Oxford University Press's Blog, page 140

July 16, 2020

What face masks and sex scandals have in common

While Donald Trump’s legacy will be marked by many things, we can add to the list his resistance to wearing a face mask in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which up until recently he had not done in public. The overt reason for his hesitancy to follow this mainstream medical advice is that Trump sees masks as a political statement. He has recently claimed that the public was trying to spite him by wearing masks, and has also justified his own lack of a mask as a move meant to roil up the media. Many of his supporters seem to share these sentiments. Even though officials at a recent Trump rally in Oklahoma offered masks at the door, participants overwhelmingly chose to remain unmasked despite their close physical proximity. In fact, Trump’s resistance to the practice has become so infamous that his own allies have lately begun to chide him into compliance as rising rates of the virus have contributed to his decline in the polls.

It is easy for many to dismiss Trump’s behaviors out of hand as a function of his singular dispositions. But if we want to understand why so many in the public seem to respond favorably to this latest act from the nation’s top politician, we might look to an unlikely place: the dynamics of contemporary American political sex scandals. This connection may sound outright absurd, and yet studying political sex scandals is instructive because they reveal who is able to violate the social norms in a society with little consequence. The public relations survival techniques used by those at the center of political sex scandals may shed some light on the dynamics driving our current political and health situation.

It is a virtual truism that politics is an image game. For white men in particular, marketing oneself as a cowboy of sorts has been a highly successful tactic in garnering public support, along with other images that reinforce white, aggressive hetero-masculinity. For instance, in 2004, Montana gubernatorial candidate Brian Schweitzer was able to close the gender gap among male voters with an ad that featured him on horseback, toting a gun. Similarly, during his 2008 presidential bid, Mitt Romney was scheduled for a big-game hunt ASAP after admitting that his hunting career amounted to little more than shooting at rodents.

The rhetoric of hetero-masculine imagery and aggression that successfully garners votes in an election is the same one that generates public support in a time of crisis (say, a pandemic or scandal). Indeed, a common rhetorical tactic used by those who politically survive their own sex scandals involves deploying aggressive speech positioning themselves as a protector against any number of dangerous national enemies. This move distracts from their sexual misbehavior but also makes them appear strong and virulent, as a figure necessary for national well-being. On the other hand, those politicians who are less likely to politically survive their sex scandals are often those who take the moral high road by admitting their transgressions and providing a public apology, which is often perceived by the public as weak. Put simply, the public tends to reject politicians who admit to failure, even when that same public claims to desire greater honesty and ethics in political leadership.

While there is a sizeable pool of political sex scandals that can illuminate this point, there is perhaps no better example than Rudy Giuliani, whose own sex scandals appear to have had little negative impact on his career. Giuliani is the former mayor of New York City, former presidential candidate, and current lawyer to Donald Trump. In Giuliani’s case, his highly publicized affairs and ongoing domestic disputes from the late 1990s were punctuated by a press conference in 2000 where he announced his divorce from his wife (all without informing her of the matter), introducing the name of his mistress in the same breath. Yet when 9/11 happened, Giuliani’s substantial personal liabilities all but evaporated in the minds of many. Having been granted the title “America’s Mayor,” he has gone on to sustain a career based in large part on his reputation as a figurehead of American patriotism in the fight against Osama bin Laden and foreign terrorism, more generally. Giuliani has continued to be notoriously cavalier about charges of ongoing adultery, calling it something “everyone does” and claiming that the topic has no place in the public realm because he’s confessed to his priest. Lest we forget, this is much the same tactic that Trump, himself, displayed during the 2016 election in his flat denials or sidestepping of his marital affairs, even though he discusses his sexual history quite openly in his books on business and success.

All of this indicates that white male politicians who can maintain a public persona built around images of strength, aggression, and masculinity (while also minimizing wrongdoing) are often able to break the rules because the public is more likely to choose those traits over ethical consistency. But touting this brand of masculinity is hardly the practice of elites alone. White aggressive masculinity is an emotional touchstone through which many sectors of the public read a leader as their representative, an extension of themselves. This fact is, perhaps, born out in the data indicating that American men wear masks less than American women because they perceive it as a sign of weakness, and in the recent Twitter campaign to goad men into mask-wearing that reads #realmenwearmasks.

We should thus not be surprised at Trump’s current attitude towards masks in the time of COVID-19. But as we know, viruses do not care about aggressive, masculine rhetoric. Thus it remains to be seen whether Trump’s supporters are more afraid of COVID-19 or the possibility that his persona, and the role model it provides, may prove lethal.

Featured image: President Trump in Maine, public domain via Flickr .

The post What face masks and sex scandals have in common appeared first on OUPblog.

July 15, 2020

Cut and dried, part 2: “dry”

The murky history of the verb cut was discussed two weeks ago (June 24, 2020). Now the turn of dry has come around. When people ask questions about the origin of any word, they want to know why a certain combination of sounds means what it does. Why cut, big, den, and so forth? Instead of an answer, they are often told that a word is a borrowing from another language, or they may be given a list of cognates and a reconstructed ancient root (unless the verdict is: “origin unknown”).

However, non-specialists do not need that information. They expect an etymologist to tell them when and how c-u-t, b-i-g, and d-e-n happened to acquire the meanings familiar to language speakers. They don’t realize that, outside the sound-imitative moo, bow-wow, giggle, and a few expressive verbs like jerk, which probably attempts to describe a jerking movement by verbal means, we’ll never discover the answer, even though we may sometimes try to reconstruct the impulse behind the process of word creation. The process must have been elementary, because “first words” were simple things, or so it seems. But too many centuries may stand between us and the word’s birth for the historical linguist to be able to jump over that chasm. Even some recent words, especially slang, are almost impenetrable.

So how could a word meaning “dry” come into existence? Perhaps the history of wet may suggest an approach to the problem. Wet is related to water, not derived from it as is watery, but formed on another grade of ablaut (vowel alternation) of the same root, approximately as the noun drove is formed from the root we have in the verb drive. No doubt, wet must have meant “watery” or “saturated with water.” Here the sought-for process is evident even millennia after this adjective came into existence (watery, like water, was attested in Old English). It would be good to discover some object so “existentially dry,” so devoid of moisture (dry as dust or dry as a bone) that its name could inspire the coining of the adjective. Dry, like water and watery, has been known in the language since the Old English period. Dutch droog and German trocken (the same meaning) are related, which shows that the word is old, much older than the earliest English texts, which go back only to the mid-seventh century.

A drove is called this because it is driven. Photo in the public domain via Need Pix.

A drove is called this because it is driven. Photo in the public domain via Need Pix.Another possible approach to the riddle, as often happens in etymology, is through synonyms. If we could guess the etymology of at least one word for “dry” in any language, that might help. Dry does not seem to need synonyms (the reference is so unambiguous). Yet, strangely, Old Germanic had two words meaning, as far as we can judge, the same. In the Gothic Bible, recorded in the fourth century CE, the word was þaursus (pronounced as thorsus). It occurred with reference to a withered hand and a fig tree. The cognates of this adjective occurred in the entire Germanic-speaking world. Its Modern German reflex (continuation) is dürr, and several German words have the same root, for example, dörren and its elevated synonym dorren “to dry (up).” But perhaps more interesting to us is the German noun Durst “thirst.” Durst, like thirst, is an ancient noun. Gothic also had its cognate (þaurstei, pronounced as thorstee). The corresponding Old English adjective þyrre “dry” has not continued into Modern English, but thirst, from þurst, has.

Dry as dust. Credit: NOAA George E. Marsh Album / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dry as dust. Credit: NOAA George E. Marsh Album / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Not only are draug– and thaur(s)-, the Old Germanic sources of the two adjectives for “dry,” synonyms. They sound very much alike: d and th are phonetically close, and the diphthong in the root is the same. Moreover, draug– has no related forms outside Germanic, while thaurs– does. One of them is familiar to us from Engl. torrid, a borrowing of Latin torridus “parched up.” The root of torrid is also interesting in the context of some earlier posts, because it recurs in torrent (a late borrowing from French). The Latin participle torrens meant “boiling (!), roaring, rushing,” and once again we see that water and fire tend to form a union in people’s minds. The reference is to a fierce, passionate action. See the post on brand for June 17, 2020. Later (next week), we will see that dryness and water may also be partners. (For curiosity’s sake, I may add that Engl. toast “to parch” goes back to French and further to the past participle of the same Latin verb torrēre.)

What, we wonder, is the origin of torr-, that is, what did this root refer to? What was “torrid” in the minds of those who coined this ancient Indo-European word? A close neighbor of torr– is Latin terra “land,” an almost isolated word in Indo-European. If this closeness is not an illusion, then the ancestor of torrid may have referred to scorched or at least very dry earth. The connection between terra and torrid is questionable, and one obscure word can never explain the origin of another equally obscure one. Yet, if as a last resource or for the sake of argument, we accept this connection, it would not have meant anything to Old Germanic speakers, because their word for “terra” was earth. In any case, they did have a word for “dry” (the one we have seen in Gothic þaursus). Why did they coin another one?

The root of þaurs-, as we have seen, recurs in Engl. thirst, while the root of dry recurs in Engl. drought. Could it be that the most ancient Germanic word denoting dryness referred to a parched throat, while much later, a word referring to the lack of moisture in the soil was coined from the elements of its synonym? As time went on, one of two such close synonyms was destined to disappear or modify its meaning. It therefore causes no surprise that Old English þyrre, a congener of thaurs-, has been ousted by dry, a reflex of drȳge (from draug-). Modern German has both trocken (related to dry) and dürr (related to þaursus), but they are stylistically different. All the other modern Germanic languages do with one adjective: Engl. dry, Dutch droog, Icelandic þur (from þurr), and so forth.

Such is an introduction to the history of the word for “dry” in Germanic. All we can say with some certainty is that dry is a newcomer. My idea that once upon a time there was an adjective used about a dry throat and that later a synonym (an artificial neologism) emerged referring to dry earth is an arrow into the air, though in Part 2 of this essay, I’ll try to recover it. Gothic þaursus, as we have seen, referred to a withered hand and a tree that stopped bearing fruit, but Gothic had only one word for “dry,” so it, naturally, fit(ted) all situations, and its existence sheds no light on our problem.

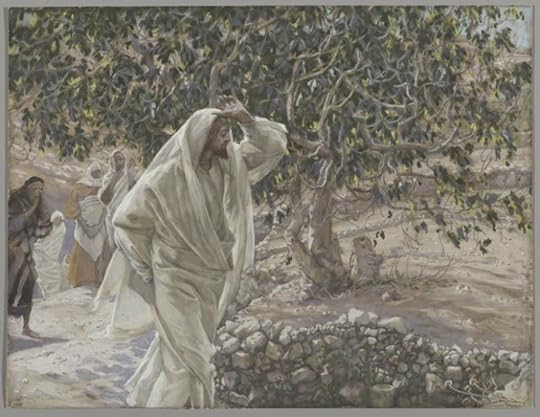

Let no fruit grow on thee henceforward…. The Accursed Fig Tree by James Tissot. Public domain via the Brooklyn Museum.

Let no fruit grow on thee henceforward…. The Accursed Fig Tree by James Tissot. Public domain via the Brooklyn Museum.Other synonyms for dry exist too, and we’ll have a look at them next week in the hope that they will tell us something about the English adjective, the main object of our investigation. At present, we have only one dubious clue to the etymology of dry, namely, a possible connection between dryness and earth. But if þaursus ~ torrid is not related to terra, then even this clue fails us.

To be continued.

Feature image credit: photo by Anthony Bley, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cut and dried, part 2: “dry” appeared first on OUPblog.

How COVID-19 could help social science researchers

The US passed 2.5 million Covid-19 cases, there are more than 10 million confirmed cases worldwide, and global deaths passed 500,000 at the end of June. We face unprecedented challenges during this global pandemic and we may see profound and permanent changes to how we do things. Surveys and digital trace data have been used extensively to study these changes, but another unique source of insight has been used much less: videos. In the following, we will focus on two ways in which social science research can study human interaction during the Covid-19 pandemic. How do people adapt to social distancing and mask-wearing? How do interactions unfold during video calls?

First, analyzing CCTV data from before and during the pandemic may allow observing changes in public behavior during the pandemic and conduct comparisons of pandemic-related interaction in different neighborhoods, regions, or countries. Surveys aimed to analyze who goes outside, how often, and how long, or who wears a mask, might suffer from social desirability; i.e., people may overstate their compliance with public norms. Videos can show us how people actually behave in public spaces during the pandemic: Who wears a mask and who does not? Are there visible differences in gender expression or age, or in different countries? Do individuals adapt their behavior if they encounter others who wear a mask, or who socially distance more or less than they do? How do people negotiate public space as the pandemic unfolds, and when do more people start to adhere to distancing and mask-wearing guidelines? Are there new ways in which people display solidarity with each other in public spaces? Today, researchers do not need to produce video data themselves, at potentially high costs and with potentially limited coverage of different sites. Instead, recordings can be collected through CCTV providers and social media sites. Some websites, such as earthcam.com, even stream CCTV camera footage from across the globe, 24 hours a day. In real-time we can watch social life during the pandemic in Tokyo, Toronto, or Times Square. We can observe social distancing on beaches in the US, Thailand, or the Maldives. These data also allow us to observe reactions to the pandemic across time. CCTV and smartphone cameras are essentially “always on,” meaning they continuously produce videos for non-academic purposes or as a byproduct of online interactions –similar to digital traces such as Google searches, as described by Matthew Salganik in his book “Bit by Bit.” This means we can go back in time and look at real-life interactions captured on CCTV before the pandemic to compare them to human interaction during and after. We can even use additional sources, such as national and local infection or death rates, to infuse the analysis with context information and analyze if and how they impact behavior on the ground.

Second, use of video conference services increased exponentially during the Covid-19 pandemic. Every day people film millions of family meetings, Friday night drinks, and business meetings. Some recordings show breakups, others marriage proposals, online teaching and students’ reactions, or toddlers playing. Direct access to such data is, of course, impossible and unwarranted; from a research ethics standpoint, we cannot just log into a video call and record people. And even collaborating with providers to analyze recordings the company keeps would be concerning from a research ethics standpoint. People may not even be aware that their, potentially very private, exchanges are stored by a company, much less did they consent to the recordings being analyzed by social scientists. But there may be a way to tap into this wealth of data on social interactions while respecting people’s privacy and the need for consent. Scholars are increasingly using mass collaboration to collect and process digital data, as shown by initiatives such as eBird, PhotoCity, Galaxy Zoo, or FoldIt. Researchers have also used collaboration to collect video data of interactions, e.g., in families, such as the New Jersey Family Study, as well as videos to train human action recognition software, such as the Charades dataset. Similar mass collaboration could allow collecting extensive video data of virtual face-to-face interactions, if people respond to a call for collaboration. This approach would entail a number of requirements: all participants in a given call would need to consent to being filmed and the video being used for research, and scholars would need to ensure the safe storing of such data and the protection of privacy. Studying these videos may provide crucial insight into social life: from speech patterns and mimicking behaviors in successful versus unsuccessful business negotiations, to gender-bias in speech interruptions during virtual workplace meetings, or emotional contagion in virtual friends’ hangouts. A large field of scholars across the social sciences assume that these types of interactions constitute the fabric of social life. They make up what we end up calling a “workplace,” “family,” “gender inequality,” or “friendship.” Beyond mundane interactions, the platforms we use so extensively at the moment also record extraordinary (and sometimes horrific) events usually not caught on video. In late May, the video-chat platform Zoom recorded a man fatally stabbing his father while the latter was in a zoom meeting with 20 other participants. The video includes not only the stabbing, but also participants’ reactions to the events, such as calling the police.

With video recordings capturing more and more aspects and moments of our social lifes, the Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbates this development. Social research has tools at hand to use such data and help us observe and understand while social life is reorganizing around us. As sociologist Randall Collins puts it: “Everything observable is an opportunity for sociological discovery.”

Featured image credit: Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash

The post How COVID-19 could help social science researchers appeared first on OUPblog.

July 14, 2020

How we experience pandemic time

COVID-19 refers not only to a virus, but to the temporality of crisis. We live “in times of COVID” or “corona time.” We yearn for the “Before Time” and prepare for the “After Time.” Where earlier assessments of pandemic time focused on rupture, we are now reckoning with an open-ended, uncertain future. This endeavour would benefit from expanding our horizon for temporal empathy—for understanding and foregrounding the plural nature of how pandemic time is experienced, depending on who one is and where one is situated.

A few months ago, mainstream temporal referents for the pandemic centred on the familiar temporality of wartime. From “frontline heroes” to the “coronavirus war economy,” from the Second World War to 9/11: governments described COVID-19 as a war to be won. Critics have since argued that wartime is an uneven comparison with our present—that it invites racism, enables state intervention into individual freedoms, and conceals deficiencies in the economic model upon which public health operates. However, war rhetoric offered the primary temporal model for narrativizing the uncertainties of the pandemic, particularly in the UK, in part because it ascribes agency and a sense of control. It suggests we “fight against” something unseen, and it promotes a sense of resolve, for example, by encouraging connections between “Stay at Home” discourse and the Blitz spirit.

Fundamentally, war rhetoric also helps us to manage our anxieties about the future. For temporal uncertainty is at the heart of how one experiences wartime—we assume wartime ends, but we don’t know when or how, so we live in a suspended present. This temporal anxiety can be termed “chronophobia”: a fear or dread of time, particularly that of the future.

In this sense, the years surrounding the Second World War might in fact be insightful for our present: not because we are at war, but because chronophobia was the temporal surround from the interwar through to the post-war period. There was a decades-long build-up to the Second World War, such that the feeling or expectation of wartime began far before 1939. Subsequently, the war’s atomic end was the beginning of a third, chilly conflict. So the mid-century present was a constant victim to a seemingly inevitable future of catastrophe.

Paul Saint-Amour calls the psychic impact of anticipatory anxiety from this period “pre-traumatic stress syndrome.” It turns out this is a diagnosis (or rather, prognosis) shared by an American physician, Alison Block, earlier this March:

…the health-care workers I know are suffering from a unique brand of psychological distress. I won’t call it anxiety, which the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) describes as “excessive worry,” because there’s nothing excessive about it. I would describe what we’re suffering from as pre-traumatic stress disorder… Doctors and nurses see news from our colleagues in China, South Korea and Italy, letting us know in no uncertain terms what is coming. The result is that we are all feeling the psychological ramifications of the trauma. We just haven’t experienced the trauma yet.

Block points to feelings of belatedness or inevitability in pandemic time, but she also highlights the temporally syncopated nature of the crisis. Both aspects of pandemic time are represented by the data visualization of the curve. On one hand, the curve globally emplots the suspension we feel as we watch cases rise and peak; on the other hand, it maps together different pandemic trajectories from different temporal periods and geographical locations. These two temporal modes, belatedness and syncopation, inspired the various “missives” that were sent “across” corona time over the past few months. These include letters from one coronavirus-stricken country to another not yet far along their curve, and videos filmed to warn one’s past, pre-pandemic self of the crisis to come.

COVID-19 has now been with us long enough for us to see some countries passing their peaks and flattening their curves; other countries experiencing subsequent spikes in cases following from their peaks; and other countries still only just beginning their pandemic journey. To “battle” COVID-19, as Block says, we need to cultivate temporal empathy. We need to bear in mind that our present isn’t another’s present: that we aren’t all living within the same temporality or experience of pandemic time, even if we exist in an entwined global affect or collective sense of chronophobia. We occupy dissonant, even if interconnected, rhythms. Of course, this is still a reflection of pandemic time before it becomes what Reinhart Kosselleck calls a “future past” or “superseded former future.” Only time will tell.

Featured image: Photo by Murray Campbell on Unsplash

The post How we experience pandemic time appeared first on OUPblog.

July 13, 2020

How to listen when debating

Those Americans who call themselves Republicans are disinclined to take seriously the views of those Americans who vote for the Democrats; and those Democrats will rarely see merit in the views of Republicans. Few Israelis will give ear to the cause of the Palestinians; and few prisoners in Gaza will defend the right of the Israelis to occupy the West Bank. Sunni and Shia in Iraq; Hindu and Muslim in India; Magyars and Gypsies in Hungary – one needs a mirror in order to see both sides of a coin at the same time. In the United Kingdom, those who voted to leave the European Union refuse to concede anything to those who voted to remain, and vice versa. The percentage of votes cast in 2016, on both sides, would be repeated, give or take a percentage point here or there, if the referendum was held again now.

I used to be a visiting lecturer, annually, in Transylvania, a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that was transferred from Hungary to Romania by the Treaty of Trianon, in 1920. A sizeable minority calls itself Hungarian: its members speak Hungarian at home; they send their children to Hungarian-speaking schools, who then seek employment in Hungarian-speaking sectors of the economy, and who vote for the Union of Democratic Hungarians in Romania. Few Romanians learn Hungarian; and few Hungarians learn Romanian. Relations between the two communities are amicable enough but there can hardly be said to be a meeting of minds.

I now teach a course to second-year undergraduates in Poland on the art of argument. The objective is to help them to make a case in an essay, dissertation, or oral presentation. They’re unused to the protocols of formal debate, as perhaps students in the United Kingdom are now. I recall that as an undergraduate myself I was called on to speak in a debate whose motion was: “This house believes that the Royal Family should be sent back to Hanover.” I recommend to students that they frame their essay title in question form: “Is there anything to be said for monarchy?” for example, to which they will intuitively give the answer Yes, or No – as we all would according to our knowledge and experience. I advise the students, if their intuition is to answer Yes, to examine the No position first, and if their answer would be No, to consider the Yes case first, being careful not to misrepresent it.

They find this difficult. I pose a number of questions in class (“Do schools teach what students need to learn?” “Should we all be eating less meat?” and so on), and quiz them about what their intuitive answer would be, and what the counter argument might be. I send them – along with a choice of questions – a diagram of the essay structure that I’ve proposed; but when it comes to submitting their online essay response, only a minority of them look at a counter argument and do it justice. The temptation is too strong to state their position at the outset, and to go straight into a catalogue of reasons to support it. Often, they’ll only then briefly consider a rival point of view, before confirming their original position in what’s bound to be a conclusion that has an arbitrary look to it, and that, therefore, fails to convince. In most cases, I send the essay back, recommending – if there are two cases – that they reverse them.

When I spoke in that debate about the monarchy, I was asked to oppose the motion, even though, at the time, I was something of a (small r) republican, remaining resolutely in my seat during the National Anthem. In planning my speech, I persuaded myself that there was a case for preserving a focus for pomp, separate from the centre of real power. When I tell my Polish students this story, and illustrate it by reference to the political set-up in Russia (and, indeed, in the United States), they nod in agreement. It doesn’t reduce the number of one-sided essays that I receive, though, and send back with a gentle admonition to consider what one who prosecutes the motion might have to say before they rush to oppose it. I know how Sisyphus must have felt.

Featured image: public domain via Unsplash.

The post How to listen when debating appeared first on OUPblog.

Testing Einstein’s theory of relativity

Albert Einstein is often held up as the epitome of the scientist. He’s the poster child for genius. Yet he was not perfect. He was human and subject to many of the same foibles as the rest of us. His personal life was complicated, featuring divorce and extramarital affairs.

Though most of us would sell our in-laws to achieve a tenth of what he did, his science wasn’t perfect either: while he was a founder of what came to be called Quantum Mechanics, he disagreed with other scientists about what it all meant, and he once thought he had proved that gravitational waves could not exist (an anonymous reviewer of his paper found his mistake and set him straight). Yet Einstein did create one thing that, as far as we can tell, is as correct as anything can be in science. That is his theory of gravity, called General Relativity.

He presented the theory to the world over four consecutive Wednesdays in November 1915 in lectures at the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Einstein was by then well respected in European physics circles, and one can imagine more than one person in the audience that November thinking that he’d gone bonkers. Einstein’s theory purported to replace the hugely successful 1687 gravity theory of Isaac Newton, which posited gravity as an attractive force between masses, with one where gravity was a result of the curving and warping of space and time by massive objects. And the evidence for this new theory? It managed to account for a tiny discrepancy of 120 kilometers per year in the spot where Mercury makes its closest approach to the Sun. The concepts behind this new theory were so radical and unfamiliar that it was said that only three people in the world understood it.

Yet a few people, like David Hilbert in Germany, Willem de Sitter in the Netherlands, and Arthur Eddington in England grasped the startling implications of this theory. Within four years, Eddington would propel Einstein to science superstardom with the announcement that his team of astronomers had detected the bending of starlight by the Sun’s gravity and had found that it agreed with Einstein’s prediction, not Newton’s. Newspapers around the world proclaimed, “Einstein theory triumphs.”

And that was pretty much it for General Relativity for the next 40 years. Because it was perceived as predicting only tiny corrections to Newtonian gravity, and as being virtually incomprehensible, the subject receded into the background of physics and astronomy. Einstein’s theory was quickly superseded by other areas, such as nuclear, atomic and solid-state physics, which were viewed as of both fundamental and practical importance.

Yet in the 1960s, a remarkable renaissance began for Einstein’s theory, fueled by discoveries such as quasars, spinning neutron stars (pulsars), the background radiation left over from the big bang, and the first black holes. Precise new techniques, exploiting lasers, atomic clocks, ultralow temperatures, and spacecraft, made it possible to put General Relativity to the test of experiment as never before. During the subsequent decades, researchers performed literally hundreds of new experiments and observations to check Einstein’s theory. Some of these were improved versions of Einstein’s original tests involving Mercury and the motion of light. Others were entirely new tests, probing aspects of gravity that Einstein himself had never conceived of. Many were centered in the solar system using planets and spacecraft, or in sophisticated laboratories on Earth. Others exploited systems called “binary pulsars,” consisting of two neutron stars revolving around each other. More recently we have witnessed numerous gravitational wave observations by the LIGO-Virgo instruments, the study of stars orbiting the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, and the stunning image of the black hole “shadow” in the galaxy M87.

In this vast and diverse array of measurements, scientists have not found a single deviation from the predictions of general relativity. When you consider that the theory we are using today is the same as the one revealed in November 1915, this string of successes is rather astounding. After more than 100 years, it seems Einstein is still right.

Will this perfect record hold up? We do know, for example, that the expansion of the universe is speeding up, not slowing down, as standard general relativity predicts. Will this require a radical new theory of gravity, or can we make do with a minimal tweak of general relativity? As we make better observations of black holes, neutron stars and gravitational waves, will the theory still pass the test? Time will tell.

Featured Image Credit: by Roman Mager via Unsplash

The post Testing Einstein’s theory of relativity appeared first on OUPblog.

July 12, 2020

How companies can use social media to plan for the future

Many organisations use scenario planning to explore uncertainties in their future operating environments and develop new strategies. Scenario planning is a structured method for imagining possible futures based on the identification of key uncertainties in the external environment, and it may involve a variety of stakeholder groups from inside and outside the main organisation, including employees and potential clients or customers. Companies often run such projects using facilitated workshops. These workshops typically require people to be physically present in order to participate and engage with others. What to do today? How can we do strategy – or have a useful strategic conversation about the future of an organisation – when we cannot get together in the usual way, in a room with flipcharts, whiteboards, etc.? When will be able to hold face-to-face strategy workshops again? And, in the aftermath of the current pandemic, will the practice of strategy change, to place less emphasis on bringing people together in the same room?

In an era of widespread use of social media, scenario planning exercises should be adapted to allow people to interact with each other virtually. A good example of how this might be achieved is provided by the use of Twitter within a project to plan for the future of food systems around Birmingham, UK, in 2050. The project set out to describe some inspiring food futures that challenge current thinking about how people feed themselves, particularly when most of us live in cities, and was led by Kate Cooper, now executive director of the Birmingham Food Council.

The project began with a series of six face-to-face events, involving scientists and others with expertise in architecture, biochemistry, bio-energy, chemical engineering, computer science, entomology, food distribution, geography, horticulture, plant science, public health, and veterinary epidemiology. A specialist team supported each event by managing live social media reporting. Reporting took the form of live Twitter postings to promote the events and engage non-attendees.

Some of the social media activity was predictable. Team members tweeted just before each event, to promote it and stimulate interest. However, some of the findings were more surprising. The Twitter activity suggests, first, that the project’s approach to the use of social media was successful in bringing a diverse set of people with different perspectives and interests into the conversation – and this is surely a valuable attribute of a strategy exercise that is aiming to think broadly and consider a wide range of possible futures and strategies relating to an important issue. Second, the conversations that took place on Twitter did not develop around a single theme; instead many conversations developed, often around a number of hot topics. One such hot topic resulted in a series of Tweets around food deserts, urban areas in which it is difficult to buy affordable or good-quality fresh food. Third, the conversations were not confined to the workshops themselves; they continued between the face-to-face events, perhaps leading to more thoughtful contributions from participants.

This project suggests that companies can use social media effectively as part of a scenario planning activity, to engage participants, encourage contributions to the project, and support ongoing conversations. The use of social media may even provide participants with the opportunity to reflect on the thorny issues under discussion, and make additional contributions at a moment when they have fully considered a range of possible arguments and different perspectives on the problem.

One successful way to promote engagement on social media to pose a series of questions in order to encourage Twitter followers to respond and express an opinion. Two examples of such questions were “Could we use sea water/grey water for flushing toilets instead of expensive drinking quality water?” and “Should we give up on educating the old and concentrate on the young to get the message through about food sustainability?” Such questions, and participants’ responses, may be particularly valuable in the brainstorming stages of a scenario planning exercise, where the organisers are asking participants to think creatively to identify unpredictable factors that will help to shape the future, or suggest new strategies to deal with those uncertainties.

These potential developments are particularly important during the current global pandemic when organisations cannot always carry out meetings face-to-face; they have implications for changing scenario planning and other strategy development exercises. In such uncertain times, we surely need good approaches to the practice of strategy – now more than ever!

Feature Image Credit: by Sara Kurfeß via Unsplash so

The post How companies can use social media to plan for the future appeared first on OUPblog.

How Broadway’s Hamilton contributes to the long history of small screen racial discourse

On 3 July 2020, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton—perhaps somewhat inadvertently—took its place alongside decades of Broadway shows and stars which had helped foster an awareness of American race relations via the small screen. When Disney won the $75 million bidding war for the global theatrical distribution rights of Hamilton, the filmed recording of the show’s original cast performing on the stage of the Richard Rodgers Theatre was just another feather in the media monolith’s cap. Disney soon announced a planned October 2021 theatrical release, to be followed by a Disney+ streaming run the next year.

But then COVID-19 shuttered theatres and shelved Summer blockbusters. Suddenly, Disney was throwing Hamilton straight to its hot streaming service for Independence Day weekend. America’s birthday was coming with a hip-hop beat, wrapped in Mickey Mouse paper, and to be enjoyed from the safety of folks’ own digital devices. Then less than two weeks later, George Floyd was killed by a policeman’s knee to his neck. Amid nationwide floods of anti-racist and police reform protests, Disney’s decision to premiere Hamilton on 3 July suddenly took on a whole new, politicized meaning.

Miranda’s story of immigrants, rebellion, and America’s Founding Fathers, as told through Black and brown bodies, came to an American audience still quasi-shuttered by a pandemic and experiencing perhaps the most significant anti-racist uprising in half a century. Hamilton was not just another big budget Disney deal, but a conveniently placed reckoning with the nation’s racist past and present. The Tony-winner became part of a storied history of musicals helping to frame racial discourse from the comfort of America’s living rooms.

When only 9% of US households even had TVs, chart-topping singer and acclaimed actress Ethel Waters dropped truth bombs on Perry Como’s Kraft Music Hall, performing Moss Hart and Irving Berlin’s “Supper Time.” From the 1933 Broadway revue As Thousands Cheer, the gut-wrenching number follows a woman futilely preparing for dinner after receiving news of her husband’s lynching. Six years later producers blocked Twilight Zone legend Rod Serling’s self-penned Emmett Till-inspired television drama from airing on the United States Steel Hour, even though he had switched the victim from a young African American in the South to a Jew in New England. Advertisers still found it too uncomfortably close to the controversial case. But Waters’ painful musical reflection on America’s grotesque history of lynching made it on the air under the cover of legit Broadway fare.

Broadway’s stars and shows provided recurring overt and subtle nods to shifting and contentious race relations in the United States. Five years before Loving vs. Virginia struck down anti-miscegenation laws, The Ed Sullivan Show featured duets by Diahann Carroll and Richard Kiley, the singing stars of Richard Rodgers’ 1962 interracial Broadway romance No Strings. Over the decades, the impresario featured Broadway’s biggest African American names, often providing serious or tongue-in-cheek commentary on the nation’s racial struggles, including Sammy Davis Jr. and Company performing Golden Boy’s “Don’t Forget 127th Street” and heavyweight champion and activist Muhammad Ali and Company performing “We Came in Chains” from the 1970 Black activism flop Big Time Buck White.

In the late 60s, Black and white musical stars alike used the medium to position themselves within American racial politics. Two days prior to MLK Jr.’s assassination, pop singer and co-star of Francis Ford Coppola’s Finian’s Rainbow (1968), Petula Clark, found herself in hot water after gently grasping the elbow of her African American guest star, celebrated singer, actor, and outspoken Civil Rights activist Harry Belafonte during a taping of her special, Petula. After the taboo-touch during “On the Path to Glory,” Chrysler’s advertising manager demanded (and failed to gain) a reshoot. The ad man later claimed he had just been really tired, not racist.

One year later, Pearl Bailey and Carol Channing: On Broadway and An Evening with Julie Andrews and Harry Belafonte featured high-profile interracial double-bills. The two divas concluded their Broadway tribute with the Civil Rights anthem “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free,” punctuated by the camera heavy-handedly zooming in on their contrasting hands clasped together in unity. Later that year Tony-winning director/choreographer Gower Champion overtly marketed the Andrews/Belafonte special on their romantic chemistry. No elbow grazing here; the two danced, touched, and embraced on-screen and in promotional materials. Although ABC received 75 at-times racial-slur-laced letters of disapproval in response, Marva Spellman of the State University of NY Urban Center claimed in the New York Times that “the program was memorable because it showed in this riot torn assassination prone, seething society of racism and revolution two beautiful people, two lovely human beings, one white and one Black, delighting in beautiful music and in each other’s beauty and talent.” She went on to say the show “probably did more for race relations in our beleaguered United States than many, many hours of intellectual befuddlement from professors with PhDs”.

Of course, not all performances aged well. The 1970s brought some truly weird moments of racialized musical television, like Jack Lemmon’s 1972 cringeworthily, exaggerated “Blackvoice” rendition of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” from Porgy and Bess on Martin Charnin’s ‘S Wonderful, ‘S Marvelous, ‘S Gershwin. Six years later, Sammy Davis Jr. appeared in Steve and Eydie Celebrate Irving Berlin, alternating between an exaggerated Blackface/Blackvoice character, a dapper businessman, and a dude in a Travolta-esque disco suit in a bit celebrating “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” Although not alone in their uncomfortable racializations of Broadway, these two moments stand out as uniquely strange.

With new distribution systems came new productions foregrounding stories of racial struggle and African American genius: shows like Sophisticated Ladies (1981) live from Broadway on pay-per-view and productions of Eubie! (1981) and Purlie (1981) on the premium Showtime channel’s Broadway on Showtime. As Disney+ snagged Hamilton during this modern moment of racial unrest, it became part of this story. To quote Miranda himself, “who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” As it turns out, the story has historically been set to a toe-tapping tune and courtesy of this week’s sponsor.

Featured Image Credit: by Alexander Antropov via Pixabay

The post How Broadway’s Hamilton contributes to the long history of small screen racial discourse appeared first on OUPblog.

July 11, 2020

How governments can promote real diversity

As with most of contemporary life, the pandemic has magnified the impacts of unequal access to technologically innovative employment on livelihoods. The COVID-19 digital divide has meant that some people continue to safely work and earn from home, while others are forced to decide whether to endure physical risk in order to get to work, or to stay home, and risk their family’s financial well-being.

As The Economist recently asserted, this is one reason why getting a more diverse representation in innovative activities and places, like Silicon Valley, which are often digitally-enabled, has never been more urgent. The pressure from the pandemic came on top of the earlier awareness that modern technological advance offers both opportunities—for productivity advances, highly-skilled employment—and substantial challenges, as automation that threatens to destroy a large swath of jobs that have been the basis of people’s livelihoods. Technological innovation is connected to massive structural inequalities, by causing job losses for those already vulnerable while endowing founders and investors with even greater wealth.

Inclusive innovation is a phrase used to capture efforts, especially government policies, aimed at improving the participation of broader society in innovation. Inclusive innovation policies strive to alleviate the under-representation of certain demographic groups (identified with reference to gender, ethnicity, sexuality and disability status) in innovative activities, such as working in the high-technology sector. Many such strategies focus on increasing the number of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields and as entrepreneurs, for instance. Government policies acknowledge the range of causes of under-representation, including constraints on the supply of labour (insufficient training or desire to participate, which leads to a small set of initial applicants from under-represented groups), as well as demand-side challenges (conscious or subconscious preferences on the part of investors and employers that inhibit sufficient investment in, or employment of, applicants based upon demographic traits).

But how can policy promote inclusive innovation? Many governments have earmarked pots of money according to underrepresented demographic groups. Governments provide money, in the form of research and development spending or start-up loans, for particular groups in an effort to increase their participation in both basic research and entrepreneurial activities in innovative sectors. Other efforts include investment in human capital, in the form of skills training—for example, coding boot-camps, or STEM education. The idea for skills training is that an insufficient set of specialized skills is excluding particular demographic groups from work in innovative sectors. Yet another strategy is to set a quota for participation, as the highly-covered Norwegian boardroom quota has done.

But, there is another tack to drive more inclusive innovation: social capital accumulation strategies. Rather than providing funding or specific skills training, policymakers can run campaigns, networking schemes, and mentorship programmes to help excluded people develop the necessary links they need in order to operate as entrepreneurs or in the technology sector.

Without personal connections, and without indications of the right experiences and networks, under-represented demographic groups may struggle to break into employment in innovative sectors. In turn, their lack of aspiration to, or confidence in the accessibility of, such employment opportunities then prevents would-be investors or employers from effectively evaluating their abilities. Social capital accumulation policies, then, aim to remedy such deficiencies by forging connections among members of the innovation system, and running campaigns to promote more inclusive practices. Some social capital strategies specifically target particular demographic groups, while others aim to change the preferences of the broader innovation and entrepreneurship communities.

Part of the strategy involves building connections within groups, such as Innovate UK’s Women in Innovation programme, which requires women-to-women mentorship. The logic is that the developing close relationships with others in one’s demographic group who have already made it can provide the social boost that is needed to break in. Another part of the strategy involves working to connect people from under-represented demographic groups with contacts across the innovation system. For example, the Inclusive Innovation Initiative, run by the U.S. Minority Business Development Agency, connects minority entrepreneurs with federal laboratories, so they can access new technology. Beyond the social connections within groups, and across wider society, strategies also aim to update norms. Role model campaigns are a popular bonding tools for encouraging empowerment. Bridging strategies can also take the form of campaigns, but are designed to update the norms of wider society in order to address conscious and unconscious bias.

There’s encouraging evidence that these social capital accumulation strategies are working. But, much of the evidence has – thus far – been more anecdotal than systematic. And, perhaps more worryingly, policymakers are not yet listening. We need to do more to empower people and promote inclusive norms across society.

Featured Image Credit: “Photo Of People Near Wooden Table” by fauxels. CCO public domain via Pexels.

The post How governments can promote real diversity appeared first on OUPblog.

A little jazz piano: exploring the building blocks of music

Soon after the COVID-19 lockdown started, I began doing combined piano and theory lessons with my daughter, who is eleven, and her friend, who is a year or two older, using Skype. I tried to show them a little about some different functions that help to build a piece of music, and in the end I decided to write a set of three short jazz-style pieces for the piano, to highlight a few things I had learned, and help make it fun for them.

When I was their age, I was a boy chorister in King’s College Choir in Cambridge. We learned music within that context by developing our musical instincts to a very high degree. I found I had a very good concept of sound and musical shape but it took a while for me to be able to identify how all this related to the technical building blocks of music and how they were made to function together. The discovery of the modes of construction of music with all their different dimensions was a thrilling thing for me, and gave me seeds of confidence to imagine that I might one day be able to write music myself.

So I tried to show some simple concepts to my daughter and her friend. The first thing I focused on was harmony, and for this I chose to feature quartal harmony – harmony that is built on perfect fourths. Quartal harmony does not only have quite a contemporary sound but also a mobile and fluid function within the harmonic language of a piece. And, within a build up of fourths, there is an inevitable seventh which is a key interval in jazz harmony.

We also learned about root position chords, and first and second inversions of chords. It is always exciting to see how a different inversion of a chord changes the colour and the feel of the sound of the chord and how the inversions end up relating to the root they come from.

I also taught them about the 60 chords in jazz, something I learned years ago from an Oscar Peterson tutorial. This is a sequence of five chords, C Major 7, C 7 (add B flat), C Minor 7 (add E flat,) C half diminished (add G flat), C diminished (change the B flat to A). You can play this sequence in every key (hence the 60 chords) and there was a time when I could play these chords quite quickly and without mistakes. Not now!

I also tried to show the importance of understanding and building musical line. Line and shape help us not only to understand the building blocks of a piece, but also the breath shape of a piece, and for performers good line can be a hard thing to achieve. The second piece I wrote has a melody where both the hands move largely in parallel and it requires a good sense of where the fingers are to make a good line.

And lastly, I wrote a very simple piece with a walking bass line with the intention of helping a pianist to learn independence of the right and left hands (jazz is really good for this), and also to maintain a good and constant sense of pulse. As musicians we need to not only learn to internalize pulse and rhythm, but also learn to coordinate reaction of thought with the motor function of the hands and know where they are and where they have to go on your instrument. I suggested to my daughter’s friend that he should watch a video of the pianist Yuja Wang playing the Toccata by Prokofiev, which is a spectacular example of this kind of function.

As someone who writes choral music nearly all of the time, I loved writing these little pieces for piano. I had to think a lot about style, articulation, and how to identify and project the character of each of the pieces. It has been such a lovely process trying to communicate these thoughts to my daughter and her friend. I hope they have learned something. I certainly have.

Featured image: Piano Colorful rainbow paint vector background image by Superbeam, via Shutterstock .

The post A little jazz piano: exploring the building blocks of music appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers