Oxford University Press's Blog, page 118

February 12, 2021

The evolution of women’s love lives: a timeline

Reaching from the middle of the twentieth century, when little girls dreamed of Prince Charming and Disney’s Cinderella graced movie screens, Carol Dyhouse charts the transformation of women’s love lives against radical social changes such as the passage of the Equal Pay Act, the acceleration of technological advancement, and improved access to contraception, bringing us up to the 2013 release of Frozen. How did the narrative change from a reliance upon being saved by Mr Right to an empowered message of sisterly love coming to the rescue?

The post The evolution of women’s love lives: a timeline appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting Domesday done: a new interpretation of William the Conqueror’s survey

A new interpretation of the Domesday survey, the famous survey of England taken on the orders of William the Conqueror in 1086, has emerged from a major study of the survey’s earliest surviving manuscript. It is now clear that the survey was more even more efficient, complex, and sophisticated than previously supposed. The first draft of the survey was made with astonishing speed—in about 100 days—and the information it contained was then checked and reorganised in three further stages, each resulting in the creation of new documents carefully designed for specific fiscal and political purposes. The iconic Domesday Book was simply one of several important outputs from the process.

This interpretation has emerged from a major collaborative study of Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3500, aka Exon Domesday. Although this survives in an incomplete form and covers only part of the kingdom (Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall), Exon Domesday is priceless because it is the earliest manuscript of the survey to survive in its original form, and contains several different types of text, written by about two dozen scribes in the summer of 1086. A team of specialists led by scholars based at King’s College London and Oxford University has recently completed a detailed study of these scribes, establishing precisely what they wrote and how they collaborated; and when placed alongside the other surviving manuscripts and records of the survey, this new evidence affords a deeper understanding of how and why Domesday was made.

The suggestion is that the first draft of the survey was made between Christmas 1085 and the following Easter, which fell on5 April 1086. This was organised on a geographical plan and was intended to improve yields from the land tax known as the “geld,” which was paid by lesser landholders, subtenants, and peasant farmers. Indeed, a major levy of the geld was collected and accounted for in tandem with the survey. The text of the survey was then checked in dramatic, widely attended meetings of shire courts between Easter and Whitsun (25 May), generating lists of contested landholdings from which the king could generate political as well as financial capital in later judicial hearings (rulers routinely profited from justice in this period). The geld accounts were also publicly checked at the same meetings: Exon uniquely contains a series of accounts relating to this exercise, and astonishingly these reveal that 96% of the money demanded from taxpayers was collected.

Between Whitsun and 1 August, the survey was then reorganised on a feudal plan, creating documents known as “fiefs,” which listed the lands of barons—that is, major landholders who held land directly from the king—under separate headings. Statistical summaries of each fief were also made as they came off the production line. Exon Domesday is the only surviving manuscript witness to this stage of the survey. It reveals a team of scribes working under intense pressure and collaborating in ingeniously pragmatic ways to get the job done. They had to finish before 1 August, because on that day an extraordinary ritual occurred: the king required all the barons in the kingdom to perform homage to him, presumably in return for the lands recorded in the survey.

The feudally-arranged draft of the survey and the summaries combined to create a comprehensive inventory of the king’s own estates, which recorded how much revenue they were expected to generate for the king and made those responsible for managing them more accountable. They also created the potential for the king to generate feudal taxation by extracting large sums of money from barons each time their property changed hands, e.g., through inheritance or marriage. The barons complied with the whole exercise partly because they also got something precious in return: unambiguous confirmation of title to the land they held from the king.

“This was arguably the first systematic use of big data in British history.”

However, further editorial work remained necessary to make the material more accessible and user-friendly for treasury officials. In the autumn of 1086, another group of scribes collaborated to make a fair copy of a document similar to Exon relating to Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex: this manuscript is known as the Little Domesday Book. Meanwhile, a single scribe who possessed a remarkable talent for organisation and concision spent about a year compressing the material in Exon and similar records for other parts of the kingdom into a single document: this manuscript is known as the Great Domesday Book. These documents were furnished with contents lists, running headers, and coloured rubrics, and were carefully designed to enhance the administration of royal estates and feudal taxation.

In short, the survey was brilliantly conceived to create information structured in specific ways to allow the Conqueror’s officials to maximise his revenues from different income streams. That is to say, the survey was compiled in a similar way to modern databases, into which data can be entered in one format and extracted in other formats for specific purposes. The Conqueror’s regime effectively compiled and manipulated a database of England’s landed wealth in about seven months using technologies no more complex than parchment, pen, ink, and human interaction. This was arguably the first systematic use of big data in British history.

Historians have been arguing for some time that the Normans inherited an unusually powerful state when they conquered England in 1066. Even so, this new evidence demonstrates how effectively the Normans mastered the machinery of the English state and adapted it to the distinctive challenges of governing newly-conquered England. It also establishes that they did so by drawing on ideas, technologies, and personnel that originated from the Continent, for the closest parallels to the Domesday are the great surveys compiled in the reign of Emperor Charlemagne and his successors in the eighth and ninth centuries, along with confirmation charters that were commonly issued in northern France in the eleventh century. The new research also indicates that the Exon scribes were trained in northern France. The Domesday survey was therefore a distinctively English yet fundamentally European phenomenon.

These new findings may resonate at a time when the coronavirus pandemic and Brexit have placed intense demands on the machinery of the state and public participation in its strategies.

Feature image by Ben Griepenstroh

The post Getting Domesday done: a new interpretation of William the Conqueror’s survey appeared first on OUPblog.

February 11, 2021

The ruins of the post-Covid city—and the essential task of rebuilding

The visible ruins of our cities have often been in neighborhoods distant from the vital central areas where people shop, go to cultural events, and gather in restaurants. In these central areas, a vacant store here and there is considered temporary—a matter of weeks or months perhaps— part of the natural ebb and flow of the city’s culture and economy. The expectation is that a replacement will arrive soon enough and rent-values will remain more or less stable. These assumptions and expectations may all become obsolete, with little relevance to our futures in the post-COVID-19 world.

We are in the midst of a Covid economy that has decimated the cities of America, with similar effects around the globe. The ability of cultural institutions, retail stores, and restaurants—which traffic in real, not virtual, people—to survive this assault cannot be assumed. In fact, many restaurants despite a variety of inventive strategies, such as”Cocktails-to-go” and “bake-at-home cookies”, have had to shut off the gas and lock the door. Streets once filled with bustling retail stores now seem like ghost towns, in the face of increased Covid e-shopping. Performance groups—dance, music, theater—and their material houses, may have a slightly stronger institutional survival plan, given their governing boards and donors, but personnel have been without work for nearly a year, even as they must stay in shape in order to maintain their presence when things do open up again. Can we even assume that the world “outside” will remain attractive, after this long habituation to the reclusive pleasures of home entertainment? What might the effects of diminished attendance be on fragile arts and performance groups?

There are many unknowns ahead of us, and meanwhile the slow cascade of business failures continues steadily. While those lucky enough to be working from home have been doing OK—psychological costs aside—those who depend on an audience or “real” people, have been suffering most. Where will the capital and initiative to open new businesses come from after we tame the virus? We face not only the loss of a cohort of performers and restauranteurs, but the loss of the younger people they would normally be training.

The ripple effect of the Covid economy is already visible in the material fabric of our inner cities. Walking down streets that show the signs of desertion and retreat, empty shops and restaurants, we can’t know how long it will be before life as we knew it might return. And what about the inner city office buildings, where companies are discovering they may not need quite as much square-footage in real-estate as they once assumed, that many jobs can be sustained by working at-home. As office buildings increase their vacancies, as mortgages fall due, we may begin to see yet another delayed effect of Covid, visible in decaying and deserted buildings that have housed a sector of the economy that on paper is doing well right now.

The ruins of the city in the post-Covid economy will change the urban experience in fundamental ways, diminishing density and therefore the liveliness of the inner city. Abandoned shopfronts are already becoming the new blight of the city. We have been right to worry about the terrible (and to some extent avoidable) loss of lives, the sickness and suffering, the devastation of families. But we also need to look beyond—hopefully in a post-Covid world of vaccination and sustainable health—to the physical structures that have defined our cities and that are becoming emblematic ruins of the past year.

Anticipating these needs is essential, and it is the responsibility of cities to create task forces to analyze the best ways of restoring the material remains of our urban areas, before they become the literal ruins of the future. We have been rebuilding ruined cities in the United States since the Civil War, cities that have sustained the brutal destructions of war; or the collapsing walls produced by earthquakes, floods, fires; or the catastrophic loss of industries that have been driven to new (and cheaper) labor markets. These efforts at rebuilding have been successful when the civic spirit is determined and optimistic, willing to invest labor and money.

The post-Covid ruins will be subtler, but persistent and visible. Unlike a flood or conflagration, which creates universal woe, the post-Covid city will have divided its suffering unequally–some wiped out, unable to start again, others riding a wave of economic security. But even those with healthy stock portfolios may find themselves walking the streets of a seriously damaged city.

It’s essential for us all to recognize that we’re in this together and to support local and national efforts to rebuild, on the basis of a unified public consciousness that has been markedly absent from our divided nation in recent years. Cities and states will need to gather intellectual forces and incentives, but the Federal government will have an equally important role in providing funding and the expertise needed to support the private market during these years of planning and rebuilding.

The first step is to identify the problem and name it as a cause, making it a “thing” to be anticipated. We might call it: Rebuild Urban Infrastructure Now—with the acronym starkly reminding us what the alternative is. If we want to live in a post-Covid future with lively public spaces and a sense of community, we will need to invest locally, unglue ourselves from the screen, and rediscover the pleasures of human society.

Featured image by 5chw4r7z – Downtown scenes from a pandemic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The post The ruins of the post-Covid city—and the essential task of rebuilding appeared first on OUPblog.

February 10, 2021

“Gig” and its kin

I received a query from my colleague, who asked me what I think about a possible tie between Sheela na gig and the English word gig. A detailed answer would have taken up all the space allotted to my monthly gleanings. Therefore, I decided to devote a special post to it. In the nearest future, I’ll do the same with a few other questions from our readers.

Sheela na gig is the name given to carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. Such carvings appear on many churches in Ireland and elsewhere in Western Europe (but mainly in Ireland). I ran into some of the literature on these images several decades ago, while studying the Freydís episode in the Old Icelandic Saga of Erik the Red. (Most people know it from a TV show.) That courageous woman confronted a group of belligerent natives and bared her breasts. Her gesture made the enemies flee. I could not understand why a band of able-bodied men ran away from a semi-naked woman, rather than attacking her with reinforced vigor. Later, I read many works on the apotropaic role of nakedness, ithyphallic figures, and many other things connected with fertility cults, taboos, ritual obscenities, a mixture of pagan and Christian customs, and so forth. Therefore, Sheela na gig no longer surprises me. However, Irish antiquities are not my area, and I have no independent opinion about those carvings.

Sheela na gig. (Image by Brian Robert Marshall,

Sheela na gig. (Image by Brian Robert Marshall, It seems almost certain that the name given to the carving is late, and I believe that those scholars are right who detect an obscene meaning in gig (Sheela must be a proper name). Whether gig in this phrase is Irish is not very important. It pays off to look at the English words of the same structure. Over the centuries, English gig has been recorded with the following senses: “a flighty girl,” “whipping top,” “whim,” “fun,” “odd person,” “fool,” and “a one-horse carriage” (see such a carriage in the header). Those senses probably appeared independently of one another and have been referred by etymologists to the idea of light or quick movement. All gigs (as it were) are “flighty.”

A reinforced, emphatic variant of gig is jig. (Think not only of the dance but also about the jigsaw.) Its French analogs mean the same. The origin of jig is said to be unknown, but I wonder what one is supposed to “know” about jig and its variants. After all, unless words derive from proper names or obvious onomatopoeic complexes, they are believed to go back to some ancient or comparatively recent “roots.” Here then is the root: gig ~ jig “quick movement”! Some such English words may have been borrowed, because the syllable means almost the same in several languages. The fact that gig “a temporary job” arose among jazz musicians reinforces the reference to the idea of “light, brisk movement.”

Predictably, gag is another word of questionable antecedents. The g-g and j-g syllables appear with various vowels in the middle. Jog has been recorded with the variant jag and jug(gle). We learn from the OED that all those verbs don’t antedate the Middle English period, that they are “symbolical of stabbing or jerking movement,” and that they were not common before the sixteenth century. Their checkered history need not surprise us. Who could have predicted the relatively recent worldwide popularity of the verb jog?! A variant of jog– is gog– in goggle, “expressive of oscillating movement,” we are told. The g-g complex also occurs with long vowels and diphthongs in the middle. Think of googly and of German Geige “fiddle.” Unlike violin, both Geige and fiddle are “plebeian” words. In Old Icelandic, we find the verb geiga “take a wrong direction, swerve.” Cognates in the modern Scandinavian languages (mostly dialectal) are geigla, gigla, and the like. Old English –gægan meant the same. Geige, the German name of the violin, probably referred to the movement of the bow (“back and forth”), like English fiddle (compare fiddle-faddle).

Cuckoo: a bird of ill repute but a boon to etymologists. (Image by JJ Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cuckoo: a bird of ill repute but a boon to etymologists. (Image by JJ Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0)As usual, sound imitation and sound symbolism meet. No one doubts that giggle and gaggle are sound-imitative. And once again we come across g-g and g-k complexes with short and long vowels in the middle. The most ancient Germanic word for the cuckoo bird was gauk-, and it is still the same (with some variations) in the modern Scandinavian languages. The reflexes (continuations) of Old English geac– have survived only in some dialects. The difference between g-k and k-k (the latter as in cuckoo) is insignificant, because in attempting to reproduce the bird’s cry, different people hear different “consonants” and “vowels.” As time goes on, words change beyond recognition. Thus, Old English geac was pronounced yeak, and the main consonant was lost (this is probably why geac was supplanted by the much more imitative cuckoo!).

To be sure, when a net is cast so widely, one runs the risk of “rounding up” too many words and calling them related, however remotely. At one time, I investigated the origin of English gawk and had to deal with geeks of all kinds, usually borrowed (I mean the words, not the people) from the Low Countries or northern German. Somewhere one should draw the line, but when one confronts geek, gauk-; gig ~ jig, jog; giggle, gaggle and at least ten more such formations in English and the related languages, one wonders where to stop.

This is a jig, both sound imitative and sound symbolic. (Image source: Kempes Nine Daies Wonder)

This is a jig, both sound imitative and sound symbolic. (Image source: Kempes Nine Daies Wonder)The reason for my “round up” is clear. Against the international background of so many sound-symbolic and sound imitative g-g words, one may perhaps risk suggesting that gig in Sheela na gig is part of this multitude and has a low or, let us say, emotional, meaning. Whether “vulva” is meant is hard to decide, but probably this is indeed the referent. In any case, Sheela appears to be placed on a “low,” ignoble foundation. I also believe that those who explained na as a preposition were right. Jack-in-the box, Jack-o’-lantern, and even such place names as Newcastle on Tyne and Stratford on Avon seem to be formations of the same type.

The images known under the generic name Sheela na gig are medieval, but the name, as noted above, appears to be modern (there are no early records). We cannot know whether the figure has premedieval pagan roots. The interpretation of the name does not depend on this object’s function. Whether the carving was supposed to fend off evil spirits, promote fertility, or remind churchgoers of the abomination of lust, gig must have aroused rather obvious associations in the lookers-on, and those associations had little to do with sanctity.

Featured image by Bert de Mooij

The post “Gig” and its kin appeared first on OUPblog.

February 8, 2021

Grove Music’s 2021 spoof article contest is now open!

I think we can all agree that recent months of pandemic and political unrest have been difficult ones, and often entirely bereft of humor. I am therefore pleased to announce the revival of the Grove Music Online Spoof Article Contest 2021.

Spoof articles have had a long history with Grove Music. Grove’s particular style and format have inspired all kinds of parodies. In previous iterations of the contest, we’ve received articles on instruments (“Musical Cheesegrater” submitted by Caroline Potter won our 2016 contest), composers (our 2014 winner Joanna Wyld submitted an article on American satirical composer Lucas John Henderson, whose works included Oiseau de für Elise for voice and Bunsen burner, which was sadly, but perhaps not surprisingly, destroyed in a fire), performers (our very first contest winner Keith Clifton in 2013 wrote about soprano Stella Del Marinar, who gained late career fame writing gender-swapped opera adaptations such as Le garçon du régiment), and even notation (2016 honorable mention Daniel Melamed wrote about the a little known neume, the sphinculus).

So in the interest of continuing the tradition and in honor of Grove Music Online’s 20th anniversary on 20 January of this year, warm up your keyboards and sharpen your pencils. This year’s winner will receive a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online and $100 in OUP books. May the best parodist win!

Submission Guidelines:Articles must be no longer than 300 words, including any bibliography or works lists you might choose to include. There is no minimum length. Entries that do not adhere to the length limit will be folded, spindled, and rejected.Articles will be judged by a mix of staff and outside judges including Grove Music’s Editor in Chief Deane Root, Editor Anna-Lise Santella, and a guest to be named later.Judges will consider the following criteria:Does the article adhere to Grove style?Is it entertaining?Could it pass for a genuine Grove article (maybe if you forgot your glasses and you were squinting at it)?Submissions must be sent by email sent to editor[at]grovemusic.com as follows:Subject must read “Grove Music fake article contest-[title]” (e.g., Grove Music fake article contest-Ear flute).Body of the email must include the title of the article and your full name and contact information (street address, email, phone)The article must be included in an attached document. It must not include your name. This is to facilitate blind judging. Use your article’s title as the document name (if your article includes punctuation that can’t be in a document title, replace the punctuation with a space). You may send as many as three articles, but please send each submission separately. No more than three entries will be accepted from a single author.All submissions must be received by 23:59 EST on 28 February 2021. Manuscripts received after that time will not be considered.

Feature image: Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

The post Grove Music’s 2021 spoof article contest is now open! appeared first on OUPblog.

February 7, 2021

Dead zones: growing areas of aquatic hypoxia are threatening our oceans and rivers

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians were baffled by patients who had no problems breathing—they could still chat away on their cell phone, even though their blood oxygen levels were so low that they should have been unconscious. The condition was dubbed “silent hypoxia.” The oxygen level in these coronavirus-afflicted people was less than 90%, the medical definition of hypoxia, much lower than the 95-100% seen in a healthy person. Even without outward signs of respiratory problems, silent hypoxia is both a problem in of itself and a signal that the many other manifestations of this deadly disease are on their way.

“Hypoxia” has a similar interpretation in ecology, although the oxygen level defining it is lower. The word is used to describe habitats with less than 2 milligrams of oxygen per liter, or roughly 25% of fully-oxygenated water. The term favored in the popular media for these habitats is “dead zone.” Whether hypoxia or a dead zone, these waters have less oxygen than the “death zone” at Mount Everest where the gas is 40% of the concentration at sea level and mountaineers perish on their way to the summit. But the percentages don’t give a complete picture of how oxygen-poor a dead zone really is. Water can hold much less oxygen, 40 times less than in the same volume of air. So, even small declines in dissolved oxygen can stress out aquatic organisms like Atlantic rock crab or salmon, and most are quickly killed when oxygen drops to dead zone levels.

A lake, sea, or coastal ocean turns into a dead zone when the supply of oxygen from the atmosphere and photosynthesis is overwhelmed by the use of oxygen during organic material degradation. In the past and in some regions today without adequate wastewater treatment, the organic material comes from sewage. In many current dead zones like the Gulf of Mexico and the Baltic Sea, the organics come mainly from excessive growth of algae, fueled by fertilizers leaching from croplands. As the algal organics are degraded, oxygen disappears.

“Dead zones are everywhere around the globe, totaling perhaps as many as a thousand.”

Dead zones in the Gulf and Baltic receive the lion’s share of attention because of their size. But dead zones are everywhere around the globe, totaling perhaps as many as a thousand. Although the number of oxygen-poor aquatic habitats may no longer be increasing, the size of many is expanding, oxygen is dropping to even lower levels, and the number of months they linger is lengthening. Some dead zones like in the Baltic Sea now last throughout the year.

There is nothing silent about the hypoxia in some of these habitats. Dead fish litter beaches and the harvest of bottom-dwelling fish, shrimp, and crabs declines. Hypoxic waters can release phosphorus nutrients and promote harmful algal blooms, which produce chemicals that are toxic to aquatic organisms and animals onshore.

But often hypoxia is silent to the casual observer. In dead zones like the Gulf of Mexico and the Baltic Sea, the hypoxic water hugs the bottom, out of contact with atmospheric oxygen and out of sight except to the specialist. Meanwhile, surface waters can teem with life. Along with a dead zone, the northern Gulf is home to the Fertile Fisheries Crescent, where commercial and sport anglers go after redfish, yellowfin tuna, amberjack, and speckled trout, to name a few of the over 1440 species of finfish in the Gulf. Yet below this cornucopia of marine life, hypoxic waters force fish to flee and devastate the bottom-dwelling invertebrate community, leaving behind only a few opportunistic, small animals tolerant of oxygen deprivation.

Image by Jason Mintzer

Image by Jason MintzerThe hypoxia in the open oceans is even more silent. Open oceans far from land and hard to study are losing oxygen. Known to oceanographers as oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), regions like in the equatorial Pacific Ocean always have had low oxygen. What’s new is the fact that OMZs have been increasing in size and becoming even more oxygen deficient. Over the last few decades, the volume of the Pacific OMZ has expanded by about 7% and oxygen concentrations have dropped by as much as 50% in some regions. Arguably even more troubling, all parts of the ocean are losing oxygen, because of an even bigger problem.

The bigger problem is climate change. A big reason why the oceans are losing oxygen is because they are warming. As temperatures rise, water holds less oxygen and other gases. Along with damaging coral reefs and threatening other marine life, ocean warming exacerbates the problems caused by low oxygen. As the oceans warm, some marine animals require even more oxygen and are even more stressed by low oxygen levels.

Just as silent hypoxia in people cannot be ignored, we need to pay attention to hypoxia in aquatic habitats. Even if the effects are not readily seen, the loss of oxygen signals the declining health of the biosphere and the threat of more trouble to come.

The post Dead zones: growing areas of aquatic hypoxia are threatening our oceans and rivers appeared first on OUPblog.

Naturally speaking

Readers of a certain age may remember the underground comics character Mr. Natural. The brainchild of artist Robert Crumb, Mr. Natural was a likeable con man with a long white beard and flowing yellow gown. Having supposedly renounced the material world, he traded on his mystique of genuineness all the while winking to the readers of his comic strip.

Likewise, the label natural connotes a certain imagery: freshly grown food, pure water, safe consumption. Things described as natural are portrayed as being simple and lacking the intervention of culture, industry, and artificiality.

Let’s take a closer look.

A can of seltzer water in my refrigerator announces “Naturally Flavored Cranberry Lime.” The water is tasty, but does the description mean that it is flavored with fruit juice? On the back of the can, above the box labelled Nutrition Facts, is the statement CONTAINS NO FRUIT JUICE. Below the Nutrition Facts box are the words INGREDIENTS: CARBONATED WATER, NATURAL FLAVORS. So if the natural flavors are not from fruit juice, what are they from?

Similarly, an Apple Raspberry Fruit-to-Go snack food announces that it is a “100% fruit strip” but “with other natural flavors.” Can it be both 100% fruit and have other natural ingredients?

Natural ingredients, it turns out, are the fourth most common thing listed on food labels, right after salt, water, and sugar. But what exactly are they? The Code of Federal Regulations, the codification of US administrative law, tells what can be used in a natural flavoring. It’s a long list and it includes fruit or fruit juice but also herbs, bark, buds, roots, and leaves. Natural ingredients are just ones that come from natural sources, but they may be processed by purifying and extracting some flavor-giving ingredient which is then added back to the food. So natural ingredients come from nature but there is some chemistry involved.

It’s not just flavorings that are given the allure of nature. A restaurant in my town had a hamburger described this way:

Natural Beef, House-made Thousand Island Dressing, Live Bibb Lettuce, American Cheese, Fresh Cut Fries, Portland Ketchup

The adjectives sound appealing: house-made dressing, live lettuce (okay, that one’s a little scary), cheese from America, fries that are fresh cut. And natural beef.

What’s natural beef? That’s up to the US Department of Agriculture, which sets labeling requirements for the use the term natural for meat. But the USDA only requires that meat not contain any artificial ingredients or preservatives and that the food be minimally processed. The exact details of the livestock management practices are not specified, and the naturalness is established by an affidavit signed by the producer. So natural here is part of branding and marketing but lacks the detailed technical definition of, say, organic beef.

The USDA has pretty strict guidelines for how the term organic can be used, distinguishing certified organic foods, both animal and produce, and made with organic foods, which must have 70% certified organic ingredients. A variety of factors go into the labelling of something as organic, including soil quality, animal raising practices, pest and weed control, and irradiation.

None of that applies to the term natural. The Food and Drug Administration, as of this writing, has not come up with a comprehensive definition of natural. In practice, it allows natural to be used if a product doesn’t contain any artificial or synthetic additives or ingredients, but the FDA says little about how something is processed or produced.

If all of this sounds a little artificial to you, I understand. The concepts of nature and natural loom large in our thinking, as a set of vaguely alluring qualities. But sometimes when we try to get back to nature, we are not getting what we think. Take a trip to your local market and see what shouts out natural to you.

The post Naturally speaking appeared first on OUPblog.

February 6, 2021

How the COVID-19 pandemic may permanently change our children’s world

Who amongst us would have imagined that in late 2019 a normally uneventful event would change the world forever? As far as we can tell, all that happened is that a particularly clever virus (SARS-CoV2, which causes COVID-19) spread from an animal to a human. There are three attributes that allowed this virus to change the course of history.

First, animal-to-human viral transmission happens frequently but unlike most emerging viruses, this formidable one had the attribute of readily spreading from person-to-person. In the absence of precautions, each person infects an estimated two to three others. Prior pandemics in our lifetime were all due to influenza. The elderly often had immunity from a similar virus that circulated during their childhood. This brings us to the second attribute; for this virus, we all appear to be susceptible. The same is true of other emerging viruses, including Ebola, but what sets SARS-CoV2 apart is the third attribute. Infected persons have the virus in their nasal and oral secretions for a few days prior to symptom onset and are contagious to close contacts during that time. On top of that, about 20% shed viral contagions yet never develop symptoms, allowing the virus to stealthily spread around the globe.

This pandemic may be neatly sorted out by summer 2021 if we can immunize people worldwide with a vaccine that confers long-lasting immunity. However, the situation may drag on beyond that and the impact for children may last a lifetime. Children who grew up being cautioned about the dangers of this virus will forever be worried about “catching or spreading a cold.” It is tricky to derive a silver lining from this pandemic but a decrease in the number of colds we get in the future may be it. My father-in-law used to write in his Christmas letter that his daughter-in-law, the pediatric infectious diseases physician (as in me) was trying to cure the common cold. Neither I nor anybody else has succeeded in this venture, but I predict that children will get fewer colds post-pandemic. The general public has bought into the implementation of simple measures to decrease spread. Previously, it was mainly acceptable to be out in public with a cough, runny nose, or laryngitis. I used to brag that in four decades I had only missed one day of work because of illness. That is clearly no longer something to be proud of and I need to work on nobler accomplishments. COVID-19 appears to be spread primarily from close contact, especially with a symptomatic person. It seems likely from now on, with or without a mask, it will no longer be acceptable to be outside one’s abode with any evidence of “a cold.” Perhaps we will evolve from the concept that a child is “sick at home” to the concept that they are “studying from home because of mild viral symptoms.” A new challenge for parents will be that from 2020 on, a child only needs to mention “a sore throat” to stay in their warm little bed instead of traipsing to the school bus.

“Children who grew up being cautioned about the dangers of this virus will forever be worried about ‘catching or spreading a cold.'”

Children can be cruel. Cruelty flows downhill. Tormented children eventually replicate that behavior towards others. I remember children writing “No Gets” on their hands to protect themselves from “fleas,” purportedly carried by specific children who were not plunked in the bathtub as often as they should have been. Today’s children are encouraged to think of anyone from outside their bubble of friends and family as being covered in a cloud of germs. This will undoubtedly make it even more difficult for introverted or delightfully eccentric children to find friends. On the other hand, for some children, it is a huge relief to no longer be expected to make eye contact or conduct conversations with people whom they barely know.

It appears likely that adults and children will emerge from this pandemic with less faith in physicians. Early proclamations on how to avoid spread were incorrect as they were based on the false assumption that SARS-CoV2 would be similar to its cousin SARS-CoV1 with primarily symptomatic persons being contagious. International borders remained open and people were told there was no need to wear masks in public. Physicians should not be blamed for reversals in strategy and tactics as the original advice was based upon the most reliable data available at the time. Although physicians do not always provide perfect advice, most people live longer and healthier lives because of their encounters with the medical profession. Childhood immunizations have saved more lives than any other medical intervention has or probably ever will. If my predicted loss of faith in physicians manifests, my most sincere hope is that this does not lead to a decrease in immunization rates. I predict that this will hinge upon the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines that are eventually offered.

Happiness correlates with how one feels about oneself, which, in turn, correlates with how effectively one interacts with others. Many of us, including children, yearn for more in-person interaction. Warmth, humor and non-verbal cues are often missing in telephone calls and two-dimensional virtual meetings. My hope is that post-COVID19, after months to years of the world slowing down, we will be more appreciative of each other and tread more softly on each other’s toes.

Featured image by JenkoAtaman

The post How the COVID-19 pandemic may permanently change our children’s world appeared first on OUPblog.

February 4, 2021

Ten things you didn’t know about Darwin

Charles Darwin’s birthday on the 12th February is widely celebrated in the scientific community and has come to be known as “Darwin day.” In recognition of Darwin’s 212th birthday this year, we have put together a list of ten little-known facts about the father of evolution.

1. Darwin didn’t actually invent the phrase “survival of the fittest.”

It was invented by Herbert Spencer after reading On the Origin of Species in 1864 and adopted by Darwin in his fifth edition of the book.

2. Darwin has over 250 species named after him.

Among these are Ingerana charlesdarwini, a species of frog endemic to India, and Darwinopterus, a flying reptile distantly related to dinosaurs.

3. Darwin published an entire book on the “action of worms.”

He was particularly interested in whether worms could hear, and after they failed to react to “shrill notes from a metal whistle” and “the deepest and loudest tones of a bassoon,” he concluded they could not. Although the thought of the distinguished scientist serenading worms is an amusing one, it was part of Darwin’s project to prove that some degree of intelligence existed even in the lowliest creatures.

Darwinopterus was a genus of the pterosaur, one of which is reconstructed here. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)

Darwinopterus was a genus of the pterosaur, one of which is reconstructed here. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)4. Darwin was only 22 years old when he was chosen to be HMS Beagle’s naturalist, having just finished his theology degree at Cambridge University.

He was recommended for the position by his friend and mentor Professor John Henslow, who wrote that he considered Darwin “to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation—I state this not on the supposition of yr. being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, & noting any thing worthy to be noted in Natural History.” John Henslow was proven right by history.

5. Anything you know about the Galápagos islands likely doesn’t come from Darwin.

Instead, your knowledge is likely to stem from the 1905-6 expedition that followed Darwin’s journey there, rather than Darwin’s work itself. While Darwin spent only five weeks on the islands, the subsequent expedition was there for a year and a day, making theirs the longest scientific expedition to the Galápagos in its history.

6. Darwin was almost beaten to the theory of natural selection by Alfred Russel Wallace.

Having waited for 20 years to publish his theory, Darwin was on the verge of finishing his book on natural selection when he read an essay by a fellow naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace. The essay outlined Wallace’s own theory of natural selection, which he had developed independently.

Darwin was crushed, writing to a friend that “all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed.” Darwin offered to make a joint presentation of their findings, but when Darwin and Wallace made the presentation in 1858, there was little reaction from the science community. Darwin went on to publish his solo work On the Origin of Species in 1859, which caused a much bigger splash, and cemented his reputation as the father of natural selection.

7. Darwin married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, and together they had ten children.

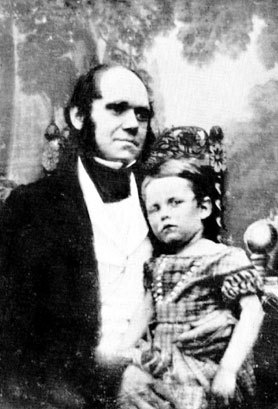

Charles with his first born, William Erasmus Darwin. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)

Charles with his first born, William Erasmus Darwin. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)Ever the scientist, Darwin’s response to the birth of his first child was to record the baby’s sneezing, hiccupping, yawning, stretching, suckling, screaming, and reaction to tickling. He published his observations in the journal Mind in 1877.

8. Darwin appeared on the British £10 note from 2000 to 2018, when he was replaced by Jane Austen.

In February 2018, the Bank of England announced that with just a week until the Darwin notes would stop being legal tender, there were still 211 million in circulation. “Put end to end, that’s enough notes to retrace almost half of Darwin’s journey on HMS Beagle. Or, these would weigh the same as nearly two thousand giant Galápagos tortoises that Darwin saw on his travels.”

9. Darwin was the half-cousin of Francis Galton, a famous polymath.

Among Galton’s achievements were coining the phrase “nature versus nurture” and inventing the statistical concept of correlation, known to all schoolchildren today. Less admirably, he used his discoveries to pioneer eugenics, and in fact invented the word itself.

10. 2021 is the 150th anniversary of the publication of Darwin’s The Descent of Man, which was first released in 1871.

One of Darwin’s primary aims in writing the book was to consider “whether man, like every other species, is descended from some pre-existing form.” The backlash when he concluded that we are has made history.

Featured image by Piotr Grycuk

The post Ten things you didn’t know about Darwin appeared first on OUPblog.

How to survive a tsunami

If you, your family, or friends ever go near the shore of the ocean or a lake, you need to learn about tsunamis. Unfortunately, the current public perception of the tsunami hazards is all too often a three-step denial: (1) It won’t happen to me. (2) If it does, it won’t be that bad. (3) If it is bad, there’s nothing I could’ve done anyway. This perception must be changed in order to save lives and build a culture of tsunami hazard preparedness.

So, the logical question is “When will the next big tsunami strike?” Probably after the next really big earthquake under or near the sea. As the father of modern seismology, Charles Richter is reported to have said, “Only fools and charlatans predict earthquakes.” But the odds of a large earthquake do increase every year without one. As weird as it may seem, small earthquakes are a good thing. They literally relieve the stress along seismically active areas. Long periods of time without quakes in these areas means that the pressure is continuing to build and may well be relieved by a really big quake. Those areas that are normally seismically active but have had no stress-relieving earthquakes are known as “seismic gaps.” And there are numerous seismic gaps around the world. For example, the Cascadia Subduction Zone, lying just 50 miles offshore of Oregon, Washington state, and southern British Columbia. It is similar to the fault zone off the coast of Sumatra that caused the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Then there’s the area around the popular tourist destination of Acapulco, Mexico, which sits in a seismic gap that hasn’t had a significant earthquake in over a century, and has been described as “a tectonic time bomb waiting to go off.” And then there’s Alaska with 3 gaps which have had no large earthquakes in the past century. Chile has one too, off its northern coast—and the list continues.

So, the clock is ticking.

But tsunamis are generated not only by earthquakes, but also by landslides, volcanic eruptions, and other, much weirder, causes. Most of the fatalities caused by the 1964 Good Friday earthquake in Alaska—82 out of 131 total deaths—were caused by local tsunamis generated by underwater landslides set off by the earthquake. Landslides, from the land into the sea or underwater can also be set off by other causes including heavy rain, rising sea level, and even gas bubbles trapped under the sediment lying on the seafloor that suddenly decide to pop!

So, what can we do? Not only do the chances of another tsunami increase every year, but with every year that passes, more people forget the danger. For example, Hawaii is experiencing the longest period in recorded history without being struck by a Pacific-wide tsunami, with over 60 years since the devastating 1960 tsunami from Chile. And with every year that passes, coastal populations continue to grow, and there are fewer and fewer people alive now that experienced a tsunami, take the threat seriously, and know how to respond. People often assume that in the event of an emergency they will be evacuated by first responders, i.e. police and fire department personnel. The problem with that assumption is that there simply aren’t enough first responders to carry this out, and based on our experience, in many cases they have not had adequate training due to lack of funding or time dedicated to working on natural hazard protocols. What about education of the general public or children in schools? Similar problem. This author once had a state Governor tell him, “We can’t educate the public about tsunamis. It would scare away the tourists.” Add to this the threat from local tsunamis, where for many areas there is simply no time for tsunami alerts and therefore there could be no action by emergency management and first responders. The need for tsunami preparedness education is critical. Every hotel is required to have fire evacuation information posted on the back of the door of every hotel room. But for hotels near the coast there is little or no tsunami information for hotel guests, even in beach-front hotels. And it goes well beyond hotels.

People run from the approaching tsunami in Hilo, Hawai’i on 1 April 1946. note the wave just left of the man’s head in right centre of image.

People run from the approaching tsunami in Hilo, Hawai’i on 1 April 1946. note the wave just left of the man’s head in right centre of image.Many coastlines do not have tsunami warning signs, fewer have marked evacuation routes, and even if they did, what do they mean? Without education the signs have little value, and tsunami education is patchy at best. In our time-challenged lives, education messages need to hit home and often. Start at Grade 1 and build from there every year, involve parents, grandparents, and friends, and soon tsunami education and awareness become a normal part of the fabric of life, like using an umbrella when it rains. Every coastline is different, every tsunami is different, which is why everyone needs their own plan to keep it simple and to stick to it. Where is the nearest high ground or four-storey concrete reinforced building? How long does it take to walk there? Where is the family meeting point? Does every family member know their plan? The KISS principle is best: Keep It Simple Stupid. For example, a car might seem a logical option and will definitely be one of the only options for the unprepared, but if everyone panics there will be traffic jams, crashes, gridlock, and precious minutes lost—and if the tsunami catches you in a car…

While there may not be tsunami warning signs and evacuations routes marked, there are tsunami warning systems in many parts of the world and as such there is often time for evacuation in areas that are distant from the source of the tsunami. But for locally-generated tsunamis, especially those created by landslides, there may not be time for an official warning. You need to know what actions to take without hesitation—hence you need to have a plan. Learn where the tsunami hazard zones are around where you live, work, and play. Figure out the fastest and safest evacuation route. If you have children in school, check to see if the school is in a tsunami hazard zone, and if so, make sure they have an evacuation plan and practice it. Education goes both ways: parents can educate the school too. In the event of a Tsunami Warning, do not go to the school to grab your children. By the time you get there, they will already have been evacuated and rushing to the school will only add chaos to the situation and put you at risk.

This is all well and good, these are the perfect education and evacuation scenarios, but what about where there are no signs, no marked hazard zones, no warning system? Worse still perhaps, everybody is a tourist at some point in their life. What if the coast is unfamiliar, perhaps the language too, and so on? What do you do? Finding high ground or a safer place (e.g. a tall building) is easy: you look. Be aware of the warning signs: did you feel an earthquake, is the sea rapidly receding from the coast, or did a wave suddenly come in much further than usual? All these are potential precursors of what is to come. Move away from the coast and inland, these minutes and seconds could save your life. If it is a false alarm though, do not feel stupid, feel empowered: you knew what to do and you followed through.

What does the future hold? Have we learned from our mistakes? Will we forget the danger posed by tsunamis as time passes or will we educate and prepare for the next inevitable tsunami to save lives? It’s not if another tsunami will strike, but when!

Featured and secondary images from Wikimedia Commons.

The post How to survive a tsunami appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers