Oxford University Press's Blog, page 107

May 28, 2021

The kings of Prussia become German emperors and Berlin becomes an imperial city

On 16 June 1871 the Prussian army, 42,000 strong, entered Berlin in triumph. Wilhelm I, King of Prussia, had been proclaimed German Emperor five months before in Versailles. The victorious Prussian generals and Chancellor Bismarck led the new emperor, accompanied by his sons and the rulers of other territories in the empire, into the city. Along the way they passed a twenty-metre-high figure of Berolina, the personification of Berlin, and a pile of captured cannon on which stood a huge statue of Victoria. They processed through the Brandenburg Gate and along Unter den Linden towards the Royal Palace. Here they were greeted by a figure of Germania, welcoming her two new children, the territories of Alsace and Lorraine. Berlin was no longer merely the Prussian capital, it had become the capital of the German Empire.

Unter den Linden was hung with painted canvases, on one of which was depicted the myth of Emperor Barbarossa. He was said to have been asleep for 700 years inside the Kyffhäuser mountain with his red beard growing down through the table he was sitting at, waiting for the time when he could awake. Ravens circling overhead indicated the site of his long slumber. He could now arise, since his empire had been founded anew by Prussia. That evening, the emperor, his generals, all the notables of Berlin, and many officers and their families attended a performance of an opera entitled Barbarossa.

When the Reichstag, the Federal Parliament of the new empire, was opened for the first time on 1 March 1871 in the White Hall in the Berlin Palace, Wilhelm I sat on the medieval “Kaiserstuhl” or imperial seat, specially brought to Berlin from Goslar because of its connection to the Salic dynasty. The Salians had ruled as Holy Roman Emperors from 1024 to 1125 and the point of using it was to link the Hohenzollern emperors to an ancient imperial dynasty that predated that of the Habsburgs.

The first monument erected in Berlin to celebrate the newly created empire was the Siegesäule or Victory Column surmounted by a golden winged Victory. Still one of Berlin’s landmarks, it is decorated with rows of gilded cannon captured from the Danes, the Austrians, and the French, all of whom the Prussian had defeated on their march to the imperial throne. A mosaic at the base of the column depicts Germania taking up arms to protect Germany against the French menace, Napoleon I; the German princes supporting their ally Prussia against Napoleon III; Germania, who is simultaneously Borussia, the embodiment of Prussia, accepting the imperial crown; and, of course, the Emperor Barbarossa with his ravens, waking from his 700-hundred-year sleep to welcome the new empire.

In 1888, Wilhelm I died and in the same year so did his son Friedrich Wilhelm, who reigned as emperor for only ninety-nine days. Friedrich Wilhelm saw himself as the successor to the Holy Roman Emperors (whose empire came to an end in 1806) and wished to take the regnal name of Friedrich IV, because the last Habsburg emperor was Friedrich III, who reigned from 1452 to 1493. Bismarck had to insist that the only possible designation for a Hohenzollern who would succeed as both king of Prussia and German emperor was Friedrich III, following on from Prussia’s most famous king Friedrich II, better known as Frederick the Great.

In the same year, Wilhelm I’s grandson Wilhelm II came to the throne. Apart from the enormous “Emperor Wilhelm Monument” in honour of his grandfather, unveiled in 1897 in the centre of Berlin, Wilhelm II’s most striking contribution to imperial Berlin was the creation of the 750-metre-long “Siegesallee” or Avenue of Victory through the wooded Tiergarten. This avenue was lined with 32 life-size marble statues of the princes of Brandenburg and Prussia from the twelfth to the nineteenth century. Each figure was raised up on a pedestal and behind each was a semi-circular marble bench adorned with marble busts of two important men from that prince’s reign. The statues were interspersed with flowerbeds and the whole ensemble was intended as a place for a pleasant stroll, while at the same time providing a lesson in Prussian history. Critics asked why no women were honoured and Berliners laughed themselves silly at this grandiose celebration of the Hohenzollern dynasty, calling it the “Puppenallee”—the Dolls’ Avenue or Puppets’ Parade. The Siegesallee no longer exists and neither does the German Empire, which lasted for less than fifty years.

Featured image: Siegessäule (Victory Column) in Berlin, Germany, public domain via Unsplash.

May 27, 2021

9 new books to explore our shared cultural history [reading list]

How did the Peanuts gang respond to—and shape–—postwar American politics? How did a single game become a cultural touchstone for urban Chinese Americans in the 1930s, incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II, and Jewish American suburban mothers? Were nineteenth-century Brits very, deeply bored?

Cultural and social history bring to life the beliefs, understandings, and motivations of peoples throughout time. Explore these nine books to expand your understanding of who we are.

1. Charlie Brown’s America by Blake Scott BallIn post-war America, there was no comic strip more recognizable than Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Unbeknownst to many, this beloved icon subtly drew on the reality of the time and addressed pressing political issues. Charlie Brown’s America takes the reader on a historical journey of American culture from the Vietnam War, racial integration, feminism, and the future of a nuclear world through the eyes of Charlie Brown, Lucy, Linus, and Snoopy.

2. Whites and Reds by Stephen V. BittnerBittner journeys through the deeply-rooted history of wine revealing why it is at the heart of Russian culture. In the first historical study of its kind, discover how the Russian and Soviet viniculture reveals the instabilities and peculiarities of their respective empires.

3. The Cancer Problem by Agnes Arnold-Forster

3. The Cancer Problem by Agnes Arnold-ForsterBy telling the untold stories of many cancer sufferers in nineteenth-century Britain, The Cancer Problem offers the first historical study of the disease during this time. Agnes Arnold-Foster, a social, cultural, and medical historian, argues it was during these nineteenth-century years that cancer developed the emotional and symbolic status it holds today.

4. Newspaper Confessions: A History of Advice Columns in a Pre-internet Age by Julia GoliaNewspaper Confessions explores the hidden history of newspaper advice columns, asking the question what can we learn about the internet today through this century-old news feature? This thought-provoking book explores the power of “virtual communities” and offers an eye-opening perspective on how early advice columns were essential in defining communication in modern-day America.

5. Mahjong by Annelise Heinz

5. Mahjong by Annelise HeinzMahjong is symbolic of the cultural journey that connects American expatriates in Shanghai, Chinese Americans in the 1930s, incarcerated Japanese Americans in wartime, and Jewish suburban mothers. By narrating the history of this Chinese game, Heinz illustrates how Mahjong defined ethnic communities and social cultures in the United States. Discover how this single game signifies both a level of belonging and separation in modern day American culture.

6. Camping Grounds by Phoebe S.K. YoungWhat does it mean to camp? Phoebe S.K. Young asks this simple question as she discovers the little-known histories of sleeping outside, revealing that camping is more than just an outdoor recreational activity. Camping Grounds takes a deep look into camping since the Civil War and explores its links to the central American value of national belonging.

7. Empire of Ruins by Miles Orvell

7. Empire of Ruins by Miles OrvellWhy were nineteenth-century Americans so utterly fascinated with the ruins of Rome and Egypt? For many, these ruins symbolized a past of ancient mystery as well as an unknown future. In Empire Ruins, the award-winning author highlights the power of visual media and its ability to transform devastation into a thing of beauty.

8. London’s West End: Creating the Pleasure District, 1800-1914 by Rohan McWilliamFrom a place that once only served aristocracy to now the world’s leading pleasure district, the West End of London has become the heart of the consumer and entertainment industries. London’s West End journeys through the making of this now widely public, luxurious, and prestigious space, highlighting how this modest district has shaped much of modern-day, consumer society.

9. Imperial Boredom by Jeffrey A. Auerbach

9. Imperial Boredom by Jeffrey A. AuerbachWhat was life in the British Empire really like? This thoroughly-researched book provides a new lens to examine the working and living experiences of men and women in the Empire, suggesting the perceived lavish lifestyle was not reality. Imperial Boredom challenges the long-established view that it was a time of adventure and excitement, arguing that life for many in nineteenth-century Britain was in fact unfulfilling, and “boring.”

Featured image by Justine ft via Unsplash

May 26, 2021

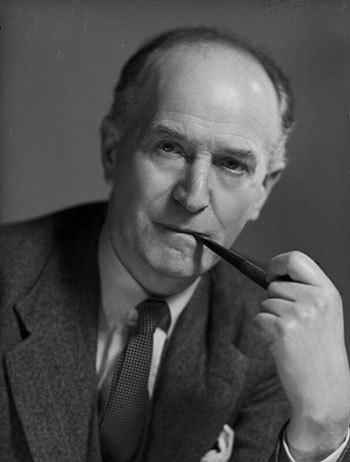

Eric Partridge as an etymologist

Eric H. Partridge, 1899-1974. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.)

Eric H. Partridge, 1899-1974. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.)Eric Partridge is deservedly famous among word lovers. His main area of expertise was substandard English, that is, slang and cant. He knew informal and underworld English like probably no one of his contemporaries. Decades later, his books are in no way outdated, even though excellent work has been done in that area since his time (new historical dictionaries of slang, improved definitions, and secure or at least plausible etymologies, among others). However, Partridge was not a philologist in the strict sense of this term. I have some reason to believe that he could not read German and consulted etymological dictionaries in a perfunctory way. Undaunted by his lack of expertise, he decided to compile an etymological dictionary of English, because he concluded that the structure of the existing dictionaries is inconvenient. In that he was partly right. Arranging related words in nests (and this was his plan) makes etymology not more reliable but sometimes more transparent. Though reshuffling other people’s information without the ability to evaluate or improve it was not an enterprise worthy of a researcher of his caliber, he brought out his own etymological dictionary of English, and many people use it, because they don’t realize its derivative nature.

By contrast, in his journal articles and other books, Partridge made numerous ingenious suggestions about the derivation of slang words. Curiously, none of them made its way into his dictionary! It so happens that the origin of slang is often even murkier than the origin of “standard” words, and intelligent guessing in this area may yield useful results. I don’t think anyone has put together Partridge’s etymological notes on slang, and today I’ll make a few of them more accessible to the public. No revolutionary discoveries should be expected from this post. It is rather meant as a tribute to an indefatigable word hunter and a great expert in the field that interests many people.

Beak The prototype of a magistrate? (Image by gipe25 via Wikimedia Commons)

The prototype of a magistrate? (Image by gipe25 via Wikimedia Commons)“Justice of peace, or magistrate.”

“…probably it is connected with beak, a bird’s bill, and, like so much early cant…, was perhaps due to those university men who ran wild in London. I suggest that beck, as an anglicized form of the French bec, is basically the same as, and afterwards became beak.”

Did Partridge mean that a beak is a person poking his nose into other people’s business or snatching things with it?

Binge“The word may be due to a confusion and combining of the Lincolnshire binge to soak, and the cant bingo, defined as ‘brandy or other spirituous liquor’ by Francis Grose [the author of an 1811 dictionary of slang]. … Dr. [James A. H.] Murray in 1888 [in The Oxford English Dictionary] suggested that bingo was b (for brandy) and stingo; very diffidently I suggest that a Lincolnshire wit gave to binge, to soak, the termination o (after deleting e) on the analogy of the much older stingo, strong ale or beer….”

The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, 1966, later The ODEE, no longer refers to Murray’s blend but, like Partridge, tentatively connects binge with the dialectal verb binge, without, however, mentioning stingo. Partridge was a careful reader of Joseph Wright’s The English Dialect Dictionary and drew several promising conclusions from his reading. Northern words did occasionally make their way into the slang of London and southern counties, as evidenced by the history of the noun slang itself: see the post for 28 September 2016. The difficulty consists in tracing the word’s suggested route from Lincolnshire to London. The ending -o needs no defense: compare weirdo, typo, and even lie doggo (with regards to this obscure idiom, see the post for 13 November 2019).

Bone“To seize; apprehend; steal”

“…may be a figure of speech based on a dog’s removal of a bone to a place of safety.”

The ODEE gives no references. Though it calls the verb bone a word of unknown origin, it cites Partridge’s suggestion as probable.

Scrounge“To acquire illicitly” surfaced during World War I.

“…the real solvent is supplied by the late and much lamented Joseph Wright, who, in his ‘English Dialect Dictionary,’ makes it clear that it is a North Country word, that one of the secondary meanings is ‘to wander about idly,’ and that one of the meanings of the noun is ‘a thorough search’.”

Here the fit is not so good as in the previous case. The ODEE goes its own way and suggests an alteration of scrunch, itself an expressive alteration of crunch “crush, squeeze.” The root-final –dge, as in dodge, nudge, fidget, etc. is indeed expressive. However, the way from “crush, squeeze” to “pilfer, snaffle, etc.” is not quite straight, even though nab and nap in kidnap, not mentioned in the dictionary, provides a parallel.

Pozzy“Jam, marmalade.” The word is enveloped in total obscurity.

“Some of the best authorities [those familiar with the dish, rather than linguists] suggest a West Indian origin; others that it is from a South African language. Very tentatively I suggest posset, by a corruption of spelling and a diversion of the meaning.”

The word, popular at the time of World War I, seems to be forgotten, and its origin hardly bothers anyone. Posset is a drink, and Partridge made a heroic attempt to explain how posset could become pozzy:

“I suggest that an Englishman, hearing a native word for some mixture resembling either a very thick, sweet posset or a thin, watery jam, applied the name posset and that, conscious of the twisted meaning of a good old word, those who used posset for near-jam, then by a natural transition for jam, sympathetically debased the form of the word.”

Obviously, this “purely semantic theory,” as Partridge called his suggestion, has little chance to survive, but it may be worthy of mention that jam and posset are also words of dubious, almost unknown, origin, though a few conjectures exist.

Cobber Cobbers, chums, pals. (Image by Matheus Ferrero via Unsplash)

Cobbers, chums, pals. (Image by Matheus Ferrero via Unsplash)“Pal, chum.”

“Joseph Wright’s dictionary offers two possibilities: the Cornish cobba, a simpleton, a bungler, may have been transported to Australia [where it means “comrade”; incidentally, Partridge was born in Australia] and corrupted to its present spelling and meaning; or, more likely, it is a development of cob (originally Suffolk dialect), to take a liking to.”

The word cob, with its multitude of senses, is one of the most obscure English nouns (see also the post for 13 January 2021: “Cubs galore”). The verb to cob “to take a liking to” is as impenetrable as the noun cob. An etymological stream of consciousness may carry us in many directions. For example, cobble is another verb of unknown origin. By back-formation, cob could have been coined from it, and, if one can cotton to someone, why not cob? Hence cobber. Ingenious but probably useless.

Grouse“To grumble” was originally a soldier’s word. It resembles Old French groucier ~ grouchier “to grudge” but is too late to be its descendant.

“…the missing links will probably be found, perhaps in such words as grudge and the American grouch.”

Initial gr- is a common sound-imitative and sound-symbolic group in the English language: think of grumble, grim, grin, groan, and many others like gruesome and Grimalkin “devil.” Partridge may have been on the right track, but we should rather look for similar formations than for exact etymons or missing links, which, as experience show, tend to remain missing.

If this potpourri has any value, next week I may go on with Eric Partridge’s tentative etymologies of slang and cant.

Featured image by drew007m via Flickr

May 25, 2021

The SHAPE of things [podcast]

In January, Oxford University Press announced its support for SHAPE, a new collective name for the humanities, arts, and social sciences and an equivalent term to STEM. SHAPE stands for Social Sciences, Humanities, and the Arts for People and the Economy and aims to underline the value that these disciplines bring to society. Over the last year or so, huge attention has—rightly—been placed on scientific and technological advancement but does that mean we’re overlooking the contribution of SHAPE in finding solutions to global issues?

Today’s episode of The Oxford Comment brings together two leading voices from SHAPE and STEM disciplines to discuss how we might achieve greater balance between sciences and the arts. In the episode, Dr Kathryn Murphy, a Fellow in English Literature at Oriel College at the University of Oxford, and Professor Tom McLeish, inaugural Professor of Natural Philosophy in the Department of Physics at the University of York, discuss the origins of the SHAPE/STEM divide and what might be done to address it.

Check out Episode 61 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · The SHAPE of Things – Episode 61 – The Oxford CommentOxford Academic (OUP) · Environmental Histories and Potential Futures – Episode 60 – The Oxford CommentRecommended readingFor more from the experts in today’s episode, you can read the introduction to The Poetry and Music of Science by Professor Tom McLeish or “Of Sticks and Stones”, a chapter from On Essays, co-edited by Dr. Kathryn Murphy. Both of these texts were referenced in this episode, helping to explain the many and complex connections between SHAPE and STEM. Alternatively, take a deep dive into the world of physics with the first chapter of Professor Tom McLeish’s Soft Matter: A Very Short Introduction.

For more about SHAPE, check out OUP’s SHAPE hub or catch up with the two-part conversation between Sophie Goldsworthy, OUP’s Director of Content Strategy & Acquisition, and Professor Julia Black, Strategic Director for Innovation at the London School of Economics and Political Science and incoming president of the British Academy, introducing SHAPE and what its future might look like in light of the pandemic.

Featured image: Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1490), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The impact of COVID-19 on distance learning universities: The Open University

The coronavirus pandemic greatly impacted traditional universities, with closures happening globally and students turning to remote learning. But what impact is COVID-19 having on institutions that historically teach mainly online? What have been their biggest challenges? Did they adopt any new strategies? We spoke with Claire Grace, Head of Content and Licensing at The Open University (OU), about the impact of COVID-19 on distance learning universities, and the OU in particular.

What have been the OU’s key initiatives undertaken during the pandemic?Our Library Live Engagement Team created and delivered two live streamed training events for librarians at other institutions to support them with the “digital pivot.” We saw over 1,000 librarians join this session which allowed our librarians to share their expertise in teaching “library skills” online. We have also endeavoured to support partner institutions whose students have lost access to their print libraries. This has been mainly with advice and guidance, encouraging them to take up of “free” temporary access that different publishers provided to assist during lockdown. This has also got us thinking about the need to work with key publishers to come up with a better, evidence-based model for smaller print-based libraries to provide some sort of access to online alternatives for their students post-pandemic.

Claire Grace, Head of Content and Licensing at The Open UniversityWhat have been the biggest challenges and barriers for the OU as a result of COVID-19?

Claire Grace, Head of Content and Licensing at The Open UniversityWhat have been the biggest challenges and barriers for the OU as a result of COVID-19?The fact that The Open University operates across the four nations of the UK posed challenges as four different sets of health and lockdown policies needed to be consulted when we offered support to our students. Loss of access to print was another barrier for us. Yes, even for a university that teaches mainly online, print is still important. This is especially true in the Arts and Humanities and for postgraduate students and researchers. The other impact that loss of print had was in our copyright acknowledgement work where academics had forgotten to write down the reference for the print book that they had been using in the Bodleian Library before lockdown! Thankfully the skills of our Document Supply and Inter-library Lending team could remedy this so all third-party rights were acknowledged appropriately.

In general, would you say the pandemic had less of a negative impact on the OU than on traditional institutions?Overall yes, we’ve seen far less negative impact on what we do and how we do it because most of what we do is already online and digital. We were able to move to home working overnight and then iron out any problems that individuals were experiencing. Our students should have seen no immediate impact on their access to library content or services. However, our staff and students faced the same pressures that everyone else faced, with demands of homeworking, home-schooling, and the concern for people’s health and wellbeing during the pandemic. There has also been a very positive impact in terms of an increase in course production. While this of course is great to see, it has at times felt at odds with the focus on staff wellbeing and mental health due to the increased pressures put on our academics and various parts of library service to meet tight timescales and high workloads.

Did you notice more students joining the OU in the past year?

Did you notice more students joining the OU in the past year?Yes, the OU has experienced an upsurge of interest in its courses and qualifications both for new students and from students wanting to use credit transfer from other institutions. We have yet to see how sustained this increase in student numbers might be but we are optimistic that the quality of our teaching and course design will translate into wider recognition that the OU’s method of study for Higher Education qualification is a more suitable option for many potential students at both undergraduate and postgraduate level. We also saw a massive uptake of our OpenLearn Open Access course content giving it the international recognition that is has so long deserved.

Initiatives such as this help the OU fulfil its social mission “to be open to people, places, methods and ideas,” our vision “to reach more students with life-changing learning that meets their needs and enriches society,” and our commitment to be guided by the enduring OU values of inclusivity, innovation, and responsiveness. At times the demand for this content was so high that it actually impacted the efficiency of our staff network—quickly remedied by our fantastic IT teams.

Have you changed your social media strategy to support your students?Overall there has been an increase in our use of social media as a method of engaging directly with our students in the places that they need us to be. We have open feeds in Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, which are monitored by staff with the aim of directing enquiries to the most effective source and fostering a sense of belonging to the OU. Additionally, we highlighted our support for students in developing their study skills, which includes live online training, recorded training, and stand-alone activities on our website.

While we do these things already, we have made additional effort to connect with students more often during the past year. Our engagement rate has been high throughout as we provided these informational resources as well as lots of fun content for keeping spirits up and providing some levity during this stressful time. We also point students and staff to content and resources to support their mental health and wellbeing. Lastly, the Library created new social media content to offer reassurance and friendly faces with videos of library staff working from home.

Images courtesy of Claire Grace. Used with permission.

May 23, 2021

Cybervetting in hiring: the hunt for moral performances

Cybervetting refers to the use of online information such as Facebook posts, LinkedIn profiles, and Google searches to evaluate job candidates. In roughly 7 out of 10 workplaces in the US, human resource (HR) professionals and other individuals involved in hiring use cybervetting to get to “know a person” beyond information provided on a resume. But what are cybervetters really attempting to learn, what inferences do they make, and what does any of this have to do with how a candidate will perform on the job?

Proponents of cybervetting often frame the activity as a means to reduce hiring risks and maximize “culture fit” between new hires and the organization. However, recent research based on interviews with HR professionals shows that its main use is to evaluate job candidates’ moral character. Cybervetters use ambiguous digital signals like photos to make broad inferences about individual character and lifestyle choices.

Cybervetting seeks to evaluate job candidates’ conformity with—or deviation from—social norms associated with idealized workers. For example, when HR professionals express a preference for online profiles that depict “an active lifestyle,” “going on hikes,” or love of skiing, they set up an implicit moral standard: job candidates are expected to engage in and display the correct lifestyle. Usually, the associated activities are irrelevant to performance in the jobs for which candidates are applying. Nonetheless, deviations from ideal worker norms are penalized and can lead to discriminatory hiring outcomes, as when preferred “active” lifestyles are associated with white, youthful, middle- and upper-class individuals who lack disabilities.

The downside of cybervetting also shows up in the search for “red flags,” which are online indicators of deviant and potentially problematic behaviors. The most commonly cited red flag is a photo of a person drinking an alcoholic beverage. Deviant acts such as this call into question how job candidates might disrupt the moral order of the workplace. In addition, evaluators often use hypothetical scenarios to imagine how red flag activities might impede candidates’ professional performance.

Ironically, while cybervetting is pitched as a means to better “know” a job candidate, online self-presentation is one of its most common selection criteria. Whether or not a worker is required to interact with the public, job candidates are expected to carefully curate their online profiles. For example, even at companies that host employee happy hours, HR staff may view social media images of drinking as highly problematic. This ultimately undercuts claims of using cybervetting to reveal authentic personal selves. Instead, it makes online profile management an entirely new criteria for employment.

The criteria used to evaluate job candidates via cybervetting can have numerous negative consequences for work organizations. Cybervetting can lead to legal challenges due to concerns about inequitable hiring practices. Screening job candidates based on cybervetting can also lead to an increasingly homogenous workforce, which has been shown to negatively impact creativity and profit margins. Furthermore, cybervetting is perceived by most workers as an invasion of privacy, leading to doubts about the procedural justice of organizations that practice it and a tendency to avoid applying to them.

How cybervetting is used in organizations depends on their mission, capacity, and resources. HR staff in non-profit and government organizations are the most skeptical of cybervetting because of concerns that it may reduce equitable hiring and promote privacy invasion. Organizations that emphasize efficiency and profit-making tend to be more open to cybervetting. HR professionals in third party recruitment and staffing agencies are the most enthusiastic practitioners of cybervetting, as these types of organizations are largely shielded from its negative consequences.

Organizations can surmount these problems. First, organizational leaders must take responsibility for managing cybervetting and its consequences. This is not the responsibility of job seekers, who may be unaware of whether their online information is perused, how it is evaluated in the present or future, and how they are helped or disadvantaged as a result. Furthermore, advice provided to jobseekers will often be contradictory. For instance, some cybervetters seek authentic selves, while others look for cultivated and censored profiles; some see profile pictures as a must, while others avoid them out of concern for discrimination.

Second, if organizational leaders and HR staff choose to engage in cybervetting, they should consider how the online information they use to evaluate job candidates relates to specific tasks involved in their jobs. Instead of using hypothetical scenarios to rationalize choices based on cybervetting after the fact, criteria of evaluation should be developed up front and then applied consistently.

Finally, organizational leaders should question whether cybervetting is useful rather than assuming it is. What are the risks? What are the goals? How can the actual contributions and limitations of this practice be gauged, and how do they measure up? In short, they should approach cybervetting with skepticism and a critical eye. If organizational leaders are not willing to address these difficult questions head on, then cybervetting is best avoided.

May 20, 2021

Accessibility in academic publishing: more than just compliance

If you’re lucky enough to be able to simply open a webpage and engage with the content hosted there, the likelihood is that you rarely think about what it would be like if you couldn’t do that. What if you were visually impaired but the page was indecipherable to your screen reader? What if you were colour blind and struggled to pick out buttons or interactive elements on a page? What if a physical disability meant you use your keyboard to navigate webpages, but it refused to select the area of the page that you need to access?

Accessibility is one of the fundamental principles of publishing and disseminating content in a world where the majority of our interactions take place through digital means. At its heart, accessible design is about ensuring all content and digital functionality are available to everyone regardless of physical or cognitive impairment or device used. However, accessibility is not just an ambition: in many jurisdictions it is now a legal requirement with legislation stating that materials cannot be adopted by institutions like universities without meeting a certain accessibility level. This has made accessibility a significant focus area for academic publishers and libraries alike.

“Accessible design is about ensuring all content and digital functionality are available to everyone regardless of physical or cognitive impairment or device used.”

At Oxford University Press (OUP), we realized that we were facing some challenges around accessibility a few years ago. The issue was really brought home to us when we engaged with librarian colleagues at the Open University who invited us to see some of the issues for ourselves. As Claire Grace, Head of Content & Licensing at the Open University, explains, “Some products are essential for certain qualifications or accreditations and if they are not accessible it makes it difficult for a large number of our users to be successful in their studies. We have to try to find workarounds but, in some cases, this is impossible, so we have to support students individually or risk causing dissatisfaction or even legal complaints.”

What we witnessed in our meetings with the Open University was very revealing: faculty members who couldn’t use content published by Oxford, even on our then-new platform, Oxford Academic, because it wouldn’t work properly with a screen reader and wouldn’t fully allow for keyboard-only navigation. We left that meeting with the stark realisation that what we were offering was just not good enough. From that point, OUP has made accessibility a core strategic priority.

So, what does addressing accessibility needs entail? Our first task was to examine every aspect of our existing digital platforms where users need to navigate or engage with content, and to understand what development would be required to deliver a universally accessible experience. But, as well as seeking to achieve compliance with the guidelines, our overarching aim has always been to consider accessibility, usability, and inclusion as three strands of the same goal—to deliver digital platforms that work for all users.

We made a huge number of changes to areas such as page and menu navigation, tables and images, form functionality, modals behaviour, and colour contrast so that all elements can be accessed by a screen reader and navigated via keyboard. For example, we realised that both the “advanced search” and “communications preferences” functionality couldn’t be used properly through keyboard-only navigation meaning that users were unable to perform the most powerful searches or let us know how to contact them. Once you begin to interrogate your platforms with accessibility in mind, you uncover a huge amount of progress that can be made.

“Accessibility is not a one-off activity. It has to be embedded as a strategic and operational priority in an organisation.”

An important aspect of this was transparency about the work we were doing. A regularly updated accessibility statement shows not only a commitment to accessibility as a goal but provides practical information for users and librarians.

But progress doesn’t stop here. Ensuring content and platforms offer the highest level of accessibility is an ongoing (and never-ending) process and an ever more important one. As Claire explains, “accessibility is not a one-off activity. It has to be embedded as a strategic and operational priority in an organisation so that everything is designed to accessible principles, staff are trained in accessibility awareness, and funds are put in place to support the delivery of this strategy.”

Making accessibility a strategic priority doesn’t just benefit a subset of users, but all users. The continued transition to digital solutions in academic publishing has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and our response cannot simply be to make sure content is available online—it must be accessible to everyone who needs to use it. As new user requirements emerge, or new features and functionality are developed, publishers have a responsibility to consider all possible accessibility scenarios to ensure no group is left behind.

A version of this article was previously published in UKSG eNews in April 2021.

Featured image by ComMkt

The “Ready… Set… Go!” phrase structure in Classical Era music

Ready… Set… GO! We all know the joyful anticipation of that exciting phrase. Whether getting ready for a “race” with my granddaughter or waiting for the gun at the start of a half-marathon, just the thought of it brings a bit of an adrenaline rush. This mindset transcends culture, space, and time, and presents itself structurally in Classical Era music. Let’s dig in to discover how the anticipation of “ready…set…GO!” is captured through composers’ clever use of phrase structure to catch the listener’s attention and move the music forward.

Few people can say they’ve never heard the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with its “ready…set…GO!” driving two-measure “ti – ti – ti – tah” that is restated a step lower for three measures, and then takes off in a sixteen-measure whirlwind. Experiencing formal structure is a journey and the journey is carefully crafted. Excitement is created by manipulating the structure “in good taste.”

Good taste starts with Vierhebigkeit as Johann Philipp Kirnberger describes in The Art of Strict Musical Composition (1771): “The best melodies are always those whose phrases have four measures.” But, that’s the typical, predictable route. As I heard Malcolm Bilson say, “all great composers follow the rules…most of the time!” Let’s see how this square formula can be manipulated.

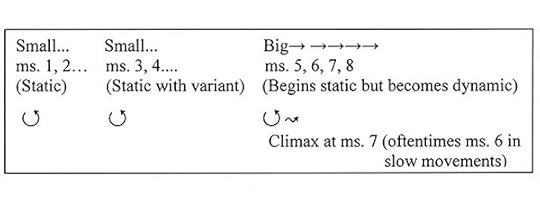

In The Classical Form (1998), William E. Caplin describes the hybrid structure benignly as “presentation + continuation”. But to get at the pathos, the energy, the excitement, we need to feel that we are going somewhere. The below diagram reveals the vibrant momentum that is palpable in great works:

1 + 1 + 2 Structure. Beethoven, Twelve Minuets WoO 7, no. 11, mm. 1-8. Copyright 1990 by G. Henle Verlag, Munich.

1 + 1 + 2 Structure. Beethoven, Twelve Minuets WoO 7, no. 11, mm. 1-8. Copyright 1990 by G. Henle Verlag, Munich.This formula lends itself beautifully to the forward propulsion in Classical pathos. Taking it to the literature, let’s start small, with a Beethoven Minuet. Listen to the energetic surge in the simple 1 + 1 + 2 structure.

1 + 1 + 2 Structure. Beethoven, Twelve Minuets WoO 7, no. 11, mm. 1-8. Copyright 1990 by G. Henle Verlag, Munich.

This formula is also found in many sonatas such as those by Beethoven.

2 + 2 + 4 Structure. Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 2, no. 2/I, mm 1-8. Copyright 2007 by The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music.

2 + 2 + 4 Structure. Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 2, no. 2/I, mm 1-8. Copyright 2007 by The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music.Again, the momentum created is audibly compelling.

2 + 2 + 4 Structure. Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 2, no. 2/I, mm 1-8. Copyright 2007 by The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music.

The more scores I study, the more I find a preponderance of “ready…set…GO!” and begin to wonder if this clever manipulation of Vierhebigkeit isn’t the norm, rather than a hybrid structure.

Haydn and Beethoven take it to a whole new level. For instance, in the third movement of Haydn’s Piano Sonata Hob. XVI:50/III, the opening section throws the listener for a complete loop (particularly a Classical Era listener who is anticipating some semblance of balance). Rather than an expected four-measure question followed by a four-measure answer or even a 2 + 2 + 4 “ready…set…GO!” plan, the phrases follow a 7 + 3 + 13 plan which I call calculated chaos. Give it a listen.

7 + 3 + 13 Structure. Haydn, Piano Sonata Hob XVI:50/III, mm. 1-24. Copyright 1990 by G. Henle Verlag, Munich.

Or Beethoven, who takes the norm and demonstrates his manipulative genius in Piano Sonata, op. 31, no. 1. In the first movement, the phrase structure found in measures 136-193 of the development is perfectly yet atypically crafted. Each of the first three phrases outline tonic, supertonic, dominant in ascending key centers (B-flat, C, and D) before settling on D for 32 measures, where tension ever-increases by starting with the dominant, then layering the dominant-seventh, and finally, the dominant-ninth to take the tension as far as he can before the final return to the tonic key in the recapitulation. The Skeleton Table plots out the overall plan.

Listen to the carefully crafted frame Beethoven sets down.

Skeleton Structure. Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 31, no.1/I, mm. 134-193.

Now, over this frame, Beethoven creates an exciting, frenzied journey from development to the recapitulation.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 31, no.1/I, mm. 134-193. Copyright 2007 by The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music.

Perhaps you are now ready to discover your own “ready…set…GO!” to bring new energy and vitality to your performing. Following these three suggestions will make your job easier:

Work from Urtext scores to ensure you are decoding from what the composer wrote.Don’t dismiss small forms; they didn’t. Start simple with minuets and dances. There are dozens and dozens left to us by Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart.Dissect the score down to bare bones—bass line alone, first note of each measure, bass and soprano—to determine harmonic function and structural direction.Awareness and use of this “ready…set…GO!” phrase structure tool not only brings historical veracity to one’s playing, it invigorates the experience with a sense of joyful anticipation from the first notes. Grab a score, dig deeply to uncover the bare bones, and perform your own “ready…set…GO!”

Feature image: Fortepiano by Donna Gunn, used with permission.

May 19, 2021

My dearest foe in heaven, or: not near but dear

It was Hamlet who was ready to meet his dearest foe in heaven. In addition to dear “regarded with affection,” from dēor(e), English once had dear “savage, wild, grievous,” from dēor. Shakespeare used this word many times. It often occurred before him (for example, in Beowulf and in the Middle period) but slowly disappeared, possibly because having homonyms with two almost opposite meanings caused confusion, even though their coexistence had not bothered anyone for centuries and though such cases are known. There even is a learned term for this phenomenon (enantiosemy; consider Latin altus “high” and “low,” that is, “going all the way up or down”). A natural question springs to mind: are we dealing with two different adjectives or with one, despite its confusing semantics? Though James A. H. Murray, the OED’s first editor, refused to commit himself, he found the idea of homonyms somewhat more appealing. In any case, the German scholar to whose publication he referred in the entry could not imagine such a violent clash of senses in the same word.

A good deal depends on understanding the origin of dear1 and dear2. As ill luck would have it, the etymology of dear1 is debatable, and that of dear2 supposedly unknown. Yet the difference between “debatable” and “unknown” should not be disregarded. Dear, as in my dear friend, has cognates in other languages, while dear “savage” is seemingly isolated. This isolation comes as a surprise: adjectives, do not appear from nowhere. Old English dēor(e) (our dear1) has been recorded with the following senses: “beloved; costly; valuable, precious” and “glorious, noble, excellent.” In the Germanic languages of the early Middle Ages, love seldom meant “very strong affection, a feeling between two individuals.” It habitually referred to things pleasurable, worthy of attaining, and hard to get. Dear developed from some such nucleus, that is, “costly.”

[image error]Dear and near? (Image by Elroy Serrao via Flickr)It is curious how ramified the senses of the words related to “dear” are. English dearth is a noun with the same suffix as in wid-th, heal-th, warm-th, and slo-th, among others; despite the difference in today’s pronunciation, its root is dear. What is costly is, naturally, scarce. In Frisian, we find the verbs with this root meaning “to endure; to punish” and “to have the heart to do something,” while in Middle High German, the reference is “to feel compassion for one.” The Modern German for “dear” is teuer “dear.” It is related to the verb (be)dauern “to regret” (never mind the t ~ d difference: it has been accounted for). In Middle English, the verb douren, probably “to grieve,” is close to (be)dauern. Should we interpret “to regret; feel pain” as reference to things too costly (“dear”), requiring too much effort? The connection is not improbable.

The verbs dauern ~ douren throw some light on the fact that in the Slavic languages, dur– is the root of numerous words meaning “wild; mad; stupid” (Russian durak, stress on the second syllable, means “fool”). “Wild” reminds us of English dear “fierce, wild, ferocious,” and this fact is a strong argument for treating dear1 and dear2 as (from a historical point of view) being two senses of the same word, rather than homonyms.

A very dear warrior. (Image by Shakko, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A very dear warrior. (Image by Shakko, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)In the history of the adjective dear, one sense is, I believe, of special importance. Old English dēor(e), as we have just seen, could have meant not only “hard to get, available after a serious effort” (hence “desirable and inspiring strong feelings”) but also “noble.” The same holds for Old Icelandic dýrr. Curiously, the noun dýrð, an exact counterpart of English dearth, mentioned above, means “glory; splendor; excellence”! Despite this great multitude of senses, it is probably reasonable to assume that the most ancient meaning of the adjective dear was “requiring a strong effort”; hence “fierce, wild; hard to obtain; costly; precious,” and of course “dear,” whether “expensive” or “priceless.” According to what we know about the Old Germanic ethos, monsters and heroes were believed to be endowed with similar qualities, but what was “noble, valorous, praiseworthy” in the hero was “ferocious, deadly” in his enemy. In Beowulf, Beowulf, as well as his opponents Grendel and the dragon, are occasionally called by the same word āglǣca, glossed in our editions as “assailant.” Its root means “awe, misery.” One pays a dear price for experiencing both.

This then is how dear must have developed in two seemingly opposite directions. The situation is the same as with Latin altus: if you look up, altus is high; if you look down, altus is low. Likewise, the end of a thread is its beginning: a piece of thread has two ends or two beginnings, if you wish. Some good authorities hesitatingly (very hesitatingly!) admit that Old English dēor(e) and dēor are two senses of the same word. In my opinion, both their hesitation and the common statement “origin unknown,” applied to dēor “savage, fierce,” are groundless. True, the English way was rare, for neither German teuer (along with its West Germanic cognates in Frisian and Dutch) nor the cognates or reflexes of dýrr in the Scandinavian languages ever meant “savage.”

Yet such individual developments are not uncommon. For instance, in Old English, dream meant “joy; music” and had no reference to slumber. Etymologists tend to look upon it as a homonym of dream “vision in sleep.” In the spring of 2019, I devoted a series of three posts to the refutation of this idea (27 March, 3 April, 10 April). As far as the use of dear in later English literature is concerned, it may be worthwhile to quote Ernest Weekley: “In Anglo-Saxon and Middle English poetry, revived by Spenser and used by Shakespeare and later poets, by whom it was probably felt as an oxymoronic application of dear1.” Perhaps so, but we are interested in the early stages of dear1 and dear2.

[image error]Beginning and end: which is where? (Image by A R on Unsplash)The great German etymologist Friedrich Kluge believed that dear was related to deer. Deer, as is well-known, once meant “animal” (as do Dutch dier, German Tier, and the related Scandinavian forms) and only later acquired the sense “hunted animal” (hence “the most often hunted animal”). The origin of deer and its cognates (Gothic dius, etc.) poses no problems. Everywhere in Indo-European, the root of those words means “to breathe”; hence “spirit, soul.” The same underlying meaning can be seen in animal (anima!) and, very probably, beast. The creature called “dius,” etc., from Germanic deuzam, was a wild animal. Passion, ferocity, impetuosity, and all kinds of uncontrolled emotions were taken for granted in naming that deuzam. A direct path leads from deuzam to dear “savage.” There are indeed some problems with ablaut here, but they are hardly insurmountable. Though Kluge’s etymology was dismissed by later scholars (I never see it mentioned), it solves the genesis of the English adjective in the best way possible. Regrettably, he stopped in the middle and dissociated dear1 from dear2 (“ferocious” from “expensive”). The other hypotheses, including the Welsh origin of dear, strike me as less appealing.

The rather mysterious phrases dear me, o(h) dear no, and dear knows (the latter Scottish) were at one time an object of controversy between Walter W. Skeat and A. L. Mayhew. Mayhew defended the hypothesis presented in the OED: dear is allegedly the product of omission, from Dear Lord. Skeat derived the phrases from French. The OED’s point of view seems to carry more conviction.

Featured image by Scott Carroll via Unsplash

May 18, 2021

Fading signs of son preference

Son preference is a phenomenon that has strong historical roots in many western and non-western cultures. It manifests in various forms, ranging from parents investing more time and resources in their sons than their daughters to the dynastic concepts of patrilineal succession. Naturally, such gender preference can have various social and cultural origins, however one of the most common motifs underlying its existence is the unequal position of men and women in the society.

The inequality of men and women is a tenacious problem, and most of the modern history has been characterized by the fight against it. And while this fight is far from over, we are seeing signs of improvements: people’s gender role beliefs are becoming less traditional, the gender wage gap is narrowing, and the single-earner model of household is being replaced by the two-earner model.

All these factors suggest that the positions of men and women in modern societies are becoming more aligned. In this context, it is natural to ask whether son preference is yet another social phenomenon that is losing its historical ground. Could it even be that in some domains of life such preference is already a thing of the past?

Social scientists have been investigating son preference in modern societies using many statistical techniques. The most common analyses are based on population-level fertility data. For example, by comparing the annual numbers of newborn boys to newborn girls, researchers can capture the extent of the most extreme expression of son preference: selective abortion or infanticide of female offspring (which are still common in India and China).

In western countries, the influence of son preference on fertility is generally thought to be more nuanced, not affecting the genders of children born into a family, but rather their numbers. Historically, parents of girls have been observed to have more children than parents of boys. This association (commonly found in the data covering the second half of the 20th century) has been interpreted as a sign of son preference, since the parents were more likely to try for an additional child if there was no son in the family.

However, new evidence suggests that fertility patterns are changing. Recent study using data from the 2008-13 US Census concluded that there is little evidence of a lasting son preference on fertility in the United States. In fact, the study has shown that the association has flipped: parents of girls now have fewer children than parents of boys. In our research using the Dutch population data, we find exactly the same pattern. This suggests that couples in the West now exhibit a slight daughter preference in terms of their childbearing decisions.

The existence of son preference has been also commonly inferred from marriage and divorce data. In the United States, parents of boys have been found more likely to legitimize their children by marriage, and less likely to divorce than parents of girls. While the magnitudes of these differences are generally quite small, they too have been interpreted as signs of son preference (with the conventional narrative being that fathers of sons are less likely to leave the family).

But also in this domain, the evidence is becoming somewhat dated. The majority of studies base their findings on data corresponding to the middle or second half of the 20th century, which leaves the preferences of modern families relatively unexplored. Using more recent marriage and divorce data from the Netherlands, we did not find any evidence of lasting son preference on marriage and divorce decisions. Parents of girls were just as likely to legitimize their children by marriage as parents of boys, and while we did find parents of boys less likely to divorce than parents of girls, further analyses revealed that this finding is unlikely to be explained by son preference. This is because the effect proved to be highly age-specific, manifesting only in the teenage period of the child’s life. If parents were indeed getting divorced because of fathers’ latent son preference, they would not wait 13 years before doing so. We would be much more likely to see divorce disparities with respect to children’s genders throughout children’s lives.

While these findings challenge the conventional narrative of son preference in the modern western societies, it needs to be acknowledged that son preference remains a major social force in many non-western countries. Particularly worrying are the male-biased sex ratios at birth (SRB) in China and India, which are generally regarded to be a consequence of sex-selective birth control practices. These demographic distortions of large populations are likely to have far-reaching socio-economic consequences, many of which are yet to be fully realized or even understood.

It is worth noting that the gender bias of the Chinese SRB has peaked around 2008, and it has been steadily declining from this point onwards. And while the ratio remains biased even today, it is likely that the gradual relaxing of Chinese fertility-control policies and the coinciding changes of gender role beliefs will lead to further improvements in the future as well. In contrast, the gender bias of Indian SRB has remained more persistent, exhibiting no clear trend over the last 20 years.

Nevertheless, if the western experience is of any indication, son preference is a phenomenon that is malleable to culture change. With the improving position of women in societies around the world, we are likely to see the son preferences slowly fading away, eventually disappearing completely. In fact, based on the observed fertility patterns in the western countries, it will be interesting to see whether future families will reinforce their preferences for daughters, and what will be the eventual consequences for this nascent phenomenon.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers