Oxford University Press's Blog, page 137

August 8, 2020

How summer camps adapted to COVID-19 (and everything else)

The ballfields are quiet. The lake is placid. The bunks/cabins are empty without towels and bathing suits hung out to dry. For summer camps, this summer season has been rife with challenges, including the difficult decision not to open.

But challenge and change are not new to camps. Over the past century, camps have adapted – often proactively – with innovations that enhance campers’ biopsychosocial development. While camps have long offered enjoyment, adventure, and respite for both children and their parents; they have also contributed far more than play to American society.

By the turn of the 20th century, settlement houses in many areas of the United States began summer programs, bringing impoverished urban children to rural areas for a week or two of health-inducing fresh air and plentiful food. These informal programs soon developed into more structured summer camps, with planned activities and thoughtful programming, often enhancing agencies’ year-round programs in the city. Some camp directors recognized the educational opportunities engendered by the camp milieu. Additionally, settlement camps enabled city children to distance from the threat of tuberculosis and other contagious diseases in their neighborhoods.

In 1924, a remarkable camp was established by social worker Joshua Lieberman. In contrast to most camps of that time, it was openly co-educational and racially integrated. Campers here developed and led their own activities, explored social issues of the day, focused on cooperative rather than competitive experiences, and utilized group problem-solving.

The growth of group work as a method of social work reinforced an emphasis on democratic decision-making and values clarification in summer camps. During the 1960s, these underpinnings were reflected in an openness to social change and social action. Camps such as Minisink and Wel-Met explicitly engaged campers and staff in the civil rights and other social justice movements. Such encounters are recalled by former campers and staff as crucial in shaping their perspective on the world. This emphasis on social change persists at camps such as the Highlander Center’s Seeds of Fire program and Wavy Gravy’s Camp Winnarainbow.

Beginning in the early 1920s, at least two camps dedicated to children with social-emotional challenges arose: the University of Michigan Fresh Air Camp and Camp Ramapo. Although many camps of this type continue to thrive today, the concept of inclusion – integrating children with disabilities into the general camp population – is now receiving increased attention. However, an inclusion model was pioneered by Druce Lake Camp as early as 1915! About two-thirds of its referrals came from social agencies and clinics. Organizers paid careful attention to group composition so that no cabin group included more than one or two time-intensive campers. Another model, developed in the 1950s, involved year-round clubs (small groups) that then attended camp together. The clubs often consisted of a group of typical children with a single disabled child. Since 1970, an updated version of inclusion has developed at the Ramah camps and elsewhere. Initially grouped in their own cabins, campers with disabilities are now partially or totally integrated with other bunks of campers. Specialized staff insure that each camper’s needs are met.

As the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the United States and Canada, innovation by summer camps was again needed. Organizations including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidance on how children’s programs could function safely. Some camps decided to suspend summer programs early on, while others considered options for holding camp. Social workers and others conferred at length regarding alternatives. These camp leaders carried out risk assessments as they evaluated the ramifications of their decisions.

Howard Blas, of the Ramah camps, described the change that he and fellow camp leaders experienced. At first, it seemed that residential camps in their isolated rural environments could function, essentially in quarantine, while day camps, with their populations commuting daily, would pose greater threats. However, discussions then turned to the risks of an outbreak as well as the restrictions that would be needed. Camp professionals asked each other, at what point does camp stop looking like camp? Equity was also an issue: how could they ethically exclude high-risk campers? In the end, it appears that most non-profit residential camps cancelled their sessions. On the other hand, many camp organizers decided that risks for day camps were manageable since the camps could assess symptoms daily. Leaders also considered the child care functions of day camps. Some have cancelled while others are meeting this summer.

Many residential camps decided to offer what is now termed virtual camp. According to Cara Allen of Experience Camps, camp professionals recognized that substituting computer screens for camp activities would be insufficient and inappropriate. Thus, these camps are sending campers a care package with hands-on activities and camp memorabilia such as a camp t-shirt, a necklace, a pillowcase to decorate, and other items. They will also hold virtual bunk reunions and limited additional activities via Zoom.

Summer camps have innovated and adapted to changing societal circumstances in the past and currently. Rising to challenges, they have offered children novel opportunities, protected them from harm, and created original models for summertime growth, support, and informal education.

Featured Image Credit: by Hichem Meghachou on Unsplash

The post How summer camps adapted to COVID-19 (and everything else) appeared first on OUPblog.

August 7, 2020

Raising a teenager with an eating disorder in a pandemic

Many people have already written about the difficulties we’re having in the midst of COVID-19 – they are numerous and far-reaching, some as insidious as the disease itself. As researchers and clinicians in the field of eating disorders, we are now challenged to consider how we can best help those who are quarantined with a loved one experiencing symptoms of an eating problem. But for the family of a young person with an eating disorder, there are some specific concerns worth addressing.

First, families need to make sure underweight teens are eating enough. Family meals, in which support is provided by the household, are a mainstay of Family Based Therapy, the treatment approach of choice for many teens in need of weight restoration. In this therapy, parents take charge of meal planning, preparation, and supervision, until they can hand responsibility back to the teen. While this typically represents a big change from normal for teens, during these unusual pandemic times, families are eating more meals together than ever before. This may help make the process just a little easier. Because intake needs tend to be high to achieve renourishment, it is important for parents to have a stock of calorically dense foods in the pantry or fridge. To counteract the rigidity and stereotyped eating behavior characteristic of restrictive-type disorders, it’s critical to frequently include challenging foods. Parents can talk with their children about what is most helpful during mealtimes – maybe it’s cheerleading with encouragement or reminding them how important to their goals in sports or in school eating well and getting better is.

Families should also minimize the risk of binge eating. Parents may wonder, “if we are in the house so much now, should we get rid of foods that will tempt my teen to overdo it?” The truth is that binge eating is less about the food being eaten during the loss-of-control moment than it is a reflection of someone’s overall eating pattern, or a reaction to stressors (like feeling sad or anxious, or fighting with a friend or sibling) or circumstance (such as eating while watching Netflix or having constant, easy access to the kitchen). For these reasons, it’s more helpful to promote sticking with a pattern of eating regular meals and snacks, with a balance of nutritious, tasty foods. Parents can model non-eating-related coping strategies when feeling stressed, such as taking a walk, listening to upbeat music, or talking about it with someone. Parents can also initiate an activity and encourage a teen to join if it’s clear that he or she is having a hard time. Portioning food from large bags or serving containers in advance, having snack-size items on hand, and encouraging eating to happen at a table (rather than on the sofa) can also help minimize the chance of mindless overeating.

Additionally, it is important to be aware of body image concerns. The pandemic lifestyle may lead to people feeling worse about how they look, exacerbating a negative body image. For example, it’s more tempting to dress down when socially distancing, and there may be fewer opportunities to get out and be active depending on the summer heat and humidity.

Research has shown that the amount of time spent on social media, especially in curating an online persona or posting selfies, is negatively associated with body image, and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. In addition, some people with eating disorders describe difficulty inhibiting self-scrutiny as they are repeatedly confronted with their image while on Zoom or FaceTime. Parents should talk with their teenagers to determine if they’d like to work treating the experiences on social media or video chat platforms like exposures, leaning into the discomfort, or if they’d prefer to adjust video settings to minimize their image until they are ready to take on an exposure mindset. It’s also important to look for occasions for all family members to dress up to encourage variety in clothing choices. Unconditional body positivity need not be the goal – for most of us, body neutral is the place to aim.

Just how much to talk about the eating disorder is a common problem for parents supporting children through recovery. And given the restrictions placed on us currently, parents might be noticing a lot and feel tempted to point out every concern. It is important to flag troublesome, observable behaviors, and to clearly communicate expectations around particular goals – be it completing a meal, varying exercise routines, or trying a new food. However, these conversations are sometimes best had at a calm moment outside of mealtime. And it is equally important to continue to talk to teens about other topics – for example, popular shows, the latest goings on in a friend group, or reactions to current events in the world. Part of moving beyond an eating problem is developing and investing in other aspects of identity; this can be cultivated in conversation that reminds a teen subtly that a parent knows that the teenage is not their eating disorder. He or she is so much more.

Coping with the COVID pandemic is challenging for all of us on many levels. This is equally or more true for parents of a youngster with an eating disorder. Although the basic strategies for helping do not change, there may be new opportunities to implement them and new situations to grapple with. And it is possible that increased time together as a family may yield some surprising benefits.

Featured Image Credit: Image by prostooleh via Freepik.

The post Raising a teenager with an eating disorder in a pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

August 6, 2020

Five books related to power and inequality at work [reading list]

What is it like to work in the 21st century? Which factors influence our careers? Are there equal opportunities in society today?

With a focus on technological advancements, both at home and at work, is reliance on technology beneficial for both employees and employers? Are workplaces using technology to exercise greater levels of control? Will the recent global experiment in working from home, made necessary by COVID-19 and possible by technology, encourage a cultural movement where employees seek greater flexibility?

Explore our reading list featuring chapters that feed into these timely discussions:

Television at Work: Industrial Media and American Labor by Kit HughesThis book examines how workplaces in the United States utilised television to achieve efficiency and control over the 20th century workforce. Read this chapter to learn how companies used private satellite networks to manage distributed workforces amidst the rise of globalisation. Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are by Abigail C. Saguy

This book explores how “coming out” has expanded from the LGBTQ+ movement to the fat acceptance movement, the undocumented immigrant youth movement, the plural-marriage family movement among Mormon fundamentalist polygamists, and the #MeToo movement. Read one chapter to discover the origin of the term “coming out.” Feminist Trouble: Intersectional Politics in Post-Secular Times by Éléonore Lépinard

This book provides a critical exploration of feminism considering the divisions that exist within the movement. The author suggests that the future of feminism should focus on a feminist ethic of responsibility which reckons with power inequalities. Read a chapter to learn how the Islamic veiling debates were comparatively received in Quebec and France. Privilege Lost: Who Leaves the Upper Middle Class and How They Fall by Jessi Streib

This book tracks the lives of over 100 Americans who were born into the upper-middle class as they progress from adolescence to young adulthood. This enables an analysis of how downward mobility occurs within this group, who it affects, and why it was not foreseen. Read one chapter to discover why only around half of those born into the upper-middle class retain this position in adulthood. The author discusses how a wealth of human, cultural, and economic capital can enable people to form a professional identity focused on maintaining their positions. Digital Domesticity: Media, Materiality, and Home Life by Jenny Kennedy, Michael Arnold, Martin Gibbs, Bjorn Nansen, and Rowan Wilken

This book considers how, throughout the 21st century, technology has permeated our homes. The authors trace the life cycle of domestic technology, from adoption, to use, and then disposal, by studying original cases of people and their families. Read a chapter that focuses on the significant work required to maintain technology at home. The chapter delves into who conducts this work and the relationship between power, authority, gender, and expertise when making domestic technology decisions.

These chapters provide context to aid the discussion on 21st century working. Consider how you have experienced power, inequality, and resistance at work.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Adeolu Eletu via Unsplash

The post Five books related to power and inequality at work [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 5, 2020

Etymology gleanings for July 2020

Thanks everybody for the questions, comments, and suggestions!

The state of Spelling Reform

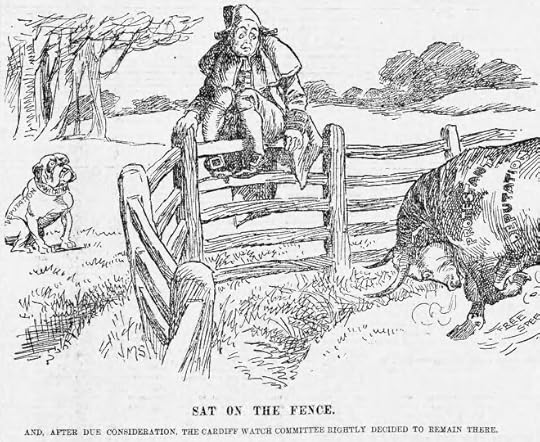

The six most promising schemes of reformed spelling, with summaries, can be found on the Society’s website (The English Spelling Society). The second (virtual) session of the International English Spelling Congress will probably take place in November. If you are interested in the fate of Spelling Reform, please register (it is free). The more people, native speakers and foreigners, scholars and students, sign up, the better. Make your voice heard, regardless of your views on the Reform! A major media event is being planned for late July or early August (you will find the information in the Society’s blog). It is crucial for the success of the Reform to present the case, without alienating the wider public. We, who think that English spelling is a handicap to literacy, rather than being a window to it, hope that the Reform will do away with at least part of the rubbish which forms a barrier to mastering English everywhere. The world gleefully calls English spelling the most absurd ever and beyond redemption. Absurd it is, but, in our opinion, not beyond redemption. Sign up, voice your support or objections, but don’t sit on the fence, which is a fence to literacy.

Don’t sit on the fence. Speak up! Political cartoon by JM Staniforth. 17 December 1898. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Don’t sit on the fence. Speak up! Political cartoon by JM Staniforth. 17 December 1898. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Hoity-toity, and all, all, all

A correspondent sent me a long list for words like hanky-panky, heebie-jeebies, and hoity-toity, and wondered why their first component so often begins with an h. Naturally, I don’t know why. If I say that h is the easiest sound to pronounce, almost a default consonant, a mere breath, my answer won’t go far, because I have no proof of my statement, except that when f, s, and any spirant begins to disappear in language, its last station is always h. Yet I can say that I know the problem and refer to it in Chapter Six (reduplicating compounds) of my book Word Origins. Not all reduplicating compounds share such a strong predilection for h: compare fuddy-duddy, razzle-dazzle, Polly-wolly-doodle, and many others. Nils Thun, a Swedish scholar, wrote a dissertation, titled Reduplicating Words in English: A Study of Formations of the Type tick-tick, hurly-burly, and shilly-shally (Uppsala, 1963). The word index to his book contains close to twenty-six pages; h-words take up four and a half of those twenty-six. No other letter is represented even approximately so well. The question about its popularity remains open, unless what I said above brings us an inch closer to the solution.

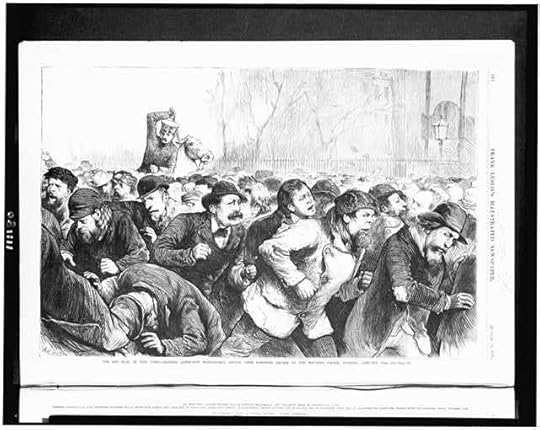

Razzle-dazzle. Image: The red flag in New York, Tuesday, January 13th / Matt Morgen(?). No known restrictions. Via the Library of Congress.

Razzle-dazzle. Image: The red flag in New York, Tuesday, January 13th / Matt Morgen(?). No known restrictions. Via the Library of Congress.Coincidences and borrowings

In one of the comments, our frequent correspondent pointed to Engl. much and Spanish mucho: they are almost homonyms and mean the same, but go back to different sources. Such cases are rather many, though textbooks like to repeat Antoine Meillet’s example of English and Persian bad (the same meaning). Such formations point to the danger of jumping to conclusions about the origin of homonyms across languages.

I have no chance of convincing my inveterate opponent that his idea of tracing English words to Neolithic Greek is a fallacy. Two weeks ago, I came up with an argument that might, I hoped, make him more cautious. The closer a Greek word is to an ancient English one, I wrote, the more obvious is the conclusion that such words are not related, because since the remotest epoch an English word would have undergone various phonetic changes that would have made the putative Greek etymon unrecognizable. I also wondered at the method of taking an arbitrary stub of a Greek word and declaring it to be the source of an English one.

Now we are told that the origin of Engl. dry goes back to the end of Greek án-uthros “waterless.” (I would have skipped this conjecture, but our correspondent rebuked me for ignoring it.) The borrowing of an unstressed syllable of a Greek word and using it as the source of Germanic draugaz is an idea that would have made even a seventeenth-century etymologist blush. Also, the entire idea is fanciful: how could anyone use the last syllable of a word for “water” to coin a word for “dry”? The syllable an- is a negative prefix. (Incidentally, another correspondent tried to produce dry from two Chinese words.) By way of postscript, I’ll answer one more query: Can dry be related to track? No. Though track is a word of Germanic origin, its sounds and those of dry do not match.

No one wants to be DRY. Public domain via Piqsels.

No one wants to be DRY. Public domain via Piqsels.This is the last time I am commenting on Neolithic Greek, but I would like to repeat that nothing at all is known about Neolithic Germanic, whatever the DNA of modern people may tell us about their genetic makeup. To justify the idea of borrowing from direct contact (as opposed to borrowing from books), it is necessary to know where and when the word could have been taken over from a foreign source. As a rule, only the names of unfamiliar objects and customs were borrowed by nomads and seminomads from their neighbors. Borrowing a common adjective needs special pleading. Herein, by the way, lies the danger of all references to undefined substrates.

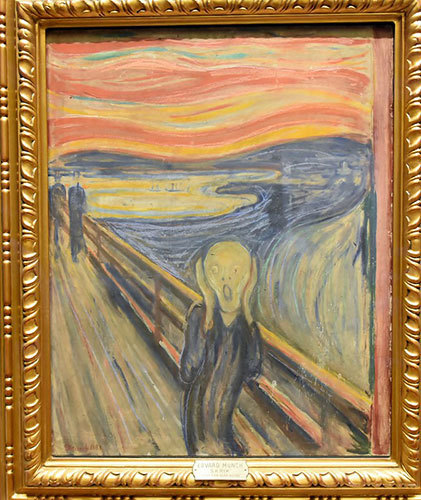

The most famous scr-word, as discussed in last week’s post. Photo by Richard Mortel of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The most famous scr-word, as discussed in last week’s post. Photo by Richard Mortel of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.More studies in advanced English

Our correspondent notes, with well-justified regret, the transformation of using into a preposition, as in: “But the new study offers a more compelling case because the researchers looked at more than 800 people USING a number of sophisticated new statistical tools.” (Of course: looked with new devices.)

He also observed that even educated people tend to produce pseudo-Latin endings in the plurals processes and especially biases. The result is process-ESE and bias-ESE (as in crises).

Jingling and splitting all the way. The ubiquitous trend, probably initiated by some semi-literate journalists, has spread not like wildfire but like a pernicious virus. Here are three examples from a major newspaper for the same day. “Classes that have always been delivered online will continue to not be counted toward the fee threshold.” Unnecessary and ugly. The old, most reasonable rule, as formulated by H. W. Fowler in Modern English Usage, is: “Split if you must and know how to do it.” “Advisers and attorneys will be allowed to fully participate in all sexual misconduct hearings.” Acceptable, though not necessary (to participate fully would have been at least as good). And a last example: “Betsy De Vos has said the new regulations aim to better balance the rights of alleged victims and the due process rights of the accused.” Here the split seems to be justified. All three sentences were written by the same man. He of course ALWAYS splits. But why treat one’s native language like a rag to be trampled with impunity?

Feature image credit: Two girls writing. Public domain via PickPik.

The post Etymology gleanings for July 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine titles on the frontiers of psychology research [reading list]

What is the responsibility of psychologists to their clients and their communities during times of crisis? Annually, the American Psychological Association meets to present the research and best practices to meet the needs of the profession and the broader world. These nine new titles present the latest, most advanced research to create a bridge between the academy and practitioners as we work to address racism and hate, face the psychological toll of COVID-19, and strive for sustainable leadership.

The Tough Standard: The Hard Truths About Masculinity and Violence by Ronald F. Levant and Shana Pryor Written by past president of American Psychological Association, this book synthesizes over four decades of research in the psychology of men and the role of masculine norms in the present moment in American including the Me Too movement, March for Our Lives, and Black Lives Matter. The Legacy of Racism for Children: Psychology, Law, and Public Policy edited by Margaret C. Stevenson, Bette L. Bottoms, and Kelly C. Burke This volume is the first book to examine issues that arise when minority children’s lives are influenced by laws and policies that are rooted in historical racism. It addresses intersections of race/ethnicity within the context of child maltreatment, custody and interracial adoption, familial incarceration, school punishment and the school-to-prison pipeline, juvenile justice, police/youth interactions, jurors’ perceptions of child and adolescent victims and defendants, and immigration law and policy. The Science of Diversity by Mona Sue Weissmark This book uses a multidisciplinary approach to excavate the

This book uses a multidisciplinary approach to excavate thetheories, principles, and paradigms that illuminate our understanding of the issues surrounding human diversity, social equality, and justice. Showing why diversity programs fail, the book provides tools to understand how biases develop and influence our relationships and interactions with others. Don’t Wait and See!: A Neuropsychologist’s Guide to Helping Children Who are Developing Differently by Emily Papazoglou Written by an expert in child development, this first of its kind book will help families take quick action to identify and address areas of concern during early childhood, a time of critical brain development. Full of practical advice on how to address developmental issues, this book aims to lower stress and build hope as families learn how to maximize their child’s potential. PTSD: What Everyone Needs to Know by Barbara O. Rotbaum and Sheila A.M. Rauch

Using a reader-friendly question and answer format, the book demystifies and defines posttraumatic stress disorder, describes its effects, reveals how treatment works, and explains why everyone should know more about the role traumatic experiences play in our lives and in culture and society.

The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature

by Iris Berent An intellectual journey that draws on philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive science, and the author’s own research, this book examines the gulf that exists between our intuitive understanding of human nature and the reality evidenced by science. The book grapples with a host of provocative questions, from why we are so afraid of zombies, to whether dyslexia is just in our heads, from what happens to us when we die, to why we are so infatuated with our brains. Innumeracy in the Wild: Misunderstanding and Misusing Numbers by Ellen Peters

Using a reader-friendly question and answer format, the book demystifies and defines posttraumatic stress disorder, describes its effects, reveals how treatment works, and explains why everyone should know more about the role traumatic experiences play in our lives and in culture and society.

The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature

by Iris Berent An intellectual journey that draws on philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive science, and the author’s own research, this book examines the gulf that exists between our intuitive understanding of human nature and the reality evidenced by science. The book grapples with a host of provocative questions, from why we are so afraid of zombies, to whether dyslexia is just in our heads, from what happens to us when we die, to why we are so infatuated with our brains. Innumeracy in the Wild: Misunderstanding and Misusing Numbers by Ellen Peters  This book presents the logic, rules, and habits that highly numerate people use in decision making. This text offers a state-of-the-art review of the now sizeable body of psychological and applied findings that demonstrate the critical importance of numeracy in our world. With more than two decades of experience in the decision sciences, Ellen Peters demonstrates how intervention can foster adult numeric capacity, propel people to use numeric facts in decision making, and empower people with lower numeracy to reason better.

Leading with Feeling: Nine Strategies of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership

by Cary Cherniss This book describes how 25 outstanding leaders used emotional intelligence to deal with critical challenges and opportunities. Featuring commentary from the leaders themselves, the book distills their experiences into nine strategies that can help anyone be more effective at work. Each chapter features activities designed to help readers apply the strategies to their own working lives.

Reset: An Introduction to Behavior Centered Design

by Robert Aunger

This book presents the logic, rules, and habits that highly numerate people use in decision making. This text offers a state-of-the-art review of the now sizeable body of psychological and applied findings that demonstrate the critical importance of numeracy in our world. With more than two decades of experience in the decision sciences, Ellen Peters demonstrates how intervention can foster adult numeric capacity, propel people to use numeric facts in decision making, and empower people with lower numeracy to reason better.

Leading with Feeling: Nine Strategies of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership

by Cary Cherniss This book describes how 25 outstanding leaders used emotional intelligence to deal with critical challenges and opportunities. Featuring commentary from the leaders themselves, the book distills their experiences into nine strategies that can help anyone be more effective at work. Each chapter features activities designed to help readers apply the strategies to their own working lives.

Reset: An Introduction to Behavior Centered Design

by Robert Aunger This book presents Behavior Centered Design, a new framework for how to change behavior and implement processes for developing change programs. Drawing on cutting-edge research in evolutionary biology, ecological psychology, and neuroscience, this approach encourages practitioners to think differently about behavior – both in understanding how and why it is produced, and in how to design programs to change it.

This book presents Behavior Centered Design, a new framework for how to change behavior and implement processes for developing change programs. Drawing on cutting-edge research in evolutionary biology, ecological psychology, and neuroscience, this approach encourages practitioners to think differently about behavior – both in understanding how and why it is produced, and in how to design programs to change it.

These books—from leaders in academia and in the practice field—continue the critical dialog of how the field of psychology can respond proactively and adaptively to the challenges ahead.

Featured Image Credit: by Sylvia Yang on Unsplash

The post Nine titles on the frontiers of psychology research [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine titles for psychologists in a time of crisis [reading list]

What is the responsibility of psychologists to their clients and their communities during times of crisis? Annually, the American Psychological Association meets to present the research and best practices to meet the needs of the profession and the broader world. These nine new titles present the latest, most advanced research to create a bridge between the academy and practitioners as we work to address racism and hate, face the psychological toll of COVID-19, and strive for sustainable leadership.

The Tough Standard: The Hard Truths About Masculinity and Violence by Ronald F. Levant and Shana Pryor Written by past president of American Psychological Association, this book synthesizes over four decades of research in the psychology of men and the role of masculine norms in the present moment in American including the Me Too movement, March for Our Lives, and Black Lives Matter. The Legacy of Racism for Children: Psychology, Law, and Public Policy edited by Margaret C. Stevenson, Bette L. Bottoms, and Kelly C. Burke This volume is the first book to examine issues that arise when minority children’s lives are influenced by laws and policies that are rooted in historical racism. It addresses intersections of race/ethnicity within the context of child maltreatment, custody and interracial adoption, familial incarceration, school punishment and the school-to-prison pipeline, juvenile justice, police/youth interactions, jurors’ perceptions of child and adolescent victims and defendants, and immigration law and policy. The Science of Diversity by Mona Sue Weissmark This book uses a multidisciplinary approach to excavate the

This book uses a multidisciplinary approach to excavate thetheories, principles, and paradigms that illuminate our understanding of the issues surrounding human diversity, social equality, and justice. Showing why diversity programs fail, the book provides tools to understand how biases develop and influence our relationships and interactions with others. Don’t Wait and See!: A Neuropsychologist’s Guide to Helping Children Who are Developing Differently by Emily Papazoglou Written by an expert in child development, this first of its kind book will help families take quick action to identify and address areas of concern during early childhood, a time of critical brain development. Full of practical advice on how to address developmental issues, this book aims to lower stress and build hope as families learn how to maximize their child’s potential. PTSD: What Everyone Needs to Know by Barbara O. Rotbaum and Sheila A.M. Rauch

Using a reader-friendly question and answer format, the book demystifies and defines posttraumatic stress disorder, describes its effects, reveals how treatment works, and explains why everyone should know more about the role traumatic experiences play in our lives and in culture and society.

The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature

by Iris Berent An intellectual journey that draws on philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive science, and the author’s own research, this book examines the gulf that exists between our intuitive understanding of human nature and the reality evidenced by science. The book grapples with a host of provocative questions, from why we are so afraid of zombies, to whether dyslexia is just in our heads, from what happens to us when we die, to why we are so infatuated with our brains. Innumeracy in the Wild: Misunderstanding and Misusing Numbers by Ellen Peters

Using a reader-friendly question and answer format, the book demystifies and defines posttraumatic stress disorder, describes its effects, reveals how treatment works, and explains why everyone should know more about the role traumatic experiences play in our lives and in culture and society.

The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature

by Iris Berent An intellectual journey that draws on philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive science, and the author’s own research, this book examines the gulf that exists between our intuitive understanding of human nature and the reality evidenced by science. The book grapples with a host of provocative questions, from why we are so afraid of zombies, to whether dyslexia is just in our heads, from what happens to us when we die, to why we are so infatuated with our brains. Innumeracy in the Wild: Misunderstanding and Misusing Numbers by Ellen Peters  This book presents the logic, rules, and habits that highly numerate people use in decision making. This text offers a state-of-the-art review of the now sizeable body of psychological and applied findings that demonstrate the critical importance of numeracy in our world. With more than two decades of experience in the decision sciences, Ellen Peters demonstrates how intervention can foster adult numeric capacity, propel people to use numeric facts in decision making, and empower people with lower numeracy to reason better.

Leading with Feeling: Nine Strategies of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership

by Cary Cherniss This book describes how 25 outstanding leaders used emotional intelligence to deal with critical challenges and opportunities. Featuring commentary from the leaders themselves, the book distills their experiences into nine strategies that can help anyone be more effective at work. Each chapter features activities designed to help readers apply the strategies to their own working lives.

Reset: An Introduction to Behavior Centered Design

by Robert Aunger

This book presents the logic, rules, and habits that highly numerate people use in decision making. This text offers a state-of-the-art review of the now sizeable body of psychological and applied findings that demonstrate the critical importance of numeracy in our world. With more than two decades of experience in the decision sciences, Ellen Peters demonstrates how intervention can foster adult numeric capacity, propel people to use numeric facts in decision making, and empower people with lower numeracy to reason better.

Leading with Feeling: Nine Strategies of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership

by Cary Cherniss This book describes how 25 outstanding leaders used emotional intelligence to deal with critical challenges and opportunities. Featuring commentary from the leaders themselves, the book distills their experiences into nine strategies that can help anyone be more effective at work. Each chapter features activities designed to help readers apply the strategies to their own working lives.

Reset: An Introduction to Behavior Centered Design

by Robert Aunger This book presents Behavior Centered Design, a new framework for how to change behavior and implement processes for developing change programs. Drawing on cutting-edge research in evolutionary biology, ecological psychology, and neuroscience, this approach encourages practitioners to think differently about behavior – both in understanding how and why it is produced, and in how to design programs to change it.

This book presents Behavior Centered Design, a new framework for how to change behavior and implement processes for developing change programs. Drawing on cutting-edge research in evolutionary biology, ecological psychology, and neuroscience, this approach encourages practitioners to think differently about behavior – both in understanding how and why it is produced, and in how to design programs to change it.

These books—from leaders in academia and in the practice field—continue the critical dialog of how the field of psychology can respond proactively and adaptively to the challenges ahead.

Featured Image Credit: by Sylvia Yang on Unsplash

The post Nine titles for psychologists in a time of crisis [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

August 4, 2020

The ethics of exploiting hope during a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had enormous negative effects on people around the globe, including death and long-term health impacts, economic hardships including loss of savings, businesses, and careers, and the emotional costs of physical separation from friends and loved ones. Since the first emergence of COVID-19, people have hoped that these harms could be contained to specific geographic areas or eliminated by the emergence of new treatments or other public health measures. These hopes have generally not been realized but they have produced opportunities for some businesses and politicians to benefit from them.

Hope for a better life – or in this case, hope for an end to or lessening of the COVID-19 pandemic – can make us vulnerable to others by encouraging actions like buying an unproven medical treatment or putting our trust and votes in the hands of a political leader. When these hopes go unfulfilled, we face the loss of financial resources, access to more effective medical treatments, and faith in the political process.

When COVID-19 first appeared in the United States, it was not long before sellers of purported coronavirus cures began appearing online, ranging from essential oils to stem cell treatments. Most famously, hydroxychloroquine – a known effective treatment for lupus and prophylaxis against malaria – quickly went from a compound worthy of scientific investigation to a much-hyped coronavirus cure. This included pronouncements by President Donald Trump that he was “very confident” that hydroxychloroquine would be an effective COVID-19 treatment despite little supporting evidence of this and, later, announcing that he himself was taking it as “A lot of good things have come out about the hydroxy.”

Defenders of the president, including Anthony Fauci, described this approach to unproven coronavirus treatments as “talking about hope for people. And it’s not an unreasonable thing: to hope for people.” But as critics of these claims have pointed out, when these hopes are unsupported by evidence, they are false hopes. By making claims about coronavirus treatments that are not rooted in evidence, businesses marketing and selling these products and politicians hyping their potential are misleading the public about the danger COVID-19 still holds and the sacrifices that remain necessary to reduce its spread.

These critics are correct that promoting false hope in the face of this pandemic is morally problematic. However, the moral dimensions of this practice are more complex than simply misleading people or undermining their ability to consent to medical treatment. Important as these ethical issues are, in some cases sellers and promoters of unproven coronavirus treatments are also exploiting the public’s hope for an end to the pandemic. That is, they are taking advantage of these hopes for their own benefit in an ethically impermissible way.

Contemporary accounts of exploitation have typically focused on how specific conditions can give rise to an unfair distribution of costs and benefits resulting from interaction. For example, being the only person available to rescue the passengers of a sinking ship can allow that person to charge unusually high – or exploitative – rates for providing this service. In other cases, background injustices such as unfair trade practices allow businesses to systematically underpay their employees compared to a fair – or non-exploitative – global economic system.

While these accounts of exploitation have their merits, they are not the best way to explain the exploitation of hope. Rather, exploitation in this context constitutes a failure of respect for others, understood as disregarding their basic human needs. Simply put, interactions with others can create relationships of partial entrustment with dimensions of their well-being. This is especially the case for specific relationships and roles including medical practitioners and political leaders. Choosing simply to gain from rather than act on this entrustment can constitute exploitation.

Exploitation of this kind is present when people sell unproven coronavirus cures and politicians claim, without proof, that new treatments have been discovered or are right around the corner. Most recently, this kind of exploitation is actively taking place around hopes for the release of an effective vaccine against COVID-19. President Trump is now regularly promising that an effective vaccine for COVID-19 is imminent as part of his Operation Warp Speed push for vaccine development. In a recent, characteristic statement, he promised: “we’ll end up with a cure, we’ll end up with therapeutics, we’ll end up with a vaccine very soon.”

I’m a father of school-age children and son of older parents. I want to see my children back in school and playing with their friends, my parents safe, and my community back to something resembling normal as soon as possible. And so, I very much hope that a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19 arrives “very soon” and is widely available across the world.

However, promising that this is the case, especially when doing so is part of a pattern of misrepresentation of the dangers of the coronavirus and steps needed to prevent its spread, is not simply misleading. It is also exploitative. Politicians who make these promises, especially with an election on the horizon, disregard the responsibility entrusted to them to foster the public’s health and instead manipulate the public for electoral advantage. As Ken Frazier, the CEO of pharmaceutical company and vaccine developer Merck put it, “when we do tell people that a vaccine’s coming right away, we allow politicians to actually tell the public not to do the things that the public needs to do like wear the damn masks.”

COVID-19 has given businesses and political opportunists the chance to use the pandemic for their own benefit. By taking advantage of our desperate hope for an end to the pandemic, they are not simply misleading us or encouraging false hope. Rather, these false hopes, planted by those willing to get ahead of or outright lie about the evidence about treatments and cures, are an opportunity for exploitation. We should clearly call this behavior out and hold these exploiters responsible for their actions.

Feature image by Marc-Olivier Jodoin via Unsplash.

The post The ethics of exploiting hope during a pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

Conjunction dysfunction

Everyone of a certain age remembers the FANBOYS of Conjunction Junction fame: for, and, nor, but, or, yet and so. In the lyrics of the 1973 song, we mostly hear about and, but and or with a brief mention of or’s pessimistic cousin nor. A conjunction’s function is to “hook up words and phrase and clauses” and many of the examples are pretty simple: “Milk and honey, bread and butter, peas and rice, … Losing your shoe and a button or two.”

Over time, writers learn the connections between punctuation and the FANBOYS. We are told to use a comma before FANBOYS conjunctions when they separate clauses but not when they are separate phrases: Milk has a lot of calcium, and honey is a natural sweetener (with a comma), as opposed to This is the land of milk and honey (with no comma). But the status of the FANBOYS as a coherent word class quickly breaks down once you notice how some of them are actually used.

The words yet, for, and so are rather marginal conjunctions and mostly serve other functions. Yet is usually at work as an adverb, meaning “in addition” (yet another), “still” (yet higher rates), and with various shades of time (as yet, have yet to, Are we there yet?).

As a conjunction between clauses or sentences, the semantics of yet are a bit like but or however, indicating a contrast. What’s more, yet can hook up with and, as in this example:

I studied that problem for years, and yet I never came close to the right solution.

For is an even more flexible word. As a preposition, its meaning includes doing something on someone’s behalf (building a deck for them), specifying rewards or deserts (receive an award for work, punishment for misdeeds), indicating support or advocacy (I’m for Roosevelt) or designating an amount (a bill for $100). As a conjunction, for has a meaning which overlaps with subordinating because, though it is more formal in register. But unlike because, for only occurs after another clause. Consider this 1883 example from the Oxford English Dictionary:

This is no party question, for it touches us not as Liberals or Conservatives, but as citizens.

The for clause cannot be moved to the front, though with because, either order of clauses is possible. And while all of the other FANBOYS are able to begin sentences, the conjunction for is quite rare in that position.

Perhaps the messiest and most complex of the not-quite-conjunctions is so. The word has about forty different subentries in the Oxford English Dictionary, many of them thankfully obsolete. Adverbial uses predominate, often connecting so with a following adjective and noun clause:

An idea so preposterous that it might actually work.

So occurs as an adjective, as in That’s not so, and it has a full range of elliptical uses, where it refers to some previous mentioned wording: to do so, say so, think so, and so on. More recently so has added a function as an adverb before not:

She is so not coming.

Sentence-initial so goes way back, as in this example from Jonathan Swift’s Journal to Stella:

So you have got into Presto’s lodgings; very fine, truly!

As an interjection or introductory word, so indicates new awareness, surprise or derision, and is often –and increasingly—used to signal a topic or topic shift:

So we analyzed the data and found ….

So make a guess.

As a subordinating conjunction, so has the meaning in order to (=so that) and the so-clause can occur either before or after the main clause.

So Luella could have piano lessons, her mom worked two jobs.

Her mom worked two jobs, so Luella could have piano lessons.

Used as a coordinating conjunction, so has the sense of therefore and the clause order cannot be reversed.

I couldn’t hear a thing, so we had to leave at intermission.

The food was terrible, so we gave the place a bad review.

And so it goes. True conjunctions like and, or/nor, and but behave rather differently than the shifty words yet, for, and so. The FANBOYS acronym, which only dates from about the mid-twentieth century, misleads us into thinking that all these words will behave the same. But they are very different.

So as far as the FANBOYS are concerned, I’m not a fan.

Featured image credit: Sunset over Clapham Junction by Jon Buttle-Smith on Unsplash

The post Conjunction dysfunction appeared first on OUPblog.

August 3, 2020

Progressive American Christianity fosters racism

Theologian and priest Kelly Brown Douglas begins her book, What’s Faith Got To Do With It, with this question: if Christianity has been used for centuries to oppress black people, “Was there not something wrong with Christianity itself?” In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, many Christian leaders took to the streets in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and other anti-racist groups. Other, mostly conservative and evangelical, Christian groups immediately criticized the protests. Recently, several think pieces have implicated white evangelicalism in the historical support of white supremacy: from its justifications for slavery to Jim Crow to the present moment.

Pieces like this one from NPR unveil important truths; yet, by focusing on evangelicalism, they miss the role of progressive, even well-meaning white Christians in the development of white supremacy. Evangelicalism might be the most obvious religious culprit, but the explicit racism of conservative Christianity is propped up by a deeper, sinister, and veiled form of white supremacy within progressive, liberal Christianity: the implicit, silent, even unintentional support and silence of white progressives who fail to see the ways that all whites are implicated in white supremacy. That is, in Douglas’s words, there is something wrong with all of white Christianity, not just its evangelical believers.

By concentrating blame on conservative, evangelical Christians, and by identifying individual actors or groups as “racist” or “white supremacist,” well-meaning, progressive Christians are able to distance ourselves from material damages caused by racism, to escape blame—and the responsibility to do something about it. Yet, the theological tendencies of white supremacy are present in the work of some of our most celebrated theologians, like Walter Rauschenbusch and Reinhold Niebuhr.

The case of these two scholars illuminates the power of white supremacy to corrupt theological personalities and systems that perceive themselves to be contributors to racial equality and justice—and provide an important lesson for religious progressives today. Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr were the key figures of two of America’s most important theological movements since the Civil War: the Social Gospel and Christian Realism. Both were aware of racial injustice, and unlike many theologians and pastors of their days, they determined to use their theological perspectives to address the issue.

The Social Gospel emerged at the turn of the century, proposing to “Christianize the social order” in the face of growing economic and social crises. Yet, it was only in his last years that Rauschenbusch addressed racism; he considered it a problem limited to the American south that would gradually be resolved through economic reform. The Social Gospel’s optimistic view of human moral agency generated a confidence in gradual social change. God’s kingdom advances slowly; Christians “can afford to wait” while working for moderate social changes. This resulted in calls for patience in the struggle against racism. His insistence that we “Give it time!” only served to “Christianize” the status quo.

Further, his belief that the only hope for the “belated races” was in the work of white Christians teaching them “steady and intelligent labor, of property rights, of family fidelity,” reveals a paternalistic embrace of Social Darwinism. These “belated races” needed the assistance of more advanced races for social progress. The Social Gospel, in its eagerness to distance itself from the anti-intellectualism of fundamentalist Christianity, uncritically accepted the cultural assumptions of the racial pseudo-science of its day.

As the optimism of the Social Gospel waned in world war and depression, Reinhold Niebuhr became the key figure of Christian Realism, a theological movement sober to the sinful self-interest of society and concerned with proximate forms of order and justice. While this realism allowed him to perceive racial injustice in ways obscured for Rauschenbusch, it is also to blame for his failures. His ethical pragmatism led him to promote a “gradual and evolutionary process” of social change. He considered patience and compromise “the course of wisdom in overcoming historic injustices.” These concerns are revealed by his worry that his church would integrate too quickly, or his claim that the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling mandating the separate-but-equal policy was “a very good doctrine for its day”—because anything more radical would prompt revolt.

Displaying the tendency of white Christians to universalize and project, Niebuhr criticized “racial pride” but identified it as “a general human shortcoming.” Racism was not a product of white supremacy, but a “universal characteristic of Homo sapiens.” Niebuhr flattened the prejudice of all racial groups into a false equivalence—striking an alarming similarity to the equivocal “both sides” claims from the president regarding racism. As Traci West notes, Niebuhr’s ignorance of Harlem Renaissance artists and activists right outside his Union Theological Seminary office certainly blinded him to the particular concerns of African Americans.

The case of these two revered theologians resonates with Christianity’s historical hesitancy to lend full support to radical calls for justice—especially when those calls emerge from secular sources. Like so many progressive white scholars today, they failed to attend to the Black scholars and activists of their day and allow them to shape their concerns. They foreshadow progressive tendencies to exhaustively weigh ostensibly competing moral goods at the expense of taking concrete action, or to allow too much moral optimism or pessimism to reinforce the status quo. They portend liberals’ eagerness to distance ourselves as far as possible from our conservative counterparts in ways that allow us to smugly shield ourselves from implication in their sins.

White progressive Christianity cannot overcome these tendencies until we recognize that whiteness permeates all of our tradition; it stewed in our sanctuaries, spread with our slave ships, and was proclaimed from our pulpits and our pens. It shapes the work of some of our most revered and progressive theologians. This legacy continues to hold captive the modern, white Christian imagination. Our captivity will never be over until progressive white Christians recognize that there is something wrong with our Christianity itself—all of it—and commit to confronting our own white supremacy.

Featured image by Clay Banks on Unsplash.

The post Progressive American Christianity fosters racism appeared first on OUPblog.

August 1, 2020

Forgotten Danish philosopher K E. Løgstrup

Very little attention has been paid to Danish philosopher Knud Ejler Løgstrup in the English-speaking word until recently. His philosophical interests focused on three strains in particular: ethics, phenomenology, and theological philosophy.

He studied theology at the University of Copenhagen from 1923 until 1930, though was inclined towards the philosophical aspects of the subject. He studied with Martin Heidegger, who greatly contributed towards the field of phenomenology. The phenomenological movement was a significant influence on Løgstrup’s early reading, along with Kant, Edmund Husserl, Max Scheler, Heidegger himself, and Søren Kierkegaard.

He met his wife, Rosalie Maria Pauly, a German fellow student during his time at Freiburg. From 1936-43 he worked as a Lutheran Pastor, and in 1943, a year after his dissertation critiquing idealist epistemology was accepted, he became a professor of ethics and philosophy of religion in the theology faculty at the University of Aarhus in Denmark. Shortly after he joined the Danish resistance. The insurgency arose during World War II to rise against the Nazi occupation of Denmark.

Academics often compare the work and philosophies of Løgstrup and Emmanuel Levinas. While they held similar views, they didn’t always align. Løgstrup’s ethics focused on responsibility rather than command ethics, whereas Levinas seemed to situate himself between the two. What distinguished Løgstrup from other standard philosophers of ethics and religion was that he was concerned with pinpointing where philosophy required theology, and vice versa. Løgstrup connected these through concepts of ethics which included radical ethical demand and the gift of life.

His first major piece of writing,The Ethical Demand (1956), explored in detail the radical ethical demand concept. For Løgstrup, there is only human morality, not Christian and secular morality. Despite having much in common with Kierkegaard’s philosophy, this drifted away from traditional Kantian philosophy and Kierkegaard’s Christian existentialism, which took the perspective of morality as autonomous to the individual, and opened up the opportunity to understand ethical demand as an object placed upon by an Other. He perceived moral and ethical life from an alternative, social perspective to the standard virtue ethics and utilitarian structures: that basic human trust is involved in all human interaction.

Lutheran theology was a large part of his life in the 1930s, as he became a member of the Danish theological movement, Tidehverv. This was a strongly anti-priest movement and was considered by many to be the strongest theological movement in Denmark at the time. For Løgstrup the revival of piety within the Lutheran church, which emphasised biblical doctrine and stressed the importance of living a strongly Christian life, was incredibly irrational, and theologically far too conservative. As a result, Løgstrup was openly critical of this more extreme strain of theology, instead believing that theology should be openly considered alongside philosophy. Gradually he drifted away from the movement, which was influenced in part by the existentialist thoughts of Kierkegaard, and in the early 1950’s broke with it.

Following his retirement from the University of Aarhus in 1975, he continued contributing to philosophy, writing Metaphysics which was composed of four volumes. However, only two of the volumes had been published by the time of his death in 1981 from a heart attack.

Despite only coming into the forefront of Western moral, theological, and phenomenological philosophy in recent years, Løgstrup and his work, which include Kierkegaard’s and Heidegger’s Analysis of Existence and its Relation to Proclamation (1950), Beyond the Ethical Demand (1956), and Ethical Concepts of Problems (1971), are now receiving serious thought and examination.

This year Oxford University Press published the first three works in a new four-volume series of translations, the Selected Works of K.E Løgstrup. 2021 will see the final volume Controverting Kierkegaard publish to complete this important landmark collection.

Featured Image Credit: by Adrien Olichon via Unsplash

The post Forgotten Danish philosopher K E. Løgstrup appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers