Oxford University Press's Blog, page 142

July 6, 2020

Accept death to promote health

We all die and, despite some fanciful ideas to the contrary, we will, as a species, continue to do so. Our daily routines tend to distract us from this fact. However, because death is inevitable, we need to think about how we can live healthy lives, without ignoring how they end.

Once we accept that we are going to die, how we spend our money and our time on health begins to shift. At core, we should aspire to die healthy. That means focusing our energy on creating a world that maximizes health right up until the moment we leave it, rather than one where we invest our resources into the last few months of life, ignoring the factors that keep us healthy all the years prior. This would represent a radical shift in how we think about our limited health investment dollars. Perhaps death can help focus our mind on living better, on the conditions that we need to create in order to generate health.

Of course, we should not neglect the experience of dying. We all wish to die with dignity, yet we do little, in advance, to influence the circumstances of our deaths. Two out of three Americans do not have advance directives that guide what treatments they receive if they are sick, and they cannot communicate the end-of-life care that they want. Engaging in a dialogue about how we manage the dying process can help us correct this oversight.

It is also important to remember those who are left. The dead leave behind the grieving, who can experience a burden of poor health that is directly linked to loss of their loved one. The sudden, unexpected death of a loved one is, for example, the largest contributor to posttraumatic stress disorder in populations. Death leaves behind lonely older adults, now socially isolated, placing them at higher risk of dying sooner. In this way, death creates a population health challenge for the living, one that is foreseeable and, perhaps, preventable.

Our squeamishness in talking about death is entirely natural. But it remains our collective role to elevate issues that influence the health of populations; death is one of those issues. Perhaps recognizing the inevitability of death can guide us toward ways in which we can live healthier, die with dignity, and ensure our loved ones are supported when we pass on.

Featured image via Pixabay.

The post Accept death to promote health appeared first on OUPblog.

July 5, 2020

Don’t vote for the honeyfuggler

In 1912, William Howard Taft—not a man known for eloquence—sent journalists to the dictionary when he used the word honeyfuggle. Honey-what, you may be thinking.

It turns out that honeyfuggler is an old American term for someone who deceives others folks by flattering them. It can be spelled with one g or two and sometimes with an o replacing the u. To honeyfuggle is to sweet talk, but also to bamboozle, bumfuzzle, or hornswoggle.

The word has some twists and turns in its history. According to both the Oxford English Dictionary and the Dictionary of American Regional English, it was first recorded as a Kentucky term in 1829 with the definition “to quiz” or “to cozen,” both of which at the time meant to dupe.

The earliest example in the Newspapers.com database is from an 1841 story in a Tennessee newspaper, the Rutherford Telegraph, in which an editor used the term to mean insincere flattery. He said of the Speaker of the Tennessee state senate that “Some may say it is impolitic of me to talk thus plainly about Mr. Turney, and think it better to honey-fuggle and plaster over with soft-soap to potent a Senator.”

An 1848 report from the New Orleans Picayune refers to swindlers as honey-fuglers. An example from the Mississippi Free Trader in 1849 talks about political trickery intended “to honeyfuggle one party and exterminate the other,” and another Southern paper that year reported on a speech of General Sam Houston who attempted “to honey-fuggle the good hearers and get up a general hurrah of ‘Old Sam’.” The term remained in use in the second half of the nineteenth century, with a couple of hundred examples in newspapers around the country. It was used occasionally as a noun, and sometimes had the variants honeyfunk or honeyfuddle and it could mean also “snuggle up to” or “publically display affection.”

Honeyfuggle remained a marginal term, often characterized as slang or as a regionalism, but it popped into the national consciousness when Taft deployed it to characterize his predecessor and then-rival for the 1912 Republican presidential nomination. In a speech in Cambridge, Ohio, Taft said:

I hold that the man is a demagogue and a flatterer who comes out and tells the people that they know it all. I hate a flatterer. I like a man to tell the truth straight out, and I hate to see a man try to honeyfuggle the people by telling them something he doesn’t believe.

Teddy Roosevelt had plently to say about his former protégé Taft as well, calling him a fathead, a puzzlewit, and a flubdub. Woodrow Wilson won the presidency that year.

Taft’s speech popularized honeyfuggle for a time, and in 1915 the Los Angeles Express even reported on a socialite named Miss Queenie Alvarez, who concocted a soft-drink known as the Honey Fuggle made with sweet fruit juices.

Honeyfuggle still never quite caught on as a drink or as a mainstream English expression, perhaps because of the near homophony of fuggle with a different f-word. But it made a brief reappearance in presidential news in 1934 when the Syracuse Herald referred to another President Roosevelt as “the prize honeyfuggler of his time.” And in 1946, the word appeared in the title of a novel by author Virginia Dare: Honeyfogling Time. A reviewer explained that the book “takes its title from “a colloquialism popular in the Middle West of the Eighteen Eighties,” referring to “dishonest intentions” concealed “by honeyed words and promises.”

Where does honeyfuggle come from? One theory, found in Bartlett’s 1848 Dictionary of Americanisms is that it is a variation of a British English dialect word coneyfogle, which meant to hoodwink or cajole by flattery. Coney is an old word for an adult rabbit and was sometimes used to indicate a person who was gullible. Fugle, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is older dialect term meaning “to trick or deceive.” So to coneyfogle or coneyfugle meant to cheat a mark.

Today the OED reports that honeyfuggle is “Now somewhat dated.” Perhaps we should try revive it.

Featured Image Credit: by Sonja Langford on Unsplash

The post Don’t vote for the honeyfuggler appeared first on OUPblog.

Why are there different welfare states in the Middle East and North Africa

Most political regimes in the Middle East and North Africa are non-democratic, but the lived reality of authoritarian rule differs widely across countries. This difference is particularly apparent when it comes to social policies. While resource-abundant, labour-scarce regimes in the Arab Gulf have all established generous welfare regimes, the picture among labour-abundant regimes in the region – that is, in countries with a large population relative to their natural resource endowment – is one of divergence. For example, in the late 2000s the percentage of people with health insurance was between 75 and 90 per cent in Iran, Tunisia, and Algeria, compared to 55 percent in Egypt and 20-30 percent in Morocco and Syria. High levels of coverage are associated with significantly faster improvements of life expectancy over the past four decades. The situation is similar in the realm of education where enrolment expanded nearly twice as fast in Tunisia and Iran (and 50 per cent faster in Algeria) compared to other labour-abundant countries in the region. As examples abound, the key question is why some authoritarian regimes have provided welfare broadly and generously to their citizens and others have not.

The divergence of welfare regimes started very early, coinciding with the formation of authoritarian regimes in the 1950s and 60s – and the late 1970s in the case of Iran. Secondly, welfare regimes have been very path dependent and, despite important changes to economies in the Middle East and North Africa with the advent of neoliberal reforms, episodes of systemic and sustained welfare retrenchment have been mostly absent as spending patterns reverted back to their long-term trend. This, in turn, points to the long-lasting effect of authoritarian support coalitions which underlie different welfare regimes.

Broad coalitions span large cross-sections of the populations, including working and lower middle classes. They emerge when major conflicts between elites at the moment of regime formation cannot be reconciled or repressed. Different elite groups have incentives to broaden their coalitions to outcompete on another. Social policies catering to lower income groups in society thereby become the ‘cement’ which keeps these broader coalitions together. Salient communal cleavages – for example, between different ethnic or religious groups in society – can derail this process as they give elites incentives to build coalitions that rely more on outside groups. As a result, coalitions become narrow. Coalitions are also narrow if elites remain cohesive and therefore see no need to share the spoils on a large scale with the population at large.

But incentives are not everything. In a geopolitical challenging environment, such as the Middle East, regimes have often faced the need not only to secure their rule against threats from the inside, but also those coming from the outside. Such external threats – take, for example, the Arab-Israeli conflict – put acute pressure on social spending, which only resource-abundant regimes can avoid.

There are three distinct pathways of welfare provision: authoritarian welfare states, such as Tunisia or post-1979, had both the incentive and ability to provide welfare; broad welfare provision in the form of widely accessibly but generally underfunded social policies are characteristic of regimes such as Egypt that struggled to square the circle between strong incentives but very limited ability to provide social welfare as a result of acute external threats; and minimal-segmented provision which either does not give social policies much attention (such as Morocco until the late 2010s) or builds relatively generous welfare regimes yet with high barriers to access. Such segmented welfare regimes are particularly frequent in regimes with salient communal cleavages, such as Jordan where the state has historically favoured the East Bank population at the expense of the Palestinian population.

Tunisia and Egypt are examples of two different welfare regimes. The Egyptian case is theoretically particularly intriguing as it sheds light on the mechanisms through which regimes sought to mitigate the dilemma between “butter and guns”. The key notion here is cheap social policies which have allowed the Egyptian state since the 1950s not only to dole out popular, yet cost-effective social policies, but also – paradoxically – to use social policies as means to generate funds. The establishment of the country’s social security system in the 1950s was conceived from the beginning as a “powerful source of money that the government can rely on.” Related to that it’s clear that legal extensions of social security coverage – such as the inclusion of agricultural workers or students – systematically coincide with major shortages of foreign currency reserves in Egypt. This makes sense if we see social security contributions as a form of forced saving to curb domestic consumption.

Understanding the political economy underpinning welfare provision in the Middle East not only allow us to make better sense of different levels of welfare provision in the region, it also challenges widespread narratives about a region-wide, universal roll-back of welfare states with the advent of neoliberal reforms. These changes show that the extent of welfare retrenchment was itself a function of the way in which welfare regimes had been created in the first place. Finally, we should be sceptical about the oft-assumed link between social policies and regime stability. As social policies can engender and empower new societal groups as well as spawn widespread expectations about social mobility, they can have unintended consequences for authoritarian regime stability in the long run.bh

Featured Image Credit: by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

The post Why are there different welfare states in the Middle East and North Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

July 3, 2020

There’s No Vaccine For The Sea Level Rising

We will get by the current pandemic. There will be a vaccine eventually. There will be other pandemics. Hopefully, we will be better organized next time.

Waiting in the wings are the emerging impacts of climate change, the next big challenge. There will be no vaccine to stem sea level rise. We will first lose Miami (highest elevation of 24 feet), London (36 feet), Barcelona (39 feet) and New Orleans (43 feet). Paris and New York City will disappear a bit later.

There are estimates that the cost of saving every threatened global city may be $14 trillion per year. The US portion of this number will represent a significant portion of the federal budget all devoted to one problem for many years. This may seem outlandish, but consider the nature of the threat.

If the ice cap in Antarctica totally melts, sea levels will rise 300 feet. I was surprised at this number, but I did the calculations from scratch and got the same results. Assuming this worst-case scenario, a 350-foot seawall around Manhattan, at current construction costs, would cost $25 trillion. Of roughly 50,000 buildings in Manhattan, over 500 skyscrapers would still be visible above the seawall.

Of course, the rest of New York City and Long Island would be deeply under water. Many inland cities (e.g., Atlanta, Burlington, and Columbus in the US, and Birmingham and Newcastle in the UK) might then have beachfronts.

Sea level rise is just one of the major impacts of climate change. Consider the overall causal chain:

Burning of fossil fuels increases CO2Deforestation increases CO2 in atmosphereGreenhouse warming increasesEarth’s temperature risesIce melting and sea level riseSalinization of groundwater and estuariesDecrease in freshwater availabilityOcean acidification affects sea lifeFood supply and health sufferIn the end, we are drowned, starved and/or diseased. This is a challenge we should address sooner rather than later, although we are already a bit late.

We need an integrated approach to managing failures. This begins with failure prevention, e.g., building houses on elevated foundations or stockpiling personal protective equipment. But, it is impossible to prevent all failures, particularly those that you never imagined could happen. Managing failures involves detecting, diagnosing, and fixing problems.

These tasks can be integrated within a framework that involves predicting future challenges Organizations such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Prevention, and Control, and the Federal Reserve make such predictions regularly. Though often what occurs is different from what these organizations predicted.

When measured states differ significantly from predicted states, one then diagnoses these differences. Has something happened or are the models underlying the predictions in error? The first priority is to compensate for the consequences of these problems, e.g., dispatching teams to rescue flood victims. Focus then shifts to remediating the causes of these problems – eliminating causes and/or fixing predictive models.

In order to make this happen it’s important to get support from stakeholders: including populations, industries, and governments. Gaining these stakeholders’ support for decisions to address climate change will depend upon the credibility of the predictions of behavior, at all levels in the system. Central to this support is the extent to which stakeholders interpret and pay attention to official predictions.

We cannot wait for the consequences of climate change to happen and then fix them– remember, there will be no vaccine for sea level rise. How will we afford to address this daunting future? Where will the money come from?

The answer is that we have to view climate change as an enormous economic opportunity. There is a wide range of possibilities for technological innovation, business creation, and millions of well-paying jobs. We should consider this to be the next Age of Exploration. It has already started. The difference between the current situation and the 15th-17th centuries is that we now need to explore in an integrated and coordinated manner. We must address climate change for everybody.

Featured image by Daniel Sorm on Unsplash.

The post There’s No Vaccine For The Sea Level Rising appeared first on OUPblog.

There’s no vaccine for the sea level rising

We will get by the current pandemic. There will be a vaccine eventually. There will be other pandemics. Hopefully, we will be better organized next time.

Waiting in the wings are the emerging impacts of climate change, the next big challenge. There will be no vaccine to stem sea level rise. We will first lose Miami (highest elevation of 24 feet), London (36 feet), Barcelona (39 feet) and New Orleans (43 feet). Paris and New York City will disappear a bit later.

There are estimates that the cost of saving every threatened global city may be $14 trillion per year. The US portion of this number will represent a significant portion of the federal budget all devoted to one problem for many years. This may seem outlandish, but consider the nature of the threat.

If the ice cap in Antarctica totally melts, sea levels will rise 300 feet. I was surprised at this number, but I did the calculations from scratch and got the same results. Assuming this worst-case scenario, a 350-foot seawall around Manhattan, at current construction costs, would cost $25 trillion. Of roughly 50,000 buildings in Manhattan, over 500 skyscrapers would still be visible above the seawall.

Of course, the rest of New York City and Long Island would be deeply under water. Many inland cities (e.g., Atlanta, Burlington, and Columbus in the US, and Birmingham and Newcastle in the UK) might then have beachfronts.

Sea level rise is just one of the major impacts of climate change. Consider the overall causal chain:

Burning of fossil fuels increases CO2Deforestation increases CO2 in atmosphereGreenhouse warming increasesEarth’s temperature risesIce melting and sea level riseSalinization of groundwater and estuariesDecrease in freshwater availabilityOcean acidification affects sea lifeFood supply and health sufferIn the end, we are drowned, starved and/or diseased. This is a challenge we should address sooner rather than later, although we are already a bit late.

We need an integrated approach to managing failures. This begins with failure prevention, e.g., building houses on elevated foundations or stockpiling personal protective equipment. But, it is impossible to prevent all failures, particularly those that you never imagined could happen. Managing failures involves detecting, diagnosing, and fixing problems.

These tasks can be integrated within a framework that involves predicting future challenges Organizations such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Prevention, and Control, and the Federal Reserve make such predictions regularly. Though often what occurs is different from what these organizations predicted.

When measured states differ significantly from predicted states, one then diagnoses these differences. Has something happened or are the models underlying the predictions in error? The first priority is to compensate for the consequences of these problems, e.g., dispatching teams to rescue flood victims. Focus then shifts to remediating the causes of these problems – eliminating causes and/or fixing predictive models.

In order to make this happen it’s important to get support from stakeholders: including populations, industries, and governments. Gaining these stakeholders’ support for decisions to address climate change will depend upon the credibility of the predictions of behavior, at all levels in the system. Central to this support is the extent to which stakeholders interpret and pay attention to official predictions.

We cannot wait for the consequences of climate change to happen and then fix them– remember, there will be no vaccine for sea level rise. How will we afford to address this daunting future? Where will the money come from?

The answer is that we have to view climate change as an enormous economic opportunity. There is a wide range of possibilities for technological innovation, business creation, and millions of well-paying jobs. We should consider this to be the next Age of Exploration. It has already started. The difference between the current situation and the 15th-17th centuries is that we now need to explore in an integrated and coordinated manner. We must address climate change for everybody.

Featured image by Daniel Sorm on Unsplash

The post There’s no vaccine for the sea level rising appeared first on OUPblog.

Why victims can sometimes inherit from their abusers- even if they kill them

It is a basic rule of English law that a person who kills someone should not inherit from their victim. The justification behind the rule, known as the forfeiture rule, is that a person should not benefit from their crimes and therefore forfeits entitlement. Many other jurisdictions have the same basic rule for fundamental reasons of public policy, including the need to avoid incentivising homicide. Importantly, however, Parliament passed the Forfeiture Act 1982 to give courts in England and Wales discretion to modify the application of the rule in certain cases, so that some people could inherit from those they had killed after all. Such modification is also possible in some other jurisdictions: It allows judges to consider individual circumstances where the blanket application of a forfeiture rule would cause injustice.

Sally Challen was convicted of murdering her husband in 2011. Challen killed her husband Richard with a hammer while suffering from a psychiatric illness apparently caused by his abuse. If that conviction had stood, she could not have benefitted under the intestacy rules applicable where a deceased person leaves no will, as she usually would as a spouse. The forfeiture rule would have applied unmodified because the Forfeiture Act prevents modification where someone “stands convicted of murder.” But the Court of Appeal overturned her conviction in 2019 because of psychiatric evidence suggesting she had been suffering from previously undiagnosed personality disorders at the time of the killing. Her guilty plea to the less serious offence of manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility was later accepted.

Because of the original application of the forfeiture rule, Mrs. Challen’s sons had inherited their father’s estate instead of her. Challen did not want to recover the property from them for herself. But in recent court proceedings (Challen v Challen), she did seek modification of the rule to allow her sons to recover the inheritance tax paid because their inheritance had come directly from their father rather than via her.

In exercising his discretion to modify the rule the judge took into account factors including the deceased’s violent, humiliating and isolating conduct toward his wife. The judge was also satisfied that the claimant loved the deceased very much, despite killing him. The judge emphasised that the facts occurred over 40 years and “involved the combination of a submissive personality on whom coercive control worked, a man prepared to use that coercive control, a lack of friends or other sources of assistance, an enormous dependency upon him by the claimant, and significant psychiatric illness.”

A particularly important aspect of the case was that Challen’s husband “undoubtedly contributed significantly to the circumstances in which he died,” since the judge was satisfied that “without his appalling behaviour over so many years, the claimant would not have killed him.”

Clearly, the judge responded very sensitively and carefully to the facts. He anxiously emphasised that his decision did not mean that all victims of coercive control who kill the perpetrators can expect a total disapplication of the forfeiture rule. The judge asserted that “the facts of this terrible case are so extraordinary, with such a fatal combination of conditions and events, that [he] would not expect them easily to be replicated in any other.” The expectation of relief may nevertheless be difficult to rein in in future cases.

Some may consider it controversial that the forfeiture rule can be modified at all in a case like this. But the acceptance of her plea inherently demonstrates that Challen’s culpability was limited, and that was for reasons associated with the deceased’s own conduct. The very point of the 1982 Act is to relieve the effects of forfeiture notwithstanding the fact that the deceased was unlawfully killed by the offender: If Challen had not been criminally responsible for her husband’s death, the rule would never have applied in the first place. It is also worth emphasising that Sally Challen did not inherit in substance, and her motivation in improving her sons’ position was largely selfless.

While the result appears correct, sadly the case of Sally Challen will not be the last occasion on which the phenomenon of coercive control and its consequences will come before the courts, however much the judge emphasised the extraordinary facts.

Feature Image Credit: by Mondschwinge via Pixabay.

The post Why victims can sometimes inherit from their abusers- even if they kill them appeared first on OUPblog.

July 2, 2020

Why big protests aren’t a good measure of popular power

The recent wave of protests of the Black Lives Matters movement in the United States and around the world has opened up a space of political possibility for proposals, like disbanding abusive police departments, which seemed radical and utopian only weeks earlier. In the broad sweep of history, a similar process has been seen time and time again: Significant political change often only arises in the wake of mass protest and popular civic resistance.

Surely mass protest is the fundamental expression of popular power? The bigger and more vibrant the protest, the more popular power there is? By contrast, when the society quietly chugs along, the greasy wheels of political and institutional processes smoothly turning without disruption, surely this shows a deficiency or an absence of popular power?

This view of popular power–let’s call it the insurgent view–may be appealing on face value, but it contains a paradox. On the insurgent view, a basically oligarchic regime which is convulsed by protest counts as expressing popular power more authentically than a fair and equal regime which has mechanisms in place to deal with grievances before they reach boiling point. The insurgent view has often been traced back to the work of 17th-century philosopher Benedict de Spinoza: if we turn to the philosophy of Spinoza, we can fine-tune our understanding of popular power to escape this paradox.

Some elements of the insurgent view find genuine support in Spinoza’s writings. More than any other figure in the history of political thought, Spinoza takes popular rebellion as the central political phenomenon needing to be understood. He himself witnessed many such disturbances, both in his native Dutch Republic, and as a keen observer of events in other countries. The novelty of Spinoza’s approach is his striking lack of interest in parsing whether rebellions are justified or not, and equal lack of interest in making distinctions between permissible and impermissible tactics. Such questions are, in Spinoza’s view, useless moralism, gratifying to philosophers who like to criticise everyone else, but a distraction from the political phenomenon to hand. When the people rise up, this makes manifest to us, in stark terms, the reliance of any political order on the power of the people. When the people rise up, it stands as a warning to rulers who would oppress the masses. Ultimately, the power of the people may come back to bite them.

Certainly, the insurgent view has some basis in Spinoza’s philosophy. But at the same time it misrepresents critical elements of Spinoza’s thought. I think that Spinoza’s divergences from the insurgent view have lessons for us today.

To see this, let’s focus on that most slippery of concepts, power. On the contemporary insurgent view, popular power is a perennial underlying potential of the people as a collection of equal individuals. From time to time, it bursts through the opaque and complex workings of modern political systems to express itself, calling politics back to the common good and away from sectional interests. The degree of the power of the people is proved by these moments of insurgent expression.

So power supposedly lies in momentous acts? I think Spinoza would disagree. For Spinoza, if we want to talk about an entity’s power, we need to consider overall array of effects the entity characteristically and durably brings about. Occasional acts, no matter how spectacular, are likely to be a poor guide to this more quotidian question of efficacy.

Spinoza most famously applies his analysis of power to ethics. Imagine a person who stands up for their convictions only on one occasion. The rest of the time, they are fearful and compliant. Should we say that they have the power to defend their convictions–they simply don’t often choose to exercise this power? For Spinoza, this is a wrongheaded approach. People do not straightforwardly choose to be fearful. Rather, fear is generated by certain identifiable material and psychological pressures. Insofar as the person does not regularly overcome their fears, this demonstrates that they lack sufficient power to counter the pressures that they face. Only a person who reliably acts with integrity and stands for their convictions can be said act from their own power.

The same point can be applied to groups. On the Spinozist analysis, the measure of a group’s power lies in how durably they generate the political outcomes that they desire. The people of a society do not only exist at the time of protest and revolt; they also continue to exist during more routine times. If the people only bring about their desired egalitarian political effects at those occasional moments of protest, at other times helplessly watching as their hard-fought wins backslide or are eroded, then that shows a deficiency to their power.

The Black Lives Matter protests are a momentous historical event. However, to return to our initial paradox, it is perverse to insist that popular mobilisation against an oligarchic regime is evidence of great popular power, unless and until it is translated into durable systematic outcomes. The protests in the United States occur against the backdrop of a profound and persistent failure to advance the common good, most strikingly along racial but also economic lines. On Spinozist analysis, this amounts to a profound deficiency of US popular power. We can hope that the protests contribute to strengthening of popular power, but the proof of that will lie in whether the new everyday function of US society durably advances the common good, even when the energy of revolt has dissipated.

What does popular power look like? Not momentous acts, but political and institutional processes that durably and systematically uphold equality and justice.

Image credit: Photo by Alex Radelich on Unsplash.

The post Why big protests aren’t a good measure of popular power appeared first on OUPblog.

Public health and Georges Canguilhem’s philosophy of medicine

Born in Castelnaudary in France 4 June 1904, Georges Canguilhem was a highly influential 20th century French philosopher of medicine. He took particular interest in the evolution of medical philosophy, the philosophy of science, epistemology, and biological philosophy.

After serving in the military for a short period he taught in secondary schools, before becoming editor for Libres Propos, a radical journal. He was a pacifist and in 1927 deliberately dropped a rifle onto his examiner during officer training.

In 1936 he began studying medicine in Toulouse. He took up a post at the University of Strasbourg in 1941. In 1943 he received his medical doctorate after completing his doctoral dissertation, The Normal and the Pathological. In the same year the Gestapo invaded the University of Strasbourg, injuring and killing several students and professors. Canguilhem managed to escape. After this he joined the French Resistance. He was awarded the Military Cross and the Médaille de la Résistance. He also wrote pieces of writing that criticised the fascist dictatorships in Italy and Germany.

His most well know piece of writing, On the Normal and the Pathological (1966), was an incredibly valuable contribution to the history of science in the 20th century. Contemplating the more significant change in perceptions of biology as an established, respectable subject in the late 19th century, Canguilhem explored the way that health and disease were considered and defined. It explored how epistemology, biology, and science combined with philosophy.

Canguilhem was also one of the earliest medical philosophers to use the term autopoietic in medical biology. Autopoiesis refers to the organised state of organic activity. Essentially, a living system continues to reshape itself, thereby distinguishing it from its environment. This helped in how health and disease were considered and even treated in both medical science and medical philosophy.

Canguilhem’s medical philosophy has contributed greatly to the advancement of public health and science. Canguilhem emphasised conceptual medicine, as he believed it opened the possibility to explaining facts and form theories with a practical value. The notion that a particular infectious pathogen causes a particular disease could lead to a particular scientific programme to treat the disease. That would prevent that specific pathogen transmitting to its host and making him ill. This demonstrated Canguilhem’s belief in the link between observing the history of medical knowledge and development of new medical concepts in order to progress medical science.

He lived a long life advancing medical philosophy and public health. He died in 1995, when he was 91.

Featured Image Credit: via qimono Pixabay

The post Public health and Georges Canguilhem’s philosophy of medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

July 1, 2020

Cut and dried

A less common synonym of the idiom cut and dried is cut and dry, and it would have served my purpose better, because this essay is about the verb cut, and two weeks later the adjective dry will be the subject of a post. But let us stay with the better-known variant.

Most dictionaries state that the origin of cut is unknown. As usual, this statement should be taken with a grain of salt. Unknown usually means that no convincing etymology exists, rather than that nothing at all has been said about a problematic word. And the word cut is indeed problematic. It turned up in texts only in Middle English and successfully ousted or crowded out the much older and widely used verbs of roughly the same meaning: snīþan (compare German schneiden, because Engl. snithe is obsolete; the adjective snide is of course related), ceorfan (Modern Engl. carve), and sceran (as seen in Modern Engl. share). This is a common scenario in word history: upstarts appear from seemingly nowhere and displace “respectable” old-timers—an instructive analog of human history, with the plebs destroying the old nobility or reducing it to the state of a disenfranchised group.

Attempts to find the ancient (respectable) relatives of cut have been made, and I’ll mention them, but they will hardly dispel the obscurity in which the history of this verb is enveloped. The fist thing we learn about cut is the absence of its cognates anywhere in Germanic. Similar words exist in Celtic: Welsh cwtau “to shorten,” Gaelic Irish cut “a tail,” and a few others. For a long time, it was believed that Engl. cut was a borrowing from Celtic. But the Celtic stock also lacks pedigree, so that, even if we conclude that English words were taken over from Irish or Welsh, we won’t learn too much. The great English scholar Henry Sweet believed in the Celtic origin of cut, but he was probably mistaken. After all, the English verb is rather old (its earliest attestation goes back to the thirteenth century). At present, most historical linguists prefer to derive the Celtic words from English. The “ultimate truth” will probably never be known, but, wherever it lies, the origin of cut remains a mystery. In this context, it may be useful to note that three periods are discernible in the history of English etymology with regard to Celtic: for quite some time, Celtic fantasies (Celtomania) reigned supreme (hundreds of words were traced to Irish or Welsh), then the proverbial pendulum swung in the opposite direction, and at present, fortunately, every word is analyzed individually, without recourse to nationalistic fervor.

Cut and dried. Photo by Valeria Boltneva from Pexels. Public domain.

Cut and dried. Photo by Valeria Boltneva from Pexels. Public domain.Although bereft of cognates, cut has some Scandinavian look-alikes. One of them is Icelandic kjöt, with its doublet kvett, “meat.” Last week (June 24, 2020), while discussing the origin of the word knife, in anticipation of this discussion, we posted a huge picture of a knife among many pieces of meat. Can cut have anything to do with the Scandinavian word? In the north, it is not isolated: Norwegian kjøt, Swedish kött, and Danish kød are reflexes (continuations) of the same Old Norse noun, which once must have sounded approximately like ketwa-. The connection is unlikely: no Scandinavian word sounds like cut, and only ket “carrion” has been attested in English dialects, obviously a borrowing from the North.

Modern Icelandic kúti “little knife” surfaced in the language only in the seventeenth century and must have been borrowed from French couteau “knife.” Along with kúti, the verb kúta (“to cut”) exists, which is also almost modern, and, though it has sometimes been looked upon as the source of Engl. cut, it is too recent to explain the origin of the Middle English verb. To use James A. H. Murray’s favorite phrase, this reconstruction “is at odds with chronology.”

The French words exist, as though to tease us and invite implausible comparisons. Couteau goes back to Latin cultellus, a diminutive form of culter “knife, plowshare,” known to English speakers from co(u)lter. The Latin word must have meant something like “striker.” Cutlass, from French coutelas, is related to co(u)lter, but cutlet is not! Cutlet returns us to French couteau, French côtelette, from Old French costelette, diminutive of costa “rib.” Engl. cute is a prefix-less variant of acute, from Latin acūtus, the past particle of acuere “to sharpen” (Engl. acid, acme, acumen, and a few other words have the same root). Even Engl. cutter “vessel” is not necessarily from cut + er! This short list shows how careful one should be in stringing together seemingly related forms.

There have been attempts to connect Engl. cut with Icelandic kjá “to rub.” The idea inspiring such attempts is that cut is an ancient, even very ancient verb, with the root going back to Indo-European geu– “to cut” with an “extension” (a kind of suffix, in this case –t). Massimo Poetto, a specialist in the Indo-European antiquities, cited the cuneiform word –kudur “part of a sacrificial animal,” which he compared with the Scandinavian words cited above. Armenian ktrel also means “to cut.” But there’s “the rub”: nothing testifies to the antiquity of the English verb. Numerous colloquial words were coined late. Likewise, slang thrives nowadays without any ties to the venerable past.

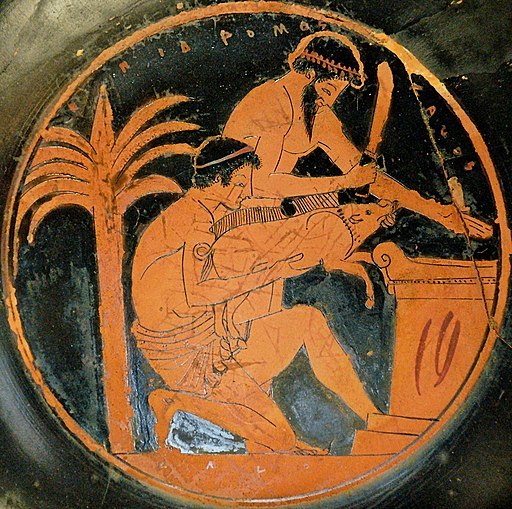

A sacrificial animal. Hardly an inspiration for the English verb cut. Image courtesy of the Louvre Museum via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

A sacrificial animal. Hardly an inspiration for the English verb cut. Image courtesy of the Louvre Museum via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.The OED presents an excellent picture of the history of cut, and so does The Century Dictionary, but The Century Dictionary also says in passing that cut took “the place as a more exact term of the more general words having this sense (carve, hew, slay, snithe); imitative.” It is hard to decide how “exact” the new verb was. I have quoted the passage for the sake of the word imitative. Every now and then, we run into monosyllabic verbs like dig and cut and have the impression that they were coined to reflect, with verbal means, the strenuous effort associated with the actions described. To be sure, the reference to an effort does not explain why just dig or cut, rather than, for instance, tig or gut (the choice of the sounds must have been, to a certain extent, arbitrary), but it frees us from the fruitless efforts to look for Indo-European roots where they probably never existed.

The combinations must have been justified at the psychological level, because they tend to recur in various languages. Such are Engl. butt, kick, hit, hitch, hack, chap ~ chop, and so forth, which are sometimes grudgingly labeled in dictionaries as sound-symbolic or imitative. We can compare cut and put. At one time, those verbs rhymed, as they still do in northern British dialects. The so-called ultimate origin of put is said to be unknown, and again Celtic analogs turn up, to be dismissed as borrowings from English. What is “ultimate origin”? Some Indo-European root? Is that the wild goose we are chasing?

Wild goose chase: an inspiring, if not always a profitable, occupation. Goose chase by Brendan Lally. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Wild goose chase: an inspiring, if not always a profitable, occupation. Goose chase by Brendan Lally. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.We may never find out how put and cut came into being, but, if agree that we are dealing with medieval slang or perhaps with medieval expressive, emphatic, not necessarily imitative, verbs belonging to more or less the same emotional sphere, we’ll probably be on the right track and will allow the Hittites, Sumerians, French, Dutch, and everybody else in the wide world to coin similar words under similar circumstances, according to the model Wilhelm Oehl, often referred to in this blog, called primitive creation (in German elementare Wortschöpfung).

Feature image credit: photo by Helmut Jungclaus. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Cut and dried appeared first on OUPblog.

The history of Canada Day

Because they raise difficult questions about who we are and who we want to be, national holidays are contested. Can a single day ever contain the diversity and the contradictions inherent in a nation? Is there even a “we” and an “us”?

Canada Day is no exception. Celebrated on 1 July, it marks the anniversary of Confederation in 1867. For the longest time the holiday was known as Dominion Day, an occasion for cities and towns across the country to host picnics and excursions where people played games and local notables delivered earnest speeches. They touted Canada’s natural wealth and extolled the virtues of the British Empire, referring to Canada as the eldest daughter of the Empire and as the gem in the Crown. At the 1891 Dominion Day celebrations in Toronto, children waved maple leaves and sang “Rule Britannia.”

Despite the effort to fashion a “we,” there was never an “us.” After all, Quebec didn’t share English Canada’s enthusiasm for the Empire, making its Dominion Day celebrations more muted. Its national holiday was – and still is – 24 June, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Meanwhile, in the interwar years, the Chinese community in British Columbia turned Dominion Day into Chinese Humiliation Day to highlight racist laws that restricted Chinese immigration to Canada and denied Chinese Canadians the right to vote.

After the Second World War, as the Empire ended and as Canada redefined itself along bilingual and multicultural lines, “dominion” took on new meanings. Against the backdrop of Quebec separatism and the assertion by Canadians who were neither French nor British that they too deserved a seat at the table, it now connoted Canada’s colonial status.

Nonsense, said a handful of historians. Dominion was a very Canadian word, referring to the Dominion of Canada. Inspired by Psalm 72 – “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea” – and carefully chosen by the Fathers of Confederation, it was a new title, unlike, say, Kingdom, a much older title. But as Lord Carnarvon explained to Queen Victoria, it conferred “dignity.”

Dignified or not, dominion was slowly erased from official nomenclature by successive governments. When the Dominion Bureau of Statistics was renamed Statistics Canada in 1971, one historian wondered if the government intended to remove dominion from the phone book. Ten years later, his suspicion was confirmed when the government of Pierre Trudeau re-named Canada’s national holiday.

The debate – in hindsight, a foregone conclusion – pitted old nationalists against new nationalists, or Red Ensign nationalists who emphasized Canada’s Britishness against Maple Leaf nationalists seeking to accommodate Canada’s bilingual and multicultural realities. Familiar arguments were rehashed. To its proponents, dominion had a rich history, while its Biblical origins were a statement of God’s omnipotence and a reminder of Canada’s status as a Christian country. But to its opponents, it had run its course. To quote one cabinet minister, “Canadians see themselves not as citizens of a Dominion – with its suggestion of control, dominance, and colonialism – but as citizens of a proud and independent nation.” Besides, he said, dominion can’t be easily translated into French. And with that, Parliament amended the Holidays Act in July 1982 to rename Dominion Day as Canada Day.

Like the statues coming down and the buildings being renamed, Dominion Day never stood a chance: although it could draw on the past, it couldn’t point to the future. Canada Day, however, was capacious, meaning different things to different people: freedom, tolerance, equality, diversity, and security. As one member of Parliament explained, “We are all minority groups. Canada is a nation of minorities.”

He was right, of course. But thinking about Canada Day in this moment of renewed focus on race and racism – when countless voices insist that Black Lives Matter and Indigenous Lives Matter, when interactions between police and black people and indigenous people can go horribly wrong, and when politicians struggle to find the right note – I am reminded that “we” and “us” are elusive, if not impossible, and that some Canadians are more minority than other Canadians.

Featured Image Credit: ElasticComputeFarm

The post The history of Canada Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers