Oxford University Press's Blog, page 133

September 9, 2020

Bring living waters back to our planet

Demanding the Indian government take action to clean and save the nation’s Mother River, the Ganga, activist and former civil engineer Professor G.D. Agarwal died from heart failure in 2018, after fasting for 111 days. Agarwal’s hunger strike remains symbolic of the mounting desperation many of us feel faced with the fragility of rivers, lakes, and wetlands, and the precarious future of the biological life they contain.

Rivers, lakes, and wetlands support extraordinary diversity. Such bodies of water host more species per square kilometre than forests or oceans. Yet they are losing this biodiversity two to three times faster than forests and oceans. Populations of freshwater animals, including river dolphins, sturgeon, beavers, crocodiles, and giant turtles, have already plummeted by 88%. More than a quarter of freshwater species are headed for extinction unless we act now. Accompanying these declines are severe losses in the services that freshwater ecosystems provide to billions of people, including impoverished and vulnerable communities. As well as being reliable stores of fresh water, healthy ecosystems support productive fisheries, nourish agricultural lands, and protect us from floods and droughts.

A 2018 high flow from Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River—one of several experimental environmental flow releases to restore threatened fish species and critical ecosystem functions. (Image by Todd Wojtowicz, US Geological Survey, USA)

A 2018 high flow from Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River—one of several experimental environmental flow releases to restore threatened fish species and critical ecosystem functions. (Image by Todd Wojtowicz, US Geological Survey, USA)Despite irrefutable evidence of an ongoing collapse, coordinated action to reverse the decline of freshwater biodiversity remains weak or lacking, at local, regional, and global levels. This sparked the launch, by members of the international conservation community, of an Emergency Recovery Plan aimed at halting freshwater biodiversity loss, restoring ecosystem services, and safeguarding our life support systems before it is too late. Human impacts on freshwater biodiversity are the result of multiple pressures. Under the plan, recovering freshwater diversity requires six priority actions—restoring river flow regimes, protecting and restoring critical habitats, ensuring connectivity, improving water quality, managing the exploitation of freshwater resources, and preventing and controlling non-native species invasions.

Together, water abstraction, regulation, and pollution are a leading cause of freshwater biodiversity losses globally. Changes in the magnitude and timing of river flows and water levels in lakes and wetlands have degraded habitats, disrupted connectivity pathways, and curtailed important processes, such as sediment, nutrient, and energy dynamics. Freshwater species have lost life cycle cues essential for migration and breeding. The recovery plan urges everyone active in natural resources stewardship to accelerate the implementation of “environmental flows”—the quantity, timing, and quality of freshwater flows and levels necessary to sustain aquatic ecosystems which, in turn, support human cultures, economies, sustainable livelihoods, and well-being.

We now have the tools and methods to assess the water needs of ecosystems and species. Environmental flows are being incorporated into policies and regulations, basin plans, and the design and operation of water infrastructure, including dams, diversions, and sewage treatment works. Stories in Listen to the River demonstrate how governments have been able to safeguard flows or bring clean water and life back to rivers that were running dry. The 2018 Brisbane Declaration and Global Action Agenda on Environmental Flows sets out recommendations for practitioners to enhance the implementation of water recovery and protection efforts. Growing understanding of human-flow relationships is informing socio-cultural objectives for freshwater ecosystem use and condition, advancing environmental water management as a social process.

The Colorado River re-inhabits its dry channel in México during the 2014 transboundary environmental pulse flow that reconnected river and coastal delta for the first time in decades. (Image by Eloise Kendy, The Nature Conservancy)

The Colorado River re-inhabits its dry channel in México during the 2014 transboundary environmental pulse flow that reconnected river and coastal delta for the first time in decades. (Image by Eloise Kendy, The Nature Conservancy)Major freshwater ecosystems and biodiversity have all too long been buried within international and national policy agendas designed for terrestrial systems. It is time to focus on rivers, lakes, and wetlands specifically. Governments, with other leading public, private, and non-governmental organisations, will gather in 2021 to agree a framework for biodiversity that aligns with sustainable development goals. The dialogue has begun as to which targets, indicators, and actions within international agreements will combat freshwater biodiversity loss.

Our planet has shown unimaginable resilience, but at a cost we have not fully reckoned—precipitous declines in the health and biodiversity of freshwater ecosystems will undoubtedly push us beyond the bounds of sustainability. This impending catastrophe, along with climate change and pandemics, epitomises the global risk landscape many of us navigate day to day. We have reached a pivotal moment when all of us, whether policymakers, indigenous and business leaders, resource managers, engineers, scientists, and the public, must re-evaluate priorities and mobilise to protect and recover our freshwater ecosystems for the long term.

Meeting the imperative for accelerating implementation of environmental flows is central to that path and that potential.

Agarwal gave up water in the week before he died. But his hope, like ours, for a world where people understand, value, and conserve freshwater biodiversity, will never evaporate.

Feature image: A giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) catching a fish in the Pantanal Wetland, Brazil.

Image credit: R.Isotti, A.Cambone / Homo Ambiens / WWF.

The post Bring living waters back to our planet appeared first on OUPblog.

September 8, 2020

The reconversion of Hagia Sophia in perspective

At the beginning of January 1921, a special service was held in the cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, with Orthodox and Episcopal clergy offering prayers in six languages—Hungarian, Greek, Arabic, Russian, Serbian, and English—for the restoration of Hagia Sophia as a Christian sanctuary. As reported in the New York Times, the enormous church was filled to capacity for the service, with hundreds of would-be worshippers turned away at the doors. Similar services were held simultaneously in Washington, St. Louis, Detroit, Newark, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

How could a distant building in the capital of the Ottoman Empire hold a central place in the American imagination? The early decades of the twentieth century were rife with international conflict and disaster—the Balkan Wars (1912-13), World War I (1914-18), and the Turkish War of Independence (1919-23). The general public rarely understood the complexities and nuances of the conflicts. It was much easier to encapsulate them in powerful symbolism—indeed, ever since its construction in the sixth century, Hagia Sophia has received a multitude of symbolic readings. Still, nowadays it is difficult to imagine such a global response to a single building. It is similarly difficult today to fathom the political impact Christianity had across Europe and America throughout the nineteenth century, particularly in the waning days of the Ottoman Empire. In these discussions, Hagia Sophia emerged as the Christian equivalent of the Wailing Wall—a universal symbol of lost heritage to people of faith.

Alas, present-day responses to the reconversion also have been primarily from a religious perspective—Christian vs. Muslim—as cultural heritage takes a back seat to heavy-handed political maneuvering.

The American interdenominational prayer services of 1921 came as a response to the British movement known as the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association, founded in 1864. An 1877 article in the New York Times began, “How soon will the crescent over the minarets of St. Sophia be replaced by the cross, or how soon the minarets themselves will be entirely swept away, leaving the outlines of the church in their ancient condition, no seer has foretold.” The same article notes the longstanding belief among the Greeks, “not altogether discredited by the Turks,” that the building would be restored to Christianity. As Ottoman control of its European territories crumbled, the restoration of Hagia Sophia to Christianity was a strongly-held hope and widely-felt belief.

St. Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey, 1914. (Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum Archives)

St. Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey, 1914. (Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum Archives)One of the correspondents whose name turns up again and again—and regularly in reference to Hagia Sophia—is William T. Ellis, a fervent Presbyterian from Swarthmore, PA, whose weekly Sunday School lessons were syndicated. As a newspaper correspondent for the New York Herald, he traveled widely, in Bible Lands, as well as in Russia in 1917 to observe the Bolshevik revolution, followed by Cairo and Constantinople, and ultimately Paris for the Peace Conference. As might be expected, there is little distinction in his writings between religious doctrine and reportage. On 10 December 1910, he published the International Sunday School Lesson on the Crucifixion, which was widely distributed by the American press. For him it was a quick leap from the Crucifixion, to the sign of the Cross, to the wish for a cross atop Hagia Sophia:

The Turkish problem, which engrosses the attention of European diplomats and is intertwined with the future of Greece, Crete, Bulgaria, Servia, Montenegro, and Roumania—not to mention the nationalities under Turkish dominion—is essentially a problem of Islam versus Christianity. Greeks, Russians, Armenians and Syrians see it all typified in the cross coming back to the mosque of St. Sophia in Constantinople … For nearly five centuries it has been in the hands of the Moslems. But the belief is strong in millions of hearts that ‘the cross is coming back.’ When it does, the Turkish empire will have fallen.

These are strange sentiments to be expressed in a Sunday School lesson, but they demonstrate how religion and politics were inextricably intertwined.

With the penetration of Bulgarian forces into Ottoman Thrace during the second Balkan War, anything seemed possible, and the conquest of Edirne was taken as a prelude to the conquest of Constantinople, the liberation of Hagia Sophia, and the triumph of Christianity. As Bulgarian troops advanced in the fall of 1912, the New York Times published a long article captioned, “Bulgars May Plant Cross on St. Sophia. Byzantine Edifice, where their forefathers were made Christians, goal of fighters.” The report is much more concerned with popular sentiment than with military strategy, troop movements, or even the basic facts on the ground. Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria was said to have prepared his regalia for a triumphal entry into the city, to be followed by mass in Hagia Sophia, envisioning himself as Emperor of a united Christian East. None of this came to pass; by July the Bulgarian army was in retreat, both armies decimated by a horrific outbreak of cholera. And then World War I began.

Following the end of the war, as the Peace Conference was meeting in Versailles, ardent philhellenes across England formed the St. Sophia Redemption Committee, supported by major political figures of the day, including nine Members of Parliament. Its manifesto reads in part, “If, for no selfish ends and regardless of the cost, she [England] now proceeds to set the Cross again upon the dome of the great church, she will kindle a beacon of peace and of progress which will change the face of the earth and the ways of men.” The tone of the group was decidedly pro-Greek and anti-Turkish, pro-Christian and anti-Muslim. For many, the hope of the Peace Conference was to drive the Turk out of Europe once and for all.

After 1922, the discussions about the religious fate of Hagia Sophia cease, and there is virtually no mention of the church vs. mosque controversies in the reports of the Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923, as the Kemalist regime gained control of the city. On 24 November 1934, the same day that Mustafa Kemal was proclaimed Atatürk, the Turkish Council of Ministers decreed that the building should be a museum:

Due to its historic significance, the conversion of Ayasofya Mosque, a unique architectural monument of art, located in Istanbul, into a museum will please the entire Eastern world; and its conversion to a museum will cause humanity to gain a new institution of knowledge.

We may never know the chain of events that ultimately led Mustafa Kemal to this decision. Was this a compromise with the Allied forces, or simply part of his vision for a Westernized republic?

Through its rich history, Hagia Sophia has become deeply embedded in competing narratives of national, regional, religious, and cultural history. As a part of its human rights policy, UNESCO has attempted to define both the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of humanity deemed worthy of protection. With a monument as symbolically loaded as Hagia Sophia, there is always a danger of accepting a majority narrative that would silence all other histories. Selective readings of cultural heritage can effectively erase historical memory and sever links with the past. As a monument on the world stage, Hagia Sophia has become a repository of many collective memories. It should be allowed to maintain multiple meanings, to resonate with multiple narratives and multiple histories for its many diverse audiences.

Feature image: Inside Hagia Sophia, Istanbul by Jeison Higuita via Unsplash.

The post The reconversion of Hagia Sophia in perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Do you feel sorry for first year university students?

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Said by Dickens many years ago but with eerie relevance to our current situation.

The global pandemic is itself an overwhelming health tragedy. Moreover, it has laid bare so many other local, national, and global issues that have been simmering beneath the surface. To name but a few: health systems that treat the sick—if they can afford it—rather than social systems that maintain and promote health; online communities that replace a sense of local community, but lead to isolation, loneliness, and associated mental health impacts; food systems that embrace mass-grown, cheap, convenient, often carbon-intensive, and always-available products, with local producers, biodiversity, climate stability, and sometimes even nutrition suffering.

It sounds like the worst of times.

So what makes it the best of times?

For some, the pandemic has allowed a moments’ pause. Those of us in the UK have clapped for a health system—and the people who comprise it—which is blind to wealth. Communities rallied around those vulnerable or being shielded with some talking to neighbours for the first time. Local food suppliers became heroes and saviours, and supermarket workers became essential workers, valued for their contribution to our daily survival. But these “best of times” moments feel fleeting, and are fading, as they were always going to, as the economic impact of the pandemic starts to emerge, augmenting the already unequal societies and communities, who have never overcome the disadvantages of poverty, race, country of birth, or access to resources: more bubbles simmering beneath the surface that were always going to break through, at some point.

And into this maelstrom, we see a generation of young adults taking their places at university, many for the first time. And I hear those in my generation saying, “I feel so sorry for students starting university during Covid—their experience will be completely different.”

Do I feel sorry for these young adults?

Yes, and also no.

I suspect these comments are linked to regrets that these young adults won’t experience the quintessential university “freshers” week and first year of socialising, drinking, experimenting with new identities, and new relationships. But this already wasn’t the experience of so many for whom university was—and is—a serious opportunity to make a better life for themselves and their families. Individuals for whom education is a gateway to a better future, rather than a venue for socialising and drinking. That issue of a better future, I’ll come back to.

But also, this is not the first—and certainly won’t be the last—generation of students to start university in times of great societal upheaval. Here at the University of Edinburgh we talk about this not being our first plague, as we work to maintain access to university education for all, made possible for the first time in history, because of the technology we can leverage. In the 1600s, a number of universities closed due to plague, and students were sent home with just books to read and questions to think about. And while Newton may have used the time productively, how many other students struggled without formal instruction? But we don’t even have to look that far into history.

At the moment I’m reading about The Philosopher Queens (Buxton and Whiting, 2020) Iris Murdoch, Mary Midgely, Philippa Foot, Mary Warnock, and Elizabeth Anscombe who were given the opportunity to study—and come of age—as philosophy students in the 1940s because so many of the young men were away at war—and many never returned. A tainted silver lining of the “golden age of female philosophy” (Buxton and Whiting, 2020, p. 105) made possible by a continent ripped apart, mass genocide based on race and religion, and a generation of young men never to return to their homes.

Even more recently, my own Australian father remembers vividly the moment his date of birth, 11 January, was literally pulled from a barrel, and all men born on that day 18 years previously won the dubious prize of being conscripted to fight in a war he knew nothing about, against an enemy he didn’t understand, in a country he had barely heard of: Vietnam. Given a temporary reprieve because he had a scholarship to attend university—the first in his family ever to do so—he watched as his school mates were shipped out. He studied his whole degree with a black cloud over him: once his degree was awarded, if he passed his army medical, it may all be for nothing if he was dropped with a machine gun into a jungle. He remembers attending that medical, surrounded by young men inducing vomiting to try to be deemed medically unfit, while his own terrible eyesight was literally what saved his life. And as he left that hall, he passed other young men walking, hand in hand, up to the army officers and turning to each other to share a kiss. Another tainted silver lining: being ostracised from society simply because of who you loved but using that as a shield to be deemed unworthy for army service.

I do feel for our current generation, but not because of the constraints on their pub nights and socialising, or because this is the first generation to ever face such hardship. I feel sorry for them because of the world they are inheriting, because of how much weight and responsibility we are placing on their shoulders, because of the serious societal issues that we have at best been ignorant of and at worst have wilfully ignored. Political dissent resulting in torture? Not a history lesson from WW2, but a news story in Europe today. Accusations of voter suppression and electoral fraud? Not a dictatorial regime in a developing nation, but the world’s “greatest democracy.” Lack of educational attainment due to socioeconomic deprivation? Again, not a developing nation but an ongoing and persistent story here in my own home in the UK, made even more heart breaking as an algorithm exacerbated that disadvantage. And I haven’t even mentioned the looming ecological crisis with climate change, biodiversity loss, and sea-level rise changing the way humans live on this earth for ever and catastrophically if we don’t act immediately to prevent widespread ecosystem breakdown. This is what they will inherit. As Greta Thunberg asks: how dare we?

While this sounds pessimistic, I have optimism also. And that optimism comes from those same students others deign to feel sorry for because my career gives me the privilege of working with bright, enthusiastic, socially-aware, environmentally-conscious, hard-working, and aspirational university students. For many years this was mostly with postgraduates, who elected to do my courses in sustainability and climate change because of their interest. But four years ago my Dean asked me to be ambitious and aspirational in designing a new first year compulsory course, for our undergraduate students. One of the visions of such a course was to help them transition into university, so that they could make the most of the opportunity, and then more successfully transition out into their graduate lives. My course, Global Challenges for Business, lays a foundation for the global context of their chosen discipline—business studies. But while my students enjoy exploring the social, digital, and environmental disruptions which are challenges for business, it is the skills and transition element of the course that has been transformational.

I realised early on that I was expecting these young adults to move away from the “learn and repeat” approach of school-based learning, and to think by and for themselves. And yet I could find no effective resources to help with this practical approach to critical thinking. Most urgently, I needed them to understand that not only did they have permission to think for themselves, but that that is precisely what university education is for. That is, they needed to understand why they were at university. Moreover, they needed a structure to understand the aims of critical thinking: of developing quality arguments with logical reasoning, of supporting this with strong, reliable evidence, and of communicating this clearly for their own purposes and to engage with others. And finally, no one I could find was explicitly teaching students how to master the tools of such an approach to thinking. The tools we can use and improve to understand and interpret others’ voices (through active reading and active listening), and to develop and express our own voices (through speaking-to-think and writing-to-think). In teaching my students in this way, I achieve a transformation from bright but passive consumers of knowledge, to engaged and inspired creators of knowledge.

Because if we can pass on one thing to support young adults as they face the world they will inherit from us, it is to help them become critical thinkers: to understand the problems and develop workable solutions. And by doing that, we won’t have to feel sorry for them. We will feel proud of the future citizens we have helped to create.

Featured image by Pang Yuhao via Unsplash

The post Do you feel sorry for first year university students? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 7, 2020

Smaller prisons are smarter

The There is a growing consensus across the political spectrum that the United States incarcerates far too many people and that this has tragic and unjust consequences that fall disproportionately on disadvantaged socioeconomic and minority communities. Yet, not only do we lock up too many people, but all too often they are incarcerated in prisons that are also much too large. Prisons should instead be built to hold significantly fewer people. The prison system in England and Wales provides a helpful example to demonstrate why smaller prisons are better.

Smaller prisons offer several advantages. Officials can govern smaller prisons more easily. It is less likely that large groups of prisoners will challenge officials’ authority and control. Officials can more easily see prisoner interactions in places that are less crowded. In smaller prisons, officers and prisoners can more easily get to know each other and develop respectful relationships. Smaller prisons tend to have less bureaucratic hierarchy, leading to greater responsiveness to prisoner needs. Larger prisons require more regimentation, and they tend to take on an assembly line quality and the sense that officials are merely warehousing offenders. Smaller prisons often have more opportunities for privacy and autonomy, leading to less conflict. Prisoners recognize this too: prisoners report that in smaller prisons, they feel less stress, safer, and more respected by staff.

In smaller prison populations, prisoners can also resolve problems among themselves more effectively in informal ways. Gossip and ostracism are powerful tools of social control in small communities. It hurts when someone disapproves or disrespects you. It hurts when no one will associate with you. One British prisoner tells sociologist Coretta Phillips about the social dynamics of the prison, explaining “with like 50 of us that’s been on this wing for ages, we all know each other, it doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, Indian.” The small size of the facility means that they know each other and ethnic divisions are not strong. To be shut out of this community would be painful. But, these tools become less effective as the size of the community grows. Gossip is less hurtful if no one knows anyone else’s reputations. Ostracism is not a credible threat if there are many other prisoners with whom to associate. In large prison populations, by contrast prisoners often turn to organized prison gangs to exert control. In smaller prisons, people rely on softer, less violent ways of establishing order among prisoners.

Consider the California prison system, which is the second largest prison system in the United States. The typical prison in California holds about 3,500 people. Ethnically-segregated prison gangs have a dominant influence on the everyday life of prisoners. They have written rules and regulations that prisoners must follow. Many gangs even have written constitutions. They regulate social interactions and regulate and tax the underground economy. They rule with the threat of violence. One formerly incarcerated person from California describes how gang leaders ordered an assault, “I knew this guy that ran his mouth a lot, made lots of problems, called people names and stuff… He’s a loose cannon, he’s going to cause trouble you know what I mean, we work hard to keep that race shit calm and here is this prick causing trouble, no one wants that so we had to check him. We took him down a peg or two, it came right from the top, the asshole needs a lesson.”

Yet, gangs have not always existed in the California prison system. For more than one hundred years, no prison gangs existed. Instead, prisoners relied on the “convict code,” a set of informal norms that determined one’s rank in the social hierarchy. The code told prisoners not to lie, steal, or snitch. It told prisoners to be tough, not to whine, and to pay back one’s debts. The more someone adhered to the code, the more his peers respected him and the safer he was. Prisoners who deviated from the code were ostracized and more likely to be victimized. But, this system could only work when prison populations were small and people knew others’ reputations.

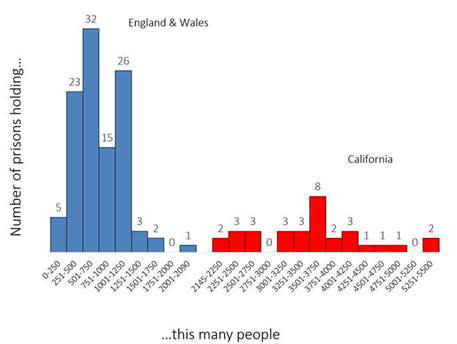

England adopted many penal practices and criminal justice policies from the United States, including mandatory minimum sentences, three strikes laws, honesty in sentencing policy, zero tolerance policing, the drug war, a national drug czar, drug courts, juvenile curfews, private prisons, and electronic monitoring. However, their prisons are not controlled by prison gangs like those found in California. One reason for that is that the typical prison there only holds about 750 people. The figure below shows how many facilities hold different numbers of prisoners in each prison system. For example, England and Wales have 32 prisons that hold between 501 and 750 people. By contrast, the most common size prison in California holds between 3,501 and 3,750 people. California has a few, incredibly large prisons, while England and Wales have a large number of relatively small prisons. For comparison, the largest prison in England and Wales still holds fewer people than the smallest prison in California. The largest prison in California holds more than double the number of people held in the largest prison in England and Wales. These are radically different approaches to incarcerating people.

The number of prison facilities and inmates per facility in England & Wales and California

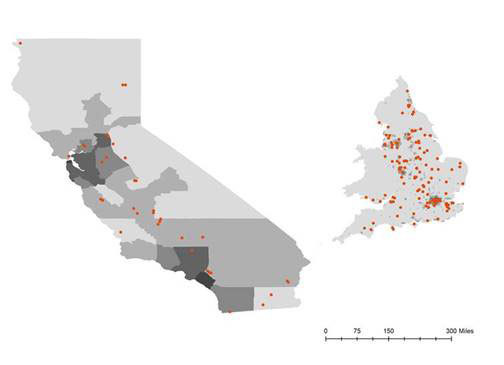

The number of prison facilities and inmates per facility in England & Wales and CaliforniaThe small prisons in England and Wales have an additional advantage: they are sited close to a prisoner’s home. This is based on a correctional philosophy that incarcerating people close to their hometowns allows people to maintain healthy ties with family and friends. It also means that social norms are even more important. A person’s reputation is often known as soon as he arrives at prison. Criminologist Ben Crewe reports on how reputations spread across social networks at Wellingborough prison, where one prisoner explained, “The first things you ask someone new are where they’re from, which jail they’ve come from, and what they’re in for. Then you drop some names, and if they know them they’re alright.” While incarcerated, friends and family back home might also hear about one’s behavior. After release, one’s actions while incarcerated will be known to many back home. Taken together, this means that maintaining a good reputation is incredibly important so prisoners are heavily influenced by social norms. They do not need gangs to govern and control social and economic interactions. The prison system is able to house people closer to home, in part, because England and Wales has about three and a half times as many prison facilities as California does, and they are spread throughout a geographic area that is only about a third of the geographic size of California. As a result, it is far easier to incarcerate a prisoner closer to his or her home.

The geographic spread and number of prison facilities in California and England & Wales

The geographic spread and number of prison facilities in California and England & WalesTo be sure, we should be greatly concerned about the total size of the US prison population. Given the incredibly high rates of incarceration, the prison population could certainly be reduced substantially without risking increasing crime rates. However, we should also place greater importance on reducing the number of people held in particular facilities. Smaller is better.

Feature image by Emiliano Bar on Unsplash

The post Smaller prisons are smarter appeared first on OUPblog.

Introducing Shakespeare to young readers

No one has a duty to like Shakespeare, just as no one is obliged to prefer coffee to tea, or classical music to pop, or soap operas to documentaries. On the other hand, just as it is highly inconvenient to know nothing about the internet, or how to boil an egg, so it is liable to cause problems, and to be a source of embarrassment, to know nothing about Shakespeare. He is all around us, on the television and the radio, in films and in newspapers, in popular as well as high culture. All this makes it inevitable that educators feel that people should be introduced to Shakespeare at an early age, that his writings should be taught in schools, and that young people should be encouraged, even required, both to learn something about his life, his times, and his writings, and to experience his plays on the page and on the stage, on films and on television, at first hand or in mediated form.

The problem for teachers is to decide when to introduce their students to Shakespeare’s work, and in what way to do so. The easiest and cheapest way is through the printed word, by getting them to read plays either in mediated form, such as prose retellings, or through direct exposure to the texts themselves. The Lambs’ Tales from Shakespeare have been an incredibly popular introduction to Shakespeare ever since they first appeared, early in the nineteenth century, and generations of aunts and uncles have bestowed them upon the innocent young with well-meaning benevolence. Umpteen editions, many of them illustrated, some even annotated, are still on the market, advertised as classics in their own right. I find them patronising in tone, tediously moralistic, and stylistically outdated and should steer children well away from them. If direct contact with the original texts is regarded as initially unpalatable, more modern retellings such as Leon Garfield’s Shakespeare Stories, or, for the very young, the BBC series of half hour animated films, or even comic strip versions with lurid illustrations – some of which give complete texts in their speech bubbles – may be preferable.

Encouraging children to see feature films based on the plays, or theatrical productions, might seem to be an ideal introduction, but it has its hazards. Taking a group of thirty or so young teenagers to undergo what they may see as a compulsory indoctrination to a cultural experience tends to bring out the worst in them, their resentment expressed in derisive mob behaviour. I have vivid memories of a matinee of Macbeth at Stratford ruined for me because I was seated in the midst of a group of young people who lounged, chewed, giggled and chatted through the performance with no regard for their fellow theatregoers.

“It is indeed worth making an intellectual and imaginative effort to enter the magical worlds of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Macbeth, The Tempest, Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and all the other masterpieces that are there for the asking.”

No, there has to come a point at which there is nothing else for it but to sit the pupils down in a classroom with their books before them and a teacher to take the lead. Even at this stage there are various possible techniques. Reading round the class with no allocation of individual roles, and with interruption for the explanation of difficulties, can be a pretty deadening experience, slowing everyone down to the pace of the least confident readers. Slightly better is class reading with allocation of individual roles, but that is liable to lead to accusations of favouritism and to boredom on the part of those who get only minor parts. Acting scenes out in front of the class by selected pupils can be more fun. I have vivid memories as an eleven-year-old of standing, book in one hand and a ruler (in place of a sword) in the other, while reading Brutus with a fellow-pupil as Cassius in the fight scene from Julius Caesar. But I’m glad it wasn’t the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet.

But for me, and I’m sure for many others, the key factor in developing an interest in Shakespeare – in my case one that has inspired a long lifetime’s dedication to his works – is an inspirational teacher. Let me name him: E. J. C. – known familiarly to his pupils as Josh – Large, of Kingston High School, Hull, during the 1940s. He would allocate roles among members of the class – not allowing any sense of false modesty to deter him from taking the leads himself – and we would read aloud with as much attempt at dramatic effect as we could muster, stopping only when difficulties had to be explained. Mr Large’s enthusiasm, his passion for the texts we were studying, and his ability to transmit this to receptive young minds, opened the way to previously undreamt-of imaginative landscapes and ultimately, for me at least, to a lifetime of both personal and professional engagement with Shakespeare. It had a similar effect on others too. Another of Mr Large’s pupils was the actor Sir Tom Courtenay, who has played many leading Shakespeare roles.

Obviously, study of the texts requires editions of the plays themselves. At one time editions intended for schools were regularly expurgated and annotated as if they were classical texts, with notes on grammar and etymology, paying no attention to their theatrical qualities. Happily that has changed. Editions specifically prepared with young people in mind are readily available, and teachers often work with editions prepared for a general readership. Here, as General Editor of such an edition, I have to declare a special interest. In determining the editorial principles for the editions of plays now marketed under the banner of World’s Classics, I determined that in so far as possible they would, while aiming at the highest standards of scholarly excellence, avoid scholarly and critical jargon and present their texts with introductory material and annotations that paid full regard to their theatrical qualities and to the multiplicity of significance that they have revealed in performance over the centuries since they were written. Teachers armed with editions such as these, and fortified with their own skills and enthusiasm, can step forth in the strong hope of convincing even recalcitrant students that, whatever rival attractions there may be, it is indeed worth making an intellectual and imaginative effort to enter the magical worlds of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Macbeth, The Tempest, Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and all the other masterpieces that are there for the asking.

Feature Image Credit: Macbeth: First Folio by Matt Riches via Unsplash.

The post Introducing Shakespeare to young readers appeared first on OUPblog.

September 6, 2020

What does a linguist do?

Linguists get asked that question a lot. Sometimes by family members or potential in-laws. Sometimes by casual acquaintances or seatmates on a plane (for those who still fly). Sometimes from students or their families. Sometimes even from friends, colleagues, or university administrators.

It turns out that linguists do quite a lot and quite a lot of different things. Many academic linguists do research on sound structure, grammar and meaning, language acquisition, language use or the history and structure of a particular language. Some linguists teach linguistics, or foreign languages or English as a second language (ESL). Careers in ESL or TESOL (as it is also known) can be as close as your own community or can take you around the globe.

Beyond teaching, linguists are involved in a wide variety of careers in which a knowledge of how language works is important. Expertise in linguistics is often combined with knowledge of engineering or computer science: linguists work on metadata and programming for language and data mining, on speech recognition and speech synthesis, and artificial intelligence. If you are able to ask your phone or computer a question, linguists were involved somewhere.

Speech pathology is another career in which you’ll find linguists, especially ones with some expertise in anatomy and physiology or neuroscience. Working with clients struggling with speech disorders can be intellectually and emotionally fulfilling, and it entails prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of a wide range of issues—from speech production to aphasic disorders to problems related to cognition and language development.

Linguists also work in the performing arts, as dialect coaches for films and videos or as voice or accent choices for public speakers. If you remember a film that had particularly authentic regional or period speech, it is a safe bet that a linguist coached the actors. Some linguists even develop artificial or constructed languages –conlangs—for games, films or fantasy worlds: Klingon, Dothraki, High Valyrian, take your pick.

Linguists may serve the public interest, by helping to document, preserve, or revitalize endangered dialects and endangered languages or by training teachers and developing curriculum materials. They may work in government service analyzing codes, documents, texts, or tapes for national security. Some linguists work on matters of public and consumer safety, helping to make messages clearer, fairer, and more inclusive.

Forensic linguists specialize in matters of law: from criminal investigations that involve author identification or voice identification to the analysis of trademarks, threats, and hate speech. They may also contribute to making the legal process fairer by analyzing the way language works in the courtroom and how juries, witnesses, and judges understand and use language. Linguists testify in court and before Congress on matters of language and have been cited in Supreme Court cases.

Linguists with some expertise in writing may work as technical writers or editors, putting their knowledge to work clarifying the writing of others, preparing materials for publication, or developing technical standards for business and professional documents. Marketing and advertising are also fields where linguists contribute, often by research on comprehensibility or on product names, but also as cross-cultural experts working on multicultural marketing.

And of course linguists work as translators and lexicographers. They may also work with museums, developing exhibits and material on history, dialects, speech, or particular language families. From the National Museum of Language in Maryland to your local science or history museum, linguists help to design exhibits that educate people about the way they speak and the ways that language works.

Doing linguistics means breaking professional knowledge down, showing how it relates to everyday life, and showing why it is fascinating. Linguists do this in the classroom, through books and articles, podcasts and videos. Some linguists even write blogs about language and linguistics. A few of my favorites are All Things Linguistic, the Language Log, Superlinguo, Separated by a Common Language, and Grammar Girl. Check them out to discover more things that linguists do.

Featured Image Credit: Work Flow by Christin Hume via Unsplash

The post What does a linguist do? appeared first on OUPblog.

Six books for budding lawyers [reading list]

In celebration of National Read a Book Day 2020 today, here are a list books for anyone working in, or interested in, the legal world. Studying for a law exam, or just looking for a court-based drama? Take a glimpse of the titles below and select one for yourself.

My Brief Career: The Trials of a Young Lawyer by Harry MountThis is a book that I have come back to many times. Funny, well-written, and enlightening, Mount recounts his own personal experiences of pupillage in a barrister’s chambers. Far from reflecting the charm and magic that the Inns of Court have always tended to evoke, however, Mount’s story is one that involves a difficult relationship with a pupilmaster, noisy disturbances from workers on an adjacent site and competition with a fellow pupil who ultimately pips Mount to tenancy. A good book for readers seeking a light-hearted but very real account of the challenges of training at the bar in the United Kingdom.In Your Defence by Sarah Langford

This book is about eleven different cases in which Langford as served as defence counsel. Through these accounts, Langford offers a thought-provoking insight into the troubles and challenges of everyday people faced with the traumas of legal action. Cases range from those involving criminal charges of sexual activity in a public lavatory to family cases exploring questions surrounding the welfare of children. Lions under the Throne by Stephen Sedley

A somewhat more academic text than others on this list, this book, written by a retired Court of Appeal judge, Sir Stephen Sedley, provides a valuable history of English public law. Public law underpins the entire fabric of a country’s legal system, comprising principles and values that provide the foundation for law-making, government, due process and relations between citizens and the state. This is a great book to dip into for discussion of a broad range of issues and topics; I particularly like the way Sedley explains the development of public law in the context of broader British history. Budding lawyers must tackle public law during their studies. This book offers a perfect account of the subject and its historic underpinnings.The Innocent Man by John Grisham

Though Grisham is better known for his crime thrillers, The Innocent Man is Grisham’s first non-fiction book, telling the true story of Ron Williamson. Williamson was wrongly accused of murdering a waitress and, despite no substantial evidence, he was convicted and sentenced to death. After constant efforts to prove his innocence, and at one point getting as close as five days from a scheduled execution, Williamson’s innocence was eventually determined by DNA evidence. He was released from prison after 11 years on death row. Miscarriages of justice are a very real danger in legal systems across the world. Those dangers become more pressing where imposition of a death penalty is involved.My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ginsburg was sworn in as an associate justice of the US Supreme Court in August 1993, appointed to the court by President Bill Clinton. This book comprises various selected writings including speeches, academic papers, lectures and judgments. The attraction of this book lies in the incredible mark that Ginsburg has made on the legal world. Though she has set out many an important judgment, particularly those offering more liberal perspectives, it is her role as a leading woman in the law that is most notable. When Ginsburg started out at Harvard Law School, less than 3% of the US legal profession was female. Through her incredible career this is an inequality that Ginsburg has relentlessly fought to address, becoming a bastion of gender equality and the role of women in the law. Lives of the Law by Tom Bingham.

Tom Bingham was a senior law lord in the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords until 2008, when the UK Supreme Court was created. Bingham was one of the most prominent judges of his generation and a leading figure in the field of public law, sitting in the highest UK court during some of the most important constitutional reforms of the last century. This book is a collection of Bingham’s speeches and essays during the first decade of the 21st century, not only offering insight into some of the thornier issues prevalent in the modern UK constitutional and governmental system, but eloquent discussion of some of the key figures that underpin and share those debates.

These books provide a very diverse selection of text to read to understand and discuss various aspects of the legal profession. While no doubt the average law student is rather seriously occupied when studying for examinations, there’s always time for a little outside reading.

Feature Image Credit: by Giammarco Boscaro via Unsplash

The post Six books for budding lawyers [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

September 5, 2020

The defacing of Churchill’s statue

During Britain’s strange summer of 2020 the statues of long-dead figures became live political issues. Black Lives Matter protesters threw slave-trader Edward Coulston’s effigy into Bristol harbour, an act that shocked many, but that was as nothing to the reaction provoked by the treatment meted out to Winston Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square. During another Black Lives Matter protest this was daubed with the claim that the wartime prime minister—voted the Greatest Briton in 2002—was a racist. The Daily Express said the statue had consequently been “desecrated.” A week later far-right demonstrators, many of them associated with racist views, gathered near the statue, ostensibly to defend it from further attack, some of them chanting “Sir Winston Churchill, he’s one of our own.” By then however the statue had been boarded up and hidden from view.

Some saw the defacement of Churchill’s statue and the response to it as another episode in Britain’s culture wars, an unwelcome development in the country’s increasingly fractious politics. But the statues of great figures have always been political, their sponsors invariably hoping to impose their view of the notables’ significance onto the future, to keep them in some way permanently alive. Yet such statues even at the moment of their creation can be subject to contestation: the Churchill statue’s 2020 defacement is not as novel an act as it might at first appear.

After Churchill retired from front line politics in 1955, his supporters put up numerous statues and other memorials intended to make permanent their preferred remembrance of his wartime role as the nation’s saviour. Most notably, soon after Churchill’s 1965 state funeral, the House of Commons commissioned a statue to be placed in the Members’ Lobby. When the House unveiled the statue in 1969, according to the Guardian correspondent, “there was an audible intake of breath” from those present. “It was,” he went on, “for all the world as though Churchill had himself thrown off his coverings by taking a sudden step forward. There he stood once more… avid for new burdens.” Indeed, such were the statue’s presumed magical qualities it quickly became the practice of Conservative MPs to stroke its left foot for luck, something responsible for the foot being almost worn away.

Even before that effigy was completed, in 1968 Conservative MP John Tilney started the process which would end with Churchill’s Parliament Square statue. Tilney called for the creation of another likeness “of perhaps the greatest leader of this nation and the greatest Parliamentarian for centuries.” The reaction to Tilney’s suggestion however revealed the partisan nature of his request. Then Prime Minister Harold Wilson was reluctant to endorse the sentiment and so dissembled.

But, reflecting the enmity in which Churchill the class warrior—as opposed to national saviour—was held amongst South Wales miners, Labour MP Emrys Hughes sarcastically questioned whether another statue was “absolutely unnecessary because nobody can forget him?” Undeterred, Tilney raised the matter a few months later. Wilson remained unwilling to back the project and refused it state funds but promised to facilitate the statue’s construction should broad support be made evident, which he doubted.

When the matter was raised in the second chamber the Labour leader of the Lords, Lord Shackleton, claimed to be not unsympathetic to the initiative, but then proceeded to list all the memorials then dedicated to Churchill, clearly implying another one was unnecessary. But another Labour peer, Lord Blyton, a former miner, was more direct in his criticism of the scheme, pointedly stating that, “I think we should remember that he [Churchill] did not win the last war by himself. He had men like Clem Attlee and Ernie Bevin.”

After Tilney received the support of 150 MPs, and various other worthies, Wilson was however obliged to endorse the formation of a committee to oversee the creation of a statue, which was unveiled in November 1973.

Since then, and especially after the turn of the century, Churchill’s statue has regularly been defaced or subject to lèse-majesté as perspectives about his contribution to British history have changed. During London’s May Day protests of 2000, someone placed a strip of grass on the statue’s head to give the impression Churchill sported a Mohican haircut.

Those responsible evaded the police but James Matthews, the 25-year-old former soldier who sprayed the statue’s mouth with red paint (so it looked as if blood was dripping from it), did not. To him, “Churchill was an exponent of capitalism and of imperialism and anti-semitism. A Tory reactionary vehemently opposed to the emancipation of women and to independence in India.” Ten years later, in what the Daily Mail described as an attack on “respect and common decency,” young protestors at a demonstration against an increase in university tuition fees showed what they thought about Churchill by urinating on the statue’s plinth. In 2012, in order to highlight problems associated with mental illness, campaigners placed a straightjacket on the statue in recognition of Churchill’s increasingly well-known bouts of depression.

Even before it was unveiled, Churchill’s Parliament Square statue was the subject of dispute. Those well-placed figures who regarded him as the man who single-handedly saved Britain from defeat at the hands of Nazi Germany prevailed. But their view of Churchill’s place in history—and of the character of Britain itself—was always contested. Similarly, culture has been a constant political battleground: the events of the summer of 2020 are not so unique after all.

Feature image by Arthur Osipyan via Unsplash

The post The defacing of Churchill’s statue appeared first on OUPblog.

September 4, 2020

How text messages are helping people fight counterfeit medicine in Africa

According to World Health Organization statistics, 42% of detected cases of substandard or falsified pharmaceuticals between 2013-2017 occurred in Africa— substantially more than on any other continent. Poor, underdeveloped countries experience a penetration rate of approximately 30% of counterfeit pharmaceuticals as opposed to less than 1% in developed countries.

In Ivory Coast, Adjame, the biggest street market of fake medicines in West Africa, alone accounts for 30% of medicine sales in Ivory Coast. No medication is spared, with counterfeiters producing a full range of fake pharmaceuticals including antibiotics, pain killers, HIV/AIDS, cancer, and diabetes treatments.

This illicit trade has dramatic consequences, namely increased bacterial resistance to effective medicines, longer hospitalisation and treatment time, and widespread loss of life. Counterfeit antimalarial medicines kill around 64 000 to 158 000 people in sub-Saharan Africa every year. In March 2019, only a few weeks after the launch of a campaign in Niger to inoculate six million children against meningitis, the health authorities warned the population to remain vigilant over a counterfeit version of the vaccine.

With the African pharmaceutical market projected value rising from $45 billion in 2020 to an estimated $56-70 billion by 2030, trade in counterfeit pharmaceuticals will become more lucrative and consequently attract a greater number of criminals. If one adds in high poverty rates, low risk of detection and prosecution, weak penalties, trusting consumers and the tolerance of a parallel pharmaceutical trade, the problems caused by counterfeit and falsified pharmaceuticals in Africa are most likely to increase over the next decade. As a collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa, the delivery of other health services is disrupted, resulting in a loss or interruption of access to regular medication, including antiretroviral therapy refills. As access to medications from reliable sources decreases, a significant rise in counterfeit pharmaceuticals in Africa is anticipated.

Various types of counterfeit drug detection devices are available on the market, but these are often prohibitively priced for widespread use in most African countries. Rising to the challenge, African entrepreneurs are proposing innovative technological measures that allow for a quick and cheap verification of the genuineness of a drug. With more than three-quarters of the population in sub-Saharan Africa having a mobile phone connection (747 million people), of which a third (250 million) have a smartphone, it is no surprise that many of these innovations are based on mobile technology and text message identification. Since July 2017, Malian consumers may verify the authenticity of a product by sending a verification code on their mobile phone to the phone company. In Nigeria, more than five million pharmaceutical products have scratch cards attached. Scratch-off codes are now mandatory on malaria drugs and some antibiotics. Once scratched, a one-time use code is revealed. The customer sends the code via text message to a toll-free number and immediately receives a response as to whether the drug is real or fake. If the drug is fake, the patient receives a hotline number to report the counterfeit drug. This notification system is also available in Kenya and Ghana.

Beyond the obvious benefit of text message identification to the consumer, the data collected allows pharmaceutical companies to track locations where occurrences of counterfeits are common and is used to trace offenders. Where a genuine authentication code was checked more than 1500 times in a few days, the service provider quickly identified that a genuine code had been replicated and applied to thousands of counterfeit emergency contraceptive pills. Using the contact details provided through the verification system, the service provider was able to contact every person to ascertain where the pills were bought and alerted authorities and regulators for further action.

While there have been no studies on the positive impact of those mobile technologies, in Nigeria the local food and drug administration authority responsible for the quality of products such as drugs, chemicals, medical devices and foods reported a decrease in the prevalence of counterfeit drugs from 64% to 3% after the introduction of a combination of technological means from text message identification, hand-held analysers that identify goods through sealed packaging in a matter of seconds, to radio-frequency identification tags which identify individual items and track movement through the supply chain.

With mobile technology already allowing for such impressive results, the growing interest of African entrepreneurs for blockchain technology to authenticate the supply chain is exciting news for the continent. Similarly, the technological advancements experienced in the building of COVID-19 tracing apps, to trace, identify, and notify all those who come in contact with a person infected with the coronavirus, can be harnessed and used for the identification and tracking of supply chains for counterfeit and falsified pharmaceuticals in Africa going forward.

Featured Image Credit: Christina Victoria Craft via Unsplash.

The post How text messages are helping people fight counterfeit medicine in Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

September 3, 2020

Searching for “magic bullet” antibodies to combat COVID-19

Several cases of mysterious pneumonia (now called COVID-19) were reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China in late December 2019. SARS-CoV-2, a novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, was later identified. In the past eight months, COVID-19 cases have been reported in 188 countries all over the world, with over 20 million confirmed cases and 760,000 deaths.

Coronaviruses have infected humans and have caused three major outbreaks—SARS, MERS, and COVID-19—in the last two decades. All of them might be transmitted from animals such as bats. COVID-19 has caused significant damage to public health, world economy, and every aspect of our life on the Earth. If the last two coronavirus outbreaks (SARS and MERS) did not stimulate a profound global awareness for deadly coronavirus infection, the current pandemic has certainly called for scientists from all areas of expertise to work relentlessly in solving the most unprecedented health crisis in modern medical history after the 1918 pandemic flu.

One major effort scientists have been making to combat this virus is to generate so-called antibody drugs capable of neutralizing the virus. Our body can produce potent proteins that attack “foreign” dangerous pathogens, such as viruses. Individuals with COVID-19 may produce antibodies that can inhibit or even neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Based on this observation, scientists have used cutting-edge cell and molecular biology techniques, including single cell sorting and cloning, to identify such precious antibodies from these individuals. In other cases, scientists have identified anti-virus antibodies from genetically engineered mice, called transgenic mice, that produce human antibodies as part of the mouse immune system. Currently, eight antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including LY-CoV555, REGN-COV2 and JS016, are being tested in human clinical trials for treating COVID-19. On the research frontier, scientists are also using a genetic engineering technique called phage display technology to isolate antibodies using a bacteria system. A combination of two (or more) antibodies that recognize different parts of the virus might be the most effective approach. A cocktail therapy (for example, REGN-COV2) combining two antibodies targeting different parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is currently being tested in a clinical trial. If successful, antibody drugs can be useful for treating COVID-19 in infected patients and preventing spread in high risk populations such as frontier workers, including doctors and nurses, seniors and/or those with chronic diseases.

As researchers continue this vital work to deliver “magic bullet” antibodies to combat COVID-19, The Chinese Antibody Society and The Antibody Society have collaboratively launched the COVID-19 Antibody Therapeutics Tracker program to provide real-time, free, open access to the online global database tracking ongoing COVID-19 antibody development in clinical as well as preclinical testing, to the medical community and general public.

Image: Virus via Pixabay

The post Searching for “magic bullet” antibodies to combat COVID-19 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers