, quite possibly, it did.

Featured image by TheOtherKev via Pixabay

June 22, 2021

Career development: shaping future-ready academic researchers

Recently I read an excellent article about the experiences of 658 early career Australian STEM researchers with respect to their career experiences, challenges and barriers to ongoing employment in the sector. Researchers from across the country highlighted concerning experiences relating to limited access to training and development (particularly in career management, professional skill building, project management, and leadership), and less than optimal support contexts. The article clearly maps a sector that remains largely impervious to the real plight of researchers who are navigating an incredibly complex space of seeking progress across roles and employment avenues to continue their passion for their research.

As a coach and author on research development, I have been very conscious of the ongoing plight of academics and researchers who are expected to shape and build their capabilities, impact and outcome, but often with little in the way of guidance or support. It isn’t only at the early career level: the shift from being a novice to independent researcher brings with it a new challenge of refining one’s research identity and strategy. Building impact from the research and establishing a visibility and voice about the research niche, its importance and the learnings that can be gleaned from the work undertaken, are increasingly critical elements of the research portfolio. This can be challenging, particularly for those who lack mentorship, sponsorship, or quality supervision.

When I first started mapping the developmental needs of Australian researchers, similar issues emerged. This led to the Group of Eight’s development of The Future Research Leaders Program (FRLP), which was launched in 2009. Operating as a blended learning programme, we offered eight learning modules, with associated workshops delivered in each institution. It wasn’t elegant, but it was enthusiastically embraced by researchers across our institutions. Over 1,000 researchers participated in the programme in the first year. They valued the flexibility and the accessibility of learning when they had capacity to do so. The integration of allied institutional workshops contextualised the learning and offered models and important links to policy, exemplars, and a learning community.

“Institutions that wish to support their researchers need to think deeply about what a researcher needs to know and do to be successful.”

This successful experiment illustrated the hunger that researchers in universities have for learning how to be successful in an efficient and informed manner. I watched with fascination as the UK embraced this issue and built a coordinated response through Vitae and developed their Research Developer Concordat. I visited key groups in the UK to find out more, hoping that we could translate these same principles. Despite the establishment of the Australasian Research Management Society and explorations of research development at various conferences, the formalisation of support for research development remains largely discretionary and dependent on the will of the individual institution. In fact, research development often remains a rather contentious space in this country. Which portfolio does it fit under? It might, for example, fit into the DVC Academic or Research portfolios. In some locations, faculties are expected to step forward. When we established the FRLP we found that researcher development fitted into a range of portfolios. In fact, it doesn’t matter, so long as someone is taking ownership.

In the absence of Vitae and a concordat, universities have developed different approaches to their research capacity building. Some have established capability frameworks and mapped their support activities against those standards. This raises another important set of questions for institutions to consider: what are the core capabilities that we need to promote? Should we be focused on early career? Mid-career? Research Leaders? Generally, institutions are targeting the early career phase, where the research fundamentals need to be consolidated and refined. Being a productive researcher who can write, publish, manage a project, and work with collaborators are basic capabilities. Certainly, support to build these capabilities is an important foundation that should be offered in any institution.

However, the advancement from novice to independent researcher requires ongoing growth in capabilities and insights. The individual needs to confidently navigate their career—particularly if it is based on soft money or needs to be adaptive in responding to opportunities. The capacity to build winning bids for funding or fellowships certainly supports career progression. The transition to leadership needs to be carefully guided to build a larger community of constructive research leaders who mentor and sponsor others. The push for impact and engagement has escalated across all of our nations. This translational focus is a progressive journey that reflects the transition to mid-career and senior roles. Critical threshold skills include self-reflection and feedback seeking. Thus, institutions that wish to support their researchers need to think deeply about what a researcher needs to know and do to be successful. The new Advancing your Research Career: Strategies for Research Leadership programme has been designed to capture the shifts in research expectations and to ensure researchers are supported across these elements—and levels.

“Researchers need access to quality learning opportunities that are fit for purpose, capability-focused, flexible, high quality, and impactful.”

Finding the right people to design and deliver suitable workshops and programmes to encourage critical capabilities can be hard to find in each institution. And it takes time to build these offerings to ensure they are authentic, persuasive, and seen as aligning with the learner’s own lived experience. The development of blended learning approaches that provide a top-quality learning mode with contextualised local support offers the best of both worlds. In 2014, when we first released the Professional Skills for Research Leaders, (Epigeum’s first research career development training programme and the precursor to Advancing your Research Career), we aimed to offer world-class learning, drawing on best practice research development, without each institution having to design each module itself. This platform then supports customised, adaptive, localised sessions where institutions, faculties or institutes can explore these generic capabilities in context. It also encourages systemic capacity building rather than isolated pockets of excellence.

The next few years won’t be easy for our sector. There is pressure on researchers and academics to scale up their impact and reach, and to demonstrate their value. To meet these escalating expectations, they need access to quality learning opportunities that are fit for purpose, capability-focused, flexible, high quality, and impactful. The investment in research development is a major strategic decision by each institution, illustrating that researchers do matter. Online programmes like Advancing your Research Career offer economy of scale and customisable learning platforms that reduce institutional load on responding to this need. They also help each individual to optimise their potential with the right knowledge and insights to make the right career choices.

June 21, 2021

Earth’s wild years: the creative destruction of cosmic encounters

We earthlings enjoy the spectacle of shooting stars: small fragments of asteroids and comets that burn in sudden flashes upon entry in the Earth’s atmosphere. The largest of these fragments pose a limited threat to us as their mid-air blasts can produce local damage to buildings and infrastructures. Larger events are increasingly rarer, but their consequences can be devastating on a global scale. Fortunately, we do not have first-hand experience of such events, but the extinction of the dinosaurs by a collision with a 10-km asteroid about 66 million years ago is etched in our imagination. Planetary scientists are finding immense cosmic collisions were common during Earth’s first billion years. Compared to the most energetic of these early events, the dinosaur-killing collision was a modest firecracker.

At the dawn of the Solar System, about 4.6 billion years ago, collisions were responsible for the growth of the Earth and the formation of the Moon; later, they modulated Earth’s evolution by enriching the chemistry of its atmosphere and oceans. New worlds emerged from the upheaval of cosmic catastrophes, and our planet as we know it today may be the result of random events that occurred billions of years ago. The planet could have followed innumerable other paths, in unpredictable directions; a multitude of possible Earths could have emerged from the clamour of early collisions. And all the while Earth was reshaped by these events, life was taking a toehold on our planet, some 4 to 3.5 billion years ago. Contrary to common sense, cosmic collisions are not all about destruction and death. It appears entirely possible that collisions could have been beneficial to the development of conditions suitable for the formation of first organisms—our distant relatives—on Earth. What do we know about these early cosmic catastrophes?

The research of these distant events faces innumerable challenges. We estimate the Earth was fully formed by 4.5 billion years ago, and yet its surface rocks are much younger. There are only a few scattered localities exposing rocks older than 3 billion years, and the oldest known terrestrial rocks date back about 4 billion years. Scientists—it may seem—are subject to an unfair punishment suitable for Dante’s Inferno: the most accessible planet to study in the Universe, our Earth, has erased its early history. But not all is lost. Clues of ancient collisions can be found elsewhere in the Solar System, pretty much everywhere we look. Scars of collisions are visible in impact craters found on nearly any solid surface in the Solar System, from our Moon to asteroids and other planets. Mars’ barren surface, for instance, is sculpted by countless impact craters, some of which may have hosted ancient lakes. Small pieces of extraterrestrial rocks that serendipitously land on Earth—called meteorites—also record catastrophic collisions that have shuttered their progenitor asteroids at the dawn of the Solar System.

Should we surmise the Earth experienced similar cosmic catastrophes in its wild years? Certainly. Scientists are able to trace the flow of key atoms in a restless Earth to reveal traces of ancient collisions. Among the various elements, there are a few such as gold and platinum that exhibit a strong affinity with iron, and they are aptly known as highly iron-loving elements. So, we can expect that the Earth’s mantle and crust should be strongly depleted in these highly iron-loving elements, as they would have followed the fate of most of the Earth’s iron, which sank to the core during the early stages of the planet’s formation. Yet we find these elements in the Earth’s crust. Why? While several theories have been put forth, the most likely explanation is that they were delivered by ancient cosmic collisions. It is a rather intriguing thought that the gold ring I wear while typing these words may not have existed without ancient cosmic collisions!

We still do not know the number and magnitude of these ancient collisions, nor their consequences for the nascent Earth, but it is estimated that some of the largest bodies may have been up to 3000 km in diameter. One such collision would have been large enough to wipe out the whole Earth’s surface within hours, either by direct disruption of the impact or by fall back of molten rocks spread in orbit by the energy of the event. It does appear inevitable that during the Earth’s wild years, the first billion years or so, collisions were capable of forever transforming surface environments, and with them, the earliest forms of life. How much do we humans owe to these distant events? What form of life, if any, would have spurred on our planet without these random events? These questions underline the fascinating story behind the creative disruption of ancient cosmic collisions.

Featured image via Pixabay

June 17, 2021

Seven new books on musical theater: from Hamilton to Oklahoma! [reading list]

The musical is perhaps one of the easiest forms of theater to introduce new audiences to, and with theaters around the world anticipating opening their doors again in the coming weeks and months, the joy of the curtain lifting in a real-life setting can be shared once again.

Whether you’re new to the stage or eagerly counting down the days, explore some of our recent titles looking behind the scenes of musical theater.

1. Dueling Grounds: Revolution and Revelation in the Musical Hamilton edited by Mary Jo Lodge and Paul R. LairdHamilton opened on Broadway in 2015 and quickly became one of the hottest tickets the industry has ever seen. Dueling Grounds combines the work of theater scholars and practitioners, musicologists, and scholars in such fields as ethnomusicology, history, gender studies, and economics in a multi-faceted approach to the show’s varied uses of liminality, looking at its creation, casting philosophy, dance and movement, costuming, staging, direction, lyrics, music, marketing, and how aspects of race, gender, and class fit into the show and its production.

2. The Big Parade: Meredith Willson’s Musicals from The Music Man to 1491 by Dominic McHughIn the 1950s, Meredith Willson’s The Music Man became the third longest running musical after My Fair Lady and The Sound of Music: a considerable achievement in a decade that saw the premieres of other popular works by Rodgers and Hammerstein and Lerner and Loewe, not to mention Frank Loesser’s Guys and Dolls and Bernstein and Sondheim’s West Side Story. The Music Man remains a popular choice for productions, with a new revival starring Sutton Foster and Hugh Jackman sure to be one of the highlights once Broadway reopens.

3. From Camelot to Spamalot: Musical Retellings of Arthurian Legend on Stage and Screen by Megan WollerFor centuries, Arthurian legend has captured imaginations throughout Europe and the Americas with its tales of Camelot, romance, and chivalry. The ever-shifting, age-old tale of King Arthur and his world is one which depends on retellings for its endurance in the cultural imagination. Using adaptation theory as a framework, From Camelot to Spamalot foregrounds the role of music in selected Arthurian adaptations, examining six stage and film musicals.

4. Oklahoma! The Making of an American Musical by Tim CarterFirst published in 2007, Oklahoma! tells the full story of the beloved Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. In this revised and expanded second edition, Tim Carter draws further on recently released sources, including the Rouben Mamoulian Papers at the Library of Congress, with additional correspondence, contracts, and even new versions of the working script used—and annotated—throughout the show’s rehearsal process. Carter also focuses on the key players and concepts behind the musical, including the original play on which it was based (Lynn Riggs’s Green Grow the Lilacs) and the Theatre Guild’s Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner, who fatefully brought Rodgers and Hammerstein together for their first collaboration.

5. Sweet Mystery: The Musical Works of Rida Johnson Young by Ellen M. PeckRida Johnson Young (ca. 1869-1926) was one of the most prolific female playwrights of her time, as well as a lyricist and librettist in the musical theater. She wrote more than thirty full-length plays, operettas, and musical comedies, 500 songs, and four novels, including Naughty Marietta, Lady Luxury, The Red Petticoat, and When Love is Young. Sweet Mystery looks at her musical theater works with in-depth analyses of her librettos and lyrics, as well as her working relationships with other writers, performers, and producers, particularly Lee and J. J. Shubert.

6. A Wonderful Guy: Conversations with the Great Men of Musical Theater edited by Eddie ShapiroIn A Wonderful Guy, theatre journalist Eddie Shapiro sits down for intimate, career-encompassing conversations with 19 of Broadway’s most prolific and fascinating leading men. Full of detailed stories and reflections, his conversations with such luminaries as Joel Grey, Ben Vereen, Norm Lewis, Gavin Creel, Cheyenne Jackson, Jonathan Groff, and a host of others dig deep into each actor’s career.

7. Nothing Like a Dame: Conversations with the Great Women of Musical Theater edited by Eddie ShapiroThe counterpart to A Wonderful Guy, Alan Cumming described Nothing Like a Dame, as “an encyclopedia of modern musical theatre via a series of tender meetings between a diehard fan and his idols.” Eddie Shapiro opens a jewellery box full of glittering surprises, through in-depth conversations with twenty leading women of Broadway, including Elaine Stritch, Kristin Chenoweth, Patti LuPone, and Audra McDonald.

Feature image: Times Square, New York City by Florian Wehde. Public domain via Unsplash .

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers