Oxford University Press's Blog, page 124

December 6, 2020

A year of listening to books

The COVID-19 crisis has led me to rethink a lot that I’ve taken for granted. One of the saving graces helping to get me through long days of remote teaching and evenings of doom-scrolling was the opportunity to take long walks. In the mornings, I walked before work, to wake up; in the evenings, I walked to shake off the day’s sitting and to fend off the Zoomfleisch. I walked the streets and alleys, paths and trails of my town, nodding at other walkers and keeping my six-feet away.

Some days I wanted to walk silently, to think something through, to meditate, or to write something in my head. Other days I had an audiobook to listen to. I had upgraded my phone and phone service and invested in some decent earbuds, so I was ready. At first, I didn’t think about it too much. It was a way of keeping my mind occupied while my legs worked. I started with thrillers downloaded through my local library, a genre that provided some extra cardio.

Toward the middle of the summer, I spotted the unabridged audiobook of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in the library’s available books queue. I had read it a couple of times before and seen the film versions, both the 1956 one and the 1984 version (with Richard Burton as O’Brien). I was planning to refer to Newspeak and the novel in fall classes, so I clicked “checkout.”

For the next eleven walking hours, I had the new experience of having a familiar book read to me. It was, to mix a metaphor, eye-opening. It wasn’t just the Simon Prebble’s English accent and Orwell’s Briticisms. Those were fun for me as a linguist, but the audiobook gave me the opportunity to experience something familiar in a whole new way.

Audiobooks are a slower experience than print books or ebooks. By my estimation, audiobooks last twice as long. That leaves more time to reflect while listening, sometimes randomly (I wonder if Victory Gin is a real thing?) and sometimes more critically (Orwell’s sexism and misogyny stand out and the long reading of Emmanuel Goldstein’s The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism does not hold up). Small details stick with me (the glass paperweight, the bugs in the lovers’ bed). When rats appear, I see the foreshadowing of Winston’s fate, and the ubiquitous telescreens bring to mind all the Zoom meetings I’ve been in.

Listening to Nineteen Eighty-Four gave me a new perspective on that book and opened up a new way to read and reread. As I’ve listened to other audiobooks since, I found myself thinking about what the narrator chooses to emphasize. Is there something in their tone that suggests we’ll be seeing more of a character? Does the narrator want you to like the protagonist or not?

Matters of craft stand out in new ways as well. The slower pace allows you to anticipate wording that comes next and you notice things you might otherwise skip over in print: a writer who uses “paws” rather than “hooves” or the number of times someone is referred to as having glasses with square frames.

Listening also sharpens your senses. You have time to smell the Pears Soap or chicory coffee, to taste the meatloaf, to feel the speed of the van on the icy road. And in audiobooks, there is no visual clue that you are at the end of a chapter. In the pause that suddenly arrives, you have a moment to think why it ended on precisely that note.

Now I find myself making a list of books to reread as audiobooks and of new books that I might listen to as well as read. And I find that I am walking more than ever.

Featured image by Joseolgon

The post A year of listening to books appeared first on OUPblog.

December 5, 2020

Unique adaptations allow owls to rule the night

As the only birds with a nocturnal, predatory lifestyle, owls occupy a unique niche in the avian realm. Hunting prey in the dark comes with a number of challenges, and owls have evolved several features that leave them well-suited to this task. Owls uniquely combine traits common among predators, like acute vision and sharp talons, with adaptations for a nocturnal lifestyle, such as enhanced hearing and night vision. Pamela Espíndola-Hernández, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, and her colleagues recently reported the results of a genome-wide scan designed to reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying these adaptations. In addition to confirming the important role of the visual and auditory systems, the study suggests the existence of an unusual adaptation not yet described in birds—a special way of packaging DNA in retinal cells to act as a light-channeling lens—shedding new light on the evolutionary history of this nighttime predator.

The majority of birds have a diurnal lifestyle, meaning they are primarily active during the day. Owls are thought to have diverged from their sister group, which includes mousebirds, woodpeckers, and kingfishers, during the Paleocene, when a radiation of small mammals may have led to an increased availability of nocturnal prey. To take advantage of this nightly feast, owls presumably retained predatory features shared with other raptors like eagles and hawks. At the same time, they developed nocturnal traits that have been observed in other birds that evolved nocturnality independently, such as kiwis and oilbirds. This culminated in a selection of features that make owls uniquely suited to fill the nocturnal predator niche, including retinas adapted for better night vision, asymmetrical ears and facial discs for enhanced hearing, and soft feathers that enable silent flight.

In order to identify the evolutionary forces contributing to this confluence of traits, Espíndola-Hernández and colleagues compared the genomes of 20 bird species, including 11 owls (five of which were newly sequenced for the study) and analyzed the nucleotide substitution rates of individual genes to identify those that experienced positive selection during the evolution of the owl clade.

As predicted, a primary finding of the study was that genes involved in sensory perception showed a genome-wide signal of positive selection. This category included genes involved in acoustic and light perception, photosensitivity, phototransduction, dim-light vision, and the development of the retina and inner ear. Genes involved in circadian rhythms, which regulate the body’s internal clock, also showed evidence of accelerated evolution, as did some genes related to feather production.

While these findings were expected, the analysis revealed another category of genes that was wholly unexpected: 32 genes related to DNA and chromosome packaging exhibited an accelerated substitution rate in the owl lineage. As a potential explanation for this surprising result, the authors point out that the DNA in the retinas of nocturnal mice and primates forms an unusual structure that acts as a sort of collecting lens and increases light detection in the deep layers of the retina. The study’s findings may therefore indicate that owls independently evolved a similar DNA packaging mechanism in the retina that enhances light channeling in photoreceptors, a feature that has not been observed in any bird species to date.

Espíndola-Hernández notes that the validity of these findings rely on the accuracy of the functional gene annotations within the owl lineage, which represents an important challenge for any genomics-based research in non-model organisms. Thus, she and her colleagues hope to verify the existence of these light-channeling DNA structures in the owl eye by studying owl photoreceptor cells. Direct investigations like these are critical, Espíndola-Hernández points out, to validate the findings of computational research.

Genome-wide analysis of 11 owl species reveals that selection on phototransduction, acoustic perception, and DNA packaging genes contributed to the nocturnal, predatory lifestyles of owls. (Credit: Yifan Pei (drawing) and Pamela Espíndola-Hernández. CC-BY via Genome Biology and Evolution)

Genome-wide analysis of 11 owl species reveals that selection on phototransduction, acoustic perception, and DNA packaging genes contributed to the nocturnal, predatory lifestyles of owls. (Credit: Yifan Pei (drawing) and Pamela Espíndola-Hernández. CC-BY via Genome Biology and Evolution)

Feature image by Zdeněk Macháček

The post Unique adaptations allow owls to rule the night appeared first on OUPblog.

December 4, 2020

The changing role of medical librarians in a COVID-19 world

“Health librarians really need to have a broad picture of the health environment to have an impact and connect all the dots,” says Gemma Siemensma, Library Manager at Ballarat Health Services (BHS), Australia. Librarians “need to continue to excel in reference consultations and literature searching to advanced forms of evidence synthesis and critical appraisal,” she adds.

Gemma Siemensma, Library Manager at BHS

Gemma Siemensma, Library Manager at BHSIt’s evident that the role of medical libraries and librarians has changed considerably since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The degree to which this has happened is discussed by Siemensma with Rolf Schafer and Elle Matthews, Library Manager and E-services Librarian, respectively, from St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney.

A typical work day from 8:30am-5pm, Monday to Friday, as in the case of the BHS Library, is no longer the reality. “Our library has been on a rollercoaster ride”, says Siemensma. BHS “were told to close pretty early on and staff moved to working from home. COVID-19 numbers in Australia eased and we reopened briefly for a few weeks with one staff member being onsite whilst others continued to work from home. We then closed again as the second wave of COVID-19 hit Australia. We are now open again with reduced hours and staff doing a mixture of working onsite and from home”. By contrast, the library staff at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney weren’t permitted to work from home due to limitations on the availability of remote access tokens to IT systems and were therefore directed to maintain on-site services to support clinicians and researchers. Additionally, Schafer and Matthews were successfully redeployed to the Emergency Department (ED) and to the Health Information Services (Medical Records), respectively, after “a request for redeployment of non-clinical staff was issued in March 2020 by the Hospital Administration to increase the workforce during the lockdown and support the anticipated surge in COVID-infected patients.”

Elle Matthews, E-services Librarian at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney

Elle Matthews, E-services Librarian at St Vincent’s Hospital SydneySuddenly, medical librarians were faced with new responsibilities to support hospitals. During his four-week redeployment, Schafer set up a Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) safety and compliance audit and audited clinicians in the ED, whereas Matthews’ new responsibilities ranged from running daily reports and data entry of patient details from the COVID-19 pop up testing clinics into the Patient Administration System to contacting patients on a daily basis to verify their identity in order to merge patients’ electronic medical records. Matthews’ redeployment was for an initial period of three months but was later extended to seven months.

Librarians at BHS were also confronted with new responsibilities. Siemensma points out that one of the most exciting roles played during the pandemic was that a Senior Librarian from BHS Library was involved in a local project which included a Therapeutic Goods Administration submission for a locally made ventilator. One of the librarian’s responsibilities was the development of a systematic search strategy for a literature review to support the application, which has subsequently been approved and the company can now make low cost ventilators.

As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, the reading and research habits of medical staff have changed dramatically. “At the outset of the pandemic, many nursing staff were required to upskill and increase their knowledge of managing acutely ill patients, often on mechanical ventilation. The Library developed an electronic reading list of references to support over 100 nurses undertaking the online Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and High Dependency Nursing courses funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. References to books and journal articles were accessible via a hypertext link from a reading list located on the Library homepage. Another initiative of the Library was to compile and maintain a list of recent publications on COVID-19 co-authored by hospital staff. Library staff monitored publication output in the international literature and created an Endnote library with citation details. A link to this bibliography was provided on the Library homepage and promoted via the Hospital’s Daily Bulletin,” says Schafer, adding that online access of the Library resources has increased significantly. The number of visits to the Library home page has gone up by 592.76% year on year, and successful requests for full-text has increased by over 90% this year compared to last year. Likewise, in the BHS Library, services such as literature searches increased, particularly around COVID-19 requested information.

Rolf Schafer, Library Manager at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney

Rolf Schafer, Library Manager at St Vincent’s Hospital SydneyAs the coronavirus pandemic hit, many publishers began curating free content collections to support medical professionals. Opening up COVID-19 research and specific resources (such as infection control) by publishers allowed the BHS Library access content that may have been previously inaccessible. Siemensma mentions that in order to disseminate the available open research related to the virus, the library set up a COVID-19 resources page on their website. This curated information included guidelines, statistics, evidence summaries, research article and literature searches.

Similarly, the library at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney “set up a dedicated widget on our homepage providing links to various COVID-19 resources for the convenience of staff.” Schafer also points out that whilst in the ED, he arranged access to Lippincott Procedures Australia, including the Rapid On-boarding module for COVID-19, and promoted it widely throughout the hospital.

The coronavirus pandemic “has highlighted the importance of access to the evidence base. Conversely it has also highlighted the misinformation that is rampant globally. For me this demonstrates the importance of health libraries and the challenging and rewarding job we get to do day in and day out as an organisation’s only dedicated, secure, permanent, and trustworthy source of authoritative information”, says Siemensma when asked about a lesson from this year. Asked the same question, Schafer highlights that adaptability and being prepared for a whole new way of working is key. “Don’t be afraid to step outside of your comfort zone—you may surprise yourself how well you handle the new role and the various challenges that come along your way,” he concludes.

Gemma Siemensma, Rolf Schafer, and Elle Matthews provided an invaluable insight into the changing role of medical librarians in a COVID-19 world. It cannot be denied that, as Siemensma says, libraries are still in a state of flux with restrictions placed on hospitals. And this may be the case for a while. We are yet to see whether medical librarians and libraries will ever go back to their pre-COVID role, or whether there is a complete “new normal” around the corner for them too.

Feature image by Mika Baumeister. Photos used with permission.

The post The changing role of medical librarians in a COVID-19 world appeared first on OUPblog.

December 3, 2020

Modifying gravity to save cosmology

The unexpectedly rapid local expansion of the Universe could be due to us residing in a large void. However, a void wide and deep enough to explain this discrepancy—often called the “Hubble tension”—is not possible in standard cosmology, which is built on Einstein’s theory of gravity, General Relativity. Now, a team of astronomers have shown how such a void is possible in one of the leading alternative gravity theories called Modified Newtonian Dynamics (or MOND). Using it to develop a dynamical model of the void, they were able to simultaneously fit several key observables of the local Universe. They also showed that the same observables rule out standard cosmology at very high significance.

The new model (dubbed νHDM, with ν pronounced “nu”), is built on the controversial idea of MOND, developed in the early 1980s by Israeli physicist Mordehai Milgrom. Explains co-author Indranil Banik: “one of the biggest unanswered questions in astronomy is why galaxies spin as fast as they do. We can either continue using General Relativity and add dark matter, or we can use just their visible matter but MOND gravity.” In MOND, once the gravity from any object gets down to a certain very low threshold, it declines more gradually with increasing distance, following an inverse distance law instead of the usual inverse square law. MOND has successfully predicted many galaxy rotation curves, highlighting some remarkable correlations with their visible mass. This is unexpected if they mostly consist of invisible dark matter with quite different properties to visible mass. However, MOND has rarely been applied to cosmological scale problems.

The νHDM model used by the authors—originally proposed by Angus (2009)—is in many ways similar to standard cosmology. Neglecting structures, the overall expansion history of the universe is the same in both models, so both can explain the amounts of deuterium and helium produced in the first few minutes after the Big Bang. They should also yield similar fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, which is essentially the flash of light from the Big Bang. This is largely because both models contain the same amount of dark matter, though instead of being rather heavy particles as in the standard approach, the new model assumes dark matter particles are light sterile neutrinos. Their low mass means they would not clump together in galaxies, consistent with the original idea of MOND to explain galaxies with only their visible mass. But on large scales, the dark matter would clump. With the extra gravity of MOND, structures would grow much faster, allowing much wider and deeper voids.

Importantly, there is quite strong evidence that we are indeed living within a large void stretching roughly two billion light years across. This evidence comes from many surveys covering the whole electromagnetic spectrum, from radio to X-rays. Gravity from matter outside the void would pull more than matter inside it, making it look like the Universe is expanding faster than it actually is. This could solve the Hubble tension, a possibility considered in several previous works. They concluded against the idea (Kenworthy et al. 2019), but the new study identifies several flaws with these previous analyses. At stake is the fact that any local void should cause the apparent expansion of the Universe to rapidly accelerate at very recent times. This is indeed observed—the so-called “cosmic acceleration parameter” is about twice the standard expectation, but in line with the new model once the void is included (Camarena & Marra 2020).

Unlike other attempts to solve the Hubble tension, the latest one is unique in using an already existing theory (MOND) developed for a different reason (galaxy rotation curves). The use of dark matter is still required to explain the properties of galaxy clusters, which otherwise do not sit well with MOND. Dark matter also provides an easy way to explain crucial observations like the cosmic microwave background and the expansion rate history. MOND is a theory of gravity, while dark matter is a hypothesis that more matter exists than meets the eye. The ideas could both be right.

A dark matter-MOND hybrid thus appears to be a very promising way to resolve the current crisis in cosmology. Still, more work is required to construct a fully-fledged MOND theory capable of addressing cosmology. The current study argues that such a theory would enhance structure formation to the required extent under a wide range of plausible theoretical assumptions. This needs to be shown explicitly (cue more algebra). Further observations would also help greatly. In particular, the density profile of the outskirts of the void we’re in could hold vital clues to how quickly it has grown, helping to pin down how the sought-after MOND theory must behave.

There is now a very real prospect of obtaining a single theory that works across all astronomical scales, from the tiniest dwarf galaxies up to the largest structures in the Universe and its overall expansion rate, and from a few seconds after the Big Bang until today. Says Pavel Kroupa, the PhD supervisor of Moritz Haslbauer and third author on the study: “Rather than argue whether this theory looks more like MOND or standard cosmology, what we should really do is combine the best elements of both, paying careful attention to all relevant observations.”

Featured image: Illustration of the Universe’s large scale structure. The darker regions are voids, and the bright dots represent galaxies. The arrows show how gravity from surrounding denser regions pulls outwards on galaxies in a void. If we were living in such a void, the Universe would appear to expand faster locally than it does on average. This could explain the Hubble tension. (Original by Zarija Lukic via Technology Review)

The post Modifying gravity to save cosmology appeared first on OUPblog.

December 2, 2020

Etymology gleanings for November 2020

Historians deal with documents or, when no documents have been preserved, with oral tradition, which may or may not be reliable. The earliest epoch did not leave us any documents pertaining to the origin of language. We cannot even agree on what system of signals constitutes language. The “first” words are lost, and only the oldest recorded words have come down to us. Those are late, and the method of reconstructing their past depends on the state of the art and the researcher’s ingenuity. Some “primitive” words we know are simple (bow–wow, hush, buzz); others are short but not very simple (bad, put, big, dud, dude, eat; if, and). The mechanisms of word coining have hardly changed since the beginning of time. Consequently, though words come and go, the earliest products of language creativity may have been supplanted by similar or even identical formations. Yet each word needs an individual approach. The desired near-universal master key, when proposed, always turns out to be an illusion. This is especially true when someone comes up with a list of a limited number of roots from which all words allegedly sprang up or with one language as the source of all others.

The origin of Engl. stir “prison” The Start, a prison in London. (West View of Newgate by George Shepherd 1784-1862, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

The Start, a prison in London. (West View of Newgate by George Shepherd 1784-1862, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)There is not much I can add to what is universally known about the etymology of this word. Let me only say that words for “prison” are often borrowings from foreign languages. Such are both Engl. prison and jail (or gaol as, for example, in Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol). Conversely, many are slang, and their origin is, predictably, obscure. Eric Partridge once remarked that a lot of nonsense had been written about the derivation of stir, but the literature on this word is poor and only two hypotheses on it compete, or rather competed in the past. The earliest citation of stir (1851) in a printed text goes back to Henry Mayhew, whose description of London life has lost none of its value. The word was noticed almost at once. The first item in my database on stir is dated to 1852 (in the indispensable bimonthly Notes and Queries). It soon made its way into all the dictionaries of British slang.

Monosyllabic synonyms for prison are rather numerous: compare jug, nick, can, pen, and the unexpectedly elegant Latin quod. This complicates our search. By an incredible coincidence, one of the Old English words glossed as “prison” was stȳr, a variant of stēor (both with long vowels). Yet the speakers of the oldest Germanic languages had no prisons. Crime was punishable by fines, mutilation, and outlawry. Engl. prison and gaol appeared in the language in the twelfth and the thirteenth century respectively. The New Testament, with its Roman background, often mentions prisons, and Bishop Wulfila, who in the fourth century translated the Bible into Gothic, used karkara (Latin carcer; compare Engl. incarcerate). He could find no native word for such an institution in his language. Old Engl. stēor, which has the root of Modern Engl. steer, meant “steering one toward a certain goal (not gaol!), guidance, discipline, correction; penalty, fine, punishment” and therefore “prison,” but it did not refer to the prototype of our jail. The idea that stir existed in the lingo of the underworld for a thousand years and surfaced only in the twentieth century is hard to accept.

The other derivation looks more realistic. It traces stir to some Romany word for “prison,” such as stariben or stardo. The fact that nearly the same word is known in Spanish lends credence to this etymology. As usual, “proof” is wanting, but etymological propositions can seldom, if ever, be “proved.” We are at best able to assess the degree of the verisimilitude of this or that hypothesis. For the moment, the Romany origin of Engl. stir is the best we have, and some dictionaries have accepted it, with the traditional hedging (perhaps, probably, and so forth). According to Eric Partridge, The Start, The Old Start “Newgate Prison” in London got its name from stir. I was unable to check the date of this name and will be grateful for a comment from an expert on the history of London. Since stir was known in 1851, it must have appeared in the language earlier, but we don’t know how much earlier. In any case, Bampfylde-Moore-Carew, the author of a book of his “Adventures” (1755), did not include it in his sizable description of “the Gipsies (sic) and their language.”

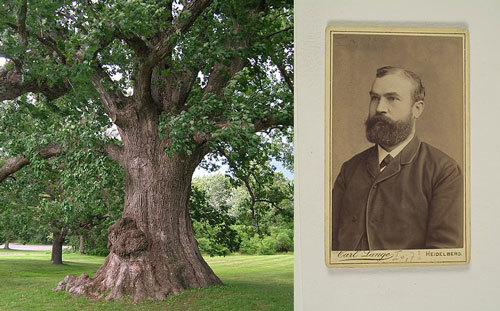

The way from tree to true and trough and the community of sn-words A tree, a symbol of unwavering loyalty. Herman Osthoff, a sturdy German scholar. (White oak tree by Msact, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Osthoff portrait CC-BY-SA 4.0, via Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.)

A tree, a symbol of unwavering loyalty. Herman Osthoff, a sturdy German scholar. (White oak tree by Msact, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Osthoff portrait CC-BY-SA 4.0, via Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg.)The way is devious and may not lead us to the desired answer. The great Indo-European scholar Hermann Osthoff (1847-1909) wrote an article titled “Eiche und Treue” (“The Oak and Loyalty”), in which he attempted to show that the idea underlying the word truth is the immobility of a mighty tree (“tree” = “steady and constant”). Modern etymologists treat this connection without enthusiasm, but its appeal is obvious. The ancient root of tree is dru– “wood” (as in Sanskrit). Trough, an object made of wood, has the same root. I have a dim recollection that I have once discussed the tree-true link but cannot remember when. The same correspondent asked me about sn-words (snow, sneeze, snicker, sniff, snuffle, and snot) designating moist and wet things (snicker does not quite belong here). See the posts for May 1 and May 8, 2019 on sn-. Not improbably, snow also meant “wet and sticky substance.” Yet elsewhere, this word’s cognates occur without s- (this is an example of s-mobile, often referred to in this blog), and, if the “primitive” root began with n-, the association with wetness may be secondary.

On spellingOur correspondent asked me to publish my list of reformed spellings. I don’t have such a list (The Spelling Society does), but I have some ideas. Get rid of the letter q (replace it with kw) and of y, at least in the middle of words. Abolish some mute consonants. (I am sure someone pronounces k-thonic, but this pronunciation is a tribute to academic pedantry. Likewise, quite a few British specialists say my-thology and my-thic, because the Greek vowel in this word is long. Knock and gnaw will do well without k- and g-, and acquaintance will do equally well in the form akwaintens. Rough will lose none of its roughness if spelled as ruf ~ ruff (compare rub and gruff). Many double consonants are also a nuisance. Think of simetri instead of symmetry (compare cemetery). But my wants are few: I am ready to accept the mildest version of the reform, only to see the stone rolling. Yet for now I’d leave a few of the worst high-frequency offenders (you, have, and give, among them) intact.

Odds and ends A bazaar, bizarre and busy. (The Egyptian or drug bazaar at Constantinople. Watercolour by J. F. Lewis. CC-BY-4.0 via the Wellcome Collection.)

A bazaar, bizarre and busy. (The Egyptian or drug bazaar at Constantinople. Watercolour by J. F. Lewis. CC-BY-4.0 via the Wellcome Collection.)Eeny-meeny. I’ll be ready to discuss it with my opponent after he has read the entry on this “word” in my etymological dictionary.

Bazaar among the b-z words. It would be nice to explain bazaar as a busy place with a lot of bizarre things on display and everybody abuzz. But I am afraid of losing my way in the Oriental morass; too many languages are involved in the history of bazaar, and it seems that s, rather than z, was in the middle of the ancient form. Perhaps specialists in that branch of linguistics will help us here.

Greater royalist than the king. Dismal phrases like to only come once are now ubiquitous, but watch the heroic splitter from The Washington Post: “Amy R now… calling to not to follow the will of voters or making baseless allegations of fraud….” The writer also rather inelegantly mixes infinitives and gerunds. (The moral: don’t split in haste and reread what you write.)

Feature image in the public domain from pxfuel.

The post Etymology gleanings for November 2020 appeared first on OUPblog.

Social studies: learning the past to influence the future

The events of 2020 have shown individuals living in the United States that race is ever-present in our lives. Consider the mass protests that have occurred all over the US—and spread around the world—following the death of George Floyd, and the economic and medical inequalities experienced by communities of color revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic. These historic events contradict the New York Times headline I recalled following the election of Barack Obama as President in 2008: “Racial Barrier Falls in Decisive Victory.” Yet, from observing student teachers in educational contexts this year, many students want to discuss race’s effect on their lives. Spaces for these conversations, however, are not usually available. We must transform how history is taught and learned in our K-12 classrooms since we do not see the implications of our actions until well into the future.

Learning history is complex; it requires an individual to be a critical thinker, develop different interpretations of history, and engage in analytical writing. I encourage these skills in my undergraduates when we discuss the past. However, within the US’ K-12 system, social studies have been relegated to the sidelines as education policymakers and administrators have focused on math and science since the start of the 21st century. I experienced this sidelining of learning the past as a secondary social studies teacher. School administrators and colleagues told me numerous times that learning social studies did not matter. Even though the events of 2020 have brought learning about history to the forefront, it is still common for many educational contexts to ignore race.

One possible cause for the lack of a thorough understanding of race in US history has been the social studies curriculum. The social studies curriculum has had a long and contentious history with “controversial” topics such as race. It has been a tug-of-war between liberal and conservative politicians and policymakers since the formation of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) in 1920. NCSS advocates Social Studies as a subject that educates students for life-long learning and informed civic action. Moreover, each state is responsible for the development of standards that guide the instruction of the past. This implies that learning the past will be considerably different. Consider a student moving from New York to Texas; that student will learn about the past in a considerably different way due to geography, demographics, and local histories.

Another possible cause is teacher education programs. In my program, I learned the importance of writing the perfect lesson plan, developing detailed assessments, and building strong classroom management skills. I was told to keep politics out of my instruction. So, at the beginning of my K-12 teaching career, I deliberately ignored the topic of race. As a result, I found the students unresponsive to my teaching. It was not until my fourth year of teaching when students started asking questions about race. Those subsequent conversations changed my pedagogy towards including conversations on race in different units.

Towards the latter half of my career, I used primary sources to dig into US history origins. Students dissected the journals written by English, Dutch, and Spanish “traders.” Students learned how race was the main reason for the human trafficking of Africans to North America during the 16th and 17th centuries. I recall their questions: Why did Europeans target Africa? Why were thousands upon thousands of Africans transported against their will across an ocean?

I also used eyewitness accounts. I recalled a unit on Reconstruction. There was minimal mention of the Buffalo Soldiers who fought Indigenous people following the US Civil War. I introduced diaries written by different soldiers to the students. I also remember their questions: Is this what Bob Marley talked about in his song? Why didn’t I learn this before? Why is it a paradox that these individuals fought valiantly for a country which separated them according to their skin color?

As a teacher educator, I introduce race from the start. Future educators read research articles, speeches, and case studies that situate race within different education facets. We connect race to other topics, such as gender, economics, climate change, and language. I encourage them to reflect throughout the semester, a needed practice in developing their pedagogies.

These are initial suggestions. Encouraging students to ask questions is a valuable academic and life skill, resisting the need to accept others’ narratives. Learning about race in the past is necessary for the students currently in our classrooms. They need opportunities to learn how race was part of the development of the US and how it continues to be present. What we teach them today will have an impact on our society in the future. I leave the reader with this thought: imagine how impactful these conversations on race will be on our students’ future political participation.

Featured image by NeONBRAND

The post Social studies: learning the past to influence the future appeared first on OUPblog.

December 1, 2020

Five overlooked Beethoven gems

Beethoven wrote an enormous quantity of music: nine symphonies, some fifty sonatas, seven concertos, sixteen string quartets, more than a hundred songs… the list goes on and on. It is almost inevitable that certain of these works have been relatively neglected by performers and the listening public alike. Here are a few overlooked gems.

1. Finale of Der glorreiche Augenblick (“The Glorious Moment”), op. 136This cantata, written to celebrate the heads of Europe who had gathered for the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, is one of those works that even many Beethoven enthusiasts love to hate, and it’s easy to see why. The text (by an amateur poet) is pompous and the music is largely forgettable. But the brief finale, in praise of Vienna itself, stands apart. A women’s chorus sings the city’s praises, followed by a children’s chorus, and then a soldiers’ chorus, with the last of these accompanied by bass drum, cymbals, and triangle in a way that anticipates the “Turkish March” section of the Ninth Symphony’s finale. It all concludes with a rousing fugue, and it’s easy to imagine that Beethoven had fun writing this movement.

Listen here.

(Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Hilary Davan Wetton, cond.)

2. Piano Sonata in F, op. 54While it’s hard to call any of the 32 piano sonatas “overlooked,” this two-movement work doesn’t get nearly as much attention as those with catchy nicknames (“Moonlight,” “Tempest,” “Appassionata,” etc.). In its own understated way, however, op. 54 is quite extraordinary. The first movement goes back and forth between an innocent minuet-like melody and a pounding triplet theme: the two seem to have nothing in common, yet Beethoven somehow manages to combine them in the end. The second movement is a rollicking perpetuum mobile with all kinds of strange harmonic twists and syncopations. And what started out very fast gets even faster at the end.

Listen here.

(Maurizio Pollini, piano)

3) Polonaise for piano, op. 89Beethoven got there well before Chopin, but this polonaise from 1815 has never gained much traction among pianists. It’s a remarkable work, though, starting with a breathtaking virtuosic flourish. The more stately main theme incorporates this Polish national dance’s characteristic syncopated rhythm. The key-signatures change repeatedly in the middle of the piece as it takes all kinds of surprising harmonic turns. Nor was this Beethoven’s first polonaise: he had already written one for wind band five years earlier. It’s a delightful little piece even if doesn’t quite rise to the level of a gem.

Listen here.

(Mikhail Pletnev, piano)

4) “L’amante impaziente” (“The Impatient Lover”), op. 82, nos. 3 and 4, for voice and pianoThe text, by the celebrated Italian poet Pietro Metastasio, is a lover’s lament: Where is my beloved? Why does he make me wait? Does he mean to make me suffer? Every hour seems like a day to me, and so on. Beethoven set this text to music in two completely different ways. The first setting marked “Arietta buffa” (“Comic arietta”), is bright, fast, and bouncy: one has the feeling that the beloved will be in deep trouble when he finally does show up. The second, marked “Arietta assai seriosa” (“Very serious arietta”) could not be more different. It draws on every cliché in the repertory of musical laments: minor mode, slow tempo, grinding dissonances, and a hesitant melodic line full of drooping intervals that mimic a lover’s sighs. It’s all done to such an extreme, in fact, that we can hear this setting either as a lament or as a parody of a lament, overdone to the point of farce. The key word here is “seriosa,” which in Italian can mean either “extremely serious” or “overly serious,” as in: serious to the point of absurdity.

(Joyce DiDonato, mezzo-soprano; David Zobel, piano)

5) Violin Concerto, op. 61a, arranged for piano and orchestraWhy listen to an arrangement when you can have the original? Because Beethoven himself made this one, and he knew how to show off his talents as a pianist, especially in cadenzas, that moment in each movement of a concerto when the orchestra drops out and the soloist improvises alone. Or not: in the written-out cadenza of this particular first movement, Beethoven included a major part for the solo percussionist. The idea of any other member of the orchestra intruding into the soloist’s moment is strange enough, but the percussionist of all people? Bizarre as it may seem at first, it all makes sense in the end, because we realize, in retrospect, that the entire work had in fact opened with a brief percussion solo. A few orchestras have begun to incorporate this feature of the cadenza into their performances of the original violin version of this work; more should do so.

Listen here.

(Daniel Barenboim, pianist and cond.; English Chamber Orchestra)

For the full performances of these pieces and five additional Beethoven masterpieces, listen to the full playlist here, and discover the full context of these songs with Beethoven: Variations on a Life.

The post Five overlooked Beethoven gems appeared first on OUPblog.

November 28, 2020

How to call for the police Crisis Intervention Team

Chapter 7 of Family Guide to Mental Illness and the Law is titled “When Police Are Called to Help” and deals with two types of circumstances: those involving people with mental illness as victims of crime and those in which families seek help from police during a mental health crisis. This blog post contains one small excerpt from that chapter.

When you call 911 for assistance with someone whose mental health symptoms are out of control:

1. Ask for the Crisis Intervention TeamSpecifically ask for Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) officers with mental health training. Tell the dispatcher that the person you are calling about has a diagnosed mental illness and is experiencing a mental health crisis and explain what that illness is.

2. Help prepare the police officers for the sceneThen after setting that foundation help prepare the officers for the scene by giving the 911 operator all of the details about the current behavior.

Does this person have a weapon?Is the person athletic or trained in martial arts?Give facts about their size. At this moment, is the person delusional, depressed, hallucinating, manic, spastic, or agitated?Provide very quick context for any statements that the person is making.3. Flag down the police officers upon arrivalTo help make the police encounter as safe as possible for everyone present, you or someone else should go outside to flag down the police and tell them where the building entrances are and where the event is happening inside the building.

4. Give the on-scene police officers an updateEven though you told everything to the dispatcher, give a quick descriptive update to the on-scene police as soon as you can. For example:

“My bipolar thirty-year-old son, Steve, threw me down the stairs. I don’t know if he took his medicine. He is shaking all over and won’t talk to any of us.”“My twenty-five-year-old sister, Kay, is delusional. She is pulling everything off of the shelves and throwing it on the floor. I ran next door. Nobody else is in the house with her.”“My husband, Ted, is depressed. He locked himself in the upstairs bathroom and is crying about an old business failure. He keeps saying angry things about Bob, but Bob is long gone. There is no reason to worry about Bob.”5. Stay out of the wayOnce the officers begin to work the scene, stay out of the way! Do not talk unless an officer asks you a question or calls on you to say something but stay close enough that the officers can communicate with you if they need to. The CIT officers know how to interact with people suffering from specific mental disturbances; they do not need you to translate for them. All police officers are trained to stabilize situations, so even if there is not a CIT officer present you should not interfere once you’ve oriented the officers to the situation.

Featured image by Davey Heuser

The post How to call for the police Crisis Intervention Team appeared first on OUPblog.

November 27, 2020

Bruce Lee and the invention of martial arts

Bruce Lee was born in San Francisco on 27 November 1940, while his parents toured the US with a Hong Kong theatre company. As a baby, he featured in Esther Eng’s Golden Gate Girl. He then went on to become a major child star in Hong Kong. As an adult, he worked in US TV and film, before gaining international fame via three Hong Kong martial arts films and one US-HK co-production, Enter the Dragon. He died from cerebral oedema on 20 July 1973, at almost exactly the moment Enter the Dragon was released around the world.

Had he lived, Lee would have been 80 on 27 November 2020. This anniversary will be marked by countless people and innumerable institutions all over the world, from China to Russia to the USA, and almost everywhere in between. This is because, in the space of a few episodes of a couple of US TV series and four martial arts films, Bruce Lee changed global popular culture forever.

This is not the place to try to detail his life or the significance of his impact. We now have an authoritative biography: Matt Polly’s Bruce Lee, A Life (2018). Numerous documentaries, such as How Bruce Lee Changed the World, have clarified the extent to which he has functioned as a muse and inspiration in all kinds of activities, from art to music, sport to political activism. Countless scholarly works have engaged with his contributions to martial arts, film fight choreography, and ethnic identity politics. I too have weighed in on many of these debates with not one but two academic monographs on the cultural significance of his interventions.

So, what more is there to say about or learn from Bruce Lee?

In my latest research. I took the decision to try to look past him, to try to displace him from centre-stage. In doing so, it became clear that before Bruce Lee, Western media certainly had some ideas about what we now call martial arts. The complex relationship between the USA and Japan led to the frequent appearance, from the 1950s, of judo, jujutsu, and karate in Hollywood films. Britain too had an understanding of the spectacular potentials of Japanese approaches to combat, as is registered in the fight scenes of influential TV shows of the 1960s, such as The Avengers.

In fact, in one respect it is possible to say that representations of East Asian martial arts were flourishing in Western media and popular culture before Bruce Lee arrived. But, in another (more subtle but profound) respect, it is entirely incorrect to say this. This is because, prior to Bruce Lee, there was no overarching or synthesizing concept of “martial arts” in the Western lexicon. People may have practiced judo, jujutsu, karate, or other activities but such practices were yet to be grouped under the organising umbrella term “martial arts.”

In fact, the first appearances of the term “martial arts” in anglophone film are tied to Bruce Lee. In 1972’s Way of the Dragon (AKA Return of the Dragon in the USA), we hear Lee proudly proclaim, “and every day I practice martial arts!” Shortly after, the movie posters for 1973’s Enter the Dragon hail it as “the first American produced martial arts spectacular.” Within the film’s dialogue, the British character, Mr Braithwaite, speaks of “a tournament of martial arts.”

Before these occurrences, “martial arts” was a rare term, used mainly by specialists as one possible translation of the Japanese term bugei—which literally means “warrior art.” But after its appearance in and around these two films, it caught on like wildfire.

It would be incorrect to say that Bruce Lee invented the term. But before he popularised it, few were using it. Indeed, it was not until after its filmic appearance that even specialist scholars such as Donn Draeger began to use the term “martial arts” as an organising term, for example in the titles of books.

It was Bruce Lee who effectively introduced the term “martial arts” into the Western lexicon. This may not seem hugely significant. But what it also means is that he sowed the seeds of a new identity: people could henceforth identify as “martial artists.” Ultimately then, although it is true that before Bruce Lee people were practicing what we now call “martial arts,” it was only after Bruce Lee—and perhaps only because of him—that the very entity “martial arts” and the identity “martial artist” came into social and cultural existence.

Feature image by Charlein Gracia

The post Bruce Lee and the invention of martial arts appeared first on OUPblog.

November 26, 2020

How the #EndSARS protest movement reawakened Nigeria’s youth

In early October 2020, a youth protest alleged police brutality with the hashtag #EndSARS suddenly took many Nigerian cities by storm. The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was set up in 1992 as a heavily armed elite police force unit to tackle violent crime including armed robbery, kidnapping, and carjacking.

Human Rights groups, including Amnesty International, have for many years documented alleged SARS abuses of civilians including extortion, rape, and extrajudicial killings. Over the years the police have repeatedly denied the allegations. The present #EndSARS protests started after a video surfaced that showed a SARS officer allegedly shooting a man in Delta State before driving off. This video set off peaceful protests across the country. However, unlike previous protests with clearly identifiable leadership structure which was susceptible to being arrested and charged to court by the government, this protest movement decidedly insisted on not having a central leadership. Rather, using social media and propelled mainly by young people, cutting across class lines, the protests have been largely peaceful and very coordinated.

The initial demands made by the protesters included the disbanding of SARS; release of incarcerated youth; justice for deceased victims of police brutality and appropriate compensation for their families; setting up of an independent body to oversee the investigation and prosecution of all reports of police misconduct within ten days; and the psychological evaluation and retraining of all disbanded SARS officers.

In the intervening days after the protests began, the Nigerian government announced that it was disbanding SARS. The government also pledged to investigate the allegations of misconduct against police officers. However, the nationwide peaceful protests continued unabated. The reason for this could be because, several times since 2017, the government had announced the dissolution of SARS in reaction to public outcry over incidents of brutality, only for the unit to later continue. Therefore, the protesters were very skeptical that the government was going to disband the unit this time around.

Another possible explanation for the protest continuing on could be that, given that protesters already have other underlying issues and grouses against the government and having now received national attention over the #EndSARS protests, the protesters may have wanted to highlight those issues too by prolonging the protests. Significant among these underlying issues is the current rate of youth unemployment and the sense of hopelessness that this has engendered amongst young people. This is particularly the case among recent university graduates who are having difficulty finding gainful employment. According to Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics, in the second quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate among young people (those 15 to 34 years old) stood at 34.9% as opposed to 27.1% for the general population. There is also a general perception that President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration has not done enough to improve the economy. This has further reinforced the perception of indifference and insensitivity on the part of Buhari’s government to the plight of Nigerians. Nigeria’s economy has been in recession since the middle of 2019, a situation that has been made worse by the decline in oil prices in late 2019 and early 2020, and further exacerbated by the lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

What began as a relatively peaceful nation-wide protest two weeks earlier took a decisive turn for the worse due to what happened at the Lekki Toll Gate in Lagos on 20 October 2020. At noon, the Governor of Lagos State, Babajide Sanwo-Olu, announced a 24-hour curfew that was to begin at 4pm of that same day. At about 7pm, according to eyewitness accounts, protesters who had ignored the curfew and were gathered around the Lekki Toll Gage noticed that the lights and the CCTV cameras around the toll gate were suddenly turned off. The protesters started singing the national anthem and waving the Nigerian flag, in the hopes that nothing bad will happen to them. But a few minutes later, Nigerian soldiers allegedly emerged from gun trucks and started shooting live ammunition on the peaceful protesters. Amnesty International has since reported that at least 12 protesters were killed in that incident and many were injured. This incident generated widespread condemnation, including from the European Union, the African Union, the US State Department, and the United Kingdom.

On 22 October 2020, after a few days of silence, President Muhammadu Buhari addressed the nation and called for the protesters to leave the streets because their demands had been met by the government. But he made no mention of the Lekki Toll Gate shootings and this further angered the protesters. From that point on, what had until then been relatively peaceful protests took a turn for the worse with the burning of public buildings including police stations and banks. Many government warehouses suspected to be used in storing food items originally meant for distribution to the public to alleviate the hardships of the coronavirus pandemic were broken into and looted. Also, two jailhouses in Benin City, the capital of Edo State, were broken into and over 2,000 prisoners were set free.

Arguably, what started as the #EndSARS protests with the express objective of ending police brutality has now been broadened to include other underlying issues such as economic hardship, maladministration, and respect for the rule of law. Furthermore, it is now clear that no presidential address or pledges will satisfy the hunger and expectations of the reawakened youth. This is because the youth appear to be tired of empty speeches and promises. Poverty and economic hardship, it appears, has been weaponized and the youth, who have felt entrapped in it, seem to now have broken free.

Feature image by Tobi Oshinnaike

The post How the #EndSARS protest movement reawakened Nigeria’s youth appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers