Oxford University Press's Blog, page 123

December 18, 2020

Read & Publish in China: Chinese Academy of Sciences and OUP’s landmark cooperation

Open scholarly communication leads to more readership, more impact, and ultimately better research. Oxford University Press (OUP) is the largest university press publisher of open access content. We published our first open access (OA) research in 2004 and launched our first fully open access journal in 2005. We now publish 80 fully OA journals and have published 115 OA books. We offer an open access publishing option on over 400 journals in our publishing portfolio and, since 2004, have published more than 75,000 OA journal articles.

In May 2020, the National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and OUP signed the first Read and Publish (R&P) agreement in Mainland China. R&P agreements allow researchers from participating institutions to read high quality, high impact research, as well as publish accepted articles through the OA model without paying an open access charge individually. These fair and equitable agreements further open access publishing in a sustainable way and help make research output available to everyone around the world.

Based on this project, Kunhua Zhao, a librarian from CAS, spoke to OUP’s Rhodri Jackson (Publishing Director, Open Access), and Kimi Zeng (Senior Consultant), to gather their views on open access publishing and R&P.

Zhao: Do you see any positive impact around the world from the OUP R&P project?

Jackson and Zeng: OUP is the world’s largest university press publisher of open access research. We publish over 15,000 OA articles every year. We see R&P agreements as one of the key methods by which we can sustainably move towards OA in line with our mission. We are very pleased to have concluded 11 R&P agreements to date globally, and are working with many of our customers on potential future agreements. In 2020 we have published more than 1,200 OA articles through R&P agreements, and we expect this number to grow.

Could you share some experience that authors from other countries/regions have when publishing OA articles with OUP that Chinese authors can learn from?

We are committed to providing a smooth and positive experience to authors all the way through the submission and publication process, to ensure that publishing in OUP journals (whether OA or non-OA) is straightforward and efficient. OA publishing is more common in some fields/disciplines than others, so we provide our authors with clear information to make sure they are aware of the OA publishing options available to them and can make informed choices.

Comparing with authors from other countries/regions, is there any specific trend or characteristic among Chinese authors when publishing OA articles?

From our surveys we find that Chinese authors are very similar to all authors—they are interested in speed of publication, as they want to make their work available to other researchers as soon as possible. They are also very keen to publish in prestigious journals with high impact. These requirements (speed and quality) are the same in both the OA model and the subscription model. OUP publishes more than 450 highly prestigious journals, and we are committed to providing fast and efficient publication for authors.

OA journals are new and often have innovative approaches which lead to fast publication. Also, without access control barriers, OA content will have more usage and the potential for more citations. Both of these characteristics are attractive to authors.

What is your view on the overall trend of Chinese authors’ publishing OA articles with OUP? Do you have any suggestion to Chinese authors regarding OA publishing?

More and more Chinese authors are publishing OA articles in OUP journals, and we expect this trend to continue. We recommend that Chinese authors choose the appropriate OA journal for their research field. All OUP journals are of high quality and will ensure worldwide discoverability for Chinese authors’ articles.

We are excited that OUP and CAS signed the first R&P agreement in Mainland China, which we believe will open up even more opportunities for Chinese authors to publish OA with OUP, along with giving researchers at the participating CAS institutions access to the prestigious OUP journals collection.

What’s your advice and expectation to the future of the OA transformation of China ?

We continue to see great movement towards open access in China. In recent years, OUP has moved three of our China-based journals to fully OA models—National Science Review(published in association with China Science Press), Journal of Molecular Cell Biology (CAS Centre for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science), and Journal of Geophysics and Engineering(Sinopec Geophysical Research Institute). All three of these journals have thrived since switching to OA.

CAS and OUP signing the first R&P deal in Mainland China is a further important landmark in the global shift towards open access. We are looking forward to the expansion of the CAS deal and more OA publishing from Chinese authors, and are excited to be an active part of this transformation.

Journals from OUP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. As one of the world largest university presses, it furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OUP has over 100 years of experience producing journals. We publish over 400 prestigious, highly cited, and authoritative journals that are published in partnership with many of the world’s most influential scholarly and professional societies, covering areas in Medicine, Life Sciences, Humanities, Social Sciences, Mathematics & Physical Sciences, and Law to bring frontiers research output to researchers, faculty, and students.

This is an edited version of an interview that was initially published on WeChat by OxfordAcademic. Read the original article in Chinese here .

Feature image by Huiyu Xia.

The post Read & Publish in China: Chinese Academy of Sciences and OUP’s landmark cooperation appeared first on OUPblog.

December 17, 2020

Biotechnology: the Pentagon’s next big thing

Biotechnology has long been an important field of scientific research. But until recently, it has never been formally considered by any military as a significant technological investment opportunity, or a technology that could revolutionize the conduct of war. For example, the Pentagon’s Defense Science Board (DSB), that helped then Secretary of Defense Harold Brown identify technologies central to the second offset strategy in 1976, and helped then deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work identify AI as the key for the third offset strategy in 2014, explicitly opted not to include biological threats in its analysis of known surprises in 2009. Neither did it include biotechnology in the list of key investment opportunities to avoid surprise in 2013.

However, recent studies by the DSB and the National Security Commission on AI (NSCAI) indicate that the Pentagon has changed its mind. It is now preparing for a new biotech revolution in military affairs (RMA), or a new offset strategy, in order to win the long-term strategic competition with China.

In contrast to its previous studies, the DSB’s latest report published in September concludes that, “the threats and opportunities presented by new bio-enabled capabilities will be significant, and the DoD must ensure it does not fall behind other nations lest it lose its technological edge to competitors in a field that may play a transformational role.” Following the study’s recommendations, the DoD established an Assistant Director for Biotechnology in 2019. The NSCAI went so far as to argue that, “the combination of advances in AI and biology have the potential to reshape the global economy for the next century.” It reached a similar conclusion that China’s weaponization of biology would pose a significant threat to US national security. And biotechnology would be central to the future geostrategic competition.

Drawing on the “first offset” and “second offset” strategies, the forthcoming offset strategy is working under the assumption that a combination of AI and biotech might actually transform the conduct of war. This strategy, in essence, will be an effort to build on US’s own enduring strengths and exploit China’s enduring weaknesses and vulnerabilities. The following measures are likely to be employed for this military-technical competition.

First, marshalling international partnerships to develop a strategic technology plan to compete with China. As Michael Brown and William Perry did in the 1970s, the Pentagon will identify the most demanding operational challenges the US and its allies would face in a conventional war versus China, and develop a strategic technology plan to support this offset strategy. Allies and partners is one of the US’s key advantages over China. The US has been creating a coalition of coalitions, or a system of systems with its allies to compete with China. NSCAI Commissioner Jason Matheny urges the US to “coordinate AI developments with NATO and making India the focus of the United State’s Indo-Pacific AI strategy to counter China.” And this is in line with Joe Biden’s idea of forging a technological future with its allies.

Second, developing operational concepts and making organizational changes that fully exploit the available technologies. The interwar experience suggests that militaries that do better in developing operational concepts, and making organizational changes will prevail. US National Defense Strategy (NDS) argues that, “success no longer goes to the country that develops a new technology first, but rather to the one that better integrates it and adapts its way of fighting.” China is relatively slow in creating new concepts of operation, and even slower in making organizational adaptations. PLA Lieutenant General Liu Guozhi, the director of the Central Military Commission’s Science and Technology Commission, is frustrated, saying that “change of mindset is very hard, overcoming obstacles from interested groups is even harder. But those two problems often exist simultaneously.” In other words, it takes China longer to convert technological advances into military capabilities. If the US moves fast enough, China will always be a follower learning from and responding to the US’s way of war.

Third, drawing on cold war strategies, the US will resort to grey zone operations in order to impose costs on China. NSD is concerned about China’s grey zone activities and determined to push back against China with all measures short of war. Inspired by the case of Poland’s Solidarity in the 1980s, the US and its allies have launched a global name-and-shame campaign on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, South China Sea issues, as well as Chinese influence operations in Australia. Those information campaigns successfully helped them disrupt China’s 5G roll-out in Europe. It seems that they will double down on this approach by launching an information campaign against China Standards 2035, and “a strategic communications campaign to highlight BGI’s links to the Chinese government and how China is utilizing AI to enable ethically problematic developments in biotechnology and strengthen international bioethical norms and standards regarding genomics research.”

While the Pentagon is pondering on a potential biotech RMA, Chinese analysts are closely monitoring DARPA’s investments, and NATO’s interest in this field. They have taken notice of the President’s Science Advisor, Kelvin Droegemeier’s remarks on biodefense, and are aware that the US is “looking to play a strong offensive game” in this regard. In short, as it did in the 1980s, the People’s Liberation Army will waste no time to join this biotech RMA if they conclude that the US is already on it. However, biosecurity is an international challenge, in order to avoid a race to the bottom, the two militaries should talk to each other and be more transparent about their biotech advancements and intention.

Featured image by Jarmoluk

The post Biotechnology: the Pentagon’s next big thing appeared first on OUPblog.

December 16, 2020

The ubiquitous whelp

Today, I will go on with my story of animal baby names (see the post “A zoological kindergarten” for December 9, 2020). The previous essay ended with the question: “Does whelp have anything to do with wolf?”

Where do whelps come from? The Century Dictionary explains: “The young of the dog, wolf, lion, tiger, bear, seal, etc., but especially of the dog; a cub: sometimes applied to the whole canine species, whether young or old.” This definition is broad. Most of us may say that dogs produce puppies and that bears give birth to bear cubs (rather than just cubs). Perhaps it is more common to associate whelps mainly with wolves. Rudyard Kipling mentioned the great black panther Bagheera, to which I referred last time, and his (his!) cubs, not whelps. In connection with the origin of language, I have read many works about the life of seals and their system of communication. There, if I remember correctly, baby seals are usually called pups.

Whelps without a riddle. (Image by diapicard)

Whelps without a riddle. (Image by diapicard)It may be useful to repeat that the etymology of many animal names, horse, mare, sheep, and ram among them, is disconcertingly obscure. At first sight (but alas, only at first sight), a bit less opaque is the etymology of such homey words as pup, cub, and bun, though here too dictionaries tend to say: “Origin unknown.” Calf, fawn, colt, filly, lamb, and whelp don’t even look transparent. Does whelp have anything to do with wolf? Linguistic algebra connects wolf, Latin lupus, Russian volk, and other similar names in Indo-European. The most ancient form seems to have begun with wl-. Whelp, by contrast, once began with hw– (see the previous post). No secure Indo-European cognate of whelp has been found, but, according to the correspondence known as the First Consonant Shift, if such a cognate exists, it should begin with kw– (compare Engl. what, from hwæt, and Latin quod, that is kwod). This does not augur well for a much-desired family reunion: wl– and kw– do not belong together. We also find Latin vulpes “fox,” and no one knows whether it is cognate with lupus. (Vulpes and whelp have been listed as possibly related in the works by Gottfried Baist, 1853-1920, an excellent Romance scholar.) In the Scandinavian languages, the wolf is called varg(u)r, apparently, no relative of either wolf or whelp.

When a word is opaque, conjectures about its origin multiply. Some guesswork about whelp is not devoid of interest. Last week, I mentioned a curious circumstance: goslings, ducklings, and chickens remind us of their parents (the goose, the duck, and the cock), while baby mammals are given names that have nothing to do with those of their fathers or mothers. Yet English child shares the root with the word for the womb, as known from Gothic, the oldest recorded Germanic language (see again the previous post). A similar connection has also been sought for whelp. Old English –hwelfen meant “to arch, bend over, vault over; cover.” Related forms existed everywhere in Germanic. Thus, German had welben; its continuation is the modern form wölben. According to a fairly recent hypothesis, a word like Wölbung “curvature; arch” might refer to “womb,” with whelp being its fruit. Gothic hwilf-tr-jos “coffin,” Sanskrit garbhah “womb,” and Greek kٖólpos “breast” have been cited in this connection. Mere guesswork, as William W. Skeat used to say in such cases, but, in similar fashion, Edgar Polomé, our contemporary (1920-2000), connected English bitch with Sanskrit bhaga “vulva.” Both hypotheses (of the origin of whelp and of bitch) strike me as extremely risky.

Can seals speak? (Image by Foto-Rabe)

Can seals speak? (Image by Foto-Rabe)Two types of hypotheses compete in etymology. One is learned and the other disconcertingly simple, so that an impartial observer is sometimes hard put to it to choose between them. English whelp resembles the verb yelp, obviously a sound-imitative word, like yap and yawp. Is it possible that such is the origin of whelp? In Old English, hwilpe, some bird (possibly a curlew) was mentioned, and a similar Dutch bird name is extant. Hwilpe is obviously a sound-imitative (onomatopoeic, echoic) word, like curlew and, incidentally, like cur! This derivation of whelp has been offered by several excellent specialists. (As usual, I am giving no exact references. Anyone interested in the literature on whelp or any other word I discuss in this blog will find it in my Bibliography of English Etymology or may write me an email. Satisfaction guaranteed.)

In an indirect way, the echoic hypothesis of the origin of whelp finds confirmation from another direction. The Germanic word sounds like some words for “dog” in Semitic (Arabic kalbu, Hebrew keleb, and so forth; other transliterations also exist) and very much like the Germanic word for calf (I mentioned calf last week). Here, my earliest citation goes back to 1946, but perhaps the similarity was noticed much earlier. Two explanations for this fact suggest themselves. Either we are dealing with a very ancient word that was common to the speakers of Semitic and Indo-European or the coincidence is due to chance (all people invent nearly the same onomatopoeic complexes while imitating animal sounds). Borrowing from Semitic into Indo-European or from Indo-European into Semitic is less likely, though a migratory word of this type may have existed. I am severely temped to accept some such hypothesis, but proof is wanting. The mysterious whelp is, rather probably, a widely traveled yelper.

Solving an etymological riddle. (Image by Robert Gramner)

Solving an etymological riddle. (Image by Robert Gramner)Finally, in Hittite, an Indo-European language once spoken in Anatolia, the word hwelpi– turned up, with the same meaning as whelp. Since Hittite is not a Germanic language, a cognate of whelp in it should have begun, with kw– (see above). What is the explanation? Are we reading another chapter in the history of migratory words? Or has an echoic word once again crossed our path? We’ll never discover the only correct answer, but at the end of the way, we seem to be better off than those who open a dictionary and are told that whelp is the name of a young dog, wolf, tiger, etc., but that, though its cognates occur in several Germanic languages, its origin is, alas, unknown.

This is the last post for 2020. I am alive and well, but during the holiday season, strategic planning in the OUP offices is, naturally complicated. We’ll meet again on the first Wednesday of 2021. I’ll continue the series “Baby names,” and, if everything goes well, in early March, we’ll celebrate the fifteenth anniversary of the weekly blog “The Oxford Etymologist.” But so far, we are in 2020, and, as usual at this time, I hasten to thank my hard-working editors, the readers of my essays, and our correspondents and wish them a happier, safer, and healthier New Year than the one we are now leaving behind.

Feature image by congerdesign

The post The ubiquitous whelp appeared first on OUPblog.

December 15, 2020

The role of the university in international cooperation

In the midst of a pandemic, we seldom hear universities mentioned as crucial sites for international understanding and cooperation. Images of students confined to their housing dominate the media cycle. More generally, business models that reduce programmes to products, students to customers, and education to a means for economic growth prevail. Political activism on-campus is rarely encouraged or celebrated in public life.

A hundred years ago, in the aftermath of the First World War, the situation was quite different. The League of Nations regarded education as central to the propagation of ideas of peace. It also considered universities as critical crossroads for international communication. Its Committee for Intellectual Cooperation, staffed largely by academics, pushed for student and faculty exchange and coordinated communications among a wide array of organisations. After 1945, these programs continued; and in subsequent decades programmes such as the European Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students (ERASMUS) built and expanded on this tradition.

Pandemics and deadly diseases did not stop the work of putting education—and especially universities—at work to build international understanding and cooperation. Inspired by the League’s work, Dr Louis Vauthier established an international University Sanatorium in the Swiss village of Leysin. From the 1920s to the 1950s, students and faculty from all disciplines continued their academic work while undergoing lengthy treatments for tuberculosis. Guest lecturers administered the teaching, while universities world-wide stocked the University Sanatorium’s library with the latest publications. Hundreds benefitted from this institution, as illustrious visitors—most famously Gandhi—turned the clinic into a symbol of peace and interwar internationalism.

Indeed, scores of contemporaries celebrated the success of this experiment. Rather than conceding to depression, which often accompanied lengthy and debilitating illnesses such as tuberculosis, University Sanatorium patients devoted themselves enthusiastically to their work. At a time of increasing nationalism and political polarisation, they entangled collaborations and friendships many thought would translate from the educational to the political realm.

If antibiotics eventually made the University Sanatorium redundant, Vauthier’s experiment continued to be influential and still provides useful insights for the present. To be sure, some of the accounts of its success might reflect intentions and attempts at marketing more than reality; and some of the assumptions of that time—such as the inherent superiority of intellectuals or the demographic composition of that group, for instance—are best left to the past. But the notion that education sits instead at the core of any peaceful democratic international society is worth resurrecting in our times. Indeed, like it did a century ago, it might help to counter rising authoritarianisms in all of their forms. It might also help to face growing mental health challenges while also restoring the value of expertise and of those who pursue it.

What would a strategy inspired by this history look like in practice? First, it would make us conceptualise “student experience” in a different way, bringing out its collective features and the intercultural, political, and civic values of learning. Second, at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed down student and faculty travel, and despite efforts at digitisation, access to both libraries and archives has been greatly reduced, it would prioritise student and faculty exchanges as key to the formation of future generations of world citizens; it would also protect access to research facilities to include the vitality of what Vauthier would have called “intellectual” work in the recipe for future cultural, societal, and civic life both domestically and abroad.

Feature image by Moshe Harosh

The post The role of the university in international cooperation appeared first on OUPblog.

December 14, 2020

25 years of Very Short Introductions: listen to the anniversary podcast series

In 2020 we are proud to be celebrating the 25th anniversary of our Very Short Introductions. The series was launched in 1995 with Mary Beard and John Henderson’s Classics: A Very Short Introduction, and since then we have published over 600 titles in the series, showcasing introductions to a wide range of topics such as arts and humanities, social sciences, and science—covering everything from environmental ethics to Chaucer. The series is continually growing with new titles on the American South, silent film, and enzymes recently added to the series.

“The best Very Short Introductions will educate general readers, students, and academics alike. Speaking for my fellow academics, I have not been surprised to find how many of us esteem them as handy and reliable introductions to subjects on the more distant horizons of our professional knowledge.” —Jane Caplan, The American Historical Review

The series has evolved to include Very Short Introductions Online and now The Very Short Introductions Podcast to mark the series anniversary. The Very Short Introductions Podcast offers a concise and original introduction by our Very Short Introductions authors to a variety of dynamic topics, with episodes on The Middle Ages, fashion, globalization and more, for wherever your curiosity may take you.

Here are just a few of the latest podcast episodes on our VSI titles:

Episode 12: SynaesthesiaIn this episode, VSI author Julia Simner introduces synaesthesia, a neurological condition that gives rise to a ‘merging of the senses’, in which words can be tasted and colours can be heard.

Listen to the podcast episode via Apple, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Episode 8: BrandingIn this episode, VSI author Robert Jones introduces possibly the most powerful commercial and culture force globally–branding–which, despite brand awareness and skepticism, holds an inescapable influence on our lives.

Listen to the podcast episode via Apple, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

Episode 13: AtheismIn this episode, VSI author Julian Baggini introduces atheism, wrongly considered to be a negative, dark, and pessimistic belief characterized by a rejection of values and purpose and a fierce opposition to religion.

Listen to the podcast episode via Apple, Spotify, or your favourite podcast app.

You can find out how to listen and subscribe to The Very Short Introductions Podcast here.

The post 25 years of Very Short Introductions: listen to the anniversary podcast series appeared first on OUPblog.

December 11, 2020

Nineteenth-century US hymnody’s fascination with classical music

The aria Zerlina sings to Masetto, her fiancée, late in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni is a study in sexual innuendo.

Masetto’s just received a brutal beating from the Don (whose lascivious designs on Zerlina were only narrowly averted). But if Masetto will come home with her now, Zerlina coaxes, she’s ready to administer her own pleasant balm. It’s a natural cure, she says, that she carries with her everywhere. One no chemist can make. Just as erotic undercurrents threaten to surface (“Do you want to know where I keep it?”), out comes Zerlina’s final line, revealing that her beating heart is all she was talking about. But it’s a punchline, comical and self-aware. Zerlina knows no one thought she was talking about her heart.

However risqué it may have seemed at its 1787 premiere, this aria is unlikely to strike many opera-goers today as particularly indecent.

What’s much more likely to seem indecent today is this melody’s appearance in the 1856 American collection The Sabbath Bell, edited by George F. Root (listen here). In The Sabbath Bell, Mozart’s tune appears much as Zerlina sang it, but matched with different words:

Brightest and best of the sons of the morning,

Dawn on our darkness and lend us thine aid.

Star of the east, the horizon adorning,

Guide where the infant Redeemer is laid…

What gives? How could it ever have seemed like a good idea to set one of the most familiar Christmas hymns in the English language to a tune intended by Mozart (a genius at close-binding music to drama) as a vehicle for a seductive outpouring of double-entendre?

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, American audiences ate this sort of thing up. Hymnody was the best-selling form of American popular music through most of this era—Lowell Mason’s 1841 sacred collection Carmina Sacra may briefly have been the best-selling music publication in history, with sales around 500,000. And in a mounting wave that began around 1820, hymnodic adaptations of classical music abounded. Hundreds appeared.

A few survive today. Millions still sing “Joyful, joyful we adore thee” to a subject from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony first published as a hymn tune in New York in 1846. But the vast majority are long forgotten.

And it’s a tough repertoire to know what to do with today.

Simply heaping scorn—or at least patronizing bemusement—on the whole notion of radically repurposing tunes plucked from operas or symphonies amounts to a kind of amnesia. In the early 19th century, classical music circulated in the US mostly through excerpts, which were subject to all manner of simplifying, repackaging, and retexting. Full-blown US performances of operas and symphonies were comparatively rare, but isolated tunes tumbled forth from them as freely (if not as frequently) as hit songs disentangled themselves from Broadway shows a century later.

Another reason it’s tough to dismiss these hymnodic adaptations out of hand, though, is that they often work really well.

True, they routinely ask tunes to participate in communicating sentiments far removed from those their composers intended. But most music is nimble that way. The “meanings” music bears are usually general—tied less to things than to feelings or impressions, evocative rather than denotative, inclined to polyvalence. Even palpably descriptive music usually relies on lyrics, titles, or other representational media to tell us what it’s actually describing. John Williams’s Jaws score may be unsurpassed as a translation of a shark attack into tones, but it’s still unlikely to suggest “shark” to a listener wholly unfamiliar with the movie.

And for a listener unfamiliar with Mozart’s Don Giovanni—to return to our starting point—the music of Zerlina’s seductive aria is apt to work superbly as a setting of “Brightest and best.” Grasping why involves digging more deeply into what Zerlina’s music actually meant in the first place.

Mozart’s artistic world was organized around a lexicon of musical “topics”: characteristic figures, styles, and rhythms rich with associations (vaguely akin to what we call “genres” in modern pop-songs—country, dubstep, metalcore, and so on). Zerlina’s aria partakes of the “pastoral” topic, recognizable in the basses’ fixation on one note, the triple meter, and the gentle, parallel motion of the top two voices. The pastoral topic’s deepest associations were with idyllic outdoor scenes, but by Mozart’s time, it routinely stood for generalized, idealized innocence.

Thus, Zerlina’s words are about physical intimacy, but her music is not. Her music is about why physical intimacy stands, for Zerlina and Masetto, to be redemptive. Her pastoral pose reassures Masetto that, despite Don Giovanni’s drive to corrupt, the innocence of conjugal bliss remains intact for them, unsullied and within reach.

Reassigning Zerlina’s pastoral tune to a Christian nativity scene like “Brightest and best” doesn’t just work. It brings the pastoral topic home. Talk of livestock in the hymn’s second verse (“Low lies his head with the beasts of the stall”) returns us directly to the meaning of the Latin word “pastor”: “shepherd.” And the baby whose head lies there would grow up, after all, to invite his followers to think of him as “the good shepherd” (John 10:11 and 10:14). Most important, that generalized sense of the embrace of innocence, even in the face of corruption, that served Zerlina so well takes on cosmological resonances for the Christian singing this hymn.

Not all of those hymnodic adaptations 19th-century Americans so adored work as well as this one. But many do. There’s a great deal of resourcefulness and artistic sensitivity in them. Indeed, one wonders if this whole repertoire might, like Zerlina and Masetto themselves, deserve a second chance.

Feature image by Michael Maasen

The post Nineteenth-century US hymnody’s fascination with classical music appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2020

Obama, Trump, and education policy in US federalism

In just a few weeks, Joseph R. Biden Jr will take his oath as the 46th President of the United States. Like his predecessors in recent decades, Biden intends to use executive and administrative actions to pursue his policy agenda. In public education, a policy domain for which states assume constitutional responsibility, administrative presidency faces the forces of federalism. The presidencies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump offered contrasting lessons on the exercise of presidential power in a system of decentralized policymaking. While Obama broadened the equity agenda and strengthened federal oversight on state roles, Trump used executive tools to promote state policy authority, diminish federal direction on civil rights, and expand private school choice.

Shift in federal-state relationshipObama was actively engaged in education policy. He granted waivers to over 90% of states on meeting proficiency goals under the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB); created multiple financial incentives for states to adopt the Common Core of academic standards and to improve teacher quality; and guided states on intervention strategies to turn around the lowest performing schools. The Obama presidency purposefully used administrative power to address the nation’s challenge of inequality in education.

Trump was ready to scale back on Obama’s engagement in education. Trump’s unilateral action faced particularly favorable political conditions during the first two years of the administration when the Republican Party had control over both houses of Congress and about 60% of the states. The Trump administration adopted a deferential approach to the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act. Guided by Trump’s executive order, the Republican-controlled Congress used the Congressional Review Act to repeal the Obama-era rules on the states’ accountability plans. Granting states significant flexibility created uncertainties on state actions to address educational equity. Trump’s deferential approach enabled significant state variation in selecting accountability standards, performance timeline, and school improvement strategies.

Federal role in equityHistorically, equity has been a key justification for federal involvement in K-12 education. Throughout his two terms, President Obama used administrative action to elevate the nation’s attention to racial/ethnic, income, gender, and sexual orientation inequity in schools. Obama’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) in the US Department of Education conducted extensive monitoring of civil rights violations related to gender discrimination (Title IX), the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) students, as well as students with disabilities and other needs. Obama established an interagency task force to address complex challenges that African-American children and youth faced, including violence, an achievement gap, chronic absenteeism, and poor school quality. To improve schools for Native Americans on reservations, Obama supported tribal self-governance, promoted early access to integrated services, and strengthened teacher recruitment and retention.

The Trump administration scaled back investigations into civil rights violations and shifted away from Obama’s focus on systemic barriers in public schools and universities. Trump’s OCR revised the guidebook on investigation by removing the procedures to be used in establishing systemic bias. Starting in February 2020, OCR granted state flexibility and regulatory relief in administering civil rights issues. Consequently, the pace of case closures and dismissals was much faster than that of the Obama years, which had required signoffs from DC headquarters for case closures.

The Trump administration’s reversal on civil rights enforcement also affected issues pertaining to racial/ethnic discrimination in school disciplinary actions. Trump’s Department of Justice and the Department of Education jointly issued a Dear Colleague Letter notifying schools of their withdrawal of the policy guidance that the Obama administration had issued on nondiscriminatory school discipline in 2014. The Trump administration justified its action on grounds that “states and local school districts play the primary role in establishing educational policy.” The decision triggered sharp opposition from Democratic lawmakers and civil rights organizations. California, New Hampshire, and several states responded to the weakening of federal support by bolstering their own protections for students with disabilities.

Private school choiceTrump aimed to scale up his school choice initiatives with a large infusion of federal funds. He made this promise during the 2016 campaign, pledging $20 billion in federal funding. In his first appearance before a joint session of Congress in February 2017, Trump proposed using federal funding for private school choice. Even though Trump’s proposal did not receive Congressional support, his administration took actions to promote school choice across states.

The Trump administration moved to ease the administrative burdens of states to support school choice and services for private school students. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos joined Republican lawmakers in championing legislation that would allow states to provide individual and corporate donors dollar-for-dollar tax credits for contributing to scholarship programs that help families pay private-school tuition. Clearly, Trump’s agenda to promote private school choice aligned with initiatives adopted by the Republican leadership in several states. Florida, Oklahoma, New Hampshire, and North Carolina allocated state and other funds to establish private school scholarships. The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, for example, supported students who previously attended public schools that experienced a significant enrollment decline. South Carolina offered an example of a major state initiative that would have involved millions of federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Actto support students to attend private schools. However, the state court in South Carolina prohibited Governor Henry McMaster from implementing the CARES-funded Safe Access to Flexible Education program to enroll 5,000 students to attend private and religious schools.

Federalism enduresBeginning on 20 January 2021, the Biden presidency will shift away from Trump’s agenda and restore an active federal role. To be sure, the dynamics of federalism endures. While Republicans control both the executive and the legislative branches in 24 states, Democrats dominate in 15 states in 2021. Divided governance prevails in the remaining 11 states. Clearly, the governing landscape across states will continue to define the federal-state relationship as the president prioritizes administrative action to pursue equity and quality goals in public education.

Featured image by Motion Studios

The post Obama, Trump, and education policy in US federalism appeared first on OUPblog.

December 9, 2020

A zoological kindergarten

About two months ago, Mr Timothy Meinch wrote me that he was working on an article about the names of baby animals and asked me a few questions. Later, we talked on the phone, but he decided not to go to great etymological lengths and produced an entertaining piece for the journal Discovery about such names, with a brief reference to our conversation and a series of cute pictures. Words like pup and cub are not too numerous—nothing resembling the endless array of terms for groups of animals (a flock of sheep, a litter of pigs, a pack of wolves, a herd of elephants, a school of fish, and so forth), but a few are exotic. This episode suggested to me that a more in-depth discussion of some of the names featured in Discovery could be of interest to the readers of this blog.

It is not necessary to have seven kids for a hungry wolf

It is not necessary to have seven kids for a hungry wolfThe first, perhaps surprising, thing about the words I’ll address below is that language rarely associates the names of adult animals with the names chosen for their progeny. Yet the same is true of humans! Wouldn’t it be natural to call a little boy manling and a little girl wifeling (wife at one time meant “woman”)? Kaa, the great python in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, calls Mowgli “manling,” and the word also turns up in another context in this work, but also in the speech of an animal. Be that as it may, for some reason, we have boy and girl (both words are of unclear origin; anyone interested in a full discussion of them will find it in my Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology). Language sometimes treats babies with condescension, to put it mildly, because the same word may refer to a small child and all kinds of worthless (!) objects. Other words of this type are borrowings from the “nursery,” as they used to say in the past, that is, from babbling or from adults’ imitation of babbling. Puppet and puppy, with their reduplication (p/p), along with papa, mamma, and baby, have always been recognized as imitating baby words. The same must be true of the verb babble. Children like to play with animals. That is why dolls and small pets sometimes have similar names.

In this context, only one association is worthy of mention. A baby is the fruit of the womb. In English, only child reminds us of this natural connection. The evidence comes from Gothic (a Germanic language, recorded in the fourth century CE); in it, the noun kilþ-ei “womb” turned up (þ had the value of th in English thick), and Old English cild– is an exact cognate of kilþ-. Not improbably, Engl. calf has the same root, but I’ll deal with calf later. German Kin–d “child” is akin (!) to English kith, kindred, and of course, kin. Kind and child are different words.

A baby deer fawning on its mother

A baby deer fawning on its motherNothing is more natural than my idea of calling a boy manling. Compare mannikin “little man” and its doublet mannequin, which traveled to France and returned to its native Germanic soil with a specialized sense. If modern logic were allowed to triumph, we would have had a dozen etymologically transparent words like chicken and gosling. Chicken has the root of cock “rooster” (indeed, on a different grade of ablaut) and a diminutive suffix (-n ~ -en), typical of animal names. Such is also Gothic gait-ein “kid,” that is, “little goat.” Also, kitten looks like an animal name with the same old suffix, but its Romance (Anglo-Norman) source ended in –oun; it was modified much later. Duckling and gosling are perfect too, because –ling is another diminutive suffix.

Judging by the evidence of language, little mammals, contrary to little birds (chickens, ducklings, goslings), are rarely associated with their parents. An especially curious case is piglet, a humorous, late coinage, which most of us probably remember thanks to Milne’s story of Winnie the Pooh and his friends. Once upon a time, English had a “respectable” name for a little pig, namely, farrow, related to German Ferkel (the same meaning) and Latin porcus (which we recognize in pork and porcupine), but it acquired the sense “a litter of pigs,” and language failed to produce a replacement from a different root.

Those who coined animal names were indeed guided by logic; the trouble is that it did not coincide with ours. The names of grownup animals occasionally reflected their functions (forget about slang and think of such modern words as beefer and milker), and the train of ancient people’s thought can sometimes be reconstructed, but in most cases the sought-for origin remains unknown. The same holds for the name of their babies. It is obvious that ewe ~ sheep and ram don’t correlate with lamb; cow and bull have nothing to do with calf, foal has no ties with its parents stallion ~ stud and mare (but filly comes in most useful!), and think of stag, doe ~ roe, and fawn. Occasionally new names ousted their venerable predecessors: for instance, sheep (Germanic) supplanted ewe (a word of great Indo-European antiquity). Horse and German Pferd have nothing to do with Latin equus, kid does not resemble goat (goats have been maltreated more than any other inhabitants of our animal farm: English has only billy goat and nanny goat or he-goat and she-goat), and so on. I have discussed a few animal names in this blog (see the post of 4 October 2017 on ewe, lamb, and sheep) and devoted an entire series to dog (the first installment goes back to 4 May 2016).

Today, I’ll begin a story of whelp, because my topic is the names of baby animals, but a last aside is still needed. Few words give more trouble to etymologists than animal names, even though being in trouble is an etymologist’s natural state. One of the reasons for their predicament is that animal names tend to become migratory words (Wanderwörter, as they are called in German). Since our early ancestors were hunters and nomads and depended on animals for their well-being, the names of their prey and domesticated animals traveled with them. All that happened so long ago that the paths of the ancient hunters and nomads can seldom be recovered with certainty.

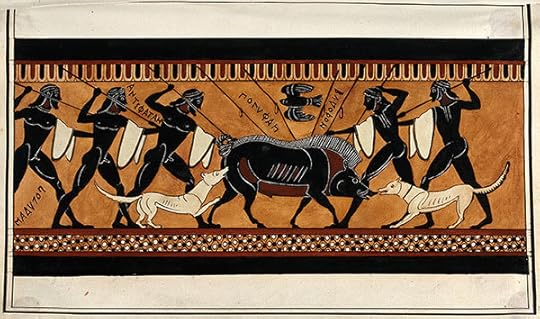

It is hard to trace these hunters’ paths. (Image: principal scene of the “Hunt krater”, made in Corinth ca. 570 B.C.. Watercolour by A. Dahlsteen, 176- (?). Credit: Wellcome Collection.)

It is hard to trace these hunters’ paths. (Image: principal scene of the “Hunt krater”, made in Corinth ca. 570 B.C.. Watercolour by A. Dahlsteen, 176- (?). Credit: Wellcome Collection.)Now back to whelp. The word’s Old English form was hwelp. The modern spelling is predictable. Many words that once began with hw– are today spelled with wh-. Some people still pronounce hw– in why, what, where, and so forth and distinguish which from witch and wen from when. Whelp has several cognates: Old Saxon hwelp, Old High German hwelf, and Old Norse hvelpr. The modern reflexes (continuations) still sound almost the same: Dutch welp, German Welf, Icelandic hvalpur (with similar forms in the other Scandinavian languages). And here the spoor becomes cold: no obviously related forms have been found outside Germanic. The questions this situation poses are familiar. Was whelp a local Germanic coinage whose initial “motivation” we are unable to guess, or does the word have related forms elsewhere in Indo-European (if so, where are they?), or, finally, are we dealing with a borrowing from an unknown source (substrate)? And the most obvious question: does whelp have anything to do with wolf?

This is where I’ll resume my story next week.

The post A zoological kindergarten appeared first on OUPblog.

December 8, 2020

10 little-known facts about Sissle and Blake’s Shuffle Along

In May 1921, Shuffle Along, a musical with music and lyrics by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, premiered on Broadway. Written, staged, and performed entirely by African Americans, it was the first show to make African-American dance an integral part of American musical theater, eventually becoming one of the top ten musical shows of the 1920s. Despite many obstacles Shuffle Along integrated into Broadway and introduced such stars as Josephine Baker, Lottie Gee, Florence Mills, and Fredi Washington. Here, Richard Carlin and Ken Bloom provide a list of ten little-known facts about the show.

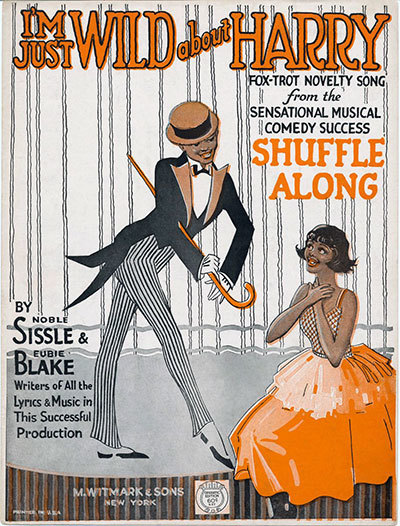

Shuffle Along was the first Broadway musical play with a book, music, dance, and cast created by African-Americans. The show’s book was written by its lead comedians Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles; the lyrics and music were written by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. Both had successfully toured on white vaudeville. The four formed a production company to produce the show.The original production launched the careers of many future stars, including Florence Mills and Josephine Baker. Mills became a major star in Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds revues before her tragic death just six years after Shuffle Along. Her funeral procession was a major event in Harlem. Baker made her mark as a comic dancer in the show’s chorus line before moving to Paris, where she became an international sensation. Cover of sheet music of “I’m Just Wild About Harry”, from the Shuffle Along, 1921. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)

Cover of sheet music of “I’m Just Wild About Harry”, from the Shuffle Along, 1921. (Image via Wikimedia Commons.)One of its hit songs, “I’m Just Wild About Harry,” gained renewed popularity in 1948 as Harry S. Truman’s campaign song. Blake wrote the original song as a waltz. Lead actress Lottie Gee, who sang the song, asked, “How can you have a waltz in a colored show?” Along with lyricist Noble Sissle, she insisted that he “make it a one-step,” and it became a hit dance number in the show.“Love Will Find A Way,” the featured duet between the young lovers Roger Matthews and Lottie Gee, was controversial because it portrayed black romance as equal to whites. Noble Sissle recalled that “We were afraid that when Gee and Matthews sang it [on the show’s opening night that] we’d be run out of town. [We] were standing near the exit door with one foot inside the theatre and the other pointed north toward Harlem. … Imagine our amazement when the song was not only beautifully received, but encored.”Several of the members of the show’s orchestra—including Felix Weir, Hall Johnson, and William Grant Still—would go on to distinguished careers in the classical and popular music fields. Weir founded the American String Quartet, perhaps the earliest black classical ensemble. Johnson achieved fame in 1928 as the leader of his eponymous choir that toured the country and appeared in many motion pictures. Grant Still was the most accomplished of black composers of his time, composing everything from songs to symphonies, including the major work the Afro-American Symphony.Shuffle Along opened on Broadway—just barely—at the 63rd Street Music Hall, about half-mile north of the heart of the theater district. The former lecture hall had hosted everything from political events to classical soloists. It was hardly a desirable location; a critic described it as being “sandwiched between garages and other establishments representative of the automobile industry, [which] was little known to the average Broadway theatregoer.” The space had a small stage and didn’t even have an orchestra pit. Blake commented that the theatre “violated every city ordinance in the book,” adding ironically, “It wasn’t Broadway but we made it Broadway.”Shuffle Along set new standards for how black performers could appear on stage. While its two comic leads appeared in blackface—honoring the age-old stereotypes of minstrelsy—the rest of the cast did not. The actors portrayed a wide range of characters, including middle-class merchants and politicians—well-beyond the norm for the mainstream stage. When Sissle and Blake appeared towards the end of the second act to perform some of their hit songs, they wore the same tuxedos that they sported on the vaudeville stage.Despite wearing blackface on stage, Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles were both college-educated actors, having first met as students at Fisk University in Nashville. Miller wrote most of their material, which was based on comic wordplay along with physical humor. Their act was so successful it was widely copied, most notably by radio comedians Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, aka Amos ‘n’ Andy. Ironically, Miller would be employed by the duo to write many of their later radio and TV shows.Shuffle Along launched the jazz age, making Harlem a must-visit spot for New York’s chic high society. It inspired dozens of other shows, including Miller and Lyles’ Runnin’ Wildthat introduced the iconic ‘20s dance, the Charleston. Harlem nightspots like the Cotton Club thrived in its wake, introducing major jazz figures including Duke Ellington.The Broadway production of Shuffle Along closed on 15 July 1922 after 504 performances. It had the eleventh longest run of any Broadway musical up to that time including Show Boat, which ran 572 performances. It became one of the top-ten draws on Broadway for the entire decade.

Feature image by Alex Avalos

The post 10 little-known facts about Sissle and Blake’s Shuffle Along appeared first on OUPblog.

December 7, 2020

Why is religion suddenly declining?

As the 21st century began, religion was spreading rapidly. The collapse of communism had left a psychological vacuum that was being filled with resurgent religion, fundamentalism was a rising political force in the United States, and the 9/11 attacks drew attention to the power of militant Islam. There were claims of a global resurgence of religion.

An analysis of religious trends from 1981 to 2007 in 49 countries containing 60% of the world’s population did not find a global resurgence of religion—most high-income countries were becoming less religious—however, it did show that in 33 of the 49 countries studied, people had become more religious (Norris and Inglehart, 2011). But since 2007, things have changed with surprising speed. From 2007 to 2020, an overwhelming majority (43 out of 49) of these same countries became less religious. This decline in belief is strongest in high-income countries but it is evident across most of the world (Inglehart, 2021).

The most dramatic shift away from religion took place among the American public. For years, the United States had been the key case demonstrating that economic modernization need not produce secularization. But recently, the American public has been moving away from religion along with virtually all other high-income countries—in fact, religiosity has been declining more rapidly in the US than in most other countries.

Several forces are driving this trend but the most powerful one is the waning grip of a set of beliefs closely linked with the imperative of maintaining high birth rates. For many centuries, most societies assigned women the role of producing as many children as possible and discouraged divorce, abortion, homosexuality, contraception, and any other sexual behavior not linked with reproduction. Virtually all major world religions encouraged high fertility because it was necessary, in the world of high infant mortality and low life expectancy that prevailed until recently, for the average woman to produce five to eight children in order to simply replace the population. Religions that didn’t emphasize these norms gradually disappeared.

A growing number of countries have now attained high life expectancies and drastically reduced infant mortality rates, making these traditional cultural norms no longer necessary. This process didn’t happen overnight. The major world religions had presented pro-fertility norms as absolute moral rules and firmly resisted change. People only slowly give up the familiar beliefs and societal roles they have known since childhood, concerning gender and sexual behavior. But when a society reaches a sufficiently high level of economic and physical security, younger generations grow up taking that security for granted and the norms around fertility recede. Ideas, practices, and laws concerning gender equality, divorce, abortion, and homosexuality are now changing rapidly. Almost all high-income societies have recently reached a tipping point where the balance shifts from pro-fertility norms being dominant, to individual-choice norms being dominant.

Several other factors help explain the waning of religion. In the United States, politics explains part of the decline. Since the 1990s, the Republican Party has sought to win support by adopting conservative Christian positions on same sex marriage, abortion, and other cultural issues. But this appeal to religious voters has had the corollary effect of pushing other voters, especially young liberal ones, away from religion. The uncritical embrace of President Donald Trump by conservative evangelical leaders has accelerated this trend. And the Roman Catholic Church has lost adherents because of its own crises. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey found that an overwhelming majority US adults were aware of recent reports of sexual abuse by Catholic priests, and most of them believed that the abuses were “ongoing problems that are still happening.” Accordingly, many US Catholics said that they have scaled back attendance at mass in response to these reports.

Although some religious conservatives warn that the retreat from faith will lead to a collapse of social cohesion and public morality, the evidence doesn’t support this claim. Surprising as it may seem, countries that are less religious actually tend to be less corrupt and have lower murder rates than religious ones.

Each year, Transparency International publishes a Corruption Perception Index that ranks public-sector corruption in 180 countries and territories. Is corruption less widespread in religious countries than less religious ones? The answer is an unequivocal “no”—in fact, religious countries actually tend to be more corrupt than secular ones.

This pattern also applies to other crimes, such as murder. Surprising as it may seem, the murder rate is more than ten times as high in the most religious countries as it is in the least religious countries. Some relatively poor countries have low murder rates, but overall, prosperous countries that provide their residents with material and legal security are much safer than poor countries. It’s not that religiosity causes corruption and murder, but that both crime and religiosity tend to be high in poor countries.

In early agrarian societies, when most people lived just above the survival level, religion may have been the most effective way to maintain order and cohesion. But as traditional religiosity declines, an equally strong set of moral norms seems to be emerging to fill the void. Survey evidence from countries containing over 90% of the world’s population indicates that in highly secure and secular countries, people are giving increasingly high priority to self-expression and free choice, with a growing emphasis on human rights, tolerance of outsiders, environmental protection, gender equality, and freedom of speech.

As societies develop from agrarian to industrial to knowledge-based, growing existential security tends to reduce the importance of religion in people’s lives and people become less obedient to traditional religious leaders and institutions. That trend seems likely to continue, but pandemics such as the current one reduce peoples’ sense of existential security. If the pandemic were to endure for decades, or lead to an enduring Great Depression, the theory underlying this article implies that the cultural changes of recent decades would reverse themselves.

That’s conceivable but it would run counter to the trend toward growing prosperity and rising life expectancy that has been spreading throughout the world for the past 500 years. This trend rarely reverses itself for long because it is driven by technological innovation which, once it emerges, usually persists and spreads. If that happens, the long-term outlook is for public morality to be less determined by traditional religions, and increasingly shaped by the culture of growing acceptance of outgroups, gender equality, and environmentalism that has been emerging in recent decades.

Feature image by Aaron Burden

The post Why is religion suddenly declining? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers