Oxford University Press's Blog, page 153

April 11, 2020

Can you tell the difference between real and fake therapy? [quiz]

Counseling and psychotherapy are professions that should be held to the highest standards—ethical standards, professional standards, and scientific standards, just as all health care services should comply with high standards. In providing health care services to clients, we are asking them to come to us in a state of vulnerability and trust that we are acting from a position of authority with their best interests at heart. And to that end we have developed rigorous education, supervision, licensing, credentialing practices, and requirements for ongoing training. But somewhere between the process of training and the practice of running a business, many practitioners have introduced practices based not on the research of what works but instead on some sort of misguided sense of what the client wants to receive.

An exhaustive study of over 100,000 websites belonging to licensed clinicians discovered 21,758 advertised therapeutic approaches and confirmed that almost all of them lacked any credible reason for using them. Many of these have names similar to proven techniques. Many of them use the language of known academic, scientific, and philosophical orientations. A significant number of these approaches are aimed at incorporating religious, and often specifically Christian or another religion’s values into the therapeutic process, which should raise ethical concerns for any practitioner. There are also any number of approaches that are unambiguously based on new age practices and some that can’t really be categorized beyond saying that they are indeed unusual. The therapists who are promoting these unorthodox approaches to mental health threaten the safety of their clients as well as the survival of counseling and psychotherapy.

Test whether you can recognize the difference between these unvalidated counseling approaches and those that were made up by the author.

Featured Image Credit:by Julien Tondu on Unsplash

The post Can you tell the difference between real and fake therapy? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Protecting workers from COVID-19

Everyone deserves to go home from work safe and healthy. Sadly, during the current pandemic that will not be the case; some workers will die because they became infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus, the official name for the virus responsible for COVID-19, in their workplace. We expect that employers will take all reasonable steps to protect their workers but in truth we know very little about how these workers are exposed and what measures are effective in preventing infection. Governments need to put more research effort into evaluating how effective the current control measures are and in innovating new approaches to better protect workers.

We can become infected in a number of ways. The three most likely routes are from mucous droplets from coughs and sneezes that land directly on our faces; the transfer of virus particles from contaminated surfaces to our nose, mouth or eyes through hand-to-mouth contacts; and by inhaling very small droplets of contaminated mucus suspended in the air.

The most important route is via contaminated hands and this is why there is the ceaseless message from public health professionals to wash your hands frequently through the day, and to avoid touching your face. For most of us inhaling small droplets is an unlikely way to become infected and therefore those wearing facemasks in public are unlikely to see much benefit. However, this is not the case for workers in hospitals and other healthcare settings where there may be specific medical procedures such as intubation that generate high droplet concentrations in the air and efficient respirators and visors can offer important protection during these tasks.

Little is known about the presence of the virus contamination on surfaces in hospitals. We know even less about the concentration of virus in the air. We don’t really know which surfaces to disinfect or when the air concentrations require us to wear a facemask. This lack of evidence means we are using a precautionary approach which often results in our applying all available controls all the time. While this might seem like an effective strategy nobody can continuously maintain such a high level of protection over an extended period. It also means that resources are used unnecessarily, possibly leading to shortages for workers in particular environments where they could provide protection.

Occupational hygienists (also called Industrial hygienists in many countries) are an important public health profession that focuses on protecting workers’ from health hazards at work. Their work spans all hazards from chemicals, dusts, fibres through to physical agents such as noise and vibration, and other workplace hazards. Such people have considerable expertise in identifying hazards, evaluating workers’ exposure to those hazards and implementing effective control measures to reduce risks to health.

Understanding how workers are exposed to the virus will be essential to protect frontline healthcare staff and other at-risk workers such as shop staff, bus drivers and home health care workers. Occupational hygienists have, for many years, been studying the process of how contamination gets onto the skin and how workplace chemicals are ingested through hand-to-mouth contact. There is considerable research that looks at how factors relating to the work process, worker behaviour, and the use of protective equipment all influence the transfer of hazards to the skin and mouth. This work can provide valuable insights for those involved in infection control and developing new ways to protect workers from COVID-19 infection. For example, we know that workers wearing gloves are less likely to touch their face and so this could be a useful strategy for workers outside healthcare who do not normally wear protective gloves.

Occupational hygienists also have considerable experience in selecting suitable personal protective equipment and assessing its effectiveness. Respirators are an important protective measure for many frontline healthcare workers, but to provide reliable protection the masks must be closely fitted to the face or contaminated air will leak between the mask and the face, putting the wearer at risk.

Governments, however, need to promote research into better ways of protecting workers from the virus. In particular research should address:

How important are respirators in protecting healthcare workers from infection?How can we treat or modify surfaces in workplaces to reduce transmission from hand-to-mouth actions?What simple behavioural changes in the workplace can be encouraged to reduce the risk of transmission?There is a great deal of expertise in the occupational hygiene community that can contribute to a better understanding of the spread of this virus and help workers contain and delay community transmission.

Featured image credit: Tedward Quinn. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Protecting workers from COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2020

Children Aid’s Society neighborhood-based programs

Established in 1853, the Children’s Aid Society provided services to homeless children and poor families. Although CAS’s first secretary, Charles Loring Brace, is best known for the “orphan trains”—an initiative that placed children with families in the West—he also built an impressive network of community-based programs in the city. Starting from a small office on Astor Place, Brace systematically experimented for 37 years, expanding programs into an interconnected web. His focus on prevention and voluntary participation differed from the warehousing approaches favored by advocates of asylums and juvenile reformatories.

By the 1880s Brace’s book-length annual reports contained folded inserts that revealed “a condensed map of the city” littered with colored blocks denoting CAS’s “stations of operation.” In 1889, the society operated six lodging houses for homeless boys and girls that sheltered, fed, and clothed, 12,153 children; 33 education programs (including part-time day and night schools) where 151 teachers taught, partially fed, and clothed 11, 331 children and operated school libraries containing 3,282 volumes; health-related programs which treated 7,278 sick mothers and children; and a summer program on Long Island attended by another 4,540 poor children. All told that year 38,853 children had come under the society’s charge. Brace died in 1890 and his son became CAS’s second Secretary. This agency continued to evolve and still exists, nearly 170 years later.

Combatting youth homelessness, illiteracy, and child poverty, Children’s Aid Society forged new methods of intervention. It created a social safety net by providing shelter (short and long-term), food, and clothing. It offered education and skills training programs with flexible hours and creative curricula; recreational activities, banking, and health services. Its impact reducing child and family hardship in New York was enormous and offers lessons for today.

Feature Image Credit: the Library of Congress.

The post Children Aid’s Society neighborhood-based programs appeared first on OUPblog.

April 9, 2020

Why we like a good robot story

Jim and Kerry Kelly live in a small town in the rural Midwest. Their sons, Ben, six, and Ryan, twelve, attend the local public school. Their school district is always short staffed. The closest town is 40 miles away and the pay for teachers is abysmal.

This year, the district’s staffing has hit a critical low: Class size will have to be huge, and there’s limited money for aides who might help with the teaching load, which will further discourage teacher applications. The school board considers accepting underqualified teachers. Parents are up in arms. Teachers and principals are stressed. The situation comes to a head at a school board meeting that drags on past midnight with shouting, frustration, threats, and anger. But, it’s too important to back off. Children’s futures are at stake.

In the next week, the superintendent finds a possible solution. The state has money available to help school boards implement technology in qualified districts. The Kellys’ town qualifies. They can receive funds to buy robots to serve in the classrooms. The robots can assume some of the teaching load, improve teaching quality, and relieve the overcrowding.

Ten years ago, this would have been unthinkable. Soulless machines educating our children? But, solutions are few, and the superintendent has found reports of success from other schools. He sells his plan well, and against all expectations, the school board agrees. The following fall, the Kelly kids, like all the kids in the district, have a robot in the classroom.

At the half-year mark, the school board reviews their decision. In six-year-old Ben’s class, the results are outstanding. Kids learn fast—pretty much as fast from the robot as from the human teacher. And, the kids like the interactions with the machines. The teacher can accomplish more and is less stressed in the process. Everyone is pleased.

But Ryan’s class, at age eleven, has a far different experience. The robot used in their class is identical to the one in Ben’s class—very human-like. By January, the kids hate it. They call it names; they hit it; they learn little from it. By midyear, it sits in a corner, scorned by students and teacher alike.

This scenario is fiction, but it reflects the real world. Many school districts are hurting for staff, and robots are entering the classroom. In Japan, Robovie speaks and teaches English with elementary school children, like Robosem does in Korea. In the United States, RUBI teaches children Finnish. Child-like robots are helping autistic children practice social interactions through imitation-teaching games.

Using robots as teachers makes some sense. Children learn much of their knowledge from others: parents, teachers, peers. Children trust that 8 × 8 = 64, that Earth is round, and that dinosaurs are extinct, not because they have uncovered these facts themselves but because reliable sources have told them so. Research shows that children are adapted to learn general knowledge from human communication. The phenomenon is known as “trust in testimony.”

But, do children trust the testimony of robots? Does it matter if the robot behaves, responds, or even looks like a human? If children learn from a robot, do they learn in the same way they learn from a human teacher? Excellent questions.

Research shows that when children as young as preschool age learn from other people, they monitor their informants’ knowledge, expertise, and confidence. They remember whether a person has given them accurate information in the past. They also monitor an informant’s access to information: Did she see the thing she is telling me about? They attend to the person’s qualifications: Is he a knowledgeable adult or a naïve child?

Surprisingly little is known about how and if children learn from robots. Because robots are machines, children could see them as infallible, like calculators or electronic dictionaries. If so, they might accept any information from a robot without considering if it is accurate. Or, children might see robots as a more fallible machine: a toaster that burns the toast, a virtual assistant that can give wrong or even outlandish answers or an alarm clock that goes off in the middle of the night. If so, they might resist a robot’s teachings.

Young children clearly can and do learn from robots, and they are appropriately choosy about the sort of robot teachers they accept. Research also shows that young children are more likely to learn from and accept robot teachers that are older children—just like in Ben Kelly’s first grade classroom—and older children are less likely, even unlikely, to do so—like in Ryan Kelly’s sixth grade classroom.

Isaac Asimov’s book, I, Robot, is primarily about morality and robotics: how robots interact with humans for good or evil. Most of the stories revolve around the efforts of Dr. Susan Calvin, chief roboticist for the fictional U.S. Robotics and Mechanical Men, Incorporated (USRMM), the primary producer of advanced humanoid robots in the world. She worries about aberrant behavior of advanced robots, and she develops a new field, robopsychology, to help figure out what is going on in their electrical (“positronic”) brains.

All robots produced by USRMM are meant to be programmed with the “Three Laws of Robotics:”

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.But in Asimov’s stories, flaws are found in the robots and their prototypes. These lead to robots imploding, harming people, and in one key case, killing a man.

I, Robot stories have spawned numerous spin-offs, continuations, and commentaries. A 2004 episode of The Simpsons (titled “I, D’oh Bot”) featured a robot boxer named Smashius Clay. Smashius, self-defeatingly, follows all of Asimov’s three laws and loses to every human he fights.

The Twentieth Century Fox 2004 film, I, Robot, starred Will Smith as detective Dell Spooner of the 2035 Chicago police department. Dell investigates a murder of the roboticist Dr. Alfred Lanning, which may have been at the hand of a USRMM robot.

Currently, robots like Robovie (or NAO or RUBI or other robots designed to interact with adults or with children) don’t have moral codes programmed in. But then, they also don’t have anything like full positronic machine intelligence. Conversely, we don’t have laws or codes about how to treat robots. For example, should a really human-like robot have rights? In November 2017, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia granted a very human-looking robot, Sophia, citizenship. This set off an uproar about rights among women in Saudi Arabia. For example, Saudi women must veil their faces when they are in public; Sophia appeared in public and on TV without a veil.

Researchers, robot designers, parents, and teachers have become increasingly concerned that interactions with robots will promote antisocial behaviors. A hitchhiking robot who traveled a bit around Europe, taking pictures and carrying on conversations with other travelers, was vandalized and destroyed after several extended weeks in the United States. And, it’s easy to imagine a world where robots displace humans from jobs and so are attacked and sabotaged by those they’ve displaced.

Research suggests that antisocial behaviors toward robots can be reduced by modifying the robots. Preschool children in a classroom comforted a robot with a hug and protected it from aggression when it started to cry after being damaged or played with too roughly. At least one study has shown that younger children say a robot should be treated fairly and should not be psychologically harmed after having conversed and played with the robot for fifteen minutes.

Every year, robots become a larger part of our lives. You can find robots in malls, hotels, assembly lines, hospitals and, of course, research labs. The National Robotics Initiative foresees a future in which “robots are as commonplace as today’s automobiles, computers, and cell phones. Robots will be found in homes, offices, hospitals, factories, farms, and mines; and in the air, on land, under water, and in space.”

And robots are becoming more and more present in the lives of children. They are already teaching children in classrooms and helping them in hospitals. Robovie is just one of many robots that have been manufactured in the last few years designed to be used with children–created to play games, answer questions, read stories, and even watch children unsupervised.

This unbridled production of hopefully child-friendly robots certainly needs more research. But, it’s clear that in some ways and at some ages children can successfully learn from robot teachers who actively interact with them.

Featured Image by Andy Kelly from Unsplash

The post Why we like a good robot story appeared first on OUPblog.

April 8, 2020

Keeping social distance: the story of the word “aloof” and a few tidbits

It is amazing how many words like aloof exist in English. Even for “fear” we have two a-formations: afraid, which supplanted the archaic afeard, and aghast. Aback, aboard, ashore, asunder—a small dictionary can be filled with them (but alas and alack do not belong here). The model is productive: consider aflutter and aglitter. One feature unites those words: they cannot be used attributively. Indeed, an asunder man and an astride rider do not exist. The prefix a- in such words usually goes back to an (as in amiss) or of (as in anew, across, afar, and their likes), and it feels at home even when attached to foreign roots: agog, for example, is French. But, as usual, caution teaches us not to generalize. Along derives from Old Engl. andlang, whose original meaning was “complete from end to end; lengthwise” (as is still obvious in German ent-lang). Occasionally we run into opaque formations. For instance, akimbo is a crux, for what is kimbo? At one time, I devoted an essay to this word: see the post for February 11, 2009.

In the past, nautical terms with a- enjoyed some popularity. One of them is aloof. I’ll borrow my explanation of this word from Walter Skeat’s dictionary. Aloof is traceable to on loof, corresponding to Dutch te loef “to windward”; the phrase loef houden means “to keep to the windward,” which is close to Engl. keep aloof, that is, “to keep away” (originally, from the leeward shore or rock; lee means “shelter”). This brings us to loof or luff, whose origin is less clear, but here again Skeat’s etymology looks convincing. His definition of luff ~ loof is “to turn a ship toward the wind,” and he glosses Middle Engl. lōf as “a contrivance for altering a ship’s course.” In Older Dutch, loef ~ loeve meant “thole,” that is, “a pin in the gunwale of a boat” and “windward side.” Middle Engl. lōf seems to have been a sort of large paddle, used to assist the helm in keeping the ship right. Probably named from the resemblance of a paddle to the palm of the hand; cf. Lowland Scottish loof, Icelandic lófi, Gothic lofa “palm of the hand.” I have expanded Skeat’s abbreviations and refrained from citing a few other cognates. The similarity between a paddle and the palm of the hand is obvious. Thus, keep aloof has a nautical origin, but in etymology, one word leads to another, and the chain may go on and on. Middle Engl. lōf, a central link in the chain, merits discussion.

A sailing ship keeping to windward. Windward Tilt by Damian Gadal. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

A sailing ship keeping to windward. Windward Tilt by Damian Gadal. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.This word has curious congeners (cognates): Russian lapa “paw” (the same in several other Slavic languages), Latvian lâpa, Lithuanian lópa “paw,” and many other forms in various languages (but, apparently, not in Classical Greek, for the sense of lôpē “clothes, apparel” is hard to connect with “a flat object,” though attempts in this direction have been made; the English noun lap is a possible, but uncertain cognate of Greek lobós “lobe”). I am coming to the climax of this digression. Middle Engl. lōf may be the historical root of glove. This word has been known since Old English, where it had the form glōf, corresponding exactly to Old Icelandic glófi. The word is opaque, unless we agree that its g- is the remnant of a prefix (then the original form was ge-lōf).

Did the Middle English lōf look like a paddle in this canoe? Image by thatsphotography from Pixabay.

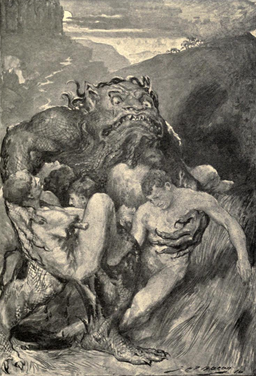

Did the Middle English lōf look like a paddle in this canoe? Image by thatsphotography from Pixabay. Grendel, his glove concealed, on his way to his last dinner. Illustration from Hero-myths & legends of the British race by John Henry Frederick Bacon. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Grendel, his glove concealed, on his way to his last dinner. Illustration from Hero-myths & legends of the British race by John Henry Frederick Bacon. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Many Old Germanic words of obscure origin begin with gl-, gn-, gr-, bl-, and br-. If we separate g- and b- (and assume that they are the stubs of ancient prefixes), the obscurity may disappear. Some such cases are easy: for example, German bleiben “to remain,” gleich “similar’, Glück “good fortune, luck,” and Gnade “mercy” have been attested with bi ~ be-, gi ~ ge-. They lost the unstressed vowel of the prefix and now display indivisible pseudo-roots beginning with bl-, gl– and gn-. But glove has never occurred with ge-, so that the etymology dependent on the existence of an ancient prefix is bound to remain guesswork. In the Scandinavian area, quite a few nouns and adjectives have been analyzed along the lines, suggested above, and almost all the proposed etymons have been refuted. However, so far, no one has disproved the idea of the ancient g(e)-love. To be sure, in linguistic reconstruction, the same principle reigns supreme as in any other discussion: it is the duty of the proposer to offer arguments for the hypothesis in question, rather than for the opponent to refute them (onus probandi). In any case, the dismemberment of glove looks tempting.

Glōf is a famous word in the history of English, because it occurs in a critical passage in Beowulf. The monster Grendel ravages the Danish king’s palace (mead hall). He comes to the place at night, grabs twelve sleeping warriors, and devours them. He has a glōf “huge and awesome,” apparently, for storing up his prey. But in the unforgettably vivid scene of Beowulf’s fight with Grendel, no glōf is mentioned. Beowulf remembers this appurtenance after he returns home and recalls the battle in the presence of his king. Grendel was not in the habit of leaving tidbits for dessert, so that this detail must have been a late addition to the description given in the first half of the poem. In any case, Grendel’s glōf could not be a glove; it was rather a pouch or a bag. Yet Modern Engl. glove means what it does, and Icelandic glófi means the same.

Did Grendel’s glove look approximately like this? Baseball glove, 1904. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

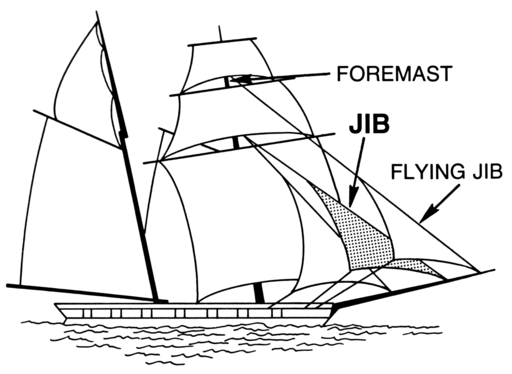

Did Grendel’s glove look approximately like this? Baseball glove, 1904. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.To return to the beginning of this post: keep aloof is a nautical phrase. As pointed out above, many English phrases have a similar origin. Today, I’ll mention only one more. How do you recognize a person at a distance, someone who keeps aloof in the direct sense of the word? If your eyesight is sharp, you do so by the jib of his or her face, that is, by the person’s appearance. I owe my explanation of the idiom (though all good dictionaries say more or less the same) to the excellent journal The Mariner’s Mirror. In time of war, an enemy’s ship, we read, was recognized by the cut of her jib (the foremost sail of a vessel). In a 1740 text, it is said that the natives of Central America recognized Europeans by their jib, staysails, and steering sails, the latter of which they seldom or never set. The editor of the volume added the following to the author’s note: “The origin of the expression cannot have been much earlier than the date referred to (1740), for jibs had then but recently come into general use in full-rigged ships. The phrase seems to have become common during the Great French Wars, there being a decided difference between French and English cut jibs. The English jib was, I think, cut fairly high in the clue, while the French jib had its clue close down to the bowsprit.” This was written in 1912. Clue (or clew) means “corner of a sail to which tacks and sheets are made fast.” The editor guessed well: the OED has no citations of the idiom prior to 1823.

For those who find themselves at sea only figuratively: this is what a jib is. Image in the public domain courtesy of Pearson Scott Foresman. Via Wikimedia Commons.

For those who find themselves at sea only figuratively: this is what a jib is. Image in the public domain courtesy of Pearson Scott Foresman. Via Wikimedia Commons.Have you ever seen or heard the word foy “a parting entertainment by or to a wayfarer”? Don’t worry: hardly anyone knows it. But you certainly know what it means to take French leave. This is what I will now do, but, by way of giving you a parting entertainment, I’ll refer to my post on this idiom (May 22, 2019: “Disbanding the etymological League of Nations”).

Keep aloof and healthy!

Feature image credit: Photo by Negative Space via Pexels.

The post Keeping social distance: the story of the word “aloof” and a few tidbits appeared first on OUPblog.

The city will survive coronavirus

In a recent essay, New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman asked “Can City Life Survive Coronavirus?” It seems an apt question in this extraordinary time of mandated retreat from public life. City streets and spaces normally teeming with people are nearly deserted now, evoking scenes from a Terry Gilliam film. In an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19 we have shut down the sites where the rituals of daily urban life unfold, “third places” like cafes and bars and community centers. We are increasingly isolated in our homes, turning even Manhattan into something akin to a suburban cul-de-sac.

“Pandemics are anti-urban,” writes Kimmelman, “preying on our human desire for connection.” This is true, of course, in the sense that social distancing and de-densification (surely a candidate for word of the year) are among the only effective measures to keep a contagion from spreading. We have little choice but to isolate ourselves from one another if we are to stop this disease, despite the rolling economic train wreck it has triggered.

But to fear that urban life might not survive the current pandemic flies in the face of history. Cities have been destroyed throughout history—infested, infected, sacked, shaken, burned, bombed, flooded, starved, irradiated, poisoned—and yet in nearly every case have risen again like the mythic phoenix. Even in the ancient world, cities were rarely abandoned in the wake of a catastrophic event. There was, of course, Pompeii, buried forever by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius; Monte Albán, near Oaxaca in modern Mexico, was crushed for good by the Spaniards; and in the Xingu region of the Brazilian Amazon, a vast network of quasi-urban settlements that flourished 1,500 years ago mysteriously vanished and was quickly reclaimed by jungle. Jared Diamond describes the early settlements on Easter Island and Norse Greenland that lost resilience, declined, and eventually died out. The mythic city of Atlantis has yet to be found, let alone lost.

But these are history’s exceptions, not the rule. Even the storied destruction of Carthage by the Romans after the Third Punic War was not permanent. The Centurions may have leveled the city and rendered it barren. But the Romans themselves resurrected the city during the reign of Augustus, eventually making Carthage the administrative hub of their African colonies.In more recent times, too, rare is the city that has not bounced back from trauma. Atlanta, Columbia, and Richmond all survived the devastation wrought by the American Civil War and remain state capitals today. Chicago emerged stronger than ever following the 1871 fire, as did San Francisco from the earthquake and fires of 1906. We still have Hiroshima and Nagasaki, despite the horrors of nuclear attack. Warsaw lost 61 percent of its 1.3 million residents during World War II, yet surpassed its prewar population by 1967. Banda Aceh has regained the position it held prior to its devastation during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Does anyone doubt that Kabul and Kandahar, or Baghdad and Basra, will also persist once protracted fighting finally comes to a close? Or, Kimmelman’s fears aside, that New York will not soon again be teeming with residents and tourists alike?

Just why this should be so, especially as the mechanisms for destruction have multiplied, is not entirely obvious. Why do cities get rebuilt? How do modern cities recover from disaster?

Urban disaster, like urban resilience, takes many forms, and can be categorized in many ways. First, there is the scale of destruction, which may range from a small single precinct to an entire city or an even larger area. Second, such disasters can be viewed in terms of their human toll, as measured by deaths and disruption of lives. Third, these destructive acts can be evaluated according to their presumed cause. Some result from largely uncontrollable forces of nature, like earthquakes and tsunamis; others from combinations of natural forces and human action, like fires and pandemics; still others result from deliberate human will, like the actions of a lone terrorist. Finally, there are economic disasters—triggered by demographic change, a major accident, or an industrial or commercial crisis—that may contribute to massive population flight, diminishing investment in infrastructure and buildings, and perhaps even large-scale abandonment.

Although we have many case studies of post-disaster reconstruction in individual cities, until recently few scholars have attempted cross-cultural comparisons, and even fewer have attempted to compare urban resilience in the face of natural disasters, for instance, with resilience following human-inflicted catastrophes. By studying historical examples, however, we can learn the pressing questions that have been asked in the past as cities and their residents struggled to rebuild.

One of the most important questions to consider is that of recovery. What does it mean for a city to recover? The broad cultural question of recovery is more than a problem of “disaster management,” however daunting and important that may be. Are there common themes that can help us understand the processes of physical, political, social, economic, and cultural renewal and rebirth? What counts as urban resilience? Whose resilience matters?

Many disasters may follow a predictable pattern of rescue, restoration, rebuilding, and remembrance, yet we can only truly evaluate a recovery based on the specific circumstances. It matters, for instance, that the Chinese central government viewed the devastation of the earthquake in Tangshan in 1976 as a threat to national industrial development, and that the contending governments of postwar Berlin viewed the re-emergent city as an ideological battleground. Jerusalem, traumatized more than perhaps any other city in history, has undergone repeated cycles of destruction and renewal, but each time the process of reconstruction and remembrance has been carried out in profoundly different ways.

Thus, it is no simple task to extract common messages, let alone lessons, from the wide-ranging stories of urban resilience. Yet several themes stand out and can help us ask better questions during and after the current pandemic:

Narratives of resilience are a political necessity. The ubiquity of urban rebuilding after a disaster results from, among other things, a political need to demonstrate resilience. In that sense, resilience is primarily a rhetorical device intended to enhance or restore the legitimacy of whatever government was in charge at the time the disaster occurred. Regardless of its other effects, the destruction of a city usually reflects poorly on whomever is in power. If the chief function of government is to protect citizens from harm, the destruction of densely inhabited places presents the greatest possible challenge to its competence and authority.

Cultivation of a sense of recovery and progress therefore remains a priority for governments. Of course, governments conduct rescue operations and channel emergency funds as humanitarian gestures first and foremost, but they also do so as a means of saving face and retaining public office.

How will the management, or mismanagement, of a pandemic impact the re-electability of leaders?

Disasters reveal the resilience of governments. In the aftermath of disaster, the very legitimacy of government is at stake. Citizens have the opportunity to observe how their leaders respond to an acute crisis and, if they are not satisfied, such events can be significant catalysts for political change. Even something as minor as a snowstorm can threaten or destroy the re-election chances of a mayor who is too slow in getting the plows out.

After the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City, residents saw that the existing bureaucracy lacked the flexibility and the will to place the needs of homeless citizens first. By criticizing the government’s overriding interest in calming international financial markets, grass-roots social movements gained new primacy.

“Mexico City Earthquake, September 19, 1985. Eight-story frame structure with brick infill walls broken in two” by US Geological Survery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Mexico City Earthquake, September 19, 1985. Eight-story frame structure with brick infill walls broken in two” by US Geological Survery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.At an equally basic level, a sudden disaster causes governments to exercise power quite directly. In postwar Warsaw, for instance, both the reconstruction of the Old Town and the creation of modernist housing estates in adjacent areas depended on the power and flexibility assumed by a strong central government. Rebuilding is often economically necessary to jump-start employment and spending, and thereby casts in bold relief the values and priorities of government.

What will the varying degrees of aggressiveness in curtailing urban movement tell us about the relative advantages of democracy and autocratic decree-making during a pandemic?

Narratives of resilience are always contested. The rhetoric of resilience is never free from politics, self-interest, or contention. Narratives focused on promises of progress are often bankrolled by those who control capital or the means of production and are manipulated by media pundits, politicians, and other voices that carry the greatest influence. There is never a single, monolithic vox populi that uniformly affirms the adopted resilience narrative in the wake of disaster. Instead, key figures in the dominant culture claim (or are accorded) authorship, while marginalized groups or peoples are often ignored. No one polled homeless people in Manhattan about how we should think about September 11.

How will those least likely to have capacity to safely self-isolate react to the spatial privileges of the wealthy and powerful?

Local resilience is linked to national renewal. A major traumatic event in a particular city often projects itself into the national arena. Recovery becomes linked to questions of national prestige and to the need to re-establish standing in the community of nations. In that sense, resilience takes on a wider ideological significance that extends well beyond the boundaries of the affected city. A capital city or a city that is host to many national institutions is swiftly equated with the nation-state as a whole. When a Mexico City, a Beirut, a Warsaw, or a Tokyo suffers, all of Mexico, Lebanon, Poland, or Japan feels the consequences.

“Tokyo, 1945” by Ishikawa Kouyou. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

“Tokyo, 1945” by Ishikawa Kouyou. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsWhat will the globality of a pandemic mean for the usual impulse to view disasters through the lens of nationalism?

Resilience is underwritten by outsiders. Increasingly, the resilience of cities depends on political and financial influences exercised from well outside the city limits. Usually, in a federal system, urban resilience depends on the emergency allocation of outside support from higher levels of government. In the United States, that holds true for every federally designated “disaster area”–whether caused by a hurricane, snowstorm, heat wave, power outage, earthquake, flood, or terrorist act.

Sometimes, where recovery is costly and local resources are meager, support comes from international-aid sources (often with strings attached, in the form of political agendas of one sort or another). Chinese leaders recognized this potential in 1976 and refused to let international-aid organizations get involved in the rebuilding of Tangshan–a decision that may well have cost many lives. In contrast, the reconstruction of Europe after World War II under the Marshall Plan was generally well received. The global influx of humanitarian aid to assist the Iranian city of Bam after the 2003 earthquake entailed far more than reconstruction of a vast mud-brick citadel; it also carried implications for rebuilding international relations with Iran.

Will a global pandemic–in which “national emergencies” are near-ubiquitous and far-flung—still offer opportunities for selective interventions by outsiders?

Urban rebuilding symbolizes human resilience. Whatever our politics, we rebuild cities to reassure ourselves about the future. The demands of major rebuilding efforts offer a kind of succor in that they provide productive distraction from loss and suffering and may help survivors to overcome trauma-induced depression. To shore up the scattered and shattered lives of survivors, post-disaster urbanism operates through a series of symbolic acts, emphasizing staged ceremonies–like the removal of the last load of debris from Ground Zero–and newly constructed edifices and memorials. Such symbols link the continuing psychological recovery process to tangible, visible signs of progress and momentum.

In the past, many significant urban disasters went largely unmarked. Survivors of the great fires of London (1666), Boston (1872), Seattle (1889), Baltimore (1904), and Toronto (1904) devoted little or no land to memorials, although each fire significantly altered the architectural fabric of its city. Hiroshima, on the other hand, built its Peace Park memorial–an island of open space in what quickly became again a dense industrial city–with the full support of the American occupation forces.

How, in the aftermath of a pandemic where the death toll is high but physical damage to places may be negligible, will dramatic loss be marked?

Resilience benefits from the inertia of prior investment. In most cases, even substantial devastation of urban areas has not led to visionary new city plans aimed at correcting long-endured deficiencies or limiting the risk of future destruction in the event of a recurrence. After London’s Great Fire of 1666, architects–including Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, and others–proposed bold new plans for the city’s street network. Yet, as the urban planner and author Kevin Lynch has written, the most ambitious plans were thwarted by entrenched property interests and “a complicated system of freeholds, leases, and subleases with many intermixed ownerships.”

In New York City, reconstruction of the World Trade Center involved scores of powerful players in state and local government as well as community and professional organizations. The large number of “chiefs” led to a contentious planning and design process. It needed to accommodate public demands for open space and memorials as well as private demands to restore huge amounts of office space and retail facilities–demands driven as much by insurance provisions as by market conditions.

How will the locus of investment differ in the post-pandemic city?

Resilience exploits the power of place. Mere cost accounting, however, fails to calculate the most vital social and psychological losses–and the resultant political engagement–that are so often tied to the reclamation of particular places. No place better illustrates this than Jerusalem. For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, there is simply no replacing Jerusalem: “Men always pray at the same sites,” the religion scholar Ernest Renan observed of the city. “Only the rationale for their sanctity changes from generation to generation and from one faith to another.”

Rebuilding cities fundamentally entails reconnecting severed familial, social, and religious networks of survivors. Urban recovery occurs network by network, district by district, not just building by building; it is about reconstructing the myriad social relations embedded in schools, workplaces, childcare arrangements, shops, places of worship, and places of play and recreation.

Surely that is at the heart of the reclaiming of downtown Mexico City after the earthquake, the struggles over Martyrs’ Square in postwar Beirut, and the hard-fought campaign to retain Washington, D.C., as the national capital after its destruction in 1814. The selective reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town also perfectly captures the twin impulses of nostalgia and opportunism; its planners found a way to recall past glories and also reduce traffic congestion by building an underground highway tunnel.

As the impact of a pandemic wanes and urban life returns, which kinds of temporarily-lost places will warrant the most ardent forms of renewed affection?

Resilience casts opportunism as opportunity. A fine line runs between capitalizing on an unexpected traumatic disruption as an opportunity to pursue some much-needed improvements and the more dubious practice of using devastation as a cover for more opportunistic agendas yielding less obvious public benefits. The dual reconstruction of Chicago after the 1871 Great Fire illustrates the problem perfectly: The razed city was rebuilt once in a shoddy form and then, in reaction to that, rebuilt again with the grand and innovative skyscrapers that gave the resurrected city a bold new image and lasting fame.

“Grand Pacific Hotel after the Great Chicago Fire” by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Grand Pacific Hotel after the Great Chicago Fire” by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. The annals of urban recovery are replete with such examples where rebuilding yielded improvements over the pre-disaster built environment. San Francisco officials exploited the damage done to the Embarcadero Freeway by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake as the opportunity to demolish this eyesore and enhance the public amenities of 1.5 miles of downtown waterfront by creating a music pavilion, a new plaza, an extended trolley line, a revitalized historic ferry building and farmers’ market, and enhanced ferry service.

Shortly after a massive IRA bomb devastated parts of the city center in Manchester, England, in 1996, government officials established a public-private task force charged not only with the immediate recovery but also with longer-term regeneration. The redevelopment included new office, retail, and entertainment facilities, as well as a multilevel pedestrian plaza and a new museum highlighting urban life around the world. Most recently, rebuilding Ground Zero in New York sought to improve the area as a regional transportation hub.

Of course, disaster-triggered opportunism can just as easily work against the best interests of the affected city. Following the September 11 attacks, many downtown firms either fled New York City or established secondary operations in the suburbs–a process of decentralization that brought new growth to a number of communities at the city’s expense.

How will the aftermath of the pandemic affect larger patterns of metropolitan residential preferences?

Resilience, like disaster, is site-specific. When speaking of traumatized cities, there is an understandable temptation to speak as if the city as a whole were a victim. September 11 was an “attack on New York”; the truck bomb that destroyed the Murrah Building was the “Oklahoma City bombing”; all of London faced the Blitz. Yet all disasters, not only earthquakes, have epicenters. Those who are victimized by traumatic episodes experience resilience differently, based on their distances from those epicenters.

“Ruins of the Reichstag in Berlin, 3 June 1945” by No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Hewitt (Sgt). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ruins of the Reichstag in Berlin, 3 June 1945” by No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Hewitt (Sgt). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Even in the largest experiences with devastation–like the Tangshan earthquake–it was significant that the quake leveled vast residential and commercial areas but spared some industrial facilities, as this forced the government to consider vast new schemes for housing workers. In Berlin, especially once the postwar city was divided into zones of occupation, it mattered mightily which parts of the city had been destroyed and which regime thereby inherited the debate over how to proceed with each particular reconstruction challenge.

The site-specificity of resilience will increasingly follow a different trajectory, given the global flow of electronic data and information, which can all too easily be obstructed by a disruption at some key point in the network. When such a node is destroyed–as in the case of the Mexico City telephone and electrical substations during the 1985 earthquake–an entire country may suffer the consequences. Alternatively, the very nature of an electronic network provides redundancies and “work-arounds” that guard against a catastrophic breakdown of the system. The digital era offers tempting new targets for mayhem but also affords new possibilities for resilience.

What lessons will a pandemic—with its hotspots and its less-impacted areas—carry for the way we think about our social networks and the differential capacities of our infrastructure?

Resilience entails more than rebuilding. The process of rebuilding is a necessary but, by itself, insufficient condition for enabling recovery and resilience. We can see this most acutely in Gernika, where the trauma inflicted on the Basque town and its people by Hitler’s bombers–and Franco’s will–remained painful for decades, even after the town was physically rebuilt. Only with a regime change 40 years after the attack did citizens feel free to express the full measure of their emotional sorrow, or attempt to re-establish the Basque cultural symbols that had been so ruthlessly destroyed.

In addition, American cities have experienced major population and housing losses, sustained over a period of decades, that are comparable with the declines usually associated with some sudden disaster. Once vibrant North Carolina cities like Durham and Burlington have suffered mightily as their major industries–textile manufacturing, railroads, and tobacco processing–went into decline. Industrial Detroit has lost well over a million people since 1950, yet even much-battered cities have gained from resilient citizens, ambitious developers, and a dogged insistence that recovery will still take place.

We are not willing to let cities disappear, even if their economic relevance has been seriously questioned. National governments provide special programs like urban renewal or empowerment zones to assist particular cities, refusing to let them sink on their own. Although the effectiveness of such programs is often questioned, the will to rescue cities and spur additional economic development remains real.

Will post-pandemic cities also rapidly return to their pre-pandemic growth trajectories?

The various axioms that we’ve described can hardly cover every facet of urban resilience. We have said relatively little, for instance, about efforts to plan in advance for the possibility of disasters. Nearly every city and country makes some attempt at pre-disaster planning; civil-defense agencies prepare plans to protect civilians from floods, nuclear fallout, the effects of chemical or biological weapons, and many other circumstances. Inevitably, many such plans prove to be of limited value and have often been subject to ridicule. Whatever the merits, pre-disaster planning often exposes official priorities to provide disproportionate assistance to certain kinds of people and places, and is very revealing about the relationship between the government and the governed. Flood-control projects often pass the problem downriver; dictators often provide bomb shelters for “essential personnel” but not for average civilians; costly “earthquake-proof” buildings less frequently house those with the lowest incomes–and the list goes on. Despite the shortcomings, however, any full measure of urban resilience must take account of such efforts to mitigate disaster.

Ultimately, the resilient city is a constructed phenomenon, not just in the literal sense that cities get reconstructed brick by brick, but in a broader cultural sense. Urban resilience is an interpretive framework that local and national leaders propose and shape and citizens accept in the wake of disaster. However equitable or unjust, efficient, or untenable, that framework serves as the foundation upon which the society builds anew.

“The cities rise again,” wrote Kipling, not due to a mysterious spontaneous force, but because people believe in them. Disasters, including pandemics, ultimately provide renewed reminders of this value. Cities are not only the places in which we live and work and play, but also a demonstration of our ultimate faith in the human project, and in each other.

“Central Park Bridges” by Jet Lowe. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Central Park Bridges” by Jet Lowe. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Featured Image Credit: “Four-segment panorama of Lower Manhattan, New York City, as viewed from Exchange Place, Jersey City, New Jersey” by King of Hearts. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The city will survive coronavirus appeared first on OUPblog.

Why war stories could reinjure those affected

When my mother was born, the Federal Republic of Nigeria was less than one year old. Language barriers, and eventually death, prevented me from asking my grandparents what life under the colonial rule of the Royal Niger Company had been like, their fates twisted and tugged by the company’s board of directors in London. I wish I had been able to ask them, as my mother’s birth drew near, what the increasing internal demand for self-governance had sounded like. My grandfather was a fishmonger, but who is to say that judging the price of fish and intuiting the departure of British ships from your harbors aren’t the same thing?

More often, however, I am able to get from my mother impressions of what life was like in the old country. And occasionally she will remark offhandedly about being a teen in 1970s Nigeria when it was full of Koreans and Sri Lankans. Or how, during a civil war that brought apocalypse to her childhood, her family had fled into the forest to live for some time before finding safety.

I started writing my third novel, War Girls, because of that story. As the son of immigrants, I’m not alone in feeling this sense of wonder and enchantment at the world the previous generation inhabited.

In conversations with my Somali-American friends, my Vietnamese-American friends, my Korean-American friends, my Palestinian-American friends, there are shades of that same admixture of feelings. But another colors the underbelly of the thing. In so many of our stories—that is to say, our parents’ stories—is war. Calamity. Our parents were refugees or war orphans or collaborators or freedom fighters or witnesses to untold horrors. Sometimes their parents were. Which makes our fascination with these all the more macabre. Therein lies the plight with which so many first-generation American writers suffer: are we exploiting the trauma our parents and grandparents endured for profit or fame or whatever it is that drives a person to write a book? Are we re-injuring them?

To this day, I don’t know the answer to that question. I just know that I am drawn, as the penitent is drawn to the church sanctuary, to those stories.

Those non-Westerners—those people from places the American consciousness has refused to consider or know much about; people from places who, by dint of White intervention, have suffered through national paroxysms of intercommunal violence or political upheaval—theirs, to me, is the most interesting story. Theirs is the story I find myself looking for on the shelves of bookstores and libraries.

Perhaps those stories are being told, just not in America. They aren’t being promulgated by a publishing industry that, according to a 2019 Lee & Low Books survey, is 76% white. At the executive level, that number is 78%. At the editorial level, 85%. Among both book reviewers and literary agents, the percentage of respondents who identified as white was 80%. From those representing the storytellers to those acquiring the stories to those hired to write about those stories, the ice cream in the cone is almost entirely one flavor. Such that even those tales of that history that still feels too close to be called history are cut through with baking soda or vanilla extract or rat poison, the narcotic diluted and adulterated by the White Gaze.

Two years ago this past March, I had the privilege of seeing Uzodinma Iweala read from his latest novel, Speak No Evil. He was doing an event with Neel Mukherjee, whose catholic The Lives of Others had enacted quiet and lasting change on my spirit when I read it. They were introduced by Marlon James. All in all, to me, it was like attending the American Music Awards the year Lionel Richie, Michael Jackson, and Prince were all up for Favorite Soul/R&B Album. Before the reading started, I took my seat next to Uzodinma’s father, and we spent about twenty minutes laughing and chatting and I saw in the man so many of the familiar contradictory joys and fears contained within Nigerian parents of sons who become writers. We talked of Umuahia, where he had come from, as had my father. “Where in Umuahia?” he asked me, as though maybe one day they might have passed each other on the street or maybe attended secondary school together.

To my knowledge, the two men never met. Nor, at the time, would they have known my mother. So many of these things happen only after the dust has settled and the displaced awake on foreign shores. But I like to imagine, sometimes, their adolescent/teenaged/early adult quotidiana, their presents unexpected, their inner lives impossibly rich.

It is not always war and tragedy with them. Sometimes, it is this other thing too.

I hope I am able to remember that.

Featured Image Credit: by eko hernowo via Pixabay .

The post Why war stories could reinjure those affected appeared first on OUPblog.

April 7, 2020

Inspirational TV shows to watch during this pandemic

There are many ways people are passing time with staying home during the pandemic. Some are taking up new hobbies. Some are exploring virtual museums. Some may even be preparing for a neighborhood sing-along out their windows. But many people are turning to television to provide entertainment, comfort, and/or escape. Since the late 1990s, as television offerings have generally expanded, so too has there been a boom in television that explores the ultimate meaning, especially shows in which the answers to the big questions of life are mired in tension and doubt. The following shows use the tropes, stories, and themes of religion to explore the tensions among what we do to each other, what we owe to each other, and what it all really means. These are questions that a lot of us are asking with renewed necessity.

Battlestar Galactica (Syfy, miniseries 2003, series 2004-2009) starts with catastrophe and keeps pushing its characters to the brink, distilling their humanity and highlighting the importance of connection throughout. Set in a sci-fi world in which humans worship Hellenic deities and human-like robots called Cylons wage a holy war against them in the name of their singular God, the series broke new ground by placing questions of religious belief at the core of a grounded and complex political drama. Influenced by—but not devoted to—the War on Terror, Battlestar Galactica worked through both immediate and eternal questions of meaning in the safe displacement of reality allowed by science fiction and the niche audience of a cable channel. The monotheism-polytheism divide shaded much of the major dramatic arcs and shaped the culmination of the story, but at its core the question of faith was more about the people we believe in than the god(s) we pray to.

The Leftovers (HBO, 2014-2017) presented viewers with a world in which a kind of a rapture—the “Sudden Departure” of two percent of the human population—happened years ago and the titular leftovers sought meaning in this new reality. Some characters redoubled their devotion to their traditional faith, some joined one of the many cults that cropped up after the event, some merely tried to survive their grief, and others joined the “Guilty Remnant” to present a continuous reminder and confrontation of the event. Later seasons expanded the scope to include the residents of Jarden, Texas, a new mecca for spiritual tourists because no one was taken from the town in the Sudden Departure, and the show leaned even further into the cruelty and hope, weirdness and familiarity, faith and faithlessness explored through the characters’ ongoing quest to find meaning when the universe has made you feel meaningless.

Rectify (SundanceTV, 2013-2016) used its Southern setting to weave one of the most nuanced representations of devout White Christianity into its story of a wrongfully convicted man released after nineteen years on death row. Praised by critics as “meditative” among other plaudits, Rectify was deeply engrossed in the inner lives of its characters, especially its laconic lead, Daniel (Aden Young). Throughout the first season, Daniel’s freedom from jail leads to intense isolation as the world and his family had moved on without him, but through connecting with his step-brother’s wife, Tawney (Adelaide Clemens) and her faith, Daniel briefly finds peace. The salvation offered through faith and Tawney’s kindness present Christianity as a true solace for some and a thoroughly entrenched part of Southern culture. Although the focus somewhat fades from a specific religion as the show progressed, the questions that religion seeks to answer persist and continue to yield deep explorations of human connection and purpose.

The Good Place (NBC, 2016-2020) is your best option if you want a show that tackles questions of religion, faith, human nature, and the design of the universe head-on—in contrast to the shows discussed above that weave it in through genre conventions or setting—and that will make you laugh while doing it. Set in an afterlife that has a “good place” where you will get everything you could ever want and a “bad place” where you will be tortured by demons for eternity, the cosmic design of The Good Place takes the familiar notions of Heaven and Hell and gives them contemporary twists such as: no one in the good place being able to swear, bad place tortures often involving the worst aspects of social media, and a character who is not-a-girl and not-a-robot but knows everything and can do almost anything to help you find your reward or be tortured. Throughout its four seasons, The Good Place used moral philosophy, religious concepts, and character development to answer the question of what we owe each other simply: we owe each other to try.

Although these four shows present an interesting constellation of television programs that feature religion as a means of tackling the big questions of existence and humanity, there have been many others. Approaches range from the comforting episodic drama of Touched by an Angel and 7th Heaven to the fantasy stories featuring battling angels and demons like on Supernatural and Good Omens or the individual religious paths explored on Jane the Virgin, Ramy, and Enlightened. For a topic that was once seen as verging on taboo, religion on television has become a fascinating and varied subject of popular entertainment over the last 25 years, plenty to keep anyone engaged with these stories, characters, and questions while facing more time at home.

Featured image by Jorge Zapata via Unsplash

The post Inspirational TV shows to watch during this pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

Untold stories of the Apollo 13 engineers

Late on 13 April 1970, the night shift had started in Houston’s Manned Spaceflight Center. Engineers tried to sift through reams of odd data coming about the Apollo 13 spacecraft, from instrument readings to the confused reports from three astronauts. It looked like they were rapidly losing their oxygen supply. “First of all, we thought we’d boil it down to something simple and obvious,” engineer Arnold Aldridge recalled later. He made a phone call to an especially insightful young engineer, John Aaron.

Aaron recalled being at home, winding down after a long shift at Mission Control. Aldridge told him they were facing an instrument problem or “flaky readouts”—there was no way data this extreme could be real – they couldn’t lose the mission’s stored oxygen so quickly. Aaron asked to hear the numbers from various instruments, one at a time, over the phone. “That’s not an instrumentation problem,” he told them. Thinking back on it, he saw his distance from the Control Center as good fortune – he could see the entire forest of information. “You guys are wasting your time,” he said. “You really need to understand that the [spacecraft] is dying.”

As word spread through the ranks, everyone who could possibly help swarmed to the center. Aldo Bordano, in his early twenties, remembers the commute. “All of a sudden, it was about midnight, it was just a line of cars with their lights on. … We’d all gotten called in—all three shifts.” They efficiently filled the parking lot outside Mission Control. “It was a real eerie moment,” he said. “There might have been two hundred of us turning our cars off and walking in at the same pace. Nobody said a word to the guy on the left or the guy on the right. We just went to our stations.”

Scores of engineers started their calculations. With the spacecraft’s fuel cells mostly useless now – just like astronauts, they required oxygen to run – the engineers had to conserve every bit of electrical power. They knew how much they would need, with luck, in the mission’s last minutes. They would need enough juice to safely guide the crew capsule into Earth’s atmosphere. Working backward from that goal, to every minute of the return path, they ruthlessly budgeted the mission’s electricity. “We had to cut our energy consumption in half in order to make it back home,” engineer Henry Pohl recalled. “To do that, you’ve got to turn every heater off that you don’t absolutely have to have.” The spacecraft was going to get very cold, and shivering astronauts were just one of many worries.

(14 April 1970) Back up crew and flight controllers monitor the console activity in the Mission Control Center. At the time of this picture, the Moon landing had been cancelled, and the crew were in trans-Earth trajectory attempting to bring their stricken spacecraft back home.

(14 April 1970) Back up crew and flight controllers monitor the console activity in the Mission Control Center. At the time of this picture, the Moon landing had been cancelled, and the crew were in trans-Earth trajectory attempting to bring their stricken spacecraft back home.Pohl oversaw the command module’s little thruster rockets. “I calculated . . . how cold the [thrusters] were going to get, and I gave myself four degrees above freezing on it,” he said, recalling his small margin for error. If the propellants froze, it wouldn’t matter how much electrical power the astronauts had at their disposal. They would be close enough to see the welcoming Pacific Ocean from space but unable to maneuver for re-entry, either burning up or bouncing off the atmosphere and sailing helplessly away. In the end, Pohl says his propellant almost froze— only 2˚ Fahrenheit from disaster. “We cut those margins pretty dad-gum close.”

NASA had the astronauts move from the crippled command module into the lunar lander for most of the journey back to Earth, since the lander had working batteries and a separate oxygen supply. While the lander’s emergency role is sometimes portrayed as a desperate, last-minute idea, the engineers had game-planned it in advance. It was simply one of thousands of unlikely yet carefully scripted horror stories. Engineer Cynthia Wells recalled one of her earlier NASA assignments, a “lifeboat” study for the lunar lander. “Everybody laughed at it,” she said of this unlikely work, years before the Apollo 13 mission. But just in case, her group ran the numbers.

In the wake of the miraculous survival of the mission, there was surprisingly little finger pointing. A stack of small errors had caused an oxygen tank to explode in flight. (Centrally, a miscommunication between the Apollo launch facilities and the tank manufacturer meant a little heating wire inside the tank had received way more voltage than it could handle prior to launch.) Mainly, everyone involved felt fortunate. The tank could have easily blown two days later than it did, with the lander and two astronauts on the Moon and a lone astronaut left in an expiring, powerless ship in lunar orbit. The astronauts would have expired a quarter million miles from Earth.

As it was, the engineers had just enough time to work the myriad, entangled problems and get them home. The triumph of Apollo 13 highlighted the work of engineers for the general public like no other mission. With the astronauts mainly just shivering for a few days, broadcasts had to at least attempt covering technical challenges, clever emergency fixes, and the years of careful planning that had paid off.

Yet, a few of the engineers, like Marlowe Cassetti, have always wondered if it hurt the space program. “I think there was a whole mood that changed in Washington,” Cassetti said. “Apollo 13 scared the management and they thought it was way too risky.” The public too was getting the idea that space was less romantic and less full of wonder than they’d assumed in 1958, at the inception of NASA. Space seemed dangerous, and spaceships were not sleek and sexy; they were claustrophobic and uncomfortable. Life in space was razor stubble, messy hair, urine bags, and nausea. And even in a nail-biter like Apollo 13, journalists and audiences had to wade through drifts of technical terms and acronyms.

As we once again plot courses to the moon and beyond, Apollo 13 serves as a good reminder: Space is hard. It comes with hiccups. And even our best-computed plans will, sooner or later, require nimble, fresh-eyed problem-solving and pre-planned alternate routes.

Featured image: (16 April 1970) Feverish activity in the Mission Control Center during the final 24 hours of the problem-plagued Apollo 13 mission. Image courtesy of NASA.

The post Untold stories of the Apollo 13 engineers appeared first on OUPblog.

April 6, 2020

Six jazz movies you may not know

The film industry started making jazz-related features as soon as synchronized sound came in, in 1927: “I’m gonna sing it jazzy,” Al Jolson’s Jack Robin optimistically declares in the pioneering talkie The Jazz Singer, before taking off on Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies.” (He gets closer to the jazzy mark whistling a quasi-improvised chorus of “Toot Toot Tootsie.”) Since then there have been dozens of movies focusing on jazz, or at least working it into the main plot.

Such jazz stories have never been easier to access, thanks to classic-movie cable channels, archival DVD and Blu-Ray reissues, and streaming video services. The six films listed below are crucial to understanding the development the music genre. Many others are available here.

Swing High, Swing Low

Jazz movies really get rolling after Benny Goodman’s band breaks through in 1935, kicking off the decade-long “swing era.” Two years later, at Paramount, light romantic lead Fred MacMurray (who’d later play goofy dads and oily villains) starred as a horn man in two romances, Champagne Waltz (where his jazz shakes up old Vienna) and Swing High, Swing Low, directed by Mitchell Leisen. In that one MacMurray is Skid Johnson, feckless trumpet player bumming around the Panama Canal Zone, and trying to make time with Carole Lombard, who finds the trumpet boorish—until she hears Skid’s suave and sensual wah-wahs. Many later movie trumpeters would similarly warm women’s hearts with a tender or assertive solo. But then Skid’s off to fame in New York, and vulgar high notes, high living, and the wrong woman, and his lip starts to go—looking ahead to Kirk Douglas’s decline (and last-minute recovery) in 1950’s Young Man with a Horn.

Broken Strings

The Jazz Singer spawned a host of knockoffs, for decades: tales in which a tradition-minded father rejects his son’s innovative music, as an affront to everything the old man stands for. One of the more entertaining is the one-hour, decidedly low-budget Broken Strings, directed by Bernard B. Ray in 1940. It transfers that Jewish-American story to the world of the African American bourgeoisie, where some folks thought jazz a little too rowdy, rough-edged and redolent of down home to be respectable. The grave Clarence Muse portrays a classical violinist doubly distressed when an accident leaves him unable to play, and his student son Johnny steps in to support the family by swinging on jazz fiddle. You can’t fault Johnny’s ideals—aspiring, in his big speech, “to play like a bird flies—this way and that, up and down, winging and swinging through the air.” Out of respect for dad he pledges to give jazz up, but when Johnny breaks two strings playing a mazurka during a talent contest, he has to improvise his way out of trouble, making a believer out of Dad.

The Fabulous Dorseys

The 1950s was the (first) golden age of the jazz biopic: life stories brought to the screen with liberal amounts of hokum. In the 1944 Benny Goodman vehicle Sweet and Low-Down, a romance between a young musician from the Chicago slums and a New York heiress echoes events from Goodman’s own life. But the first proper jazz biopic was the dowdy The Fabulous Dorseys from 1947, about battling brother bandleaders Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey; it was directed by Alfred E. Green. The nonsense and inaccuracies come thick and fast. Its saving grace: squabbling siblings Tommy and Jimmy play themselves, and their mutual antagonism and clashing personalities and vividly depicted. In the end, a big (fictitious) New York concert brings them back together—if only for a night.

Louis Armstrong-Chicago Style

No jazz great appeared in more movies than the hugely influential singer/trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who died in 1971. By then his colorful life story was well known, and while a character based on him appears in the 1942 feature Syncopation, the closest we’ve come to an Armstrong biopic is this little-remembered TV movie directed by Lee Philips set in 1931, in which Louis is busted for pot possession (that actually happened in 1930) and leaned on by gangsters. In the movie (unlike life), Armstrong is no fan of marijuana, but stage and screen personality Ben Vereen plays him like he’s perpetually stoned, breaking into unmotivated guffaws and gyrating every which way while playing his horn (and singing “When the Saints Go Marching In,” years too early). Reno Wilson’s uncanny impersonation of 1931 Pops, in the 2019 Buddy Bolden biopic Bolden, puts Vereen’s clowning to shame.

The Gig

Playwright Frank D. Gilroy (The Subject Was Roses) wrote and directed a few films, including 1985’s The Gig, about an amateur dixieland band that lands a two-week engagement at a resort hotel in upstate New York. For these once-a-week jammers it’s a dream gig. But they need to hire a professional bassist (Cleavon Little) who’s a little above them, the patrons balk at rowdy music, and then there’s a nasty, temperamental singer. Gilroy knows his craft, and all the complications arrive right on the beat, as in a good dixieland band, where all the pieces mesh in good time. The only real musician in the cast, cornetist Warren Vaché, is excellent as a talented soloist with zero ambition—he’d rather hang with the guys (and work for his father-in-law) than turn pro.

The Deaths of Chet Baker

The 2010s was the second great decade for jazz biopics, with movies about Joe Albany (Low Down), Bessie Smith (HBO’s Bessie), Miles Davis (Miles Ahead), Buddy Bolden (Bolden) and the jazz-related but unclassifiable Nina Simone (Nina). Seven years before his 2016 Chet Baker biopic Born to Be Blue starring Ethan Hawke, director Robert Budreau had warmed up to his subject with the eight-minute short The Deaths of Chet Baker, which lays out three theories of how the singing trumpeter came to be found dead on the pavement under his Amsterdam hotel window in 1988: jumped, pushed, or fell. Baker is played by character actor Stephen McHattie, whom Budreau would tap to play Chet’s disapproving dad in Born to Be Blue: McHattie’s craggy face foretells what would become of young Chet’s boyish good looks, after decades of bad choices and hard living.

This half-dozen barely scratches the surface, needless to say; jazz movies encompass not just biopics, romances, musicals and “race movies,” but also comedy, science fiction, horror, crime and comeback stories, and modernized Shakespeare—stories that parallel jazz itself in their stylistic diversity.

Featured Image Credit: by Jorge Zapata via Unsplash

The post Six jazz movies you may not know appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers