Oxford University Press's Blog, page 128

October 28, 2020

A “baker’s dozen” and some idioms about food

I decided to write this post, because I have an idea about the origin of the idiom baker’s dozen, and ideas occur so seldom that I did not want this opportunity to be wasted. Perhaps our readers will find my suggestion reasonable or refute it. I’ll be pleased to hear from them. Also, since a baker’s dozen presupposes an extra loaf, I too decided to add more food idioms.

This is what Walter W. Skeat wrote in 1862, many years before he began work on his great English etymological dictionary:

“I do not know if the following passage in the Liber Albus [The White Book of the City of London by John Carpenter, a compilation of laws, ordinances, and regulations related to the City of London, 1492] has been noticed. It occurs on p. 232 of the translation by Mr. [Henry T.] Riley: ‘And that no baker of the town shall give unto the regratresses [female retailers] the six pence on Monday morning by way of Hansel-money [gift], or the three pence on Friday of curtsey-money; but, after the ancient manner, let him give thirteen articles of bread for twelve’. That is, the retailers of bread from house to house were allowed a thirteenth loaf by the baker, as a payment for their trouble.”

As Skeat explained later, to give (offer) thirteen to the dozen “to offer a reward for a deal or for one’s pain” may have originated in bakers’ trade. I find Skeat’s idea eminently reasonable.

John Carpenter (a. 1372-1442). (Image by B. Darling, MISM, City of London School)

John Carpenter (a. 1372-1442). (Image by B. Darling, MISM, City of London School)The other explanations of the idiom appear in numerous books and on the Internet. The most popular of them states that bakers were severely punished for selling short weight and preferred to give their customers an extra loaf, to be on the safe side. I have not been able to find what documents confirm this explanation. It goes back to Riley’s commentary (see the quotation in the OED’s Second Edition), which was repeated by E. Cobham Brewer, the author of the most widely used book of English words and phrases. Unfortunately, the authors of popular books (and this also holds for Brewer) never give references to their sources, and therefore I suspect that they copy from one another. Multiple repetition acquires the status of common knowledge.

The phrase the printer’s dozen also existed and has been cited as the model for baker’s dozen. In the early days of publishing, it was the custom of printers to supply the retailer with thirteen copies of a book on each order of twelve. Assuming that this custom existed (a custom reminiscent of the one Skeat mentioned!), is it known that the phrase printer’s dozen antedates baker’s dozen? Has the interaction between those phrases been traced? Finally, we are told that the bakers of the medieval period had such a bad name that the words baker and devil were sometimes used interchangeably. The three explanations quoted above can be found in the book by William and May Morris Word and Phrase Origins (a moderately reliable work). Did bakers really have a proverbially bad name? Are we back at the first of the three hypotheses?

Yet I think that the confusion of baker and Devil can indeed be documented. In the post published on May 20, 2020, I discussed the phrase pull Devil, pull baker. This phrase goes back to a puppet show that was known as far back as the days of Shakespeare. According to the OED, baker’s dozen first occurred in print in 1596, that is, also in the Elizabethan period, and here comes my idea. Some Germanic and Romance languages have no special name for thirteen, while others have. When such a name exists, the reference is always to things gone wrong or to some devilry. The phrase Devil’s dozen must have been well-known because it also reached Russian (chertova diuzhina), while baker’s dozen is, to the best of my knowledge, uniquely English. Judging by the puppet show, the Devil and the baker were a familiar couple. Is it possible that baker’s dozen is a facetious alteration of the older variant Devil’s dozen (under the influence of both the show and the old custom, referred to by Skeat)? The new idiom lost the alliteration (d ~ d) but appealed to people’s sense of humor.

Angels on horseback. (Image by Food Stories)

Angels on horseback. (Image by Food Stories)And now, as promised, a few food idioms for dessert. Angels on horseback: “oysters rolled in bacon and served on toast.” The phrase also occurred (rarely) “as a species of mock-heroic commendation.” In Winchester, that is, in Winchester College, it denoted excellence (1898-1899). The phrase and especially the dish never lost their popularity. Brass knockers: “the next day remains of a dinner party.” According to some knowledgeable people, this was a folk-etymological alteration of Hindustani basi “cold” and khana “food, dinner” (1878). Bubble and squeak: “fried beef and cabbages.” According to a cook who was asked about the phrase, the dish ought to be made of boiled beef and cabbage fried, and she supposed it acquired that name from the ingredients in the first instance bubbling in the pot, and afterwards squeaking in the pan. My authority is The Gentleman’s Magazine for 1790, but the OED has a 1762 citation. Wikipedia gives a somewhat different explanation of the idiom, but, regardless of etymological niceties, the dish is still widely known.

Bubble and squeak. (Image by Indiana Public Media)

Bubble and squeak. (Image by Indiana Public Media)Sunday side: “the undercut of a sirloin of beef.” The phrase was very common around the 1880s, probably owing to Thackeray’s allusion to it. (Today, it is hard for us, who at best know only Vanity Fair, to imagine Thackeray’s popularity during his lifetime.) The application of the term to this part of the joint is, as a correspondent, whose 1903 note I am quoting, says, unmistakable. In small families, where economy was desirable, the joint was roasted for Sunday, and the undercut eaten hot on that day—the other side being cold meat for the rest of the week. By leaving the “weak side” uncarved when hot, it was rendered more juicy and palatable as a cold collation. The OED has Sunday joint (1844) and Sunday roast (1826), but, apparently, no Sunday side. Tea and turn-out: “a light meal after which one was expected to leave the table.” In this phrase, turn-out means “leave.” The old-fashioned people were reluctant to reconcile themselves to the afternoon tea, a habit that replaced a more substantial meal, and the phrase contained a note of disapproval. Such was the commentary in 1911. The OED found this phrase as early as 1806!

We have the expression meat and potatoes man: “an unpretentious man of simple habits.” Three centuries ago, a fiddler who played at local events and dined on leftovers was called a rump and kidney man. Another archaic phrase is more pleasant. Rump and dozen refers to a good dinner: a steak and twelve oysters or perhaps a dozen bottles of wine (a regular, not a baker’s dozen). And one more idiom along the same lines. Cry roast meat meant “to be foolish enough to proclaim one’s success.” I have been unable to find the idiom’s origin. Was roast meat such a luxury (see what is said above about Sunday side!) that someone who could partake of it was advised to do so in secret, in order not to arouse the neighbors’ envy? Rather curious is the alliterative taunt cowardly, cowardly custard. I am aware of only one suggestion: the phrase allegedly has its origin “in the shaking, quivering motion of the confection called custard.” What can I offer you by way of apology for this post? Adam’s ale? Alas, it means “water.” After meat—mustard? This is said about something that comes too late. I’d rather refrain from apologizing and let you enjoy my Wednesday joint.

Feature image by Zane Selvans

The post A “baker’s dozen” and some idioms about food appeared first on OUPblog.

October 27, 2020

Voter fraud and election meddling [podcast]

Next week, over a hundred million Americans will vote to elect the next President of the United States. After a year of political turmoil, mass protests, and a pandemic that drove daily life (and the US economy) to a halt, many are now wondering: will the electoral process go smoothly, or does 2020 have another shock in store for us?

The topic of voter fraud and electoral meddling has been at the forefront of many a conversation over the last four years, as the attempt by Russia to sway the 2016 election and Donald Trump’s electoral college victory and popular vote loss are still vivid memories. How will this year’s election go? Are foreign powers trying to sway our election again? Is mail-in-voting safe from meddling? Will fear of COVID-19 decrease voter turnout?

Our episode of The Oxford Comment today features interviews with scholars who specialize in electoral intervention, voter turnout, and voting laws. Caroline Tolbert and Michael Ritter, co-authors of Accessible Elections: How the States Can Help Americans Vote, and Dov Levin, author of Meddling in the Ballot Box: The Causes and Effects of Partisan Electoral Interventions, answer our questions about voting and offer solutions for the safety and security of this election and elections in the future.

Featured image credit: @tiffanytertipes CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Voter fraud and election meddling [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

Emo-truthful Trump-Biden 2020: another post-truth election

The US Presidential Election 2020 is the COVID-19 election saturated with post-truth political communication. While the presidential campaign necessarily breathed and belched the air of post-truth politics from its inception, the first week of the campaign’s final month, 27 September-3 October, took post-truth to new levels of intensity and showcased the concept’s multiple forms. They ranged from bullshit to rumor bombs, conspiracy theories, fake news, and lying, which, as I’ve explained, issue from and help reproduce a culture of generalized political distrust, paranoia, and panic, at home in a larger promotional culture of incessantly pervasive artifice.

The first Trump-Biden debate occurred on 30 September 2020. The day after, major American and global news brands (from CNN to the BBC) were awash with striking headlines and subsequent text accusing Trump of lying and of demonstrating a historic level of incivility in the debate. The episode came only three days after the New York Times broke a potentially scandalous (for almost any past presidential election) story that the boastful billionaire paid a mere $750 in income taxes (and in some previous years paid none at all). The debates also came three days before Trump publicly admitted that he and his wife had contracted the coronavirus (and after months of his playing down the gravity of the pandemic). The world repeatedly heard him refusing to unequivocally support medical professionals’ advised mask-wearing and social distancing, while he bandied about half-truths concerning the virus’s origins, character, and preventions. Earlier in the day, before reports that POTUS and FLOTUS tested positive for the coronavirus, news outlets around the world reported a new Cornell University study found Trump was a superspreader: “the single largest driver” of misinformation in the “infodemic” between January and June 2020.

Post-truth in digital era presidential campaigns does not begin with Trump. In the 21st century, it dates at least as far back as the 2004 Bush-Kerry election, in which the infamous Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, insisted Kerry lied about his decorated war record in Vietnam (not without 20th century prototypes). The accusations were discredited but perhaps after it was too late and after they had preoccupied a significant bloc of swing voters. People need not believe such disinformation is true; it is politically efficacious enough to preoccupy and confuse them, make them suspicious of someone or some group, distract and refocus them. What perhaps makes Trump unprecedented in this recent history of post-truth strategies and performances is that the disinformation was formerly coming mostly from surrogates (groups or people not directly working on the candidate’s campaign), even if a heartbeat away from the president, as Bush’s vice president Dick Cheney on several occasions made misleading and false claims that Iraq had direct links with Al Qaeda or that there was proof of Weapons of Mass Destruction.

While each major post-truth spectacle of the week beckons analysis, a reflection on the debate’s post-truth qualities and its mediated afterlife merits special attention. In general, moderator Chris Wallace tried in vain to restore yesteryear debate standards, expectations, and practices (themselves time-worn with staged authenticity, question avoidance, and talking points), while Trump constantly interrupted and talked over his opponent, and each candidate exchanged playground insults—all characteristic of what I’ve called an aggressively masculinist post-truth political style, “emo-truth”, where aggressive traditional masculine communication qualities are confused with honesty and accuracy. While factcheckers also criticized Biden for his errors, strategic (disinformative) or not (misinformative), Trump’s overall performance (his style and claims) was more spectacularly emo-truth than Biden’s. But it was also the mediated afterlife of the debate (attempts to frame what happened and what it meant) that radiated post-truth.

One of post-truth political communication’s most prominent features is the constant accusation of lying and lies, potentially constituting for those listening to such claims a public sphere whose epistemology is emptied by distrust. Consider this experiment. In Paris, changing my VPN(secure IP address) to Washington, D.C. and googling “Trump-Biden debate factcheck,” I get, in order of appearance, stories by the following ten sources: apnews.com; cnn.com ; Washingtonpost.com; bbc.com; factcheck.org; usatoday.com; chicagotribune.com; cbsnews.com; nytimes.com; poynter.org—to report only the top ten hits. First observation (yes, captive to the google algorithm and its implicit ordering of importance): traditional news organizations (print, TV and radio broadcast) compete for trust and attention with highly visible, public service non-profit factchecking sites. (Via VPN, a shift from a Washington D.C. IP address to one in Los Angeles produced nearly the same google results, cache/cookies also cleared). Trust is the autobahn to acceptance of truth claims (the objects of which one often knows very little about—such as, say, energy policy).

Another observation: headlines are part of the ongoing infotainment trend in news values that inevitably makes journalism a casualty of the attention economy. These headlines are an extension of the paradoxically sensationalist ratings of popular US factcheck organizations or sites, such as Washington Post’s “Fact checker,” whose categories of evaluation range from the dullish “True” to the metaphorically provocative “Pinocchio”; and Pulitzer Prize-winner Politifact’s similar scale of sensational verification, “True” to “Pants on Fire.” These rubrics of truth adjudication themselves entail unproven or unprovable, if exciting, accusations of lying—its sensational presentation indicating that truth is also a commodity (thus I speak of “truth markets”); or as the New York Times’ marketing campaign goes: “The Truth is Worth It.” Clearly, such a slogan would be absurd in an economy of seeming truth abundance. Nonetheless, it’s one thing to demonstrate a claim is false; it’s quite another to prove it is intentionally so. If Trump is an inveterate purveyor of falsehoods, it’s not always clear whether he’s a bullshitter, liar, or strategic misleader who is simply more flamboyant and frequent in his statements than the thousands of politicians who hire consultants in order to master the art of deceptive political communication. (Note: “bullshitter,” if you’re perplexed, is also an academic concept, meaning someone who is not necessarily intentionally telling falsehoods; they just don’t care whether the statement is true or false).

Witness the telling headlines:

Washington Post : “Belligerent Trump debate performance stokes fears among Republicans about November.”CNN: “Trump unleashes avalanche of repeat lies at first presidential debate.”Associated Press: “AP FACT CHECK: False claims swamp first Trump-Biden debate.”Inference and judgments (“belligerent Trump,” “stokes fears,” “repeat lies,” “false claims”) saturated these provocative headlines. They were accompanied by news organizations with comparatively blander headlines, appealing to more traditional expectations (public and professional) where journalism performed a rhetoric of objectivity. The branding implication: you can trust the palpably bland. Thus, ABC News’ “Fact-checking Trump and Biden during first 2020 presidential debate” was in the same vein as USA Today and Factcheck.org. Interestingly, the Star Tribune’s apparently neutral headline, “AP FACT CHECK: False claims swamp first Trump-Biden debate,” was followed by a provocatively judgmental hook: “President Donald Trump unleashed a torrent of fabrications and fear-mongering in a belligerent debate with Joe Biden.”

The post-truth nature of the debates and their coverage (including social media platforms, and those posing as such while issuing from well-funded disinformation sources) is reinforced by a consistent set of stimulating primary and secondary (mediated) expressions, each one in part becoming cultural context for the next. Thus, responses to news that Trump was corona-positive was met with generalized distrust. “‘I don’t believe it,’ said Anthony Collier, a truck driver from Atlanta,” who was among several such skeptics featured in a New York Times article on the topic. True, that is in response to Trump, who attracts extremes of automatic belief and disbelief, but a difficult question faces those of us brave enough to entertain it: is generalized distrust for the political culture really unreasonable? “Across social media, in interviews, in conversations, the questions poured in all day from people who have heard so many contradictory things over the last four years—a warp-speed whiplash of conflicting realities—that they no longer know what is true,” the Times reasoned.

The week of post-truth overload went out with a whimper—or was it a bang? On Saturday evening (3 October), Trump posted a four-minute rambling video from the hospital, in which he attempted to convince the public that he was improving after a day of “contradictory messages” about it from the White House. “When I came here, wasn’t feeling so well, I feel much better now,” he said. As if always trying to convert a grammatical conditional into a declarative (emo-) truth through the very authority of the performance he continued: “I’ll be back, I think I’ll be back soon, and I look forward to finishing up the campaign the way it was started and the way we’ve been doing and the kind of numbers that we’ve been doing,” he asserted, then doubted, and then hoped, capped off with a brag. Showing the consistent traditional boldness that his supporters confuse for truthfulness, Trump went even further on Sunday 4 October, organizing a joyride to show he was beating the virus (and anyone or anything else that dared to cross him), which Secret Service agents and Walter Reed Hospital doctors called “careless” and “insane.” But post-truth political communication shares with reality TV this aspect: careless or insane, for a significant portion of citizens, is true. It is also, as I’ve argued elsewhere, where post-truth communication and toxic masculinity intersect. There is something palpably egotistical, traditionally, masculinely boastful about this kind of post-truth communication.

Thus, the new week began much as the previous one (and so many in recent memory). Monday evening (5 October) Trump was back in the White House and back on Twitter, back to bullshitting, back to creating controversy, back to superspreading, perhaps in a double sense. A few hours before he left the hospital, he tweeted that he felt “really good,” and then was back to downplaying the danger of the virus, advising followers, “Don’t be afraid of Covid. Don’t let it dominate your life.” Still fully contagious, upon arrival at the White House, he removed his mask for photos, outraging medical professionals and concerned citizens. Reports continued to question his real health status, despite his words and actions (he had received supplemental oxygen twice over the weekend and was “not out of the woods,” the White House physician admitted).

By 6 October, Tuesday afternoon, where this extended vignette of the campaign ends, in a tweet Trump had once again compared COVID-19 with the flu (the latter of which he claimed was more lethal). Facebook blocked his post immediately, saying it forbids “incorrect information about the severity of COVID-19, and have now removed this post.” Twitter also hid the tweet, announcing that it “violated Twitter rules about spreading misleading and potentially harmful information related to Covid-19”—but only after 59,000 retweets and 186,000 likes. Trump further self-promoted that he was looking forward to debating Biden in Miami next week. In a flashback to the 2016 election where Trump dominated news coverage, a convenience sample of news websites (New York Times, The Guardian, The Washington Post) showed Biden getting very little attention on all of these sites, The Guardian US site being the most flagrantly unequal: Trump’s name appeared 52 times on the landing page, Biden’s but thrice. As Trump knows: bad news may be good news.

This has been a vignette of the 2020 campaign: a spectacular example, yet arguably an illustration of its general style. Whether or not Trump wins (or survives the coronavirus), judging by his consistent support in polls with nearly 30% of the voting public having long supported him no matter what he does or says, the emo-truth sub-category of post-truth political performance may influence politics for the foreseeable future. As we’ve seen with variations on Trump’s aggressively masculinist post-truth communication with Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and the UK’s Boris Johnson, and even with his opponent Biden to some degree (which is probably why he’s the last tough old white “emo-dude” standing), the trend is not limited to the US nor to the far right. Only a more multi-causal, culturally and historically sensitive analysis of post-truth politics will help us demand a different culture of truth production, recognition, and trust—and campaigns that rely on them. Meanwhile, post-truth is the context for post-liberal democracy.

Featured image by Element5 Digital

The post Emo-truthful Trump-Biden 2020: another post-truth election appeared first on OUPblog.

October 26, 2020

The essential role of music therapy in medical assistance in dying

In Western society, we spend a lot of time celebrating and welcoming new life, but very few cultures celebrate when a person dies. While death is not as taboo as 50 years ago, death is still a topic that many individuals are not comfortable speaking about in conversations. Even more off-limits, people are less likely to talk about physician-assisted suicide in their social circles. There are many reasons to this phenomenon such as religious beliefs, personal beliefs, and advocacy for life. In fact, an ethical challenge is the conundrum of ending a life, as these professionals strive to enhance the quality of life and cure or alleviate illness, rather than to end it.

What constitutes a good death? To answer this question, several common responses include: being surrounded by family and friends, avoiding the prolongation of death, not being in pain, and achieving control. But what happens to the patient when the suffering becomes too much? Who determines the suffering is great enough to warrant suicide? How does the medical community ensure an individual is cognizant of their choice to end their life? These questions can be considered in conversations about Medical Assistance in Dying.

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD), as described by Noushon Farmanara, is a process that permits individuals with grievous and incurable physical or psychological suffering to voluntarily end their life in the presence of medical and health professionals. At present, MAiD is legally available in Europe, South America, Australia, and North America. Particularly in Canada, the passing of Bill C-14 on June 17, 2016 permitted MAiD as a legal procedure for Canadians who meet rigid requirements. Although Bill C-14 advocates the legalization of assisted suicide in Canada, there are ethical implications to consider in the perspective of the patients, the medical and healthcare professionals, as well as the community, who may be affected by the legislation.

Music therapy, an allied healthcare discipline that is growing in its awareness and significance in hospice and palliative care, is essential in helping patients explore the meaning of a good death as they move through their decline. Music therapists may be called to provide music and holistic care for the patients prior to MAiD, as it is a logical extension to include music therapists in the discussions and procedures of MAiD.

The clinical interventions facilitated by certified music therapists are spread across a continuum of passive to active interventions such as lyric discussion and analysis, songwriting, improvisation, guided imagery and music, and musical life review. The techniques that assist in the realization of patient-directed goals exist in spiritual, psychosocial, cognitive, emotional, and physical domains. As well, patients can create legacy songs to convey an important sentiment for their loved ones to cherish and listen to after their passing, such as “I love you.”

Music can also offer potential interventions which can keep a patient calm and relaxed at the time of injection. While Bill C-14 does not include music therapists as a valid healthcare professional in MAiD, having these holistic approaches can allow the patient to feel safe and celebrate their life. In fact, the absence of music therapy could increase the potential for harm as music therapy can contain and support emotions that might be very intense at this time.

A hypothetical case example followed a patient in a Canadian public-hospital who was considering live music by a music therapist during her MAiD procedure. As her physical symptoms worsened and despite the intake of medications, music therapy potentially offered healing and autonomy for her physical suffering in this difficult time. As music is non-invasive, it provides a creative outlet for patients to document their internal feelings, relationships, and stories prior to their death.

When integrating music therapy with MAiD, ethical considerations should be explored, such as recommended policies and guidelines that could promote music therapists as an essential to legalized death. As these professionals use music as a holistic intervention to clients, the facilitator may experience emotional hardship similar to the medical professionals in MAiD. This may result in immediate replacements and strain in the client-healthcare relationship. Further, limited resources are currently available to healthcare professionals to engage in circumstances around MAiD.

To provide these viable solutions, a team of music therapists and psychiatrists have written a set of clinical guidelines for music therapists to effectively engage with patients interested in MAiD. These guidelines explore the potential of music therapy in MAiD through an evidence-based methodology of qualitative studies and recommended practices that were designed to address the dynamic nature of Bill C-14 and the Code of Ethics of the Canadian Association of Music Therapists. This included suggested interventions and clinical goals for the patient, as well as supportive roles in the music therapy sessions. Further, annual hospital training and education for re-certification of any healthcare profession may be viable options to explore resources available for patients at their time of death.

Music therapy is a natural fit with MAiD as this healthcare discipline has demonstrated significant impact in work with the dying. In Canada, while Bill C-14 has provided patients with a degree of autonomy, it has created ethical concerns for the medical and healthcare professional and their community. To address these concerns, policies and guidelines have recommended music therapy as a crucial practice in the dying process and have provided viable solutions to combat these restrictions through empirical research. By continually creating resources about MAiD, the conversations about this topic will diminish its taboo and, ultimately, visualize death as a celebration of life and care.

Featured image: “Piano Music Score” by stevepb

The post The essential role of music therapy in medical assistance in dying appeared first on OUPblog.

Is gerrymandering “poisoning the well” of democracy?

Every ten years, the federal government administers the Census to determine the size of the population as well as how that population is distributed within and across states. These figures are then used to allocates seats within the US House of Representatives. States that grow faster than the rest of the country typically gain seats, necessarily at the expense of states that have lost residents or have experienced the slowest growth. Even states that do not gain or lose seats still witness shifts in their population, with urban areas normally growing faster than more rural ones. Therefore, states must redraw their congressional boundaries to ensure equal populations within districts.

However, this process is often used to satisfy partisan ends. The majority of states within the US empower their legislature to craft district boundaries. Therefore, whichever party wins a majority in the state legislature has considerable power to determine a party’s chances of winning a federal seat in subsequent elections. This process, called partisan gerrymandering, has led to a common refrain among disaffected citizens: politicians are choosing their voters instead of voters choosing their politicians.

In response to this, many states have moved away from legislature-based redistricting. One of the most common alternatives is the implementation of a redistricting commission. In 2018 alone, five states passed amendments or initiatives that either created commissions or at least curtailed the power of the state legislature with respect to redistricting.

What can we expect as a result of this change? Some scholarship suggests that taking the power to draw districts away from state legislatures results in more competitive elections, more open seat races, more experienced candidates, fewer uncontested elections, more compact districts, and districts that better respect existing political boundaries like city and county lines.

However, there is not a consensus on the matter. Other research suggests that commission maps are not considerably different from legislature-based alternatives that could have been enacted, geographic sorting and partisan polarization present too much of a hurdle for commissions to have an effect, or that any observed differences between commission and legislature-drawn districts disappear throughout the ten-year lifespan a redistricting plan.

Nevertheless, many citizens today have exhibited displeasure with the redistricting process. Recent polls have demonstrated considerable disapproval for the practice of gerrymandering, as shown in the chart below. Strikingly, this negative view is not only overwhelming but consistent across partisans and independents as well.

The US Supreme Court has heard many cases related to partisan gerrymandering, but consistently argues that it presents a political question that cannot be adjudicated by the Court. What does this mean for the next redistricting cycle? Partisan gerrymandering will continue to pervade some states’ plans, calls for reform will continue, and citizens’ dissatisfaction is likely to grow.

What does citizen satisfaction matter? Evidence suggests that voters are more trusting and overall more satisfied with government and elections when they view the process as legitimate. Therefore, regardless of whether or not commission-based plans produce significantly different electoral outcomes, voters may be more accepting of those outcomes if the commission provides them with added legitimacy.

Another important question that has received recent attention is how to count the incarcerated population. In most states, incarcerated individuals are counted as residents of the districts that house the prison instead of the individual’s home address. However, nine states have outlawed prison gerrymandering, and seven of those states will draw maps counting incarcerated individuals at their home address for the first time during the 2020 redistricting cycle.

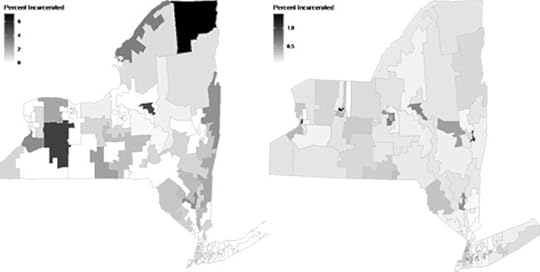

Substantial research exists showing how prison populations are used to skew representation away from urban areas in favor or more rural ones. The maps below illustrate how New York’s ban on prison gerrymandering altered the distribution of incarcerated residents across the state. As such, we can expect substantial changes in the electoral environment in other states that have enacted similar reforms.

Percentage of Incarcerated Persons in New York State Assembly Districts (L) Before the Prison Gerrymandering Ban, (R) After the Prison Gerrymandering Ban

Percentage of Incarcerated Persons in New York State Assembly Districts (L) Before the Prison Gerrymandering Ban, (R) After the Prison Gerrymandering BanIn the current climate—marked by effective polarization, negative partisanship, misinformation, disinformation, and low approval of individual politicians as well as government institutions as a whole—there are likely going to be hard fought battles, legal and political, over congressional district boundaries. The results of these battles will carry important consequences for who runs and wins in these elections, the policy these officials ultimately create, as well as the overall attitudes of citizens towards their government.

Featured image by Jonathan Simcoe

The post Is gerrymandering “poisoning the well” of democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 25, 2020

The fight against fake news and electoral disinformation

Just as COVID-19 is a stress test of every nation’s health system, an election process is a stress test of a nation’s information and communication system. A week away from the US presidential election, the symptoms are not so promising. News reports about the spread of so-called “fake news,” disinformation, and conspiracy theories are thriving as they did in 2016.

Disinformation and “fake news” are not new, but the 2016 US presidential election placed the phenomenon squarely onto the international agenda. The spread of false and manipulated information dressed as news is closely associated with social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. In a 2018 study, researchers examined the exposure to misinformation during the American election campaign in 2016; they found that Facebook was a key vector of exposure to fake news.

It becomes harder to differentiate between false and trusted information when supposedly everyone can publish and spread information online that looks like news to large groups of people. The spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories has been identified as a problem in several states, for example in Florida, and news publications, such as the New York Times, are daily tracking viral misinformation ahead of the 2020 election.

While disinformation and foreign influence was of great concern in the 2016 election, disinformation from domestic sources is additionally reported as a major threat in the 2020 US election. The spread of fake new, rumors, and conspiracy theories is problematic in itself, but the main damage of such orchestrated campaigns might be the systematic erosion of citizens’ capacity to recognize facts, the undermining of established science, and the sowing of confusion about what is real or not.

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how a health situation dominated by uncertainty and the lack of a vaccine makes the rumor mill turn faster than ever. A new study by the Oxford Internet Institute and the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism reveals that coronavirus-related misinformation videos are predominantly disseminated through social media and that Facebook is the primary channel for sharing misinformation due to a lack of sufficient fact checks in place to moderate content. Another study found that one in four popular YouTube videos on the coronavirus contained misinformation, while more than 1,300 anti-vaccination pages on Facebook had nearly 100 million followers.

Countering disinformation and fake news has become such a major issue that international institutions such as the United Nations, the European Union, the World Health Organization, and the World Economic Forum have published reports and recommended actions for how to tackle disinformation, particularly electoral and health disinformation. In June 2020, more than 130 United Nations member countries and official observers called on all states to take steps to counter the spread of disinformation, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, tackling false and manipulated information is far from straightforward. It requires a complicated balancing act between countering disinformation and protecting freedom of speech. A report from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recommends how to avoid sacrificing freedom of speech in the fight against fake news and disinformation. The report warns against “quick fixes” such as “‘fake news’ laws” and other measures to curtail viral disinformation, which may end up censuring legitimate journalism or legitimate criticism of authorities.

The UNESCO report suggests four main measures to identify and address fake news, disinformation, and misinformation—of particular concern during election campaigns. The report suggests a range of measures, from policy and legislative approaches to technological efforts and media and education literacy initiatives, in order to identify the problematic information, its producers, the distribution mechanism, and its targeted audience:

1. Identification responses (aimed at identifying, debunking, and exposing disinformation)

Monitoring and fact-checkingInvestigativeDuring the US election, news media have conducted live fact checks of the presidential debates, and major hoaxes have been identified and debunked. But to identify and expose all disinformation spreading during the election campaign, particularly on social media, is hardly possible.

2. Responses aimed at producers and distributors (intended towards the altering of the environment that governs and shapes behavior, i.e. law and policy responses)

Legislative, pre-legislative, and policy responsesNational and international counter disinformation campaignsElectoral responsesBased on evaluation from independent fact checkers, Facebook and Twitter have marked electoral disinformation, including from president Donald Trump.

3. Responses aimed at the production and distribution mechanisms (pertaining to the policies and practices of institutions mediating content)

Curatorial responsesTechnical and algorithmic responsesEconomic responsesBots—automated Twitter accounts—are spreading disinformation and sowing division in America. A Carnegie Mellon University study found that nearly half of accounts tweeting about the coronavirus were likely bot, and as a response Twitter has unveiled new labels that will accompany misleading, disputed, or unverified tweets about the coronavirus.

4. Responses aimed at the target audiences of disinformation campaigns

Ethical and normative responsesEducational responsesEmpowerment and credibility labelling effortsSeveral organizations and groups are offering training and tools both for citizens and journalists to increase skills in fact checking and verification. One of them, the project First Draft, offers tools and training to build resistance against misinformation.

Electoral disinformation is of specific concern because it can damage democratic processes and reduce citizens’ rights. Electoral responses to disinformation can thus include a range of real-time detection, such as election-specific fact checks, election ad archives, as well as debunks, counter-content, and retrospective assessments. They can also entail campaigns linked to voter education and regulations about electoral conduct.

The health of a democracy’s information system is critical, especially during election campaigns. By applying some or all of these measure during the US election, as well as other election campaigns in the near future, it might be possible to protect democratic elections from disinformation and increase citizens’ capacity to recognize facts.

Feature image by Kayla Velasquez

The post The fight against fake news and electoral disinformation appeared first on OUPblog.

What COVID-19 tells us about global supply chains

“These stupid supply chains that are all over the world, we have a supply chain where they’re made in all different parts of the world,” a frustrated Donald Trump exclaimed in May. “And one little piece of the world goes bad, and the whole thing is messed up.”

President Trump is not the only one bewildered by global supply chains today. Over the past 40 years, it has become normal for the production of many goods to be disaggregated and outsourced around the world. Transnational supply chains now represent 80% of global trade; they’re inextricable from our daily lives. Most people aren’t exactly surprised when their t-shirt comes from the other side of the globe or when their phone contains components from 43 countries, even if we can’t ever quite shake the feeling that there’s something uncanny about the contrast between these extraordinary distances and the ordinary purposes these goods serve.

Supply chains are supposed to be efficient; so-called “lean manufacturing” and “just-in-time production” means that goods are assembled as soon as consumer demand is anticipated, leaving little to no inventory sitting unused in warehouses. We can see the pervasiveness of these supply chains as part of the hegemony of neoliberalism, a political theory that sees efficient markets as the key to human freedom and wellbeing and accordingly makes creating and sustaining such markets the aim of politics. On this view, supply chains are an obvious boon to the common good because they exemplify the virtues of efficiency.

This rosy picture is incomplete, of course. Supply chains that pursue efficiency at the expense of all other values also predictably result in serious injustices. For workers, poverty wages, unsafe working conditions, and forced overtime are the norm. The 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh is emblematic: 1,132 garment workers who made clothes for global corporations like Walmart and Primark were killed when the building that housed their garment factories collapsed; at the time, many were earning the minimum wage, which was roughly $38 a month, while Walmart’s CEO took home $1.7 million a month. This outsourcing also predictably reduces wages for workers in the US, contributing to the ongoing growth of economic inequality. A global economy structured so that it’s profitable for Walmart to manufacture a t-shirt in Jordan and ship it to the US to sell for a retail price of $2 also isn’t environmentally sustainable; the UN Environmental Program estimates the global apparel industry is responsible for 10% of all carbon emissions.

Enter COVID-19. 94% of Fortune 1000 companies had a top tier supplier in the Wuhan region where the virus originated. Chains that were deliberately organized to have as little slack in them as possible came to a halt. Global trade flows dropped by 12% in April, in the wake of widespread shutdowns. In Bangladesh, more than 1 million garment workers were laid off; brands cut their orders without offering any severance pay or other support to workers suddenly left to starve. Meanwhile, in addition to massive unemployment, the US faced shortages of personal protective equipment like the N95 masks that protect wearers from airborne viruses, shortages that persist, in part, because the masks are not profitable to produce in the US and so are manufactured elsewhere.

Trump’s frustration at “stupid supply chains” that circle the globe thus reflects a neoliberal global economy that may be at a crossroads. Global supply chains that maximize efficiency at the expense of all else don’t seem sustainable as they are. But there are competing visions of what should come next.

Trump unabashedly pursues a nationalist economic vision, though it’s a mistake to see him as seeking to make the US independent of the global economy. The US cannot wave a magic wand and discover domestic deposits of the gallium needed to manufacture semiconductors, for example; it will continue to need resources from elsewhere. Consequently, Trump has formally declared this dependence a “national emergency” and, as a matter of national security, asserted that the US must dominate the countries where these resources are located. That is far from a vision of the US isolated from the world.

For their part, multinational corporations have unsurprisingly suggested that the solution is even fewer restrictions on capital mobility in the name of ever greater “flexibility” that would allow them to shift production from one country to another more easily in the event of a pandemic or a workers’ strike. This would lead to supply chains with “greater geographic diversity,” moving some production away from China and bringing more countries into supply chains without altering their fundamentally exploitative nature.

What’s needed today is neither resource imperialism nor a deepening of neoliberal precarity in the name of “supply chain resilience” but transnational solidarity founded on a shared interest in resisting and replacing a global economy that justifies worker exploitation and environmental damage in the name of efficiency. What makes supply chains today “stupid” is not that they circle the globe, but that they do so to the disproportionate benefit of the few. The global pandemic has brought into sharp relief not only the fragility of just-in-time manufacturing but also the fact that our dependence on and vulnerability to each other, economically, environmentally, epidemiologically, means most of us share common interests, while others benefit enormously from our current unequal arrangements. With the value and operations of global supply chains thrown into question by COVID-19, we may yet see transnational solidarity replace the neoliberal common sense that has prevailed for decades.

Feature image by NASA

The post What COVID-19 tells us about global supply chains appeared first on OUPblog.

October 24, 2020

The politics of punk in the era of Trump

Trump is Punk! It’s a hashtag. It’s a slogan on t-shirts and trucker hats. It’s a click-bait headline.

Milo Yiannopoulos, a former Breitbart editor, may have started this buzz with his speech (delivered in drag) at Louisiana State University on 22 September 2016, in which he claimed that “being a Donald Trump supporter is the new punk” because it would “piss off your teachers, piss off your parents, piss off your friends.” Then in October, The Atlantic published “Donald Trump, Sex Pistol: The Punk Rock Appeal of the GOP Nominee,” and after the election, the New York Post ran an opinion piece with the headline “Trump is the Punk-Rock President America Deserves” (9 November 2016). Despite social media protestations, “punk” became shorthand for Trump’s rule-breaking, anti-establishment campaign filled with unapologetic vulgarity and appeals to white male grievance.

Recently, a month before the 2020 election, photos of Johnny Rotten in a MAGA t-shirt set off a Twitter storm that revived the “Trump is punk” debate. Has Trumpism hijacked the meaning of punk like it has the Republican party?

The internet is warehousing a digital media archive that reduces punk to pissing people off—a caricature that belies the complexity and longevity of the political discourse embedded in punk’s confrontational style. Punk has been around for over forty years, and its material and musical archives offer ways to push back on the digital one.

Establishing the anti-establishmentPunk rock emerged in the mid-1970s as a rejection of bloated corporate rock stars who were out of touch with the lives of the late baby-boomers then coming of age. Its energetic back-to-basics music lowered the technical skills and financial requirements for kids to form a band. That’s one reason punk is described as “democratic.” Insofar as Trump represents a deskilling of the presidency—well ok, I’ll give that point to the “Trump is punk” folks.

However, Trump does not qualify as anti-establishment. He is a white man born into wealth, gifted a million dollars by his father to grow a real estate empire and a corporate brand. There’s not much scrappy Do-It-Yourself to that biography. Yes, he breaks established political norms, but he replaces them with autocratic ones—the polar opposite of punk’s rallying cry “Anarchy!”, which literally means without (an) a chief or ruler (arkhos).

To be sure, punk has a lot to answer for: its flirtation with Nazi symbols, the ritualized violence of the mosh pit, and the overwhelmingly white male demographic of its artists and fans. Punk has long been considered the musical language of outsiders, though not necessarily issuing from the perspectives of actual outsiders to the white patriarchal power structure. Yet punk’s cultural ethos has given rise to a diverse global ecosystem of punk rock subcultures including Afropunk, Latinx punk, riot grrrl, queercore, Taqwacore, and the activist collective Pussy Riot.

Nevertheless, punk has been claimed by the left and the right on the political spectrum to describe different visions of populism—one leading to a cooperative egalitarian society, the other to libertarianism and white supremacy. The ambiguity of punk politics originates with its early shock tactics that often attacked the idea of commonly held values.

Hijacking meaningPunk’s fascination with Nazism started with the Dictators’ “Master Race Rock” (1975), and the Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop” (1976). As Steven Lee Beeber describes in The Heebie Jeebies at CBGB’s, these bands, populated by Jewish kids, used morbid humor to grapple with an identity for which the Holocaust loomed large. London punk clothing designers Malcom McLaren and Vivienne Westwood went a step further to design inflammatory t-shirts and neckties with decorative swastikas. Punk historians explain this as a punk version of Situationist détournement—the hijacking and rerouting of symbols and images in order to neutralize their propagandistic impact.

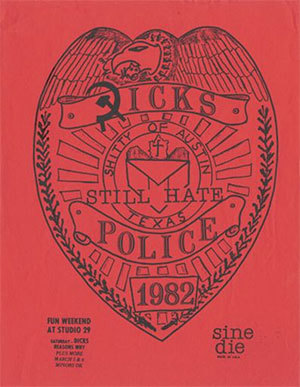

Johan Kugelberg Punk Collection, circa 1974-1986, # 8060. Rare and Manuscript Division, Cornell University Library

Johan Kugelberg Punk Collection, circa 1974-1986, # 8060. Rare and Manuscript Division, Cornell University LibraryIn theory, a British punk youth in 1977, with few job prospects and no tolerance for patriotic nostalgia, might have gleefully worn the swastika necktie to hijack the necktie’s aspirational symbol of a white-collar job. In practice, however, wearing a swastika necktie does not also neutralize the swastika as a symbol of rationalized genocide. Rather, it signals the person’s allegiance or sympathy, or at best indifference. Such cavalier treatments of swastikas beg the question of a shared understanding of history across racial, ethnic, and generational divides. This is how punk looks like Trump.

Punk songs, however, convey a more nuanced response to the historical fallout of World War II in terms that still resonate. The Sex Pistols’ “Holiday in the Sun” (1977) confronts the absurdity of a wall—in this case the Berlin Wall—as a political and physical barricade. At the end of the song, Johnny Rotten unleashes a verbal overflow (“I got to go over the wall, I wanna go under the Berlin wall, before they come over the Berlin wall”) that voices the desire to breach the wall from both sides. Listening to this song today, Trump’s obsession with building a wall along the US-Mexico border readily comes to mind. The queer Latinx punk band Downtown Boys has answered this moment with “A Wall” (2017), whose lyrics neutralize the symbol of a wall by pointing to the banality of its material existence: “from the broad side, to the hidden side . . . a wall is a wall, and nothing more at all.”

Reagan-era punks in the US also played the game of détournement, especially in homemade flyers advertising local shows. A 1982 flyer for the Dicks, a self-proclaimed “commie faggot band” from Austin TX, hijacked the police badge, turning a symbol of oppressive state authority into a punk logo and queer fetish.

Johan Kugelberg Punk Collection, circa 1974-1986, # 8060. Rare and Manuscript Division, Cornell University Library

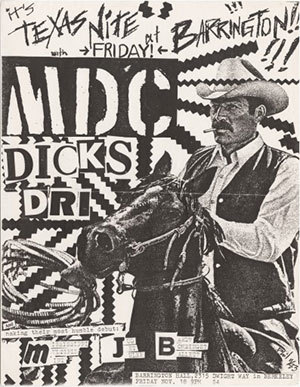

Johan Kugelberg Punk Collection, circa 1974-1986, # 8060. Rare and Manuscript Division, Cornell University LibraryA 1983 flyer for “Texas Night” at UC Berkeley’s notorious Barrington Hall features the Marlboro Man to evoke the media-constructed Wild West. With the Dicks in the list of bands, however, the image of a rugged cowboy becomes yet another queer signpost.

Aaron Cometbus Punk and Underground Press Collection, #8107. Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Aaron Cometbus Punk and Underground Press Collection, #8107. Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University LibraryThis flyer also brings to mind a song by the headliner MDC entitled “John Wayne was a Nazi” (1982) with lyrics that flip the script on another media cowboy and beloved American icon: “late show Indian or Mexican dies, Klan propaganda legitimized… When I see John, I’m ashamed to be white.” The song indicts the United States for its own history of white supremacy and glorified genocide using a clever double détournement of punk’s Nazi imagery. The ambiguous hard-edged irony of 1970s punk gave way in the 1980s to direct political language and a new activist consciousness.

Rerouting punkOn 5 March 2012, three members of the Russian activist collective Pussy Riot were arrested for staging illegal protests and making punk music videos critical of Vladimir Putin. Two of them, Masha Alyokhina and Nadya Tolokonnikova, spent nearly two years in Russian prisons and labor camps. Days before the 2016 presidential election, I had the privilege of interviewing Masha; in one exchange with me, she made this remark: “Punk is a way of life… a way to express yourself, you can shout as loud as you can, you can be totally abnormal because I kind of hate norms.”

In a topsy-turvy world of disinformation and corruption, it’s hard to say what is normal and what is abnormal. The memoirs of Masha (Riot Days) and Nadya (Read and Riot) offer gripping accounts of how they advocated for better conditions in their prisons through letter writing campaigns, legal briefs, and hunger strikes. In other words, they became committed to certain norms—of rights, justice, and the law.

This conceptual shift from illegality to legality has ramifications for punk as a political practice. The Clash once sang: “I fought the Law and the Law won.” Pussy Riot’s post-trial punk message is: Use the Law! This is not a vision of anarchy; rather, it is a vision of a functioning legal system and government institutions that protect human rights.

What is left to punk in the aftermath of Trump? Shocking confrontation may no longer be a viable punk strategy now that through Trump it has become a political norm, and a means of bludgeoning facts and institutions. In the face a lawless autocracy, punk politics may take the form of a methodical and rigorous response that thoroughly invests in the rule of law and restores faith in the democratic system.

Feature image by David Todd McCarty

The post The politics of punk in the era of Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

October 23, 2020

International Open Access Week 2020: Opening the book

Often when we talk about open access (OA), we talk about research articles in journals, but for over a decade there has been a growing movement in OA monograph publishing. To date, Oxford University Press (OUP) has published 115 OA books and that number increases year on year, partly through an increasing range of funder initiatives and partly through opportunities to experiment.

Increasingly, the policy conversation recognises that the drivers for OA are as applicable to books as they are to research articles, and research funders and policy makers are looking for ways to increase the volume of OA book publishing, but how simple is it to apply the accelerator?

The monograph livesThe value of the monograph has been questioned over recent years. Some commercial publishers have withdrawn from monograph publishing, and budgets for monographs have been squeezed. Despite being warned during this time that, if we simply listened hard enough, we would hear the death knell sounding for the academic monograph, a report published by OUP and Cambridge University Press last year found that it was very much alive. Respondents came in their thousands to advocate for it as a format and to confirm that they had no intention of giving up on it. This is supported by the growth in usage for Oxford Scholarship Online and the University Press Scholarship Online service which confirms that discoverability and access to our monographs at the point of need has never been better.

At the same time the report showed that there are now new and emerging expectations for what the monograph is and it was refreshing to see that both authors and readers expect the monograph to evolve. As open research is increasingly a foundational goal for scholarly research, the monograph must also adapt if it is to continue to be a vital resource within scholarly communications. The challenge that lies ahead of us, however, is to be mindful of both the vehicle and the terrain—how do you accelerate that evolution while protecting the value and sustainability of the monograph format?

A book is not a journalIt sounds obvious but there are significant differences in what books are, and how they develop from a period of research with practical consequences for the extent to which processes that have been applied to open access journals can be made to apply to open access books. There are several reasons for this:

There are several reasons for this:

A book requires more editorial input than a journal article. Time is spent shaping and developing the content over months or years and an appropriate digital platform is required to house the end result where it may be easily discovered and re-used. Any funding model needs to account for this to ensure this time can be sustainably invested on the part of both the author and the publisher.A book also generally takes longer to produce than an article, meaning they do not move through the system at such a high volume. In fact, our research told us that scholars value the monograph for their process as much as their output—they are considered “an organizing principle” in research. Again, funding needs to account for this slower pace of creation and lower volume of output to provide enough time in the process to reap the value of the research process and to continue to uphold high standards of academic rigour throughout.A book has a longer life span. The return for the effort expended is sometimes only felt years after publication as a title grows in standing through being discovered and cited in other works. In any model (such as green open access, a model in which authors place a version of their manuscript in an open repository) which relies on an embargo period, the embargo period must be appropriate for the lifecycle of the text. For example, if a book were to be made freely available immediately or after a short embargo period with no funding, the model becomes untenable for a publisher, however important the content or well-written the work.The monograph format is favoured in humanities and social sciences. Our research into the monograph told us clearly that scholars in the humanities and social sciences value the monograph as a “gold standard” in scholarly achievement. If research or funder policy were to threaten the monograph format, the landscape of the disciplines that make up the humanities and social sciences would come under threat.A viable futureOA is already a successful publishing model for some monographs with the most popular OA books published by OUP receiving upwards of 10,000 downloads. We publish over 1,500 monographs every year so the opportunity for greater growth and dissemination through an OA model is sizeable but the risks in the current shifting landscape are also significant.

The theme of this year’s International Open Access Week is “Open with Purpose: Taking Action to Build Structural Equity and Inclusion”. There are many angles to this which must be addressed for a more equitable future to the world of academic research and, as a university press, maintaining and expanding the future of the monograph is a particularly important. We are one of the world’s primary monograph publishers and we are accountable for ensuring that the publication model is equal and inclusive for all scholars, both in terms of funding and dissemination. A model that only works for some scholars in some institutions in some fields is not viable for an equitable future. We need to ensure that the monograph, such a key part of the scholarly discourse, has a viable future for all.

While we don’t have all of the answers and cannot do this alone, we do have some important questions that must be tackled if we are to move the discussion forwards:

What is an effective funding model for OA book publishing which takes into account both the time spent by the author in researching and producing the work and the time spent by the publisher in helping to shape and disseminate it?What timeframes are appropriate for dissemination for a long-form piece of research like a monograph which has a long life of citation and discovery?How can we ensure scholars are not closed out of the move towards OA because the current models do not fit their research areas or funding opportunities?As we reach the end of International Open Access Week for another year, these are the questions that we will be taking forward in our conversations with policy makers and funders alongside our own publishing models as we look to support our authors and readers through the transition to a more open world for research.

The post International Open Access Week 2020: Opening the book appeared first on OUPblog.

October 22, 2020

Reframing aging in contemporary politics

Aging is the universal human experience. We all begin aging from the moment we are born. In America, as we approach old age, we start to be treated differently. Instead of being included in work and community spheres, we are marginalized and ignored. Instead of viewing older age as a period of opportunity and continued contribution, the American public sees old age as a period of dependence and decline. Even worse, this sense of fatalism pervades our response to the challenges of aging. As a result, programs and policies that could address the changing demographics of the aging population get short shrift among the public and policy makers. An outward manifestation of these attitudes is ageism.

Ageism is discrimination based on negative assumptions about age. This has an impact on older people’s lives. And this impact is serious. It may be overt or subtle. We see this impact in healthcare where the one-year cost of ageism may be as high as 63 billion dollars. We see it in the workplace where discriminatory practices impact hiring, promotion, and tenure. Well-meaning aging experts and advocates provide messages about the demographic cliff, the age wave, or, worse, the “silver tsunami,” to provoke a sense of urgency about these issues. They may point out the costs of inaction by stressing that “aging populations pose a challenge to the fiscal and macroeconomic stability of many societies.” However, the public does not hear these messages the way the experts intend. This is largely because these messages cue the public’s ingrained negative patterns of thinking about aging that include a sense of fatalism that the problems are too big, the solutions are too complex, and that investment elsewhere would be more effective.

There is good news. Recent research shows that framing interventions are effective in reducing implicit bias of aging. When we deliver properly reframed messages about aging, we can decrease the implicit bias members of the public hold towards older people. Specific reframing strategies include using values to establish common ground and explanation to build understanding. For example, using the values of ingenuity and justice in communications and advocacy messages has been shown to elicit positive responses about aging and increased support for policies and programs to address aging issues.

By avoiding pitting generations against one another, using language like “silver tsunami” and “the boomers” in our communications, and by raising issues in the context of concrete systemic solutions for all of us, we can shift the understanding and discourse around aging. When we use this framing strategy, knowledge about aging increases, attitudes towards actions and solutions improve, and policy support for programs and funding grow.

2020 represents a significant year in US politics with not only key federal elections but also numerous state and local contests. As politicians work on party platforms and conduct debates, it will be important to not only include systemic solutions for aging issues but also to frame the communications in a way that helps the public understand that we are all part of the aging community and the solutions developed in aging benefit all. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the underlying ageism of our culture—“boomer remover”, for example, has been used as a common meme. Rather than fall into the trap of characterizing all older people as vulnerable and frail, it would be better for politicians to emphasize the diversity and range of health conditions among all age groups and the benefit of a community approach to safety.

Aging experts and advocates will need to be vigilant of messages that describe older people as deserving special treatment. Rather, we need to emphasize our common experiences as people who are aging and conversely, our uniqueness as individuals moving along the life course.

Changing American culture is challenging and changing attitudes and behaviors around the universal experience of aging especially so. The time to change the conversation is now.

Featured image by John Moeses Bauan

The post Reframing aging in contemporary politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers