Oxford University Press's Blog, page 125

November 25, 2020

Bizarre the world over

The posts for the last two weeks dealt with the various attempts to trace (or rather guess) the origin of the word bizarre, and I finished by saying that the word is, in my opinion, sound-imitative. In connection with this statement a caveat is in order. Sound imitation (onomatopoeia) is fine when there is something to imitate. Meow, baa-baa, and moo are indeed sound-imitative, and so is buzz. But bizarre people don’t buzz. Whenever etymologists begin to speak about onomatopoeia, the ghost of sound symbolism raises its head: short i makes us think of small objects, gl– suggests glowing and glamor, sl- is all about slime and sleaze, and fl- about fluttering, flowing, flipping, and the rest. But, alas! i occurs not only in tit but also in big, while gl- is the initial cluster of glum and gloom, the least glamorous things imaginable; even glitter once meant “to shine brightly” (remember not all is gold that glitters?) and now it means “to shine faintly.”

Any reference to sound imitation and sound symbolism, outside the obvious and trivial, is doomed to remain a hypothesis, and yet both played and play a significant role in coining words. In most cases, their existence cannot be proved, especially because words belonging to this group tend to be nearly identical in unrelated languages and do not obey the phonetic laws of comparative linguistics. Those who believe that bizarre goes back to an unattested Gothic word or to some Latin noun will not change their opinion. Two outstanding Romance philologists who suggested that bizarre is sound-imitative offered no discussion. My aim is not to dissuade anyone; it is rather to produce a context for this hypothesis.

What Germanic adjectives, verbs, and nouns resemble bizarre? English busy perhaps. (See the post for May 3, 2006 about the odd spelling of this word.) We look it up in etymological dictionaries and find: “of unknown origin.” German böse “evil, wicked; angry” (also erbost “furious”) are close by. Where did they come from? So many words look like böse, and so many are the directions in which their meanings go that no clear conclusions can be drawn. This is the verdict in the latest edition of the most authoritative etymological dictionary of German (thus, again “unknown”). Böse has no obvious cognates, while English busy does. The Dutch for “busy” is bezig. Close to it are Dutch biestert, which at one time seems to have meant “running wildly, etc.,” verbazen “to amaze,” German dialectal baseln “run madly around,” and Swiss dialectal (German) bausen “to do useless work in the kitchen; rummage,” among quite a few others. Similar-sounding Germanic words seem to have reached the Romance territory, if Old Catalonian basarda “fear” (noun) belongs here. Perhaps the fifteenth-century French slang word basir “to kill” is also part of the “family.” In some way, they too refer to a hectic activity.

Hardly the inspiration for busy or even boast. (Image by Raymond)

Hardly the inspiration for busy or even boast. (Image by Raymond)As early as 1912, Wilhelm Braune, a famous German philologist of the past, cited numerous French words of this type and suggested their Germanic origin. He did not mention English busy, but Leo Spitzer, another distinguished scholar, in 1935 did cite busy in connection with two French verbs meaning “to stun, bewilder.” The problem with such passing mentions is that they are needles in a haystack, and it is no wonder that English etymologists did not notice Spitzer’s idea. Icelandic has bisa “to work hard; drag an object along.” It is a late word (no records before the seventeenth century), but Norwegian bisa, which means “to talk nonsense,” seems to be related. In this almost endless list bVs words (V = Vowel), we find such senses as “carouse” (hence English bouse ~ booze), “swell,” “twaddle,” “exert oneself,” “do harm,” “rush along,” and “puff up.”

This is what the wind bise (la bise) looks like in real life, rather than in etymology. (Image by Janusz Dominik)

This is what the wind bise (la bise) looks like in real life, rather than in etymology. (Image by Janusz Dominik)The puffing up, that is, swelling is said to underlie English boast. German Bise “the wind from the Northeast” and English beestings may or may not belong here. I’ll skip the bVs ~ bVz words for “kiss” and “female genitals” and the names Bisinus ~ Basina, known from medieval Germanic tales, because their meaning is unclear. But English busy, I believe, does belong to that club. Its etymology is “unknown,” because, strictly speaking, it has none: just an onomatopoeia, endowed with certain associations. The same should probably be said about German böse. Indeed, it is surrounded by such a motley crowd that a semantic nucleus cannot be found and should probably not be sought.

We have a buzzword, so to speak (sorry for the feeble pun), and its progeny is spread all over Germanic. Perhaps in the Middle Ages it reached the Romance-speaking world, but parallel development supplementing borrowing needn’t be ruled out. Words like English boast suggested to some students of Indo-European that such formations go back to the root bhou– (with a short or a long vowel) “to swell.” I am afraid that this ancient root is fiction. It is only a common part of several historically unrelated but semantically similar words. They are “related” (to use the metaphor I have often used before) like soldiers from the same regiment: all have the same uniform and may even perform the same duty; yet they are not brothers.

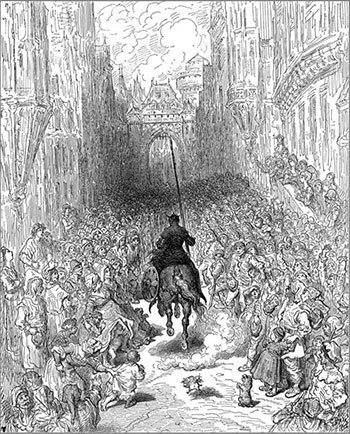

Bizzarro! (Image by Gustave Doré for Ludovico Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso”)

Bizzarro! (Image by Gustave Doré for Ludovico Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso”)My conclusion should by this be time be obvious. It seems that bizarre is one of many b-s ~ b-z words. A bizarre person might swell himself and be furious, valiant, and prone to heroic deeds. Or this person’s behavior might be odd; hence “peculiar, eccentric.” Not improbably, this adjective is of Germanic origin, but, as pointed out, while dealing with such formations, one never knows. Russian borrowed from Polish the word bzik “whim, caprice.” It earlier referred to the behavior of the cattle running away from hornets, horseflies, gadflies, and their likes. This is exactly what French dialectal beser and several German dialectal verbs (biesen ~ biessen and busseln) mean! I’ll leave it to specialists in Slavic and Romance to decide how this group of words originated. I’ll also leave Russian bystryi “quick, fast” to them. Allegedly, it is related to some of the Germanic words mentioned above. My task, as noted, was to provide a context for bizarre and, by the same token, for Italian bizza “whim.”

Only a short postscript is now in order. Friedrich Kluge (1884) traced busy to the root bhēs “active,” Francis Asbury Wood (1902) glossed it as “feverish,” and Victor V. Levitsky (2010) was, in principle, of the same opinion but considered the closeness of this root to the root bus “hot, proud, precipitous.” In French, as noted in the first part of this series, bizarre crossed the path of the equally enigmatic bigarré “motley.” Pierre Guiraud, the author of a provocative dictionary of words of unknown origin (Dictionnaire des étymologies obscures, 1982), reconstructed the root big– “bent, crooked” and combined bizarre and bigot. This solution strikes me as improbable. Other than that, to repeat: I doubt that we should look for some good ancient root. A common semantic denominator like “active, quick, feverish” seems to have existed. Many words had the structure bVz and resembled the onomatopoeic buzz, perhaps first only in Germanic. A picture of cows fleeing wildly from pestiferous insects should inspire us in a search for the etymology of bizarre and its kin.

The post Bizarre the world over appeared first on OUPblog.

November 24, 2020

The Jeremiah Barker Papers: medicine as practiced 200 years ago

This is the story of a lost manuscript, an unpublished book written 200 years ago by a rural physician in New England—not one of the elites, but a preceptor-trained doctor who spent his long life taking care of people and writing about it. He is unique because of his fierce determination to keep up with the medical literature and communicate with both peers and patients. We don’t know why his book was never quite finished and published, but its discovery provides an important new primary source for medical history, research, and teaching, and will be of interest to an array of students and teachers, genealogists, physicians, and general readers.

Jeremiah Barker’s house. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)

Jeremiah Barker’s house. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)Barker’s book was thought to have been “lost” by James Spalding, an early 20th Century medical historian in Maine, but in fact it was given to the Maine Historical Society by his descendants in the 1940s and called to my attention in 1990. The Jeremiah Barker Papers, held in the Maine Historical Society Library in Portland, consist of two manuscript boxes of letters, casebooks, texts with Barker’s marginalia, as well as his unpublished manuscript. It is a fifty-year record of his reflections on disease, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome, revealing his unusual effort to consult and cite the medical literature and other physicians in a changing medical landscape, just as practice and authority began the gradual shift from historical to scientific methods. I was excited to find it and delighted to get permission to work on it and publish it.

An excerpt from an 1806 letter illustrates Barker’s writing style as well as his concern about disease, diet, and alcohol abuse:

“I had opportunities of observing the habits, customs, and manner of living among the first settlers… In many towns I noted these things, always carrying pen, ink, and paper… The first white inhabitants of Maine… lived for a time, in a very similar manner as the Indians did. Their exercise was great, their food simple and wholesome, consisting chiefly of Indian Corn and salted pork, sometimes Bear. Rum could be procured only in small quantities; and happy would it have been for them and their posterity had this continued to be the case… Rum [today] is conveyed into the country towns, as it were, through aqueducts; but none is lost for want of throats.”

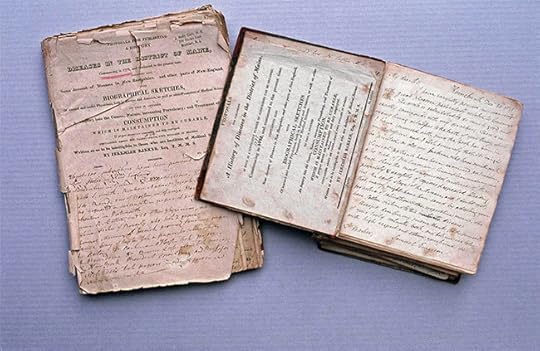

A synopsis of a book from Jeremiah Barker’s library. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)

A synopsis of a book from Jeremiah Barker’s library. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)Barker’s practice covered many aspects of disease, from insanity to infection, consumption to chemistry, bleeding to childbed fever, and tradition to innovation. His patient narratives include this case of consumption:

“Soon after, a lady, in the bloom of life, rode ten miles in a chaise, covered with a muslin gown, in a damp evening air. The next morning, she awoke with hoarseness; and pulmonary consumption ensued, which terminated life in a few months. A physician, ironically, called this a muslin consumption.”

Here Barker is trying to make the case for preventive medicine with regard to women’s clothing, particularly in Northern New England. The French also thought that women’s clothing caused an increase in consumption, but they focused on fashionable styles and stays rather than whether women were warm and dry.

Barker experimented with the new chemistry of Lavoisier, going out on a limb to use alkaline therapies. He communicated with Boston’s George Parkman about treating the insane. He wrote to Hall Jackson about foxglove (“William Withering’s Wonderful Weed”) to treat dropsy, neither of them realizing that they were actually treating heart disease or why the treatment worked. Interestingly, he practiced at the same time as, and only 60 miles away from, the midwife Martha Ballard, who is familiar to us in Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A Midwife’s Tale. Unlike many physicians at the time, he did not disparage lay healers such as Ballard. However, he did express his disdain for certain other “sectarian” physicians that he considered bogus.

The Barker manuscript includes a subscription paper with the names of other physicians who promised in advance to buy a certain number of copies of the book when it was published. It tells us that the book would include biographical sketches of learned physicians, that it would inquire into the causes, nature, and prevalency of consumption, which Barker maintained was curable (in spite of having lost three wives to it), and that it was “written so as to be intelligible to those who are destitute of Medical Science.” It would be sold for two dollars in boards, which is about $43 today, a price comparable to that of other medical books at the time.

Jeremiah Barker Papers manuscript volumes one and two. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)

Jeremiah Barker Papers manuscript volumes one and two. (Image courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.)Why bother with medical history? The history of medicine provides us with a measure of humility, helps us avoid temporal superiority and dogmatism, and gives us an appropriate skepticism. It teaches us which methods have been useful in the past and which have led us astray, even those of the best minds of the period, promoting intellectual modesty and tolerance that serve us well. Thus we may conclude that a better understanding of medical history can help offer healthcare providers and the public “perspective, [and] humility, where overconfidence frequently exists, as well as openness to change,” remembering George Santayana’s words: “Skepticism is the chastity of the intellect, and it is shameful to surrender it too soon or to the first comer.”

We must face uncertainty today, as did clinicians 200 years ago. Like them, we practice in a developing tradition and must deal with change and error as we care for our patients. Caring, curiosity, and love of learning are crucial to the makeup of a good clinician. It’s not just a job.

Featured image: Collection 13, the Jeremiah Barker Papers at the Maine Historical Society. Courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.

The post The Jeremiah Barker Papers: medicine as practiced 200 years ago appeared first on OUPblog.

November 23, 2020

Lost for words? Introducing Oxford’s “Words of an Unprecedented Year”

Bushfires. A global pandemic. Lockdown. Economic recession. Racial injustice. International protests. A pivotal election. For over a decade, we have selected a word or expression that captures the ethos, mood or preoccupations of the last 12 months, driven by data showing the ways in which words have been used. But this year, how could we pick a word, or even a shortlist, to summarize the ways in which we’ve been continually knocked off our axis?

Instead, today we released a comprehensive report entitled “Words of an Unprecedented Year” which tracks some of the new words and most significant language trends to have emerged across a truly unique year. The report shows how “Covid-19” spread across the world, not just epidemiologically but through our language, becoming one of the most used nouns of the year, despite only being coined in February. It maps how we went into ”lockdown” in some countries and were asked to “shelter-in-place” in others, while “circuit breakers” made their way from Singapore to Western Europe. It marks the moment in which the term “Black Lives Matter” surged back into our collective consciousness and “Karens” made a name for themselves, while the use of “systemic racism” increased by 1,623%, compared to last year. And, as the year ground on, our conversations shifted to the political, with words such a “mail-in” increasing by 3000% during the run-up to and uncertainty of the US election.

The report makes for fascinating reading, but how do we go about selecting these words? Like all of our lexical efforts, the process is driven by data. We observe how people wield their words, how they flex them and merge them, how they pick them up and drop them again, and we record all of this objectively. We analyse huge corpus databases to understand how words are being used, when new words are being born, and when others are slipping out of popular use. This data captures real word uses of English around the world, whether in North America or the Caribbean, East or West Africa, Southeast Asia, or Australia, and helps our expert lexicographers to identify trends. We then examine these trends to identify which words truly encapsulate the events of the year.

To be considered for Word of the Year, we’re looking for words where the evidence shows it has emerged, changed, or grown in a significant way in this year in particular, and which captures a certain collective feeling about the time we’ve just experienced. For example, in 2016, when “post-truth” was named Word of the Year, we’d lived through a year in which fake news was hitting the headlines, quite literally, and public trust in institutions was plummeting. It’s always difficult to whittle down a shortlist of words that capture the breadth of events that take place within any given year. This year, our data showed us that the way we use certain words and the new words that emerged were so radically different and prolific that we have a much more detailed story to share.

And that story paints a picture: Imagine a historian in 50 years’ time—to understand what 2020 was about they would need to look no further than our language. They would see “coronavirus” replace “time” as the most commonly used noun in the English language, they would see “social distancing” become the norm, and the hope of “re-opening.” They’d see the growth of “cancel culture,” the political tension surrounding elections the world over, and thoughts turn to environmental sustainability and the future as we turn our attention to rebuilding. By releasing this longer form piece of language research, I’m hopeful that we can bring a greater understanding of both the language and our global experience to this unprecedented year.

If you’d like to know more, I invite you to join me and my colleagues, Fiona McPherson and Kate Wild, for a webinar on 10 December where we’ll give an overview of our corpus analysis-based approach to monitoring language, and this year’s particular challenges of keeping track of rapid language developments.

The post Lost for words? Introducing Oxford’s “Words of an Unprecedented Year” appeared first on OUPblog.

November 22, 2020

Capturing your “rude” conqueror

Roman civilization is one of the foundation stones of our own western culture, and we are often exposed in newspaper and magazine articles, books, and even TV documentaries to the glories of Roman art, architecture, literature (the chances are you’ve read Virgil’s Aeneid), rhetoric (we’ve all heard of Cicero), even philosophy. Yet in the late first century BC the Roman poet Horace wrote: “Captive Greece captured her rude conqueror and introduced her arts to the crude Latin lands” (Epistle 2.1.156). Did he really mean that Rome owed its cultural and intellectual heritage to the Greeks?

The answer is yes, as I discuss in my Athens after Empire. The Romans did have their own culture, but largely derived from the peoples they defeated (such as the Etruscans) as they expanded in Italy and the contacts they had with the Greek cities of southern Italy (so many that the area was nicknamed Magna Graceia) and Sicily. Once they became involved in mainland Greece in the second century BC their eyes were really opened to Greek, especially Athenian, civilization.

A turning point came in 155 when the Athenians sent a delegation to Rome to protest a fine. Instead of diplomats the people sent the heads of the three main philosophical schools. Although it had limited success, the philosophers all gave talks about their different philosophical systems; from then on the Romans were bewitched by the “allure” of Hellenism, and the Athenians cannily began to promote their culture and learning, especially in two areas that most captivated the Romans: philosophy and rhetoric.

In the first century prominent Romans and their sons went to visit and study in Athens, with the city being seen as a finishing school of sorts. Cicero visited the city twice; Titus Pomponius, better known as Cicero’s famous friend and correspondent Atticus, moved there and joined the Epicurean school; the poets Horace and Ovid praised their time in Athens; also attending philosophers’ classes and staying in the city were Brutus (after Caesar’s assassination) and Mark Antony; and the emperor Augustus and his successors went even further by consciously appropriating aspects of Hellenism that appealed to them (such as architecture or oratory) for Roman cultural and political ends.

When we turn to works of Roman literature their Greek predecessors, so to speak, burst forth all the more. Take Virgil’s Aeneid (recounting Aeneas’ wanderings after the fall of Troy to Italy and the eventual foundation of Rome). Virgil was so influenced by the Homeric poems that his is a hybrid of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Of the Aeneid’s twelve books, the first six (Aeneas’ travels to Italy) mirror the Odyssey (Odysseus’ wanderings) and the second six (the struggles of the Trojans) mirror the Iliad (the last year of the Trojan War).

The Romans’ expansion in the eastern Mediterranean tends to focus on how they did it—the campaigns, the battles, the treaties, the diplomacy, the looting, the impact on the vanquished. Yet often overlooked is the impact of the conquered, in this case the Greeks, on the conquerors. I address this aspect in my book, introducing a new dynamic between Rome and Greece, especially Athens, in Rome’s climb to dominance in the east. Athens in the Hellenistic and Roman periods is often seen as a shadow of its Classical predecessor, politically, militarily, socially, and culturally. It lived under Macedonian hegemony thanks to Philip II and his son Alexander the Great until Rome imposed its mastery over Greece.

I show in my book that nothing could be further from the truth: the city in this later period is still a vibrant one, the people always ready to resist foreign domination when they could, no matter the odds, and with a lively cultural, religious, and intellectual life. It was that culture and history that seduced the Romans in a way they could never have imagined until confronted by three philosophers in their city one day.

Rome may have conquered the lands and imposed its rule, but as Horace knowingly points out, it was the Greeks who ended up capturing and imposing their culture on Rome. That Rome acknowledged this may be seen in AD 132, when the emperor Hadrian founded a new league of cities in the east and he needed at its center a city that was steeped in history, tradition, and culture. For him, there was only one: Athens.

And so the city enjoyed a renaissance and a new life in the Greek world, a fitting end to its fall centuries earlier to Macedonia and then to Rome, and a tribute to its status as a cultural and intellectual juggernaut through the ages.

The post Capturing your “rude” conqueror appeared first on OUPblog.

November 21, 2020

When female peacekeepers’ “added value” becomes an “added burden”

Calls for the increased participation of uniformed United Nations female peacekeepers have multiplied in recent years, fueled in part by new scandals of peacekeepers’ sexual abuse and exploitation (SEA), tarnishing the UN’s reputation, and in part by the will to show explicit progress at the 20th anniversary of the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security. Linked to these calls, numerous UN reports and policy documents have emphasised the “added value” that female peacekeepers can bring, explaining how their increased participation can render peace operations more effective and efficient. As these arguments about women’s “added value” as peacekeepers are mostly promoted by organisations that strive to foreground women’s rights, we can assume that they are made with the hope that this will increase gender equality.

However, there is a need to acknowledge that this is a one-sided debate which only focuses on women and does not question male peacekeepers’ performance. There is thus a clear risk of contributing to gender inequality and a backlash against women’s participation in peace operations if female peacekeepers’ contribution continues to be instrumentalized. This is because the discussion about female peacekeepers’ “added value” is both unrealistic and unfair. It is unrealistic because the expectations generated by the “added value” discussion are based on research conducted on only 4% of all peacekeepers, making it difficult to generalize from the findings. It is unfair as the “added value” risks becoming an “added burden” which only is carried by the female peacekeepers, not their male homologues, who so far have escaped demands about any “added value.” This, in spite of the fact that they constitute the large majority of military peacekeepers.

Many female peacekeepers internalize these expectations of “making a difference” as women in a male-dominated environment and try to fit into gender-related expectations and/or work harder than their male colleagues, thereby producing self-fulfilling prophecies. Research has for example shown how female peacekeepers often have worked a “second shift,” either before deployment, by trying to get additional training in areas where women are assumed to perform better than their male colleagues, or during the deployment, by using their free time to volunteer in tasks where they are supposed to make a difference as female peacekeepers. Examples include Rwandan female peacekeepers organizing nightly tutorials after pre-deployment classes on how to talk to Sexual and Gender-based Violence (SGBV) victims and Indian female peacekeepers volunteering to engage with local communities, offering free health care services for pregnant women, and first aid courses to schoolgirls after their regular working hours. The fact that over 75% of troop contributions come from Africa and Asia, with African states contributing close to 50% of all peacekeepers, means that this “added burden” falls disproportionately on female peacekeepers from the Global South countries.

In addition to undermining gender equality by putting extra expectations on female peacekeepers to perform “better” than their male counterparts, the “added value” argument also risks reinforcing gender stereotypes for both men and women, and may narrow down the spectrum of tasks that women and men can do in peace operations, leaving the “warrior tasks” to the male peacekeepers and “diplomacy tasks” to the females. Such a division is not only based on shaky evidence, and may undermine women’s integration into infantry units where these characteristics are not valued, but it also misses the point of peacekeepers serving as role models that can break gender stereotypes that are detrimental to gender equality.

How do we then get around this minefield of gender dilemmas and avoid instrumentalizing women’s performances in the military? How can we merge normative agendas of increasing women’s participation as soldiers and peacekeepers without pushing them to live up to unrealistic demands and contradictory gender stereotypes?

Turning the table around and focusing on making the military environment a more inclusive workplace could make both the military in general, and peace operations in particular, more effective, while simultaneously facilitating recruitment of underrepresented groups. Such a transformation of the environment is not only to the benefit of female soldiers, but moreover to the organisation as a whole, as research has long proven that diversity is an asset. Yet, such a makeover of a traditionally conservative domain needs representative leaders who are able and willing to drive and push for change. Instead of concentrating on what “added value” that female peacekeepers could, or should, bring, the focus ought to be on how to recruit male and female military leaders who show empathy, inspire, and encourage excellence while valuing diversity and inclusion.

Featured image by Miguel Á. Padriñán

The post When female peacekeepers’ “added value” becomes an “added burden” appeared first on OUPblog.

November 20, 2020

Accessible libraries: “a different sense of reading”

The German Centre for Accessible Reading, dzb lesen, unites tradition with the modern world. Founded on 12 November 1894 as the German Central Library for the Blind, it has been a library for blind and visually impaired people for more than 125 years and is thus the oldest specialist library of its kind in Germany. Over the years, the non-profit institution has constantly faced new challenges. Changes in the German copyright law in January 2019 made it possible to reposition and rename the institution in November 2019. We now offer accessible literature for loan or purchase for many different user groups, and, following our motto “a different sense of reading,” are developing new resources for people with dyslexia and people with physical disabilities who are unable to handle books. At dzb lesen, we use our expertise to offer advice and services that make reading accessible and promote inclusion.

Our goals In a nutshell, our vision is: we make reading possible. In order to bring our main principle to life, we work with accessibility always on our mind. Thus, dzb lesen enables numerous ways to access literature and information and tailors its activities to the individual interests and needs of its blind, visually impaired, and print-disabled users—anyone who cannot read the usual print. To fulfill our task, we collaborate in national and international networks and exchange experiences.

In a nutshell, our vision is: we make reading possible. In order to bring our main principle to life, we work with accessibility always on our mind. Thus, dzb lesen enables numerous ways to access literature and information and tailors its activities to the individual interests and needs of its blind, visually impaired, and print-disabled users—anyone who cannot read the usual print. To fulfill our task, we collaborate in national and international networks and exchange experiences.

Among our goals for the foreseeable future are offering large print for visually impaired and print-disabled people, further developing our dzb lesen app (App Store, Google Play)—such as enabling voice commands, which would be useful for people with physical disabilities—and developing accessible e-books, which support, among others, people with dyslexia.

We know that in spite of our efforts and those of similar institutions, there is a great lack of accessible literature. We aim at changing this situation in cooperation with editors and publishers—that’s the only way. An important concept for us is “Born Accessible Content,” inclusive publishing right from the source. The process has started but there still is a lack of basic understanding and necessary skills, which is why we make many training offers to publishers and libraries alike.

We know that in spite of our efforts and those of similar institutions, there is a great lack of accessible literature. We aim at changing this situation in cooperation with editors and publishers—that’s the only way. An important concept for us is “Born Accessible Content,” inclusive publishing right from the source. The process has started but there still is a lack of basic understanding and necessary skills, which is why we make many training offers to publishers and libraries alike.

The centre is not only a library but is first and foremost a production centre for Braille and audio media, large print, tactile media—and soon even more. Special offers are created for the special reading needs of blind, visually impaired, and print-disabled people.

The centre is not only a library but is first and foremost a production centre for Braille and audio media, large print, tactile media—and soon even more. Special offers are created for the special reading needs of blind, visually impaired, and print-disabled people.

To make print media accessible, the centre needs to adapt them: texts are transcribed into Braille or edited in large print, music scores are transcribed into Braille music, pictures are converted into touch images, and audio books are narrated. To do this, the centre has its own recording studio, printers, and bindery.

No matter if you prefer crime novels or non-fiction, light or classic novels, we’ve got books of all genres for your “aha!” moments, thrill, and enjoyable reading. Our free library offers approximately 75,000 different titles to eligible users. In addition, dzb lesen offers subscriptions for magazines and many products on sale. We also produce media on request from our readers and to order.

In general, fiction titles are on top of our lending numbers. Together with Braille literature, our audio books in the Digital Accessible Information System (DAISY) format are by far most popular. And our relief products, such as tactile children’s books or tactile maps, are definitely something special. Our collection of Braille music scores for blind professional and non-professional musicians is unique in Germany.

In general, fiction titles are on top of our lending numbers. Together with Braille literature, our audio books in the Digital Accessible Information System (DAISY) format are by far most popular. And our relief products, such as tactile children’s books or tactile maps, are definitely something special. Our collection of Braille music scores for blind professional and non-professional musicians is unique in Germany.

The fundamental difference between dzb lesen and other libraries—e.g. the public library in your residential area—is that we have no reading room, we have no reference library, hardly any visitors, and no usage fee. Our library operates via mail. Users request books, often by phoning our librarians, and get them sent home. Braille books, for example, are sent in a large kind of briefcase free of charge as a cecogram. Every day we send lots and lots of audio books by mail. Our “reading room” is all the German-speaking countries, and, even beyond them, we send our books to any place where our users read German—even to Canada and Australia. Many audio book fans also use our free dzb lesen app (App Store, Google Play) for streaming and downloading. We want to extend that service.

The fundamental difference between dzb lesen and other libraries—e.g. the public library in your residential area—is that we have no reading room, we have no reference library, hardly any visitors, and no usage fee. Our library operates via mail. Users request books, often by phoning our librarians, and get them sent home. Braille books, for example, are sent in a large kind of briefcase free of charge as a cecogram. Every day we send lots and lots of audio books by mail. Our “reading room” is all the German-speaking countries, and, even beyond them, we send our books to any place where our users read German—even to Canada and Australia. Many audio book fans also use our free dzb lesen app (App Store, Google Play) for streaming and downloading. We want to extend that service.

As a library, we work in the field of reading promotion, mainly together with schools for blind and visually impaired children and similar institutions. We’re also connected with public libraries via our initiative “Chance Inclusion.” We train their librarians and facilitate making our accessible literature available to public libraries. That way, elderly people can remain users of their home library, even if they lose sight and have difficulties reading. Our 50,000 audio books are an attractive offer for them.

As a library, we work in the field of reading promotion, mainly together with schools for blind and visually impaired children and similar institutions. We’re also connected with public libraries via our initiative “Chance Inclusion.” We train their librarians and facilitate making our accessible literature available to public libraries. That way, elderly people can remain users of their home library, even if they lose sight and have difficulties reading. Our 50,000 audio books are an attractive offer for them.

Each year we host numerous public events, including readings and lectures, guided tours for children and adults, the night of museums, and our regular open day. We participate in different trade fairs and expert forums, we teach at Leipzig University and Leipzig University of Applied Sciences (HTWK Leipzig), we cooperate with public radio and TV stations to create accessible offers, plus a lot more. All of this makes our centre, our library, special.

Photos courtesy of dzb lesen. Used with permission.

The post Accessible libraries: “a different sense of reading” appeared first on OUPblog.

November 19, 2020

The case for investing in wind energy

If you spend time driving on the interstate highway system in the US, you may be surprised, as I have been, to see the rapid development of wind energy. This is especially true in the Great Plains where there is a seemingly endless array of wind turbines decorating the horizon. And, north of Los Angeles, the Tehachapi Mountain Range is home to almost 5,000 wind turbines.

If you were born before 1989, you lived in a US where there was no electricity generated from wind. However, in 2018 wind-generated electricity was almost the same as hydroelectric: 278 TWh (terawatt-hours) from wind versus 289 TWh from hydroelectric. Wind made up 6.2% of the total US electricity generation, a remarkable increase from 20 years earlier in 1998 when it was less than 0.1%. And fourteen states now generate more than 10% of their electricity from wind with three, Iowa, Kansas, and Oklahoma, generating more than 30%. Likewise, the world did not see any electricity generation from wind until 1985 but in 2018 it made up almost 5% of worldwide generation, a significant growth from 20 years earlier in 1998 when it was only 0.1%. Large wind turbines, intended for utility-scale electricity generation, now number more than 400,000 turbines worldwide but, if we include small-scale turbines, the number is greater than one million. Like solar panels, these small wind turbines can be used to reduce your residential electric bill, charge batteries for various applications, pump and purify water, and grind grain.

There is also great potential for further development of more wind energy. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates that US could add 11,000 GW (gigawatt) onshore capacity on 846,000 square miles of land in the US, where their estimate eliminates land unlikely to be developed, such as urban areas, federally protected lands, and recreational water reservoirs. And while this area represents an impressive 22% of the total US land area, this is deceiving since a wind farm directly impacts only 2% of the total land area, as farming and ranching can coexist with the wind farm. So, while wind turbines need to be sufficiently spaced to avoid wind interference, something known in sailing as “dirty wind,” the land area needed to place the turbine, permanent roads for maintenance, and transmission equipment is only 2% of the total wind farm. The US also has an offshore potential estimated at around 4,200 GW. The 15,200 GW obtained by combining these two would generate more than 45,000 TWh, assuming the plants operate at a capacity factor of 34%. To put this number in perspective, the total installed US capacity for electrical generation from all sources was 1,200 GW in 2017 and net generation was 4,000 TWh.

The capacity factor is defined as the actual electrical output versus rated design. In the case of a nonrenewable electrical plant, such as nuclear or natural gas, capacity factors less than 100% occur due to equipment failure, routine maintenance, or plant turndown because electricity is not needed or the price is too low. These types of plants typically have high capacity factors, ranging from 80- 90%. For a renewable energy such as wind, the capacity factor is much less than 100%, typically 30-40%, primarily due to the variation in energy input.

Like the US, there is also great worldwide potential which is, by one estimate, 94,500 GW. Applying the same 34% capacity factor used earlier, the generation would be about 280,000 TWh. Total worldwide electricity generation in 2017 was 25,600 terawatt-hours, so full utilization of the worldwide wind energy potential would make enough electricity to meet eleven times the needs of the world. Naturally, there are many hurdles to jump over to make this happen, including economical, geographical, technical, environmental, and improvements to the electrical grid, just to name a few, but it does show the awesome potential for wind-generated electricity.

In the US, the best place for land-based turbines is the western and central Great Plains, where wind speeds are typically 15-20 mph. This should be no surprise to anyone that has driven through the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles and western Kansas. And greater wind speeds result in greater utilization of the design power. It turns out that wind power increases with the cube of wind speed, so doubling the wind speed increases power by a factor of eight.

Capacity factor is a very important part of the economic viability, sometimes quantified as the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE). LCOE is defined as the break-even cost of electricity, taking into account the discount rate to borrow money, the capital cost, the plant life and depreciation, operating costs, fuel costs, capacity factor, and taxes. An average LCOE in the US for a natural gas electric plant is ₵7.6/kWh versus ₵10/kWh for onshore wind. There are, however, regional differences and if we place that wind farm in the Great Plains “wind belt,” the LCOE ranges from ₵2 to ₵6/kWh, making it as good, or perhaps better, than a natural gas plant. Another factor making wind energy more attractive is that capital costs are still decreasing. In 2015, the capital cost for an onshore wind farm was about $2,200/kW, decreasing to $1,600/kW in 2019, a reduction of 27%. Still another factor is turbine height. Formerly, turbine heights were on the order of 80 m, with power ratings of 1.5-2.0 MW. Some of the newer wind turbines, however, are 100 to 140 m tall, up to 1 ½ times the height of the Statue of Liberty! These turbines have power ratings of 3.0-6.0 MW, because wind velocity increases with height, turbine blades can be longer, and there are fewer obstructions.

A key to the future for wind energy is the development of utility-scale batteries and improvements to the electric grid. Since wind is by its very nature a variable energy type, batteries provide a means to deliver stable electricity output, such that excess generation can be stored for low output periods when the wind is not blowing. Access to high-voltage transmission lines is also critical. Whereas fossil-fuel plants can be built close to existing transmission lines, a renewable energy such as wind will be built in the windiest location, a location that may not be near high-voltage transmission lines. Therefore, new transmission lines will be needed to fully realize the US and worldwide potential for wind energy.

In summary, electricity generation from wind has been growing rapidly in both the US and worldwide. And there is a potential for much more growth, especially since wind farms only directly impact 2% of the total land area used, allowing wind farms to coexist with farming and ranching. A key to future development will be the addition of new transmission lines to the electric grid as well as batteries to provide storage since wind energy is, by its very nature, a variable energy source.

Featured image by Pexels

The post The case for investing in wind energy appeared first on OUPblog.

November 18, 2020

Bizarre is who bizarre does: part two

This post continues the discussion of bizarre (see the previous one for 11 November 2020). After the Basque etymology of this Romance adjective was rejected on chronological grounds, bizarre joined the sad crowd of “words of unknown (disputable, uncertain, undiscovered) origin.” However, several good scholars have tried to penetrate the darkness surrounding it. Each offered his own solution, a situation, as we will see, that does not bode well.

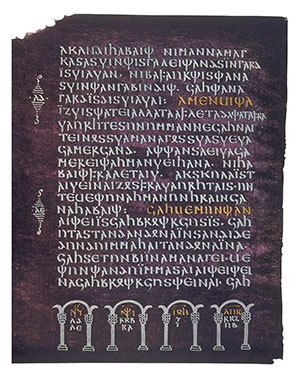

A page of the Gothic Bible. (Image by Asta)

A page of the Gothic Bible. (Image by Asta)Obviously, if a word appears from nowhere and has no ascertainable native roots, it may be a borrowing. And here I must turn to the language of the Goths, which I mention with great regularity in this blog, because Gothic is the oldest Germanic language that has come down to us (if we disregard runic inscriptions from medieval Scandinavia): significant parts of the New Testament, translated by Bishop Wulfila in the fourth century from Greek into Gothic, are extant. Two Gothic kingdoms flourished in the past: one in Italy (with its capital in Ravenna, where tourists can still see Ostrogoth King Theodoric’s Mausoleum) and one in Spain, with the capital in Tolosa. The eastern kingdom existed only from 453 to 555, but this period was the time of the efflorescence of Gothic culture, its Golden Age. The Visigoth kingdom had a much longer span of life: from the early fifth century to 711, when it was destroyed by the Arabs. As could be expected, Modern Italian and Modern Spanish have preserved relics of many Gothic words, some of which did not turn up in Wulfila’s translation. Such words were reconstructed from the dialects spoken today: thoroughly assimilated inserts of Old Germanic in the speech of modern people. Hence the idea that bizarre may be one of such relics, a continuation of an old borrowing from Gothic.

Theodoric’s Mausoleum in Ravenna. (Image by Roger W)

Theodoric’s Mausoleum in Ravenna. (Image by Roger W)In the previous post, I gave the chronology of the earliest known attestations of bizarre in the Romance languages. The first of them goes back to Dante’s Divina Commedia, that is, to the time many centuries after the disappearance of the Goths from the stage of history. This fact does not invalidate the Gothic hypothesis (let us call it this), because Italian bizzaro may have been a conversational word, even slang, or perhaps for a long time it remained current in a small area, in only one dialect. From the texts in Old High German we know the verb bāgen or bâgen: “to fight; quarrel” (both symbols—ā and â—designate vowel length), while the Norwegian adjective båg still means “resistant, unwilling, etc.” The idea that bizarre is a relic of Old Germanic occurred to the founders of Romance historical linguistics, but to trace the way from an unattested Gothic word to the Romance form, one must posit several unlikely phonetic changes. As far as I can judge, though the most recent author of the reconstruction mentioned above was a distinguished scholar, his etymology of bizarre is too complicated and unlikely.

Another attempt to penetrate the past of bizarre takes us to Latin vitiosus, which meant “vile, depraved” but occasionally had the connotations “artful; attractive.” This approach also looks like a blind alley. Vitium, vitiosus, and vitiare referred to vice and damage, rather than to fervor and eccentricity, and it would be a minor miracle if all the recorded senses of the Romance adjective were secondary and late. The phonetic hurdles one must overcome in moving from vitiosus to bizarre are perhaps not fatal to the reconstruction, but one of them is more serious than it may seem: vitiosus begins with v-, not with b-. No doubt, initial v- and b- alternate in many languages (compare Basil and Russian Va(s)sily, as in Vassily Kandinsky, among others). A reader, while commenting on my old discussion of bigot (see the reference to it in the previous post), pointed to the frequency of the interplay of b- ~ v-, which also occurs in some Romance dialects. But, as has been noted in a severe critique of the derivation of bizarre from vitium, bizarre has never been attested with initial v-. This, I think, is a serious objection. Reference to a certain even well-attested phonetic change does not suffice, because one expects the word under discussion to show traces of succumbing to it.

Kandinsky, un centro, 1924. To celebrate the alternation v ~ b. (Image by Sailko)

Kandinsky, un centro, 1924. To celebrate the alternation v ~ b. (Image by Sailko)Let it be remembered: both hypotheses have been offered by outstanding specialists in the history of the Romance languages. Yet they probably deserve the same unkind verdict as the fanciful oldest conjectures I mentioned in passing a week ago. All this goes a long way toward showing that etymology is a minefield and that sometimes the best experts fail to detonate the mines visible to outsiders, or, if you like it, that the path of true love never runs smooth.

Here is now a last attempt to trace bizarre to a “respectable” Romance root. Latin invidia means “envy, jealousy, ill will.” Allegedly, it changed to imbidia (again v- to b– but here through assimilation after m), with in– being understood as a prefix or a preposition. So did in-vidia ~ im-bidia allegedly become bizarre (the troublesome suffix –arre will remain a problem in any reconstruction). This is an old etymology, rejected by two great Romance scholars and resurrected about fifty years ago. I don’t think it has gained recognition in the meantime, but scholarly problems are not solved by voting, and it does not matter how many people agree or disagree with a certain hypothesis. The whole world may believe that the earth does not revolve—Eppur si muove, even though Galileo Galilei, most probably, never pronounced those famous, potentially suicidal, words. (In connection with such apocryphal phrases I may mention the 2006 OUP slim volume What They Didn’t Say: A Book of Misquotations, edited by Elizabeth Knowles: more examples of the same type, including “Elementary, my dear Watson.”)

The derivation of bizarre from invidia, though ingenious, is not particularly attractive. However, it has one redeeming quality: next to bizzaro, we find Italian bizza “whim, caprice; freak; outburst of anger.” As if to mock us, the origin of bizza is also unknown, but it would be a minor miracle if the two words were not in some way related, and the linguists who traced bizarre to invidia assumed that bizarre and bizza (both are pronounced with voiced zz, as in English adze) belong together.

I have left the least exciting but perhaps the most controversial etymology of bizarre undiscussed. According to it, bizarre (and bizza) are sound-imitative (onomatopoeic) words. It is my conviction that this etymology has potential, and I will devote the next (last) post on the history of bizarre to the facts bearing on the subject. We’ll have to travel rather far afield.

Feature image: Pxfuel

The post Bizarre is who bizarre does: part two appeared first on OUPblog.

November 17, 2020

Down but never out

The Athenians were in a panic in 490 (all dates BC). A Persian army had landed at Marathon, on the coastline east of Athens, intent on capturing the city and even conquering all Greece. The Athenians sent for help to other Greek cities, but only Plataea (in Boeotia) responded. Thus, a predominantly Athenian army faced the enemy—and won. The famous battle of Marathon was Athens’ coming of age as a military power; a decade later its navy helped to block another Persian invasion (led by Xerxes), a stepping-stone to Athens’ rise as a wealthy imperial power.

Then came its downfall. In the Peloponnesian War (431-404) Athens was defeated by Sparta; its navy practically annihilated, its league of allies disbanded, its economy wrecked and enduring a Spartan-backed oligarchy. One year later the Athenians restored their democracy; a little over two decades later they formed a new league, which became another empire, and their city was again dominant in Greece.

Then came another downfall. By the 350s Macedonia, under its dynamic king Philip II, had extended its influence in all directions until, in 338, Philip’s army faced a coalition Greek army headed by Athens and Thebes at Chaeronea (in Boeotia), fighting for Greek freedom. Philip won, with Greece falling under Macedonian hegemony. While there was no interference in Athens’ constitution, its league was dissolved, and it was again in financial ruin.

One—perhaps the—common thread in Athens’ history in this Classical period is the people’s resilience. When faced with many adversities, the Athenians never gave up hope and fought for their cherished democracy and freedom. Under Philip and his son Alexander the Great, they remained cowed, and in the following two centuries of Macedonian rule Athens was a very different place. It suffered a decline in military and naval power, faced considerable economic distress, suffered a property requirement for citizenship, which saw the expulsion of thousands of citizens, and endured periods of autocratic rule and even Macedonian garrisons in the port of Piraeus and on the Museum Hill, within eyesight of the Acropolis.

Nothing much seemed to change in the middle of the second century when Macedonia fell to Rome, and the latter annexed Greece and Macedonia into its empire. Now subject to Rome’s will, the Athenians saw their city increasingly “Romanized” with new buildings under Caesar, Augustus, and (in the first century AD) Hadrian, the appropriation of much of their (and Greek) culture by Rome, and their patron deity Athena having to share her home, the Acropolis, with the goddess Roma when the imperial cult was established in the city. Arguably nowhere is the mastery of Rome more evident than on an inscription on the famous Arch to Hadrian of AD 132: “This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus.”

At first sight we have a dreary, unexciting, second-rate Athens compared to its illustrious past. Nothing is further from the truth, as I show in my Athens After Empire. Instead of studying post-Classical Athens just in the “Hellenistic” era (from Alexander’s death in 323 to 30, when Egypt fell to Rome), as is the norm, I take Athenian history as a single block from Alexander’s death to AD 132 under Hadrian.

Certainly, Athens suffered in this long period. But as in Classical times, the people’s nature never changed: they fought for freedom and to regain their democracy, even against impossible odds. Their resilience and defiance are defining features that hitherto have been overlooked.

Thus in 268, despite Macedonian troops in their city, the Athenians allied to Egypt and Sparta against Antigonus II of Macedonia in the Chremonidean War. Seven years later, Antigonus had defeated his enemies, and Athens suffered his wrath. But in 229 the city managed to regain its independence, carefully remaining neutral while it tended to its standing in Greece and overseas as well as economic recovery. Then came warfare with Philip V of Macedonia in 200, with the people turning to Rome for help against his attacks.

Still, Athens continued to increase its influence, though always under Rome’s thumb. When in the 80s Mithridates VI of Pontus (Black Sea) called on the Greeks to support his war against Rome in return for championing their freedom, Athens was quick to join him. That decision led to their darkest hour, when in retaliation the Roman general Sulla besieged and sacked the city in 86, slaughtering indiscriminately and destroying many buildings.

Decades of economic distress followed until the Athenian recovered, ironically restoring some buildings and constructing a new market area funded by Roman money—specifically from Pompey and Caesar. Then came the final years of the Roman Republic, in which Athens found itself as a refuge for Brutus after Caesar’s assassination, as a home for Mark Antony after he defeated Brutus and Cassius, and as subservient to Octavian after the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at Actium.

Even so the people stayed defiant. When Augustus visited the city in 21, he was angered that they had splashed blood on the statue of Athena on the Acropolis and turned it to face westward, making it look like the goddess was contemptuously spitting on Rome. Under the emperors the Athenians were left to their own devices, though they singled out Claudius for special honors and received a visit from Trajan. Then under Hadrian the city was catapulted again to prominence in the Greek world, for in AD 132 he made it the center of his new league of cities in the east, the Panhellenion.

That is why the fall of Greece to Macedonia and the policies of Hadrian bookend post-Classical Athens: from dominance to fall to resurrection. And during that time many of the city’s institutions, religious and civic, continued to function (albeit restricted), and as the center for philosophy and rhetoric it enticed many Romans to visit and study there and to appropriate aspects of Greek culture for their own political and cultural ends.

Athens was still a vibrant city, its rich and varied history continued, and it commanded respect in the Greek world and even Rome. Some years after Chaeronea, the orator Demosthenes argued that while the Athenians lost that battle, they had fought for the noblest of causes, freedom, and would have made their ancestors who fought the Persians for the same ideal proud. The Athenians of the post Classical period were no different; they were often down, but never out.

The post Down but never out appeared first on OUPblog.

November 16, 2020

So you think you know Shakespeare? [Quiz]

In order to celebrate the release of Shakespeare: A Playgoer and Reader’s Guide, we created a quiz to see how well you know Shakespeare’s plays! Put your knowledge to the test and see how many of these famous quotes you can correctly complete. Are you a beginner bard enthusiast, or are you secretly Shakespeare himself? Why not find out?

The post So you think you know Shakespeare? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers