Oxford University Press's Blog, page 92

November 4, 2021

Resisting racism within America’s WWII military: stories from the frontline

America’s World War II military was a force of unalloyed good. While saving the world from Nazism, it also managed to unify a famously fractious American people. At least that’s the story many Americans have long told themselves…

But the reality is starkly different. The military built not one color line, but a complex tangle of them, separating white Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans at all levels from ordinary GIs to those in high command—effectively institutionalizing racism and white supremacy throughout the military to devastating effect. The segregation impeded America’s war effort; undermined the nation’s rhetoric of the Four Freedoms; further naturalized the concept of race; deepened many whites’ investments in white supremacy; and further fractured the American people.

Yet freedom struggles arose in response to the color lines, and succeeded in democratizing portions of the wartime military and setting the stage for postwar desegregation and the subsequent Civil Rights movements. The following slideshow is just a portion of the sweeping, yet personal, stories of race and military. From the women who were the first Black WAVES to a decorated Japanese American soldier and his friendship with a white comrade, these are just a few stories of the resistance to racism within America’s World War II military.

[See image gallery at blog.oup.com]

November 3, 2021

English idioms: etymological devilry in baking and printing

It is curious how often those who have tried to explain the origin of English idioms have referred to the occupation of printers. Whether their attempts should be taken seriously is of secondary importance, because etymology may not always offer definitive answers. Regardless of their success, the attempts are worthy of note. A few examples will illustrate this point.

Baker’s dozenBaker’s dozen means “thirteen.” It is a typical English way of expressing this idea, because elsewhere one usually finds reference to the Devil’s dozen. The phrase may go back to the old practice: the retailers of bread from house to house were allowed a thirteenth loaf by the baker: a payment for their trouble. Yet as early as 1588, the following phrase occurred: “I will owe you a better turne (sic) and pay it to you with advantage, at the least thirteen to the dozen” (no reference to bakers!). Perhaps our phrase preceded the custom of rewarding bakers and was applied to them later. Likewise, in the early days of publishing (unfortunately, I have no reliable reference), it was the custom of printers to supply the retailer with thirteen copies of a book on each order of twelve. Once again it appears that thirteen to a dozen was an ancient way of designating generosity, while bakers and printers came later. Amenable to the laws of literary composition, the Devil will return to our narrative at the very end.

To cut one’s stickAn unpromising idea connects printers with the idiom to cut one’s stick “to flee in a hurry.” Conjectures about the origin of the idiom are many. Some are fanciful or far-fetched, from the behavior of dying Vikings to some biblical phrase (in Zechariah IV: 4-14, the cutting of a stick is described as the symbol of abruptly breaking off the brotherhood between two parties). The phrase must have had a much more mundane origin. A hired worker on a farm would cut a new stick from the hedge and place it in the chimney corner if he meant to leave at Michaelmas, that is, on 29 September. Apparently, the phrase became popular thanks to a song in Glasgow (“Oh, I cherished my brogues and I cut my stick”), being the adventures of an Irishman in which the cutting of the stick referred to the common practice in Ireland of procuring a sapling before going off.

He has cut his stick.

He has cut his stick.(By Joegoauk Goa via Flickr)

But here, too, it has been suggested that we should look for the origin of the idiom in the printing office: allegedly, the compositor about to leave cuts his composing stick. This etymology is strained (to put it mildly). However, it again reminds us that, once a phrase becomes well-known, it can be applied to many situations, and then occasional usage pretends to be the source. In such cases, a good deal depends on chronology (see more about dating idioms below). To cut one’s stick has not been recorded in books before 1825. Given such a late terminus post quem, almost any hypothesis begins to look realistic, but the reference to a song holds out greater promise, because it is amazing how many popular phrases owe their existence to the music hall and street singers.

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg(From Gutenberg Museum collection, via Wikimedia Commons)In print

The phrase in print is particularly curious and deserves our attention, among other things, because, while working on the entry print, James A. H. Murray, the first editor of The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) wrote an article about the history of such a seemingly simple locution (Notes and Queries, Volume 10, No. 9, 1908, p. 447). At that time, Murray was working on the entry print. The phrase has undergone many changes since the end or the sixteenth century. For example, set in print first meant “plaited” (about clothes). To be sure, we still have the word print-cloth and know what printed cloth means, but those phrases refer to color rather than plaiting. Other than that, I need not remind our regular readers what a treasure trove of valuable information the periodical Notes and Queries (NQ) once was: one can find there precious information about everything from farming to numismatics. Almost the entire set is available online. According to the OED, in prynte (sic) turned up about 1473: very early indeed, because Gutenberg’s printing press was ready for action in 1450. In the OED, the earliest example of set in print goes back to 1598. A correspondent to NQ (the same year, 10/XI: 176) cites the curious phrase fools in print (1633). Since 1633, fools have been quite successful in spreading their dubious wisdom in pamphlets, newspapers, and books. Now, if they are ambitious, they have the entire Internet at their disposal.

In the wrong box?

In the wrong box?(By Stuart Rankin via Flickr)In the wrong box

In the wrong box, that is, “in a wrong place” is another old idiom, made famous by the 1966 film. The OED offers a mid-sixteenth-century citation. It considers the possibility of an allusion to the boxes of an apothecary. All the later sources dutifully say the same. It has also been suggested that the source of the idiom is in the printers’ (compositors’) language: the compositor allegedly exclaims “in the wrong box!” when he finds a misplaced letter. Perhaps he does. Why shouldn’t he? But no citation in the OED predates 1555, too early a year for the printing business in England. This is what I meant when I wrote that in some cases the date of the first occurrence may be of decisive importance. More than once, we hear Murray remarking drily that a certain hypothesis is “at odds with chronology.”

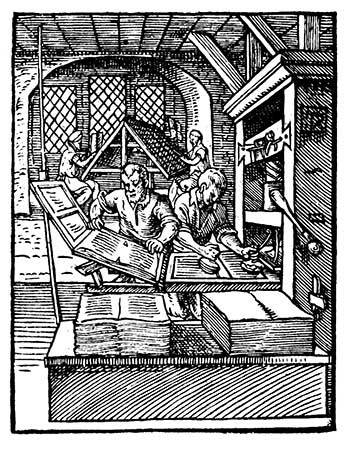

Mind your P’s and Q’s An old printing office.

An old printing office.(By Jost Amman via Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, we wade into the unmapped territory of mind your P’s and Q’s. The phrase is almost modern: no antedating to 1756 in the OED. Few other idioms have attracted so much attention. The proposed solutions are so numerous that even in my not too extensive research I have once run into a useless suggestion never mentioned elsewhere. Regardless of that instance, we read: “I was told by a printer that the phrase had originated among those of this craft, since young compositors experience great difficulty in discriminating between the types of the two letters.” Though the validity of this derivation has never been questioned, we lack a solid hypothesis about the origin of the phrase. In the delightful formulation of the OED, this etymology can be neither substantiated nor dismissed. Touch and go, as it were. I have no intention of wading through the P and Q puddle or quagmire. My idea was to show how often those who attempt to trace the source of an English idiom refer to printing. The subject “Idioms and Industry” deserves the attention of all those who are interested in the sources of the English language. See also the posts for 24 January and 31 January 2018 (mad as a hatter).

The printer’s devilAnd, finally, what do we know about the phrase the printer’s devil? This odd name was applied to an errand boy and an apprentice at the lowest level in a printing establishment (such boys took the printed sheets from the tympan of the press). Why were they called devils? According to a 1663 statement, the boys so commonly “bedaubed themselves” that the workmen “jocosely” called them devils. Neither The Century Dictionary nor the OED, both of which quote this earliest source, was in a hurry to accept such a seemingly rational explanation. Indeed, though the reference to black devils looks reasonable, it smacks of folk etymology. Other derivations are even less trustworthy. I would like to add my mite to the hoard of the otherwise unreliable hypotheses. The history of boy “servant” and boy “devil” have crossed several times (see—please see!—the post for 10 April 2013: “Will boys be boys?”). The printer’s devil was a boy, a servant and, I believe, therefore a devil. Perhaps I shot another arrow into the air, which, as we know, “fell to earth I knew not where,” but this is how I understand the puzzling locution. In any case, I promised the return of the Devil and kept my word.

Featured image by Mike Finn via Flickr

Why depth interviewing is essential to understanding individuals and institutions

From scraping “big data” from the internet to the analyzing genomic information about individuals and social groups, today’s researchers have a dizzying array of new methods for studying the social world. One consequence of this explosion of options has been to obscure the value of tried-and-true ones. Depth interviewing is a case in point. Once assumed to be a core research tool, many of today’s researchers have cast a skeptical eye on it. While past debates centered around whether we could rely on insights drawn from a limited number of people, new concerns have arisen from those who advocate direct observation, whether in natural or experimental settings. These skeptics express doubt that social researchers can trust the information gleaned from self-reports, pointing especially to the ways that depth interviewing may elicit accounts that are internally inconsistent or that contradict what people actually do. Such doubters argue that since people are prone to express ideas, beliefs, or behaviors that contradict one another, their self-reports are neither credible nor useful.

These critiques reflect a fundamental misunderstanding about what depth interviews can accomplish and how, when designed and carried out well, they are uniquely suited to gathering crucial insights about the nature of human consciousness and the relationship between thought and action. One-on-one interviewing creates a setting in which the “unobservable” becomes visible. Life history interviews allow people to describe and reflect on how prior experiences have led them to their current circumstances and outlooks, including what key events propelled them to devise life strategies and make consequential life choices. Focusing on the present, depth interviews provide a safe space where people are invited to share their most private experiences, thoughts, and feelings. While it is not be possible to observe a wide range of intimate activities, from sexual encounters to all sorts of dyadic interactions, interviews allow participants to describe and reflect on such events. And whatever the topic, interviews allow people to explore the meanings they attach to their actions and beliefs and to reveal the processes by which their social contexts created experiences that prompted ensuing responses.

Indeed, a key contribution of depth interviewing lies in its ability to uncover the contradictions that people express. Rather than accepting such accounts at face value, our research (and that of many others) demonstrates that we ignore contradictory thoughts and actions at our peril. Contradictory accounts as well as inconsistencies between “saying” and “doing” are central to human thought and action. Depth interviews provide an opportunity to delve into the nature of such beliefs and behaviors and explore the reasons people hold inconsistent views or act in apparently inconsistent ways. In addition to unearthing the meanings people imbue to their contradictory thinking or behavior, interviews can also discover the social contexts that give rise to them. When people express inconsistent beliefs or reveal conflicts between their values and choices, they alert us to look for the social contexts and cultural formations that create conflicts for which there are no simple or straightforward ways to respond.

Given the complexity of twenty-first-century life, it has become even more crucial to understand how people navigate the tensions created by conflicting institutional arrangements. In the context of a rapidly changing world, interviews shed light on the interplay between incompatible options and the evolving responses people craft to cope with them. Paying close attention to the different layers of meaning within each interview and carefully analyzing the patterns that emerge across all the interviewees enables depth interviewers to understand how social structures and cultural schemas shape human endeavors and how, in turn, social actors participate in constructing and potentially changing the world they inherit. By eliciting contradictory accounts and using them to delve into why people hold inconsistent beliefs or act in contradictory ways, depth interviews illuminate complex social patterns that would otherwise remain hidden.

Whether the goal is to chart how structure and action interact as individuals build their life paths, to learn about intimate experiences that cannot be observed, to uncover how people give meaning to their own and others’ practices and beliefs, or to understand how social arrangements prompt people to hold contradictory views and take inconsistent actions, depth interviews are the best, and possibly the only, method for learning about such core social dynamics. When interviewers ask probing questions, listen carefully to their participants’ answers, and analyze their findings with an eye firmly focused on discovering the patterns that emerge from the complex material they gather, interviewing enlightens us about the many dimensions of human experience that cannot be reduced to numbers, biological factors, or observable behavior. As we rightfully seek to expand the social science toolkit, it would be ironic if we lose sight of a method that offers unique access to the hidden dimensions of personal and social life. Instead, we must renew our commitment to a research technique that places human consciousness at the forefront.

Featured image by Christina@wocintechchat.com via Unsplash

November 1, 2021

Sustainability in action: dismantling systems to combat climate change

Some connection between sustainability and the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November is assumed, but the very idea of sustainability remains poorly understood.With students and colleagues, we have promoted systems thinking as the key to understanding sustainability in a variety of contexts. We believe wider appreciation of this perspective would pave the way for progress at COP26.

We have all heard the definition from the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED): “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” Ironically, this aphorism has impeded sustainability by tying the idea too closely to the theory of economic development. In fact, sustainability thinking has a much older history in population ecology, trophic flows, and the economic theory of the firm. The WCED drew upon this history in formulating a mandate tailored to the problems of international relations in the 1980s. Their statement consolidated two moral commitments that we endorse.

First, the WCED brought future generations into the universe of moral consideration in unequivocal terms. While many cultures, faith traditions, and individuals have expressed a sense of duty to their progeny, the WCED statement articulated a fundamental tenet of environmental ethics: Our decisions today must be evaluated in terms of their impact on the opportunities of unborn people, people who are not here to defend their interests in today’s decision-making. Second, and equally important, the WCED stated that we must never use our commitment to future generations as an excuse for neglecting the responsibility to redress the legacy of colonialism, racism, and other forms of oppression. In the context of the 1980s, this meant that industrialized economies must not attempt to meet their obligation to future generations by denying less economically developed nations the opportunity for economic growth. We would hope that COP26 continues to respect these two moral commitments from the history of sustainability.

“In short, a sustainable system is robust, resilient, and adaptive.”

However, the underlying logic of sustainability thinking stresses the way that key stocks—be they populations of plants or animals, abiotic elements like water and energy, or even money and capital—grow or shrink through flows that enter or leave. Systems thinking stresses how the level of stock generates feedback to these flows. Most obviously, the number of organisms in a population will affect the birthrate of organisms flowing into it. Yet stocks can also generate feedback to the flows of other stocks: a decline in the stock of nutrients for a population (stock) will increase the outflow (e.g., the death rate) for that population. At its heart, sustainability is a measure of the robustness of these stock and flow relationships, as well as their resilience—that is, their ability to recover after destructive events like hurricanes or an economic recession. A sufficiently complex organization of stocks, flows, and feedback can adaptively alter elements of its own structure in response to shocks that would otherwise send its key stocks into a collapse from which they would never recover. In short, a sustainable system is robust, resilient, and adaptive. The WCED’s definition did not draw attention to this underlying logic of sustainability.

With a narrow focus on the development process, advocates for sustainability have neglected the way that sustainability logic helps us understand the resilience of systems that reproduce social evils, as well as those that provide for social needs. In some formulations, the word sustainability becomes so closely associated with progress, goodness, or justice as to be synonymous. Yet, structural racism is arguably one of the most resilient systems in American culture. It has “bounced back” after numerous attempts to redress the oppression of nonwhite groups through slavery, dispossession, colonial marginalization, and overt racial prejudice. We should use systems thinking to understand what makes this system so sustainable and then identify the leverage points that could be targeted to make it less so. Getting away from the thought that sustainability is always a good thing will be especially important for addressing climate challenges in COP26.

COP leadership has articulated four goals for the 26th Annual Conference of the Parties. Realizing success will require focused attention to the sustainability of systems that undermine work toward achieving the goals. The work of countries to articulate and meet emission reduction targets in order to reach net zero carbon emissions (Goal #1) will understandably be confounded by the way in which energy systems are so dominated by fossil fuels. Despite decades of efforts to change this, the fossil fuel economy continues to be incredibly resilient. Understanding the controlling feedback relationships in this system—and those connecting it to so many other systems—is an example of applying sustainability logic and systems thinking when something is all too sustainable. Developing and implementing plans to adapt and protect communities and natural systems (Goal #2) is happening at international, national, regional, and local scales, but progress is halting. In many cases, political and financial power dynamics impede progress; protecting the status quo is a knee-jerk reaction on many fronts. What makes political and financial systems that are contrary to COP26 goals so sustainable? The sustainability of these systems is likely to also challenge efforts to mobilize the finances (Goal #3) needed to reduce carbon emissions and adapt and protect communities and natural systems and to foster and accelerate cooperation among the parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement and between governments, businesses, and civil society to meet overarching climate goals (Goal #4).

In our work, we have focused primarily on the robustness, resilience, and adaptiveness of systems that undergird our ability to meet important social goals like protecting critical ecosystems and fostering social justice. But we also recognize that making some systems less robust, resilient, and adaptive may be necessary to achieve sustainability goals. Couching the work of COP26 in terms of sustainability is intuitive; it is less intuitive but no less important to realize that meeting climate goals may require us to dismantle some systems that are all too sustainable.

Learn more about the history of COP26 and the 2021 conference goals

Feature image by Appolinary Kalashnikova via Unsplash

October 30, 2021

The appearance of the goddess Discord: Gustave Moreau and a mythical tradition

A vivid demonstration of how Greek myths may appear today in unexpected ways was displayed in the Gustave Moreau exhibition at Waddesdon Manor, which took place between June and October 2021. The exhibition presented a series of Moreau’s watercolours, commissioned by Anthony Roux in 1879, illustrating the Fables of La Fontaine.

One of the fables (Book VI, Fable XX) describes Discord, the Greek goddess Eris, beginning with her ejection from Olympus for causing dispute among the gods with an apple. Embraced by humanity with open arms, she magnifies every small dispute, fanning each tiny spark into a conflagration. However, she has no fixed abode where she can be located in case she is needed, so she is assigned as her residence the house of Hymen (god of marriage).

Although most of La Fontaine’s stories are inspired by Aesop, this one has no origin in the Greek fabulist, but goes back to Homer, Hesiod, and Vergil. In Theogony Hesiod makes Eris the daughter of Night, and in Works and Days he famously describes two Erides: “One would be commended when perceived, the other is reprehensible […] The one promotes ugly fighting and conflict […] (The other) is good for mortals.” However, the main presence of Eris in Greek mythology is in the context of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, which culminated, after the Judgement of Paris, in the Trojan War. Thus, a connection with the wedding is already evident, but La Fontaine turns it into something amusing, involving human quarrels between married couples.

What did Gustave Moreau make of this story? Usually considered as the first French Symbolist painter, Moreau rejected the dominant artistic trends of his time in order to explore his own anxieties and longings by returning to the Greek myths. He had a solid education in the Classical world but followed an idiosyncratic path through the mythological tradition.

Claude Philips, as quoted in the Waddesdon Manor exhibition catalogue, describes Moreau’s Discord like this:

“A beautiful, snaked-crowned Fury, half lies, half reclines, in deceitful repose on the steps of a richly ornamented temple, her pallid form being set off with draperies of heavy poisonous green and fluid red, which add strong force and pathos to the design.”

Moreau follows La Fontaine in locating Discord at the temple of Hymen, under the statue of the god, and represents her as a beautiful woman who reclines with her eyes closed. She is partially naked, but her red cape, ornate micro-skirt, and the adornment on her legs and feet, suggest “oriental” glamour. Moreau repeatedly associates repose with female beauty and its contemplation, as in his renditions of Galatea, Delilah, Semele, and others; in his numerous paintings of Galatea, for instance, he usually represents her reclining, naked and enticing, exposed to her viewer Polyphemus. In the case of Discord, the snakes on her hair visually associate her with Medusa and also with the Furies. However, nothing in Moreau’s image of Discord evokes that degree of menace, and she even has something of innocence in her placid expression, perhaps reflecting a melancholic longing for her former life among the gods. The only hint of disharmony comes from the two Erotes flying away—perhaps frightened at the sight of her—and a third Eros lying dead on the floor, his torch beside him, as if the presence of Discord had resulted in the annihilation of Love. Paradoxically, in the distance Moreau has included a pair of lovers, seemingly unaware of the proximity of Discord.

Moreau’s Discord shares many features with one of the dominant themes of his art: the beautiful, passive, and distant woman, exposed to male view, a motif which he shares with the Pre-Raphaelites. Moreau has often been compared to Edward Burne-Jones, the painter associated with the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, who saw Moreau’s watercolours of the fables when they were exhibited in Paris in 1886. Burne-Jones also represented Discord in his painting The Feast of Peleus as well as in the lower part of the Troy Triptych. But in these images, she is depicted as a sinister character with dark purple tunic and brown wings, while the gods look at her in fear. In spite of his connections with Burne-Jones, Moreau’s representation of Discord does not coincide with his, as the two artists have chosen different mythological moments and depict the goddess in completely different attitudes. Another striking contrast with Moreau’s peaceful image of the goddess can be seen in J.J. Grandville’s illustration of the same fable by La Fontaine, which shows an ugly and furious Discord next to a violently arguing matrimonial couple.

Moreau’s Discord departs from these and other, more traditional depictions: his image is more Moreau than Discord. It seems that only the defeated Eros reflects the destructive character of Discord and her impact on love and marriage.

Feature image: Altes Museum, via Wikimedia Commons

A pre-9/11 action movie with a Muslim hero shows what could have been

In the fall of 1999, another action movie came and went, garnering disappointed reviews and a pittance in ticket sales. Adapted from Michael Crichton’s novel Eaters of the Dead, The 13th Warrior offered a surprising premise: a tenth-century Abbasid ambassador is recruited to join a band of Vikings(!) against an army of mysterious, monstrous creatures. Crichton’s idea thus combined the Beowulf epic with the writings of Ahmad ibn Fadlan, who travelled from Baghdad to Russia in the tenth century.

The 13th Warrior isn’t a great movie, nor is it even very good. The opening credits give a clue as to why: at one point, the job of director shifted from John McTiernan (Die Hard) to Crichton himself, which gives the narrative a disjointed feel. But while the movie isn’t great, there’s no denying how cool it is, which is why viewers continue to revisit it. The Vikings are intimidating, the bad guys are scary, the hero rises to the occasion, and there are some intense action sequences, including a death-defying underwater escape from a cave. At its heart, it’s a story of people from different backgrounds learning to respect and value one other.

What has added to the film’s appeal over the years is its choice to center a devout Muslim in a macho American action movie. The ibn Fadlan character is like so many other Hollywood tough guys: handsome (it’s Antonio Banderas!), brave, resourceful, and guided by a code of honor. Throughout the movie, we see how his background has made him into a hero worth following. When the Vikings make fun of his small horse, he shows off his equestrian skills. When the Vikings give him a broadsword too heavy for him to lift, he sharpens it into a scimitar, wielding it like their best warriors. When the Vikings leave him out of their conversations, they soon discover that he has already mastered their language.

These breakthroughs always follow a zoomed-in shot of Banderas’ face. He focuses, eyes scrunched up, and suddenly understands. We can almost see the gears turning in his mind as he cracks their codes. Early in the movie, he says, “I am an ambassador, dammit… I am supposed to talk to people.” Diplomacy is a higher calling that aligns with his cultivation as a man of piety.

The 13th Warrior official 1999 trailerThe main motivation for making this film was to cash in on Crichton’s earlier success with blockbusters like Jurassic Park. At no point did the filmmakers claim that they were trying to create a positive portrayal of Muslims. And yet, by some curious accident, they arguably succeeded in doing just that. Ibn Fadlan’s belief is the bedrock of the character’s motivation. There is a touching scene in which he teaches one of the Vikings to write by scrawling a line in the sand: “There is only one God, and Mohammad is his prophet.” Later, in the moments before the climactic battle, ibn Fadlan kneels in sajda, asking God for guidance in what may be his final hour. And at the end of the film, ibn Fadlan’s voiceover tells us that his time with the Vikings has made him a better servant of God. Perhaps most important, Ibn Fadlan neither questions his faith nor performs rhetorical defenses of it. He’s noble because of it, not because of an anachronistic secular humanist take on his religion.

Following 9/11, the declaration that ibn Fadlan teaches the Viking, the Shahada, would be framed as suspicious or worse. But here, the Viking re-writes the statement with all the chill in the world. When he makes a mistake, ibn Fadlan gently corrects him. The art historian Stephennie Mulder has suggested that this kind of imperfect copying was a sign of the times. She writes, “The presence of pseudo-Kufic [early Arabic script] tells us something important: that Arabic was valued by the Vikings as a mark of social status or capital, much in the way we might today buy a perfume with “Paris” written on it.” For this reason, Mulder adds, the Shahada may be the most common inscription in Viking Scandinavia. It seems that Crichton’s flight of fancy inadvertently captured historical truth.

The depiction of ibn Fadlan is not without its flaws. One could argue that the portrayal relies on a surface level understanding of Islam. The visual cues are certainly quaint. For one, Banderas’ character wears exaggerated and even clumsily applied kohl. Confusingly, he rides a camel through a landscape that resembles the well-irrigated hills of the Cotswolds. And had Banderas been a Muslim himself, he might have noticed that addressing God as “Father” in the prayer scene is more of a Christian practice than an Islamic one.

Still, there is an odd innocence to this movie, given where it sits in history. Just a few years before, another medieval action flick—Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)—included a scene in which Muslims during the Crusades appear as savages, no better than the monsters that ibn Fadlan faces. James Cameron’s True Lies (1994) pitted Arnold Schwarzenegger against a terrorist organization with the unsubtle name of “Crimson Jihad.” The film rightly drew protests.

And of course, less than two years after The 13th Warrior, the US response to 9/11 obliterated any chance of a positive portrayal of Muslims in a mainstream film or TV show for a long time. When Muslims did appear in an action movie, they were often depicted as either terrorists or victims of terror (presumably from other Muslims). There were a few films that tried to be evenhanded, like Ridley Scott’s Crusader epic Kingdom of Heaven (2005), which earned praise for its sympathetic portrayal of the sultan Saladin. But these were few and far between, and virtually never placed a Muslim at the center of the story. Even the 2007 Syrian TV series Saqf al-Alam, also inspired by ibn Fadlan’s travelogue, centered on post-9/11 geopolitics.

Though long delayed, Hollywood has finally begun to address this problem, though it has a way to go before correcting it. A planned Ms. Marvel project features a Muslim woman as a superhero, at last catching up to the long tradition of Muslim women as leaders and public benefactors. The actor Riz Ahmed has launched a mentorship scheme offering $25,000 grants to Muslims in entertainment.

Maybe The 13th Warrior, like the Viking’s attempt at writing, is a pastiche that can open the door for more. Through the vehicle of an exceptional hero, the movie’s major statement is one that sci-fi is well poised to make. Suspending disbelief ironically adds believability to the idea of characters crossing borders with ease. Thus the classic molds of oriental wonder and sci-fi camp dissolve into a strangely heartwarming story of people overcoming their differences and working toward a common goal.

October 29, 2021

How OUP is innovating for the future of open research

Open research covers a wide remit of publishing practices, policies, and technical solutions that are continuously evolving to meet the needs of the research community. In a post-truth world of disinformation and information overload, it is becoming ever more important that we ensure research can be disseminated effectively to reach the right audiences and ensure information is interpreted correctly. Innovations in open research can help to address this, making a wider range of information accessible and available, ensuring reproducibility, and facilitating reuse.

The future of open accessLet’s begin at the beginning: open access. Open access (OA) is now a well-established model in publishing. Historically, OA journals have relied on author payments in the form of Article Processing Charges (APCs), which mean articles can be made openly accessible at the point of publication. However, this in itself can create inequities for those unable to pay to publish.

As we see increasing interest in OA across a wider diversity of subject areas and in a more global environment, publishers are innovating to support OA in a more equitable way. Read and Publish agreements represent a major change in the way that institutions and funders support OA publication, removing the burden of payments from individual authors and encouraging OA in fields that are typically less well funded and where APCs may have been a barrier for many authors. Other emerging models similarly seek to remove the burden of APC payment from individual authors, and, in some cases, spread costs among author groups or institutions, such as the Subscribe to Open model which uses the existing library subscription process to convert journals from subscriptions to OA one year at a time.

While most OA publishers offer developing country waiver schemes (you can find information about OUP’s scheme here), we also need to consider better solutions to this problem without those authors from developing countries needing to ask for waivers. Initiatives such as Research4Life already address this issue for access to subscription content, and we should next be looking at how to do similar for OA publication.

Introducing open methodsAs open access has become more established, there have been various initiatives focused on making other research outputs available and accessible alongside the finished paper, widening our perspectives and providing much needed context to original research papers.

Open methods is the open publication of research methodologies and represents an important piece of the research puzzle in terms of improving reproducibility, minimising redundancy in research, and increasing transparency. The publication of research protocols has expanded outside of medical research (where protocol publication is common, and, in many cases, required for many researchers) into other fields.

Andrzej Stasiak, Editor-in-Chief of Biology Methods and Protocols explains the importance of this in more detail:

“The description of methods in important scientific findings is frequently relegated to supplementary materials, where authors devote much less time and attention to the details. When other research groups want to reproduce the reported findings or re-use the method in their own research they frequently discover many missing elements needed for the accurate reproduction of the original research. …

Papers devoted to detailed description of methods and protocols used can provide sufficient details and guidance that others can reproduce the presented findings in their own labs, and build on important discoveries. Open access of such methods papers is especially important for helping researchers in countries with low scientific budget to master new methods.”

One initiative that aims to make reproducible methods openly available and minimise publication bias is Open Science’s Registered Reports initiative. A number of OUP journals are participating in this initiative, which has been particularly popular in neuroscience and psychology where reproducibility has historically been a concern. “The introduction of Registered Reports into Neuroscience of Consciousness is a major step in our commitment to the open science agenda,” explains Anil Seth, Editor-in-Chief, Neuroscience of Consciousness:

“Registered Reports have become established as a gold-standard method for conducting and publishing hypothesis-driven research, with many distinctive benefits including guarding against post-hoc ‘fishing’ for findings, and enabling publication of null results. Increasing the reliability and replicability of research findings through Registered Reports will play a significant role in advancing research in our home community of consciousness researchers.”

Providing context to published articlesInnovations in content types provide further context to published articles. Integrations with data repositories, meaning that datasets can be made available alongside the published articles, have been common for many years in some fields. More recently, authors have been encouraged to make their underlying code available too, allowing others to more easily reuse their data and reproduce results. OUP publishes a number of journals that are piloting a service from CodeOcean to seamlessly deposit their code as part of their submission, which can help to facilitate the sharing of this information.

However, contextualizing content is not limited to sharing supplementary data and code but also to capturing evolving commentary on the research. Published articles can provide a snapshot in time but can quickly become out of date. Open annotation is an innovative way to allow authors to add context, or updates for readers.

This has been recently trialled in Oxford Open Immunology. Using Hypothes.is software, the journals can facilitate “living review” articles, which can be annotated by the authors in real-time to provide useful context, updates, and links to new research of relevance. As Luke Davies, author, Oxford Open Immunology, explains:

Transparency in the review process“COVID-19 science moved rapidly—we quickly got a snapshot of the overall picture of immunopathology in COVID-19, but it was like a paint-by-numbers; we knew there were bits missing and new colours were coming in week by week, but it would be months before we got the whole picture. A LIVE review allows us to carefully add to the picture over time, while still delivering an up-to-date snapshot of the field that can aid ongoing research.”

How we review research is also changing, with many journals moving towards more transparent peer review systems in a bid to open up the peer review process and increase trust in the system. Published peer review reports can also provide useful insights and context for readers. Oxford Open Immunology allows authors to decide at submission if they wish to opt into transparent peer review, while the newly launched Oxford Open Neuroscience will publish all decision letters alongside the published article. Reviewer reports may also be made available on other platforms, such as Publons, separate from the published article.

New innovations and developments are constantly being proposed and rolled out across the publishing landscape, including at OUP. By opening the broader research ecosystem, publishers can better support researchers and, in doing so, have a tangible impact on major global problems—such as climate change, health inequity, and, of course, dealing with pandemics.

Caring for our most vulnerable: lessons from COVID-19 on policy changes in the care home sector

If the true measure of any society is how it cares for its most vulnerable, then the catastrophic impact of COVID-19 on care home residents during the first wave of the pandemic was a sad indictment. Older people living in care homes are truly our most vulnerable. They live in care homes because of disability, frailty, and cognitive impairment, and are dependent on staff for round the clock care.

We have learned, over the course of the pandemic, that much can be done to protect care home residents from COVID-19, with measures including routine testing of staff for infection, routine use of personal protective equipment, and careful attention to quarantine of those entering and leaving the home during COVID-19 surges. Even before the successful roll-out of vaccination for residents, there was evidence that these interventions had tempered the worst effects of the second wave of the pandemic.

However, each intervention implemented for COVID-19 came with a cost. Routine testing placed increased burden on already overwhelmed staff, which distracted from routine care duties at a time when homes were under unprecedented demand. Personal protective equipment interfered with routine communication with residents, many of whom have sensory or cognitive impairment. Quarantine regulations enforced social isolation which has been associated with cognitive and physical decline for residents.

If policymakers, at times, got the balance between these risks and benefits wrong, then this was a consequence of both the complexity of the situation and the rapidity with which circumstances changed, and changed again, throughout the pandemic. There were, however, ways in which better balance could have been achieved through better understanding of how care in care homes is organised, and the considerable lengths to which staff will go to protect and support their residents.

During the autumn of 2020, as part of the CONDOR-CH study, we conducted research, published in Age and Ageing, that showed for the first time the organisational burden of conducting routine swab testing and sending it off for laboratory Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in care homes.

We had anticipated that this would set the ground for a simplified approach to testing in care homes, including use of point-of-care testing. We set about validating point-of-care PCR and automated antigen testing technologies, showing that these could be feasible and safe if implemented with sufficient awareness of how the care home context differed from the other settings where such tests were deployed.

In practice, policymakers chose to deploy Lateral Flow Tests (LFTs) in care homes. We summarised in our recent Age and Ageing Commentary the issues raised by this. Firstly, there was incomplete adherence amongst care home staff and residents to LFTs regimes, in part a consequence of a substantial burden of work associated with conducting the tests. There was also limited understanding of how false positive and negative results from these tests interfered with the routine of care in care homes. These concerns might have been understood and addressed before roll-out if these technologies had been researched in a similar way to our PCR and automated antigen tests approach.

The Academy of Medical Sciences has neatly outlined that the challenge for the coming winter is not just COVID-19, but rather the combined effects of COVID-19, influenza, and other winter infections such as the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). LFTs are unlikely to be an effective response to these multiple challenges, because they only test for one pathogen at a time. It is, instead, multiplex testing technologies that will have to be evaluated. The lesson from the introduction of LFTs in the winter of 2020 is that these technologies could be deployed at the point of care in care homes, but only if they are evaluated in this setting to understand how their introduction will affect workflow and day-to-day care.

The bigger issue here relates to how care homes are considered as part of the health and social care sector. The pandemic has seen many policymakers and leaders waking up to how pivotal care homes are to health and social care delivery. This led to a plethora of guidelines, mandates and policies governing long-term care. These have, though, frequently been written with limited understanding of the lived reality of day-to-day life and work in care homes.

Our work on CONDOR-CH shows how even basic evaluation of new approaches and technologies in care homes can substantially inform their implementation. As governments around the world, including our own governments here in the UK, embark on reform of long-term care, they’d be well advised to ensure that the consequences of implementation are not taken for granted. Time and energy should be invested in understanding the impact of policies and technologies for residents and the staff who care for them. By taking into account such considerations, we’ll be caring for our most vulnerable, and that will reflect well on our society.

October 28, 2021

What can early US welfare policies teach us about caring for our communities?

Once or twice a year, I spend the semester with 50 college sophomores pondering two questions. The first one is: how have people in the past cared for the neediest people in their community? The second is: how should we?

In this General Education requirement course, second-year students are expected to study a subject in the typical academic way while also studying it through a form of service learning. My university calls this a “community experience.” Last year, students spent part of their semester in a local food pantry, or a local charity shop, or helping to overcome COVID-19 isolation by talking on the phone with residents of local subsidized housing units.

At the food pantry and the charity shop, students do everything from sorting donations to selling them to clients. The subsidized housing project was new last year in response to the effects of our self-isolation to combat COVID-19. Residents of subsidized housing were unable to congregate in social spaces in their buildings or go to many places they used to. My students signed up for weekly phone calls with a “virtual buddy.” It went better than I expected. Some “buddies” said this call was their one voice conversation per week. Students working with all three groups learned a great deal about people’s needs in their own town.

At the same time, we answer the first question with examples ranging from the ancient Mediterranean world to medieval England to the twentieth-century USA. This class was a stretch for me, an historian of colonial North America and the early United States. But with the help of a medievalist colleague and a community experience specialist, it has come to work well. For me, teaching a broader history of charity, poor relief, and poverty has really helped my research in early American poor relief. My students get a class that covers much of the ground of a survey, but with a deep dive into social history that many tell me they have never seen before.

Through blog posts, students also tell me how they think we should best care for the needy of our community. Having seen a wide array of examples from the historical record and having helped to care for those in need themselves, they often have sophisticated and thoughtful answers to this question. Their answers generally range from a very carefully limited government poor relief to a very full provision of government poor relief. Their answers also continuously challenge me to think about what my answer would be.

While I am not an expert in today’s constellation of government, private, and mixed government/private poor relief, I do know a lot about how poor relief worked in the early USA. And there is one idea from this period that I think was really effective: local governments paying local people to help their neighbors.

It is astonishing to discover how many local women and men got cash from their town treasurer in exchange for things they provided their neediest neighbors. Much like English people working with the Elizabethan Poor Law, early Americans might give anything from room and board, to firewood, to groceries, to nursing care, to a proper burial. And for this, the overseers of the poor (a locally elected position) would direct the town treasurer (another locally elected position) to give dollars to the provider. For most of these providers, the town cash was a small addition to their household income. For some, it was a mainstay.

One such provider was called “One-Eyed” Sarah. She lived in and around Providence, Rhode Island in the early nineteenth century. An Indigenous woman, she was credited with saving the lives of patients who were both desperately ill and too poor to afford healthcare. Clearly skilled, it helped both her and her patients that she was reimbursed by the town treasurer, at the direction of an overseer of the poor. This reimbursal allowed Sarah to give full-time, strenuous, attentive nursing to people who needed it but could not afford it. It also allowed her to bring cash into her household, to buy real estate, and to protect her own children from the most difficult working environments.

I have many questions about “One-Eyed” Sarah, despite years of research. I still don’t know her last name, for certain, or which Indigenous nation she was a part of. Her work came to light, though, in an 1811 series of newspaper articles. Reading these combative articles more than 200 years later, one thing really jumps out at me: the authors argued about almost everything except whether government poor relief was a good idea. Instead, they focused on whether government poor relief was being delivered humanely. Since I live in an era when government poor relief—or “welfare”—is a politically divisive idea, I found it interesting how little it seemed to divide politically engaged Rhode Islanders in 1811. I’ve come to the conclusion that local governments paying local residents to help their neighbors was a big part of why welfare was uncontroversial at the time. Welfare made lots of locals happy.

My students and I still don’t have a single, definite answer to how we should care for the neediest people. But I often wonder whether local funds given to local providers of care, like “One-Eyed” Sarah, should not be a bigger part of our answer.

Featured image by congerdesign via Pixabay

October 27, 2021

Spooks are spooks, but don’t ignore organic pumpkins

We are one more week closer to Halloween, and pumpkins are ubiquitous. I feel duty-bound (they used to say: “It is my bounden duty”) to attack the pumpkin market from my professional point of view and ask: “how did the pumpkin get its name?” The well-known facts can be found in any reliable dictionary, for example, in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, whose entry I’ll reproduce and amplify below.

In Greek, síkuos pépōn designated (perhaps still designates?) a kind of melon not eaten till quite ripe (the síkuos being eaten unripe). The word pépōn “large melon” was an adjective but used as a noun. (This process, known as substantivization, or nominalization, is easy to illustrate in English. Take the adjective blind. The first step toward becoming a noun can be seen in the plural: the blind. The definite article suggests the presence of a noun. English can go even farther: compare the reds, in which the plural ending is the same as in roads, reeds, and raids. But we cannot say the blinds for the blind, as we can do with the whites, the blacks (for instance, in chess) and the reds, without running into the noun a blind, a seventeenth-century coinage meaning “a screen”). From Greek the word traveled to Latin and became pepo, genitive peponis “watermelon; pumpkin” (note the ambiguity!). The more common Latin word for “pumpkin” was cucurbita, whose descendants are known as Kürbis in German and as gourd in English (the latter via French). The difference between the pumpkin and the gourd can be passed by in this story, though I may mention the fact that pumpkin is defined as “a kind of gourd” and gourd as “fruit of cucurbitaceous (!) plant.”

Kukurbita, with its kukur-, is a funny word, like murmur and Latin purpur “purple” and carcer “prison (compare English incarcerate). Whatever the original impulse behind such words, with reduplication (ku-kur, mur-mur, car-cer, and even cucurri, the perfect of Latin curro– “to run”) they sound like emotional formations (compare she is very, very clever; my new job is so-so). The form of a full-grown pumpkin evokes the idea of amusing plumpness. The Russian for “pumpkin” is tykva, and it makes one think of tykat’ “to push with a finger,” though the association has nothing to do with the word’s etymology.

Plump, pompous pumpkins all over the place.

Plump, pompous pumpkins all over the place.(Photo by Megan Lee via Unsplash)

Anyway, pepo/peponis made its predictable way from Latin to French and became pompon (om stands for a nasalized vowel), as a vegetable name now obsolete. Today, the French for “pumpkin” is citrouille, from the color of a citrus fruit (lemon, orange, and so forth). Pompon produced English pumpkin, rhyming with bumpkin, both with a Dutch diminutive suffix. Pump– is not the ancient root of pumpkin. Yet this root is amazingly appropriate: it resembles plump (that is, round) and pomp (a pompous person puffs up with self-importance). In the new environment, pumpkin found several close allies, pump and pomp among them.

The Greek ancestor of pomp meant “solemn procession” (Latin had pompa). Solemnity presupposes pomposity, just as the shape of the pumpkin evokes the idea of pompous rotundity. Another expressive name? It would be dangerous to explain the origin of so many words by applying the same yardstick to all of them. Etymological dictionaries explain in detail how some such words came about and how they traveled from land to land or say nothing about them (obscure are, for example, Latin cucurbita “pumpkin” and English pump “a kind of shoe”). Pump “the device for raising water” fared a bit better, but in its checkered history, the unexpected form plump(e) turns up, and Modern English plump in all its senses makes one think of sound imitation.

My modest aim is to show that pumpkin has a form in perfect harmony with what we expect such an object to look like. My second point is slightly different. We have seen that pumpkin got its m relatively late. Its new root, with m in the middle, produced a host of spurious relatives, among which the vegetable name found even more security than in its original environment. Two words deserving our attention are pamper and pimp. On pimp I wrote two posts very long ago (6 January and 13 January 2007) and invite our readers to consult them. Here I’ll only summarize those essays. (Once again, I was saddened to read the comments added years later. Please, if you find an old story to be of some interest, add your comment to the latest post. Otherwise, I’ll never see your remarks.)

A pimp and a pump: different, even if misleading, grades of ablaut.

A pimp and a pump: different, even if misleading, grades of ablaut.(Images by left: Nathan Rupert & right: Fikri Rasyid)

Many words have the root pimp ~ pamp ~ pump (the variation is a trivial case of ablaut). Those with i in the root tend to designate small objects (for instance, pimple), while those with u and a are usually tied to big sizes and “inflation.” Such is English pamper, originally, “to overfeed,” as opposed to obsolete English pimper “coddle.” German pampig means “arrogant.”

The best-known English word having the root p-mp with i in the middle is pimp. It does not mean only “procurer of prostitutes.” Nor was it coined with this sense. In dialects, pimp means “a bundle of firewood,” sometimes defined as “faggot” (incidentally, this astounding line in a dictionary—pimp “faggot”—sent me on a wild goose chase for the etymology of both words; full entries can be found in my An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction). Pimp also means “helper in mines; servant in logging camps,” the reference being to a person’s inferior status or diminutive stature. German Pimpf means “an inexperienced boy,” that is, someone who was unable to produce a big Pumpf “fart” (hence also Pumpernickel bread; fortunately, the origin of the name is rarely understood by those who consume the product).

A reincarnation of a big good pumpkin, a finale devoutly to be wished.

A reincarnation of a big good pumpkin, a finale devoutly to be wished.(Image by Dilyara Garifullina via Unsplash)

Before the Nazi era, Pimpf was a street word in Austria. Under Hitler, Pfimpfe were boys between ten and fourteen, members of an organization leading to Hitlerjugend (an analog of “young pioneers” in communist regimes). Today, even Wikipedia has an entry on Pfimpfe, but in the past, no English etymologist knew the word, and in Germany, hardly any linguist heard the English word pimp. Therefore, no one compared them. German researchers guessed the origin of Pimpf without any trouble, even though the word surfaced in books late (they did not need the English cognate), while their English-speaking colleagues were puzzled by pimp and failed to offer an etymology.

Here then is the conclusion. Small things and small people are “pimps.” Growth in stature requires another grade of ablaut: the thing and the creature becomes a “pump” or a “pamp.” The progression i-a in English is well known: compare tic-tac-toe, tricktrack, pitter-patter, and dozens of others. A pimple is a tiny thing, unlike pomp and a pump. A pumpkin can of course be small, but ideally it is big and round. It appears that the pumpkin has a name it deserves, whether it graces our doors at Halloween or becomes part of a pumpkin pie.

Feature image by Karalina S via Unsplash

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers