Oxford University Press's Blog, page 146

June 11, 2020

Etymology gleanings for May 2020

English spelling

I promised not to return to Spelling Reform and will be true to my word. The animated discussion of a month ago (see the comments following the April gleanings) is instructive, and I’ll only inform the contributors to that exchange that nothing they wrote is new. It is useful to know the history of the problem being discussed, for what is the point of shooting arrows into the air? Look through the booklet by Walter W. Skeat The Problem of Spelling Reform. London: Henry Frowde, 1906. This was originally a paper read before the Royal Society; the tiny booklet (18 pages) has recently been reprinted. All the arguments and counterarguments were old and trite even then. We have posted Skeat’s portrait many times. It won’t hurt anyone to look at the great scholar again. Over the ages, spelling has often changed by decree or without it in various cultures. Some people were unhappy, others expressed satisfaction, and still others never noticed the difference. My colleague signs his letter with: “Your’s truly.” And my students often ask me: “Proffesor [sic], when is the paper do?” No version of the reform will affect them. Let every cobbler stick to his last and enjoy life. Time will show whether the Reform will ever materialize. In my opinion, it is long “overdo.”

The more we read Walter W. Skeat, the smarter we become. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The more we read Walter W. Skeat, the smarter we become. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The grammatical gender in language history

Old Germanic inherited three genders from Indo-European, but the assignment of the masculine, feminine, or neuter makes sense only if it is predictable, for example: “A noun ending in –a is (usually) feminine (as in Latin and Russian) or neuter (as in Greek).” But by looking at a word in Gothic, Old English, or Old Norse, we can seldom guess its gender. Therefore, it does not come as a surprise that many nouns vacillated between the masculine and the feminine or between the feminine and the neuter. Sometimes different dialects of Middle High German assigned different genders to the same word. As a result, the modern language occasionally retains the ancient vacillation, though Germans have the uncanny ability to remember the correct gender of all words, while foreigners have trouble in mastering even the system of two genders, as, for example, in French or Swedish. Bless your stars that English has lost gender distinctions (so far, mainly in grammar). I should perhaps add that a student of Old Germanic should not expect every noun to have the same gender as in Standard Modern German.

The force of short i

In my discussion of words like snitch and snatch (May 13, 2020), I wrote that, when there is a progression of vowels, be it in whippersnapper, tick-tack-toe, or Big Bad Wolf, the direction is always the same: from short i (which stands for something small) to a. Patter-pitter instead of pitter-patter would have produced a ridiculous anticlimax. Among other words, I mentioned wigwam. The objection from a reader was that wigwam is a borrowed word in English. The question was: “Is the progression discussed in the post a universal?” Yes, it seems to be such: i (as in bit) is a closed vowel, while, when we say a (as in bat), we open the mouth wide; hence probably the sound-symbolic reaction.

The origin of the word sword

An etymologist as the modern-day Lancelot. Image via Public Domain Vectors.

An etymologist as the modern-day Lancelot. Image via Public Domain Vectors.Since I don’t believe that Old Germanic borrowed words from the speakers of Ancient Greek, I’d rather stay away from discussing whether one sound from a Greek word could be added to a Germanic word (those interested in such procedures are advised to read Gogol’s play Marriage) or whether some Greek words were tortured into producing Old English nouns. I know that I’ll incur the wrath of my opponent, but I prefer to be conservative in linguistic reconstruction. The attacker’s flaming sword will probably try to destroy me, so that I have my harness and visor on. The comment on the Latvian words resembling sword is interesting, but the similarity is probably accidental. I am sorry that there is no English equivalent of the German term Benennugsmotif “the reason a word is called the way known to us.” Finding a true motivation for “calling a spade a spade” is the main task facing an etymologist. As we know, from the point of view of ancient speakers, the most noticeable feature of swords (strangely!) was not always their ability to cut. Compare Latin ferrum “iron; sword” (from the name of the material).

If, as I argued, sword and sward are related, the chance that sword was borrowed from some distant source diminishes. I have received a letter pointing to the similarity between Germanic swerð– and a Hebrew word. Again, the similarity is, most likely, coincidental. Viktor Levitsky, as pointed out in a comment, wrote an article about sword. He repeated his hypothesis in a Germanic etymological dictionary, published shortly before his death. The dictionary is, unfortunately, in Russian and will therefore remain closed to most of those who need it.

The latest works on the subject known to me are Friedrich Grünzweig, Das Schwert bei den Germanen… and Lisa Deutscher, Das Schwert—Symbol und Waffe…. Levitsky developed a theory of Germanic roots on which I deliberately did not touch, for it would have taken me too far afield. In my opinion, his main merit (as regards sword) is the insistence on the relatedness between sword and sward, the point first made by Sperber but ignored or ridiculed by everybody else. I am less enthusiastic about tracing the root of sword to the idea of cutting, but I am in general not too much interested in finding the ancient (reconstructed) Indo-European roots of the words under investigation. The reference to “shining” is my idea, because I tried to make sense of swords being “smooth.”

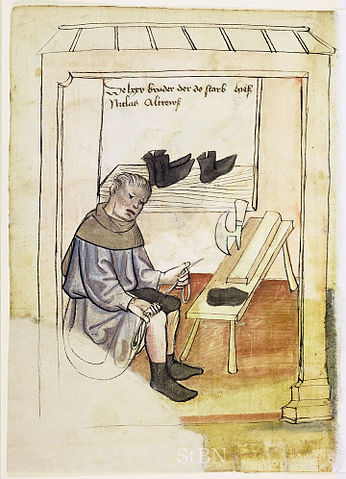

Let the cobbler stick to his last. Unknown artist, around 1425. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Let the cobbler stick to his last. Unknown artist, around 1425. Via Wikimedia Commons.A study in advanced Modern English

From a newspaper (a statement by an elected official): “A state full of graduating seniors have been told they can’t have an in-person ceremony,” L. tweeted. “Us elected officials [no commas] should be held to the same standard.” A forceful statement. It reminds me of two more in my archive: “Let’s you and I frame the discussion between you and I” and “Let I quote the letter to the editor.”

“Last semester, university senior *** said they were misgendered on the first day of class. Feeling unsafe from potential harassment, they dropped the course.” Compare the section on the grammatical gender above.

Out of the mouth of babes

Many years ago, I occasionally followed Gene Bluestein’s column Words to the Wise in The Fresno Bee. Here is an extract from his publication on May 15, 1992: “My wife taught in a kindergarten where one of the children complained, ‘Johnny said the F-word’. She said, ‘Tell him not to’. But after several repetitions, she wondered what these kids were in fact talking about. ‘What is the F-word?’ she asked. ‘Kiss my butt!’ said the child.” What’s in a word?

Feature image credit: Royal society meeting hall at Burlington house. Unknown author, 1906. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for May 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Why global crises are political, not scientific, problems

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize he was awarded in 2007, Al Gore, the former American Vice President, made the claim that “the climate crisis is not a political issue, it is a moral and spiritual challenge to all of humanity.” The reason why Gore does not see climate change as a political issue is presumably because he thinks it is obvious. In other words, he thinks that climate change will damage everyone’s interests because it will destroy the planet. It is therefore in everyone’s interests to do something about it and fast. In other words, there is no political decision to be made.

Lurking beneath this interpretation of Gore’s claim is the assumption that politics is predicated on the existence of differences. These differences might be about interests (self-interest) or they might be about values (what we think are important objectives for society irrespective of our particular interests). Politics is therefore defined as the process by which groups representing divergent interests and values make collective decisions.

Now, the claim that climate change is not a political issue is of doubtful veracity partly on the grounds that it does not affect everyone in the same way and, at least for the currently living, there is not an active threat to human existence. That is, acting on climate change, particularly when doing so has significant economic consequences, is not necessarily in everybody’s interests or not to the same degree.

What of the current pandemic? Is there a case for saying that coronavirus is not a political issue but merely one that requires the objective expertise and judgment of scientists and medical professionals? Listening to Government Ministers claim, as they often do, that they are merely following the science certainly gives credence to such a claim.

What it would require for politics, defined in the way I have done so above, to be absent in the coronavirus crisis is for it to threaten everyone in similar ways, and for acting on it to be consistent with universally held values. A useful parallel is the common threat often said to exist in the event of war. In Britain, for instance, the country’s internal politics was put on hold during the Second World War and there was no general election between 1935 and 1945. It is no accident, perhaps, that war-time metaphors have been regularly used in the pandemic crisis. Thus, we are at war with an invisible killer and healthcare professionals are on the front line against it.

Of course, war between sovereign states is predicated on the existence of conflict between them and, as the nineteenth century Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz memorably pointed out, war is “the continuation of politics by other means.” Given that the present pandemic is a global threat and sovereign states have been, for the most part, supporting each other in fighting it, there would seem to be a stronger case for regarding it as being above politics, similar, perhaps, to an attack on Earth by aliens as envisaged by science fiction writers.

It would be wrong, however, to regard coronavirus as a non-political issue. There might be a case for regarding it as such if it threatened all humans with the same outcome (death). This is clearly not the case. Indeed, for most people, COVID-19 is pretty harmless. For the young it barely registers. For others, particularly the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, it can and has been deadly. As a result, competing interests do exist. The action taken against it, in most cases some form of lockdown, does not serve everyone’s interests, and it serves some people’s interests much more than others.

Protecting people from the virus inevitably conflicts with some interests and values. Crucially, of course, there are acute economic costs which will be played out in declining standards of living in the future. There are also impacts on human development, not least in the case of the shut-down of schools and universities. Children’s prospects (particularly the prospects of children from poorer backgrounds) are likely to be damaged by their inability to access formal education. The negative psychological effects of social isolation should also not be underestimated.

Values, too, are under attack and not least the limits placed on freedom deemed necessary to control the transmission of the virus. It is one of the fundamental articles of liberal faith – exemplified by the political philosophy of John Stuart Mill – that the state should not intervene to prohibit “self-regarding” actions (those that affect the individual alone), irrespective of the risks the individual is willing to take. A counter argument here would be that anyone deliberately flouting the lockdown measures is behaving, as Mill would put it, in an illegitimately other-regarding fashion since the potential consequences – of further spreading the infection – will affect others negatively. A possibly useful compromise (one which is close to the strategy of the Swedish government) is to self-isolate those who are likely to be particularly vulnerable to the virus whilst allowing others to behave as relatively normal, thereby preserving at least some of their liberty.

The politics of coronavirus requires a balancing of the interests and values involved. The debate surrounding schools is instructive. The government has proposed the gradual reopening of schools but this proposal has met opposition from some teachers and parents as well as medical professionals. All of these actors have (some) competing interests which they will seek to defend and added to the equation are the interests of children (not always the same as their parents) which are probably more likely to be ignored.

The state’s role, in a democratic pluralist political system, is to seek to balance the competing interests that are articulated. Crucially, it cannot, if a fair compromise is to be achieved, prioritise the interests of one group over another, seriously disadvantaging the interests of others, unless a failure to do so is to put one group at serious and substantial risk.

Featured image credit: Markus Spiske, ‘Global climate change strike’, Unsplash (21 September, 2019)

The post Why global crises are political, not scientific, problems appeared first on OUPblog.

Six ways to reduce your environmental impact

Over the last 50 years, human population has doubled, and global trade has increased ten-fold, drawing more deeply on Earth’s natural resources, warming the climate, and polluting the global environment. If current climate trends continue, a third of the global population will live in places warmer than the heart of the Sahara Desert 50 years from now. Given the likely migration response to these and other changes, today’s youth will likely experience massive environmental and societal shocks during their lifetimes that were previously viewed as only distant risks to future generations. If we care about our children’s future, now is the time to fix this problem.

It is ironic that, as patterns of global degradation become more conspicuous, humanity has become less successful in curtailing planetary degradation. People don’t deliberately degrade Earth—our only home—but rather degrade it as a byproduct of efforts to improve people’s material lives in the short term. I used to think it was government’s job to tackle large-scale, long-term problems like these, but government often does a poor job of it for many reasons, including short time horizons (two to four-year election cycles, daily stock market fluctuations), vested interests that finance election campaigns, and limited spatial scale of concern (a politician’s district or, at most, his nation).

Solutions begin at home and actions by individual citizens—especially in developed nations—can reverse these trends and contribute to a more sustainable future. On average, those of us living in developed nations consume 32 times more energy and other resources than does the average person in the developing world. We can be very effective in reducing individual impacts on the global environment.

In 2019, 68% of people surveyed in developed nations viewed climate change as a major threat. Nonetheless, many people do not take actions that would reverse this trend because they think it would impoverish their lives. But citizens can reverse the trend of global environmental degradation, while improving their daily lives. It’s not that hard. Here’s a starting point:

Enjoy and celebrate nature and community with your friends and family. Time spent in nature as a child is one of the best predictors of environmental concerns of adults. Even people who pay no attention to nature benefit from it. For example, street trees cool their environment and reduced heat-wave fatalities by nearly 30% in elderly Chinese urban residents. Time spent in nature, whether it be wilderness, backyard gardens, or city parks, builds an ethic of stewardship for nature for today and the future.Be informed. Nature provides many critical benefits to society, including the food, fiber, and water we harvest; protection from changes in climate, severe storms, and wildfire; and the aesthetic and spiritual amenities that enrich people’s lives. Learn how changes in human activities degrade nature’s benefits and what you can do to sustain them.Support honorable consumption. Buy what you need and choose options that draw lightly on Earth’s resources. Among the 85% of Americans who do not live in poverty, increases in hours worked, income, and consumption do not increase happiness. Instead, time spent with friends and family, providing learning opportunities for our kids, and contributing to nature or community give greater satisfaction. Besides, unnecessary consumption increases household debt, which reduces happiness through financial insecurity.Show that you care. Habits and social norms that are highly visible are susceptible to change. These include both icons of conspicuous consumption, such as expensive cars and clothes, and environmentally friendly habits, such as bicycling to work and recycling. Be a role model for values you believe in rather than buying things just to keep up with your neighbors.Talk respectfully with others about choices that give you personal satisfaction. Seventy-five percent of Americans never talk with anyone over the course of a year about changes in climate or the environment. Tell people what you care about and why.Tell your leaders what you think is important and why. Vote, thank your leaders for good things they have done, and inform them of other actions that you advocate. If necessary, protest and shame those who operate outside of democratic processes. If everyone voted in ways that reflected their professed environmental concerns, there would be much stronger political support for climate action.If people who are concerned about the future act responsibly on its behalf, we can transform the world.

Featured image by Dan Meyers via Unsplash

The post Six ways to reduce your environmental impact appeared first on OUPblog.

June 9, 2020

The life of Charles Dickens [timeline]

Charles Dickens is credited with creating some of the world’s best-known fictional characters and is widely regarded as the greatest novelist of the Victorian age. Even before reading the works of Dickens many people have met him already in some form or another. Today marks the 150th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ death and to commemorate his life we created a short timeline showcasing a selection of events in Dickens’ life.

Feature image: Charles Dickens bust, by Mindspace Studio via Unsplash .

The post The life of Charles Dickens [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Gay rights, religion, and what’s wrong with principles

The Equality Act, which would protect LGBT people from discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations, has such broad support in public opinion that it ought to be able to sail through Congress. It won’t. Both sides are dug into positions that make legislation impossible. Conservative Christians regard the bill as an existential threat, because they reasonably fear that it would take away control of their own formative institutions, such as hiring of teachers at religious schools. Gay rights supporters regard any compromise that would ease those fears as morally odious, like making a deal with racists.

The Democrats have united behind the Equality Act, which has extremely narrow exceptions for religious institutions. It passed the House by a huge 236-173 majority in May 2019, with no Democrats opposed and eight Republicans in favor. That is as far as it will get. Unless the Senate filibuster is abolished, it won’t become law even if the Democrats win the Senate and the Presidency in November. That is bad news for LGBT people, who now are protected from discrimination in only 21 states and the District of Columbia.

An obvious solution would be to moderate the bill in order to accommodate the religious dissenters. That has been proposed in the Fairness for All Act, the compromise that offers the broad protections of the Equality Act with significant religious exemptions. The bill’s accommodations are narrowly targeted, for instance allowing religious organizations to employ only people who fully adhere to their religious beliefs and standards. It has been denounced by both sides.

Opposition from the left rests at bottom on the racism analogy: if racists don’t get religious accommodation, why should heterosexists? So negotiation can’t even begin.

The racism analogy is most commonly used to claim that the religious objectors are lying about their motives. A majority of the US Commission on Civil Rights spoke for many when it declared that proposals for religious accommodation “represent an orchestrated, nationwide effort by extremists to promote bigotry, cloaked in the mantle of ‘religious freedom,’” and “are pretextual attempts to justify naked animus against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.”

It’s not true. There is obviously a lot of hatred against gay people out there, often manifesting in violence. But many decent people honestly embrace the sexual ethics that their religions have taught for centuries. I’ve been a gay rights advocate for over thirty years, and I’ve argued with many of them. I can report that they are otherwise admirable people who happen to hold wrong and destructive beliefs. You might regard those beliefs as so daffy that no one could really believe that stuff. But that’s the problem of religious diversity. Nothing is more manifestly implausible than other people’s religions.

The better analogy is with the anti-vaxxers, who foolishly think that they are protecting their children by refusing to vaccinate them. They are a public health menace. But it wouldn’t advance understanding to claim that their ignorant notions are an insincere pretext for hurting children.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that there could not and should not have been religious exemptions from the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But it isn’t 1964 anymore.

America has a long tradition of accommodating religious dissenters. As a general matter, the law should not strive to stamp out any subculture and make its members outcasts. Racism has been so pervasive and destructive that these two principles are appropriately overridden. The civil rights struggle demanded coercive cultural reconstruction, especially but not only in the states of the former Confederacy. That’s not our situation with respect to antigay discrimination, where the needed cultural changes are already happening.

The question is not simply whether people are acting on the basis of repugnant ideas. There are a lot of repugnant ideas around. It is whether there should be cultural war. That question, like any decision to go to war, depends on prudential assessment of likely consequences. In the case of race, there has been progress, but the war isn’t over. Zero tolerance remains necessary. In the case of sexual orientation, war is unnecessary and unlikely to improve matters.

Both sides think this disagreement concerns a matter of deep principle. Religious liberty and nondiscrimination are each understood as moral absolutes.

People tend to think about this issue the way lawyers are trained to think about conflict resolution: by devising abstract principles that should cover all future cases (and which incidentally entail that their side wins). But sometimes the right thing to do is not to follow a principle, but to accurately discern the interests at stake and cobble together an approach that gives some weight to each of those interests. Ethics is not only about principles. There is a tradition in moral philosophy, going back to Aristotle, that holds that a good person does not necessarily rely on any abstract ideal, but rather makes sound judgments about the right thing to do in particular situations. Sometimes principles are overbroad generalizations from experience, and distract us from the moral imperatives of the situation at hand.

The principles at issue here seem irreconcilable. But they are themselves parasitic on interests. The way to think clearly about the conflict is to look past the principles to the underlying interests. Discrimination harms its victims’ urgent interest in equal treatment in public spaces. Religious liberty protects what many people regard as their deepest concerns. The legal rights in question are tools for protecting those interests.

In this age of political polarization, America urgently needs a narrative in which there is a legitimate place for everyone. Compromising this issue could be a step in that direction.

I’ve worked very hard to create a regime in which it’s safe to be gay. I’d also like that regime to be one that’s safe for religious dissenters – even the ones I strongly disagree with.

Arguments about the gay rights/religious liberty conflict often talk past each other, because they often focus on one of the interests in question and ignore the other. The principles are in unresolvable tension. The interests are not. There are ways to ensure that all the relevant interests are accommodated. This may require some modification of the principles. Unless we do that, we can’t accomplish what most of us want, such as antidiscrimination protection for gay people. What ultimately matters is not the principles but the people. We only care about the principles because we care about the people.

Featured Image Credit: Person holiding multi-coloured heart-shaped ornament by Sharon McCutcheon via

The post Gay rights, religion, and what’s wrong with principles appeared first on OUPblog.

June 8, 2020

John Dewey’s aesthetic philosophy

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and social reformer who developed theories that changed philosophical perspectives and contributed extensively to education, democracy, pragmatism, and the philosophy of logic, politics, and aesthetics in the first half of the twentieth-century.

Born in Burlington, Vermont, in 1859, Dewey graduated from the University of Vermont in 1879. Following his graduation Dewey taught for a few years until he concluded that teaching at primary and secondary schools did not suit him. He enrolled at Johns Hopkins University to study for his PhD. After teaching at the University of Michigan and then at the University of Chicago, Dewey finally settled at Columbia University.

Dewey contributed substantially to various philosophical and interdisciplinary fields throughout his life, including aesthetics. He was, along with historians Charles A. Beard and James Harvey Robinson, and economist Thorstein Veblen, one of the founders of The New School, a private research university in New York City founded in 1919. In 1899 he was elected president of the American Psychological Association.

The principle of aesthetic philosophy is linked with theories of beauty, and the philosophy of art. Dewey’s most well-known work on aesthetics is his book, Art as Experience (1934). This was originally a speech he delivered at the first William James Lecture at Harvard University in 1932. Art and aesthetics, Dewey suggested, are intertwined inextricably with the culture and surroundings in which they stand. Therefore, to understand art and its aesthetic value, it is necessary to look at it within life and the outside experiences in which the art exists. As aesthetic experience bears organic origins, Dewey argued in Art and Experience that aesthetic experience can be recognised in everyday experiences, events, and surroundings.

Dewey’s theory on aesthetics has been a point of reference across various disciplines, which include psychology, pragmatics, democracy, and education, as well as new media; examples of which include computer animations and virtual worlds. His work has also been an inspiration to figures such as A.C. Barnes, founder of the Barnes Foundation, an art museum and educational institution. Barnes’s ideas of art in life, and the massive art collection he eventually accumulated in Philadelphia, were somewhat inspired by Dewey’s aesthetic philosophy, and he attended a seminar by Dewey in 1918 at Columbia University. Likewise, Dewey’s philosophy on aesthetic art drew some inspiration from the collections at the Barnes Foundation.

Dewey led a successful career which established him as a great, revered figure of modern western philosophy, and his work is still relevant to this day. Dewey lived a long, fulfilling, and successful life and career until his death on 1 June 1952 from pneumonia, aged 92.

Featured Image Credit: painting by Robert Delaunay, 1912, ‘Windows Open Simultaneously (First Part, Third Motif)’ oil on canvas via Wikimedia Commons

The post John Dewey’s aesthetic philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

How anti-immigration policies hurt public health

Immigration is neither a new issue nor an exclusively American one. In 2017, there were more than 250 million immigrants living worldwide, and about 2.4 million people migrate across national borders each year. Migration also occurs within national borders—it is estimated that more than 750 million people live within their country of birth, but in a different region. Economic, political, and social forces drive migration. Migrants who are forced to leave their country due to war or persecution become refugees; there were over 65 million refugees worldwide at the end of 2017.

The health of immigrants in their adopted home is strongly shaped by social, economic, and political conditions in that country. Legal status in the host country, for example, is associated with access to a broad range of health services and resultant better health. A study in Denmark found that while refugees were disadvantaged in terms of some cardiovascular disease outcomes, and equal or better off than a Danish-born comparison group in others, family-reunified immigrants had significantly lower incidence of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and myocardial infarction across the board.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, aggressive anti-immigration policies create poor health for the population they target. For example, family separation and detention at our borders traumatize families, deepening the mental health needs of this vulnerable group. And federal raids can affect the birthweight of babies born to USborn Latina women, following immigration authority raids in search of undocumented Latinos.

Creating the conditions for immigrants to stay healthy helps us all. Consider that a measles outbreak in Minnesota was fueled by low vaccination rates among refugees, who often mistrust health providers and fear discrimination and deportation. Ultimately, this outbreak—caused by the conditions of marginalization faced by immigrants—threatened the health of everyone, immigrant and native-born alike. Policies which further marginalize immigrant communities can increase this risk. Rather than listen to voices that rail against the imagined evils of immigration, we should do all we can as a country to maximize the health of immigrants, by working to include them in the fabric of American life and providing them with the basic social services they need in order to be well.

Featured Image Credit: by Cytis via Pixabay

The post How anti-immigration policies hurt public health appeared first on OUPblog.

June 7, 2020

Everyone and their dog

A writer friend of mine posted a social media query asking for advice on verb choice. The phrase in question was “… since everyone and his poodle own/owns a gun…” Should the verb be in the singular or the plural?

More than fifty people weighed in. Some reasoned that there was a compound subject but the noun closest to the verb is singular, so the writer should choose owns. That thinking is based on the prescriptive rule for disjunctions like or rather than conjunctions like and. When there is a compound subject joined by or, the noun closest to the verb determines agreement:

Neither the coach nor the players were at fault.

Neither the students nor the teacher is correct.

But with and, compound nouns are generally in the plural, regardless of order:

The coach and the players were at fault.

The players and the coach were at fault.

The students and the teacher are correct.

The teacher and the students are correct.

So should the verb be the plural own because the compound subject is connected by and? Some people suggested resolving the issue by relying on substitution or analogy: “Both the poodle and everyone are singular,” someone proposed. “Replace them both with other normal singular nouns to figure out the construction.”

Substitution and analogy are often useful tools in figuring out a grammatical pattern, but are everyone and his dog normal singular nouns? Not really. Everyone is what’s known as an indefinite pronoun which, like its less formal counterpart everybody, is singular (we say Everyone is reading, not Everyone are reading). By itself, the phrase his dog would also be singular, but his dog is not functioning as a normal noun in the expression Everyone and his dog.

Instead, it is being used idiomatically—non-referentially—to emphasize everyone. Everyone and his dog is a folksy way of emphasizing everyone, but the verb would still be the singular owns. The situation is similar to Every Tom, Dick and Harry, which is another emphatic idiom: we would not write Every Tom, Dick and Harry own a gun.

We can check result this too by ear if we replace own/owns with a verb that shows more contrast between singular and plural, like the forms of to be.

Everyone and his dog is on the road today.

Every Tom, Dick and Harry is at the park.

but not

Everyone and his dog are on the road today.

Every Tom, Dick and Harry are at the park.

Semantics, substitution and an ear for what sounds natural help us to resolve such grammatical puzzles. Sometimes too they open the door to interesting further issues.

As some commenters on Everyone and his dog pointed out, there is also the question of the pronoun. One suggested that everyone and everybody “used to be” singular and thus required singular pronouns (as in Everyone has his or her own cup), but that today more and more speakers, writers, and style guides were recommending singular their. It’s certainly true that singular their is well on its way to becoming the norm, but the idea that everyone and everybody used to require singular verbs needs some context and correction.

Their has been used to refer to everyone and everybody pretty much as long as English has been written. The earliest OED citation is from the late 14th century in Wycliffe’s Bible: “Each one in their craft is wise” (“Eche on in þer craft ys wijs“) and singular their was used by such writers as Shakespeare, Thackeray, and Austen. It was when grammarians got their hands on English that some started worrying about their disagreeing with one, as linguist Ann Bodine pointed out in her 1975 article “Androcentrism and Prescriptive Grammar.”

Over time, their has become increasingly used as an alternative to the generic masculine (as in Every student should make an appointment with their advisor, Who thinks they can solve the problem, or The next president will have to quickly determine their priorities). And it is commonly used as an alternative to singular gendered pronouns (as in Finn asked me to let you know they would be a little late). As Dennis Baron, has wonderfully documented in his What’s Your Pronoun: Beyond he and she, there is a long history to the use of gender-neutral and gender neutral pronouns and the debates surrounding them.

In the end, after much back and forth between owns and own, idioms and compounds, and his and their, the final result was Everyone and their poodle owns a gun.

And everyone got to express their opinion.

Featured image credit: Photo by Zakaria Zayane on Unsplash

The post Everyone and their dog appeared first on OUPblog.

June 4, 2020

How paternity leave can help couples stay together

The birth of a child is accompanied by many changes in a couple’s life. The first few weeks and months are a time of acquiring new skills and creating new habits which allow parents to carry on with their other responsibilities while also caring for the new family member. Many decisions need to be made: Who does the cleaning? Who does the grocery shopping? Who cooks? Who feeds and changes the baby?

In recent years many countries have acknowledged the importance of fathers taking parental leave on egalitarian distribution of paid and unpaid work between fathers and mothers. As a consequence some countries, including Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Spain, have earmarked part of the parental leave to fathers. Making part of the leave non-transferable between parents has created significant incentives for fathers to stay at home to care for their children. However, the change in fathers’ participation has often been very gradual and few countries have experienced a discrete change in the use of paternity leave, making it difficult to evaluate its effects.

Iceland is a notable exception. The introduction of a non-transferable paternity leave in 2001 lead to an immediate and significant increase in the proportion of men taking parental leave. Before 2001 the parental leave in Iceland was a family entitlement with a 6-month duration and compensated with a fairly low flat-rate benefit and less than 1% of fathers took advantage of it. The proportion jumped to 82% following the 2001 reform when the leave was increased to 9 months (in steps) paid at 80% of the salary, of which 3 months were exclusively reserved for fathers. The sharp increase in the men taking off time to care for their children creates a unique opportunity to evaluate its effect.

It appears that reserving part of the parental leave for fathers, thereby making the sharing of childcare responsibilities more equal, leads to significantly fewer couple separations. The drop in divorces is not just transitory, but rather appears to be a permanent one, as the difference in the proportion of couples divorced remains throughout the fifteen-year period that we follow them. Among the parents who did not get paternity leave, 40% were separated fifteen years after the birth of their child. Our results indicate that a paternity leave reduces the divorce rate by approximately nine percentage points.

Historically and throughout the world, it has been almost exclusively women who take time off from work to care for their children first after their birth and therefore spend more time within the household than their husbands. This time at home does not only influence the daily lives of parents right after the birth of a child but also, more generally, parental norms and practices. The birth of the first child therefore often induces a system where women are responsible for a larger share of traditional household tasks, such as childcare, cleaning and cooking, while the men are responsible for bringing home the bacon. But given that the birth of a child has an influence on the division of labor between mothers and fathers is seems likely that the design of parental leave systems may have important implications as well. Whether it affects parents’ behavior and decisions, and what the effects are, is a highly policy relevant question.

The fact that the introduction of a paternity leave lead to a decrease in divorce rates suggests that paternity leave policies are not only valuable because they can influence the labor market attainment of women but also because they can lower divorce rates by directly reducing household stress and conflicts.

Featured Image Credit: Family Tree by Mabel Amber. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How paternity leave can help couples stay together appeared first on OUPblog.

June 3, 2020

Twelve books that give context to current protests [reading list]

Cities across the United States have seen ongoing protests since the death of George Floyd while in police custody on 25 May. Conversations are taking place on social media as well as in the real world, and media coverage has been relentless. We at Oxford University Press would like to highlight some of our books across politics, history, and philosophy that we hope can contribute to the important conversations currently taking place and provide valuable context. Where possible, we’ve made some of these books available at no cost for a limited time.

American While Black: African Americans, Immigration, and the Limits of Citizenship by Niambi Michele CarterCarter argues that immigration, both historically and in the contemporary moment, has served as a reminder of the limited inclusion of African Americans in the body politic. As Carter contends, immigration provides a way to understand the nature and meaning of black American citizenship–specifically the way that white supremacy structures and constrains not only African Americans’ place in the American political landscape, but the black community’s political opinions as well.

American While Black is free on Oxford Scholarship Online until 10 July. The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea by Christopher J. Lebron

Started in the wake of George Zimmerman’s 2013 acquittal in the death of Trayvon Martin, the #BlackLivesMatter movement has become a powerful campaign to demand redress for law enforcement injustices against the African American community in the United States. Drawing on the work of revolutionary black public intellectuals, Lebron clarifies what it means to assert that “Black Lives Matter” when faced with contemporary instances of anti-black law enforcement. Situational Breakdowns: Understanding Protest Violence and Other Surprising Outcomes by Anne Nassauer

Nassauer demonstrates that when routines break down, surprising outcomes often emerge. Focusing on detailed accounts of peaceful and violent protests from the 1960s until 2010, violent uprisings such as Ferguson 2014, and armed store robberies caught on camera, Nassauer argues we can understand how and why routine interactions break down by looking at how situations develop systematically.Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism by Allissa V. Richardson

This book reveals how the perfect storm of smartphones, social media, and social justice empowered Black activists to create their own news outlets, which continued a centuries-long, African American tradition of using the news to challenge racism. Bearing Witness While Black is the first book of its kind to identify three overlapping eras of domestic terror against African American people–slavery, lynching, and police brutality–and explain how storytellers documented such atrocities through journalism. Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970s Shootings at Jackson State College by Nancy K. Bristow

Minutes after midnight on 15 May 1970, white members of the Jackson city police and the Mississippi Highway Patrol opened fire on young people in front of a women’s dormitory at Jackson State College, a historically black college. Just ten days after the killings at Kent State, the attack at Jackson State never garnered the same level of national attention. In the aftermath, the victims and their survivors struggled unsuccessfully to find justice. The shootings were soon largely forgotten except among the local African American community. This book reclaims this story and situates it in the broader history of the struggle for African American freedom in the civil rights and black power eras.

Steeped in the Blood of Racism is free on Oxford Scholarship Online until 10 July.Black Software: The Internet & Racial Justice, from AfroNet to Black Lives Matter by Charlton D. McIlwain

Activists, pundits, politicians, and the press frequently proclaim today’s digitally mediated racial justice activism the new civil rights movement. In Black Software, McIlwain shows how the story of racial justice movement organizing online is much longer and more varied. Chronicling the long relationship between African Americans, computing technology, and the Internet from the 1960s to present, the book examines how computing technology has been used to neutralize the threat that black people pose to the existing racial order, but also how black people seized these new computing tools to build community, wealth, and wage a war for racial justice. Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction by Jim Downs

Downs recovers the untold story of one of the bitterest ironies in American history–that the emancipation of the slaves had devastating consequences for innumerable freed people. Slaves who fled from bondage during and after the Civil War did not expect that their flight toward freedom would lead to sickness, disease, suffering, and death. But the war produced the largest biological crisis of the nineteenth century, with deadly consequences for hundreds of thousands of freed people.

Sick from Freedom is free on Oxford Scholarship Online until 10 July. A Duty to Resist: When Disobedience Should be Uncivil by Candice Delmas

Advocates from Henry David Thoreau and Mohandas Gandhi to the Black Lives Matter activists have recognized that there are times when, rather than having a duty to obey the law, citizens have a duty to disobey it. There are limits: principle alone does not justify law breaking. But Delmas argues that uncivil disobedience can sometimes be not only permissible but required in the effort to resist injustice.

A Duty to Resist is free on Oxford Scholarship Online until 10 July. Until There is Justice: The Life of Anna Arnold Hedgeman by Jennifer Scanlon

Scanlon presents the first-ever biography of Hedgeman, a demanding feminist, devout Christian, and savvy grassroots civil rights organizer. Anna Arnold Hedgeman played a key role in over half a century of social justice initiatives. Hedgeman ought to be a household name, but until now has received only a fraction of the attention of activists like A. Philip Randolph, Betty Friedan, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Most of 14th Street Is Gone: The Washington, DC Riots of 1968 by J. Samuel Walker

Walker’s book takes an in-depth look at the causes and consequences of the Washington, DC, riots of 1968. It shows that the conditions that existed in the city’s low-income neighborhoods helped generate the problems that erupted after Martin Luther King’s murder. The book also discusses the growing fears produced by the outbreaks of serious riots in many cities during the mid-1960s. Walker analyzes the reasons for the riots and the lessons that authorities drew from them. He also provides an overview of the struggle that the city faced in recovering from the effects of the 1968 disorders. The Color of American Has Changed: How Racial Diversity Shaped Civil Rights Reform in California, 1941-1978 by Mark Brilliant

Brilliant examines California’s history to illustrate how the civil rights era was a nationwide and multiracial phenomenon–one that was shaped and complicated by the presence of not only blacks and whites, but also Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans, and Chinese Americans, among others. The Golden State’s status as a civil rights vanguard for the nation is due in part to the numerous civil rights precedents set there and to the disparate challenges of civil rights reform in multiracial places. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice by Raymond Arsenault

They were black and white, young and old, men and women. In the spring and summer of 1961, they put their lives on the line, riding buses through the American South to challenge segregation in interstate transport. Their story is one of the most celebrated episodes of the civil rights movement, yet a full-length history has never been written until now. In these pages, acclaimed historian Raymond Arsenault provides an account of six pivotal months that jolted the consciousness of America.

Feature image created by OUP.

The post Twelve books that give context to current protests [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers