Oxford University Press's Blog, page 116

March 5, 2021

The horizontal agency problem and how China deals with it

On 18 December 2020, the United States passed the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act. The law stipulates that any US-listed foreign company will be removed from American stock exchanges if it does not comply with US auditing oversight rules within three years. It is well known that this law is specifically aimed at US-listed Chinese firms.

For investors, the issue of corporate transparency is paramount. When college students take their first finance course, they are taught that there are two major costs that can hinder the firm’s valuation. The first is information asymmetry. Outsiders, such as investors and lenders, do not know the firm as well as the firm’s insiders. Therefore, for example, the firm’s cost of capital might be higher than it should be. The second major cost is the agency problem. While shareholders own the firm and managers control the firm, managers may not act in the best interest of shareholders, and this problem can be greatly exacerbated when there is a high degree of information asymmetry. In the early 2000s, we witnessed how significant this agency problem can be. Because of the actions of self-serving executives at firms such as Enron and WorldCom, it contributed to an investor confidence crisis around the world, which eventually led to major corporate governance reforms world-wide.

Shareholders and managers are not the only stakeholders that benefit when stock markets function well. The country’s overall economy also benefits. Economies cannot grow unless they have well-functioning stock markets. Up until now, China was a striking exception to this rule. However, for China’s growth to continue, it recognizes that a well-functioning stock market must play a major role. Therefore, two important questions are the following. First, what is the nature of the agency problem in China? Second, what is the potential solution to this problem?

In China, the main agency problem is the conflict of interest between large shareholders and minority shareholders. Because this agency problem is among shareholders, we can call this a “horizontal” agency problem, which is unlike the “vertical” agency problem that can exist between shareholders and managers in Western countries and in other developed nations. The main reason why the agency problems are different between Western firms and Chinese firms is because unlike in the West, pretty much every Chinese listed-firm has a very large shareholder. On average a Chinese listed-firm’s largest shareholder owns at least 30% of the firm. In the West, ownership is largely diffuse, and so managers control the firms. However, in China, the large shareholders control their firms.

In China, the horizontal agency problem is quite significant. Throughout the 1990s and early part of the 2000s, controlling shareholders of listed-firms would simply take money from the firm. They claimed that these were “intercorporate loans,” but these loans were interest-free and almost never paid back. On the balance sheets, they were booked as “other receivables.” This outright theft from minority shareholders was not a trivial amount. On average, other receivables accounted for almost 10% of the firm’s total assets. Chinese securities regulators came down hard on this practice, and now it is essentially eradicated. However, as long as there are large shareholders, the horizontal agency problem will continue to exist. For example, controlling shareholders can engage in related party transactions with the firm on favorable terms. An example would be the firm buying an asset from the shareholder at a high price. Note that this form of expropriation from minority shareholders is almost impossible to detect. Therefore, this gives rise to the crucial question of how China is dealing with this agency problem.

In the West, there are many potential solutions to the vertical agency problem. For example, securities analysts, institutional investors, large lenders such as banks, independent auditors, and boards of directors, can serve as corporate monitors. However, in China, these potential monitors are limited in their ability to protect minority shareholders. For example, most board directors are not independent, and they are often appointed by large shareholders. In addition, given that large shareholders are more entrenched than firm managers, the horizontal agency may be harder to address than the vertical agency problem. Therefore, the main solution to the horizontal agency problem in China rests on having strong laws and regulations, and to enforce them.

There are many corporate and securities laws in China, including the 1985 Accounting Law, to ensure the quality of accounting information, the 1986 Enterprise Bankruptcy Law, to improve the quality of enterprises by eliminating inefficient ones, the 1993 Company Law and the 1998 Securities Law, to protect minority investors, and there is also the 1999 Contract Law and the 2007 Property Rights Law. These laws have been updated and improved upon several times. Are these laws and regulations, and the regulatory authorities, effective at mitigating the horizontal agency problem in China? According to anecdotal evidence and academic research, the answer seems to be mostly yes, and especially recently. For example, it is now difficult for controlling shareholders to engage in favorable related party transactions, and this is because of a regulation that allows minority shareholders to vote on these transactions. Throughout the 1990s and early part of the 2000s, it was common for scholars to criticize China’s laws and institutions. Today, it is more appropriate to say that China’s laws and institutions have dramatically improved.

In addition to recognizing the horizontal agency problem and identifying the potential solution, there is a third important question when it comes to Chinese firms and their stocks. What about state-owned enterprises (SOEs)? For many Chinese listed-firms, the largest shareholder is the government. SOEs make up the majority of the market capitalization of the Chinese stock markets. State ownership of enterprises is often criticized by Western scholars because of their underperformance and because the government might extract resources from the firm (that is, the government may be a “grabbing hand”). However, in China, while SOEs do underperform, they do not fail. For example, the government sometimes provides SOEs with favorable bank loans and other subsidies. Therefore, the government is more like a “helping hand.” In our view, the helping hand is justified because SOEs are tasked with the responsibility of maintaining national and social interests, such as making capital investments and maintaining industrial production, and also maintaining social stability, such as maintaining excess employment. Therefore, we feel that Western criticisms of state-owned firms, especially when it comes to China, may be misplaced.

Finally, Chinese companies not only have a responsibility to investors, they have a responsibility to all stakeholders, including society at large. Therefore, another important question is whether corporate social responsibility (CSR) matters in China. Chinese citizens and consumers care about social issues, but right now, they are relying on the government to carry out CSR initiatives and programs. The government seems to be somewhat effective in promoting CSR. However, while there is still a long way to go for Chinese firms to be truly interested in CSR, we think the future is bright.

In sum, Chinese firms are vulnerable to a significant agency problem, but China is well aware of it and is tackling the problem. This is important, not only for China, but also for the world, given that China will soon become the world’s largest economy.

The post The horizontal agency problem and how China deals with it appeared first on OUPblog.

March 4, 2021

Why future “consciousness detectors” should look for brain complexity

Imagine you are the victim of an unfortunate accident. A car crash, perhaps, or a fall down the stairs. After some time, you regain awareness. Sounds return, smells greet your nostrils, textures kiss your skin. Unable to move or speak, you lie helpless in your hospital bed. How would anyone know that you—your thoughts, feelings, and experiences—are still there?

Doctors might look at your brainwave activity, as measured by an EEG device, to see if anyone’s home. What frequencies of activity does your brain produce? One brain rhythm your doctor might look for is called “delta.” This slow activity, one to four cycles per second, generally tells us that the cerebral cortex is offline and that the mind is plunged into unconsciousness. It is seen in dreamless sleep and under anesthesia.

Delta activity might suggest to your doctor that no one is home, that you have no more awareness or feeling than someone in a dreamless sleep. But this assumption may be wrong. My recent research with Angelman syndrome, a rare disorder caused by dysfunction of the gene UBE3A, shows that children with this disorder who are unambiguously awake and conscious still show massive delta activity in their EEGs. These children have delayed development, intellectual disability, and often seizures. Some of them cannot communicate without gestures or special devices. But they can clearly feed themselves, play with other children, respond to environmental cues, and follow simple commands from their parents. In other words, there’s no question that they are conscious. So why are their brains generating delta activity, a signature of unconsciousness, while they are wide awake?

The short answer is, nobody knows. But studying these children may be key to developing better biomarkers of consciousness that can be used to determine whether unresponsive brain-injured patients are covertly conscious—that is, conscious without the accompanying behaviors that usually tell us that someone is conscious.

Besides delta activity, another EEG feature that relates to consciousness is the complexity of the EEG signal. This can be measured in various ways, such as looking for reoccurring patterns in the EEG signal or measuring how difficult the signal is to compress (on your computer, think about zipping an image of a Vermeer painting—complex—versus zipping an image of a Rothko painting—simple). We already know EEG complexity is diminished during dreamless sleep and anesthesia. Interestingly, it is also increased by psychedelic drugs that induce hallucinations. But in Angelman syndrome, where the rules of delta seem not to apply, will EEG complexity still track consciousness?

My colleagues and I at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and collaborating institutions set out to test this hypothesis using EEGs recorded from 35 children with Angelman syndrome during both wakefulness and sleep. First, we asked whether the power of delta activity would change when the children fell asleep and, second, whether the EEG complexity would change when the children fell asleep.

As we already expected, delta activity appeared very strong both when children with Angelman syndrome were awake and asleep. However, a thin slice of the delta spectrum was modulated by sleep. Specifically, the delta waves between one and two cycles per second were enhanced when the children napped. Delta waves between two and four cycles per second, on the other hand, did not show much modulation, as this portion of the delta spectrum appears to mostly reflect abnormalities in Angelman syndrome.

But what about the EEG complexity? As it turns out, this biomarker of consciousness passed the Angelman syndrome test with flying colors. Both measures of EEG complexity based on reoccurring patterns and compression were greatly diminished when the children napped. While EEG activity is rich and varied when children with Angelman syndrome are awake, it becomes repetitive and predictable when they are asleep.

The results of this experiment are highly encouraging: we can use EEG signal complexity to track consciousness, even under circumstances where brain activity is highly abnormal. Of course, children with Angelman syndrome look very different from the patient who you imagined yourself as at the beginning of this post. But the bottom line is that we may never find universal biomarkers of consciousness by only studying healthy brains. Looking at many different brains—those that are healthy and those that are affected by various diseases—and searching for universal patterns is a better strategy, one that is more likely to translate to severely brain-injured patients in the intensive care units of hospitals.

Given the overwhelming evidence relating EEG signal complexity to consciousness, I believe this metric will likely be used in clinics in the near future to measure patients’ level of consciousness. However, some debate still exists regarding the best context for taking these measurements. Is it better to look at the EEG complexity in response to magnetic brain stimulation, thus revealing the brain’s capacity to respond to a gentle “push”? Or it is better to look at the spontaneous EEG complexity, when the brain is minding its own business, so to speak? In our study, we took the latter approach, which is certainly easier in young children with neurodevelopmental disorders. However, the former approach, which uses a coil of wire held above the head to stimulate the brain noninvasively, has accumulated very strong evidence in the past decade as a nearly perfect measure of conscious state.

The above technique, called the perturbational complexity index or PCI, has never been studied in Angelman syndrome. We do not know yet whether the abnormal brain dynamics seen in children with Angelman syndrome would trick PCI into giving a false negative result (that the children are unconscious when they are in fact awake and conscious), or if PCI would ace the test. But there is only one way to find out. The next step in this research will be to test PCI in children with Angelman syndrome. If it succeeds, then we are one step closer to building a “consciousness detector” for clinical use. If not, then back to the drawing board.

The post Why future “consciousness detectors” should look for brain complexity appeared first on OUPblog.

March 3, 2021

Folklore and etymology: imps and elves (or COVID-19 and backpain)

With everybody talking about vaccines and shots, I thought it might be proper for me to contribute the etymologist’s mite to the discussion. I won’t say anything new or controversial, but the facts described below may not be universally known.

The German for “to give a shot, to vaccinate” is impf-en (-en is the ending of the infinitive). Impf– is an exact cognate of English imp. How can it be? Many centuries ago, impfen (in a slightly different phonetic form) appeared in Old High German as a borrowing of Medieval Latin impotāre “to graft.” Latin impotus, itself a borrowing from Greek, meant “graft”; Greek émphutos designated “grafted, implanted.” In German, the verb became a term of winemaking and horticulture and acquired the sense “to improve the quality of wine by bunging the vessel.” Centuries later, the term began to be used for “vaccination”: thus, from “corking a bottle” to “administering a shot.”

Devilish overtones galore. (Image by Simon Blocquel.)

Devilish overtones galore. (Image by Simon Blocquel.)It is the sense “graft” that determined the development of the same Latin verb in English. The Old English noun impe ~ impa meant “sapling, young shoot” (shoot: compare shot in the arm!). Later, sapling broadened its meaning and began to designate “child.” The train of thought is predictable: compare sap “juice,” the root of sapling “young tree” and still later “young person,” as in Shakespeare; scion also first meant “shoot, slip, graft.” With time, the word imp “sapling” acquired the sense “the child of the Devil” and still later “mischievous child.” Yet the devilish overtones in this ancient word have never been lost. Obstinate children and troublesome youngsters often get bizarre names. Thus, “urchin” goes back to “hedgehog” (French hérisson). Poor stickly-prickly hobbledehoys!

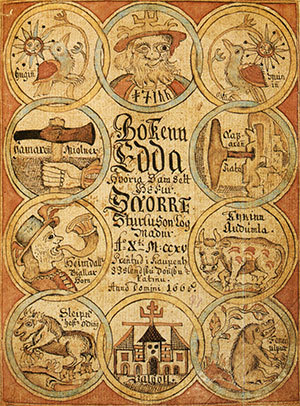

The origins of elvesI wonder how many people have heard the word elfshot. It means “lumbago, backpain.” Imps are the Devil’s children, but why elves? Forget Shakespeare’s elves, the creatures that merged in oral tradition with the fairies of the ancient Celts (hence fairy tales, which, at least today, have nothing to do with fairies). We are interested in Germanic elves. The old Scandinavians knew a good deal about them, but we know relatively little, even though dozens of good articles and books have been written about their nature and origin. Our most important source is Edda, a brilliant summary of ancient tales written in the thirteenth century by the Icelandic politician, poet, and antiquarian Snorri Sturluson. By his time, the ancient elf-lore must have fallen into desuetude, for in his work we find only a short passage about the elves’ “home,” called Álfheim (the Icelandic for “elf” was alfr, later álfr; á designates long a; please keep in mind this information). Snorri wrote this about their habitat: “…there live the people called light elves, but the dark elves live down in the earth and they are unlike the others in appearance and much more so in character. The light elves are fairer than the sun to look upon, but the dark elves, blacker than pitch.”

An early Danish edition of Snorri’s book. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)

An early Danish edition of Snorri’s book. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)Snorri was a great master of talking freely and saying little. Clearly, he had nothing to say in addition to the fact that, according to his information, light and dark elves existed. This is surprising, because belief in elves is very much alive even in today’s Iceland, and from the sagas we learn that the elves were venerated, that sacrificial food was left for them, that they protected the land and its inhabitants, and that some kings were associated with their cult. (The name Olaf has nothing to do with elf.) Much to our confusion, old and modern folklore has preserved the names of numerous supernatural beings resembling one another and endowed with similar functions. All of them belong to what specialists call lower mythology. Dwarfs were especially conspicuous, while elves appear in the extant tales of the Germanic-speaking peoples sporadically, and we are unable to produce a coherent picture of their role. Not improbably, their original habitat was under the ground and they seem to have been associated with the cult of the dead. Yet it comes as a surprise that in the constantly recurring formula of Old Scandinavian poetry, elves are paired with one family of the gods.

Naturally, scholars tried to derive the function of the elves from the root of Old Icelandic alfr, Old High German alba (Modern German Alp ~ Alpe), Old English elf ~ ylf, etc. I have often mentioned the greatest difficulty of etymological reconstruction: one cannot discover the origin of the word without knowing the function of the “thing.” Even when the application of the material object (such as an ax, a sword, a knife) or the nature of a movement (“go,” “sit,” “cut”) is absolutely clear, the names are not in a hurry to reveal the secret of their creation. Since the role of the elves is far from obvious (to us), the chance of guessing the etymology of elf is not high.

Two hypotheses compete in this area. One tentatively connects elf with the Sanskrit name of a semi-divine artificer. This is an old hypothesis and the only one tentatively mentioned in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966). The connection is impeccable from the phonetic point of view, but, as far as we can judge, Germanic elves were not artificers. Though that dictionary defines elf as “dwarf,” elves and dwarfs seem to have differed, at least in Scandinavian myths, for only dwarfs were great artisans (they produced all the treasures the gods possessed). The other etymology looks for the solution in Latin albus “white” and in place names like Albion. The connection is tempting only because Snorri knew something about white elves. It also remains unclear whether elves were ever believed to dwell in the Alps. Old English word lists did mention mountain elves but along with forest and sea elves. Elf must have become a generic term for “dangerous supernatural being.” The famous Erlking (Goethe-Schubert’s Erlkönig) means “the king of the elves”; he inhabited a forest.

Elves are very much alive in today’s Iceland. (Image via Piqsels.)

Elves are very much alive in today’s Iceland. (Image via Piqsels.)Wherever the truth may be, elves were feared (hence the necessity to sacrifice to them!). The German word Alptraum (-traum “dream”) means “nightmare” (-mare “incubus”). Consequently, elves attacked humans in sleep. But then all (all!) the invisible spirits of the remotest past inspired dread. The gods made people giddy, dwarfs (if the etymological connection is right) made them dizzy, and elves, well, elves could do a lot of harm. They could sit on a human being’s breast at night (as we have just seen), and they could also shoot! Hence elfshot, Old English ylfa gesceot. This runs counter to the rather benevolent picture of the Scandinavian elves that emerges from Snorri and the Icelandic sagas.

A last piece of nastiness comes from phonetics. English must have borrowed Scandinavian álf(r) “elf” early, because such borrowings usually occurred in the Middle period. Yet the first recorded forms of oaf, the descendant of álfr, go back to the 1620s. The word’s phonetic development remains unclear, and no book on the history of English explains when l was lost in it and why its au alternated with oa ~ ou. The loss of l before f did not happen in oaf regularly, “by law,” as it did in calf and half. In any case, after the loss of l, oaf no longer resembled elf, the more so because in seventeenth-century English, oaf meant “a changeling left by the elves” and only by implication, “dolt, halfwit,” rather than “elf.”

Here ends our journey from imp to oaf. Stay away from both and get vaccinated.

Featured image by US Government Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The post Folklore and etymology: imps and elves (or COVID-19 and backpain) appeared first on OUPblog.

March 2, 2021

Digging into the vaults of the unknown: the “Transcending Dystopia” research diaries

Research for Transcending Dystopia over the course of almost a decade was truly a journey, piecing together disparate snippets that have been transmitted in different repositories to gain insight into the musical practices and lives of Jews in postwar Germany. Among the 26 archives and private collections I consulted, two experiences stand out—the first being somewhat unusual, the second being quite extraordinary.

The Stasi ArchiveDuring its 40-year existence, the East German Ministry for State Security, also known as Stasi, undertook one of the most intrusive and oppressive mass surveillance operations ever conducted. It collected millions of files on people it suspected of being enemies of the state. Today, the archive contains miles of shelved documents, nearly two million images, and over 30,000 video and audio recordings housed in 13 branches throughout Germany.

Although the archive has no particular music focus, musicians were naturally a subject of the operations as well—both as informal collaborators (known in local parlance as IMs) and as surveilled subjects. As such I was hoping to find documentation on East Germany’s perspectives on Jewish culture and its main protagonists as well as the political instrumentalization of the Jewish communities and Jewish music. I was particularly interested in information related to Werner Sander (1902–1972), a native of Breslau and cantor of the Jewish community in Leipzig from 1950 until his death, as well as the singers of the Leipziger Synagogalchor, a mixed choir of 25 to 30 non-Jewish lay singers dedicated to the cultivation and preservation of synagogue music as well as Yiddish and Hebrew folklore since 1962.

The process of locating materials turned out to be quite unique. It began with a formal application that is certainly more involved than elsewhere, but on the whole quite straightforward. My request to view materials was granted after a few months, in March 2014. Unlike any other archive, I was assigned a case worker who would locate files for me from all branches and, if possible, make them available in Berlin. The first step was to provide names, addresses, and dates and places of birth of all persons of interest to my research focus (17 names in all). By mid-July 2014, a first batch of documents was waiting for me in Berlin—but what a bummer. The detailed information in the files pertaining to individuals was tedious, bureaucratic, and—pertaining to my research—largely meaningless. Do we really need to know at which times Berta B. walked her dog? In the case files of persons still alive or deceased less than thirty years ago, passages (potentially of interest) were blacked out. Indeed, this was anything but The Lives of Others, the 2006 nail-biting Oscar-winning Stasi drama. Only a few singers were routinely monitored. The vast majority held fast to their public commitment to socialism and aroused no suspicion, following the same conformist middle path as many other GDR citizens.

Although the research results were meager (surprisingly, there were no documents on the West Berlin cantors, who in GDR times shuttled unhindered between East and West Berlin in order to officiate and perform at concerts), the retrieved files nevertheless provided some useful details. In 1967, charges were brought in the Federal Republic of Germany against the former Breslau Gestapo chief and his assistant. The Bielefeld Regional Court called Werner Sander and his wife Ida to the witness stand. In this context, the Stasi made an inquiry as to whether Sander had really been politically persecuted and interned in a concentration camp and whether it was advisable for him to take the stand. The Stasi had reservations about personal security and discrimination and feared that the GDR would be exposed to criticism. In light of Sander’s surveillance report, however, there appeared to be no concern about him fleeing the country (as many other citizens did). In fact, the Stasi never doubted the loyalty of the Sander family, having issued Ida Sander a special permit to travel to West Germany for family festivities in 1959. In the end, however, Sander did not appear as a witness (the reasons are unknown).

Interesting details also stemmed from general files, such as an undated typescript from the 1980s, when the regime began to perceive the dwindling number of Jews as a demographic and cultural problem. The typescript includes a section on Jewish music that discusses synagogue concerts in Berlin, the well-known chanteuse of Yiddish song Lin Jaldati and her family, and the Leipziger Synagogalchor. The choir is praised as an exceptional example of the preservation of Jewish culture, though it goes unmentioned that all the singers at the time were non-Jews. As such, the choir was considered politically transparent enough to represent and strengthen the idea of anti-fascism and the ideas of heritage and tradition in the service of the state. In order to draw conclusions for my book, all this material alone was not sufficient. I had to supplement my findings with interviews of the singers (and others)—an inherently complex and sensitive undertaking due to some interviewees’ status as informal collaborators and/or objects of the Stasi. Still, the Stasi archive proved to be an episode in the life of a musicologist unlike any other. Research was not about scores or musical practices, but about politics and (slanderous) details based on secret police files.

Finding Adi PattiEarly on in my research, I stumbled across—let’s call him “a person of interest”—Adi Patti. Born in 1899 as Adolf Schwersenz, he originally aspired to be an actor, but having been graced with an impeccable tenor voice, he studied music at the Royal Academy of Music in Berlin right after returning from the battles of World War I. Between 1920 and 1925 he also studied voice privately in Berlin and in Milan. After a brief engagement at the Berliner Kammeroper in 1925, he worked as a radio and opera singer, promoting himself as German-Italian heroic tenor under the artist name Adi Patti.

Nazism put an end to his flourishing career; and wisely, already way before being expelled by the Reich Music Chamber on 3 December 1936, Adi trained under well-known cantors to become a cantor himself with the Jewish community of Berlin. According to contemporary newspaper reports, Adi also occasionally performed opera and operetta with the Jewish Culture League, a segregated performing arts organization established by and for Jews in collaboration with the Nazis. Having survived the Second World War, after 1945 he became one of the main players in the reconstitution of Jewish cultural life in Berlin, initially establishing an autonomous community with an active music program.

He was also instrumental in the first Jewish broadcasts in postwar Germany, known as Sabbatfeiern, during which he sang liturgical and paraliturgical pieces, often accompanied by a choir. But by the late 1940s his name had disappeared from concert programs and announcements, and I wondered what happened to this determined and industrious man, who can be credited with the revival of Jewish cultural events in postwar Berlin. But nothing and nobody could explain this disappearance—the deeper I dug, the deeper the void. Adi Patti seemed to have vanished from any written record. Then one day—I had shifted my focus to another person of interest, the banker and bureaucrat of the Berlin magistrate Siegmund Weltlinger who happened to write a few pieces for voice and piano after the war—my luck changed.

Sifting through correspondence in the Siegmund Weltlinger Papers at the Landesarchiv Berlin, I discovered a photograph inserted into a letter that showed a familiar face: Adi Patti in a chair at a beach, along with wife and daughter! The letter, however, revealed the name of a different sender, that of Ralph Svarson, as it turned out, the name he had assumed shortly after emigrating to the United States in the spring of 1947. Adi eventually moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where he worked as a cantor and also gave voice lessons until his untimely death (he was diabetic) on 19 January 1959, in Methuen. Only one step further, the questions on his trajectory remained. With a bit of finesse, I was able to locate his daughter Susan Svarson Kelleher, who lived in Massachusetts, but there was no response to my inquiries. Susan had died in 2009; I was too late. An inquiry with her daughter Kathy Luzader in 2010 was ill-timed—the loss was still too fresh to talk about family history. But then in 2013, Susan’s son James got in touch and invited me to the family home in Melrose, MA. There, I found a treasure trove: the sheer volume of prayer books, books in Hebrew, and liturgical music (both printed and copied by hand) in his estate was just mind-blowing. There were lots of old articles, photos, albums, posters, and even a Torah scroll from Berlin. Some of it was in the attic and had not been accessed for years, if not decades. What I unearthed allowed me to paint a full picture of a fascinating personality, who survived the trials and tribulations of life and (post)war times with imagination and verve. But what’s even more meaningful, I was able to connect the Kelleher family to the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, and to facilitate just a year later, the permanent transfer of a large part of the estate. It has been processed and catalogued as AR 25615 at the Center for Jewish History and can be accessed in the online archive.

The post Digging into the vaults of the unknown: the “Transcending Dystopia” research diaries appeared first on OUPblog.

March 1, 2021

Nine books to make you think about gender politics in the political sphere

Every year in March we celebrate Women’s History Month, a perfect time to be inspired by the triumphs of real-life heroes. Let us not forget the path it took to get this far and the tribulations that these women endured. Society has come so far since the induction of the 19th Amendment, but we still have a way to go. We have compiled a list of titles that explore the ups and downs of this journey as well as present bold ideas to improve the future.

1. Credible Threat by Sarah Sobieraj

Greta Thunberg. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Anita Sarkeesian. Emma Gonzalez. When women are vocal about political and social issues, too-often they are flogged with attacks via social networking sites, comment sections, discussion boards, email, and direct message. This book shows that this online abuse is more than interpersonal bullying—it is a visceral response to the threat of equality in digital conversations and arenas that men would prefer to control.

Read a free chapter here.

2. 100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment edited by Holly J. McCammon and Lee Ann Banaszak

2. 100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment edited by Holly J. McCammon and Lee Ann Banaszak

This collection of original essays takes a long view of the past century of women’s political engagement to gauge how much women have achieved in the political arena. The volume looks back at the decades since women won the right to vote to analyze the changes, developments, and even continuities in women’s roles in the broad political sphere.

Read a free chapter here.

3. Race, Gender, and Political Representation by Beth Reingold, Kerry L. Haynie, and Kirsten Widner

It is well established that the race and gender of elected representatives influence the ways in which they legislate, but surprisingly little research exists on how race and gender interact to affect who is elected and how they behave once in office. This book takes up the call to think about representation in the United States as intersectional and measures the extent to which political representation is simultaneously gendered and raced.

Read a free chapter here.

4. Violence Against Women in Politics by Mona Lena Krook

Tracing its global emergence as a concept, this book draws on insights from multiple disciplines—political science, sociology, history, gender studies, economics, linguistics, psychology, and forensic science—to develop a more robust version of this concept to support ongoing activism and inform future scholarly work.

Read a free chapter here.

5. Feminist Democratic Representation by Karen Celis and Sarah Childs

5. Feminist Democratic Representation by Karen Celis and Sarah Childs

Popular consensus has long been that if “enough women” are present in political institutions they will represent “women’s interests.” Yet many believe that differences among women fatally undermine both the principle and the practice of women’s group representation. This book considers a broad spectrum of contemporary problems to discuss women’s under- and misrepresentation and the “good, bad and the ugly” representative.

Read a free chapter here.

6. Recoding the Boys’ Club by Daniel Kreiss, Kirsten Adams, Jenni Ciesielski, Haley Fernandez, Kate Frauenfelder, Brinley Lowe, and Gabrielle Micchia

Drawing on a unique dataset of 1,004 staffers working in political technology on presidential campaigns from 2004-2016, analysis of hiring patterns during the 2020 presidential primary cycle, and interviews with 45 women who worked on 12 different presidential campaigns, this book reveals the underrepresentation of women in political technology, especially leadership positions, as well as the struggle women face to have their voices heard within the “boys’ clubs” and “bro cultures” of political technology.

Read a free chapter here.

7. The Rise of Neoliberalim Feminism by Catherine Rottenberg

From Hillary Clinton to Ivanka Trump and from Emma Watson all the way to Beyoncé, more and more high-powered women are unabashedly identifying as feminists in the mainstream media. This book states that because neoliberalism reduces everything to market calculations it actually needs feminism in order to “solve” thorny issues related to reproduction and care.

Read a free chapter here.

8. Call Your “Mutha’” by Jane Caputi

8. Call Your “Mutha’” by Jane Caputi

This book looks at two major “myths” of the Earth, one ancient and one contemporary, and uses them to devise a manifesto for the survival of nature—which includes human beings—in our current ecological crisis.

Read a free chapter here.

9. Capable Women, Incapable States by Poulami Roychowdhury

In recent decades, the issue of gender-based violence has become heavily politicized in India. Yet, Indian law enforcement personnel continue to be biased against women and overburdened. This book asks how women claim rights within these conditions.

Read a free chapter here.

Featured image by Giacomo Ferroni

The post Nine books to make you think about gender politics in the political sphere appeared first on OUPblog.

February 27, 2021

Republicans at a crossroads? Probably not

How did the Republican Party arrive at such a confused and divided state that Senator John Thune (R-SD) had to ask whether it wanted “to be the party of limited government and fiscal responsibility, free markets, peace through strength and pro-life” or “the party of conspiracy theories and QAnon”? The question seems to suggest that the party has a binary choice, that they could be one or the other. In reality, the party is both, and it has been so for some time. The Republican Party we see today has been forty years in the making. We can track its development through three successive periods of change, from President Reagan’s landslide victory in 1980 to the “Republican Revolution” of 1994 to the Capitol insurrection on 6 January. Understanding this history will not help the party answer Senator Thune’s question. Indeed, it shows just how difficult it will be for Republicans to avoid further division or collapse altogether.

President Ronald Reagan’s election solidified the New Right. This coalition was held together by a shared antipathy toward the federal government, whether anger over forced desegregation, workplace safety regulation, environmental regulation, limits on prayer in school, or the legalization of abortion. The coalition was strengthened by a vast new infrastructure of conservative think tanks, foundations, political action committees, and advocacy groups that multiplied in the late 1970s and early 1980s in reaction to the civil rights revolution and cultural changes that began two decades earlier. In his first inaugural address, President Reagan told the nation, “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” He promised to get government out of the way so that Christians, the white majority, business owners, state governments, and others could retake their privileged place in American life. But without a supportive Congress, President Reagan could not deliver lasting change. This left many on the right even more disillusioned with national politics.

Newt Gingrich (R-GA) and others led the “Republican Revolution” in 1994, promising to succeed legislatively where President Reagan failed administratively. Their 10-point “Contract with America” aimed at nothing less than repristinating American government by pruning it back to its 19th Century capacity. Their more militant rhetoric included the new, decidedly insurrectionist interpretation of the 2nd Amendment, namely that the founders had written the amendment precisely so that individual citizens would have guns to use against government tyrants. And while Gingrich, Dick Armey (R-TX), and other leaders did claim that the time for insurrection had come, they expanded the Republican coalition to include militias, whose members were literally preparing for war with the federal government. The militias remained at the party’s margins only because mainstream Republicans did not yet share their dark conspiracy theories, including the belief that communists had taken control of the federal government or that the military was preparing internment camps for American citizens. (Congressional testimony by militia leaders in 1995 is particularly riveting.)

“Many on the right were horrified by the George W. Bush administration’s expansion of federal powers. … Disillusionment on the right intensified.”

But the Republican Revolution also failed to produce lasting change. The federal government did not shrink or roll back the left’s so-called “progressive rights,” and many on the right were horrified by the George W. Bush administration’s expansion of federal powers. A Republican president had failed to dismantle the administrative state. A Republican Congress had failed to restore the nation to its God-ordained place and condition. Disillusionment on the right intensified.

The most recent Republican revolution exploded into view in 2009 as the Tea Party and its armed wing, the Patriot Movement, rose to challenge government power. This time, it wasn’t led by the President or Congress but by Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, and Sean Hannity, and others who had no real interest in the hard work of governing. They simply recognized and harnessed the power of populist anger against government. Social media and an ever-expanding range of internet sources helped unify that anger.

The Tea Party and Patriot Movement held to most of the same principles that President Reagan and Speaker Gingrich had advanced, yet they reflected a far more militant turn in the party’s culture. Why? The primary change in the party, between 1994 and 2009, is that a critical mass of conservatives were embracing the very conspiracy theories that had marginalized militias in the 1990s. A critical mass came to believe that the opposition party wasn’t just wrong in its goals. It was an apocalyptic threat to the nation. And since 2009, militias have proliferated around the country; hundreds of so called “constitutional sheriffs” have pledge to defy any federal or state laws that they personally believe are unconstitutional.

“Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016 precisely because he understood the power and depth of anger and fear on the right, and he spent the next four years nurturing and provoking it rather than easing it.”

Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016 precisely because he understood the power and depth of anger and fear on the right, and he spent the next four years nurturing and provoking it rather than easing it. He and a new cadre of congressional Republicans welcomed white nationalists and militias not just to the outer wings of the party, but to the very center. They helped legitimize QAnon, Alex Jones, and other sources that would have made Republicans in the 1990s cringe. By the end of the Trump administration, a remarkable number of Republicans assumed that Democrats were not just advancing misguided policies; they were pedophiles and Satanists, hellbent on destroying the nation and its Judeo-Christian heritage.

Senator Thune is right in thinking that this is a perilous moment for the Republican Party. The party’s problem is that conspiracy-driven fear and anger have increasingly powered its electoral success. And over the last four years the party has almost unanimously endorsed this strategy, even if many of its leaders grumbled behind closed doors. The party cannot afford to turn its back on QAnon now, because it hasn’t built an alternative power source for its political engine. Indeed, Republicans who do try to run for national office on a cogent and principled platform are likely to be crushed in the primaries. (John Kasich (R-OH), we should remember, was part of the 1994 Republican Revolution. But when he ran for president in 2016 as a principled conservative, focused on governing, his campaign stood little chance.) Republican Party leaders are currently hoping that they can continue to harness the destructive, antigovernmental energy that defines a meaningful segment of their constituents, while distancing themselves from the Capitol insurrection on 6 January and avoiding violence in the future. That why House Republicans refused to censure Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) for supporting violent rhetoric but also refused to remove Representative Liz Cheney (R-WY), a more traditional, principled conservative, from her leadership position. Desperate congressional Republicans have chosen, for the moment, to promote both dangerous lies and conservative principles. This is a self-contradiction that cannot hold.

Featured image: Ronald Reagan from the National Archives (public domain)

The post Republicans at a crossroads? Probably not appeared first on OUPblog.

February 26, 2021

Introducing SHAPE: Q&A with Sophie Goldsworthy and Julia Black (part one)

OUP is excited to support the newly created SHAPE initiative—Social Sciences, Humanities, and the Arts for People and the Economy. SHAPE has been coined to enable us to clearly communicate the value that these disciplines bring to not only enriching the world in which we live, but also enhancing our understanding of it. The contributions that SHAPE subjects make are more important now than ever as they can help us to navigate how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the global economy, dramatically altered our quotidian routines, and changed the way we communicate with one another, against the backdrop of climate change and urgent calls to address structural injustice.

In the first instalment this two-part Q&A, we spoke to Sophie Goldsworthy, Editorial and Content Strategy Director here at OUP, and Professor Julia Black CBE FCA, Strategic Director of Innovation and Professor of Law at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and President-elect of the British Academy, to find out more about SHAPE and what it means to them.

Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about your background and current position, and what SHAPE means to you?Sophie Goldsworthy: I’ve worked in publishing for approaching 30 years, 25 of them at OUP. My first role at the Press was on the Literature list and I currently run our humanities, social sciences, and trade programmes in the UK, as well as directing Oxford’s content strategy more broadly across the research publishing business.

At a time when the content needs of the university sector are evolving, leading to shifts in research publishing, my role is about developing our focus and building data and evidence into our approach to content acquisition, more closely aligning commissioning with what librarians, researchers, and readers want, and working to maximise the reach, impact, and amplification of the scholarship we publish.

Oxford is the world’s largest university press, and SHAPE subjects sit at the very heart of our offering, giving us breadth which in turn underlines a complementary view of the subjects. SHAPE gives us a better way to articulate that mutual, porous relationship, helps us move past an arts/sciences dichotomy to a place where each enhances and supports the other.

Julia Black: My academic interests span social sciences and humanities. I focus on how governments and other organisations regulate behaviours, systems, and processes to address complex problems, such as environmental management, or financial stability, or AI, and what values guide, or should guide, those processes. Given that problems are multi-dimensional, trying to address them requires engaging with technical, scientific aspects of the issues as well as the social and ethical elements. As my principal research questions are always centred around people and organisations, social sciences and humanities dominate, but for me, it seems quite natural to engage with several disciplines, across SHAPE and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), in order to understand and address the multiple dimensions of a problem.

I’ve also always worked quite fluidly across the worlds of academia and public policy, and I’m constantly struck by the huge reliance which government places on social science and humanities in seeking guidance and evidence for its policies, and yet the contribution those disciplines can make, and are making, is often under-recognised and under-valued. And when I look beyond policy to the vibrancy of the arts, the richness of literature, the diversity of our society, and even to the structure and dynamics of our economy, SHAPE subjects are everywhere. So for me SHAPE is a way to celebrate the value of social sciences, humanities, and the arts, and to demonstrate their relevance and value to ourselves and to society. It’s also to encourage people to study them, and to build meaningful lives and contribute to society using the knowledge and skills they gain in doing so. For we need them now, more than ever.

What are the benefits in bringing together the arts, humanities, and social sciences disciplines under the SHAPE umbrella?“How we describe a thing has the potential to accord or diminish its power. At its heart, SHAPE offers us the opportunity to begin to tell the story of a set of subjects which might seem at first glance to be disparate.”

SG: How we describe a thing has the potential to accord or diminish its power. At its heart, SHAPE offers us the opportunity to begin to tell the story of a set of subjects which might seem at first glance to be disparate. It allows us to draw together the ways in which they contribute value to society, helping us make sense of the human experience, develop our understanding of global issues, and work to find solutions.

JB: SHAPE is offering social sciences, humanities, and the arts their own descriptor, providing a coherence to a heterogenous set of subjects in a way which celebrates their diversity but emphasises what connects them: a focus on the human world—on people and societies across time and space.

It’s important to emphasise that we are not “setting up” social sciences, humanities, and the arts in opposition to STEM. SHAPE subjects have their own value which is on a par with STEM, they are just differently focused: on the human world, rather than the natural or physical worlds. There are areas within each where they operate largely separately, but if we want to understand how humans interact with the natural and physical world, then we need the insights gained from connecting both sets of disciplines. There are also opportunities to use the knowledge and insights from each to inform the other.

How can SHAPE and STEM disciplines complement each other in our pursuit of knowledge?SG: The pandemic has reinforced how essential STEM subjects are, as we look to medical and technical solutions: witness only the breath-taking speed at which vaccines have been developed. But SHAPE disciplines complement STEM in myriad ways—and conversely leaving them out of the mix can have troubling implications.

We might need to draw on behavioural economics and “nudge” theory to help influence how people act, changing the message around mask wearing from “protect yourself” to “protect others,” for example. Or to take a holistic approach to data interpretation to circumnavigate structural inequalities, where the price we otherwise pay is a high one. The past year has been full of stories about “one size fits all” PPE that leaves female health workers poorly protected, or remote education initiatives that overlook those children for whom a school lunch provides the only meal of the day.

At its most straightforward, learning the stories of past pandemics can enlighten us in the present. How and why do conspiracy theories and misinformation proliferate in an outbreak, for example, and what should we learn as we navigate precisely that set of circumstances all over again in the rollout of a new vaccination programme.

“SHAPE subjects can complement STEM, and STEM subjects can complement SHAPE. In some cases, one discipline may be more in the lead than the other, but the synergies still exist.”

JB: SHAPE subjects can complement STEM, and STEM subjects can complement SHAPE. In some cases, one discipline may be more in the lead than the other, but the synergies still exist. Some SHAPE subjects are through their approaches closer to STEM, for example in their use of quantitative and statistical methodologies and data analytics, and some directly cross the boundaries, such as mental health and wellbeing. However, we could do more to illustrate how STEM and SHAPE subjects can together enhance our knowledge, and what we create from that knowledge.

Some have asked why we aren’t satisfied with the term STEAM to describe this interaction. The answer is that STEAM focuses only on the interaction of art and design with STEM subjects, in other words it only looks at the “A” in SHAPE, not the “S” and the ”H.” Whilst art and design are hugely valuable to the design of products developed by technology, or as ways to visualise the natural and physical worlds, for example, there are many more benefits to be gained from the interaction of STEM disciplines across the social sciences, humanities and the arts. Changes in an ecosystem are frequently rooted in human behaviour; managing pandemics requires knowledge of history, cultures and behaviours, as well as economics and logistics; the search engines we have become so reliant on use natural language programming based on linguistics; and for science and technology to be legitimate it is imperative that it is developed and used in ways which are aligned with our ethics and values.

But these examples are the tip of the iceberg; there are multiple instances where the insights of each enhances the other, and it is often when they are combined that truly transformative developments in our knowledge, understanding, innovation, and creativity can occur.

Featured image by Janko Ferlič on Unsplash

The post Introducing SHAPE: Q&A with Sophie Goldsworthy and Julia Black (part one) appeared first on OUPblog.

The impact of heat stress on beef cattle: how can shade help? [infographic]

Cattle well-being and performance is negatively impacted by extreme heat stress. Introducing shade as a mechanism to mitigate this is one way to offer relief.

Heat waves in the US have caused widespread death in cattle. After the 1995 heat event in Iowa, it was found that non-shaded lots experienced a much higher death toll than shaded lots (4.8% and 0.2% respectively). Cattle that do survive periods of extreme heat experience reduced productivity, resulting in economic loss. In 2003, a study found that an estimated $1.69-2.36 billion was lost in the livestock industry due to heat stress.

As well as the effect on the economy, global temperature increase has become another driving force behind discussions on heat stress and animal welfare and has cast a spotlight on the importance of developing and implementing mitigation strategies, such a shading. Whilst well-reviewed in dairy cows, the research on using shade as a stress reduction strategy in beef cattle is still largely inconclusive. There is some evidence to suggest that shade does reduce heat stress, but industry guidelines are not consistent and as a result, producers can be reluctant to implement these strategies.

Animal welfare is not just about the productivity of livestock. Polsky and von Keyserlingk (2017) illustrated that when a dairy cow is not able to find shade in a hot climate the cow’s ability to express natural behaviors is impacted. The lack of shade will subsequently affect the performance of the cow and reduce productivity. Although based on a dairy cow, these findings have also been applied to beef cows on pasture. Increased attention to their welfare ensures cattle will perform more successfully.

Explore the infographic and related articles below to find out more.

Take a further look into this topic with related articles from the Journal of Animal Science and Translational Animal Science:

“Heat stress alleviation and dynamic temperature measurement for growing beef cattle”, by Sheyenne M Augenstein, Meredith A Harrison, Sarah C Klopatek, and James W Oltjen. (Translational Animal Science, Volume 4, Issue Supplement_1, December 2020, Pages S178–S181.)“The effect of Brahman genes on body temperature plasticity of heifers on pasture under heat stress”, by Raluca G Mateescu, Kaitlyn M Sarlo-Davila, Serdal Dikmen, Eduardo Rodriguez, and Pascal A Oltenacu. (Journal of Animal Science, Volume 98, Issue 5, May 2020, skaa126.)“Supplementing an immunomodulatory feed ingredient to improve thermoregulation and performance of finishing beef cattle under heat stress conditions”, by Eduardo A Colombo, Reinaldo F Cooke, Allison A Millican, Kelsey M Schubach, Giovanna N Scatolin, Bruna Rett, and Alice P Brandão. (Journal of Animal Science, Volume 97, Issue 10, October 2019, Pages 4085–4092.)The post The impact of heat stress on beef cattle: how can shade help? [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 25, 2021

Beyond polemics: debating God in early modern India

The early modern period in India (roughly from 1550 to 1750) has been increasingly understood as a time of heightened religious self-awareness—the fertile soil from which Hinduism emerged as a unified world religion. Yet it was also a tumultuous period of intense rivalry across scholarly and religious communities. Scholars debated one another on matters of doctrine and religious practice, turning as well a critical gaze toward the founding figures of their respective schools of thought. Traditions diversified internally and new movements emerged that attempted to dislodge their predecessors. Polemical tracts circulated across wide networks of Hindu intellectuals who were writing principally in Sanskrit.

One area in which this contentious atmosphere of debate was evident was theology—the discourse on God within the purview of the manifold and long-standing tradition of Vedānta. On the eve of the 16th century, Vedānta was essentially a bastion of scholars who interpreted canonical texts as promoting the view that God is Viṣṇu (one of the major Hindu deities). The flowering of Vaiṣṇava scholarship in this period, particularly in South India, was partly engendered by shifts in state policy and patronage practices that favoured Vaiṣṇava scholars and institutions to the detriment of other religious communities. In this context of religious tensions and inter-scholarly disputes, a major break occurred towards the end of the 16th century.

Appaya Dīkṣita (1520-1593) was a smārta brahmin from Tamil Nadu (South India) and a scholar of polymathic erudition who devoted a large share of his long and prolific career to writing about Śaivism, a major religious tradition centred on Śiva (another major Hindu deity). Across nearly three decades, Appaya devoted himself to an ambitious theological project under the patronage of an independent Śaiva ruler: that of displacing the dominant Vaiṣṇava theology of Vedānta in favour of a Śaiva theology that would effectively promote God’s unity. His wide-ranging writings inspired a kind of revolution in Vedānta theology that would last until the 20th century.

A devotee of Śiva by upbringing, Appaya saw himself primarily as a representative of Advaita Vedānta, the “pure non-dualist” school of Vedānta, which holds the view that the supreme reality or godhead is ultimately beyond form, thought, and language. Appaya’s early Śaiva writings were unmistakably polemical, at times adopting a rather aggressive rhetoric against Vaiṣṇavas:

The Vedas openly declare that only You, Śiva, transcend the universe and ought to be worshipped by all people, and yet, alas, rogues dispute even that. What is this life of them, lost because of their irrepressible need to offend You? [Only] death is considered to expiate those who listen to their words.

In these works of relative jeunesse, Appaya aims to undermine Vaiṣṇava superiority and silence the “blabbering of these evil-minded people” who deny the value of worshiping Śiva. His staunch position that Śiva—not Viṣṇu—is the supreme reality and the only deity that ought to be worshipped was unprecedented in the realm of Vedānta theology in terms of its scope and influence.

As his career progressed, however, Appaya shifted his focus away from polemics to embrace a more comprehensive view of God’s unity. In his later works, he displays a remarkably tolerant attitude towards Viṣṇu, even insisting that Viṣṇu’s divinity is on par with Śiva. In his own words:

My tongue could not move to assert…that the revered Viṣṇu is merely an individual being [and not a divinity]. If I did so, my head would burst into a hundred pieces and I would be [guilty] of treachery towards the Vedas, the sages and the deities.

Unlike Vaiṣṇavas before him, who had unanimously claimed that Śiva is merely an exalted being with no divine qualities, Appaya now held that Viṣṇu is just as much divine as Śiva. Reading his entire Śaiva oeuvre, it becomes clear that Appaya’s early polemical tracts were intent on defending Śaiva religion against Vaiṣṇava invectives rather than gratuitously attacking Vaiṣṇavas. Indeed, he explicitly demands that the divinity of Śiva be recognised just as he himself acknowledges Viṣṇu’s divinity.

Appaya’s attempt at developing a theological model that regards all Hindu deities as divine aspects of the same non-dual reality not only attracted criticism from Vaiṣṇava scholars, but also from Advaita Vedāntins and Śaivas who considered his proposal too radical. Yet his project was successful to the extent that it left a deep impression on, and effectively transformed the theological landscape of, early modern India. For Appaya, it is in the end unimportant whether one prefers to worship Śiva or Viṣṇu. Pure non-dualism, in his view, provides an encompassing approach to reality that can accommodate and integrate all philosophical views and religious approaches. Debates about what deity is supreme are not productive insofar as all deities are ultimately expressions of the same non-dual, ineffable reality. If it was indeed important for Appaya to defend Śaiva religion in the face of threatening encroachments on religious freedom, it was all the more crucial to acknowledge that no religious approach can supersede other stances. In this sense, Appaya was an early precursor of the view that Hinduism encompasses and in effect transcends all religions—a view that would later be popularly promulgated by Hindu reformers such as Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and other defenders of religious freedom in colonial India.

Feature image by Balaji Srinivasan

The post Beyond polemics: debating God in early modern India appeared first on OUPblog.

February 24, 2021

Darwin’s queer plots in The Descent of Man

This year, LGBT+ History Month coincides with the 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s momentous sexological work The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, originally published on 24 February 1871. The occasion prompts reflection on Darwin’s highly equivocal handling of sex variations in the natural world, including intersexualities (“hermaphroditism”), transformations of sex, and non-reproductive sexual behaviours.

Descent has long been considered a landmark text in the history of science for two main reasons. It is the book in which Darwin fully extended his theory of natural selection to humans. It also contains the lengthiest exposition of his second major theory of evolutionary change, sexual selection, the subject occupying around two thirds of Descent. Darwin devised sexual selection to account for the development of exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics (such as the peacock’s tail), otherwise a hinderance to an individual’s chances of survival. He posited two mechanisms by which such characteristics evolved outside the struggle for survival: the competition of males as they vie for reproductive access to females either through physical combat or through courtship displays, and the ability of females to choose those males whose competitive efforts impress them most. In Darwin’s highly selective, and highly stereotyped, construal of “nature’s courtship plot” (to quote literary scholar Ruth Bernard Yeazell), only the most combative males and the fussiest females get to partake in the continuance of their species.

Ostensibly, there appears to be little room for queer bodies, minds, and behaviours in this schema. But a close reading of Descent, as well as Darwin’s other published and unpublished writings, shows that this is not the case. It is indubitably the case that the repressive gender and sexual mores of the Victorian age meant that he routinely couched descriptions of sex variations in pejorative terms. But he was also an astute naturalist and recognized that sex differences and sexual behaviours were subject to innumerable variations, just as other organic structures, instincts, and behaviours were.

Ostensibly, there appears to be little room for queer bodies, minds, and behaviours in this schema. But a close reading of Descent, as well as Darwin’s other published and unpublished writings, shows that this is not the case. It is indubitably the case that the repressive gender and sexual mores of the Victorian age meant that he routinely couched descriptions of sex variations in pejorative terms. But he was also an astute naturalist and recognized that sex differences and sexual behaviours were subject to innumerable variations, just as other organic structures, instincts, and behaviours were.

Indeed, Darwin believed that all vertebrates, including humans, were essentially dual-sexed, having originated from a common hermaphrodite ancestor. Jottings by the young, Beagle-fresh Darwin entered in his (unpublished) notebooks around 1838 evidence his early commitment to the ubiquity of hermaphroditism in the natural world as he grappled to situate a variety of sex variations within his developing evolutionism, including the rearing of a queen bee from the pupae of a worker, the assumption of male-typical plumage by certain female birds, and the occurrence of homologous sexual anatomical structures. “Every animal surely is hermaphrodite,” he wrote, repeating the assertion on multiple occasions.

Ever restrained in his choice of words on sex-related topics in his published works, the indefatigably prudish Darwin held back from making an explicit statement, as he had earlier made in the privacy of his notebooks, that all individuals, including humans, were essentially hermaphrodites. Nonetheless, the perennial co-existence of female and male characteristics in every individual remained an important facet of his evolutionism, the potential queerness of the proposition offset by Darwin’s insistence that characteristics of the opposite sex usually remained only in a latent state. Only in exceptional circumstances, he argued, were they expressed.

In Descent, Darwin extended his analysis to fully embrace a grand narrative of the evolution of sex, suggesting that hermaphroditism was the primordial condition of humanity’s remotest ancestor. Such a deep, and largely unspecified, evolutionary narrative, suggesting as it did an infinitely longer timespan than Darwin’s assertion that humans were evolved from apes, was open to numerous interpretations and projections, many of them potentially raising questions of morality and respectability in Victorian science writing that Darwin was undoubtedly keen to avoid. He deployed various conceptual and rhetorical strategies that muted the potential for such interpretations of his evolutionism. Sometimes he was dismissive. For example, he recognized that birds of the same sex sometimes lived in pairs or small groups, but added that they were “of course not truly paired.” Other times he was evasive. Discussing how “vitiated” instincts affected the reproductive habits of birds, he remarked that he could give “sufficient proofs” with regard to pigeons and fowls, but added “they cannot be here related.” When it came to humans, he was disparaging. He even used draconian rhetoric largely derived from long-standing theological traditions, writing of the “unnatural crimes” and “immorality” of indigenous peoples (“savages”) as well as the “extreme sensuality” of the ancient Greeks.

Darwin’s reticence to fully theorize occurrences of intersexualities, sex changes, and non-reproductive sexual behaviours in humans and non-human animals, combined with the laboured descriptions of sex differences that constitute his lengthy discussion of sexual selection, entailed that Descent was generally received positively and without censure. Nonetheless, despite the ambiguities of his approach to sex variations, a new generation of Darwinian sexologists extended evolutionary notions of sex differences and sexualities ever deeper into the realms of human psychology and behaviour. The Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, counted Descent among the ten most important books he knew of. For his part, the homophile German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, writing in 1914, lauded Darwin above others for establishing a new biological sexology that had borne fruit, “even in the stony earth of England.”

The post Darwin’s queer plots in The Descent of Man appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers