Oxford University Press's Blog, page 87

January 15, 2022

Charlie Chaplin and the art of metamorphosis

Frogs that become princes; Lot’s wife turned into a pillar of salt; a host of Greek and Roman mythical characters transformed into spider, wolf, tree, rock, or what have you: ever since classical antiquity, astonishing transformations have been powerful vehicles of thought and feeling in folklore, myth, religion, and imaginative literature. And they continue to be so, from Kafka’s The Metamorphosis to Marie Darrieussecq’s novel Truismes, whose protagonist turns into a sow. In the movies, too, the theme plays an increasingly central role, not least in science fiction and fantasy, from The Fly to Terminator to countless werewolf films. But the doyen of all the moviemakers who have exploited the idea of transformation is Charlie Chaplin (CC).

Chaplin was certainly the greatest mime, probably the greatest actor, and arguably the greatest artist in any medium in the twentieth century. (Perhaps only Picasso runs him close.) As self-transformations go, his personal rags-to riches story is hard to match. But the theme of metamorphosis also permeates his movies.

In his definitive biography of Chaplin, David Robinson analysed CC’s use of “the comedy of transposition,” whereby objects seem to turn, consistently and irrepressibly, into other things, in virtue of the ways in which CC treats them. In The Pawnshop (1916), for example, Chaplin, as the pawnbroker’s assistant, has to value a clock brought in by a customer. First, as a doctor, he performs auscultation on the “patient” through a stethoscope. The clock then turns implicitly into a container of food, as Chaplin uses a can-opener to gain access, sniffs it, and finds the contents to be rancid. Morphing from chef to dentist, he extracts the contents with a pair of forceps, before sweeping the whole pile of debris into the customer’s hat, conveying with a shake of the head that this is a hopeless case.

In The Gold Rush (1925), the comedy of transposition is still in full flow, as when hunger-stricken CC boils and meticulously fillets his boot, converting it into a gourmet dish including a wishbone (bent nail), with spaghetti (shoe laces) on the side (the boot and laces were really made of liquorice—a third level of transposition). At another moment, Charlie performs the legendary “Dance of the Rolls,” in which two bread rolls impaled on forks assume the identity of balletic human feet. But metamorphosis can also be a pernicious delusion. In famine-induced delirium, his fellow prospector in the frozen wastes imagines Charlie as a colossal and eminently eatable chicken. This time the transformation is visual as well as mental, as CC’s gestures and costume enact his temporary change of species.

Even these flights of transformative fancy pale beside the achievement of City Lights (1931). In his role as the Tramp, CC meets a blind girl (played by Virginia Cherrill) who earns a living selling flowers. Learning that her sight can be restored if she can go to Vienna for an operation, the Tramp tries everything to get cash to pay for her trip. Finally, he renews acquaintance with a millionaire; the man is prone to bouts of maudlin drunkenness, during one of which Charlie had previously rescued him from a suicide bid. The millionaire gives the Tramp the money he needs, and the Tramp then hands it to the flower girl; but the episode coincides with a burglary on the millionaire’s house, for which the Tramp is wrongly arrested and jailed.

While CC is in prison, the girl has her operation; now, her sight restored, she runs her own flower shop. Her one thought is to meet and thank the benefactor who transformed her life, and whom she idealises as handsome and wealthy. After his release, the Tramp wanders the streets, down at heel but still resilient. Happening to pass the flower shop, he stares enraptured at the flower girl; when he smiles, she smiles back, with a mixture of amusement at his antics and pity for his scruffiness—whereas the Tramp has instantly recognised her, she, for her part, sees him as no more than a highly implausible admirer. When she offers him a coin and a flower, he first shuffles away in embarrassment, then hesitatingly returns to accept the gifts. As she presses the coin into his hand and strokes his skin, the sense of touch that she used to rely on leads her, gradually and heart-stoppingly, to recognise the man whose generosity restored her sight. ‘You?’, she asks. ‘You can see now?’, he replies. ‘Yes, I can see now.’

As the scene fades and the film ends, the audience has witnessed, during one minute of screen time, an unsurpassable distillation of multiple metamorphoses. For the Tramp, the way the girl initially looks at him reveals the change in her condition from blind to sighted; later, he witnesses her expression shifting from amused insouciance to astonished awareness. As for the girl herself, the wealthy aristocrat she has been yearning for morphs, at the moment of recognition, into a dirty, derelict vagabond. Yet, at the same moment, the down-and-out she sees before her is transformed into a selfless hero, to be admired and loved.

From the idea of metamorphosis profound questions may arise, regarding, for example, form and substance (the Christian Mass) or the boundaries of the human and non-human (Arachne and all the rest). But sometimes the mood is lighter, when human beings turn into other species with hilarious consequences (Aristophanes’ Birds and Wasps). Rarer still are cases of transformation where comedy and pathos magically merge (A Midsummer Night’s Dream). This is Chaplin’s realm, where uncontrollable laughter and unstaunchable tears cohabit. The film critic James Agee described the ending of City Lights as “the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.” He was, if anything, understating the case.

Feature image: The Tramp and the Blind Flower Girl, City Lights still, via Wikimedia Commons.

January 13, 2022

Recognizing the “other” ways of employee creativity in the workplace

For many years, the common understanding of employee creativity involves individuals generating new products and services for their organizations. We think of employee creativity when we think about the 3M engineer who invented post-it notes and the Zappos customer service representative who was empowered to take a creative route to deliver customer service. As illustrated by these examples, the conventional understanding of employee creativity focuses on novel products and solutions that allow individuals to deliver high performance for their organization.

Yet employees can also demonstrate creativity in other ways. Compared with the conventional type, these other “unorthodox” ways of employee creativity are less understood yet equally important for researchers who are interested in understanding creativity and innovation in organizations. In their popular book, The Ten Faces of Innovation, Tom Kelly and Jonathan Littman discussed the different personas needed for effective innovations. Somewhat parallel to this notion, recent research shows that there are also at least three “other” ways employees can exhibit creativity in the workplace:

1. Circumventing rules to meet a business needOne such way is to use creativity to circumvent rules in order to meet a business need. The commonly understood type of employee creativity is carried out within the parameters of organizational rules. In contrast, using original ways to circumvent rules is using creativity to stretch these parameters. A common example will be an employee who circumvents red tapes in a creative way in order to get his or her job done more efficiently.

2. Circumventing rules to satisfy a personal interestEmployees may also circumvent rules creatively in order to satisfy their personal interests. For example, a software developer uses a clever way to outsource work tasks to a third-party contractor so that he can do less work. Personal interests are not necessarily all self-serving. They can also involve helping a friend or a social group that an employee cares about. An example would be a minority employee using creative strategies to stretch rules to help other minority employees receive a fair chance for promotion.

3. Developing a solution to a personal problemIn addition, employees can develop a creative solution at work simply to solve a personal problem, and it is not against the existing organizational rules. For example, an IDEO employee came up with the idea of hanging up his bike on the ceiling as a way of storage. This type of creativity does not stretch rules. But it is also not generating new products for the organization.

These “other” ways of employee creativity differ from the common understanding of employee creativity in two aspects. For one, some of them involve creative ways of stretching organizational rules and regulations. For another, they are not always used to achieve organizational goals.

To various degrees, it is possible to find examples of such employee creativity in all organizations. Yet organizations with some cultures and managerial practices are more likely to have incidents like these than others. Employees with a certain value, belief, and relationship with their organizations are also more likely to engage in these types of creativity than others. For example, companies with outdated rules and low openness to change may place more employees in a position where they need to develop creative solutions to overcome restrictions and regulations. Employees with strong professional and social identities independent of their work affiliations are also more likely to enact creative behaviors at work to help another group or advance another cause.

“When we observe other ways of employee creativity, it becomes apparent that the employer is not always in the driving seat in determining how its employees use their creativity.”

When we observe these other ways of employee creativity, it becomes apparent that the organization (or the employer) is not always in the driving seat in determining how its employees use their creativity. Individual employees have a great degree of agency (i.e., autonomy, latitude) in deciding where and how to use their creative ideas. Some of these creative ideas may benefit the organization directly and indirectly; some may not be directly relevant; some may lead to negative consequences for the company. Some of these creative ideas may inspire changes in the culture and policies of an organization in the future. Some may remain in the action domain of organizational life—that is, they are being done but not said.

Unlike the type of employee innovation commonly studied by researchers, these types of creativity are “informal” innovative acts in an organization. In a sense, these employees acted as entrepreneurs within their organization; they orchestrated their intelligence and creativity to enact changes with or without official permission. When employees use creativity to generate a product or service for the organization, their creativity often leads to a change in some aspects of the business operation. In contrast, these “other” types of employee creativity can also influence organizational rules, policies, and culture. They may be less visible, and some of them unrewarded, but are equally powerful in changing how a business operates, how employees experience their organizational life, and how customers and society experience a company.

Does this understanding bring good or bad news for managers? The answer is perhaps both. The existence of these “other” ways of employee creativity indicates that employees have much creative potential to offer. Yet it also suggests that employees’ creative potential is not used in ways that are fully aligned with the innovation objectives of an organization. This layer of understanding invites managers to attend to these other facets of the innovators in their organization. As such, it opens up possibilities for communication, reflection, and potential integrations with formal channels of innovation.

January 12, 2022

After a sun eclipse: bedposts and curtains in sex life and warfare

A bedpost, unlike star, ice, snow, and a host of other riddle-ridden words, looks perfectly unexciting. But the situation becomes attractive, even thrilling if you ask a question about the origin of the phrase in a twinkling of a bedpost/bedstaff. Since I have written passionate essays about stars and called one of them “Twinkle, twinkle, little star,” I cannot pass by another twinkling body. This discussion will, most probably, be the last in my astronomical series. I wanted to write an essay about sun, but nothing came of my idea. The phonetics and the morphology of the words for “sun” in Indo-European have been discussed in minute detail, mainly because they belong to an archaic declension in which l alternates with n (compare Engl. sun versus the apparently related Latin sōl), but no one knows how this most important word acquired its meaning.

The sun moves, sheds its light, brings warmth, and does other things that make life possible. Which of those multiple blessings did people choose for naming it? The sun was revered, as the existence of many a divinity like Helios testifies. The noun designating sun was sometimes masculine and sometimes feminine. In Germanic, the word for “sun” has at least one synonym. All this is very instructive but tells us nothing about etymology in the only sense that interests us here: if the most ancient root sounded approximately swa’l, what did it refer to? On consideration, I decided to leave the sun alone and stay in bed. Hence this post about a post.

In a twinkling of a bedpostThe phrase in a/the twinkling of a bedpost (with the archaic variant bedstaff) means the same as in a twinkling of an eye, that is, “very quickly,” because twinkle, when used metaphorically, refers to a rapid movement. Agreed: eyes and stars twinkle, but bedposts don’t, and here is the rub. In my prospective dictionary of idioms, three lines are devoted to this phrase, and the OED of course lists it (the earliest citation there goes back to 1660). Yet the most interesting part is to follow people’s attempts to make sense of what looks like obvious nonsense. For starters, consult E. Cobham Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, the entry bedpost. Just search for it on the Internet.

An old bed with pretty formidable bedposts.

An old bed with pretty formidable bedposts.(Peckover House & Garden, Cambridgeshire, England, via Wikimedia Commons)

My bibliography of this phrase spans the period between 1852 and 1905. The first correspondent (the source is, as always, the inestimable periodical Notes and Queries) wrote:

“It is generally supposed to have been a staff or round piece of wood, fixed by the side of a bedside to keep the bed in its place. If this were the case, it must have been at least six feet long, and strong enough to bear the weight of anyone leaning against it. But how can this be when we find it used by Bobadil, in Every Man in his Humour, to exhibit his skill with the rapier? Such a pole might have been used to show what could be done with a pike or spear; but it seems impossible that a staff as tall as a man’s self and as thick as his wrist, could have elucidated the lightning-like passes of the small sword.”

(Captain Bobadil, a despicable braggart, is the protagonist in one of Ben Jonson’s best-remembered play, mentioned above. Incidentally, all the correspondents wrote Johnson.)

Four years later, another correspondent referred to Thomas Wright’s book Domestic Manners and Sentiments of the Middle Ages:

“Here we see the chambermaid in the seventeenth century making use of a staff to beat up the bedding, in the process of making the bed. The rapid use of this implement would quite give the idea of twinkling. … The change from bedstaff to bedpost, is no doubt, recent. Horace Walpole [1717-1797] uses the former word.”

Very interesting, but twinkling? And what about Bobadil’s martial artis?

Yet the same idea occurred to a nineteenth-century observer:

“Anyone who has resided in Glasgow, or other Scotch town, and has enjoyed the luxury of a room with a window overlooking ‘a green’ … will easily understand the meaning of the above sentence. The Scotch servant lassies display such agility or elasticity of wrist in the dusting of beds, carpets, et hoc omne [‘and all this’; they did love displaying their knowledge of Latin, driven into them most firmly, as Mowgli’s friend Bagheera might put it] that the staves or sticks they use can hardly be seen while in motion, though the noise of the blows given with them, with the perpetual rap-rap-rap, can be compared to nothing so well as to the action of steam machinery.”

Enjoy the best of Scottish hospitality.

Enjoy the best of Scottish hospitality.(Bedroom, Provost Skene’s House, © Copyright Richard Sutcliffe, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Now back to the seventeenth century. In a 1639 book, we see a woman approaching her drunken husband, who is in bed. She has a ladle in her hand, and he clutches:

“in one hand a heavy shoe, while the upreared right grasps the bed-staff as a foil to protect his head… This presumed ‘bed-staff’ of my plate answers to Jonson’s general description of a pin and is an implement of wood of damaging capability and, hurled through the air by a powerful arm, it would certainly reach the head of an offending party in a twinkling.”

Very true, but were bedposts ever constructed or meant by their designers as weapon?

Curtain lecture An ideal space for a lecture.

An ideal space for a lecture.(Van Loon House, Amsterdam, via Flickr.)

Twinkle, twinkle, little bedpost! Perhaps some light on the situation will come from the idiom curtain lecture. Strangely, it originated at about the same time as the one about the bedpost (OED: 1633). According to a letter, this time in American Notes and Queries:

“a curtain lecture is a scolding given a husband by his wife and is so called from the curtained bed in which such a lecture might take place. … [This is common knowledge but read on!] In 1637 Thomas Heywood published A Curtaine Lecture, composed of several short tales about shrewish wives’ mistreatment of their husbands. The use of the term and depictions of curtain lecturers continued up through the 19th century in plays, novels, and essays.”

The Century Dictionary quotes Dryden and Addison. “What endless brawls by wives are bred! / The curtain-lecture makes a mournful bed.” “She ought, in such cases, to exert the authority of the curtain lecture, and if she finds him of a rebellious disposition, to tame him.” And the OED quotes Thackery.

We seem to be witnessing a well-developed culture of violent quarrels in bed! The idioms are typical of the Elizabethan and the post-Elizabethan epochs, and one wonders why no allusions to them appear in Shakespeare’s comedies. Perhaps there were puppet shows or ballads that immortalized those odd expressions? Pull devil, pull baker has this origin (see the post for 20 May 2020: “’The devil to pay’ and more devilry”). Just guessing.

So much for marital bliss and conjugal felicity about 400 years ago. A twinkle in your eye, ladies and gentlemen!

Feature image: Architrave with sculpted metope showing sun god Helios in a quadriga; from temple of Athena at Troy, ca 300-280 BCE; Altes Museum, Berlin, via Wikimedia Commons.

January 11, 2022

Beyond “Copaganda”: Hollywood’s offscreen relationship with the police

Do Hollywood’s portrayals of policing matter as much as the industry’s material entwinement with law enforcement—as much as the working relationships pursued beyond the screen?

Instead of conceding that the consumers of popular media are eminently capable of thinking for themselves (and thus of resisting flattering depictions of power), more and more commentators are calling for the complete elimination of cop shows, cinematic police chases, and other, ostensibly entertaining images of law enforcement. In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, the journalist Alyssa Rosenberg, writing in the Washington Post, called on Hollywood to “immediately halt production on cop shows and movies.” “Like policing itself,” tweeted the journalist and academic Steven Thrasher earlier this year, “copaganda”—a popular neologism describing the perceived capacity of screen representations to promote law enforcement—“must be abolished. It can’t be reformed.” For Thrasher, any representation of policing simply “blunts our imagination.”

Never mind that media scholars have, since at least the 1970s, insisted that film and television do not necessarily determine human behavior, whatever our moral opposition to simulated bloodlettings and other odious scenes. Today, proclaiming that commercial entertainment strictly dictates our emotional as well as political responses is very much in vogue, as anyone who consults social networking services can readily attest. Get rid of “cop content,” goes the Twitter-friendly premise, and you will immediately weaken the power of public police departments. Without popular media telling Americans to admire law enforcement, such departments will lose the fuel they need in order to promote social inequality. They will be starved of “prestige,” forfeit the eyes and ears of the polity, and wither away as a result.

Yet representation is not, of course, the whole story, and the disproportionate attention that it receives surely distracts from other avenues through which popular media empower and expand law enforcement in the United States. Those who proudly peddle the censorial argument would do well to ask themselves why, for instance, corporate giants have been so swift to consent to it, banning certain long-running programs, publicly apologizing for others, and generally appearing to accede to the Twittersphere. Today, those giants have as vested an interest in superficially responding to calls for social justice as they have in pursuing unchecked corporate power behind the scenes. Cops can be cancelled without much risk to the Paramount Network’s bottom line. But Viacom’s holdings are vast, materialized everywhere from the iconic Paramount Pictures studio lot in Los Angeles to corporate offices in Manhattan. Media are more than just sounds and images, messages and artistry; they are also real estate—privately owned properties that depend on public as well as private police forces for their protection, and that, as concentrations of capital, only contribute to the social inequalities so frequently at the center of collisions between cops and citizens. Whether Warner Bros. depicts “good cops” or “bad cops” on screens big and small does not, after all, affect its capacity to retain immense power over labor.

Hollywood’s intimacy with public policing is longstanding, as Rosenberg and others have shown. Yet that relationship has not been nearly as smooth or as consistent as is generally assumed; it is not reducible to the synergetic Dragnet. Police censorship of motion pictures was, as early as the first decade of the twentieth century, an object of growing public disdain, and it spoke to a tension—or paradox—at the heart of Tinseltown’s intersections with the cops: in several states, and for over five decades, police officers were empowered to ban or re-edit costly productions, even as they worked as paid advisors to movie companies. As Hollywood learned early on, the vast discretionary powers of public policing could turn on a dime; in the industry’s favor one day, those powers could mobilize against it the next.

Today, banning the representation of policing—offering no images of cops whatsoever—is considered, by some, one possible solution to the conundrum, a way of ensuring that police departments cannot use movies and television programs for propaganda and recruitment purposes. Yet this extreme dispensation, with its promise of radical change, invokes an even broader form of social engineering—a way of remaking our minds so that we may perceive, through a certain sanitization of media, a world without cops, as if our imaginative faculties were somehow lacking on their own, our morals desperately in need of blinkers. “There is a world of stories beyond cop stories,” Thrasher has assured his readers, and until we eliminate all representations of law enforcement, policing will surely be “perceived as a necessity via Hollywood”. Such a simplistic position, which implies a passive mass audience, also ignores policing’s capacity to appropriate unexpected cultural products—to mine the movies for anything of value.

For example, John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), one of the most cynical of all American films—an exploration of humans’ capacity for greed and brutality, made by a liberal who was himself critical of the police (one writer called him “an anti-authoritarian cop-hater”), and not at all a “cop story”—was nevertheless generative for law enforcement. Some sixty years after its initial release, the film in fact inspired “Operating Stinking Badges,” a joint federal-city policing policy that criminalized, among other offenses, the possession of counterfeit police gear. Named after a famous line (“I don’t have to show you any stinking badges!”) uttered in the film by a Mexican bandit bent on impersonating an officer of the law, Operation Stinking Badges was challenged in 2010 by a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of those arrested, incarcerated, and prosecuted under the policy, which empowered all manner of police personnel to determine, at a glance, exactly what articles of clothing or modes of comportment constituted imitation. The plaintiffs noted that this post-9/11 security measure—the brainchild of Homeland Security and the NYPD—traded on the fame of Huston’s celebrated film, and thus lent the violation of civil liberties a certain Hollywood panache bound to appeal to the general public. A federal judge in Manhattan eventually ruled that the suit, which alleged widespread violations of First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights, lacked merit, and the federal appeals court agreed, upholding the constitutionality of a policy partly inspired by a Hollywood movie in which no American cop actually appears.

Today the conglomerated makers of popular media have also learned to appease certain protestors, who might look away as soon as a show is cancelled or a film’s production suspended—or, for that matter, cheer the contemptuous representation of “bad” cops. The latter are central to Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success (1957), which accordingly received positive attention from various anti-carceral factions—and negative attention from conservative commentators who felt that its defamatory portrayal of the NYPD was practically Soviet propaganda. Amid these debates about representation, however, the NYPD was busy expanding its special “youth squad”—recently formed to “control the fanatical fans of James Dean” (and increase drug arrests)—in order to police the film’s premiere, as it had policed the film’s production on location in “unruly” Manhattan. The independent companies behind Sweet Smell of Success (including that of liberal icon Burt Lancaster) cut costs by relying on the NYPD, which used its own resources to assist the shoot—a siphoning of public monies away from the public and toward private enterprise, a process that we do not necessarily see on the screen, that we cannot necessarily discern through attention to cinematic style alone, and that will scarcely cease once “cop stories” are banned.

Even earlier, on the opposite coast, the LAPD consented to certain “negative” representations of policing while its members, addressing closed Congressional hearings, testified to the Communist Party’s penetration of Hollywood studios. Liberal moviegoers might have been relieved to see defiantly anti-carceral films like MGM’s Faithless (1932), in which a beat cop, discussing alternatives to policing with Tallulah Bankhead’s desperate sex worker, decides not to arrest the woman but to find her a job as a waitress instead. What happened offscreen, however, was of far more consequence, both to the industry and to its audiences. Nearly four hundred miles north of the MGM lot, the Sacramento Police Department, which had a special anticommunist squad, claimed to have found evidence of the Communist affiliations of the Mexican-born Hollywood stars Lupe Vélez, Dolores del Río, and Ramón Novarro, who all faced deportation as a result—a cop-initiated harbinger of McCarthyism, which would, of course, offer its own prescriptions for “fixing” popular media and allowing audiences to imagine a world without communism. Produced during the Depression, Faithless directly depicts what many of today’s left-leaning activists would like to see—namely, the displacement of mass incarceration by a jobs guarantee. But the film’s representational turn to the left could in no way guarantee protection for actual leftists.

What else might we miss by brooding over representation—by what does or does not show up on the screen? Today, we need not pretend that massive entertainment companies are ever on the side of social justice, or that, by micromanaging the stories they tell, we can somehow control their material and ideological ties to police departments. A high-profile cancellation (like that of Cops or Live PD) can be celebrated in a tweet about the sanitization of our screens. What happens behind those screens, however, may be harder to identify—and thus to oppose. It’s a bigger story than some would like to concede. Indeed, Hollywood’s long, jagged history of encounters with public policing has much to teach us about the lives of institutions—and individuals—under capitalism.

Feature image: Police car belonging to the US Secret Service Uniformed Division patrols in Washington, DC. Photo by Matt Popovich, public domain via Unsplash.

January 10, 2022

The tree of life and the table of the elements

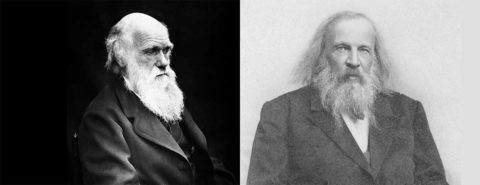

Darwin’s tree of life and Mendeleev’s periodic table of the elements share a number of interesting parallels, the most meaningful of which lie in the central role that each plays in its respective domain.

Darwin’s tree of life, incidentally the only diagram of which appears in his book The Origin of Species, is a sketch of the central idea that all animal species have a common descent, much like members of an extended family can be displayed on a genealogical tree. Mendeleev’s periodic table is likewise the central icon for chemistry and serves to summarize and classify all the elements, the ways in which they show similarities among themselves, and how they react and bond with other elements.

Even more importantly, perhaps, is the fact that almost all subsequent developments in biology and chemistry can be seen as attempts to flesh out the ideas of Darwin and Mendeleev, respectively, and to provide an explanatory mechanism for their discoveries in each case. The parallel developments of the fields of evolutionary biology and modern chemistry illustrate the way that scientific discoveries begin as observations and systematizations and eventually lead to detailed explanatory theories that feature newly discovered scientific entities—such as the DNA molecule in 1953, in the case of biological evolution, and the electron in 1897, explaining the grouping of the chemical elements. The overall nature of the process appears to be largely the same, irrespective of the details of the particular branch of science in question.

Establishing the theoriesThe tree of lifeEvolution was in the air long before Darwin. His grandfather, Erasmus, mused about evolution in his book Zoonomia 1794 and 1796, while Lamarck presented a formal theory of evolution in 1801. The anonymously authored and widely read “Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation”, first published in 1844, speculated on the transmutation of species. None of these precedents truly anticipated Darwin, but all showed that evolution was on peoples’ minds.

Alfred Russell Wallace was the only substantive rival to Darwin’s priority and who clearly defined natural selection as the mechanism that causes evolution in his 1858 essay. Like Darwin, he invokes Malthus’ essay on population growth, Spencer on the “struggle for existence” as the ultimate brake on population growth, and the selective survival of individuals better suited to the struggle as the ultimate cause of evolution. He invokes the “tree of life” as a conceptual model for how life diversifies over time and abstracts Darwin’s argument that the fossil record and the distribution of living organisms preserve the history of how life changed over time and space. However, it seems Wallace’s essay was too brief to make a strong impression.

More to the point, the impact of the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859 was like a tidal wave that swept away all that came before it. Darwin’s book was more than 20 times longer than the combined length of Wallace’s earlier essays. With that length came an argument that was far more wide-ranging, comprehensive, and convincing. Wallace’s essays were suggestive, but Darwin’s book was a complete argument for evolution as the unifying concept for all of the life sciences.

The periodic table of elementsMendeleev’s great discovery of the periodic table was presented to the world in 1869 at a meeting of the recently formed Russian Chemical Society. Like Darwin, Mendeleev also wrote a very influential book, The Principles of Chemistry, which helped to propagate his ideas further afield. As in the case of most scientific discoveries, many other scientists—such as De Chancourtois, Newlands, and Lothar Meyer—had arrived at earlier precursors to the periodic table of the elements but none of them achieved the kind of lasting success that Mendeleev did.

This fact is generally believed to be due to a number of successful predictions that Mendeleev made about the existence of new elements that were eventually discovered and that had almost exactly the properties that Mendeleev had foreseen. Even in his first published table of 1869, Mendeleev clearly predicted the existence of three new elements, which he stated would have atomic weights of 44, 68, and 72, respectively. Within a period of 15 years all three of these elements—subsequently named gallium, germanium, and scandium—were indeed discovered and found to have atomic weights of 44, 69.2, and 72.3. Mendeleev’s theory provided genuine predictions in the temporal sense and numerous retrodictions or rationalizations of already known chemical facts.

Challenges to the theoriesIt is also interesting to examine how the tree of life and the table of the elements faced a number of challenges during their 150 year-plus development.

The tree of lifeDarwin convinced a critical mass of people that evolution was real, but not that natural selection caused evolution. Natural selection requires laws of inheritance and Darwin’s conceptual model of inheritance was wrong. Darwin invoked artificial selection as an explanation for how inheritance and evolution work. In his review of the Origin, Fleeming Jenkin, an engineer from the University of Edinburgh, proved with a mathematical model that artificial selection and “blending inheritance” could not produce evolution.

Mendel’s laws of inheritance appeared in 1865, between the publication of the first and last editions of the Origin, but Darwin never learned of his work. These laws would ultimately redeem Darwin but when they were re-discovered in 1900, they were used against him. It was not until the 1930s that Mendelian inheritance, in which copies of genes can skip a generation and reappear unchanged, was reconciled with natural selection and Darwin’s concept of inheritance.

Given these objections, why was Darwin ultimately successful? The success of any theory is determined by how well it accommodates and integrates available knowledge and its ability to make predictions. Darwin’s near-term success was dominated by accommodation, or his unification of the life sciences under a single explanatory framework.

The periodic table of elementsJust like Darwin’s theory of common descent, Mendeleev’s table faced a number of challenges but none of them seem to have been as serious as those faced by Darwin.

One of the first hurdles that Mendeleev’s system had to overcome was the fact that ordering the elements according to their increasing atomic weight, as he did, resulted in two pair reversals. For example, the element iodine has a lower atomic weight than that of tellurium, which would lead one to think that iodine should be placed before tellurium along one of the rows of the table. But doing so would be chemically inconsistent; the elements must be “reversed” if the table is to make chemical sense. The discoverers of the periodic table, Mendeleev included, made the required reversal because they were primarily interested in chemical similarities rather than upholding the notion of strictly increasing atomic weights. Mendeleev was even bolder in that he believed that the then-known atomic weights of one or both of these elements were mistaken. In the case of this prediction, Mendeleev was later shown to be incorrect by the English physicist Henry Moseley who discovered that the elements are ordered more effectively on the basis of their nuclear charges (or atomic number) rather than their weights.

A second challenge erupted in the year 1894 when a new and highly unreactive gas named argon was isolated by William Ramsay and colleagues at University College in London. Placing this new element into the periodic table was made especially difficult because its atomic weight was 40 and another element, namely calcium, already existed with precisely the same atomic weight. Mendeleev tried to meet the challenge by claiming that the new gas consisted of a triatomic nitrogen molecule. Here, too, Mendeleev was shown to be mistaken. After five years of much controversy regarding the status of argon, Ramsey himself realized that a new column could be added to the right-hand edge of the periodic table to house neon, as well as a number of other noble gases that were discovered in his laboratory in rapid succession.

The periodic table escaped being refuted and indeed was strengthened by the realization that it was capable of accommodating these new elements successfully. Mendeleev, never one to shy away from proclaiming his achievements, was among the first to embrace Ramsay’s newly created group of elements.

DifferencesThere are clearly similarities but also substantial differences between the case of Darwin’s tree and Mendeleev’s table. One is surely that Darwin’s theory concerns diachronic changes, meaning those that occur across time while the periodic table is of the synchronic type, in that the elements do not evolve over the time period over which they are being compared in modern chemistry. Even more obviously, perhaps, biological systems are orders of magnitude more complex than atoms are and subsequently their behavior is, not surprisingly, less predictable. In the same way, theories concerning biological systems are expected to be more controversial and more subject to internal challenges than is the case of chemical systems.

Rather interestingly, the elements themselves are believed to all have evolved from the first or primordial element of hydrogen which has just one proton and one neutron, somewhat analogously to a single-celled organism in the biological realm. However, the evolution of the elements of this kind has taken place over many millions of years and requires gargantuan energies that in most cases can only occur at the center of massive stars or in the course of a supernova explosion.

Finally, whereas we have classified Darwin’s discovery as a theory, this is not the case for the periodic table. Instead the periodic table is more akin to an uninterpreted classification scheme for the elements that is in need of a theoretical explanation, and one that was duly provided by the development of quantum mechanics in the 20th century.

Darwin’s tree and Mendeleev’s table represent momentous discoveries which continue to drive the development of modern biology and chemistry respectively. Surprisingly, perhaps, the more fundamental science of physics seems to lack any such iconic and all-encompassing unifying motif.

Featured image: Photo of Mendeleev from Wikimedia Commons; Photo of Charles Darwin also from Wikimedia Commons.

January 9, 2022

Getting English under control

Any large organization or bureaucracy is likely to have a style guide for its internal documents, publications, and web presence. Such guides tell which logos to use, what to capitalize, whether to use spaces in certain compounds and periods in abbreviations, when to spell out numbers, and so on. Some organizations go a step further and develop what is known as a control (or sometimes controlled) language: a prescribed, simplified vocabulary and grammar for use in official documents. A control language aims to make technical English (or another language) consistent and easily understood. The idea is reign in variation to limit what can go wrong.

I was browsing through the 2014 Microsoft Manual of Style, which is a hybrid: part style guide and part control language manual. In a long-ago blog post, the linguist Arnold Zwicky pointed out a bit of clumsy advice about the word once from a 1995 edition of the Microsoft Manual: “To avoid ambiguity, do not use [once] as a synonym for after.” Microsoft’s editors illustrated this with the usage labels Correct and Incorrect:

Correct

After you save the document, you can quit the program.

Incorrect

Once you save the document, you can quit the program.

Microsoft must have gotten some correction itself, because by the 2012 fourth edition, the intent was clarified and the usage labels made more specific:

To avoid ambiguity, especially for an international audience, do not use [once] as a synonym for after.

Microsoft Style

After you save the document, you can quit the program.

Not Microsoft Style

Once you save the document, you can quit the program.

In ordinary English, once can mean after. Microsoft’s worry seems to be that the meaning might be confused with the once-upon-a-time meaning or the a-single-time meaning. The point was not a matter of grammatical correctness, which is a fraught notion in any case. Rather it was intended to facilitate translation and understanding of technical materials.

Companies often develop their own control languages, like Caterpillar Technical English, General Motors Global English, or Boeing Technical English. You can find a fairly comprehensive list in Tobias Kuhn’s “A Survey and Classification of Controlled Natural Languages,” which appeared in the journal Computational Linguistics in 2014. Comprehensibility across cultures and languages is also the idea behind Aviation English and Seaspeak, and these might be considered control languages as well.

Guides like the Microsoft Manual, the Apple Style Guide, and the IBM Style Guide define a style somewhere between plain language and simplified arbitrariness. Sometimes the advice seems to come from past experience:

discreet vs. discrete Be sure to use these words correctly. Discreet means “showing good judgement” or “modest.” Discrete means “separate” or distinct” and is more likely to appear in technical content.

Sometimes the advice is idiosyncratic:

ad hoc Do not use ad hoc unless you have no other choice.

Sometimes the advice sacrifices common usage in favor of minimalism:

while Use only to refer to something occurring in time. Do not use as a synonym for although or whereas.

choose Use choose when the user must make a decision, as opposed to selecting (not picking) an item from a list to carry out a decision already made.

Sometime the advice is diplomatic:

collaborate, collaboration, collaborator It is all right to use collaborate or collaboration to refer to two or more people who are working on a shared document. However, do not use collaborator to describe a worker in such an environment unless you have no other choice. Collaborator is a sensitive term in some countries. Therefore, use a synonym such as colleague or coworker instead.

And sometimes the advice is even ironic:

bluescreen Do not use blue screen or bluescreen, either as a noun or as a verb, to refer to an operating system that is not responding. As a verb use stop instead. And as a noun, use stop error.

malicious code: Do not use. See malware, malicious software, security.

The next time you run across a corporate style guide, take some time to browse for bits of control language. It will give you a new perspective on style.

Feature image: “Building 92 at Microsoft Corporation headquarters in Redmond, Washington” by Coolcaesar. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

January 6, 2022

Britain’s long struggle with corruption

Corruption has risen to the top of the British political agenda. There have been scandals over crony covid contracts, cash for peerages, and the lobbying and consultancy activity of MPs. The rules governing MPs’ conduct, and the committee set up to oversee them, have been challenged, ripped up, and then restored. According to one poll published in the Independent, three quarters of the public are concerned about government corruption. The Prime Minister, himself under fire for dubious standards, felt it necessary to tell the leaders gathered for the COP26 meeting in November 2021 that the UK is “not remotely a corrupt country.”

But even if we agree with Boris Johnson (and that is something of an open question), then Britain certainly did struggle with corruption in the past. Indeed it has had a long history of corruption and anti-corruption. This has some lessons for today.

It took several hundred years for Britain to move away from a society in which officials felt little responsibility to the public and often regarded their posts as private property from which they could personally profit. It took many experiments with public accounts committees, from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, before a reasonably robust system to scrutinise public expenditure was put in place by the mid-nineteenth century. Similarly, although there was some legislation in 1555 to ban the sale of judicial and revenue posts, it was only in 1809 that the sale of office more generally was banned and, even then, army commissions continued to be sold until 1871. It took many prosecutions of officials to drive home the distinction between their own money and the public’s money. In the early nineteenth century, magistrates such as the notorious Joseph Merceron, who dominated Bethnal Green in the east end of London, were still able to use their positions to run rackets.

A detail (with anti-semitic overtones) from a satire of 1810 depicting the “Monster of Corruption” whose “hands of extortion” grasp a “bag of bribery” with an “eye to [his own] interest.”

A detail (with anti-semitic overtones) from a satire of 1810 depicting the “Monster of Corruption” whose “hands of extortion” grasp a “bag of bribery” with an “eye to [his own] interest.” Photograph of Mark Knights’ owned print, ‘A Rough Sketch of the Times’ (1819)’, from The British Museum.

Gradually, uncertainly, unevenly, patchily, and over a long time, however, measures were put in place to define the boundaries between private and public interests, and to define what counted as the abuse of office. An important legal case was heard in 1783, when the accountant Charles Bembridge was prosecuted for concealing false accounts (£48,000—the equivalent of £4 million in today’s money—was missing!). The verdict against him helped to establish both the definition of public office (it included anyone being paid to do the work of the state, even if they were not formally employed by it) and the abuse of office (if an official knowingly concealed a fraud on the public, he was criminally answerable for it).

The case also underlined that an office was a trust, a concept that originated in the 1640s when parliamentarians distrusted the king and his advisers. The idea of entrusted power had a long legacy. Even today, Transparency International, the leading anti-corruption lobbying organisation, defines corruption as the “abuse of entrusted power for private gain.” A trust carried a legal duty to act disinterestedly, with care and honesty, and to properly account for how money was spent. It was a legal ideal which carried duties of integrity, selflessness, accountability and transparency (today embodied in the Nolan principles).

The notion of entrusted power was adopted not just in Britain but across its empire. Indeed, one of the important ways in which domestic ideas about probity in office developed was in response to repeated scandals in the imperial sphere. The East India Company, in particular, generated numerous scandals that reverberated back home and helped to shape attitudes.

The reasons for the slow pace of reform are nevertheless instructive, since some of the same factors persist today. Socio-cultural factors blunted and limited the progress of the notion of office as a public trust. Friendship, patronage, kinship, and a culture of gift-giving all blurred the boundaries between the public and private. Anti-corruption became highly politicised, often more intent on taking out rivals than in reforming the system.

Governments also had a deep suspicion of informal accountability in the shape of the press and whistle-blowers. Judges determined that almost any criticism of public officials was libellous, even if the allegation was true. And press freedom remained controversial long after it had officially been gained in 1695, not least in the empire, as India and South Africa in the first decades of the nineteenth century highlighted all too clearly. Yet the informal accountability of public discussion and a measured distrust of officials’ claims for secrecy and protection were necessary parts of the anti-corruption mix.

So, Britain has had a long struggle with corruption and the measures put in place to curb it were very hard-won over a protracted period of time. We weaken or abandon them now at our peril.

Featured image: public domain via Pixabay.

January 5, 2022

The scars of old stars

The Oxford Etymologist is coming out of hibernation and picks up where he left off in mid-December. It may be profitable to return to the origin of star, but from a somewhat broader perspective. In the comments, the question was asked about what impulses could motivate our remote ancestors to coin the word under discussion, and I was instructed to use Greek as my loadstar. Before coming to the point, I should say that I am truly grateful for the comments. Those were scarce in the year we saw off less than a week ago. Yet readers’ remarks, however acerbic, are always welcome (in the post, I even managed to miss a letter in Russian zvezda; the typo has been corrected without acknowledging the reader’s input, and I hasten to make redress now, almost a month later).

First of all, we should ask ourselves about the nature and habits of the “primitive people” to whom we ascribe the creation of language and the words we use. Let us begin at the beginning (a sensible recommendation in all cases). Next to nothing is known about the origin of language. What do we want to reconstruct? The most primitive syntax? The “first” words? The system of vowels, consonants, and intonations sufficient for producing a statement or a question? About a century ago, it was suggested that the Aranda language (Australia) had only one vowel. Some enthusiasts concluded that such had been the beginning of human language. I am not sure too many linguists still endorse that hypothesis.

Are we looking into his speech habits?

Are we looking into his speech habits?Image: Homo heidelbergensis – forensic facial reconstruction, via Wikimedia Commons

Were words coined as isolated signals or as part of a coherent message? Unfortunately, we have relatively little to learn from children’s ways of mastering language, because they acquire language skills from us, adults, though the way their phonetic system develops (and the way the phonetic system disintegrates in progressive aphasia) may perhaps give us some clues to the evolution of language. On another note, can we learn anything from the signals used by primates or by dolphins? Dolphins loom large in books on the origin of language. Talented chimps have also been celebrated more than once.

Let us turn to “the first words” in the spirit of Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories. Our ancestors used some primordial cries to accompany their actions, for otherwise, language would not have evolved. What were those cries, or, rather, what can we know about them? The oldest recorded Indo-European languages (Hittite, Tocharian, Sanskrit, Greek, Gothic) had a ramified system of endings. Their grammar and vocabulary are a nightmare for students, but the native speakers did not complain! The Danish linguist Otto Jespersen formulated a theory, according to which “progress in language” (his term) means simplification. He cited English as his ideal: almost no morphology left (I spoke, he/she/we/they spoke, and so forth). Jespersen’s idea is an illusion. English has little morphology left but watch its rigid syntax and constructions like would have been waiting, with three auxiliary verbs and the ending –ing!

In Eastern Siberia, on the banks of the Yenisei River, two tribes of the Kets live, but their settlements are hundreds of miles apart and the dialects are not mutually understandable. Some living conditions found among the Kets were primitive indeed, and yet few more complicated grammatical systems than in Ket exist anywhere in the world. During WWII, Stalin had all the Russian Germans deported, and many of them ended up in Eastern Siberia. Some specialists managed to survive. A group of outstanding researchers described the Ket language, and later other linguists joined them. The Ket experience shows that primitive economy has nothing to do with the complexity of the speakers’ language or the length of their words. Anyone who would compare Latin and Italian will come to the same conclusion.

The Yenisei in its full glory.

The Yenisei in its full glory.In the nineteenth century, the first dictionary of Indo-European roots was put together. Those were abstracted from recorded forms, but many people believe that such roots are the cells from which word developed. The most recent dictionary of roots (by Julius Pokorny,1887-1970, a revised version of the work by Walde-Pokorny) is more reliable than the old one by August Fick, 1833-1916, but the principle behind it remains the same. The roots are not the nuclear words of human beings.

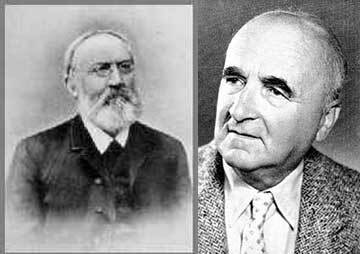

August Fick and Julius Pokorny

August Fick and Julius PokornyWe are unable to bridge the gap between modern languages and the speech of “primitive man” and can only rely on the longevity of some basic impulses. That is why sound-symbolic and sound-imitative words, often celebrated in this blog, are so instructive: the motivation behind word creation has probably not changed too much since the beginning of time (compare my constant references to the works of Wilhelm Oehl). Classical Greek ástēr means “star.” Can anyone seriously believe that this is a “primitive” word? Indeed, it can be understood as “not on the earth.” This form is millennia away from what people once said while watching the sky. The Greek noun might even be a late product of folk etymology! I’ll ignore the hard questions about whether the Semitic lookalikes are the source of the Indo-European form. Let us suppose that the Indo-European word is native. When it was coined, it was probably simplicity itself. Greek, including Homeric Greek, is an inestimable source for reconstructing the early stages of Indo-European but not of the beginning of human speech.

That is why I was impressed by the hypothesis that Russian iskra “spark” and star were in some way related. Those intangible and indefinable primitive people (the strawmen of naïve language historians and daring etymologists) were closer to nature than we are. That much is certain. They saw distant stars strewing light from above, believed in the influence of those bodies on their lives, and, not improbably, called the celestial bodies STR- or SKR- (both consonant groups are among the most common ones in forming words for streaming, strewing, scaring, and so forth).

If it is true that people coin words motivated by emotional impulses, the best laboratory for a language historian is slang. Thousands of “funny” words fill our speech, and new ones appear all the time. They were not coined millennia ago, and yet their origin is almost always unknown! Just look them up in dictionaries. Try scrumptious, and at best you will be told that this is a facetious alteration of sumptuous. Not an unreasonable hypothesis: scr– will make any word sound impressive. Sumptuous means “first-class, splendid,” but what is scrumptious is doubly impressive.

Sumptuous! Scrumptious!

Sumptuous! Scrumptious!(Photo by Anna Frodesiak, via Wikimedia Commons)

We’ll probably never know for sure how the word star originated, but that star was certainly not born in Greece, even though the name looks transparent. Etymology and all linguistics are part of the humanities. They are unlike rocket science or microbiology, but it does not mean that anyone armed only with the knowledge of an old language can solve riddles by merely looking at a word. There is method in etymology, as in some other sane things.

Feature image by Kristopher Roller on Unsplash

December 30, 2021

The top 10 religion blog posts in 2021

In 2021, our authors published new research, analysis, and insights into topics ranging from religious tolerance to taboo, atheist stereotypes to the appeal of religious politics, and much more. Read our top 10 blog posts of the year from the Press’ authors featured in our Religion Archive on the OUPblog:

1. Stereotypes of atheist scientists need to be dispelled before trust in science erodesCoping with a global pandemic has laid bare the need for public trust in science. And there is good news and bad news when it comes to how likely the public is to trust science. Our work over the past ten years reveals that the public trusts science and that religious people seem to trust science as much as non-religious people. Yet, public trust in scientists as a people group is eroding in dangerous ways. And for certain groups who are particularly unlikely to trust scientists, the belief that all scientists are loud, anti-religious atheists is a part of their distrust.

Read the blog post from David R. Johnson and Elain Howard Eckllund, authors of Varieties of Atheism in Science.

2. Corona and the crown: monarchy, religion, and disease from Victoria to ElizabethQueen Elizabeth II and the royal family have featured prominently in the British state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The expectation that the monarch should articulate a spiritual response to the threat of disease has deep roots. It took its modern form with Queen Victoria, whose reign decisively transformed the relationship between religion, the sovereign, sickness, and health.

Read the blog post from Michael Ledger-Lomas, author of Queen Victoria: This Thorny Crown.

3. Theodore Roosevelt’s religious toleranceTheodore Roosevelt is everywhere. Most famously, his stone face stares out from South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore. One of the most important but least recognized aspects of Roosevelt’s life are his ecumenical convictions and his promotion of marginalized religious groups. Through Roosevelt’s influence, Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Unitarians moved a little closer toward the American religious mainstream.

Read the blog post from Benjamin J. Wetzel, author of Theodore Roosevelt: Preaching from the Bully Pulpit.

4. The power of pigs: tension and taboo in Haifa, IsraelIt might be an exaggeration to say a boar broke the internet. But when someone posted an image of wild boar sleeping on a mattress and surrounded by garbage from a recently-raided dumpster in Haifa, Israel in March, Twitter briefly erupted. In a recent article in The New York Times, Patrick Kingsley documented the uneasy relationship, not only between people and pigs, but also between the people who want the animals eliminated and those who welcome them. But Kingsley curiously omits an important detail: the drama over the fate of Haifa’s boar plays out against a backdrop of taboo and religious law.

Read the blog post from Max D. Price, author of Evolution of a Taboo: Pigs and People in the Ancient Near East.

5. A pre-9/11 action movie with a Muslim hero shows what could have beenIn the fall of 1999, another action movie came and went, garnering disappointed reviews and a pittance in ticket sales. The 13th Warrior isn’t a great movie, nor is it even very good. But while the movie isn’t great, there’s no denying how cool it is, which is why viewers continue to revisit it. The Vikings are intimidating, the bad guys are scary, the hero rises to the occasion, and there are some intense action sequences, including a death-defying underwater escape from a cave. At its heart, it’s a story of people from different backgrounds learning to respect and value one other.

What has added to the film’s appeal over the years is its choice to center a devout Muslim in a macho American action movie.

6. Margaret Mead by the numbersThe life of anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) spanned decades, continents, and academic conversations. Fellow anthropologist Clifford Geertz compared the task of summarizing her to “trying to inscribe the Bible—or perhaps the Odyssey—on the head of a pin.

Discover Margaret Mead’s life by the numbers in this list post from Elesha J. Coffman, author of Margaret Mead: A Twentieth-Century Faith.

7. Putting transphobia in a different biblical contextAs right-wing and reactionary forces across the UK and USA increasingly incite panic about trans people and gender and sexual variation, so their arguments are relying on false assumptions about sexuality, especially in regards to history and religion.

In this new blog post, Joseph A. Marchal explains that these assumptions can be challenged simply by understanding that gender has never been fixed, both today and in the context of the ancient biblical texts that are frequently referred to by those who object to trans and queer people on supposed religious grounds.

8. The continuing appeal of religious politics in Northern IrelandOne of the most curious features of sudden-onset secularisation on the island of Ireland has been the revitalisation of religious politics. This is most obvious in Northern Ireland, where this past year, the chaotic introduction of the Brexit protocol, loyalist riots, and a controversy about banning so-called “gay conversion therapy” have been followed by dramatic declines in electoral support for and leadership changes within the largest unionist party that can only be described as chaotic.

Read the blog post from Crawford Gibben, author of The Rise and Fall of Christian Ireland.

9. Rehabilitating the sacred side of Arthur Sullivan, Britain’s most performed composerNovember 2018 saw the release of the first ever professional recording of Arthur Sullivan’s oratorio, The Light of The World, based on Biblical texts and focused on the life and teaching of Jesus. The critical reaction to this work, which had been largely ignored and rarely performed for over 140 years, was extraordinary.

Learn more about Arthur Sullivan’s religious music in this blog post from Ian Bradley, author of Arthur Sullivan: A Life of Divine Emollient.

10. Can skepticism and curiosity get along? Benjamin Franklin shows they can coexistNo matter the contemporary crisis trending on Twitter, from climate change to the US Senate filibuster, people who follow the news have little trouble finding a congenial source of reporting. The writers who worry about polarization, folks like Ezra Klein and Michael Lind, commonly observe the high levels of tribalism that attends journalism and consumption of it. The feat of being skeptical of the other side’s position while turning the same doubts on your own team is apparently in short supply. The consequences of skepticism about disagreeable points of view for the virtues of intellectual curiosity are not good.

Find out what Benjamin Franklin’s relentless curiosity can teach us in this blog post from D. G. Hart, author of Benjamin Franklin: Cultural Protestant.

December 28, 2021

The top 10 politics blog posts of 2021

How can we help Afghan refugees? What are the challenges facing American democracy? Is Weimar Germany a warning from history? These are just a few of the questions our authors have tackled on the OUPblog this past year. Discover their takes on the big political issues of 2021 with our list of the top 10 politics blog posts of the year.

1. Why has Gaza frequently become a battlefield between Hamas and Israel?During the past decade, the eyes of the world have often been directed toward Gaza. This tiny coastal enclave has received a huge amount of diplomatic attention and international media coverage. The plight of its nearly two million inhabitants has stirred an outpouring of humanitarian concern, generating worldwide protests against the Israeli blockade of Gaza.

In this excerpt from The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: What Everyone Needs to Know®, author Dov Waxman provides an overview of the conflict’s history and development.

2. Well-known secret graveyards: (re)discovering the horrors of assimilation for Indigenous peoplesThe Kamloops Indian Residential School was part of a systematic Indigenous youth educational effort in Canada, with comparable projects in the United States, the purpose and intent of which is hotly debated today.

In this blog post, Michael Lerma, author of Guided by the Mountains, gives his reaction to the recent discovery of mass graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, a former boarding school for Indigenous youth.

3. The democrat’s dilemma: how can we mitigate the conflicting responsibilities of citizenship?Government in any form exercises power over those it governs. In a democracy, this power is shared among equals who disagree over how power should be used. When democracy enacts policy, some citizens are forced to comply. How can one be subjected to political power without thereby being subordinated by it?

Learn about the democrat’s dilemma in this blog post from Robert B. Talisse, author of Sustaining Democracy: What We Owe to the Other Side.

4. The coming refugee crisis: how COVID-19 exacerbates forced displacementRefugees have fallen down the political agenda since the “European refugee crisis” in 2015-16. COVID-19 has temporarily stifled refugee movements and taken the issue off the political and media radar. However, the impact of the pandemic is gradually exacerbating the drivers of mass displacement.

Alexander Betts, author of The Wealth of Refugees: How Displaced People Can Build Economies, considers the impacts of COVID-19 on the refugee crisis and forced displacement in this blog post.

5. Nine challenges that American democracy faces [reading list]Explore the challenges facing democracy in the United States and in emerging democracies around the world with our newest books—including leading works in the field—in our reading list.

6. Why increasing deglobalization is putting vulnerable populations at riskThe record of globalization is decidedly mixed. Whereas proponents tend to associate globalization with beneficial developments such as the expansion of democracy and improved access to goods and services, critics highlight the human costs: rising inequality and political and economic exploitation.

In this blog post, Jarrod Hayes and Katja Weber argue that deglobalization is undermining the international community’s ability to limit human rights abuses, using Myanmar as a case study.

7. Fiddling while Rome burns: climate change and international relationsIn this blog post, Jørgen Møller describes working and writing from home during a pandemic, discusses climate change as a third major issue area of global politics, alongside security and economics, and considers whether chaos or order is brewing in the world.

8. How can we help Afghan refugees?“The outpouring of support for Afghan refugees since the fall of the Taliban a few weeks ago is laudable. As the author of two books on our obligations to refugees, many people have been asking me about how we should respond to this crisis and what we can hope for Afghan refugees. There’s both a lot we in the United States can do and a lot we should be worried about.”

Read the blog post from Serena Parekh, author of No Refuge: Ethics and the Global Refugee Crisis, on what can be done to help resettle Afghan refugees in the aftermath of the War in Afghanistan.

9. The ghosts of Weimar: is Weimar Germany a warning from history?The ghosts of Weimar are back. Woken up by the rise of populist right-wing parties across Europe and beyond, they warn of danger for democracy. The historical reference point evoked by these warnings is the collapse of the Weimar Republic followed by the Nazi dictatorship. The connection between now and then seems indisputably obvious: democracy died in 1933, and it is under attack again today. But does the comparison make sense? This blog post will argue: no!

Read the blog post from Nadine Rossol and Benjamin Ziemann, co-editors of The Oxford Handbook of the Weimar Republic.

10. Sustainability in action: dismantling systems to combat climate changeContrary to the opinion that sustainability is an almost meaningless concept, analysts have developed theoretical tools for understanding why systemically supported processes resist disruption, bounce back after perturbation, and exhibit structural evolution. Considering the COP26 conference, it is time for everyone to examine the self-reinforcing systems that have made climate change so difficult to stop.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers