Oxford University Press's Blog, page 105

June 16, 2021

Still plowing with my heifer

This blog was born on 6 March 2006, more than fifteen years ago. Since that date, my posts have been appearing every Wednesday, except when the New York office of Oxford University Press was closed for some holiday. Today’s post is number. 800, and every hundred numbers I, in complete solitude, celebrate the event. It takes two years to write a hundred essays. Since I fear to plan so long ahead, this time I decided to wish myself many happy returns of the day in public.

What can I say fifteen years later? Like every diligent researcher, I have learned more than anyone else from my work: hundreds of pages read, countless hypotheses weighed, a few seemingly useful conclusions reached. When I began, I expected that I would be showered with letters, William Safire-like. Most fortunately, this did not happen. Safire was not a linguist. He called specialists when he did not know the answer, while I have only myself to rely on. (His columns have been gathered in numerous volumes and made him famous, another great difference between us.) Also, I am fully employed at my university, no remuneration is expected for the blog (it is hard to imagine how often the question about this point, with a giggle or demurely, has been asked since 2006!), and etymology is only one of the many things that occupy me. Yet over the years I too have received hundreds of letters and seen numerous comments by friendly or irascible correspondents. The readership of this blog stays at about 500 people (on an average), but a few posts attracted several thousand. I have no doubt that enough people follow my writings, because as soon as I make a mistake, I am immediately taken to task.

I have received all kinds of questions and requests. Six-graders asked me to write their papers for them, which I never did, but I have given many recommendations to serious boys and girls and especially to college students and learners from abroad. Some questions were so interesting that I devoted long posts to them, rather than relegating the answers to my traditional monthly gleanings. The queries ran the gamut from the obscene to the nearly incredible. Quite early in my career as a blogger, I was asked to explain how a blowjob got its name, and recently, a correspondent has compared English wick ~ wicked and French mèche and mèchant (the French pair has exactly the same meaning). The coincidence is unbelievable and yet fortuitous! With blowjob I was not so sure but managed to produce some sort of a response: after all, I had the nascent reputation of an Oxford etymologist to live up to.

William Safire, 1929-2009. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

William Safire, 1929-2009. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)My goal has always been to discuss only such words as pose etymological problems, while, for instance, Merriam-Webster, which has an excellent “word of the day” program, deals with all kinds of interesting nouns, adjective, and verbs; etymology is not the main focus of that program. I soon discovered that the origin of some of the best-known words (big, put, dig, bread, dear, dream, and countless others) are real etymological cruxes. Yet I tried to say something about them one could not find in popular dictionaries or on the Internet. At the outset of this enterprise, I was advised to use as few foreign words as possible and to avoid diacritics. I promised to follow this recommendation and wish I could keep that promise!

Illustrations appeared rather late. One day, I wrote about the word teetotal, and a correspondent sent us a photo of the statue of the man who started the movement. I asked my editor whether we could reproduce the photo. Yes, we could! Ever since, every essay has had between three and five illustrations, and selecting them takes a lot of time.

Now back to my heifers, as promised in the title. Twenty-five years ago, quite by chance, I looked up the etymology of heifer in a dictionary and discovered the statement: “Origin unknown.” Other dictionaries were not much more informative, and I decided to pursue the subject. Thanks to this chance episode, etymology became my profession. Since I have briefly told this story in my book Word Origins, there is no need to repeat it here, but every time I am asked about my favorite word (all word hunters have to answer this questions more than once), I always say: “Heifer.” If I had a coat of arms, I would let an image of a frisking heifer appears there against the bend sinister.

This is a heifer. It bothers etymologists more than cattle breeders. (Image by Loan via Unsplash.)

This is a heifer. It bothers etymologists more than cattle breeders. (Image by Loan via Unsplash.)Despite all my efforts, the origin of heifer remains undiscovered (that is, no consensus on it exists), to use the jargon of professional lexicographers, but some conjectures can probably be discarded as unpromising and others looked upon as reasonable. The word occurred in Old English (it first turned up in a text in the year 900), and even then it must have been partly opaque. This is strange, because we are not dealing with an animal name like calf, deer, goat, or sheep, each with numerous cognates and an unclear initial meaning. Heifer goes back to Old English heahfore, apparently, a compound (heah + fore), but this sum does not yield any meaning (to us). The competing forms (heahfru, heafre, heafare, and a few others) are, apparently, variants of heahfore.

At first sight, heahfore poses no problems: heah “high” and fore, related to faran “fare, walk, go.” Time and again, heifer has been glossed as “high-stepper.” Yet this interpretation makes no sense, for what is a high-stepper, and how does such a name fit a young cow? Old English distinguished between short and long vowels, but length was not always and not uniformly designated in medieval texts. Thus, we are invited to choose among heahfore, hēahfore, heahfōre, or even hēahfōre. Every combination yields a different sense. For example, –fore resembles Old English fear ~ fearr “bull,” but why should the name of a cow that has not yet calved have such a “counter-intuitive” reference? Middle English farrow “not in calf” (compare Scottish ferry cow “cow that is not with calf and therefore continues to give milk throughout the winter) looks a bit (just a bit) more promising. But, to repeat, why high?

Heifer has the dialectal variant heckfore, and this form may contain a clue to the word’s etymology, as was first recognized by Hensleigh Wedgwood, the main etymologist of the pre-Skeat era. Relatively few of his solutions have survived, but this one seems to have merit. I’ll skip all kinds of fanciful suggestions about the origin of heifer and write only what I think is the most reasonable approach to it. (If someone is interested in more details, consult my book An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction.) The most ancient form of heahfore was probably hægfore. Hæg– must have meant “enclosure.” Compare Dutch hokkeling “heifer,” from hoc “pen.” Young cows were kept in enclosures, to protect them from full-grown bulls. The second element –fore is less clear, but it seems to have existed as a suffix of a few animal names (the same element probably occurs in fieldfare, which has often been interpreted as “field walker,” a rather meaningless gloss for a bird name).

If we could ask him about the origin of our word! (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

If we could ask him about the origin of our word! (Image via Wikimedia Commons)By later phonetic change, hægfore became hehfor and heahfore (with short heah: no reference to “high”!). It probably had a doublet hecfore, in which hec– also meant “fence, gate,” with the same suffix –fore. In some dialects, heifer preserved the diphthong ei (in them, heifer rhymes with chafer). In others, the pronunciation heffer prevailed, as in Standard English. Amusingly, Modern English preserves the spelling of the first group and the pronunciation of the second.

How persuasive is this etymology? Fairly persuasive, to my mind. To be sure, the form hægfore has not been attested. But if it had surfaced in Old English texts, the etymology of heifer would have been solved three centuries ago. While dealing with this word, Wedgwood referred the mysterious animal name to the practice of cattle breeding; no one had done this before or after. Reference to the name of a bull cannot even be imagined in this case, and English farrow surfaced only in the Middle period. It could very well have existed earlier, but why should farmers have called a young cow “not in calf”? This train of thought is not very likely. Most important: the entire compound, rather than this or that part, must make sense. Finally, did the suffix I detect in heifer and fieldfare exist? Next week, I’ll say what I know about the etymology of fieldfare. Perhaps with a bird on its shoulder, my young and innocent cow will feel a bit more comfortable.

To sum up: is the origin of heifer still debatable, as stated above? No doubt, but perhaps we are now on somewhat safer ground than before. Etymologies, unlike theorems, can seldom be proved.

Featured image by Kenneth Allen (cc-by-sa/2.0)

Thirteen new French history books [reading list]

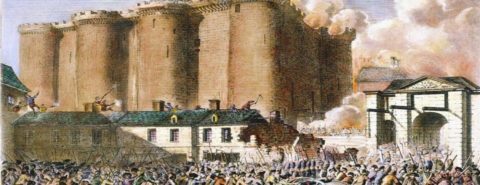

Bastille Day is a French national holiday, marking the storming of the Bastille—a military fortress and prison—on 14 July 1789, in an uprising that helped usher in the French Revolution.

In the lead up to the anniversary of Bastille day, we’re sharing some of the latest French history titles, for you to explore, share, and enjoy. We have also granted free access to selected chapters, for a limited time, for you to dip into.

1. The Death of the French Atlantic: Trade, War, and Slavery in the Age of Revolution by Alan ForrestWar, revolution, and anti-slavery were the three major forces which led to the dramatic decline of France’s Atlantic empire with the loss of her richest Caribbean colony, Saint-Domingue. Alan Forrest draws a rich portrait of France’s Atlantic communities in this tumultuous period, and the uneasy legacy of the French slave trade.

2. How the French Learned to Vote: A History of Electoral Practice in France by Malcolm CrookThis is a comprehensive history of voting in France, which offers original insights into all aspects of electoral activity that today involve most adults across the world.

3. Sex in an Old Regime City: Young Workers and Intimacy in France, 1660-1789 by Julie Hardwick

3. Sex in an Old Regime City: Young Workers and Intimacy in France, 1660-1789 by Julie HardwickSex in an Old Regime City is a major reframing of the long history of young people’s intimacy. It shows how long-running problems like out-of-wedlock pregnancy were handled very differently in Old Regime France than in more recent centuries. Abortion, infanticide, broken hearts, and conflict with parents and neighbors were key challenges of young people’s lives then as now but young couples’ efforts to deal with these challenges were supported in pragmatic, often sympathetic, ways by their communities and institutions like local courts, clergy, legal officials, and social welfare managers.

4. The Global Refuge: Huguenots in an Age of Empire by Owen StanwoodThe Global Refuge is the first global history of the Huguenots, Protestant refugees from France who scattered around the world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Inspired by visions of Eden, these religious migrants were forced to navigate a world of empires, forming colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and even South Africa and the Indian Ocean.

5. The Making of a Terrorist: Alexandre Rousselin and the French Revolution by Jeff Horn

5. The Making of a Terrorist: Alexandre Rousselin and the French Revolution by Jeff HornThis is the story of how an educated young man decided that the French Revolution was worth the use of state-sponsored violence, chose to become a terrorist to protect the republic, and spent the next five decades defending his actions.

6. The Voices of Nîmes: Women, Sex, and Marriage in Reformation Languedoc by Suzannah LipscombMost of the women who ever lived left no trace of their existence on the record of history. In this book, Suzannah Lipscomb recovers the lives and aspirations of ordinary sixteenth- and seventeenth-century French women, using rich source material to show what they thought about their lives, menfolk, friendships, faith, and sex.

7. Today Sardines Are Not for Sale: A Street Protest in Occupied Paris by Paula Schwartz

7. Today Sardines Are Not for Sale: A Street Protest in Occupied Paris by Paula SchwartzThis is the story of a food shortage demonstration organized by the underground French Communist party that took place at a central Parisian marketplace on May 31, 1942. The incident, known as the “women’s demonstration on the rue de Buci,” became a cause célèbre. In this microhistory of the event, Schwartz examines the many moving parts of an underground operation; the lives and deaths of the protesters, both women and men; and the ways in which the incident has been remembered, commemorated, or forgotten.

8. The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History by Alexander MikaberidzeAusterlitz, Wagram, Borodino, Trafalgar, Leipzig, Waterloo: these are the places most closely associated with the Napoleonic Wars. But how did this period of nearly continuous warfare affect the world beyond Europe? The immensity of the fighting waged by France against England, Prussia, Austria, and Russia, and the immediate consequences of the tremors that spread from France as a result, overshadow the profound repercussions that the Napoleonic Wars had throughout the world. In this far-ranging work, Alexander Mikaberidze argues that the Napoleonic Wars can only be fully understood with an international context in mind.

9. The Fall of Robespierre: 24 Hours in Revolutionary Paris by Colin Jones

9. The Fall of Robespierre: 24 Hours in Revolutionary Paris by Colin JonesThe day of 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794) is universally acknowledged as a major turning-point in the history of the French Revolution. Maximilien Robespierre, the most prominent member of the Committee of Public Safety, was planning to destroy one of the most dangerous plots that the Revolution had faced.

10. Pirating and Publishing: The Book Trade in the Age of Enlightenment by Robert DarntonIn the late-18th century, a group of publishers in what historian Robert Darnton calls the “Fertile Crescent”—countries located along the French border, stretching from Holland to Switzerland—pirated the works of prominent (and often banned) French writers and distributed them in France, where laws governing piracy were in flux and any notion of “copyright” very much in its infancy. Pirating and Publishing reveals how and why piracy brought the Enlightenment to every corner of France, feeding the ideas that would explode into revolution.

11. The Jacquerie of 1358: A French Peasants’ Revolt by Justine Firnhaber-Baker

11. The Jacquerie of 1358: A French Peasants’ Revolt by Justine Firnhaber-BakerThe Jacquerie of 1358 is one of the most famous and mysterious peasant uprisings of the Middle Ages. This book, the first extended study of the Jacquerie in over a century, resolves long-standing controversies about whether the revolt was just an irrational explosion of peasant hatred or simply an extension of the Parisian revolt.

12. Libertines and the Law: Subversive Authors and Criminal Justice in Early Seventeenth-Century France by Adam HorsleyLibertines and the Law examines the legal and rhetorical tactics employed in the infamous trials of three subversive authors: Giulio Cesare Vanini, Jean Fontanier and Théophile de Viau. Their trials are contextualised with a detailed conceptual history of libertinism, as well as an exploration of literary censorship and the mechanics of the criminal justice system in early Bourbon France.

13. Dead Men Telling Tales: Napoleonic War Veterans and the Military Memoir Industry, 1808-1914 by Matilda Greig

13. Dead Men Telling Tales: Napoleonic War Veterans and the Military Memoir Industry, 1808-1914 by Matilda GreigDead Men Telling Tales is an original account of the lasting cultural impact made by the autobiographies of Napoleonic soldiers over the course of the nineteenth century.

Featured image: “French Revolution,” via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.5)

June 14, 2021

Should we be worried about robots taking our jobs? The answer depends on labor market institutions

Do new technologies, such as robots, destroy jobs and cause mass unemployment? Many current and past commentators have forcefully made this point in the public debate, but new research published in the Journal of the European Economic Association suggests that “technological mass unemployment” is indeed not something we should worry about.

Instead, our research documents the subtle shifts in the German labor market brought about by industrial robots, and highlights the crucial importance of functioning labor market institutions for coping with the challenges of technology-driven industrial change.

Starting in the 1990s, robots entered German manufacturing. Quite obviously, this has led to displacements of tasks. Many production steps previously carried out by humans, such as the assembly of cars, were now performed by robots. Yet, our key finding in the paper is that, firms did not fire those workers who were no longer needed. Instead, they retained and retrained (most of) them, and the majority actually ended up performing new, more complex, and ultimately better paid jobs.

In other words, the same worker who used to bolt cars was turned into a maintenance, software, marketing person. To be sure, firms could have fired the old car screwers and looked for younger workers to fill the new jobs. But German manufacturing firms decided differently, and went for “firm-specific human capital.”

Was that voluntarily? Sure, but with a twist. We find evidence that the ret(r)aining strategy was chosen more often in regions with higher density of union members. That probably reflects some sort of deal between management and works councils, who play an important role within the German system of industrial relations.

Ultimately, the deal was such that firms hung on to their incumbent workers, but in return unions promised to remain modest when it comes to future wage demands. This stabilized jobs for incumbents.

At the end, Germany has digested the rise of the robots much better than the United States, despite the fact that Germany (and also German manufacturing) is much more robotized than the US. In a related paper, Daron Acemoglu and Pasqual Restrepo find that robots caused severe job and wage losses in the American “hire&fire” labor market. Thus, in comparison, the corporatist German model seems to have performed pretty well when it comes to digesting this technological shock.

Further positive news is what happened to the young generation in Germany in response to the robots. Since firms mostly went for the ret(r)aining of old incumbents, it meant that fewer new jobs were created for young job market entrants in the manufacturing sector.

This meant that young entrants had to start their careers elsewhere. And they did, mostly in business-related services. We even find that young people, anticipating that fewer factory jobs will be available, responded to the robot shock by investing more in education.

The unlucky ones in Germany were those workers for whom the ret(r)aining strategy did not work out, possibly because they were employed in relatively weak and non-robotized firms, who missed out on productivity gains and lost market shares. But on average, we find no evidence that robots led to an overall decrease in employment or wages, i.e., on balance, the success stories in the labor market outweighed the unlucky ones.

Now, what may all of this mean for the future? Quite obviously, massive transformations are ahead in many industries, in manufacturing and beyond. No longer from robots, which are already a quiet, mature technology, but from other new digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, and from forced technological change that originates in the necessity to reduce carbon emissions.

For example, what will happen to those workers who currently produce conventional combustion engines, or parts thereof? What will happen to small cities, whose local economy depends heavily on just a few firms that happen to be highly specialized in components for combustion engines?

Quite related to the key message of our research, a recent study by Fraunhofer claims that the overall number of jobs in the new, green car industry will be roughly the same as today. But it will be very different jobs—less bolting of turbochargers, more customer-services for self-driving electric vehicles.

On a positive note, our robot paper raises the hope that German manufacturing could also manage this transformation in a similar, non-disruptive manner. For this to work, on-the-job training and education will probably be crucial elements.

Feature image by Possessed Photography via Unsplash

June 13, 2021

The rise and fall of the European Super League: when the American challenge backfires

In the long history of America’s influence on the politics of innovation in Europe, the case of the planned football Super League stands out. This is not because of the project as such, but simply because, of all the variety of responses Europe has produced when faced with the latest American novelty, none has provoked enthusiasm and rejection—above all rejection—with such extraordinary intensity, unity, and speed.

The Super League scheme is well known to have precedents going back decades in a long line of efforts to “modernise” the organisation of football up and down the Old World. What is not recognised is how closely the vision—once taken over by American entrepreneurs—found its place in a grand historical catalogue of initiatives, corporations, movements, personalities which could emanate from any corner of America, and would set out to make their mark on the world outside the US, and Europe in particular, whether the rest of the world liked it or not. Embrace, adapt, or reject it, the great new challenge might be called Hollywood or the Marshall Plan, rock ‘n’ roll or hip-hop, Über, Google, Netflix, or even the Black Lives Matter movement; in every case America’s disruptive innovations would end up providing a mainspring of change in Europe all through the 20th century and down to the present. The European Super League (ESL) proposals, and the reactions they aroused, demonstrate that this dynamic of assymetric cultural confrontation is as active as ever.

On every such occasion cultural protectionisms are invented, diplomatic deals drawn up, international laws proposed, opinion makers and intellectuals mobilised and inevitably—sooner or later—the politicians become involved: the patterns repeat themselves over and over again. In the case of the ESL it was only when the American owners of Liverpool, Manchester United, Arsenal, and AC Milan backed by the billions of J.P.Morgan, took up the original idea of the owner of Real Madrid, Florentino Perez, that the challenge emerged on the scale and of the profile of a typical American entrepreneurial threat to an established European order. And as ever, the Europeans immediately split: six English, three key Italian, and three Spanish teams instantly signed up. The French and the Germans steered clear.

The ESL was launched in public late on Sunday 18 April. It was an announcement, said the New York Times’ soccer writer, James Montague, next day, “Made in America.” He explained:

“In American sports leagues, the norm is cartel-like structures, where owners control franchises and share revenue along the way. … But it is utterly alien to how soccer operates… promotion and relegation are in European soccer’s DNA but don’t exist in U.S. sports…Why plow money into a team when one bad season could cause you to lose your seat at the top table?”

The sale of football clubs as such in Britain goes back to the creation of the Premier League as a single commercial operation in 1992. It was a classic outcome of the free-market, top-down Americanizing views of the world which rode high in the post-Thatcher-Reagan era, and were translated into pay TV by Rupert Murdoch. By 2020, 13 Premier League Clubs, and others, were foreign-owned—the Chinese alone controlling four. Yet suddenly, with the ESL project, a tipping point was reached. The proposed League would have a permanent membership with clubs turned into free-floating brands, enjoying total control over the crucial broadcasting revenues and the market in players. A vast nationalist reaction set in with quite extraordinary ferocity and speed.

Celebrated veteran footballers, such as Gary Neville and Alan Shearer, immediately gave voice to the opposition in unmistakable terms: clubs such as theirs, they said, represented a heritage rooted in decades of local working class life and loyalty; power, pride, and dignity were at stake and could not be sold off at any price to a cabal of vulture capitalists, oligarchs, Royal sheiks, and bankers, just so that these tycoons could make even more money. Seeing a populist wave of indignation arise before their eyes, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and French President Emmanuel Macron made clear their opposition in the Sunday night hours before the official announcement of the new League.

By Tuesday morning the political backlash had broadened to include even the governments of nations not touched by the ESL project. But it was Johnson’s Tuesday morning meeting with the chairmen and fan clubs of the 14 Premier League teams not involved in the ESL which, according to many in Europe, made the key difference. Here, Johnson spoke of a “legislative bomb” which his government was ready to drop on the project. By Tuesday night the project was dead in the water.

Later, Aleksander Čeferin, the head of football’s European governing body, UEFA, acknowledged that the proposal had arisen against a background of deep financial, pandemic-related, crisis for the whole sport. He called for “solidarity” not “self-interest,” and on 21 May announced a Convention on the Future of European Football, aimed at radically reforming the governance of the game in the whole of Europe.

Indeed, even when the American challenge fails to overwhelm its intended beneficiaries, such is its force that they cannot avoid dealing with its implications and its after-effects: sooner or later everyone adapts, willingly or otherwise. The next big cultural upheaval will have “Made in America” stamped all over it once more: it will arrive when the great streaming services—Netflix, Disney Channel and now Amazon-MGM and Warner Discovery, already threatening established cinema and television everywhere—decide to get into sport. Netflix alone, with its $17bn content budget and its typically American scale, dynamism, ubiquity, and “relentlessness” (a favourite Jeff Bezos word) could certainly “find ways to make streaming live sport a viable business,” wrote Alex Barker in the Financial Times in January; “Netflix could buy a league or just create one from scratch.” Even if that came about, after the ESL fiasco it would most certainly not feature a European league of football teams. In one very special case the soft power of tradition, loyalty, identity, and solidarity had won out spectacularly over the hard power of the billionaires and all their cash.

Featured image by Jack Monach via Unsplash

June 12, 2021

Not only food and drinks: how EU (and UK) law could also protect handicrafts

The Agreement on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs Agreement)—the most important international agreement on Intellectual Property—defines, at article 22, the concept of Geographical Indication (GI) as follows:

“indications which identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.”

Why is it then that the “Kashmir Pashmina” is a protected GI in India while Harris Tweed-cloth is not an EU/UK GI? The answer is that the EU GI Quality Schemes protect only four classes of products:

agricultural products and foodstuffswinesaromatised winesspirits.The UK, which after Brexit has basically copy-pasted the EU model, does the same. Are you puzzled because you believe that jewels, musical instruments, ceramics, artistic glass, furniture, marble, stones, and other non-agricultural products should not be treated differently from the products mentioned earlier? You are absolutely right. Indeed, the EU, and now the UK, are the only two jurisdictions in the world—at least among those I know—that, despite having a registration-based sui generis GI regime in place, protect only a specific selection of products. As a lawyer, I am used to exploring the rationale behind legal rules. Yet, after years of research, I am convinced that there is little to no argument that can justify this bizarre setup.

There is the history of sui generis GIs, of course. More than a century ago, French winemakers were looking for a new way to protect their products from adulteration and counterfeiting while, at the same time, ensuring origin. They—and their representatives in the Parliament—came up with an idea: a system that can combine law and agronomy. This led to the Appellation d’Origine (Appellation of Origin, AO), a system that protects products strongly linked to the specific physical and environmental peculiarities of a place, including the relevant local know-how. The AO is the grandmother of the EU Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), that is the red circle that you can see on the packaging of Parmigiano Reggiano PDO or Prosciutto di Parma PDO whenever you enter a supermarket.

The idea of GIs as a tool to protect products that, like vines, exclusively grow from the soil is history, however. Indeed, the French Parliament discovered how simplistic this view is in 1925, when it discussed how to protect Roquefort cheese. Is it possible to protect it as an AO or can only a collective mark do the job? Well, today Roquefort is a successful PDO and I can assure you that Parmigiano Reggiano does not grow from the soil. So now you know how the discussion in the French Parliament ended.

There is more. Today, most EU GIs are registered as Protected Geographical Indications (PGI). This is a quality scheme whose definition is similar to that of the TRIPs Agreement. In particular, a PGI can protect goods that are related to their place of origin not only because their quality, but also because their reputation or any other relevant linking factor is determined by the features of the designated area. Moreover, unlike PDOs, which must be made from raw materials entirely sourced from the designated areas, PGIs allow more flexibility as to their origin.

These combined elements, reputational link and flexibility in the sourcing of the raw materials, make PGI applicable to non-agricultural products. Is the reputation, history, and relevant know-how of Harris Tweed-cloth specifically linked to the UK or specific areas of it? Yes. Is it possible to codify a set of rules for its production, including specific indications concerning the sourcing of raw materials? This was done long ago. Therefore, this product could become a PGI, if the quality schemes were extended to non-agricultural products. Is this theory? Not really. In fact, something similar already happens in countries like India that protects more handcrafts than food or drinks. Also, PDO could play a role, for instance for protecting marbles and stones.

In the EU, the protection of non-agricultural GIs has been a very complex issue with plenty of stop-and-go over the last fifteen years or so. Recently, however, the EU Commission has started a new round of public consultations on this topic and, in parallel, it has launched specific research projects to assess the viability of a new reform in this area. As a scholar who is currently involved in this process, I believe that the time is ripe and that this gap in the EU sui generis GI law will be filled in the near future. I believe that the UK can and should do the same.

Featured image by Timo Wielink via Unsplash

June 11, 2021

Songs with words: choosing and interpreting texts for choral composition

Like many aspects of choral composition, choosing the words is a combination of practical and creative considerations. If you want your music to be performed (and most composers do!), thinking about who might sing the words, and on what occasion, is as important as their inspirational qualities.

To date, most of my choral music is sacred, setting words that are chosen because they are suited for liturgical use. The Bible, works of religious poets, and collections of Christmas and Eastertide poems and carols have provided rich sources of lyrics. Looking at the choral output of other composers has led to some interesting poetic discoveries, for example Edward Elgar’s setting of Thomas Toke Lynch’s How calmly the evening, whilst the poet Alice Meynell was recommended by a friend working on Victorian literature. The gentle tone of her poem Unto us a son is given (“Given, not lent”) especially appealed.

It is hard to define what makes a text attractive, and, of course, this is probably different for every composer. But there are some texts which have received numerous musical settings, such as Drop, drop, slow tears by the seventeenth-century poet Phineas Fletcher. The expressive words of redemption fit well in the Lenten liturgy, and their character and imagery, in particular the dropping tears, invite musical illustration. The falling thirds at the opening of William Walton’s setting, for example, immediately evoke teardrops. Popular, too, is George Herbert’s The Call (“Come, my way, my truth, my life”). A versatile text which lends itself to a variety of occasions, the emotion is, strikingly, expressed almost entirely in monosyllables, imparting powerful simplicity and directness. Sometimes it may simply be the sound of the words that captivates, as in this excerpt from John Milton’s On the morning of Christ’s Nativity. The gentle alliteration is music itself:

“The winds with wonder whist,

Smoothly the waters kissed,

Whispering new joys to the mild Ocean…..”

Having found words that appeal, practically and creatively, my goal is to write music which illustrates and enhances the words, and is also musically coherent. There may be large-scale structural decisions, such as whether to replicate a strophic structure, or to reprise parts of the text, either in the interests of the musical form, or to give them particular stress. At a more localized level, the meaning and emotion of individual words might be depicted by melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic means. The interest is in deciding what the emphasis and interpretation shall be.

The well-known words of the Magnificat provide plenty of opportunities for such contemplation. Their nature (images of motion such as “scattered,” “put down,” and “exalted,” which often attract an appropriate musical illustration), and a knowledge of how other composers have responded to them, make the question ‘What is my response to the Magnificat?’ particularly pertinent. Shall I scatter the proud in a musical flourish? Are the rich to be “sent away” in musical emptiness, in descending lines and a thinning texture? Perhaps this could rather be a moment of exultation, focusing not on the literal meaning of the words but on the triumph of justice?

Looking for a text suitable for Evensong, I found William Romanis’ Round me falls the night by the simple strategy of perusing the “Evening” section of a hymn book. It was immediately appealing to me, and a musical idea came quite quickly. This is not always the case! The opportunity for intense quiet in a “whisper,” in “softly speaking,” and “Earthly sounds are none” contrasts with the potency of “Arms so strong to clasp and hold me.” Soft dynamics and low pitches contrast with fortissimo and the highest note of the piece. The light of the Saviour shines through the dark of the night, with a recurring juxtaposition of Db major and A major colouring the work. And it is the plea for the Saviour to keep watch through the night which becomes my focus. His presence is realized musically with repetitions of the phrase “I am near,” and it is with this that the work concludes.

Occasionally I have written my own words, finding that a musical and verbal idea come simultaneously. But generally, I prefer not to start with a blank canvas! Indeed, it is working with another creative form, with a seed from which the compositional idea may grow, which is one of the pleasures of writing choral music.

Feature image by enterlinedesign

June 10, 2021

Archaeology, architecture, and “Romanizing” Athens

The question of whether Athens was a Greek or Roman city seems straightforward, but among scholars there is some debate. While initially, and still geographically, a Greek city, the influence of the Roman Empire on Athens’ architecture, beginning in the first century BC with Pompey the Great, has led some scholars to classify it, architecturally, as a Roman provincial city. Pompey’s donation of fifty talents in 62BC was said to have financed a “bazaar” to display goods in the Piraeus (the harbor and center of economic activity) and perhaps the 12-meter tall Tower of the Winds (now restored), which was a horologion (timepiece) and, arguably, the world’s first meteorological station. Julius Caesar gave another fifty talents, which saw work begin on the Roman Agora, a project finished in the Augustan era thanks to yet another monetary donation, this time from Augustus himself.

This Roman Agora was nowhere near as extensive as the Athenian one, but its ruins show it was impressive, with a monumental gateway at its entrance (still standing today). Augustus went further though. He commissioned a temple of the goddess Roma and himself in front of the Parthenon on the Acropolis, with statues of himself (and perhaps other members of the imperial family) as well as the goddess Roma, and most likely housing the imperial cult. Later emperors followed suit. Claudius likely funded a marble stairway to the Propylaea of the Acropolis, and in Nero’s reign the theater of Dionysus was rebuilt.

It was not only rulers who built in Athens. Agrippa (Augustus’ son-in-law and righthand man) added a massive Odeum (theater), able to seat one thousand people, in the old Athenian Agora, which dwarfed all the other buildings around it. At some point in Trajan’s reign a certain Titus Flavius Pantaenus built what is often called a library in the Athenian Agora, though it was a grander monument than just a library as it included outer Stoas and a peristyle (an open-colonnade area).

But it was Hadrian who embarked on the most ambitious building program, which outdid that of Augustus and even Pericles in the fifth century or Lycurgus in the fourth. Hadrian had made Athens the cultural center of the Roman Empire by creating a league of Greek cities of the east with Athens at its center, called the Panhellenion. He wanted to beautify the city as befitted its new status. Thanks to him the massive temple of Olympian Zeus was completed (whose giant columns today rear to the sky); a temple of Hera and Zeus Panhellenius was built; as was a splendid library (with 100 columns) that also included gardens and colonnades; a gymnasium; and an aqueduct, to name but a few.

The archaeological remains of these buildings testify to their size and design and add to the notion that Athens had been turned into a provincial city. The new agora, for example, had some Greek architectural designs, but there was no mistaking Roman influence, such as the enclosed large marble-paved square with shops and halls on all four sides, and the later addition of a statue of Lucius Caesar atop its gate effectively turned it into a Roman triumphal arch. Agrippa’s Odeum also had Greek architectural elements to it (a Corinthian façade and capitals), but it was based on a smaller theater at Pompeii. And Hadrian’s library was probably modeled on the temple of Peace at Rome, with its library, art gallery, and garden. Reflective of these physical changes—and surely supporting the notion of the Romanizing of Athens—is the famous Arch of Hadrian, which the Athenians erected to him as a thanks offering in AD 132 (and still standing). It bore two inscriptions, one of which seems to speak volumes: “This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus” (the mythical founder of Athens).

There is no doubt Athens was physically changing. But that does not mean the city was being completely Romanized—the archaeological and architectural evidence is misleading and must be considered alongside the other anthropological knowledge available. Athens sprawled out quite a distance as it was the largest city in Greece, and it had monuments all over it—the vast majority stretching back to the classical era. Even the extensive building programs of Augustus and Hadrian did not suddenly transform the city skyline into a Roman one. The circular temple of the goddess Roma and Augustus on the Acropolis was only about eight meters in diameter and nine high, but, standing in front of the Parthenon as it did, it would have been dwarfed by that great temple to Athena. The sheer size of the Roman Odeum made its Roman presence impossible to miss, but it did not take up the entire Agora, nor did it put an end to people going there to do business, gather and talk about life and current affairs (as they had for centuries)—and appreciate all the Greek monuments there.

From the latter half of the first century BC increasing Roman involvement in Athens was evident in the numbers of Romans visiting, studying, and living there, and then the building activities. Rome impacted Athens for certain but did not cause the city to lose its “Greekness” and become a provincial one. The extent to which Roman architecture altered Athens has been exaggerated.

We should remember that the inscription “This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus” on Hadrian’s Arch faces the direction of the temple of Olympian Zeus and reflects the focal point of Hadrian’s Panhellenion, headed by Athens. But there was also another inscription on that arch, this one facing what had been, and would always be, the citadel and sacred center of the city the Acropolis; this inscription (only a few feet from its “pro-Roman counterpart”) proudly proclaimed it to all: “This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus.”

Featured image by Josiah Lewis via Pexels

June 9, 2021

Monthly gleanings for May 2021: yesterday, tomorrow, and time concepts

A few private letters and comments on my post “The Future in the Past” (17 March 2021) allow me to return to it. To begin with, I of course know The Beatles’ song about YESTER (it would have been hard to grow up when I did and not to be exposed to their repertoire). Other than that, I cannot refrain from quoting Rainer Maria Rilke’s line: “Vergangenheit steht noch bevor (“The past is still ahead of us”).

It is amazing how pregnant poets’ observations sometimes are! Rilke hardly knew anything about the world view of the ancient Babylonians. Yet those would have found Rilke’s statement trivial. As far as one can judge, the Sumerians and Babylonians saw the future behind and the past in front of them. Perhaps they thought so because the past was synonymous with good, reliable, proper, and sacral things. This conclusion, which I found in the book Imagines Mundi (Moscow 2013, p. 127: A. V. Podosinov, with reference to I. S. Klochkov, p. 127), will sound familiar to those who have read my April gleanings, because the Old Testament view of time was roughly the same.

Podosinov drew the expected conclusion that the entire Near East shared similar concepts of time. Very much in harmony with the view of the past and the future as it is presented in Old Russian chronicles (which I mentioned in the post), he reproduced an illustration from Klochkov’s book: the diagonal time line shows the movement up (!) from our descendants to our ancestors.

Every historical description depends on the attitude of the narrator, and ancient narrators lived at an epoch in which they looked on themselves as part of the picture they drew. Chroniclers and biographers of the past began their description with the most ancient events. The end became the beginning of the tale, and the view of what was close and what was remote was reversed. Today, when historians have pried themselves from the picture they draw, this reversal is no longer possible. A good deal of Klochkov and Hebrew scholars’ conclusions depends on the etymological analysis of the words for “in front of,” “behind,” and some others. History and etymology are inseparable. Welcome to the past, good, reliable, and sacral. It stares us in the eyes.

Forward to the past! (Image by Heidi Fin via Unsplash.)

Forward to the past! (Image by Heidi Fin via Unsplash.)And a last insight from Russia. One of the most profound writers of the second half of the twentieth century was Fridrikh Gorenshteyn (1932-2002; a Russian Jew, who emigrated to Germany). In his novel The Psalm, he suggests that the idea of space gave birth to philosophy and science, while the idea of time engendered religion and art. Some food for thought.

HarebrainedNow back to mundane topics. Some time ago, I posted an essay on the origin of the idiom mad as a hatter (24 January 2018). It seems that somewhere I also mentioned mad as a March hare. Ever since, I have meant to write a few lines about the adjective harebrained. It is (or was?) common to look down on animals and despise them for their stupidity. Donkeys (asses), geese, and many other sagacious “critters” have been stigmatized by overbearing humans. Are hares brainless? A curious exchange went on about the word harebrained in the periodical Notes and Queries in the first half of 1880. The doubts and replies are predictable but still worthy of resuscitating. The discussion began with the statement that the word owes its origin to the idiom as mad as a march hare. But are hares “madder” than other wild animals? Probably not. Could the original adjective be air-brained, with an h dropped in Cockney speech? This was not a good guess, for what is air-brained? Some correspondents looked down on hares with genuine contempt: “She is unstable of purpose; a straw turns her, a hair turns her again, a third time she may turn at nothing. Hunted, her course is a series of dodges and cranks.” I am not a sportsman, but dodges and cranks seem to be exactly what the doomed partner in the game of hare and hounds should do.

It was also noted that the hare had been the butt of denigrating idioms since at least the days of Ancient Greece. Proverbial sayings tend to be international, and one never knows whether some simile like the English one was coined on native soil in the sixteenth century or adapted from a foreign literary source.

If we disregard some fanciful suggestions (hare from hurry, from harry, etc.), the main question that puzzled people was: hare-brained or hair-brained? But first let me mention the little-known fact that in an English translation of Apophthegmes of Erasmus, we read: “March-hare is marsh-hare.” This is a product of folk etymology. Here is another statement from that discussion: “There was formerly a vague notion that abundance of hair denoted a lack of brains, and from this idea arose a proverb, ‘Bush natural, more hair than wit’.” Proverbs on the theme “long hair, short wit” are indeed common. Much to the credit of our old lexicographers, they did not fall into any of those traps, spelled the word correctly and let the proverbial hare remain intact. To celebrate the animal, we posted a field of harebells as the header to this post. Whether hares are particularly fond of harebells is a moot question.

A perilous game for the hare. (Image by Thomas Rowlandson via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.) A wicked Anglo-French parallel

A perilous game for the hare. (Image by Thomas Rowlandson via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.) A wicked Anglo-French parallelI mislaid this letter and apologize to our correspondent for not answering it several months ago. In English, we have wick and wicked, and in French, mèche “wick” and mèchant “wicked.” Is this coincidence fortuitous? Yes. Mèche appeared as a hybrid of two words: popular Latin micca “wick” and muccus “mucus, snot.” Classical Latin myxa “wick” was a borrowing from Greek and coexisted with mūcus “mucus.” The meanings “snot” and “wick” are not incompatible: think of a guttering candle. Mèchant, as is clear from the suffix –ant, is an old present participle that consisted of the prefix with negative semantics mes– (as in mesalliance) and a verb meaning “to fall.” English wick is an ancient word of unclear origin, even though its cognates exist in Dutch (wiecke) and German (Wieche). The root of wicked is wicca “wizard” (witch has the same root). The surprising parallelism is, as I said, fortuitous.

Stooge A wick is not wicked. (Image by BBC Creative via Unsplash.)

A wick is not wicked. (Image by BBC Creative via Unsplash.)Last week, I mentioned the word stooge. Its origin is unknown and may remain such for all eternity, but the noun appears to be sound-symbolic. No native word rhymes with it (and in general, nothing except for –fuge, as in subterfuge, and huge provides a rhyme). Yet Dickens called his famous killjoy and miser Scrooge. Of course, we hear the root screw in the name. But is it possible that in the nineteenth century, –ooge was a pseudo-suffix used in slang to denigrate people? If so, then half of the etymology will be discovered. Perhaps somebody will respond.

We split, split, split“Lynx are about the size of bobcats, with big feet that act like snowshoes allowing them to easily walk over deep snowdrifts” (= to walk easily). “The… vote sent the one-week bill to the Senate, where it’s expected to easily pass before a deadline of…” (= to pass easily). Lynx and bills tend to pass easily, rather than to easily pass. “He hopes to still continue his work (= still hopes). “He and the other two crew members were declared missing and presumed dead, only to later be rescued from… (only to be rescued later/ only later to be rescued). Isn’t there a vaccine to rescue us from this virus?

A final noteOn 24 March 2021, I posted the first of three essays on trash, rubbish, and garbage. Several day ago, I was delighted to read a newspaper article with the heading “Critics say E…’s plan for park trash is garbage.” Whether the plan will be trashed remain unknown.

Please write letters and leave comments!

Feature image by Chris Gunns via Geograph (cc-by-sa/2.0)

June 8, 2021

New York City and the path to neoliberalism in the 1970s [timeline]

In the late twentieth century, New York City transformed into a model of neoliberal governance. While at mid-century, city government maintained the most robust social democratic program in the country, by the late twentieth century, much of this program had been curtailed and the private sector and market had gained a far greater role in providing services previously maintained by government.

Beginning in the late 1960s, New York entered an economic crisis that disrupted long-standing assumptions about what city government could provide. In response, residents embraced an ethos of private volunteerism and, eventually, of partnership with private business in order to save their communities from neglect. Local liberal and Democratic officials came to see these alliances not as temporary stopgaps, but as models for how to sustain public services in leaner times. These initiatives forged New York’s path toward a greater dependence on the private sector and market to address the city’s problems.

In the timeline below, I highlight key examples of how New Yorkers in the 1970s responded to alarming conditions affecting their parks, streets, and neighborhoods. As these kinds of initiatives gained support from local liberal and Democratic officials, they helped to shift major responsibilities of city governance into the private sector, market, and citizens themselves.

Where are the Martian scientists?

When Perseverance, the Mars rover, landed on the Red Planet on 18 February 2021, I found myself asking a familiar question: where are the Martian scientists?

I’m joking of course, but the idea of Martian scientists—Martian anthropologists, Martian linguists, Martian sociologists, Martian biologists, even Martian philosophers—has become a rhetorical staple. When a writer wants to invoke the perspective of the unbiased observer, a Martian is just around the corner. The trope scientist has been made famous by Noam Chomsky, who puts it this way in 1977 book Language and Responsibility:

Let’s consider this question of human uniqueness. Imagine a Martian scientist who studies human beings from the outside, without any prejudice.

The Martian scientist shows up again in Language and Problems of Knowledge, where he is given a name (John M.) and appears for several pages puzzling out the formation of questions in Spanish to show that our intuitive knowledge of things can get in the way of discovery. And in his political writing, Chomsky even has an essay called “The Journalist from Mars.”

Of course, Chomsky is not the only one to invoke Martians: Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, Saul Kripke, Hilary Putnam, and others do it as well. Oliver Sacks even titled a 1995 book An Anthropologist on Mars, a reference to Temple Grandin, who described herself that way.

Before scholars and writers adopted the Martian so thoroughly, there was television’s “My Favorite Martian,” the 1960s comedy in which actor Ray Walston played a Martian anthropologist who crashes on earth and is discovered by a journalist. The journalist, played by Bill Bixby, takes him as his Uncle Martin to prevent a panic. The hundred or so episodes combined humor with outsider commentary on life and paved the way for many other quirky television extraterrestrials.

But the Martian trope goes much further back. Before Noam Chomsky, linguist Robert A. Hall writes this in his book 1950 Leave Your Language Alone!:

When we want to imagine how things would seem to somebody who could look at us in a wholly objective, scientific way, we often put our reasoning in terms of a “man from Mars” coming to observe the earth and its inhabitants, living among men and studying their existence dispassionately and in its entirety.

Eugene Nida’s 1941 book Morphology, stressing the need for objectivity explains, “It would be excellent if [the descriptive analyst] could adopt a completely man-from-Mars attitude toward any language he analyzes and describes,” and a 1936 book on The Future of Taboo opened with “Last summer a distinguished Martian anthropologist visited the British Isles and permitted the B.B.C. and its myriads of licensees to listen in to the impressions which he broadcast week by week to Mars.”

On it goes: a 1908 book refers to “a Martian sociologist, viewing mankind with impartial survey from China to Peru.” The Martian trope was already so widely recognized in the early twentieth century that we find references to “the proverbial Martian,” “the proverbial inhabitant from Mars,” “the proverbial visitor from Mars Society,” and more.

I haven’t yet found a first Martian visitor, but fascination with the Red Planet seems to have especially peaked after the discovery by Giovanni Schiaparelli of channels on Mars in 1877. Schiaparelli called them canali, which was (mis)translated into English as “canals” instead of “channels.” In 1894, American astronomer Percival Lowell, mapped hundreds of them and proposed that they were built by Martians.

Lowell published three books on Mars and influenced a burgeoning market for Martian fiction: H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds depicting a Martian invasion, Mary Ann Moore-Bentley’s A Woman of Mars, which presented Mars as a feminist utopia, and Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars, which gave us green-skinned Martians.

By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, newspapers were already joking about Martian scientists. A squib in the Philadelphia Ledger asked: “Can’t help but wonder if Martian Scientists are reporting to each other as to progress on the Panama Canal.”

Featured image: “Hellas Chaos” on Mars by ESA/DLR/FU Berlin. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers