Oxford University Press's Blog, page 129

October 21, 2020

International Open Access Week 2020: Get to know the team

To celebrate International Open Access Week 2020, we spoke to some of the Open Access (OA) Publishing team at OUP to find out all about this dynamic area of publishing. Publishing Director for Open Access Rhodri Jackson, Senior Publishers Rhiannon Meaden, Lucy Oates, and Nikul Patel, Publisher James Neenan, and Assistant Publisher Jude Roberts reveal all.

Why work in OA publishing?Rhodri Jackson: OA has been a consistent theme running through my whole career. My first role in OUP’s journals team was as an Editorial Assistant, and I was lucky to enough to work on our new OA activities. In 2006, one of our biggest journals, Nucleic Acids Research, had just “flipped” to OA, and we had just started experimenting with “hybrid” OA. I was completely new to journals publishing and I was immediately interested in OA—it was novel, appealing, a place for innovation, simple in conception but complicated in application, and engendered highly varying and emotive responses. I’ve worked in OA ever since, and it continues to be all those things, making it a really interesting area in which to work.

Jude Roberts: I switched careers about 18 months ago from lecturing in FE and HE to academic publishing, working in the Journals Production department. I am currently on a year-long secondment in the OA Editorial team. As an academic researcher, I had some sense of the transformation to research funding and accessibility that may come from OA publishing. The chance to be involved in facilitating that is incredibly exciting.

Rhiannon Meaden: What I particularly enjoy about working in OA is the pace of change we have been experiencing. Opening up research, removing barriers, and facilitating greater discussion within the research community are all important aims of OA publishing, and make it an area I’m proud to contribute to. There have been so many challenges over the last almost 10 years I’ve been in this industry, but this is what makes it such an interesting and exciting field to work in.

Nikul Patel: My attraction towards working in OA is that scholarly communications for the last few decades have been going through perhaps the largest change since the advent of the internet. OA does not just represent a business model, but actually it’s also a socio-political movement that seeks to change the paradigm of how and to whom scholarship and research is available, especially when it is funded publicly.

Lucy Oates: I’ve been working in OA publishing at OUP for almost seven years—prior to that I studied French and Italian, and taught English as a foreign language. When applying for my first role in OA publishing, it was clear that open access was a developing area of academic publishing, and the opportunity to work in a varied role which supported the wide dissemination of research appealed to me.

James Neenan: My background is as an academic—until recently I was a palaeontologist at the University of Oxford working on dinosaur and marine reptile fossils. However, I wanted to move into OA publishing because I’m passionate about the free exchange of knowledge between researchers and the rest of world. Academic literature is for everyone and should not be locked away behind a pay wall where only the privileged can access it. In short, dinosaurs are extinct, but OA publishing is evolving and thriving!

What’s it like working in OA publishing?Rhiannon: A key part of my role is on the growth and development of our new Oxford Open series, which we launched earlier in the year, so I spend a lot of time running market research, holding discussions with external subject experts and working with our editors.

There are constantly new questions being asked of journals, and of publishers, which we work to answer, so there is a huge amount of problem solving and creative thinking needed to try to resolve some of the wider issues the industry faces.

Lucy: I moved from our Oxford headquarters to our New York office earlier this year. OA is growing, not just at OUP but across scholarly communications, and as researchers and authors move towards publishing open access at different rates and with different priorities, part of my role is to support OUP to ensure we can respond to the changing landscape, which makes it a really exciting area to work in!

As part of this I work with our sales teams to deliver Read and Publish agreements for our institutional customers—a sales model which has been developed to meet the changing needs of our customers. These agreements facilitate OA publishing for authors as the OA charges are combined with the institution’s journal subscription.

James: The main part of my role is to assist in the creation of new OA journals, which I feel is a real privilege. The OA world is growing fast, especially considering that lots of funding bodies (like the UKRI) are starting to require researchers funded by them to publish in gold OA journals. This means the demand for gold OA is exploding, and we at OUP need to keep up.

How can open research transform the world?Rhodri: It’s stating the obvious somewhat to say that the world faces many challenges—from global issues such as the coronavirus pandemic and the climate emergency, to the local and personal crises engendered by disease, ill-health, poverty, and war. Open research will not fix these problems alone, but making rigorous, well-reviewed research as widely available as possible is a logical step and will allow scientists, researchers, academics, politicians, policy-makers, and the wider public access to all the good work already being done in these areas, enabling them to use and build upon that work.

Nikul: Essentially the more people that have access to and can use research, the larger the pool of people that can help us examine and tackle some of the world’s most pressing issues, such as climate change or gender inequality.

Rhiannon: Furthering science requires us to build on the knowledge, theories, and evidence built up before us—standing on the shoulders of giants. If we cannot do this, then we cannot continue to expand our knowledge, or make new discoveries to benefit us and the world we live in. Opening up research facilitates a greater sharing—and importantly re-use—of research. It allows new knowledge to be disseminated more quickly and more easily across a wider community. In order to learn and understand more quickly we need research to be more open, accessible, and usable.

James: In this world of “fake news” and misinformation, free access to the primary literature is worth its weight in gold. Furthermore, researchers in less-affluent countries cannot always access the literature they need for their own work unless it is OA. I can attest to this first hand, as I was once a post-doc in South Africa and I had huge problems accessing the scientific literature I needed.

Jude: Making research freely available to anyone who wants to access it is a crucial step in achieving equity of opportunity and is absolutely transformative in terms of enabling collaboration and future research worldwide. Taken to its logical conclusion, open access publishing is nothing short of a complete revolution in the funding and distribution of academic research.

What’s next for OA publishing?Rhodri: We can confidently predict that more and more research will be published OA in the next few years. We can expect the focus on open research considered more broadly (open data, open peer review, open methods, etc.) to accelerate further.

The impact of the pandemic will be interesting to see. The pandemic has the potential to greatly accelerate moves to OA, as it has shone a light on the need for open access to research. In some ways though it has the potential to be a brake on change, simply because all the other disruption caused by the pandemic places so many other constraints on the time and priorities of organizations. Taken as a whole though, I think the pandemic is likely to lead to faster moves towards OA.

Lucy: In the next couple of years, in the US in particular, I think we will see more changes in open access policy from funders—just this year we have already seen US funders such as Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation update their OA policies.

I also expect we will see increased interest from institutions in combining OA publishing for their researchers and subscriptions to journals, known as Read and Publish or transformative agreements. Globally, we predict that more and more authors will choose to publish their research outputs under the OA model, continuing the trend that we have seen over recent years. Similarly, I’d expect an increasing number of journals to adopt policies on data availability and open data, therefore helping researchers to not only access the article, but also the underlying data.

Nikul: I think in the near future we’ll see more journals being able to sustainably transition towards a fully OA model and will also see even more funding bodies create more stringent OA policies as a condition of their funding grants.

Rhiannon: OA has rapidly become an important and significant business model within publishing, and I would expect the further development of open research initiatives over the next couple of years. We are at an exciting phase in research publishing with so many different experiments in the OA and open research world, many of which OUP is participating in. OA publishing has always had a culture of innovation, so I would expect this to continue.

Find out more about our OA team’s work and the future of OA publishing at OUP in our first blog post of International Open Access Week 2020: What can a university press do to drive open access?

The post International Open Access Week 2020: Get to know the team appeared first on OUPblog.

Harlots all over the place

This is a continuation of the previous post (October 14, 2020), an ultimate dig at harlots and their likes. The story I quoted a week ago connected harlot with the name of William the Conqueror’s mother. It goes back to the 1570s, and, as the OED noted in its Second Edition, such a conjecture was possible because at that time, no one had access to the full history of the word in question. Harlot turned up in English texts in the thirteenth century, acquired its present-day sense (“prostitute”) about two hundred years later, and ousted all the previous ones. Those “previous ones” are worthy of recording: “vagabond, rascal, low fellow,” “itinerant jester” (do you remember the story of Chaucer’s summoner, a gentil harlot and a kynde. The progression of senses makes it clear that an attempt to ascribe to the etymon of harlot the meaning “bad woman” should not even be considered. It may seem odd that in the beginning harlot referred to both men and women. Yet we are not dealing with a unique case. I would like to refer our readers to the post for February 7, 2007 (“The flourish of strumpets”). In it, I mentioned the history of girl (the word once designated a child of either sex) and of strumpet: in Huntingdonshire (a non-metropolitan district in Cambridgeshire, England), strumpet means “a fat, hearty child.” If strumpet traces to some word denoting a vessel or a stump (see the post), a connection with “an unwieldy object” as starting point can be made out (but whence “whore, slut”?) and if “loafer” is the beginning of the story, then why “fat child”? It would be tempting to reconstruct a string from “stump” to “fat child” to “fat woman” (women and children is a familiar phrase; the two often go together in all kinds of reports) and, finally, to “loose woman,” the last step in what specialists in historical semantics call the deterioration of meaning, a process especially common in the words denoting women (whore, for instance, goes back to a word for “darling”). Returning to harlot, we can state as fact that the word, when it emerged, could have positive connotations but was more often applied to disreputable persons (ready to sell their questionable services?), to men rather than women; that later the feature “disreputable” won over, and the term of abuse stuck to women. Like Harlequin, harlot had close, almost identical cognates in Romance: Old French harlot ~ herlot “playful (!) young fellow; knave, vagabond”; Italian arlotto ”vagabond, beggar; fool; glutton”; Old Portuguese arlotar “to go about begging” (thus, the emphasis was on roaming people without a definite occupation), and Old Spanish arlote ~ alrote “lazy.” The attested Middle English forms were the same as in Old French. Old dictionaries had no clue to the etymology of harlot. George Hickes, an influential grammarian, active in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, traced harlot to whore–let. Samuel Johnson connected the word with the name of King William’s mother. For a long time, especially popular was the idea that the English word goes back to Welsh herlawd “stripling” or herlodes “hoyden,” from her “to push; challenge” and llawd “lad.” Not only Noah Webster thought so but also Hensleigh Wedgwood, Walter W. Skeat’s predecessor and one-time rival. The Welsh words were borrowed from English, and, in any case, what kind of derivation is harlot “push-lad”? The other suggested etymons of harlot (possibly there are others that escaped my attention) are Latin helluo “glutton,” Latin ardelio or ardalio “loafer” (a word known only from some glosses), presumably, from Greek árdalos “dirty” (thus, from ardliotto to ardlotto and arlotto), English hire (suggested by an eminent member of the Philological Society as late as 1862), and Old High German harl, a side form of karl “man.” Harl ~ karl turned up in a work by C. A. F. Mahn. In one of my posts on harlequin, I mentioned that Mahn had written a book on that word. This was a mistake. In summer, the library at the University of Minnesota where I teach was closed. It is now open, and I have access to my carrel; a copy of the book I needed stands in it. Mahn, as I immediately discovered, wrote a book titled Etymologische Untersuchungen (“Studies in Etymology”); Harlequin and harlot are indeed discussed in it. I have trouble with Mahn’s harl ~ karl. Old Germanic names beginning with Hari– (referring to “army” of course) did vary in spelling with Chari, but karl never had a variant with h-. Walter W. Skeat, still our foremost authority on the origin of English words, also tried to connect harlot with karl, but the first consonant ruins his hypothesis. More about him below. The original OED refrained from guesswork, and so did The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. But since the days of the OED, great progress has been made in this area, especially thanks to Leo Spitzer’s 1944 paper and our knowledge of the origin of Harlequin. It is probable (even highly probable) that Harlequin and harlot have the same Germanic root and that the original harlot was either a member of the crowd known as the Wild Hunt or someone who sponged off troops. This idea occurred to Ernest Weekley. He glossed harlot as originally meaning “camp follower.” The rest is less clear, because we do not know whether the suffix in harlot is –ot or –lot. And it is indeed a suffix. Weekley’s attempt to connect –lot with German Lotter-, “as in Lotterbube, synonymous with harlot in its earliest sense, cognate with Anglo-Saxon [Old English] loddere ‘beggar, wastrel’” does not inspire confidence: the form harlot(t)er never existed. If the suffix is –ot, then harlot acquired it in France. Such was Spitzer’s opinion. Like Harlequin, harlot, after many peregrinations, returned to English from French. Adding a French suffix to a Germanic word occurred many times. Strumpet offers a good parallel: the root strump– is Germanic, while the suffix –et is French. One can imagine that a Romance suffix turned a Germanic “whore” into a classy “prostitute.” Skeat, in the last full edition of his etymological dictionary, cited the Dutch suffix –lot. It is therefore possible that the root was har– “army” and that it originally referred to a soldier of the lowest rank or someone who followed the troops for whatever reasons. In any case, the syllable –ot ~ -lot was a diminutive suffix. In Middle English, the word giglot had some currency. It, too, denoted a prostitute and some sort of jester. Gig and jig (sound-imitative? Sound symbolic?) aroused associations with mean pursuits. Apparently, –lot (from Dutch?) meant nothing to English speakers, and giglot became giglet, as though some gig or giggler with a diminutive suffix, as in kinglet or rivulet. I am inclined to think that harlot is har– + –lot, rather than harl– + –ot. Any medieval army was followed by hordes of parasites: prostitutes, disreputable vendors, entertainers, and so forth. They were called harlots, giglots, and what not. I don’t think anyone has ever compared harlot and giglot. Yet this comparison may be of some use. As a postscript, I may mention harridan “a belligerent old woman; a termagant,” an item of seventeenth-century cant, presumably an alteration of French haridelle “old jade.” This derivation is possible, though haridelle is a word of unknown origin. Are we dealing with another piece of army slang, another despicable creature (an old nag, an old hag), whose name contains a Germanic root (har-) and a Romance diminutive suffix, whatever the middle part –id– may mean? This is where my Wild Hunt ends, at least for a while. Its aftermath will depend on the readers’ questions and comments. Feature image by Vince Veras The post Harlots all over the place appeared first on OUPblog. A Huntingdonshire strumpet, “a fat, hearty child.” (Image by Alaina Browne)

A Huntingdonshire strumpet, “a fat, hearty child.” (Image by Alaina Browne) The Whore of Babylon, the proto-harlot. (Image by Henri-Marcel Magne)

The Whore of Babylon, the proto-harlot. (Image by Henri-Marcel Magne)

October 20, 2020

The poetics and politics of rap music in the UK

As we approach the deadline for the UK to leave the European Union, a number of political debates persist in media discourse: the legality of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s actions regarding (amongst other things) the Northern Irish Border, the increasing call for Scottish independence, and the role of government in handling the novel coronavirus pandemic via the National Health Service. With Harry and Megan leaving their royal duties, even the monarchy is under scrutiny. Debates around the history of the British Empire and its role in profiting from the slave trade has also been in recent news, with Edward Colston’s statue falling in my hometown of Bristol. The Black Lives Matter movement have prompted discussion on identity, discrimination, anti-racism, inclusion, and representation in society for Black British and other minority ethnic groups.

From all this, one can conclude that the Kingdom is far from united. While media outlets such as the BBC and newspapers tell a particular story of the situation, I have found that there is a missing voice in these discourses which shed an important light on these contexts.

The British rapper, or MC, I argue is just an important if not more important voice speaking out and talking back to more mainstream political narratives. Sometimes it’s done with humour, in the case of Brexit parodies like “F**k Brexit” and “Auf Wiedersehen Mate,” or with urgency such as in Akala’s “Maangamizi” (on the African Holocaust). Some of these MCs have received less attention than their stylistic cousins working with grime and drill music, but nevertheless have important things to say on nationalism, history, and belonging.

With regards to Scotland, their 2014 referendum for independence was accompanied by a flowering of creativity, and hip-hop was no exception. Songs from Stanley Odd like “Marriage Counselling” and “Son I Voted Yes” were important in the soundtrack to the “Yes Scotland” campaign (which eventually lost 45% to 55%).

Listening to a song like Dave’s “Question Time” from 2017 at the start of Theresa May’s government really sums up concerns with adequate care and wages for what we now call “key workers” in our society. He raps,

“All my life I know my mum’s been working

In and out of nursing, struggling, hurting

I just find it f**ked that the government is struggling

To care for a person that cares for a person.”

As ever, rap at its most politically conscious becomes a mouthpiece for the voiceless, the marginal, those who contribute most productively in society but are rarely heard. Chuck D famously said that rap was “CNN for Black people,” and many of the rappers in the UK (e.g. Lowkey, Shay D, Akala, Stanley Odd, Reveal) extend this point more globally. Songs about Grenfell Tower (such as “Ghosts of Grenfell”) are concerned with the tragedy itself, as well as the tower as metaphor for the wider failings of the British government and its adherence to neoliberal principles.

And what about songs about coronavirus? Yes, they exist too. Lady Leshurr who has a popular series of viral videos under the “Queen’s Speech” banner, released “Quarantine Speech” in April of this year, encouraging people to wash their hands while draping a sparkly union jack flag mask around her neck.

Investigating UK rap in the twenty-first century shows a multifaceted group of voices that reflect the politics of the postcolonial condition of the UK. Whether it’s addressing national or regional issues, global hip-hop and its penchant for talking back to (or even better, rapping back to) dominant discourses can provide a wider framework for performers.

Listen to the playlist below for a sampling of tracks (and click here for a full Brithop YouTube playlist):

Feature image: Abandoned Train Tunnel by Candice Seplow

The post The poetics and politics of rap music in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

October 19, 2020

The socially distanced library: staying connected in a pandemic

The concept of a socially distanced library would be considered the ultimate antithesis of the modern-day library. The past two decades have witnessed the evolution of the library from a mostly traditional space of quiet study and research into a bustling collaborative, social space and technology center. The library has been described as a third place, the home constituting the first place, work as the second place, and then the library—where in addition to research and study, the user can do virtually most things including relax, eat in a library cafe, and even exercise. Public libraries have provided many community benefits, including health and government services, as well as loans of non-traditional items such as tools and equipment.

In 2020, the entire world was thrown into a state of confoundment, as the novel coronavirus ground routine day-to-day activities to a screeching halt. Many organizations, including academic institutions in the United States, made a hasty retreat into an exclusively virtual online environment. Libraries followed suit and most were firmly shut, as was the corresponding access to library stacks, study, and collaborative spaces. This was also the case with public libraries; even the Library of Congress shuttered its physical facilities to the public. How did libraries initially respond to this massive disruption and how would connections to library users be maintained in this new and unprecedented context?

First, with regards to library collections, many libraries have increasingly migrated to online collections over the past two decades. Electronic publications provide a flexibility and ubiquity of access, which is highly attractive to researchers on the move. A persistent challenge, however, has been how to invite traditional print users into the digital world of publishing. The pandemic forced a moment of reckoning; few could have predicted the speed by which electronic publications would be adopted by erstwhile print-only users. Quite suddenly, users married to the print version of materials could no longer access them because of quarantine protocols, shipping delays, and a host of other factors tied to the pandemic. This is not to say that libraries have not made accommodations for delivery and loan of books. While pandemic protocols have impeded the volume and speed of distribution, users have for the first time tapped into take-out services such as curbside delivery of books and the use of remote book lockers. Duke University Libraries’ take-out service enables patrons to request library materials and pick them up with minimal contact—a video promoting the service went viral at the start of the Fall 2020 semester. Library scan and deliver services have also increased exponentially, with users requesting more document delivery by email (and within copyright guidelines). Libraries with means will also ship books to users at their residential addresses. One public library in Virginia even deployed drone delivery of books through a collaboration with Google spin-off, Wing, a drone delivery service.

Once the pandemic hit, research consultations with librarians went completely virtual. Library patrons adapted to the ease of tapping into the library’s knowledge machinery without having to make a physical trip to the library. In some instances, Zoom consultations (similar to telemedicine with doctors) were made available to library users, in addition to already existing text, email, chat, chatbots, and phone services. Library trainings and other modes of instruction also morphed from in person into online or hybrid formats. The Goodson Law Library at Duke Law school promoted a virtual asynchronous legal research bootcamp for students in the summer. In effect, the closure of the law school building did not preclude continuous learning and instruction. Research and scholarly services support also continue in the remote context, for example Duke Law researchers are able to tap into virtual online empirical and data support services. These types of virtual initiatives have become the new normal.

Perhaps, the most challenging change for the more social library users are the severe restrictions on space usage and the ensuing inability to fully engage and collaborate in person, pre-pandemic fashion. Libraries have slowly reopened in a limited manner and with socially distanced protocols in place—masking, distanced seating and severe restrictions on indoor group gatherings. While various collaborative activities can be conducted online, using new platforms designed to replicate the gathering experience, many users still yearn for the in-person collaborative-style experience. Community engagements have moved online, and, for the first time, the Library of Congress held the 2020 National Book Festival as an online event in September. These novel ways of engagement, while limiting for physical interactions, have ameliorated persistent inequities of access. In a virtual context, library users do not have to face barriers of travel funding or other financial and social limitations.

Libraries are critical institutions for facilitating democracy, rule of law, and social justice. In the United States, the summer of 2020 ushered in a painful season of global reckoning for racial injustices, triggered by the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police officers. While many libraries were still physically closed, support for racial justice was swift and strong. Libraries provided online information resources for researchers, protesters, and allies. Virtual exhibits, such as the exhibit, were installed to support the Black Lives Matter movement.

What then will be the future trajectory for library users in a post pandemic context? Technology has been more fully harnessed on an expansive and deeper scale to leverage library services and access to resources. A significant change which will likely persist is the transition of the more traditional user to digital content (and an increasing comfort level with the latter). Overall an acceleration and acceptance of the concept of the online library, not just the library as a physical place, has taken place. While social in person interactions will reemerge, many users will continue to value and expect a continuation of the newly discovered ease of access to the library’s resources facilitated by the expanded availability of virtual collections.

Feature image by Chris Montgomery

The post The socially distanced library: staying connected in a pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

International Open Access Week 2020: What can a university press do to drive open access?

Open Access Week is an opportunity to celebrate, discuss, and push forward open access throughout the scholarly community. This year’s theme is “Open with Purpose: Taking Action to Build Structural Equity and Inclusion” so, to kick off the week’s conversations, we’re taking a look at the open access (OA) publishing taking place at Oxford University Press (OUP) and how the Press is working with researchers, societies, and libraries to support and develop the wider OA landscape.

OUP is the largest university press publisher of OA content. We published our first OA research in 2004 and launched our first fully OA journal—Nucleic Acids Research—in 2005. We now publish 80 fully OA journals and have published 115 OA books. We also offer an OA publishing option on over 400 journals in our publishing portfolio and, since 2004, have published more than 70,000 OA journal articles.

Why is OA so important for a university press?OA publishing makes research free to read and easier to re-use and build upon. Put simply, open access to research is a public good. This is especially important to OUP as OA publishing supports our mission to further the University of Oxford’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. As a university press, we’re embedded in the scholarly community and can use this position to drive OA publishing forward through cooperative action and compromise, working alongside our library customers and our society publishing partners.

One of the crucial aspects of our role as a publisher is to ensure the continued quality and academic rigour of research published through an OA model. All of the research we publish in our journal portfolio undergoes a rigorous peer review process where subject matter experts read and offer feedback on research methodology and findings, before offering an independent judgment on the quality of the work. This reflects the formal process that all our scholarly books undergo, with Delegates of the University ultimately determining whether a book is accepted for publication, after comprehensive review. This is vitally important in a context where misinformation is rife and researchers are under enormous pressure to deliver their findings rapidly.

How is OUP working to build OA publishing?As well as assuring the quality of each individual piece of research, at OUP we are creating more high-quality outlets for OA research. This year saw the launch of our flagship OA journal series, Oxford Open. The series is underpinned by shared principles of open research, and now includes Oxford Open Materials Science, Oxford Open Immunology, and Oxford Open Climate Science—with more titles on the horizon. Alongside this, we are working with our society partners to identify titles that would benefit from moving to a wholly OA model and supporting their transition. More than two thirds of the journals we publish are owned by learned societies and we want to make sure that the accelerated transition to OA is sustainable for them and their members. For scholars in developing countries, we offer fee waivers in our fully open access journals to ensure an equitable route to publishing.

Another of the important ways in which we work within our community towards greater open access is in working closely with funders and policy makers for mutually beneficial outcomes. By meeting with funding bodies and those shaping the future of research policy, we are able to offer an important perspective as a department of the University of Oxford and as a publisher in our own right. These conversations are an important opportunity to make sure the voices and positions of the learned societies we partner with are heard alongside those of large publishers. We cannot all move at the same pace and an inclusive and considered approach is important.

What is next for OA publishing at OUP?One of the areas of focus for the OA debate at the moment is defining the future of the OA book. As the world’s largest university press, we have a sizeable academic monograph programme and a growing OA books programme, which began almost 10 years ago. However, increasing OA books publishing is not as simple as just adopting a model that has worked for journals. A lot of work is underway at OUP to understand and adapt the existing model to the complexities of the book publishing process and ensure that the outcomes support book authors. Working collaboratively with funders, policy makers, industry bodies, and research institutions is the best way to achieve this. (Look out for more on this later in the week!)

Another area of nuance in the debate is subject area. Many of the initial forays into OA publishing took place in STM publishing. Open access to research is important for those working in the humanities and social sciences as well, but the context needs to be recognized. At OUP, we publish a varied list in humanities and social sciences and a large number of academic monographs, a format often published predominantly by university presses rather than larger commercial publishers. Generally, there is a comparatively lower volume of research published in humanities and social sciences, which given that existing OA business models tend to operate on a per article basis, means that journals in these areas would find a rapid switch to a fully OA model challenging to manage financially. Equally, monographs, which are a core part of scholarly discourse in humanities and social sciences, increase in scholarly value over a number of years as future research draws on them. This means that the sales life of a monograph is long. Immediate OA jeopardizes these longer-term sales, with negative consequences for the financial stability of monograph publishing. There’s also a question of appropriate licenses for re-use in humanities and social science disciplines, where the nature of content is different, and where secondary images, quotations, and artwork (which authors will need to acquire permissions for) are often used to illustrate arguments.

Meanwhile, the OA world is also complex to navigate for university librarians whose budgets are more stretched every year. The advent of Read & Publish deals in the last few years has meant institutional and, in some cases, national-level agreements to redirect funds previously earmarked for subscriptions towards the payment of OA publishing fees. OUP has 11 such agreements in place, including the first of its kind in Mainland China. By working closely with colleagues at institutional libraries and national consortia, we are able to reach fair and equitable agreements that further OA publishing without putting undue pressure on one area of the scholarly community—be it publishers, authors, or librarians.

There is still considerable work to do to continue the transition to OA and make sure this, like other areas of the scholarly communications ecosystem, is as equitable and inclusive as possible. As a university press, we are committed to continuing to drive this change forward.

The post International Open Access Week 2020: What can a university press do to drive open access? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 17, 2020

When is a patent price ever “unfairly high”?

The boundaries between patent and antitrust are never crystal clear. Part of the confusion comes from patent law’s historical “monopoly” roots. In early seventeenth-century England, those “letter patents” that originated from meritorious artisans’ grants in Renaissance Venice took an upsetting twist and degraded into a royal privilege to monopolize trades by those favored by the Crown. This historical entanglement left unfortunate space for confusion to grow throughout the centuries afterward. Further complicated with the fluctuating landscape change of antitrust itself, properly delineating the intersection of antitrust and patent has become a challenge faced by most competition law authorities worldwide, particularly when it comes to the current innovative economy and the necessary paradigm shift it legitimately demands.

Such challenge is no less acute in contemporary China. In fact, it is arguably more difficult because of China’s own historical complications, and the seemingly dramatic tension thus forged with a burgeoning economy today. Starting in 1978, the glorious economic reform of this young ancient country, essentially the aspired transition from a wholly controlled regime to a reasonably fledged innovative market economy, albeit with socialist characteristics, is still on its strenuous way. All kinds of obstacles need to be overcome along the way, ranging from formal restraints in laws and infrastructure, to lingering outdated theories that remain powerful impediments. On the other hand, to quickly adapt and facilitate the distinctive features of an innovative market economy, Chinese anti-monopoly (AML) authorities equally need to accomplish a static-dynamic paradigm shift. This shift would be partially addressed by an in-depth understanding of the sophisticated interplay between antitrust and intellectual property (IP).

A curious thread of this intersection tapestry is the concept of “unfairly high patent pricing” under the AML. In contrast to US antitrust but not facially dissimilar to EU competition law, the AML forbids a dominant undertaking from “abusing its market position” by selling at “unfairly high prices.” However, neither the anti-monopoly statute nor its practical guidelines gave an administrative definition to this key concept. Correspondingly, courts and AML authorities have striking discretion in characterizing a market price as “unfairly high,” potentially exposing the undertaking to harsh penalties. Two recent landmark cases with a key allegation of “unfairly high patent pricing” are the 2015 decision against Qualcomm Inc. by the National Development Reform Commission, and an ongoing investigation against Ericsson by the new authority (established in April 2018), State Administration for Market Regulation.

Section 55 of the AML arguably constitutes an IP “safe harbor,” providing that a proper exerciseof Intellectual Property Right (IPR ) shall be immune from scrutiny, while “an abuse, excluding or restricting competition” shall not. Despite the statutory framework, several recent cases have indicated a seemingly substantial departure in practice from this competition harm-focused approach, which generally use a more simplistic “benchmark comparison” methodology. This rough observation has been further supported by the newly passed agency regulation, i.e. Anti-monopoly Guidelines for IP (passed in January 2019, and published in August 2020).

Casting political economic arguments aside, one crucial reason for this departure is the lack of systematic understanding of the patent-antitrust interplay. Ambiguity lies in two aspects. One, due to the very patent mechanism in fostering innovation, even a proper exercise of right would necessarily restrict certain types of competition. Thus, it seems that an over-general standard of whether “to eliminate or restrict competition” cannot work as the ultimate test to differentiate abuse from legitimate exercise. Two, despite extensive use of “patent abuse” worldwide, the exact contour of this concept remains equally elusive. Resorting solely to the various constructions in comparative law, helpful as it is, cannot resolve these ambiguities adequately. To assess the interplay, we must not dodge the question of whether an act, such as the alleged “unfairly high patent pricing,” falls outside the scope authorized by Chinese patent law, in that it not only restricts competition, but also in a way that departed from what patent law has contemplated.

In a nutshell, the patent regime promotes innovation essentially through the instigation of dynamic competition. Specifically, it (1) bridges an innovator’s R&D to market demands: the better aligned a new technology to consumer needs, the more valuable this “shell” of right would become in the marketplace, thereby resulting in higher profit an innovator can harvest by excluding imitating competitors (competition by imitation, or CBI); (2) by restricting CBI with reasonably tailored claims, patent law simultaneously induces social resources into “inventing around” activities, i.e. to provide better/cheaper substituting technologies, thereby encouraging competition by substitution (CBS). In certain circumstances, the fruits of such CBS may also be protectable with new property right, such as the case of blocking patents, which would likely reduce the earlier patentee’s market power against the competitor; and (3) feeling pressure of CBS, the earlier innovator would likely be incentivized to continue her further “inventing around,” striving to stay a winner in the marketplace. In this way, a virtuous circle of dynamic competition may come into force.

Notably, a critical link of this circle pivots on the CBS precisely through the restriction upon CBI. This recognition has important implications in practice. For example, if an alleged patent price merely caused restriction on CBI as indicated in a supra-competitive profit, the AML must refrain from intervening. Instead, the focus should be on whether the questioned act restricts upon the CBS. A showcase of the CBS foreclosure is the historical deadlock between the famous Marconi diode and the Lee De Forest triode patent during early development of radio technology. The radical improvement as represented by the triode invention, even though literally infringing on the pioneer Marconi patent, is exactly the type of “creative destruction” Joseph Schumpeter once emphasized that boosts innovation.

Despite much sophisticated discussion of such theoretical worry however, decades of empirical research have showed insubstantial success in proving CBS foreclosure caused by “excessive” patent pricing in marketplace. A concurrent example for this disintegration is the robust innovation of the standard essential patent intensive industries, in the shadow of persistent “royalty stacking” prediction. An informed speculation is that precisely because the CBS link is pivoted by patent regime instigating dynamic competition, throughout ages the law has developed an implicit awareness, as well as multiple policy levers to safeguard the CBS from being lightly disrupted.

Judge Easterbrook once noted that antitrust is costly and the cost comes largely from judicial ignorance of business practices. In China today such ignorance is even intensified by policy makers’ divergent understandings of the government’s role in a market economy, as embodied in the 2016 Lin Yifu-Zhang Weiying Debate that drew an audience worldwide. Considering our meager knowledge of dynamic efficiency and innovation, as well as the low likelihood of dynamic competition suppression by high patent pricing in existing empirical research, it would be wise for the AML authorities to refrain from calling a patent pricing “unfairly high”, until the plaintiff proves otherwise with real evidence rather than theoretical conjectures.

The post When is a patent price ever “unfairly high”? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 16, 2020

They may not be pros—but they’re recording artists now

“If you give yourself to something that you think isn’t going to work, sometimes it does,” says retired school teacher and lifelong choir member Linda Bluth. She’s commenting on a surprising new musical bright spot that has popped up during the coronavirus pandemic: ordinary people becoming recording artists. From Brooklyn’s Grace Chorale to the New Horizons ensembles of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and East Lansing, Michigan, as well as students at New York’s Third Street Music School and Baltimore’s OrchKids program, lockdown-frustrated avocational musicians and music students have been making their recording debuts in online videos of virtual performances.

Professional orchestras started this video boom in the early days of the COVID-19 shutdown. With in-person concerts cancelled, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and others posted videos showing screens of rectangular boxes, each containing a professional musician in their own homes, playing a piece together, providing some sense of normalcy, that at least the music world was alive and well.

Soon avocational musicians gave it a try, including Linda Bluth’s Baltimore church choir. In-person choir practice was out of the question, as were online rehearsals. A lag time in sound transmission between online devices makes it nearly impossible for those on different ends of an online connection to play or sing in sync. “The need to make music with other people just throbs; it is such a deep ache,” says Kathy Fleming, a singer in Bluth’s choir who persuaded the others to make a video, with each of them recording themselves at home singing their parts to a song. Bluth wasn’t sure she wanted others to hear a recording of her singing. “I’m older,” explains this alto. “My voice isn’t what it used to be, not that I was ever a soloist. Kathy prevailed upon me to do it. I’m happy I did. It was satisfying to see how it all came together. But it felt so lonely to be doing this at home, by myself. I like the communal making of music, doing it with other people.”

To help choir members learn their parts, Fleming prepared tapes of the piece for singers to listen to at home. On the tapes, four of the choir’s strongest singers sang the separate parts—soprano, alto, tenor and base—to piano accompaniment. When choir members felt they knew their parts, they used a cellphone or tablet to record themselves singing it. While recording, each listened to the reference tape through earbuds, to keep the right rhythm. Only their own singing was recorded. Their church, Govans Presbyterian, hired a tech person to combine the recordings. “It’s embarrassing to hear yourself sing,” notes fellow alto, Patricia Short. “But I knew they would blend it all together. If it’s not exactly right, they’ll blend it.” Their first blended virtual performance video was such a hit that they made another.

A virtual performance video created by singers and instrumental musicians from Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia.

A virtual performance video created by singers and instrumental musicians from Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia.Dr. Joyce Garrett used a similar strategy with the choirs she directs at Alfred Street Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia. “We have all ages and levels of ability participate because you want to include everyone you can, connect with all these wonderful people,” she explains. “If some don’t have the best voices, we may not use their audio as much, but we include all their faces in the video.”

A small choir I sing with in White Plains, New York, used a different method for helping us learn our parts. Our accompanist, Georgianna Pappas, made a recording of the piano accompaniment, and then made additional recordings, over-dubbing herself singing each part on top of the piano track. We then spent several weeks having weekly Zoom meetings so each of us had chances to turn on the mic on our computers and sing a section of the piece for the choir director to hear and correct. As the lone demonstrator struggled to sing, the others put their mics on mute and sang along at home, even though nobody could hear their singing until it was their turn to be the guinea pig. As choir member Kim Force notes, “It was harder than I thought to record one perfect, uninterrupted take. I was so proud of the final product. Seeing everyone’s faces and hearing their voice was incredibly joyful.” A British ensemble, the St. Giles Festival Choir, has created a video on the ups and downs of making these videos.

However, an ad-hoc woodwind quintet found a way around the online lag time. They recorded a lovely four-minute piece, “Waiting Room,” that they played together at the same time via Zoom with all mics live, as if they were in a pre-pandemic recital hall, even though they were in their own homes. The group’s French horn player, New York pediatrician Dr. Marc Wager, asked Zeke Hecker, a retired Vermont school teacher-turned composer, to write a piece for the quintet in which the online lag wouldn’t matter. “It didn’t take long to realize that I had to write a piece in which people don’t play together,” Hecker explains. “I made sure that people don’t have to enter and exit at precisely the same time or keep the same rhythm. Some are playing long drone notes against which someone else plays a melody line. They all have the score and can hear when someone has stopped playing and that it’s then their turn to start. There are also silences.” The quintet recorded a live Zoom performance that they’ve shared privately with friends. “I’m astonished at the favorable reception,” says Hecker.

Other avocational musicians—and some pros, too—are turning to a new free software program to conquer the lag-time issue and also create some online videos: Jamulus, which permits online audio-only same-time playing from different computers. To use this software effectively requires some technical savvy, as well as an investment in several hundred dollars worth of equipment, in addition to a laptop or desktop computer. Those who have mastered this option, including the Concordia Quartet and a retired data specialist who plays violin, Tom Frenkel, have created websites with how-to advice.

Until in-person performing can safely resume, musicians of all ages and abilities will continue to find creative ways to keep the music going.

Feature image: A virtual performance video by the choir of Govans Presbyterian, Baltimore, Maryland.

The post They may not be pros—but they’re recording artists now appeared first on OUPblog.

October 15, 2020

How cancer impacts older patients

The rapid growth of the population in the United States has resulted in an increase in the number of cancer patients who were diagnosed with having cancer when they were older. A national survey found that 1,806,590 people were newly diagnosed with having cancer in just this year, and 60% of those were diagnosed when 65 years or older. This major increase in the average life expectancy of men and women over the past 50 years is largely due to the development of effective treatments for cancer patients at an earlier age. Older patients, who have just been diagnosed, don’t have the advantage of being treated at an earlier age, with more effective treatments. Further, as cancer patients age along with their other serious medical problems increasing, there is a combined impact on their ability to function and the quality of their lives.

We need to learn more specifically in what ways cancer affects older cancer patients’ lives compared to those who are younger. Overall, in a number of large studies, older cancer patients said that they felt better emotionally and that they had a better quality of life than younger cancer patients. More specifically, other large studies found that when compared to those who are younger, older cancer patients had greater satisfaction with their medical care, fewer needs in their lives, were better able to get back to doing activities that they enjoyed, didn’t feel so tired, and had fewer financial problems. One of the most important things older cancer patients talk about is how wonderful it is to have grandchildren in their lives. As an older patient said: “I would not want to give up the time that I spend with my grandniece and grandnephew. It is the high point of my week. That’s my purpose for this year.”

Other studies have found that older cancer patients have a worse quality of life than younger patients, which have been largely due to physical problems that come with getting older. The physical problems that make older cancer patients’ lives so very difficult include having greater difficulty in walking, more medical problems in addition to having cancer, more pain when they move around, and becoming increasingly frail as they get older. Consequently, those who have any of these physical problems also need to get help from their family and friends, such as doing chores around the house, going to stores to get things that are needed, and doing things they love to do but are no longer able to do, such as going to movies. Further, as older cancer patients get older, some of their family and friends will also get older or die. One older cancer patient said when this happened to them, “I’m lucky if somebody calls me once a month. There were seven or eight of my friends who sat together in church. Now they are all gone. They either moved out of the area or just don’t come anymore. I sit next to myself. I eat alone. It’s hard to eat alone all the time.” In addition, older cancer patients are afraid of getting older. As one patient said, “I think of the consequences of aging, such as not being able to take care of myself.”

My book, Older Survivors of Cancer, further explores these issues. I felt it was important to write this book due to the increasingly large number of older cancer patients in the United States, particularly as older patients continue to age. Initially, doctors began to recognize and then develop new medical treatments, specific to older cancer patients, particularly those who were now in their 80s and 90s. After effective new treatments had begun to be developed and found to be successful, attention has turned to also improving the quality of their lives: emotionally, how well they were functioning, their relationships with their family and friends, and their social life. Despite the growth in the number of older cancer patients, and the importance of these issues, almost no books have been written concerning the quality of their lives.

In order to better understand how having had cancer affects older patients’ lives, we must address the first-hand experiences of each patient from before diagnosis up to the present. I feel it is important to set up dialogues between one older cancer survivor and another, who may have had the same type of cancer and age as themselves. That connection between older cancer survivors is very powerful in improving their quality of life—that they don’t feel so alone, that they feel understood. In addition, we must support their family, friends, and any person who becomes increasingly afraid of getting cancer as they get older. Having survived cancer at an older age, along with an improvement in the quality of their lives, is exactly what older cancer survivors want, and what they need.

Featured image by MabelAmber via Pixabay

The post How cancer impacts older patients appeared first on OUPblog.

October 14, 2020

On the same page: Harlequin, harlots, and all, all, all

The post for August 26, 2020 was called “Harlequin’s Environment.” Two more essays followed, and ever since I have been meaning to return to the buffoon’s dictionary page, especially because in that post I misspelt the Dutch word for “harp” (my apologies and thanks to our correspondent who spotted my wrong form). Those who have read the entire series will remember that, though harlequin is still believed to be a word of “disputable” origin (the epithet in quotes means that the dictionary maker has chosen to remain noncommittal: “I am aware of all the conjectures but would rather not get off the fence”), it, most probably, was coined in medieval England and referred to Herla, the leader (“king”) of the Wild Hunt, a procession of dead warriors. From England it spread to the Romance world and after many adventures returned to English with its most recent sense. The root har– meant “army, troops,” as it still does in German (Heer “army”). We can only guess why the Germanic noun for “army” enjoyed such popularity in the Romance lands, but it certainly did.

Albergo: From Germanic to Italian. (Image by Hermann Junghans)

Albergo: From Germanic to Italian. (Image by Hermann Junghans)Take, for example, German Herberge “inn; hotel,” that is (literally), “army shelter, shelter for an army.” It made its way into Medieval Latin as heribergium; hence French auberge and similar words in Italian and elsewhere. Harbor is almost an etymological doublet of the words listed above, another shelter (this time, for ships). The difference between her– and har– should not confuse us. In Early Modern English, but, apparently, after the colonization of America, the group er– became ar-; hence clerk (as pronounced in American English, with the vowel of jerk) and Clark; Berkeley (in the United States) and the name of the philosopher Berkeley, pronounced as Bark-ly; University and varsity; sometimes the same word splits into two, as happened to person and parson.

There were enough native words for “barracks” in the Romance language, yet the German noun conquered most of Western Europe. (The ancient Romans called their barracks castra “camps.”) Someone who provided lodgings, a purveyor of lodgings (for an army), was called a her-berg-ere. Today, a harbinger (this is the modern continuation of herbergere) announces or foreshadows the arrival of someone else or of a future event, a forerunner, and the ancient association with the army is forgotten. Shakespeare was fond of this word (and I think his harbingers usually promised the advent of good things rather than disasters).

This is a German Harnisch, not a Modern English harness. (Image by Hans Braxmeier)

This is a German Harnisch, not a Modern English harness. (Image by Hans Braxmeier)An instructive case is the English harangue, “a long, passionate oration.” Like Harlequin, harangue reached England from France, but in French and in other Romance languages (arrenga, arringa), it is from Germanic, where it referred to a crowd of armed warriors standing in a ring (and, apparently, listening to an oration by the leader). Next comes harness, first recorded in English around 1300 with the sense “baggage, equipment; trappings of a horse.” But around the same time, it could also mean “body armor; tackle, gear,” as it still does in German (Harnisch). The route is familiar: from Old French to Middle English. Harness, like harangue, is an ancient compound, ultimately from Old Norse, in which herr meant “army” and nest meant “food, provisions” (both words are alive in Modern Icelandic). The compounds, whose ancient structure has been forgotten, are sometimes called demotivated (for example, ransack, from Old Norse ran- “house” and saka, related to sækja “to attack”; only unusual length and antiquated spelling may give away such formations: the classic examples are Wednesday “Wodan’s day” and cupboard, the latter rhyming with Hubbard).

In that earlier blog post, I briefly mentioned the verbs harry and harrow (as in Harrowing of Hell). Harry is English, harrow reached English from Scandinavian. Harass, from French, seems to have a different (but also Germanic?) root. In any case, harass, recorded in English only in the eighteenth century and in American English still retaining its stress on the second syllable, found itself in good company.

Also, at least two her– words have the same root as harbor, harangue, and the rest. Their familiar itinerary may be, but not always is, from Germanic to Old French and back to Middle English. Such is herald, originally hari-wald, in which har– means “army” and wald– meant “rule”, as it still does in English wield. A herald is an envoy, someone who delivers proclamations, thus, a person, not so different from a harbinger. But heriot is “pure English.” It emerged with the sense “feudal service consisting of military equipment restored to the lord on the death of a tenant.” I’ll skip the history of –ot; the meaning of her– should be clear by this time.

John Haywood, the historian. (Image by Willem de Passe)

John Haywood, the historian. (Image by Willem de Passe)Such then is the linguistic environment of Harlequin. My main question is about harlot. Does it belong here? The next post will be devoted to this word. Today, I’ll only reproduce a passage from The Life of King William the First, sirnamed (sic) Conqueror, written by John Hayward (1613) and reprinted in the third volume of The Harleian Miscellany (London, 1809). The passage below will be found on p. 119 and in Notes and Queries 2/X, 1860, p. 44:

“Robert, Duke of Normandy, the sixth in descent from Rollo [that is, Hrólfr, a famous Viking, the founder of the duchess of Normandy] riding through Falais, a town in Normandy [the seat of the Dukes of Normandy], espied certain young persons dancing near the way. And as he staid (sic) to view awhile the manner of their disport, he fixed his eye especially upon a certain damsel named Arlotte, of mean birth, a skinner’s daughter, who there danced among the rest. The frame and comely carriage of her body, the natural beauty and graces of her countenance, the simplicity of her rural both behavior and attire, pleased him so well, that the same night he procured her to be brought to his lodgings; where he begat of her a son, who afterwards was named William. I will not defile my writing with memory of some lascivious behavior which she is reported to have used, at such time as the Duke approached to embrace her. And doubtful it is, whether upon hate toward her son, the English afterwards adding an aspiration [that is, h] to her name (according to the natural manner of their pronouncing), termed every unchaste woman Harlot.” (A note on p. 120: “…after the Conqueror obtained the crown of England, he often signed with this subscription—William Bastard; thinking it no abasement either to his title or reputation.”)

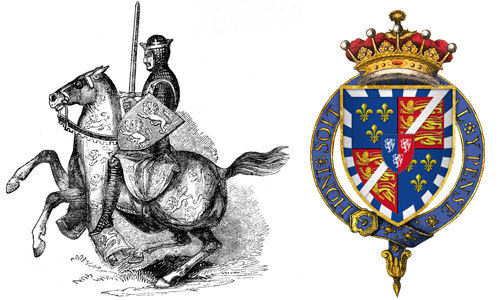

Left: William the Conqueror. Right: Bend sinister. (L: William the Conqueror on Horseback, R: Coat of arms of Sir Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester)

Left: William the Conqueror. Right: Bend sinister. (L: William the Conqueror on Horseback, R: Coat of arms of Sir Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester)Doubtful indeed! Today, I’ll only say that the word harlot has nothing to do with King William and that the name of his mother has come down to us in many forms: Herleva (usually mentioned in history books), Arletta, Arlotte, and Harlette. Her social status can no longer be determined (it was hardly so low). The story of the girls dancing “near the way,” unlike the reference to “lascivious behavior,” inspires little confidence. Though in his youth William suffered from his illegitimate birth, at that time being a “bastard” was less important than being born to a noble father. Such “bastards” found it unnecessary to conceal their status, as the existence of the bend sinister on their shields show.

Feature image: Grande Ludovisi sarcophagus, unknown artist

The post On the same page: Harlequin, harlots, and all, all, all appeared first on OUPblog.

October 13, 2020

The importance of occupational skills in understanding why individuals migrate

Why do some individuals move to another country, while others don’t? This question is fundamental because it has important implications for the characteristics of migrants (vis-à-vis natives), for the speed of integration of migrants into the destination country’s labor market, and, more generally, for the impact of migration on the sending and destination country.

In his seminal 1987 paper, George Borjas argues that individuals decide whether or not to migrate by comparing the income they expect to earn at home and abroad. Since skills are an important determinant of income, individuals allocate their skills to the country where these skills are rewarded the most. One implication of the Borjas model is that migrants who move from a country with high returns to skills to a destination with low returns to skills should have lower skills than individuals remaining in their home country—that is, migrants are negatively selected on skills from the sending country’s population. However, empirical studies show that individuals migrating to OECD countries are typically more educated than non-migrants (i.e., positive selection on education), even though many come from (developing) countries where returns to education exceed those in the OECD. This is at odds with the Borjas model and left both researchers and policy-makers wondering about the role of economic motives for migration.

One potential explanation for the apparent conflict between migration theory and empirical results is that individuals are not maximizing their income when deciding whether or not to migrate. However, this conclusion is only valid under the assumption that educational attainment provides a suitable depiction of the skills individuals consider when they decide about migration. In other words, the assumption implies that income maximization is equal to the maximization of labor-market returns to educational attainment. Our research strongly implies that this assumption does not hold. In fact, the common approach in prior migration literature of treating education as synonymous with skills may lead to an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of international migration.

Our research is the first to assess the role of occupational skills, that is, human capital acquired through performing job tasks, in the migration decision. We primarily distinguish between cognitive skills—for example, problem-solving, proactivity, and creativity—and manual skills—for example, physical strength and using machinery and tools. Occupational skills reflect the knowledge and capabilities relevant to the labor market more directly than educational attainment, which is typically fixed after labor-market entry and is therefore uninformative regarding skill developments during the career.

To investigate the importance of occupational skills for migration decisions, we use the case of migration from Mexico to the United States. Mexican migrants constitute by far the largest foreign-born population in the United States; almost one-third of all foreigners are Mexican-born immigrants. Mexico is also the first major emigration country that provides detailed information about the job task requirements of its workforce through a representative worker survey, which we use to construct the occupational skills measures.

Comparing the occupational skills of migrants and non-migrants, Mexican migrants to the United States are positively selected on manual skills, that is, migrants have higher manual skills than non-migrants, and are negatively selected on cognitive skills, that is, migrants have lower cognitive skills than non-migrants. In accordance with the Borjas model, this selection pattern can be explained by cross-country differences in returns to occupational skills, since returns to Mexicans’ manual skills are higher in the US than in Mexico, while returns to Mexicans’ cognitive skills are lower in the US than in Mexico. These results suggest that if policy-makers want to attract foreign workers with certain skills, they should focus on setting the labor-market returns to these skills appropriately.

The observed selection pattern has remained stable since the 1950s and has thus been largely unaffected by several substantial changes in US migration policy and visa regimes. Importantly, we also observe the same selection pattern within each education category, and also when accounting for persistent differences between geographical regions, industries, and broader occupational groups. This means that our results do not merely reflect that Mexicans are more likely to migrate if they are low educated or if they work in certain regions (e.g., those close to the US border), industries (e.g., manual-intensive industries), or occupations (e.g., agriculture).

Finally, our research provides direct evidence that the allocation of occupational skills is responsive to economic incentives by showing that differential returns to occupational skills between the United States and Mexico are a significant predictor of migration. Strikingly, occupational skills are more important for understanding the migration decision than education, which is the main ingredient in the calculation of the economic benefits of migration in most existing research. In fact, education plays almost no role in migrant selection and the assessment of migration benefits over and above its effect on occupational choices.

One explanation for the focus on education as a proxy for migrant skills in previous literature is data availability, as measures of educational attainment are readily observed in international (e.g., census) data. However, our results strongly suggest that focusing on education alone is not sufficient to capture migrant skills. Since internationally comparable data on occupational skills are still scarce, we emphasize the importance of collecting such data (e.g., through job task surveys or direct assessments) in a wide range of emigration countries to improve the measurement of migrant skills. We believe that this would provide an important building block toward better understanding migration behavior.

Featured image by Caroline Selfors via Unsplash

The post The importance of occupational skills in understanding why individuals migrate appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers