Etymology gleanings for July 2020

Thanks everybody for the questions, comments, and suggestions!

The state of Spelling Reform

The six most promising schemes of reformed spelling, with summaries, can be found on the Society’s website (The English Spelling Society). The second (virtual) session of the International English Spelling Congress will probably take place in November. If you are interested in the fate of Spelling Reform, please register (it is free). The more people, native speakers and foreigners, scholars and students, sign up, the better. Make your voice heard, regardless of your views on the Reform! A major media event is being planned for late July or early August (you will find the information in the Society’s blog). It is crucial for the success of the Reform to present the case, without alienating the wider public. We, who think that English spelling is a handicap to literacy, rather than being a window to it, hope that the Reform will do away with at least part of the rubbish which forms a barrier to mastering English everywhere. The world gleefully calls English spelling the most absurd ever and beyond redemption. Absurd it is, but, in our opinion, not beyond redemption. Sign up, voice your support or objections, but don’t sit on the fence, which is a fence to literacy.

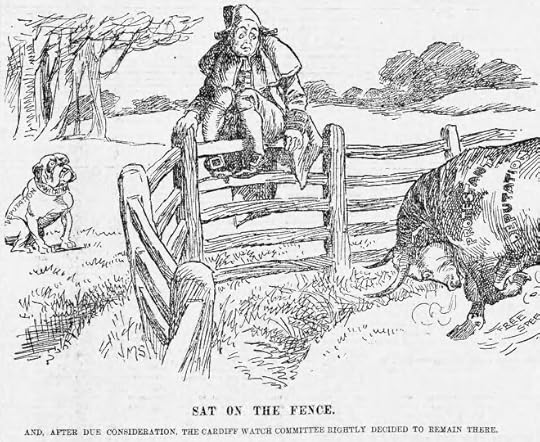

Don’t sit on the fence. Speak up! Political cartoon by JM Staniforth. 17 December 1898. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Don’t sit on the fence. Speak up! Political cartoon by JM Staniforth. 17 December 1898. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Hoity-toity, and all, all, all

A correspondent sent me a long list for words like hanky-panky, heebie-jeebies, and hoity-toity, and wondered why their first component so often begins with an h. Naturally, I don’t know why. If I say that h is the easiest sound to pronounce, almost a default consonant, a mere breath, my answer won’t go far, because I have no proof of my statement, except that when f, s, and any spirant begins to disappear in language, its last station is always h. Yet I can say that I know the problem and refer to it in Chapter Six (reduplicating compounds) of my book Word Origins. Not all reduplicating compounds share such a strong predilection for h: compare fuddy-duddy, razzle-dazzle, Polly-wolly-doodle, and many others. Nils Thun, a Swedish scholar, wrote a dissertation, titled Reduplicating Words in English: A Study of Formations of the Type tick-tick, hurly-burly, and shilly-shally (Uppsala, 1963). The word index to his book contains close to twenty-six pages; h-words take up four and a half of those twenty-six. No other letter is represented even approximately so well. The question about its popularity remains open, unless what I said above brings us an inch closer to the solution.

Razzle-dazzle. Image: The red flag in New York, Tuesday, January 13th / Matt Morgen(?). No known restrictions. Via the Library of Congress.

Razzle-dazzle. Image: The red flag in New York, Tuesday, January 13th / Matt Morgen(?). No known restrictions. Via the Library of Congress.Coincidences and borrowings

In one of the comments, our frequent correspondent pointed to Engl. much and Spanish mucho: they are almost homonyms and mean the same, but go back to different sources. Such cases are rather many, though textbooks like to repeat Antoine Meillet’s example of English and Persian bad (the same meaning). Such formations point to the danger of jumping to conclusions about the origin of homonyms across languages.

I have no chance of convincing my inveterate opponent that his idea of tracing English words to Neolithic Greek is a fallacy. Two weeks ago, I came up with an argument that might, I hoped, make him more cautious. The closer a Greek word is to an ancient English one, I wrote, the more obvious is the conclusion that such words are not related, because since the remotest epoch an English word would have undergone various phonetic changes that would have made the putative Greek etymon unrecognizable. I also wondered at the method of taking an arbitrary stub of a Greek word and declaring it to be the source of an English one.

Now we are told that the origin of Engl. dry goes back to the end of Greek án-uthros “waterless.” (I would have skipped this conjecture, but our correspondent rebuked me for ignoring it.) The borrowing of an unstressed syllable of a Greek word and using it as the source of Germanic draugaz is an idea that would have made even a seventeenth-century etymologist blush. Also, the entire idea is fanciful: how could anyone use the last syllable of a word for “water” to coin a word for “dry”? The syllable an- is a negative prefix. (Incidentally, another correspondent tried to produce dry from two Chinese words.) By way of postscript, I’ll answer one more query: Can dry be related to track? No. Though track is a word of Germanic origin, its sounds and those of dry do not match.

No one wants to be DRY. Public domain via Piqsels.

No one wants to be DRY. Public domain via Piqsels.This is the last time I am commenting on Neolithic Greek, but I would like to repeat that nothing at all is known about Neolithic Germanic, whatever the DNA of modern people may tell us about their genetic makeup. To justify the idea of borrowing from direct contact (as opposed to borrowing from books), it is necessary to know where and when the word could have been taken over from a foreign source. As a rule, only the names of unfamiliar objects and customs were borrowed by nomads and seminomads from their neighbors. Borrowing a common adjective needs special pleading. Herein, by the way, lies the danger of all references to undefined substrates.

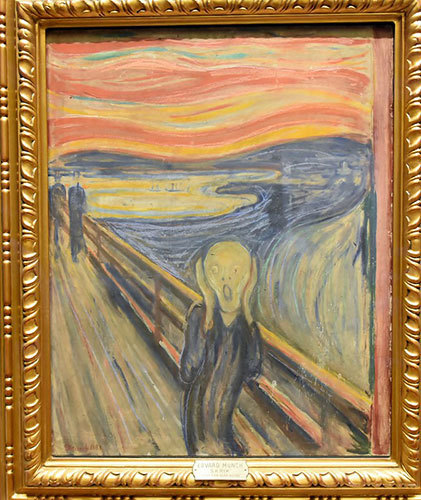

The most famous scr-word, as discussed in last week’s post. Photo by Richard Mortel of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The most famous scr-word, as discussed in last week’s post. Photo by Richard Mortel of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.More studies in advanced English

Our correspondent notes, with well-justified regret, the transformation of using into a preposition, as in: “But the new study offers a more compelling case because the researchers looked at more than 800 people USING a number of sophisticated new statistical tools.” (Of course: looked with new devices.)

He also observed that even educated people tend to produce pseudo-Latin endings in the plurals processes and especially biases. The result is process-ESE and bias-ESE (as in crises).

Jingling and splitting all the way. The ubiquitous trend, probably initiated by some semi-literate journalists, has spread not like wildfire but like a pernicious virus. Here are three examples from a major newspaper for the same day. “Classes that have always been delivered online will continue to not be counted toward the fee threshold.” Unnecessary and ugly. The old, most reasonable rule, as formulated by H. W. Fowler in Modern English Usage, is: “Split if you must and know how to do it.” “Advisers and attorneys will be allowed to fully participate in all sexual misconduct hearings.” Acceptable, though not necessary (to participate fully would have been at least as good). And a last example: “Betsy De Vos has said the new regulations aim to better balance the rights of alleged victims and the due process rights of the accused.” Here the split seems to be justified. All three sentences were written by the same man. He of course ALWAYS splits. But why treat one’s native language like a rag to be trampled with impunity?

Feature image credit: Two girls writing. Public domain via PickPik.

The post Etymology gleanings for July 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers