Oxford University Press's Blog, page 101

July 27, 2021

The neuroscience of human consciousness [podcast]

How can the study of the human brain help us unravel the mysteries of life? Going a step further, how can having a better understanding of the brain help us to combat debilitating diseases or treat mental illnesses? On this episode of The Oxford Comment, we focused on human consciousness and how studying the neurological basis for human cognition can lead not only to better health but a better understanding of human culture, language, and society as well.

We are joined today by Dr John Parrington, author of the newly published book Mind Shift: How Culture Transformed the Human Brain, and Professor Anil Seth, Editor-in-Chief of the Open Access journal Neuroscience of Consciousness, to learn more about the study of human consciousness and how it can help us to understand autism spectrum disorders, mental illnesses, and neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis, the focus of this year’s World Brain Day (22 July).

Check out Episode 63 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Neuroscience and Human Consciousness – Episode 63 – The Oxford CommentRecommended reading

To learn more about human consciousness, you can read a chapter from John Parrington’s recently released Mind Shift, and the articles in Neuroscience of Consciousness’ special issue on “Consciousness Science and its Theories,” currently in progress. We also suggest these past blog posts from Neuroscience of Consciousness authors that can be found on the OUPblog: “Does Consciousness Have a Function?” and “Can You Learn While You Sleep?”

In addition, you can also listen to John Parrington’s guest spot on The Oxford Comment’s spin-off series, The Side Comment, from April of this year, and watch this video of Anil Seth from the launch of the Neuroscience of Consciousness journal back in 2015. Seth’s new book, Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, is also set for release in September.

Featured image: Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash.

It’s time to use software-as-medicine to help an injured brain

The history of war is deeply associated with the history of brain injury—and its treatment. In ancient Greece, Hippocrates studied battlefield head injuries and taught that craniotomy could help alleviate the consequences of these terrible wounds. World War I introduced large-scale explosives to the battlefield, leading to a plague of traumatic brain injuries—which in turn led to the development of cognitive rehabilitation strategies still in use today.

Our recent wars have introduced a new kind of brain injury. An all-too-common experience is a servicemember experiencing persistent brain injury from multiple blast exposures or concussive events—the “signature injury” of the Iraq/Afghanistan wars. These initially were not viewed as having potentially life-altering consequences. Even their classification as mild Traumatic Brain Injuries (“mTBIs”) suggested they were of little consequence. But, for some people, the cognitive deficits from such blows are persistent and servicemembers exposed to multiple incidents have elevated risk of long-term consequences, including cognitive impairment.

Such cognitive impairment can be a significant hurdle for servicemembers re-entering civilian life or returning for another tour of duty. The Department of Defense knew this new kind of brain injury needed new kinds of treatments and asked (using the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP)) for new treatments to be put to the test.

At Posit Science, we had developed a new type of brain training program, based on the science of brain plasticity and the discovery that intensive, adaptive, computerized training—targeting sensory speed and accuracy—can rewire the brain to improve cognitive function. This program improved cognitive performance and real-world function in older adults in numerous studies. The cognitive issues associated with mTBI looked broadly similar to those associated with aging—despite their different root causes. Could the same brain exercises designed to address cognitive impairment in older adults help servicemembers?

Such brain training had the potential to offer two significant innovations for treating cognitive impairment—a bottom-up approach to rewire the brain and computerized delivery to reach more people. Much of traditional cognitive rehabilitation is “top-down”—teaching helpful compensatory skills (like keeping a memory notebook or using a calendar). Brain-plasticity-based cognitive training is “bottom-up”—designed to improve the building blocks of cognitive function (like speed, attention, and working memory). Most traditional cognitive rehabilitation requires in-person administration. Excellent services may be available to servicemembers who can go to a VA medical center or military hospital several times a week but it’s difficult to deliver that standard of care to everyone in need. Plasticity-based brain training can be done on a computer or mobile device—anywhere. It can be remotely monitored and supervised via telehealth, significantly expanding the patient population that can be served.

With funding from the CDMRP and a multisite collaboration across leading VA medical centers and military hospitals, we could find out if this plasticity-based computerized approach worked.

The BRAVE trial enrolled participants with current cognitive impairment and a history of mTBI. Most were servicemembers and veterans. On average, participants had cognitive deficits that had persisted for seven years since their most recent mTBI. The group was randomized into a treatment group, who used the game-like brain training program, and an active control group, who used ordinary computer games.

Both groups were asked to train for the same amount—one hour per day, five days per week, for three months. People trained at home, using their own computers and internet. Clinicians provided remote coaching for both groups by phone—every week, a clinician would review a patient’s usage and provide technical support and encouragement.

We saw the brain training program significantly improved overall cognitive function—as measured by a composite of memory and executive function—as compared to the active control. In fact, the improvement in the brain training group was equivalent to moving from the middle of the pack to the top quartile of performance, while there was essentially no improvement in the active control group.

This tells us something pretty interesting: cognitive improvement, even in people with a long history of deficits from mTBI, is possible. But it’s not delivered by any kind of cognitive stimulation: it requires a specific type of training. Training with crossword puzzles and Boggle, which are cognitively demanding tasks, did not improve overall cognitive performance. But training to improve the speed and accuracy of information processing through the brain did improve cognitive performance.

The BRAVE trial is an important step forward in understanding how to help servicemembers suffering long-term consequences of mTBIs. There has been quite a lot of scientific progress in the field since the Department of Defense first recognized the problem. What’s needed now is clinical progress in the field.

I’ve visited cognitive rehabilitation clinics at VA medical centers and military hospitals. What I see over and over again is talented clinicians who are committed to helping patients but who do not have the resources (staff, space, computers) to put the evidence-based practices—validated with research grants—into practice. It’s time for the federal government to act on what has been learned from these trials to ensure that every single servicemember and veteran—regardless of location or income—has access to the best technology to treat their war injuries.

Featured image by geralt via Pixabay .

July 24, 2021

Are UK public libraries heading in a new direction?

Since early 2020, we’ve seen the phrase “the new normal” used everywhere to describe every aspect of our lives post-coronavirus. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 had a huge impact on the library sector with closures happening globally, equally seen among institutional libraries as well as public libraries. As a result, we’ve seen new initiatives being adopted and revised strategies implemented. But how will these affect how we portray UK public libraries going forward? Are they heading in a new direction to successfully serve the community?

In this blog post, Karen Walker, Team Leader at Orkney Library and Archive, Katie Warriner, Information Services Librarian at Calderdale Libraries, and Trisha Ward, Director of Library Services, Libraries NI, discuss changes they have noted during the pandemic and shed light on what purpose, they believe, UK public libraries will serve for the community in “the new normal.”

How has the pandemic changed libraries’ core services?As libraries begin to reopen at their full capacity, some of the initiatives that were specifically undertaken to support customers during the pandemic are now to be kept on permanently and offered as part of their core service. That is the case for the Request and Collect feature at Orkney Library, which has proved popular during lockdown and now will be a permanent addition. Similarly, during lockdown, Libraries NI “provided, out of necessity, services such as Book and Collect, (a service where staff select books for customers to collect at the library door) which have been very popular and exploit the stock knowledge of staff”. With these new book lending services becoming available, reading habits have changed considerably. “At the start of the first lockdown, the main option was e-reading/listening and we found that our Home Library Service expanded too,” says Walker, and Ward states that Libraries NI also saw a large move to online and many new “virtual members,” which they anticipate to continue going forward. “Anecdotally lots more people were reading but they read different genres and in different ways including a growth in eAudiobooks. Obviously this is a challenge for a public library service because of the higher cost and different licensing models with eBooks. We also invested in eNewspapers which has proved popular,” she adds.

How has the adoption of technological tools benefitted libraries?At the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the benefits of technology became more apparent than ever before. Possibly every sector took advantage of it to deliver services as well as host events and meetings to include people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to participate. Ward mentions that “online programming, especially in relation to quite specialist areas of interest, such as heritage talks, were a new format of service delivery. We had large audiences for events, sometimes from overseas which would not have been possible previously.” Additionally, Walker admits that “widespread use of Microsoft Teams to hold meetings online anywhere in the world has made contacting colleagues throughout easier and contributed to recovery plans being implemented.” However, apart from the practicality of communication platforms such as Microsoft Teams or Zoom, social media has also played a critical role in bringing communities together during lockdowns. Libraries NI used Facebook for programme delivery, such as Storytime and Rhythm and Rhyme; Orkney Library put more activities online like Lego challenges, online jigsaws, Bookbug, or Haiku challenge; Calderdale Libraries used their very active social media channels for promoting their resources, service updates, and the Children’s Library Service posted regular activities. Additionally, Calderdale Libraries “produced several films on aspects of local history and this is something that we would like to continue after lockdown, staff time permitting.”

How will librarians’ responsibilities change as a result of the pandemic?“We see libraries as social hubs which contribute to societal wellbeing. This builds on the sense of renewed community spirit which many communities experienced during the pandemic.”

With this in mind, will UK public librarians have new responsibilities post-coronavirus? Warriner suspects that council cutbacks, worsened by the pandemic, will force changes on library services; but personally speaking, she believes that COVID-19 will not alter the role of public librarians. On the other hand, Walker suspects that going forward, librarians “will have to observe Scottish Government Public Library guidance, carry out more regular risk assessments and ensure buildings are ventilated and possibly cap numbers within the building.” Additionally, from Libraries NI’s point of view, Ward suspects that longer term, the move to more agile working practices will continue with, for example, increased use of video conferencing for meetings and service delivery. In terms of libraries’ priorities changing going forward, there will be more emphasis on eServices and deliveries of books boxes from Orkney Libraries and Archives, whereas for Libraries NI the pandemic “raised the level of priority which libraries in Northern Ireland gives to programmes which support positive mental health including those activities which address loneliness. However, Libraries NI has always had a focus on literacy, health, and digital inclusion, which have become even more important,” says Ward.

What does the “new normal” look like for UK public libraries?So, what does the “new normal” look like for public libraries in the UK? Will they now serve a different purpose for the community? Is there a new direction they’re heading towards? Calderdale Libraries, Orkney Library, and Libraries NI agree that no, there is not real change in terms of public libraries’ role in the future. “Our purpose is still to be a community space for all,” says Walker. Warriner assures that Calderdale Libraries “will continue to offer services that include and help all residents. The pandemic has only serviced to highlight disparities and it is more important than ever to offer educational opportunities by way of good quality and digital access in the form of PCs and assistance in using them wherever we are able to.” Ward agrees that the pandemic has highlighted the need for services they already deliver, such as online services, and the role of a library as the “third space.” “We see libraries as social hubs which contribute to societal wellbeing. This builds on the sense of renewed community spirit which many communities experienced during the pandemic and creates space to address the isolation which has resulted from the pandemic. We anticipate that the role of libraries as an anchor for high streets, replacing in some cases retail centres, is a new role. In this role, libraries will help to draw visitors to town centres, availing themselves of a range of cultural and creative activities,” Ward adds.

The coronavirus pandemic has taught us all new lessons, challenged our daily habits, and highlighted our strengths. When asked about one lesson from last year, Warriner emphasises how adaptable people are. “Vulnerable customers really needed us (we were helping to arrange food parcels and home-schooling IT equipment for some of our job club customers) and will continue to need us as we are much more than books.” Ward says that thanks to trialling many pilots during the pandemic, library staff learned to take risks in a safe way which gave them confidence to be innovative. And lastly, when asked the same question, Walker concluded, “be kind to each other.”

Featured image by Ria Puskas

July 23, 2021

Let’s raise our taxes! Infrastructure and the American character

If the infrastructure—roads, rails, water, and sewer lines—is the foundation of our economy, we are living on ruins and on borrowed time. The fragility of our infrastructure symbolizes the failure of a national ideology that has submerged public welfare under an ocean of private interests. And what Henry Adams observed while riding through ante-bellum Virginia, is true for today also: “bad roads meant bad morals.”

The 21st century inherited the 20th century’s infrastructure, whose maintenance was habitually deferred, so it’s really no wonder that our bridges need replacement and our roads need repair, along with our water and sewage lines. All material things are subject to the same laws of decay, rust, degradation, and failure, but where older buildings are often demolished and replaced by newer ones, much our infrastructure often decays unnoticed, out of sight, until a bridge or a tunnel collapses, a water main bursts, a gas line ruptures. Much of our national infrastructure, especially in the older cities, was built more than a hundred years ago, and things like cast iron water pipes, used early in the 20th century, have a lifespan of less than a hundred years.

You might be thinking: “is that my responsibility?” I believe it is. Addressing the invisible ruins of our public infrastructure must be reconceptualized in the 21st century, and this involves reframing the concept of private and public. Regarding amenities and services that are “public,” we might naturally think, “if I don’t use this thing, why should I pay for it? I pay for a meal because I have eaten it. Why should I pay for a meal that you are eating?” We saw this sentiment expressed most widely (and wildly) in the debate on the Affordable Care Act.

“Addressing the invisible ruins of our public infrastructure must be reconceptualized in the 21st century, and this involves reframing the concept of private and public.”

The problem with this sort of thinking, not sufficiently highlighted in public debate, is simple: you are not merely a private citizen. You are also a public citizen. Unless you live in solitude on an unknown deserted island, you have this dual identity.

In matters that are private (your food, clothing, shelter), you pay for what you use. You have autonomy. In matters that are public (defense, roads, water) you pay for things you may or may not use. You rely on experts, ideally, to figure out the needs. To think that you only should pay for what you personally use is to miss the whole point of what it means to live in a community, a city, a state, a nation. It is to miss the point of pooling the cost and pooling the risk of insurance policies of any kind. You can’t protest the fact that you might pay to insure your house and your auto for a lifetime and never get to use it. That’s the nature of insurance. You’ll be covered in the event of catastrophe.

Of course, repairing and rebuilding our infrastructure requires public funding, and the costs of proper maintenance—deferred for so long in so many places—are enormous. Conversely, the pool of available funding from the Federal government is wholly inadequate.(See the Congressional Research Service’s June 2020 report, R6410, Repairs and Alterations Backlog at the General Services Administration.) Some towns and cities—financially near collapse—have experimented in the last decade with privatizing water, and even sewer services, in the belief that anything private is better than public, more efficient, cheaper, less wasteful. But the results of privatizing public works have been unhappy, with restricted services and higher prices. After all, privatizing is based on the assumption that a business will make a profit, and there is little profit in public services. Privatize space travel, I would say, since traveling to the moon is not a public necessity. But not water, and not waste, and not the bridge I use daily. FEMA is often charged with temporary repairs, but the E in FEMA is for “Emergency,” and what we need is a long-term solution to this problem.

“The US taxation rate of 24% of gross domestic product is well below the average of other developed countries at 34%.”

Does this mean raising my taxes? Yes, because public works need public funding, and we are still generally under-taxed compared to other countries: the US rate of 24% of gross domestic product is well below the average of other developed countries (34%). One reason you marvel at the public spaces—parks, buildings, monuments, streets in Europe—is that France, Italy, Sweden, and others all have a revenue of more than 40% of gross domestic product. (It’s not surprising that the US ranks 15th in the international Quality of Life index.) We need massive and regular funding to sustain our failing infrastructure.

All of this goes against our habits and beliefs: we’ve been taught to believe that America is the greatest country in the world, that taxes are a nuisance, something suckers pay, and that it’s smart and even heroic to pay little or nothing. Really, it should be a badge of disgrace and dishonor, an act of social pathology, like eating all the chocolate strawberries on the dessert tray or watering your lawn during a drought; worse yet, it’s like closing the door on your neighbor during a storm, driving your speedboat by a drowning swimmer. Who would do this and boast about it?

At the heart of America’s future is the need to accept our dual citizenship—private and public—and our failure to do so may well doom us. We tend to frame our public debate in the most simplistic of terms: individualism vs. collectivism, libertarianism vs. socialism, as if they are mutually exclusive. These things are antithetical, but they are not mutually exclusive, and they are not polar choices. Every single person comprises both sides of this duality; every single person is both a private and a public citizen. If we can reframe the debate and accept our dual citizenship, we will begin to deal seriously with the ruins of our public works and the cost of fixing them.

Featured image by Giancarlo Revolledo on Unsplash

July 22, 2021

Beyond history and identity: what else can we learn from the past?

History is important to collective identity in the same way that memory is important to our sense of ourselves. It is difficult to explain who we are without reference to our past: place and date of birth, class background, education, and so on. A shared history can, by the same token, give us a shared identity—to be a Manchester United fan is to have a particular relationship to the Munich air disaster, the Busby babes, George Best, Eric Cantona, and so on.

Over the years, politicians of all parties have wanted to encourage that: to add to the pool of shared experience which knits us together as a political community. For Gordon Brown, “citizenship is not an abstract concept, or just access to a passport. I believe it is—and must be seen as—founded on shared values that define the character of our country.” While John Major hoped that ‘fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers and, as George Orwell said, ‘Old maids bicycling to holy communion through the morning mist’ and, if we get our way, Shakespeare will still be read even in school.”

But memories can be false, partial, and self-serving, and people select differently from the past in order to explain how we arrived at the present and what the present means. It also depends, of course, on who is asking. For some purposes, accounts of ourselves might ignore regional and class origin and tell instead of where we have lived, when and where we had our first kiss, or what sports we have played.

In other words, the aspects of the past that seem important vary according to the circumstances in which we reflect on it. This doesn’t mean that anything goes—I have never lived on the moon—but there is not simply one version of my past, or one version of the past, which is relevant to me. In effect we are, in part, our experiences and memories, but when we say who we are, we make choices about which memories to talk about; when we make those selections we are, in a sense, defining who we are.

That is why the current culture wars often focus on rival versions of the past—selecting events and personalities that reinforce our version of who we are and who we want to become.

There are always alternative memories to be dealt with of course, and conflict is more often about selection and interpretation than about what is “true.” When a remorseful celebrity is confronted with some embarrassment from their past, they don’t so much deny it as say that it is not a true indication of who they now are. In a similar way, no one says Britain did not have a slave trade, but some question what that tells us about who we really are and the significance we should attach to it.

It is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that in the run-up to the EU referendum and in the aftermath of Brexit, these issues of history and identity have loomed so large. But past experience is not only about identity, either individually or collectively: it also yields experience about how to get things done. We draw on our own and others’ experience when we think about what to do, and how to do it. Perhaps we could put this at the heart of our history—the history of political agency, rather than identity. After all, that is also an issue of pressing contemporary importance. Perhaps it’s time to talk about that too.

Featured image by Aleks Marinkovic via Unsplash

July 21, 2021

The decay of the art of lying, or homonyms and their kin

I have been meaning to write about homonyms for quite some time, and now this time has come. Some clarification of terms is needed. English is full of homographs, or words that are spelled the same but pronounced differently. They are the bane of a foreigner’s life: bass, bow, sow, lead, and so forth (however, not only foreigners suffer from such traps: one has to be a teacher to know how many times even college students believe that the past tense of the verb lead is also lead, like read ~ read). Then there are homophones: words like by ~ bye ~ buy; sew ~ so, two ~ too ~ to (add tutu), and so forth. They are spelled differently but sound the same. Finally, we find perfect matches: match1 (a box of matches), match2 (I am not his match), and match3, as in boxing match. The tenuous connection between match2 and match3 in our language intuition is a problem to which we’ll briefly return below. Words like match1, 2, 3 are called homonyms. As long as we are dealing with oral speech, homophones are indistinguishable from homonyms.

Some homonyms are more perfect than others. For example, ash (a tree) and ash (the residue left after burning) sound the same in the singular and in the plural. By contrast, lie (tell falsehoods) is a weak verb (lie, lied, lied), while lie (as in lie awake) is strong (lie, lay, lain); they are homonyms only in some of their forms. I will skip the niceties of classification and bypass the question whether words like love (noun) and love (verb) should be called homonyms. (Hardly so!) Here we are interested in one question only, to wit—why so many obviously different words are not distinguished in pronunciation, or, to change the focus of the enquiry, why language, constantly striving for the most economical and most perfect means of expression (or so it seems), has not done enough to get rid of those countless ambiguities.

Match girls. (Image by Maria Kirilenko via Flickr)

Match girls. (Image by Maria Kirilenko via Flickr)The answer was given long ago. In most cases, homonyms occur in non-overlapping contexts, so that misunderstanding never occurs, or the situation disambiguates the clash. Even when homonyms meet and we say that the ash tree was burned to ashes, the message remains clear. We may appreciate or wince at the play of words (I prefer the first option) but have no trouble deciphering the message. Homographs are a terrible nuisance (and this is where a moderate spelling reform might improve the situation), but homophones are the joy of wits and poets. One can lie in bed and lie to the doctor about a nonexistent illness. Some literary periods revel in this type of language. Shakespeare lived in one of them. His puns fill a volume, and not all of them are “bawdy.” In the sonnets about the woman whom he both loved and despised, we find such a couplet: “Therefore I lie with her, and she with me. / And in our faults by lies we flatter’d be” (Sonnet 138). In Old English, the two forms were quite different, namely licgan and lēogan. But phonetic change, that great leveler, gradually effaced the differences.

Let us look at some examples from a historical point of view. Even in the best popular books on the development of the vocabulary of Modern English, such as Greenough and Kittredge’s Words and Their Ways in English Speech and Bernard Groom’s A Short History of English Words, one won’t find a chapter on the rise of homonyms, though the subject is quite worthy of discussion. Why is English so full of homonyms? First, by pure chance. For example, ash (the tree name) and ash (as in sackcloth and ashes) have, from a historical point of view, nothing in common, but they were close even in Old English (æsc and æsce). When the second word lost its ending, the harm was done. Nothing is more noticeable in the history of the Germanic languages than the loss of postradical syllables. The oldest runic inscriptions have preserved very long words. Even in the fourth-century Gothic their cognates are sometimes a syllable shorter. More shrinking happened in Old English, then apocope chopped off most endings in the Middle period, and today we are left with a storehouse of monosyllables: be, come, do, put, man, child, calf, good, and the rest. The Gothic for they would have sought was the unwieldy form so-kei-de-dei-na (five syllables). We need four monosyllables to express the same idea. And of course, we keep shortening even our recent words. That is why doc “doctor” has become a homophone of dock, ad “advertisement” is indistinguishable in pronunciation from add, and Mike can freeze in front of a mike.

The musicians are bowing. They will bow later. (Image via pxhere)

The musicians are bowing. They will bow later. (Image via pxhere)Monosyllables cause the greatest trouble to etymologists. For example, take bob, as in bobbed hair, and bob “move up and down.” No one knows for sure where such short expressive verbs come from (especially such as begin with and end in the same consonant: tit, tat, gig, kick, and so forth). Are bob1 and bob2 different words or two senses of one word? After all, any impulsive movement can be described by using the syllable bob! If I say bob along! you will probably understand me, though you have never heard such a phrase. Cob is “round head; testicle; a mixture of unburned clay and straw; a short-legged riding horse,” and many more things. They are “symbolic formations”: say cob and conjure up a picture of something round, never mind what! Dictionary makers wonder whether to list them under one entry, with 1, 2, 3, etc., or separate them. Did a protoform exist that split into many fragments, or are they unrelated products of language creativity, with people constantly saying bob, bug, box, cob, pop, etc., and endowing them with the senses that suit them at the moment?

But sometimes we can follow the process of disintegration. It would probably be counterproductive to treat love (noun) and love (verb) as homonyms. But what about fall “autumn” and spring as opposed to the verbs “to fall” and “to spring”? Clearly, the fall is the time of “falling” and spring is the time of “springing,” but this connection is rather vague, and again one wonders whether today we have homonyms or different words. And remember match! An etymologist treats match1 (a perfect match) and match2 (a boxing match) as two senses of the same word but what about “naïve” speakers?

Lying in bed. (Image via piqsels)

Lying in bed. (Image via piqsels)I am returning to the verb to lie. Gothic has liugan “to lie” (that is, “to tell falsehoods”) and liugan “to marry a man” (not just “to marry”!). This incompatible pair has troubled philologists for a long time, though the great and nearly infallible Jacob Grimm offered a good explanation that covered both senses. Some people accepted his idea, but most did not. Grimm believed that in the oldest languages, homonyms should in general be analyzed with caution and that in most cases an attempt should be made to trace them to the same protomeaning. Gothic interests few of our readers, and I’ll not address the problem, the more so as I have written an article about this enigmatic pair in which I tried to defend Grimm’s idea, but to agree with Jacob Grimm, we must understand what the speakers of Old Germanic meant when they referred to lying and what the ceremony of an ancient wedding entailed.

Alas, the vocabulary of a language like Modern English is so rich and so multifaceted that Grimm’s dictum can be applied to it in exceptional cases. “In our faults we flatter’d be.”

Feature image: Chandos portrait, National Portrait Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

July 20, 2021

“Stop acting like a child”: police denial of Black childhood

On 29 January 2021, Rochester police responded to an incident involving a Black nine-year-old girl, who they were told might be suicidal. An extended police body camera video of the incident shows the agitated child, her mother, and an officer attempting to de-escalate the situation. The police detain the child by restraining her in handcuffs and placing her in the backseat of the police vehicle. Several of the nine officers who responded to the scene repeatedly threatened the child with pepper spray while detaining her. The child is shown begging the officers not to pepper spray her, crying hysterically, and repeatedly calling for her father. At one point, an officer says, “stop acting like a child,” to which she responds, “I am a child.” After the child is handcuffed and seated in the backseat of the police car, one of the police officers pepper sprays her and shuts the car door as the young girl screams inside.

As outrageous as this event was, it comports with existing psychological research conducted showing that people perceive Black children (but not White children) to be, on average, about 4.5 years older than they really are. In turn, people deny Black children traits and attributes uniquely reserved for children—namely, childhood innocence—and, in turn, treat them more severely than White children, as if they were adults. Instead of attributing childhood innocence to the behavior of Black children, police instead dehumanize Black children (implicitly associating them with apes), and the more police officers dehumanize Black children, the more frequently they use physical force against Black (but not White) children. The results of this research were so clearly demonstrated in real time by the Rochester police, who claimed to perceive an already detained and handcuffed Black, nine-year-old child to be a physical threat, in turn pepper-spraying her.

Although it is developmentally and psychologically normative for a nine-year-old to be fearful, cry, call for her father, and protest when multiple armed police officers attempt to detain her, the police in this instance instead blamed the nine-year-old for the event, attributing their use of force to her lack of cooperation. Indeed, at one point as the child begs to the officers, “Please don’t do this to me,” an officer is captured on camera telling the child, “You did it to yourself, hon.” The officers’ behavior reflects a grave lack of knowledge regarding the unique developmental and psychological behavior of children, generally. Importantly, substantial evidence reveals that Black and White children do not differ in basic psychological, emotional, and cognitive development. For instance, research shows that across all racial groups, children and adolescents (relative to adults) are disproportionately impulsive, sensation-seeking oriented, susceptible to peer influence, and prefer risk-taking with short-term over long-term potential rewards. Relatedly, Black and White youth do not differ in the extent to which they engage in various risk-taking criminal behaviors, like drunk driving and drug abuse.

Despite the absence of racial differences in basic psychological development, juvenile and criminal court decision makers consistently treat Black youth more harshly than White youth. For instance, even though self-report data reveal that White youth report more drug abuse than Black youth, Black youth are significantly more likely to be arrested for drug abuse. Moreover, even after holding constant factors like offense seriousness, Black youth (relative to White youth) are disproportionately detained, arrested, sentenced severely, transferred to adult criminal court, and treated punitively within probation. The disproportionately punitive treatment of Black relative to White youth offenders can be explained by negative racial stereotypes about recidivism potential, maturity, and culpability of Black youth, as well as dehumanization and the denial of childhood innocence of Black youth.

Notably, the Rochester police were not responding to a call involving criminal offending. Instead, they were responding to a call involving a mental health crisis—specifically, a suicidal nine-year-old child. Yet, substantial research suggests that otherwise ambiguous and developmentally normative child behavior (i.e., “loitering” or “disrespect”) is misinterpreted as “dangerous” and more frequently treated punitively with discipline when the child is Black than White. The negative downstream consequences for racial minority youth are myriad. For instance, being stereotyped by police officers causes anxiety among Black youth—anxiety that has the potential to prevent them from calling police in an emergency situation. Importantly, racial minorities who experience police brutality directly or vicariously (witnessing the abuse of others) are disproportionately likely to experience negative mental health consequences including anger, fear, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The implications of this research for the nine-year-old in Rochester are grim. To the extent that police use-of-force on an otherwise mentally healthy adult triggers mental illness, the negative mental health consequences of police-use-of-force on a suicidal nine-year-old child are likely even more serious.

As harmful as this experience of individual racism likely was for this nine-year-old, it is important to consider the impact of systemic and institutionalized racism affecting racial minority children within the justice systems. Negative experiences like these, which are disproportionately experienced by Black youth, set the stage for cascading and cumulatively negative future outcomes, occurring at each decision-point within the justice system (i.e., arrest, detainment, bail, verdicts, sentencing, probation, etc.). Understanding early experiences of racial minority youth is critical for understanding the scope of the disproportionately negative outcomes experienced by racial minority adults within the justice systems. Psychological scientists ought to continue conducting research to expose the unjust and damaging experiences of racial minority children within the legal system. Importantly, their work should not end in the lab. Instead, psychologists ought to use this research to advocate for law and policy change to end the disproportionately harmful impact of racism on the lives of children.

July 19, 2021

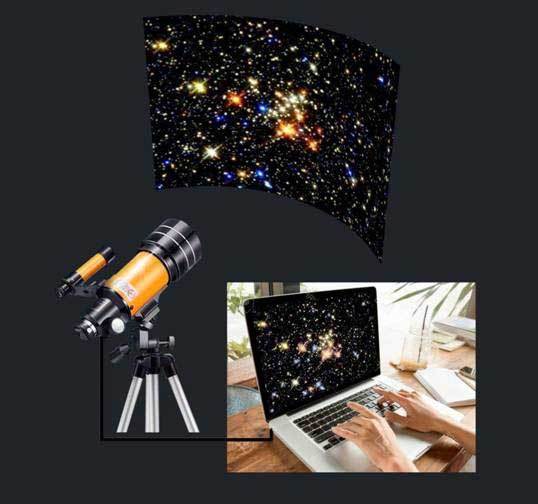

The case for readdressing the three paradigms of basic astrophysics

A long held misunderstanding of stellar brightness is being corrected, thanks to a new study published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society based on International Astronomical Union (IAU) General Assembly Resolution B2.

“Stars have been observed for millennia and were crucial in navigating across deserts, seas, and oceans,” noted Zeki Eker, the study’s lead author. Stars are even more crucial today for guiding us to the secrets of universe. This is, however, assured only if their radiating power is measured correctly.

Image credit to Garo Yontan

Image credit to Garo YontanBrightness differences as small as hundredths—even thousandths—of magnitude is measurable today since the advent of Charge Coupled Devices, or CCDs, in space-born observations. There were only visual magnitudes until photography met telescopes at the end of the nineteenth century. Soon sensitivity difference in photographs was discovered; as soon as photo-plates like human eyes were invented, the two kinds of magnitudes, blue (photographic) and visual, started to be used. Today, there are many filters to see how a star shines at various colours, including those the eye cannot see. Filtered magnitudes are calibrated by a star called “Vega,” the zero point for all magnitudes. Measuring the magnitude of a star at various filters is needed for obtaining its surface temperature. Its absolute size or distance and angular size are also needed to obtain its absolute power: luminosity, energy radiated per second (Watt) from a star. But, these are only accessible in certain types of binary stars. Astronomers had to find a way to assign luminosity to each star, in the same way as light bulbs sold in markets would be useless if the power (Watt) is not written on them.

By the end of 1930s, a new kind of magnitude with an arbitrary zero point flourished. Unlike blue and visual, this new magnitude, named bolometric, represents the luminosity of a star, including all its colours—visible and not visible. This new magnitude is for calculating the luminosity of a star in one step, but it is not observable; no telescope could observe total radiation of a star including gamma-rays, X-rays, UV, visible, infrared, and radio at once. Bolometric magnitudes, therefore, were computed first from known luminosities of a very limited number of binary stars. Because luminosity is more than one of its parts, called visual luminosity, the idea that “bolometric magnitudes should be brighter than visual magnitudes” entered astrophysical textbooks and literature as the first paradigm and went unchallenged for 80 years.

The difference between bolometric and visual magnitudes is called bolometric correction (BC). BC is a useful concept: if it is added to a visual, the bolometric magnitudes can be obtained, and so there is no need to observe a star of various colours at once. Using the limited number of existing BC as a calibrating sample, many tables are published to give BC as a function of stellar effective temperature, a parameter available from multicolour photometry, simply from blue and visual magnitudes.

BC is like a missing part; when added to visual magnitude, the bolometric magnitude is obtained. The magnitude scale is in reverse order, like first class is more valuable (brighter) than the second, and second is brighter than the third, so on. That is, the smaller the number the brighter it is. Therefore, the BC values were recognized as negative numbers. Consequently, “the BC of a star must be negative” became the second paradigm.

Inconsistencies between paradigms become obvious if one pays attention to the third paradigm; the arbitrariness attributed to the zero point of BC scale. Studying BC tables published, one realizes that there are two groups: a group of BC tables with all negative numbers, and a group of BC tables with mostly negative but also containing a limited number of positive. Obviously, the first group of producers took the arbitrariness granted and felt free to change computed BC in such a way that no single positive BC was left in the table in order to avoid dilemmas; while the other group trusted their calculations by keeping them as calculated and did not care about the paradigms. It is obvious that both cannot be right: either one of them is wrong. Another inconstancy is that there are occurrences that the same star is found to have different bolometric magnitude and luminosity, which is not true, among the scientists who use different BC tables with different zero point.

A solution was suggested by the IAU General Assembly in 2015, where the zero point of bolometric magnitude scale is fixed by a convention of worldwide astronomers and astrophysicists, called 2015 IAU General Assembly Resolution B2. Apparently, the established paradigms must be very strong, however, as even after the resolution published, an article appeared in one of the major journals still defending arbitrariness of the zero point of BC scale. IAU’s solution, therefore, stayed hidden for six years. Finally, proving that fixing the zero point of bolometric magnitudes has a firm consequence, the zero point of BC scales must also be fixed by a zero-point constant equal to the difference of the zero-point constants of bolometric and visual magnitudes. This firm positive zero-point constant of BC scale, on the other hand, requires a limited number of positive BC. So, “bolometric magnitudes should be brighter than, visual magnitudes” is not necessarily true.

Now, it is time to remove those paradigms from the textbooks, teaching minds, and researchers. This is needed urgently for consistent astrophysics as well as achieving accurate standard BC and stellar luminosities. Accurate standard stellar luminosities are needed not only by stellar structure and evolution theories, but also by galactic and extragalactic astrophysics to search amount of luminous matter in galaxies, to determine galactic and extragalactic distances, and thus even it could be useful for recalibrating Hubble law and restudying cosmological models of universe with better galactic and extragalactic luminosities, because galaxies are made of stars. This is how stars would lead us to the secrets of the universe.

Featured image by Faruk Soydugan

July 16, 2021

Have humans always lived in a “pluriverse” of worlds?

In the modern West, we take it for granted that reality is an objectively knowable material world. From a young age, we are taught to visualize it as a vast abstract space full of free-standing objects that all obey timeless universal laws of science and nature. But a very different picture of reality is now emerging from new currents of thought in fields like history, anthropology, and sociology.

The most powerful of these currents suggests that reality may not be singular at all, but inherently plural. Far from being an eternally fixed material order, it is better seen as a complex historically variable effect, one that is produced whenever human communities regularize their life-sustaining interactions with the fabrics of the planet. In short, humans have always lived in a “pluriverse” of many different worlds, not in a universe of just one.

Far-fetched as this idea might seem at first sight, it can be supported by a number of compelling arguments.

First, on purely historical grounds, it is clear enough that billions of humans have thrived in the past without knowing anything at all of our objective material reality or its timeless laws of being. Countless non-modern peoples, from ancient Egyptians to Indigenous Amazonians, have sustained themselves successfully for hundreds if not thousands of years, despite staking their lives on very different realities, on worlds full of gods, ancestral spirits, magical forces, and so many other things which our science would deem unreal. Did they all just get lucky?

Second, on ecological grounds, one could point out that our own modern reality normalizes a human-centered individualist way of life which has imperiled the whole future of the planet in just a few hundred years. On specifically humanitarian grounds, one could add that this same modern way of life has precipitated innumerable other horrors along the way, from colonialist genocides, chattel slavery, and systemic racism to two world wars and the Holocaust. If, as we like to believe, this scientifically grounded order is aligned with life’s ultimate truths, how come it has diminished and destroyed so much life in its brief history?

Then there is the philosophical argument, which can only be briefly summarized here. The very idea of an objectively knowable world has been questioned by influential thinkers for more than a hundred years. Many critics would now claim that the most essential contents of any reality are relations not things. All phenomena, whether human or non-human, material or immaterial, are effectively made of the relations with all the other phenomena on which their existence depends. Hence, it is impossible for any humans to know a world objectively, as something separate from or external to themselves, because they are always inextricably entangled in the relations that make up that world. They can only know reality from a particular location in time and space, wherever they happen to be entangled, whether it be ancient Egypt, the Amazonian rainforest, or modern Europe. And if so, no lived historical reality will ever be more universally or absolutely real than any other.

These three arguments for a pluriverse in turn encourage a fourth, which is ethical in nature. If humans have successfully inhabited numberless different realities, none of them more ultimately real than any other, then all established human communities should be free to pursue their own ways of life in worlds of their own choosing. This ethical imperative would necessarily rule out all forms of imperialism and colonialism. And it would expressly support the larger cause of “decolonization,” especially the efforts of Indigenous and other subaltern peoples to maintain or revitalize their own local ecologies in their own ancestral worlds of experience.

Needless to say, this pluriverse idea has profound and far-reaching implications for our understanding of the whole human story.

From a pluriversal perspective, the past would no longer look like a kind of extended overture to the present, where all humans inhabit the same world and struggle along a common path of “progress” towards western modernity. Instead, it would look like a vast panorama of autonomous worlds, where life was secured by a wondrous array of relations, beings, and forces that defy our narrow technoscientific imaginations.

As a result, the modern present would no longer look like the culmination of some grand story about the “triumph” of a “western civilization.” It would instead look like a bizarrely self-defeating historical anomaly, a world that has inflicted more catastrophic damage on planetary life than any other in just a few centuries.

Then again, a pluriversal perspective would dramatically broaden our horizons of possibility as we face the future and try to imagine more humane, more ecologically responsible modes of life. As ancient Egyptians, Indigenous Amazonians, and innumerable other non-modern peoples have shown us, it is entirely possible to pursue less harmful ways of being human in worlds very different from our own.

Feature image by Greg Rakozy from Unsplash.

July 14, 2021

On beacons, tokens, and all kinds of wonders

Two weeks ago (30 June 2021), I wrote about the origin of the word token and promised to continue with beacon. A set of gleanings intervened, which was a good thing and a good token: gleanings mean that there are enough questions and comments to discuss. Comments are not always friendly, but who can live long without making mistakes and arousing someone’s anger?

Let me begin by saying that the best authorities disagree on the etymology of beacon, and my suggestion with which I’ll finish this essay is my own. With very few exceptions etymological dictionaries (to say nothing of all-purpose dictionaries, even their recent online versions) rarely discuss the multiple conjectures that have accrued around the history of hard words. Nor is compiling such detailed surveys always worth the trouble. Modern (that is, post-medieval) European etymology is four centuries old, and a lot of rubbish has accumulated in journals and books between the early sixteen hundreds and today. In this blog, I don’t even try to present the endless controversy surrounding such cruxes as boy, girl, man, child, some animal names, and so forth, let alone slang. At best, I merely scratch the surface. That is why below I’ll confine myself to the most basic hypotheses concerning beacon. The obscurity surrounding it will remain.

The word surfaced early. Its Old English form was bēacen (ēa designates a long diphthong: ē followed by a). The other West Germanic forms were similar. Old Icelandic bákn was borrowed, more probably from some Low German dialect. But the exact lending language is of no importance in this context: whatever the source, the original noun seems to have been restricted to West Germanic. It does not occur in the fourth-century Gothic translation of the New Testament, and it probably did not exist in that language, because a proper context for it was present more than once. As far as we can judge, beacon is a relatively local word, and this fact complicates attempts to find its Common Germanic, let alone Indo-European, ancestor. Searching for a phantom and pretending to have found it does not look like a rewarding enterprise.

The best authorities disagree on the origin of beacon. (Image by UK Parliament via Flickr)

The best authorities disagree on the origin of beacon. (Image by UK Parliament via Flickr)But before throwing a quick look at the picture, we should first keep in mind all the attested senses that Old English bēacen (which sometimes occurred with the prefix ge-) had: “sign, phenomenon, portent, apparition, banner,” and once “an audible (!) signal.” The word made its way into both prose and poetry. Only two glosses on Latin words (both compounds), namely bēacen-fȳr (fȳr “fire”) “lighthouse” and bēacen-stān (stān “stone”) “a stone on which to light a beacon,” testify to the early existence of bēacen in its modern sense. The cognates of beacon in the related languages regularly refer to miraculous events. That is why the word easily passed into religious and philosophical language. In Old English, we find ge–bēacnung “categoria” (-ung is a suffix). In Low German, boken glossed Latin misterium, omen, while Middle Dutch bokene was explained as “phantasma, spectrum.”

Of special interest is Old Icelandic bákn. In the extant texts, it turned up only twice, both times in a verse. It seems to have meant “a sign with which one hopes to ensure victory” (the exact sense is hard to establish because the occurrences are so few). Clearly, in the north, bákn sounded exotic and was chosen for a special effect, the more so as it occurred in a verse (a most unusual thing for a borrowing in Old Icelandic). Since it was a loanword, it may have preserved the sense it had in the lending West Germanic language. One thing is obvious. If we want to understand the evolution of beacon, we should remember that “lighthouse” is almost certainly not the beginning of its semantic history. We should rather begin with “portent; miracle; ominous sign.” The opposite way, from a mundane lighthouse to miraculous and supernatural phenomena is unlikely (though such a way has been considered). Incidentally, the English verb beckon is directly related to beacon, but the shortening of the root vowel destroyed the connection. Beck in the idiom at one’s beck and call is a shortened form of beckon. We seem to be no longer aware of that connection either.

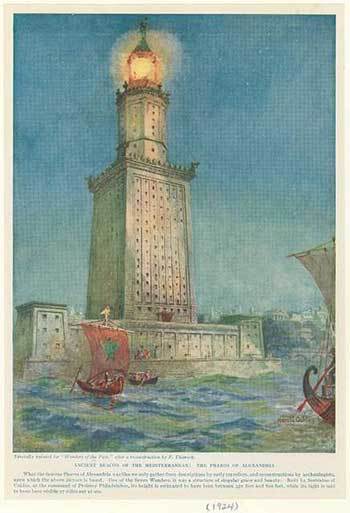

An ancient beacon. (Image: Ancient beacon of the Mediterranean: The Pharos of Alexandria, via New York Public Library)

An ancient beacon. (Image: Ancient beacon of the Mediterranean: The Pharos of Alexandria, via New York Public Library)All attempts to discover the origin of beacon remain guesswork.

1) In the Germanic languages, some words begin with b-, which is a remnant of the old prefix be-. For instance, German bleiben “to stay” goes back to be-leiben and is cognate with the English verb leave. Perhaps the root of beacon is auk-n-, with auk– meaning “eye,” as in German Auge? Beacon will then emerge as “a thing seen.” The origin of final –n remains unexplained.

2) Or the root of beacon means “shining,” but the supporting evidence is meager (one unclear Icelandic word).

3) Or beacon is in some way connected with such words as German Baum ~ Gothic bagms “tree.” However, early “beacons” (signs, apparitions, monsters, banners, and funeral mounds) were certainly not trees. Nor were they exclusively signal fires, which makes all etymologies of beacon based on the concepts of sheen and brightness suspect.

4) If beacons were initially audible signals, perhaps we should look for the best solution in comparing beacon with Latin būcina “signal horn,” which has come down to us as English bassoon. Or perhaps German Pauke “kettledrum” contains a better hint of where beacon came from.

Baltic, Celtic, Hebrew, along with German regional lookalikes, have also been suggested as helpful clues and discarded or even never considered seriously. Yet it seems that a fairly realistic solution was suggested more than a century ago, though it did not deal expressly with beacon. Even eighteenth-century researchers noted that English and German words beginning with b- and p- often convey the idea of swelling. Such are big, bag, bug, buck, pig (the Dutch for “pig” is big!); bud, pod, poodle, and many, many others. We are dealing with a group of similar “expressive” words transcending the borders of the Germanic family. Swollen and noisy “bogeys” cross language barriers and defy sound laws.

These are the presumed linguistic relatives of our beacon. (Image by (L) prof.bizzarro, (R) Tam Tam, via Flickr)

These are the presumed linguistic relatives of our beacon. (Image by (L) prof.bizzarro, (R) Tam Tam, via Flickr)I believe that the original meaning of beacon was “apparition; specter, etc.,” which only later acquired the specialized sense “signal fire.” Such creatures are of course able to swell, howl, shine, and frighten people. This view is only partly mine. If it deserves consideration, we should agree that beacon has no Indo-European roots (this is something I have suspected all along). The Germanic protoform was bauk-.

The question that has not been addressed in this reconstruction is the origin of –n. Here I depend on my own hypothesis. I notice that token and beacon were very close, almost interchangeable synonyms in Old English, and that is why I began this two-part series with token. Above, I listed the recorded senses of Old English bēacen. Compare the senses of Old English tācen: “symbol, sign, signal, mark, indication, suggestion; portent, marvel, wonder, miracle; evidence, proof; standard, banner.” It seems likely that the two words interacted and influenced each other and that beacon acquired its –n form tācen. No proof is forthcoming: all that a matter of verisimilitude.

Closely connected with the history of beacon is the history of buoy, but the etymology of buoy cannot be discussed in a postscript to this essay. I may return to buoy but not in the immediate future.

Featured image by Mitch Mckee via Unsplash

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers