Oxford University Press's Blog, page 126

November 15, 2020

Playing the opposite of what Brahms wrote

What might we learn from an oddity concerning the first movement of Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 1 in G, op. 78, that has led many violin-piano duos either to ignore Brahms’s tempo markings or actually play the opposite of what he wrote?

Brahms’s score is explicit. The basic tempo is Vivace ma non troppo (lively, but not overly so). Near the middle of this mostly lyrical movement, when the movement’s most agitated music begins, Brahms wrote più sostenuto (more sustained). Then, leading into the opening theme’s return, Brahms wrote poco a poco—Tempo I (gradually return to the first tempo). In other words, play the lyrical opening in a relatively lively manner, play the climactic music and what follows more slowly, then speed up and return to the lively tempo.

We know that Brahms himself played the sonata this way. The Hungarian violin virtuoso Jenö Hübay (1858–1937) told his pupil Joseph Szigeti (1892–1973) that when he performed the sonata with Brahms, Brahms insisted on those tempo changes. Szigeti, in turn, included this anecdote in his memoir, A Violinist’s Notebook.

It makes one wonder. Why did Brahms discuss these tempos with Hübay? Why did Hübay tell Szigeti? And why, over half a century later, did Szigeti include this anecdote in his memoir? There’s a common-sense answer to these questions. When Hübay and Brahms first rehearsed the sonata, Hübay probably played the tempos the way most violinists and pianists were already playing the movement. They’d play the softer, lyrical sections in a more relaxed manner than Vivace ma non troppo, speed up when the music gets louder and more agitated, and slow down when returning to the return to lyricism at the Tempo I. After all, it’s intuitive to play lyrical music in a relaxed manner and more agitated music in a faster tempo—especially in the nineteenth century, when performers varied tempos much more than is done nowadays. But that’s clearly not what Brahms requested. Why?

Delving into the sonata and events happening around the time it was composed can lead us toward a likely answer. Even when the piece was brand new, listeners recognized that the middle of the slow movement is a funeral march, and that the finale’s rondo theme is closely based on two of Brahms’s Lieder. The poems in those Lieder are about rain drops—a common Romantic-poetic metaphor for tears. In “Regenlied” (“Rain Song,” op. 59 no. 3), raindrops evoke memories of youth. In “Nachklang” (“Echo,” op. 59 no. 4), the narrator assures us that when the sun shines after the rain, the grass will be greener, but he will continue to weep. People wondered. Was the sonata a memorial to someone close to Brahms—perhaps Felix Schumann, the talented youngest son of Robert and Clara Schumann, and Brahms’s godson? Felix had just died at age 24, following a six-year struggle with tuberculosis.

Brahms almost never communicated about his compositional intentions. He didn’t dedicate the piece to Felix’s memory (or even, less specifically, “to the memory of a young artist”). He didn’t write “funeral march” in the score (as composers as different as Beethoven and Chopin had done in sonatas of theirs). But he did send a brief score and letter to his lifelong friend Clara shortly before Felix died—while Brahms was completing the sonata. Sending Clara the slow movement’s opening, he wrote “it will say to you, perhaps more clearly than I otherwise could, how heartfelt my thoughts are concerning you and Felix.” For over a century, this letter remained undiscovered in an archive.

Do those words tell us why Brahms requested tempos in the first movement that have seemed unintuitive to so many performers? When the sonata begins, are the luscious melodies and textures evocations of a youthful creative soul whose death is commemorated in the slow movement’s funeral march, and who is remembered amid tears as the finale opens? That seems likely, because the funeral march’s opening motive uses the exact same pitches as the first movement’s most rapturous theme. It seems likely, because the finale opens with the violin playing the very same notes it played as the sonata began—but now all alone at first, unsupported by rich piano chords. Perhaps the agitated music in the middle of the first movement is not music excited about the beginning’s lyrical themes (an interpretation that might suggest a faster tempo), but rather portrays the violent destruction wrought upon the youthful artist by a terrible illness?

Interpreters of this music—performers, listeners, and analysts—who consider such details in the music, in its allusions, in its historical circumstances, and in Brahms’s evocative notation will develop their own interpretations.

Feature image by Valentino Funghi

The post Playing the opposite of what Brahms wrote appeared first on OUPblog.

November 13, 2020

A conversation on music and autism (part two)

In the first part of Music and Autism: Speaking for Ourselves author Michael Bakan’s interview with his Chapter 7 musician co-author Graeme Gibson (who is on the spectrum) and Graeme’s parents, the renowned science fiction novelist William (Bill) Gibson and autism researcher Dr Deborah Gibson, things left off with Bill telling Michael about how being Graeme’s dad had influenced his creation of “unnervingly human” AI (Artificial Intelligence) characters in his novels. Next in the conversation, Michael invited Bill to talk about the very significant influence of music generally—and specific musicians in particular—on his creative process as a writer. We pick up the conversation from that point.

Michael (M): That’s really interesting [to learn how being Graeme’s father inspired your “humanization” of AI characters in your books], Bill, and leads me to another question, specifically having to do with how music has influenced you as a writer.

Bill (B): Well, I’m not at all musical, and neither is Deb, but we have both in our lives been very, very intensely moved by music. I’m just kind of a folk and pop guy (Deb’s tastes are broader; she has a library of operas), but yes, music has influenced me greatly as a writer. When I was starting to write, around age twelve or thirteen, I loved science fiction and read a great whack of it. But then, you know, puberty arrived, and I thought it was like a childhood thing and put it on the side. But when I began to think about writing again, I was dismayed by how uncool, to my mind, the science fiction that was being produced in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s, was. I thought it had become like Nashville country: formulaic, nothing there that I would be interested in. And what I wanted science fiction to be, as I thought, was more like Dylan going electric.

So I was more consciously inspired by Steely Dan’s lyrics than I was by any of the science fiction that I could see being written when I first started to write. Then I found there were other people around trying for the same effect, other writers whose science fiction looked more like Steely Dan’s lyrics than the rest of the science fiction that was written… And when I started going to London on publishing-related business, the best science fiction store in town was right across the street from the studios where David Bowie recorded his first three or four albums. And the people in the stores—they would have loved David Bowie anyways—but they particularly loved him because he’d always been one of their very best customers, since before he started recording. And they could see that he was taking what he was buying from them, taking it home, fully digesting it, and bringing it back into the recording studio. So that’s an art of sound thing in its own way. I love it that I know that story and that I know it’s true.

M: So do you feel that there’s some similar kind of process, specifically relative to music, that went on in your own writing?

B: No, it was more like an ambition that there could be an analogy, and I knew that some of the most progressive science fiction being written when I was fourteen years old was being written by people who were already being inspired by the roots of the music of what we think of as the ‘60s. But their influence had faded away by the time I came back in my mid-twenties after getting a BA in English literature, and I was looking at contemporary science fiction and going, “Oh, man. This is not happening for me.” So my ambition was to, you know, make that analogy happen again… I remember listening to Bruce Springsteen’s “Nebraska” and imagining what it would be like if it were a science fiction novel.

M: Wow.

B: That was what I would do. I would listen to a piece of music and it would really move me and be unlike anything quite like what I’d heard before. And I’d think, “Yeah, but what would that be like if it were a piece of science fiction? What would that look like as a piece of science fiction?” And that would be a starting point for something.

Bill with Graeme reading. Photo by Dr Deborah Gibson, used with permission.

Bill with Graeme reading. Photo by Dr Deborah Gibson, used with permission.M: Fascinating! Over to you, Deborah. What essential lessons has being Graeme’s mom taught you, and how have those lessons impacted your life?

D: So one of the things I learned, I guess had to learn, was that we had to create our own experience and ways to get Graeme his best life, and ways for us to get through it without going completely berserk [laughter]. It was hard because there wasn’t the level of support that there is now, and we were, like, very impoverished really—well, not really—but we were very low income earners at the time. So it was difficult, but I managed, and I realized that I had to get another persona in order to find out what I wanted to know about Graeme, because every test that he had, everything that I pushed for, they would just give me the “mom” version.

And I knew there was another version that went amongst the professionals, that would use medical vocabulary and such. I needed to learn it, and I did learn it (that knowledge base eventually became the foundation for my PhD dissertation research, in fact, which was a case study on Graeme’s language acquisition) and I was able, therefore, to push quite far into getting information about Graeme that made me then feel like I had the information to take to, say, the school board or medical world, and to ask for things that were not there.

You know, Graeme was the first child with autism that that was integrated into the Vancouver School Board, to not be in a segregated class. And so I think just having a child who was “different” pushed me in a way that I was unwillingly pushed, but that nonetheless was an important maturation. I had a very cute baby, and one that was enchantingly different from others I knew. And it was delightful! Graeme’s babyhood was not all difficulties. He was so funny, and unique—very strong in what he liked and what he didn’t like. And what he liked were dots on the wall. He liked to find these microscopic dots and do this thing with sound, and touching them very slowly, and then screaming. He would play with things for hours and hours, but he hated primary colors, and all the toys were in primary colors. It was just really interesting, and often comical, and, I don’t know, there were wonderful things about being Graeme’s mother, wonderful things that I definitely wouldn’t have experienced if he had been a more “typical” child.

M: Let’s bring it all back full circle to Graeme. Graeme, what are three lessons you would like readers to take away from this interview, especially relative to your experiences as a member of your family?

G: First, I’ll always say that you have to keep in mind that all people on the spectrum are different from each other. People on the spectrum have different needs. You have to find a way to accommodate their needs, to meet them on their own terms. You have to know who they are individually. So that in itself is more the challenge, but once that’s established, in my family we’ve gone much beyond that, so it’s pretty continuous in the way that information flows from me to Mom and Dad by email or in person. I’ve gotten very good at asking for what I need, and at articulating what I want, and what I don’t want.

The second thing I’ll talk about, which is actually related, is the constant communication. That’s what keeps us together in my family, even though we don’t spend very much time actually together anymore, except when we travel, like the trip to England last year.

Third would probably be mutual support, like how my parents have found me teachers and other people who have helped me to develop my skills, like my music teacher Randy Raine-Reusch, and when I was young, my music therapist Johanne Brodeur. That does count in the overall picture.

M: Those are great. Thanks, Graeme. Deborah? Bill? Anything to add along related lines?

D: I think I have to keep being reminded that I have to respect Graeme’s boundaries about what is really hard for him. Because there are lots of things that I think would be maybe fun to do, and Graeme finds them difficult in ways that I haven’t expected. Or I’ll suggest something that’s spontaneous, and that doesn’t work for Graeme. He likes to plan ahead. So I have to keep being reminded, even though it’s been 43 years, that there are big differences between what I think is easy and what Graeme finds easy. In lots of ways it can be, in my opinion, something small that Graeme sticks on, but for him it’s huge, so that’s something that I’ve had to adjust to.

M: Yes, that’s so important. Bill?

B. I’ll just amplify what Deb said, that respecting who Graeme is has been really, really essential, and like an ongoing project for sure. It’s not something one perfectly masters.

D: Yeah, like having this interview happen today, and getting Graeme’s cooperation, was something we really had to work on together. You sitting here for all this time—almost an hour and a half—mainly listening to us talk? I thank you for that, Graeme.

G: Mm-hmm…

M: And I thank all of you. This has been really enlightening, and inspiring!

Feature image by Syd Wachs.

The post A conversation on music and autism (part two) appeared first on OUPblog.

November 12, 2020

Teaching peace in a time of violence

In September 2020, President Trump signed an order calling for a commission on “patriotic education,” in response to what he considered anti-American sentiments seeping into school curricula around the United States. He accused teachers of teaching a “twisted web of lies” by including lessons from the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which examines American history through the lens of the African slave trade. His remarks were denounced by the American Federation of Teachers and the Association of History Teachers, and raised important questions about the roles of teachers in American society. Should teachers teach content that avoids controversy? Is it a teacher’s duty to teach love for country, even when that country has a legacy of violence?

These questions have been at the core of my own work as an educator and scholar since 1999, when I began teaching high school English, but became even more important after September 11, 2001. In the months and years that followed the 9/11 attacks, I observed the ways that patriotism was used as a cudgel against dissent by people like myself, Americans frightened by the popular embrace of racism, Islamophobia, and militarism across the country. When my students expressed these sentiments in class, I did not know how to intervene or respond, and wondered if it was even my job to do so. Yet, as the War on Terror became more deadly, and the country devolved into culture wars over immigration and gay marriage, my students increasingly looked to me for explanations about the violence both at home and abroad. As their teacher, I wanted to have answers, but was coming up short.

Things changed in 2005, when I attended a two-week training for K-12 teachers on nonviolence and social change, at the Ahimsa Center for Nonviolence at the California State Polytechnic University in Pomona. Along with a cohort of 30 other educators, I learned about nonviolence as a philosophy, as a political strategy, and as a force for reconciliation in diverse contexts. At the institute, I learned that the decade of 2000-2010 had been designated by the UN General Assembly as the “International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World.” The UN Resolution references the Constitution of UNESCO, which stated that “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed.” Learning about the International Decade empowered me to think of myself as a defender of peace; as a constructor of peace in the minds of my students and colleagues whom I saw every day at school.

Inspired by my experience in 2005, I became a facilitator at subsequent institutes, allowing me to work closely with over 200 K-12 teachers hailing from all over the United States, from Hawaii to Maine, Washington to Florida. Through this work, I recognized that teachers are indeed essential to cultivating a culture of peace and nonviolence; they are embedded in schools and communities and witness how various forms of violence manifest in the lives of their students. Some seek nonviolence because they see anti-gay bullying and anti-immigrant bashing in their schools; others are concerned by the way violence is emphasized in curriculum.

One of the goals of the institute is to help teachers, called “Ahimsa Fellows,” learn how to build nonviolent relationships with students and colleagues, drawing on nonviolent principles and practices. In my role as a facilitator, I worked with the teachers as they created standards-based lesson plans exploring nonviolence; within these 400 lesson plans created over the last 15 years, teachers explored peaceful conflict resolution for 1st graders, nonviolent marches in the United States for 7th grade history, the monetary impact of boycotts in 9th grade Algebra, and environmental justice for 12th graders. Throughout the new curricula, teachers draw on a wide range of nonviolent leaders, such as Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, César Chávez, and Nelson Mandela, as well as a range of concepts, like forgiveness and ahimsa (Sanskrit for nonviolence), to help students understand how they might choose nonviolence in their everyday lives.

The French philosopher Jean-Marie Muller, in Non-violence in Education (2002), wrote that “Teachers must have the initial and in-service training needed to enable them to question and re-adjust their educational choices in the light of the philosophy of non-violence.” Recently, 18 teachers trained at the Ahimsa Center wrote about their experiences learning about nonviolence for a book, Teachers Teaching Nonviolence. In their narratives, the teachers describe the forms of violence that compelled them to go beyond the delivery of academic content, and illuminate how the lens of nonviolence helped them make educational choices galvanized by a belief that teachers can be agents of nonviolent social change. Their stories reveal that teachers must be willing to talk about the violence of the past, and the injustices of the present, in order to provide an education that prepares them to create a better future. Perhaps, in doing so, they demonstrate a love for country grounded less in patriotism, and more so in peace and mutual understanding.

References

Crowley, M. (2020, September 17). Trump Calls for ‘Patriotic Education’ to Defend American History From the Left. New York Times.Muller, J. M. (2002). Non-violence in education. Paris: Unesco.United Nations General Assembly. (2006). Resolution 61/45: International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World, 2001–2010.Featured image by Jeffrey HamiltonThe post Teaching peace in a time of violence appeared first on OUPblog.

November 11, 2020

The dubious importance of cultivating facial hair: the word “bizarre”

Students learn to begin their papers with an introduction and end with a conclusion. The puny body is left to grow between those two boundary marks. I have never seen much use in this rigid scheme. However, today I have no choice but to follow this pattern and will write a long introduction. Most etymological dictionaries appear in installments. The problem is that by the time the work reaches the last letter, the author knows so much more than at the beginning that numerous earlier etymologies must be rewritten. The great Walter W. Skeat added a list of corrections to the first edition of his English dictionary, and in at least one case (at bless) wrote that his explanation was completely wrong (!), because soon after the appearance of the installment with the letter B, he had read an article by Henry Sweet and accepted his hypothesis. Whether Sweet guessed well is another matter. Sigmund Feist, the author of a monumental Gothic etymological dictionary, suggested that his work needed revision every twenty years. He was right.

I am saying all this because on October 26, 2011, I posted an essay on the origin of the word bigot. If at that time I had known all I now know about the history of bizarre, I would have written it somewhat differently, and part of my reasoning would have been more convincing. A popular but probably wrong etymology of bigot refers to a mustachioed man (fortunately, I did not share it), and, according to an equally popular and equally wrong etymology of bizarre, the root of this adjective should be sought in Basque bizar “beard.” As regards bigot, for a long time, we were advised to compare it with Spanish hombre de bigote, literally, “moustached man,” that is, “man of spirit.” (Note that the Basque word is bizar; the form bizzarra, cited in many sources, is this noun with an article.)

Obviously, a very courageous person. (Image by Nonsap Visuals)

Obviously, a very courageous person. (Image by Nonsap Visuals)Hair and masculinity are perennial twins. Numerous examples occur in the Bible (remember Samson and the fact that some Old Testament men “were sent to Jericho,” to wait for their beards to grow to respectable lengths). The Icelandic word skeggi “bearded” (related to English shaggy) became a proper name. The great god Thor was also depicted with a gigantic beard. All that is true. Yet bigot hardly refers to moustache, and bizarre has, it appears, nothing to do with beards. Let it be remembered that both bigot and bizarre are words “of unknown etymology,” or, to put it differently, there is no consensus on their origin. Several very old etymologies of bizarre did not go beyond fanciful guesses: from a combination of two Latin words, from Arabic, and from an ethnic name. Even in the middle of the nineteenth century, few philologists remembered those conjectures. Yet, in principle, those “pre-modern” scholars searched where we still do.

One more thing should be said before my “proem” (or preamble, if you prefer) comes to an end. With few exceptions, most etymologists are experts in only one area. To be sure, there were a few universal linguists, such as Jacob Grimm, Antoine Meillet, and James A. H. Murray, but they are exceptions. Yet a language historian working with the vocabulary of English constantly runs into words of Romance origin and is expected to say something about them. Even the Germanic field is vast, and someone who feels perfectly comfortable in Old English (like the already mentioned Henry Sweet) probably knew and knows less about Old High German, Old Norse, and so forth. The god of etymology is in the details, and Romance etymology is as broad as Germanic (which is my field). In Romance, I depend on the opinions of French, Spanish, Italian, and other experts, and, if I risk saying something about bizarre, it is only because I have probably read all there is on this word and because my associations with Germanic may be of some use to specialists in Romance. I’ll be grateful for their opinions and suggestions. End of the introduction.

Bizarre! (Image by Philippe Wagneur, Natural History Museum of Geneva)

Bizarre! (Image by Philippe Wagneur, Natural History Museum of Geneva)English bizarre was borrowed from French in the seventeenth century. Almost identical forms have been recorded all over the Romance-speaking world, but the senses of the cognates match partially. The French adjective bizarre (known in books since 1533) means “peculiar, eccentric, strange,” as it does in English, though earlier, it also meant “brave.” Italian bizzarro (with voiced zz, as in English adze) yields the same meanings (“strange, odd, whimsical, eccentric”). By contrast, Spanish and Portuguese bizarro (in Spanish texts, since 1569) means “gallant, courageous, grand, splendid.” As regards meaning, only the Spanish adjective matches its Basque putative source (in Basque, the connection between beard and courage needs no proof). Therefore, the conclusion that the source of the Romance word should be searched in Basque, makes perfect sense. But, to use James A. H. Murray’s favorite phrase, this conclusion is at odds with chronology.

In Italy, the word was known to Dante. It meant “fiery, furious, impetuous” and referred to the Florentine spirit. Around the same time, its lookalike occurred as the proper name (nickname?) Pizzarro. It happens with some regularity that a certain word emerges first as a proper name and only then as a regular noun or adjective. Such words tend to have a strong slang-y tinge, because nicknames were often, if not regularly, humorous, derogatory, and obscene. (Therefore, nicknames are our main window into medieval slang.) The verb sbizzarrire (approximately, “to push, thrust”) occurred around the same time. The chronological gap is astounding: in Italy, the word was known at least two and a half centuries before it reached Spanish, Portuguese, and French. For this reason, the great Spanish etymologist Joan Corominas concluded that the homeland of the Romance adjective was Italy, from which it spread to other languages.

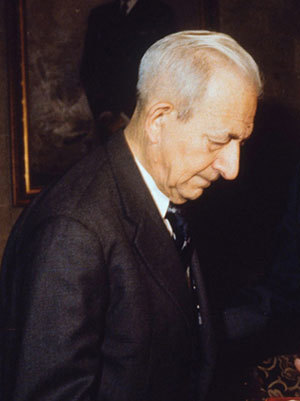

Joan Corominas, a famous Spanish lexicographer. (Image by Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de la Presidència)

Joan Corominas, a famous Spanish lexicographer. (Image by Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de la Presidència)If Corominas was right, the Basque etymology falls to the ground, and indeed, at present, no one derives bizarre from Basque. Another casualty of this etymology is the suffix –arro: if it is not from Basque, how did it come into being? The multitude of partly incompatible senses is also odd, whatever the origin of the adjective. If the initial meaning was “fiery, impetuous, unrestrained,” “brave” sounds natural, but “peculiar, eccentric, whimsical”? In French, bizarre crossed the paths of bigarré, “variegated; motley,” another adjective of unknown origin (also slang?). Dante’s word sounds like an epithet typical of a warlike, aggressive attitude, and “brave” is close. But the derivation of Modern Italian “strange, eccentric” from “fiery, impetuous” needs special pleading.

Next week, I’ll briefly examine some other etymologies of this intractable word and later offer my own suggestion, though, as already mentioned, I realize that only a very foolhardy Germanic etymologist will dare walk where the best Romance specialists tread (they have to!) but stumble.

Feature image: Farinata degli Uberti, fresco by Andrea del Castagno

The post The dubious importance of cultivating facial hair: the word “bizarre” appeared first on OUPblog.

November 10, 2020

A conversation on music and autism (part one)

Earlier this year, Music and Autism: Speaking for Ourselves author Michael B. Bakan sat down for a Zoom conversation with his Chapter 7 co-author, the Vancouver-based multi-instrumentalist and music instrument collector Graeme Gibson, and with Graeme’s parents, autism researcher Dr. Deborah Gibson and bestselling science fiction author William (Bill) Gibson. Their four-way conversation covered a range of topics, from how raising a child on the spectrum shaped Bill’s writing of iconic novels like Neuromancer, to how Deborah’s advocacy on Graeme’s behalf helped to spearhead the movement toward inclusive public education in Vancouver, to how Graeme’s abiding fascination with musical instruments—combined with his prodigious research and memory—enabled him to identify virtually every instrument in the expansive world instrument collection of London’s Horniman Museum. Here is part one of the interview; part two will be published in a separate OUPblog post.

Michael (M): Hello, Graeme, Deborah, and Bill! Thank you so much for doing this interview. I’ve really been looking forward to it.

Graeme, a question for you for starters: You have a collection of, what, more than 400 musical instruments? And these instruments are from all over the world, and you can actually play most of them, some very well, which is really impressive. How did your interest in musical instruments start?

Bill (B): Wasn’t there a little electric keyboard you used to play when you were really little?

Graeme (G): Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. There was, and that’s also what propelled me to be able to learn where the notes are laid out on the keyboard.

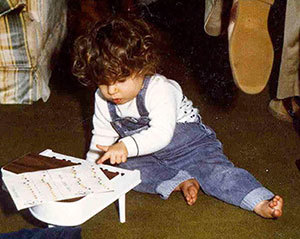

Deborah (D): Actually, it wasn’t electric—Michael, I think I sent you a picture of Graeme playing it when he was a toddler—it was this tuneless little wooden toy piano that we got him for his second Christmas (he was one year old), and he was so mesmerized by it. From the time he was a baby, Graeme was just so interested in sound, and he showed a real affinity for instruments of all kinds. He liked Santa’s jingle bells more than any other present. He was just drawn to music and sound, and when we had records he would insist on Bill playing them over and over again. At that point he was signing rather than speaking, and he would make a very insistent gesture, spinning his finger around in circles like a record spinning on a turntable, to say to Bill, ‘Play it again, play it again!’

Graeme with toy piano. Photo by Dr Deborah Gibson, used with permission.

Graeme with toy piano. Photo by Dr Deborah Gibson, used with permission.G: Then later, when I was a teenager, I did have an electronic keyboard—a Casio SK1, and I would play that for many hours every day.

D: And then, all of a sudden, you asked for a balalaika!

G: Yeah, yeah. In terms of instruments from other world cultures, my first major acquisition was a Russian balalaika.

B: What I remember is that Graeme walked up to me one day and said, “I want a balalaika.” [Graeme laughs] And I only barely knew what a balalaika was: it’s triangular, it’s a Russian, like… something. How on earth do you think you ever decided to get a balalaika?

G: I might have heard it somewhere, maybe the radio or something. I sort of had an idea of what it was and the way that it was played. It’s just the way my ears pick it up. I wish I could explain that, but unfortunately, I can’t translate that software here, so… And later, especially after I started studying with my music teacher Randy Raine-Reusch, who owns thousands of instruments from around the world, he introduced me to many other instruments as well—especially stringed instruments, which are my specialty—and my collection grew and grew. Now I have an online instrument museum where people can visit my collection.

M: Right, and I seem to recall that you enjoy visiting “live” musical instrument museums as well, right, Graeme?

G: Yes! Like last year, when Mom and Dad and I went to London.

D: There was a wonderful museum of ethnic musical instruments.

G: Yeah! The Horniman Museum in, uh… I forget where exactly it is, but, uh…

D: It wasn’t close.

G: No, it was far, but well worth it.

D: And Graeme knew the name of every single instrument without even looking at the label.

G: Yes.

D: He was the most incredible museum guide, and he would describe the slight discrepancies between that version of the instrument and then the one that came from twenty miles further south. It was a real eye opener for me on how much Graeme knows about music, about instruments, about all things music-related.

M: Yes, his knowledge—of instruments, the Indian raga system, you name it—is immense. When I assign our chapter in the Music and Autism book to my students, I’ll say to them, ‘Check out how much this guy knows. You’re Ph.D. ethnomusicology students; you should know as much as he does!’ [laughter]

D: And we have to thank Randy [Raine-Reusch] for that. He’s just been an extraordinary teacher for Graeme. And as far back as when he was a baby, it wasn’t just music and instruments that interested Graeme. It was sounds of all kinds. When the fridge went on and off…

G: Usually around 9 p.m. or so. [Deborah and Bill laugh] Yeah, yeah. There would always be that time, sometime in the evening, when it was very routine. You’d hear the click, and then you’d hear the fridge cycles. [Deborah laughs]

D: I gotta say, I never, ever paid attention to our fridge before in that way. [laughter]

Graeme with some of his instruments. Photo by Michael O’Shea, used with permission.

Graeme with some of his instruments. Photo by Michael O’Shea, used with permission.M: A question for you now, Bill. At the same time that you were being a stay-at-home dad to Graeme, in the late 1970s/early 1980s, you were also working on your first novel, Neuromancer, which would of course bring you considerable fame—not to mention revolutionize the literature of science fiction, inspire the iconic Matrix film series, and (along with some of your earlier short stories) even change the English language with your coining of the term “cyberspace” and such. I have to think that being a first-time dad—and a dad to Graeme in particular—would have influenced your writing during that time. True?

B: I think that being Graeme’s dad made me think more actively about consciousness and perception than I would have otherwise, that is, had I not had that experience, because I had the example of Graeme totally perceiving everything, but perceiving it often in a slightly other way. And I think, particularly for someone that writes the sort of fiction I write, that’s a hugely useful example to have every day, as opposed to, you know, watching everyone else doing what everyone else is doing with the information they’re receiving, although that’s essential too.

Also, on a practical level, as it became more evident that Graeme wasn’t “just any baby,” it sort of upped the ante on what I was doing. And I also was in a situation where if I was going to be doing anything other than co-parenting Graeme, the perfect thing to do would be trying to become a writer, because you do it from home, literally any time of day, you know, whenever Graeme was asleep, for instance, which is when I did a lot of my writing. So, in some ways it was sort of a natural fit. Yeah, I can’t think of anything else I could have done. And I was lucky, because I was able to make a living at being a freelance writer of fiction, even though, looking back on it, there’s almost no one else I ever knew who tried to do that who was able to do it; they all wound up having day jobs. And I have yet to have one, I’m happy to say.

And there’s one other thing I’ve wondered about, too, that seems relevant to your question. Something that’s been consistent through my work are characters who are AIs, they’re Artificial Intelligences, but are unnervingly human in their presentation, and seemingly in their consciousness. As far as I know they’re much more totally human than we have any right to expect Artificial Intelligences in the future to be, at least so far. So, something that happens, I know from watching reader feedback, is that readers become invested in the AI’s humanity, but then are occasionally henceforth startled by moments of cognitive dissonance where they realize that it’s human but it’s not quite standardly human. And that’s the result of me, if it were music playing it a certain way, to get that effect of deliberately going slightly off key to remind the reader that the character’s not “standard issue” human. And, you know, that may be something subsequent to being Graeme’s dad.

Feature image by Karim Manjra

The post A conversation on music and autism (part one) appeared first on OUPblog.

November 9, 2020

What can the Conservatives’ 2019 election win tell us about their current leadership?

It’s an old truism that a week is a long time in politics, which would probably make 11 months an absolute age during even the most halcyon times. So, reflecting on the lessons to be drawn from the victory of the Conservative Party in the 2019 general election does rather feel like a job for ancient historians rather than political scientists. But there remains much that we can learn from the recent past, and many elements of why we argue the Conservatives won back in December can explain much of their response to the COVID-19 crisis and the current grandstanding over Brexit.

A Brexit election?In 2019, all of the major political parties had assumed Brexit would reshape the basis of party support. The problem for Labour and the Lib Dems (who had hoped to hoover up disenchanted Tory Remainers in any number of constituencies), was that the reshaping only really occurred in one direction. Whilst a not insignificant number of voters were more Remain than Conservative, or more Leave than Labour, the Conservatives gained the vast majority of those voters enticed by a prime minister promising to “Get Brexit Done.” By contrast, the Remain vote was inefficiently split between the Lib Dems, the Greens, the nationalist parties, and Labour.

Indeed, Tory insiders have suggested that the true turning point in the general election happened before campaigning began when Johnson concluded a Withdrawal Agreement with the EU-27. This agreement, to quote campaign chief Isaac Levido, “was a real game changer, [it] unified a number of fringes in our voter coalition that we needed to bring together.”

Which brings us to the present predicament that the Johnson government finds itself in over the internal market bill. The 2019 victory was built on the back of having an “oven ready” Brexit deal. Any kind of wrangling that shows this deal to be, at best, parboiled risks pulling apart the shaky coalition that delivered the Tories victory. This is before considering that the Brexit deal trumpeted during the election was only functionally different to a range of deals negotiated by Theresa May and her team due to the very fact that it effectively agreed to locate a customs border between Britain and Northern Ireland.

The red wall crumblesThe main drama of election night itself was the crumbling of Labour’s so-called “red wall,” the aftermath of which is still being discussed and analysed in minute detail. One reading of this is that Labour were undone by the simple fact that they presented a jumbled platform and were presided over by a historically unpopular leader. But that is only a part of the story.

That the election was about Corbyn and Brexit, there is little doubt—but it was also about underlying issues surrounding culture and national identity for which Brexit acted as a filter. And the Conservatives, in managing to pitch the election as a Brexit election—in a way that they had failed to in 2017—appealed to specific voters within this new electoral landscape. Many of whom resided in “red wall” seats and would be considered, classic “old” Labour voters. This, again, gives some indication as to why, over a not uneventful summer, we saw little of the Conservative leader. But, perhaps, why Johnson did pitch up (both figuratively and literally) with his opinion on whether Land of Hope and Glory should be sung at the Last Night of the Proms.

Must the Conservatives win?These (seemingly) fundamental shifts in electoral geography, led some to see the election result itself as tantamount to Labour’s last rites. But politics can, and has, changed very quickly. Just as 2017 was the election in which everything went wrong for the Tories, 2019 might well have been the year everything went right. But it leaves them with a fragile coalition of support, from the Tory shires to the traditionally Labour North East. Many members of this coalition are voters for whom the Tories might end up being a one-time fling—“a temporary and transactional swing to the Conservatives, rather than a conversion to conservatism.”

Moreover, a common critique of Johnson is that he is a better campaigner than he is statesman. A “break glass in case of emergency” leader that has a broad, if superficial, appeal. When journalist Tom McTague asked Johnson why the 2019 campaign was so dull he responded, “I’m not the artist; I’m merely the subject—it is for you to apply the rich chiaroscuro to your canvas.” And it is this seeming lack of guiding vision that we argue was one of the great strengths of the campaign—it could mean all things to all people.

However, seeing oneself in this somewhat vague way is indicative of something deeper. Of a basic mindset that values common sense over compulsion and “guidance on social contact instead of legislation.” It is an ideology that makes one slow to lockdown a country, and causes one to bristle when asked if the police will be utilised to enforce restrictions.

A “rich chiaroscuro”, then, may be effective for a campaign—but less so in a genuine crisis. In 2019, the Conservatives were dealt a good hand and played it well. In 2020 they—along with the rest us—have been dealt one of the lousiest hands in recent memory. How they have played, and continue to play it will define the Johnson premiership and the fortunes of the Conservative Party for years to come. As we conclude in our chapter, “whether it can cope with the challenges presented by government remains, however, to be seen.”

Featured image by Deniz Fuchidzhiev

The post What can the Conservatives’ 2019 election win tell us about their current leadership? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 7, 2020

Five famous doctors in literature

Doctors have appeared in fiction throughout history. From Dr Faustus, written in the sixteenth century, to more recent film adaptations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the familiarity of these characters will be profitably read and watched by both experienced and future doctors who want to reflect on the human condition often so ably described by the established men and women of letters. Here, I have selected five famous doctors in literature who each exemplify a step in the progress from superstition to scientific interest to the high technology depictions of medical professionals that we are familiar with today.

Dr FaustusThe famous Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe was written at the end of the sixteenth century. Dr Faustus was a dramatization of the Faust legend about a man with prodigious learning in all spheres of knowledge (including medicine and a belief in immortality) who, due to his hubris and pact with the devil Mephistopheles, undergoes his own tragic demise and achieves little of what he set out to do. The themes of sin, redemption, and superstition have been the subject of much debate in the subsequent centuries and is perhaps a reminder to us all that we are not omnipotent. This was a time when superstition and religious beliefs played a large part in the healing process with medicine in a primitive state of development compared to today with little scientific credentials. Spiritual healers were the norm. Bloodletting was a common treatment for many ailments and physicians had few effective medicines at their disposal, often using potions with lead or mercury which today we know are harmful. Surgery was primitive with no anaesthesia or antisepsis measures and primarily confined to amputations.

Dr Charles BovaryMadame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, published in 1856, introduces us to the mediocre Dr Charles Bovary, an average, struggling country doctor in France and the husband of Emma, who wants a more ambitious man of higher standing. She ends up having an affair with Rodolphe Boulanger, a local wealthy philanderer. The book was praised by Henry James amongst others as the perfect work of fiction and has been filmed several times with a notable 1991 version directed by Claude Chabrol, the famous French film director. The nineteenth-century era was one of the affable gentleman physician, with still little in his armamentarium against disease. Medicine in big cities was often more lucrative than in the provinces and was more likely to be of cutting edge especially in the teaching hospitals. Several advances in this century include Laennec and the invention of the stethoscope, the development of anaesthetics and blood transfusions. Infectious diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis were common.

Dr Tertius LydgateIn Middlemarch, published in the UK in 1871 and set in the Midlands, George Elliott introduces us to Dr Tertius Lydgate, the new doctor in town with new ideas about medical health. Dr Lydgate promoted prescribing based on scientific evidence at a time when doctors were still poorly regulated and probably did more harm than good with their treatments. Nevertheless, the late Victorian era would have seen advances in anaesthesia, improved infection rates following surgery—thanks to Joseph Lister, a pioneer in antiseptic surgery—and the beginnings of specialization in medicine with the opening of specialist and teaching hospitals.

Dr Andrew MansonIn 1937, A. J. Cronin published The Citadel, a semi-autobiographical novel about the protagonist Dr Andrew Manson who comes to work in a mining community in Wales and is almost crushed by the powers that be for his idealism and ethics. He is forced to resign rather than work unethically and is unfairly referred to the regulators General Medical Council. It is said that the book helped promote the principles of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) which was founded in 1948. By now, thanks to Willhelm Röntgen’s discovery of x-rays in 1895, radiology was a part of the doctor’s armamentarium and mass screening for tuberculosis using chest x-rays was common, although there was still no drug cure for this condition. This only became available in the 1950s.

Dr Bernard RieuxI finally turn to the famous work by the French writer Albert Camus, The Plague, which was published in 1947. It has become popular reading in the current COVID-19 pandemic. The character Dr Bernard Rieux treats the first plague victim in town and warns the leaders to take action to prevent spread of the disease. The progress of the plague hitting the town is described and it is not surprising that the novel has proven of great interest to all of us today in current times. It is interesting to remember that the book was meant to be an allegory and was referring to French resistance to the Nazi invasion of France during WW2 (the so-called plague). Camus was awarded the Nobel prize in Literature in 1957. The story was filmed in 1992. Plus ca change mais c’est la meme chose!

Featured image by Kuma Kum

The post Five famous doctors in literature appeared first on OUPblog.

November 6, 2020

Reimagining our music classes for Zoom

Let’s start our Zoom session with a warm up for your musical imagination:

Hear a single note in your mind, played on a violin without vibratoNow hear the violinist add vibratoThe note begins to crescendoNow it is fortissimoNow hear the note played sfzpp and held with a fermataThe note slides upward in a glissando and fades away into silence

All of us who are devoted to music education are facing new challenges due to the pandemic, and while we are lucky and grateful to have extraordinary technology at our disposal, it is undeniably frustrating to be isolated from each other, to deal with inadequate sound quality, poor connections, and time delays. We cannot actually play chamber music in a satisfying way on Zoom or on any other digital platform with players in different locations. We need to temporarily but urgently reinvent how we teach and connect with students.

To deal with this, musicians everywhere are coming up with creative responses, structuring courses in new ways, and devising thoughtful and compelling blends of performance issues, history, score study, watching videos, and listening to historical performances. For me personally, this crisis has given a new purpose to the synthesis of theater games and music exercises that I have been using to teach for over 40 years.

For music students, the word technique means physical dexterity, virtuosity on an instrument, and excellent intonation. For drama students, the word technique is not only about good diction and fluid body movement, but more importantly it is about the availability of emotion and memory. For many years, drama teachers have used theater games to help students access their emotions in order to really feel rather than merely indicate feelings. They also use theater games to access memories as a way to fuel their imaginations, so that they can bring their own experiences to interpretive challenges.

In the 1980s, I studied and practiced theater games—and I have continued to do so—in order to reimagine them as exercises and games for musicians. I started my explorations with writings of Konstantin Stanislavsky, Lee Strasberg, Jerzy Grotowski, and also by following the ideas of their students. More recently, I added the important work of Viola Spolin to my arsenal.

Here is one of my theater-inspired games that you can vary to fit your Zoom needs:

Take a line from a play or make up a line of textSay the line in different ways, with different emotions, giving it various subtextsPick one line reading that seems convincingWrite the words on paper, adding rhythmic notation that reflects the readingAdd dynamics and articulation markings that fit the emotion of the readingGive the line, now notated in detail, to someone to read who did not hear your readingDoes the notation convey everything you hoped it would?Does the reading based on your notation sound as you had expected?Now add musical pitches to the words and remove the words. Now you have a musical phrase based on that line reading. Does it capture the feelings you had wanted?The “musical imagination workshops” I have been leading for the last 40 years have served to augment and enhance traditional approaches to teaching performance and composition at conservatories, university music departments, and community workshops throughout the US, starting with Juilliard (where I developed the concept in the 1980s in my weekly seminar).

Due to the pandemic and our temporary but essential reliance on technology to replace in-person classes, the approach of using theater-inspired imagination games offers a compelling solution to a serious problem. Many of the exercises I have developed do not require instruments, as they explore the ability to hear sounds in the mind (The Mind’s Ear), to imagine solo instrumental timbres and orchestral colors, to compose in various ways using sounds heard only in the mind (including rain, footsteps, sirens, glass shattering, etc.).

In this exercise, we take ordinary sounds and imagine a narrative structure:

Sound of nail being hammered into a wall in a steady loud rhythmSound of a siren in the distance getting louderThe nail hammering gets faster and lighterThe siren continues to get louderThe hammering gets faster but now louderThe siren is very loud and the hammering is now slow and loudGLASS BREAKSSilenceThe siren fades away into the distanceSelect a set of sounds and construct a scenario, as above.

These games and exercises work on Zoom without compromise. In addition to imagination games, there are improvisations that can be done without instruments, as well as solo instrumental improvisations that each class member can try, while the rest of the class listens and reacts. There is no need to be an experienced improviser for these games, and no particular musical vocabulary is required because the exercises focus on accessing and expressing emotion and on narrative strategies. One might improvise a given exercise in any musical style or in no particular musical style. Technique, for these games, is about the ability to communicate genuine feeling, to let the imagination take over.

For a while, perhaps for half of every Zoom session, we can forget our instruments and repertoire and concentrate on exploring our musical imaginations and accessing our emotions.

In my experience, students benefit enormously from these exercises and games, and they become more resourceful, creative, and independent artists.

Feature image by Gabriel Benois

The post Reimagining our music classes for Zoom appeared first on OUPblog.

November 5, 2020

Countering college student stress: a Q&A

There has been growing interest in college student mental health, particularly regarding stress and anxiety levels. This seems particularly heightened due to circumstances associated with the pandemic and the societal re-awakening stimulated by the Black Lives Matter movement. Given the long-understood connection between music and stress, we asked three music therapy scholars to discuss reasons for underlying rising student stress levels and share musical methods for promoting college student mental health.

Kimberly Sena Moore: The saying goes that “college is the best time of your life,” so what’s causing stress and anxiety in college students?

Carolyn Moore: Broadly, the college experience involves many ongoing systemic issues that can cause or exacerbate stress and anxiety. For example, the cost of college is rapidly rising and students are having to make decisions about how to pay for college, decisions that can affect their financial stability (and by extension, quality of life) for years to come. At many universities, students from historically marginalized or underrepresented groups feel unsupported or unsafe, which impact stress and anxiety levels.

Lindsey Wilhelm: Yes, these type of life transitions can impact stress and anxiety. Many college students have moved away from home, are developing new social relationships and networks, and need to work while also attending classes. Additionally, many students are experiencing stress related to dealing with personal and situational factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, including new or changing formats of course delivery. Even if exciting, these new and challenging situations can also lead to high levels of stress and anxiety.

KSM: Why does there seem to be an increase in college student stress and anxiety?

Jennifer Fiore: Students today are dealing with different stressors than students in previous years. For instance, almost all my students work at least part-time, and there are several who work full-time to support themselves while also going to college full-time. Technology has also increased the amount of information available, which brings positives and negatives. For example, this can result in additional readings and projects being included in coursework that were not an option years ago. Beyond school, students and their families are facing additional stressors related to racial tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals experience stress differently, and this can be impacted by previous life experiences, barriers to opportunities, finances, available social supports, existing diagnoses, and current use of coping skills.

CM: In my experience students seem more willing to talk about mental health concerns and seek help. Additionally, schools are developing and making available resources for addressing mental health. I think we’re seeing the increase because these issues are more out in the open and thus, are easier to recognize, examine, and analyze. I also think that in looking at the average age of college students, they’ve been exposed to unprecedented levels of trauma (e.g. gun violence). This is a topic that comes up when I talk to my students about stress and anxiety—they recognize the impact of trauma on their overall mental health.

KSM: What are some strategies students can incorporate to help them manage their stress and anxiety?

LW: While there’s no “one size fits all” answer, effective self-care behaviors include self-awareness (e.g., through personal reflection or mindfulness practices) and physical wellness (e.g., physical activity, balanced diet, sufficient sleep). Based on my interactions with students, strategies such as scheduling ten to fifteen minutes to do something they enjoy or using a mindfulness timer as a reminder to take two minutes to breathe are quick and simple ways to help decrease feelings of stress and anxiety. Especially now, students may find they need to modify their self-care practices as what worked in the past may not be as helpful to deal with current stressors. Opportunities for in-person social connections may be more challenging to safely navigate but are still possible, especially through the use of technology. Many universities are also providing additional resources and options to support students during this challenging situation.

CM: In general, I think doing things you enjoy doing, rather than things you think you should be doing, is helpful. And, I recognize that not all students may have the resources or access to professional therapy, but I recommend it for students.

JF: What can be hard to remember when stressed, there are protective factors, many of which have already been mentioned. I also suggest strategies specific for college students, such as scheduling time for studying, turning off technology while studying and at night, shifting from a reactive to creative mindset to manage tasks (such as planning out when to work on tasks and breaking them into smaller parts), and establishing a consistent sleep pattern. Specific to our current situation, maintaining social connections, engaging in physical exercise, and taking breaks from the news and social media if/when you find they are increasing your stress or anxiety response. It’s also important to reach out to someone to get the help you need if things become too much to manage on your own. Finally, mental health literacy is another concept that needs to be addressed to help college students. Universities need to help students be aware of strategies and services that are available to support them.

KSM: Are there any music-based strategies that might help? Even for non-musicians?

JF: Music-based strategies exist for both musicians and non-musicians. Keep in mind the music itself, and remember to practice your strategies frequently. Research indicates music does not have to be familiar to be relaxing. Be selective when choosing music and do not automatically use everything labeled “relaxing.” For example, the tempo (or pace) of the music should be similar to your walking speed, the rhythm predictable, and the dynamics (or loudness) consistent. In addition, people can pair other relaxation techniques like deep breathing, meditation, and visualization with the music.

LW: No matter your musical aptitude, listening to music is a coping strategy that can help with managing stress and anxiety. You may find that what you want to listen to changes from day to day and that is fine. I recommend students pick music strategically—do you want to increase your energy and overall mood, calm an overactive mind, regulate breathing… Each of these outcomes may call for a different type of music. For myself, I have created a playlist with a general theme of “things are going to be alright” that I have listened to daily for the past several months. While the theme has remained the same, the playlist has grown and is a source of comfort.

CM: One strategy is making playlists on Spotify to support different types of moods or themes. My students like selecting the songs and having easy access to their playlists. Plus, Spotify has tons of user-generated and platform-generated playlists, so anyone who wants to explore what’s out there can do so quickly.

KSM: What are future directions for examining the impact of music (or music therapy) on student stress?

CM: One thing that would be interesting to explore is how and if music students’ personal uses of music for stress relief change as they move through the curriculum. Do students still feel that listening to or creating music is important for wellness when they are engaged in it for school-related purposes nearly all day, every day? Do students create boundaries, intentionally or unintentionally, between “personal” music, music for classes/school, and music for clinical work? Finally, does music still hold the same ability to reduce stress when it is also a source of (school-related) stress?

LW: Future research could consider the experience of stress by music students in other degree programs, but perhaps more meaningful for the music therapy profession would be to explore how music therapy students and educators are incorporating engagement with music and/or in music therapy as a way to manage student stress. Additionally, incorporating music strategies for stress management into the curriculum can both benefit music therapy students and help inform how music and music therapy can be used to manage stress in clinical settings.

JF: I agree—teaching stress management techniques early in the curriculum could give students tools to help manage their own stress, as well as equip them for their future clinical work. Other future steps include determining the most important combinations of musical elements that help decrease stress, as well as examining recommended dosage for using music-based strategies for wellness and stress reduction.

The post Countering college student stress: a Q&A appeared first on OUPblog.

November 4, 2020

Etymology gleanings for October 2020

My usual thanks to those who wrote letters and commented on the posts.

Spelling ReformThe topic is not worthy of detailed comments here, because everything that can be said for and against changing English spelling has been said many times, but some contributors to the discussion do not know the relevant literature and reinvent the same wheel. Below, I’ll repeat a few points without the slightest hope of impressing my opponents.

English spelling has changed many times not only through its long history but even since the Elizabethan period, and not only in America. However, we are seldom aware of this fact.Spelling has been reformed in other countries, and there is no reason why it cannot be reformed in the English-speaking world (despite its size and lack of homogeneity).No spelling reflects the pronunciation of every speaker of every dialect. If the Reform succeeds, English spelling will remain basically the same, but some of the most glaring absurdities will be removed.Returning to Shakespeare: since his days, the pronunciation of English has changed rather radically (as evidenced by his rhymes and puns). By reforming spelling, we do not erase (“cancel”) history: we follow it! No one pronounces ch– in chthonic. I agree. So why keep it? Because it gives us an insight into Greek? Do we know anyone who has mastered Classical Greek through the spelling of Modern English? Whose history do we honor ~ honour when we spell colour and color: Latin or French?God is in the details. Everything depends on what should be changed and what is better left alone. Superfluous consonants are easier to purge than some counterintuitive vowels.We hear again and again that it is too late to reform English spelling. Perhaps so. Then millions of hours and heaps of money will be wasted, as before, on teaching native speakers of English and foreigners countless tricks. Isn’t it strange that our public, ready to support the most radical changes in the life of society, is so staunchly against the one change that will benefit all? Isn’t there such a thing as a balance of plus(s)ses and minuses? Which chthonic deity are we ready to worship? See a picture of Hades in the header.(This is an answer to a reader’s challenge.) I do have a list of words that, in my opinion, would gain immensely if they were spelled differently, but this is not the place to publicize it because the Spelling Society has been working for a long time on such lists and has several proposals to offer. The Society’s website is open to all who are interested in the subject.Odds and ends The Twelve. (Image by Prof Hans Schneider)The dozens

The Twelve. (Image by Prof Hans Schneider)The dozensJudging by a comment on my most recent essay (Baker’s dozen, 28 October 2020), the interplay of twelve and thirteen occurred not only in the bakers’ and the printers’ business (see what is said in the comment about medieval Venice), so that the idea of the Devil’s (wrong) dozen must have occurred to many. Perhaps the importance of the number twelve in our life and folklore contributed to the popularity of such wrong dozens.

Sheep and mutton Choose your prize and punishment. (Image by Keven Law)

Choose your prize and punishment. (Image by Keven Law)It is better to be hanged for a sheep than for a lamb. The proverb has a medieval ring, but it was first recorded in 1678. The context is obvious: since the punishment is going to be the same (hanging), it pays off to commit a greater crime and enjoy its benefits while you are alive.

Mutton dressed as lamb is a witticism recorded only at the beginning of the nineteenth century. As is the case with most proverbs and idioms, its origin is unknown, but it must probably have been coined in aristocratic circles, because it taunts women past their prime dressing and behaving like those who are much younger. In a peasant environment, the language was less metaphoric. My database contains a note from 1853. In Kidderminster, Worcestershire (the West Midlands, UK), they said: “Forty, save one, the age of Roden’s colt,” an ironic putdown aimed at middle-aged women. Roden and his colt are mysterious characters and will, most probably, remain such, but the existence of some story (now lost) can be taken for granted. (Does anyone still remember the phrase a woman of Balzac’s age? That age is thirty. At one time, the phrase was immensely popular in Russia, but I am not sure that it has ever been used outside Russia and France.)

The only authentic image of Roden’s colt.As dead as a rat

The only authentic image of Roden’s colt.As dead as a ratSometimes, a clue to a mysterious idiom may be found in another phrase containing the same word. For example, the simile as dead as a rat is known. How could a rat become the epitome of mortality? I am aware of a single suggestion. A correspondent to Notes and Queries (in 1868) cited the synonymous and equally obscure phrase as weak as a rat and wondered whether there is any “connection with the rat-hunting propensities of some of our greatest nobility in the days of George III” (who reigned from 1760 to 1820). But perhaps (this is my guess) the simile is an echo of the phrase to rhyme rats to death, an allusion to the custom of exorcising rats, popular in the days of Shakespeare, who alluded to it in As You Like it. In Act III, scene 2, lines 187-89, Rosalind says: “I was so be-rhimed since Pythagoras’ time, that I was an Irish rat, which I can hardly remember.” Annotated editions of Shakespeare’s play explain the superstition. The allusion may be to an old Irish belief that witches who assume the shape of rats can be “rhymed to death.” Of course, I have no proof that the idiom as dead as a rat has anything to do with that old belief, but etymologists are beggars and pick up their stuff where they find it (this was also Molière’s principle).

This is Auguste Rodin, not the semi-mythological Roden. Honoré de Balzac is immortal. (Image by Beyond My Ken)Children’s games

This is Auguste Rodin, not the semi-mythological Roden. Honoré de Balzac is immortal. (Image by Beyond My Ken)Children’s gamesThe origin of eeny-meeny and its world-wide distribution have been an object of long and not wholly unsuccessful research. A special article is also devoted to it in my Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. As could be expected, our records are late. In any case, there is no reason to insist that the center of the dissemination of this counting out gibberish was Greece. The situation here is the same as with Spelling Reform and with all problems: before voicing an opinion, one should become aware of the state of the art, because in scholarship, facts, rather than opinions, matter.

As cool as a cucumberTwo comments on this idiom suggested that cucumbers are really cool, either because they lie on the ground or because they contain very much water. Perhaps so!

Angels on horsebackFinally, I am always pleased when something I write evokes pleasant memories, as happened when in the most recent post I mentioned Winchester College.

Feature image by Aviad Bublil

The post Etymology gleanings for October 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers