Oxford University Press's Blog, page 114

March 24, 2021

“Trash” and its synonyms from a strictly historical point of view (part one)

It is amazing how many words English has for things thrown away or looked upon as useless! The origin of some of them is transparent. Obviously, offal is something that falls off, but even this noun was borrowed from Dutch (and compare German Abfall). Other etymologies are more intricate. Litter started its life in English with the sense “portable couch.” Next, we find “straw for bedding” (hence “number of young brought forth at a birth,” i.e., “a litter of puppies, kittens, pigs”), and finally, “trash.” The ultimate source is medieval Latin lectus “bed,” recognizable from French lit. What a sad process of degradation! (In semantics, this process is called the deterioration of meaning; the amelioration of meaning is also known but occurs much more rarely, as is the way of all flesh.)

A litter, but certainly not trash. (Image via Unsplash)

A litter, but certainly not trash. (Image via Unsplash)Not all stories are so transparent. A case in point is trash, the subject of today’s blog post. This word surfaced in English only in the sixteenth century. The original OED did not commit itself to any etymology, though it did mention an array of similar Scandinavian words having approximately the same meaning. Borrowing from Scandinavian into Middle English goes back to a much earlier period, and that may be the reason James A. H. Murray, the OED’s first editor, showed such restraint. However, a few Scandinavian words did make their way into English (or into English texts, which is not the same!) relatively late. Be that as it may, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) removed the doubtful Scandinavian look-alikes and made do with the curt statement “of unknown origin”: safe but uninspiring.

Below, I’ll quote the entry trash from the latest (1911) edition of Walter W. Skeat’s A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language: “The original sense was bits of broken sticks found under trees…. Cf. Icel. tros rubbish, twigs used for fuel; Norw. tros fallen twigs, half-rotten branches easily broken; Swed. trasa, a rag, tatter, Swed. dial. trås, a heap of sticks. Derived from the Swed. slå i tras, to break in pieces, the same as Swed. slå i kras, to break in pieces; so that tr stands for kr, just as Icel. trani means a crane (see Crane).—Swed. krasa, Dan. krase, to crash, break; see Crash. Trash means ‘crashings,’ i. e. bits readily cracked off, dry twigs that break with a crash or snap.”

A crow and a crane, or sound imitation at its best. (Image via Unsplash, left + right)

A crow and a crane, or sound imitation at its best. (Image via Unsplash, left + right)In 1910, Skeat wrote a long article about the word trash, but his point was that alongside the noun trash “refuse,” the verb trash “to impede, hold back” exists, a word of French origin. That verb needn’t interest us here. Other than that, he stated without discussion that the noun is of Scandinavian provenance (his old point of view).

Long before the publication of The English Dialect Dictionary by Joseph Wright, a monumental work of perennial value, a correspondent to Notes and Queries (3/IX, 1866, p. 400) noted that in Suffolk truck means “odds and ends; miscellanea; rubbish.” A child “too fondly devoted to sweetmeats” is told not to eat “such nasty truck.” Is this another variant of trash? I doubt it but cannot offer any arguments for or against such an etymology. The Scandinavian hypothesis of the origin of trash looks attractive despite the late occurrence of the word in English texts, but why trash, rather than tras? Naturally, it has been suggested that the Scandinavian noun was influenced by Anglo-Norman, the version of French spoken in early medieval England.

Not out of Suffolk. (Image via Unsplash)

Not out of Suffolk. (Image via Unsplash)The tr- ~ kr (cr)- alternation to which Skeat referred causes no surprise, because bird names often have an imitative base: not only crane but also crow begins with kr-. Likewise, Russian ducks “say” kria-kria, not quack-quack. Variation in this sphere is always to be expected: the bird known as pe(e)wit in English is called kievit in Dutch and Kiebitz in German. If it is true that our story began with broken branches, an onomatopoeic basis of trash looks plausible. The initial group of crash certainly makes one think of a loud noise, as does, for example, br– in break and brittle or tr– in tread.

Skeat mentioned Icelandic tros “rubbish.” The source of the word is not improbably French trouse “baggage,” known to English speakers from trousseau. Therefore, English dross, dregs, dredge, and drudge are unrelated to it. The Icelandic synonyms of tros are trys and drasl. Tros turned up in books only in the eighteenth century, but trys is old. Returning to drasl, we note the deceptive variation tr– ~ dr-, as in tros ~ dross. Yet the words tras and drasl are not related and show how easy it is to arrive at the sense “trash, rubbish, refuse” from different sources.

Trash refers to what we throw away or what goes to waste, what is dismissed and discarded. Other kinds of “trash” are leftovers and lees, the remainder of the valuable part of an object. All kinds of “shavings” are also trash, so that the name for them may go back to various labor activities (such is, as we will see, probably the case of English trash). One expects words for “trash” to be “low” and therefore native, but since they often have a derogatory tinge, they travel widely from land to land, like other terms of abuse.

Judging by the facts at our disposal, the origin of English trash is not entirely “unknown.” Collecting twigs and branches was once an important activity. Those bits were collected by hook or by crook (see the post for 25 May 2016 on the origin of this idiom). In the Middle Ages and some time later, special regulations existed for appropriating such pieces of wood, because they constituted valuable “trash.” Trash probably did get its name from the crashing sound involved in breaking twigs and branches. The short word trash was easy to imitate and told its sound-imitative story (as it were). Therefore, or so it seems, speakers of Middle English took a fancy to it. Later, the loanword tras passed through many a French mouth, emerged as trash, and finally (in the sixteenth century), after many years of existing only in “popular speech” or regional English, turned up in texts.

Is this the origin of trash? (Image via Pixabay)

Is this the origin of trash? (Image via Pixabay)This reconstruction looks reasonable, but the closeness of such unrelated Icelandic synonyms for “trash” as tros and drasl invites caution. One draws the same conclusion from the coexistence of Russian musor and sor, two close but unrelated synonyms for “trash.” There is also busor, a regional doublet of musor, whose origin remains a matter of debate. Even though caution is an indispensable guide in all etymological research, in my opinion, its use should not be overdone.

Skeat always supplied the words in his dictionary with references to the source languages of the roots. I would like to suggest the following heading for the entry that interests us: “Trash (Scand.-French).” Perhaps our authoritative dictionaries will follow this recommendation. We’ll see: there is nowhere to hurry.

Feature image by Brian Yurasits

The post “Trash” and its synonyms from a strictly historical point of view (part one) appeared first on OUPblog.

The jurisdictional challenge of internet regulation

We live in an increasingly automated,>copyright spat between social media companies and the Australian government who wants social media companies to pay for the news content they reuse on their platforms without a license.

International co-operationThe second answer lies in international law and international co-operation between states. What the jurisdictional challenge has demonstrated more than anything else is the recognition that international co-operation is vital to deal with the challenges arising from technology. But states tend to act in self-interest and, again, progress is very slow, measured in decades rather than years. Furthermore, moral, cultural, and legal standards vary enormously between states, which makes law approximation undesirable.

Political citizenship“Regulation is not only legal (in the sense of legal compliance), more importantly it is about active, political citizenship.”

Therefore, the third answer is that lawyers have to pass the buck back to politics, and to some extent to computer scientists developing defensive technologies, such as better privacy enhancing and privacy preserving technologies. It is only through greater political awareness of the users of technologies, and active citizenship that these risks can be addressed. This awareness goes far beyond (passive) media literacy and education. Users need to recognize the pitfalls of using technology in particular ways and need to change behaviour in order to regain their agency. Regulation is not only legal (in the sense of legal compliance), more importantly it is about active, political citizenship. The concept of jurisdiction explains why the law cannot be the ultimate answer to regulating the>Internet Jurisdiction Law and Practice. Find out more and register here.

Featured image by TheDigitalArtist

The post The jurisdictional challenge of internet regulation appeared first on OUPblog.

March 23, 2021

The future of war and defence in Europe

We face a critical challenge: unless Europeans do far more for their own defence, Americans will be unable to defend them; but there can be no credible future defence of Europe without America!

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the shift of power from West to East, revealing a host of vulnerabilities in Europe’s defences and making major war in Europe again a possibility. The lessons of history? From D-Day to the creation and development of NATO, the importance of sufficient and legitimate military power has been at the heart of credible defence and deterrence, whilst shared innovation and technology have been critical to maintaining the unity of effort and purpose vital to upholding Europe’s freedoms.

However, Europeans now face a digital Dreadnought moment when strategy, capability, and technology could combine to create a decisive breakthrough in the technology and character of warfare—and not in Europe’s favour. The future of peace in Europe could well depend on the ability of Europeans and Americans to mount a credible defence and deterrence across a mosaic of hybrid war, cyber war, and hyper war. To remain credible, deterrence must thus reach across the conventional, digital, and nuclear spectrums. If not, Europe will remain vulnerable to digital decapitation and the imposed use of disruptive technologies.

The threatCritically, if the defence of Europe is to remain sound, both Europeans and their North American allies must squarely and honestly face the twin threat of hostile geopolitics and disruptive technologies, and they must do so together and with shared purpose:

Russia: Russian economic weakness and political instability allied to the overbearing cost of the Russian security state and its development of new weapons poses the greatest danger to European defence.Middle East and North Africa: state versus anti-state Salafist Jihadism and the impact of COVID-19 are exacerbating deep social and political instability across the region. The Syrian war has also enabled Russia to further weaken Europe’s already limited influence therein, with transatlantic cohesion further undermined by conflict over what to do with Iran and its nuclear programme.China: the rise of China is the biggest single geopolitical change factor; Europe’s nightmare is China and Russia working in tandem to weaken the US ability to assure Europe’s defence. US forces are stretched thin the world over and could render European defence incapable at a time and place of Beijing and Moscow’s choosing. The Belt and Road Initiative and the indebtedness of many European states to China is exacerbating both European weakness and transatlantic divisions.The dilemma“Could Europe alone defend Europe? No, and not for a long time to come.”

Can NATO defend Europe? Only if the Alliance is transformed; for if it fails, any ensuing war could rapidly descend into a war unlike any other. Europe must understand that if America is to provide the reinsurance for European defence, it is Europe who must provide the insurance. NATO is thus in the insurance business. It is also an essentially European institution that can only fulfil its defensive mission if Europe gives the Alliance the means and tools to maintain a minimum but credible deterrent.

Could Europe alone defend Europe? No, and not for a long time to come. Given post-COVID-19 economic pressures, the only way a truly European defence could be realized would be via an integrated EU-led European defence and a radical European strategic public–private sector partnership formed to properly harness the civ-tech revolution across Artificial Intelligence (AI), super-computing, hypersonic, and other technologies entering the battlespace. Can Europeans defence-innovate? They will need to.

The futureEurope must quit the comforting analogue of past US dependency and help create a digital and AI-enabled defence built on a new, more equitable, and more flexible transatlantic super-partnership. A super-partnership that is fashioned on the anvil of an information-led digital future defence against the stuff of future warfare: disinformation, destabilisation, disruption, deception, and destruction. A partnership which at its defence-strategic core has a new European future force able to operate to effect across air, sea, land, cyber, space, information, and knowledge.

The future of European defence is not just a military endeavour. COVID-19 has changed profoundly the challenge of defending Europe. It has also changed the assumptions upon which the transatlantic relationship has rested since 1945 and changed the relationship between the civil and military sectors—and even between peace and war. Therefore, Europe’s future defence will depend on a new dual-track strategy: the constant pursuit of dialogue between allies and adversaries together with a minimum but critical level of advanced military capability and capacity. Only a radical strategic public-private sector partnership that leverages emerging and disruptive technologies across the mega-trends of defence-strategic change will the democracies be able to defend themselves.

If not, then as Plato once reportedly said, “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

The post The future of war and defence in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

March 22, 2021

Disability, access, and the virtual conference

After my first Zoom meeting of the pandemic, I found myself lying on the bathroom floor with my noise-cancelling headphones on, on the verge of a full-blown meltdown. As an autistic person, I’ve always been hypersensitive to noise and to visual stimuli—but I hadn’t realized that a Zoom meeting with my colleagues could cause sensory overload. The number of images on the computer screen, the amount of movement in those tiny thumb-nail images, and the speed with which the images had moved, flashed, and changed—not to mention the obtrusive noise of malfunctioning microphones and noisy, socially-distanced households—had been enough to make me physically sick. Although many people tend to assume that an online event is automatically more accessible than an in-person event (after all, people can attend without leaving their homes), this isn’t always the case. Even when online events are more accessible, one of the lessons the pandemic has reminded me of is that the act of creating disability access can fundamentally change the nature of the thing that is accessed.

“Creating access for people with disabilities sometimes means fundamentally changing the nature of the thing that is made accessible”

In writing my new book, Shakespeare and Disability Studies, I was interested in exploring disability access as art and in exploring disability access as a complicated (and complicating) multifaceted phenomenon. Disability access is rarely just a question of “Can someone with X impairment use Y?” but rather more often a question of “If we modify Y so that someone with X impairment can use it, how does it change the meaning, the experience, and the effect of Y?” Creating access for people with disabilities sometimes means fundamentally changing the nature of the thing that is made accessible, whether the thing made accessible is a Shakespeare play (“the play’s the thing”) or a Zoom meeting. When we change the nature of the thing made accessible, we don’t just create access and inclusion for people with disabilities—we often create a new kind of experience altogether. I continue to be delighted and inspired by the innovative works, events, and objects we create (whether knowingly or inadvertently) when we create access for people with disabilities. Sometimes those new works, events, and objects bear a resemblance to the inaccessible version from which they grew. At other times, they do not.

Perhaps the most complex possibility, and the one most fundamentally counter-intuitive to a culture in which able-bodied and neurotypical (non-autistic) thinking are prioritized, is when creating accessibility not only fundamentally changes the nature of the thing made accessible but also causes attendees with a disability to lose something valuable. This seems counter-intuitive because stereotypical ways of thinking about disability have (falsely) taught us that disability experience does not include pleasure and that eliminating barriers to access is always an inherent and uncomplicated good. Neither of these things is true. For example, this year I’ll lead seminars at two Shakespeare conferences (the Shakespeare Association of America and the World Shakespeare Congress). Because of the pandemic, both conferences, for the first time ever, will be held completely online. However, these virtual events are more complicated for me than they originally seem, and their accessibility represents both gain and loss.

“I continue to be delighted and inspired by the innovative works, events, and objects we create (whether knowingly or inadvertently) when we create access for people with disabilities.”

In some ways, both conferences will be more accessible for me in an online format. Traveling can be difficult for some autistic people (keeping in mind the effect of Zoom on my body and mind, imagine the effect of a crowded airport). I usually travel annually to the Shakespeare Association of America—but with much ado. I can’t fly alone (nor hope to navigate unfamiliar city streets or crowded hotels by myself) and so always travel with a support person. My support person is usually another Shakespearean, a kind volunteer who, after weathering the sensory travails of the airport and public transportation, will spend the conference with me. I am not independent. But also, I am never alone. Everything in my life is shared. There is a certain beauty in that. After a busy day of seminars and panels, I will lie on the hotel room bed in the fetal position, far too worn out from the crowds and the noise to do anything else, and my support person and I will gossip together with great pleasure about the intellectual goings-on of the conference.

Disability, in our culture, is stereotyped as loss. Accessibility, in our culture, is deemed as always good, always a gain. It is also often misunderstood as simple and one-dimensional, as easy to understand and to explain. This year, for the first time ever, I will attend the Shakespeare Association of America without a support person. I will be independent. It is important, however, to think about the enormous cost of making the conference fully accessible to me. This act of access will fundamentally change the nature of what the conference is. The only way to make the conference fully accessible to me is for its social component, its travel component, its in-person component, to be completely removed. This represents a loss for all of the people at the conference and, ironically, also a loss for me. Because after my seminar at the 2021 Shakespeare Association of America, I won’t return to my hotel room to gossip about the intellectual goings-on of the conference with my support person. Rather, I will shut down my computer and reflect silently on the events of the conference… alone… for the first time in my life.

Featured image by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

The post Disability, access, and the virtual conference appeared first on OUPblog.

Victorian 3D: virtual adventures in the stereoscope

Armchair travel is more popular than ever today, making this an excellent time to explore a key moment in the history of home-bound travel. In the Victorian era, people used a stereoscope to launch themselves on virtual journeys to far-off lands from their own parlors. Users inserted a stereograph, twinned photos of a slightly discrepant image, into the device and then peeped into the eyepiece, where the image leaped into startling three dimensionality. The stereoscope created an immersive you-are-there illusion, a feeling that was pleasurable and even dizzying.

The stereoscope was actually invented as a scientific experiment. In 1832, Charles Wheatstone wanted to prove that human depth perception was a result of the distance between our two eyes. If this were the case, he hypothesized, then the eyes could be tricked into perceiving depth by each being presented with a slightly different two-dimensional image. The first stereoscope used two drawings, but scientists quickly realized that photographs—invented in 1839—could create an extraordinary illusionary effect within the stereoscope.

The lenticular stereoscope debuted at the 1851 Crystal Palace exhibition, where it was seen and admired by Queen Victoria. When she received a gift model, the ensuing craze provoked the sale of 250,000 viewers in three months. During the era of the “parlor stereoscope,” the device became a familiar fixture in Victorian homes, and stereographic photographs eventually numbered in the millions. (This massive output explains why you can still find stereographs at flea markets today, usually selling for a few dollars or pounds apiece). The stereoscope was called a “philosophical toy,” along with devices like the kaleidoscope and zoetrope: these were all entertaining, family-friendly commodities that were invented to demonstrate scientific principles of optics.

The Brewster Stereoscope, 1870. (Via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Brewster Stereoscope, 1870. (Via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)Stereographs depicted all genres of photography, from still-lifes to pornography. But the majority of stereographs depicted places, especially places where British people desired to travel. During the first wave of the stereoscope’s popularity, in the 1850s and 1860s, stereographs captured the romantic and picturesque destinations on Britain’s tourist track. These locations had actually been chosen well before the invention of photography. In the late eighteenth century, when the Napoleonic Wars closed off the Continent to British travelers, tourists went in search of “the picturesque” in the ruined abbeys and cathedrals across the UK and Ireland. The same spots that artists had previously canonized in picturesque paintings now became mass-produced views in the stereoscope.

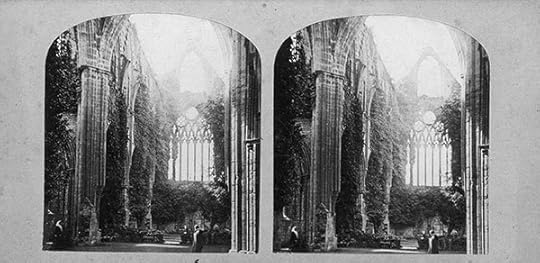

One of the most popular British stereoscopic destinations was Tintern Abbey, the ruined stony arches of rural Wales. William Wordsworth’s poem about the area had made the abbey into the foremost destination for adventurous travelers with Romantic sensibilities. Now stereoscope owners could use the device to travel virtually to the Gothic abbey, letting their eyes wander along ruined walls traced with ivy, or looking up at massive arches open to the sky. Although the stereoscope epitomized modern technology, with its lenses, optics, and photographic cards, the kinds of images that viewers consumed inside the stereoscope tended to look back into a romanticized history. (The images gave no indication, meanwhile, of the roaring iron factory near Tintern Abbey that disturbed visiting tourists). These details remind us that technology itself is not inherently oriented toward the future; in fact, new media often intermingle with old media, as new technologies enable nostalgic, fantastical journeys into the past.

Tintern Abbey. Stereographic photograph, c. 1850s. (Collection of the author.)

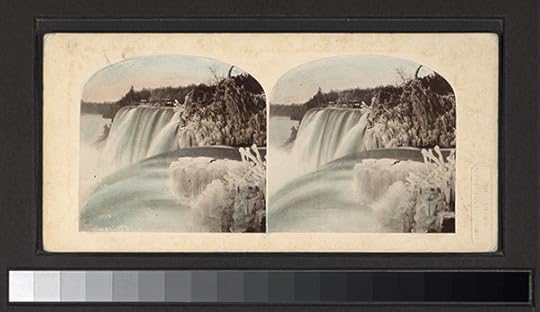

Tintern Abbey. Stereographic photograph, c. 1850s. (Collection of the author.)It was rare for stereographs to portray factories, crowded cities, or other mundane aspects of everyday nineteenth-century life. Instead, photographers captured scenes of picturesque beauty, old towns, peasants in “authentic” costume, churches, ruined castles, scenic landscapes. One popular set of images from beyond Britain was titled “America in the Stereoscope” (1857-59). While some of the scenes captured American cities like Boston and Washington, DC, most of the stereographs portrayed scenes of natural beauty—echoing the stereotypical British assumption that the former colonies were less cultured and more “primitive” than the UK. In fact, most of the American stereoscopic images portrayed waterfalls, from both the US and Canada, uniting both under the rubric of a nature-themed “New World.” Waterfalls were especially popular stereoscopic subjects because of their astonishing depth effects, as their rushing, blurred waters leaped out at the viewer. “America in the Stereoscope” featured at least ten different views of Niagara Falls and its environs. An 1861 London reviewer of the series wrote ecstatically: “The Horseshoe Fall [of Niagara] affords a good idea of the awful power of the mass of descending water; we can almost hear the deafening roar. The effect of viewing this little photograph in the stereoscope is to make one giddy.”

Stereograph of Niagara Falls. “American Fall, Niagara—Winter Scene.” 1859. (Via The New York Public Library, public domain)

Stereograph of Niagara Falls. “American Fall, Niagara—Winter Scene.” 1859. (Via The New York Public Library, public domain)Another extremely popular mid-century destination in the stereoscope was Egypt. Travel to Egypt was tremendously expensive, arduous, and beyond the reach of most nineteenth-century people. Hence Francis Frith’s 1857-59 series of views from Egypt met with resounding interest and acclaim, accompanying other forms of British “Egyptomania.” Frith’s images today seem starkly beautiful, with the Sphinx, pyramids, and ancient temples rendered in austere desert landscapes. Yet the realism of Frith’s photographic medium shouldn’t obscure some of the fantasies generated by the images, as they carefully omitted any signs of Egyptian modernity. In fact, Egypt was the site of numerous nineteenth-century imperial intrigues, and host to mingled cultures under European colonial influence. The stereoscope instead created an illusory Egypt, implicitly defining British modernity against the backdrop of an Egypt that seemed buried in the past.

Francis Frith, “Carved columns with archway, Egypt.” Stereographic photograph, 1856-7. J. (Via The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC BY 4.0)

Francis Frith, “Carved columns with archway, Egypt.” Stereographic photograph, 1856-7. J. (Via The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC BY 4.0)Many of the pleasures proffered by the Victorian stereoscope will seem familiar today. A popular twentieth-century inheritor of the stereoscope was the red plastic “Viewmaster,” whose cards animated 3D scenes of fairy tales or exotic destinations—a toy still being made, even though it’s been updated by virtual reality goggles. On YouTube, travel videos today boast of high-definition 4K streams, even while they avoid grimy, modern urban realities in favor of picturesque landscapes and ancient ruins. Cutting-edge technology continues to enable ever-more illusionistic spectacles of the past. The technology itself might have changed, but the fantasies that the technology helps to enable seem very long-lived, as we escape from our mundane, home-bound lives to stunning, faraway lands.

Featured image: Stereograph of Niagara Falls. “American Fall, Niagara—Winter Scene.” America in the Stereoscope Series, London Stereoscopic Company, 1859. (Via The New York Public Library, public domain)

The post Victorian 3D: virtual adventures in the stereoscope appeared first on OUPblog.

March 21, 2021

Why borders are built on ambiguity

During the nineteenth century, Britain, Canada, and the United States began to construct, in earnest, a border across the northern part of North America. They placed hundreds of markers across the 49th parallel and surveyed the land around them. Each government saw the border as a symbol of their sovereignty, a marker of belonging, and as the basic outline of their nation-states.

If the dreams of politicians were simple, the border’s implementation was not. None of the countries country possessed the manpower necessary to police such an extent. Nor had they developed dependable ways to control how immigrants and citizens understood their place on the continent.

The failure to enforce both the tangible and intangible aspects of the border created an abundance of problems. Canada and the United States required immigration to grow their nations, but they feared admitting individuals whose loyalty they could not trust.

The issue was with the process not the applicants. Those willing to immigrate had expressed a willingness to shift their loyalties and create lives outside of their country of birth through the act of immigration itself. The vagueness of federal policies only added to the concern. Poor wording and conflicting aims created an administrative system that faltered when presented with the complexities of everyday life.

In 1886, J.J. Elder left Ireland for Woodstock, British Columbia and then made his way south to the United States. He contemplated becoming a naturalized citizen but struggled with the implications. The naturalization process required he renounce his allegiance to Britain. He worried, however, that such a decision would limit his ability to visit family or to gain future employment in the British empire.

Unsure of what to do, Elder sent a letter to the American Undersecretary of State. He inquired whether it was legal for him to renounce forever his allegiance to Britain if he thought he might need to renew that allegiance at a later date.

Like many important border issues, Elder’s question had no clear answer. The official he spoke to could think of no policy that governed such a decision. If the absence of any formal guidance, he believed that if Elder wished to make an oath he later intended to break it was a matter of conscience not law.

“Administrators measured the border’s power in terms of confiscations made, entries denied, and fines accessed. Everyday people … measured the border in cost, discomfort, friendships, and family.”

Temporary allegiance and legal uncertainty ensured that ambiguity remained a constant part of life. As Elder’s case, and hundreds like it suggested, making the border meaningful required both new laws and endless clarification.

By the 1930s, the infrastructure that made the border visible had grown. Thousands of federal officials now guarded ports of entry and permanent agencies governed much of the border’s operations. For all that had changed, the underlying uncertainties remained similar. Federal governments created borders but had failed to monopolize their meaning. The pervasiveness of social and economic connections ensured that the behaviors of everyday people governed the ways borders operated.

Administrators measured the border’s power in terms of confiscations made, entries denied, and fines accessed. Everyday people understood it differently. They measured the border in cost, discomfort, friendships, and family. They measured it in the insults their children faced and in the heartaches it created. Inconsistencies in policy and enforcement had created a border that seemed inescapable in one moment, only to seem forgettable in the next.

Josephine Grondahl moved to Canada as a child in the early twentieth century. Like many others, she first experienced the border as a barrier to friendships, rather than to movement. When she started attending a new school in Canada, the other children bullied her heavily. Her use of American terms for paper and boots (“writing tablet” and “overshoes”) instead of the local lingo (“scribblers” and “galoshes”) set her apart. Decades later, the bullying remained fresh in her mind. She felt the border’s sting first from her classmates, not from the customs and immigration agents that each government invested so heavily into.

As Grondahl and Elder’s experience suggested, the ambiguity of borders could not be resolved with more guards or more laws. Social practices and family connections mattered just as much to the ways individuals defined themselves as national borders did. In that context, border guards possessed only partial control over a world fill with motion and complexity.

Today, border guards use infrared cameras, facial recognition software, and unmanned drones to guard ports of entry. New technologies have amplified the kinds of surveillance possible but have created new gaps at the same time. Virtual private networks allow Canadians to mask their location in order to gain access to online streaming services meant for American eyes only. Old problems remain unabated. In 2020, American vacationers began to exploit transit rules to avoid pandemic restrictions. They claimed to be travelling to Alaska in order to sneak across the border to vacation in Vancouver instead. The approach was an old one, one that residents from both countries had used for more than a hundred years.

For both historic and contemporary communities in North America, attempts to create a meaningful border have faced the same problem. Creating hard boundaries requires assigning a binary (Canadian or American) to a spectrum of identities and people. As the past hundred years has shown, the problem cannot be solved by either advances in technology or the addition of thousands of pages of laws, policies, and regulation. The problem is inherent in borders themselves. By their very nature, borders create ambiguity because they overlay simple lines across a world that is impossibly complex.

Featured image by Jim Witkowski via unsplash

The post Why borders are built on ambiguity appeared first on OUPblog.

March 20, 2021

To know Russia, you really have to understand 1837

The assertion might seem strange. Even among historians of Russia, it is likely to produce head-scratching rather than nods of knowing approval. Most would point to other years—1613 and the birth of the Romanov dynasty; 1861 and the end of Russian serfdom; 1917 and the Bolshevik seizure of power—as more consequential. But in fact 1837 was pivotal for the country’s entry into the modern age and for defining many of Russia’s core attributes. Russia is what it is today, in no small measure, because of 1837.

The catalogue of the year’s noteworthy occurrences extends from realms of culture, religion, and ideas to those of empire, politics, and industry. From the romantic death of Russia’s greatest poet Alexander Pushkin in January to a colossal fire at the Winter Palace in December, Russia experienced much that was astonishing in 1837: the railway and provincial press appeared, Russian opera made its debut, Orthodoxy pushed westward, the first Romanov visited Siberia—and much else besides.

Take the death of Pushkin. Already acknowledged as Russia’s leading poet as 1837 began, Pushkin nonetheless secured his place in the Russian literary pantheon by the manner of his death: a duel precipitated by the romantic attentions of a Frenchman in Russian service to his wife Natalia. Extending over several months before the fateful day in late January, the drama and intrigue were intense. They implicated not just the poet and his family, but also diplomats, Russia’s secret police, other literary figures, and the emperor himself. Fatally wounded at a snowy clearing on the outskirts of Petersburg, Pushkin suffered in agony for two days before expiring as crowds gathered to express their sympathy. Though it took time for a full-blown cult of Pushkin to develop, its foundation was here, and it became a resource for tsarist, Soviet, and post-Soviet regimes to forge national and imperial unity. Pushkin became “our everything,” in the words of a literary critic in 1859, and the tsarist government sought by the 1860s to incorporate his image into the national pantheon. The centenary of his birth in 1899 became likewise an official affair, with new efforts to draw Russian literature into official culture. The cententary of his death allowed Stalin to exploit the cult even in the midst of the Great Terror. By the late Soviet era, the intelligentsia would contend, “Pushkin as a phenomenom is obligatory for us.” Modern Russia is inconceivable without the cult of Pushkin, and 1837 was central to its creation.

“Modern Russia is inconceivable without the cult of Pushkin, and 1837 was central to its creation.”

That same year saw an extraordinary trip by the heir to the throne, the future Alexander II, across nearly 20,000 kilometers of Russian territory. Visiting towns and villages across Russia and becoming the first member of the reigning Romanov dynasty to visit Siberia, Grand Prince Alexander Nikolaevich made a stunning impression on diverse subjects of the empire, Russians and non-Russians alike. An emerging periodical press followed his every move and made him the principal news item for many days across months. The trip accordingly permitted not only the heir himself, but also readers of the press to discover Russia’s provinces in all their diversity. The travel also laid foundations for his future rule, which among other things ended serfdom in Russia. But it was the prospect of actually seeing the young prince that was most intoxicating. Immense crowds gathered to catch a glimpse of the heir, who became the day’s principal celebrity. For many people in diverse parts of Russia, 1837 was unforgettable because they had seen the tsarevich in the flesh.

Still, arguably the most dramatic event of 1837 was the destruction of the Winter Palace in a colossal fire. Indeed this palace, one of Europe’s largest and a key edifice for the Romanov monarchy, occupied a central place in the imperial capital of St Petersburg and in emerging conceptions of the Russian nation. Its destruction was not just a material loss, but a deeply symbolic one representing an ideological challenge in an age of revolution. The monarchy therefore undertook a campaign to shape the narrative of the palace’s destruction, including also an effort to shape foreign opinion. Most shocking of all was the intention to reconstruct the palace entirely within 15 months. Amazingly, this goal was accomplished. The famous Hermitage State Museum, boasting one of the world’s greatest collections of art, is housed precisely in this reconstructed Winter Palace, a product of 1837.

These episodes only begin to account for the dynamism and consequence of Russia in 1837. The cumulative effect was profound. The country’s integration accelerated, and a Russian nation began to emerge within the larger empire, embodied in new institutions and practices—from opera and poetry to newspapers and palaces. The result was a quiet revolution, after which Russia would never be the same.

Featured image: Vasily Andreevich Tropinin, Portrait of Alexander Pushkin. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post To know Russia, you really have to understand 1837 appeared first on OUPblog.

March 19, 2021

Family secrets and the demise of Erard pianos and harps

Musicians from Haydn to Liszt were captivated by the rich tone and mechanical refinement of the pianos and harps invented by Sébastien Erard, whose firm dominated nineteenth-century musical life. Erard was the first piano builder in France to prioritise the grand piano model, a crucial step towards creating a modern pianistic sonority. His 1822 invention of the double-escapement action allowed pianists to repeat notes more rapidly and improved the instrument’s response while at the same time producing a more powerful sound. This invention was adopted or imitated by many subsequent builders, thus revolutionising both piano construction and repertoire. From that moment on, the speed at which pianists could repeat notes was limited only by their own technique. The virtuosic repertoire of the romantic era would have been unthinkable without this invention.

Sébastien’s innovative spirit was kept alive by his nephew Pierre, whose own inventions and shrewd marketing sense assured the superiority of Erard at virtually every international exhibition. After Pierre’s death, however, the direction of the firm passed to his widow Camille, but neither she nor the trusted managers who assisted her were inventors. The Erard firm thus experienced a steady decline, unable to compete with foreign builders such as Steinway, Bechstein, and Blüthner.

Many great instrument-making families, from the Amatis and Guarneris to the Broadwoods, were dynastic, allowing them to transmit their trademark techniques from one generation to another. For this reason, the abrupt end of the Erard line was remarked upon even in the nineteenth century. In the 1860s, for example, when Steinway led the American onslaught against the old-world piano makers, one French critic opined: “Oh! Pierre Erard, where are you? You would never have backed down in the face of American antagonists! In your shroud of stone, you must be trembling with shame, faced with the spinelessness of the masters of old-world craftsmanship, who seem to be declaring defeat without even having fought.”

Erard had been a family enterprise. Pierre’s uncle Sébastien and his father Jean-Baptiste had founded and directed the business, and two of their nieces ran the music publishing wing. Pierre understood that the workers he trained would never be as motivated as a member of his family to invest their efforts and capital in the firm. In his voluminous correspondence, he repeatedly expressed his fears for the future of the enterprise, which makes it all the more surprising that he never founded a family of his own to prepare a successor. For years he reassured his father and uncle that matrimonial prospects were on the horizon, but always found excuses about being too busy to pursue his plans. He finally got married, late in life, to one of his cousins, but the couple never had any children, and there is not even the slightest mention of a pregnancy in the extensive and frank correspondence that Pierre’s wife maintained with her mother and sister.

The reason behind Pierre’s perplexing reluctance to start a family may lie in a secret that would have remained unknown were it not for the record-keeping zeal of the nineteenth-century Paris police force: he was homosexual. In the 1840s the Paris police began keeping detailed records of the homosexual activities of famous men: ministers, diplomats and senior officials, aristocrats, priests, actors, doctors, and businessmen. In a recently discovered ledger entitled “pederasts” we find the notes the police informants took on Pierre Erard, who was observed frequenting a brothel where young male prostitutes were procured for wealthy customers.

Throughout history, homosexual men and women have married and had children. Moreover, even if Pierre had had children it is not sure that they would have continued the family business or would have inherited their father’s innovative drive, patenting inventions that would be embraced by the world’s leading pianists. Nevertheless, Pierre’s hidden sexual orientation may well have been a factor that contributed to the demise of the family business, and one cannot help but speculate as to what impact at least one more generation of Erards would have had on the course of instrument-making and music history.

Featured image by weinstock

The post Family secrets and the demise of Erard pianos and harps appeared first on OUPblog.

March 18, 2021

How well do you know these literary classics by women? [Quiz]

Test your knowledge of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary classics penned by women! To best celebrate Women’s History Month and the online launch of the Oxford World’s Classics, discover just how much you know about these female-authored literary classics, or add some recommendations to your ever-growing reading list. Find out now with our quiz!

Featured image by freestocks

The post How well do you know these literary classics by women? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]March 17, 2021

The future is in the past

Two weeks ago, I attempted to tie etymology to the most pressing problem of our time (see the post for 3 March 2021 on imps and vaccination). Now that woke and cancel culture have become the words of the day, I again saw my chance and decided to deal with the adverb yesterday. In yesterday, only yester– will interest us.

Not everybody may know that yesterday is one of the most enigmatic formations in the Indo-European language family. On the face of it, everything looks fine, because cognates are not wanting: Dutch gistern, German gestern, Latin heri “yesterday” ~ hesternus “yesterday’s, pertaining to yesterday” (the second Latin word needs no explanation; heri goes back to hesi), and many others. (English y- in yester– developed from g-.) Gothic, a fourth-century Germanic language, had gistra-dagis, an almost exact counterpart of yester-day. The Gothic Bible is a translation from Greek, but the Greek word gistradagis glossed was aûrion “tomorrow” (not “yesterday”!), and herein lies the main trouble.

The Gothic bishop Wulfila, a talented and most reliable translator, must have known very well what the Greek word meant. The context, with its juxtaposition, is also unambiguous: “…the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast in the oven” (M VI: 30; the text and the spelling are as in the Revised Version). Even a non-specialist will notice the similarity between aûrion and Aurora, while those versed in historical linguistics will recall that English east is related to it (morning, or tomorrow, comes from the east). No doubt, gistra-dagis meant “tomorrow” in this Gothic verse.

Tomorrow is cast in the oven. (Via Unsplash)

Tomorrow is cast in the oven. (Via Unsplash)How could it be? The plot thickens, for the Gothic case is not isolated. Those who are familiar with some modern Scandinavian language may remember Swedish i går “yesterday” or a similar form in Norwegian and Danish. The older version of this phrase also turned up in Old Icelandic, and it usually meant “yesterday” (as expected), but in a few isolated cases, including one in a well-known poem, the sense is “tomorrow.” The Icelandic phrase (í gær) had a long vowel in the root (the ligature æ always denoted a long vowel). Gær is related to gistra- (I’ll skip the details).

The ancient form gester– (as in English yester-) seems to contain the root ges– and the suffix –ter, with ges-, in turn, being made up of a prefix (g-) and some root like djes– “day.” By the time the word yester(day) and its cognates appeared in our manuscripts, its ancient inner structure must have been as obscure to the speakers as it is to us. The ancient phonetic shape of the initial prefix g- remains an object of rather fruitless speculation and need not interest us. We want to know how the same word could acquire two incompatible senses: “yesterday” and “tomorrow.”

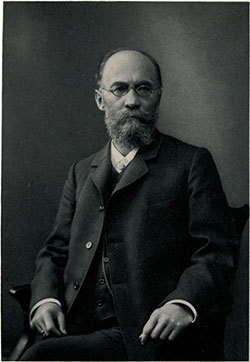

Karl Brugmann (Via Wikimedia Commons)

Karl Brugmann (Via Wikimedia Commons)The riddle has never been solved to everybody’s satisfaction. More than a hundred years ago, the great historical linguist Karl Brugmann suggested that the Germanic adverb meant “the day next to the present one,” with the context determining the reference. Perhaps his explanation, which is a restatement of the obvious fact rather than an explanation, can be improved. Didn’t the speakers of Old Germanic need more precise names for the day gone and the day to come? We may, I believe, approach the truth if we consider some of our ancestors’ views on time. Note that, unlike Greek and Latin, Germanic had no future tense. The present did all the work, as it still does in such English constructions as if you feel better tomorrow; when you return, give me a call, and I am leaving in two days. While reading a text in an old Germanic language, one often has to figure out whether the reference is to the present or the future. Prophecies obviously refer to the future, but not all situations are so clear.

In such matters, it is useful to step aside for a moment from the facts of language and take into consideration people’s oldest concepts of time. The ancient Greeks believed that the future was open to view (because it was in front of us), whereas the past remained hidden (no one can see what is behind). Another seemingly unexpected picture emerges from Old Russian chronicles. The Germanic noun kuningaz “king” made its way into Old Slavic and became knyaz’ in Russian, rendered in Latin as princeps and in English and German as prince ~ Prinz. Old Russian historical books mention numerous princes. Those who reigned in the distant past are called front princes (perednie knyaz’ia), and those who came after them are referred to as back princes (zadnie knyaz’ia). Shouldn’t it have been the other way around? Apparently, not: the rulers of the most distant past were at the front because everything began with them: the chronicler viewed history with the eyes of their characters, not with those of his contemporaries. Both examples show that the early ideas of time and its progress might differ from ours in a rather radical way.

Where is the front, and where is the back? (Via Wikimedia Commons)

Where is the front, and where is the back? (Via Wikimedia Commons)I would like to suggest that for the oldest Germanic speakers, who did (and did very well!) without the future tense, the concept of and hence the word for tomorrow did not exist. The same was probably true of all the most ancient Indo-Europeans, who originally had no tenses but only grammatical aspects: they could describe the way this or that action was performed, divorced from the temporal framework. This approach is easy to understand. Both I have put the butter into the refrigerator, and I put the butter into the refrigerator refer to the past but characterize the past moment from a different perspective. In similar fashion, I speak and I am speaking refer to the present but also from different viewpoints. Given this picture of the world, adverbs of time are not always needed or, if they exist, their message is less precise than we expect. The Old Germanic languages developed the past tense and, predictably, an adverb like yesterday. Tomorrow and other references to the day after (and this is the core of my hypothesis) emerged later, perhaps much later.

If my suggestion is correct, for many centuries, yesterday (the same of course holds for its closest cognates) meant what they still mean to us and nothing else. Under the circumstances, it could occasionally become a default name for “any day next to the present one, an adjoining day.” Judging by the extreme rarity of the sense “tomorrow,” this usage struck the speakers of Germanic as inconvenient, perhaps even unnatural. Since in the extant Gothic text, gistradagis occurs only once, we cannot judge how common it was in Wulfila’s language. Not inconceivably, pressed for an exact gloss (the Greek adverb made him do so), he used the word for “the day passed” and assumed that his readers would understand the reference from the context. They, most probably, did. One wonders how Wulfila would have translated Macbeth’s tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. (A postscript: yore in the phrase in days of yore is not related to yesterday.)

The title of this post (“the future in the past”) refers to constructions like “I knew that they would do well”: would, not will, because the future is viewed from the vantage point of the past. Odd, isn’t it? Our modern concepts of time and tense would probably have puzzled Wulfila no less than his gistradagis puzzles us.

Featured image by Olya Kobruseva

The post The future is in the past appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers