Oxford University Press's Blog, page 141

July 10, 2020

Social needs are a human right

In April 2020, an ER physician in Toronto, Ari Greenwald, started an online petition to bring tablets and phones to his patients in hospital, because hospitals had imposed strict No Visitor rules to limit the spread of COVID-19. Greenwald said that, “As challenging as this COVID-era of healthcare is for us all, the hardest part of patient care these days is watching patients suffer alone without family and friends at their bedside.”

No visitor rules do more than deny patients access to family members’ hugs and companionship. They also deny those families a chance to care for their loved one while they’re in the hospital. Family members can’t hold their hand while they are dying or say good-bye in person and ease their own grief by knowing that they supported their loved one at the end. In lucky cases where the patient has a device in hospital, families get to say good-bye in some fashion online. But, many other families learn through a phone call from a healthcare worker that their loved one has died, without them.

No visitor rules, social distancing, self-isolation, and quarantine are agonizing for us because we are deeply social creatures. Our social needs may even be more important than our needs for food, water, and shelter. Social needs are a human right.

We are so deeply social that meeting our social needs – for decent human contact, acceptance within a community, companionship, loving relations, and interdependent care – is more important than meeting almost every other need we have. The exceptions are our basic need to survive – which the social-distancing orders prioritize – and our need for clean, breathable air. (Hold your nose and close your mouth for two minutes to see if you disagree with how fundamental that need is.)

The thought that our social needs are more important than our needs for food, water, shelter, health, education, free movement, free expression, due process, and the rest, is a revisionary one gaining traction amongst social psychologists, neuroscientists, and some philosophers, which implies that Abraham Maslow’s famous pyramid of the hierarchy of needs is incorrectly ordered.

Maslow put on the bottom, most basic level of his pyramid our physiological needs for food, water, and sleep, and then, on the second level, our safety needs for physical shelter, bodily security, and health. He called these our basic needs. Above them come our so-called psychological needs which include, on the third level, our needs for belonging, intimate relations, friendships, and love, and, on the fourth level, our needs for esteem and a sense of accomplishment. Finally, at the top of this five-level pyramid, sit our needs for self-actualization to realise our full potential in creative endeavour.

There are several reasons why Maslow’s ranking of needs is mis-ordered and our social needs really sit on the bottom, most basic level.

Humans necessarily depend on each other to access the goods that Maslow took to be most basic. We cannot securely access food, water, a safe place to rest, health care, or bodily security without other people’s continued support. This is true most obviously when we’re babies and children.

But it is not only in childhood that we depend on each other to meet our needs. Throughout our lives, we face innumerable challenges that we cannot weather well without help, including giving birth, surviving illness, recovering from injury, facing death, grieving, withstanding loss of employment, returning from prison or exile, acquiring education, expressing ourselves, and cultivating spirituality and faith.

But our social needs are also important in their own right. Even when we’re healthy, able adults, we are defined by our sociality. Our brains are hardwired to think about social connections when we don’t task them to think of other things: this is our default neural network. And, we typically choose to spend much of the time that we’re awake with other people.

A sceptic might note that (some) people can thrive perfectly well without human contact. There are some real-life Robinson Crusoes after all, such as Richard Proenneke, a former military carpenter, mechanic and self-taught naturalist, who lived alone at Twin Lakes, Alaska, for close to 30 years.

But, Robinson Crusoes are the exceptional ones, and their ability to survive or thrive in isolation does not change the fact that most of us need persistent, supportive social contact and care.

If our social needs are so fundamental, basic, and universal, they lead us necessarily into the territory of human rights. Human rights protect the brute moral minimum, i.e. the least that we owe each other as human beings. We must have, at the very least, a human right against social deprivation, or rather a right to have access to decent human contact, to try to form and keep good social connections, to be protected in our connections once they exist, to be put into supportive connections when we’re unable to make social overtures, and to have the social resources we need to sustain the people we care about.

Social deprivation doesn’t occur just in institutions of forced segregation like solitary confinement, isolated immigration detention, or quarantine. We can also be socially deprived when we’re surrounded by people who treat us brutally. This is the reality in many prisons where violence, sexual assaults, harassment, and intimidation define inmates’ lives.

Heartbreakingly, home can also be sites of social deprivation when it’s defined by abuse. The spike in domestic abuse reports in many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic is evidence of a tragedy that governments anticipated when they closed the schools. Many people – including many children – are leading socially deprived lives.

Despite the social horrors that many people are suffering, the time of the pandemic is also witness to a remarkable outpouring of social overtures and social contributions. News stories highlight the famous hotel that made its secret cookie recipe public, and the children’s artists who are offering free lessons online. There are the shoe companies and spectacles companies providing free goods to healthcare workers, and the restaurants that are running soup kitchens (delivered to people’s houses). There are the families sharing supplies and shopping for each other, the theatres posting concerts, plays, and musicals free online, and the audiobooks seller making the children’s section freely available while schools are closed. There are the people in lockdown lowering baskets of bread from their apartment balconies for the homeless people below, as well as the actors and sports stars who are using their fame to get more personal protective equipment to healthcare workers. Wealthy people are making substantial donations; hotels are offering rooms free of charge to commute-exhausted healthcare workers and newly arrived immigrants; and thousands of willing volunteers want to help. There are the evening cheers for healthcare workers heard around the world and the countries donating PPE to other countries that are in greater need.

The full effects of this season of social chaos are yet to be seen. We have made a necessary choice to prioritize human life and health over sociality. But, we are paying a high price for it – an often invisibly high price – which we must not ignore. We are fundamentally social beings. Tablets in hospitals, face-to-face conversations, and hugs are as vital as food and water for our survival and wellbeing.

Featured Image Credit: by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

The post Social needs are a human right appeared first on OUPblog.

Five tips for clear writing

Blaise Pascal, the seventeenth century mathematician and philosopher, once apologised for the length of a letter, saying that he had not had time to write a shorter one.

All of us face situations where we need to compress much information into little space. Perhaps we have to fill in an online form with a character limit or write a cover letter for a job application which sells our key skills and life experience in just a page or two. Or perhaps we are writing a mass email to colleagues which we want to stand a chance of actually being read. Yet many people fall prey to verbosity. They pile up facts rather than deploying them as weapons; their best thoughts are buried under the weight of futile phrases. One reads what they have written with a single thought hammering repeatedly in one’s head: Why are you telling me this?

But there is no need to fall into the trap of wasted words. Here are my tips for how to achieve verbal economy, whether you’re writing a PhD thesis or a text message to a friend.

Be authoritative. Tell your readers what they need to know, not what you might ideally like them to know. Tell them also what they need to think about it.Save your readers time. If you are summarising a file of documents for them, you do not need to give them the experience of reading it themselves. Don’t use a piece of writing as a dumping ground for evidence; use the evidence sparingly to illustrate your argument.Pick your battles. You may need to prove some points laboriously, especially if the ground is controversial. But you can’t do this across the board. Work out where a blow-by-blow account is necessary and where a simple allusion will suffice.Don’t include details just because they are fun or interesting. If they don’t serve your argument or your story, they should go.Observe the 5% rule. Any text, whether it’s a 1,000-page novel or a tweet, can be reduced by 5% without serious sacrifice of meaning. In fact, the true percentage is probably higher …The over-arching theme of my advice is prioritisation, in the service of the readers. Put yourself in their place – understand their needs, and don’t waste their time. And here’s a final tip: when you have run out of things to say, stop writing.

Feature image: Minimal pencils on yellow by Joanna Kosinska via Unsplash .

The post Five tips for clear writing appeared first on OUPblog.

July 9, 2020

How education could reduce corruption

We live in an era of widely publicized bad behavior. It’s not clear if there’s more unethical behavior occurring now than in the past, but communications technology allows every corrupt example to be broadcast globally. Why are we not making better progress against unethical conduct and corruption in general?

Morals are the principles of good conduct, widely accepted by all. The study of morality is ethics, and unethical conduct, which underlies all corruption. Corruption undermines the rule of law, creates economic harm, violates human rights, and illicitly protects facilitators and accomplices. Both unethical and corrupt conduct are selfish or self-seeking behavior without regard for the valid claims or human rights of others.

Where do ethics come from? We learn them in the same way we learn all skills, including foreign languages, mechanics, or research methods. People often overestimate the ethicality of their own behavior, failing to recognize underlying, self-serving biases that promote misconduct. We see ourselves as rational, ethical, competent and objective, but lack the ability to see our ethical blind spots that conceal conflicts of interest and unconscious biases in decision-making. Ethical training, education, and reinforcement results in better conduct.

But learning and application of principles in practice is an incremental process, moving from smaller acts to more consistent courses of conduct. Ethics might be the most important skill of all, because it provides the path to appreciate that there is a greater purpose in life than self-interest. People are moral agents, have moral responsibilities, but many have never learned the principles for ethical decision-making.

Global interest in ethical conduct has grown dramatically during the last generation. During the 1990s, the World Bank changed course to address the “cancer of corruption.” This launched the World Bank into a new era in which addressing corruption to ensure funds were not misspent became as important as the development work itself.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1948, which now has 36 member countries, representing nearly two-thirds of gross domestic product globally. Concerned about the tax deductibility of bribes in many countries, the organization developed a convention to criminalize foreign bribery entirely, which entered into force in 1999. The organization is the first binding international convention criminalizing foreign bribery across many nations.

The United Nations Convention against Corruption entered into force in 2005, specifying multiple forms of corruption beyond just bribery, and providing a legal framework for criminalizing and countering it. The UN Convention against Corruption is the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument. There are now 187 state parties to the Convention, representing 97% of the UN membership.

Each of these initiatives is significant, and they require participants to enact laws and regulations, engage in enforcement actions, and obtain anti-corruption training. Unfortunately, these initiatives focus on structural reforms: laws, policies, procedures, and technical assistance, to reduce the opportunities for corrupt conduct and enforce anti-corruption provisions. Structural reforms have limitations, however. They reduce opportunities for misconduct, but do not preclude motivated actors from seeking unethical advantage. The result is better institutions, but individual decision-making remains the same.

There are signs of global movement to improve individual ethical decisions, however. The Education for Justice Initiative was developed from the 13th United Nations Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in 2015. The initiative highlights the importance of education in preventing crime and corruption, and promoting a culture that supports the rule of law.

One of the courses in the Education for Justice Initiative is integrity and ethics. Another is corruption. This effort builds on research documenting the effectiveness of creating principled, ethical decision makers from a young age. The courses, available open access globally, equip participants at different education levels with skills to apply and incorporate these principles in their life and professional decision-making.

People need to be accountable even without a camera looking over their shoulder or constant police surveillance. People must be motivated to act ethically, and establish a moral identity, that supports conduct in the interest of others, rather than selfish or self-seeking behavior.

People need to have better moral integrity is we want to promote ethical conduct. People are under continuous pressure on many fronts: business concerns, government operations, medical access, education, among others. Ethical conduct, resistant to corrupt influences, can be found in unlikely places, but it must begin with greater individual accountability that occurs with higher ethical standards developed through teaching, training, and practice.

Personal and social happiness come from actions that benefit others, rather than exploit or ignore them. People respect other people with high moral standards. There is freedom found in not yielding to our basest desires, and in living openly and cooperatively with others rather than secretively and fraudulently.

It is time to look beyond structural and institutional reforms to reduce opportunities for corrupt conduct, and enforce anti-corruption provisions. It is time to also focus on individual moral education and training to reduce the number of motivated actors seeking unethical advantage.

Featured Image Credit: Ethics-2991600_1920 by Tumisu via PixabayThe post How education could reduce corruption appeared first on OUPblog.

The scientific mysteries that led to Einstein’s E=mc^2 equation

Scientists deal with mysteries. As Richard Feynman once commented: “Science must remain a continual dialog between skeptical inquiry and a sense of inexplicable mystery”.

Three examples: it is profoundly mysterious as to why mathematics can so accurately describe our physical world, and even predict events, such as the motion of the planets or the propagation of radio waves from earth to spacecraft. The theorems of mathematics are not normally thought to derive from properties of the real world (some philosophers think they do), but are more like a very elaborate game of chess. Secondly, it is entirely mysterious that light and radio waves can travel through outer space, where there is nothing to support them. Yet here mathematical metaphors (called Maxwell’s equations) work well. James Clerk Maxwell derived his equations from a mechanical model of a mysterious ghostly invisible vortex foam they called “the aether”, which was supposed to be at absolute rest, filling the entire universe. A final mysterious and unexpected connection – attempts to locate this stationary aether led most improbably to Albert Einstein’s equation relating mass and energy, the basis for nuclear power.

The light reaching us from distant stars is indeed transported across an empty vacuum, and takes time to get here, so that when we look up at the stars we are looking back in time. Yet this idea, that light travels at a finite speed was resisted until quite recently. It took root only with the first approximate measurement of its speed by Ole Roemer in 1677, in one of the greatest experiments in the history of science. He did so use Galileo’s telescope to observe the moons of Jupiter. Galileo had suggested using the moon Io as a clock, as it eclipsed behind the planet every 42.5 hours, since the eclipses were visible from anywhere on earth. In this way sailors could keep track of time back home, and so find their longitude from the time difference between noon at home, and local noon, when the sun was overhead (longitude is the distance you might fly around the equator, when jet-lag and time difference tells you how far you’ve gone). Roemer noticed that these eclipses were sometimes about ten minutes late, due to the finite speed of light. From this delay, Christopher Huygens and Isaac Newton were able to make the first reasonably accurate estimates of the speed of light, using the approximate diameter of the earth’s orbit.

In earlier times, it had been natural for philosophers to imagine that the earth was at the center of the universe, orbited by the sun (the Greek philosopher Aristarchus was perhaps the first, before Copernicus, to suggest that the earth orbits the sun). By the eighteenth century, the idea that the sun lay at the center of the universe was widely accepted, and was therefore the only thing truly “at rest”. The night sky was seen to consist of patterns of stars (called “constellations” – Orion, Big Dipper) which moved across the sky as the earth rotated about its axis. Wandering across this fixed background of distant stars at rest were the planets, distinguished by their irregular paths. But the idea of a fixed background was itself called into question when astronomers observed super-nova explosions and moving stars. Johannes Kepler, a mystic and a firm believer in astrology, had shown that the planets move in elliptical orbits in 1619, a great discovery based on Tycho Brahe’s accurate measurements. Newton used, but did not acknowledge, Kepler’s finding (and the inverse square law attributed to Robert Hooke) to develop his theory of gravitation.

Putting these ideas together – a finite speed of light and an absolute, God-given aether at rest – led to the most difficult problem of all. How can this rest-frame be identified and located, and is it the stationary frame against which the speed of light is to be measured? If so, we might expect an aether headwind (or tailwind, six months later), as the earth speeds through it around the sun at about 67,000 mph. Is this frame somehow fixed to the remote stars, or to our sun, or even, most improbably, to the earth (rotating with it)? And, like the headlights on a fast car at night, shouldn’t the speed of the light be added to the speed of the car, the light source? The first American to win the Nobel prize, Albert Michelson, tried hard to locate the aether at Case Western University using an optical interferometer he had invented, but failed, leading him to almost give up research in despair. He found that the speed of light was the same in every direction and in all seasons – no headwind! Most puzzling of all were the measurements of the speed of light in Paris by Léon Foucault and Hippolyte Fizeau, which confirmed the existence of an aether according to an earlier theory of Fresnel. And the contradictory prediction Maxwell had made that the speed of light did not depend on the speed of its source.

These were the questions which nineteenth century physicists struggled with, leading to a true crisis in physics, as pointed out by Lord Kelvin in a famous address in 1900. Albert Einstein alone was fully able to make sense of all this contradictory information in his famous 1905 paper on relativity, and later, to his famous equation E=mc^2. This was the equation, showing that mass is a form of energy, which was needed to explain the nuclear reactions which power our sun and the stars, in addition to nuclear weaponry. He did so by abolishing the aether altogether, showing that all motion was relative (clever students, leaving London around this time would ask the stationmaster “Does Oxford stop at this train?”).

In his superb history of science and the romantic poets in the early nineteenth century, Richard Holmes describes vividly that Age of Wonder. That the failure to locate the aether and any frame of absolute rest in the universe could lead to an understanding of the origin and fate of stars and of nuclear energy led surely to the beginning of a second Age of Wonder, with the birth of both relativity, and quantum mechanics, our deepest mystery.

The post The scientific mysteries that led to Einstein’s E=mc^2 equation appeared first on OUPblog.

July 8, 2020

Etymology gleanings for June 2020

Response to some comments

The verb cut. The Middle Dutch, Dutch, and Low German examples (see the post for July 1, 2020) are illuminating. Perhaps we are dealing with a coincidence, because such monosyllabic verbs are easy to coin, especially if they are in at least some way expressive. But another possibility is that in a rather large area, cut and its look-alikes had near-universal currency among cutters, diggers, and perhaps some other artisans and laborers. While researching the etymology of several words (in my experience, adz(e) and ajar: see the posts for August 22, 2012 and March 25, 2020), I suggested that they might have belonged to the lingua franca of itinerant workers. Cut looks like a proper candidate for inclusion in an international jargon of manual workers, both skilled and unskilled. The Greek synonym kottō “to cut” also confirms the idea that this short syllable is a common instinctively chosen sound complex for accompanying an effort. The Polish verb cited in the comment belongs here too.

Cut, cut, cut! Image: public domain via pxfuel.

Cut, cut, cut! Image: public domain via pxfuel.Greek kottō cannot be the source of its Germanic near-homonym, because, if the speakers of Germanic had borrowed it from Greek during the Paleolithic Period (let us say, ten thousand years ago), it would have undergone the consonant shift and become something like hoth. In general, the more a Greek and an Old Germanic word resemble each other, the smaller the chance that they are related, because in Germanic, not only consonants but also vowels would have diverged from the Indo-European protoform. The Greeks were not the first inhabitants of their archipelago. The homeland of the Germanic nomads is also unknown. In any case, the Germanic (or First) Consonant Shift is centuries later than Homer.

Before the First Consonant Shift. Image 1: public domain via pxfuel. Image 2: Bradshaw rock paintings by TimJN1. CC by-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Before the First Consonant Shift. Image 1: public domain via pxfuel. Image 2: Bradshaw rock paintings by TimJN1. CC by-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The noun sword. It cannot be related to German schwarz “black.” Schwarz is a Common Germanic noun, going back to swart-, while the protoform of sword was swerð-, so that the final consonants are not compatible. This obstacle may perhaps be overcome, but the suggestion that sword meant “burned, or black wood” looks indefensible. When were swords wooden and black? It will be remembered that, if my reconstruction is realistic, swords were called this because they were shining (see especially the post for June 17, 2020).

The verb gnash. It was mentioned in a comment on the post devoted to the origin of knife (June 24, 2020). Like initial kn-, gn– occurs in some sound-imitative words. Gnash and gnaw are among them. Old Icelandic is full of gn-verbs. Yet no direct tie exists between gnash and knife.

SLANG

(There we go) laughing and scratching. What is the origin of the phrase? Our correspondent found numerous examples of this amusing phrase, and so did I, but not a hint of its source. Perhaps some of our readers will be more fortunate. The obscurity of the phrase is especially irritating, because to laugh and scratch has passed into modern slang with the meaning “to inject a drug.”

Another correspondent wonders how specialists discover the origin of some recent words. The procedure is the same in all etymological searches: the linguist tries to find where and when the word appeared for the first time, compares the neologism with other similar coinages, and tries to make an intelligent guess. The letter contained five words. Four of them are more or less transparent: finna (a contraction, like the synonymous gonna, probably based on the verb find), simp “fool” (the root of simple ~ simpleton); titcow (the formation and meaning are easy to guess), Poggers “a Twitch Emote for Pepe the Frog,” evidently, a blend of P and (Fr)og; and doge, about which I know nothing, unless it contains an ironic reference to some big shot (doges were the chief magistrates of Genoa and Venice).

English spelling

Six alternative schemes have been offered for final debate, and the second Spelling Congress is being planned. Consult the website of THE ENGLISH SPELLING SOCIETY.

In my posts, I sometimes refer to E. Cobham Brewer, but few people may know his brief contribution to Spelling Reform (Notes and Queries, 8th Series, vol. II, 1893, pp. 363-64; available online). Some of his suggestions have become the norm in the United States. Brewer pleaded for dialog, catalog, program, and so forth (without the useless letters at the end). But his spelling cigaret, favorit, and so forth found no support, though, surprisingly, preterit, a technical term of grammar, has broken through in America. Some of his other ideas were bizarre, but such were also many of his etymologies that alternated with shrewd remarks on the origin of words and idioms. His Dictionary of Phrase and Fable enjoyed such popularity that the lack of later comments on his spelling ideas is surprising.

The beginning of serious English etymology in England

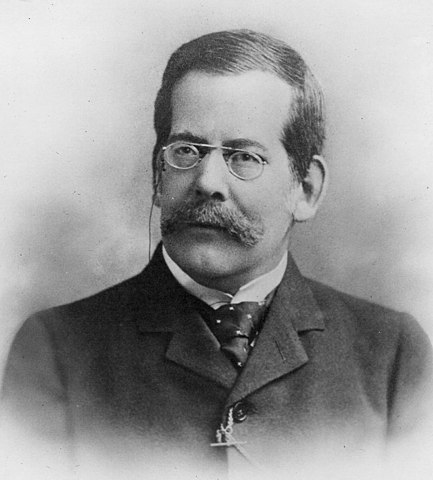

Henry Sweet (1845-1912). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Henry Sweet (1845-1912). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1879, the first fascicle of William W. Skeat’s An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language on an Historical Basis (A—DAR) came out, and Henry Sweet, at that time the best specialist in the history of English, wrote a review of it. In retrospect, such giants as Skeat and Sweet have acquired superhuman proportions in our minds, but no, they were like the rest of us. Also, Sweet was a bitter, irascible man, because he never got an academic position which he so richly deserved. This lack of official recognition always surprised his German colleagues. They even wondered whether Sweet was the man’s real name. Perhaps he was a Jew, Mr. Süß? No, he was an Englishman, every inch of him.

In Sweet’s opinion, Skeat was strong on Middle English, but his “treatment of the Old English period is the most unsatisfactory, as Prof. Skeat has here relied mainly on the extant dictionaries, all of which (with the exception of [C. W. M.] Grein) teem with the grossest errors handed down from one compiler to the other. [Edward] Lye pillaged [Franciscus] Junius, and Lye and Sommer, together with the later glossaries to various text editions, were digested into one uncritical mass by [Joseph] Bosworth, who not only retains all the blunders of his predecessors, but even adds to them.” This is followed by close to two pages of corrections and the following conclusion: “I have made these criticisms, not to depreciate Prof. Skeat’s work, but to show how vast the subject is, and what many-sided training and research its study involves. Etymology is not a pursuit to be taken up by dabblers and dilettanti, as many still assume, but is really the sum of the results on every branch of philological science” [Hear! Hear!] (and a few more placating words)—The Academy 16, 1879, 34-35.

Advanced Modern English

If your friend is coming to see you, look for them both ways. Photo by Loudon Dodd. CC by-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

If your friend is coming to see you, look for them both ways. Photo by Loudon Dodd. CC by-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.They. I know that the pronoun they referring to a single person is here to stay but cannot resist the temptation to quote a few nice samples of this usage from letters to the student newspaper of my university: “I am always struck by the feeling the writer has spent a lot of time thinking about their situation….” (Only his or her own?) “As someone who has been pro-life all their life, I believe…” [not all my but their life!]. “If your friend told you they were going to have sex with someone they knew ‘pretty well’, you’d probably tell them to be very careful.” (Agreed: group sex is dangerous.) “It’s just a process to have that individual come into the office so they can be explained their rights [and] they can understand the process better.” Isn’t there a rule that, when people begin to speak such advanced English, they can no longer hear what they are saying? “They can be explained their rights….”!

Tricky agreement. I have the impression that the agreement in the following two sentences is now the norm, but isn’t it an odd norm? “Each of the plans, which were emailed to faculty and staff earlier this month, include a combination of classes in both the disciplinary inquiries” and “Each of the plans keep current writing requirements but add two new fundamentals.” (The header to today’s post shows a crowded restaurant, hopefully, in a communist society: “From each according to his [!] abilities, to each according to his [!] needs.”)

Comments are welcome!

Feature image credit: Carnegie deli by Joakim Jardenberg. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Etymology gleanings for June 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Why Brexit could make it harder to fight money laundering

The prime minister says the United Kingdom will not extend the Brexit transition period. The UK is leaving transition on 31 December 2020, with or without a deal. London lawyers have questioned whether intelligence sharing has become a political bargaining chip in ongoing negotiations. The City of London is asking whether Brexit risks making the UK’s money laundering fight harder. If we don’t share information with our neighbours, it will be more difficult to detect and prosecute financial crime.

Intelligence sharing by law enforcement across borders is just one aspect of the immediate choice facing the UK in tackling financial crime. More fundamentally, the UK must now decide whether to follow the US approach to financial sanctions, stick with the European Union’s priorities, or go it alone.

The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 is the vehicle which the UK must use to plot its future course in sanctions and anti-money laundering.

Without the anti-money laundering act, the UK would have no mechanism for keeping pace with fast-changing events. The Brexit debate did not dwell on the implications for sanctions and anti-money laundering regimes in the UK. Nevertheless, the UK had come to depend on the EU as providing the mechanisms for imposing sanctions, and for providing the conduit for international standards in anti-money laundering to be brought into UK law.

An early clue as to how the anti-money laundering act may be used is seen in the detail of the UK’s post- Brexit sanctions against Russia. There are early signs of the UK adopting a subtly different approach from the EU in its treatment of certain Russian- owned entities. The new law includes the Magnitsky amendment, which was a late change, allowing the UK to impose sanctions on those who commit human rights violations.

Further, the prime minister was urged in January 2020 to take unilateral action against Iran in respect of the detention of Nanzanin Zaghari- Ratcliffe. This would be a departure from the EU approach. The EU has been reluctant to implement targeted financial sanctions against Iran In parallel with the Brexit transition debate, the early signs are that the UK may indeed be diverging from its EU neighbours’ approach to sanctions.

Also, in January 2020, the chancellor of the exchequer warned there would be “divergence” from the EU trade rules after Brexit. What exactly he meant was unclear, but there is a new margin of discretion for the UK to depart from the EU approach after Brexit.

Following the anti-money laundering act the UK can now take is own course in all areas of money laundering prevention and punishment.

In the first place, there is now a very wide discretion for the UK to expand its supervised population to include any “relevant business” [which] means business of a kind which entails risks relating to money laundering, terrorist financing or other threats to the integrity of the financial system. This new definition is much broader than the existing scope of UK regulations, which focused more on identifying particular types of entities or people (e.g. a bank, casino, or law firm).

The anti-money laundering act allows future regulations to require the relevant departments of the UK Government “to identify and assess risks relating to money laundering, terrorist financing or other threats to the integrity of the international financial system.” Moreover, the government will be able to, “make provision about factors to be taken into account in the assessment of such risks.” This may go far beyond the high- level approach of reports and guidelines set out so far. There is scope for the UK government to identify countries and regimes it regards as high risk, and a danger that politics may play a part in these assessments.

The UK government could use the anti-money laundering act to extend existing rules to a broader population and/ or to amend any of the current anti-money laundering regulations. This goes far beyond what was necessary to deal with the compliance consequences to the UK of Brexit. It means the UK could decide that the EU is taking too strict an approach. Such a path could hamper the global fight against financial crime. As with information sharing and financial sanctions, international co-operation is key.

Will the UK government do something else, or is it bluffing as part of Brexit transition negotiations? Either way, its use of the new anti-money laundering act will be key.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Christine Roy on Unsplash

The post Why Brexit could make it harder to fight money laundering appeared first on OUPblog.

July 7, 2020

Is motion an illusion of the senses?

According to Aristotle, Zeno of Elea (ca. 490 – ca. 430 BCE) said, “Nothing moves because what is traveling must first reach the half-way point before it reaches the end.”

One interpretation of the paradox is this. To begin a trip of a certain distance (say 1 meter), a traveler must travel the first half of it (the first 1/2 m), but before he does that he must travel half of the first half (1/4 m), and in fact half of that (1/8 m), ad infinitum. Since there will always exist a smaller first half to be traveled first, Zeno questions whether a traveler can ever even start a trip. The paradox is this: while on the one hand, Zeno’s argument, which questions the very ability to even start a trip, is logical; on the other hand, all around us we see things moving. Hence, either Zeno’s reasoning is flawed or what we see is false.

Proposed solutions have often aimed to find a flaw in Zeno’s reasoning. However, empowered by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics, we’ll argue in favor of Zeno that at best, the phenomenon of motion is experimentally unverifiable! The uncertainty principle discusses how nature limits our ability to make exact measurements regardless of how smart or patient we are or the sophistication of our experimental apparatus. A dramatic consequence of the uncertainty principle is this: observations are disconnected, discrete events; consecutive observations have time and space gaps—we can observe nature only discontinuously. Roughly speaking, it is as if we are observing nature by continuously blinking—our observations are discontinuous, dotted, intermittent, quantum! The concept of continuity in observation must be dismissed. It is a false habit of the mind created by the observations of macroscopic (daily) phenomena such as, for example, a flying arrow, for which the space and time gaps are undetectably small (due to the arrow’s relatively large mass), although not zero, giving the illusion of continuity in observation. Discontinuity in observation however cannot be ignored when trying to observe microscopic phenomena such as tiny-mass electrons. And without the ability to observe continuously, motion becomes an ambiguous phenomenon. How so?

Motion occurs when during a time interval a particle (e.g., an electron) changes positions with regard to some observer; a particle should be now here and later there in order to say that it moved. But since (according to the uncertainty principle ) nature does not allow us to keep a particle under continuous observation and follow it in a path, and also since a particle is identical to all other particles of the same family (for example, all electrons are identical), it is impossible to determine whether, say, an electron observed in one position has moved there from another position, or whether it is really one and the same electron with that observed in the previous position, regardless of their proximity. Since observations are disconnected, discrete events—with time (and space) gaps in between, during (and within) which we don’t know what a particle might be doing—subsequent observations of identical particles might in fact be observations of two different particles belonging in the same family and not observations of one and the same particle that might have moved from one position (that of the first observation) to the next (that of a subsequent observation). Without the ability to determine experimentally whether a particle has changed position, its motion—and motion in general—is a questionable concept.

In summary, without the ability to keep a particle under continuous observation, it is impossible to establish experimentally its identity, and therefore it is also impossible to experimentally verify that it has moved. In a sketchy analogy, because of the uncertainty principle, observations of tiny particles happen like so: you see a pawn on a square of a chessboard. Then you close your eyes for a bit. Upon reopening your eyes, you see a pawn on another square. Now, since you don’t know if your observations are of the same pawn (recall, pawns, like electrons, are all identical), and also since you haven’t really seen any pawn moving (for your eyes were closed between observations), in strict truth, a pawn’s (like an electron’s) motion is, to say the least, ambiguous. The analogy is not perfect because unlike a pawn, which appears at rest when observed, an electron is observed neither in motion nor at rest—just that it exists somewhere when observed.

Trying to capture the peculiar consequences of the uncertainty principle on observing and on motion, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote: “If we ask, for instance, whether the position of the electron remains the same, we must say ‘no’; if we ask whether the electron’s position changes with time, we must say ‘no’; if we ask whether the electron is at rest, we must say ‘no’; if we ask whether it is in motion, we must say ‘no.’”

Indeed, motion is not an experimentally verifiable phenomenon. Speak of the illusion of the senses.

Featured image: Zeno of Elea shows Youths the Doors to Truth and False (Veritas et Falsitas) by Pellegrino Tibaldi via Public domain [PD-US]

The post Is motion an illusion of the senses? appeared first on OUPblog.

Five great comedies from Hong Kong

At a time when Hong Kong’s status as a semi-autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China is under threat, we should not forget what the area’s former independence from the mainland once meant for its citizens and their cultural identity. During the 99 years that Hong Kong was under British governance, the tiny territory grew into an economic powerhouse. Without much government support, but with unusual financial and creative freedom, it built one of the world’s largest movie industries. This was a commercial cinema, much like Hollywood’s, designed to entertain audiences everywhere with local stars and home-grown genres such as kung fu, Triad gangster films, and a unique brand of Hong Kong comedy.

1. Drunken Master (Zui quan, 1978)

Typically, the humor in these films is manic, self-mocking, and robustly physical. Drunken Master makes fun of the martial arts action movies popularized by Hong Kong’s best-known practitioner, Bruce Lee. Here, it’s Jackie Chan who plays the legendary master of “drunken boxing,” a style of combat in which the fighter pretends to be drunk to confuse his opponent. Chan plays him as a lazy, mischievous youth who must learn discipline the hard way. Time and time again, he’s punished for his buffoonery—a fitting role for Chan, who acquired his gymnastic skills as a boy while suffering the rigorous, often brutal training for Peking Opera. Watch him practice under the tough tutelage of Beggar So. Then watch him put this training to the test against a formidable foe, with one hand in a fist and the other balancing a cup of wine. Among other things, these scenes remind us that pain and laughter often go together.

2. Project A (“A” gai wak, 1983)

Chan also starred in a series of comic action films. In Project A, he is a military cop fighting pirates in 19th century Hong Kong. The time and plot are pretexts for a parade of rollicking chases, funny faces, side-splitting stunts, and other visual jokes. There’s a tumultuous bar fight between rival police groups, a whacky bicycle pursuit, and an acrobatic fall from the clock tower that alludes to Harold Lloyd.

3. Spooky Encounters (Gui da gui, 1980)

Vampires, of course, are not native to Hong Kong, but director Sammo Hung managed to borrow the fanged menace of Transylvania and give him a distinctly Chinese identity. Delving into local lore, Hung came up with the spooky jiangshi, or “hopping vampires.” While western vampires wear capes, Jiangshi dress in Mandarin robes. They approach their victims in standing jumps, with long purple fingernails outstretched. As re-animated corpses, jiangshi can be subdued only by Daoist spells or a red dot on the forehead. In Spooky Encounters, Hung takes on a bet to spend the night in a haunted temple. The fun begins with an apple and a mirror. Before it’s all over, the encounter has involved fifty chicken eggs, dog’s blood, coffins, witches, sorcerers, and a monkey god. Mr. Vampire (Geung si sin sang, 1985) revived the jiangshi ghosts, who continued to run amok in sequels and spin-offs well the 1990s.

4. The Chinese Feast (Jin yu man tang, 1995)

The Hong Kong industry had perfected its formula for commercial success. Take a tested genre (action, horror), add some indigenous ingredients (kung fu fighting, jiangshi ghosts), and serve with healthy heaps of comedy. The recipe was put to delicious use in Tsui Hark’s The Chinese Feast, a high-energy lampoon of dueling chefs. Leslie Cheung plays a celebrity cook down on his luck who must fight his way back to the top by preparing the legendary Manchu Han Imperial Feast. His involvement with a street gang, a rival restaurant conglomerate, and the peculiar delicacies of Chinese cuisine—all give the film a home-made quality.

5. Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (Xi you: Xiang mo pian, 2013)

No Hong Kong actor or director has created more mischief and mayhem on the screen than Stephen Chow, the region’s undisputed King of Comedy. Best known in the West for Shaolin Soccer (Siu Lam juk kau, 2001) and Kung Fu Hustle (Gung fu, 2004), his wacky sendups of sports mania and the martial arts, Chow has also taken affectionate aim at foodie films (The God of Cookery/Sik san, 1996), romcoms (Love is Love/Wangfu chenglong), sci-fi (C17, 2008), and much more. A master of slapstick and smartass repartee, he perfected a style known as “tricky brain humor.”

Chow can be regarded as an avatar of China’s archetypal trickster, known as Monkey in the West. In countless stories, Monkey’s impudent behavior is endlessly amusing. He can be as playful as a child or as endearing as a clown, but he is also a constant threat to the established order. Even in heaven he causes havoc, which is why Buddha locks him in a cave. In Journey to the West, Chow retells the 1,300-year-old tale with live actors and CGI monsters. Their interaction is both fantastically flamboyant and unusually violent. Witness the scene in which a fish demon attacks a village. Not even children are spared. Or watch the ferocious fight between a pig demon and a warrior woman (Qi Shu as Miss Duan). Other moments can be more frolicsome, like the gender-bending scene in which Miss Duan manipulates a timid monk (Chow as Sanzang) like a marionette. As the tale bounces along, these shape-shifting figures cycle through the spectrum of human greed, rage, hubris, and other cardinal vices.

None of these films is overtly political. Like much commercial cinema, Hong Kong comedy is more about diversion than direct confrontation. That is not to say that Chinese humor always steers clear of criticism. In fact, there is a long tradition of questioning authority in clever ways that dodge punishment or censorship. Early scholar wits (huaji) told anecdotes and fables to temper the misuses of power. One story was about the King of Chu, who insulted an ambassador from the neighboring state of Qi. “There must be very few people in Qi,” sniped the king, “or why would they send me someone like you as envoy?” The ambassador replied, “We have a method for selecting envoys. If a state’s leader is competent, we send a good one. If not, we send an incompetent envoy. I’m one of the ineptest ambassadors in Qi, which is why I was sent to you.” More recent protests take the form of homonyms, a form of Chinese wordplay. In the 1930s, a popular anti-communist slogan was “Kill the pig and pluck its hair.” Everyone knew that the family name of Chairman Mao sounds like the word “hair” and that the family name of Marshall Zhu can also mean “pig.” The slogan was a code for killing Zhu and removing Mao from power. In our own time, political puns like this are common on the Internet.

Comical combat with hopping vampires, contentious chefs, or pig demons may seem remote from today’s confrontation between the people of Hong Kong and the leaders of China. What consolation does slapstick offer when real sticks are being wielded in the streets? But these Five films do demonstrate what can be achieved with creative freedom and an abiding sense of humor. They remind us that humor and survival are linked.

Featured Image Credit: A Birdseye View of Hong Kong by Ruslan Bardash on Unsplash.

The post Five great comedies from Hong Kong appeared first on OUPblog.

Why we can’t tell if a witness is telling the truth

Imagine that you are a juror in a trial in which the chief witness for the prosecution gives evidence about the alleged crime which is completely at odds with the evidence given by the accused. One of them is either very badly mistaken or lying. On what basis will you decide which one of them is telling the truth? And how sure can you be in your conclusion?

Perhaps demeanour, way of speaking and body language are high on your list of relevant factors to look at to decide if someone is being honest. These are probably the weakest indicators as to whether a witness is credible. A witness who is confident and spontaneous may be thought to be worthy of belief. But the impression of confidence and spontaneity may come from an honest witness because she has prepared carefully for trial, using her earlier truthful statement. Or it may come from a lying witness, who has also prepared carefully by learning his false story by heart. Lying is a cognitive skill and so the more you practice, the better you get.

A witness who is nervous and hesitant may not be very convincing but may well be telling the truth; many witnesses, even if they have prepared carefully, find the giving of evidence in court an unnerving experience, especially if they are young or otherwise vulnerable. Demeanour and delivery are not a reliable way of assessing credibility. Perhaps you have other indicators of likely accuracy and veracity. Was the witness’ account consistent or inconsistent; and was it a full and detailed account or did it have gaps? However, all these factors can mislead.

People often think that consistency with what the witness has said previously or with what is agreed or clearly demonstrated by other evidence is a strong indicator of reliability. But it may stem from deliberate deceit, including collusion, as when two corrupt police officers fabricate a case against the accused. Equally, consistent evidence may be unreliable because it is the result of innocent and accidental contamination, as when two witnesses find themselves talking about the event that both have just witnessed. Later, they may well find it difficult to distinguish between what they observed for themselves and what they were told by each other. When a witness has made a previous inconsistent statement, this is thought to indicate a lack of credibility, but it is often normal or explicable and may even be brought about by the nature of the interview process or the vulnerability of the witness when under cross-examination. The risk is particularly high in the case of a child victim of an assault, who may be questioned over and again. At some stage, the child may well take the line of least resistance and agree to whatever is being suggested, just to bring the whole process to an end.

A witness whose account has gaps and lacks detail is often regarded as an unreliable witness, whereas a witness who gives a full and detailed account is often thought to be reliable. However, gaps and lack of detail are the norm for most ordinary people doing their best to tell the truth as they remember it. A high degree of specific detail in long-term memory is unusual. Memories of experienced events are always incomplete. This is especially true in the case of adult memory of childhood events and witnesses to traumatic events when the brain, quite healthily, blocks out some of what the person witnessed.

Featured Image Credit via Shutterstock

The post Why we can’t tell if a witness is telling the truth appeared first on OUPblog.

July 6, 2020

The dividing line between German culture and Nazi culture

In November 1942, Anne Frank drafted a fictional advertising brochure for the rear part of the building in central Amsterdam that sheltered her and other Jews. Turning Nazi oppression on its head, she ruled that “all civilized languages” were permitted, “therefore no German.” Still, she was prepared to qualify the ban on the language of her native country, stating that “no German books may be read, with the exception of scientific and classical works.” The teenage girl did not object when her father gently imposed the plays of Goethe and Schiller on her. Not only that, she pinned a magazine picture of Heinz Rühmann, a popular actor who continued to work successfully all through the Third Reich, on a wall–long faded but perfectly discernible for visitors of the house that is named after her.

Even Anne Frank, who professed her love for the Netherlands as she was hiding from her erstwhile compatriots, remained somewhat equivocal about whether to abandon German culture altogether. Such ambiguity was all the more characteristic of older European Jews. Many struggled to believe that a nation known for its love of the arts and humanities could have committed itself to unprecedented brutality. In the Warsaw ghetto, some musicians played Beethoven in courtyards or, circumventing a ban on Jews playing German music, concert halls. Others packed their instruments before deportation in the hope that their tormentors would let them perform rather than send them to the gas chambers.

Appreciation of German culture belonged to a prewar world to which many Jews continued to hold on, in contrast to those who shifted their interests elsewhere or had already done so before 1939. There was a generational dimension to this divide. Anne Frank was less attached to German language and literature than her father. Another teenage diarist, Ana Novac, found the complaints of a Hungarian woman about the appalling conditions in Auschwitz rather quaint: “German culture! What a disappointment for someone who spent her holidays in Baden-Baden and read Faust!”

The issue of whether or not to distinguish German culture from its Nazi rendition also engaged non-Jewish Europeans and Americans as they were defining their stance in the course of the Second World War. Many artists and intellectuals in countries occupied by, or allied to, the Third Reich preferred romantic German culture to rationalistic French culture. For that reason, and because they hoped for a renewal of their own national cultures, they initially accepted Hitler’s new order. There were also less highbrow motivations for accommodation. Cinemagoers saw German comedies and costume dramas for their entertainment value at a time when domestic film production was curtailed and Hollywood imports were banned.

Resistance movements targeted such accommodation, and with it the entire distinction between German culture and Nazi culture. Consequently, they daubed posters advertising the fantasy film Münchhausen on the streets of Paris and Amsterdam with swastikas. Not unlike Anne Frank, one Dutch resistance paper granted that Germany had produced some cultural figures of European standing but insisted that the country had never lost its “barbaric characteristics.” Once the exploitative character of Nazi occupation became painfully evident and the military situation began to shift, such arguments gained in persuasiveness.

In countries that were fighting Hitler, propagandistic mobilization stood in tension with respect for German music or thinking. In Britain, émigré scholars exerting significant influence on their disciplines coexisted with radio features including machine-gun fire accompanied by Richard Wagner’s melodies. In the United States, posters and animated films liberally drew on ethnic stereotypes. As one programme-maker put it, his job was to fire up hatred and hence convey without nuance that “a German is a Nazi.” By contrast, the Office of War Propaganda, targeting both domestic and enemy populations, maintained that “Nazi ideology” contradicted “the decisive tendencies and achievements of German culture.”

This uncertainty, while reflecting widespread ambiguity towards Germany, was chiefly caused by the Third Reich itself. Its occupation regime rapidly shifted from promoting German culture in conjunction with respect for–some–other national cultures to unabashed domination by controlling film markets and looting museums. Already before 1939, the Third Reich had presented a somewhat blurry picture, blending extreme-right influences with nineteenth-century traditions and twentieth-century innovations. Because it often remained unclear what, exactly, was “Nazi” about this culture, conservative theatre directors and apolitical film comedians, provided they were not Jewish, could advance their careers or at least carve out a space for themselves.

Legitimate culture in the Third Reich was a broad church, which made it both incoherent and powerful. As a result, Germans could quite easily distance themselves from a caricatured image of Nazism after 1945, enjoying symphonic productions by much the same conductors or films with long-popular actors. But this is precisely why a full understanding of culture in the Third Reich should include the perspectives of the populations that this regime persecuted, occupied, or fought. For all her own ambiguity, Anne Frank was astutely aware that German cultural domination hinged on violence.

Featured Image Credit: by Jake Hills via Unsplash

The post The dividing line between German culture and Nazi culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers