Oxford University Press's Blog, page 127

November 4, 2020

Spain sets its hopes on the EU’s COVID-19 pandemic recovery fund

Spain will receive a tsunami of money from the European Union’s COVID-19 pandemic recovery fund if it meets the strict conditions. The magnitude of the amount can be judged from the fact that it is more than the $12 billion Marshall Plan (equivalent to €112 billion today), launched in 1948 by the US to help re-build non-communist war-torn Europe, and from which Spain was excluded because the Franco dictatorship took Hitler’s side.

The country, with the highest number of COVID cases in Western Europe and the sixth in the world (more than 1.1 million cases and over 35,000 deaths), sorely needs the money. The economy is the worst hit by the pandemic among EU countries, largely because of the disproportionate importance of tourism which generates up 12.3% of GDP and one in every seven jobs. There were only 15.7 million tourists in the first eight months of this year, 73% fewer than in the same period of 2019. The IMF expects the economy to shrink 12.8% this year and the fiscal deficit to rise to 14.1% of GDP.

The declaration of a six-month state of emergency as of 25 October, which gives Spain’s 17 regional governments powers to introduce tougher restrictions, and a nationwide overnight curfew (from 11pm to 6am) will aggravate the already dire economic impact.

Such a large amount of money from the Next Generation EU plan, roughly split between grants and loans, will sorely test Spain’s administrative capacity to adequately plan and execute the funds.

If the recent past is anything to go by, the outlook is not good. As of 23 September 2020, Spain had only absorbed 39% of the money it was due from the European Structural Investment Funds for the 2014-2020 period. Only 12% of the European Commission’s country-specific recommendations, issued every year under the Semester Framework, between 2011 and 2019 have so far been implemented. Spain also has a poor record in some cases of not spending funds it has budgeted. For example, in 2018 the public sector failed to execute almost half the money allocated for research and development (R&D).

“Now is the time to invest in human capital, long

neglected, and not physical infrastructure.”

Spain has been very successful in using EU cohesion funds for large infrastructure projects, such as the high-speed rail network, the world’s second longest after China. Now is the time to invest in human capital, long neglected, and not physical infrastructure (the construction sector is the source of much of Spain’s corruption) and emerge with an economy that is less dependent on tourism and more knowledge-based, digital, greener, and inclusive.

The European Commission wants countries to include in their investment plans and reforms the following areas:

Power up: Frontload future-proof clean technologies and accelerate the development and use of renewables.Renovate: Improve the energy efficiency of public and private buildings.Recharge and Refuel: Promote future-proof clean technologies to accelerate the use of sustainable, accessible and smart transport, charging and refuelling stations and extension of public transport.Connect: Rollout rapid broadband services to all regions and households, including fiber and 5G networks.Modernise: The digitalisation of public administration and services, including judicial and healthcare systems.Scale-up: Increase European industrial data cloud capacities and develop the most powerful, cutting edge, and sustainable processors.Reskill and upskill: Adapt education systems to support digital skills and educational and vocational training for all ages.The money will not be a panacea for Spain’s deep structural problems. Reforms are urgently needed, particularly in the unsustainable state pension system (Spain is forecast to have the world’s longest life expectancy by 2040) and the dysfunctional labour market (the unemployment rate was 14% before the pandemic, double the EU average, and is rising). Reforming these two areas could be a prerequisite for accessing the EU’s fund.

Not only has the pace of reforms slowed down in recent years, partly because there have been four inconclusive general elections in as many years (a record for an EU country), but successive governments have been particularly prone to overturning the reforms of their predecessors.

The minority coalition government, led by the Socialist Pedro Sánchez, has to send to Brussels by the end of the year its programme of reforms and how it plans to invest the money (70% of it in 2021 and 2022), and by next April the definitive programme. If one EU member state questions Spain’s flagging commitment to reforms, it can delay disbursements and take the issue to EU leaders for debate.

The European Commission has long taken issue with the direction of the Spanish economy, calling on governments to lower the very high level of temporary employment (more than 25% of total jobs), strengthen vocational training, reduce the 17.3% early school-leaving rate, and foster innovation. Long before the pandemic Spain was far from reaching the Europe 2020 targets, the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs, based on five goals for employment, R&D, climate change, education, and poverty and social exclusion.

Building a knowledge-based economy is being held back by the low educational attainment of 25 to 34-year-olds, one-third of whom in 2018 did not have any higher education qualifications after completing their compulsory secondary education. At the other end of the education spectrum, the recovery fund gives Spain an opportunity to attract back the legions of scientists, engineers, doctors, nurses, and other skilled workers who left the country during the 2008-2013 Great Recession, following the global financial crisis and the bursting of Spain’s massive property bubble.

Spain has a chance to make its economy more sustainable, innovative, productive, and resilient. Whether it does so remains to be seen.

Featured image by Shai Pal

The post Spain sets its hopes on the EU’s COVID-19 pandemic recovery fund appeared first on OUPblog.

November 3, 2020

Supermassive black holes: monsters in the early Universe

When matter is squashed into a tiny volume the gravitational attraction can become so huge that not even light can escape, and thus a black hole is born. A star such as the Sun will never leave a black hole because the quantum forces between matter stop this from squeezing into a sufficiently small volume. Once the Sun dies it will merely leave a white dwarf star, which slowly cools and dims over billions of years. But when the nuclear furnace of a star weighing more than approximately 20 times the Sun exhausts itself, the quantum forces cannot halt its immense gravitational collapse, sparking its explosion as a supernova and often leaving a stellar mass black hole in memory of its previous glory. Such a black hole weighs from a few Suns to perhaps a few dozen. But black holes weighing millions of Suns have been found. And these monstrous things are aptly called super-massive black holes.

As a result of very arduous observations, astronomers have discovered that more-massive elliptical galaxies have bigger super-massive black holes and that these super-massive black holes appear extremely rapidly after the birth of the Universe. This raises three hitherto baffling questions:

How can super-massive holes even form?Why do heavier elliptical galaxies contain heavier super-massive black holes? The most-massive galaxies, weighing more than a hundred times the Milky Way in stars, have super-massive black holes that nearly reach the mass of the Milky Way.How can such incredibly heavy super-massive black holes form within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang when this is basically in the first blink of the cosmic baby’s eye?The biggest problem is that there is no known physics that can be used squash the fantastic amount of normal matter into a sufficiently small volume to make a super-massive black hole within a hundred million years. The matter resists: if squashed too much it becomes relativistic and radiates much of its mass in the form of photons. So, to try and tackle this issue, some wild theories have been developed in the hope of finding an explanation.

Some of these theories have tried to utilise exotic primordial black holes or with dark matter, while others have attempted to construct hyper-massive stars that collapse to black holes weighing more than a hundred solar masses. Some have even tried to use combinations that also invoke special ways of accreting normal matter onto such a seed-massive-black hole. All of these theories are problematical as they are based on hypotheses that have not been confirmed by observation. For example, the evolution of the first putative hyper-massive stars is extremely uncertain because such objects should blow off most of their mass within the first million years.

In spite of the seemingly unsolvable nature of this issue, a team of astrophysicists from Charles University in Prague, Bonn University, the European Space Agency, and the University of Tokyo may have solved all three problems simultaneously.

The team noted that when two black holes merge then approximately 95% of the mass combines to the new more massive black hole with only a tiny amount of the rest being radiated as gravitational waves. This is very nicely shown by the ongoing detection of merging black holes using gravitational wave detectors. They also noted that stellar populations that form in the very early Universe, when there is only hydrogen and helium, are dominated by massive stars weighing more than 20 and up to 150 or so Suns. Additionally, they also indicated that more-massive elliptical galaxies formed more quickly thereby transforming their gas more vigorously into stars. The final ingredient of this theory is that the more vigorously the galaxy forms its stars, the heavier the star clusters are that form in the galaxy at its centre.

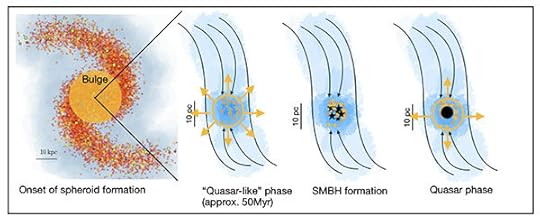

Figure 1: The stages of formation of supermassive black holes: the first extremely massive cluster forms at the centre of the later galaxy and looks like a quasar for about 50Myr. Gas inflow then collapses the remnants of the stars (the black hole cluster) into a super-massive black hole seed which continues to grow as gas falls onto it as long as the galaxy keeps forming (the true quasar phase).

Figure 1: The stages of formation of supermassive black holes: the first extremely massive cluster forms at the centre of the later galaxy and looks like a quasar for about 50Myr. Gas inflow then collapses the remnants of the stars (the black hole cluster) into a super-massive black hole seed which continues to grow as gas falls onto it as long as the galaxy keeps forming (the true quasar phase).The astrophysicists computer-coded the above and calculated what happens when an elliptical galaxy begins to form when, roughly two hundred million years after the Big Bang, the gas in the cosmos had sufficiently cooled through its expansion to gravitationally collapse. The first-formed extremely massive star clusters were full of heavy stars, leaving many millions of normal black holes in regions spanning not much more than 10 light years across. This was over after about 10 to 20 million years when the last massive star died. But around these first clusters of black holes, the elliptical galaxies were just starting to form. The formation of a whole galaxy continued for about a billion years and, during this extremely violent time, very large amounts of gas fell onto the cluster of black holes near its centre. The gas squeezed the cluster together until the black hole velocities within the cluster became relativistic. At this point, the cluster of black holes started radiating a critical amount of its energy as gravitational waves. It consequently collapsed within a dozen million years to a combined black hole mass of a hundred thousand to millions of Suns. As the elliptical galaxy continued to form around this massive black hole, gas kept falling onto it so that it grew more in mass as a quasar, with additional massive elliptical galaxies hosting more massive central black holes that grew faster.

Using conventional physics and the most updated observational data, this theory thus answers all three questions noted above and makes two predictions:

The very first quasars may not be actually accreting super-massive black holes, but the extremely early hyper-massive star clusters containing many millions of brilliant massive stars could be the precursors of real accreting super-massive black holes.When the cluster of black holes reaches its relativistic state, its hundreds of thousands and millions of black holes will be radiating gravitational waves in bursts as the black holes pass each other ever more frequently. This type of signal still needs to be calculated in detail and should allow this theory to be tested the future gravitational wave observatories.

Featured image: Using the Event Horizon Telescope, scientists obtained an image of the black hole at the center of galaxy M87, outlined by emission from hot gas swirling around it under the influence of strong gravity near its event horizon. (By Event Horizon Telescope et al. via Event Horizon Telescope.)

The post Supermassive black holes: monsters in the early Universe appeared first on OUPblog.

November 2, 2020

When deterrence doesn’t work

No one likes to be threatened, and yet we threaten and are threatened all the time. It’s a dark prospect, but the reality is that threats are the ocean in which we swim. And it’s not just human beings: animals, too, and even plants, engage in a great deal of threatening, endeavoring to change the behavior of other living things by, well, threatening that if they don’t relent, they’ll regret it.

And so, many plants have evolved thorns or toxic chemicals to keep predators away. As for animals, the manifestations of threat are immense. In some cases, the threat is built into a creature’s body, as with menacing teeth, horns, claws, and other structures devised by evolution to emphasize an animal’s dangerousness. And of course, most animals have some way of attempting to deter or otherwise influence others by exaggerating their competence and often, their ferocity. In others, the threat is more subtle, but no less effective, as with those animals that have evolved conspicuous warning coloration—typically dramatic (and often to the human eye, quite beautiful) color patterns that are easily noticed and, if need-be, learned by a potential predator, which then avoids whoever is carrying such advertising because the bearers are liable to be bad-tasting or even lethally poisonous.

Intriguingly, once the biological door is opened to such threats, another evolutionary option is also made available: insofar as there is a payoff to being perceived as dangerous—whether via fighting capacity or internal biochemistry—the prospect beckons for evolutionary dishonesty to evolve. Why not exaggerate your capabilities as well as your intentions, thereby gaining the benefit of getting others to defer without having to actually invest in the underlying machinery (which is often metabolically expensive), or running the risk of having to actually back up your intimidating claims? In fact, many living things do just this, putting on a threatening show that is, at bottom, no more than a show. But this tactic carries its own drawbacks, notably the prospect of having your bluff called! The result is a series of evolutionary arms races, or cat-and-mouse games, in which individuals benefit by issuing threats insofar as recipients are especially inclined to take them seriously because the consequences of ignoring or challenging them could be severe. At the same time, however, when such communication is bluster (i.e., “dishonest”), there can be a payoff to calling the bluff… which, in turn, conveys a cautionary brake on threat-conveyers going too far. This dynamic plays out for many animals, including birds, mammals, even fish and, notably, snapping shrimp, whose “snaps” tell a memorable tale.

The harmless Scarlet Kingsnake mimics the appearance of the poisonous Coral Snake to avoid predation. (Image by Peter Paplanus)

The harmless Scarlet Kingsnake mimics the appearance of the poisonous Coral Snake to avoid predation. (Image by Peter Paplanus)Threats are of course prominent among human beings, too: do this, or else! Alternatively: don’t do that, or else! Child-rearing is a frequent although regrettable domain of threat giving and receiving. So is the arena of childhood bullying. Above inter-individual threats, the phenomenon is perhaps at its most dramatic at the social level. The punishment of criminals has an ancient and often bloody history, motivated in part by the perception (more like a hope) that by threatening dire consequences for serious crimes, people will be prevented from transgressing in the first place. This is italicized in the especially tragic case of capital punishment. The evidence is overwhelming that executions do not reduce rates of murder, rape, treason, or the like, and yet, belief in the efficacy of this grotesque threat persists (although in diminishing popularity), especially in the US.

Another widespread threat is of eternal damnation—literally “hell to pay”—for sinners, long employed by many religious traditions as a way to subjugate believers and get them to behave “better.” To some extent, this works, although almost certainly at great psychological cost. The social dimension of threats includes reactions to threats no less than the employment of them. For example, the gun culture that has recently erupted in the US has emerged in large part as a reaction by those who feel threatened and whose response (the immense proliferation of lethal weaponry) has paradoxically amplified whatever threats they may perceive, reflected in a grotesquely high rate of gun deaths compared to all other “first world” countries. A similar paradox is found in the peculiar case of right-wing populist nationalism, in which responding to threats has often backfired and made things worse for its supporters. This is notably true, once again, in the US, where white Trump supporters—feeling under socio-economic and racial threat—have in fact suffered most severely under policies promoted by their ostensible savior.

Finally, there is the greatest socially generated threat of all: nuclear deterrence.It is nothing but threat writ large, namely that if they are attacked, a victim’s retaliation will be so devastating as to prevent any such attack in the first place. Although it appears superficially logical, nuclear deterrence is now and has always been a snare and a delusion; moreover, an unacceptably dangerous one.

It has been said that the Emperor Deterrence has no clothes but is still Emperor. In undressing deterrence, we can reveal the nakedness of this particular monarch, notably by identifying a number of skeletons in its closet:

The logical fallacy and historical misrepresentations that have claimed that “deterrence works”The inherent impossibility of establishing any reasonable limit to the question “how much threat is enough?” In other words, at what point can a nuclear country stop building yet more nuclear weaponry?The unacceptable danger that deterrence will fail, as evidenced by the many occasions when it has come terrifyingly close to doing soThe paradox that the problem of “credibility”, which arises because the threat to use nuclear weapons is so devastating to foe and friend alike that it is necessarily lacking in credibility, has induced the development of weaponry that is more useable… which in turn counter-productively makes it more likely to be usedThe progression toward “counterforce targeting” (aiming at the nuclear weapons of a potential opponent), which raises an increasing prospect that in the event of a crisis, the potential victim, thinking that it might be attacked because its supposed deterrent is undermined, could well be tempted to strike first, leading to a chain of instability in which each side feels impelled to pre-empt the otherThe fact that deterrence assumes that in conditions of extreme tension, national leaders will respond with careful and detailed rationality, whereas everything that we know of human behavior indicates that this would not be the caseThe fact that deterrence assumes sanity on the part of world leaders, yet another assumption that a familiarity with world history shows to be a fallacyThe well-documented reality that issuing nuclear threats simply does not work, even against non-nuclear countriesThe extent to which deterrence itself has been the primary justification for maintaining nuclear arsenals and in many ways accelerating their lethality and the likelihood that rather than preventing their use, they will someday be usedThe fact that even threatening an action that would be devastating to the survival of life on earth is itself deeply immoral, as testified by most of the world’s great religious and ethical traditions.Threats are some of the most important and intellectually challenging phenomena of all time, calling out for greater understanding and, one can hope, wisdom.

Featured image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The post When deterrence doesn’t work appeared first on OUPblog.

Girls, women, and intellectual empowerment

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s nickname in law school was “Bitch.” Senator Elizabeth Warren was sanctioned by her GOP colleagues when “nevertheless, she persisted” in her questioning of soon-to-be Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Senator Kamala Harris reminded Vice President Mike Pence “I am speaking, I am speaking,” as he attempted to interrupt and speak over her in a recent vice presidential debate. CNN found it more important to report that two women won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry than to report the names of the women who won it.

Women and intellectual disempowermentThough we may wish to think it otherwise, women and girls are still routinely silenced and excluded from positions of power, expertise, leadership, and full participation in the public sphere.

Ample empirical evidence supports this claim. In the classroom, girls and young women are regularly silenced. Teacher biases can lead to teachers spending up to two-thirds of their time with male students. Teachers also interrupt girls more frequently and allow boys to speak over them. Students themselves play out these gendered assumptions and normalizations and boys believe girls talk too much, when in fact, boys speak far more often, and more authoritatively, than girls.

On the faculty side, several studies that show men speak more often and for longer amounts of time in faculty meetings. When women do speak more frequently, they are assessed as less competent than their male peers. Sources show that assertive women are considered bitchy, including this study from 2014, which also shows that women are given far more critical feedback from their bosses than their male counterparts. Likewise, a 2017 study of employee management shows that “[m]en who spoke up with ideas were seen as having higher status and were more likely to emerge as leaders. Women did not receive any benefits in status or leader emergence from speaking up.”

The newly coined term, “hepeating,” gets to the experience that professional women often have when hearing their ideas repeated by men—and then valued as they ought to have been in the first place. Other terms come and go in contemporary discourse. “Correctile dysfunction” and “mansplaining” (as well as the spatial corollary, “manspreading”) point to the ways that men are granted authority in terms of knowledge. Furthermore, while many workplaces have indeed seen an increase in “whole binders full of women,” women’s credibility in intellectual realms is clearly still seriously lacking.

This epistemic undermining is ethically harmful to both the individual herself and has broader social/collective consequences. Consider:

On an individual level: When people are undermined specifically in what philosopher Miranda Fricker calls their “capacities as knowers” (Epistemic Injustice 2007), they are prohibited from exercising their full human range of reasoning. If a person lacks confidence in her ability to reason due to structural or identity prejudice, she is ethically harmed as a person. Epistemic conduct (i.e., the habits and characteristics of knowing), then, bears upon an individual’s personal development. Thus, when an individual person is undermined in her capacity as a knower, she is thwarted in her own projects, prohibiting full growth in her ability to cultivate epistemic insights and understand herself specifically as a knower.On a social level: When people are undermined in their capacities as knowers, everyone suffers. Fewer ideas become available in our collective social imagination; the scope of knowledge itself persists in its gendered stereotypes; problem-solving is weaker and less creative; and even workplaces are less productive and lucrative.Women and intellectual empowermentIntellectual empowerment does not mean that a person’s ideas are simply right by virtue of her having them, but it does mean that that person has a right to her ideas—and that her ideas may have positive value. The idea of “empowerment” doesn’t collapse into having opinions validated but instead points to the hard work demanded of intellectual life through continued deliberation, critique, and dialogue. Intellectual empowerment validates a person as a knower, even if or when she makes mistakes. Indeed, we might say that making mistakes is critical in helping a person cultivate her intellectual empowerment, especially in terms of gender schemas that put enormous pressure on girls and women to be “perfect” and not make such mistakes.

There are steps to take both within our discipline of academic philosophy and academia at large to offer correctives to the widespread exclusion of women in the academy. Consider the following possibilities:

Refuse to participate in all-male panels. “Congrats, you have an all-male panel!” is a phrase used to raise awareness via social media about conferences that feature only men when speaking about intellectual matters. Academics have begun pledging to not present their work at a conference if the only participants sharing ideas are men.Ensure that a variety of formative assessments, rather than purely summative assessments that rely on memorization and repetition, are given in a classroom. Reinforcing dominant hierarchies of understanding through the “banking method” maintains a male-dominated status quo.Seek out anthologies that include an abundance of women authors and avoid anthologies that exclude women or relegate them to sections on women only, or feminism, for use in your scholarship and in your classes.Cite women in scholarly articles; use “she/her” and “they/them” pronouns when teaching and writing; encourage students to do the same.Provide space for reflection and dialogue about philosophical issues in intentional ways that go beyond typical debate-style interrogations in philosophy in particular and academia at large.Participate in climate studies at universities, gender and racial inequity initiatives, and other service-oriented opportunities.Insist that women should not be responsible for the bulk of the invisible labor (service work for departments, programs, and universities) that keeps them from their research and scholarship.Contribute to anthologies, workshops, journals, and conferences hosted and run by women, especially if you are well-established in your field.In short, we can all be self-critical and open to learning about harmful behaviors and practices that come from epistemic injustices and take concrete steps to enact change on individual, institutional, and societal levels. Empowering girls and young women intellectually is crucial to the future of the discipline of philosophy, especially in light of crises of the humanities in our time.

Featured image by Margarita Zueva

The post Girls, women, and intellectual empowerment appeared first on OUPblog.

November 1, 2020

How did the passive voice get such a bad name?

Many grammatical superstitions and biases can be traced back to overreaching and misguided language critics: the prohibitions concerning sentence-final prepositions, split infinitives, beginning a sentence with a conjunction, or using contractions or the first person.

One bias whose origin is more elusive is the dissing of the passive voice. When did writers concerned with writing start to worry about the passive? My best guess is the early twentieth century, after college education had expanded and freshman composition became a staple of the English curriculum.

In 1871, Harvard’s president Charles William Eliot complained that young men entering his university exhibited “Bad spelling, incorrectness as well as inelegance of expression in writing, [and] ignorance of the simplest rules of punctuation.” Shortly thereafter, in 1885, Harvard required a course in freshman composition known simply as English A. By 1890, the majority of American colleges had followed Harvard’s lead in requiring a composition course.

Textbooks for the courses appeared, including Barrett Wendall’s 1891 English Composition. Regarding the passive, Wendall simply remarked that its function “is to effect a separation between an action and the agent” and that “we may with perfect propriety wish to express either” the passive or active voice.

Wariness of the passive shows up in the privately-printed first edition of William Strunk’s The Elements of Style in 1918. Strunk wrote that the active voice was “more direct and vigorous” than the passive, which “sometimes results in indefiniteness.”

Strunk was not the first to come to this conclusion. In his introduction, he wrote that George McLane Wood had contributed examples to the discussion of the passive. Wood was the editor of the US Geological Survey, and his 1913 Suggestions to Authors warned about the “undesirable use” of the passive when conjoined with the active, as in “These creeks flow through broad valleys until the brink of the Clealum Valley is reached” and similar examples.

Strunk also cited other works, notably The King’s English by the brothers Fowler as well as Arthur Quiller-Couch’s 1916 book On the Art of Writing. The Fowlers merely mention the “trap” of vagueness that arises in complex sentences, prescribing “we must admit” in place of “it must be admitted” and “that they put forward” in place of “a policy put forward.” Quiller-Couch offered three bits of advice on straightforward prose: prefer the concrete to the abstract, prefer the direct word to the circumlocution, and

Generally, use transitive verbs, that strike their object; and use them in the active voice, eschewing the stationary passive, with its little auxiliary its’s and was’s, and its participles getting into the light of your adjectives, which should be few. …

The passive is also mentioned in the 1918 Century Handbook of Writing by Garland Greever and Easley Jones. It gave one hundred rules of writing; rule 46 was titled “The Weak Effect of the Passive Voice” and asserted, “Use the active voice unless there is a reason for doing otherwise. The passive voice is, as the name implies, not emphatic.”

As composition textbooks flourished in the early twentieth century, screeds about the passive were common; linguist Arnold Zwicky has documented several from the 1930s and 1940s including one that gives a two-page attack on the passive style and the passive voice, which “shows action in reverse” and “makes meaning static.”

By the time, George Orwell flatly stated, “Never use the passive where you can use the active,” in his 1946 “Politics and the English Language,” bias against the passive was pretty much fixed in the rhetorical canon. The mass publication of The Elements of Style in 1959 introduced that oversimplification to generations of American writers, but its origins lie in George McLane Wood’s Suggestions to Authors and Arthur Quiller-Couch’s lectures On the Art of Writing.

And there’s no need to shy away from it.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

A change in Brazil’s national populist government

As we approach 15 November, a national holiday marking the end of the Brazilian Empire and proclamation of the Brazilian Republic in 1889, and also a day of municipal elections, many Brazilians may be contemplating what has happened to their country and where it might be heading.

In October 2018 a national populist candidate, Jair Bolsonaro, won the presidency by campaigning on the slogan “Brazil above everything, God above everyone.” Bolsonaro is populist in the sense described by the political scientists Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser: he embodies a world view “that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic camps, `the pure people’ versus `the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté général (general will) of the people.” An obscure member of Congress for 27 years and a former army captain, Bolsonaro used social media, especially Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, to win the country’s highest office. His untraditional and Trump-inspired campaign channeled the Brazilian public’s frustration with an enormous government corruption scandal and the established political parties, as well as disillusionment with the governments of the centre-left Workers’ Party, which had controlled the presidency from 2003 to 2016.

Bolsonaro offers the usual tropes of national populists—religious nationalism, illiberalism, cultural conservatism, the exaltation of the armed forces (many retired and active-duty members serve in his government), a reverence for the patriarchal family, aggressive anti-Communism, and attacks on globalism and multilateralism, as well as criticism of the mainstream media and its “fake news.” However, in at least two respects he is different from most of his counterparts, who tend to rely on strong party machines and espouse economic protectionism. Bolsonaro has no political party, having fallen out with the colleagues with whom he temporarily allied in the 2018 election. He also campaigned on the promise of implementing ultra-neoliberal economic policies, appointing a University of Chicago alumni, Paulo Guedes, to be his “super minister” of the economy. Guedes pledged to downsize the state, lighten the tax burden, privatize state-owned firms, flexibilize labour markets, and achieve rapid economic growth through neoliberal shock therapy.

That has not happened. Bolsonaro’s government spent much of 2019 enacting a reform of the public pension system in order to halt the growth of the fiscal deficit. Most of the rest of the neoliberal package, including a reform of the tax system, was not implemented. This year the coronavirus pandemic has hit Brazil hard, in part because of President Bolsonaro’s cavalier dismissal of the disease and his refusal to use the federal government to coordinate the public health response in states and municipalities. The country has the second highest number of COVID-19 deaths in the world behind the United States, with over 140,000 deaths officially recorded (at time of post publication; see John Hopkins University COVID-19 dashboard). Many people in crowded low-income neighbourhoods in urban peripheries have found it difficult to self-isolate, and the government was induced to pay an emergency income supplement to the poor of R$600 (about £90) per month for three months, and then extended it for two more months in August and September. The income support now reaches 65 million beneficiaries, or more than 30% of the population of roughly 210 million, and the Bolsonaro administration has proposed to continue it until December at half of its initial value.

“However, despite the economic and public health disasters … his approval rating reached 40%, the highest level of his presidency.”

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and the collapse of the economy, neoliberal shock therapy—which was never seriously attempted in 2019—was abandoned. The fiscal deficit, which the super-minister Paulo Guedes promised to reduce to zero in his first year, has ballooned. Gross national debt is expected to reach 93.5% of GDP, the economy could shrink by up to 6% this year, and the official unemployment rate is over 13%.

However, despite the economic and public health disasters, President Bolsonaro has discovered the political benefits of directly supporting the incomes of the poor in a country in which the average wage is only £330 per month. His approval rating reached 40%, the highest level of his presidency, in a CNI poll of 2,000 voters conducted on 17-20 September 2020. The emergency supplement does not explain all of this rise, but it accounts for some of it, and the President has picked much of his new support in the impoverished north and northeast of the country. It may be that President Bolsonaro has decided that neoliberalism is not essential to his national populist movement, and that he can compensate for loss of support amongst higher-income groups with an increase in support amongst the more numerous poor. Just as the anti-corruption plank of his platform was muted with the resignation in April 2020 of his Minister of Justice, former federal judge Sérgio Moro, and revelations of the investigation of possible corruption on the part of his son Flávio Bolsonaro when he was a Rio state legislator, neoliberalism may prove to be a disposable element of this government.

President Bolsonaro’s rule and his movement are likely to go through further changes. If President Trump of the USA fails to secure re-election on 3 November, that could weaken Bolsonaro’s support base. The November municipal elections could see the ascension to office of a raft of opponents of Bolsonaro who articulate widespread indignation at the president’s handling of the coronavirus crisis and his style of rule. Looking farther ahead, the bicentennial of Brazil’s independence in 2022 will probably coincide with President Bolsonaro’s attempt to secure his own re-election. At that point Brazilians will discover whether an incumbent saying “Brazil above everything, God above everyone” can win a second term.

Featured image by Sergio Souza from Unsplash

The post A change in Brazil’s national populist government appeared first on OUPblog.

October 31, 2020

Seven books for philosophical perspectives on politics [reading list]

2020 has come to be defined by widespread human tragedy, economic uncertainty, and increased public discourse surrounding how to address systemic racism. With such important issues at stake, political leadership has been under enormous scrutiny. For some countries, this has coincided with their election season: Jacinda Ardern has just won her second term in office and the 2020 US presidential election will take place on Tuesday 3 November.

As the US election approaches, we’re featuring a selection of important books exploring politics from different philosophical perspectives, ranging from interrogating the moral duty to vote, to how grandstanding impacts public discourse.

1) A Duty to Resist: When Disobedience Should Be Uncivil, by Candice Delmas

What are our responsibilities in the face of injustice? In this book, Candice Delmas argues we have a duty to resist injustice: a duty that, sometimes, is more important than our duty to obey the law. Drawing from the tradition of activists including Henry David Thoreau, Mohandas Gandhi, and the Movement for Black Lives, A Duty to Resist wrestles with the problem of political obligation in real world societies that harbor injustice.

Read a free chapter online.

2) Overdoing Democracy: Why We Must Put Politics in its Place, by Robert B. Talisse

Robert B. Talisse turns the popular adage “the cure for democracy’s ills is more democracy” on its head, arguing that the widely recognized, crisis-level polarization within contemporary democracy stems from the tendency among citizens to overdo democracy. Talisse advocates civic friendship built around shared endeavors that we must undertake with fellow citizens who do not necessarily share our political affinities as the best way we can obtain a healthier, more sustainable democracy.

Read a free chapter online.

3) John Rawls: Debating the Major Questions, edited by Jon Mandle and Sarah Roberts-Cady

John Rawls is widely considered one of the most important political philosophers of the 20th century, and his highly original and influential works play a central role in contemporary philosophical debates. This collection of essays provides readers with clear and in-depth explication of Rawls’s arguments, the most important critical dialogue generated in response to those arguments, and the dialogue’s significance to contemporary politics.

Read a free chapter online.

4) The Duty to Vote, by Julia Maskivker

If you can vote, you are morally obligated to do so. As political theorist Julia Maskivker argues, voting in order to improve our fellow citizens’ lot is a duty of justice. In a time of polarization and political turmoil, The Duty to Vote offers a stirring reminder that voting is fundamentally a collective endeavor to protect our communities, and that we all must vote in order to preserve the free societies within which we live.

Read a free chapter online.

5) Structural Injustice: Power, Advantage, and Human Rights, by Madison Powers and Ruth Faden

This book puts forward a groundbreaking theory of social injustice which forges links between human rights and fairness norms. Norms of both kinds are grounded in an account of well-being. Their well-being account provides the foundation for human rights, explains the depth of unfairness of systematic patterns of disadvantage, and locates the unfairness of power relations in forms of control some groups have over the well-being of other groups. They explain how human rights violations and structurally unfair patterns of power and advantage are so often interconnected.

Read a free chapter online.

6) Must Politics be War? Restoring Our Trust in the Open Society, by Kevin Vallier

American politics seems like a war between irreconcilable forces and so we may suspect that political life as such is war. This book confronts these suspicions by arguing that liberal political institutions have the unique capacity to sustain social trust in diverse, open societies, undermining aggressive political partisanship.

Read a free chapter online. Kevin Vallier’s latest book,

Trust in a Polarized Age is now available to purchase online.

7) Grandstanding: The Use and Abuse of Moral Talk, by Justin Tosi and Brandon Warmke

Why does talk about politics and moral issues tend to get so ugly, heated, and personal? So much public discussion goes awry because people are using it for the wrong reasons. Too often, especially online, people engage in moral grandstanding—they use moral talk to impress others by showing them they have the right views. Tosi and Warmke show why people behave this way, why it’s wrong, and what we can do about it.

Read a free chapter online.

The post Seven books for philosophical perspectives on politics [reading list] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 30, 2020

President Trump and the war against American Christianity

On 7 October, shortly after being hospitalised after contracting COVID-19, President Donald Trump took to Twitter to warn his supporters that “DEMS WANT TO SHUT YOUR CHURCHES DOWN, PERMANENTLY. HOPE YOU SEE WHAT IS HAPPENING. VOTE NOW.”

DEMS WANT TO SHUT YOUR CHURCHES DOWN, PERMANENTLY. HOPE YOU SEE WHAT IS HAPPENING. VOTE NOW! https://t.co/dqvqz6b1WD

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 7, 2020

The event that occasioned his comment had taken place in Moscow, Idaho, in late September, when members of one of the city’s largest Protestant congregations had gathered to sing hymns in defiance of local social distancing regulations and in front of city hall. Several attendees took videos that showed police detaining Gabe Rench, a member of the community and host of an online religious politics talk-show, for the violation of these rules. That evening, Rench and the other presenters of “CrossPolitic” publicised the incident, asking supporters to share footage of the arrest as widely as they could. As good postmillennialists, members of this community tend to be pretty optimistic—but, even so, they could hardly have imagined that, just over one week later, the incident would become the subject of comment by the President himself, as he shared news of the persecution of American Christians with 87 million followers on Twitter.

Although I have not met Rench, I did spend time with members of his community while doing fieldwork for my forthcoming book, Survival and resistance in evangelical America: Christian Reconstruction in the Pacific Northwest. The community had been established in Moscow in the 1970s under the charismatic leadership of Douglas Wilson. As it grew in number, the community embraced Reformed theology, establishing a second church, and then a new denomination; a classical Christian school, and then an association of such schools; a liberal arts college with an impressive record of sending students into top-quality graduate programmes; and projects in arts and media that have resulted in book deals with publishers ranging from Penguin Random House to Oxford University Press, film and book collaborations with Christopher Hitchens, as well as talk-shows on Amazon Prime and cartoons on Netflix.

Yet, for all their success, the values that have informed these projects have been radically counter-cultural. For the goal of this community is to make Moscow a Christian town—in the expectation that its religious values will one day become those of the entire world. Progress towards these goals has been hard-won, but real enough. Around one-tenth of the permanent residents of Moscow are now members of the community’s two congregations, and, with the support of entrepreneurs and creatives, their values are being disseminated throughout American mass culture.

So, while members of the community might have welcomed the President’s tweet, his support for their cause was, in many ways, ironic. The community that he identified as exemplary of Christianity in the United States of America has very strong views about politics—views that tend not to coalesce with his own. Over the last three decades, Wilson and other community leaders have argued that the best foundation for civil society is to be found in biblical law, and they have proposed a lightly edited version of the programme for Christian Reconstruction that has been so controversial elsewhere. Some of the ideas that community members have mooted—including the suggestion that American slavery was not necessarily wicked—have caused distress and outrage in the locality, with the consequence that many of the more liberal residents of Moscow now boycott the community’s shops (and bar). Of course, as I have already noted on this blog, some of these once outré ideas have gained considerable currency in Republican circles. But, in my fieldwork in this community, in the summers of 2015 and 2016, I did not discover anyone who was planning to vote for Donald Trump. Like others who support the agenda for Christian Reconstruction, the Moscow Christians tend not to look for top-down political solutions, having rejected the political mainstream and the bankrupt agenda of the Religious Right. The President might support the Moscow Christians but they may not be supporting him.

For all that the Moscow Christians might appreciate the president’s interest in their affairs, they are not looking to achieve their goals through national politics. After all, many of these believers have difficulty with the democratic system. What “we call… democracy… Solomon called… foolishness,” Wilson has claimed. Members of the community reject the false dichotomy of two-party politics:

“One faction wants to drive toward the cliff of God’s judgement at sixty miles an hour, while the loyal opposition wants to slow down to forty. Hard-working and soft-thinking Christians bust a gut to get the latter group into power. And then, when they do assume control, they compromise with the ousted group and settle on a moderate and well-respected speed of fifty-eight. But the Bible prohibits establishing a ruler—whether a ruler or judge—who does not fear God.”

For these Christians, the reformation of the church must precede any reformation of the nation at large. “Any serious attempts at cultural reform, based upon ‘traditional values,’ which precede a reformation and revival in the church, should be considered by Christians as worthless.” Indeed, they continue, the “severe problems this nation has do not admit of a political or cultural solution,” for the key to the transformation of America is the gospel. America will be transformed. But, they have argued, “why would we use the grimy little god of politics to try to usher in what Jesus Christ has already purchased on the cross with His own blood?”

For all that community members might appreciate the president’s interest, they are certain that he is not the saviour of American Christianity. But the President’s tweet shows how even those who want to stand at a critical distance from the political mainstream can find themselves caught up in it.

Feature image by @balensiefenphoto

The post President Trump and the war against American Christianity appeared first on OUPblog.

Scientism, the coronavirus, and the death of the humanities

“Nearly everyone seems to believe the humanities are in crisis,” huffed the literary scholar Paul Jay in 2014. But Jay wasn’t sold: his skepticism was sufficiently strong, in fact, that he put the word crisis in scare quotes in his book The Humanities “Crisis” and the Future of Literary Studies. Jay turned out to be one among a prominent collection of professors in the 2010s who gainsaid the crisis-talk surrounding the modern humanities.

A few short years later, does anyone still believe this? Although at the time Jay wrote his book the outlook for the humanities in American higher education was far from rosy, the COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the dire circumstances for contemporary humanistic study. Cash-strapped colleges and universities have begun closing humanities departments and ousting faculty members. Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin, for example, announced the discontinuation of its classics, philosophy, and “great ideas” majors, which will put 23 faculty members out of work. Its president concomitantly proclaimed that “Carthage has always been, is, and will always be a liberal arts institution.” Given that the school boasts majors in accounting, finance, and public relations and has dismantled its classics and philosophy departments, one wonders whether its leaders know what the liberal arts are.

To add insult to injury, Illinois Wesleyan University has recently disclosed the shuttering of its classics department and slated programs in religion, French, and Italian for the chopping block. Who’s the president of Illinois Wesleyan? S. Georgia Nugent, a classical scholar and the 2017 president of the Society for Classical Studies. A few years ago, when Paul Jay was denying the crisis for the humanities, Nugent was composing editorials in favor of liberal learning. Now she’s busy stripping away the humanities from her university.

How has this happened? How have humanistic disciplines such as philosophy and classics—which previously played a dominant role in American higher education—found themselves the odd man out of our contemporary curricula? For decades, conservative critics have blamed the bogeyman of postmodernism. In the aftermath of the 1960s, they claim, radicalized humanities professors transformed their disciplines into vehicles for their left-wing politics. College students, sensing that the contemporary humanities offer little but impenetrable prose and radical ideology, have supposedly fled from the study of such subjects for more practical fare.

Unfortunately, though, the cause of the humanities’ current crisis is far older than critics of postmodern relativism allow—and more baked into the heart of the modern American university. In fact, one must look back to very creation of the American universities in the late nineteenth century to see why their triumph precipitated the marginalization of the modern humanities. The scientizing of our higher education amounts to the root of the problem, and without a deep-seated revolt against this process, the humanities will continue to wither.

From the colonial period up until the Civil War in America, the classical humanities were the lynchpin of higher education. The intellectual and moral inspiration for early American higher education derived chiefly from the Renaissance humanists, who contended that the study of ancient Greek and Roman literary masterpieces—when studied in their original languages—could perfect a human being. The young, they thought, should take in the wisdom of authors such as Homer, Plato, Sallust, Vergil, and Augustine, thereby recognizing their own higher potentialities. Given the paramount influence of Renaissance humanism, the early American colleges possessed almost completely prescribed curricula: they required all students to experience those literary masterworks that could best shape students’ souls.

Many Americans proved acutely critical of this classics-heavy curriculum. But such critics did not make much headway against it prior to the mid-nineteenth century. At this time, a group of reformers whom the historian Andrew Jewett has labeled the first generation of “scientific democrats” began to revolutionize higher education in the US, turning it away from Renaissance humanism toward the professionalized sort of scholarly study emanating from Germany. These scientific democrats aimed to center American higher education around the natural and social sciences, believing that the scientific method could supply the tools to maintain a robust democratic society. They therefore shunned the old prescribed course of studies promoted by the Renaissance humanists in favor of a choose-your-own-adventure curriculum inspired by Darwinism and laissez-faire economics. In 1884, Charles W. Eliot, the president of Harvard University and the most energetic promoter of elective coursework, thus maintained that “In education, as elsewhere, it is the fittest that survives.” Rather than provide for students a vision of a well-educated person based on the masterworks of ancient literature, such scientific democrats promoted a Spencerian fight to the death among the disciplines.

Even casual observers of contemporary higher education in the US should recognize how successful these reformers have been in reshaping American colleges and universities. Just as they had hoped, the natural and social sciences—along with various vocational studies first ushered into the curriculum by the scientific democrats—now rule the roost, and the humanities have been brushed aside.

The triumph of the sciences would spell serious trouble for humanism. The latter, after all, foregrounds the wisdom of the past as the means to shape a student’s character. The sciences, by contrast, promote the creation of new knowledge. And the dominance of the scientific outlook in higher education has turned the modern humanities distinctly un-humanistic. Many contemporary humanities professors no longer even seem to believe in humanism. Thus, the professor of English Stanley Fish can announce that “teachers cannot, except for a serendipity that by definition cannot be counted on, fashion moral character, or inculcate respect for others, or produce citizens of a certain temper.” Likewise, in their scholarly publications such humanities professors don’t foreground the ability of masterworks to provide answers to life’s great questions; rather, they typically focus on minute arcana, as if Homer, Confucius, and Jane Austen can best be studied in a lab coat.

All this underscores the serious and longstanding difficulties for the modern humanities. The dominant Darwinian approach to the college curriculum fights against humanistic values: it devalues the wisdom of the past and esteems disciplines on the basis of their popularity alone. The professionalization of American higher education in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has cut professors off from the humanistic tradition, allowing a literary scientism to flourish that is anathema to the proper goals of humanism. Although obviously the natural and social sciences must play an important part in contemporary American education, we must recognize that for well over a century the deck has been stacked against the humanities.

How can we fight against such longstanding troubles for the humanistic disciplines? A revolt against our Darwinian approach to general education would supply a salubrious start. Rather than encourage a curricular survival of the fittest that by design sidelines the humanities, we must demand a globalized core curriculum—one based on required courses devoted to the study of literary masterworks from manifold cultures. Such books can provide for students the most profound responses to the human predicament, enabling the young to determine a sound philosophy of life. Our scientized universities focus almost exclusively on what the great humanist Irving Babbitt called humanitarianism: the drive to improve the material conditions of the world. They desperately require a balancing emphasis on humanism: the drive to improve the self. Bereft of the humanities, education only accomplishes half of what it should. We cannot, of course, improve the world if we cannot improve ourselves. And the humanities cannot thrive without the spirit of humanism.

The post Scientism, the coronavirus, and the death of the humanities appeared first on OUPblog.

October 29, 2020

Listen now before we choose to forget

Memory is pliable. How we remember the COVID-19 pandemic is continually being reshaped by the evolution of our own experience and by the influence of collective interpretations. By the summer of 2020, the Black Lives Matter protests, divisive partisan politics, and anger over extended lockdowns were all influencing how we remember the pandemic.

The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC), where I have worked for over two decades, asked me to design an oral history response to document the pandemic in our area. THNOC is devoted to recording and interpreting the history and culture of New Orleans and has long used oral history as a way to add texture and emotional truth to the historical record.

We formed an oral history response following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 resulting in the collection, over the course of five years, of more than 500 hours of recorded narrative. This effort filled a deep need within our community to reflect and make sense of the experience of the storm and its aftermath.

The evidential value of such work is to some extent dependent on responding quickly to events before our memory is influenced by collective views or changes in our own values and circumstance. That is not to say that our reshaped memories and how and why they have taken new form is without value to historians.

Former Top Chef star Nina Compton is one of the most celebrated young restaurateurs in New Orleans. Her two restaurants are on the brink as social distancing restrictions continue.

Former Top Chef star Nina Compton is one of the most celebrated young restaurateurs in New Orleans. Her two restaurants are on the brink as social distancing restrictions continue.In the case of the pandemic a bigger concern than this reshaping of memory may simply be a lack of desire to remember. The lessons of the 1918 flu pandemic were lost to us largely because we collectively chose to forget. There are likely many reasons for this: a desire to move beyond the political rancor of the time, guilt over not being with loved ones when they passed, or infecting others. Unlike the landfall of a hurricane or a terrorist attack like 9/11, there will likely be no singular anniversary date on which the pandemic will be commemorated. This alone may serve to impact generational remembrance.

Doing oral history now is far from ideal. Lack of resources and social distancing make the interview process challenging and often awkward; but if we don’t listen and record now, there is no guarantee there will be a keenness to do this work in the future. As a community we may just choose to forget.

Director of the New Orleans Department of Health, Dr Jennifer Avegno and Mayor Latoya Cantrell at a daily press conference. They became the face of the struggle against the virus in the city.

Director of the New Orleans Department of Health, Dr Jennifer Avegno and Mayor Latoya Cantrell at a daily press conference. They became the face of the struggle against the virus in the city.Recording this time in our city’s history has felt particularly personal. In late March, my wife and I fell ill with Covid. Both in our late 50s and in good health the odds were in our favor, but we were still scared. New Orleans held its Mardi Gras in late February triggering a virulent outbreak. For a time the city had one of the highest infection and mortality rates in the world. The National Guard had set up a testing center at the University of New Orleans not far from where we live. It was a weird emotional experience waiting in the long line of cars to be tested. What looked like a military encampment had been set up in the parking lot and young guardsmen busied about in bubble suits. For us, it felt like our little world was ending in some sort of B-Movie apocalypse. Thankfully, we never went to the hospital, our primary care doctors treated us remotely, but we had a few dark weeks and it took several months before we felt better.

When I was sick, watching the news made me too anxious. When I finally rejoined the world in early June everything seemed changed.

I started work on our oral history plan by reviewing the local news for the first few months of the pandemic, and reached out to local response personnel, local academics, journalists, and city officials to get a good idea of how the crisis had unfolded to that point and how we might frame our documentary response.

To test the water before the project got into full swing, I interviewed a Catholic priest who had performed Last Rites to dying COVID-19 patients in a local hospital. In some cases, the gentle anointing of oil on the forehead and the comforting words of the prayer was the last human contact they had. In his interview he stressed the importance for him to be a physical presence in people’s lives during this time despite the risk.

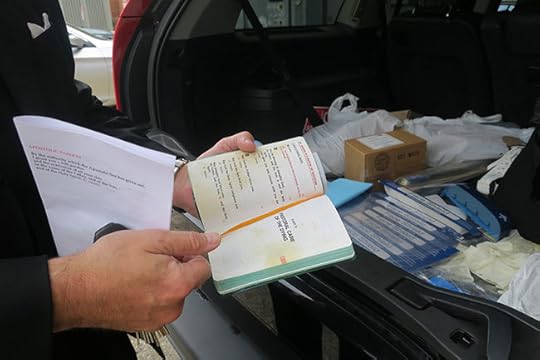

The prayer book of Father Christopher Nalty stained with holy oil. Father Nalty would keep his personal protective equipment and prayer book in the trunk of his car so he would be ready for a call

The prayer book of Father Christopher Nalty stained with holy oil. Father Nalty would keep his personal protective equipment and prayer book in the trunk of his car so he would be ready for a callAs we did in our work in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, we have tried to “imbed” ourselves in response agencies in order to gather narratives. In the case of the case of our Covid project it will be primarily hospitals. Showing up at a work place day after day builds a familiarity and comfort level that leads to greater openness and access. This role as an insider has some pitfalls however. There is a tendency to become party to the internal hierarchy of that organization. It is important to remain somewhat aloof and to work to make sure that you are capturing the perspectives of those not generally given a voice within this hierarchy. In the case of hospitals it is the janitorial staff that cleaned the rooms of Covid patients and the food service workers who brought them their meals.

Stephanie Simon is a mortician with Rhodes Funeral Home in New Orleans. Morticians were important first responders in the crisis faced with body storage issues as families waited on burial with the hope of having funeral service at a later date.

Stephanie Simon is a mortician with Rhodes Funeral Home in New Orleans. Morticians were important first responders in the crisis faced with body storage issues as families waited on burial with the hope of having funeral service at a later date.By July, the initial spike in New Orleans subsided and it proved to be a good time to approach city officials and first responders. Many were exhausted and still frayed from the fight they had been in the past four months. They found comfort, I think, in the reflective nature of oral history, and an emotional release was evident in many of the narratives. Emotion is a critical part of the truth of experience and something fragile and fleeting. Recording this emotional baseline is a critical takeaway of doing crisis oral history and no other documentary technique does it better.

Paramedics were dealing with high infection rates among their ranks combined with an overwhelming workload during the early months of the pandemic. They indicated that sometimes just a little oxygen was needed to save lives. New Orleans EMS Director Dr. Emily Nicholls explains.

Work within the local response agencies will go on for the next two years. We are also are trying to chart the cultural impact of the pandemic and lockdown. From artistic responses, to changes in the deep-rooted funeral traditions in New Orleans, to the impact on the city’s world-renowned restaurants—such a key component of the city’s tourist economy. The implications of this event will be shaping our cultural and political life for a generation.

Featured image courtesy of the author. Prior to the pandemic, artist Josh Wingerter sold his works at a local art market. When the market closed, he began painting the plywood panels on boarded up businesses. In time other artists joined in. Josh created some of the more icon images or the pandemic period in the city.

The post Listen now before we choose to forget appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers