Oxford University Press's Blog, page 132

September 22, 2020

The slippery slope of the human gene editing debate

The ethical debate about what is now called “human gene editing” (HGE) began sixty years ago. At the time, eugenicist scientists wanted to use new knowledge about the structure of DNA to modify humans—to perfect the human species by making us more healthy, musical, intelligent, and generally virtuous. A consensus later formed that gene editing on individuals to remove disease is acceptable, but nobody should try to change the human species. This is known as the somatic (individual) vs. germline (species) distinction, and it served as a moral limit on HGE for 50 years. A few years ago the news broke that a Chinese scientist had facilitated the creation of children who have been genetically modified so their descendants would also be modified—germline HGE. The germline limit now seems to be gone. Are there any limits left?

The HGE debate, like many bioethical debates, is set up like a slippery slope. At the top is an act universally considered morally virtuous (point A). Stepping on the slope at the top makes the act a little bit further down the slope (point B) slightly more likely because people have gotten used to A. Having arrived at B, it is more likely that the debate will allow C, even further downslope. Having reached C, it is more likely that the debate will reach the dystopian bottom of the slope that nobody at point A wanted to reach.

The classic slippery slope concern is that euthanasia for the terminally ill (point A) will slip to the severely depressed (point B), which will slip to adults who do not want to live anymore (point C), to children who do not want to live (point D), and eventually to E—for people who have outlived their social utility. For debates like this, it is not that you do not get on the slope at A, but rather that you try to stop the slipping by creating a moral distinction that serves as a barrier—to keep it from sliding down to where you do not want to go.

In the HGE debate, 50 years ago everyone got on the slope at point A, which was somatic gene therapy—healing genetic disease in existing people in a way that the changes would not pass on to descendants. The bottom of the slope in the debate, let’s call it D, is portrayed as an unequal world of genetic control of the species where people are designed for particular purposes. This has been metaphorically represented by the novel Brave New World and the movie Gattaca. People got on at A because they wanted to relieve suffering of existing people, and because they thought the somatic/germline barrier below would hold. If we stopped at germline modifications, HGE could not slide to species perfection. Now, the scientists who do this type of research are creating plans for more germline HGE. There are no agreed upon barriers between where we are now and the bottom of the slope.

If we look at the debates, at first glance there appear to be barriers. But, what sound like barriers in the debate are not actually limits but are conditions—speed bumps that have to be passed on the way down the slope. The first condition is safety—no HGE should occur unless it is safe. Of course, all agree with this, but note that this means that if Gattaca-style germline genetic control were to become safe it would be acceptable. Safety is a speed bump, not a barrier.

Others in this debate say that editing embryos is a type of reproduction, and women have an autonomous right to modify their children, in the same way they have a right to an abortion. This is also not a barrier, because people could autonomously select any modification they want, such as cognitive enhancements.

Scientists and bioethicists often say they want to limit editing to improving “health.” “Health” is of course a notoriously slippery concept, which the World Health Organization famously defined as “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” With this definition, “health” could encompass any social problem, particularly when it is the autonomous individual who will decide what “health” means to them.

It turns out that the somatic/germline distinction was the last clear barrier between the universally accepted somatic gene therapy for disease and the dystopian bottom of the slope. The somatic/germline barrier served to assure people that they could advance the moral good of somatic therapy without the risk of dystopia and reassured the public that scientists believed in limits. Scientists are moving past that barrier. For those who want to avoid the bottom, and those who want the public to support applications like somatic gene therapy, it is critical to develop some limits to our technological abilities.

Featured image via Pixabay

The post The slippery slope of the human gene editing debate appeared first on OUPblog.

September 21, 2020

William Sanders Scarborough and the enduring legacy of black classical scholarship

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) was founded in 1881 as a place “where young scholars might carry on the study of Greek thought and life to the best advantage.” Today, the ASCSA is a center for research and teaching on all aspects of Greece, from antiquity to the present. Its campus in Athens has two research libraries, an archaeological sciences laboratory, archives, and other facilities. The School carries out excavations at the Athenian Agora, the political and commercial heart of the ancient city, and at the ancient city of Corinth.

More scholars than ever can fulfill the founders’ vision, but the School has recently committed to doing even more. In July 2020, as part of a long-term commitment to address historical underrepresentation of Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic, and other People of Color scholarly communities in Classical Studies and Hellenic Studies, the ASCSA announced a fellowship honoring William Sanders Scarborough, a trailblazing African American scholar.

The ASCSA’s early leadership actively welcomed African American scholars of Classics. In 1885, Wiley Lane, Professor of Greek at Howard University, was slated to go to the School to study modern Greek, supported by funding from the federal government. Tragically, Lane died of pneumonia before he could depart. In 1886, the Chair of the ASCSA Managing Committee, John Williams White, encouraged William Sanders Scarborough (1852–1926) to attend the School and asked Scarborough to tell other Black scholars about the ASCSA. Lack of funds prevented Scarborough from going. It was not until the 1890-91 school year that John Wesley Gilbert of Paine Institute (today Paine College) in Augusta, Georgia became the first African American member of the ASCSA, with the support of a Brown University fellowship.

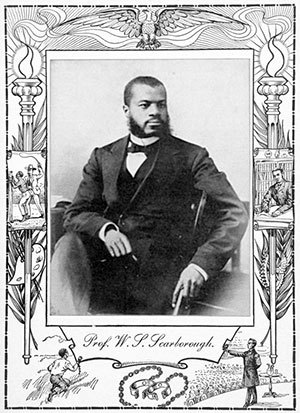

Professor William Sanders Scarborough (image via Wikimedia)

Professor William Sanders Scarborough (image via Wikimedia)Though Scarborough never made it to ASCSA, the award celebrates his sterling reputation as an intellectual pioneer whose achievements as a professional black philologist were unparalleled. With the help from friends and family, and even his mother’s owner, he was able to overcome a childhood spent in slavery to become an icon within the academy, renowned first as the author of First Lessons in Greek (1881), published at a time that many did not believe a person of African descent had the intellectual capacity to do so, and later as president of Wilberforce University (1908–1920), which (under the aegis of the African Methodist Episcopal Church) was a powerhouse among the historically black colleges and universities founded during the 19th century.

Throughout his life, Scarborough championed the classically-based liberal arts as a way for his students to get the best from life. Revelling in his books, happy in his marriage, and interested in every sort of cultural pursuit, his life mirrored the same classical values.

Scarborough traveled widely to the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy, including Rome and Mt. Vesuvius, but this consummate philhellene was never able to fulfill his dream of studying Greek archaeological antiquities firsthand at the ASCSA. Twice in his life, once in 1886 and once in 1896, he was offered admission. On both occasions, a lack of funding was the impediment, along with his busy life as an academic and political figure. Undaunted, he continued to develop his career by presenting many papers, mainly at the American Philological Association, but also the Modern Language Association. He also joined many professional and academic organizations, including the Archaeological Institute of America, the American Negro Academy, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Classics remained a significant discipline at Historically Black Colleges and Universities well into the twentieth century. And yet, for many decades after Gilbert attended, black scholars of Classics did not attend the School. While the ASCSA formally remained open to all, the shifting politics of race in the United States, the School’s increasing focus on archaeology, the changing interests of black scholars and intellectuals, financial constraints, and other factors all contributed to this absence.

For too long, serious study of the Humanities and Classics was a door closed to the overwhelming majority of black men and women rising up after generations of enslavement and the rise of Jim Crow segregation. Pursuing a classical education thus became an act of defiance. As W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk (1903):

I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. … From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Philistine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land?

That Promised Land—the world of letters—remains for all of us to discover in our own personal and collective educational journeys. Exploring Classics and the Humanities is tantamount to climbing the branches of humanity’s collective intellectual family tree. Exploring the deepest longings, hopes, and fears of great writers and thinkers whose intellectual legacies we inherit, we not only can gain a fuller appreciation of all that has come before us, but we can gird ourselves for the struggle against modern social, economic, and political injustices that still make it so difficult, in Du Bois’ words, to “dwell above the veil.”

Funding opportunities, like the ASCSA’s Scarborough Fellowship, contribute to this noble effort. So, too, does a deeper understanding and appreciation of the great accomplishments and struggles of scholars like William Sanders Scarborough and generations of students and scholars who sought to follow his path and those who continue to share his dream.

Feature image by Giacomo Brogi via Wikimedia

The post William Sanders Scarborough and the enduring legacy of black classical scholarship appeared first on OUPblog.

September 18, 2020

Learning the least accessible instrument

Why would anyone choose to learn a musical instrument which is too large and expensive for almost every home, and only accessible if one is prepared to brave a lonely, cold, and dark old building? You guessed it: we are talking about the pipe organ.

Yet despite this, the instrument continues to attract players of every age and for good reasons. Nothing beats the sound of the organ, with its multitude of tone colours, or the fun of making music by controlling a huge instrument with hands and feet. What is more, the organ offers unique opportunities for making music, with its distinctive expressive possibilities, and its repertoire from the simplest music to the most complex. This means that almost everyone, regardless of technical ability, can find something to enjoy.

Various organists’ bodies have been working hard in recent years to attract and support organists from diverse backgrounds, including in the UK the Royal College of Organists (RCO) and the Society of Women Organists. And don’t think that organists are solitary types: far from preferring their lonely organ lofts, most organists are remarkably sociable and love attending the many courses and social gatherings where they can make friends and share experiences. Why not join them, and learn to play the organ yourself?

If you do learn the organ, we heartily recommend that you find yourself a professional organ teacher. As readers of these blogs doubtless know, good teaching speeds you to the standard you seek, paces your progress for maximum enjoyment, and—particularly important for organists—constantly checks your technique to help you avoid backache and wrist problems.

Finding a professional organ teacher used to be fraught with challenges but has greatly improved in recent years. In the past it was perhaps understandable that beginners at the organ would ask any local organist for lessons, regardless of whether that organist had any knowledge or experience of how to teach the organ. All too often the teacher had previously learned from an under-qualified teacher, too, and thus a cycle of poor playing was perpetuated. But now, not only are there more professional organists available who regard teaching the instrument as a profession, the 2020 lockdown has prompted many of them to teach online, making tuition available even in remote areas.

To find a teacher in the UK we suggest that you begin by visiting the RCO’s Find an Organ Teacher page. The 29 teachers listed are all qualified organists accredited by the RCO, which subjects each of them to relevant checks regarding qualifications and experience, and those relevant to child protection and vulnerable adult matters. All these accredited teachers work to a set of guidelines, they undergo continuous professional development, and they offer teaching to all ages and standards, flexible enough to suit all lifestyles. If the above list does not cover your area, you might consider asking the RCO to recommend one of its teachers to offer you online tuition. If the RCO cannot help, search other online listings of professional organ teachers for someone local to you.

However you find a teacher, it is vital to ask the right questions before going ahead, such as:

What previous keyboard experience does the teacher require in a beginner organist? Most, but not all, teachers expect some proficiency on piano, up to about ABRSM grade 5, before starting on the organ.What relevant qualifications does the teacher have? Fellow of the Royal College of Organist (FRCO) is still probably the most significant marker of excellence for organists.If you are satisfied with the teacher’s qualifications, ask about their experience as an organ teacher. A brilliant player is not necessarily a brilliant teacher!Ask for details of the printed resources that the teacher uses and check that the teacher mentions a training manual, because the quickest way to lay a firm foundation is to learn exercises alongside graded repertoire.Search online for details of any training manual the teacher mentions, and check it was written no more than 30 years ago; ideally more recently. This is because organists’ understanding of the style and technique applicable to playing repertoire written before 1800 has undergone a fundamental change in recent years.Ask if you may start with a consultation lesson, rather than signing on immediately for a term of lessons. That way you can assess the teacher’s skills without making a long-term commitment.Good luck and enjoy the King of Instruments!

Featured image: Historic pipe organ at a church by FooTToo via Shutterstock.

The post Learning the least accessible instrument appeared first on OUPblog.

September 17, 2020

Why business strategy needs to be flexible now more than ever

In these unusual times, we need flexible approaches to business strategy more than ever. Strategy is commonly viewed as a roadmap outlining how to get from A to B. Typically created by the upper echelons of an organisation, “having a strategy” means that there is an agreed masterplan which co-ordinates organisational efforts and the use of resources. The strategy plan provides a coherent set of guidance that directs how operational decisions and actions should deliver desired long-term outcomes. Refreshed periodically, this “cascading” planned approach to strategy is intuitively appealing for the order and control it promises to organisational leaders.

The practical challenges of realising benefits from a planned approach to strategy are widely reported, however. Issues include detachment in planning activities from the realities of internal and external contexts, leading to unrealistic objectives and targets; a lack of interest or awareness of the strategy from the majority of organisational stakeholders; and a failure to adapt strategy as changing circumstances render plans irrelevant.

These are not new critiques. Since the earliest days of strategy as a formal business function, the “implementation problem”, where carefully formulated plans fail to materialise into results, has been reported as a recurring issue for business strategists. And this is not exclusively a modern organisational challenge either. In the 19th century, Prussian military theorist Helmuth Van Moltke famously observed, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

For the contemporary strategist, the issues with a planned strategy approach have been further exacerbated by an environment in flux. On a grand scale, events of 2020 have plunged governments and organisations into circumstances for which few had prepared. The disrupting impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on international flows, trade, and travel are continuing to unfold, with no clear end in sight. As all aspects of life and work are having to adjust to a “new normal,” how should the theory and practice of strategy in organisational life adapt also?

Firstly, it seems that the highly disrupted context in which we are living necessitates dissolving traditional, exclusive boundaries of strategy work in organisations. The acronym VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous), first coined to describe the diverse, disrupted landscape suddenly facing US military strategists at the end of the Cold War, now describes the context for organisational strategy work. In a VUCA setting, accessing a wide range of data sources improves the likelihood of finding effective strategic solutions to emergent challenges. In brief, strategy is more likely to be fit for purpose when a wide range of stakeholders and business intelligence supplement senior manager perspectives in identifying, shaping, and agreeing what matters most to an organisation.

Secondly, there is a need to approach strategy as a flexible, adaptable process in which decisions, objectives, and initiatives are continually reviewed for contextual fit and value to the organisation. As a “permanent beta” process, strategy becomes ever-morphing, rather than holding fast, in the pursuit of favourable organisational outcomes. Strategic analysis—informed by data from a wide range of internal and external sources—is updated frequently. New insights arising about current or emergent challenges and opportunities are used to identify required adjustments to strategic priorities, focal initiatives, or even long-term aims. By involving stakeholders in the process of evaluation, frequent changes to strategy are understood to be acts of effective governance rather than failures of leadership vision and decision-making. The latest strategic thinking then regulates the flow of organisational activities, delivering optimal outcomes in attunement with shifting circumstances.

High engagement of stakeholders delivers implementation benefits too. Through learning from involvement, individuals and teams know what to do and have a sense of ownership in strategy outcomes, leading to the realisation of any necessary changes with an economy of effort. The strategy process itself flows, fed by diverse information, constant review, and the collective wisdom of those involved to maintain relevance, effectiveness, and organisational commitment.

A flexible process approach does not remove the ultimate responsibility of the top leadership team when it comes to strategic decisions—formal power remains. Rather, a flexible process approach offers new means by which the relevance and completeness of strategic decisions might be maintained, and the organisation readied for implementation work. And by endorsing and exemplifying flexible strategy practices, leaders might unlock the adaptive potential required to sustain their organisations through these unprecedented and challenging times.

Feature image by You X Ventures via Unsplash

The post Why business strategy needs to be flexible now more than ever appeared first on OUPblog.

September 16, 2020

Harlequin’s black mask

This is the conclusion of the sequence begun three weeks ago: The wild hunt (via Wikimedia) The Wild Host is the same as the wild hunt. The ancient belief in a troop of riding dead warriors has been recorded in myth and legend. The Grimms published not only a world-famous collection of folk tales but also two volumes of German legends (an excellent annotated English translation exists and is worth checking out). Unexpectedly, the procession, though frightening, is hardly ever dangerous: one should only keep out of its way. In one legend, the thirsty leader of the cavalcade even presents a helpful bystander (a boy) with a can of beer that never gives out. (Alas, the can came with a warning: the youngster was not allowed to tell anyone the secret of his treasure. He of course did, and the can stopped producing beer. In folktales, interdictions are cited only to be violated.) We may remember that the eleventh-century witness of the hunt was also unharmed, just frightened. The checkered career of the great Scandinavian deity Odin (Óðinn) seems to have begun among the dead. In the extant corpus, he appears as the god of Valhalla, the residence of the warriors killed in battle (they fight by day and carouse at night, a veritable Paradise), and numerous tales preserve the memory of that demon on horseback. He is described as the owner of Sleipnir, an eight-legged stallion that can both ride and fly. In the older scholarly literature, one can read that the belief in the wild hunt has a meteorological foundation: a powerful storm allegedly evoked associations with a furious procession of airborne spirits. But, more likely, the procession was believed to have caused tempests. The wild hunt might be primary. All this sounds fairly convincing, but where does Harlequin come in? Herla king was a pagan demon, whose name referred to war (see the first post of this series). Predictably, after the conversion to Christianity, he was associated with the Devil. The devil of folk belief is a complicated figure. One of his functions is to dupe people, even though quite often, the Devil and imps are outsmarted by the clever protagonist of such tales. That is how he acquired the role of a trickster, successful or frustrated, another complex figure, because his functions vary between those of a wily deceiver and a culture hero. One short step separates a trickster from a buffoon. Ordericus Vitalis, mentioned above, said that in Normandy, no one would believe his story. Yet the English demon did cross the sea and became domesticated in northern France and beyond. Predictably, his name lost initial h. From France the h-less Arlequin traveled to Italy, to end up as a major character in the pantomime of the early modern period. He is still untrustworthy, still a trickster, and his black mask reminds us of his long-forgotten infernal origin. Featured image: Åsgårdsreien (Wild Hunt of Odin) by Peter Nicolai Arbo via Wikimedia The post Harlequin’s black mask appeared first on OUPblog. Pandora: interdictions are mentioned, only to be violated (image via Wikimedia)

Pandora: interdictions are mentioned, only to be violated (image via Wikimedia) Odin, the Wild Hunter (image via Wikimedia)

Odin, the Wild Hunter (image via Wikimedia)

The myth of the power of singing

One morning in 2007 or 2008 I was listening to the news in my regular wait to turn onto the Birmingham Inner Ring Road, when I was surprised to hear a cheering headline: the UK government had pledged a significant sum of money to encourage singing in primary schools. Over the next few years, the Sing Up! Programme went on to provide a rich and varied collection of songs tied into the UK National Curriculum, and training for schoolteachers on how to lead singing in the classroom.

The Sing Up! programme is one of the most far-reaching examples of the use of narratives surrounding the power of singing to influence policy. Other examples include the move towards ‘social prescribing’: the practice of doctors sending people to arts participation programmes as an alternative or supplement to drugs in treating both mental and physical ailments. Or, in the third sector, choral organisations foreground the social and educational outcomes of singing to justify claiming a charitable status, with all the financial advantages that confers.

As participants in this musical practice, we can all recognise the place this narrative comes from. We have all experienced the addictive pleasures of choral participation. Moreover, in a world where budgets are squeezed, and a relentless focus on utilitarian approaches to education promotes STEM subjects over the arts, we understand the need to fight our corner to keep a toehold in the curriculum.

The belief that singing in groups is an unalloyed power for good, verging in some accounts to a panacea for all social and personal ills, is rarely subject to critique. It serves as our profession’s guiding mythology, asserting the value of what we do as absolute and self-evident. However, there are several reasons why we should think more critically about this narrative.

The stories we tell about singing and its benefits are so often presented via pseudoscience

The self-help/self-improvement industry produces a regular stream of feel-good articles that mix up cherry-picked morsels from empirical studies with earnest encouragement from creative practitioners into a pseudoscientific concoction that vividly exemplifies the genre of literature that has memorably been termed ‘Neurobollocks’ in the blog of that name. (I have recently learned that in polite society you can refer to these instead as ‘neuromyths’.)

These articles exemplify one of the key identifiers of a cultural mythology: that people believe anything and everything that affirms the narrative, without stopping to question the evidence. But if we want people to take our claims about singing seriously, we need to be meticulous about the evidence on which we base them.

The way the myth gives the impression that any and all experiences of singing are positive.

If the mere existence of a choir confers health and well-being, we are let off the hook from reflecting on the actual quality of experience we are offering. And people do continue to cling to their choral activities through considerable levels of emotional pain, which if not always inflicted by the director is usually permitted by them.

This is amongst the ones who persist in their choral singing. In my chapter for the Oxford Handbook of Choral Pedagogy I investigated the construction of the ‘non-singer’. These are some of our culture’s ‘musical walking wounded’, to use John Sloboda’s phrase; people who keep themselves clearly and assiduously separate from the category of singer, and carefully protect themselves from situations that would expose them to a repeat of the experiences that led to them forming the identity of ‘one who does not sing’. They are as much a product of our musical culture as the joyful enthusiasts, and their existence represents the dirty underside of the Myth of the Power of Singing.

The myth interferes with choral research.

The scholar-practitioner always has a tricky line to tread. As a scholar they are committed to ideals of objectivity and transparency; as a practitioner they clearly have skin in the game. The prevailing narrative that singing is always and inherently a Good Thing amplifies this conflict of interest by eliding the distinction between practice and advocacy. The result is a tendency to build mythological assumptions into research design, undermining the validity of results.

In our current circumstances, the culture of choral exceptionalism the myth breeds has, I think, added to the emotional difficulties in learning that our activity may be one of the last to be considered safe. In addition to the experience of social, emotional, and – for choral professionals – economic loss, there is a palpable shock to the ego. We have been asked to relinquish not only the activity that nourishes us, but also the comforting self-image of benevolence.

If we can let go of the defensiveness and outrage, though, this hiatus gives us the chance to reflect a little more honestly on the narratives with which we build our choral identities. Acknowledging the dark corners that the Myth of the Power of Singing has allowed us to gloss over won’t diminish the very real joy our craft brings, but will rather help us share it more effectively.

Featured image: Choral singing children by Gustavo Rezende via Pixabay.

The post The myth of the power of singing appeared first on OUPblog.

September 15, 2020

How old galaxy groups stay active in retirement

As recently as the start of the 20th century, the idea that the Milky Way contained everything that existed in the Universe was predominant and astronomers were unaware of the existence of other galaxies or any kind of star systems outside our galaxy. A few observed nebulae that had been identified as clusters of stars or clouds of radiating gas were eventually too faint to be resolved, even with the best telescopes, thus their distances remained unknown. For these observed nebulae earlier on, the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) had suggested that some might be distant systems of stars (other Milky Ways), but the evidence to support this suggestion was beyond the capabilities of the telescopes of that time.

It was only in 1924 when Edwin Hubble used a new 2.5-meter reflector telescope on Mount Wilson in California that was able to measure the distance to the Andromeda galaxy using cepheid variables—a technique pioneered by Henrietta Leavitt. Although his estimate (900,000 light-years) was about half the actual distance that we know today for the Andromeda galaxy, it was the first time that anyone had measured a distance so great in the Universe that the fundamental nature of the discovery remained intact. This measurement established the very existence of separate galaxies of stars well outside the limits of the Milky Way, marking the beginning of the study of a new scientific field: extragalactic astronomy.

We are now aware that galaxies are systems bound by gravity that were formed at the infant stages of the Universe, about 400 million years after the Big Bang (when the universe was about 3% of its current age) and contain dust, gas, and somewhat between a few million to trillion stars. Astronomers believe that nearly all—if not all—galaxies are embedded in a dark matter halo also hosting a supermassive black hole in their cores. However, not all galaxies exhibit the same morphology and most certainly they do not inhabit at the same environment.

A recent rough estimate revealed that there are somewhere between a trillion and a million, million galaxies in the observable universe. Morphologically, the vast majority of the observed bright galaxies in the universe are either spirals (galaxies with a flat, spinning disk that present a central bulge surrounded by spiral arms; a cosmic spinwheel of both old and young stars, as well as interstellar matter) or ellipticals (early-type galaxies that are fairly round or slightly elongated to ellipsoid- shaped systems that contain mainly older stars with very little interstellar matter). While a few galaxies are isolated or in pairs, more often the environment that they lie into varies from a system of a few tens of galaxies (galaxy groups) to a large association of thousands of galaxies (galaxy clusters), with the largest concentrations of galaxies mainly found across the knots between the vast network of filamentary structure that spreads across our universe.

However, most galaxies and stars in the Universe resides in galaxy groups hence they are the most important laboratories to study galaxy formation and evolution. They contain more than half of all galaxies, compared with clusters at only 2%. While people might think of them as mini-clusters, they are not simply scaled-down versions of galaxy clusters, as they possess shallow gravitational potentials and low relative velocities between their member galaxies that are conducive to the galaxy mergers and tidal interactions that drive rapid galaxy evolution. Almost all galaxies are thought to be part of a galaxy group at some stage of their evolution (so called pre-processing) before they are eventually assimilated into clusters.

In the early stage of the development of a group, galaxy interactions and mergers lead to enhanced star formation, black hole growth, and galaxy transformation. But this process is also a path to what has been thought of as “galaxy death”—large spiral galaxies are transformed into early-types with little or no star formation as an inflow of gas towards the galactic core triggers phenomena of fast star formation while a high temperature (10^6–10^8 K) halo of gas that eventually surrounds the galaxies (visible only in the X-rays) builds up. Any new galaxy that might fall in the group at this stage, will have its cool gas stripped off by the built-up hot gas halo, choking off their star formation as well, and we eventually end up with an apparently quiescent system in which the stars slowly age and most of the galaxies are “red and dead.” For galaxy groups where the dominant galaxies are mainly ellipticals, these evolutionary processes occurred earlier in the past therefore, especially in the local Universe, galaxy groups are usually thought to have settled down to a quiet retirement after the frenzied activity of collisions and explosions associated with their formation.

However, with multi-wavelength observations, a different picture emerged for astronomers: that of a violent activity. These systems are not dead, but they have instead become active in a different way: they are dominated by the activity from gas feeding into the central supermassive core igniting an active galactic nuclei. This process can produce radio emission that can launch powerful jets or winds of relativistic particles, which may travel thousands or millions of light years out into the surrounding environment driving gas flows, shocks, etc. These fast outflows from the centre of the galaxy are pushing on and heating gas near the galaxy and blowing bubbles in the gas “recycling” and transforming the galaxy and the surrounding environment. Eventually, these environmental interactions leave imprints both on the developed surrounding halo of hot gas which is seen in the X-rays and in plasmas produced in the core from the interaction with strong magnetic fields that are mainly visible in the radio wavelengths.

This is the reason why astronomers use a unified approach, combining observations in multiple wavebands in order to comprehend the process of galaxy formation. This provides a unique opportunity to learn about events that took place in a largely unobservable past combining a mosaic of information. Such vigorous behaviour in an old group of galaxies in the local universe (NGC 1550) was unexpected as an infalling galaxy seems to have set the whole group core in motion restarting galaxy evolution processes and suggests that we must re-evaluate the extent that galaxy groups can change, even today, and think again about what they might look like in the future.

Featured image:

The NGC 1550 galaxy group, viewed using a combination of optical, radio, and X-ray observatories. The galaxies and foreground stars are shown using multi-colour optical imaging from the PanSTARRs survey. Blue colours show X-ray emission from the halo of 10 million degree hot gas which surrounds the galaxies, imaged by NASA’s Chandra and ESA’s XMM-Newton observatories. Radio emission, detected using the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope at 610 MHz and shown in green, traces the jets of high-energy particles thrown out by the supermassive black hole in the heart of NGC 1550 around 33 million years ago. The lopsidedness of these jets was the first clue that the group had been disturbed by the infall of a new galaxy.

Konstantinos Kolokythas & Ewan O’Sullivan image via NASA’s Chandra observatory, ESA’s XMM-Newton observatory, and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) from Pune, India.

The post How old galaxy groups stay active in retirement appeared first on OUPblog.

September 12, 2020

How protecting human rights can help us increase our Global Health Impact

As the COVID-19 pandemic surges across the world, justice and equality demand our attention. Does everyone have a human right to health and to access new essential medicines researchers develop? Can pharmaceutical companies patent the medicines and charge high prices, selling them to whoever can pay the most? How can data help us address global health problems like the coronavirus?

I believe everyone should have a legally enforced human right to health that gives them a right to access essential medicines. Essential medicines are important for even a basic minimum of health and the human right to health is justified, in part, because it protects everyone’s ability to live at least minimally well. Governmental, and sometimes non-governmental, organizations should help people access essential medicines and no one should make it difficult or impossible for people to secure them.

The human right to health is important for protecting everyone’s ability to live minimally well, in part, because it gives rise to what I call the virtue of creative resolve—a fundamental commitment to overcoming apparent tragedy. That is, those committed to fulfilling the right often refuse to accept that doing so is impossible, come up with creative ways of fulfilling the right, and act to fulfill it.

Those who lead efforts to improve public health often exhibit the virtue. Consider how human rights advocates galvanized a global effort to extend access on essential medicines for HIV. Activists simply refused to accept pharmaceutical companies’ claim that it was impossible to lower prices and educated patients to demand access to treatment. Mass protests and generic completion brought prices down from $12,000 per patient per year to $350.

Or consider how one human rights organization, Partners in Health, fought drug resistant TB when no one thought it was possible to do so. They refused to accept the “conventional wisdom” that it was impossible to help people with drug resistant TB in developing countries. Partners in Health hired community health workers to help people access treatment even in some of the world’s poorest countries. By showing that it was possible to get good treatment outcomes, they greatly increased funding for TB treatment around the world.

Similar efforts have transformed the global health landscape by helping us eliminate smallpox and reduce the prevalence of many other devastating diseases like polio and Ebola, and creative resolve can help us combat COVID-19 and extend access on essential medicines more broadly. Rather than simply accepting that it is impossible to help everyone secure new drugs and technologies for serious illnesses like COVID-19, we should find ways of working together to meet those needs. One possibility is to rework the incentives pharmaceutical companies, and other health organizations, face for producing and helping people access new drugs.

There are many reasons people cannot access the essential medicines they need but one is that companies make the most money by lobbying to extend monopolies on their interventions that let them set high prices only the richest can afford. I believe pharmaceutical companies fail to respect, and even violate, people’s human rights to health when they do this.

Good data, for instance through the Global Health Impact, can create incentives for pharmaceutical companies to stop violating rights and start living up to their obligations. By measuring medicines’ global health consequences, socially responsible investors, ethical consumers, and others can support companies that are having the greatest Global Health Impact. Researchers can, for instance, give companies with the best medicines a Global Health Impact label to use on everything they make—from pet vitamins to mouth wash. If even a small proportion of consumers make purchasing decisions on this basis, that can create a large incentive for companies to do what gets them highly rated: increase their Global Health Impact. Moreover, there is some rigorous empirical evidence that such labels affect brand perception.

I think consumers should support such initiatives if doing so becomes a realistic possibility. People may be free to purchase what they wish under just institutions that will make sure the consequences of their actions are acceptable. But few of us live in such ideal conditions. Absent just institutions, we should consume in ways that bring about positive change and ensure that we are not complicit in supporting companies violating rights or failing to live up to their responsibilities.

Many people desperately need essential medicines for malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS, and other global health threats as well as to fight COVID-19. How we think about health and human rights, and what we do to encourage pharmaceutical companies and others to extend access to essential medicines around the world, can save millions of lives. I believe that by embracing the human right to health, and acting with creative resolve, we can work together to overcome tragedy.

Feature image by Wengang Zhai on Unsplash

The post How protecting human rights can help us increase our Global Health Impact appeared first on OUPblog.

September 10, 2020

The role of masculinity in reforming police departments

For decades there have been murders of unarmed black people by the police, which in recent years has been exposed and protested by the #BlackLivesMatter movement. This summer, unprecedented numbers of protesters have voiced their outrage in response to the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the very recent and utterly senseless shooting of Jacob Black, and countless other acts of violence. Many mayors have announced plans for reform. The protests have rightly focused on the roles of race and racism in police brutality, but more attention needs to be given to the role of gender, particularly as municipalities seek to repair the police force to avoid this unnecessary use of force and violence.

Using data from the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department in California, a 2008 study found that male officers were three times more likely to commit unwarranted shootings than their female counterparts. Additionally, white male police officers were 57% more likely than Latino male officers to commit such a shooting. These statistics refer to the group that constitutes the majority of police officers in America—white men.

But even more importantly, the culture of police departments tends to be macho and hyper-masculine—a culture which glorifies violence. This has always been the case but it has intensified as police departments across the county have moved from the community policing approach to militarization, aided by federal grants.

While among the general public masculinity is seen as synonymous with being male, psychologists view it differently—as a set of social norms, in this case norms for how boys and men should think, act, and feel. Masculinity is problematic in that that most boys are made to feel that they must conform to gender norms—that is, act in ways consistent with their gender. Masculinity is presented as obligatory for most boys, and most boys feel they have no other choice but to conform to masculine norms. This is not true for girls, who are given much more flexibility and latitude when it comes to their performance of gender than are boys. Furthermore, one of the principal functions of masculinity is to establish several hierarchies: of men over women, of white men over men of color, and of straight cisgender men over gay, bisexual, and transgender men.

To move away from the macho and hyper-masculine culture, police forces must diversify—not only in race but in gender—their ranks and leadership. The presence of many more women, openly LGBTQ people, and non-white officers on the police force, and deploying training designed to heighten awareness of masculinity and its relationship to violence, will be crucial in this regard.

Although most boys are expected to conform to masculinity norms, most adult men come to accept who they are, even if they do not meet the masculinity ideals. Masculinity is, after all, a tough standard. That is, they come to terms with the messages from their childhoods and recognize that their unique personalities do not fit or need to fit the ideal in all ways, perhaps saying to themselves “I am not the most masculine guy in the world but that’s OK.” A smaller group feels deeply ashamed of themselves for violating the masculine norms. Experimental research using the “precarious manhood” paradigm has shown that such men, when their masculinity is threatened, tend to respond with aggression.

The research that has been conducted over the past 40+ years shows that one or another scale that measures masculinity is correlated with one or another harmful outcome, many related to violence. Since most adult men do not conform to masculine norms, what accounts for these harmful outcomes? One source is the group of men who respond to threats to their masculinity aggressively. In addition, masculinity’s destructive outcomes also arise from those men who “check all the boxes,” and conform to masculine norms to the greatest extent. These are the men whom we might label as hyper-masculine. Both groups of men tend to populate police departments as currently constituted. Their influence must be diluted by diversifying police forces.

Featured image by Free-Photos from Pixabay

The post The role of masculinity in reforming police departments appeared first on OUPblog.

September 9, 2020

Etymology gleanings for August 2020

These gleanings should have been posted last week, but I wanted to go on with Harlequin. That series will be finished next Wednesday; today, I’ll answer the questions I have received.

The idea of offering more essays on thematic idioms was received very favorably, and I am grateful for the suggestions. Yet let me repeat that my dictionary, now ready for submission to the publisher, contains only 1161 entries of varying length, and of course not all subjects are represented in it. The database at my disposal absorbed about 3000 items from various sources, but, as usual, when one begins collecting the data, the main danger is to miss something, but, when the work is over, it is more important to get rid of all kinds of uninspiring rubbish. The idioms that have survived ruthless editing seemed interesting to me, and I preferred a shorter book to a collection full of trivial data. At the final stage, I put together a thesaurus and thus isolated the especially prominent themes: curious proper names, alleged or real Americanisms, naval phrases, phrases pertaining to family life, and a few more. In this blog, I’ll try to go on in the same vein as before, but my resources are limited.

Naval usage and beyond A common supply of rags. (Image via Pixnio)

A common supply of rags. (Image via Pixnio)There are hundreds of such phrases. Over the years, I have discussed about a dozen idioms going back to sailors’ experiences. Some of those in my database contain explanations that are too short or dubious, but I can add two that look attractive. One of them is to part brass-rags “to fall out, to part on bad terms.” Here is the explanation from the database: “It is a custom in the navy for two men in a gun’s crew, or otherwise, to have a common supply of rags and other cleaning material; if they quarrel sufficiently badly to dissolve partnership, they are said to ‘to part brass-rags’.” And: “The term ‘raggy’ is lower-deckese for ‘chum’—blue-jacket ‘pals’ being wont to share their ‘cleaning rags’.” The OED’s earliest citation is dated to 1898.

Quite often a phrase may have a nautical origin, but there is no certainty. One such phrase is to set the cap. It is used by a woman about a man when she wishes to become engaged to him. According to Earnest Weekley’s etymological dictionary, this is one of many nautical metaphors (like the French mettre le cap sur “to turn the ship”). Weekley was a first-rate word historian. Since his main area of expertise was French, he often found French sources of English words and expressions, where no one else would have thought of looking. Sometimes, despite my admiration for Weekley, I wonder whether he went too far in his conclusions. I discovered long ago that being a specialist in some area may result in an aberration of vision: for instance, those who are experts in Dutch or Scandinavian etymology are apt to find the origin of English words in Dutch and Icelandic, and so forth. This does not mean that they err: one should only beware of their focus and excessive zeal. That said, I hope Weekley was right!

Setting a cap. (Image by John James Chalon via Wikimedia)

Setting a cap. (Image by John James Chalon via Wikimedia)In a comment, our reader wrote that her late husband, a sailor, used to call “bathroom” the head (to hit the head “to go to a bathroom”). She suggested that early ships did not have bathrooms and the sailors would use the sea instead. In the famous The Sailor’s Word Book by Admiral Smyth, head occurs hundreds of times, but I could not find this sense of the word. Yet I think our correspondent was close to the truth: toilets for sailors are indeed situated in the bow, and head is the name for the place. They might be situated in the stern too, and it is probably not for nothing that poop, a Romance (sound-imitative?) word, has a second, universally known meaning in English.

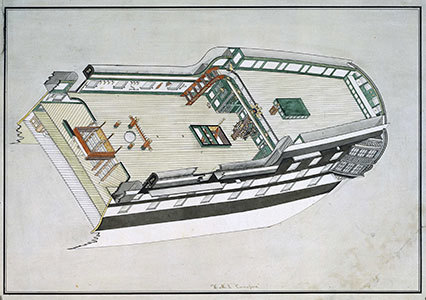

A poop deck. (Image via Wikimedia)

A poop deck. (Image via Wikimedia)In the same post (August 5, 2020), I mentioned the phrase let George do it. One of our readers commented on it. The following query from the New York Public Library, going back to 1923, may be of interest, even though it was never answered:

“The expression ‘Let George do it’ has in the last ten or dozen years become current in America. Especially during the [First World] war was it in common use. The phrase meaning, of course, ’Let the other fellow do it’. We are interested to learn if there is any foundation to the statement that this phrase is of English origin. We know that the French have employed for several centuries a very similar expression, ‘Laissez faire à George, il est homme d’âge’ [‘Let George do it, he is a grownup man’] which they trace back to the time of Louis XII. Has such an expression been used in England, and, if so, is there any explanation of its origin known to you or your readers?”

A century later, I would like to ask our British readers: Do you know this phrase, and, if you do, what do you know about its connection with French?

A recent post was devoted to idioms referring to family relations (August 19, 2020). In a comment, a reader mentioned the amusing phrase the grey mare is the better horse, said about a henpecked husband. The phrase, which is quite old (the OED has a version of it going back to 1529), has been discussed many times but without success. From the literature at my disposal I learned a good deal about crusaders, about the use of mares in the Middle Ages, about Chaucer’s knowledge of farmers’ horses, and so on, but nothing about the idiom. Apparently, a mysterious grey mare was considered much more useful than some stallion (metonymically, the mare’s “husband”), but why grey? Or did the phase once mention a grey (white, black) stallion? Losing the end of a long idiom is not uncommon. The conjectures known to me lead nowhere. Phrases like a horse of another color and curry favor (favor goes back to Old French favel “pale,” the reference being to a pale horse), as well as all kinds of biblical references to horses are suggestive but do not explain the English adage, provided it originated in England.

Why cannot we split infinitives?Such was the question in one of the comments. Of course, we can. The particle to (and the same holds for German zu, Scandinavian at, etc.) is a relic of the preposition before the dative of an infinitive, because in the past, infinitives were declined. German nouns like Leben “life,” with its genitive Lebens, remind us of the genitive of the infinitive. English has lost nearly all endings, and, when we hear live, it may be to live or (I, you, they) live. That is why we say to live, when it is necessary to mark the infinitive. German has retained the ending –en; therefore, it is not necessary to use zu with the infinitive in isolation: the German for to live is leben, not zu leben. In principle, groups like to see, to hear, to do are almost single units, but the merger has never been complete, and sometimes, especially when adverbs occupy an awkward position in a sentence, the separation is fine. Consider the following:

“to fully understand and appreciate the enormous influence of this change, one has only to compare…”

“To understand and appreciate fully”, etc., is OK but it separates the verbs from their object and perhaps a split infinitive is the best option in this case. But “one has to only compare” would be monstrous. To be or not to be, right? Now, on the eve of a new academic year, university instructors receive countless letters from the highest administrators about how to deal with the pandemic. Again and again, we are implored to not ignore the needs of students, to not forget that the circumstances have changed, to again explain to our students, and so forth. I have no tolerance for this ugliness. The rule is known very well: avoid gratuitous splitting.

War and peace: an etymologyIon Carstoiu, my regular correspondent from Romania, points out that the words for war in various languages seem to be associated with the names of pagan deities, sometimes the same names in various cultures. For example, he derives bellum, etc. from such names. As far as I know, people invent the names of their gods from words, rather than the other way around.

Feature image by Jean Louis Tosque from Pixabay

The post Etymology gleanings for August 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers