Oxford University Press's Blog, page 110

April 28, 2021

Putting my mouth where my money is: the origin of “haggis”

I have never partaken of haggis, but I have more than once eaten harðfiskur, literally “hard fish,” an Icelandic delicacy one can chew for hours without making any progress. This northern connection makes me qualified for discussing the subject chosen for today’s post. Haggis, to quote The Oxford English Dictionary (The OED), is “a dish consisting of the heart, lungs, and liver of a sheep, calf, etc. (or sometimes of the tripe and chitterlings), minced with suet and oatmeal, seasoned with salt, pepper, onions, etc., and boiled like a large sausage in the maw of the animal.” What a minefield for a foreign learner! Haggis is pronounced with hard g (as in haggard), while sausage has short o (unlike sauce). And chitterlings, suet, tripe, maw…. How many years of “advanced English” does one need to be able to eat one’s way through this definition with ease and grace? Woe to the conquered!

Anyway, the word haggis exists, and its history poses a few questions. The OED has grave doubts about its origin, though the idea that we are dealing with something hashed or hacked (even better, “hagged, hewn”) comes to mind at once. John Jamieson, the author of the great dictionary of the Scottish language wrote: “Dr Johnson [a famous English lexicographer] derives haggess [sic] from hog or hack. The last is certainly the proper origin; if we may judge from the Swedish term used in the same sense, jack-polsa, q[ua] minced porridge. Haggies [sic] retains the form of the S[cottish] v[erb] hag….” French hachis “hash” has also been suggested as the etymon of haggis.

Walter W. Skeat was a man of strong convictions, and at every moment of his career thought that he had discovered the truth, though he more than once changed his opinions. In 1896, he wrote in refutation of an improbable etymology of haggis:

“The word derived from F[rench] haut gout is the Prov[incial] E[nglish] ho-go, which is not remarkably like haggis. It is quite impossible that haggis can be ‘descended from the F[rench] hachis’, though I believe these words to be closely related. I have already shown that haggis is from the M[iddle] E[nglish] hagace or hagas, also found as hakkis…. It is clearly an Anglo-French derivative from the English verb to hack….”

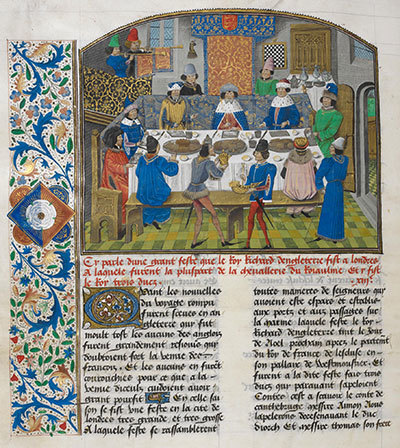

Medieval diet. (Jean de Wavrin, Recueil des chroniques d’Angleterre (Volume III), via the British Library.)

Medieval diet. (Jean de Wavrin, Recueil des chroniques d’Angleterre (Volume III), via the British Library.)But in the latest edition of his etymological dictionary, he derived haggis, via Anglo-French, from hag “to cut up, to chop up,” whose source is Scandinavian. In dealing with haggis, we are left with the constantly recurring question: from hack or from hag?

All those explanations sound confusing: too many similar forms and too many languages (Middle English, Scottish, Anglo-French, and Scandinavian). Also, the differences between the proposed etymons seem to be minuscule: hag, hack, hash…. Where is the problem? First, we need some clarity about the word’s chronology. It is usually (though not everywhere) said to have emerged in the fifteenth century, that is, in Middle English. At that time, French, the language of the descendants of William the Conqueror and his hosts, competed with English, the native language of the island’s population. But the French spoken in England was significantly different from the French of the metropolis. In the past, it was referred to as Anglo-French. The modern (more accurate) term is Anglo-Norman. The vocabulary of the early extant cook(ery)-books is overwhelmingly Anglo-Norman, so that the French origins of haggis does not come as a surprise, even though the dish hardly graced the tables of the aristocracy (or so I think). According to the findings of William Rothwell, one of the greatest experts in the history of medieval French spoken in England, “it would appear likely that, by the middle of the thirteenth century, the English were eating haggis, crackling and suet.” Good for them!

Rothwell maintains that haggis goes back to the Anglo-Norman verb hacher, known to English speakers from hash “cut up small for cooking” and hatchet, a small hache “ax(e).” Hag “to cut” is still current in dialects, and haggle is its so-called frequentative form” (that is, “to hag often or many times”), which means not only “to wrangle in bargaining” but also “to mangle with cuts.” Monosyllabic verbs like cut, dig, hack, hag, hit, put, tug, and so forth are probably sound-imitative or at least “symbolic” (they produce the impression associated with an effort or an abrupt movement). In any case, etymologists have very little to say about them

Medieval peasants at table. They can enjoy haggis without knowing Anglo-Norman. (David Teniers, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Medieval peasants at table. They can enjoy haggis without knowing Anglo-Norman. (David Teniers, via Wikimedia Commons.)It is not clear whether Rothwell read the 1959 article by Charles H. Livingston, whose conclusion was in some respects close to his own. In Livingston’s opinion, haggis is not related to northern dialectal English and Scottish hag of Old Norse origin. The word, he suggested, goes back to Old Norman haguier “to chop,” whose etymon is Middle Dutch hacken. (This is a typical case: some West Germanic word makes its way into Old French and returns to Middle English from Anglo-Norman or from continental French.) Both researchers not unexpectedly traced the etymon of haggis to Anglo-Norman, but they disagreed about the ultimate source (haguier versus hacher), and both deviated from the conclusion of the old OED. Incidentally, Old English had the verb hæccan, an etymological doublet of Modern English hack, rather than its etymon.

This may not be a proper place for haggling about the details, but, judging by the post-OED research, the early date of haggis seems certain. Other than that, no one doubts that haggis is a culinary term of Anglo-Norman ancestry. If we follow Rothwell and Livingston, we’ll go even further, and the word will stop being one of uncertain origin.

A kind of pie. (By Airwolfhound, CC BY-SA 2.0.)

A kind of pie. (By Airwolfhound, CC BY-SA 2.0.)The most amazing etymology of haggis can be found in Ernest Weekley’s English etymological dictionary. Apparently, he wrote, the word arose by “some strange metaphor” from French agasse ~ agace “magpie.” He referred to the two senses of pie (“dish” and “magpie”) and to the noun chewet “daw” and “meat pie.” The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (The ODEE) (1966) dismissed haggis as being a word of unknown origin and cited only Weekley’s hypothesis as worthy of mention. (Though The OED does not overwhelm the user with bibliographical references, James A. H. Murray did not refrain from naming numerous scholars to whom he was indebted. The ODEE never does so, and I wanted to give the source of that ingenious conjecture.) Yet it was Beatrix Potter (The Tale of the Pie and the Patty-Pan), who observed that a magpie was also a kind of pie. Regrettably, she had nothing to say about haggis.

Featured image by quimby (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The post Putting my mouth where my money is: the origin of “haggis” appeared first on OUPblog.

How can feed additives enhance forage-based diets of beef cattle? [Infographic]

Beef cattle production systems often rely on forage-based diets, consisting of pasture, as a low cost and widely accessible method for feeding herds. Whilst there are financial and practical benefits to forage-based diets, it is important to note that seasonal variations in pasture availability and nutritive quality can impact cattle performance and nutrition. So, are there any solutions to this?

Feed additives are used as an important nutritional tool to enhance productivity and profitability of beef cattle systems. Additives can alter the microbiome of cattle stomachs, where plant fibers are incrementally broken down by fermentation into smaller and more digestible structures, and therefore can affect food digestibility and nutrient utilization. The majority of research into feed additives is focused on high-concentrate diets, comprised of concentrates and feeds with a high content of nutritional substances. There has been little research on feed additives and forage-based diets.

A recent study from The Journal of Animal Science hypothesized that foraged-based diets supplemented with one of three feed additives narasin, salinomycin, or flavomycin would impact nutrient digestibility, change fermentation parameters, and improve productivity in Nellore cattle. To test this hypothesis, the cattle were split into three groups, each being fed a forage-based diet supplemented with aa different feed additive for 140 days. The study found that narasin was the only feed additive that benefited performance and fermentation in Nellore cattle.

The study highlights the importance for beef producers to understand how feed additives can help optimize the diets of their cattle and improve performance. Explore the infographic below to find out more.

Take a further look into this topic with related articles from The Journal of Animal Science:

“Responses in the rumen microbiome of Bos taurus and indicus steers fed a low-quality rice straw diet and supplemented protein.” Latham, E.A., K.K. Weldon, T.A. Wickersham, J.A. Coverdale, and W.E. Pinchak. 2018.“Effects of roughage sources produced in a tropical environment on forage intake, and ruminal and microbial parameters.” Ribeiro, RCO, S D J Villela, S C Valadares Filho, S A Santos, K G Ribeiro, E Detmann, D Zanetti, P G M A Martins. 2015.“The use of live yeast to increase intake and performance of cattle receiving low-quality tropical forages.” Parra, M.C., D.F.A. Costa, ASV Palma, KDV Camargo, LO Lima, KJ Harper, SJ Meale, LFP Silva. 2021.The post How can feed additives enhance forage-based diets of beef cattle? [Infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 27, 2021

Environmental histories and potential futures [podcast]

This month marked the 51st observation of Earth Day, which, in the past decade, has become one of the largest secular observances in the world. This year, more than 1 billion individuals in over 190 countries are engaged in action to promote conservation and environmental protectionism. In this current moment, the discourse surrounding environmentalism seems to exist primarily in the realms of science and politics, but we wanted to take this opportunity to talk to a couple of researchers who study humankind’s relation with the earth in a broader perspective.

The academic fields of both environmental history and future studies originated in the late 1960s and early 1970s during the rise of the mainstream environmental movement. On today’s episode of The Oxford Comment, we are joined by environmental historian Erin Stewart Mauldin, author Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South, and Jennifer Gidley, the past president of the World Futures Studies and author of The Future: A Very Short Introduction, to learn more about how these two areas of study look at our relationship with the environment and how these valuable perspectives can engage, and inform, our environmental understanding.

Check out Episode 60 of The Oxford Comment and subscribe to The Oxford Comment podcast through your favourite podcast app to listen to the latest insights from our expert authors.

Oxford Academic (OUP) · Environmental Histories and Potential Futures – Episode 60 – The Oxford CommentRecommended reading

To learn more about environmental history, you can browse our reading list of seven new books on environmental history ranging from a study of the Tigris and the Euphrates to the role of the environment in shaping the experiences of Japanese American’s incarcerated during the World War II. You can also read a chapter from Erin Stewart Mauldin’s book, Unredeemed Land, exploring the ecological regime of slavery and land-use practices across the antebellum South.

For further reading on future studies, you can read a chapter from Jennifer Gidley’s VSI: Technotopian or human-centred futures?. Dr. Gidley also wrote a piece for the OUPblog exploring the challenges, and surprises, of global futures, and she was a guest on The Very Short Introductions Podcast last fall. Finally, you can learn more about the course she’s developed on environmental futures at Ubiquity University.

Featured image by @aleskrivec ( CC0 via Unsplash).

The post Environmental histories and potential futures [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 26, 2021

From fortified castle to wedding venue: Venetian examplars of adaptive reuse

What does one do with a castle? The Venetian Terraferma (and, indeed, all of Europe) is dotted with medieval castles that have long outlived the purposes for which they were intended. And yet, built of stone, they are costly to demolish and—more importantly—of great historical interest. Despite fires, earthquakes, and simple neglect, many remain standing thanks to the creativity of owners, architects, and municipalities in finding ways to restore and preserve these evocative palimpsests of the past.

The challenges were daunting. Lacking electricity, all such complexes had to be wired (not just rewired) with up-to-code modern installations, not to mention internet connections. Lacking modern plumbing, all had to be retrofitted with a supply of running water, sewers, and new bathrooms. Lacking heating and air conditioning, all had to augment fireplaces and braziers with modern HVAC systems for heating, ventilation, and cooling. The difficulty of making such improvements was compounded by the necessity to accommodate them within rigid stone walls, that themselves required repointing and repair.

Wedding venueThe Castello di Villalta is situated atop a mound in the countryside overlooking vineyards and fields of grain with views south all the way to the Adriatic on a clear day. Home of the Della Torre family since the fifteenth century, the medieval castle was badly damaged by an earthquake and a peasant uprising in 1511 but was soon rebuilt and expanded with a Renaissance wing. The site of a Della Torre fratricide in 1699, the castle was abandoned after the execution of Lucio Della Torre in 1723 for the murder of his Venetian wife and became something of a haunted house, with rumors of subterranean escape passages and Lucio’s ghost prowling the walls at night. The Della Torre heirs sold off the castle, with crumbling walls and fallen ceilings, in 1905. During the First World War it served as an Austro -Hungarian command post after the defeat of the Italian army in the Battle of Caporetto. After passing through several hands and partial restorations, the castle was reacquired by descendants of the Caporiacco family, its original owners, in 1999, and today—carefully restored and updated—it serves not only as a captivating venue for wedding celebrations, but also as a site for concerts, meetings, and cultural events.

Castello di Villalta. (Reflexbook.net)Castle museum

Castello di Villalta. (Reflexbook.net)Castle museumThe Castello di Udine stands atop an acropolis overlooking the city. After the earthquake of 1511, it was built as a replacement of the thirteenth-century residence of the Venetian Luogotenente of the Patria del Friuli. With the fall of the Venetian republic in 1797, Napoleon ceded the building to the Austrian army, which used it as a headquarters and barracks. The massive building became a museum in 1906 to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the unification of the Friuli with Italy, and now hosts the Museo del Risorgimento and the Museo Archeologico on the ground floor; the Galleria d’Arte Antica, with paintings from the fourteenth through the nineteenth century, on the main floor; and the Museo della Fotografia on the top floor. It also features numismatic, sculpture, and plaster cast collections and galleries of prints and drawings, as well as art and photo libraries.

Joseph Heintz il Giovane, View of Udine, detail, c. 1650-60. Udine, Civici Musei, Galleria d’Arte Antica, inv. 65. (Fototeca, courtesy of Civici Musei di Udine.)Municipal offices

Joseph Heintz il Giovane, View of Udine, detail, c. 1650-60. Udine, Civici Musei, Galleria d’Arte Antica, inv. 65. (Fototeca, courtesy of Civici Musei di Udine.)Municipal officesThe fourteenth-century Castello di Colloredo di Monte Albano, consisting of a central block, three towers, and two wings, was the residence of the Della Torre’s closest relatives. Also badly damaged in 1511, it was rebuilt by the mid-sixteenth century with a studio frescoed by the artist Giovanni da Udine. Over the years, it was the home of poets and writers, including Ermes da Colloredo (1622-1692) and Ippolito Nievo (1831-1861). The Friuli was hit by a devastating earthquake in 1976, and the east wing of the castle crumbled to the ground. But the west wing, although damaged, survived and presently houses the Comunità Collinare del Friuli—a consortium dedicated to safeguarding the environment and promoting culture, tourism, and planning for fifteen small communities. The remainder of the castle is still undergoing reconstruction.

Castle of Colloredo di Monte Alban, province of Udine, region Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy, by Johann Jaritz. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)Spiritual retreat

Castle of Colloredo di Monte Alban, province of Udine, region Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy, by Johann Jaritz. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)Spiritual retreatA few castles retain their original function. The sprawling Castello di San Martino, perched on a hillside above the town of Ceneda (now part of Vittorio Veneto), was built in the tenth century as the residence of the prince-bishop of the diocese and expanded over the years by a Della Torre bishop and others. After the fall of the Venetian republic, the new Kingdom of Italy passed a law in 1866 requiring the sale of church properties. The castle was put up for auction, but there were no buyers and it remained the property of the state. After the complex suffered significant damage in an earthquake in 1873, it was returned to the diocese in 1881. Restored by the church, it remains the residence of the bishop to this day. But it too has been adapted for modern use with two chapels, 30 guest rooms, a dining room, meeting rooms, and a large garden.

Aerial view of Castello di San Martino, Ceneda (Vittorio Veneto). (Reflexbook.net)Evocative landmark

Aerial view of Castello di San Martino, Ceneda (Vittorio Veneto). (Reflexbook.net)Evocative landmarkSome castles remain picturesque ruins. The eighteenth-century façade of the villa built atop the remains of the thirteenth-century Castello di Polcenigo (once the marital home of a Della Torre daughter) remains intact, but the remainder was gutted by fire. It now stands like an empty doll house, with the rooms open to the sky. The fireplaces and fragments of frescoes are still visible, along with sweeping view of the surrounding countryside, to the adventurous who climb a monumental stone staircase of 366 steps or wend their way up a subterranean passage from the town below.

Castello di Polcenigo, by Di Vmviz. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.)

Castello di Polcenigo, by Di Vmviz. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.)These palimpsests of stone and timber embed the present in the feudal past. The medieval castles no longer serve as enclosures as defense, but as welcoming venues of hospitality, tourism, and cultural enrichment.

The post From fortified castle to wedding venue: Venetian examplars of adaptive reuse appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2021

What if COVID-19 had emerged in 1719?

We’re often told that the situation created by the attack of the new coronavirus is “unique” and “unprecedented.” And yet, at the same time, scientists assure us that the emergence of new viruses is “natural”—that viruses are always mutating or picking up and losing bits of DNA. But if lethal new viruses have emerged again and again during human history, why has dealing with this one been such a struggle?

The uniqueness of this viral attack isn’t because of mutations in its DNA or in the DNA of the human genome. Its uniqueness is result of changes in what is sometimes referred to our “cultural DNA”—changes that have occurred in the last few centuries. It’s these “mutations” that have made us extremely vulnerable to this rather ordinary new virus.

If this novel coronavirus had emerged in 1719 instead of 2019, the effect would have been very different. For a start, the disease might not have spread beyond the place where it first appeared. Most people didn’t move around much in 1719. But merchants did, so if a merchant became infected at a market in Wuhan, he might have carried the virus to other markets and passed it on to other merchants. Then it could have spread, at walking pace, around the globe. But, if an infected merchant had turned up at the market where your ancestors shopped 300 years ago, they might have still escaped infection. This is because villagers in 1719 were in the habit of keeping strangers at arm’s length. Over the millennia, people who had been too trusting and friendly had been swindled, robbed, and infected. Fear of strangers was passed down the generations, helped by legends of witches, goblins, and shape-shifting trolls. Three hundred years later, we may still teach our children to be wary of strangers, but we also encourage them to trust. We want them to feel comfortable in public places and believe that food prepared by strangers in a restaurant is safe to eat.

“No one was collecting, analyzing, or publishing public health data in the 1700s.”

Despite their nervousness around strangers, the new coronavirus may have eventually spread to some of the communities where your ancestors lived in 1719. They would have then been at risk. But they wouldn’t have been aware of any extra risk. Life in the community wouldn’t have changed much. As is the case today, the virus would have caused mild symptoms or no symptoms at all in most of its victims. A few would have become very ill and if they died, their friends and family would have grieved in the normal way. Plenty of eighteenth-century death records mention “fever” as the cause of death. But no one was collecting, analyzing, or publishing public health data in the 1700s. No one would have worried about a shortage of hospital beds because there were no hospitals—at least not hospitals as we know them. People were nursed at home by their families. Doctors and other healers visited people on their sickbed but not everyone could afford their fees, and there was little these medics could do anyway. Their beliefs about the causes of fevers were wrong and their idea of “intensive care” might have involved using leeches to remove some of their patient’s blood.

Your ancestors might have noticed that a few more people had fever in the year that the new virus attacked, but it wouldn’t have been remembered as a pandemic year. The “Black Death” plague, which sickened Eurasia and Northern Africa during the middle years of the 1300s, was a pandemic. It probably killed over a 100 million people at a time when the entire human population was only about 500 million. Entire towns and villages were wiped out.

The coronavirus caused a pandemic in the 2020 population because we’re very different from the humans who lived only a few centuries ago. In 1720, infections regularly spread through communities—cholera, yellow fever, malaria, measles, smallpox… to name but a few. An infected cut could be fatal. Most people died before they became elderly and, if they did become elderly and developed heart disease or cancer, they died quite quickly. Obesity was very rare. The COVID-19 death toll would have been tiny because, in those days, the human population had very few people in the high-risk categories.

Yes, it’s Modern Life that made us vulnerable to COVID-19. There have long been voices warning that the cushiness of our existence would make us weak. Perhaps some people might see this as a reason to return to what they think of as a “simpler and more natural life.” But this would be silly. Our vulnerability to this virus isn’t due to the failings of modern culture. It’s the result of its triumphs. Consumed by the worry of tragedies close to home, our ancestors didn’t have time to think about unknown others. They were barely aware of being part of “humanity.” The luxury of feeling reasonably secure in our lives has made the unexpected and (we hope) temporary perturbation in our security feel like a terrible and upsetting shock.

“Arguments about fairness are a healthy sign. In 1719, not only was there no understanding of immunization; there was no understanding that humans could and should strive for fairness.”

Lives matter to most people today—all lives. We haven’t just become more squeamish about sickness and death. We care more and we care about more people. This cultural change can’t be explained by things like freedoms, rights, wealth, or laws. The real reason for this change is that the world’s humans have become much more connected. And, if we feel that we should strive for justice, fair trade, and the free exchange of ideas, it’s because we feel part of a complex network that binds together humans who will never physically meet. This network barely existed in 1720 but, over the last three centuries, the ancestors of people from all nations forged new links. The trust between people and peoples gradually grew. This is still a work in progress. The network of connections remains tragically weak in some places, and some people don’t feel connected at all. But the building and strengthening of this network is continuing.

As our twenty-first-century pandemic began, some people expressed hope that getting through this together would increase trust and make our societies stronger. Could this be true? We’re now arguing over the fairness of the vaccine rollout. But arguments about fairness are a healthy sign. In 1719, not only was there no understanding of immunization; there was no understanding that humans could and should strive for fairness.

Human cultures continue to mutate at an eye-watering rate. Each day brings unexpected new challenges. Disagreement of over what sources of information can be trusted is very worrying. But looked at over the long term, there’s reason to hope. Our times of mask-wearing and lockdown may give us a new appreciation of how precious social connections are. This may help to strengthen the net of trust between peoples.

The post What if COVID-19 had emerged in 1719? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 23, 2021

The “warrior gene”: blaming genetics for bad behavior

The extent to which we can blame our genes for bad behavior took another step backward recently, in the US at least, with a court ruling that data from the “warrior gene” couldn’t be used as an excuse for diminished responsibility.

Belief in the existence of a warrior gene has been around for more than 25 years, one of many examples where genetic effects on behavior have been misunderstood. In 1994, Stephen Mobley, convicted of murder, armed robbery, aggravated assault, and possession of a firearm, was sentenced to death. His trial occurred soon after the publication of a paper attributing aggression to a deficiency of MAOA. Supporting this claim were data reporting that eight men from the same family had repeated episodes of aggressive behavior. One had been convicted at the age of 23 of the rape of his sister. Another tried to run over his boss with a car at the sheltered workshop where he was employed after having been told that his work was not up to par. A third would enter his sisters’ bedrooms at night, armed with a knife, and force them to undress. At least two more were known arsonists. Han Brunner, the geneticist in the Netherlands who described this unfortunate family, found evidence that males with criminal behavior had a mutation in a gene on the X chromosome called monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), which is involved in the metabolism of neurotransmitters, including dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin, the last being the target of antidepressants such as Prozac. Since men have only one copy of the gene (one X chromosome), the men with the mutation in MAOA had no functional enzyme. On the face of it, MAOA mutations were making Dr Brunner’s patients aggressive. Mobley filed a motion seeking funds to hire expert witnesses to assess whether he, like the men in the paper, had a deficiency of the MAOA gene, which was later to become famous as the “warrior gene.”

It was Mobley’s bad luck that the court threw out his petition, and he was subsequently executed by lethal injection, but news of his defence soon spread. In Ohio in 2000, lawyers for Dion Wayne Sanders tried the MAOA argument, and though the court decided it could not be shown that when Sanders shot both of his grandparents he lacked the specific intent to kill them, the jury returned verdicts of imprisonment rather than the death penalty. And, in a case heard in Tennessee in 2009, with respect to the genetic data, the court found “as a matter of law, that the expert services sought are necessary to ensure that the constitutional rights of the Defendant are properly protected.” So began a saga that has persisted till February 2021, when the New Mexico Supreme Court threw out the “warrior gene” defence.

“almost all behavior is heritable (to some extent) and … arises from the joint contribution of thousands of individual genetic variants”

However, don’t imagine for a second that this is a death blow for genetic determinism. The court’s decision means that a mutation in a single gene (MAOA) can’t be blamed for violent acts, and since no one has found a mutation in any of the 23,000 other genes in the human genome that causes violence, it’s now pretty certain that there no warrior genes. But there is a possibility that we can blame someone’s genetic constitution in aggregate.

What’s become clear over the last decade is that almost all behavior is heritable (to some extent) and that it arises from the joint contribution of thousands of individual genetic variants. These variants are not mutations that kill a gene or give it a new function. In fact, individually, they don’t do much at all, just increasing or decreasing the likelihood of a behavior by a very small amount (if you think of it as percentage where the warrior gene has a 100% effect, then these variants have an effect less than 0.01%). While individually small, there are so many thousands of them that in total the effect is detectable. Scientists have been getting better and better at predicting behavioral outcomes from aggregate assays of genetic data. This is because genetic data is being harvested on an increasingly large scale; it’s routine to publish results from millions of individuals—one of the best and most productive sources of such data comes from the UK where 500,000 people were recruited into the UK BioBank. As datasets grow bigger, the predictive accuracy of genetic data has improved and is being touted in the clinics as a way to diagnose heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other common diseases. It won’t be long before lawyers realize they have a new toy: “don’t blame my client, he couldn’t help himself, it was all in his genes.”

The post The “warrior gene”: blaming genetics for bad behavior appeared first on OUPblog.

Can skepticism and curiosity get along? Benjamin Franklin shows they can coexist

No matter the contemporary crisis trending on Twitter, from climate change to the US Senate filibuster, people who follow the news have little trouble finding a congenial source of reporting. The writers who worry about polarization, folks like Ezra Klein and Michael Lind, commonly observe the high levels of tribalism that attends journalism and consumption of it. The feat of being skeptical of the other side’s position while turning the same doubts on your own team is apparently in short supply. The consequences of skepticism about disagreeable points of view for the virtues of intellectual curiosity are not good. Increased polarization reduces genuine inquiry to a search for reassurance. Awe or wonder about people opposed to wearing masks or advocates of the Green New Deal is increasingly a missing category, which is too bad because the variety of human experience can be truly breath-taking. H. L. Mencken called Americans the “greatest show on earth.”

One person who excelled in the curiosity recommended above, while also remaining skeptical about many parts of received orthodoxy (religious or otherwise) was Benjamin Franklin. Well known for his scientific experiments, diplomatic assistance during the American Founding, and his departure from the Puritan faith of his parents, Franklin qualifies as a moderate skeptic. Throw in that he was a Deist while a young man on the make in London and his skeptic-credit-score goes up a few points. At the same time, Franklin was relentlessly curious about the world around him.

With his reputation as a man of science (though still an amateur endeavor), Franklin’s curiosity about the natural world should come as no surprise. For instance, on his return to Philadelphia from London in 1726, Franklin passed the time by collecting seaweed. His observations of the leaves led to noting the pelagic crabs that were inside the plant and that possessed “a set of unformed claws” within “a kind of soft jelly.” In his journal Franklin speculated that the crabs’ shell was akin to the outer protection of silkworms and butterflies. Not a major discovery, but this was arguably a surprising level of detail for a young man with nothing but uncertainty about his future.

Another example of curiosity comes from a few years later, after he had set up his print shop. As the inventor of the so-called Franklin Stove, he was curious about heat—in the fireplace, in materials like wood and tile around the fire, but also in fabrics. To calculate which colored cloth absorbed the most heat, he laid patches of different color on snow outside his shop. Franklin discovered that the black patch sunk lower than the red, blue, green, and brown, so low in the snow, in fact, that it sunk “below the Stroke of the Sun’s Rays.”

Franklin was equally curious about human experience and how people interacted in society. This quality extended to religion, an area where Franklin veered from the norms of his day. (He was a god-fearer and approved of Christian morality even while he could never accept theological assertions such as the deity of Christ.) Curiosity about faith and people were vividly evident when Franklin went to hear the famous evangelist, George Whitefield. The preacher had a reputation for preaching to large crowds outdoors (obviously without electronic amplification). Franklin was skeptical. So he conducted another experiment. He could already tell that Whitefield had “a loud and clear Voice, and articulated his Words and Sentences so perfectly that he might be heard and understood at a great Distance.” But how many people could hear him? Franklin did the math:

He preach’d one Evening from the Top of the Court House Steps, which are in the middle of Market Street, and on the West Side of Second Street which crosses it at right angles. Both Streets were fill’d with his Hearers to a considerable Distance. Being among the hindmost in Market Street, I had the Curiosity to learn how far he could be heard, by retiring backwards down the Street towards the River; and I found his Voice distinct till I came near Front Street, when some Noise in that Street, obscur’d it. Imagining then a Semicircle, of which my Distance should be the Radius, and that it were fill’d with Auditors, to each of whom I allow’d two square feet, I computed that he might well be heard by more than Thirty Thousand. This reconcil’d me to the Newspaper Accounts of his having preach’d to 25,000 People in the Fields.

Franklin was not an advocate of organized religion. He did not mock it, though he sometimes ridiculed the ideas and practices of the faithful. Whitefield represented a chief specimen of zealous piety that Franklin, the skeptic, could well have satirized. Instead, his curiosity was as much a part of his initial observation as skepticism. His sense of inquiry about the workings of human affairs overtook his fairly firm ideas about Christianity. For Franklin, Whitefield was more than a specimen of Protestant piety. The evangelist was also a human phenomenon, as much a part of the natural world as seaweed, and Franklin wanted to know more.

Of course, the use of the past to correct the present is tedious and prone to moralistic clichés. Ben Franklin’s combination of curiosity and skepticism does deserve comment, however, since it is increasingly rare among the loudest voices in contemporary society. If more people in the business of news, ideas, science, and politics could lose themselves more in the variety of human existence and rush to judgment less, I bet that conversations on social media, around the dinner table, and even in the legislature might be as unpredictable and intriguing as the world that Franklin observed.

Featured image by amrothman

The post Can skepticism and curiosity get along? Benjamin Franklin shows they can coexist appeared first on OUPblog.

April 22, 2021

The coming refugee crisis: how COVID-19 exacerbates forced displacement

Refugees have fallen down the political agenda since the “European refugee crisis” in 2015-16. COVID-19 has temporarily stifled refugee movements and taken the issue off the political and media radar. However, the impact of the pandemic is gradually exacerbating the drivers of mass displacement. It is eroding the capacity of refugee-hosting countries in regions like Africa and the Middle East. While the framing of 2015-16 as a “crisis” has been contested, there is grounds to believe that, without decisive action, countries within and beyond refugees’ regions of origin may once again face overwhelmingly large refugee movements.

COVID-19, recession, and displacementAlthough rich countries have focused mainly on the health consequences of the pandemic, by far the greatest impact will be the economic consequences for the poorest countries around the world. From Sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East, a generation of development gains will be lost. Even before COVID-19, the world faced year on year increases in refugee and displacement numbers, and the potential for a further 140 million people to be displaced by climate change. Now, three causal mechanisms suggest a possible global refugee crisis in-the-making.

“Put simply, global depression exacerbates the known drivers of refugee movements.”

First, in countries of origin, global recession will lead to increases in conflict, authoritarianism, and state fragility. Most displaced people come from chronically weak states like Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Venezuela—and we know that these are the countries likely to be worst-hit by recession. Existing social science tells us what recession does to the root causes of displacement. For example, within the literature on the economics of conflict, Ted Miguel estimates that a 5% negative economic shock leads to a 0.5% increase in conflict in Africa. We know from the political science literature that that cuts in GDP/capita are associated with less democratic politics and increased levels of state fragility. Put simply, global depression exacerbates the known drivers of refugee movements.

Second, recession undermines the willingness and ability of low and middle-income countries to host refugees. Rich countries bank on the assumption that displacement will remain contained within regions of origin. The refugee system has long been premised upon frontline countries—like Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Kenya, Uganda, and Bangladesh—taking in refugees. 85% of the world’s refugees are hosted in low and middle-income countries, and the majority of displaced people remain within their countries of origin as “internally displaced persons.” But the problem is that the capacity of these frontline states is being stretched to breaking point by economic crisis.

Amid COVID-19, we see states like Lebanon, which hosts 1.5 million Syrian refugees among a national population of less than 7 million, on the verge of collapse. The economic effects of COVID-19 have tipped the country to the threshold of anarchy, with the Prime Minister recently declaring that the country faces chaos. On 23 March this year, Kenya announced that it would close down its main refugee camps—Dadaab and Kakuma—potentially threatening to expel its nearly half a million refugees. It cited concerns with terrorism as the main reason, but many commentators speculated that the threat may also have been an attempt to elicit greater international assistance, at a time of economic contraction.

“the pandemic is undermining the survival strategies that refugees rely upon in camps and cities around the world, undercutting aid, remittances, and informal-sector jobs”

What we know from 2015-16 is that the rest of the world depends upon these frontline states to make refugee movements manageable. Without economically and politically viable refuge states, people are forced to move onwards—sometimes in large numbers. In 2015-16 hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees came to Europe not only because of the war in Syria but also because Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey struggled to host them. Millions of Syrians had been in those countries since 2011. The tipping point for onward movement came when those countries could no longer adequately protect and assist refugees. Those movements caught Europe by surprise, and the political fallout unleashed Brexit and populist nationalism across Europe.

Third, the pandemic is undermining the survival strategies that refugees rely upon in camps and cities around the world, undercutting aid, remittances, and informal-sector jobs. Bilateral donors have announced drastic cuts in development and humanitarian aid, and multilateral organisations report huge funding shortfalls. The World Bank shows how remittances, upon which refugees depend, have been cut globally by up to a fifth. And the Center for Global Development has shown how displaced people are disproportionately likely to work in the most hard-hit economic sectors. And what we know about refugees’ onward migration decisions suggests that socio-economic struggle may increase the likelihood of dangerous onward journeys to Europe and elsewhere.

The need for international cooperationThe paradox is that at a time of growing numbers and needs, rich countries are closing their doors. In the UK, for example, Home Secretary Priti Patel announced in March her New Plan for Immigration, proposing to limit the right of people to come directly to the UK and seek asylum. The UK is far from alone in both cutting overseas development aid (ODA) for refugees in low and middle-income countries and closing its borders to refugees.

“The key to avoiding another refugee crisis is international solidarity and development aid that benefits both refugees and host communities”

If rich countries wish to avert another global refugee crisis, however, they need to work together. Governments from Europe to North America need to recognise the interdependence between their support for refugee-hosting countries like Kenya and Lebanon, and the viability of the overall international refugee system. While the political temptation to close borders and cut ODA during a recession is immense, this approach not only risks undermining people’s access to fundamental rights but also fails to serve the national interests because it risks gutting the willingness and capacity of other refugee-hosting countries around the world.

The key to avoiding another refugee crisis is international solidarity and development aid that benefits both refugees and host communities in the major refugee-hosting countries around the world. In addition to humanitarian aid, major refugee-hosting regions need investment in jobs, education, and public services. But such approaches also need to complemented by keeping the door open to spontaneous arrival asylum and organised resettlement schemes, without which, countries such as Kenya and Lebanon will rightly ask why they should continue to host hundreds of thousands of refugees at a time of national crisis.

Featured image by Julie Ricard

The post The coming refugee crisis: how COVID-19 exacerbates forced displacement appeared first on OUPblog.

April 21, 2021

Going out on a limb

Etymologists traditionally deal with two situations. They may face an impenetrable word, approach its murky history from every direction, and fail to find a convincing solution (or even any solution: “origin unknow,” “the rest is unclear,” and the like). But equally often they deal with a group of words that seem to be related, and yet the nature of the relationship is hard or impossible to demonstrate. Demonstrate is a more appropriate term than prove since proof is a rare commodity in etymology. Such groups are particularly instructive to investigate. I have long been interested in a possible connection between limp (adjective), limp (verb), and lump. Limp1 and limp2 surfaced in English late (they did not exist even in the Middle period), but, judging by one old compound, the verb or the adjective was known in the language at least a thousand years ago. The compound limphalt “lame” (given here in modernized form: with regard to halt, compare the halt and the lame) does not make it clear which limp is meant, because “wanting in firmness, floppy” and “to walk lamely,” with regard to their references, are close.

To coin a word with the root l-mp was apparently easy. In the sixteenth century, English lump “to look sulky” appeared, and much later to lump at “to be displeased at something” turned up: a verb “of symbolic sound,” as The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology tells us. (Incidentally, dialectal English lump “to beat” also exists.) What is symbolic about lump? Sure enough, it rhymes with clump and slump (more about which anon, as they used to say in Shakespeare’s days), dump, grump (the root of grumpy), hump, plump, stump, thump, and trump “trumpet,” all of which seem to be expressive or sound–imitative. Is the assumption about lump “to be displeased” safe? This is an important question, because, if at least one English word pronounced lump is “symbolic,” can limp also be such?

Old English limpan meant “to happen; correspond, etc.” In the modern languages, we recognize this root in German glimpflich “mild”; g- is the remnant of the old prefix ge– (today, the German adjective is used mainly in the phrase glimpflich davonkommen “to come out unscathed”). On another grade of ablaut, Middle High German lampen “to hang loosely” seems to belong here (by the way, gilimpf was also said about things hanging down together). Amazingly, Sanskrit lámbate means “hangs down.” It is amazing because a word seemingly limited to West Germanic has such an exact counterpart in Sanskrit, bypassing Greek, Latin, and the entire Romance-speaking world.

Limping indeed! (Image © David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0.)

Limping indeed! (Image © David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0.)To be sure, if all such words are expressive (“symbolic”), they can be written off as examples of “primitive creation,” to which I often refer in connection with the almost forgotten but valuable works of the Swiss linguist Wilhelm Oehl (he called this process elementare Wortschöpfung). Once we agree that l-m-p is a root denoting things suspended, shaky, and the like, all our worries are at an end. To limp and the adjective limp will easily fall into the pattern. But haven’t we made a shortcut? Perhaps not.

Let us return to lump. German Lumpen means “rag” and is known to many from the word Lumpenproletariat “lower orders, impoverished and not interested in class struggle,” a pejorative term made popular around the world by Marx and Engels. Well, rags certainly “hang loosely.” A cognate of Lumpen, namely lomp “rag,” has been known in Dutch texts since the seventeenth century. According to at least one opinion worth considering, lump ~ lomp ~ lamp are nasalized forms of the root we can see in the Modern English noun lap, now remembered mainly from the noun lapel (whose formation and stress inspire nothing but surprise) and the phrase in the lap.

A limp limb may be a virtue. (Image by Tomqj, CC0.)

A limp limb may be a virtue. (Image by Tomqj, CC0.)Thus, lu-m-p seems to have emerged as a root with a nasal infix (m, like n, is indeed a nasal consonant). Such an infix is not a ghost conjured up for the sake of this essay. It appears in the formation of numerous Indo-European verbs and elsewhere. Some of the anthologized examples of n, now present now absent, are Latin vincere “to conquer” (compare English invincible), as opposed to its past participle victus (as in English victor, victory, victim, convict, evict, etc.), and winter, believed to be related to water and wet (an etymology always cited as an argument that the people who coined the word winter lived in a region with a moderate climate).

Those who expect the evidence of lap to supply a dazzling brilliance to the obscurity of lump (sorry for borrowing Dickens’s diction wholesale) will be disappointed. Indeed, lap has cognates all over Germanic and, quite probably, even in Greek. But an array of similar forms does not amount to an etymology, and we still wonder how lump ~ limp were coined. Lump reminds us of clump and clamp, whose so-called ultimate origin is also enveloped in darkness. Dutch klomp means “lump.” Surprisingly, most words being discussed here point to Low German (that is, northern) and Dutch. Perhaps they were indeed coined in that area and spread far and wide, but nearly all of them were recorded rather late, have a colloquial, sometimes even slangy tinge, and could have arisen at practically any time. In the sixteenth and the seventeenth century, the European languages adopted numerous colloquial words (mots populaires, as they are called in French), and their form returns us to the material that interested Wilhelm Oehl (primitive creation).

In the lap of luxury. (Image by Louis Hansel.)

In the lap of luxury. (Image by Louis Hansel.)Is, then, lump “symbolic”? Or, to ask this question in a different way: did people say lump, limp, klomp, and the like because those sound complexes evoked the idea of something unfastened, hanging freely, flapping, flopping, slapping, slipping, slopping, and so forth? Quite possibly so, even though it is hard or even impossible to explain the nature of the association. I tried to get help from the entry slump in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, and this is what I found: “Of symbolic origin, like clump, lump, plump.” Thus, plump, adjective and verb, also joins the club. The word is again from Middle Dutch. Incidentally, the great linguist Otto Jespersen thought that Latin plumbum “lead” (metal, “a word of obscure origin”) was sound-imitative: one throws a heavy piece of lead into the water, and it goes “plum” down. It would be worthwhile to discuss in this context the origin of limb (lim-b), but an additional paragraph will not add anything of substance to what has been said above, and I’ll dispense with it. Wherever we look, we find the same answer. Is closing the circle the name of the process?

Quite probably, the idea that limp, lump, clump, slump, and the rest are formations of onomatopoeic or sound-symbolic origin is correct, and I would like to repeat the suggestion I have often made in this blog. It appears that etymological dictionaries should combine two formats. Some words require serious discussion, bibliographical references, and all, while others should be lumped together in a longer entry, because they form a group, and their history becomes clearer when they are treated as a group. In a way, words are like people at work: each of us needs a CV, but not everyone deserves a biography.

Next week, I hope to address another group of the same type.

Olympus. Origin unknown. It has nothing to do with our story. Neither does galumph. (Image by Deensel, CC BY 2.0.)

Olympus. Origin unknown. It has nothing to do with our story. Neither does galumph. (Image by Deensel, CC BY 2.0.)The post Going out on a limb appeared first on OUPblog.

Putting transphobia in a different biblical context

Right-wing and reactionary forces in the USA and UK are once again stoking panic about trans people and practices of gender and sexual variation. Their arguments, though, rely upon faulty assumptions about gender, particularly in relation to history and religion. Such assumptions can be challenged by understanding that gender has never been fixed in the way they argue—neither today nor in the ancient context of the biblical texts often enlisted in so-called religious objections to trans and queer folks.

The relation of this past to our present is crucial. Roman imperial forces tried to dismiss, legislate, and mock people they considered to be gender-variant into even further marginalization. They used terms like “androgyne” and “eunuch” to classify people, and attempted to sort who they found acceptable, even virtuous, and who they found worthy of mockery and condemnation, and thus excluded from elite forms of family, authority, and inheritance. Biblical texts and communities repeated or resisted these assessments in a variety of ways, sometimes reinforcing Roman imperial stereotypes of these “scare figures” (at several points in Paul’s letters), sometimes conceding or just revealing that some gender-variant people were central to those communities (also in Paul’s letters, or in the famous “eunuchs” saying attributed to Jesus in Matthew 19:12).

Why might this matter to people now? These ancient and biblical efforts reflect a similar anxiety, as well as an accompanying knowledge that not everyone finds gender-variant people and practices to be a problem, then or now.

Today transphobic forces tell one kind of story, and have gained degrees of legal, cultural, and religious traction in the UK and USA. Late last year, the High Court of England and Wales constrained the kinds of medical care trans youth could access. This legal decision comes in the wake of orchestrated campaigns against the Gender Recognition Act in 2017, and a corresponding spike in hate crimes against British trans folks. People identifying as feminist have played large roles in these contexts, engaging in tired, if potent forms of fear-mongering, smearing trans people as “predators” in bathrooms, prisons, and sports.

Just this year in the USA, one influential extremist organization (designated as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center) has successfully directed regressive and reactionary legislation against trans youth in at least 20 states. Bills aiming to restrict transgender youth’s access to health care and school sport activities claim a similar rationale of “protecting” women and children, interwoven with claims about nature, time, and religious liberty. Even senators and congress members have echoed these talking points, targeting the first transgender federal official to be confirmed by the US Senate as well as the child of a fellow congresswoman.

“In both the past and the present, gender is neither a strict boundary, nor even a continuum, but better viewed as a constellation.”

The gender systems of the first and the twenty-first centuries are no doubt different from each other. The prevailing perspectives of the biblical past panicked about purportedly out of place women or unmanly males, within or besides growing populations of enslaved and conquered people. Yet, this anxiety and the resulting violence they directed against those they considered to be appalling bodies is not the whole story. The gospels and letters of the Christian bible show how their communities included a number of people from these groups, often in active and leading roles.

The question before us today, then, is: what lessons should we learn from this past?

The first is: gender and sexuality and embodiment have always been richer and more complicated than those who claim they have the one, stable, and clear view on them. In both the past and the present, gender is neither a strict boundary, nor even a continuum, but better viewed as a constellation. In the Roman imperial context, for example, people were seen as more than just male or female; only a rather select set of elite, free, imperially powerful citizen males counted as “men” (or viri, in Latin), with the vast majority of people functioning in a variety of ways as “un-men” (for lack of a better word).

The second and related lesson is that arguments about gendered threats often multiply the harms against already marginalized and stigmatized people. If your apparently feminist argument for protecting women targets people on the basis of their already marginalized gender, sexuality, or embodiment, then reconsider these politics in light of both our present gender constellations and longer histories and structures of harm. Right now trans and other gender nonconforming youth are far more regularly the targets, rather than the sources, of ongoing harassment, harm, and violence. In the USA, they report extraordinarily high rates of harassment (78%), physical assault (35%), and sexual violence (12%), leading at least 15% to leave school entirely.

“Religious texts and traditions have been, and still can be, a resource for how marginalized people can negotiate, survive, and even struggle against horrifying conditions.”

The third lesson is that the relationship of religion to gender, sexuality, and embodiment is also far richer and more complicated than certain, publicly predominant voices insist. It is not at all clear that biblical texts or communities would endorse the targeting of already vulnerable and stigmatized people. The lengths that Paul went to convince supposedly unruly women or unmanly males, and (or among) Gentile and enslaved members of these communities, to conform to his advice and arguments, demonstrate how vibrant and varied their gatherings were. The biblical past should haunt so many who claim to be acting in its name now.

Reactionary forces have been very successful at convincing people that to be Christian or even religious inevitably puts one in certain opposition to others, including feminist, trans, and queer people. One heart-breaking irony is that some claiming to be feminist have aligned themselves with the very reactionary groups that also seek to constrain and confine women. Another is that religious texts and traditions have been, and still can be, a resource for how marginalized people can negotiate, survive, and even struggle against horrifying conditions.

The history of trans rights and women’s rights and religious practices are themselves intertwined, not opposed. Some of the most exciting projects in religious and theological studies begin from this combination, from a constellation of genders, and from a commitment to counter rather than multiply the forms of harm facing trans and gender nonconforming people today.

Both the past and the present demonstrate how, in times of trans panic, appalling bodies matter more.

Featured image by Sharon McCutcheon

The post Putting transphobia in a different biblical context appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers