Oxford University Press's Blog, page 151

April 30, 2020

The ethics of defeating COVID-19

Isolation, quarantine, cordon sanitaire, shelter in place, physical distancing. These were unfamiliar words just a few weeks ago. Now, your life and the lives of many others may depend on them.

Isolation is the separation of someone who has been identified as ill so that she cannot spread the disease to others. Isolation requires careful management to keep the infection inside the area in which the patient is kept. Today’s hospitals accomplish isolation by prohibiting visitors, using protective equipment, and creating negative pressure rooms to prevent airborne spread.

Isolation can be very lonely, as many patients and families learned to their sorrow when patients became ill in the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington. People in isolation may die alone, without contact with their loved ones, frightened, and unable to be comforted by the familiar. Caregivers dressed in protective garb will appear alien. Yet strict adherence to protocols is needed to prevent spread.

Quarantine separates people believed to have been exposed to a contagious disease. The term stems from the practice in Venice during the plague years: ships were made to stay offshore for forty days before landing to ensure that they did not carry pestilence. While quarantine may be effective in preventing the spread of illness from ship to shore, it augments risks to those who remain on board, exposed to infected shipmates.

People who have been exposed to COVID-19 and self-quarantine at home don’t put the public at risk but may increase risks to their roommates or family members who will also be in quarantine. Quarantine, strictly enforced, prevents disease spread of from those in quarantine to those outside. However, it will have no impact on disease that has already become established in a community, unless ill community members can be identified and isolated and all of their contacts put in quarantine. And group quarantine presents significant issues of justice: the still-well are put at greater risk to save the rest of us.

The cordon sanitaire draws a ring around a geographical area, as China did with Wuhan: People weren’t allowed to go out or come in. This strategy doesn’t prevent illness spread within the affected area. It is only effective if it’s strictly enforced: if one ill person escapes, the strategy will fail. The strategy also assumes the illness is not already outside the cordon’s boundaries.

A cordon sanitaire prevents people from leaving who might otherwise have been able to protect themselves by getting away. To be sure, these people are likely to be among the more privileged, with the ability to travel and a place to go. Cordon sanitaire may prevent essential supplies from entering the roped-off area, a particular burden to the less well off. It will prevent loved ones from coming to visit family members. Stopping transit bringing disease has great costs that may not be fairly distributed.

Physical distancing requires staying away from people—supposedly six feet away for COVID-19. Distancing is less effective than other strategies in preventing pandemic spread. People may be put at risk if other insist on getting close or do so carelessly. And distancing does little to protect from fomites, virus deposits that remain on surfaces such as stair railings, doorknobs, cereal boxes at the grocery store, or gasoline pumps.

Distancing also is hard. Social and emotional isolation can be psychologically difficult for some people. Closing normal places of social congregation, from restaurants and bars to mosques and churches, may seriously patterns of life and wreak economic havoc.

Contact tracing, much used to control the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, can violate personal privacy. Contact tracing is difficult enough for intimate personal relationships; it is nearly impossible to conduct exhaustively in a vast pandemic. If we can identify discrete cases and then trace contacts, we could use far more fine-tuned methods for effective control. South Korea may have managed this, but it is too little too late elsewhere.

Sheltering in place is a euphemism for staying at home. Its effects are limited if illness is already widespread. Essential workers will remain at risk doing their jobs; other workers will lose their jobs. Parents may be stressed with additional childcare and child-education responsibilities if they are also trying to work from home, while kids themselves are cut off from physical contact with their friends.

Sheltering in place has harsh consequences for education, childcare, and employment in industries that cannot go online. Sheltering in place is often assumed to be the only strategy we have so that hospitals are not overwhelmed by a surge of very sick patients, but the practical and ethical costs of sheltering in place can be immense. We can pay people to stay home with effective sick leave, but we can’t re-create jobs that are ended, businesses that go bankrupt, or lives that are lost.

All of these strategies have been used in ancient, medieval, and early modern historical times, when there were no tests, no vaccines, and no effective treatment available. We can avoid unnecessary reliance on these methods, however, if only we are willing and able to test in time.

Extensive testing is already being put into effect in limited but promising ways. The northern Italian village of Vò tested all 3,000 inhabitants, using quarantine for those who tested positive. This made it possible to stop the spread of the coronavirus in under 14 days. The strategy required a complete cordon sanitaire of this mountain town and was successful because when it was implemented only 3% of the population had disease. Seattle, Washington, is conducting a SCAN study of a population sample to trace the spread of COVID-19. Testing is constantly improving, too, with results now available in a matter of minutes or hours.

New testing methods may allow us to avoid many of the inequities and injustices of the traditional methods of pandemic control, if we can get them deployed sufficiently quickly and effectively. We wouldn’t need to isolate people unless it was clear that they actually have the virus. A contemporary cordon sanitaire could be permeable, allowing people who test negative to come and go through the barrier. Quarantine that confines people who are not ill with those who are, thus incubating further spread, would be obsolete; only true positives, whether on a cruise ship or in a nursing home, would need to undergo quarantine. And sheltering in place? It wouldn’t be necessary either, unless, as in the current COVID-19 pandemic, the disease had already moved far beyond our capacity to contain it.

At the moment, many parts of the world without adequate testing or treatment are forced to rely primarily on strategies from earlier eras or use those strategies in conjunction with whatever testing capacities are available. Once an outbreak has become widespread, effective case identification and contact tracing become increasingly difficult. Lack of adequate public health resources complicates these difficulties. As we develop more adequate testing, we may be able to move away from primary reliance on forms of pandemic control that cause significant harm or use those earlier forms more judiciously in conjunction with testing. If we’re going to continue to use them—quarantine, isolation, cordon sanitaire, contact tracing, and massive lockdown measures including confinement to home—we need to be alert to the ethical challenges they raise.

Ethics look different with infectious disease as the central paradigm: All of us are potential victims and vectors to one another. COVID-19 has reminded us of the power of this paradigm: we must assess how we deal with this pandemic, and for the next one, in light of our shared vulnerabilities.

Featured Image Credit: by athree23 via Pixabay

The post The ethics of defeating COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 29, 2020

Spelling reform: not a “lafing” matter

I keep receiving letters explaining to me the futility of all efforts to reform English spelling and even extolling the virtues of the present system. I will spend minimal time while rehashing what has been said many times and come to the point as soon as possible. The seemingly weighty but not serious objections are three. 1) If we reform spelling, we’ll lose a lot of historical information. Quite true, but spelling is not a springboard to an advanced course on etymology. Agreed: if we begin to write nock instead of knock, a piece of history will be lost. I’ll say: good riddance (we don’t pronounce k-nock anyway, and no one sheds tears over the loss of a precious consonant). Besides, modern spelling often distorts, rather than reflects history. 2) People will never agree to reform modern spelling. Let us wait and see. In every society, there are people who will oppose any change. This is a fact of life, and we have to live with it. 3) Spellcheckers make Spelling Reform unnecessary. This objection looks plausible, but children all over the world still spend countless hours in fighting the horrors of English spelling, arguably the least natural in the Western world. By the way, this fight comes with a price tag, and the tag is huge.

Learning English spelling: spending or wasting their time? Image via pxfuel.

Learning English spelling: spending or wasting their time? Image via pxfuel.Now let us look at some substantive problems. The ideal—to emulate the Finnish model (write what you hear)—is unachievable for Present Day English, and this is fine: there is no need to hitch our wagon to such a distant star. Yet some changes would be almost painless. For example, in word-initial position, the letter c after consonants is easy to replace by k. If we are happy with ski, skate, skillet, skill, and skull, we can probably live with scamper, scan, scarf, score, and others like them spelled with sk-. By the way, score, scoop, scone, and many other sc-words are not of Romance origin, while scamp, though related to camp, reached English from Dutch. Consequently, the difference between sk– and sc– in Modern English words is not a safe clue to their origin. The choice—sk or sc—is governed by neither history nor logic. Why then do we need it?

Some double letters are another nuisance. This is especially true of foreign words like immune, pollute, and many prefixed forms beginning with af-: affect, affinity, affluent, suffuse, and their likes; afford (English, but made to look French with its aff-) will also be fine with one f. Does anyone think that a cesspool will smell worse with one s in the first syllable or that giraffes will lose an inch of their height if their English name emerges as giraf? (Compare: French giraffe, Italian giraffa, Spanish girafa, and Portuguese girafa!). Americans spell traveled but controlled—a useless headache. Let me reiterate my principle: remove the letters whose disappearance no one will notice or rue.

And this is where we encounter real difficulties. I am all for spelling knock, knick-knack, knob, and knife without initial k-. Knife is especially ridiculous. Its Old English form began with cn– (at that time, the letter k did not exist in English—so much for the etymological principle in today’s spelling!); its Scandinavian cognate began with hn-, while the distant origin of the word is unknown! Gnash and gnarl are equally odd relics of the past. But the phonetic principle is not the only one in determining how to spell modern words. It would be good to respell knack and gnash, but not know, and that for two reasons.

Another principle to consider when we try to reform spelling is the morphological one. It so happens that alongside of know and knowledge we have the word acknowledge. The letter c in it is confusing and redundant, as it is in all such words (acquire, acquaint, and so forth), but k in acknowledge designates a real sound, and it is advisable not to sever the ties between know and acknowledge. Still a third principle of orthography is iconic. If we respell know as now, this word will become a homograph of the adverb now, an unwelcome consequence of excessive rigor. Thus, in my opinion, “tarring all words with the same brush” for the sake of consistency would be a wrong procedure in reforming Modern English spelling. A similar case is the group gn-. Gnaw and gnarl should probably lose g-, and the same holds for the rare and isolated deign, but not for benign, sign, and design because of benignant, signature, and designation.

Tarred with the same brush—not a model for Spelling Reform. Photo by Mateja Lemic from Pexels.

Tarred with the same brush—not a model for Spelling Reform. Photo by Mateja Lemic from Pexels.Many other cases also require an individual approach. One of the hardest is the group gh. Ghost and ghoul should continue to do mischief without their h after g, while ghetto and gherkin should remain intact (ge– is already bad enough in get). The final group gh is comparatively easy to deal with, but here the change, if instituted, will be noticeable and hence controversial. In American English, though has occasionally been spelled as tho’ for more than a century, and plough has the legitimate spelling double plow. Through respelled as thru will inconvenience no one. A less obvious case is cough, enough, rough, tough, and their likes, as opposed to bough and dough, to say nothing of slough “muddy ground” ~ slough “a snake’s skin.”. Since English tolerates forms like off, cliff, stuff, fluff, and cuff, I see no harm in accepting the spellings cof(f), enu(f), and tuf(f). Stuff and tough, off and cough rhyme pairwise; so why should they not be spelled alike?! The hardest words are bought, brought, sought, thought, and caught. I have no immediately acceptable solution for them, but the existing spelling is counterintuitive.

A (k)nife of un(k)nown origin. Bronze knife via Picryl.

A (k)nife of un(k)nown origin. Bronze knife via Picryl.By way of conclusion, I may perhaps remind our readers how the odd spelling gh came into being. English once had a sound like German ch in ach. G pointed to its pronunciation in the back of the mouth, and h indicated its fricative character. Later, this ch underwent weakening, and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, such spellings as lauh, thoh, and dauhter (laugh, though, daughter) were recorded. The system of consonants reacted to this change in a curious way. It should never be forgotten that the sounds of language do not exist in isolation: they rather resemble spiders in a jar. The change to h meant that the consonant would disappear (English does not tolerate h in the middle of words), and this is what happened in the word daughter, to cite one example. But some of those ach’s did not want to die, and they saved themselves by jumping all over the mouth cavity to the protected space of the lips. In some dialects, buf and pluf (bough and plough) have continued into the present, and enough is a standard form. Compare enough and the rare enow or draught and draft! The history of these words in early Modern English was erratic, and there is no need for us to preserve its traces.

I needn’t say that the opinions expressed above are my own and do not represent the views of the English Spelling Society, despite my close association with it. I would be pleased to have them discussed, confirmed, or rebutted. I am also ready to continue in the same vein, should anyone express an interest.

Feature image credit: Three giraffes on a field, CC0 via Pikrepo.

The post Spelling reform: not a “lafing” matter appeared first on OUPblog.

G.E.M. Anscombe on the evil of demanding unconditional surrender in war

During military conflict, what are the constraints on the things that a warring nation may do to achieve their objectives? And what constraints are there on the objectives that such a nation should have in the first place?

A traditional answer to the first of these questions draws a sharp line at the deliberate killing of noncombatants. Though it has been affirmed by many great philosophers and theologians, this restriction was violated repeatedly during the Second World War, most notably in the nuclear annihilation of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While an overwhelming majority of Americans supported US President Harry Truman’s decision to bomb those cities in the days immediately after the bombs were dropped, public opinion today is sharply divided, with just over half of Americans thinking that the bombings were justified.

It was due to her conviction that the choice to bomb these cities made President Truman a murderer, that the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe gave a speech to her colleagues at the University of Oxford in June, 1956, attempting to convince them not to grant Truman an honorary doctorate. Anscombe was a Catholic convert and student of Ludwig Wittgenstein who then worked as a tutor at the all-women Somerville College. “If you do give this honor,” she asked rhetorically, “what Nero, what Genghis Khan, what Hitler, or what Stalin will not be honored in the future?” Despite her best efforts the motion failed badly, with only three or four other faculty joining her dissent.

Anscombe’s critique of Truman is most often remembered for her challenge to the “consequentialist” thesis that it is always possible in principle to justify an action by appeal to the balance of consequences in favor of it. But Anscombe herself argued that the consequentialist defense of Truman took for granted a further injustice, namely the Allied powers’ demand for unconditional surrender by the Japanese. “Given the conditions,” she wrote in her pamphlet “Mr Truman’s Degree,” an even greater number of civilian casualties “was probably what was averted by [Truman’s] action. But what were the conditions? The unlimited objective, the fixation on unconditional surrender.” It was this demand, Anscombe argued, that really was “the root of all evil.”

Anscombe had made a similar argument almost two decades earlier, in a pamphlet she wrote as an Oxford undergraduate that critiqued the decision to go to war with Nazi Germany. Citing Thomas Aquinas, Anscombe argued that “If a war is to be just, the warring state must intend only what is just, and the aim of the war must be to set right certain specific injustices. That is, the righting of wrong done must be a sufficient condition on which peace will be made.” By contrast, unconditional surrender does not aim to set right any specific injustice. Rather it says, lay down your arms and we will do what we want to you. In all likelihood, achieving such a demand will require going beyond the righting of specific wrongs. The demand for unconditional surrender leads in turn to unlimited war.

While Anscombe’s arguments against killing noncombatants are sometimes dismissed as inflexible or “high-minded,” in fact it is her position that best reflects the essentially political nature of military conflict. To see this, we should recall the German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s dictum: that war is politics by other means. Politics focuses on promoting and securing justice and the common good. Justice, in this context, is to give to others what they are due. And this is why there cannot be a just commitment to an unlimited end. When a warring nation declares such an end it is quite predictable that their adversary will not disarm in the way that is demanded. And when one’s adversary inevitably resists the unjust demand, it is always possible to blame them for what comes next. This is what the consequentialist justification comes to: If only the Japanese had done what Truman demanded of them, he would not have been required to bomb their cities.

Anscombe’s opposition to consequentialism is well known, but she did not attribute the decision to drop the atomic bombs simply to the acceptance of that doctrine. Rather, in her eyes the root cause of Truman’s unjust calculus was the unjust demand for unlimited victory. When we ignore the basic good of justice, we naturally embrace consequentialist reasoning, which can justify almost any decision. One justification for the attack on Iraq in 2003 was that the expected consequences of war and regime change would be better than living with the status quo. We now recognize that justification as flawed, but if Iraq becomes a stable democracy in a few years, expect the consequentialist justification to resurface. That’s the power of consequentialism. You can always find a set of effects over some period of time by which to justify a decision.

In war, and politics more generally, Anscombe instructs us to focus on justice. What needs to be set right? What do we owe each other? The obligations of justice mean we have to respect human rights and to negotiate. Military force is necessary only to rectify specific injustices and enable the negotiation of just settlements. Only limited war may be just.

Featured Image by WikiImages from Pixabay.

The post G.E.M. Anscombe on the evil of demanding unconditional surrender in war appeared first on OUPblog.

April 27, 2020

Denying climate change is hurting our health

In recent years, global environmental climate change has become a third rail in American culture, dividing us along political lines. The Republican party espouses a range of positions, from the denial of climate change (the earth is not getting warmer) to denial of our role in causing the problem (even if climate change exists, humans have nothing to do with it). Each of these positions amounts to inaction on climate change. The Democratic Party falls more in line with the science on this issue, which is largely settled. There is little disagreement among scientists that the earth is getting warmer. Hence, the political argument is not really about the science as much as it is about priorities. The Republican Party—in the past several decades a ceaselessly pro-market party—prioritizes deregulation and corporate interests over the potential disruption of these interests caused by the structural changes necessary to address climate change. The Democratic Party, for its part, has increasingly chosen to prioritize the future of the planet over the unfettered primacy of the markets.

Climate change happens slowly; its worst consequences may not affect us for generations to come. How, then, do we make the decision to take the politically difficult steps today to protect our world tomorrow?

This is where health can inform the conversation. We all value health. Our national health care spending is a testament to how much we are willing to invest in staying healthy. And make no mistake: climate change threatens health. The World Health Organization estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress. A 2018 paper shows that unmitigated climate change will result in up to 40,000 additional suicides across the United States and Mexico by 2050. In two decades, as a direct result of climate change, the number of natural disasters doubled from approximately 200 to 400 per year, with human costs rising commensurately. The 2017 hurricane season far exceeded any season in the preceding 30 years. The list goes on.

When we recognize that climate change matters for health, we open the door for health to become an organizing principle in addressing this issue. If we do not act on climate change, we are compromising our health. Perhaps we are fine with that. More likely, though, the vast majority of us are not fine with it, and if we properly weigh the impact of climate change on our health today and in the years to come, the politics of this issue would be very different.

Featured Image: Pixabay

The post Denying climate change is hurting our health appeared first on OUPblog.

How austerity measures hurt the COVID-19 response

The 2008 global financial crash brought with it a series of aftereffects that are shaping how different nations face the current pandemic. Austerity politics took a firm hold across Europe and other countries whose economies were hard hit, with governments and financial institutions arguing that they were an unavoidable consequence of the crash. While many corporations bailed out with public money recovered rapidly, public spending continued to be curtailed under the weight of public debt burdens. As unemployment soared, hundreds of thousands of people faced foreclosure and eviction. But austerity was not accepted quietly, it was met with mass mobilizations that demanded a reordering of political priorities to place the needs of ordinary citizens above those of elites. The outcomes of these movements are still unfolding, and their critiques are taking on new relevance as the world reels from the coronavirus pandemic.

In the United States, the Occupy Wall Street movement managed to engender a remarkable 400-plus “occupations” around the country. Although the movement ultimately waned, it established new connections that flowered in movements like Black Lives Matter and the Women’s Marches. The language of Occupy Wall Street, particularly its economic justice frame, also created a shift that destabilized the hegemony of TINA (There Is No Alternative) neoliberal discourse, paving the way for the grassroots fuelled Sanders and Warren campaigns, and for a new generation of young politicians representing marginalized communities in Congress. “Socialism” and the vision of a nurturant state that cared for its citizens began to make inroads into US political discourse, galvanizing a new generation to become politically engaged.

In other countries, like Spain, the 15-M movement had a much greater impact on institutional politics, ultimately leading to the creation of new municipal electoral alliances and new national political parties, like Podemos. These political parties and coalitions sought to translate the movements’ core demands to the institutional arena: an end to austerity and institutionalized corruption; a reinforcement of the social welfare state; and a progressive political agenda. As a result, municipal movements came to power in several of Spain’s major cities in 2015, demonstrating that progressive politics and social welfare provision were compatible with fiscal responsibility and reducing public debt. In 2020, Podemos entered government in the first coalition government of Spain’s post Franco democracy. This brings us to the second crisis, the global COVID-19 pandemic.

How has the 2008 global financial crisis and its after-effects conditioned this moment? The first clear effect is that states that pursued austerity politics and underfunded or privatized public health facilities find themselves unable to adequately deal with the burden caused by the pandemic. Austerity threw greater numbers of people into poverty. Data from the OECD and Credit Suisse shows that wealth inequality has increased significantly since 2008. The poor are the hardest hit by the pandemic, and the least able to practice social distancing and other protective measures, meaning that not only will more of them become infected and die, but this will further the virus’ spread.

In countries like the United States, whose health care provision is based heavily on direct fee and private healthcare, the pandemic has revealed the limitations of this model in a more powerful way than any social movement ever could, and the lessons it offers are tragic and profound. The perversity of states outbidding each other and competing with the federal government for ventilators at a time of national crisis exposes the absurdity of the current system and its unsustainability in times of crisis. The unviability of employer-based health care provision is exposed when mass unemployment meets global pandemic.

In the cold reality of this pandemic, progressive movements continue to push for a paradigm shift, and activists and politicians like Elizabeth Warren and Ayanna Pressly, highlight the matrix of racial and economic injustice that shape the unequal impact of the pandemic on communities. But they lack the institutional power to influence the response of the administration of Donald Trump administration, which is impervious to their demands. As the pandemic advances relentlessly, Trump advocates a scientifically unproven drug for COVID-19 that he has a financial interest in, and his chaotic administration demonstrates its ineptitude in the face of the greatest crisis in decades.

In Spain, we see a very different scenario. While austerity measures have crippled the fight against the virus and the economic consequences of the pandemic are already devastating, the government’s response has been radically different from the response to the previous crisis. The mobilization of the 15–M movement following the 2008 global crash not only paved the way for Podemos to enter government, but pushed the government to adopt a more progressive social welfare agenda. The government is proposing a series of social and economic protective measures, such as guaranteed utilities, 0% microcredits designed to protect the most vulnerable, and a form of Basic Income Support -not as a stop gap measure but as a permanent one- potentially significantly transforming the social welfare state. The deputy prime minister, Podemos’ Pablo Iglesias, defends these measures by invoking the lessons of the last crisis, in which austerity left the most vulnerable bearing the greatest costs.

He can win that argument thanks to the mobilization of the social movements that enabled the birth of Podemos and related municipal coalitions following the 2008 crash. Coronavirus will transform every society on earth in ways we can’t yet begin to imagine. How nations respond to this crisis will not be aleatory, but will depend in great measure on how they responded to the last one.

Featured image credit: Senior-4561704_1920 by Frantisek Krejci via Pixabay.

The post How austerity measures hurt the COVID-19 response appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2020

Six tips for teachers who see emotional abuse

The scars of emotional abuse are invisible, deep, and diverse; and unfortunately, emotional abuse likely impacts more students than we think.

Emotionally abusive behavior broadly consists of criticism, degradation, rejection, or threat. Emotional abuse (also known as psychological maltreatment or verbal assault) can happen anywhere, both within and outside of families, and can refer to a single severe incident or a chronic, ongoing pattern. Educators, caregivers, coaches, school mental health professionals, administrators, and peers are all capable of acting emotionally abusive toward school-age youth. That is part of its insidious invisibility; despite emotional abuse being highly involved in childhood abuse cases, it is often forgotten and overlooked. This type of interpersonal trauma is typically chronic and cuts deeply, as it is associated with mental and physical health issues (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress, sleep problems, self-harm) during the school years and beyond.

Even with this existing knowledge, emotional abuse remains misunderstood, minimized, unseen, and unreported by many, including school professionals. We outline three things teachers need to know about emotional abuse and three things they can do to meet the needs of students experiencing emotional abuse.

What to know

The impact on the student determines the occurrence of emotional abuse more than the behavior that caused it.

There is no legal or clinical universal definition of emotional abuse. For example, two students with a parent teasing them about their appearances may react differently, in part based on context and relationship with the parent. Emotional abuse would be determined by the impact on the student, rather than the teasing alone.

Emotional abuse is detrimental to both a student’s way of thinking and feeling.

Children create their sense of self from stories that others construct about them. Students may believe the destructive narratives that are told to them. That is, these harmful words may impact students at their core—shifting how they think about themselves and the world, and how they feel about themselves and others.

There are numerous ways that emotional abuse may manifest.

Emotional abuse is not simply hearing harmful words. The context around the experience of emotional abuse are varied and diverse. A student may internalize or externalize their behaviors, or something in between. If a school-aged youth is repeatedly told that she is worthless, then the student may be meek in class. If a student is threatened repeatedly, then she may act aggressively toward others.

What to do

Take care of your emotional needs and your emotional health.

Educators cannot support students if they cannot support themselves. As some students may constantly hear emotionally destructive words in their home environments, teachers certainly do not want to bring any semblance of that into their schools. Nevertheless, working with students can be tiring and frustrating. If their emotional energy is low, teachers may react rather than respond to difficult situations that unexpectedly arise. Rather than taking a breath, teachers might begin to punitively scold or admonish a student. Teachers need to take care of their emotional needs so that they do not parallel any unhealthy at-home behaviors in the classroom.

Foster sharing through strong relationships.

Try to examine the life contexts behind a student’s behaviors. Rather than focusing on what is wrong with students, be curious about the circumstances in students’ lives that may influence how they act in school. To have a firmer understanding, teachers need to create brave spaces in our schools and classrooms so that students may feel comfortable sharing with adults. Students often regard educators as more effective guardians in violence protection than police or security, which speaks to the importance of continuing to cultivate this trust. When students share feelings, provide positive reinforcement by expressing your gratitude or by giving a thoughtful, affirming response.

Know the laws around mandated reporting, and communicate with transparency.

Check state regulations and learn to whom to report and how to report within your district or county. If and when suspicion or reports of abuse arise, reach out to your school mental health professionals. Encourage your administrators to grow emotional abuse awareness, prevention, and intervention initiatives so that others feel willing to report even in instances of suspected abuse. Openly discuss what happens after a report is made, as this transparency allows for students to feel more comfortable with the idea of reporting.

Words are powerful, and as such, can be weaponized and wounding. Words can also be healing, spoken with gentleness and justice. Teachers should listen wholly to their students and their unstated needs; let teachers use their minds and words wisely and act knowingly.

Featured Image Credit: Image by Okan AKGÜL on Pixabay

The post Six tips for teachers who see emotional abuse appeared first on OUPblog.

April 23, 2020

The process of dying during a pandemic

The process of dying – what happens during those days, months, even years before we die – has changed a great deal in recent decades. We live longer than our parents and grandparents, we die for different reasons, we are less likely to die at home, we receive astonishing treatments, and our dying costs more. We should understand and prepare for that important time of our life.

Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has added its imprint on the end of life in a matter of weeks, not decades. It has or will touch nearly everyone in some manner. It has raised critical concerns about the allocation of resources threatens to disrupt established practices of respecting individual autonomy and decision-making, and may affect not only a person and their loved ones at the end of life, but also how that person is honored after death.

As COVID-19 spreads at a relentless pace, its threat to life has provided more relevance to what we have known all along about preparing for the end of life. We should make our wishes known about health care decisions well in advance, appoint a health care proxy to make decisions for us if we cannot make them ourselves, and attend to other personal matters. These preparations have always been important but because this pervasive pandemic affects everyone, across all ages, the need for such actions is especially significant.

Yet, perhaps most disturbingly, what I formerly discussed with students about the ethics of the use of scarce resources has moved from a classroom exercise to a near unavoidable practice. A prominent example is the allocation of ventilators. Patients who need ventilators typically use them longer than other patients do. Thus, an increase in the number of ventilated patients not only requires more ventilators but also, when used on COVID-19 patients, they are tied up longer, compounding the need for ventilators.

When ventilators become scarce, by what criteria should we decide who gets one? We will need to move away from the primary focus on the individual patient, which derives its origins from the Hippocratic tradition 2,500 years ago, to take into account the needs of the community, superimposing a public health perspective on the care of people. Current discussions include the development of triage committees comprised of people who are not involved in the care of the patients in question. This is a distinct departure from how we have made important end of life decisions. Rather than having doctors talk with the patient and family to arrive at something that aligns with the patient’s wishes, we now may be asking a committee of disinterested persons to make recommendations based on a multi-factor scoring system, which could include valuations of the sick person’s age, coexistent illnesses, and other determinants of prognosis.

An even more ethically fraught question is, how do we decide who no longer should have a ventilator? Until now, doctors have withdrawn ventilators for two related reasons: the patient’s clinical situation is futile, meaning, nothing can be done to improve that person’s medical condition or it is the wish of the patient to stop treatment, often expressed by the patient’s surrogate decision-maker. Now, another reason could be that a different patient might need the ventilator more. Perhaps at some point the ventilator should be taken from a person with a poor prognosis and given to a person for whom there is greater hope. Perhaps the most difficult adjustment we will need to make will be that a person’s previously expressed wishes about end of life decisions could be overridden, presumably in the best interests of other people rather than what the individual has deemed best for themselves.

One of the most poignant effects of this pandemic on dying became real to me recently when I learned of the death of a former colleague. He had lived a long and extraordinarily productive life, was admitted to a hospital because of complications of a chronic illness, and developed COVID-19. Here was a real person, not a statistic, not someone I had read about or seen on TV. Because of restrictive visiting policies, loved ones and friends could not visit him. He died alone under circumstances that subvert much of what we think is right at the end of life.

Death stills lays claim as the common, final experience. However, what seems to have changed now is that, because of restrictions on funerals and gatherings for memorial services and the like, COVID-19 reaches beyond death to affect the traditional celebrations and remembrances of the deceased. The disease’s heavy grip is evident on both sides of the moment that divides the end of life from eternity.

Featured Image Credit: 3345408 via Unsplash

The post The process of dying during a pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

April 22, 2020

Who is Dr. Doddipol? Or, idioms in your back yard

Would you like to be as learned as Dr. Doddipol? Those heroes of our intensifying similes! Cooter Brown (a drunk), Laurence’s dog (extremely lazy), Potter’s pig (bow-legged), Throp’s wife (a very busy person, but so was also Beck’s wife)—who were they? I have at least once written about them, though in passing (see the post for October 28, 2015). They show up in sayings like as drunk as…, as lazy as…, as busy as…, and so forth. Many people have tried to discover the identity of those mysterious characters. In the late eighteen-seventies, Notes and Queries, an outlet for the wise, the ignorant, and the curious, published many letters on so-called personal proverbs. Antiquarians, professional linguists, historians, and ingenious amateurs contributed to the solution of the mystery. To be sure, of equal interest is the identity of the likes of little Jack Horner (the pie-eater), Jack Spratt (who, by contrast, could eat no fat), and even Mary (the owner of a little lamb). Although the characters of nursery rhymes have been investigated much more often and with better results than Throp’s wife (let alone Potter’s pig), Cooter Brown and his boon companions are also worthy of a biography. Sometimes we are lucky. For instance, the word doddipol, gracing the title of this post, meant “dotard, fool,” so that a person as learned as Dr. Doddipol (honoris causa?) should be no one’s role model.

Could this be Laurence’s dog? Image by Alexandr Ivanov from Pixabay.

Could this be Laurence’s dog? Image by Alexandr Ivanov from Pixabay.Domestic animals figure prominently in such sayings, so that Potter’s pig is no exception. Thus, one can (could?) be as coy as Croker’s mare. No one has encountered either this mare or its owner and hardly ever will. Yet one detail about the couple arouses our suspicion: Croker alliterates with coy. And indeed, the earlier variant was as coy as a crocker’s mare (the indefinite article and crocker, not Croker). According to an old suggestion: “It may perhaps be interpreted as quiet as a crocker’s or crock-dealer’s horse, inasmuch as a restive jade would smash all the earthenware hawked round in such carts. Crocker meant also a seller of saffron, which is less appropriate.” Indeed, “crocks or earthen pots hawked about for sale in panniers on an animal’s back, required a steady-going one.” Have we buried the ghost and solved the riddle? Perhaps.

The best of gray mares. Image by Bénédicte ARROU-VIGNOD from Pixabay.

The best of gray mares. Image by Bénédicte ARROU-VIGNOD from Pixabay.By the way, mares are common characters in idioms. Probably the most famous and the most enigmatic saying is the grey (gray) mare is the better horse (said about a henpecked husband; the color epithet makes this pronouncement particularly obscure). On the other hand, no etymology is needed for understanding the saying money makes the mare go. It alliterates throughout and could occur in some old poem, but, regardless of the source, its lesson is clear. In Croker’s mare we face the same problem as with Dr. Doddipoll: a common or a proper name? With numerous family names like Potter, Smith, Cooper, Baker, and Plummer one never knows.

Finally, we wonder at taken napping, as Mosse [or Morse] caught his mare. The farmers of South Devon sang a ballad, whose last line of each verse was “As Morse caught the mare,” but who Morse was and what happened to his mare is enveloped in obscurity. At least we have an inkling of the source. Quite a few catch phrases originated in popular songs, including those made famous by the music hall.

Dr. Doddipol was learned. He was not alone: Waltham’s calf was wise. Whenever folklore (and sayings of this type are part of folklore) calls somebody clever or learned, rest assured that such a character is a fool. Conversely, when a youngster has the reputation of a dullard (like the third son in fairy tales), we expect him to outsmart his rivals and marry the princess (a boon eagerly sought after). Therefore, since the proverbial phrase refers to someone as wise as Waltham’s calf, we suspect that the calf was not a paragon of quick wit (of infinite resource and sagacity, as Kipling would put it). And indeed, we are told of “Waltham’s calves to Tiburne needs must go/To sucke a bull and meete a butcher’s axe.”

The reference to this stupid calf was known as early as the middle of the seventeenth century and has been recorded in several variants, a usual situation in folklore. Here, the point is that Waltham seems to refer to a place, rather than a person (-ham is “home”; walt is, most probably, “forest”; Modern Engl. wold “a piece of uncultivated forest or moor” is a well-known component of place names). Whether the seat of the famous Waltham Abbey is meant, or the phrase contains a veiled allusion is the infamous place of execution is unclear and, for all intents and purposes, irrelevant.

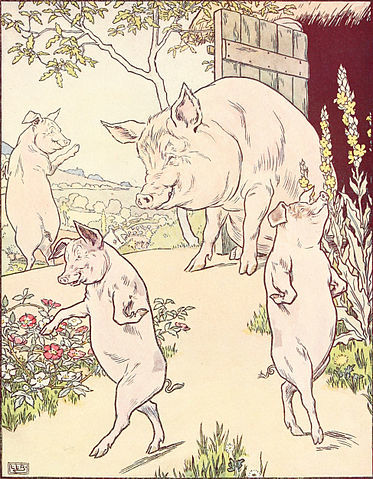

The progeny of David’s sow. From The Golden Goose Book by L. Leslie Brooke, 1905. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The progeny of David’s sow. From The Golden Goose Book by L. Leslie Brooke, 1905. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ours are not the merriest of all times (never mind the opening sentence of A Tale of Two Cities: it has been trodden to death), so to buoy the readers’ spirits, here are a few more moderately funny idioms of the type discussed above. As drunk as Chloe (the lady of this name is often mentioned in the poems of the witty and prolific Matthew Prior, 1664-1721), but perhaps Prior knew the saying and abstracted Chloe from it? Somewhat less dignified, but in the same vein, is the simile as drunk as Davy’s sow. Predictably, no reliable information about Davy, let alone about his alcohol-addicted sow, has turned up. The same holds for the long-suffering Mr. Wood of the phrase as contrairy as Wood’s dog. Stubborn animals in such idioms are usually said neither to go out nor stay at home.

In Gulliver’s Travels, Swift uses the simile as big as a Dunstable lark. We are informed by experts that Dunstable larks “were highly esteemed by epicures by reason of their plumpness and savor.” Dunstable, a town in Bedfordshire, in the east of England, as well as its neighborhood, was as late as 1913 still noted, “though not to the extent as formerly, for the number of larks that congregate there.” Occasionally we receive letters from England. Perhaps someone in Bedfordshire reads this blog and will tell us more about whether its larks have survived two great wars and are still as plump and savory as in days of yore.

Larks straight from Dunstable. Lark bunting from The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Larks straight from Dunstable. Lark bunting from The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Phrases with like in the middle are of the same type. Compare like Hunt’s dog, neither go to church nor stay at home. The saying puzzled people at the beginning of the eighteenth century and, one can expect, earlier (oral tales, naturally, exist for some time before they appear in print), but only apocryphal stories about Hunt’s troubles circulated in the public. May his recalcitrant beast enjoy the companionship of Laurence’s dog (they probably belong to the same litter), Davy’s sow, and Hick’s horses. The last-mentioned phrase alludes to: “Like Hick’s horses, all of a snarl.” This saying is or was (my source goes back to 1878) known in Somersetshire, a county in South West England, when a skein of thread is entangled, “a bystander will remark, ‘Oh, that is like Hick’s horse, all of a snarl’, and by way of parenthesis adds, ‘they say he had only one’. It is then explained that the said horses or horse got entangled in the harness.” A letter from Somersetshire with a comment will be greatly appreciated.

Should every story have a moral? Mine is that idioms are among the most entertaining sources of folklore. They are humorous, caustic, and playful. Studying them makes people wiser and happier.

Feature image credit: Waltham Abbey, interior. Photo by Poliphilo. CC SA 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who is Dr. Doddipol? Or, idioms in your back yard appeared first on OUPblog.

Space for concern: Trump’s executive order on space resources

Among the bevy of executive actions undertaken by President Donald Trump during the COVID-19 crisis is, of all things, an executive order (issued on 6 April 2020) promoting the development of space resources, which states in part that:

Americans should have the right to engage in commercial exploration, recovery, and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law. Outer space is a legally and physically unique domain of human activity, and the United States does not view it as a global commons. Accordingly, it shall be the policy of the United States to encourage international support for the public and private recovery and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law.

But what does this really mean, and is it a good or a bad thing?

The executive order fits the mold of a common rallying call among space advocates that, confined to Earth, humanity exists in a closed society that stifles progress on all fronts, but especially on social and economic fronts. Progress, we’re told, requires an ever expanding space frontier that will provide humanity with limitless resources, removing any need to be concerned about the rate at which we consume natural resources. Further, we’re told, this progress requires a minimally-regulated, free market approach to space resources. It is only through permitting the private sector free reign over space resources that humanity can even hope to see any benefits.

In some respects this new executive order is nothing new at all when it comes to US space policy, given that the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015, signed by then-President Barack Obama, had already codified the US government’s willingness to defend American firms’ claims to ownership over any resources they extract from space. Questions still linger as to whether this law is compatible with Article II of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits national sovereignty claims over celestial bodies (such as the Moon, the planets, and comets and asteroids). Nevertheless, what this executive order does make clear is that the American position is one that decisively rejects the 1979 Moon Agreement, which, had it been widely signed and ratified, would have required space resource exploitation to be conducted under an international regime that would, among other things, require “[a]n equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from [space] resources, whereby the interests and needs of the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the exploration of the moon, shall be given special, consideration.” It should not be difficult to see why private firms potentially interested in space mining have long been opposed to the Moon Agreement, since the idea of “benefit sharing” does not seem compatible with the goal of running a profitable mining operation.

But to make sense of whether US policy is a step in the right direction, we need to appreciate some of the thornier details about the space resource game. Space resource advocacy rests on a mistaken conception of whether and to what degree space resources will benefit humanity. The first issue is that space resources, while nearly limitless in principle, are nevertheless quite scarce in practice. The two most tantalizing resources from the Moon – water ice (from the “permanently shadowed regions” in the lunar north and south poles) as well as a fusion fuel source, Helium-3 (implanted in the lunar surface from the solar wind) – do not exist in very large quantities. The same is true for easily accessible near-Earth asteroids, to which we might turn for water, nickel, or platinum. For instance, estimates of the quantity of water potentially available from permanently shadowed regions together with the asteroids that are as “easy” to get to as the Moon only total to about 3.7 km3. This water supply is both limited and non-renewable, and thus cannot be exploited sustainably. Once we use it up, it is gone. Meanwhile, the highest concentrations of Helium-3 are measured in tens of parts per billion.

To produce just 1 kg of Helium-3 would take enough lunar regolith to fill a 6 m deep hole the size of an American football field (including endzones).

The picture that should be emerging is one where important space resources are, for the time being, in very short supply. Clearly, we can’t expect them to herald the salvation of humanity’s resource concerns, since these quantities pale in comparison to what is already available in terrestrial markets. Moreover, we won’t even be able to access the vastly larger resource pools available (the rest of the near-Earth asteroids, the Main Belt asteroids, etc.) unless we use our early spoils to expand our spaceflight and space resource extraction capabilities.

The possible future in which space resources actually become available in sufficient quantities to benefit all of humanity will only come to pass if we use what we get first very wisely. If we waste all of the precious, rare lunar water ice on trivial activities like space tourism, we might never develop the ability to access more distant resource pools.

Will the free market enable the wise, rational, and sustainable extraction and consumption of nearby space resources?

Free market principles have an incredibly poor track record on Earth when it comes to ensuring the long-term, sustainable, and genuinely life-enriching extraction and use of natural resources. We should be skeptical, not hopeful, that the same principles will suddenly have better consequences when it comes to space resources. A future where space resources genuinely benefit humanity (which to me means benefitting its least fortunate members and not just the wealthy few who will operate space mining firms) is a choice, not an inevitability. For the time being, it seems as though the United States has chosen a path that is not likely to realize this future.

More broadly we should ask: Are moons, planets, and asteroids mere resources for humans to use however they please? Or might we have obligations to conserve or protect space environments, placing them off-limits, even if only temporarily, to commercial extraction and use?

Featured image from Wikimedia Commons.

The post Space for concern: Trump’s executive order on space resources appeared first on OUPblog.

Space for Concern: Trump’s Executive Order on Space Resources

Among the bevy of executive actions undertaken by President Donald Trump during the COVID-19 crisis is, of all things, an executive order (issued on 6 April 2020) promoting the development of space resources, which states in part that:

Americans should have the right to engage in commercial exploration, recovery, and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law. Outer space is a legally and physically unique domain of human activity, and the United States does not view it as a global commons. Accordingly, it shall be the policy of the United States to encourage international support for the public and private recovery and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law.

But what does this really mean, and is it a good or a bad thing?

The executive order fits the mold of a common rallying call among space advocates that, confined to Earth, humanity exists in a closed society that stifles progress on all fronts, but especially on social and economic fronts. Progress, we’re told, requires an ever expanding space frontier that will provide humanity with limitless resources, removing any need to be concerned about the rate at which we consume natural resources. Further, we’re told, this progress requires a minimally-regulated, free market approach to space resources. It is only through permitting the private sector free reign over space resources that humanity can even hope to see any benefits.

In some respects this new executive order is nothing new at all when it comes to US space policy, given that the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015, signed by then-President Barack Obama, had already codified the US government’s willingness to defend American firms’ claims to ownership over any resources they extract from space. Questions still linger as to whether this law is compatible with Article II of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits national sovereignty claims over celestial bodies (such as the Moon, the planets, and comets and asteroids). Nevertheless, what this executive order does make clear is that the American position is one that decisively rejects the 1979 Moon Agreement, which, had it been widely signed and ratified, would have required space resource exploitation to be conducted under an international regime that would, among other things, require “[a]n equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from [space] resources, whereby the interests and needs of the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the exploration of the moon, shall be given special, consideration.” It should not be difficult to see why private firms potentially interested in space mining have long been opposed to the Moon Agreement, since the idea of “benefit sharing” does not seem compatible with the goal of running a profitable mining operation.

But to make sense of whether US policy is a step in the right direction, we need to appreciate some of the thornier details about the space resource game. Space resource advocacy rests on a mistaken conception of whether and to what degree space resources will benefit humanity. The first issue is that space resources, while nearly limitless in principle, are nevertheless quite scarce in practice. The two most tantalizing resources from the Moon – water ice (from the “permanently shadowed regions” in the lunar north and south poles) as well as a fusion fuel source, Helium-3 (implanted in the lunar surface from the solar wind) – do not exist in very large quantities. The same is true for easily accessible near-Earth asteroids, to which we might turn for water, nickel, or platinum. For instance, estimates of the quantity of water potentially available from permanently shadowed regions together with the asteroids that are as “easy” to get to as the Moon only total to about 3.7 km3. This water supply is both limited and non-renewable, and thus cannot be exploited sustainably. Once we use it up, it is gone. Meanwhile, the highest concentrations of Helium-3 are measured in tens of parts per billion.

To produce just 1 kg of Helium-3 would take enough lunar regolith to fill a 6 m deep hole the size of an American football field (including endzones).

The picture that should be emerging is one where important space resources are, for the time being, in very short supply. Clearly, we can’t expect them to herald the salvation of humanity’s resource concerns, since these quantities pale in comparison to what is already available in terrestrial markets. Moreover, we won’t even be able to access the vastly larger resource pools available (the rest of the near-Earth asteroids, the Main Belt asteroids, etc.) unless we use our early spoils to expand our spaceflight and space resource extraction capabilities.

The possible future in which space resources actually become available in sufficient quantities to benefit all of humanity will only come to pass if we use what we get first very wisely. If we waste all of the precious, rare lunar water ice on trivial activities like space tourism, we might never develop the ability to access more distant resource pools.

Will the free market enable the wise, rational, and sustainable extraction and consumption of nearby space resources?

Free market principles have an incredibly poor track record on Earth when it comes to ensuring the long-term, sustainable, and genuinely life-enriching extraction and use of natural resources. We should be skeptical, not hopeful, that the same principles will suddenly have better consequences when it comes to space resources. A future where space resources genuinely benefit humanity (which to me means benefitting its least fortunate members and not just the wealthy few who will operate space mining firms) is a choice, not an inevitability. For the time being, it seems as though the United States has chosen a path that is not likely to realize this future.

More broadly we should ask: Are moons, planets, and asteroids mere resources for humans to use however they please? Or might we have obligations to conserve or protect space environments, placing them off-limits, even if only temporarily, to commercial extraction and use?

Featured image from Wikimedia Commons.

The post Space for Concern: Trump’s Executive Order on Space Resources appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers