Oxford University Press's Blog, page 94

October 15, 2021

New pathways through later life: redesigning later life work and retirement

In March of 2020, for many Americans and older workers especially, what it meant to go to work changed in an instant. As some workers moved their offices into their homes, others had to go to work and face significant risks to their health each day. Older Americans faced more significant health risks than younger adults, leaving many feeling they had to walk away from work temporarily or permanently, a tradeoff of protecting their health despite a financial need to work. Others chose to enter retirement earlier than anticipated without a clear plan for this new phase of their lives. Given that older workers who lose their jobs face significantly longer periods of unemployment before being re-employed if they desire to work, older workers are likely to lead the way in reshaping what our post-COVID-19 work lifestyles look like.

It will be years before we can look back on the pandemic and fully evaluate the ways that our work lives changed in March 2020. However, the Great Recession that rocked the world during the last few months of 2007 set the stage for how we are defining work and retirement pathways today. For example, the gig economy became a way that everyday people could work without the structure of a typical job, and freedom to choose when and how much to work. It also led to accelerated declines in retirement savings, leaving more individuals without the means to leave work permanently despite reaching traditional retirement ages. How did these and other structural changes shape work pathways in later career stages?

My colleagues and I identified the most prominent work and retirement patterns from 2008 to 2014 among US older workers who left full-time jobs in 2008. Our research showed:

More than half (58%) of people who left full-time work in 2008 returned to work for some period of time.9% transitioned to part-time work only to return to a less intense full-time job and remain employed full-time for a number of years.10% transitioned to part-time work and continued to decrease their work engagement over time until eventually leaving work.However, most individuals identified themselves as retired but continued to work in some capacity.14% transitioned to jobs that were less than 20 hours a week on average and remained half-time employees for an extended period,25% transitioned to half time work and decreased employment hours with each passing year until they fully phased out of the work force.Although it is not known whether these post-Great Recession work patterns will persist in a post-COVID-19 world, there is good reason to expect that most older workers will remain engaged in paid work in some way for many years after traditional retirement ages. In fact, older workers report a preference for transitioning to less intensive paid work before retiring rather than a sudden departure. The problem is that we haven’t developed a clear infrastructure for these kinds of work transitions, so older workers have had to piece together post-retirement employment opportunities on their own. Although there are more options than there used to be, most older workers are unable to phase out of their full-time jobs, and, part-time work rarely includes much needed work benefits like health insurance and matching contributions from employers in retirement savings accounts. Older workers also face the challenge of having a higher likelihood of facing family care needs, and many employers do not offer jobs that provide flexibility for workers to carry out their jobs while also caring for their loved ones.

Although a post-COVID-19 world may push employers to take a new look at career models that include part-time work and flexible work options that allow older workers to stay employed, we need more intentional federal policies that incentivize employers to create non-full-time work options that support the career pathways. For example, a new optional federal retirement savings program could be created for non-full-time workers, and optional early access to Medicare could be provided for part-time workers aged 50+. Such programs may lead to new kinds of work lifestyles that are not only in line with the preferences and needs of older workers, but also among those in other phases of life who need or prefer non-full-time work career paths that allow them to obtain benefits, potential for upward mobility, and meaningful and challenging work.

October is National Retirement Security Month, a time to re-evaluate what retirement means in a post-pandemic world. Across the globe, the average age of the population is increasing. With a decrease in younger, working aged individuals in the US, delaying retirement as a means to retain older workers’ talents will become increasingly critical. Cultivating meaningful, alternative forms of work and retirement pathways has potential to ensure that older workers are valued as important ingredients in a vibrant economy and culture. As we transition to a post-pandemic society, now is the time to rethink the structures that differentiate work and retirement periods so that we can be more inclusive and more flexible in addressing the needs and preferences of all workers.

October 14, 2021

How can we help Afghan refugees?

The outpouring of support for Afghan refugees since the fall of the Taliban a few weeks ago is laudable. As the author of two books on our obligations to refugees, many people have been asking me about how we should respond to this crisis and what we can hope for Afghan refugees. There’s both a lot we in the United States can do and a lot we should be worried about. Let me explain.

What can we do? The most obvious way to help is by resettling refugees—this refers to the process of vetting refugees, transporting them to the US, providing them with a legal status that allows them to work and receive benefits when necessary and connects them with some of the many volunteer-run NGOs and aid organizations that will help them settle into their new lives in the US. With this current outpouring of support that is based in the realization of the moral responsibility that the US has to Afghans, especially those connected to helping US service people, there is more support than ever for robust resettlement of Afghan refugees into the US.

Though there is promise and potential to help Afghan refugees, there is also much to worry about. Take resettlement. Though it represents the best hope for many, it is highly unlikely that we will resettle nearly enough refugees to make a significant difference. A quick glance at the numbers in the wealthiest countries makes this clear: Canada and the UK have promised to take in 20,000 refugees, Australia 3,000, and the US is aiming to resettle 65,000 refugees this year. Though this level of resettlement is significant, it is a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of thousands of people fleeing Afghanistan and the millions of Afghans who left before the Taliban take over. Many of those displaced won’t even be recognized as legitimate refugees who might be entitled to resettlement. Other countries, like Austria and Switzerland, have made it clear that they will not take in any refugees, and it’s possible other EU countries will follow.

If history is any indication, a likely outcome is that once attention turns away from Afghanistan and towards domestic challenges or other global crises, Afghan refugees will likely find themselves lingering in one of a few “temporary” settings. They may find themselves in refugee camps run by the UN near Afghanistan. Iran, for example, currently hosting 3.5 million Afghans, has set up tents near the border but has made it clear that they plan to repatriate Afghans “once conditions improve.” Though refugee camps were always intended to be temporary, refugees are likely to remain there for years, possibly decades, with no real sense of what permanent, durable solutions for them might be.

Another option is moving to urban or peri-urban places without the direct help of the international community. Some Afghans may choose to make their way to cities in Pakistan, for example, where they may have relatives and feel like they could make a living working informally. Many refugees in situations like this feel that they are able to preserve their autonomy and remain, to some extent, in control of their lives. But the disadvantages are dire: work will be precarious and often not enough to sustain them; housing undependable and inadequate; and they will have to live with profound physical insecurity in their day to day lives. Like refugees living in camps, they will have to endure the uncertainty of living in the limbo of not being able to return to their homes and not being allowed to settle permanently elsewhere. Both groups will struggle to meet their basic needs.

Still others will reject both options and choose instead to go directly to a country where they believe they will have a chance to start over. They know that if they get to Italy or Greece, for example, they can make their way inland and claim asylum in a country that will hopefully recognize them as legitimate refugees and allow them to resettle legally and eventually bring over their families. This is precisely what many countries in the European Union are afraid of. Emanual Macron, the President of France, was clear about this when he said shortly after the fall of Kabul that Europe must “protect itself from significant waves of illegal migrants.”

None of these options for the many refugees who are not resettled are adequate. Most people will easily recognize this. What is often ignored is the fact that insofar as the US and its allies are largely responsible for the situation that caused the refugees to flee, we are also responsible for these refugees who find themselves living in these limbo states for years on end, suffering profound material and physical insecurity. This responsibility is not lessened by the fact that we are resettling some refugees. The US and its allies created the situation that Afghans now find themselves in: the invasion of Afghanistan, the failure to put in place a non-corrupt government that Afghans genuinely trusted and believed in, and the failure to withdraw in a way that allowed for stability. Even if you believe that the US was acting with good intentions and trying to do something positive, we remain responsible for the outcome and the refugees who now realize that their home country is no longer a safe place for them to live and who are unlikely to find a new country to call home.

What can be done? This is always the most challenging question. We need to be open to resettling many more refugees that we’re used to and adequately fund the organizations that help to integrate and support refugees. We need to also work with the international community to resettle large numbers of refugees elsewhere, in countries that have the resources to resettle refugees but haven’t traditionally done so. We need to work with governments in the region to encourage and support them in integrating refugees by allowing them, for example, to work, and not isolating them in camps where they can’t meet their basic needs or neglecting them entirely as they struggle to survive in urban centers. For those refugees determined to make their way to Europe and elsewhere, they need safe routes, humanitarian visas, and other programs that don’t force people risk their lives in order to claim asylum.

This is a tall order, but it seems that for many in the US and around the world, the events that we’re seeing unfold make clear that we have a moral obligation to Afghan refugees that goes very deep.

When the headlines become less dramatic and other events capture our attention, it’s crucial to remember that Afghan refugees will need help for a long time to come. That we can help is the good news. That we’re unlikely to help in the ways that Afghan and other refugees genuinely need us to is what we should be worried about.

October 13, 2021

An etymological meltdown: “thaw,” “dew,” and “icicles”

The last two posts were devoted to ice and snow. “The ground was covered with frost and snow, and the two little kittens had nowhere to go.” Perhaps you remember the poem about two little kittens which one stormy night began to quarrel and then to fight: they had not yet learned the virtue of caring and sharing. It was written by Jane Taylor (1783-1824), who was also the author of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star.” The latter poem is an object of an amusing parody in Alice in Wonderland. (“Twinkle, twinkle, Little Bat,” with an allusion to a professor at Oxford, nicknamed The Bat.) The kittens’ quarrel had a happy end, and so will my short series. Consider an old rime: “First it blew, / Then it snew, / Then it thew.”

A bit more is known about the origin of the words thaw and dew than about ice and snow. They are less impenetrable than those two, but they also contain riddles. Though both thaw and dew have some connection with water, the words don’t seem to be related, because one begins with th and the other with d. In searching for cognates, an etymologist should pay equal attention to vowels and consonants. Strangely, in German, both thaw and dew are Tau, that is, the words, obviously cognate with English thaw and dew, begin with the same consonant. This is unexpected. Compare the usual correspondences: English three ~ German drei, English dry ~ German trocken. English thaw should have had a German cognate beginning with a d! And the word we need exists. It is German (ver)dauen, but it means “to digest.” This is where the game begins.

Thaw is welcome—in both nature and politics.

Thaw is welcome—in both nature and politics.Semantic bridges are often easy to build: given enough intermediate links, almost any two concepts may begin to look compatible. If we agree that digest means approximately the same as liquefy or dissolve, then “melt” will emerge as an acceptable bridge between “digest” and “thaw.” Swedish smälta, for instance, means both “to melt” and “to digest.” Old Icelandic melta, an obvious cognate of English melt, also means “to digest” (as usual, we’ll disregard the alternation m ~ sm and ascribe it to the existence of the inscrutable s-mobile). The common denominator is “to make soft” (as in Latin mollis “soft”— compare English mollify—or “dissolve”). Regular cognates of thaw are many: Russian taiat (verb) and similar verbs in Celtic and Greek are among them. Thus, we are left with an irregular German word Tau “thaw,” allegedly influenced by the other Tau “dew.”

A true analogue of some semantic bridges.

A true analogue of some semantic bridges.(Image by Backroad Packers via Unsplash.)

Not the whole history of dew in Germanic is complicated. (Incidentally, dew in English mildew is the same word.) Scandinavian has regular cognates: Icelandic dögg, Norwegian dogg, Swedish dagg ~ dugg, Danish dug, etc. The origin of final g in the Scandinavian languages need not bother us: it has been accounted for. All the rest is murky: German Dampf “steam” may be related (I am not citing English damp, because it was borrowed from Low German; Dutch damp still means “vapor, steam, smoke”). The main trouble is the merger of the German words for “thaw’” and “dew.” Not improbably, the confusion between such words is old. There was, apparently, an ancient root that meant “to rise in a cloud as dust, vapor, or smoke” and related, among many other things, to the notion of breath. Russian dukh “spirit” and English fume (the latter from Latin via French) belong here; d- and f- in the words cited above go back to Indo-European dh. The confusion in German (Tau “dew” and Tau “thaw”) may be part of that larger picture, as suggested by the Swiss researcher Wilhelm Oehl, who, while studying word origins, cast a very broad net but published his works almost only in the annual Anthropos and is therefore little remembered by modern etymologists. Likewise, Viktor Levitsky, the author of an etymological dictionary of the Germanic languages (2010), noted the proximity between the root designating “to flow” and “to move fast.” All such facts are thought-provoking, as the saying goes, but do not explain the merger of the two words (for “thaw” and “dew”) in German.

This is when the dew point is due.

This is when the dew point is due.(Image by Aaron Burden via Unsplash.)

(I cannot refrain from an irrelevant comment. In British English, due and dew are usually pronounced as the first syllable of jury, and in this blog, I have once mentioned my puzzlement on being advised by a knowledgeable person to join a certain learned society: for joining it, I only had—or so I heard the recommendation—to pay my Jews. On the other hand, in American English, due and dew are homophones of do, and I regularly receive emails from my students asking me when the papers are do, even though everything is written in the syllabus. Those letter writers also tend to spell professor with two f’s and one s.)

For dessert, I’ll say something about icicles. You may remember that in the post on ice, I wrote that the word icicle consists of two components. The first is obviously ice, while the second is related to Icelandic jökull “glacier.” But both ice, from Germanic īs, and –ic(le) ~ jök(ull) are said to be related to the same Scandinavian word meaning “icicle; ice floe.” Icicle emerged as a tautological compound meaning “floe-floe” or “ice-ice,” or some other long word, whose first element means the same as the second one (compare pathway and sledgehammer). And indeed, Old English gicel did mean “ice,” a fact well-known but seldom discussed in this context. Long ago, some naïve people believed that in icicle, –icle is a mysterious Latin suffix. Today we know better. Perhaps, while reading this post, you remembered popsicle. It is an invented word. Whatever pop means in it, the end of this noun took its inspiration from icicle.

The truly amazing thing is the multitude of words coined by people for “icicle.” In 1961, Erik Roth, an eminent Swedish scholar, brought out a book (163 pages!) on this multitude. I’ll skip the German and the Scandinavian material, because British English also presents a motley picture. (The American Dictionary of Regional English probably has more words of this type.) To begin with, dialectal ickle is not dead. Among the rather numerous phonetic variants of this word, some, like eckle and aigle, are easily recognizable. One or two have even made their way into thick dictionaries. In the Middle English compound ise-yokel, s was assimilated to sh before y (compare the pronunciation of phrases like as you like it), is-shockle emerged, shockle “icicle” pried itself loose from the compound, and a new word was born. This is perhaps the best-known northern form of them all, but tankle exists too, along with icittle, ishicle, icelick, and so forth. In the south, we encounter clinker-bell (-bill) and ice-candle, the best of them all. An icicle looks like a dagger, another image that occurred to many (compare Scottish ice–dirk). A nice word is aqua–bob. Thus, shockle, shoggle, shackle, tankle, tanklel, –candle, ice-lick, eckle, and even ice-bug. Take your pick and prepare for the coming winter.

Ice dagger. Beware: it is sharp.

Ice dagger. Beware: it is sharp.(Image by Frederick Dennstedt via Flickr.)

Featured image by Xena*best friend* via Flickr

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected children’s mental health?

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a year and a half fraught with unpredictability and change. Change and unpredictability can be stressful for anyone, but for children, change and disruption of routine is especially stressful. Schools across the United States were abruptly shut down, moving many children to hybrid or distance learning and moving working parents from office work to working from home, or in many instances, losing their job. Stay at home orders resulted in children becoming socially isolated from friends and others and kept them from participating in normal extracurricular and community activities. As children moved to distance learning, they lost the supports and services provided through school systems supporting their academic, physical, social, and psychological well-being. The impact of these losses have been significantly compounded for children with disabilities, children living in poverty, and living in under-resourced communities.

Living through the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many children being stressed and traumatized. Trauma, when ignored, can lead to serious anxiety, depression, behavior problems, and risky behavior. Children who had a serious mental health problem pre-COVID experienced worsening of their mental health symptoms and more and more children began experiencing mental health problems for the first time.

As mental health problems have increased as a result of COVID, so has suicidal ideation, attempts, and suicides. Before COVID, suicide was already a serious public health problem in the United States; it is the third leading cause of death for children ages 10 through 14, the second leading cause of death for those ages 15 to 24. With COVID, young people have experienced increased suicidal ideation and attempts.

As daily routines were upended, families were forced to figure out new daily routines. Teleworking, distance learning, social isolation, and mask wearing became the new norm. Now, after nearly a year and a half of the new normal, families are navigating the move back into what was once their normal routine. Children have returned to school and are having to readjust to being back in the classroom and all that comes with it. It is not surprising that caregivers have faced extreme stress as they tried to navigate this new normal or that children’s social, emotional, and educational well-being suffered as a result of COVID.

How can parents, teachers, and others support children’s mental well-being?The ingredients needed for a child to develop good mental health are well recognized. In times of change and uncertainty, these ingredients are even more important. Children need to receive unconditional love as well as encouragement, guidance, and appropriate discipline from their caregivers. They need to live in an environment that is both physically and emotionally safe. Children take their cues from their parents and other adults in their lives such as teachers. It is important to take care of yourself and manage your own stress and anxiety. Open communication and awareness of changes in behavior are two more important key ingredients.

Communicating with childrenAs in all educational endeavors, caregivers and teachers need to work as a team to best meet the needs of each child. Communication is key to this partnership and sharing of information between caregivers and parents is essential for the child’s well-being.

It is important to give children opportunities to express their thoughts and concerns. In addition to the unique experiences having arisen due to COVID-19, children are hearing news stories about people getting sick and dying, people losing jobs, and people suffering long-term effects related to the pandemic. Listen to children’s concerns and take those concerns seriously. Give children your full, undivided attention so the child feels heard. Open the door for children to ask questions and allow them to tell you what they have heard about COVID on the news or from others. Answer their questions honestly, but in a developmentally appropriate manner. You may not always have an answer to a child’s question. It is alright to say you do not know something. However, it is important to be reassuring about the things you can control and will do to protect them. Never promise something that is out of your control.

Monitor children’s behavior for changesMonitor children’s behaviors for changes that may indicate omental health problems:

Sleeping too much or having trouble sleepingLoss of appetite or overeatingDecreased interest in things once enjoyedChanges in motivation and energy levelSubstance useRisk behaviorsDifficulty with attention and concentrationNo longer caring about gradesDecrease in self-esteemIrritabilityClinging behaviorWe do not yet know the full magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health or what the long-term effects of the pandemic will mean to young people’s mental health. It is imperative children receive the attention, support, reassurance, and, when necessary, mental health treatment.

Feature image by Annie Spratt via Unsplash

October 12, 2021

Why do companies deviate from standards and what shall we do about it?

Standards appear as legal or quasi-legal rules and relate to a variety of topics, including product or service quality, information security, environmental performance, health and safety in the workplace, and many more. Much has been written, or rather suspected, about corporate cultures of companies where standards were broken terribly. The Boeing airplane crashes or the Volkswagen emission scandal confronted societies with the question of why some companies do not adhere to standards while others do—competitors like Airbus appear to be complying with governance regulations and Volvo does not seem to have installed any banned software.

At the same time and not to be forgotten: organizational deviance also has a basic entrepreneurial quality. Today’s discourse on organizational deviance often assumes that the assessment of the flawed-ness of a behaviour is valid and applies equally to everyone. However, the entrepreneurial quality of deviance counteracts this conviction to remind us that “innovation” implies at its very core the action of distancing oneself from existing standards. With this approach, the concept of organizational deviance challenges the current discourse on organizational misbehaviour and shows that standards—for instance for aviation, medical technology, or the transportation sector—are in constant development and must also provide sufficient flexibility to allow for entrepreneurship and innovation.

Explanations for deviant or conforming behaviour that not only hold individual executives accountable but that also take the organizational context into account are urgently needed. The individual responsibility of executives must be expanded to the conditions of organizing that they shape—not just considering the concrete knowledge of deviant behaviour, such as a manipulation of software. Executives stipulate meaning for why standards are important, provide resources for standard enactment, as well as develop sanctioning and rewarding mechanisms for standard enactment, which make those terrible standard manipulations as described above or conversely the adherence to standards more likely. Whether organizations deviate from or comply with standards thus depends on how sensemaking, resource provision, and sanctioning mechanisms blend with or contradict one another—contradictions coming, for instance, from limited resources, inadequate sanctioning or rewarding mechanisms, or from overwhelming efforts to create meaning around standard-compliant work. All companies face these contradictions when implementing standards but deal with them in different ways. Their dealing with contradictions shapes the companies’ compliance behaviour.

Knowledge about what leads either to a certain type of deviance or to compliance is developed in separate academic discourses. Using structuration theory as developed by Anthony Giddens allows us to see organizational deviance as being constrained by powerful societal structures (such as legislation or standardisation bodies) as it is likewise a function of the expression of human beings’ will. In the end, standard agents like safety managers, regulatory affair units, or project managers, but also external stakeholders like clients, customers, or suppliers, who take or are given direct or indirect responsibility for standard compliance shape the organizational antecedents for standard enactment. Depending on how standard agents monitor the effects of these standard enactment and resulting contradictions, they accomplish a certain type of deviance or compliance.

What shall we do about it? Beyond the inspiration to study standard deviations and compliance in various empirical settings, these thoughts shall also inspire the ongoing debate around corporate criminal law, which in many countries is not yet installed. Our research findings provide a theoretical justification for why corporate criminal law is necessary and offer suggestions as to how internal compliance management can be assessed. We underline the far-reaching responsibility of executives for the organisational conditions for standard enactment, both in view of human safety as well as environmental protection, but also stressing the limits of standards for the sake of innovation wherever necessary. Misconduct is not only dependent on personality, personal preferences, or a certain organizational culture, but also on the conditions of work and organizing. Responsibility for organizational conditions should be ascribed to executives even they do not have any precise knowledge of a specific misconduct going on, as might have been the case, for instance, in the Volkswagen emission scandal. Further, legal rules, such as medical device regulation and railway law, must be subject to constant scrutiny and adjusted over the course of time to allow and prepare for innovation.

October 11, 2021

How can we solve the energy crisis and mitigate climate change?

Symptoms of the looming climate crisis abound: 50-year extreme heat events happening every year, melting of polar ice sheets, forest fires that encircle the globe, tropical cyclones of greater size, intensity and, as was very evident in Hurricane Ida’s recent visit to New York, unprecedented levels of precipitation. These are all expected outcomes of the increasing quantities of greenhouse gases we have been pumping into the atmosphere, and they are going to get worse. Nothing we are doing suggests that we will keep global temperatures within 2°C of pre-industrial levels—a goal of the Paris Agreement. An increase of 2°C would be extremely unpleasant. An increase of 5°C by 2100—predicted by some of the business-as-usual models and compatible with our current trajectory—would be planet-changing. Temperatures will not stop rising just because we have hit the arbitrary cut-off point of 2100, and what may happen thereafter is truly frightening.

Solving the impending crisis requires amending our energy choices, but we must appreciate how restricted our options are. Any energy choice ultimately lives or dies by its EROI: energy returned on (energy) invested. A seam of coal might supply a given quantity of energy. Against this there is the amount of energy we must invest to extract it—energy expended by miners, energy put into building tools, etc. The EROI of this coal is the ratio of the energy it yields to the energy we invested in its extraction.

Both material and social features of a society depend on the EROI of its energy sources. To maintain a society recognizably akin to ours in terms of its material comforts is estimated to require an EROI in the range 11-14. To maintain a society with some of the hallmarks of successful liberal democracies—high scores on the Human Development Index, childhood health, gender equality, female literacy—may require a societal EROI of around 25.

Mitigating climate change while maintaining energy sources with the required EROIs is no easy task.

Historically, fossil fuels have sported astonishingly high EROIs of 100+. Today, these have dropped to roughly 25-29, already uncomfortably close to the required minimum. Making fossil fuels climate friendly will require extensive use of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology. If it works at all—the jury is still out—CCS will be an energetically expensive process, almost certainly reducing the declining EROIs of fossil fuels below the point of viability.

Nuclear power is another option. Unfortunately, the EROI of nuclear fission has never been particularly high: most peer reviewed assessments coalesce in the 5-14 range. Nuclear fusion—if it can be made to work—will not be available in time to combat our climate problems.

This leaves renewables. However, it is unclear if any renewable energy source will have the EROI required to maintain society in its current form. Biofuels, with EROIs of 1-3, will not cut it. Peer reviewed estimates of the EROI of solar power range from 1 to 10, and for wind power from 3 to 15. Hydropower is promising, with estimates ranging from 10 to 84, but the dearth of suitable sites makes hydropower an unlikely general solution to our energy needs.

Food—an energy choice no less than fuel—provides the path between the rock of climate change and hard place of unworkably low EROIs. Meat requires the investment of 82-96 times as much energy as it returns. It is an energetic indulgence we can no longer afford. This energy choice is responsible for 14.5% of climate emissions. Crucially, 44% of all anthropogenic methane would be removed from the atmosphere by abandoning this choice. Methane is especially important in the battle against climate change not only because it is far more potent than carbon dioxide but because, with an atmospheric half-life of only 8.5 years, we can expect to be rid of it very quickly, in a timeframe that would make a significant difference to near-term climate mitigation.

Abandoning meat opens a further opportunity: afforestation—growing of trees on land not recently used for that purpose—on a vast scale. An acre of newly afforested land sequesters between 2.2 and 9.5 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. Let’s assume 5.5 tons. Annually, the average American is responsible for 16.5 metric tons of carbon dioxide. To offset the nation’s carbon footprint, therefore, we need to find three acres of land per person. Multiplied by the 330 million population of the United States, we need to find 990 million acres. Abandoning animal agriculture will not quite get us there but will take us surprisingly far. Currently, 834 million acres are devoted to animal agriculture, either for grazing or for the growing of animal feed crops. The extra land needed to grow crops for human consumption would, because of inefficiencies involved in converting plant protein into animal protein, be vanishingly small compared to that currently dedicated to animals.

In a recent satellite study, Jean-Francois Bastin and colleagues have estimated that, globally, 2.2 billion acres of land are available for afforestation. Afforested, this would erase humanity’s carbon footprint. The problem is that much of this land is currently used for animal agriculture. Abandoning animal agriculture, and afforesting this land, is the most effective step we can take against near-term climate change.

October 10, 2021

The democrat’s dilemma: how can we mitigate the conflicting responsibilities of citizenship?

Democracy is many things. It’s a form of government, a system of institutions, a decision procedure, a series of activities, along with much else. At a deeper level, though, democracy is the ideal of self-government among equals. In a democracy, the people are not mere subjects of the government. They are equal participants in government. They are citizens.

Understood in this way, democracy responds to a moral problem. Government in any form exercises power over those it governs. In a democracy, this power is shared among equals who disagree over how power should be used. Accordingly, when democracy enacts policy, some citizens are forced to comply. Thus, the problem: how can one be subjected to political power without thereby being subordinated by it?

Democracy answers that even when citizens find themselves on the losing side of a vote, they retain their equal status because they remain participants in government. In the wake of a political defeat, they are entitled to go on criticizing, campaigning, and organizing on behalf of their favored policies. Even when subjected to decisions they oppose, they are citizens rather than subordinates, each with an equal say.

Democracy is a dignifying proposal. Yet it invokes responsibilities, too. Two are fundamental to citizenship. First, citizens must take responsibility for their political order. They must use their share of political power to advance justice as they understand it. Second, they are also responsible to their fellow citizens. Just as no citizen is merely the government’s subject, no citizen is another’s inferior or boss. Citizens are equals; they thus must show one another a certain kind of regard. Citizens generally owe one another a chance to speak, a fair hearing, and a respectful tone, even when they disagree about crucial political issues.

But there’s the rub. It’s difficult to regard political opponents as our equals. After all, when we disagree about politics, we typically are disagreeing about what justice requires. Accordingly, our opponents strike us as not only wrong, but in the wrong. When the stakes are high, we cannot help but see our rivals as on the side of injustice. Why show those who favor injustice any regard whatsoever?

Call this the democrat’s dilemma. Note the lowercase “d.” The dilemma confronts citizens regardless of partisan affiliation. It arises because the two responsibilities of citizenship can conflict. In the fray of politics, treating opponents as equals concedes something to them and their views. Moreover, in showing foes the appropriate regard, we risk appearing fickle to our allies, which weakens our alliances. In short, meeting our responsibility to our fellow citizens contravene our responsibility for advancing justice.

Citizens hence face a conflict: when the political chips are down, why not treat one’s opponents as enemies rather than as fellow citizens? Why not regard them as obstacles and simply work to overcome them?

The democrat’s dilemma has been largely overlooked by political theorists. My new book Sustaining Democracy: What We Owe to the Other Side develops a response to it. Rather than emphasizing our opponents’ entitlements, I argue that sustaining democratic relations with our enemies is necessary if we are to uphold healthy relations with our allies.

The widespread phenomenon of belief polarization is the key. It shows that interaction within coalitions leads members to shift into more extreme postures. In working with allies, we subject ourselves to cognitive forces that render us more strident and unduly confident in our views. Further, our more extreme selves are also more conformist. As we shift towards extremity, we also grow more insistent on homogeneity among our allies. Belief-polarized alliances hence become fixated on poseur-detection and in-group purity. They consequently grow more dependent on centralized standard-setters for the group, thereby becoming more internally hierarchical.

Belief-polarized groups expel members who deviate from dominant expectations. They thus shrink until they are composed strictly of hardliners who adopt increasingly hostile attitudes towards those perceived to be lapsed allies. In this way, when we respond to the democrat’s dilemma by suspending civil relations with our opponents, we heighten our exposure to forces that transform our political friends into political enemies.

Observe that the democrat’s dilemma confronts citizens because they are doing what they should. Belief polarization is a byproduct of responsible citizenship. It cannot be eliminated, but only managed.

The key to managing belief polarization does not lie with learning to love our political enemies. It rather has to do with taking steps with to broaden our sense of acceptable variation among our allies. Were political conditions not already so deeply polarized, we might do this by listening to our opponents and engaging our most fundamental differences. As things stand, a different approach is necessary.

It might sound counterintuitive, but to manage belief polarization, citizens need occasions to distance themselves from their political alliances and rivalries alike. Citizens require moments of solitude that allow for a kind of political reflection that is detached from the clamor of politics. They need exposure to political ideas that cannot be fit into current partisan categories; they need to engage with perspectives that are addressed to political issues that feel alien. In short, belief polarization can be managed by seeing our contemporary partisan conflicts within the larger contexts and trajectories of politics.

Take a moment to Google the phrase “this is what democracy looks like.” The search will return thousands of images of masses of people gathered in public to express a common political message. This is, indeed, a prominent visage of democracy. But democracy requires citizens to be both active and reflective. The democrat’s dilemma shows how these two elements of responsible citizenship pull apart. The dynamics of belief polarization reveal that although democracy often is enacted when groups of citizens take to the streets, there is a crucial kind of democratic activity that is performed when a citizen sits alone in a library.

October 9, 2021

Can what we eat have an effect on the brain?

Food plays an important role in brain performance and health. In our review “Brain foods – the role of diet in brain performance and health” we have outlined the role of diet in five key areas: brain development, signalling networks and neurotransmitters in the brain, cognition and memory, the balance between protein formation and degradation, and deteriorative effects due to chronic inflammatory processes.

As an introduction, we make a survey of the neuroprotective effects of specific established diets like the Mediterranean, DASH, MIND, and Healthy Nordic diet, based on results from clinical human studies. There are continuously updated summaries and recommendations available, e.g. from the Global Council on Brain Health. In general, the old saying, “a healthy mind in a healthy body,” is still very valid, and the overall positive results on cognitive ability of entire diets can be summarised with: “what is good for your heart, is also good for your brain.”

Brain development Different aspects of brain structure and function that may be influenced by diet. From Brain foods – the role of diet in brain performance and health by Bo Ekstrand, et al. Used with permission of the author.

Different aspects of brain structure and function that may be influenced by diet. From Brain foods – the role of diet in brain performance and health by Bo Ekstrand, et al. Used with permission of the author.Looking at the importance of dietary components for the development of the brain, we can begin with lipids. The fatty acid composition of the polar lipids in the brain is very special, with arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) as major components. They are essential for the structure of synapses, the secretion and uptake of neurotransmitters, and as precursors for endocannabinoids—the intrinsic ligands for cannabinoid receptors. How the growing brain can be supplied with the relatively considerable amounts of these specific lipid components during the growth of the fetus and the newborn infant is still a little of a mystery.

Vitamins and minerals are as important for the brain development as for the rest of the body, and beside that they often have special roles in the brain. A few examples: vitamin B6, B9 (folate), and B12 are important in brain development, i.a. related to one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. Vitamin D has been called “the neglected neurosteroid” and has its own receptors in the brain. Iron is essential for development and transmission in the brain, and zinc plays a key-role in maintenance of the brain functions.

Signalling networks and neurotransmittersOur increasing knowledge of the specific neuronal networks in the brain and the neurotransmitters responsible for these has been the basis for therapy against both mood-related and cognitive disorders. Many dietary components can affect the amount and effect of neurotransmitters. A number of international prevention and cohort studies have studied dietary effects on mood disorders, like MoodFOOD, the SUN cohort, and My NewGut.

A large number of plant phenolics and other substances of herbal origin have been used both traditionally and in modern scientific studies, and there is a plethora of extensive reviews of each group of substances. An interesting overall question is why secondary metabolites from plants have such effects on the human brain, and the somewhat surprising answer is: the co-evolution with insects!

The so-called gut-brain axis depends on the secretion of peptide hormones indicating hunger or satiety, or direct neuronal signalling from receptors in the gut via the vagus nerve, and allows the brain both to monitor the accessibility of nutrients and energy in the gut as well as “warning signals” of possible toxicity via bitter taste receptors. There are “silent” taste receptors in the gut directly communicating with the brain. Clearly, the gut microbiota and its resulting metabolites has an important role in this cross-talk.

Cognition and memoryCognition and memory are closely related to a phenomenon called synaptic plasticity, which is connected with learning and novelty, and which is affected by aerobic exercise and diet. In our review, we describe the results of dietary interventions and the effects of some specific herbal components and vitamins, such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) found in green tea, resveratrol in red wine, ursolic acid in apples, the flavonoid curcumin in turmeric, and other anthocyanidins in blueberries, vitamin A and carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, vitamin B (e.g. folic acid), vitamin C, and vitamin E. Among minerals there are important effects of iron, magnesium, and zinc, to select only a few.

The balance between protein formation and degradationMany age-related cognitive disorders, of growing importance in a society with an aging population, are associated with the formation of oligomers and polymers of proteins in the neurons. The capacity of the cells to maintain the necessary balance between formation and removal of proteins depends on energy supply and regulation, and this may be influenced by dietary components.

Deteriorative effects due to chronic inflammatory processesChronic inflammatory processes are deleterious in the brain as well as in other places in the body. Herbal components can either be anti-inflammatory or offer protection against the long-term effects of inflammation. Traditionally one has looked at the anti-oxidative capacity of plant phenolics in order to neutralise reactive oxygen radicals, formed by inflammatory cells, but now the focus is on the upregulation of our intrinsic protective mechanisms.

Gene expression and epigenetics—influenced by diet?Besides what is mentioned above, dietary components also influence the gene expression and protein synthesis via epigenetic regulation. This might explain long-term dietary and pharmaceutical effects and might become an expansive field of research in the future, the “new bridge between diet and health.” Likewise, the newly discovered “neurobiome,” i.e. commensal bacterial flora living inside (sic!) the brain, might change our view of what is important for brain health and performance, and will certainly be a topic for future reviews.

Featured image: Ulrike Leone via Pixabay

October 8, 2021

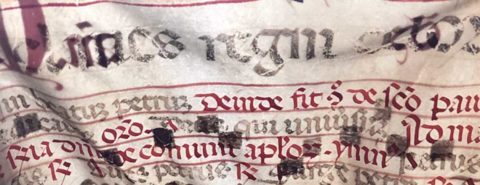

Fragmentology: bits of books and the medieval manuscript

A few years ago, when I bought an early twentieth-century octagonal lampshade, I knew I was buying a fascinating piece of Book History. This household object, made from a painted iron frame that radiates outwards from the central bulb-holder, has a shade comprised of eight cut-up panels excised from a late medieval religious service-book—an antiphonal. Some of the plainsong music—written onto a four-line stave—is from the Feast Day of St Clare of Assisi, who died in 1253. It is taken from an Italian manuscript, and in its reuse it’s like several similar standing lamps still functioning in situ at W. R. Hearst’s private library at Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

Photo by Elaine Treharne, used with permission

Photo by Elaine Treharne, used with permissionThe original manuscript from which this lampshade was made would have been a large book, perhaps made up of a whole calf- or sheepskin per folio or per opening: a book that was big enough for an assembled choir of monks, or nuns, or canons to see and sing from. Its present crumbling state is due not simply to the leaves being excised from their host book, but from the damage that happened when the volatile electric light set fire to the lampshade more than a century ago. As the lampshade deteriorates, so, too, fade voices from the past together with the skill and craft that produced the original manuscript. Here, the fragile fragments are perhaps the only remnants of an object that was used in services of worship where the singing lifted hearts and music upwards. It’s a shame that this medieval book was not similarly venerated when the person with a knife possessed and destroyed it.

So many fragments of manuscripts exist that a new term—Fragmentology—has recently been applied to the study of these parts and parcels. Librarians, archivists, and academics are paying more attention to what can be learned about textual culture from a folio cut, say, from a twelfth-century manuscript and later used by a binder to line the oak boards of a fifteenth-century book. Scholars are thinking through ways that single leaves preserved in libraries across the world can be digitally reconstructed into a virtual representation of the (or part of the) original book as it might have been first produced. Indeed, the accessibility of manuscript fragments themselves potentially brings a wide new audience to manuscript studies. Open access to collections that have been digitized like those at the British Library or the Vatican Library or Al-Furqan Digital Library means that anyone with an internet connection can browse the virtual manuscript (interestingly often initially displayed one folio at a time, as if the textual object were fragmented). In the commercial world of bookdealers and auction houses, meanwhile, individual medieval and early modern leaves or parts of leaves are widely available, some of them cut from manuscripts that were very recently sold as whole books. Such fragmentation, whether it is through digital access or physical possession means that viewers and readers frequently see an object that is representative of its host book, its earliest form perhaps, mainly through absence.

Photo by Elaine Treharne, used with permission

Photo by Elaine Treharne, used with permissionThe absence of the host book in its wholeness now—whether it was a large codex or a libellus (a little book)—is rather curiously the opposite of how the book seems to have been perceived in the medieval period. Then, in every sense, the book as an object, as a specific and significant carrier of multiple sets of meaning, was everywhere, even though relatively few people within the general populace might have owned or been able to read books for themselves. It’s possible to get an appreciation of how whole, solid, and tangible the book was conceived to be by looking at images of manuscripts (and scrolls and other text technologies) in illustrations within manuscripts themselves. There, miniature books are seen to be bound, full of leaves, solid objects. Sometimes the miniatures contain writing; at other times, their blankness anticipates the text that will be entered. Similarly, in mosaics like those at Ravenna or in the early churches of Rome, or the wall-paintings of religious institutions, miniature books—whether open or closed—are tactile, weighty things that signify knowledge, salvation, and the opportunity for conversation. Such synergy occurs between the reader and that which is being read; or between the audience and the words that are transmitted by the distant reader. The margins of books represent potential for an attentive user of the book to engage in debate or clarification; the space of the page also offers room for others to take temporary ownership of the book, entering poems or drawings that are unrelated to the central text, but show a desire to be inscribed into this most inhabited of objects.

What the medieval conception of, and response to, manuscripts demonstrates is that modern viewers of digital images, or purveyors and purchasers of fragments, should be alert to the reality these bits of books represent. Manuscripts from all over the world and in all languages and traditions that have survived to the present day must be protected as works of art and as testimony to the voices and endeavours of past creators and owners. Through this recognition, we really can shine a light on the efforts of peoples’ past.

Featured image by Elaine Treharne, used with permission

Who bears responsibility for the United States’ actions in Afghanistan?

Alongside the commemorations of the September 11 attacks, Americans marked twenty years since the United States’ invasion of Afghanistan. This invasion turned into a long and bloody war, which ended with the US’s hasty withdrawal at the end of August 2021.

Scholars of international law still dispute whether the decision to invade Afghanistan was justified. What is beyond dispute is the terrible price that ordinary Afghan civilians paid as result: at least 47,245 civilians were killed during the 20 years of conflict, millions more were displaced, and the lives of tens to hundreds of thousands of Afghans are now at risk because of the assistance they provided American forces during the conflict.

Given these very serious harms that the US inflicted on Afghani citizens, it is not surprising that many ethicists of just war argue that America now has important remaining obligations to Afghanis, even after it withdrew its forces. For example, obligations of reparation and compensation to those who were harmed by its actions, and an obligation to provide permanent shelter to those who had assisted the US and are now in danger.

But an important challenge to such demands is that they treat the US as a single entity while, in truth, it is comprised of millions of individuals. Were the US to discharge its obligations to Afghani citizens, it will be American citizens who will bear the actual costs. Do these individual citizens have the obligation to contribute to reparations or to welcome Afghani refugees?

We might seek an answer to this question by looking at more common scenarios where people incur a duty to put a bad situation right. Typically, we hold people responsible in this way if they had brought about the bad situation in the first place, if they benefit from it, or if they have some special relationship to the victim (e.g. he is a family member). But none of these reasons apply to many ordinary Americans with relation to the war: most did not benefit from it (indeed some have made huge sacrifices for it); most do not have special ties to Afghani victims; finally, while American taxpayers funded the war, they did not have much choice in the matter and many did not support it. To argue that they bear responsibility for the war, because tax money that was taken from them was used to fund it, seems to add insult to their injury.

So, do Americans who resisted the war or have not benefited from it bear responsibility for assisting its Afghani victims? I believe that they do. In my view, they do because they are acting together in their state, and because their state policies—even those they disagree with—are the product of this collective action.

People act together when—at the minimum—they intend to do their part so the goal they share with each other is realized. People may form many groups that act together in this sense: formal and informal, ad-hoc and institutional. Specifically in institutional groups, as anyone who works in an office, is part of a church, or a member of a local club knows, it is often the case that the decisions made by the group itself are not supported by all its members. Yet these members act on these decisions, despite their reservations. When they do so, they are acting together with the rest of the group, and they too are the authors of the group act: they are part of the “we” that enacted the group decision. As authors of these actions, they have a special responsibility for their outcomes.

These observations suggest that ordinary citizens are party to their state policies: they all share the goal of having a functioning state that can reach policy decisions through a democratic process and act upon them. Most citizens “do their part” in supporting this shared goal: they contribute to the tax system, obey state laws, participate in the democratic process, and so on. Citizens often object to specific policies, but as long they are seeing themselves as supporting their state more generally, in its capacity to reach and enact such decisions, they are party to the “we” who executes them. For that precise reason, it makes sense for all Americans to say “we invaded Afghanistan” or “we decided to withdraw,” even when they themselves did not agree with these decisions. Furthermore, as co-authors of such policies, they bear special responsibility to support and contribute to their state’s efforts to remedy the harms that these policies brought about.

Some might object that citizens don’t choose to be part of their state, so should not be encumbered with such responsibilities. But I disagree. After all, many of our relationships—from our families to our religious affiliations—are not born out of conscious and deliberate choices. And yet, we remain attached to them and recognize the moral obligations they generate for us. The same applies to our citizenship. We may not have chosen it, but many of us see it as an integral part of our identity. Most of us do not view our participation in our state as something that is forced on us against our will, even when we disagree with its actions. And because acting in our state is part of who we are, each of us has a special obligation to assist our state in discharging its obligations to those it has wronged.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers