Oxford University Press's Blog, page 135

August 25, 2020

How germs (or the fear of them) spawned Modernism

The world’s attention has been fully trained for many months on detecting a microbe that, inevitably, most people will never see for themselves: SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. We take for granted the invisibility of this new enemy. But when scientists first ventured the hypothesis that germs were the cause of many virulent diseases, a hypothesis known as “germ theory,” the claim was met with substantial skepticism.

The scientific basis for germ theory emerged in the mid-19th century, yet debate over its validity continued for decades. In July 1919, for instance, The New York Times ran an article, “Doctors in Duel Over Germ Theory,” that ran as follows:

To prove his theory that germs do not cause disease, Dr. H. A. Zettel … today challenged Dr. H. W. Hill … to a duel to the death with germs. Dr. Hill accepted the challenge and the two will expose themselves to the most virulent of contagious diseases, including typhoid, smallpox, and bubonic plague. Dr. Zettel will use in his defense against the germs only sanitation, pure air, and sanitary food and drink. Dr. Hill will expose himself after scientific inoculation and vaccination. The survivor is to be honorary pallbearer at the funeral of the victim.

Rarely does hindsight provide such perfect clarity about the rights and wrongs of a dispute. Further wind at the back of germ theory was the fact that as Zettel and Hill were planning their duel, the world was contending with what remains the most deadly pandemic in recent history, the 1918 Spanish Flu, which caused more than 50 million deaths worldwide. Then (as now), the pandemic awoke public interest in infection prevention and control, and people around the world made substantial personal efforts to protect themselves, including wearing masks, and taking personal and domestic hygiene to new lengths.

All these efforts were limited, however, by the basic conundrum of germ theory: that infectious agents are imperceptible by the human senses and detectable only through complicated testing performed by experts. Bacteriologists had to admit the very inconvenient truth that a germ-infested surface and a sterile one looked exactly the same to the public eye.

In the face of this bad news, modernism provided not a solution, but rather an imaginative accommodation to the facts. Confronted with the perceptual gap between the capacities of the senses and the scale of germs, modernism offered a new model for private life, with more mechanized conveniences, enhanced opportunities for cleanliness, and lots of light and air. The startling newness of modernist aesthetics seemed to provide access to a better world, one in which design enabled health-preserving hygiene and the artist’s vision could transcend the messy and dangerous realities of everyday life.

Frankfurt kitchen. Public domain via Wikimedia

Frankfurt kitchen. Public domain via Wikimedia

In the home, kitchens and bathrooms took on the appearance of laboratories, with a new emphasis on unadorned and sealed surfaces so that dirt could be easily seen. Modern architects explored the potential of glass, a material which seemed to embody a perfect visibility and gratify the desire to see the unseen. Bauhaus design, for example, was stripped down to emphasize its own structure; ornamentation on a building was considered positively immoral.

Like architecture and design, modernist literature also bodied forth the fear of germs and the desire for health through hygiene. T. S. Eliot’s poem “The Wasteland” (1922) speaks of “fear in a handful of dust.” Ezra Pound argued in “How To Read” (1931) that poets must maintain “the very cleanliness of the tools, the health of the very matter of thought itself.” William Carlos Williams spoke of the need for “hygienic writing,” writing that would have a cleansing effect on language. These were metaphors, of course, since no words were cleaner than any others, but modernist writers turned to a stripped-down style to exemplify hygiene in writing. Cleanliness, writers argued, could be expressed through clarity; as George Orwell was later to say, “Good prose is like a window pane.”

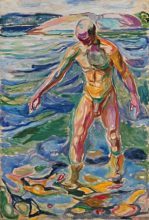

The always-incomplete quest for asepsis left its marks all over modernism, with traces that can be found in many iconic modernist works: Marcel Duchamp’s allusion to the “hygiene of the bride” in the Large Glass; Virginia Woolf’s opening reference in Between the Acts to an incomplete sewer system; the prevalence of scenes of bathing in paintings by Paul Cezanne, Edvard Munch, Duncan Grant, and others; the centrality of the sink in Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, and many more.

Bathing Man by Edvard Munch. Public domain via Wikimedia.

Bathing Man by Edvard Munch. Public domain via Wikimedia.It remains to be seen how COVID-19 will reshape our imaginations and tastes in the future. We may have seen a hint in Eschaton, a live, on-line immersive theater production directed by Taylor Myers. Eschaton is accessed by audience members via a series of Zoom links, each with its own enigmatic passphrase. Entering the rooms of Eschaton, you find lonely spectacles overlooked by the visible audience members, each confined to their own squares.

One of the great themes of modernism was the longing for connection, an appealing counterweight to the public health requirement for distance. The performers of Eschaton seem to seek connection as well, despite the concessions now required again by the presence of the invisible enemy among us.

Featured Image Credit: Maison de Verre by Subrealistsandu via Wikimedia Commons under license CC BY-SA 3.0

The post How germs (or the fear of them) spawned Modernism appeared first on OUPblog.

August 24, 2020

Addressing racism within academia: a Q&A with UNC-Chapel Hill PhD of Social Work Students

Anderson Al Wazni is a white Muslim woman, Stefani Baca-Atlas is a US-born Latina, and Melissa Jenkins is a biracial Black woman; all three women are doctoral students. They experience the world in different ways and have worked together to share their perspectives on challenges and opportunities for non-Black students with marginalized statuses to work towards racial justice in the academy. All three women acknowledge that they present as hetero, cis-gen women living in a heteronormative environment, and their opinions on race and racism are as unique as their identities are not meant to represent the views of other marginalized students. The purpose of this piece is to provide white colleagues with a view into the world minoritized students navigate and to offer hope and solidarity to Black students and minoritized allies.

Within academia at large, the presence of tenured Black faculty, students of color, anti-racist courses and course material are sorely lacking. Like every institution in our nation, social work is steeped in systemic white supremacy. The governing bodies of the social work field demand that both educational programs and professional ethics directly confront racism and actively deconstruct it, yet academic social work has largely failed to realize the altruistic ideals with which the profession identifies. Black Lives Matter ignited a fire over the summer, but will a shadow fall on this movement as the semester continues? As universities are forced to grapple with the multisystemic consequences of a worldwide pandemic, who will continue to question why COVID-19 disproportionately burdened Black and Brown communities? If history is an indicator of what lies ahead, folks with minoritized identities will play a significant role in maintaining focus on issues related to anti-Black racism and racial justice within social work education, even though that role is emotionally and intellectually burdensome.

Students’ position in the academic hierarchy often leave them with minimal voice; however, issues of racism disproportionately burden this class of people. Forty-six percent of doctoral students are from “historically underrepresented groups” (pp. 3) (vs. approximately 33% of faculty) (Council on Social Work Education [CSWE], 2018). Although diversity in the academy has increased in the past several years, the perspective of minoritized students is often tokenized, misrepresented, or forgotten altogether (CSWE, 2016, 2017, 2018). This moment calls for opportunities for students with historically oppressed identities to engage with the academic systems in ways that promote anti-racist practice, and for non-Black marginalized students to work in solidarity with Black students to dismantle racism in the academy.

The first way that minoritized allies can support Black colleagues is by naming anti-Black racism. This can feel uncomfortable or contentious. For instance, there has been pushback regarding the use of BIPOC in recent institutional statements addressing racism. People of marginalized backgrounds may more readily understand that terms like “POC” (Person/People of Color) or “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) have a place, and that there are situations that call for naming anti-Black racism because a general oppression framework is not specific enough. These types of frameworks lack an understanding of the specific sociocultural history and contemporary oppression and violence that shapes Black culture and survival. Other marginalized people can help illuminate the heterogeneity between cultures so that Black people do not fall into an essentialist category of simply “not white.”

Second, people with minoritized identities can interrogate complicity in anti-Black racism in personal and academic settings. Questions about complicity begin in personal attitudes, beliefs, and practices. Racism as a behavior is a learned mentality and it must be actively unlearned. Marginalized students can consider different perspectives and cultivate a sense of value for cultures other than their own. Art, books, and podcasts from people with different marginalized statuses can inform various aspects of research ranging from personal hypotheses to methodology. Students may also find themselves more likely to intervene in racist situations based on stronger empathy with people from different cultures.

Minoritized allies can also interrogate their collective practices. For instance, within the Muslim community, there is a wide representation of different racial and ethnic groups and that anti-racism is a value rooted in the Quran. In reality, mosques are deeply divided. Moreover, despite the Black community being the largest demographic of Muslims in the United States, the community is not well represented within Muslim culture. For those who critically grapple with the gaps in their intentions and unintended consequences, there is an understanding that the intensity of anti-Black racism has a depth and pain that deserves its own recognition. Focusing attention to anti-Black racism in a time of intense upheaval does not detract from the oppression of others.

Similarly, in academic settings, students with marginalized identities can critically analyze the space they occupy. In response to anti-Black racism, some institutions are working to integrate anti-racist pedagogy. In “anti-racism” meetings, white people may see the presence of a Latinx person as a check in the BIPOC box; however, this person cannot speak for people who are not in the room. Non-Black marginalized folks must explicitly acknowledge the absence of Black colleagues in meetings meant to address anti-Black racism; further, marginalized students must examine their contributions to hostile or toxic environments and do the work to create environments that feel safe for our Black colleagues to engage even during these traumatic times.

Third, minoritized allies can respond when they witness racist behavior. This critical moment may have created space for some minoritized students to respond to microaggressions and overt racism in the moment; however, the process may continue to be anxiety inducing because white supremacist culture is so insidious that it is beyond reproach. Still, non-Black Students of Color have an opportunity to use privilege to challenge the status quo and push the academy to catch up and beyond the current social and political mores by responding, questioning privileged perspectives and assumptions, and supporting Black folks when they decide to take a stand.

An important note is that the ability for the other marginalized people to safely respond may be compromised. A white Muslim holds certain power, and as such, can step up and be more vocal in times where others cannot. In other contexts, a visibly Muslim woman may still be a target and vocally responding may not be a safe option for her. Those moments are rare, but when they do occur, expressing a sense of solidarity with the targeted individual can be helpful. For instance, microaggressions within seemingly “liberal” spaces are psychologically damaging. Being targeted without anyone bearing witness weighs heavy on your mind. These situations can be disruptive psychologically and emotionally.

Some challenges may feel insurmountable. Many would like to act quickly and purposefully; however, many scholars from marginalized communities hold precarious positions in the academy. Unfortunately, freedom of speech does not equally apply to all people, and this inequality is further embedded within the hierarchy of colleges and universities. There is often minimal room for BIPOC to respond when they witness racism. When BIPOC are forced to stand up for themselves in those situations, they may respond with carefully chosen and precise words, but the feelings underneath the surface are anything but calm and collected. White people can help ease anxieties by acknowledging power differentials, being open to constructive criticism, and acting in solidarity with BIPOC in the moment.

Finally, academic communities must work together to promote BIPOC inclusion and wellness. The social work academy must actively engage BIPOC voices, and they must do so while white folks participate in parallel processes of working out their emotions without BIPOC present. Centering whiteness, claiming “not to see color,” or floating the validity of any tangent of “all lives matter” are harmful to BIPOC. However, several opportunities exist to promote wellness and inclusion.

One of which is to hear and acknowledge people when they risk sharing the ways they have experienced racism rather than gaslight them. Validating students’ experiences rather than negating those feelings will go a long way in improving inclusion and wellness of BIPOC students. Creating environments where people feel equal rather than less than will promote culture where minoritized students feel strong enough to carry on the fight for racial justice. This fight will be more important than ever in the coming months as the nation and universities cope with COVID-19 and national elections.

Image Credit: Unsplash

The post Addressing racism within academia: a Q&A with UNC-Chapel Hill PhD of Social Work Students appeared first on OUPblog.

“Camping” with the Prince of Wales through India, 1921-22

As senior correspondent of the London Times, Sir Harry Perry Robinson travelled the world in search of a good story. In November 1921 he was invited by the newspaper’s proprietor, Lord Northcliffe, to make a passage to India, following the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VIII) on his nearly five-month goodwill tour of the East. For Robinson, this was a poignant visit to the land of his birth, a place he left in 1861 when he was two years old.

Correspondents like Robinson travelled with the prince in a special train by day and bunked at night along with staff and retinue in a “Prince of Wales’s Camp” set up outside whatever palace the prince lodged in that particular evening. “One of the wonders of the Prince’s tour has been the cities of tents which are put up – ‘built,’ one is inclined to say – before we arrive, and, we are told, are generally demolished the day after we have left,” he wrote. “The tents stand on each side of wide streets, laid out at right angles, the ground plan of a veritable town.” Robinson was impressed by each tent’s electric lighting and lavish appointments, “that of a comfortably-appointed study at home, with writing table, what-nots, and deep easy-chairs; and on the soft carpeted floor heavy rugs are thrown. I have even had tiger skins.” Rounding out the camp were “a post-office tent, a telegraph-office tent, an inquiry tent, a camp doctor’s tent, a central club or drawing-room tent, and mess tents for the various grades of European and Indian members of the population. It is a White City of several hundred souls, spreading over a much wider area than a corresponding settlement of bricks and mortar; and it may be occupied for one single night; then it vanishes again.”

A philatelist, Robinson was especially impressed by the postal arrangements. “The thaumaturgist is a gentleman of the name of Vas Dev (improbable as that may sound) whose laboratory is a cream-coloured post office on wheels on the Royal train,” he explained. “Possibly the words Vas Dev are an abbreviation of some magic formula or he may be a reincarnation of Merlin or Cagliostro or the Witch of Endor. Certainly he has much influence with the powers of darkness.”

We arrive in the early morning at the capital of some Native State, and an hour later, the ceremonies of arrival over, repair to our temporary home in the camp. By the time we get there; propped up on each writing-table stands a neat card printed all in gold, with the Prince of Wales’s Feathers for crest at the top, informing us precisely at what hours each day the mails for various parts of India and the world will be collected from the brand-new post pillar erected on our doorstep. On the trains at odd hours of night and day similar gold-printed missives, crested and beautiful, flutter in upon us in our compartments informing us that “if the trains arrive on time,” it is expected to distribute the next English mail on the day after to-morrow at 11 a.m. At 11 a.m. on the appointed day a bowing chuprassi steals silently to your tent door with your share of home letters in his hands.

“It is all magic,” Robinson concluded. “In Burma the mail reached us faster than we could calculate that trains and ships could possibly have brought it.”

Image one: The special postmark for mail sent from the Prince of Wales’ Camp in India.

Source: Sir Harry’s private album, provided by Joseph McAleer

Robinson also wrote about the special camp postmark. “Strange and appetizing tales are told of the enormous prices now asked and paid in philatelic circles for stamps of high denomination cancelled with the similar postmark used on the Indian tour of the King and Queen,” he noted. “It is announced in the Indian Press that in exchange for the proper amount of money Mr. Vas Dev will send to anybody whole sets or partial sets of current Indian stamps duly cancelled with the coveted mark.” Although Robinson doubted “whether any stamp of less than 10 rupees in value can ever be very precious,” the end result was clear: “the Post Office revenue must be profiting considerably; and that – if magicians can consider such sordid things – is probably what Mr. Vas Dev, like a good public servant, is after.”

Although he admitted that “the ephemerality of the ordinary canvas cities prompts to moralizing,” Robinson concluded, “we shall hardly enjoy such sumptuousness again; for India is the only country where it could be.”

Not for long. Even Robinson could not deny that the sun was slowly setting on the empire. Protesters greeted the prince at early every stop on his tour of the subcontinent, proclaiming the cause of independence under their leader, Mohandas K. Gandhi.

Featured image: Edward, Prince of Wales (seated, second row, center) and his entourage in Delhi, India, in 1922, during his tour of the Subcontinent. Sir Harry Perry Robinson is standing in the rear, second row from top, right of center. Source: Sir Harry’s private album, provided by Joseph McAleer

The post “Camping” with the Prince of Wales through India, 1921-22 appeared first on OUPblog.

August 21, 2020

Don’t blame AI for the A-Levels scandal

Many years ago, when I was a young assistant professor of economics, I had to endure a minor hazing ritual—serving for one year on the admissions committee for the PhD program. As a newbie, I was particularly impressed by a glowing letter of recommendation that began, “This is the best student I have had in 30 years.” The applicant’s test scores were not off-the-charts, but the letter was number 1.

There was a dean who chaired the admissions committee year after year and he advised me to calm down, because this professor wrote a recommendation every year celebrating “the best student I have had in 30 years.” The committee had a chuckle at my expense.

I’ve now been teaching for nearly 50 years and I know firsthand the temptation teachers have to praise students generously. We want our students to succeed and we are happy to help.

Admissions committees inevitably take this puffery into account. For the professor who, year-after-year, identified one of his students as the best student in 30 years, we discounted the claim because of the recommender’s reputation and the strong-but-not exceptional standardized test scores, but we did take into account the professor’s judgment that this student was the best applicant from his school that year. We deflated the level of the praise, but we paid attention to the rank ordering.

These memories came back recently with all of the hullabaloo related to British A-Level test grades, which are used in the United Kingdom for university admissions. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the summer 2020 scheduled tests were canceled and the government’s Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) was given the thankless task of estimating what the grades (A, B, C, …) would have been on more than 700,000 subject tests that 275,000 students signed up for but did not take.

Ofqual collected two kinds of data from the students’ teachers:

A prediction of “the grade that student would have been most likely to achieve if teaching and learning had continued and students had taken their exams as planned.”A rank-ordering of the students who were predicted to receive the same grade on a particular subject test.The Ofqual team relied on plenty of research that supported my personal experience; for example, teachers are typically twice as likely to be too generous as to be too stingy. Specifically, teacher grade expectations are accurate about half the time, too optimistic one-third of the time, and too pessimistic one-sixth of the time.

If Ofqual had simply assigned each student the grades that the teachers had reported as their expectations, the percentage of tests receiving the highest possible grade (A*) would have increased from 7.7 percent in 2019 to 13.9 percent in 2020, the percentage receiving A or A* grades would have increased from 25.2 percent to 37.7 percent, and the percentage receiving grades of B or higher would have increased from 51.1 percent to 65 percent. Interviews with teachers also revealed that almost all had submitted predictions of how their students would have done on a “good day.”

The Ofqual team could have let it go at that, perhaps attaching disclaimers warning that the grades had been inflated by teacher generosity.

Instead, they made the politically dangerous decision to reduce many grades below teacher expectations in order to achieve a grade distribution comparable to previous years. The most obvious way to do this was by relying on the teachers’ rank orderings. An extreme case would be where generous teachers ranked every student one grade too high, but made a perfect assessment of the rank order. Reducing every grade by one level would be a perfect solution.

In practice, various studies have concluded that the correlation between predicted and actual grades is not 100 percent, but more like 80 percent, which still suggests that the rank order assessments provide useful information for adjusting grades.

The Ofqual team did a detailed statistical analysis of a dozen different adjustment methods and eventually settled on a system of adjusting the scores on each subject test at each school up or down (usually down) so that the average score on the subject test would be comparable to previous years and also reflect the rank-ordering teachers had sent them. This meant, for example, that if a student was ranked in the 50th percentile among students taking a particular subject test at a school, and 50th percentile students in the past had received B grades, this student would be given a B grade, even if the teacher had reported an expectation of an A grade or a C grade. With teachers typically more generous than stingy, grades were more likely to be adjusted downward than upward.

Ofqual also made a few tweaks to account for situations where average scores from previous years might be misleading. If the sample was small, then tying current scores to previous scores would be perilous. So, with 5 or fewer students, no adjustment was made—the teacher prediction was used as the final grade. With more than 15 students, the teacher predictions were ignored. In between, with 6 to 15 students, the final scores were a combination of historical scores and teacher predictions.

Despite Ofqual’s best efforts, there were problems.

First, the anchoring of the current grade distribution to the historical grade distribution made it very hard for high-achievers at low-scoring schools to get good grades. An extreme example would be a school where no one had previously received an A* grade on a particular subject test. It would not be possible for a current student to get an A* grade, no matter how talented the student was.

Second, the heavier weighting of teacher predictions for smaller sample sizes meant that students in small samples got the full benefit of teacher generosity, and this disproportionately benefitted students at elite schools who took tests in elite subjects such as classical Greek and the history of art. For ordinary students at ordinary schools who took tests in ordinary subjects, the teacher predictions were ignored.

Overall, scores went up slightly (propelled in part by the reliance on teacher predictions for the small samples), but what got the headlines was that 39 percent of the final grades were lower than teacher predictions. The outcry was not a surprise, nor was the argument that teachers know their students better than artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms.

I have written three books warning of the dangers of AI algorithms, but these grade reductions were not an example of AI run amok. It was Ofqual’s intention to adjust grades downward to account for teacher generosity and make 2020 grades comparable to 2019 grades and they tried very hard to find a fair and reasonable way.

AI algorithms are quite different. They typically search for patterns that will enable them to achieve specific goals, like matching photographs or playing board games. When the rules and objectives are clear and the task can be repeated a very large number of times, the successes may be astonishing, including the conquering of human experts at backgammon, checkers, chess, and Go.

When the rules and goals are ambiguous or in flux, however, AI algorithms can flop disastrously.

Change a few pixels in a photograph or change the dimensions of a Go board, and AI algorithms calibrated on different data do poorly. AI algorithms for screening job applicants, pricing car insurance, approving loan applications, and determining prison sentences based on Facebook posts, Twitter likes, website visits, smartphone usage, and the like should not be trusted.

I don’t know if Ofqual could have designed a better way for adjusting for teacher generosity, but I do know that an AI>Pexels.

The post Don’t blame AI for the A-Levels scandal appeared first on OUPblog.

August 20, 2020

The apocalypse of the Inca empire [timeline]

The Inca Empire rose and fell over the course of a millennium, driven to its demise by internal strife and Spanish conquistadors. This timeline highlights a few key events from the rise of the Inca Empire to its apocalypse.

Header image by Eliazaro via Pixabay

The post The apocalypse of the Inca empire [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

How emerging adults can manage the uncertainty of the future [reading list]

Jeffrey Arnett describes emerging adulthood as a distinct stage of development from the late teens through the twenties; a life stage in which explorations and instability are the norm. As they focus on their self-development, emerging adults feel in-between, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. Nevertheless, they have a high level of optimism about what the future holds for them.

In the current climate, emerging adults are facing more instability than ever before. Whether it’s starting university, forging new relationships, or entering the job market – the uncertainty surrounding these milestones has presented many new challenges, and exacerbated the more common anxieties of adjusting to change. We’ve put together a reading list of books that address some of the key issues facing emerging adults – in areas such as education, work, relationships, and mental health – and provide advice and approaches for managing this turbulent stage of life.

Mood Prep 101: A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Depression and Anxiety in College-Bound Teens by Carol Landau

This book answers the question most parents have – “What can we do?” – when it comes to college-bound teens who may be vulnerable to anxiety and depression. This timely book empowers parents by providing strategies for helping their children psychologically prepare for college and adulthood, as well as by addressing and alleviating the anxiety parents themselves may feel about kids leaving home for the first time. Landau shows parents how they can promote healthy communication and problem-solving skills, and how they can help young people learn to better regulate emotions and tolerate distress.

[image error]

Cognitive Skills You Need for the 21st Century by Stephen Reed

How can young people today prepare for the workplace of the future? Stephen Reed discusses a Future of Jobs report that contrasts trending and declining skills required by the workforce in the year 2022. Trending skills include analytical thinking and innovation, active learning strategies, creativity, reasoning, and complex problem solving. This book aids undergraduate and graduate students in planning their education by recommending courses and projects that will help them to gain important 21st century skills.

Mindfulness for the Next Generation: Helping Emerging Adults Manage Stress and Lead Healthier Lives by Holly Rogers and Margaret Maytan

College students and other emerging adults today experience high levels of stress as they pursue personal, educational, and career goals. These struggles may increase the risk of psychological distress and mental illness. This book describes an evidence-based approach for teaching the useful and important skill of mindfulness to emerging adults. The manualized, four-session program outlined here, Koru Mindfulness, is designed to help young people navigate challenging tasks, and achieve meaningful personal growth.

The Science of College: Navigating the First Year and Beyond by Patricia Herzog et al.

This book aids entering college students—and the people who support them—in navigating college successfully, with up-to-date recommendations based upon real student situations, sound social science research, and the collective experienc[image error]es of faculty, lecturers, advisors, and student support staff. There is no single template for student success. Yet, this book highlights common issues that many students face and provides science-based advice for how to navigate college. Each topic covered is geared towards the life stage that most college students are in: emerging adulthood.

Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties by Jeffrey Jensen Arnett

In his provocative work, Jeffrey Jensen Arnett has identified the period of emerging adulthood as distinct from both the adolescence that precedes it and the young adulthood that comes in its wake. Merging stories from the lives of emerging adults themselves with decades of research, Arnett covers a wide range of topics, including love and sex, relationships with parents, experiences at college and work, and views of what it means to be an adult.

As emerging adults continue to navigate a difficult period, it is crucially important that they are able to maintain wellbeing and seek support where needed from those around them. These books have highlighted just some of the ways in which young people, and their loved ones, can implement strategies to adapt and build resilience.

Featured Image Credit: Image by Javier Allegue Barros via Unsplash.

The post How emerging adults can manage the uncertainty of the future [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 19, 2020

English idioms about family life and conjugal felicity

Several friendly comments urged me to continue the series on English idioms I started last week (see the post for August 12, 2020). That post was devoted to naval phrases. The comments suggested all kinds of topics, sewing and cooking among them. However, not all subjects are equally easy to tackle. Though in the shoreless sea of English idioms, one can find more than enough examples about anything, the material on which I can draw is limited. I depend on my database, which is fairly representative, but, contrary to that sea, not shoreless. Also, over the years, I have been collecting only the phrases whose meaning and origin cry for an explanation. This means that the likes of a stitch in time saves nine or too many cooks spoil the broth have not made it into my database. My choice of examples is limited, but I’ll try to select such as are curious and perhaps memorable.

Vasily Tropinin (1776-1857), “The Lace Maker”: A stitch in time… Image via Wikipedia.

Vasily Tropinin (1776-1857), “The Lace Maker”: A stitch in time… Image via Wikipedia.Many idioms at my disposal are local and never had wide currency. Some were discussed in the second half of the nineteenth century, and I have no way of knowing when they were coined and whether they are still current. Quite a few are witty, sometimes rude, and often truly enigmatic. Below, I’ll be indicating the dates on which the phrases were recorded, and their localities, to the extent that they are known. Family life does not look too rosy in this area of folklore. “As queer as Tim’s wife looked when she hanged herself” (queer of course means “strange, odd”; 1870). Who was Tim? Don’t worry: he has a double in “As throng [“busy”] as Throp’s wife” (1828; still current a century later). The reference must have been opprobrious, but the correspondent who sent the simile to the journal did not dare disclose the reference, and we don’t care. I face the same questions as last week. Was throng selected to alliterate with Throp, a character in some tale, or did Throp appear, in order to alliterate with throng? Most such names are puzzling: as busy as Batty (1850), as busy as Beck’s wife (1889; Devonshire), and the rest (busy here was said to mean “bustling, making a parade of one’s activities”).

Feed the brute. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Feed the brute. Image via Wikimedia Commons.A few husbands did not fare much better. In Scotland, a henpecked husband is called John Thomson’s man. John is an absurd alteration of Joan. I know the phrase from an 1849 letter to The Gentleman’s Magazine (a wonderful periodical), but the OED has an early sixteenth-century citation! Some such phrases show enviable longevity. How do you make your husband happy? Have no illusions and feed the brute (1904). Yet women could defend themselves quite well. Unhappy unions and violent quarrels are as old as Adam (and Eve). Read the post on hanging out or putting out the broom (February 10, 2016).

But oh, don’t forget sweet, innocent maidenhood! “A maid’s knee and a dog’s nose are the two coldest things in creation” (1870, Scotland). We remember from The Taming of the Shrew that the younger sister (Bianca) could not marry until somebody married Kate. The problem was not Shakespeare’s invention. Older sisters watched with unconcealed jealousy the progress of their more fortunate younger siblings toward matrimony. The idiom or rather the custom recorded in Devonshire (I have an 1889 note on it) is to dance in a pig-trough “to marry before one’s older sibling.” Allegedly, on the wedding day, the unmarried elder siblings were expected to dance barefooted over furze brushes on the floor. Furze instead of pig-trough may have a similar origin. Humiliating and cruel but not tragic.

Much sadder is the end of the phrase to braid St. Catherine’s tresses (1876 and 1916 in my database). This is a translation of a French saying meaning “to remain a virgin until marriage,” which is not a calamity even by our standards. But read on! The reference is to St. Catherine of Alexandria. “The expression is said to come from the sixteenth or seventeenth century. According to the received French tradition, it became the custom of certain churches in France in which there was a statue of St. Catherine to dress the head of the statue afresh for the saint’s feast-day, and the service was rendered by young women between the ages of 26 and 35 who were unmarried. There is a modern saying that at 25 a maid puts a first pin into St. Catherine’s head-dress; at 30 a second; at 35 the coiffure is finished.”

St. Catherine. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

St. Catherine. Image via Wikimedia Commons.We should remember that in the Middle Ages and even quite some time later, everybody who reached the marriageable age was expected to start a family. Survival depended on having many children. Both men and women who for some reason did not follow the trend aroused contempt, but women suffered more from this attitude; hence the offensive words and phrases like old maid, spinster, and the like. Poor, suffering unchosen women or those who had a reason to remain single! And if you have never seen the word wallflower, look it up! Similar demeaning words for “an old bachelor” don’t seem to exist in English. The Russian word (bobyl’) is condescending rather than offensive. The status of an unmarried woman was much lower than that of an unmarried man: men could pretend to remain single by choice.

One of the most curious proverbs is old maids lead apes in hell. A late sixteenth-century tale in which ape can be understood as meaning a dishonest bachelor trying to marry a widow does not go too far toward explaining the saying. In one of the books I found mention of the monkish story that women married neither to God nor man will be given to apes in the next world (no reference to the source), and here we seem to be on the right track. The proverb was widely known in Shakespeare’s days, and, since Shakespeare used it twice, a good deal of discussion followed. Apparently, the proverb means that those women who refuse to marry good men while they are alive will go to hell and have sex with apes.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments. Image by Jesus Arias via Pexels.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments. Image by Jesus Arias via Pexels.

Much later, in the nineteenth century, mentions of sex and ribaldry went underground. Innocent, decent people married and one day (as a rule, very soon) had children. Even references to pregnancy had to be veiled. One of the euphemisms for “pregnant” was in (sometimes on) the straw. The phrase emerged in print in the 1660s. Why in the straw? From the use of the farmyard? From the supposed practice of making beds of straw? Or was the reference to laying straw before a house in which a woman was confined? The OED doubts the last explanation. Very well-known is the idiom in an interesting condition. The French and the Germans have the same circumlocution. The most amusing part of the correspondence about the English phrase (1902) was that no one dared write “pregnant” and explained being in an interesting condition as in a delicate state of health, in the family way, brought to bed of a child, and even with the help of a French synonym: “as applied to a woman enceinte.”

What a depressing array! Now, what can to have all one’s family under one’s hat mean? Ah, the old story! It means “to be single.” The idiom was known in several regions of England (my source is dated to 1897). But let us not despair. Here is a good phrase: “That’s the chap as married Hannah.” It means “That’s what I need” (Nottingham, 1900). No one could explain it, but there must have been a story about some modern-day Darby and Joan behind it. Enjoy life while it lasts, and apes, well, apes can wait.

Featured image by Roger W. via Flickr.

The post English idioms about family life and conjugal felicity appeared first on OUPblog.

August 18, 2020

How communities can help stop COVID-19

What impact will COVID-19 have on the world? We will be confronting the genius of COVID-19 for a long time and in many ways. At the time of writing this, coronavirus is increasing its multiple harms day on day. The world peak and many more national and regional peaks have not yet been reached.

We need creative, collaborative and community-based approaches to give us the best chance to preserve lives and livelihoods until a vaccine is available and widely used.

How is global health being dismantled? As Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, expressed it, “Global health has entered a period of rapid reversal. De-development is the new norm.” In addition, from the grassroots, a reason is simply stated by a Kenyan leader of the Arukah Network: “COVID, COVID, COVID, other diseases don’t count.”

Here are some crucial ways in which COVID-19 is changing global health. Let’s start with immunisations. In July 2020, the director-general of the World Health Organization stated that “The number of children dying from missed vaccinations is likely to far outpace the numbers of people dying from COVID-19.”

Let’s now consider three infectious disease killers: AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. The Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria estimates that COVID will dislocate health systems and could double the number of deaths from those illnesses within twelve months unless urgent action is taken.

Crucial for the world are national economies, their impact on community livelihoods and critically the actual survival of the most vulnerable. The World Bank estimates that COVID-19 will push another 71 million people into extreme poverty, measured at the international poverty line of $1.90 per day.

The term non-communicable disease does not exactly roll off the tongue. However, non-communicable diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, account for about seven deaths in ten worldwide. That’s 41 million each year. Even in low- and middle-income countries, they account for more deaths than all other causes. In a survey from 155 countries carried out by WHO, approximately half of all patients with hypertension and diabetes will have their treatments either partially or totally disrupted because of COVID-19 dismantling health systems.

Women have so often been deprioritised in global health. This is happening with COVID. It is estimated that 47 million women will be prevented from access to contraception. 7 million unintended pregnancies are predicted to occur over 6 months, some from transactional sex to earn income for the family. Also, sources estimate that an additional 15 million cases of gender based-violence have occurred during every three months of lockdown, a horrifying number to consider.

Fortunately, communities can do quite a lot to address this. For too long in some parts of the humanitarian aid sector, solutions have been suggested and even dumped on poorer communities, as if those who live in comparative wealth know the answers to the realities and feelings of those they are trying to help. The title of a well-known book describes it well. “When helping hurts.”

And it doesn’t just hurt. It creates dependence and undermines the agency and creativity of the very people for whom effective solutions mean the difference between flourishing and destitution.

So one positive outcome that we are beginning to see is the greater role of local leaders, and community-based entrepreneurs, opinion formers and champions.

A quote from one group at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine expresses this nicely. “Community members, including the marginalised, identify solutions that work best in their situations. They know what knowledge and rumours are circulating. They can provide insight into stigma and other barriers. They are well placed to work with others from their communities to devise collective responses”.

Moreover, community health is of course closely related if not almost identical to primary health care. Primary health care is a brilliant and effective service and system of health care, despite its rather prosaic name.

A quote from the WHO World Health Report in 2008 articulates its essence: “Primary health care brings balance back to health care and puts families and communities at the hub of the health system. With an emphasis on local ownership, it makes space for solutions created by communities, owned by them and sustained by them.”

Countries, especially in Africa, are giving a primary health care renewed priority during the time of COVID. This includes the training of many new community health workers. Kenya is training 100,000. In Sierra Leone, community health workers already outnumber doctors by 95 to 1.

The basic unit of the community is the family: all those living under one roof or sharing the same cooking pot. Therefore, we need to think of home-grown solutions that don’t need visits to hospitals and health centres. They are especially useful when it comes to the growing ‘epidemic’ of Non-Communicable Diseases. It’s quite easy to take your blood pressure or even measure your blood glucose. Of course, we all need information and some simple equipment but in many poorer communities, community or visiting health worker can increasingly provide this.

This approach also helps to demystify and de-medicalise common health conditions that are part of people’s lives.

The use of mobile phones, WhatsApp and other forms of information technology are playing an ever-increasing role. As one community member recently expressed it: “Whether I’m deep in Malawi or deep in the Amazon, all I need is a mobile phone and connection that allows me to talk to a clinician.”

One important community group often ignored are faith leaders. Current estimates indicate that more than four out of five people in the world have a religious faith, more in Africa. Nearly every community in the world has one or more religious centre. Moreover, faith leaders are often the most respected go-to people in a community for advice and information, especially at times of crisis. Therefore, it should be a no-brainer to include them as community leaders and responders. While people may be reluctant to take heed of recommendations issued by government spokesmen, they’re much more likely to trust their local religious leaders.

There are two important provisos. First faith leaders must believe in, follow, and preach the science. Second, they need to avoid defaulting to a position that states that faith and prayer are all that is needed.

COVID-19 is a dangerous and unpredictable foe that will affect the lives of nearly everyone, especially the poorest, weakest and most vulnerable. Nevertheless, situations such as this that require community leadership and creative compassion give us the approaches we need to cultivate.

Feature Image Credit: by Toa Heftiba via Unsplash

The post How communities can help stop COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

Why chemical imbalance is the wrong way to talk about depression

Depression has often been described as a “chemical imbalance.” This description is helpful in that it shifts the view of depression from a moralizing, personal stance into a medical model, and it can help encourage people to receive treatment. However, the “chemical imbalance” model is outdated and inaccurate.

The chemical imbalance theory started in the middle of the 20th century. The discovery of biologic treatments for some mental disorders in the early 20th century (penicillin for syphilis-induced general paresis of the insane and nicotinamide for pellagra) tantalized the field with the possibility of a cure for major psychiatric disorders like depression and schizophrenia. In the early 1950s, three drugs emerged that were crucial to understanding depression: reserpine, a calming agent and antihypertensive medication that caused depression in some people; iproniazid, a newly discovered treatment for tuberculosis that was incidentally discovered to cause euphoria; and imipramine, which alleviated depressive symptoms.

Researchers spent the next decade attempting to identify how these three drugs affected people’s moods. With the technology available at that time, researchers discovered that the levels of certain chemical compounds were lower in fluid samples from people with depression. In the mid-late 1960s, several researchers consolidated the scientific evidence and proposed a theory that depression was caused by a deficiency or decrease in one or all of these chemicals. Thus, the “monoamine hypothesis” was born.

This theory inspired the development of selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are now among the most prescribed medications in the world due to their benefits for anxiety and depression. Their introduction of zimelidine and fluoxetine (brand name Prozac) in the 1980s, revolutionized the treatment of depression because the drugs were safer than older antidepressants, which could be fatal in overdose.

The chemical imbalance theory is important in the history of psychiatry. However, researchers at that time were limited by the scientific tools that were available. Scientific advances have allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of depression. The monoamine deficiency model is not supported by current research. Instead, current research emphasizes the balance of chemical activity overall, as well as the differing roles of various serotonin receptors. Other approaches, including genomics, immune factors and inflammation, functional neurobiology, and stress-induced changes are important as well. Scientists have yet to figure out how these interact with psychological and social factors, though there are models of how environmental stress can cause important changes in the brain.

The original focus on monoamine deficiency as the primary underlying cause of depression has faded. Rather, today it is treated as a likely characteristic of people who are depressed. Right now, there is no simple explanation for why depression happens. Many different biological changes occur in the depressed brain. It is likely that there are many pathways to depression, just as there are many different types or experiences of depression.

Featured Image Credit: by PublicDomainPictures via Pixabay

The post Why chemical imbalance is the wrong way to talk about depression appeared first on OUPblog.

August 17, 2020

How parents can support their teenagers starting college in uncertain times

How do you reassure and prepare for college during this time of crisis? I have been treating high school and college students for over 30 years and this is a season like no other. Previously, parents were often ambivalent; melancholy about their children growing up and moving away but happy for the privilege of college education. They wonder, how will my child do on their own? Teenagers are often excited, but anxious about social adjustment and new academic demands. Now, in this time of pandemic, financial crisis, and urgency about racial justice, all those typical emotions are overshadowed by a deep uncertainty about the future. Parents are emotionally exhausted and trying to cope with their own fears; this makes the college goodbye talk much more complicated. There is no clear path for the first year or even the first few months of college. Will there be on-campus, in-person classes, distance learning or a hybrid? Many students will not even be leaving in the fall, due to health or financial concerns, or universities’ new schedules with staggered start times. Or will parents say goodbye to their child, only to have colleges close a few months later?

Students will need more support this year. Symptoms of anxiety and depression, already extremely prevalent among teenagers, have risen significantly during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the rate of major depressive disorder in teens was 13% overall. A recent sample of college-age people revealed that now over 40% were experiencing depression or anxiety. We need to be concerned about all our teenagers, especially those who were suffering from a psychological disorder before the pandemic.

So, how to proceed? Here are some things it’s important for parents to do.

First, provide validation and positive framing. Parents can confirm their children’s feelings that this is a challenging time but still frame the situation positively. The message to a child should be, “We believe that you are ready. Yes, the situation is uncertain. There may well be disappointments or sudden changes and we will all need to be flexible, but we have confidence in you and will still be here for you.” It’s important for parents to approach the situation with an openness and a mindset toward growth. Parents should help teenagers not to fear failure as it is can be part of the ongoing educational process. This type of framing can and increase confidence.

Parents should also emphasize distress tolerance. Many parents, in the hopes of protecting children from pain, do not help them develop distress tolerance and rush to reassure them or solve their problems. Teenagers are often aware of their strengths and weaknesses, but during a stressful time like this one, they may overlook the coping skills that served them well in the past. Parents should remind their children that negative emotions do not need to be avoided or feared; that they experienced sadness or fear in their lives before and may well again, but they cope and grow. If teens do not avoid negative emotions, they will experience them and see that feelings are temporary. Similarly, parents need to accept that you’re their children will have some bad days but parent do not need to “fix” the situation.

Parents must also clarify that the college experience fosters the joy of engagement. I see engagement—with a professor, other students, a course of study or an extracurricular activity—as key to a positive college experience. Parents can help children her appreciate that college, even though it may be different from what they imagined, can be an exciting time to explore interests. Engagement is not strictly academic. For LGBTQI teens, college may offer greater acceptance and opportunity. Minority and first generation students, as well as those with learning differences, can find student groups and programs that may help address their needs.

Parents should identify the ways to obtain psychological help. There are counseling centers on most campuses and psychotherapy is viewed by most people as not only acceptable but common and normal. Don’t let shame get in the way. Deans and chaplains can provide guidance and also facilitate referrals and many centers offer online scheduling. Parents with children who have been treated for a psychological problem should plan ahead for ongoing.

Finally, parents should use their expertise as parents to identify additional specific areas of concern. Parents know their own children better than anyone else and after years of living together, they can probably enumerate what types of issues worry them, whether social anxiety, academic limitations, sex, body image, substance use and many other issues. Important for parents to let this information guide their conversations. Their teenagers will feel validated and supported.

Featured Image Credit: Image by Freepik

The post How parents can support their teenagers starting college in uncertain times appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers