Oxford University Press's Blog, page 147

June 3, 2020

The history of the word “sword”: Part 2

Last week (May 27, 2020), I discussed two attempts to solve the etymology of sword. The second of them would not have deserved so much attention if Elmar Seebold, the editor of the best-known German etymological dictionary, had not cited it as the only one possibly worthy of attention. His is a minority opinion, which does not mean it is wrong, though I believe it is.

Whenever we try to reconstruct a linguistic fact, it is reasonable to follow the model of widening circles: first look for the source nearby, then a little farther, and so on, and, if all such clues fail, suggest a borrowing. Although this procedure does not mean that a borrowing is in principle less likely than a source round the corner, the detective procedure suggested above is logical. (In the Russian fairy tale of the frog princess, three princes were told to shoot arrows and bring wives from the places where the arrows would land. As usual, the youngest brother had bad luck: his arrow fell in a nearby swamp, and he had to marry a frog, but that frog turned out to be a real princess. Hence the moral: explore the home swamp before going abroad.) That is why I ended the previous post with the question about the Germanic (rather than Luvian, Sanskrit, Greek, or Latin) words that resemble sword.

Seek happiness in the nearby swamp. “The Frog Prince” by Anne Anderson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Seek happiness in the nearby swamp. “The Frog Prince” by Anne Anderson. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.However, before we begin our search, it should be remembered that in Engl. sword, w was at one time pronounced (as also in two, for example: compare twain, twice, and twin) and that the vowel o is secondary; it arose under the influence of that very w. This may be called the Cheshire cat effect (the creature is gone, but its smile remains); that in German, s yielded sch (pronounced as Engl. sh): hence Schwert; while in Dutch, this s was voiced: hence zwaard. Finally, the ancient final consonant was ð (= Engl. th in the). Thus, the Germanic protoform of sword (without Gothic, where the word did not occur) was swerð-; the hyphen stands for the ending that does not interest us here.

English sword has one look-alike, namely, sward, and we’ll return to it later. German has schwer “heavy” and Schwär(e) “ulcer, festering sore, abscess” (related are Geschwür, the same meaning; schwären “to fester,” and the much more familiar schwierig “hard, difficult”). However, schwer, with cognates in and outside Germanic, had a long root vowel in the past and cannot be related to swerð-, because short e and long e (the latter from long æ), do not alternate by ablaut.

In contrast, Schwär(e) turned out to be a promising candidate for being a member of the sword family. The Schwert ~ Schwäre comparison suggests that the sword got its name because it was a weapon that caused pain by incurring wounds. This explanation of the word was adopted in the most influential dictionary of Indo-European, but in 1932, Willy Krogmann, at that time a young scholar, explained that the idea of “pain” must be traced to “piercing,” as, for example, in Engl. bitter from “biting.” We can still find Krogmann’s explanation in the dictionaries that venture to say something about the distant origin of sword beyond listing cognates (the most common case). The objections to this etymology (sword as a piercing weapon) are several. Two are worthy of mention: the function of the suffix –ð (from –ða) remains unexplained, and, if sverð– meant “piercer, cutter,” it is rather strange that the word was neuter, rather than masculine (it is still neuter in Dutch, German, and Scandinavian).

An old Germanic sword. It is certainly not wooden. Image by Anagoria. CC by 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

An old Germanic sword. It is certainly not wooden. Image by Anagoria. CC by 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.I am now coming to the culmination of my story. Etymologies are seldom impeccable, but one should never ignore small complications. Here is one of them. Dutch zwaard means “sword” and (!) “leeboard”; middenzwaard means “centerboard.” No one doubts that zwaard1 and zwaard2 are two senses of the same word (“sword” and “board”), rather than homonyms. How could that happen? In 1915, Hans Sperber, an active etymologist (among many other things), published an illustration of a wooden club with a sharp side, used in South America as a kitchen board for cutting ham and as a potential weapon. In some ways, it resembles the blade of a sword. Sperber stressed the likeness between two forms—a side of bacon and a slab of timber cut from a tree trunk—and noted that both can be called flitch in English and baco in Swedish (baco is related to Engl. bacon). He believed that the objects once called swords first functioned as boards for cutting meat, and referred to German Schwarte “bacon rind, crust.”

Sperber’s hypothesis has almost never been discussed. Jan de Vries, one the most distinguished philologists of the twentieth century, mentioned it in his etymological dictionaries of Dutch and Old Icelandic and suppled the reference with an ironic exclamation mark (read: “Can you imagine such nonsense?”). Several years ago, our contemporary expressed doubts about the development from “a side of meat” to “a side section of a piece of wood.” However, no one until very recently has returned to a possible connection between Schwarte and Schwert. Only the Russian and Ukrainian researcher Viktor Levitsky discussed it at length, but his conclusions about the origin of the root are beyond the subject of this post. Note: in English, the corresponding pair is sword and sward. I promised to return to sward, and this is the time to do so.

The two words (sword and sward, from swerð– and swarð-) are related by ablaut, like, for instance, German sterben “to die” and its past tense starb. At one time, Engl. sward meant “skin of the head.” Perhaps the word is a borrowing from Scandinavian. In any case, its initial sense must have been “a smooth surface.” Engl. sward and greensward (see the header!) refer to an upper layer of the earth.

The origin of sward ~ Schwarte is allegedly “unknown,” but at least two things about it are known: sward is, almost certainly, related to sword, and Dutch zwaard means both “sword” and “side of wood, etc.” Middle Dutch swarde meant “hairy skin”; the earliest Dutch forms of the word for “sword” were spelled as swart and swert (with final t going back to d). They looked like twins even then.

Where the paths of sword/sward and German Schwert/ Schwarte crossed remains unclear. We may be dealing with one ancient word that split into two or with two close synonyms in different grades of ablaut which influenced one another. Both seem to have designated an object having a smooth surface. It is therefore not unlikely that sword first denoted a utensil having this characteristic, and that later the name was transferred to the weapon. The sword, it appears, was called “sword” because it was smooth and (?) hence shining.

The oldest fanciful etymologies of sword are rather numerous. Only one deserves mention here. It has been suggested that Latin sorbus “service tree” (a kind of mountain ash or rowan tree; Engl. service in its name is an alteration of sorbus) is a cognate of swerð-. This derivation assumed that sorb- (from sworb?) had once designated a spear and a sword. Such cases are rare but known: one example is Old French glaive. Yet the existence of wooden swords finds no support in archeology. Since Sperber derived sword from the name of a wooden board, he shared the sorbus idea. There is no need to defend it. Also, the origin of sorbus is unknown, and one word of undiscovered etymology should never be used to explain the history of another obscure word. The path I suggest was from an object with a smooth (and shining) surface to the weapon. The distant origin of the root should remains a matter of conjecture.

This is a service tree: nothing to do with service or swords. Sorbus domestica by BotBln. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a service tree: nothing to do with service or swords. Sorbus domestica by BotBln. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Feature image credit: Photo © David Wright. CC-by-SA 2.0 via Geograph.uk.

The post The history of the word “sword”: Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

June 2, 2020

What history can tell us about infectious diseases

One of the remarkable achievements of the past hundred years has been the reduction of the global toll of death from infectious disease. The combination of applied biological science, improved living and working conditions, and standards of living, together with the benefits of planned parenthood, have transformed the health landscape for millions of people, not least in the developed world. Unfortunately, this led to the belief that these developments had led to the disappearance of infectious diseases as major public health issues with a resulting rundown of public health systems especially in the decades following the Second World War.

The stark message of the current global pandemic of COVID-19 is that we can never afford to lower our guard; that nature has many more tricks up its sleeve, especially in the form of novel forms of infection, especially those emerging where the delicate ecological balance of populations and their habitats is disrupted by poverty, urbanization, and the incursion of people into the territory of other species with their own unique commensal organisms.

In 1918, as the First World War was drawing to a close, the so-called Spanish Flu was brewing in army mobilisation camps across the United States. The first documented influenza cases occurred in the poverty-stricken rural county of Haskell, in Texas, where a local family doctor noticed the occurrence of a stream of atypical respiratory attacks of varying severity. His efforts to alert the public health authorities were of no avail and within months the influenza virus had spread throughout the military bases around America. In due course it made its way to the trenches of the Western Front in Europe, killing thousands on both sides of the conflict. Having seemed to burn itself out during the summer months, the epidemic returned with a vengeance in September 1918, sweeping around the world and leading to the deaths of between 50 and 100 million, mostly younger, people during 1918/19. A further, third wave in 1920 turned out to be much milder, reflecting the rise of some level of immunity among the human herd and probably an attenuation of the virus itself.

Since that time our knowledge of viruses has increased substantially and vaccines have been developed to protect human populations against the most common circulating strains of the influenza virus. Nevertheless, serious pandemics have occurred from time to time, notably in 1957 and 1968, carrying off tens thousands of vulnerable, usually older people. In the meanwhile, the health policy mindset of politicians and medical leaders had tuned out of a focus on infectious disease as being something for the history books to be replaced by a concern for heart disease, cancer, for long term conditions and the diseases of an ageing population. Nature’s surprises that began in the 1980’s should have been a wakeup call to the effect that classical public health will always have the potential to be catastrophically contemporary.

In the United Kingdom, the first warning that we were in danger of failing to keep on top of the basics of public health came in the 1980s with a salmonella outbreak in a Yorkshire psychogeriatric hospital that led to 19 deaths and an outbreak of Legionnaires disease in a Stafford hospital that led to 22 deaths. Although the government took measures to strengthen our public health resilience, these incidents were a portent of what was to come.

Beginning with Bovine Spongeiform Encephalitis ( Mad Cow disease) in 1986—followed by Avian flu in 1997, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002, Pandemic H1N1 Swine Flu in 2009, and Ebola in 2014—a whole succession of novel infections with origins in other animal species began infecting humans. The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York in 2001 reinforced the need for disaster and emergency preparedness, including that for incidents involving biological and germ warfare agents. This led to a renewed emphasis on planning and resilience for a range of eventualities.

Tragically the global economic crisis and meltdown of 2008 had ramifications for public spending, leading to a decade of austerity in which some countries, including the United Kingdom, took their eye off the public health ball. In 2020 with the advent of the most serious global pandemic for 100 years the ensuing weaknesses were exposed at great human cost.

The aphorism that those who forget their history are destined to repeat it has never seemed more apt.

Featured image by Ryoji Iwata via Unsplash.

The post What history can tell us about infectious diseases appeared first on OUPblog.

How after school music programs have adapted to online music playing

“OrchKids is working hard to stay ahead of the curve!” That’s the message delivered this spring to friends and supporters of OrchKids, a free after-school music instruction program for more than 2,000 Baltimore students, pre-K through high school. In March 2020, OrchKids staff had to totally change their way of teaching. The public schools where they held their group classes shut down abruptly, because of a government mandate aimed at slowing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

OrchKids educators were determined not to let the shutdowns flatten their mission of bringing music-making to youngsters who otherwise would not have the chance to be involved in music. “We have a strong team that is action-oriented because everybody is so mission-oriented,” said Camille Delaney-McNeil, the OrchKids program director. It took just a few weeks for the OrchKids team to totally revamp their curriculum to full-fledged online instruction.

Most of their teachers had never done online music lessons, nor had most students. Staff had to provide informational support to help everyone connect online from their own homes, where all were sheltering-in-place. Music organizations began offering links to resources that could help with this new style of teaching. In addition to tips for tweaking the settings on online apps to make music sound better, there was advice from veteran online instructors that for very young students, it helps to have a parent or other adult sit in with the child during a virtual lesson.

The transition was especially difficult because many students’ families didn’t have consistent access to the basics required for online instruction: Internet coverage and a device to communicate with. Even more challenging, OrchKids’ instructional philosophy centers on group lessons and ensemble playing. So do the other free after school music programs that are part of El Sistema USA, an organization inspired by El Sistema, a music-education system developed in Venezuela more than 40 years ago that emphasizes ensemble playing right from the start. Online ensemble playing is impossible with today’s technology because there is a lag time in the transmission of sound between online devices. There’s no way musicians on either end of a connection can play or sing in sync. OrchKids and other El Sistema programs switched to a mixed approach—material for students to work on at home, some one-on-one online instruction, and online group get-togethers. They also found work-arounds for families that didn’t have the technology. A few commercial internet providers helped by offering free Wi-Fi in some areas during this crisis.

When Baltimore’s OrchKids program realized that local schools were about to close, they began researching options. Administrators sent a survey to students’ families to learn about their Wi-Fi and communication devices. “We solicited stakeholders in our community to donate tablets and phones for students who didn’t have them,” said Delaney-McNeil. Staff then reorganized the OrchKids schedule. Instead of students having group lessons four afternoons a week, each student would have one thirty-minute online private lesson a week. On the other three days, students work on assignments delivered to their cellphones, laptops, and tablets. OrchKids also made plans for how to organize virtual group get-togethers.

Soundscapes, an El Sistema program in Newport News, Virginia, switched from in-person group teaching to using music software to deliver music lessons to students to work on at home, if they have computers, laptops, or tablets. For those with only cellphones, Soundscapes posts a video of the lesson on a software program accessible by cellphones that students had been using in regular school. Soundscapes also holds small virtual group get-togethers. “The teacher can pose a question… and students can answer back in video. The teacher might say, ‘Please play these five measures,’ and each student will post their five measures. Everyone can hear everyone else’s submission. It allows them to stay connected a little more,” explained Reynaldo Ramirez, program director for Soundscapes. He realizes that it won’t be possible to connect online with all their students. “I have two staff members calling parents, trying to get them to the technology. The elementary school where we did our afterschool program has more than seven hundred students, a huge Title 1 school. They had only a hundred Chrome books that some students were able to check out when schools closed.” Even so, by mid-April “we have 68% of our eligible students enrolled in our virtual program.”

Enriching Lives Through Music, an El Sistema program serving a largely immigrant community in San Rafael, California, also has online access problems for some students. The program has held Zoom get-togethers for older students, but its main effort has been posting lessons for students to work on at home. If families can’t connect, a teacher sends a text message to a family member’s cellphone with a link to a video of the lesson on YouTube. If that doesn’t work, “we’re getting together packets that we can provide at our office site that families can go and pick up,” said brass and woodwinds teacher, Matt Boyles. “One colleague is also mailing personal notes to her younger students that she knows aren’t comfortable using technology, sending them music to share. We’ve heard that siblings are playing music together. So we’re sending songs siblings can play together, along with music that the rest of the family can join in and sing. That way there can be an uplifting event within the household of people making music together.”

Enriching Lives Through Music students’ public schools closed so suddenly that some didn’t have a chance to bring home their instruments, which are usually stored at school. The program’s cello teacher managed to retrieve the instruments so parents could come, one at a time, to pick them up. She also tunes instruments for families. A parent can come into a waiting room at the program’s office and drop off the instrument. The teacher takes it into a different room to tune it, and then brings it back to the waiting room.

An OrchKids cello student having an online lesson at home, using a laptop. Photo credit: Courtesy Angelique N. Kane

An OrchKids cello student having an online lesson at home, using a laptop. Photo credit: Courtesy Angelique N. KaneFor OrchKids students who weren’t able to bring their instruments home, the program posts general music lessons for them to work on at home, on music theory or musicianship. One who couldn’t retrieve his flute has a piano at home and wanted to learn to play it. An OrchKids teacher is giving him online help with piano, an instrument OrchKids doesn’t usually teach.

Camille Delaney-McNeil is looking forward to a return to in-person teaching, but she has found benefits to this experiment with virtual learning. OrchKids might continue sending online lessons to students to offer “quality practice options over weekends,” she explained. She feels it might also be good to keep the option of having one-on-one online lessons for some students after in-person teaching resumes. “Normally our students are in group classes. But at some point in your development, you need one-on-one attention.”

Jane Kramer, executive director of Enriching Lives Through Music, noted another benefit of the online adventure. “We are distance sharing with kids in our community now. That opens up the possibility of distance sharing with kids in programs all over the country,” she said. Her organization has links to programs in other regions. “One of our teachers is eager to create something we can use between our programs, a song that we can all learn and share,” Kramer said. “Once we get a comfort level with the technology, the opportunities for that kind of sharing are unlimited.”

Another positive outcome of this crisis could be how it shows inequity between institutions. News reports highlight the lack of access to online learning tools for many children, not only in music programs but in regular schools. Lessons learned from this terrible crisis may lead to a much-needed national conversation on how to make online resources available for all students going forward.

Featured Image Credit: courtesy of s tudents from two El Sistema USA programs

The post How after school music programs have adapted to online music playing appeared first on OUPblog.

June 1, 2020

Eight books that make you think about how you treat the earth

The foods we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the climate that makes our planet livable all comes from nature. Yet, most that live here treat our planet superfluously, rather than something to be admired. During this COVID-19 pandemic, nature seems to be sending us a message: To care for ourselves we must care for nature. It’s time to take notice. This week we celebrate World Environment Day. We have compiled a list of important books that explore political issues related to the environment.

Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change by Joan FitzgeraldCollectively, cities take up a relatively tiny amount of land on the earth, yet emit 72% of greenhouse gas emissions. Clearly, cities need to be at the center of any broad effort to reduce climate change. This book argues that too many cities are only implementing random acts of greenness that will do little to address the climate crisis. Fitzgerald has a solution. Read a chapter hereClimate Change and the Nation State by Anatol Lieven

The climate emergency is intensifying, while international responses continue to falter. Lieven outlines a revolutionary approach grounded in realist thinking. This involves redefining climate change as an existential threat to nation states – which it is – and mobilizing both national security elites and mass nationalism. Learn more here.Why Good People do Bad Environmental Things by Elizabeth DeSombre

No one sets out to intentionally cause environmental problems. All things being equal, we are happy to protect environmental resources; in fact, we tend to prefer our air cleaner and our species protected. But despite not wanting to create environmental problems, we all do so regularly in the course of living our everyday lives. Why do we behave in ways that cause environmental harm? Read a chapter here.Beyond Greenwash by Hamish Van der Ven

When eco-labels are credible, they can lead to dramatic change in environmental practices broadly and quickly by leveraging the purchasing power of corporate to influence global supply chains. But despite the existence of established practices for eco-labeling, many labels remain little more than superficial exercises in “greenwash.” How can consumers separate greenwash from genuine attempts to address environmental challenges? Read a chapter here.The Politics of Anthropocene by John S. Dryzek and Jonathan Pickering

This book, winner of the 2019 Clay Morgan Award Committee for Best Book in Environmental Political Theory, envisages a world in which humans are no longer estranged from the Earth system but engage with it in a more productive relationship. We can still pursue democracy, social justice, and sustainability – but not as before. Read a chapter here.A Good Life on a Finite Earth by Daniel J. Fiorino

Over the last decade, the concept of green growth has become central to global and national debates and policy due to the financial crisis and climate change. Will a strategy of unguided growth above all cause ecological catastrophe? Read a chapter here.Food Citizenship by Ray A. Goldberg

Over the last decade, the concept of green growth has become central to global and national debates and policy due to the financial crisis and climate change. Will a strategy of unguided growth above all cause ecological catastrophe? Read a chapter here.Governing the Rainforest by Eve Bratman

Looks at development and conservation efforts in the Brazilian Amazon, where the government and corporate interests bump up against those of environmentalists and local populations. It asks why sustainable development continues to be such a powerful and influential idea in the region, and what impact it has had on various political and economic interests and geographic areas. Read a chapter here.World Environment Day offers a global platform for inspiring positive change. We recognize that global change requires a global community. Global change requires people to think about the way they consume, for businesses to develop greener models, for farmers and manufacturers to produce more sustainably, for governments to safeguard wild spaces, and for youth to become fierce gatekeepers of a green future. It requires all of us.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Sebastian Unrau on Unsplash

The post Eight books that make you think about how you treat the earth appeared first on OUPblog.

May 31, 2020

Why recognizing different ethnic groups is good for peace

In a time of global crisis that has reproduced many inequalities and reinforced mistrust across lines of identity in diverse societies, one may easily succumb to a sense that meaningful redress and social cohesion are impossible. But, learning from contexts of large scale violence and civil war, there’s reason to believe that “recognition” based strategies can help diverse societies overcome the legacies of their painful histories.

By recognition, we mean explicit reference to ethnic identities in constitutions, peace agreements, or legislation. This may be done for symbolic reasons or come with group-based rights like quotas or autonomy arrangements. For example, after mass violence through the 1970s and 1980s, Ethiopia’s post-war constitution granted group-specific rights to “every Nation, Nationality and People in Ethiopia.” Whether or not to structure state institutions in a way that recognizes different ethnic identities is a long-debated question among both scholars of conflict management and political philosophers, as well as leaders and other peacebuilders grappling with post-conflict institutions the world over.

Having worked in contexts where both recognition (in Rwanda, historically) and non-recognition (in Burundi, historically) preceded large-scale violence, we began research on ethnic recognition without necessarily favoring it as a strategy and open as to what we might find.

We studied all violent conflicts that ended between 1990 and 2012 and found that governments around the world are split: 40% of post-conflict agreements and constitutions involve some form of ethnic recognition, whereas 60% do not. This classification contrasts recognition in cases like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ethiopia, and Iraq with non-recognition in cases such as Kenya, Liberia, and Turkey. In all these cases, ethnic identity was an important political cleavage and yet governments have chosen different approaches to addressing diversity in the aftermath of violence.

What explains these differences? Recognition can allow a group to feel assured that it has a place in the state and is not being shortchanged. On the other hand, it can facilitate or even license political mobilization on ethnic lines. How these effects play out depends on whether the country is led by a leader from the largest ethnic group or not. . If the majority ethnic group is in charge, recognizing minority ethic groups improves outcomes. If the minority ethnic group is in charge, recognizing different ethnic groups doesn’t improve a country’s prospects for peace or political stability.

Informed by this analysis, we set about documenting the extent to which recognition was used, understanding the conditions under which it arises, and on the basis of all of that, assessing to what extent it may help societies to reduce the potential for future violence.

The results spoke rather clearly. We find promise in recognition. On average, countries that adopt recognition go on to experience less violence, more economic vitality, and more inclusive politics than those that do not recognize ethnic identities.

Looking more closely, these effects are driven by cases in which ethnicity was especially important in the conflict and where a leader from the largest ethnic group was in charge after the violence. When minority group leaders rule, there’s no clear indication of the benefits of recognition.

Burundi, Rwanda, and Ethiopia suggest that paradoxical effects abound. Burundi’s recognition-based 2005 constitution uses extensive ethnic quotas, but the result is that ethnic differences matter less in defining the country’s political coalitions. In contrast, Rwanda’s non-recognition-based 2003 constitution aims to “eradicate” ethnicity, but deep mistrust persists between ethnic groups. In Ethiopia, the minority Tigray-led regime used recognition as a strategy to bring together enough ethnic groups to overthrow the ancien regime. Ethnic identities and mistrust have remained politically salient, but it is difficult to imagine that these ethnic factions would have worked together in the absence of recognition.

Amidst alarming news of rising xenophobia and intergroup disparity, these findings suggest a pathway from despair. It appears that recognizing and affirming different ethnic groups and their interests could help countries improve trust and reduce conflict.

Featured Image Credit: Ethiopia Grunge Flag via freestock.ca

The post Why recognizing different ethnic groups is good for peace appeared first on OUPblog.

May 30, 2020

Moving beyond toxic masculinity: a Q&A with Ronald Levant

In 2018, the American Psychological Association released its first ever Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men. At the time of the release, these guidelines were met with criticism by some who viewed them as pathologizing masculinity, but since the guidelines were released the discussion of “toxic masculinity” has spread to all areas of our society and culture. Ronald F. Levant has served as president of American Psychological Association as well as president of the association’s Society for the Psychological Study of Men and Masculinities. Levant has been a leader in the research on the psychology of men. We spoke with him about how traditional masculinity ideology is conceptualized by psychologists, how it plays out in our society, and why it’s important from a psychological standpoint to move beyond the concept of toxic masculinity.

Sarah Butcher: You observe that the feminist movement opened up more options for girls and women to express their identity but that there was no corresponding movement for men. Why do you think that is?

Ronald Levant: In the 1960’s amid the civil rights and LGBTQ movements, women decided once again (think of the suffrage movement) to address their oppression. The result is what is called second wave feminism. Over the 70s to the 90s many men felt defensive in the face of women’s newfound assertiveness, resulting in what was then called a masculinity crisis (think Bridges over Madison County). This led to several different types of movements. One that gained prominence was the mythopoetic movement (remember Robert Bly and Iron John?), which did help some men become more comfortable with their emotions but was also was suffused with misogyny. Others like the Promise Keepers and the Men’s Rights Organization were even more blatantly misogynistic. What we advocate is a movement that is inspired by the ideals of gender equality, one that would help men ditch the burdens of dominance, and teach men that they can be men without the trappings of masculinity.

SB: You coined the term Traditional Masculinity Ideology—how do you define it, and how do you see it playing out in the lives of men?

RL: The most current definition is the holistic set of beliefs about how boys and men should, and should not, think, feel and behave. As far as current research is concerned, we’re typically looking at seven sets of prescriptive and proscriptive norms–avoidance of femininity; negativity toward sexual minorities; self-reliance through mechanical skills, toughness, dominance, importance of sex, and restrictive emotionality.

SB: Do you see any biological component to masculinity, or is it entirely socially constructed?

RL: There may be a biological basis to masculinity, but I am not aware of any solid support for this proposition. More importantly, we are psychologists not biologists, and we study masculinity as a social and psychological phenomenon.

SB: In recent decades, men have begun shouldering more of the burden of domestic labor and childrearing (although far from an equal share). Why does that pose a challenge to traditional masculinity ideology?

RL: Good questions. It poses a challenge to traditional masculinity ideology because it violates the avoid all things feminine norm, because childcare (and nurturance in general) is considered feminine.

SB: Research has shown that men have a harder time expressing (and even naming) their emotions. Why is that and what are the consequences for themselves and others?

RL: Decades ago, I noticed this in my work in the Boston University Fatherhood Project, and curiosity drove me to study the emotion socialization research literature in developmental psychology. Boys start out life more emotionally expressive than girls as neonates and retain this advantage over the first year of life, but from ages two to six—due to the childhood socialization of emotions, in which boys are made to feel ashamed of themselves for expressing vulnerable and caring emotions—many lose this expressive ability. This study formed the base for my normative male alexithymia hypothesis. “Alexithymia” means no words for emotions. My hypothesis is that socialization guided by traditional masculinity ideology, and in particular the norm of restrictive emotionality, produces a mild form of alexithymia in men, who cannot give a good account of their inner lives. This has enormous implications for relationships, stress management, and mental health. I later developed a treatment for such men called Alexithymia Reduction Treatment.

SB: As you argue, most violence is committed by men, yet most men aren’t violent. What is it that leads a minority of men to engage in violent behavior, and what role does traditional masculinity ideology play?

RL: This is a good question. The short answer is that we don’t know why some men are violent and others are not. Various theories have been proposed, with social-situational factors having more weight than personality factors. What we do know is:

The vast majority of boys and men are not violent.The vast majority of adult men do not endorse traditional masculinity ideology.There are literally 40 + years of research showing correlations between all of the masculinity scales and harmful outcomes, and many of these are related to violence.We think that the correlation is due to the boys and men who score at the very high end of these scales. Thus, high endorsement of or conformity to the norms of traditional masculinity is associated with rape myth acceptance, disdain for racial and sexual minorities, or aggression, for example.SB: What role does traditional masculinity ideology play in sexual violence, ranging from sexual harassment to rape?

RL: Based on the avoid femininity norm, boys prefer playing with other boys rather than girls, and thus rarely get to know girls as persons. In puberty boys become very interested in girls, but as sex objects. Objectifying women is at the very foundation of sexual violence.

SB: You also examine different versions of masculinity ideology such as African American masculinity and Latinx masculinity. How can the theory of intersectionality help us understand these different masculinities?

RL: The theory of intersectionality says that our overall identity and sense of self is a composite of a number of specific identities that may relate to our race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, age cohort, etc. So, for example, African American men have to fulfil the requirements of the male role (e.g., providing for one’s family) impeded by racism, which has reduced educational and employment opportunities for black men.

SB: What is the role of traditional masculinity in mental and physical health?

RL: Traditional masculinity ideology emphasizes toughness, self-reliance and never revealing vulnerability. In the areas of physical and mental health this translates into taking health risks, not seeking professional help when needed, and relying on alcohol for stress reduction.

SB: Based on your clinical experience, what are some of the most effective techniques for men who want to escape the prison of traditional masculinity ideology?

RL: The most effective techniques I have found is helping men who are unable to verbalize their emotions to learn how to do that, to open up their hearts to their families. This often involves first dealing with their fears that this will somehow emasculate them, strip them of their ‘man card,’ and along the way dealing with their sense of shame resulting from violating the male code.

SB: What role do fathers play in the propagation of traditional masculinity ideology, and what are some tips for fathers wishing to model a more gender-neutral approach?

RL: The “essential father hypothesis” posits that the father’s essential role is to model masculinity and heterosexuality for his sons. Although this idea has been largely discredited in academia it is still very prominent among the public. A better alternative is the involved father role, in which dads share parenting duties equally with their female partners.

Featured image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash.

The post Moving beyond toxic masculinity: a Q&A with Ronald Levant appeared first on OUPblog.

May 29, 2020

Should we fear death?

We are currently faced with a global crisis. A virus has spread to all parts of our planet, and thousands of people have died from the coronavirus. Many people now fear that they are going to be sick and die. Fear of sickness can certainly be rational. It is more questionable whether fear of death is so. Death is something we mourn or fear as the worst thing that could happen. And yet being dead is something that no one can experience and live to describe.

There is the process of dying, the incident of death, and the condition of “being dead.” The process of dying is familiar to all those who have died after a period of sickness. The incident of death is undoubtedly a mystery. No one now alive has ever experienced death, and when we are dead, we are no longer around to talk about it. All we know is that one day, we are going to die. Most religions presuppose that life continues in one form or another after death, and many people chose to believe in such an afterlife. But for secular people, questions concerning death are just as pressing. What is death without a god and an afterlife? Should we fear the end of our lives?

There are two main responses to the question of fear of death. First, some people follow the ancient philosopher Epicurus in thinking that death is not bad for us and that we, therefore, should not fear death. Epicurus argued that death is not prudentially bad for us because “as long as we exist, death is not with us; but when death comes, then we do not exist.” And the ancient philosopher Lucretius later added that both sides of our lives are filled with non-existence. And since we do not fear the eternity before we were born, we have correspondingly little reason to fear death.

The second response is offered by the majority of contemporary philosophers working on death. They disagree with Epicurus and Lucretius. Instead, these philosophers believe that death is somehow bad for the individual who dies. According to the deprivation account of the badness of death, death is bad in virtue of depriving the individual of a future life worth having. Most notably, Thomas Nagel argued that death can be bad for those who die when and because it deprives them of the good life they would have had if they had continued to live. This usually means that death is worse, the earlier it occurs. That is to say, the death of younger individuals is considered worse than the death of older citizens. This line of thinking is also reflected in a willingness to prioritize saving young lives over old ones in times of scarcity, as well as how deaths are evaluated in global health today.

Irrespective of which response you favor, there remains a question of how we should relate to the prospects of our own death. What reason do we have to care about the fact that we are going to die? We would like to consider a certain view of the self that has implications for how we should think about death.

Many people believe that we cease to exist when we die. This belief usually means that the story of our lives ends with our death. This pessimistic thought may lead us to think that, when we die, we lose everything. We lose our friends, our family, memories, our past, our future, and we lose the world in which we find ourselves, for all eternity. In addition, the world loses us. Such thoughts may give rise to existential terror.

But there is a less pessimistic path available to secular people. That is to say, your past is equally true, independently of whether you are alive or dead. Moreover, it is not necessarily true that your death represents the end of your existence. It depends on what we mean by “existence”. We can think about the self in narrative terms, as a story that gradually unfolds from the onset of our existence and to our biological death. We can also imagine that the story does not have to end when we die, but instead continues to unfold until it slowly and gradually ends. Insofar as the story continues after our death, it is possible to think of this as an afterlife in secular terms. This is not a new state of existence but is rather the continuation of the self in various relevant ways.

This notion of a secular afterlife presupposes that our biological death is not the end of our existence. Moreover, it presupposes a particular view about personal identity, similar to the version developed by Derek Parfit in his Reasons and Persons (1984). According to Parfit, personal identity is not what matters, but rather the survival of certain psychological capacities like memory, preferences, and emotions. Such a view would be able to accommodate various intuitions we have about posthumous interests and the moral importance of how we talk about and treat dead people.

There are several interesting questions worth exploring in connection with the secular afterlife. One is how it matters or should matter to us that we continue to exist after our death, and another is how it matters or should matter to others that we have a narrative afterlife in this sense.

Featured Image Credit: by Johannes Plenio via Unsplash

The post Should we fear death? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 27, 2020

Returning to the cutting edge: “sword” (Part 1)

Those who have read the posts on awl, ax(e), and adz(e) (March 11, 18, and 25, 2020) will find themselves on familiar ground: once again “origin unknown,” numerous hypotheses, and reference to migratory words. This is not surprising: people learn the names of tools and weapons from the speakers of neighboring nations (tribes), adapt, and domesticate them. Dozens of such names have roots in the remotest prehistory. Another complicating factor: the line separating tools from weapons is easy to cross. An ax, for example, can cut a tree and cleave a skull will equal ease. What once was a tool may become a deadly weapon.

Beating swords into plowshares, or say no to warmongers. Sculpture by Yevgeny Vuchetich, photo by Fuenping. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Beating swords into plowshares, or say no to warmongers. Sculpture by Yevgeny Vuchetich, photo by Fuenping. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.From Old Germanic three words for “sword” have come down to us. Two of them occurred in the fourth-century (CE) translation of the New Testament into Gothic. The verses with the word for “sword” are L 2. 35 and E 6. 17. In the King James Bible, they sound so: “(Ye, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul, also)” and: “…take the helmet of salvation and the sword to the Spirit, which is the word of God.” The Greek text has mákhaira and rhomphaía. Bishop Wulfila, who either translated the entire text or at least edited it, used hairus (pronounced as herrus) and meki (with ē, long e). The Greek for sword, memorable from Homer and Hesiod, is ‘áor, but, for some reason, it did not satisfy Wulfila.

When dictionaries cite glosses, such as “Gothic hairus translates Greek mákhaira,” they do not tell the complete story. In Classical Greek, the word meant “a knife used for human sacrifices (it was also used as a short-range weapon, that is, as a saber and a dagger); razor.” It came to mean “sword” only in New Testament Greek. Rhomphaía, at least in Classical Greek, designated a short Thracian sword with a long broad blade. One wonders what image the word evoked in the minds of the users of the Greek gospels and what exactly Gothic hairus and mekis meant.

The origin of both Gothic words is unknown, but it is amusing that, when we put side by side mákhaira, mekis, and hairus, the Germanic words look like echoes of the Greek one. Yet the similarity is accidental, because hairus has exact correspondences (cognates, congeners) in Old Icelandic, Old English, and Old Saxon, while meki is known even more widely. Also, Germanic speakers fought the Romans, not the Greeks and would have had no need to borrow Greek words. And of course, borrowings would have been much closer to their source.

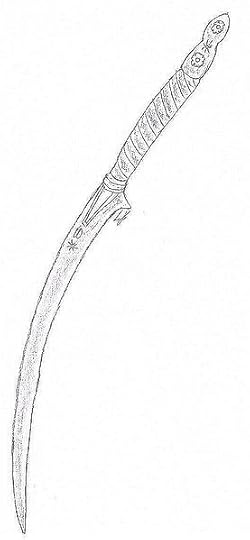

The bottom sword is a reconstruction of a mákhaira-type sword. Image by Janmad. CC-by-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The bottom sword is a reconstruction of a mákhaira-type sword. Image by Janmad. CC-by-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A cognate of meki showed up even on a runic inscription dated to approximately 250 CE, and the cognates of hairus occurred all over the Germanic-speaking world, but the Goths probably did not know a word like sword, while the rest of the Germanic world did. In the modern languages, only Icelandic has retained a reflex (continuation) cognate with hairus, while meki or maki– died without issue. However, its close relatives have been recorded in a Caucasian language and in the Slavic-speaking world (for example, Russian mech). Were swords bearing this name forged in the Caucasus, became famous, and spread over most of Eurasia? Even if so, the word’s etymology remains a mystery. The same is true of hairus despite some ingenious conjectures on this subject.

An image of a rhomphaía. By MittlererWeg. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An image of a rhomphaía. By MittlererWeg. CC-by-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Sword is equally mysterious. If it is not a Germanic noun, but a so-called culture (migratory) word that traveled form land to land with soldiers, we have little chance of finding its ancient source. Attempts to trace it to a Germanic root have also been moderately successful. Let us note that from a historical point of view awl does not mean “piercer,” ax does not mean “cutter,” and so on. We have also seen that the same word may mean “knife; dagger; razor,” and then “sword.” By the way, the origin of knife is obscure, and the same holds for bodkin. In any case, sword need not have meant “piercer” or “cutter” and been an analog of razor, which is, raz(e) + –er.

Three approaches to the etymology of sword have been tried.

1. Perhaps, we are told, the word either migrated from afar or is a cognate of some very ancient word (compare Gothic meki and Old Slavic mech’). Not long ago, the Luvian (or Luwian) cuneiform word shi(h)ual “dagger” (here given in a grossly simplified English transcription) has been cited as a cognate of sword. Allegedly, the root of both means “sharp.” Something should perhaps be said about the phrase Luvian cuneiform. Cuneiform was a system of writing, invented in ancient Mesopotamia. The texts have been preserved on multiple clay tablets, and the “letters” were wedge-shaped marks (hence the name: Latin cuneus means “wedge”). Luvian (Luwian) was spoken in Mesopotamia and northern Syria. Those who think that cuneiform is something exotic and marginally significant should remember that Hittite texts were written (inscribed) in cuneiform and that the world-famous epic Gilgamesh was recorded on such tablets. I will skip the technical part of this hypothesis (it is too complicated, and there seem to be some phonetic difficulties in it), and as regards the conclusion, I prefer to remain uncommitted. One could have expected to find some Germanic words with this root and some traces of it between Mesopotamia and the regions inhabited by the ancestors of modern Germanic speakers, though the home of the Germanic peoples remains a matter of controversy. I also try to follow the “law” I once formulated for myself: the more complicated and ingenious an etymology, the smaller the chance that it is true.

2. One should look at other words meaning “sword” in the hope that light will come from that source. In an excellent old etymological dictionary, written by two Norwegian scholars, sword (or rather its ancient protoform swerðam-; ð = th in Engl. this) was compared with Greek ‘áor “sword,” mentioned above, on the assumption that the ancient root was (s)ver “to lift” or “to weigh along” (s in parentheses designates movable s, a mysterious volatile prefix often mentioned in this blog). This reconstruction presupposes that the sword in Greek and Germanic got its name because it hung from the fighter’s hip. Though shared by several eminent etymologists, this idea fails to convince. Could the ancient sword in two languages be called from such a secondary feature? A weapon from a baldric, as it were?

The sword of Damocles: it certainly “weighs along,” but not from the hip! Image: The Sword of Damocles by Giuseppe Piattoli. Public domain via The Met.

The sword of Damocles: it certainly “weighs along,” but not from the hip! Image: The Sword of Damocles by Giuseppe Piattoli. Public domain via The Met.3. Perhaps the solution is less convoluted. Are there any Germanic words that sound like sword and provide a clue? Yes, indeed, but whether they conceal the desired “clue” is far from obvious. Though I believe that one guess is promising, here I am in the minority. Anyway, wait until next week.

To be continued.

Feature image credit: Ancient Assyria Divided into Syria, Mesopotamia, Babylonia, and Assyria by Philippe de La Rue. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Returning to the cutting edge: “sword” (Part 1) appeared first on OUPblog.

How ancient Christians responded to pandemics

Ancient Christians knew epidemics all too well. They lived in a world with constant contagion, no vaccines, medieval medical practices, and no understanding of basic microbiology. Hygiene was horrendous, sanitation sickening. People shared “toilette paper”(a sponge-on-a-stick). Besides that, in the second and the third centuries CE, two pandemics rocked the Roman World. The first, the so-called Antonine Plague, was perhaps a strain of smallpox that, with intermittent outbreaks, persisted for decades (ca. 165-189 CE). It was said that in Rome, a city of roughly a million people, 2,000 often died a day. Those who could, practiced social distancing by retreating to the countryside. Those who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, escape were instructed by doctors to fill their nostrils and ears with sweet-smelling perfume and herbs, which would expel the polluted air. If only it were that easy. Across the Roman world, the usual rhythms of life were interrupted as people fled—or died. Tax revenues dried up. Building projects broke off midway. The economy froze.

The second pandemic, two generations later, was perhaps worse. Thought to have been a filovirus — a zoonotic pathogen causing hemorrhagic fevers (think Ebola) — one source records that in Rome and in cities of Greece up to 5,000 men died a day. This Plague of Cyprian, named after the Christian bishop who witnessed and wrote about it, lasted for over a decade (ca. 249-262 CE). It must have felt like an eternity. The empire, according to one historian, never fully recovered.

In both pandemics, Christians were afflicted like everyone else. But based on the writings that have come down to us, their responses were largely defensive.

For people in antiquity, public health was an extension of religion. Honoring the Roman gods was a duty that ensured stability in the natural world. Even if Christians usually abstained from worshipping Roman gods, generally everyone got along. But when a plague erupted, Christians then appeared — to some — as irreverent, irresponsible, and more threatening to all. It seemed like Christians didn’t care about their civic duty.

At best, the result was social and political wrangling over the cause of, and response to, the plagues. In the face of such relentless mortality, tensions were high. People looked for answers, cast blame, and scapegoated. At worst, Christians could be easy targets. Christians cause calamities because they do not worship the Roman gods, the accusation went. Local persecutions sometimes followed.

Christian apologists responded in kind. No, they countered, you worship demons. And it’s because you don’t worship our God that we all suffer from the pestilence. Tertullian of Carthage even argued that the human race has always deserved the malice of God anyway, but actually the disasters now are lighter than in previous ages, thanks in part to Christians — God’s gift to the world. To blame Christians, Tertullian said, is counterproductive. In the midst of the third-century pandemic, Cyprian bishop of Carthage touted apocalyptic explanations. Well, the earth is old. It’s declining, Cyprian reprimanded the governor of Africa. Plus, this is the sentence that God has passed on the world: that evils should be multiplied in the last times. Judgment day is near. The plagues are God’s stripes and scourges. So stop your superstitious nonsense and worship the one true God, says Cyprian, before it’s too late.

For some Christians, though, the pandemic raised doubts. Despite Cyprian’s own ideas about the true cause of the plague, it was disturbing that believers died just like nonbelievers. How can that be, they asked, especially if the ‘heathen’ don’t worship God? Unfortunately, Cyprian tried to console them, while we are here in this world, everyone will be equally afflicted—Christians more so since they are already weakened by fasting. But Cyprian, apparently, was not completely callous. His biographer Pontius says the bishop instructed his churches to care for the sick — whether Christian or not. Some surely did.

Others were less sympathetic. During the same pandemic, bishop Dionysius of Alexandria circulated a letter among Egypt’s brethren, boasting about how Christians were caring for fellow Christians, even though they also became infected. Many then died. Such a fate was second only to martyrdom, he said. By contrast, Dionysius claimed, the heathen (literally, “gentiles”) were heartless, casting the sick into the roads half-dead and leaving their corpses to rot. Whether the Christians in Alexandria ever thought to nurse the heathen as well as the brethren, Dionysius doesn’t say.

He probably didn’t care. If he needed to, he could justify stepping over the sick heathen dying on the street (Matthew 10:5-8). He had it out for them already. Earlier he had been forced to flee to the desert for his refusal to worship their gods.

Dionysius was a partisan. And to what extent Christians actively sought to care for nonbelievers during the pandemics is unclear. Outside of Matthew 5:43-48 and Luke 6:27-36, the blueprint from Christian scripture is ambiguous. In the gospel of Mark, Jesus is known for curing his own people (Mark 1:29-45; 2:1-12; 5:24-34). Healing one gentile woman was the exception (Mark 7: 24-30; Matthew 15: 21-28). In the gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells his disciples to not heal the sick among the gentiles (Matthew 10:5-6; compare Luke 9:1-6), whereas in the gospel of Luke, Jesus is much more open to healing gentiles (Luke 7:1-10; 10:25-37).

If anything, Dionysius’s report weakens a common narrative today: Because Christians cared for their sick — as well as perhaps the pagans, too — outsiders noticed and converted. And in the long run, the two pandemics helped spread Christianity in the Empire. In Africa, at least, the opposite seems to have been true. Cyprian vents his frustration to the governor because people don’t convert when they should.

On balance, Christians would have had various responses to the pandemics, running the gamut from self-preservation to self-sacrifice — responses not too different from their non-Christian neighbors.’ In such crises, each group turned to their god(s) for help. We can only wonder what their responses would have been if we could tell them that such a massive scale of death was due to submicroscopic particles of RNA or DNA, coated with protein and capable of self-replication within the cells of an organism, where its effects are often pathogenic — in short, if we could tell them that it was a virus. Maybe instead of being at each other’s throats they would have shown more solidarity.

Featured Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The post How ancient Christians responded to pandemics appeared first on OUPblog.

May 25, 2020

How conspiracy theories hurt vaccination numbers

Near the end of 2018, data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that a small, but growing, number of children in the United States were not getting recommended vaccinations. One in 77 infants born in 2017 did not receive any vaccination. That’s more than four times as many unvaccinated children as the country had at the turn of the century. Some of this may be due to lack of access to vaccines; populations without insurance and those living in rural areas have greater rates of nonvaccination. But part of it is also likely due to the rise of conspiracy theories and the willful dismissal of scientific evidence when it comes to vaccines.

Vaccinations have always provoked anxiety. But the data on vaccines that are in widespread use are now clear: vaccines are safe and save lives. Nonetheless, conspiracism insists that we don’t know all the facts, that things about vaccines are not as they seem. Conspiracism fuels the anti-vaccine movement, nudging people to accept anecdotes (e.g., “I heard about one child who got a measles vaccine and developed autism”) over statistics.

And, with the unpredictability of political leaders’ words and actions, we are one menacing sentence away from real public health trouble. Imagine if a president one day were to announce, “People are saying that maybe we don’t really need quite so many vaccines for our kids. After all, look at all this autism that’s around.” This vague conspiratorial phrasing—people are saying—this kind of innuendo, would immediately corrode confidence in our collective public health policy. Conspiracism undermines authority.

Conspiracists question the safety of vaccines not just because of distrust of the pharmaceutical industry, but because they tend to question the function of government itself. For them, vaccination policy raises questions about the scope and intentions of federal power. The growing avoidance of vaccination seems to reflect interlocking anxieties about media, science, and government. Yet no matter how passionately the conspiracists make their case, it remains true that universal vaccination is in our common interest. Unlike conspiracists, public health adheres to standards of evidence and falsifiability. When conspiracists disregard explanation and refuse any form of correction, they place health at risk.

Featured Image Credit: by PhotoLizM via Pixabay

The post How conspiracy theories hurt vaccination numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers