Oxford University Press's Blog, page 154

April 6, 2020

Why gun owners could be the decisive vote in 2020

Recently, Joe Biden visited a construction plant in Michigan. A worker confronted Biden and accused the former vice president of “actively trying to diminish our Second Amendment right and take away our guns.” Biden, in turn, responded, “You’re full of shit.”

The exchange continued, cameras rolling, Biden clearly sensed an opportunity, recognized the political value of the moment. Biden’s staff stepped in to try and move him aside. He waved them off. After all, his successful legislative record on guns – including the 1994 passage of a 10-year ban on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines – and frequent boasts about taking on and beating the NRA were at stake. Dodging the worker’s accusations was not an option.

Biden’s assertive posture on guns recalls the 2000 election. And this worries Democrats.

In 2000, the Democrat Party Platform celebrated Al Gore’s record of standing up to the NRA, the legislative successes of the Clinton administration, namely the Brady Bill and the Assault Weapons Ban, and called for mandatory gun locks and a host of federal programs regulating gun purchases.

Al Gore lost. Democrat leaders attributed the loss in part to gun owners support for George W. Bush, especially in states Gore was defeated including his home state of Tennessee. Public opinion surveys showed Bush won a historically large share of the gun owners vote – 66%, only Bush senior in 1988 attracted a greater proportion – 68%. To win elections, centrists Democratic strategists, concluded “Democrats need to reason with gun owners rather than insult them.”

Gun owners have long been a reliable GOP voting bloc. The General Social Surveys demonstrate that in 10 of the last 12 presidential elections, a majority of gun owners supported Republican candidates. Even when the nation supported a Democrat, gun owners typically remained loyal to Republicans. And in 2016, Donald Trump garnered over 60% of gun owners, which was the largest share since Bush in 2004. In the 2018 midterms, 61% of gun owners voted for Republican candidates compared to just 26% of non-owners, a 35-point gap.

This is not a small or insignificant political group. Opinion surveys estimate a third to 40% of households have a gun. That percentage increases notably among the all-important rural voting population. Moreover, in several key swing states gun owners comprise a substantial proportion of voters, including Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan, and Wisconsin. As Democrats remember, in a tight election, gun owners’ vote can be decisive.

But the former vice president believes much has changed since Al Gore’s defeat.

“I have a shotgun,” Biden countered, “I have a 20-gauge, a 12-guage. My sons hunt, guess what? You’re not allowed to own any weapon; I’m not taking your gun away at all.”

Will gun owners believe him? It may not matter.

Gun politics appears to be shifting. Democrats are now better positioned to engage Republicans on guns. Mass shootings repeatedly remind voters of the dangers of gun availability and the unspeakable violence that can result. Gun safety groups are much stronger and better financed than in the past. They outspent the NRA by millions in the 2018 midterms and defeated many NRA backed candidates. Exit polling showed gun policy among Democrats ranked number two behind health care and ahead of immigration and the economy. It ranked fourth among all voters. In addition, gun violence prevention was the top issue among young people.

These facts strengthen Biden and calm fears of many Democrats.

Returning to Detroit, the factory worker repeated he had heard Biden make that claim, that he would take guns away. “It’s a viral video,” the worker declared. “I did not say that! I did not say that! Biden replied, his voice raising, temper flaring, finger pointing. “Don’t be such a horse’s ass,” he added.

Predictably, the NRA released the video of the confrontation on twitter with the headline “Joe: Gun owners see through your lies.”

Biden’s campaign touted the video as well, using it to spotlight Biden’s authenticity and strong advocacy for gun control and his long-time commitment to an assault rifle ban.

Both sides are dug in, their collective heels firmly planted. Both are betting their position on guns will be the winner.

The 2020 contest will be close; it will be an epic battle.

Which party prevails may turn on whether swing state gunowners believe the factory worker or Joe Biden.

Image credit: Photo by visuals on Unsplash

The post Why gun owners could be the decisive vote in 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 5, 2020

Maths can help you thrive during the COVID-19 pandemic

When Isaac Newton practiced social distancing during the Great Plague that hit London in 1665, he was not expected to transition from face-to-face work with scientist colleagues to a patchwork of conference calls and email. With no children underfoot who needed care at home, he concentrated on developing early calculus ideas. With no exposure to a 24-7 news cycle of the escalating crisis, he had the mental space to develop a theory of optics. He even found a quiet moment in which to note an apple falling from a tree, which helped him unlock a fundamental law of physics.

Your efforts to focus on work while social distancing to help flatten the curve of the COVID-19 pandemic may present more challenges. As you adjust, consider the following mathematical metaphors for thriving with your personal and professional goals.

Abandon perfectionism, given the Hairy Ball Theorem

Mathematicians like to say that you can’t comb a hairy ball. The expression is a reference to a curious statement called the Hairy Ball Theorem. To understand this theorem, imagine a ball with an abundance of porcupine quills emanating from it. Now imagine trying to comb the quills so that all lie flat against the ball’s surface.

You might make good progress combing at first. You might even begin to believe that it’s possible to comb the quills so that all lie flat against the ball. However, the Hairy Ball Theorem assures you that you will never succeed. That is, any attempt to comb the hairy ball of quills will always leave at least one quill sticking out.

Working to make progress on personal and professional goals in the midst of a pandemic is a lot like trying to comb a hairy ball. Perfection is an unachievable goal. Put forth your best effort and celebrate your progress.

Resist comparison, given chaos theory

Chaos theory asserts that a small change in an initial condition of an experiment or event may lead to a dramatic change in outcome. The idea is sometimes described as the Butterfly Effect, in which something as inconsequential as the flap of a butterfly’s wings in one part of the world may induce a sequence of events over time that causes a far-off tornado.

What does chaos have to do with this social distancing era? Your initial conditions at the start of the pandemic may have differed from that of a friend or colleague. Perhaps you were more or less farther along with your goals. Maybe you have different caretaking responsibilities for children or aging parents. Perhaps you have an underlying health condition that warrants extra attention. Resist comparing your path to others’ as the exercise is futile; A small difference in your starting place may imply a large difference in outcome.

Be okay with small steps, given the harmonic series

In good times, you may enjoy achieving 100% of what you aim to accomplish in a given day – a sentiment you might represent with an infinite sum of ones, where each “1” in the sum symbolizes the feeling of “achieving 100%” on a collection of sequential days moving forward:

This infinite sum approaches infinity, which might suggest that “the sky’s the limit” regarding your personal and professional goals.

However, in challenging times, some pursuits might leave you feeling like you’ve hit a ceiling. You might represent this scenario with an infinite sum in which each consecutive term gets noticeably smaller according to a pattern:

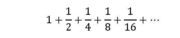

What does this sum equal? Note that you might rewrite each term in the sum as the areas of the increasingly smaller squares and rectangles in the following sketch:

So, this infinite sum must equal the area of the largest, outer rectangle whose length is two and width is one. Since the area of any rectangle is its length multiplied by its width, you obtain:

As this example illustrates, some infinite sums of increasingly smaller numbers are bounded. If the terms in this sum represented a fraction of what you accomplish in collection of consecutive days moving forward, you might be understandably discouraged.

However, when the challenges of social distancing leave you unable to achieve 100% of your daily goals, you might draw inspiration from a different infinite sum known as the harmonic series:

The harmonic series grows much more slowly than the infinite sum of ones – so slowly that the sum of the first 100 terms does not even reach six. Nonetheless, like the infinite sum of ones, the harmonic series also approaches infinity. It has no upper bound at all.

If pandemic-induced social distancing slows progress towards your goals, be okay with taking small steps. Like the harmonic series, the size of your steps does not limit you; the sky may still be the limit.

Mathematics is more than a tool for computation. The field offers an invitation for deep, delightful thinking, along with metaphors for fostering courage in challenging times.

Featured image via Pixabay.

The post Maths can help you thrive during the COVID-19 pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

The Perfect Tenses in English

What could be simpler than grammatical tense—things happening now are in the present, things happening before are in the past, and things that haven’t happened yet are in the future.

If only it were so easy.

Consider the present tense. Its meaning often refers not to things happening right now but to some general state of affairs, as in Italians eat salad after the main course or Healthy people exercise regularly. If you want to indicate something actually going on in the moment, the present progressive is used: a present tense be verb followed by the –ing participle, as in Allison is visiting her sister or Carlo is eating a salad.

We use a present tense form of the auxiliary verb have followed by the –en or -ed participle to create what is known as the present perfect tense, as in The lake has frozen or Dennis has eaten all the cookies. In these two examples, the combination of present tense and perfect aspect indicates a completed change of state in the first case—from unfrozen to frozen—and a completed action in the second—the cookies are eaten. One of the uses of the present perfect is to depict activities begun in the past and completed at present.

The present perfect, however, can also be used to refer to activities begun in the past, true at present, and possibly continuing into the future:

Carlsen has defended his championship again.

The soccer team has won every match.

For many years, children have eaten too much junk food.

The meaning of the present perfect is that, as of the present moment, the activity described by the verb has been completed, for now.

If you put the auxiliary verb in the past tense, then you get the past perfect: The lake had frozen or Dennis had eaten all the cookies. Here, an activity was completed in the past, even if that past is just a few seconds ago. The past perfect (also known as the pluperfect) often occurs with adverbial clauses or other modifiers indicating what happened next, as in The children had eaten a lot of junk food until their parents realized it wasn’t good for them or The lake had frozen by the time we got there.

You can even combine the perfect with the future to craft sentences in which the completion of the action is projected or contemplated to be in the future: The lake will have frozen by the time we get there.

The perfect tenses are often used in narrative to backshift an action or description. Here are three examples:

The captain had long since returned to his post and the guards, having swapped their belligerence for boredom, now leaned against the wall… (from Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow)

In Towles’s past tense narration, the had … returned and having swapped situate certain actions in the past with respect to the event being described.

It was only later that he realized the reason they had called him, but by then it was too late for the information to do him any good. At the time, all the two men had told him was that they had seen his picture in the paper… (from Brian Evenson’s Last Days)

Once again the perfect tenses place the calling, telling, and seeing further in the past.

I had seen it many times before, on screens. … his beard had become, over the previous months…a full-on international brand (from Sam Anderson’s Boomtown).

In this example describing basketball player James Harden’s beard, had seen connotes an indefinite number of past beard-seeings while had become stretches the becoming into the recent past and the potential future.

To get a full flavor of the utility of the past perfect, try mentally replacing it will the simple past in any of those examples. The past events become more immediate—and less effective: The captain returned to his post. It was only later that he realized the reason they called him. I saw it many times before, on screens.

The present perfect often finds its way into dialogue, where someone is speaking about an event in the immediate past. Consider these two examples also from Amor Towles, after Count Rostov has been signaled by Andre:

“What has happened?” asked the Count when he reached the maître d’s side.

“I have just been notified that there is to be a private function in the Yellow Room, after all.

Examples of the future perfect are harder to find in the wild. Here is one from Ted Chiang’s science fiction “Story of Your Life,” in which Louise Banks is narrating future events to her daughter.

“By then Nelson and I will have moved into our farmhouse, and your dad will be living with what’s-her-name.”

“Your nursery will have that “baby smell” of diaper rash cream and talcum powder, with a faint ammoniac whiff coming from the diaper pail in the corner.”

The terminology of the perfect can be a little confusing. Some traditional grammars often refer to the past perfect, present perfect, and future perfect as tenses; others reserve tense for the simple past, present, and future and refer to the perfect as a verbal aspect. Whatever you call it, the perfect brings the flow of time into play.

Featured Image Credit: by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

The post The Perfect Tenses in English appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2020

How religious sects can be a force for good

On Sunday, 29 March, Russell M. Nelson, president of the 16-million-member Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, released a video from Salt Lake City calling on church members everywhere to join in a fast “to pray for relief from the physical, emotional, and economic effects of this global pandemic.”

Some 71 years before, on 6 April 1949, members of the True Jesus Church around the world responded to the call of their leader, Wei Yisa, to fast and “pray for peace.” Communist forces were advancing on the city of Nanjing, where the church headquarters was located. Shortages were severe and prices were skyrocketing.

“It is hard to buy even one grain of rice,” reported an article in the Holy Spirit Times, the church’s international periodical.

One month’s worth of contributions is not enough to cover basic needs such as a day’s vegetables. It is not enough to cover even one day’s postage. We have begun to take good wood beams intended for building and sell them for firewood.

A worldwide fast as a response to a life-threatening crisis, just as spring was beginning to warm the days and coax bright colors from the earth, is a lot for these two churches to have in common. But the parallels go far beyond this.

Both the True Jesus Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are restorationist churches, claiming to have restored the true gospel of Jesus Christ after centuries of apostasy. The Latter-day Saint tradition starts in the spring of 1820 when a New York farmboy named Joseph Smith said he had a vision in which God the Father and Jesus Christ told him none of the existing churches were true. The True Jesus Church tradition starts nearly a century later in the spring of 1917, when a rural northeastern Chinese man named Wei Enbo said he had a vision in which Jesus Christ commanded him to “correct the Church.”

Both Smith and Wei were charismatic leaders who claimed to receive divine revelation, were reported to have performed miraculous feats of healing, frequently got on the wrong side of the law, and died young. Both were succeeded by pragmatic leaders (Brigham Young and Wei Yisa) who solidified church institutions and ensured the movement’s long-term survival.

Both churches have continued to thrive and expand globally, though they remain tiny as far as world religious movements are concerned. In 2017 the True Jesus Church, now with 1.5 million members, commemorated the 100th anniversary of Wei Enbo’s founding vision. This year the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, claiming 16 million members, celebrates the 200th anniversary of Joseph Smith’s first vision (coincidentally, the day Smith formally organized the church in 1830 was 6 April—the same day as the True Jesus Church fast in 1949).

Restorationist churches are by nature exclusivist. For instance, Wei Enbo taught that no one could be saved unless they were baptized face-down and unless they had spoken in tongues. This exclusivist certainty leads to a universalistic orientation. In other words, the more a religious tradition insists that specific particulars of theology and practice are absolutely essential, the more likely it is to have mission outposts everywhere. If you believe your church is the only complete form of Christianity, when you move to another city or country, the local cathedral or neighborhood megachurch will not meet your needs. Wherever you go, you will seek out fellow believers like yourself, and if there are none, you will begin to seek converts.

Small, exclusivist religious groups tend to irritate people around them. Throughout their history, fellow Christians have labeled these two churches as disreputable and cultish. The Latter-day Saint movement began in upstate New York, but was driven west by flare-ups of mob violence and state suppression. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Communist party-state banned the True Jesus Church, imprisoning leaders and forcing rank-and-file members to meet secretly in their houses.

It’s sometimes difficult for upstart religious movements to strike the right balance between what sociologist Armand Mauss has called the twin dilemmas of respectability and disrepute. This is evident with the case of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus at the center of the coronavirus outbreak in South Korea. Also led by a charismatic individual, also accused of being a cult, and also with a membership that likes to do things together, the church is now under fire.

Yet the resonance between the worldwide fasts of the True Jesus Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the spring of 1949 and 2020 suggests that such small but distinctive religious traditions also have something uniquely positive to offer. In the aftermath of World War II and today at the beginning of the twenty-first century, concepts such as “global arena” or “global community” are certainly viable. Yet in actuality, with real people, global scale tends to be overwhelming. It is nearly impossible to cast a global net without being sunk by the size of the catch. Small religious movements, however, are better positioned to pull it off.

Like Wei Yisa’s appeal to the True Jesus Church members in 1949, Russell M. Nelson’s call for a fast at the beginning of the first week of April 2020 went out to believers in such places as China, Japan, Malaysia, and the United Kingdom. Tens of thousands, possibly even millions of stomachs around the world went empty in concert. A fast offering was also collected to aid humanitarian efforts to ease the blow COVID-19 is dealing to the most vulnerable.

In times of global pandemic, inhabitants of the planet realize how inextricably we are connected, and also how little we usually have to do with each other, given vast divides in language, culture, space, and experience. In times like these, believers in tiny global communities who have long been eager to call each other sister and brother offer a sense of what is possible.

Featured Image Credit: by Ben White on Unsplash.

The post How religious sects can be a force for good appeared first on OUPblog.

Why vaccines should be compulsory

Imagine we develop a vaccine against the coronavirus (COVID-19). Suppose the vaccine has some very small chance of some serious side effects, for instance seizures. However, this vaccine can save millions of lives globally, in the same way as other vaccines do. You are the prime minister and you have to decide whether to make the vaccine compulsory. You know that many people are opposed to vaccines and especially compulsory vaccination. They would not vaccinate even if failure to vaccinate enough people would result in a pandemic that would kill millions of people worldwide and devastate the world’s economy. They think that the state should have no business in telling us what should go into our bodies, that vaccines are harmful, that infectious diseases are no riskier than vaccines, and that the claims about the COVID-19 outbreak have been exaggerated or even made up to promote compulsory vaccination campaigns by Big Pharma.

The example at this point is no longer purely hypothetical, unfortunately. Even now, as the coronavirus pandemic is getting worse and worse and killing an increasing number of people every day, there are those who would not want to vaccinate against COVID-19 if this vaccine was available, for all these reasons. One of us wrote a short article three years ago defending mandatory vaccination policies. As the latest contagion started spreading in the US, people started commenting on that article again, suggesting that this virus is a scam and that various people have engineered it to boost pro-vaccine campaigns. For instance, someone wrote: “What a crock (…) this is from 2017 and three years later Italy is right up there with S Korea and China for Coronavirus cases. Yeah that crap doesn’t work”. Other comments are more explicit.

Now let’s jump back in time. Suppose you are the prime minister in the early 1990s. You are dealing with a different public health problem: the very high number of victims of car accidents. Cars are not as safe as they would be in 20 or 30 years (no airbags, no anti-lock brake systems, and so on). However, some other countries have started introducing seat belt requirements. You look at the figures and you see that seat belt requirements significantly reduce the number of injuries and deaths from car accidents. For example, it is estimated that risk of death is reduced by 45% and risk of serious injury by 50% in a country like the United States. However, you know that many people are opposed to seat belt mandates, because they think that the state has no business in telling us what risks we can take for ourselves and for our children, that it is not true that seat belts improve safety, and that seat belt requirements are the result of lobbying from the seat belt industry. You might be a bit more surprised than in the case of vaccination to learn that also this example is not purely hypothetical; this is precisely what happened when seat belt requirements were introduced between the ’80s and the ‘90s.

Vaccines are like a seat belt against infectious diseases, and that vaccination mandates are justified for the same reasons seat belt mandates are. Actually, the justification is stronger when it comes to vaccine mandates. If you fail to buckle up yourself or your child, you are putting yourself and your child at unnecessary risk, and perhaps other people at some small risk too (for instance, those who are not buckled up in the back seat are more likely to kill or injure those in the front seat in case of accident). But if you fail to vaccinate yourself or your children there is a much larger risk of harming other people who are not vaccinated (for example those who are immunosuppressed, young children or those whose immunity has waned over time), besides imposing an easily preventable risk on you and your children.

Now, here is the elephant in the room. Vaccines might entail some small risks. For instance, it seems that in very rare circumstances (one to two cases per million doses) the flu vaccine could cause Guillain-Barré Syndrome, although the evidence is not clear and the cases are so few that it is difficult to provide a statistical estimate.

And here is where the analogy with seat belt requirements becomes very effective. Seat belts, in rare circumstances, can cause injuries and even deaths that would not have occurred if people had not been buckled up. Sometimes the dynamics of car accidents are such that people would be better off without seat belts, e.g. when seat belts prevent them from getting out of the car fast enough to avoid drowning or fire. And there are injuries that form a specific injury profile labelled “seat belt syndrome,” which can be serious and require surgery.

And yet, the vast majority of people support seat belt mandates and eagerly buckle up these days. Wearing seat belts has become not only a legal requirement, but also a social norm in the vast majority of countries. And this is how it should be, because seat belts do save many lives. As vaccines do, in spite of very small risks, in both cases. Injuries from car accidents are way more common and way more likely to be lethal than injuries from seat belt use. And in the same way, many infectious diseases, such as measles, are way more likely to harm and to kill than vaccines.

If the very small risks of seat belts are not a good enough reason against seat belt requirements, then the very small risks of vaccines are not a good enough reason against mandatory vaccination.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Empty vehicle bench seat’ by Therese Mikkelsen Skaar. CCO public domain via Unsplash.

The post Why vaccines should be compulsory appeared first on OUPblog.

April 3, 2020

The surprising scientific value of national bias

Emotions seem by their very nature to defy scientific analysis. Private and evanescent, and yet powerful and determining, feelings resist systematic observation and measurement. We are lucky to catch a glimpse in a facial expression or inflection of speech. The emotions of animals are all the more difficult. Without words to communicate what might be in their minds or on their nerves, animals–ranging from the complex to the simple–remain nearly a closed emotional book for even the cleverest experiment. A century ago Robert Yerkes, then at Harvard, registered these frustrations. Little is “of more obvious importance scientifically than affection,” he wrote in his Introduction to Psychology, in 1911, but its study lags behind investigation of “cognitive consciousness.” Convenient as it might be to assume animals are machinelike anyway, our behavior in the laboratory, he observed earlier in his Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology in 1906, betrays our logic. “Even those who claim that animals are automata do not treat them as such.”

Shrewd as Yerkes was about his specialty of animal behavior, he would have been puzzled by the idea that national loyalty influenced his science. His research ethos was empiricism: Infer conclusions from carefully collected facts. As he succinctly advised in 1904 in the same journal, “experiment much and speculate little.” Other Americans agreed. John B. Watson’s “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It” of 1913 proposed to make the field “purely objective” by jettisoning the “yoke of consciousness.” That a conscious mind exists at all, in Watson’s view, was mere supposition. It makes sense that it was the German-born émigré ornithologist, Ernst Mayr, who recognized the American devotion to practicality as a national bias. When his Dutch friend, Niko Tinbergen, planned lectures for a US tour in 1946, Mayr counseled wrote to him that “American scientists do not care for too much speculation but like thorough analysis of observed phenomena.” Indeed, deficient experimentation and excessive theorizing became a polemical weapon in international debate. Intellectual precision was–and is–the mark of good science, but American investigators of animal sensibility once claimed it as their special national possession.

Although the danger of scientific myopia nurtured by pride is obvious, these Americans’ faith in their superior practice ironically became a path forward toward internationalism. Their zeal for conducting animal behavior experiments produced real insights into affective experience. They had something to contribute abroad. In the process, they traveled the world for fieldwork, made far-flung professional acquaintances, and opened the door to refugee scientists displaced by the twentieth century’s political turmoil. Scientific passion stoked nationalism, but also gradually undermined it.

Researcher L.W. Cole works with a raccoon, 1905. Used with permission from Yale Library.

Researcher L.W. Cole works with a raccoon, 1905. Used with permission from Yale Library.Animal experiments became one area of American expertise. Nonhuman subjects, by their very lack of language and inability to deceive in self-reports, were a perfect fit for a method based on external observation. The variety of species studied included the proverbial white rat, but many others as well. Although Yerkes spent three decades after World War I focused on primates, he had earlier measured learning in newts, frogs, mice, crows, and pigs. His colleague Edward Thorndike watched chicks, cats, and dogs escape from puzzle boxes, and Yerkes’s student L. W. Cole did the same with raccoons. So much scrutiny of animals expanded the researchers’ appreciation of their personalities. Intelligence, understood as skill acquisition, was the original question. Mood and temperament were annoyances. A tired rat knew where to find the bit of bread, but stopped running for it. It is not surprising that the emotions themselves eventually caught scientific interest. Donald Griffin rattled his field in The Question of Animal Awareness of 1976 when he declared, against reigning local wisdom, that animals are conscious. They have “not only images and intentions, but also feelings, desires, hopes, fears.” His revolutionary claim was the endpoint, however, of a typical American career. Three decades before, Griffin discovered how bats maneuver in the dark by echolocation, a kind of intelligence. His wonder at the animal mind deepened over the years.

To be sure, American scientists never had a monopoly on insight into animal behavior. The counterexample of Darwin is enough to deflate any sense of supremacy. Their enthusiasm for controlled animal experiments produced so many competent studies, however, that they may have had an outsized influence. One British book of 1915, Investigation of Mind in Animals by E. M. Smith, borrowed nearly all of its illustrations from American publications. Although the Americans favored laboratory work for its rigor, they increasingly went into the field to witness the vast number of species in native habitats. Yerkes traveled to Senegal in 1929 in pursuit of great apes, and Griffin to Venezuela in 1952 to observe the nocturnal navigation of oilbirds. Often welcomed as respected authorities, they were also exposed to the world’s problems. Walter Cannon of Harvard celebrated “free intellectual intercourse without respect to national boundaries” in his plenary speech at the International Physiological Congress in Leningrad in 1935, published by the state press as Chemical Transmission of Nerve Impulses. His trip by train from Vladivostok to reach the meeting, however, was a sobering political lesson. Seeing prisoners laboring at gunpoint along the tracks in Siberia made for “a queer kind of horror that seizes you now and then,” his wife Cornelia wrote of the trip. Cannon may well not have had immediate doubts about the virtues of his own country, but he surely registered the pressures of nationalism at the borders of science.

Scientist C. R. Carpenter setting up equipment in Thailand in 1937 to record gibbon calls. Used with permission from Penn State Library.

Scientist C. R. Carpenter setting up equipment in Thailand in 1937 to record gibbon calls. Used with permission from Penn State Library.World War II fully exposed the catastrophic cost of national arrogance. International science advanced in its wake. Supported by American colleagues, Mayr achieved US citizenship in 1950 after a decade of government surveillance as a suspect alien. Although the new politics of internationalism was influential, just as crucial was the internal dynamic of science to push its practitioners beyond parochialism. The same high standard that impelled these Americans to apprehend animals in all their complexity–including animal emotions–underwrote growing internationalism. Precisely because the American science of animal behavior was embedded in political life, it had the power to change minds.

Featured image from Pixabay.

The post The surprising scientific value of national bias appeared first on OUPblog.

How downward social mobility happens

The common story about downward mobility is one of bad luck: recent generations have the misfortune of coming of age during an economic downturn, a student debt crisis, declining job security, and, now, a pandemic. Of course, these factors relate to downward mobility, but they are not all that matters. The truth is that many youth step onto mobility trajectories long before they enter the labor market. This truth is important as it can help us explain how some youth born into the same class at the same time become downwardly mobile while others do not.

For upper-middle-class youth, the path toward downward mobility begins early. From a young age, youth receive and accept different resources from their parents – even parents in the same class. Some youth are raised by parents who teach them academic skills, show them how to navigate school, and give them the many opportunities that money can buy. Other parents in the same class possess or pass down fewer of these skills and resources. Within the upper-middle-class, a child may be raised by two college-educated hands-on parents who each transfer these resources, by two college-educated parents who do not have the time, health, or inclination to pass on these resources, or by a college-educated professional parent married to a high-school educated non-professional – a parent in charge of childrearing but who did not obtain high levels of these resources herself.

These early resource differences begin a spiral. Upper-middle-class youth whose parents gave them the resources to succeed in school receive status from their academic successes. They then invest more in school – pouring over their homework, strategizing with teachers, and learning on their own. They are interested in going to college, prepared to excel while there, and see high grades as a way to keep their status in college too. They leave college prepared to enter the professional labor market. When entering a tight labor market and a world in crisis, they are the ones most likely to find a professional job and remain in the upper-middle-class.

Upper-middle-class youth raised with fewer academic lessons, irregular instructions about navigating school, or with less money are not as likely to gain status from school. Recognizing this, these students do not pour over their books or talk as often with their teachers. Instead, they invest their energy in activities that will bring them status – relationships, sports, art, or even rebellion. These activities have their own rewards, but remaining in their class isn’t one of them. Without focusing on school, college, and professional work, they are often pushed out of their class – especially when there are economic downturns.

The good news about these findings is that avoiding downward mobility is partly in our control. Parents with the resources to do so can teach their children academic skills and how to navigate school, and pay to live in pricey school districts with many extracurricular activities. This is likely to set them on a path to stay in their class. The bad news is that not all parents – even upper-middle-class parents – have these resources or the time to pass them down, and the spirals that follow from them are difficult to break. As children begin to see themselves as athletes, artists, rebels, or defined by their relationships, they become invested in maintaining these identities. These identities bring them status, meaning, and purpose – and, at least as young adults, they may choose these rewards over finding a professional job and remaining in their class.

This moment of economic uncertainty is likely to send some youth on downwardly mobile paths who would have otherwise stayed in the upper-middle-class. But, for others, a recession or pandemic will not be the cause. For some, downward mobility will result from a process that has long been in motion.

Featured image credit: View of Cityscape by Aleksandar Pasaric via Pexels

The post How downward social mobility happens appeared first on OUPblog.

April 2, 2020

Re-reading Camus’s The Plague in pandemic times

Sometime in the 1940s in the sleepy colonial city of Oran, in French occupied Algeria, there was an outbreak of plague. First rats died, then people. Within days, the entire city was quarantined: it was impossible to get out, and no one could get in.

This is the fictional setting for Albert Camus’s second most famous novel, The Plague (1947). And yes, there are some similarities to our current situation with the coronavirus.

First, the denials by those in positions of power. Doctor Rieux, the main character (who turns out to be the narrator) confronts the authorities who reluctantly agree to form an official sanitary commission to deal with the outbreak. The prefect insists on discretion, however, for he is convinced it is a false alarm, or as some would say today, fake news! It is not difficult to hear the echoes of the initial reactions in China and in some parts of the US media landscape regarding the coronavirus.

In between patient visits, Rieux reflects that though calamities are fairly frequent historical occurrences, they are hard to accept when they happen to us, in our lifetimes. This is the story of placid everyday lives lived as routines that are suddenly, brutally disrupted by a virus: an existential reminder of the arbitrariness of life and the certainty and randomness of death. The temptation of denial is a powerful one, both in the book and today with the emergence of the coronavirus.

With the city gates of Oran closing and everyone collectively thrown into interior exile, the gravity of the situation becomes impossible to deny. Families and couples are separated, food rationed and consequently a black market emerges – this reminds us of the run on hospital masks and sanitizing gel in the US, formerly cheap, readily available products, now increasingly sought-after commodities.

As we know, Camus conceived his novel as an allegory for the German Occupation of France from 1940 to 1944, during which families were separated due to the division of the country in two zones, one occupied, one nominally free. In short, the plague is the stand-in for the Germans.

Here with the coronavirus, the challenge resides not in decoding an allegory, but rather in finding out what the pandemic reveals. In other words, what can a genuine global medical crisis tell us about what is fictional or hidden in our lives?

Paradoxically, in these times of self-imposed exiles, school closings and quarantines, the coronavirus tells us about a different kind of globalization. We have now learned that China manufactures most of our medications and medical supplies – not only our consumer goods – and suddenly emerges in our mind the figure of a Chinese worker making our antibiotics and the like: this leads to the stark realization that our survival depends on hers; it is a collective enterprise. We are in it together. This could be the best thing that comes out of the current pandemic.

Feature image: Béchar, Algeria c. 1943 by John Atherton. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Re-reading Camus’s The Plague in pandemic times appeared first on OUPblog.

Donald Trump’s insult politics

Political commentators and satirists love to mock Donald Trump’s verbal gaffs, his simplified vocabulary and vague, boastful speech. But if you judge his oratory by its effect on the audience, Donald Trump’s rhetoric, particularly with large crowds of enthusiastic supporters, is undeniably effective. People have studied the art of rhetoric for millennia – so how does a style that runs counter to all established advice work so well? His use of simple vocabulary and repetition help him connect with listeners. But central to Trump’s style is his use of catchy insults that foster an easy us-them mentality, with Trump and his fans on one side and basically everyone else on the other.

Donald Trump’s stylistic loadstar is the nickname, often composed of a target’s first name and an adjective. In 2016 there was Lyin’ Ted and Crooked Hillary. As the Trump administration has gone forward and the 2020 election is on the horizon we find the president tweeting about Crazy Bernie and Sleepy Joe. Biden was also, in the wake of reports of his handsy campaign style, Sleepy Creepy Joe.

It’s not just potential candidates who get tagged with adjectives: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is Crazy Nancy and the Senate minority leader is Cryin’ Chuck Schumer. Former aid Steve Bannon gets the alliterative Sloppy Steve and Omarosa Manigault becomes Wacky Omarosa. Barack Obama gets the last-name treatment as Cheatin’ Obama, probably not so much out of deference but out of the difficulty of finding an adjective that works well with Barack. Former FBI director James Comey is referred to as Leakin’ James Comey, Lyin’ James Comey, and of course Leakin’ Lyin’ James Comey.

Physicality is also an element of the Trump style. Trump is a big fellow, except perhaps—famously—for his hands. According to his physician, Trump is 6’ 3” and 243 pounds. People who cross him become little or “liddle”: Little Marco Rubio, Liddle Bob Corker or Liddle Adam Schiff or, for Kim Jong-Un, Little Rocket Man (Lil’ Kim was already spoken for). Michael Bloomberg is sometimes Little Michael but also Mini Mike.

Trump also brings the business world mindset of winners and losers, successes and failures, to his insults. The media, of course, are “fake” and “failed” or “failing,” as are various individuals. Also popular are the adjectives “sad,” “dumb,” “loser,” and “nasty.” However, the President’s most common go-to word seems to be “total” or “totally”: people and things are “totally unqualified,” “totally dishonest,” “totally phony,” “total frauds,” and “total losers.” Donald Trump deals in absolutes and imagery, not shades of nuance.

Trump’s critics cast such insults as offensive and puerile, and as both symptom and cause of a decline in political discourse. Some assuredly are. But insults are a long-standing American tradition, and politics have never been polite. The question we might ask then is: are Trump’s insults any good?

If we look back at the history of political insults, we see that a good insult is like a caricature, exaggerating a perceived flaw and fixing it in the public’s perception with wit. Warren Harding’s speeches were referred to as “an army of pompous phrases moving across the landscape in search of an idea.” The phrase captured the public view of the man who called himself a “bloviator.” And a great insult should use images and phrasing that stick over time, often drawing on popular culture rather than playground bullying. When Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder tagged Ronald Reagan as “the Teflon-coated President,” she created a lasting picture of his seeming imperviousness to criticism. And quotable, memorable insults often embrace the poetry of language. They are playful as well as harsh and draw on double meaning, euphony, freshness, and surprise. Teddy Roosevelt’s quip that his predecessor Taft “no doubt means well, but he means well feebly” used repetition to contrast intention and performance. Hunter S. Thompson’s reference to Nixon as “a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president” likewise brings together parallel insults, the first setting up the second.

What makes a Trump insult? There is none of Teddy Roosevelt’s casual erudition or John F. Kennedy’s witty repartee. Teddy referred to candidate Woodrow Wilson as a byzantine logothete, sending journalists to their dictionaries to learn that the logothetes of Byzantium were fiscal managers. To Teddy, Wilson was a mere bean-counter. And JFK, when told that Richard Nixon had tried to insult him as “another Truman,” responded “I consider Mr. Nixon another Dewey.”

How does Donald Trump measure up? His glossary of insults—total, lyin’, cheatin’, crooked, crazy, dumb, sleepy, sloppy, creepy, wacky, liddle, nasty failure—matches our current angry moment. They speak to people who don’t want to look things up in dictionaries. But they are the trick of the salesman not the statesman, replacing erudition with repetition and commentary with name-calling. Like his policies that pander to his fan base at the expense of all else, Trump’s insults speak to the moment, not to history.

Featured Image Credit: by Irina L via Pixabay

The post Donald Trump’s insult politics appeared first on OUPblog.

April 1, 2020

Etymology gleanings for March 2020

Should it be business as usual with the Oxford Etymologist? Closing the blog until better days will probably not benefit anybody. The terrain is like a minefield, but I’ll continue gleaning.

In reply to a complaint, I want to remind our correspondents that comments are posted in New York, and, if something falls between the cracks, the reason may be only an occasional computer glitch. Please resend your comments. By contrast, I do not react to everything I receive. Sometimes I have nothing to say. For instance, I have read a good deal about the Silk Road and told what I know about it in the previous posts. Rehashing the same information would be counterproductive. Yet I don’t believe that silk or Silk Road has anything to do with Engl. side ~ German Seite. I also suggest that those who have difficult questions post them as comments rather than writing me personally, because comments are seen by many, and someone may know a good answer.

Here are three examples of such questions. 1) “Do you know any other word or place name that relied on the accented syllable surviving, as is shown in Milan from Mediolanum?” I am out of my depth here and appeal to Romance scholars in Italy and elsewhere. The change from Mediolanum to Milano seemed to have happened on the basis of both Latin and the Italic languages of Italy, but we need details and analogs. 2) Why does it seem that, at least in English, we have an abundance of words for things very large and very small, but barely any words for things of medium size? I wrote to our correspondent and asked for examples. He did not respond. Yet perhaps someone is also interested in such matters and has an opinion. 3) Mr. Nathan Paige has been working on a list of words similar and, according to him, related in Chinese and English. The examples I examined struck me as relatively unconvincing, but I know nothing about Chinese and will refrain from further comment.

Still at the cutting edge

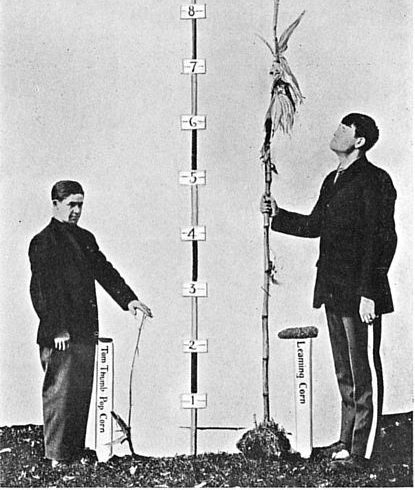

Where is the golden mean? Image from A Critique of the Theory of Evolution by Thomas Hunt Morgan. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Where is the golden mean? Image from A Critique of the Theory of Evolution by Thomas Hunt Morgan. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.As discussed in the previous posts, the oldest recorded form of the Germanic word for “ax” is Gothic aqizi. The Gothic Bible was translated from Greek in the fourth century, and the word Bishop Wulfila saw was Greek aksíne (Luke III: 9; here is the text from the Revised Version: “And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: every tree therefore which bringeth not forth a good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire”). The Goths could have borrowed Greek aksíne, but chose not to do so. However, the similarity between the words is apparent. They are either related or, as noted in an earlier post, we are dealing with the name that traveled from land to land and was modified slightly in its travels: Greek has aksíne, Latin askia (from aksia?), Hebrew hāšīn, Gothic aqizi, and so on. Since we do not know where the story began, we cannot answer the question about the initial form and meaning of the word. The name of a tool need not even reflect its function. As Ion Carstoiu points out, one could invent an awl and transfer the name of some other long and piercing object to it (think of the myriad words for “penis”). The same is also true of many other objects. As usual, God is in the details, and those are hard to reconstruct.

Another Germanic word for “awl” is Old Engl. prēon (Modern Germ. Pfriem, Icel. prjónn) The similarity between prēon and Greek prion “saw; borer” attracted the attention of etymologists long ago. If this similarity is not accidental, the Germanic word was more probably borrowed from Slavic, which was indeed a loan from Greek. A native (Germanic) etymology for prēon has also been proposed. The history of Icel. prjónn is unclear: native or borrowed? In Old Icelandic, prjónn occurred only as a nickname. “Origin disputed.”

Etch, hatchet, and awl

Engl. etch is an eighteenth-century borrowing of Dutch etsen, but this Germanic verb is old and initially had nothing to do with etchings. Even in Gothic, (fra)atjan “give away (to be consumed)” has been recorded. Atjan is the causative of etan “to eat,” that is, “to make one eat.” In some connection, not too long ago, I mentioned causative verbs. The parade example is set from sit. The rule for the formation of such verbs sounds like a recipe from a cookbook. “Take a strong verb, choose its second grade (past singular) and add the suffix –jan to it.” The past singular of etan, the “second grade of ablaut,” was at. In atjan (at + jan), j caused umlaut and the doubling of the consonant—hence ettjan, etsen, German ätzen, and so forth.” Hatchet is a borrowing from French, the diminutive of hache. I briefly discussed it in the introductory post on the names of the ax (March 18, 2020). It is thus not related to etch.

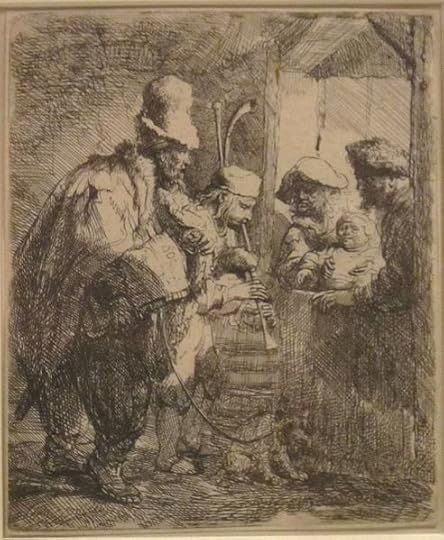

A classic Dutch etching. The Strolling Musicians, Rembrandt. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A classic Dutch etching. The Strolling Musicians, Rembrandt. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Greek trepau may be relatively late, but trepō “to turn, etc.” was a common word in Classical Greek. The suggestion to derive Germanic al– in the Germanic name of the awl from the last two sounds of trepau was probably meant as a joke. The length of the vowel a in the ancient Germanic form is uncertain. It is not necessary to accept secondary lengthening in Sanskrit ârâ, but the reason I chose to stay with short a in Germanic is this: Judging by the borrowed Romance forms mentioned in the post for March 11, 2020, Gothic had some word like alisna, whose a was short. I preferred to be guided by the Germanic, rather than the Sanskrit, form.

Squirrels and acorns

Granted, acorns grow on oaks, and squirrels like acorns. Squirrel is a Romances word, whose Latin protoform was borrowed from Greek, and its origin is crystal clear. The Germanic forms of the word for “squirrel” were neologisms (coined by those who hunted squirrels for fur?), and the forms varied from language to language: Old High German eihhurn(o), Middle Dutch eencoren ~ eenhoorn, Old Norse íkorni. The form íkorni presents some interest, because it has nothing to do with eik “oak,” and only some later dialectal Scandinavian forms begin with eik. Old English had weorn(a), a stub of the Indo-European protoform (w)oiwer, a reduplication (see the post for July 2019), also known from other ancient animal names. Later, it acquired a synonym, almost a doublet, namely, āc-weorn(a) ~ āc-wern; that is, āc was added to the old word in retrospect. Consequently, though an association between squirrels and oaks is obvious, in names like Eichhörnchen it is secondary. The acorn was called akran in Gothic, akarn in Old Icelandic, æcern in Old English, etc. The word has nothing to do with corn, but everything with acre. In my opinion, it is hard to detect the word for “acorn” in the Germanic name of the squirrel, old or new.

Squirrels, oaks and acorns, an indissoluble union. Public domain via needpix.com.

Squirrels, oaks and acorns, an indissoluble union. Public domain via needpix.com.The verb bring (see the post for March 4, 2020)

No source I have consulted suggests that bring has any Baltic cognates. As to the origin of this verb and of German tragen “to carry,” I cannot add anything to what I wrote in that post. The modern past form brung, mentioned in one of the comments, is indeed well-known in dialects.

The state of Spelling Reform

The Expert Commission has produced a shortlist of six schemes from among the 35 submissions received and which passed the sifting process. Several schemes are quite reasonable, and there is hope that the best one will be acceptable to the public on both sides of the Atlantic.

If I survive my well-contented day, you will hear more from me next Wednesday. In the meantime, send letters and comments! We are now like the characters in Boccaccio’s Il Decamerone, so why not start telling one another good tales?

Il Decamerone: We’ll survive! Left image: Gravelot illustration, CC by 2.0 via Paul K on Flickr. Right image: A tale from the Decameron by John William Waterhouse. Collection: Lady Lever Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Il Decamerone: We’ll survive! Left image: Gravelot illustration, CC by 2.0 via Paul K on Flickr. Right image: A tale from the Decameron by John William Waterhouse. Collection: Lady Lever Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Feature image credit: Auditorium at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. Unknown artist, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers