Oxford University Press's Blog, page 112

April 11, 2021

Does humor have a temperature? Movie comedy in Norway and Brazil

Can humor have a temperature? Do some like their comedy hot or cold? A quick survey of movies from Norway and Brazil invites us to consider how climate and geography can affect a people’s sense of humor. Let’s start with a joke from the Nordic countries:

A Swede and a Norwegian decide to drink. They sit across the table with more than a few bottles of aquavit between them, knocking off shot after shot without a word. After three hours, the Norwegian lifts a glass and says, “Skol!” to which the Swede frowns in disapproval, saying, “Did we come here to talk or to drink?”

Like most bar jokes, this one hinges on stereotypes, but cultural clichés can be revealing. Swedes and Norwegians laugh at qualities they find amusing in their own behavior: the drinking, for example, and the long stretches of uncommunicative silence punctuated by an unexpected outburst. There’s something oddly funny here, perhaps ironic, detached, understated, cool. We find a good deal of this icy humor in comedies from Norway.

The Bothersome Man (Den brysomme mannen, 2006) opens with a wide shot of a desolate landscape under dark clouds. A man slowly climbs a ladder and hangs a sign above a rusty gas pump. After a full minute and a half, we glimpse a bus in the distance. It takes another minute to reach us, when a younger man—its only passenger—steps out. The bus departs, leaving him to survey the barren panorama until he sees the sign: “Welcome.” More time passes before the first man appears from behind the pump. “Hi,” he says, and, without another word, ascends the ladder to remove the sign. “Was the banner for me?” the young man asks. “Yes,” comes the response. “I like making a bit of a fuss.” Then the sign comes down.

It takes more than four minutes for the scene to unroll. Norway’s open spaces and gloomy climate are part of the joke. So is the older man’s grudging use of language, like the Norwegian in the bar joke. His idea of a fuss is a one-word sign in the middle of nowhere.

Bent Hamer’s Kitchen Stories (Salmer fra kjøkkenet, 2003) is a comedy of national identities. The Swedes, famous for their efficient studies, have come to analyze the kitchen habits of Norwegian males for the purpose of improving their domestic products. Isak, a Norwegian, resents this arrangement, but he needs the money. He makes remarks about the oddity of Swedish words, like “smörgåsbord,” and the unnatural silence of his observer (with a wry allusion, perhaps, to Swedish neutrality during World War II). Meanwhile, Folke, the Swede, finds some peculiarities in his Norwegian host. When the phone rings, Isak fails to pick it up. “Why don’t you answer?” Folke asks. Isak knows a neighbor has called to say that he’ll be over for coffee, but why pay the phone company for that information?

Quirky behavior is a staple of Norwegian comedy. Watch this scene from Trollhunters (Trolljegeren, 2010), an oddball fantasy in which an ordinarily tight-lipped Norwegian is interviewed about his peculiar job. The government has hired him to hunt down trolls, which are killing livestock and ruining tourism in the north. What makes the scene so funny is his matter-of-fact description of these ludicrously dangerous creatures from Norse mythology. What the hunter likes least about his job is filling out a “Slayed Troll Form” every time he scores a hit.

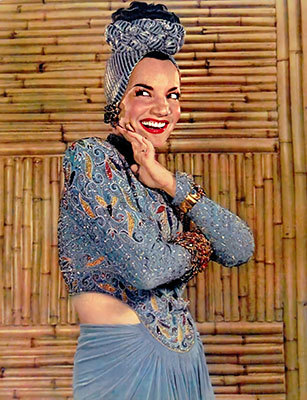

By New York Sunday News, via Wikimedia Commons

By New York Sunday News, via Wikimedia CommonsCompare these laconic characters and deadpan scenes to those of the chanchada, a popular genre of Brazilian cinema. Carmen Miranda typifies the carnivalesque vitality of these films. With her chica-chica-boom-chic gyrations and her tutti-frutti hat, she embodied Latina energy from the 1930s through the 1950s. During this “golden age,” and even later, the film industry in Brazil played a canny shadow game with Hollywood by alternately mimicking and mocking movies from north of the border. Codfish (Bacalhao, 1975), a parody of Jaws, is a hilarious example.

By the seventies, when Brazilian cinema became more openly political, comedy acquired a darker tone. In How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês, 1971), the title character ends up being cooked in a pot and eaten by a sixteenth-century Tupinambá tribe. This fanciful account of cannibalism, an historical fact, becomes an ironic trope for colonial consumerism in reverse: the indigenous Brazilians devour their would-be predators. Yet, while such films clearly have a serious, even grotesque quality (they were variously dubbed Cinema Novo, Tropicalism, and even “Mouth of Garbage films”), their humor is manic, hyper-heated, in contrast to their deadpan Norwegian counterparts.

Like much comedy, Brazilian movies tend to feature figures from the lower classes, poor people trying to get ahead, often by illegal means. Guel Arraes sets A Dog’s Will (O Auto da Campadecida, 2000) in the rural northeast, where two bumbling low-life bandits, João and Chicó, trick their way through a throng of scoundrels and fools. Jorge Furtado’s The Man Who Copied (O Homem Que Copiava, 2003) takes place in urban Brazil on a slightly higher rung on the social ladder. The man of the title is a convenience store employee named André, whose voice-over narration sounds like a how-to manual for getting rich. André begins his rise to prosperity by photocopying his boss’s $50 bill, using it to buy a winning lottery ticket. This takes him through the crazy antics of a bank heist, a shopping spree, and layers of deception and betrayal. Beneath Furtado’s playful mixture of genre conventions—Hollywood’s screwball romance and film noir, Brazil’s chanchada and Cinema Novo—lies a serious indictment of the culture of wealth based on greed and deceit.

If comedy is a matter of excess, the actors in these Brazilian films push “Latino passion” to a feverish pitch while their Norwegian counterparts endure a kind of Nordic hypothermia. Both practice the art of exaggeration, a form of self-correction, demonstrating that humor can be both a mirror and a medicine. Or a cultural thermometer.

Featured image by Jarosław Kwoczała

The post Does humor have a temperature? Movie comedy in Norway and Brazil appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2021

The Turing test is not about AI: it is about our tendency to project humanity onto things

As Artificial Intelligence technologies enter into more and more facets of our everyday life, we are growing accustomed to the idea of machines talking directly to us. Voice assistants such as Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri inhabit domestic and professional environments, chatbots are standard in customer care, apps such as Replika offer virtual avatars to provide companionship, and even the Twitter account of NASA’s Perseverance mission sends updates in first person, as though they were posted directly by the rover from the surface of Mars.

These new situations and opportunities make Alan Turing’s imitation game—the Turing test, as commonly called—more relevant than ever before. Only, not in the sense through which the test is usually interpreted.

The Turing test, in fact, is generally regarded as a way to assess the proficiency of AI. Its real “message,” however, does not have much to do with the intelligence of machines, but rather with our relationship with them. The question, Turing told us, is not if machines are able or not to think. It is if we believe them to do so—in other words, if we are prepared to accept the machines’ behaviour as intelligent. Once we take this point of view, we realize that that our interactions with AI are shaped by our tendency to project humanity onto things: this is one of the least understood, but most interesting implications of the Turing test.

AI, seen by humansThe paper that introduced the idea of the test, Turing’s “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” starts with the question “Can machines think?” Yet, Turing immediately proceeds to declare this question of little use: it would be impossible, he reasons, to find an agreement on what we mean with the word “thinking.” He proposes therefore to replace this question with a practical experiment, the Turing test, in which a human interrogator exchanges written messages with an unknown partner to find out if this is a human or a machine. Although the test is usually discussed as a threshold to assess if artificial intelligence has been reached, such an approach misses its most important implication. Assigning to a human interrogator the responsibility to evaluate the behaviour of the machine, Alan Turing refuses to define AI in absolute terms and considers instead how humans perceive and understand AI.

In this sense, Turing’s proposal located the prospects of AI not just in improvements of hardware and software, but in a more complex scenario emerging from the interaction between humans and computers. By placing humans at the centre of its design, the Turing test provided a context wherein AI technologies could be conceived in terms of their credibility to human users.

I believe in you, Alexa: the example of voice assistantsThe example of voice assistants, such as Alexa or Siri, helps us appreciate the implications of the Turing Test as seen from this point of view. In order to ensure that voice assistants reply with apparent sagacity to users, Amazon and Apple assign to dedicated creative teams the task of scripting appropriate responses. Their work is facilitated by data collected by recording users’ conversations with these systems, which help writers anticipate frequent questions and queries.

The seemingly clever replies that result from this work are actually one of the least “smart” things Siri can do. The activation of scripted responses is, in fact, exceedingly simple at a technical level: it is more similar to dramaturgical scripting and does not foreground complex social behaviour from the part of the machine. Yet, the ironic tone of many such replies is striking to many users, and is often indicated as evidence of voice assistants’ intelligent skills.

Author’s conversation with Siri. The assistant’s inside joke points to the long tradition of reflections about machines, intelligence and awareness—all the way back to Turing’s 1950 paper, in which he argues that the question of whether machines can “think” is irrelevant.

Author’s conversation with Siri. The assistant’s inside joke points to the long tradition of reflections about machines, intelligence and awareness—all the way back to Turing’s 1950 paper, in which he argues that the question of whether machines can “think” is irrelevant.In other words, the least complex feats of AI systems may appear to users as if they were evidence of significant technical achievements in AI. This example shows that our perception of AI technologies does not correspond to their internal functioning: it always depends on the subjectivity our own gaze and on the all-too-human tendency to attribute sociality and agency to things.

Therefore, what the Turing test, and AI more broadly, call into question is the essence of who we are. But not because, as suggested by posthumanist theory, AI erodes the boundaries between humans and machines. Rather, the key message of the Turing test is that our vulnerability to being deceived is part of what defines us. Humans have a distinct capacity to project intention, intelligence, and emotions onto others. This is a burden but also a resource: after all, it is what makes us capable of entertaining meaningful social interactions with others. But it also makes us prone to project intelligence onto non-human interlocutors that simulate intention, sociality, and emotions.

Featured image by Possessed Photography

The post The Turing test is not about AI: it is about our tendency to project humanity onto things appeared first on OUPblog.

April 9, 2021

Theodore Roosevelt’s religious tolerance

Theodore Roosevelt is everywhere. Most famously, his stone face stares out from South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore. In addition, an island, national park, and aircraft carrier bear his name; university institutes and scholarly associations honor his legacy; and (in mascot form) he even runs the perimeter of the Washington Nationals stadium during the fourth inning of the team’s baseball games.

Roosevelt’s ubiquity is not without reason. His achievements as a hunter, naturalist, historian, soldier, statesman, explorer—and self-promoter—are myriad. Yet scholars are still discovering new features of his important legacy, including his spiritual life and place on the American religious landscape during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. One of the most important but least recognized aspects of this dimension of his life are Roosevelt’s ecumenical convictions and his promotion of marginalized religious groups. Through Roosevelt’s influence, Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Unitarians moved a little closer toward the American religious mainstream.

A prefatory word on Roosevelt’s spiritual pilgrimage is necessary. Although his own interior religious life was private, Roosevelt moved from a traditional Presbyterian and Dutch Reformed youthful faith to a more detached but still respectful outlook as an adult. As a college student he wrote explicitly of his faith in Jesus Christ and his hope of heaven. Lending support to this devotional posture, he taught a Sunday School class for underprivileged children all four years of his time at Harvard. Following the tragic deaths of his wife and mother on the same day in 1884, however, Roosevelt evinced more skepticism. He never regained his sturdy faith in the afterlife, he denied he was an orthodox believer, and he criticized the more conservative Protestant groups as backward and intolerant.

“Through Roosevelt’s influence, Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Unitarians moved a little closer toward the American religious mainstream.”

This broader outlook informed his ecumenism and support for religious minorities. (A desire to appeal to a variety of voters probably did too.) First, as president, Roosevelt appointed the first American Jew to a cabinet position when he made Oscar Straus Secretary of Labor and Commerce in 1906. Straus’s appointment came at a time when Jews were suffering persecution in foreign lands and were often looked on with distrust when they immigrated to the United States. Even though Roosevelt sometimes deployed anti-Semitic stereotypes himself, he wanted American Jews to believe that they were not going to experience discrimination in their adopted homeland.

Roosevelt’s moves on behalf of Mormonism occurred through his support of Utah Senator Reed Smoot, an Apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). Most non-Mormon Americans reviled the LDS throughout the nineteenth century. Mainstream Christians associated Mormon polygamy with barbarity and even slavery. After suffering a series of legal defeats in the Gilded Age, LDS leaders renounced polygamy in 1890. The abandonment of polygamy did not usher in a new era of tolerance, however. Although Utah sent Smoot to the Senate in 1903, he was subjected to sporadic hearings over the next four years regarding his fitness for office. While Roosevelt never approved of Mormonism, he came to believe that Smoot should not be punished for his religious affiliation. (It also helped that the senator was a Republican.) When the final hearings were being held in early 1907, Roosevelt on several occasions greeted Smoot loudly in public to signal his support. Several years later he explained, “if Mr Smoot…had obeyed the law…it would be an outrage to turn him out because of his religious belief.”

Protestant-Catholic antipathy had deep roots in the United States. Protestants of most varieties disliked Catholic theology, assumed Catholics were primarily loyal to the pope, distrusted parochial schools, denounced papal warnings about democracy, and worried about the Catholic immigrants flooding the nation’s shores in the late nineteenth century. Catholic priests were objects of special suspicion because they were celibate, conducted services in Latin, participated in a hierarchical order, and supposedly commanded the unquestioning loyalty of their flock. Although Roosevelt disliked elements of Catholicism, he also offered his hearty support to Catholic leaders who attempted to accommodate their faith to conditions in the republican United States. In 1911 he stated, “I spent a night with Father Curran at the Wilkes-Barre coal fields, and met some thirty priests at his house at lunch…. I really cannot say that I was very much concerned one way or the other with their theology … their work was what appealed to me in practical fashion.” If actions speak louder than words, Roosevelt followed through as well. When he went on a trip to South America in 1913 that culminated in his exploring the unknown River of Doubt, one of his traveling companions was a Catholic priest. Father John Zahm earned Roosevelt’s approval because he tried to reconcile traditional Catholic theology and modern science and had supported Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in 1912.

“Roosevelt argued that asking religious questions of a [presidential] candidate was un-American”

Unitarians were not marginalized in the same sense that Jews, Mormons, and Catholics were. Nevertheless, traditional Protestants deplored their theology, which denied that Jesus was God. When Roosevelt’s friend William Howard Taft ran for president in 1908, his Unitarianism became a controversial feature of the campaign. Some editors of religious periodicals urged their readers not to vote for a man who denied Christ’s divinity. Although Roosevelt waited until after the election to respond publicly to these attacks on his friend, his subsequent open letter left no doubt about his convictions. Roosevelt argued that asking religious questions of a candidate was un-American, that Taft’s theology was irrelevant to his qualifications for office, and that one day Catholics and Jews would come to occupy the presidency.

Roosevelt’s ecumenism had its limits. He was ambivalent about Islam, loathed what he thought of as primitive African religions, patronized Native American beliefs, and criticized agnostics and atheists. When he lampooned traditional Protestants and conservative Catholics for being narrow-minded, they could have easily returned the favor. They doubtless distrusted a man who seemed to have few theological beliefs at all and who preached what they would have regarded as a mushy tolerance. But for Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Unitarians, Roosevelt’s efforts on behalf of religious ecumenism helped their groups edge a little closer to the American religious mainstream. Although not as widely recognized as his other accomplishments, Roosevelt’s religious tolerance is also part of his legacy.

Featured image: Theodore Roosevelt, 1910. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

The post Theodore Roosevelt’s religious tolerance appeared first on OUPblog.

April 7, 2021

Wallowing deeper and deeper in the garbage can (part three)

This is the end of a long ill-smelling series. Trash and rubbish have been discussed (see the posts for the last two weeks, part one and part two), offal and refuse made their brief appearance and were sent to an etymological incinerator, and now garbage will keep us busy for a short time and join its disreputable fellows.

I have nothing new to say about trash, though I would very much like to know what specialists in Romance and English historical linguistics think about Leo Spitzer’s idea of the origin of rubbish. Several lines of investigation lead from rubbish to other words. According to the accepted point of view (which ignores Spitzer’s suggestion), rubbish may go back to the plural of the Anglo-Norman word that served as the root of rubble. Rubbish, allegedly, modified its former Romance ending –ous to the familiar English suffix –ish, while rubble has the root rob-, as in Old French robe “spoils.” Thus, in broad outline: rubbish from rubble, and rubble from robe. Where, one wonders, does robe “garment” come in?

A ceremonial robe, with no robbery involved. (Via Wikimedia Commons, )

A ceremonial robe, with no robbery involved. (Via Wikimedia Commons, )Robe is a Romance word (in Middle English, it is from Old French), related to rob. Rob also came to English from French, but in the Romance languages, it is a loan from Germanic, as shown by German rauben “to rob” and the archaic English verb reave, today familiar only from bereave. Obtaining clothes, regarded as spoils, is a familiar motif in ancient and medieval tales. To take off the clothes of a vanquished enemy (alive or dead) and leave him naked was the highest degree of humiliation for the losing party. In Old Icelandic, a special verb existed for divesting a corpse on the battlefield. The original sense of the Indo-European verb, represented by reave, must have been “break; tear; remove with force.” The link between it and rubble will survive, even if rubbish and rubble are not related.

Since outside the bow-wow and ga-ga group, the existence of sound imitation and sound symbolism is hard to prove, one can at best risk saying that the group r-b suggested to speakers the idea of tearing, scraping, and all kinds of abrasion. The “ultimate source” of rub and its near-homonyms elsewhere in Germanic is unknown (German reiben “to rub” once began with w- and is not related). Rabble and rap are, most likely, imitative, and so is perhaps riffraff. Dictionaries can say almost nothing about rip and ruffle. The same impulse may have given rise to rubble, rubbish, and some other r-b, r-p words, but even if they began their way as onomatopes, the group viewed in its entirety is so heterogeneous that each word appears to be isolated. Such is the shortest history of etymological rubbish.

Of all the English words for “waste” garbage is perhaps the most obscure. Judging by its suffix (compare voyage, umbrage), it has a French look. Its appearance in texts does not antedate late Middle English, and its earliest recorded sense is “offal of an animal, entrails of fowls,” which confirms the statement made at the beginning of this series: though at present, trash, rubbish, and some of their synonyms refer to “waste matter in general,” in the past, all of them had a more concrete sense.

At first blush, garbage is the closest kin of garble “distort the meaning,” the verb that goes back to an Arabic term of Mediterranean trade. It once meant “to remove the rubbish from an imported consignment of spices”; for chronological reasons, it could not become the source of garbage. The two words were later associated because they sound so much alike, and both have negative connotations. Here again we find ourselves in an onomatopoeic quagmire, but in place of r-b words, g-r and gr-b turn up at every step. Such formations refer to grabbing, scratching (like German krabbeln), disorderly movements, and the like. French grabuge means “confusion; wrangling” and is probably a borrowing from North Italian (though some earlier dictionaries reconstructed the opposite direction: to Italian from French). Incidentally, grab is related to Russian grabit “to rob,” and we return to rubbish, rubble, and its obscure kin.

A garb and a sheaf: etymological siblings of garbage? (Images by (L) hanen souhail (CC0), (R) Zorba the Geek (CC BY-SA 2.0))

A garb and a sheaf: etymological siblings of garbage? (Images by (L) hanen souhail (CC0), (R) Zorba the Geek (CC BY-SA 2.0))Alongside garb “dress” (a Romance word of ultimately Germanic origin: something made, prepared, adorned), English has garb “sheaf,” a cognate of German Garbe (the same meaning). Garb1 and garb2 may be “obscurely related,” as dictionaries like to call such cases. Walter W. Skeat thought that a sheaf was something that could be “grabbed,” and German etymologists share this opinion. But garbage as “handful” does not sound convincing. Even if it is correct that garbage emerged as a word of sound-imitative origin, with gr-b referring to things grabbed, selected, sorted out, and thrown away, such was only the remote beginning of the noun, whose root traveled between Germanic and Romance and which in the Romance-speaking world, too, occasionally crossed language borders.

This is what The Century Dictionary says about garbage (with the abbreviations expanded):

“The form is like Old French garbage, gerbage, Medieval Latin garbagium, a tribute or tax paid in sheaves, from Old French garbe, Medieval Latin garba, a sheaf; there may be a connection similar to that shown in German Bündel, the entrails of fish, literally a bundle, = Engl. bundle. There can be no connection with garble, a much later word in English, and one which could not have produced the form garbage.”

Jacob Verdam (1845-1919). (Via Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Jacob Verdam (1845-1919). (Via Wikimedia Commons, CC0)Skeat’s influence on this etymology is obvious, but the formulation is not trivial, and the result sounds promising.

By way of conclusion, I would like to mention Dutch karwei “entrails of animals given to the hounds.” Two excellent etymological dictionaries of Dutch exist. Both give nearly the same explanation of karwei. Those explanations would take us too far afield but add nothing to what has been said above, because the authors’ reasoning is entirely different from that found in English sources. However, once, in 1890, Jacob Verdam, one of the greatest experts in the history of Dutch, compared karwei and English garbage. (The reference will be found in my Bibliography of English Etymology.) The similarity is striking. Are the current explanations of carwei a product of folk etymology? Verdam’s suggestion has never been noticed, let alone discussed in any detail.

And here comes my plea. The number of people reading this blog is sometimes as high as a thousand (in the past, some posts attracted much larger crowds, but I am not speaking about exceptions). Romance scholars have rarely responded to it. By contrast, specialists in Dutch and Frisian have more than once pointed to the facts I either did not mention or did not know. In the series on trash and its synonyms, I called attention to Spitzer’s hypothesis on the origin of English rubbish and now I have unearthed Verdam’s idea that Dutch karwei may have something in common with English garbage. Perhaps someone will comment on the forgotten findings by those two outstanding researchers. Resuscitating valuable ideas buried in the depths of old journals is an important part of etymologists’ work. Convincing refutation is as valuable as agreement.

Celebrating the Dutch word KARWEI. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Celebrating the Dutch word KARWEI. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, CC0)Next week, I’ll post the delayed gleanings for March and early April.

Featured image: Claude Duval painting by William Powell Frith, via Wikimedia Commons (CC0)

The post Wallowing deeper and deeper in the garbage can (part three) appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten refreshing books to read for National Beer Day [reading list]

Beer is one of the world’s oldest produced alcoholic beverages and since its invention some 13,000 years ago, people across the globe have been brewing, consuming, and even worshiping this amber nectar. Whether you prefer a pale ale, wheat beer, stout, or lager, from the cask or a humble bottle, beer enthusiasts can agree that the topic of beer is as complex as its taste.

In celebration of National Beer Day, discover a refreshing selection of titles that explore the social and historical influence of ale, from ancient brewing to the modern craft beer industry.

Beer: A Global Journey through the Past and Present by John W. Arthur

In Beer, archaeologist John W. Arthur takes readers on an exciting global journey to explore the origins, development, and recipes of ancient beer. This unique book focuses on past and present non-industrial beers, highlighting their significance in peoples’ lives. As this book amply illustrates, beer has shaped our world in remarkable ways for the past 13,000 years.

In Praise of Beer by Charles W. Bamforth

In Praise of Beer is a helpful guide for beer lovers looking to learn more about what they should look for with each sip of beer. In his latest book, Charles Bamforth brings new light to the topic of beer in ways perfect for any beer fan, lover, or connoisseur. In Praise of Beer is a helpful guide for consumers who want to better understand the beer they drink.

Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition

by Mark Lawrence Schrad

Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition

by Mark Lawrence Schrad

This is the history of temperance and prohibition as you’ve never read it before: redefining temperance as a progressive, global, pro-justice movement that affected virtually every significant world leader from the eighteenth through early twentieth centuries. Unlike many traditional “dry” histories, Smashing the Liquor Machine gives voice to minority and subaltern figures who resisted the global liquor industry, and further highlights that the impulses that led to the temperance movement were far more progressive and variegated than American readers have been led to believe.

The Oxford Companion to Beer Edited by Garrett Oliver and Foreword by Tom Colicchio

The first major reference work to investigate the history and vast scope of beer, featuring more than 1,100 A-Z entries written by 166 of the world’s most prominent beer experts. Edited by Garrett Oliver, the James Beard Winner for Outstanding Wine, Beer, or Spirits Professional, this is an indispensable volume for everyone who loves beer as well as all beverage professionals, including home brewers, restaurateurs, journalists, cooking school instructors, beer importers, distributors, and retailers.

Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World by Johan Swinnen and Devin Briski

Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World by Johan Swinnen and Devin Briski

From prompting a transition from hunter-gatherer, to an agrarian lifestyle in ancient Mesopotamia, to bankrolling Britain’s imperialist conquests, strategic taxation and the regulation of beer has played a pivotal role throughout history. Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World tells these stories, and many others, whilst also exploring the key innovations that propelled the industrialization and consolidation of the beer market.

The Economics of Beer Edited by Johan F.M. Swinnen

This book provides a comprehensive and unique set of economic research and analysis on the economics of beer and brewing, exploring the economic history of beer, from monasteries in the early Middle Ages to the recent “microbrewery movement.” It considers important questions, such as whether people drink more beer during recessions, the effect of television on local breweries, and what makes a country a “beer drinking” nation.

Voices of Guinness: An Oral History of the Park Royal Brewery

by Tim Strangleman

Voices of Guinness: An Oral History of the Park Royal Brewery

by Tim Strangleman

In this book, Tim Strangleman tells the story of the Guinness brewery at Park Royal, showing how the history of one of the world’s most famous breweries tells us a much wider story about changing attitudes and understandings about work and the organization in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Drawing on extensive oral history interviews with staff and management as well as a wealth of archival and photographic sources, the book shows how progressive ideas of workplace citizenship came into conflict with the pressure to adapt to new expectations about work and its organization.

Becoming the World’s Biggest Brewer: Artois, Piedboeuf, and Interbrew (1880-2000) by Kenneth Bertrams, Julien Del Marmol, Sander Geerts, and Eline Poelmans

Throughout their histories Artois, Piedboeuf, and their successor companies have kept a controlling family ownership. This book provides a unique insight into the complex history of these three family breweries and their path to becoming a prominent global company, and the growth and consolidation of the beer market through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

New Developments in the Brewing Industry: The Role of Institutions and Ownership

Edited by Erik Strøjer Madsen, Jens Gammelgaard, and Bersant Hobdari

New Developments in the Brewing Industry: The Role of Institutions and Ownership

Edited by Erik Strøjer Madsen, Jens Gammelgaard, and Bersant Hobdari

Institutions and ownership play a central role in the transformation and development of the beer market and brewing industry. This book explores the implications of this dynamic for the breweries, discussing how changes in institutions have contributed to the restructuring of the industry and the ways in which breweries have responded, including a craft beer revolution with a surge in demand of special flowered hops, a globalization strategy from the macro breweries, outsourcing by contract brewing, and knowledge exchange for small-sized breweries.

The Rise of Yeast: How the Sugar Fungus Shaped Civilization by Nicholas P. Money

Yeast is responsible for fermenting our alcohol and providing us with bread—the very staples of life. In The Rise of Yeast, Nicholas P. Money argues that we cannot ascribe too much importance to yeast, and that its discovery and controlled use profoundly altered human history. A compelling blend of science, history, and sociology The Rise of Yeast explores the rich, strange, and utterly symbiotic relationship between people and yeast, a stunning and immensely readable account that takes us back to the roots of human history.

Featured image by Lance Anderson

The post Ten refreshing books to read for National Beer Day [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 6, 2021

Seven new books on environmental history [reading list]

The reciprocal relationship between humanity and nature may define the future of our life on this planet, but it is also an inescapable force in our history. To discover how the natural world has impacted the course of history, explore these seven new titles on environmental history:

1. Rivers of the Sultan by Faisal H. Husain

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers run through the heart of the Middle East and merge in the area of Mesopotamia known as the “cradle of civilization.” In their long and volatile political history, the sixteenth century ushered in a rare era of stability and integration. A series of military campaigns between the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf brought the entirety of their flow under the institutional control of the Ottoman Empire, then at the peak of its power and wealth. Placing these world historic bodies of water at its center, Rivers of the Sultan reveals intimate bonds between state and society, metropole and periphery, and nature and culture in the early modern world.

2. West Germany and the Iron Curtain by Astrid M. Eckert

West Germany and the Iron Curtain takes a fresh look at the history of Cold War Germany, asking the question what happens to physical landscapes when political boundaries are drawn? At the heart of this deeply-researched book stands an environmental history of the Iron Curtain that explores transboundary pollution, landscape change, and a planned nuclear industrial site at Gorleben that was meant to bring jobs into the depressed border regions.

3. Unredeemed Land by Erin Stewart Mauldin

3. Unredeemed Land by Erin Stewart Mauldin

How did the American Civil War and the emancipation of four million slaves reconfigure the natural landscape and farming economy in the South? The award-winning author argues that ecological shifts precipitated by the Civil War, shaped the economic and agricultural choices of postwar southerners. Discover the environmental constraints that shaped the rural South’s transition to capitalism during the late nineteenth century.

4. Frozen Empires by Adrian Howkins

How have imperial powers used the environment to support their political claims in the Antarctic Peninsula region? The environment has been at the heart of many disputes over sovereignty, placing the Antarctic Peninsula at a fascinating intersection between diplomatic history and environmental history. Frozen Empires, offers a new perspective on this debate highlighting how political prestige disguised as “science for the good of humanity” continues to influence international climate negotiations.

5. Nature Behind Barbed Wire by Connie Y. Chiang

5. Nature Behind Barbed Wire by Connie Y. Chiang

Using three camps as case studies—Manzanar in California, Topaz in Utah, and Minidoka in Idaho—Nature Behind Barbed Wire explores the intersection of environment and injustice. Chiang illustrates how the very soil, wind, weather, and landscape were important factors in the daily lives of Japanese American internees and helped to shape their perceptions about themselves, their role in American society, and their place in American democracy.

6. Panda Nation by E. Elena Songster

How did the giant panda—a shy creature rarely seen in the wild, not hunted for meat, and all but missing from historical texts—come to serve as the political symbol for China’s international diplomacy and popular nationalism? Integrating local, national, and diplomatic history with animal studies, history of science, and environmental history, Panda Nation shows how the panda transformed into a national treasure.

7. Into Russian Nature by Alan D. Roe

7. Into Russian Nature by Alan D. Roe

In the decades after World War II, the USSR experienced a profound tourism. During these years, Soviet scientists actively took part in environmental protection organizations and promoted parks for the USSR. In the first piece of historical work of its kind written by a scholar who also served as a tour guide in many of the parks studied, Into Russian Nature explores parks from European Russia to Siberia and the Far East, narrating efforts to protect Russia’s vast and unique physical landscapes, despite frustrations from the state.

The post Seven new books on environmental history [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 5, 2021

Anti-Asian violence: the racist use of COVID-19

The recent spate of discrimination, harassment, and violence against Asian Americans has erupted amidst a campaign of fearmongering and disinformation that blames Asian people for the COVID-19 crisis. Rather than being a new phenomenon, the portrayal of Asian Americans as vectors of disease harkens back to a long, sordid, and violent history of anti-Asian racism and nativism.

The nineteenth-century anti-Chinese movement that culminated in the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act focused on the many ills supposedly borne by Chinese immigrants, including prostitution, drugs, labor competition, and—most apropos to the present moment—disease. As historians including Erika Lee, Natalia Molina, and John McKiernan-Gonzalez have shown, people of color and immigrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries frequently faced what Alan Kraut has called “medicalized nativism,” or stigmatization based on a perceived association with disease. Quarantines, border enforcement, and segregation motivated by public health concerns have functioned as racial markers delineating the line between putatively desirable, healthy citizens and those who are marked as undesirable, diseased aliens and outsiders. In the specific case of Chinese immigrants, historian Nayan Shah has demonstrated how nineteenth-century health officials in San Francisco unequivocally condemned Chinese people as an inferior, contaminated race and scapegoated them as an entire people for the spread of contagious diseases.

From the outset of the pandemic, President Donald Trump repeatedly referred to COVID-19 as the “China Flu” and “Kung Flu”—both terms that cemented the association of the virus with Asian bodies and thus racialized a pathogen that respects no national borders. Fox News amplified this xenophobic portrayal of the virus as a threat to be blamed on Asian people. Fueled by this context, the skyrocketing number of incidents of anti-Asian bias have included verbal and online harassment, discrimination and denial of service, vandalism, physical assault, and even murder. The group Stop AAPI Hate collected reports of nearly 3,800 anti-Asian bias related incidents in just under a year beginning in March 2020. In contrast, although the numbers are not strictly comparable, the FBI reported 158 incidents of anti-Asian hate crimes in 2019. Many of the pandemic-era perpetrators attacked their victims both by using racial slurs and accusing them of being the cause of the contagion. The epidemic of violence against Asian Americans has spread across the nation. In Oakland, California, an elderly man was assaulted in Chinatown and later died, one of the victims of eighteen crimes targeting Asian Americans in the area during a two-week period in February 2021. The historic Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo suffered vandalism and arson, and although police declined to label the incident a hate crime pending investigation, the symbolism of striking at one of the city’s most historic and visible symbols of Asian American culture could hardly be more pointed. In New York City, racially motivated crimes against Asian Americans spiked nearly tenfold to 29 in 2020 (from three the previous year), with the great majority being attributed by the NYPD to “coronavirus motivation.”

On 17 March 2021, early reports indicated eight women were murdered in Atlanta-area massage parlors—six of whom were Asian American, leaving open the question of racial bias. Cherokee County Sheriff Captain Jay Baker, who characterized the shooter as having had “a bad day,” previously hawked T-shirts with a logo reading, “COVID 19 Imported Virus from Chy-Na” in homage to Donald Trump’s tortured pronunciation. If the investigation remains in the hands of law enforcement officers who, like Baker, are so callous and proud to proclaim their racism, it would be far from shocking to end up with a verdict that the shooter acted out of sexual frustration rather than racism. Regardless of whether the shooter committed a hate crime based on the race of his victims, it should be crystal clear that he committed a hate crime based on horrific misogyny. The Atlanta homicides recall another mass shooting in which Asian Americans suffered great tragedy yet were racially erased. The 1989 Stockton schoolyard shooting, in which Patrick Purdy murdered five Cambodian and Vietnamese children aged six to nine, sparked national outrage against the availability of assault rifles and inspired the passage of a federal assault weapons ban. Less attention was paid to the fact that Purdy was a white supremacist who railed against Asians stealing American jobs and no national hate crime legislation ensued from the mass killing of Asian American children.

Times of crisis produce resistance. Asian American and Pacific Islander people have rallied to document and protest discrimination, harassment, and violence, and protect vulnerable members of our communities. As I have argued elsewhere, the very identity of “Asian American” as encompassing a multitude of people with varying ethnicities, nationalities, cultures, and languages emerged through 1960s activism against racism. We cannot understand what it means to be Asian American except through comprehending how white supremacy oppresses people of Asian ancestry as part of a complex of power that exploits, delegitimates, excludes, and violates Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people in both parallel and divergent ways. The President of the Association for Asian American Studies, Jennifer Ho, briefly yet eloquently lays out the case that the fight to eliminate anti-Asian racism can only succeed by creating a just and equitable society for all BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) members of society. That such activism remains as necessary in the twenty-first century as it was in the nineteenth suggests the deep entrenchment of racism in US institutions and society. But the fact that the struggles of today are so frequently waged by building coalitions and solidarity among BIPOC people should give us hope for the future.

Feature image by Jason Leung

The post Anti-Asian violence: the racist use of COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

Margaret Mead by the numbers

The life of anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) spanned decades, continents, and academic conversations. Fellow anthropologist Clifford Geertz compared the task of summarizing her to “trying to inscribe the Bible—or perhaps the Odyssey—on the head of a pin. She escapes most categories and mocks the rest.” One way to sketch the outlines of this big picture is to highlight a few numbers:

11At the age of 11, Margaret Mead, against the wishes of her non-religious parents, chose to be baptized into the Episcopal Church. She called it “one of the happiest days of my life.”

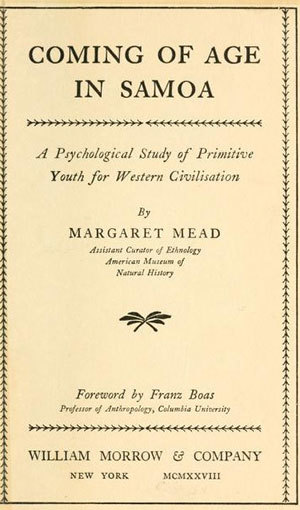

23 Title page of “Coming of Age in Samoa” (via Wikimedia Commons)

Title page of “Coming of Age in Samoa” (via Wikimedia Commons)Aged 23, Mead set out, alone, for Samoa, where she undertook her first field work. The book she published based on her study of adolescent girls, Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), sold millions of copies and made her an immediate, and controversial, star in the nascent field of anthropology.

55Fifty-five years after the publication of Coming of Age, another anthropologist, Derek Freeman, published a book purporting to expose Mead’s work as a myth. Freeman had borne a grudge against Mead for decades but waited until after her death to challenge her. His alleged debunking was subsequently debunked itself, but not before conservative culture warriors seized on the narrative that Mead was a fraud, therefore the sexual revolution that she helped set in motion should never have happened.

At least sixMead had at least six significant romantic relationships over the course of her life. This includes her three marriages (to Luther Cressman, Reo Fortune, and Gregory Bateson); two long-term, same-sex partnerships (with Ruth Benedict and Rhoda Metraux); and one significant affair (with Edward Sapir). All of these partners were fellow anthropologists, except for her first husband, Cressman, an Episcopal priest who left the priesthood for a career in sociology.

OneOne child born to Mead, Mary Catherine Bateson. In accordance with her father’s wishes (Gregory cabled from England “Do Not Christen”), Cathy was not baptized as an infant but was allowed, as her mother had been, to choose her own religion. She elected to join the Episcopal Church and become a social scientist. Mead and her daughter collaborated on liturgical renewal projects, including revisions to the rite of baptism for the 1979 US Book of Common Prayer.

Cathy was also the first “Spock baby.” Mead chose then-unknown Dr Benjamin Spock as Cathy’s pediatrician because he supported Mead’s desire to have a natural childbirth and feed her baby on demand. Spock’s landmark Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (1946) drew on observations of Mead’s parenting style, which in turn drew on her fieldwork in the South Pacific, as well as her ethical commitment to free individuals from suffocating cultural norms.

16 Margaret Mead in 1948 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Margaret Mead in 1948 (via Wikimedia Commons)There are 16 theological essays in the book Twentieth Century Faith: Hope and Survival (1972), Mead’s volume in the Religious Perspectives series, edited by Ruth Nanda Anshen. Although volumes in the series written by other authors, including Karl Barth and Paul Tillich, became well-known classics, Mead’s book is almost entirely unknown. Her essays addressed such topics as Christian uses of technology, urban development, birth control, aging, and the right to die.

108Mead, working with Rhoda Metraux, published 108 columns in Redbook magazine between 1962 and 1978. Most of the columns followed a Q&A format, and topics ranged from abortion to UFOs. As anthropologist Paul Shankman noted in the journal Current Anthropology, “No other anthropologist has had this kind of public forum or done so much with it.”

1,397A total of 1,397 print publications listed in Margaret Mead: The Complete Bibliography, 1925-1975, edited by Joan Gordan. The bibliography is not, in fact, complete, as Mead kept writing until her death in 1978. The bibliography also lists 30 audio recordings (including A Rap on Race, Mead’s 1972 conversation with James Baldwin) and 13 video recordings (including the landmark 1952 documentary “Trance and Dance in Bali.”).

More than 530,000There are more than 530,000 items in the Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, the largest collection in the Library of Congress. The finding aid alone runs to nearly 400 single-spaced pages.

SevenSeven words on her tombstone, which reads, “To cherish the life of the world.” This was one of her signature phrases when she attempted to communicate the purpose of human existence on an interconnected planet. As she wrote in a 1960 essay that used the phrase in its title, “Only if we are able to love—in the sense of cherish and protect, although not agree with—those who are our enemies, while they are our enemies, can we hope to protect the lives of men and the life of the world.” A renowned expert on babies and parenting, as well as a committed, liberal Christian, she could conceive no higher ambition than to make the world safe for other people’s children.

Featured image via Wikimedia

The post Margaret Mead by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2021

The ABCs of modal verbs

Modals are a special group of helping verbs: can and could, will and would, shall and should, may and might, and must. They are a tricky lot, bringing a range of nuances to sentences.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of modals is the contrast between their epistemic and deontic uses. Epistemic uses of modals relate to the speakers’ beliefs and opinions about an action as being possible or necessary. Deontic uses relate to canons or principles and express what ought to be or is permitted, logically or ethically.

A third use is known as dynamic and refers to ability, as in “Marketa can speak fluent Czech.” Together dynamic and deontic modals characterize real-world obligations, possibilities, and abilities as opposed to ones based on a speaker’s beliefs.

Let’s look at some examples.

Must shows its epistemic sense when a speaker says something like “it must be raining” after seeing evidence of rain, like wet people or dripping umbrellas. Might and may can also be used epistemically, with weaker evidence, like cloudy skies.

Must is used deontically to indicate necessity or obligation: “You must follow the instructions exactly,” while deontic uses of may indicate permission as in “You may borrow my book.”

Can is most often used dynamically to indicate ability, but it is also used deontically to give or ask for permission or to make a command (“You can go now.”). Can can even be used epistemically as in “The bridge can be icy” where it indicated a belief based on experience or knowledge.

Could functions much like can:

She could speak fluent Czech. (past ability or belief about a current possibility)

You could go now. (giving permission or acknowledging an opportunity)

The bridge could be icy. (belief based on experience or knowledge)

Will and shall are somewhat marginal modal verbs, used primarily for future actions and states, but even they show epistemic and deontic uses. The first sentence below reports a belief while the second sentence asserts an obligation.

The pizza will be here soon. (prediction based on belief)

Owners shall maintain the premises. (obligation based on law or contract)

Should behaves similarly, expressing both beliefs and obligations:

The pizza should be here soon. (prediction based on belief)

You should wash your hands and avoid touching your face. (obligation based on good practice)

Modal would is unlikely to be used deontically. Instead, would often expresses past habitual actions or a conditional future, viewed as a situation of high probability:

She would always send postcards. (habitual or usual action)

I would visit, but I’m afraid to fly. (belief)

That ringing would be the doorbell. (belief)

The distinction between dynamic, epistemic, and deontic is one of the most puzzling pieces of the verb system. For me, the easiest way keep things straight is with the mnemonic ABC: for ability, belief, and canon.

So when you encounter a modal, ask how it is being used. Is it A, B, or C?

The post The ABCs of modal verbs appeared first on OUPblog.

April 3, 2021

Extreme collision of stellar winds at the heart of Apep, the cosmic serpent

The stellar system known as Apep was recently discovered due to its spectacular and elegant spiral dust structure. This pinwheel pattern originates from two Wolf-Rayet stars located at its heart. Wolf-Rayet stars represent the very last stages in the life of the most massive stars, representing the phase of stellar life immediately before they collapse to produce a supernova explosion. In this case, Apep is strange as it is the by far brightest of such colliding-wind systems, especially at radio wavelengths.

To understand the origin of this surprising brightness, and unveil what was happening at the core of the spiral of dust, astronomers conducted radio observations of Apep with the Australian Long Baseline Array (LBA). This array combines data from ten radio telescopes spread around Australia and New Zealand, reaching a resolution that is sharp enough to identify a truck on the surface of the Moon when looking from the Earth.

By pointing all these telescopes to Apep, astronomers discovered the origin of all this radio emission: the light arises from an extreme shock produced by the collision of the two stellar winds. “The two Wolf-Rayet stars in Apep total 20 times the mass of the Sun, and exhibit winds of up to millions of kilometers per hour. When these two winds collide they produce a very strong and extreme shock, never observed in our Galaxy before. This shock is observed as a banana-shaped structure that emits brightly at radio waves,” says Dr Benito Marcote from the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC, The Netherlands, who led the study.

The imaging of this region where the two winds collide allowed the astronomers to test the behavior of the stellar winds of these dying Wolf-Rayet stars. Given that the stars only spend a limited time in the Wolf-Rayet phase before their death in a supernova explosion, astronomers have confirmed that these systems must be very rare in our Galaxy. “Apep is the first system of its kind and we are now starting to understand how these stars may behave, the dynamics of their strong stellar winds, and how the enormous amounts of dust are produced in the wake of the wind collision,” says Dr Joe Callingham, of Leiden University and ASTRON, The Netherlands, who is the original discoverer of Apep and a co-author of the study. This dust, which is expelled out the system following the orbital motion of the two stars, is the responsible for the beautiful pinwheel spiral structure.

The two Wolf-Rayet stars in Apep are slowly dying. If the environment around the system is already significantly more extreme than any other known system involving two massive stars, astronomers expect this system to end its life in an extreme explosion. Extreme enough to make Apep the most likely system to produce a gamma-ray burst at its end—a very energetic flash of gamma-rays that to date has only been observed at cosmological distances, never in our Galaxy.

Featured image: Real images of the dust spiral seen in Apep in infrared and, right at its center, the region where the two stellar winds collide and emitting in radio (seen as the blue structure in the inset, where the two stars represent their real positions). Credit: B. Marcote & ESO/Callingham.

The post Extreme collision of stellar winds at the heart of Apep, the cosmic serpent appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers