Oxford University Press's Blog, page 122

January 4, 2021

Women & Literature: Maya Angelou

Angelou’s creative talent and genius cut across many arenas. One of the most celebrated authors in the United States, Angelou wrote with an honesty and grace that captured the specificity of growing up a young black girl in the rural South.

Born Marguerite Johnson in St. Louis, Missouri, to Bailey, a doorman and naval dietician, and Vivian, a registered nurse, professional gambler, and rooming house and bar owner, Angelou spent her early years in Long Beach, California. When she was three, her parents divorced, and she and her four-year-old brother, Bailey Jr., were sent to Stamps, Arkansas, to live with their maternal grandmother, Annie Henderson. In I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou recalls in vivid detail this lonely and disconcerting journey to Stamps.

Under the watchful and loving gaze of her grandmother, Angelou lived a life defined by staunch Christian values and her grandmother’s unwavering determination, endurance, and resiliency. Owner of the only general store in town, Annie Henderson was a respected and successful businesswoman. During the Great Depression, she provided financial support for several black and white members of the community.

In 1936 Angelou and Bailey were sent to St. Louis to live with their mother. Urban city life proved to be a revelatory experience for Angelou. She needed to acclimate herself not only to the bustling metropolis of St. Louis, but also to her maternal family, most importantly her own mother. Like Annie Henderson, Vivian Baxter was a dominant figure in Angelou’s life. In Angelou’s eyes, her mother—in addition to being beautiful, smart, and funny—had a no-nonsense attitude about life and living. As Angelou writes in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, “To describe my mother would be to write about a hurricane in its perfect power. Or the climbing, falling colors of a rainbow…. My mother’s beauty literally assailed me.”

Yet Angelou’s time in St. Louis was marked by the most traumatic experience of her life. When she was eight years old, her mother’s boyfriend, Mr Freeman, raped her. In response to this experience, Angelou refused to speak for several years. In the hopes that change and familiarity would be good for Angelou, she and her brother were sent back to Stamps. With the love and encouragement of her family, but in particular because of the bond she forged with Henderson’s friend, Mrs Flowers, Angelou eventually reclaimed her voice. Mrs Flowers encouraged Angelou to discover the power of the written word coupled with the spoken voice to effect change.

In 1940, upon Angelou’s graduation from the Lafayette Training School, where she was at the top of her class, her mother again sent for her and her brother. The children moved to San Francisco. Once again, Angelou advanced in school, and she won a scholarship to attend evening classes at the California Labor School. Studying drama and dance, Angelou began to participate in the art forms that she would soon use to launch her first professional career.

First, however, her father encouraged her to spend the summer in southern California with him and his new fiancée, Dolores Stockland. Her stay in their home ended abruptly after she and Stockland got into a violent altercation, which resulted in Angelou’s running away to live in a junkyard with homeless children for several weeks. The lessons learned during her time with these children would serve as a guiding principle in how she lived her life in later years. As Angelou states in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, “Odd that the homeless children, the silt of war frenzy, could initiate me into the brotherhood of man…. The lack of criticism evidenced by our ad hoc community influenced me, and set a tone of tolerance for my life.”

The year 1944 began Angelou’s more pronounced efforts to lead an independent life. After launching what seemed to be a one-woman campaign to end the discriminatory hiring practices of the trolley cars in San Francisco, Angelou became the first black streetcar conductor in the city. At the age of sixteen, Angelou became pregnant and gave birth to her son, Clyde Bailey Johnson, nicknamed Guy. In 1945 Angelou graduated from Mission High School in San Francisco. For the next several years, Angelou worked as a cook, a cocktail waitress, a dancer, a dishwasher, a barmaid, a madam, and a prostitute. After a brief trip back to Stamps, Angelou returned to live with her mother in California. In 1952 she married Tosh Angelos, an ex-sailor of Greek origin. According to Mary Jane Lupton in Maya Angelou a Critical Companion, “Maya…was married and divorced in one short, unhappy interval.”

During this time, Angelou’s dancing career took an upward turn, and she began to use the stage name of Maya Angelou. Her performances attracted the attention of producers of the touring company of Porgy and Bess, the first all-black opera, written by George Gershwin. From 1954 to 1955, Angelou appeared in a European tour of the opera, which was sponsored by the United States Department of State. Her travels were cut short, however, when she received word that her son had contracted an incurable skin disease. Angelou returned to the States.

In 1959 Angelou and Guy moved to Brooklyn, and she rediscovered her passion for writing. As a member of the Harlem Writer’s Guild, she received constructive criticism from other writers that would prove to be invaluable to her later work. The nation was in a time of critical change. African Americans were demanding an end to segregation and other Jim Crow practices. It was a time of bus boycotts, sit-ins, the March on Washington, landmark legislation like the Voting Rights Act of 1957, the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957 and the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960. During this burgeoning of the civil rights movement, Angelou met many influential figures, including Bayard Rustin, Dr Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X, and Vusumi Make, a South African freedom fighter who would soon be her second husband.

Not only was Angelou perfecting her writing, but also her introduction to these individuals sparked in her a willingness and need to participate more actively in the civil rights movement. In 1960 she helped organize and performed in the Cabaret for Freedom, an off-Broadway musical benefit for SCLC. In the same year, she appeared in another off-Broadway play, Jean Genet’s The Blacks, a dramatic indictment of race and theater art. In that year, the play won an Obie Award. Not long after, at the request of Bayard Rustin, Angelou served a brief appointment as northern coordinator for the SCLC. She also became an active member of the Cultural Association for Women of African Heritage (CAWAH).

After Angelou and Make were married, she, Make, and her son moved to Cairo, Egypt. She served as associate editor of the Arab Observer, an English-language news weekly. After her marriage to Make ended, Angelou and Guy moved to Accra, Ghana, where she served as assistant administrator of the School of Music and Drama at the University of Ghana, Institute of African Studies, in Legon-Accra. She also worked as a features editor for the African Review and as a journalist at the Ghanaian Times.

Angelou returned to the United States in the mid-1960s. Her career as a writer began to flourish. She wrote a two-act drama, The Clawing Within, and a two-act musical, Adjoa Amissah. In 1968 she wrote and narrated Black, Blues, Black, a ten-part series for National Educational Television highlighting the role of African culture in America. Having been encouraged by her friend the author James Baldwin to write an autobiography, Angelou first gained notice in 1970 as the author of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. She emerged during a time when writing by black women proliferated. Among her peers were Toni Cade Bambara, Paule Marshall, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker.

Angelou’s autobiography received critical acclaim. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was nominated for a National Book Award in 1970 and remained on the New York Times best-seller list for approximately two years. The second volume of her autobiography, Gather Together in My Name, was published in 1974. A third volume, Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas, was published in 1976. Angelou was experimenting with the autobiographical form, but also with poetry. Published in 1971, Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water ‘Fore I Diiie, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. In 1975 and 1978, Angelou wrote two collections of poetry, Oh Pray My Wings Are Gonna Fit Me Well and And Still I Rise. The Heart of a Woman, volume four of Angelou’s autobiography, was published in 1981. In 1986, Angelou published volume five of her autobiographical series, All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes. In 2002, a sixth volume, A Song Flung Up to Heaven, was published.

Angelou’s poetic output seemed boundless. In 1983 she published Shaker, Why Don’t You Sing and in 1990 I Shall Not Be Moved. My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, and Me and The Complete Poems of Maya Angelou appeared along with Phenomenal Woman: Four Poems Celebrating Women in 1994. At the request of President-elect Bill Clinton, Angelou wrote and delivered the poem “On the Pulse of Morning” at his inauguration in 1993. Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now, a collection of essays was published in 1993, and in 1997 Even the Stars Look Lonesome, another book of essays. Later forays were in children’s literature. Angelou wrote several such books and contributed to others. They include Mrs Flowers: A Moment of Friendship (1986), Life Doesn’t Frighten Me (1993), Soul Looks Back in Wonder (1993), My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, and Me (1994), and Kofi and His Magic (1996). Critics laud Angelou’s autobiographical writings. None of her works has received more critical attention, however, than her first autobiographical endeavor.

Beginning in the 1970s she participated in numerous theater and film productions. In 1972 she became the first black woman to have an original screenplay produced, Georgia, Georgia. In 1973 she appeared in the Broadway show, Look Away, and earned a Tony nomination. She was honored with an Emmy nomination in 1977 for her performance in Alex Haley’s miniseries Roots. In 1979 she helped adapt her seminal autobiography for a television movie. She wrote the poetry for and starred in the motion picture Poetic Justice in 1993. In 1995 she starred in How to Make an American Quilt. In 1998 she directed and starred in Down in the Delta.

Throughout her writing and theatrical career, Angelou has taught at various colleges and universities. She has held appointments at the University of California, Los Angeles; the University of Kansas, writer-in-residence; distinguished visiting professor at Wake Forest University; Wichita State University; and California State University. Her permanent academic home in the early twenty-first century was Wake Forest University in Winston Salem, North Carolina, where Angelou was the first person to be the Reynolds Professor of American Studies.

Angelou received many accolades and awards, including honorary degrees, lifetime achievement awards, foundation awards, and a Presidential Medal. Maya Angelou’s re-creation of the autobiography enhanced the breadth and scope of the American literary canon.

Editor’s note: this extract from Black Women in America (2nd Ed.) was first published on the OUPblog on 28 September 2006. Maya Angelou has since passed away aged 86 on 28 May 2014.

Feature image by Brian Stansberry

The post Women & Literature: Maya Angelou appeared first on OUPblog.

January 3, 2021

Understanding un-

Recently I had occasion to use the word unsaid, as in what goes unsaid. Looking at that phrase later, I began to ponder the related verb unsay, which means something different. What is unsaid is not said, but to unsay something means to retract it. The same not-quite-parallelism holds for unseen and unsee and unheard and unhear. Sometimes un- means not and sometimes it means to reverse.

The pattern, as linguists will tell you, has to do with using a word as a verb versus using it as an adjective. To un– a verb is to reverse the action of something: to undress, untie, unzip, unfold, unpack, untuck, untwist, unroll, unveil, unwrap, undo, and many more. Adding un– to a verb was a favorite trick of Shakespeare’s yielding such words as to unsex, to uncurse, and to unshout.

To un- an adjective is to negate the quality described by the adjective: unabridged, unacceptable, unanswered, unbalanced, uncommon, unlucky, untidy, untrue, unwritten, and so on. Some of these adjectives are just un- plus a straight-up adjective—acceptable, common, lucky, tidy, true. Others are made from the past participle of the related verb: abridged, answered, balanced, written. In each case, the meaning is “not” rather than “reverse.” An unabridged dictionary is not one in which words have been put back in, but one in which they are not left out. An unanswered question is not one receiving a bogus answer, but one getting no answer.

The story of un- gets tricky though because sometimes past participles serve as verbs, which allows ambiguity: The box was unpacked. The baby was undressed. The jacket was unzipped. The gift was unwrapped.

Each of these has an adjectival sense, in which the box was not packed, the baby was not dressed, the jacket was not zipped, the gift not wrapped. But each also has a reversed sense in which some unnamed person is unpacking the box, undressing the baby, unzipping the jacket, or unwrapping the gift. Of course, sometimes only one meaning is possible, as in (the classic example) Antarctica is uninhabited, which cannot mean that someone is uninhabiting Antarctica.

The Oxford English Dictionary 2018 update gives nearly 300 un- plus adjective combination, including unadult, unblasé, unsorry, and un-with-it. Nouns with un- are usually derived from adjectives, so they carry the sense of not rather than reversal: uneasiness, untruth, and so on.

Curiously, in a handful of words un– seems unnecessary but shows up anyway. The most widely used is unloose/unloosen, which the OED attests as early as the fourteenth century. Perhaps analogy with other un-verbs (untie, unfasten, unleash) is a factor in the unnoticed redundancy. Unthaw, meaning to thaw out, is attested as early as 1700, and today may even be heard in your own kitchen.

Unravelling unravel is trickier. Ravel it turns out is a contranym: a word which can mean either entangle or disentangle. So the un- of unravel does some work here, disentangling the senses of the root.

And finally, some instances of un- are mere historical vestiges. Uncouth and unkempt began as the prefixed words uncūth meaning “unfamiliar” and unkemd meaning “uncombed.” As the meanings shifted, the roots cūth and kemd became obscured and today we longer view uncouth and unkempt as prefixed forms at all.

So the next time you use an un- word, pause for a second and mentally take the word apart. You may find the experience uncanny.

Featured image by Adam Valstar

The post Understanding un- appeared first on OUPblog.

January 1, 2021

Women & Literature: Zora Neale Hurston

‘Zora Neale Hurston’ by Bev Sykes.

‘Zora Neale Hurston’ by Bev Sykes.The oral tradition of southern black folklore was an art and a skill handed down from Africa, preserved through slavery, and still thriving in the early years of the twentieth century, when Zora Neale Hurston came of age. The tradition was preserved through generations of rural southern culture and began to decline when the black workers left the agricultural South for the cities of the North. Zora Neale Hurston was singularly placed to record this material as folklore and to transform it to art through fiction. Zora Hurston’s place and date of birth are obscured by the selective secrecy and mythology that veiled her personal life. Hurston wanted her contemporaries to believe that she was born 7 January 1901 in Eatonville, Florida. Birth records revealed years later, however, that she was born in 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama.

Early Life in EatonvilleThe circumstances of her early life and family and the influence of growing up in Eatonville, Florida, are of primary importance in understanding Zora Neale Hurston’s life and works. Hurston’s father, John Hurston, had been conceived in slavery in Alabama, the son of the master and a slave. He moved with his strong-minded, intelligent wife, Lucie Potts, and seven children to the remarkable town of Eatonville, a tiny township in central Florida—organized, incorporated, and governed by black people—where he was a successful carpenter and Baptist preacher.

Zora Hurston’s youth as the intelligent daughter of respected Eatonville citizens was conducive to her self-esteem and her feeling of safety, free from the sense of second-class citizenship common in southern black life. Her circumstances also led to an inborn appreciation for the richness of southern black culture. Eatonville was a melting pot of black Americans from all over the South. The people there were a bottomless source of stories. The young Zora’s eyes and ears were open to the rich life of the community around her. She later wrote, “From the earliest rocking of my cradle, I had known about the capers Brer Rabbit is apt to cut and what the Squinch Owl says from the house top.” The porch of Joe Clarke’s general store was the scene of “lying contests,” stories, songs, jokes, folklore. With this porch Hurston created a powerful image, an icon, throughout her work. It appears in her novels, her drama, and her folklore as well as her autobiography. This safe and comfortable childhood ended abruptly with the death of her mother. Hurston wrote the moving deathbed scene in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road (1942), and her autobiographical novel Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934). Hurston’s father remarried in haste, but his new wife did not want his children and the siblings dispersed to relatives and boarding schools.

The young Hurston made her own way as a black woman in the world of the American South, working as a maid or nanny when she could. These times were the ten lost years that she never mentioned, that she erased from her story. No doubt these were the years when she learned the traits of survival and self-sufficiency. She emerged as a ladies’ maid and helper with a touring Gilbert and Sullivan troupe. Hurston was able to return to school in Baltimore in 1917, attending Morgan Academy and graduating in 1918. An eager student, she went on to Howard University in Washington, D.C., always working her way through school with odd jobs. Hurston blossomed at Howard and published her first short story in the college literary magazine, Stylus, in 1921.

In 1924 Hurston published her short story Drenched in Light in Opportunity magazine. Drenched in Light is thinly disguised autobiography, a story about a joyful child in Eatonville. The message is that the young protagonist is poor and black but “drenched in the light” of family, community, and culture. The story is a statement of affirmation, written by a woman who has pondered her identity and origins.

The Harlem RenaissanceThe following year Hurston submitted a story, Spunk, and a play, Color Struck, to Opportunity‘s literary contest. Both won prizes. The Opportunity awards dinner, a showcase for young black talent attended by literary New York, was Hurston’s entrée to the Harlem Renaissance. The vibrant, confident young woman with the unusual background and stories was noticed. Annie Nathan Meyer, a founder of Barnard College, obtained a scholarship for Hurston. Fannie Hurst, a popular writer, gave her a job as secretary and companion.

Hurston continued to write and publish short stories and plays, with Eatonville as her subject. Critic and biographer Robert E. Hemenway (1977) characterizes some of the work of this period as hackneyed, all theme with little plot. Yet the Eatonville material was compelling, matchless in its place in history and culture, and Hurston had an eye and ear for her subject along with a conviction of the importance of her message. She had not, however, yet found her genre or her voice. She was still struggling with her craft and her perspective.

The Harlem Renaissance was a period of a fertile flowering of black art, music, and voice in the 1920s and 1930s. Zora Neale Hurston was a presence in the Harlem Renaissance, meeting everyone, being noticed, becoming a full-fledged member of the “niggerati,” as she called the black literary community. In 1926 she organized the short-lived radical journal Fire!! with Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman. Hurston found herself in the role of proletarian in New York City as she found the Harlem Renaissance largely a movement of northern-raised, middle-class black artists who were a generation removed from the source of their material. These were black artists who had absorbed a mainstream conception of high art; who took material with black origins and formalized it—for example turning the spirituals of the southern Baptist churches into composed and arranged songs to be performed for white audiences in concert halls. The goal of those presenting the “New Negro” and his art was to prove that black art and culture were equal to white art.

Hurston, however, was the genuine article, the folk, and her mission was to present and preserve the folk voice as she knew it from her youth in the South. Further, Hurston had a sense that the folk material that she loved was not a lower form of art but an oral tradition that had enabled the black people to survive with dignity and strength. Her goal was to glorify and preserve a form of black expression that she felt was being diluted by urbanization.

“The Spyglass of Anthropology”At Barnard College, Hurston studied anthropology under Franz Boas, a noted authority in the field. She found that anthropology offered a scientific framework for her folklore. She had not found a voice for the Eatonville material in the short story genre; anthropology gave her the form she was searching for. In the introduction to Mules and Men (1935), Hurston wrote that she had to have “the spyglass of anthropology” to begin to codify her experience in Eatonville. Anthropology gave her the opportunity to look at her community culture and folktales with the objectivity of a social scientist; the step back from her personal experience helped to reconcile her to her past.

‘Zora Neale Hurston, Beating the Hountar, or “Mama Drum”’ (1937), US Library of Congress.

‘Zora Neale Hurston, Beating the Hountar, or “Mama Drum”’ (1937), US Library of Congress.Soon Hurston was doing fieldwork for Boas in Harlem. Then, in February 1927 she was given a grant to collect folklore in Florida. Previously, some black folklore had been collected by white researchers, but their findings were often influenced by stereotypes and misconceptions of the black personality and experience. Hurston was unique: a black scholar and social scientist with a deep understanding of the culture she would study.

This first folklore-collecting trip was not very successful. She wrote later that people were suspicious of her Barnard manner and told her only what they wanted her to hear. She returned to Boas and admitted her disappointing results. Wise Boas was not surprised. Perhaps the cocky, confident Zora needed to learn from a failure.

PatronageIn the fall of 1927 Hurston met Mrs Rufus Osgood Mason, a wealthy white woman who was to play a major role in her life. Mrs Mason was patron to several black artists, including Langston Hughes. At the behest of her eccentric whim, her protégées called her “Godmother.” Hurston signed a contract with Mrs. Mason that enabled her to go back to the South on another collecting trip. Mrs Mason gave her a car and $200 a month and in December 1927 Hurston departed again, intending to begin in Mobile, Alabama, travel to Florida, and end up in New Orleans, Louisiana, to gather and record tales, songs, games, customs, and voodoo rituals of rural southern black Americans.

Hurston had learned from her first expedition. She would need the patience and imagination to live as a part of the community, not as an outsider, a northern-educated scientist. In Polk County, Florida, she created the fiction that she was a bootlegger’s girlfriend running from the law. She was welcomed into the lumber and railroad work camps, where she kept her ears open and took notes. Her Florida work ended when she was nearly knifed at a “jook joint” by a woman jealous of Zora’s attention from the men. She went on to New Orleans to collect voodoo practices and rituals, becoming an initiate under several practitioners.

That year spent collecting in the South under Mrs Mason’s patronage was pivotal for Hurston. The financial support was liberating. Her collecting was so fertile that she drew on the material from this trip for the rest of her life. Hurston matured. She began to see the stories and customs of her childhood and her culture as part of a pattern of black experience and survival and to fit her own life as a survivor into the pattern. On the surface she was a scientist working on a folklore-collecting expedition, but underneath she was becoming a novelist who could connect the collective stories with individual experience in an expression of art.

Hurston spent much of 1929 living on Mrs Mason’s money and organizing her field notes. Living in South Florida, Hurston met West Africans and became interested in their customs, folklore, and dancing. She began to make links between African-American and African-Caribbean folklore. She spent some time in Nassau in the Bahamas in 1929 and 1930, living again within the community, learning and collecting songs, dances, and customs.

Hurston was beginning to chafe at the restrictions of her contract with Mrs Mason. She had the Florida and New Orleans material organized and ready for publication. She wanted to work on some new, independent projects, while Mrs. Mason contended that the contract was not fulfilled until the folklore material was published. Unfortunately, Mrs Mason held the title to the material and Hurston was prohibited by the contract from publishing anything without Mrs Mason’s approval, so if Hurston wanted to see her book in print, she had to submit to Mrs Mason’s terms. Hurston spent nearly two years organizing her vast notes and material. She published Hoodoo in America in the Journal of American Folklore in 1931 and looked for a book publisher for a scholarly presentation of her findings.

Both Hurston and Langston Hughes were living in New Jersey in a sort of artists’ colony where Mrs Mason put up her protégées. Hurston and Hughes began to collaborate on a play, Mule Bone, a series of skits and songs based largely on the folklore that Hurston had collected in Eatonville. The first act takes place on the porch of Joe Clarke’s store. Hurston envisioned a form of theater that would present authentic material in an aural context, in an exuberant and accessible manner.

The Mule Bone project and her relationship with Langston Hughes fell apart in a bitter misunderstanding that was worsened by tensions relating to Mrs Mason’s patronage. Hughes left the Mason payroll, feeling increasingly guilty about enjoying caviar in her home while writing about the blues of his people. Hurston needed Mrs. Mason’s patronage for a while longer, until she found a publisher for her collection. Hughes and Hurston became estranged; then Hughes discovered that the play was in negotiation with a theater company, to be produced with Hurston as sole author. He filed suit. It turned out that their mutual friend Carl Van Vechten had sent a draft of the play to the theater without Hurston’s knowledge, but the damage was done and the play was never produced.

The Great DayHurston’s relationship with Mrs Mason was finally severed in March 1931 while Hurston was still searching for a publisher for her folklore collection. She found herself with a need to earn a living. She also found herself with a growing conviction that her stories and songs could be better presented in some living form than in a scientific journal. She envisioned a revue that would be artistically true to the folk tradition, including comedy, songs, and dances.

‘Zora Neale Hurston’, by Carl Van Vechten (1938), U.S. Library of Congress.

‘Zora Neale Hurston’, by Carl Van Vechten (1938), U.S. Library of Congress.Hurston wrote and staged the theatrical revue The Great Day (1932), using her collected folk material and including authentic Jamaican dancers and drummers. The revue was structured around a day in a railroad work camp, ending with an evening at the “jook.” Produced on a shoestring with Hurston ingenuity, the performance in January 1932 was an artistic success. She was to use the same material for several years, repeating the New York City performance. Hurston also created a new version at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, and took that show on the road. She still had no publisher for her folklore collection and so earned her living by this theatrical expression of her material and experience.

Hurston tried her hand at various academic jobs in the South, working on her conception of authentic theater in college drama departments. Hurston the scholar, with her Barnard credentials, and Hurston the exuberant voice of Eatonville, with her theatrical successes, sought to present an authentic and traditional form of expression. Her goal was to bring legitimate folklore to theater and concert audiences.

Segregated Florida in the Great Depression was not a fertile ground for black theater production, nor was Hurston’s vocation in academe. She was later awarded a fellowship to work on a Ph.D. in anthropology at Columbia starting in 1935, but by that time her focus was on a new form of expression for her experience.

Jonah’s Gourd VineHurston turned to fiction in hopes of producing income and finding a medium for her Eatonville voice. She published The Gilded Six-Bits in Story magazine in August 1933. This is a mature story, set in Eatonville, and was the catalyst in attracting the publisher that she needed. The Philadelphia publisher J. B. Lippincott noticed the story and asked her for a novel. She rented a cabin in Eatonville and sat down and wrote Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934).

This, Hurston’s first novel, is a blend of autobiography, folklore, and fiction. The book succeeds because the voice of Eatonville pours from her pen. The story is authentic, based on the life of her father, the Baptist preacher born into slavery. John Pearson rises with determination, the help of his strong wife Lucie, and his gift for poetry. But John has a fatal flaw; he is a philanderer. After his wife dies, in a deathbed scene based on the death of Hurston’s mother, John—filled with guilt but bewitched by his lover with the help of a hoodoo man—remarries in haste and eventually is cast out by his congregation.

The use of the collected folklore is central to the novel, which describes customs, food, celebrations, and the telling of “lies” on the porch of the general store and is written in the black vernacular. John’s farewell sermon, a triumph of language and poetry, is quoted directly from a sermon Hurston collected while in Florida.

If sometimes the transitions are flawed, if the reader is brought too abruptly from the folklore material to the fictional plot, Hurston nevertheless has the gift of knowing where to leave autobiography behind and move into the realm of fiction. From the suggestion of hoodoo in John’s hasty remarriage to his failed redemption, Hurston departs from life and finishes the fictional tale. Jonah’s Gourd Vine was written in a fresh and knowledgeable voice, with an ear for dialect and using material and a setting that Hurston was uniquely placed to present.

Language is at the heart of the novel, as it was at the heart of all of Hurston’s subsequent writing. Her authentic and original use of the black idiom, a language rich with proverbs, wordplay, imagery, and metaphor, is a solid achievement. John Pearson is aware of the power of language; his gift for language raises him from laborer to leader. Most important, language, especially black language, is honored in Jonah’s Gourd Vine. John’s poetry rises from a culture that values skill and improvisation in oral art, from the store porch and from the pulpit.

Mules and MenPleased with Jonah’s Gourd Vine, Lippincott agreed to publish Hurston’s folklore collection, which became Mules and Men. Lippincott wanted the anthropology material popularized for the average reader. Hurston devised a form, a story within a story, in which she puts the folklore into context, creating a first-person role for herself as narrator and collector as well as the third-person role of social scientist and observer.

‘Zora Neale Hurston’, U.S. Library of Congress.

‘Zora Neale Hurston’, U.S. Library of Congress.Hurston found a voice when she put herself as a character in her report. She created herself, the semifictitious narrator. Her introduction to Mules and Men is a statement of her method and identity, uniting her own past in Eatonville with the curious researcher. Hurston was criticized by the scholarly community for putting too much of her own personality into a scientific report. She was apprehensive of how her mentor, Franz Boas, would react to the form, but he agreed to write the preface and presented his protégée as a collector who was able to penetrate the true inner life of her subjects.

Hurston was sometimes accused of being less than scrupulous in her writing and collecting. She was as much an interpreter of the folklore she collected as an objective scientist. The line between fact and fiction was not always sharply drawn. Perhaps she embellished. Perhaps some of the tales are stories that she herself contributed to the lying sessions on the porch of the village store. Shortly after Mules and Men was published, Hurston was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to go to Jamaica and Haiti to collect material on religious practices. She spent much of 1936 and 1937 on those islands.

Hurston’s personal life was always complicated; she revealed as little as possible in her writing. She was married at least twice, and possibly another time during the lost ten years in her early life, those years whose existence she denied by changing her birthdate. There is, however, a chapter titled “Love” in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road (1942). One of her marriages was to Herbert Sheen, her sweetheart throughout the Howard and Barnard years. The marriage itself was brief; the conflict between marriage and career may have been the reason for its failure. The turmoil surrounding the marriage may have contributed to the failure of her first collecting expedition in early 1927.

Their Eyes were Watching GodThe trip to the West Indies in 1936 and 1937 occurred at the time of another breakup, this time of an affair between Hurston and a man twenty years younger than herself. This man, she said in Dust Tracks, asked her to marry him and give up her career, “that one thing I could not do.” Thus, it is no coincidence that the book she wrote in exile from this affair was the story of a woman who is determined to find her own identity on her own terms, and a story of a love affair between a vibrant older woman and a younger man.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is Hurston’s masterpiece, an elegant short novel about a young woman’s search for self, for love, for freedom. The novel has the familiar autobiographical elements: a parent born in slavery, Eatonville, the porch of Joe Clarke’s store, a hurricane scene drawn from a storm she experienced in the Bahamas in 1929. It draws heavily on folklore and on black history, culture, and language.

The heroine is Janie Crawford, a young black woman raised by her grandmother, a former slave. When Janie feels the stirrings of sexual awakening, her grandmother quickly marries her off to an older man who can provide land and security. Once Janie realizes that love will not come to this marriage and that her husband will treat her as another piece of property, a mule to be worked, she runs away with Joe Starks. Joe is an ambitious young man on his way to Eatonville to make something of himself. He becomes the mayor and storekeeper of the town. Joe expects his wife to play the role of “mayor’s wife” and to work in the store, but he does not encourage her to join in the storytelling on the store porch or to mingle with the other women in the village. She is an adjunct to Joe’s prestige and is not allowed any personal expression or voice. For both of her husbands, upward mobility focuses on ownership and suppression of Janie’s own self-awareness. Janie sadly watches Joe become more pompous and demeaning, and this marriage, too, becomes loveless.

There is a moment of awakening in each marriage as Janie gradually becomes more self-aware. She walks away from her first husband when she realizes that he wants her to be “de mule uh de world.” Joe Starks represents change and the outside world and Janie is ready to move on. Later, after years with Joe, she understands that she has learned to keep her inner and outer lives separate. “She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them.” This woman’s awakening is a universal feminist theme, black or white.

Joe Starks dies and Janie is liberated from his oppression. Now a wealthy widow, she meets Tea Cake, an easygoing black man years younger than she. He is a free spirit who loves life, gambles without apology, and awakens laughter and stories in Janie. At last Janie blossoms, finally fulfilling the promise of womanhood that was nipped in the bud when her grandmother married her off to a respectable old man. Janie and Tea Cake leave Eatonville, walking away from disapproving public opinion, and live a joyous life picking beans in the Everglades.

The story ends tragically, however. Escaping from a violent hurricane, Tea Cake is bitten by a rabid dog. He succumbs to rabies himself and becomes irrational and violent; ultimately, Janie is forced to shoot him in self-defense. She is acquitted at her trial, and returns to Eatonville to live out her life, happy that she has at last known a true love and joy in life.

The novel is pure Hurston, infused throughout with folklore and autobiographical elements. She spans the history of black people in the South from the end of slavery through the 1930s. She writes with a lyrical ease, transforming folk tales into metaphor, rendering dialect with her impeccable ear. Their Eyes Were Watching God is a feminist novel, resonating with a black voice. A woman’s freedom lies in discovering her own voice and identity apart from her husband; a people’s freedom lies in preserving their own voice and identity apart from the oppressor. With this novel, Hurston achieved a literary expression for her experience.

Tell My HorseTell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (1938), is Hurston’s report of her collecting experience in those islands. The practice of voodoo was a powerful spiritual experience for Hurston. She treats voodoo as a serious religion, originating in Africa and coexisting with Roman Catholicism. Tell My Horse, like so much of Hurston’s work, is written in an original mix of style and genre, travelogue and political commentary mingling with observations on art, dance, practices, and customs that only the now-experienced, mature, and confident Hurston could provide. Typically, she shifts between the first- and third-person voice, using the first person for observation and commentary, the third person to report history and politics. She describes instances of possession, the hierarchy of voodoo gods, and details of ceremonies, information that would only be accessible to an initiate. The book is illustrated with photos, including a remarkable photo (and report) of a zombie in Haiti.

‘Zora Neale Hurston Signature’ (14th January 1942), from the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University,.After the publication of Their Eyes Were Watching God and Tell My Horse, Hurston returned to Florida. Through 1938 and 1939 she worked in the South, collecting, writing, working on drama projects. There was another short-lived marriage, this time to Albert Price III in 1939.

Moses, Man of the MountainMoses, Man of the Mountain (1939) was published at Hurston’s zenith. The novel is complex, a display of virtuosity in character, background, language, themes, and satire, a Hurston blend of Eatonville, Africa, and finding a way into freedom. The basis of the novel lies in the African and voodoo approach to Moses, revered as a man of power who could talk to God face-to-face, and in the identification of American black slaves with the enslaved Jews in the Bible. The novel is set in Egypt and the promised land, but the characters are rural black Americans with the speech and mannerisms of Eatonville. The Jews of the biblical tale are black Americans and Pharaoh and the Egyptians are whites.

The voice of Eatonville, as interpreted by Zora Neale Hurston, is humorous and feisty. This was resented by some black leaders and intellectuals, who were beginning to complain that Hurston was too narrowly focused on Eatonville and that she ignored the many negatives of southern black experience. Moses, Man of the Mountain lacks bitterness. Hurston was expected as a black writer to write a protest novel, exposing the racial injustice of the South. She was determined instead to celebrate black culture in literature.

Dust Tracks on a RoadHaving written five books in five years, Hurston was at a crossroads. Her publisher, J. B. Lippincott, suggested she write an autobiography. She moved to California in the spring of 1941, where she worked on the manuscript of Dust Tracks on a Road and as a story consultant at Paramount Studios.

Dust Tracks on a Road is a book that mirrors the division that emerged in Hurston’s life. The early part of the book, where she describes her background, childhood, and early life is vibrant with stories and scenes and the voice of Eatonville. The reader sees the hopes and dreams of the joyful child whose father, the preacher, showed daily how language could enthrall, whose mother urged her to reach for the stars, and whose ears were tuned to the “lying” on the porch of Joe Clarke’s store in Eatonville. The reader experiences that child’s helplessness and despair at her mother’s deathbed and begins to grasp the tenacity and self-reliance Zora Hurston needed to get an education and reach New York City and professional recognition.

Once Hurston reaches the point where she acknowledges her patron—Mrs. Mason, her “godmother”—she begins to lose the vibrancy of Eatonville’s stories and her own confident voice. Her tone changes, becomes awkward and ingratiating. Dust Tracks on a Road‘s vitality seems to be a casualty of her odd patronage relationship. As she brings society and politics into the picture, her voice falters. Reactions were mixed. Whites liked the book; it harmed her reputation with her black peers, however.

Indeed, by the mid-1940s Hurston seemed to be losing her voice. A novel and a proposal were rejected by Lippincott, though she was publishing magazine articles and continuing to work on the black college circuit. Politically she grew more conservative; her voice shifted from the self-confident first person of idiomatic black speech to the artificial third person of unpopular political viewpoint.

Seraph on the SuwaneeIn 1947 Hurston signed a contract with Charles Scribner’s Sons for a novel about a white southern family. Seraph on the Suwanee (1948) was written in Honduras, on a trip to look for a lost city, financed with the advance money from Scribner’s. She had ambitions for Seraph on the Suwanee. She hoped to challenge literary conventions, to prove that a black woman could write about whites. The novel tells the story of a poor white family in Florida that gradually achieves upward mobility and of a woman who struggles with her identity in marriage. The language of the novel is the southern vernacular. Hurston hoped to show that southern blacks and whites had language and cultural influences in common.

The early reviews of Seraph on the Suwanee were favorable. Just at the time that Hurston and her publisher would have promoted the new book, however, a bombshell fell. Hurston was accused of sexually molesting a ten-year-old boy. The charges were false. Hurston was able to prove that she was in Honduras at the time the incidents were alleged to have occurred; the boy was shown to be disturbed. But the damage had already been done. A national black newspaper, Baltimore’s Afro-American, picked up the story and created a lurid scandal. Hurston was devastated. She considered suicide. She removed herself from the public eye as best she could. Seraph on the Suwanee was to be her last published novel.

Hurston did recover from this blow. She moved back to Florida, bought a houseboat, planted a garden. She continued to write magazine articles for a mainstream audience, worked as a maid, did some substitute teaching in Fort Pierce, Florida. Her articles were increasingly conservative in tone and it was difficult to find publishers for her work. Money was a problem. Her health deteriorated. In 1959 she had a stroke and entered the St. Lucie County Welfare Home. She died there on 28 January 1960 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

The LegacyWhy did Zora Neale Hurston decline from her standing as a vibrant presence in the Harlem Renaissance, a fertile interpreter of black folklore, and a lyrical writer to become a poor woman buried in an unmarked grave? Part of the answer lies in the struggle for money. The need to make ends meet overcame her art and her scholarship in the end. At the mercy of patrons and publishers, it was always a struggle to collect, to keep writing, to make art. The Eatonville voice that Hurston so loved faltered as she looked for a mass magazine audience. An outsider in the white world of publishing, she was criticized by black leaders and intellectuals as well. Then the scandal of the false sexual accusation broke her spirit. She finally became bitter.

Hurston’s strength and gift was pride in the folk heritage embodied in her Eatonville experience. This emphasis on culture did not translate well to politics. She was outspoken; she wanted to affirm her belief in the individual, her belief that a black background need not be tragic. Black opinion accused her of ignoring the dark side of life in the American South, giving a whitewashed picture of southern black life. She grew even more conservative after the scandal. She was always an outsider but she had always been exuberant, excited by her work, believing in it. She lost her voice, she retreated to her garden, she was poor, she became ill, she died quietly.

Zora Neale Hurston’s books were out of print for thirty-five years. Then, in the late 1970s, black writer and scholar Alice Walker wrote an essay, Looking for Zora, and interest in Hurston was revived. In Zora Hurston, black women writers found a rare model, a woman who wrote in the black vernacular, who affirmed black folk culture with pride and exuberance.

Zora Neale Hurston left a record of an oral folk tradition that she was uniquely placed to provide. She had a clear, individual, woman’s voice, even if she was at times inhibited by her white patron, her publishers, and her need for cash. Her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God has become a classic of African-American feminist literature, yet the theme of a woman finding her voice and equality in marriage is universal.

Zora Hurston was at her best when interpreting Eatonville. She was happiest in Florida, and at her worst when struggling for money. She was proud to have “the map of Dixie on her tongue.” The creation of an original black literature based on pride in the language and folk tradition of African Americans was Hurston’s lifelong goal and her major contribution.

Editor’s note: this article from The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature was first published on the OUPblog on 11 September 2006.

The post Women & Literature: Zora Neale Hurston appeared first on OUPblog.

December 31, 2020

What everyone needs to know about 2020

Across the globe, 2020 has proved to be one of the most tumultuous years in recent memory. From COVID-19 to the US Election, gain insight into some of the many events of 2020 with our curated reading list from the What Everyone Needs to Know® series:

US politicsPresidential ElectionsPresidential elections are the crown jewel of American electoral democracy, but there are some very important issues looming. Is the electoral college the most reliable way to measure a presidential election, or should we be looking at other systems? The primary and pre-primary phases are long, expensive, and arduous. There are several ways our system could be made better. Will we ever create a better system?

What is Political Polarization?Commentators use few words to describe the American political scene as frequently as they use the word “polarized.” But unfortunately, the terms polarized and polarization have taken on such a wide variety of meanings among journalists, politicians, and scholars that they often confuse, rather than clarify, the problems that our political system faces.

Yearning to Breathe FreeHow is the word “immigration” defined? The Oxford English Dictionary states that “[immigration] is the action of entering into a country for the purpose of settling in it.” The definition conveys a sense of individual freedom. What are the meanings of “exile” and “refugee”? Are all Latinos Immigrants? What is the overall position of Latinos on Immigration?

Politics: Yesterday, Today, and TomorrowSomewhere between one-tenth and one-third of Americans are libertarians. Many libertarians do not self-identify as libertarian. They call themselves liberals, moderates, or conservatives. Many of them vote Democrat or Republican. Thus, to know what percentage of Americans are libertarian, we can’t just ask people if they are libertarians.

Global protestsHow do Countries Shift from High to Low Corruption?The world’s wealthy democracies all have relatively honest governments. However, that wasn’t true a hundred or two hundred years ago, when they looked like governments in today’s poor countries. How did they do it? How do countries escape a high-corruption equilibrium?

Causes of Changing Inequality in the WorldWhen we move toward an analysis of inequalities in the wider world, we are required to cope with far more complex and uncertain data, and at the same time to seek simpler and more abstract theories. But to come up with a theory that has common application across many countries, we need measurements of inequality across countries and through time that are reasonably comprehensive and reasonably reliable—and this is a major challenge.

Understanding Authoritarian PoliticsPolitics in authoritarian regimes typically centers on the interactions of three actors: the leader, elites, and the masses. What are the major goals of these actors? What is the difference between an authoritarian leader and an authoritarian regime? What is the difference between an authoritarian regime and an authoritarian spell?

Climate changeEnvironmental ProtectionEnvironmental protection is a relatively new idea. Today, environmental protection, however one defines it, has taken root around the world. Why does the environment need protection? How did protecting the environment become a societal concern?

Climate Politics and PoliciesWhat climate change policies are governments around the world using to fight climate change? What is a carbon tax? What are cap-and-trade and carbon trading? This chapter will explain the most commonly used or discussed climate policies around the world. It will also explore some of the issues involving climate politics.

Introduction to marine environment and pollutionThe marine environment covers not only the ocean, but estuaries (e.g., bays), which are coastal areas where the seawater is diluted with freshwater coming from rivers and streams, or sometimes groundwater. Much of the pollution is concentrated in these shallow coastal areas, which are often next to urban centers and other concentrations of humans who are responsible for the pollution.

PandemicsWhat is a Vaccine and How Do Vaccines Work?A vaccine is a substance that is given to a person or animal to protect it from a particular pathogen—a bacterium, virus, or other microorganism that can cause disease. The goal of giving a vaccine is to prompt the body to create antibodies specific to the particular pathogen, which in turn will prevent infection or disease; it mimics infection on a small scale that does not induce actual illness.

Pandemics, Epidemics, and OutbreaksA novel infection—new and previously unconfronted—that spreads globally and results in a high incidence of morbidity (sickness) and mortality (death) has, for the past 300 years or more, been described as a “pandemic.” Who declares a pandemic? Should the pandemic classification system be refined?

Afterword in the Face of the COVID-19 PandemicFear and anxiety are normal in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. We do not want to pathologize this normal fear and anxiety. We hope that people can use their good coping skills to deal with this unprecedented situation. We know we are in the thick of it, but we do not know exactly where we are in it.

As we reach the close of 2020, we look ahead to a hopeful 2021. With the forthcoming events of 2021, stay up-to-date on the most important topics leading the discussion today in politics, health, global affairs, and more with the What Everyone Needs to Know® series.

Featured image by Kelly Sikkema

The post What everyone needs to know about 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 30, 2020

Women & Literature: Lorraine Hansberry

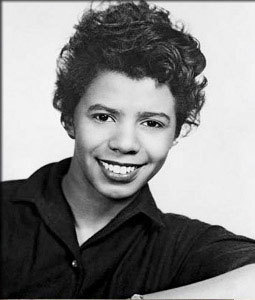

Lorraine Hansberry (image via Wikimedia Commons)

Lorraine Hansberry (image via Wikimedia Commons)Lorraine Hansberry (19 May 1930-12 January 1965) was a celebrated black playwright who was born in Chicago, Illinois, and died in New York City at the age of thirty-four after a scant six years in the professional theater. Her first produced play, A Raisin in the Sun, has become an American classic, enjoying numerous productions since its original presentation in 1959 and many professional revivals during its twenty-fifth anniversary year in 1983–1984. The Broadway revival in 2004 brought the play to a new generation, and earned two Antoinette Perry (Tony) Awards for individual performances. The roots of Hansberry’s artistry and activism lie in the city of Chicago, her early upbringing, and her family.

Early yearsLorraine Vivian Hansberry was the youngest of four children; seven or more years separated her from Mamie, her sister and closest sibling, and two older brothers, Carl Jr. and Perry. Her father, Carl Augustus Hansberry, was a successful real estate broker who had moved to Chicago from Mississippi after completing a technical course at Alcorn College. A prominent businessman, he made an unsuccessful bid for Congress in 1940 on the Republican ticket and contributed large sums to causes supported by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League. Hansberry’s mother, Nannie Perry, was a schoolteacher and later ward committeewoman who had come north from Tennessee after completing teacher training at Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial University. The Hansberrys were at the center of Chicago’s black social life and often entertained important political and cultural figures who were visiting the city. Through her uncle, Leo Hansberry, professor of African History at Howard University, Hansberry made early acquaintances with young people from the African continent.

The Hansberry’s middle class status did not protect them from the racial segregation and discrimination characteristic of the period, and they were active in opposing it. Restrictive covenants, in which white homeowners agreed not to sell their property to black buyers, created a ghetto known as the “black metropolis” in the midst of Chicago’s South Side. Although large numbers of black Americans continued to migrate to the city, restrictive covenants kept the boundaries static, creating serious housing problems. Carl Hansberry knew well the severe overcrowding in the black metropolis. He had, in fact, made much of his money by purchasing large, older houses vacated by the retreating white population and dividing them into small apartments, each one with its own kitchenette. In doing so, he earned the title “kitchenette king.” This type of tiny, functional apartment became the setting in A Raisin in the Sun, just as the struggle for better housing drove its plot.

Hansberry attended public schools, graduating from Betsy Ross Elementary School and then from Englewood High School in 1947. Breaking with the family tradition of attending southern black colleges, Hansberry chose to attend the University of Wisconsin at Madison, moving from the ghetto schools of Chicago to a predominantly white university. She integrated her dormitory, becoming the first black student to live at Langdon Manor. The years at Madison focused her political views as she worked in the Henry Wallace presidential campaign and in the activities of the Young Progressive League, becoming president of the organization in 1949 during her last semester. Her artistic sensibilities were heightened by a university production of Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock. She was deeply moved by O’Casey’s ability to universalize the suffering of the Irish without sacrificing specificity and later wrote: “The melody was one that I had known for a very long while. I was seventeen and I did not think then of writing the melody as I knew it—in a different key; but I believe it entered my consciousness and stayed there.” She would capture that suffering in the idiom of the Negro people in her first produced play, A Raisin in the Sun. In 1950 she left the university and moved to New York City for an education of another kind.

In Harlem she began working on Freedom, a progressive newspaper founded by Paul Robeson, and turned the world into her personal university. In 1952 she became associate editor of the newspaper, writing and editing a variety of news stories that expanded her understanding of domestic and world problems. Living and working in the midst of the rich and progressive social, political, and cultural elements of Harlem stimulated Hansberry to begin writing short stories, poetry, and plays. On one occasion she wrote the pageant that was performed to commemorate the Freedom newspaper’s first anniversary. In 1952, while covering a picket line protesting discrimination in sports at New York University, Hansberry met Robert Barron Nemiroff, a student of Russian Jewish heritage who was attending the university. They dated for several months, participating in political and cultural activities together. They married on 20 June 1953, at the Hansberry home in Chicago. The young couple took various jobs during these early years. Nemiroff was a part-time typist, waiter, Multilith operator, reader, and copywriter. Hansberry left the Freedom staff in 1953 in order to concentrate on her writing and for the next three years worked on three plays while holding a series of jobs: tagger in the garment industry, typist, program director at Camp Unity (a progressive, interracial summer program), teacher at the Marxist-oriented Jefferson School for Social Science, and recreation leader for the handicapped.

A sudden change of fortune freed Hansberry from these odd jobs. Nemiroff and his friend Burt d’Lugoff wrote a folk ballad, “Cindy Oh Cindy,” that quickly became a hit. The money from that song allowed Hansberry to quit her jobs and devote herself full time to her writing. She began to write The Crystal Stair, a play about a struggling black family in Chicago that would eventually become A Raisin in the Sun.

Drawing on her knowledge of the working class black tenants who had rented from her father and with whom she had attended school on Chicago’s South Side, Hansberry wrote a realistic play with a theme inspired by Langston Hughes. In his poem “Harlem,” he asks: “What happens to a dream deferred?…Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?…Or does it explode?” Hansberry read a draft of the play to several colleagues. After one such occasion, Phil Rose, a friend who had employed Nemiroff in his music publishing firm, optioned the play for Broadway production. Although he had never produced a Broadway play before, Rose and his coproducer David S. Cogan set forth enthusiastically with their fellow novices on this venture. They approached major Broadway producers, but the “smart money” considered a play about black life to be too risky for Broadway. The only interested producer insisted on directorial and cast choices that were unacceptable to Hansberry, so the group raised the cash through other means and took the show on tour without the guarantee of a Broadway house. Audiences in the tour cities—New Haven, Connecticut, Philadelphia, and Chicago—were ecstatic about the show. A last-minute rush for tickets in Philadelphia finally made the case for acquiring a Broadway theater.

CelebrityA Raisin in the Sun opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on 11 March 1959 and was an instant success with both critics and audiences. The New York critic Walter Kerr praised Hansberry for reading

“the precise temperature of a race at that time in its history when it cannot retreat and cannot quite find the way to move forward. The mood is forty-nine parts anger and forty-nine parts control, with a very narrow escape hatch for the steam these abrasive contraries build up. Three generations stand poised, and crowded, on a detonating-cap (New York Herald Tribune, 12 March 1959)

Hansberry became a celebrity overnight. The play was awarded the New York Drama Critics Circle Award in 1959, making Lorraine Hansberry the first black playwright, the youngest person, and only the fifth woman to win that award.

In 1960 the NBC producer Dore Schary commissioned Hansberry to write the opening segment for a television series commemorating the Civil War. Her subject was to be slavery. Hansberry thoroughly researched the topic. The result was The Drinking Gourd, a television play that focused on the effects that slavery had on the families of the slave master and the white poor as well as the slave. The play was deemed too controversial by NBC television executives and, despite Schary’s objections, was shelved along with the entire project.

Hansberry was successful, however, in bringing her prize-winning play, A Raisin in the Sun, to the screen a short time later. In 1959, a few months after the play opened, she sold the movie rights to Columbia Pictures and began work on drafts of the screenplay, incorporating several new scenes. These additions, which were rejected for the final version, sharpened the play’s attack on the effects of segregation and revealed with a surer hand the growing militant mood of black America. After many revisions and rewrites, the film was produced with all but one of the original cast and released in 1961.

In the wake of the play’s extended success, Hansberry became a public figure and popular speaker at a number of conferences and meetings. Among her most notable speeches was one delivered to a black writers’ conference sponsored by the American Society of African Culture in New York. Written during the production of A Raisin in the Sun and delivered on 1 March 1959—two weeks before the Broadway opening—“The Negro Writer and His Roots” is in effect Hansberry’s credo. In her speech, Hansberry declared that “all art is ultimately social” and called upon black writers to be involved in “the intellectual affairs of all men, everywhere.” As the civil rights movement intensified, Hansberry helped to plan fund-raising events to support organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Disgusted with the red baiting of the McCarthy era, she called for the abolition of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Later she criticized President John F. Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban missile crisis, arguing that his actions endangered world peace.

In 1961, amid many requests for public appearances, a number of which she accepted, Hansberry began work on several plays. Her next stage production, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, appeared in 1964. Before that, however, she finished a favorite project, Masters of the Dew, adapted from the Haitian novel by Jacques Romain. A film company had asked her to do the screenplay; however, contractual problems prevented the production from proceeding. The next year, seeking rural solitude, Hansberry purchased a house in Croton-on-Hudson, forty-five minutes from Broadway, in order to complete work on The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.

Early in April 1963 Hansberry fainted. Hospitalized at University Hospital in New York City for nearly two weeks, she underwent extensive tests. The results suggested cancer of the pancreas. Despite the progressive failure of her health during the next two years, she continued her writing projects and political activities. In May 1963 she joined the writer James Baldwin, the singers Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne, and other black and white individuals in a meeting in Croton to raise funds for SNCC and a rally to support the southern freedom movement. Although her health was in rapid decline, she greeted 1964 as a year of glorious work. On her writing schedule, in addition to The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, were Les Blancs, Laughing Boy (a musical adaptation of the novel), The Marrow of Tradition, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Achnaton, a play about the Egyptian pharaoh. Despite frequent hospitalization and bouts with pain and attendant medical conditions, she completed a photo-essay for a book on the civil rights struggle titled The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality (1964).

In March 1964 she quietly divorced Robert Nemiroff, formalizing the separation that had occurred several years earlier. Only close friends and family had known; their continued collaboration as theater artists and activists had masked the reality of the personal relationship. Those outside their close circle only learned of the divorce when Hansberry’s will was read in 1965.

Throughout 1964 hospitalizations became more frequent as Hansberry’s cancer spread. In May she left the hospital to deliver a speech to the winners of the United Negro College Fund’s writing contest in which she coined the famous phrase, “young, gifted, and black.” A month later, she left her sickbed to participate in the Town Hall debate “The Black Revolution and the White Backlash,” at which she and her fellow black artists challenged the criticism by white liberals of the growing militancy of the civil rights movement. She also managed to complete The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which opened to mixed reviews on 15 October 1964 at the Longacre Theatre. Critics were somewhat surprised by this second play from a woman who had come to be identified with the black liberation movement. Writing about people she had known in Greenwich Village, Hansberry had created a play with a primarily white cast and a theme that called for intellectuals to get involved with social problems and world issues.

Lorraine Hansberry’s battle with cancer ended at University Hospital in New York City. She was just thirty-four years old. Her passing was mourned throughout the nation and in many parts of the world. The list of senders of telegrams and cards sent to her family reads like a who’s who of the civil rights movement and the American theater. The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window closed on the night of her death.

Hansberry left a number of finished and unfinished projects, among them Laughing Boy, a musical adapted from Oliver LaFarge’s novel; an adaptation of The Marrow of Tradition by Charles Chesnutt; a film version of Masters of the Dew; sections of a semiautobiographical novel, The Dark and Beautiful Warriors; and numerous essays, including a critical commentary written in 1957 on Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (a book that Hansberry said had changed her life). In her will, she designated Nemiroff as executor of her literary estate.

Hansberry’s reputation continued to grow after her death in 1965 as Nemiroff, who owned her papers, edited, published, and produced her work posthumously. In 1969 he adapted some of her unpublished writings for the stage under the title To Be Young, Gifted, and Black. The longest-running drama of the 1968–1969 off-Broadway season, it toured colleges and communities in the United States during 1970–1971. A ninety-minute film based on the stage play was first shown in January 1972.

In 1970 Nemiroff produced on Broadway a new work by Hansberry, Les Blancs, a full-length play set in the midst of a violent revolution in an African country. Nemiroff then edited Les Blancs: The Collected Last Plays of Lorraine Hansberry, published in 1972 and including Les Blancs, The Drinking Gourd, and What Use Are Flowers?, a short play about the consequences of nuclear holocaust. In 1974 A Raisin in the Sun returned to Broadway as Raisin, a musical, produced by Robert Nemiroff; it won an Antoinette Perry (Tony) Award.

In 1987, A Raisin in the Sun, with original material restored, was presented at the Roundabout Theatre in New York, the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, and other theaters nationwide. In 1989 this version was presented on national television. The year 2004 saw the first Broadway revival of the play. With the hip-hop star Sean “P. Diddy” Combs in the lead role of Walter Lee, the show attracted a large and diverse audience. For her performance as Lena Younger, Phylicia Rashad won the first Tony for best performance by an actress in a drama ever awarded to an African American woman. Audra McDonald won her fourth Tony for best featured actress for her role as Beneatha.

In March 1988, Les Blancs, much of the original script restored, was presented at Arena Stage in Washington, DC, the first professional production in eighteen years.

Hansberry made a significant contribution to American theater, despite the brevity of her theatrical life and the fact that only two of her plays were produced during her lifetime. A Raisin in the Sun was more than simply a “first” to be commemorated in history books and then forgotten. The play was the turning point for black artists in the professional theater. Authenticity and candor combined with timeliness to make it one of the most popular plays ever produced on the American stage. The original production ran for 538 performances on Broadway, attracting large audiences of white and black fans alike. Also, in this play and in her second produced play, Hansberry offered a strong opposing voice to the drama of despair. She created characters who affirmed life in the face of brutality and defeat. Walter Younger in A Raisin in the Sun, supported by a culture of hope and aspiration, survives and grows; and even Sidney Brustein, lacking cultural support, resists the temptation to despair by a sheer act of will, by reaffirming his link to the human family.

With the growth of women’s theater and feminist criticism, Hansberry was rediscovered by a new generation of women in theater. Indeed, a revisionist reading of her major plays reveals that she was a feminist long before the second wave of the women’s movement surfaced. The female characters in her plays are pivotal to the major themes. They may share the protagonist role, as in A Raisin in the Sun, where Mama is co-protagonist with Walter; or a woman character may take the definitive action, as in The Drinking Gourd, in which Rissa, the house slave, defies the slave system and black stereotypes by turning her back on her dying master and arming her son for his escape to the North. In The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, Sidney is brought to a new level of self-awareness through the actions of a chorus of women—the Parodus sisters. Likewise, the African woman dancer is ever present in Tshemabe Matoeseh’s mind in Les Blancs, silently and steadily moving him to a revolutionary commitment to his people. Hansberry’s portrayal of Beneatha as a young black woman with aspirations to be a doctor and her introduction of abortion as an issue for poor women in A Raisin in the Sun signaled early on Hansberry’s feminist attitudes. These and other portrayals of women challenged prevailing stage stereotypes of both black and white women and introduced feminist issues to the stage in compelling terms. Documents uncovered beginning in the 1980s revealing Hansberry’s homosexuality and sensitivity to homophobic attitudes have further increased feminist interest in her work.

Editor’s note: this extract from Black Women in America (2nd Ed.) was first published on the OUPblog on 14 September 2006.

Feature image: photo of a scene from the play A Raisin in the Sun , by Friedman-Abeles

The post Women & Literature: Lorraine Hansberry appeared first on OUPblog.

December 27, 2020

Women & Literature: Alice Walker

Alice Walker, perhaps best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Color Purple (1982), has always been committed to social and political change. This was nowhere clearer than in The Color Purple, which brought to light questions of sexual abuse and violence in the black community, while demonstrating the liberatory possibilities inherent in every life. The Color Purple tells the story of Celie, who is the victim of systematic gender oppression, at the hands of first her stepfather and then her husband. Despite the severe abuse Celie endures, she is a triumphant character who ultimately achieves a free and comfortable life. The principal male character—Celie’s husband, Albert—is also redeemed and so transcends his abusive past. Many critics have argued that The Color Purple is Walker’s best work, noting its inspired epistolary style (i.e., written in the form of letters) and the dynamic voice of its protagonist.

Although The Color Purple was an enormous success, it sparked considerable controversy. Some black men, who felt that her portrayals of them reinforced animalistic and cruel stereotypes about black masculinity, condemned Walker for her complexly drawn male characters. These unfair criticisms coincided with the premiere of the film The Color Purple, which did not depict domestic abuse in the complicated ways the book did. This iniquitous criticism obscured the significance of the novel, which exposed aspects of black female struggle unfamiliar to a mainstream American readership. Yet long before The Color Purple drew the attention of popular audiences, Alice Walker’s work had already established her as an accomplished artist and activist. Her work explores race, gender, sexuality, and class, building on Walker’s observations and experiences as a child and young adult in the rural South.

Childhood and youthAlice Walker was born on 9 February 1944 in Eatonton, Georgia. She was the youngest of eight children. Walker’s parents were sharecroppers, which meant that they farmed land belonging to someone else in exchange for living there. The system of sharecropping was one of cruel inequity; black workers were often exploited for their labor and rarely were paid what the crop they produced was worth. Because of this, Walker has often said that the system of sharecropping was worse than slavery because unlike slavery, sharecropping masqueraded as paid labor when in reality it was not. Walker was a hard worker and applied these lessons to her studies. Walker was an excellent student and valedictorian of her high school class; for her academic achievements she won a scholarship to Spelman College and ultimately completed her education at Sarah Lawrence College.

After graduating from college, Walker participated in various progressive movements. Never content simply to wait for an injustice to disappear or be rectified by someone else, Walker was active in the civil rights movement of the 1960s and worked in the voter registration drives. She had the opportunity to meet Martin Luther King Jr., and she attended the March on Washington. Embodying the feminist adage that “the personal is political,” Walker was married to a Jewish civil rights lawyer, Mel Leventhal, and they became the only legally married interracial couple in Mississippi at the time. She was also among the first people in the United States to teach a women’s studies course, which she instituted at Wellesley College. That these events had quite an impact on the young Walker is evident in her writing.

Art as activismJust as her experience growing up in the rural South in a sharecropping community would influence and shape her later work, so too did her experiences with activism during the civil rights movement. In Walker’s work, the relationship between her activism and her art is clear, as she repeatedly examines and exposes oppression. Walker does not simply draw back the curtain on injustice; she also imagines the transcendence of that injustice in her work. For this reason, it has often been said that all of Walker’s novels have “happy endings.” What this suggests about Walker is not that she is unrealistic but rather that she is interested in ways people who have been marginalized can overcome oppression.

Her first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland (1970), clearly draws on her experiences as a child in a sharecropping community and offers not only a critique of gender and race relations under that system but also a vision of what is possible through change. The Third Life of Grange Copeland depicts the family of Grange, his wife, Mem, and their son, Brownfield. Sharecropping renders Grange abusive and neglectful of his family; he leaves them and goes north. When his mother commits suicide, Brownfield decides to go in search of his father but never makes it farther than a few miles from home. Slipping into the same cycle of sharecropping and abuse that characterized his parents’ relationship, Brownfield becomes far more abusive than his father and ultimately ends up in jail for murdering his wife. Grange returns, largely reformed during his time in the North, to lovingly raise his granddaughter, Ruth, who, as the heroine, anticipates the strong female protagonists that characterize Walker’s work.