Oxford University Press's Blog, page 152

April 21, 2020

Earth Day at 50: conservation, spirituality, and climate change [podcast]

This week, the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. At the behest of Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, an estimated 20 million people across the United States gathered to raise awareness for environmental protection and preservation on 22 April 1970. This first Earth Day was a catalyst for the modern environmental movement; by the end of the year, the Environmental Protection Agency had been created, and the Clean Air, Clean Water, and Endangered Species Acts were all passed in Congress by 1973.

In recent years, religious figures from Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to Pope Francis have preached against the degradation of the earth, bringing the ideals of environmental protection and conservation to new audiences. In addition to early conservation history, this intersection of spirituality, ethics, and environmental issues is the focus of today’s episode of The Oxford Comment.

To speak on these topics, and, of course, our collective, ongoing struggle against climate change, we are joined by Ted Steinberg, author of Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History, Belden Lane, author of The Great Conversation: Nature and the Care of the Soul, Lufti Radwan of Willowbrook Farm, and Buddy Huffaker, executive director of the Aldo Leopold Foundation.

Featured image credit: US President Theodore Roosevelt and nature preservationist John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, on Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park, 1906. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Earth Day at 50: conservation, spirituality, and climate change [podcast] appeared first on OUPblog.

COVID-19 and employment law in the UK

The last couple of weeks have seen a raft of new legislation in the United Kingdom, hurriedly passed to deal urgently with the coronavirus situation. It has clearly been drafted quickly, with guidance that goes well beyond the legislation, and so this has led to some confusion as to what exactly the law now says.

There are four main areas of legislation that affect employment law. There is the requirement to work from home. In addition, there is a well-publicised scheme relating to furlough. There are also rules relating to statutory sick pay and to holidays.

The legislation just sets out the bare bones of the law. There are of course many other questions that people will have. Some of these questions are answered in the guidance published by the government both for employers and employees. The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) website provides more detailed guidance. This guidance is regularly updated and can change as new questions arise.

Working from home

A restriction on movement, and therefore the need to work from home, is the law with which people are most familiar, and is expected to be updated every 21 days. Among the other restrictions that affect everyday life, the law says that someone can only travel for the purposes of work where it is not reasonably possible for that person to work from home. In addition to this, restrictions require the closure of restaurants and most shops and so this also affects a huge number of workers and employees who may be furloughed or even made redundant.

Furlough

It is possible that employers may end up furloughing up to a third of private sector workers. The legislation that allows the government to provide financial assistance to employers and employees is in section 75 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. The rest of the scheme is set out in guidance, and can be confusing. The gov.uk website also has advice for employers and employees, and sets out the full legal scheme. The legislation is initially for three months. The scheme is open to all UK employers that had started on or before 19 March 2020 and is backdated to 1 March 2020. The minimum period an employee can be put on furlough is three weeks. Employers can claim for 80% of furloughed employees’ usual monthly wage costs, up to £2,500 a month, plus the associated Employer National Insurance contributions and minimum automatic enrolment employer pension contributions on that wage. Employers can use this scheme anytime during this period.

Sick pay

A large number of people will not be ill from the virus, but will have to self-isolate because they have been in contact with someone who is sick. Someone who is an employee is generally entitled to sick pay if he earns at least the lower earnings limit (£118 per week until 5 April 2020, £120 from 6 April, with the amount of sick pay being £94.25 per week until 5 April, £95.85 thereafter). There is also a waiting period of three days for which this is not payable.

There have recently been several sets of Sick Pay regulations, and it can be difficult to work out what the situation is. Effectively, the new regulations state that if someone is unable to work because of a reason related to coronavirus, which means that either he is ill, self-isolating for seven days, or lives with someone who is ill and is self-isolating for 14 days, then sick pay is available. This is backdated to 13 March 2020. Online self-isolation notes are available from the NHS 111 website. In addition to this, the rule relating to waiting days is suspended if the person is off for a reason connected with coronavirus, and so the sick pay is payable immediately. There is no change to the lower earnings limit.

Holidays

The minimum amount of holiday that a worker has is 28 days. 20 days of this is minimum leave, and the other 8 days effectively cover bank holidays. In normal circumstances, this has to be taken by the end of the working year. There is new legislation which makes some changes to the 20 days, and says that if, from 27 March 2020, it is not reasonably practicable for a worker to take some or all of the leave that he was entitled to under the Working Time Regulations, and that this is because of the effects of the coronavirus (whether these effects are on the worker, the employer, the wider economy or society), then the untaken leave can be carried forward and taken in the following two leave years.

The legislation in this article is of course subject to change, and the government is under an obligation to review it.

Feature Image Credit: by veerasantinithi via Pixabay.

The post COVID-19 and employment law in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

April 20, 2020

How we can equip ourselves against climate change

Earth Day highlights the need for climate action, but what role does human-caused climate change play in creating disasters? Science paints a nuanced picture, instructing us to focus on reducing vulnerabilities to weather and climate, irrespective of how the environment is changing.

Starting with the basics, a disaster is a situation requiring outside help for coping, so it is only a disaster if it involves people. Climate means weather statistics over decades. Climate change refers to changes to these statistics. Neither climate nor climate change mention people.

Yet human-caused climate change is rapidly affecting environmental phenomena such as floods, storms, some droughts, and air temperature extremes. If we could deal with this weather without being harmed, then no major concern arises. Typically, unprepared people and infrastructure are in the way, so weather becomes hazardous.

This is vulnerability: The social and political processes forcing people to become adversely affected by regular environmental phenomena such as severe weather. Sometimes we choose to live in harm’s way, perhaps purchasing a floodplain house to enjoy beautiful ocean views without taking adequate measures to reduce flood damage. More often, vulnerable situations are inflicted on people; women or ethnic minorities might choose not to evacuate, for example, because they fear and expect abuse and violence in the public storm shelter.

A disaster cannot happen without vulnerability. Consider warmer air due to climate change holding more moisture, leading to more intense rainfalls. Without addressing storm and flood vulnerabilities, worse flood disasters can happen under climate change. If we tackle vulnerabilities, then the changing rainfall is not hazardous.

Not all aspects of storms worsen with climate change. Projections for hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones under human-caused climate change suggest that fewer will form, but they will be more powerful. No matter which storms form, we can choose to deal with them by doing what we ought to do anyway. We shouldn’t build in floodplains without flood-related measures. We should evacuate if infrastructure will not withstand the wind and water. We shouldn’t marginalise people through racism, sexism, and homophobia so that they fear getting help to prepare or they stay in harm’s way.

The same holds true for many other environmental phenomena influenced by climate change.

But not all.

Increased heat and humidity curtail outdoor agricultural work, while people and animals require more water to stay healthy, increasing the likelihood of drought. Crops suffer as evaporation rates increase, although we could substitute with plants having different tilling and irrigation requirements. When heat-humidity-time combinations beyond human tolerance are reached, then outdoor work must stop, rather than simply going slower.

Ultimately, without tackling climate change, large swathes of land may become too hot for living or working—extremes we have never before encountered—leading to large-scale mortality or migration and possible knock-on effects on food supplies. Future heatwaves could be disasters from human-caused climate change for which we have little comprehensive opportunity to reduce vulnerability.

It might be the same if human-caused climate change leads the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets to melt. In worst-case scenarios, over several centuries, seas would rise higher than a twenty-storey building, drowning around a dozen island countries and many coastal cities. Much of Amsterdam, Manila, and New York City could be transformed into territory for snorkelling or scuba diving.

These long-term extremes of heat-humidity combinations and ice sheets melting are frightening—as might be the oceans acidifying when they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—and could be devastating for us. More day-to-day, we still need to highlight that science is clear about vulnerability, not the environment, causing disasters. Natural disasters do not exist because we choose where and how to live, and how we treat people, so that weather and other natural forces can harm us.

Earth Day should draw our attention to the people being forced to be vulnerable, living on the slopes of the active volcano overshadowing Mexico City, the floodplains of Manila and New Orleans, and the landslide-prone hills of La Paz and Freetown. Climate change does not engrain the sexism which normalises gender-based violence in storm shelters, discouraging some from evacuating. Nor does climate change dictate the privatisation of energy companies, making it unaffordable for many to heat their homes in winter and cool them in summer.

All these create vulnerability through human choices. And thus, irrespective of what we are doing to the climate, must disasters be born.

Featured image: public domain by Kelly Sikkema via Unsplash.

The post How we can equip ourselves against climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2020

What the Civil War can teach us about COVID-19

More than any crisis in recent memory, the coronavirus pandemic is changing how Americans understand time and imagine the future. Greater threats, like climate change, loom on the horizon, but they haven’t transformed time, because slower perils do not disrupt life and shutter society like COVID-19. During this crisis, familiar rhythms that structure time seem suspended like a pendulum in a broken clock. Children don’t wait for school buses or anticipate the bell that releases them at the end of the day. College students won’t cross a stage at graduation to mark the commencement of life’s next chapter. With mandates to stay home and close nonessential businesses, people no longer endure rush hour. Fortunate employees try to replicate work’s daily rhythms at home, while others stare at an empty future after being laid off. Social distancing is also affecting time in profound ways. When isolating from friends, relatives, and co-workers, the gatherings that marked our calendars—coffee breaks, happy hours, dates, church services, and birthday parties—are virtual or gone. Seasons continue to change, but without March Madness and baseball’s opening day, sports fans mourn the rites of spring.

Beneath the loss of rituals that structure our time lurks the presence of death and a deepening uncertainty about how and when this will end. Nothing cuts through human illusions of controlling time and the future like mortality. High risk populations face a danger that may mark their fate. Eventually, death interrupts everyone’s plans, but COVID-19 has changed humanity’s prospects. Tenuous at best are historical and medical comparisons to this pandemic and its course. While the novelty of the virus unsettles predictions about it, scientists scramble to learn its characteristics and find a cure. The long incubation period and lack of widespread testing raise uncertainties about the current spread of contagion. As we distance ourselves from others to “flatten the curve” of the pandemic, another factor undermines educated guesses about the future—humanity’s unpredictability. How long public officials maintain closures, how low stock markets drop, and how many people disregard warnings or hoard masks and gloves will affect the virus’s future, and ours, more than any chart can calculate. Most of us will survive this crisis, but as we live through it, our old ways of imagining time and tomorrow may not.

History cannot unveil tomorrow, but it can help us understand how our view of the future, whatever it brings, changes over time. The Civil War, the last major conflict on American soil, disrupted life and brought death like no other event in US history. “I cannot believe I am the same person that was ever so lighthearted and hopeful in the future,” a war widow wrote her uncle in October 1865. Before the war, most Americans thought the future was open, opportunities abounded, and humanity made history. These people believed in progress, looked forward to tomorrow, and imagined themselves traveling through time, and shaping the future and their lives in the process. In 1861 thousands of volunteer soldiers embodied an optimistic view that daring, enterprising men controlled the future and held the fate of the nation in their hands. As New Yorker Theodore Winthrop put it when he marched to war, “We are making our history hand over hand.” He scoffed at politicians’ speeches and women’s prayers; only men of action forged time. Weeks later Winthrop was the first officer killed in battle.

“Arlington, Virginia. Rear entrance, Fort Corcoran” by Unknown Author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Arlington, Virginia. Rear entrance, Fort Corcoran” by Unknown Author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.When the war acquired its own momentum and killed thousands, it undercut Americans’ confidence that they made history by anticipating events and fashioning the future. The destructive indecision of military campaigns challenged people’s faith in perpetual progress. Facing uncertainty, some Americans looked to God to design tomorrow and provide a meaningful ending to the war. Others doubted that the Almighty was responsible for such carnage and waste. For doubters, the war defied linear narratives toward civilization or salvation. Whatever fate awaited America, people sensed that the war’s outcome would arrive in its own time and on its own terms. The crisis over slavery and the Union changed how Americans imagined time. Instead of focusing on an open future that people made, survivors envisioned a closed future that other forces, impersonal or supernatural, had already determined. Tomorrow remained ahead of them, but instead of moving toward it, people expected time to approach them like waves crashing ashore.

Adversity prepared some Americans for this future better than others. When the war came, gender norms compelled women to stay behind and await the future. Fate would come when either their men returned or news of their deaths arrived. When her brother headed to the front, South Carolinian Grace Elmore wrote, “Dante never saw more clearly the tortures of the damned than I have the possibilities of the Future.” She imagined him dead on the battlefield, her mother shorn of wealth in old age, her family scattered. Untold thousands of women expected similar tragedies and felt powerless to avoid them. Perhaps African Americans faced the war’s uncertain future with the most experience and facility. Recalling his life enslaved to the Brent family in Richmond, Thomas Johnson remembered anxiety, rumors, and biblical readings rippling through the black community as the war approached. Years of bondage taught Johnson and others the mental discipline to empty their minds during painful times, be attuned to impersonal forces, and keep hope’s flame sheltered and hidden. Freedom finally arrived when the Union army entered Richmond on April 3, 1865. “That scene of years ago comes vividly before me at this moment,” Johnson wrote at the turn of the century. Finally, the long night of affliction had passed. Slavery’s survivors danced in the streets, played music, yelled at the top of their lungs, and gave impromptu speeches to gathering crowds.

Whenever our affliction ends, similar scenes will fill city streets across America. Like Civil War Americans, we will mourn loved ones who perished in the crisis and face the future with a more complicated view of time. Tempered by adversity and mindful of forces beyond our control, will we better understand how the future shapes us while we approach it? Only time will tell.

Featured Image Credit: “Seven Buildings – Washington DC – 1865” by Unknown Author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What the Civil War can teach us about COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

Is the fetus a resident or a body part?

Pregnancy has variously been described as unique, confusing and full of ambivalence; as involving a doubling or splitting the person; and as challenging widely-held philosophical assumptions about firm distinctions between self and other or mind and body. But what, exactly, is pregnancy? What is this unique human – and mammalian – state? What is its nature?

I would not be the first to note this question that appears to have been under-researched in philosophy – and Western intellectual history as a whole. That may seem a surprising claim given the burgeoning philosophical literature about, and the widespread public discussion of, abortion. But discussions about abortion rarely focus on the nature of pregnancy. Abortion discussions they tend to ask what a fetus is. Such discussions focus on whether a fetus has values, rights, or entitlements and whether another person can legitimately decide to cease providing it with the highly intimate and invasive, constant and irreplaceable life-support that is necessary for its existence.

That, however, does not tell us what pregnancy is. Such discussions do not tell us about the nature of pregnancy, or the nature of the maternal-fetal relationship. In a way this omission is all the more surprising because all people agree – at least if they pause to think about it – that questions about abortion are only so unique, intractable, and entrenched because of the unique nature of pregnancy.

Only in pregnancy – and in no other human circumstance – do we routinely find ourselves not only providing direct, constant and irreplaceable life-support to a developing human through direct use and wholesale involvement of our entire body; we also find that that human is developing in our most intimate insides. Or – to capture the perspective from the other inside – only in pregnancy does a developing human find itself not only wholly dependent and reliant on a single irreplaceable other human, but residing in its most intimate insides, directly hooked up to her physiology and partaking in her physical/hormonal state.

So how should we understand this unique – yet entirely common and mundane – human and mammalian state? What is the maternal-fetal relationship? There are many ways of approaching these questions, but at least one place to start is to ask about parts. Most things in our body, after all, are parts of our body. Not just our hearts and kidneys, but also our blood and, sex-cells, and the every-changing molecules of which are bodies are composed. Perhaps, even, body-parts that have been donated to us, such as donated blood or organs. The embryo/fetus, like other body-parts, resides in the innermost regions of the mammal. So, is it a part of that mammal, or, like the metaphorical bun in the oven, merely a temporarily resident non-part?

It is this question that I invite you to consider. Despite what appears to be a very widespread assumption to the contrary, I am inclined to argue that the fetus is indeed part of the maternal organism. First, it is immunologically tolerated by the pregnant organism. Second, it is directly and topologically connected to the rest of the maternal organism via umbilical cord and placenta, which is composed of fetal and maternal-origin cells, without a clear or defined boundary between the two. Third, the fetus is physiologically integrated into the pregnant organism, and regulated as part of one metabolic system. Whilst none of these are perfect indicators of organismic parthood, they jointly pose a very strong case. Note that all of these change radically at birth: the baby is no longer topologically connected (and placenta and umbilical cord are discarded); the baby is now its own physiological, homeostatic and metabolic unit (although still heavily dependent on maternal care/provision and care); and it is no longer in direct contact with the maternal immune system.

At the same time I certainly don’t to find any good arguments in favour of the view that the fetus isn’t a part; the position tends to be assumed, but not argued for.

But I don’t mean that to be the end of the question. Rather I hope it is its very beginning. 2020 is rather late seriously to begin considering the nature of pregnancy – the process by which every human, and every mammal, comes into existence. Death, by contrast (which strikes me as far less complicated) has been a favourite philosophical topic for at least 2000 years.

It is surprising that convictions about the non-parthood of fetuses appear to be so deeply entrenched, in the absence of hardly any substantial argument and reflection on the question. My main hope is that this will change, and that my words will not be the final, but the rather the first, say in what I think should be a rich and careful collective effort in answer questions about the nature of pregnancy.

After all – isn’t it often said that if you don’t know where you come from, you don’t know where you are going? We all come from a pregnancy; it is time to catch up and understand what that means.

Featured Image Credit: pregnant via Pixabay.

The post Is the fetus a resident or a body part? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 16, 2020

Eight rules for teaching during COVID-19

At 10:50 a.m. recently, I was all set to teach my Theory II class. My I-Pad was charged. I had the links queued up to the textbook for screen share, and I had already created several videos explaining the concepts. When the 11:00 a.m. hour arrived and only two students were visible on Zoom, my confidence started to plummet. By 11:05 a few more students had arrived, but my technology was not working quickly and my internet was at best, spotty. I noticed that not one of my students had logged on to watch the videos I had worked so hard on during the late hours of Saturday night. In those first ten minutes of teaching, my students said very little and looked like they wanted to be anywhere but on my zoom session.

During the class meeting, my nine-year-old daughter came rushing into my home office to ask a question about her English assignment. I had to ask my husband working in the other room to get off the internet for 30 minutes so I could have the speed I needed to complete the discussion. And even though there was a bit of laughter at the end of our class session, both my students and myself know that this is not normal. This is the reality of teaching in the wake of this pandemic. And while some are discussing the joys of home schooling or the ability to teach all of their music classes from their studios, I don’t know if I would call what I am doing home schooling or effective online instruction. I am in crisis mode and I am crisis teaching.

In my crisis teaching mode, I have come up with eight rules that have helped me to navigate through this new normal.

Be gentle with yourself.Most of you never signed up to teach an online class and in most situations, our students didn’t sign up for an online class with us either.Check in with your students.

Be open to guideline dates instead of deadline dates. I have students who have grandparents diagnosed with COVID-19, students working over 40 hours a week in fast food to support families who have been furloughed, and students responsible for homeschooling siblings. Let them know you want to hear from them. Humans first, students second.Hold class asynchronously if possible.

My freshman class asked for one class meeting a week as did my graduate class. Neither class meetings are required and I record the session and house the recording on my course management site. Some students want the live face-to-face time, while others simply can’t for a variety of reasons.Save your head space for what matters.

There is an abundance of technology resources out there and they are all competing for your head space, but only give them a bit of that space. The amount of emails I received from companies was a bit overwhelming and I had to forgive myself for not looking at each and every one of them. Pick one or two companies to explore and see if that platform adds to your teaching. If it doesn’t, move on. Ask your colleagues what is working well and how they are using the program. Don’t feel guilty if you are just using your LMS, YouTube, and online textbook.If you are making videos, they do not have to be perfect.

I know in the world of academia, we can be overwhelmed by imposter syndrome and the thought of our video being shared across the internet is horrifying. What if we said a pitch wrong or played a wrong chord on our keyboard? Say goodbye to tenure and respect, right? I spent my spring break recording the same video at least five times, even with pauses and such in my recording software. I finally just hit upload. Now is not the time for judgement. Remember, crisis teaching.If funds allow, invest in a decent headset and microphone.

Many of us have spent hours in meetings over the past few weeks and we still deserve to hear our confident voices heard, and heard well over technology. A good noise cancelling microphone attached to a headset will cost about $40. It is a good investment.Invite guest speakers to your class, live or recorded.

Just a month ago, we were sitting in a conference room working on a budget for guest speakers. Now many of those pioneers in the field are sitting in front of their computer as well and have the time to give a 20 minute interview to the class. I have put together a YouTube playlist for my pedagogy class where I interview effective instructors and am inviting authors to my classes based on the articles read for the week. I have not had one person say no to these requests.Check in with your colleagues and friends, outside of a required meeting time.

Recently I joined a zoom session with eight of my friends from graduate school. I haven’t seen most of them in over 15 years. The session lasted almost three hours and it was the first time I woke up with a smile on my face in weeks. On Friday night, about 10 colleagues from around the country joined together for a virtual happy hour where we shared our frustrations and triumphs in this new teaching environment. Laughter and being honest without fear of retribution is important as are human relationships. Perhaps the Eagles said it best: “this prison is walking through this world all alone.” And colleagues, we aren’t alone. As I ended an email to a frustrated student, “we got this.” Emphasis on the word we.

Step away from the computer and find the most recent version of your teaching philosophy. Read it out loud. Have your core teaching principles and teaching philosophies changed or have they just been challenged in this time of crisis teaching? For most of us, the answer is somewhat and for others it may be an enthusiastic no or defeated yes. The answers don’t lie in the latest technology, but in our abilities to be authentic and effective educators. What defines students success in this period of time may look completely different. A successful student may not be the one that achieved the highest GPA or was awarded the top assistantship. It’s the student that was determined to learn and showed up when they could. An effective instructor may not be the one who is able to use four programs at the same time while recordings multiple voice parts for a sight singing project. It’s the instructor that cares and is willing to go the extra mile to empower the spirit and the mind of their students through a new platform. Both parties show up, admit the challenges, embrace the newness, and do what they can to not only master content, but to connect in ways that perhaps we didn’t know were vital.

There’s more than content and delivery to be discussed when this period is behind us. Perhaps the lesson to be learned is not about what or even how we taught during COVID-19. Perhaps this period is a lesson in why we teach. I would like to think it has to do with importance and the power of creative thinking and the human spirit.

The post Eight rules for teaching during COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

April 15, 2020

Lessons learnt from Coronavirus and global environmental challenges

The whole world is now shaken by the tragic coronavirus pandemic. Despite its unprecedented and devastating dynamic, such a crisis provides crucial insights to the state of the current international system, including its capacity to respond to worldwide emergencies. This helps us gauge our system’s ability to tackle more long-term issues, such as the global environmental crisis. Whilst these two things may seem very separate, there is a lot that links the current coronavirus outbreak and our global environmental problems.

Some bodies claim that the relation between the two is antagonistic, with the outbreak demonstrating how more needs to be done to protect wildlife and the environment. On 3 March the United Nations Environment Programme pointed toward environmental degradation as an explanation for the origin of COVID-19. It claimed that such an outbreak was related to ecosystem degradation and wildlife threats, which causes the transmission of viruses and diseases from wild species to humans. For the United Nations Environment Programme the outbreak therefore reveals the need to better combat environmental degradation.

Some bodies claim that the relation between the two is synergistic: whilst the pandemic is overwhelming a negative occurrence, it has had positive effects on the global environment. Comparing satellite images of China between January and February 2020, the National Aeronautics and Space Agency and the European Space Agency have demonstrated the positive environmental side effects of the quarantine measures taken by states to contain the pandemic, especially with regards to air quality. Similar observations are now surfacing in terms of the levels of air pollution in northern Italy. The drastic reduction in air traffic will also have positive side effects for climate change mitigation. Countries will benefit from these changes in terms of their commitment to climate change, even if these changes are to last only temporarily.

These observations, while noteworthy, do not take into account the seriousness of either of these crises. Whilst this is a seemingly positive time for the environment, environmentalists are less than happy that it has taken a pandemic to effect change in our environmental impact. It would have been preferred that these positive impacts be reached by progressive measures rather than through the current circumstances.

More importantly, the pandemic has brought several crucial issues about the world we live in back to the forefront of debate in global politics that need further inquiry, including social inequality, sovereignty, and adaptation. These are also at the core of global environmental politics.

The pandemic, and the measures taken in an attempt to control it, remind us of the realities of social inequality. As recalled by the United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Gutierrez: “This is, above all, a human crisis that calls for solidarity”. Every country, region, social class, and individual has different capabilities to tackle the pandemic. Already vulnerable countries and populations are unfortunately more susceptible to the outbreak. Current figures also indicate inequalities between generations, with older people more likely to develop a serious form of the disease, while young people are predominantly asymptomatic carriers.

Whilst inequalities are allowing the coronavirus to take a hold of the world, with the poorer populations not receiving the medical care and resources they need, the virus itself is highlighting the need for change to help balance social inequality. In global environmental politics, scholars have long identified equality and justice as important facets of society in need of protection. They have shown that justice can take many forms, from the protection of minorities rights (such as indigenous and local communities) to inter-generational justice. They have also shown how justice entails the need for adjustment mechanisms to be designed to help the most vulnerable. Just as inequalities reinforce the pandemic, inequalities reinforce and cause global environmental problems and should therefore be at the center of the political agenda now and in the future.

The coronavirus also exacerbates the sovereignty crisis. The European Union, one of the most advanced supranational organizations, speaking with one voice on many different topics, did not manage to corroborate to create a common strategy to fight the pandemic. All European Union external borders have been closed and, within the European Union, countries are closing borders that would usually stay open under the Schengen Area. This form of lockdown has now become the norm within Europe, with the majority of international flights being cancelled. Individual governments have taken back control, isolating themselves and their countries, whilst rumors and suspicions about other nations are rife.

Global environmental political scholars have been reflecting on the use of sovereignty as a political instrument for a long time. While sovereignty is an important instrument in enforcing environmental policies, and the pandemic clearly shows that individual governments can impose impressive regulatory means when needed, international and transnational collaborations are also essential to ensure information sharing, external control, and the sharing of good practices. National protection measures should be backed by international co-ordination mechanisms. The worldwide spread of the virus demonstrates how the world is highly interdependent and requires global governance and co-ordination.

Finally, the pandemic also reveals interesting insights on adaptation. People all around the world are being forced to change their habits and adopt new everyday practices. New techniques, such as the mass use of online interaction and communication, are flourishing. Global environmental scholars have been calling on our capacity to evolve and embrace changes to make our practices more sustainable for a long time. Some environmentalists suggest that the environmental crisis we are facing will mirror the coronavirus crisis.

By this, however, environmentalists are suggesting that, as with the coronavirus, people will take no action whilst the crisis is not directly affecting them as nations and communities. We’ll only take action when the problem suddenly explodes because of its exponential dynamic, by which time it might be too late to take any effective measures. The pandemic reveals the need to anticipate adaptation. To fight environmental degradation, some of the current pandemic adaptation strategies could remain in place even after the outbreak. As we begin to recover from COVID-19, we will have to think about how to rebuild our world and the global economy and should take this opportunity to direct our actions towards a greener future.

Featured Image Credit: Joshua Rawson-Harris

The post Lessons learnt from Coronavirus and global environmental challenges appeared first on OUPblog.

It’s time for the government to introduce food rationing

The current COVID-19 emergency has much to interest students of politics. Does it demonstrate that authoritarian regimes are able to tackle a pandemic rather more easily and efficiently than liberal democracies? Given the origin of the virus, what does it tell us about our relationship with non-human nature? Is the pandemic a product of globalization? What does it tell us about population size and density? What does it tell us about the nature of politics itself?

Perhaps the most significant factor for students of politics is the role of the state. Ironically, in the United Kingdom, the arrival of the virus has achieved, in terms of the state’s reach, more than even the most ardent Corbynite could have dreamt about. Not only has the state intervened to shore up the economy – by, most notably, agreeing to pay a significant part of the wages of those economically disadvantaged by the health emergency – it has also taken unparalleled measures to control our everyday movements.

Arguably, though, the state should do more.

One of the most pervasive images of the present COVID-19 emergency has been the panic buying and stockpiling of food and toiletries. Rather oddly, when state intervention and control has become the norm, the state has not sought to formally ration supermarket produce. Instead the accent has been on the moral dimension. Those who have stripped our supermarket shelves of food and toiletries have been described, amongst other things, as selfish, greedy, ignorant, and immoral. The government has sought to reassure people that there is more than enough to go around and has appealed to their better nature – be reasonable when you shop, think about what you are depriving others of.

In actual fact, stockpiling has nothing to do with moral character but has everything to do with a collective action problem identified by rational choice theory. Rational choice approaches to politics and social organisation have become an increasingly important branch of the social sciences. Following a deductive logic, the (reasonable) assumptions made are that human beings are essentially rational, utility maximisers who will follow the path of action most likely to benefit them (and their families). This approach has been used in game theory where individual behaviour is applied to particular situations. This reveals how difficult it can be for rational individuals to reach optimal outcomes. That is people might not cooperate even when it is in their best interests to do so.

This collective action problem can be illustrated by the classic rational choice instrument, the prisoner’s dilemma. In this scenario, two people suspected of being involved in a robbery are arrested and interviewed separately in a police station. There is insufficient evidence to convict the pair of robbery but there is enough evidence to convict them of a lesser charge, whatever that may be. The suspects have a choice put to them by the police, to either keep quiet or to betray the other with different penalties imposed depending on their choice. Three outcomes are possible.

The first outcome is that both suspects keep quiet. As a result, they each receive a sentence of one year in prison (on the lesser charge). The second is that both betray each other. As a result, they each receive a sentence of two years in prison. The third outcome is that one suspect betrays the other whereas the other suspect keeps quiet. As a result, the suspect who betrays gets set free whilst the suspect who keeps quiet gets three years in prison.

In this scenario, each prisoner gets a higher reward by betraying the other rather than cooperating (staying silent), even though the optimum solution would be to cooperate. So, one of the prisoners (Prisoner A) has a choice whether to stay silent and cooperate or betray his fellow prisoner. If he cooperates and stays silent his fellow prisoner should betray and therefore be set free. If Prisoner A betrays, his fellow prisoner should also betray because two years in prison is better than serving three years. In other words, the rational strategy is to betray rather than cooperate.

So, what has all this got to do with panic buying and stockpiling? Well, clearly the best outcome – supermarket shelves remaining stocked with more than enough for everyone shopping at any one time – can only be achieved by cooperation, by everyone taking only what they need. However, we are not in a position to consult with our fellow shoppers to discuss the matter, and even if we were, there is no guarantee that we will not be double-crossed by people who agree to cooperate and then betray us by over-buying. As a result, because we do not trust each other to cooperate (and we also do not trust the Government’s regular reassurances that there are more than enough products for everyone) the best strategy is to over-buy to ensure we are not left with nothing. That is the rational thing to do.

Can this problem be resolved? Well, one possibility, already widely practised, is for supermarkets to limit purchases to a certain number of each item. The problem with this, however, is that, even if we are restricted to buying only one of each item, it only prevents over-buying on one particular occasion. That is, it does not stop shoppers coming back repeatedly to buy the same things over and over again. And that is what is happening. That is why there are queues at supermarkets.

Another possibility is for supermarkets to ration purchases, to put a limit on what can be bought over a set period of time. However, this, of course, will have consequences for profit margins. In another prisoner’s dilemma-type scenario it would not be rational for one supermarket to limit its profits particularly when there is no guarantee that other supermarkets would be prepared to cooperate and do the same.

So, what is left? Well, the only genuine solution to stockpiling and panic buying is for the state to intervene and introduce a compulsory rationing scheme to which every supermarket and every shopper would have to adhere. The government’s virus discourse already has war-time parallels, albeit with an invisible enemy, and, in that sense, the introduction of rationing seems entirely appropriate.

Featured Image by CDC.

The post It’s time for the government to introduce food rationing appeared first on OUPblog.

April 14, 2020

English, Chinese, and all, all, all

I think I should clarify my position on the well-known similarities between and among some languages. In the comment on the March gleanings (April 1, 2020), our correspondent pointed to a work by Professor Tsung-tung Chang on the genetic relationship between Indo-European and Chinese. I have been aware of this work for a long time, but, since I am not a specialist in Chinese linguistics and do not know the language, I never mentioned my skeptical attitude toward it in print or in my lectures, the more so as Tsung-tung Chang (1931-2000) can no longer answer me. But a comment in the blog calls for a response.

I think it is proper to refer to Tsung-tung Chang as simply Chang, because the Zürich Sinologist Professor Wolfgang Behr, the author of an excellent article, partly devoted to Chang’s work, does so. Chang, who was a professor in Frankfurt, put together a voluminous dictionary (over 1500 pages) comparing Indo-European and Chinese. I assume that the work’s language is German. That dictionary has not been published, but a representative specimen of the etymologies is available online in the essay titled “Indo-European Vocabulary in Old Chinese…”; I am familiar only with this extract. As his starting point, Chang used the reconstructed roots listed in the dictionary of Indo-European by Julius Pokorny. All etymologists consult this standard work, though the roots one finds there are being constantly discussed, improved, and even rejected. (It is enough to compare this dictionary with its predecessor, known as Walde-Pokorny.) Yet the great compendium remains the most authoritative one we have. For instance, the etymologies of most words in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language depend entirely on Pokorny. Chang discovered that hundreds of Chinese words resemble very closely, almost to a letter, Pokorny’s roots and concluded that they were of Indo-European origin. The two families turned out to be related.

A map of ancient China. See feature image credit.

A map of ancient China. See feature image credit.Since I can say nothing about the origin of Chinese words, I’ll note only some general problems with Chang’s reconstruction. Curiously, while comparing almost any two languages, we notice countless similarities. The oldest European etymologists tried to derive the words of their languages from Hebrew or Aramaic, the language of Paradise, which Adam and Eve allegedly spoke. It is amazing how successful they were! Other old comparisons produced less spectacular results, but attempts to trace the words of English and German to Greek also yielded ostensibly noteworthy results.

Then several amateurs appeared who showed to their satisfaction that most words of the modern European languages (or of one language, for instance, English) go back to Dutch, Irish, Arabic (the number of look-alikes between Arabic and English is indeed amazing), or Russian. The Russian “monomaniac” of this type is still active, and it took a serious effort to stop a modern adventurer from reviving the Hebrew hypothesis. He, too, worked with English, and his dictionary is a joy to read (if you appreciate specious humor in historical linguistics). We should disregard the nationalistic impulses behind some of such efforts (they are wicked and not worthy of refutation) and admit that, wherever we may cast our net, the similarities will indeed be numerous, even spectacular. Characteristically, when such authors were not misguided amateurs or doctors (some of the craziest hypotheses on etymology have been advanced by medical men), they were usually not professional linguists, but historians, archeologists, specialists in paleography, or art history. They usually knew a good deal about languages but lacked professional training in the terrain where they ventured to tread. Nor was Chang a historical linguist, and his knowledge of Indo-European and the methods of reconstruction did not go too far. Pokorny’s dictionary is the juice of Indo-European wisdom, but one is expected to know the fruits that have been squeezed to produce it. Sorry for speaking in ornate metaphors.

The images of ancient gods. First image: Muzha (deity) by Anandajoti Bhikku. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. Second image: Marble head of a god, probably Zeus. Public domain via Picryl.

The images of ancient gods. First image: Muzha (deity) by Anandajoti Bhikku. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. Second image: Marble head of a god, probably Zeus. Public domain via Picryl.The massive similarities between languages can be explained in several ways. 1) If the oldest words of all languages were monosyllabic (and such are almost all roots in Pokorny’s dictionary), then the number of sound complexes like bid, gob, am, put, etc. is rather limited, and the coincidences are inevitable. 2) Sound-imitative words, whose role in the emergence of speech should not be underestimated, are bound to be similar in all languages. Professor Victor Mair, an American Sinologist and a supporter of Chang’s conclusions, cited the closeness between the reconstructed Indo-European and the Chinese name of the cow. Perhaps the Indo-European word for “cattle” was indeed gwōu-; most likely, it was onomatopoeic. Even the Sumerian noun of approximately the same meaning sounded as gu, and Sumerian is neither an Indo-European nor a Semitic language; its origin has not been discovered. (The Sumerians lived in Mesopotamia.)

Hensleigh Wedgwood, a prominent etymologist of the pre-Skeat era, succeeded in stringing together numerous look-alikes from unrelated languages, and quite often comparativists don’t know what to do with them (therefore, they choose to ignore his material). The same should be said about the words vaguely called expressive. Wilhelm Oehl, the Swiss scholar who wrote extensively about what he called “primitive word creation” (elementare Wortschöpfung), is familiar to the readers of this blog. His far-reaching conclusions are interesting but should be used with caution. 3) Massive borrowing is always a possibility. 4) Finally, perhaps all languages are related, so that there is no mystery in the similarities we observe. I have more than once mentioned Alfredo Trombetti and other precursors of the Nostratic hypothesis.

Rub-a-dub-dub: the beginning of language?Image by Fil.Al. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

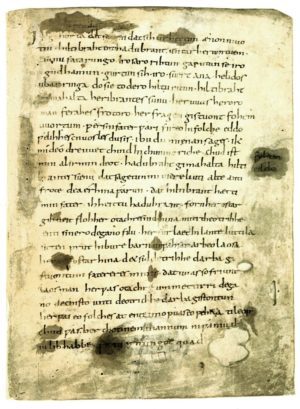

Rub-a-dub-dub: the beginning of language?Image by Fil.Al. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. The Old High German “Hildebrandslied.” From the Landes- und Murhardsche Bibliothek, Kassel, Germany, 2° Ms. theol.54, Bl. 1r. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.It follows that responsible conclusions about the relations between the oldest languages should be drawn with extreme caution. Above, I ignored the ridiculous ideas that trace all the words of all languages to a very small number of roots, sometimes as few as four. Those conclusions also appear persuasive to many. (Incidentally, the famous Marxist

Nikolay Marr

, the one-time ruler of Soviet linguistics, was an archeologist and began his career by promoting the indefensible idea that Armenian and Georgian are related.) Apparently, Chang did not realize the complexity of the problem he attacked. Nor does he seem to have been aware of the works by several older scholars who had also noticed and discussed the numerous similarities between the words of Indo-European and Chinese. A historical linguist should take those convergencies seriously but beware of drawing rash conclusions.

The Old High German “Hildebrandslied.” From the Landes- und Murhardsche Bibliothek, Kassel, Germany, 2° Ms. theol.54, Bl. 1r. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.It follows that responsible conclusions about the relations between the oldest languages should be drawn with extreme caution. Above, I ignored the ridiculous ideas that trace all the words of all languages to a very small number of roots, sometimes as few as four. Those conclusions also appear persuasive to many. (Incidentally, the famous Marxist

Nikolay Marr

, the one-time ruler of Soviet linguistics, was an archeologist and began his career by promoting the indefensible idea that Armenian and Georgian are related.) Apparently, Chang did not realize the complexity of the problem he attacked. Nor does he seem to have been aware of the works by several older scholars who had also noticed and discussed the numerous similarities between the words of Indo-European and Chinese. A historical linguist should take those convergencies seriously but beware of drawing rash conclusions.Chang acquainted himself with Old High German and was struck by the presence of the words that resembled those of his native language. Among other things, he cited such Modern German phrases as alt und jung “old (people) and young” and concluded that Germanic had once had adjectives devoid of endings. But the forms in such idioms are the product of many centuries of development. He wrote that Southern Germanic might have emerged later under the influence of Altaic tribes, while the system of Northern Germanic had been much poorer. Obviously, he never looked at Runic inscriptions. He also suggested that the oldest forms of Germanic were very simple and lacked declensions and that the monuments of the early epoch at our disposal should not be trusted, because all of them are translations of the biblical texts. Strangely, he missed Old Germanic poetry. It is just such bold hypotheses (“Germanic emerging under the influence of Altaic”; “words in Old Germanic having no endings”) that will compromise any hypothesis.

Chang’s lists contain many animal names, the items that should be treated with great caution in the reconstruction of the ties between and among languages. Next to them, we see such abstract concepts as “tempt,” “defy,” and their likes. This looks odd, to say the least. My point is not to criticize Chang, but to appeal for an unhurried and informed analysis of an important problem that will easily repulse all cavalier attacks.

Feature image credit: Three kingdoms of Ancient China. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post English, Chinese, and all, all, all appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2020

The importance of character during war

Nearly 20 years of war following the events of September 11 has resulted in advances in military psychology that stand to improve the well-being of all people, military and civilian alike. The symbiotic relationship between psychology and the military traces back to World War I. With the advent of US involvement in the war, the army and navy had to select and train hundreds of thousands of new soldiers and sailors for increasingly technical jobs. Compared to nineteenth-century wars, World War I required military personnel to operate far more advanced and complicated equipment including aircraft, tanks, and communications systems. To match military personnel to jobs in which they would excel, the military turned to psychologists to develop new aptitude tests rapidly. The tests developed for the military vastly improved the reliability and validity of aptitude testing. Such testing became common in civilian institutions after the war.

Similarly, World War II stimulated psychologists to conduct further research on how to diagnose and treat combat stress and psychological injuries of war. With millions of Americans having served in the war, this knowledge provided a significant boost to clinical psychology. World War II also created a new area of psychology, human factors engineering. Engineers needed psychologists to help them understand the limits of human perceptual and cognitive capabilities in order to design ever more complex weapons and communications systems. The Vietnam War saw the emergence of the understanding of posttraumatic stress disorder, first studied among soldiers and veterans, but soon recognized to be a risk for anyone exposed to severe trauma. Our current understanding of PTSD, its causes, and how to treat it are due in no small measure to the efforts of military psychologists.

In the same manner, the war on terrorism has resulted in a renewed effort by military psychologists to better understand factors that enable military personnel to perform at their best, as well as to better understand suboptimal adjustment or pathology. This emerging research promises benefits to civilians as well. A great example is the military’s research on character and its links to individual and team performance.

Positive character traits like integrity, determination, and courage have long been identified as essential attributes of military personnel. The emergence of positive psychology in the late 1990s provided a new science-focused perspective on character among military personnel. The results of almost 20 years of research are now providing a clearer picture of the role of positive character in leading others in dangerous contexts. For example, trust — an essential element in leadership in any domain — is heavily dependent on the character traits of integrity, caring for others, and moral courage. Both research and practical leadership experience demonstrate the critical role of character in trust and leadership.

Cadets at the nation’s service academies live under an honor code that dictates they will not lie, cheat, or steal, nor tolerate those who do. Military affiliation trumps nationality when it comes to the ranking of top character strengths. In comparing US military academy cadets with Royal Norwegian Naval Academy cadets and US civilian college students, military psychologists discovered that US cadets were more similar to their Norwegian cadet counterparts than they were to US civilian college students. The strongest character attributes among the military cadets regardless of nationality were honesty, hope, bravery, persistence, and teamwork. For the US civilian college students, the highest strengths were kindness, sense of humor, honesty, and judgment.

Army researchers have discovered strong links between individual character and personal adjustment and have developed a program to enhance positive character among its soldiers. Military psychologists have found that positive character traits such as hope and optimism, persistence, self-regulation, social intelligence, and leadership contribute to the emotional and social sense of well-being, and to a sense of meaning and purpose in life. Soldiers high in these and related character strengths are less vulnerable to combat stress, perform better at their jobs, and are more likely to remain in the military compared to those low in these strengths.

Research on character provides just one of many intriguing examples of how military psychology continues to contribute to our knowledge of general psychology. After all, the challenges and stresses that military personnel face are far too easily found in other walks of life. Military research on both positive individual and organizational character have significant implications for how to optimize individual and team performance in law enforcement agencies, sports teams, schools, and in corporations. Thus, the efforts of military psychologists continue to provide insights into human behavior that stand to help us all to perform at our best and to live our lives to the fullest.

Featured photo by Vladislav Nikonov on Unsplash.

The post The importance of character during war appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers