Oxford University Press's Blog, page 130

October 12, 2020

Five things you didn’t know about Beethoven

Films like Immortal Beloved and Copying Beethoven, whatever their value as entertainment, have helped create an image of the composer that often runs counter to the historical evidence. Here are five things that might surprise you about the composer.

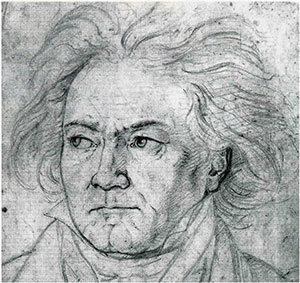

He laughed a lot Beethoven 1818, by Friedrich August von Kloeber

Beethoven 1818, by Friedrich August von KloeberMost images of Beethoven—especially those done after his death—show him scowling. But contemporary accounts make it clear that he was quick to laugh, and his letters reveal him as an incorrigible punster. Portraits of him from his own time typically show a contemplative gaze, exactly the kind of look one would expect from a creative artist. The scowl made its appearance only later. And as the public gradually became aware of his deafness, his thoughts of suicide, and his unhappy love affairs, the scowl became all the more intense.

He was frequently in loveThe identity of the “Immortal Beloved,” the unknown woman to whom Beethoven addressed a passionate letter in 1812, remains a matter of controversy. But it was far from Beethoven’s only affair. As one of his students observed, the composer “was frequently in love, but usually only for a very short time.” A longing for marriage is in any case a theme that runs throughout Beethoven’s early correspondence.

He was greatly admired during his lifetimeBeethoven’s contemporaries found his music challenging, but works that listeners resisted at first, like the Eroica symphony, became crowd favorites within a few years. From around 1810 onward critics consistently hailed Beethoven as the greatest living composer of instrumental music. It was only the works of the composer’s final decade (1817-27) that truly baffled his contemporaries, but even here, the Ninth Symphony (1824) enjoyed immediate acclaim from many critics.

He was never stone deafBeethoven’s hearing began to decline while he was still in his twenties, and it deteriorated severely in the last ten years of his life. But the available evidence strongly suggests that he never lost his hearing completely. He worked tirelessly with doctors to find a cure, used ear trumpets, and even concocted some sort of resonator on top of his piano to deflect the sound not outward, at a right angle, but instead directly toward himself while seated at the keyboard.

He had to hustle to make a livingUnlike most other major composers of his time, Beethoven had no permanent appointment at a court or church, which meant that he had to cobble together an income from a variety of sources: teaching, performing, and above all selling his published music. But he was not a very good businessman and lamented the countless hours devoted to haggling with publishers. We can only imagine how much more he would have written had he had more time to do so.

The post Five things you didn’t know about Beethoven appeared first on OUPblog.

October 11, 2020

The emerging economic themes of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has created both a medical crisis and an economic crisis. As others have noted, it presents challenges just as big as those in the Spanish Flu Pandemic and the Great Depression—all at once.

The tasks currently facing policy-makers are extraordinary. The ideas, arguments, and proposals in a new special issue of OxREP are intended to support them in that urgent work. Though many of these articles were written as the virus first began to spread, they remain as timely and important as they were on original completion. We have learned a lot in the short time since the pandemic began—but it is extraordinary how little we still know.

In reviewing the research, three broad themes emerge. The first is that the pandemic requires entirely new types of intervention. Many of the contributions in this issue explore them: what they are, how they might be improved, and possible alternatives to those currently in place. Some are designed to respond to the medical emergency: to control the spread of the virus in an efficient and workable way. Others are to tackle the economic emergency: to support workers and businesses, to deal with the inequalities in impact, to maintain financial stability, among much else.

The second broad theme is that the challenges we face are global. An infectious disease like COVID-19 spills across borders and cannot be handled by any country acting alone. It has spread to low- and middle- income countries, many of which have less developed institutions of government and public administration, with implications for responding effectively. It has had significant impacts on the volume of international trade and stirred up pre-existing protectionist pressures. And it has made very clear the urgent need for effective international co-ordination to contain the medical and economic emergencies—but, as the current response to the pandemic has shown, such cooperation is very hard to achieve in practice.

The third and final theme is that, while the challenges are immense, there are important opportunities in how we choose to respond. To some, for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a failed system of corporate governance: there is now a chance to reform business and finance. To others, it has exposed the extent to which economies around the world rely on low-wage workforce: this ought now to have wider implications for pay and immigration policy in the future. As we engage in extraordinary levels of fiscal expenditure, there is a chance to focus on policies that will not only support economic recovery but also help to mitigate climate change. And in reforming our international institutions to support greater co-operation, there is a chance to prepare not only for the next infectious disease, but for the many other global problems that will we face in the twenty-first century.

The post The emerging economic themes of the COVID-19 pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

And thus Zoom turns us all to fools and madmen

In 3.6 of King Lear, four characters take shelter in a hovel: one is mad, one is pretending to be mad, one is pretending to be someone else, and the other is a professional fool. The result is somewhat chaotic:

EDGAR Frateretto calls me, and tells me Nero is an angler in the lake of darkness. Pray, innocent, and beware the foul fiend.

FOOL Prithee, nuncle, tell me whether a madman be a gentleman or a yeoman.

LEAR A king, a king!

FOOL No, he’s a yeoman that has a gentleman to his son; for he’s a mad yeoman that sees his son a gentleman before him.

LEAR To have a thousand with red burning spits

Come hissing in upon ’em!

EDGAR Bless thy five wits.

KENT O, pity! Sir, where is the patience now

That you so oft have boasted to retain?

EDGAR My tears begin to take his part so much

They mar my counterfeiting.

LEAR The little dogs and all,

Tray, Blanch, and Sweetheart—see, they bark at me.

(3.6.6-21)

There is a weird poetry in the disconnected chatter of the scene that has rightly been celebrated. But it is also a very skilful dramatization of the ways in which a conversation can go wrong. While it is possible to make sense of individual speeches, they only fleeting cohere into purposeful sequences of talk. The Fool manages, briefly, to draw Lear into an exchange about madmen, only for the old man’s mind to turn immediately back to the fantasy of punishing his daughters. It is often unclear who is speaking to whom, or how much of the foregoing conversation each character has heard. Kent’s question, for example, directly follows a remark from Edgar, but is clearly addressed to Lear. (In performance, the two actors might bring this confusion out by talking over one another.) To add a final layer of complexity, some of what is said may not be heard by anyone else present, as when Edgar momentarily drops his guard to make a meta-conversational comment—presumably in an aside—on the difficulty of staying in character as Poor Tom.

With characteristic aplomb, then, Shakespeare has anticipated—by a good four hundred years—exactly what happens when more than three people try to chat informally via Zoom. The kind of interaction that would be relatively straightforward in person becomes torturously difficult. Everything takes longer. Everything requires more effort. Without careful attention to what linguists call “turn-taking,” things quickly descend into chaos.

Why this should be the case is not immediately obvious. If we can hear and see our interlocutors, if the connection is good and the lag minimal, why is it so much harder to string together rapid sequences of talk? The best way to answer that question is to turn it on its head. Properly understood, even the simplest conversation is an astonishing feat of interpersonal coordination. The remarkable thing is not that turn-taking so frequently goes wrong on Zoom, but that it ever goes right at all.

It is an observable fact that speakers are able to coordinate transitions between turns at talk to within a fraction of a second. Average response time in conversation is around 200 milliseconds. This is surprising because language production is comparatively slow—some 600 milliseconds from conception to articulation, even for a single word. Somehow the other participants appear to know in advance exactly when the current speaker will stop, what she will have said when she does so, and which of them should speak next.

To explain how this is possible, conversation analysts have come up with an awkwardly-named but brilliantly useful concept. A “transition-relevance place” is any point at which the current speaker might plausibly have finished. The end of a sentence, obviously, or some other less emphatic point of syntactical completion. But also, potentially, the punchline of a joke—or even just the moment, part way through a turn, at which the sense of the whole becomes clear. Two things matter about transition relevance places. The first is that they are projectable: it is possible to hear them coming. The second is that they are optional: the occurrence of a transition-relevance place does not necessitate a change of speaker any more than the occurrence of an exit necessitates that I come off the motorway. As the exit approaches, the possibility of my coming off becomes relevant (hence the name) but I can still choose not to take it.

A single turn may thus contain a series of transition-relevance places at which no transition occurs. Unlike a letter, or a WhatsApp message, the turn at talk is telescopic. Its length is the product of a fragile process of incremental expansion that might have stopped when it didn’t and needn’t have stopped when it did. And clustered around these potential stopping points is a series of micro-negotiations about whether this next exit is the one we will finally take. It is possible, of course, to make such things explicit: “I’ll stop there and hand over to Mike.” Most of the time, however, the exchange of turns is negotiated in ways that are largely subconscious. Intonation, gaze-direction, gesture, and facial expression, all play a part. An intake of breath or a tilt of the head can be enough to suggest that a new speaker is ready to launch. A glance upward can be enough to show that the current speaker is not yet done.

What Zoom does is to filter out much of this layer of subconscious communication. We cannot tell who anyone else is looking at, nor sense the tiny adjustments of body and face that would ordinarily help us to coordinate the exchange of turns. If you combine that with even a tiny lag, the whole exquisitely calibrated system begins malfunction. And thus Zoom turns us all to fools and madmen.

Feature image by Tim Gouw

The post And thus Zoom turns us all to fools and madmen appeared first on OUPblog.

October 10, 2020

Why do humans have property?

Property is a rather old subject. We’ve been writing about it since at least the time of the Sumerian tablets, in part, because after four and a half millennia we still haven’t settled on what property is, who has it, how we get it, or even what it’s for. Recently, arguments have surfaced that the destruction of property constitutes serious political speech. But property has a greater, very human, purpose worth understanding.

In the humanities, property is theft, violence, the cause of wars and quarrels in the world. To biologists, property is the possession or defense of food, mates, or territory. By that account many animals have property. But property is not inherently evil, and in fact indicates a willingness to respect that what is “yours” by definition cannot be “mine.” Recognizing this trait sets Homo sapiens apart from the rest of the animal kingdom.

How might a social scientist in the middle go about defining property? It’s clear that whatever property is, it involves people doing something with a material thing. It also appears that property isn’t discovered anew each generation. “No!” is how parents teach their children the rules of property.

Answering the question “Why do humans have the custom of property?” sheds light on the purpose property serves in modern society and how to view it. Aristotle gave us four explanations: material, formal, efficient, and final explanation. When taken as a whole, the four different causes explain the custom of property.

Material explanationHumans have the custom of property because when our body sees, hears, and touches the physical world, it connects a certain person to a certain thing by classifying the thing as “mine.” This explanation requires physical matter, including the human body itself. Our eyes see the world of people and things, and our ears hear the things people say about things. Our minds then classify such neurological impulses and return as output an instruction to act, to say things like “This is mine.”

Homo sapiens is the only animal whose mind classifies a thing as “mine.” Primatologists have good reason to believe that chimpanzees think things like “I want this,” but “I want this” does not mean the same thing as “This is mine” in the human animal, as every two-year-old learns, with great disappointment, from their parents. Mine means mine, atomically and reflexively, and it serves as the core for the custom of property in all human groups. In every language someone can say, “This is mine.”

Formal explanationProperty is not just about one person feeling and thinking, “This is mine,” and property is not a growl delivered with a curled lip and wrinkled nose. Property is a speech act, witnessed by other people, all of whom have been taught by the previous generation when such claims can be made. While the circumstances and the set of things may vary from culture to culture, there is a common abstract form by which someone can claim something as mine. Humans have the custom of property because people learn from their mentors under which circumstances someone can say “This thing is mine,” others can know that what this person says is true, and others cannot say “This thing is mine.”

Even though only I can use the concept “mine” to predicate a first-person claim on something, everyone else must use the concept “yours” when referring to my claim. I rely on the concept “yours” when I want others to acknowledge my claim that something is mine. There is no abstract concept of “yours” in any other animal because there is no abstract concept of “mine” in any other animal.

Efficient explanationThe material and formal explanations come together in the human agency that creates the efficient cause of property. Humans have the custom of property because when someone severs our connection to a certain thing, we resent the harm and injury we feel and attempt to defend ourselves by beating back the injury with some injury in return.

Resentment is the sentiment that prompts us to retaliate. It isn’t unique to humans. There’s a reason why you don’t poke a bear or even stand between a sow and her cubs. What is unique to humans is that we turn our disputes over to elders, judges, or juries to sift through conflicting claims of “This is mine.” In a tribal species, we tend to share our in-group resentments and empathize with in-group injuries. Two conflicting claims of “This is mine” can easily escalate to group-on-group violence which runs the risk of destroying the community. To mitigate such a disaster, humans have stumbled upon the tradition of using third parties to articulate what the expectations of the disputants should have been regarding the thing.

Final explanationIf, as David Hume noted, material things were not scarce and people by nature not selfish and limited in generosity, we would not need the custom of property. There would be no conflicting claims of “This is mine.” We would be bonobos in abundant fields of leaves and herbs. But that is not the world we live in. Humans have the custom of property because it confers peace to a species which is—as the seventeenth century German jurist Samuel von Pufendorf eloquently put it—often malicious, insolent, and easily provoked, and as powerful in effecting mischief as it is ready in designing it. We practice the custom of property because proximately there is not a short supply of people with an equal or stronger hand who may challenge our claim of “This is mine.”

Such is the Biblical story of Naboth’s vineyard. The uniquely human custom of property stood between King Ahab and the vineyard to protect Naboth from those who had a stronger hand to challenge his claim. When Queen Jezebel suggests that Ahab king up and take the vineyard from Naboth, it was not the custom of property that failed Naboth. Ahab’s character failed Naboth, Jezebel, and everyone who practiced the custom and depended on it for their protection. The custom of property doesn’t make us do evil things. An ethical character restrains our unlimited thoughts of “I want this” with a cultivated, reciprocal respect for “That is yours.”

Featured image via Pixabay

The post Why do humans have property? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 9, 2020

Scientific communication in the shadow of COVID-19

One of the most fundamental processes within any scientific field is communication of results of research, without which research cannot have an impact. If any piece of research is worth doing, effort is expended in doing it, and the results are of interest, then the research is not truly complete until it has been recorded and passed on to those who need to know the findings.

Today, a scientist wishing to share their findings with the world has a wide range of options at their disposal. Even without thinking about scientific journals, they could decide to tweet their research, 240 characters at a time, and instantly share news with everyone on the planet, in theory. Papers published in journals are likewise available online for anyone to find, although access may be restricted depending on the terms of publication involved.

However, what separates scientific communication from any other form of communication is that it is a mediated process, where the quality of the research being communicated is policed, at least again in theory, by the process of peer review by independent experts.

Peer review is, in any respectable Journal, a tough and rigorous process; in high-quality journals, up to 95% of submitted manuscripts maybe rejected as not being good enough to be published. Reviewers are busy researchers working in the field, who should undertake this voluntary and unpaid work as part of their contribution to their fields as professional researchers; when they submit papers to journals themselves they expect them to be reviewed, and so it seems fair to contribute to the process of publication by doing the same in return.

This all takes time. For the top journals in the world, with full-time professional editors, papers may be accepted or rejected in the space of a week. For most journals, however, it may take a matter of weeks or even months for a report to come back to authors, which may be followed by a lengthy process of responding to the reviewers’ critiques and perhaps undertaking additional cycles or review and revision. It can take from 3-9 months in many cases for a paper to go from manuscript to publication (assuming it is not rejected), a pace which most scientists are used to and accept, as part of the cycle of research and publication.

What if we don’t have time to be leisurely though?

What if there was a situation where the latest research needed to be communicated as quickly as possible, as people’s lives literally depended on the research getting from the lab bench to implementation and practice as quickly as possible?

A situation where the world was literally waiting for the results of the research?

Up to 2019, a scenario like this might have been dismissed as fanciful.

Then, in 2020, a virus, first identified in Wuhan, China in 2019, tore across the world with frightening speed and became the single most intensely studied scientific topic in history. As cases, and deaths, started to accumulate, large parts of the world went into lockdown, in part to buy time for the scientific community to work on understanding the disease, evaluate medical and clinical treatments, and work towards the ultimate goal of a vaccine.

Every question required careful yet urgent study, and key findings were quickly implemented in practice in the front lines of the war against COVID-19, with physicians poring over the latest advances to modify their practice in real-time. A genuinely unprecedented rate of publication occurred in an astonishingly short time, with over 23,500 papers being published up between 1 January and 30 June 2020.

How can the circuit from lab to practice best be expedited under these dreadful circumstances?

The main route of scientific communication absolutely has to be protected, with peer review ensuring that only reliable, safe, and useful findings are put forward, but of course many of those best qualified to review the papers are themselves incredibly busy in their own COVID-19-related research.

So, alternate routes, already increasingly present, came to great prominence. For example, preprint servers, where papers can be hosted before peer-review for rapid dissemination, became key resources. In some cases, politicians, the public or journalists picked up and publicised findings from such preprints without making the distinction that the work contained therein was not peer-reviewed and hence should be regarded as preliminary, or at least not validated by the standard quality control systems of science. Between January and May 2020, two databases—bioRxiv and medRxiv—hosted almost 3,000 papers on the topic, and such servers are now implementing far more stringent screening processes for submissions due to their widespread usage, albeit still short of full peer-review.

In addition, communication through social media, such as Twitter, can bypass the paper format entirely, and rumours, preliminary findings, and in some cases outright dangerous ideas flood onto the unpoliced expanses of these media, leading to situations which are particularly dangerous if they are picked up and amplified by others with great power to amplify news, such as politicians.

In parallel, the question of open access to research findings and data has come into even sharper focus, with a demand that the findings be brought, once validated, into the open without the barrier of publishers’ paywalls. As an example of open science and access to raw data, when the RNA sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was first determined by scientists in China on 10 January, it was immediately made globally available through a public repository database, and was being used as a basis for vaccine development within days.

How science communication should work (left) and how it is currently working (right)

How science communication should work (left) and how it is currently working (right)The pandemic has also placed new emphasis on the importance of multi-level science communication strategies, with scientists being challenged to be able to explain their latest findings variously and in rapid succession to experts, clinicians, politicians, journalists, patients, and the general public, and needing to be able to select the most appropriate language and approach in each case.

The vital importance of having a scientifically literate public has likewise never been clearer, to help people to interpret science-based findings and recommendations (and concepts such as risk) that change their lives but yet evolve on a regular basis, and to help them appreciate that scientists should and must change their advice when the evidence on which they base that advice changes as a result of ongoing research.

The negative side of science communication has also come to the front, with cases involving all the well-recognised and classified forms of communications misconduct, such as falsification, fabrication, and plagiarism. To take one example, a highly publicised study on the use of the agent hydroxychloroquine published in The Lancet involved a database which was found not to have existed, prompting a change in practice for that journal in terms of avoidance of such problems in the future.

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has seen the best of science and how it should work to respond quickly to an unprecedented challenge to the whole planet, focus the best qualified minds on the problem and a range of potential solutions, and communicate the outcomes to those who need to know them as carefully as possible, but it has also raised and amplified many challenges in scientific communication in the modern world.

So, a debate has been ignited about the ways in which science communication works, and how to trust scientific findings, which is likely to have long-lasting consequences.

In the meantime, we need to trust that science is our best route through these dark days, and that we will be protected by the continued operation of best practices in science communication.

We need to hope this will be the case.

Our lives depend on it.

Feature image used with permission from The White House on Flickr.

The post Scientific communication in the shadow of COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

How to write a byline

A while back, I wrote a post on how to write a biography, with some tips for long-form writing about historical and public figures. However, that’s not the only kind of biographical writing you might be called upon to do. You might need to write about yourself.

Many people are comfortable writing a personal bio of about two hundred words, but it can be surprisingly tricky to write a short byline for use in a newspaper, magazine, web article, or announcement for a talk. Here are a few tips.

Keep it short: The challenge of a byline is not just what to say but what to leave out. We’ve all suffered though dreary introductions that go on way too long. A byline is not a résumé. More is not always better.

Be yourself, but without the boring parts and with some sass: When I teach writing for publication, I ask students to craft a handful of 12-15 word bylines on the first day. Here are some examples, where writers both exhibit personality and give readers something to ponder.

Aurora loves jogging, juggling, and haggling, not necessarily in that order.

Joni plans a career in publishing once she is finished staring into the abyss.

Brian is trying not to say “um” any more than is absolutely necessary.

Cassidy is an incredibly sleep-deprived Pisces with a mild Twitter addiction.

Readers can identify with these personal characteristics.

Build credibility indirectly: So-and-so “is the award-winning author of” is fine for some audiences, but often an interesting personal detail is a more engaging way to build your credibility. You can paint a picture:

Jasper Fforde recently traded a varied career in the film industry for vacantly staring out the window and arranging words on a page.

You can offer authority and authenticity, as these two mystery/thriller writers do:

John Straley, a criminal investigator for the state of Alaska, lives in Sitka, with his son and wife, a marine biologist who studies whales.

April Henry knows how to kill you in a two-dozen different ways. She makes up for a peaceful childhood in an intact home by killing off fictional characters.

Consider the audience and occasion: You can—and you should—tailor your byline for particular audiences. What aspect of your background can you emphasize to make a connection to your audience? When I include that I’m from central New Jersey or that I own more dictionaries than anyone needs, I almost always get a reaction.

Use a byline to keep your focus: When you begin a piece of writing, consider writing a byline as your first step. The byline establishes a persona and defines your voice in the piece.

A student of mine, writing on the ways that millennials are revitalizing the plant industry, started with this byline, which gave her a voice to navigate the botany and economics of her topic.

Laura Becker is a tail-end millennial from California and currently resides in Oregon. She enjoys reading, spending time with her fur baby Ponyo, and watering her plants. When she isn’t doing one of those things, she can be found browsing Etsy or Amazon for her next plant.

When in doubt: If you are stuck on a byline, make a list of your favorite things to do, places to go, or things to eat. Look through some old photos or memorabilia, or through your closet.

Browse your bookshelves to borrow from other writers. Here’s one from poet Zeke Hudson, that I really wish I had thought of:

Zeke Hudson is… he’s uh… well, he’s usually much better at writing bios. This one’s a real clunker. You can see some of his better bios in Wend Poetry, Nightblock, and Banango Street, or in his chapbook from Thrush Press. Sorry everyone.

What’s your twelve-word byline?

Featured image by Rishabh Sharma via Unsplash

The post How to write a byline appeared first on OUPblog.

October 8, 2020

US journalism’s complicity in democratic backsliding

The unelected power of the Fourth Estate is never more evident—and potentially destructive—than during campaign seasons, when antagonists exploit the news to test authoritarian themes. I pose a question here that I hope editors and reporters are also asking now that we’re weeks away from the 2020 presidential election and high-stakes state elections: to what extent does the way journalists imagine the public shape coverage, particularly the amount of attention given to candidates who advance a punitive populism?

In 2015-16, the eventual Republican nominee for president obtained the blessing of Fox News but also substantial coverage from a wide range of news outlets. Neither Donald Trump’s poll numbers, fundraising ability, nor endorsements explained the pre-primary level of attention. The press apparently imagined a populist response to Trump as a precursor to actual evidence of widespread support. In this view, populist sentiment takes on a looking-glass quality, existing as a narrative template because journalists, along with those adept at media manipulation, anticipate its activation.

The responsible press should be careful to not internalize a proto-democratic duty to represent public mood in ways that justify attention to mobilized irrationalism. Journalists must recognize an uncomfortable symbiosis of media with populism during election cycles. The purpose of anti-media populists is to undermine faith in journalism and other institutions. As Bernat Ivancsics writes, speakers for “the majority” claim to redeem participatory qualities of democracy, a move “that flouts the technical-bureaucratic operation of the constitutionality of democratic societies.”1

The “earned media” Trump benefitted from in 2016 suggests that reporters were fascinated by the emotive mainsprings of populist support. This indulgence implies more than an elitist voyeurism of agitated, downscale Americans. Did respectable news outlets co-produce a crisis of democracy in the condoning of illiberal discourse? While journalists benefit from audience engagement in periods of crisis, they can lose control of coverage to anti-establishment actors. The lavish attention to Trump was apparently less threatening to journalism’s self-image under the assumption that he would never actually occupy the White House.

A punitive populism draws emotive power from many sources, and while it fluctuates in strength, it will persist without the help of responsible media. Journalists should not see it as their duty to represent the public against a cultural elite. The attention cable news lavished on Trump in 2016 seemed reasonable to many journalists: incidents would eventually out him as unacceptable, as Sarah Palin was exposed in 2008 during interviews with Katie Couric. Journalists will acknowledge that they benefit from audience engagement during times of crisis. A bridge too far— along the road to reflexivity— is the premise that journalism is complicit in democratic backsliding. Yet media scholars Elihu Katz and Tamar Liebes are persuasive in arguing that cynicism and audience fragmentation explain a retreat from ceremonial “media events” such as anniversaries and patriotic holidays. Commercially driven news outlets and anti-establishment agents are now invested in disruptive events.

Literature on democratic backsliding originated in political science but must now consider media-led weakening of norms that support responsive governance and consent of the governed. Political actors participate in backsliding through the rhetoric of popular sovereignty and in maneuvers such as executive aggrandizement and harassment of the electorate. Backsliding is alternatively known as democratic erosion or degradation to emphasize an incremental process that begins in a democratic status quo, is not outright unconstitutional, and is typically initiated by the executive. The responsible press is not to blame for propaganda, misinformation, and virulent anti-intellectualism—“the hellscape that we wake up to every morning,” as my colleague Toby Hopp puts it. Media-centered goals nevertheless become more desirable for political actors if policy outcomes are unrealistic.

In a bygone era, the cohesive folkways of Congress discouraged open conflict. Legislators today worry less about rattling colleagues. Journalism, for its part, presents itself as the more civically responsible profession in the media/government nexus, acting as a warning signal to audiences, when it has actually incentivized incivility through its attraction to polarizing discourse.

Unlike in the postwar period, news media are no longer positioned to control the spigot of rumors, conspiracies, and other tainted information in a gateless environment. Enjoying a near monopoly in the control of political attention, the press of the pre-digital era was anchored by high modernism and elite consensus. Media politics would overtake party politics, however, bringing forth new forms of participation, setting loose irrational forces in contempt of the liberal order.

A journalism vigilant about norm-breaking would take responsibility for the news as its jurisdiction. The profession would recognize its power and its duty to shape policy agendas on behalf of those left behind by neo-liberalism. As for campaign politics, the press is miscast when it sees itself as an organ of direct democracy. A journalism that views itself this way risks collusion with irrationalism and complicity in democratic decline.

[1] “Uncomfortable Symbiosis: Attention Capture, Normalization, and Criticism in the News Coverage of Fringe Social Groups and Populist Movements.” Paper presented at the Global Perspectives on Populism and the Media Preconference, International Communication Association, Budapest (May 2018).

Featured image via Unsplash

The post US journalism’s complicity in democratic backsliding appeared first on OUPblog.

October 7, 2020

As daft as a brush and its kin

There was a comment on the simile daft as a brush, current in the north of England. As far as I can judge, no one knows why people say so, and I only want to explain why no one will probably ever be able to know it for sure. Similes with as and like in them are almost countless. I have discussed some of them in the past. In 1609, Robert Cawdrey published a book of “delightful” and other similes, and about a hundred years ago, Torsten H. Svartengren brought out a collection of intensifying English similes, culled from the OED and other sources (since that time, the book has been reprinted). Some similes make sense: for example, as coarse as hemp (or heather). Hemp and heather are indeed coarse. But cool as a cucumber? Many phrases of this type exist thanks to alliteration. Perhaps at some time, somewhere, cucumbers were associated with coolness, but, more likely, the simile was coined as a joke: just listen to coo-coo in it!

You can see here a Stradivarius violin, a fit fiddle indeed. (Image by Anton Miller)

You can see here a Stradivarius violin, a fit fiddle indeed. (Image by Anton Miller)Around 1450, people used to say as cunning as a crowder. In the past, cunning meant “skillful,” and crowder meant “fiddler” (crowd “an ancient Celtic stringed instrument”). Musicians are indeed skillful people, but the phrase probably owes its origin to the repetition of the k sound, for other professionals are no less skillful. However, one also recalls fit as a fiddle. When the idiom was coined (the earliest citation in the OED goes back to the beginning of the seventeenth century), fit meant “excellent”; yet the variant fine as a fiddle makes one think that the fiddle was chosen for both its “fitness” and the phonetic shape of its name. Idioms like right as rain and pleased as Punch can fill a volume. Here is a final example of an alliterating simile: “As crooked as Crawley.” Perhaps (perhaps!) the saying reminds us of a winding stream near St. Neots (Cambridgeshire). One should not jump to conclusions and dismiss all alliterating similes as mere exercises in euphony. Jumping in the area of reconstruction is in general not to be recommended. The Internet is full of explanations of the phrase dead as a doornail. I too have discussed it in this blog (see the post for April 15, 2015, devoted to the phrase to get down to brass tacks). The alliteration is obvious and may have been instrumental in coining the simile, but it was not a mere piece of charming gibberish, like cool as a cucumber: nails were called dead for a reason.

(Image by Jixuan Zhou)

(Image by Jixuan Zhou)Not only doornails are dead. We have as dead as a herring, as dead as mutton, as dead as a rat, and of course as dead as Queen Anne, mainly remembered from the proverbial phrase Queen Anne is dead. I am citing the idioms that I, too, have in my database (the idioms that have been discussed in popular journals in the course of the last three centuries). One can find all of them on the Internet. The definitions are invariably correct (there is not much to define here). However, beware of the notes on their origin if they contain the words of course and undoubtedly. Excuse me for repeating the same advice couched in the same terms again and again, but, unfortunately, the etymology of idioms is no less disputable than the etymology of individual words, even if for a different reason. When it comes to the origin of such phrases, well-known events, like the turmoil in 1714 that followed the death of Queen Anne, are rare. So why do people say as dead as a rat, with its puzzling variant as weak as a rat? Rat hunting was at one time a popular entertainment. I think there may be a connection between the idiom and the superstition, recorded in Shakespeare, about exorcising (“rhyming”) rats to death.

In 1971, the great folklorist Archer Taylor asked the readers of American Notes and Queries (ANQ) whether anyone could explain the simile as innocent as a bird. No one responded. Language subjects dogs, our most faithful domesticated friends, to torrents of abuse. As lazy as a dog is the mildest example of this abuse. Are dogs lazy? Are birds innocent? Is mutton “more dead” than beef or veal? Archer Taylor also wondered at the phrase as sore as a pup. In his reply (ANQ 1971, p. 135), B. Hunter Smeaton, a serious student of semantics, noted that the noun after as need not be meaningful (!), for the prosody of the formula carries the bulk of the message and diminishes or even eliminates its sense; hence, allegedly, drunk as a lord, mad as a wet hen, and the like. This statement, like the aforementioned reference to alliteration, is not diagnostic, because one never knows when one may dismiss the second part as nonsense or as a word beginning with a certain consonant. In my database, I have two notes trying to explain the simile dead as a herring. Both notes are clever. But perhaps the reference to herring is a joke? Cf. mutton, above.

A truly deep cat. (Image by Max Baskakov)

A truly deep cat. (Image by Max Baskakov)The person who coined the phrase as dead as Chelsey must have had some Chelsey in mind! In 1857, an old lady in Norfolk who said that her cat (!) was as deep as Chelsey could not explain the reference. I know nothing about deep cats, even though Chelsey Reach certainly exists. Idioms, like words, wander from mouth to mouth and may be garbled beyond recognition. All that allows me to say something about the northern idiom daft as a brush. Daft means “foolish” and is a probable etymological doublet of deft. The development was from “pleasant, gentle; friendly” to “silly” (mad has a similar history!). I’ll let our readers google for the origin of the idiom. What I found on the Internet is complicated beyond belief and therefore did not fill me with enthusiasm (intricate etymologies are usually untrustworthy), and I’ll venture my own hypothesis. Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary mentions “extremely eager” as one of the northern senses of daft (probably an intermediate step between “obliging” and “stupid”). Now, a new broom sweeps clean. Couldn’t the initial reference be to a very efficient, “extremely eager” new brush? But of course, those who use the adjective daft remember only the main sense (“stupid”), and the simile puzzles them.

Don’t mock a bald prophet! (Image via Wikimedia)

Don’t mock a bald prophet! (Image via Wikimedia)However, my hypothesis may be all wrong. Compare the phrase (as) funny as a crutch. A brush, if my suggestion has any value, may be “daft,” but a funny crutch? In the old days, physical deformity was supposed to be “funny,” and invalids, including veterans, were subjected to ridicule on the streets. Today, this abomination makes us sick. I’ll skip the exegesis, but wasn’t the Hebrew prophet Elisha mocked because he was bald? In any case, the English simile does not go back to antiquity. It has been suggested that the source of the idiom is Alonzo F. Hill’s book John Smith’s Funny Adventures on a Crutch, first published in Philadelphia in 1869. (Those interested in the adventures of one-legged soldiers are also advised to read Chapter 10 of Gogol’s Dead Souls, which contains “The Tale of Captain Kopeikin.”) A short discussion of the crutch idiom surfaced only in 1945, and the OED does not include it. Therefore, I don’t know its age. My reference to John Smith and Captain Kopeikin is a typical shaggy dog story: a funny crutch probably has nothing to do with Hill and is totally unrelated to a daft besom. But what if there is a connection?

Once again: idioms are fun.

Featured image by Svetlana Sinitsyna

The post As daft as a brush and its kin appeared first on OUPblog.

October 6, 2020

Rooting chimp communication in relevance theory

The key assumption of Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson’s relevance theory is that every act of communication comes with the promise (not the guarantee!) of being optimally relevant to its envisaged audience. Sperber and Wilson’s examples typically pertain to spoken face-to-face exchanges between two individuals: speaking Mary and listening Peter. A message gains in relevance for Peter to the extent that accepting it as true has consequences for his future well-being. “You just won $1 million dollars in the lottery” is in most situations presumably more relevant to him than “the milk has gone sour.” Balancing the “benefit” side, however, is the “cost” side of interpreting a message. If two messages yield the same interpretation, the one that requires the least mental effort is the more relevant one.

Relevance theory furthermore differentiates between explicit and implicit aspects of messages. Explicit information only requires decoding. For example, the following sentence provides all the necessary information for a full understanding: “Willem Alexander of Orange was crowned king of the Netherlands on 30 April 2013.” By contrast, implicit communication expects the addressee to combine the message with situational and/or background knowledge to infer what the communicator wanted to convey: “He will appear soon.” Who will? Appear how? How soon? We don’t know, but that does not matter—as long as Peter does; and Mary expects him to do so, on the basis of her hopefully correct assessment of his background knowledge and appreciation of the situation at hand.

I propose that the relevance principle holds with undiminished force for mass-communication of the visual and visual-plus-written-text variety. Genre plays a fundamental role here.

Since the search for relevance is probably evolutionarily hard-wired in all animate creatures, let me here briefly venture into a discipline far from my own and chance the following idea: insofar as animals communicate with one another, they do so on the basis of the relevance principle no less than humans do.

The primatologist Frans de Waal frequently uses the word “communication” to describe chimpanzees’ behavior toward each other. In relevance theory terms this means that one chimpanzee wants to convey information, or an emotion, to one or more conspecifics on the assumption that the latter will find processing this information worth their while, that is, find it relevant. The communicator will select the best possible behavioral stimulus—a sound, a grimace, a gesture, a posture, a movement, or a combination of these—to achieve this, as Jared Taglialatela et al. have evidenced. The mutually clear context helps specify the meaning of any communicative signal, as De Waal observes:

Apes move and wave their hands all the time while communicating, and they have an impressive repertoire of specific gestures …. When a chimp holds out his hand to a friend who is eating, he is asking for a share, but when the same chimp is under attack and holds out his hand to a bystander, he is asking for protection. He may even point out his opponent by making angry slapping gestures in his direction.

Another incident reported by De Waal pertains to an alpha male, Jimoh, pursuing a younger male in the group, intending to punish him.

Before [Jimoh] could reach this point, however, females close to the scene began to woaow bark. This indignant sound is a warning call against aggressors and intruders. … Once the protests swelled to a crescendo, Jimoh broke off his attack with a wide nervous grin on his face: he got the message.

In relevance theory terms, the females’ woaow bark is explicit information, decoded by Jimoh as “there is an aggressor.” However, the situational context makes clear that it is him who is the addressee of the barking and brings him to infer the implicit message that it is he himself whom the female apes consider to be the aggressor.

De Waal argues that many researchers studying animal communication insufficiently take into account that animals have species-specific ways of communicating, wrongly expecting other species to communicate in the same ways as humans: “Only by testing apes with apes, wolves with wolves, and children with human adults can we evaluate social cognition in its evolutionary context.”

While some communicative behavior verges toward the explicit pole (say, a threatening posture, a warning cry), other varieties are more implicit, which means that the behavior achieves relevance because the addressed animal combines the incomplete information provided by the communicating animal with pertinent background assumptions and crucial contextual circumstances that are crystal clear to both of them—and therefore need not be spelled out.

Relevance theory thus can help ground De Waal’s view that chimps (and other animals, such as elephants) communicate in species-specific ways, using various non-verbal signals to inform their conspecifics of something fairly precise that they presume these fellow chimps find relevant.

Featured image by Alexas Fotos via Pixabay

The post Rooting chimp communication in relevance theory appeared first on OUPblog.

October 5, 2020

MI5 and Russian interference, now and then

On 21 July 2020, the UK parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee published its long-delayed report on “the Russian threat to the UK.” Although heavily redacted, the report was wide-ranging and dealt with a number of issues, including the threat to democracy, highlighting concerns about potential Russian interference in the Scottish referendum in 2014, the EU referendum in 2016, and the general election in 2017. But not only was the Committee concerned by the threat to democracy presented by Russian activities, it was concerned too by the government’s failure to investigate and respond, as well as by the failures of various agencies to defend the UK’s democratic processes, a matter seen as “something of a ‘hot potato’.”

One of the agencies in question was the Security Service (MI5). In the view of the Committee, the “operational role” for protecting “our democratic discourse and processes from foreign hostile interference” must “sit primarily with MI5.” This is because of MI5’s statutory responsibility for “the protection of national security and, in particular, its protection against threats from espionage, terrorism and sabotage, from the activities of agents of foreign powers and from actions intended to overthrow or undermine parliamentary democracy.” According to the Committee, MI5 was not sufficiently engaged with the protection of British democracy, constrained by the difficulty of dealing with the Russian state.

All this has a very familiar ring and indeed we draw parallel conclusions historically in our new book on MI5, the Cold War and the Rule of Law, focusing on the period from the election of the Attlee government in 1945 until the collapse of the Macmillan/Douglas-Home government in 1964. Since 1946, MI5 has had responsibility for the Defence of the Realm, including, specifically, counter-espionage and counter-subversion. But it is clear that the Service found the former a difficult nut to crack, preferring to spend most of its time during the Cold War on political policing and the pointless task of maintaining the most impressive Registry and filing system of Communist Party members and associates.

This information was obtained covertly, without any specific legal authority and sometimes by dubious means. It was pointless because the British Communist Party was not an espionage threat, and would have no truck with those who sought to pass secrets on to the Russians. In any event, London-based Soviet agents were under strict instructions to have nothing to do with the Party. The result of MI5’s hopelessly misdirected efforts was a series of catastrophic counter espionage failures which punctuated the Cold War, as revealed by Alan Nunn May, Klaus Fuchs, and the Cambridge spy ring respectively; and later by the Portland Spy ring and the Vassall affair, exposing Soviet penetration of the British defence establishment.

Apart from MI5’s failure to discharge duties set out in its Charter issued originally by Attlee (in 1946) and then in bowdlerised form by Conservative Home Secretary Sir David Maxwell Fyfe (in 1952), the other striking parallel is the lack of any effective ministerial supervision to ensure that what are now statutory responsibilities are carried out. By virtue of the Security Service Act 1989, MI5 is said to be “under the authority” of the Home Secretary. This reflects the change made in 1952 when the Service was transferred from the responsibility of the Prime Minister to the then Home Secretary, mainly it seems to spare Churchill from having to answer in Parliament for MI5’s failings, a transfer of function that proved disastrous.

Thus although initially unhappy with the transfer of responsibilities in 1952, MI5 quickly warmed to Maxwell Fyfe when it became apparent that he was to let them off the tight leash on which Attlee had held them. The result was that the Service won what its Director-General Roger Hollis said in 1961 was “glorious independence.” The extent of that independence from any form of ministerial supervision or accountability was exposed by the Profumo Affair which hit the headlines two years later. It seems that neither the Home Office nor the incumbent Home Secretary Henry Brooke were fully aware of their constitutional responsibilities for MI5, which liaised with the Cabinet Secretary instead.

It is likely that the current Home Secretary is better briefed than her predecessor, though the recent reports that she is unaware of the difference between “terrorism” and “counter-terrorism” does little to inspire confidence. The Intelligence and Security Committee has, however, exposed much greater failings at both political and operational levels. By a remarkable twist of events, the old Cold War enemy has redoubled its espionage campaign against the UK. Moreover, not only are the Russian intelligence services spying, but they appear to be using chemical weapons against those they consider to be their enemies on UK soil, as well as “interfering in Parliamentary democracy.” This is subversion writ large, and worse.

For MI5 during the Cold War, subversion was a euphemism for left wing politics and trade union activism—it was a catch all phrase for the arguments and policies of those at odds with the governing parties. Now it seems very likely that we have the real thing in the form of foreign agents interfering with our political processes to the benefit—intended or not—of the right wing of the Conservative Party. Like the Intelligence and Security Committee, we can understand “the nervousness around any suggestion” that security agencies “might be involved in democratic processes.” Unsurprisingly, MI5 files on parliamentary candidates and MPs reveal no such nervousness in dealing with misplaced concerns about subversion during the Cold War.

Featured image by geralt via Pixabay

Article originally published by UK Constitution Law Association

The post MI5 and Russian interference, now and then appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers