Oxford University Press's Blog, page 86

January 28, 2022

Having data privacy rights is of no use if you cannot claim them

The focus of legal discussions on data protection and privacy is normally placed on the extent of the rights conferred by the law on individuals. But as litigation lawyers are painfully aware, to have a claim valid in law is not the same as succeeding in court, as being “right” is expensive business and litigation financing is a key part of being successful.

The civil justice system in England and Wales, which governs claims for redress between private individuals (and business), is on its knees and has been so for many years. After successive cuts to the civil justice budget, court closure, and the removal of financial help to litigants (in the form of legal aid in civil cases), for most but the richest claimants, litigation in the civil courts is too costly and, hence, illusory. It is therefore about time that the UK government should consider enacting legislation to provide a clear and comprehensive framework for collective redress. Collective redress allows the pooling of resources between civil claimants, enabling them to share the costs, and enables the development of sophisticated litigation funding strategies, which address the access to justice issue.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the technology sector. While the internet, user-generated content, user- profiling and tracking, search engines, and ambient computing are all greasing the exploitation of big data (including personal data) for wealth creation, the flip side of all this data science innovation are endless possibilities for privacy infringements, which threaten human autonomy. Users in the European Union (EU) have obtained a gamut of “data subject” rights in 2018, under the EU’s flagship data protection law, with the sexy name “General Data Protection Regulation” or GDPR. But the GDPR has shied away from an effective collective redress regime. More to that later. Arguably this is because of the bad reputation of United States-style class action regimes.

At the end of 2021, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (UK) had to decide whether to allow a representative action brought by Richard Lloyd, a consumer rights champion, on behalf of the more than 4 million users who had been spied upon by Google’s ad cookies. In a long-awaited ruling, the highest court in the UK held that the action could not proceed, even though the Court found that the claimant Richard Lloyd would probably have been successful if he had brought the action on his own behalf. The reason for this is that a person trying to bring a representative action faces a conundrum. It is for this reason that representative actions are infrequently used, even though they are long-established under the English common law.

The background to this case, is the so-called Safari workaround, which allowed Google in 2011-2012 to place cookies on Apple devices, even though they had been designed to prevent the placement of such cookies. This placement was without the knowledge or consent of users, most likely in breach of EU data protection legislation.

Given the overwhelming and dominant power of a few dozens of Big Tech companies and the exponential growth of the exploitation of our private information as big data, it seems right to ask whether a collective redress system is not needed in Europe (meaning both the EU and the UK) to rebalance the struggle between minimizing the collateral damage to our privacy with technological innovation. This is important both from the perspective of individual consumers and citizens as well as the importance of civil liberties for society as a whole.

Therefore what is the conundrum with the existing tool of representative actions in the toolbox of common law civil justice? It is this: the claimant essentially must show that all the claimants represented “have the same interest,” but a claim for compensation, for breach of data protection law, must be individually assessed. In other words, how much money each claimant gets in compensation depends on many factors, such as their internet use, the nature of the information collected (for example, has a user visited pornographic or gambling websites or accessed medical information?), and the amount of distress caused. This individualised assessment means that the claimants represented in the action do not have “the same interest.” This ruling, which means a clear victory for Google (at least for now), also means that a claim for damages in these cases cannot be brought through a representative action.

This is all the more frustrating as in a previous case on phone hacking by newspapers (Gulati v MGN [2017] QB 149), which went as far as the English Court of Appeal, the judges confirmed that if the claimant frames his claim under the tort of misuse of private information, the claimant need not prove what damage he or she has suffered—the privacy infringement itself amounts to loss of control over private information and this loss is the relevant damage—hence no need to assess the loss individually.

But of course, before claimants can succeed in establishing that their privacy has been infringed in a way which entitles them to compensation, they must show that they had “reasonable expectations of privacy.” This very much depends on the circumstances; for example, there are fewer expectations of privacy if you are photographed in a public place compared to a private place and more expectations of privacy if you are doing something intimate (such as a sexual act) compared to doing something mundane (such as walking down a street). Therefore this test also requires an individualised assessment of circumstances, which in many situations might bar a representative action.

One ray of hope might be that the Supreme Court ruling of Google v Lloyd relied on the interpretation of the “old” data protection legislation (the UK Data Protection Act 1998, the national law stemming from the EU 1995 Data Protection Directive), which was superseded by the EU GDPR in 2018. Even though the UK has left the EU (at least to date), it has retained the GDPR in its national law and passed the Data Protection Act 2018 to implement EU standards in the UK. This now makes it clear that compensation is available for non-material damage (such as injury to feelings and distress). But whether this phrase, “non-material damage,” also includes loss of control over private information as a damage for which compensation may be obtained is not so clear. However, the inclusion of different types of non-material damage in the statutory scheme may mean that a future claimant may be successful in a representative action based on the Data Protection Act 2018. Instead of relying on an individualised assessment of distress, a future court may recognize a different type of damage which equally applies to all claimants in a representative action.

In the David versus Goliath fight between individual claimants and Big Tech, it is important that David is given a chance. Big Tech companies operate across international borders and have endless resources—this makes it almost impossible for claimants to succeed in mass privacy infringement cases. This imbalance should be urgently addressed through collective action schemes for data protection and privacy disputes that allow claimants to share the costs of litigation. The government will have to review the effectiveness of collective redress in data protection cases in 2023—arguably, it is time to act!

Featured image by FLY:D.

January 27, 2022

The road from Berlin in 1989 to America today

In November 1989, the world watched with disbelief as crowds tore down the Berlin Wall. In America, we assumed that we were witnessing the end of communism and speculated about the rise of democracy in Eastern Europe and maybe even in the Soviet Union. These ideas guided our thinking for the next several years, but soon other unanticipated developments began to appear, many of which stood in striking contrast to the heady expectations of November 1989.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was a watershed event that made what had previously been unthinkable thinkable, and it set off a cascade of developments such as the decision by several former Soviet republics’ decision to break with Moscow and become independent sovereign states. Initial attempts to make sense of what was going on took place against a background of such incredulity that some analysts suggested it was all a feint by the Kremlin to get the West to let its guard down. Some even denied that any real upheaval had occurred at all. For many people in Eastern Europe and the USSR, though, 1989 was the moment they began to imagine a future that differed radically from anything they previously deemed possible.

Much of this is now forgotten in the United States due to our short attention span and collective memory, but elsewhere it is remembered very well. I have in mind China in particular. This may come as a surprise to Americans, but in Beijing decisions made in 1989 by General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Mikhail Gorbachev continue to be studied avidly in an effort to understand how states and entire societies can collapse if they do not have a strong, even brutal, leader at the helm. In both China and Russia, national memory of social upheaval extends back centuries, and in both places, the pantheon of heroic leaders includes figures who brutally crushed any hint of rebellion. For China, then, the story of Gorbachev’s failure in 1989 serves as an object lesson about what comes with having inept and weak leaders.

In 2021, this has given rise to a strange and shocking irony for America. Today, public figures in Russia and China see clear parallels between the demise of the Soviet Union a few decades ago and the situation in the US today. This is sometimes formulated as advice from a concerned friend. For example, the Global Times, a nationalistic paper in China published a column titled the “World recoils in horror at alarm sounded by Capitol riots” in which it warned America of an impending danger. To compound this irony, the column drew on words from Mikhail Gorbachev, who believed the US could follow the path of the USSR to disintegration and warned that “the events called into question the US’ [sic] continued existence as a nation.”

Such assessments in Chinese media of course amount to praise for the supposed far-sighted vision of the Chinese Communist Party and its infallibility in dealing with dissent at home. But these warnings are harder to laugh off in an America characterized by the extreme polarization and an attempted overthrow of a presidential election in January 2020. And these warnings are coming not just from China and Russia. Responsible and thoughtful Western figures have come to similar conclusions. In the US, for example, Fiona Hill, a distinguished Russia watcher at the Brookings Institution, outlines ominous parallels in her powerful new volume There Is No Place for You Here, where she warns that “Russia Is America’s Ghost of Christmas Future.”

Such a vision of where we would be in 2021 was completely unimaginable in 1989. In retrospect, however, some of the advice we were so busy giving others at the time on how to run a democracy might have been better applied at home. Had we seen this strange course of events unfolding ahead of us, would we have addressed impending problems of our own? Could we have? Or will the events that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago remain an episode in human history that no one seems to understand, let alone control? Another 30 years will tell.

Featured image by Alessandro Bellone on Unsplash

January 26, 2022

Seeing is believing (?)

Last week, I wrote about the origin of the verb hear. It is only natural that today I’ll try to say something about the verb see. Once again, we’ll have to admit that the more basic a word is, the less we know about its remote history.

Like hear, the verb see has cognates in all the Germanic languages. They all sound alike and mean the same, but, as usual, the fourth-century Gothic form (which is saihwan: pronounce ai as in Engl. set or sat, and h as in hat) is of special importance, because it is the oldest one on record. In Gothic, we also find the word sai (ai again as in saihwan) “look, behold!” Is this word a Gothic neologism, the first syllable of saihwan, turned into an imperative? It would have been tempting to let sai have its own origin and produce saihwan from it, but what then is –hwan? Apparently, this is a dead-end etymology. Sai looks like a demonstrative pronoun (this). In the New Testament, it corresponds to Latin ecce.

Seeing is believing.

Seeing is believing.(Photo by Nathan Bingle on Unsplash.)

Not without hesitation, many dictionaries still cite Latin sequī “I follow” (cf. Engl. sequel, consequent, and so forth) as related to saihwan. The phonetic correspondence could not be better, but the underlying sense poses a problem. Is it “to follow with one’s eyes”? According to an old suggestion, the verb of seeing was originally coined by hunters and meant “to sense; to follow the trail.” Some support for this hypothesis exists in Lithuanian usage, and it has recently found support in an authoritative book on Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. The argument depends on a familiar conundrum. You may remember that a week ago, we were left wondering whether ear and hear are related. It would seem that the words eye and see have nothing in common, but, given some ingenuity, we may come up with an almost identical root. Indo-European roots often appear with or without initial s (this is the familiar s-mobile). Latin oculus and Gothic augo “eye” can perhaps be traced to the root (s)okw “eye,” in turn akin to sekw “to see.” I will now quote from the book referred to above:

“If we project the cooccurrence of both meanings in a single word onto the Proto-Indo-European level… we must posit a common word with the meanings ‘eye’; ‘view’; ‘look, see’ and also ‘follow, pursue’. This combination of meanings becomes understandable through the intermediary meaning ‘follow with one’s eyes, not let out of sight, use with the quarry as object.”

Granted: it is tempting to reconstruct the mentality of the early hunter speaking Proto-Indo-European, but such somersaults leave one a bit dizzy.

Another less audacious approach connects see, that is, Germanic sehwan, with verbs like Latin secare “to cut” (cf. Engl. sect, section, dissect, and the like). Indeed, seeing is the result of looking and observing: we dissect, cut the picture into fragments, and see what we are looking at. Not long ago, this etymology was defended by Viktor Levitsky. Additionally, he resurrected the old suggestion that see and say are related: “cut—make a furrow—pursue—watch, see—consider—speak, say.” Latin insequor means “to follow, pursue; attack” and “berate, reproach.” At the moment, we needn’t bother about say.

Looking and observing… Most Indo-European languages have different words for “look” and “see,” and, if the same root is used, then the verb of looking has a prefix. Latin distinguished between vidēre and specere ~ spectare (as in Engl. specter, spectacle, inspect, and the rest). Hear and listen are often related in the languages of the world, but surprisingly, see and look are usually (or even as a rule) derived from different roots. Though Engl. look has cognates in Germanic and perhaps Celtic, its etymology remains unknown. Elsewhere, the verb meaning “look” is related to the verb for “show” or for “a source of light.”

An anthropos as a seeing individual.

An anthropos as a seeing individual.(“U.S.S. sailor looking through telescope on Mayflower,” Library of Congress via Picryl.)

In an attempt to decipher the origin of the verb see, a list of cognates takes us almost nowhere. Similar-sounding verbs have been recorded in Albanian and Celtic. Quite probably, they are related to Germanic sehwan (Gothic saihwan), but since they also mean “see” or “indicate,” that is, the same or approximately the same as see, they are of limited use in our search. More interesting are Hittite sakuwa “eyes” and Lithuanian sèkti “to follow the track of.” For curiosity’s sake, I’ll cite an example of an especially ingenious attempt to find a cognate of our verb. One of the hardest words for etymologists is Greek ‘anthrōpos “a human being.” If this noun is, from a historical point of view, ‘anthr–ōpos and means “a seeing individual,” then perhaps –ōpos from sokwos joins the club. This guess has not inspired anyone, even though some good parallels turned up in Greek. I may add that words have an uncanny ability to hide their past. For instance, German seltsam “rare” goes back to the adjective selt-siene “seldom to be seen,” but it hid its origin behind the suffix –sam. If we did not know the oldest form, we would never have guessed the history of this adjective.

An etymologist is a sharp-eyed hunter and searches for tracks everywhere. The Germanic for “eye” must have sounded somewhat like German Auge and Gothic augo, which is almost a twin of Germanic auso– “ear.” Eyes and ears are our main organs of perception. Is it not possible that they were coined with the view of emphasizing the similarity of their function? I am saying this to explain why an informed entry on eye tends to contain only ingenious guesses and why a satisfactory solution can hardly be expected. Finally, as is well-known, people were afraid of speaking about their body for fear of harming it and intentionally disguised the word’s true form. You will mention an eye and go blind (speak of the devil!). This, as most will remember, is called tabu. Perhaps the word for “eye” was at one time changed beyond recognition, and all links to its origin are lost.

Once again, we have been exposed to a medley of conflicting hypotheses. Yet we are not completely in the dark with the verb see. Rather probably, the original sense of the verb was close to “perceive; get to know.” Latin vidēre “to see” is related to Engl. wit (German wissen) “to know” (as in to wit, witless, and witty). The connection is impeccable, and it appears that seeing referred to a continuous mental effort and its results. Characteristically, in several old languages, the verb in question, as opposed to the verb of looking, had no past or perfect (the action referred to a process confronting the viewer at any given moment and did not need those forms!). The root of Russian smotret’ “to see” recurs in several Slavic words meaning “seek” and “careful.” Especially typical is Bulgarian smotra “I think, I believe.” Compare Engl. I see “I understand.”

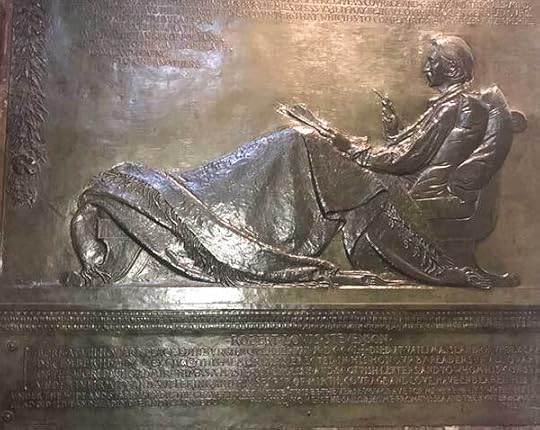

The hunter is down from the hill.

The hunter is down from the hill.(“Robert Louis Stevenson sculpture in St. Giles’ cathedral” via Wikimedia Commons.)

I have some doubts about our verb going back to the ancient hunter’s mentality. Ties with Latin oculus are also hard to establish, but Hittite sakuwa “eyes” (see it above) suggests that the words for “eye” and “see” may sometimes be related. We have no way of deciding whether the similarity between augo– “eye” and auso- “ear” is accidental. The idea that seeing is tantamount to dissecting and discerning holds out some promise.

It would be rash to assert that, with this essay in the bag, “the hunter is down from the hill,” but perhaps some conjectures presented above should be treated with tolerance and rescued for further investigation.

Featured image by David Travis on Unsplash

January 25, 2022

Importance and uncertainty: referendums in the United Kingdom

Referendums—popular votes held on specific subjects—are an important part of United Kingdom (UK) politics. But they are also surrounded by doubts and disagreement. In mid-September 2021, the Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon called for the UK government to cooperate on the holding of a Scottish independence referendum by the end of 2023. A referendum took place on the same subject in 2014. On this earlier occasion, the then-UK Prime Minister David Cameron had agreed to the vote taking place and that the UK government would abide by the result if Scotland voted to leave the UK. However, the referendum produced an outcome in favour of remaining part of the UK, by roughly 55% to 45%.

Supporters of a further referendum on independence claim that the issue has been revived by UK exit from the European Union (EU) in January 2020. The decision to leave the EU—itself brought about by a referendum, held in 2016—was opposed by a majority of voters in Scotland (62% to 38%), while the UK as a whole backed leaving by roughly 52% to 48%. Advocates of Scottish independence are able to argue that the terms of presence within the UK have therefore changed substantially since the 2014 referendum, with Scotland being forced out of the EU against its will. In supporting a further vote on independence, they can also point out that pro-independence parties that support independence and a referendum have a majority in the Scottish Parliament. Sturgeon’s party, the Scottish National Party (SNP), and the Scottish Green Party (who have shared ground on this matter) have a combined total of 71 seats out of 129 (respectively 64 and 7) in the Parliament.

But though there may be majority support for a referendum within the Scottish Parliament, it is not entirely clear that this institution has the legal right to instigate the vote on its own initiative without consent at UK level. It is for this reason that Sturgeon has asked for cooperation from the UK government. The Conservative UK government is opposed to Scottish independence, and leading members of it have argued that a further referendum on this subject, relatively soon after the first such vote in 2014, is not justified. If no agreement can be reached, an option for the Scottish Government could be to seek to proceed with referendum regardless of whether it has such backing, though this course of action would be legally controversial and could well lead to a court case.

This stand-off between the Scottish and UK governments illustrates two points. The first involves the significance of referendums to UK politics. They are used for making some of the most important decisions: whether or not a particular territory should remain part of or leave the UK; whether the UK should continue to participate in European integration or withdraw from it; whether to establish devolved systems in parts of the UK; and what voting system should be used in UK general elections. Even when they are not held, the prospect that they might be can be influential on political outcomes.

Those who disliked the use of referendums once used to hold that, as devices of direct democracy, they were incompatible with the UK system of representative democracy, and that they were alien to it. But the UK has been discussing the idea of using referendums since the late nineteenth century, when interest began to develop in their use elsewhere in the world, in particular in Switzerland. The practical holding of referendums at local level, on such subjects as the creation of libraries and whether public houses should open on Sundays, has a similarly long history. After recurring discussion, referendums began to take place above local level in 1973, with a vote in Northern Ireland on whether the territory should continue to be part of the UK or join with the Republic of Ireland. A further 12 votes on major issues have taken place since, the most recent of which occurred in 2016 on EU membership. The idea of holding more, notably on the future presence of both Northern Ireland and—as we have seen—Scotland within the UK, remains on the political agenda.

In 2000, the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act provided a legal framework within which such votes should take place, in recognition of their established position within UK politics. But it left many doubts—which is the second observation to be made about referendums. However important the referendum has become, uncertainties surround its precise nature. General agreement is lacking about matters such as the precise issues over which it is appropriate to hold referendums; how they can be triggered; what is the status of their results; and how soon a further referendum can be held on the same subject. A swift resolution of such matters seems unlikely. Consequently, we can continue to expect referendums not only to be used in relation to divisive issues, but to be the subject of controversy themselves.

Featured image: Timon Studler on Unsplash

January 24, 2022

Staging philosophy: the relationship between philosophy and drama

Where does philosophy belong? In lecture halls, libraries, and campus offices? In town squares? In public life? One answer to this question, exceedingly popular from the Enlightenment onward, has been that philosophy belongs on stage—not in the sense that this is the only place we should find it, but that the relationship between philosophy and drama is particularly productive and promising.

Diderot, Voltaire, and Lessing refused to draw an absolute distinction between philosophy and drama—and excelled in both. Drama featured centrally in the works of nineteenth-century luminaries such as Hegel and Nietzsche. It should not surprise that modern dramaturges and directors drew on philosophy to formulate their views about the arts of drama and theater. It was in this intellectual climate that the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen positioned himself in the 1850s and 1860s.

In Copenhagen, where Ibsen spent time during his apprentice years, the theater was dominated by the powerful Johan Ludvig Heiberg. Heiberg was a student of Hegel and the author of a number of Hegelian writings. Hegelianism prospered among the Scandinavian expats in Italy, where Ibsen spent a formative period. Hermann Hettner’s Hegelian treatise is described by Ibsen as “a manifesto and program for reform in the modern theater.” Later on, Nietzsche’s reflection on tragedy, history, and morality gained traction. We see Ibsen’s mentor Georg Brandes transition from a romantic to a Hegelian and, finally, a Nietzschean position. Lou Salomé, the author of the path-breaking Eroticism as well as an early monograph on Nietzsche, wrote an early study of Ibsen’s heroines.

When trying out ideas for a commission for the University of Oslo, the painter Edvard Munch sketched Ibsen with Nietzsche and Socrates. In Ibsen’s work, we encounter Sophists and Platonists. In Peer Gynt, the eccentric protagonist encounters a Hegelian director of a madhouse. Peer himself grandly converses about world history and logic. Works such as Hedda Gabler and An Enemy of the People put into play distinctively Nietzschean characters and address topics such as the relationship between life and learning, and the need for critical and existential approaches to history. The point is not that Ibsen, as a dramatist, passively drew on philosophical ideas, but that he allowed his characters to live out a set of worldviews, to test, as it were, their viability in the laboratory of individualized life. Ibsen actively transforms and challenges the philosophy of the nineteenth century. His drama does not make use of philosophy. It is philosophical. It is as such that it caught the attention of Freud, Adorno, Cavell, and others.

Ibsen wrote in a period when philosophy was in the process of becoming increasingly academic. Philosophy understood itself as scientific and, as such, sought to guard its boundaries towards the arts. This, however, did not prevent philosophers from thinking about drama: its status as an artform, its cultural function, the relationship between drama as written and as performed in the theater.

For Lessing and Herder, drama was the artform through which a historical culture would articulate itself. A dramaturg at the prestigious Hamburg theater, built to celebrate the city’s independence from the Danes, Lessing set the agenda for modern dramatic arts. Gone were the ideals of classicism. Modern drama cannot imitate the great tragedies and comedies of the ancients, but must put on stage the conflicts, contradictions, and experiences of modern life. With Herder, Shakespeare’s drama, featuring people of all classes, dialects, and worldviews, is put forth as a new paradigm. Here drama is freed from the distinction between high and low. It is, Herder argues, an art of the people. August Wilhelm Schlegel further developed this kind of thought. His lectures on drama launched a frontal attack on the formalist view of the purity of art and the autonomy of aesthetic judging. Following this lead, Hegel argued that drama explores the nature of human action—both in its ancient and in its modern forms. It is, at the end of the day, the highest stage of art. And even though Nietzsche was critical of Hegelian idealism, he continues its fascination with tragedy. For Nietzsche tragedy originally gave rise to the most profound metaphysical experience.

Nineteenth-century philosophy of drama is no doubt fascinating. It should not surprise that playwrights such as Ibsen found such discussions fertile ground for dramatic content and reflections on the nature and politics of drama.

Yet, at some point, the budding dramatist would have been disappointed. For Hegel philosophical thinking was ultimately assigned priority over artistic form. While historically important, art represented an incomplete stage in spirit’s cultural-educational development. Nietzsche, on his side, prioritized the mythological, rhythmic, and musical dimension of tragedy over characters and actors.

For modern dramatists, by contrast, no such limitations apply. Instead, it is philosophy, with its abstractions and theorizing, that falls short. As such, it is fitting that Ibsen would present the (Hegelian) philosopher as the director of a madhouse or the (Nietzschean) philosopher-historian as being drawn to the lethal mix of alcohol, unhappy love, and loaded pistols (Hedda Gabler).

Ibsen is not committed to a particular position or point of view. He hones in on the existential dimensions and consequences of positions and worldviews that would otherwise remain theoretical and academic. He engages philosophical ideas from the point of view of lived life. He takes these ideas as far as life can hold them and then puts them into focus as they burst and fall apart.

Academic philosophy is sometimes hostile towards the idea that philosophy can take artistic or non-academic forms. But to the extent that philosophy is committed to the examined life, we will, as philosophers, be poorer if we leave out the quests for truth and understanding that drama, in Ibsen’s vein, embodies.

January 22, 2022

Majority rule is not democracy

A group of partisans burst into the Council Chamber and summarily killed the leaders of the opposing party, which represented the majority. The year was 427 BCE and the place was Corcyra, modern Corfu. The parties were divided over whether the Demos—the people–or the Oligoi—the wealthy few—should rule, as well as over specific issues of justice and foreign relations. Our source for this, Thucydides, wrote that the cause of the civil war was “the desire to rule out of avarice and ambition.” Both sides plunged into atrocities as civil war spread out and continued to flame until the leaders of the Oligoi had all been slaughtered. Civil war is a colossal failure of democracy.

In Corcyra, this failure began long before the killings, with an abuse of justice. What is democracy? Pundits have been writing recently that democracy is majority rule, but that is wrong, dangerously wrong. Corcyra came apart because the majority was using legal machinery to abuse its wealthy opponents, the Oligoi. And those opponents saw no way apart from violence to defend their interests. Majority rule was ultimately to blame for this civil war.

“Pundits have been writing recently that democracy is majority rule, but that is wrong, dangerously wrong.”

Democracy is rule by the people and for the people. The majority is not the people. We cannot say this too often: rule by the majority is not rule by the people. For the people to rule, they need to meet a number of conditions. Of these, the rule of law stands out, because it is the rule of law that stands between democracy and the tyranny of the majority. Minorities must be included in the people, and so the law must give them ways to defend their interests. Beyond law, the culture of a democracy must be inclusive.

The ancient Greeks found their way to create a form of democracy in Athens after a period of rule by tyrants. They were able to do this because they were developing a culture that was friendly to democracy. Central to this culture was their devotion to the rule of law—the idea that no one is above the law, and that no one should be able to use wealth or influence to skirt the law. I admit that the culture of Athens was flawed in many ways: It permitted slavery, and it kept women out of political life. Nevertheless, we have something to learn from the ancient Greeks about democracy. For most of the first century of democracy in Athens, civil war remained a threat, as the wealthy remained discontented. But after the final restoration of democracy in 403 BCE, the system was reformed and worked well until it was put down by the mighty army of Alexander the Great.

“The rule of law .. stands between democracy and the tyranny of the majority. … Beyond law, the culture of a democracy must be inclusive.”

What is essential for a culture to be friendly to democracy? I have already mentioned the rule of law. Also important is a concept of the people as a people. For the people to rule, and to do so in their interests as a people, they must think of themselves as a people. The Athenians had the advantage of a shared history, a shared religion, and shared civic rituals. We Americans have a shared history (up to a point) and a few shared rituals (such as watching football). But our racial divide has left us with different histories and, for many of us, a fractured sense of what it is to be American. Our greatest challenge is this: to develop a widely shared sense of what it is to be we the people.

We have other challenges. Systemic inequality is not compatible with democracy. We are beset by vast inequalities of wealth and opportunity, as well as by inequalities in basic needs such as housing and health care. Our system of education fails to prepare many of our young people for meaningful lives. And I believe our education fails altogether to give Americans an understanding of the various forms that democracy can take—most of which are superior to the form available under our deeply flawed constitution. No form of government is perfectly democratic in practice. Democracy is an ideal, a dream we should try to make real. In my book on democracy, I concluded by asking whether we Americans were ready for democracy. I concluded, sadly, that we were not. That was in 2004. Where are we now? Are we any more ready for democracy than we were then? Or is the danger of failure greater now?

Featured image by Harold Mendoza on Unsplash

January 20, 2022

Do Look Up! Could a comet really kill us all?

It’s no mystery why the movie industry likes dramatic stories. Certainly, the occasional contemplative movie may achieve critical praise and general acclamation, but a well-written story about death and destruction often carries the day. When it comes to catastrophic events for humans, a big nasty asteroid or comet colliding with Earth tops the chart, and several movies have exploited this scenario. The recent Netflix movie Don’t Look Up did that again, but as a satire and a warning. It is widely considered an allegory for climate change, but let’s consider the astronomical scenario as presented. In the movie, a couple of astronomers serendipitously discover a comet on course to collide with the Earth in about six months, give or take. Is such a scenario scientifically sound?

First, we need to know the orbit of a celestial body, whether asteroid or comet, very precisely in order to establish that it’s highly likely to be on a collision course (99.78% probability, the astronomers claim). The Earth is less than a grain of sand, a mere 12,742 km in diameter, compared to the vast expanse of the Solar System, extending tens of billions of kilometres from the Sun. In the movie, the comet is first seen to pass by Jupiter (say, 1 billion km away). That means the angular precision on the position of the comet needs to be about 10-5 arcseconds – equivalent to seeing a fly from 500 m away. Such precision can’t be achieved with a single observation, even by the most powerful telescopes. That is why astronomers usually need to observe asteroids and comets multiple times over a long interval, typically years. So, the premises of the movie are a bit flimsy.

The other aspect is the size of the object. How likely is it for a 5-10 km asteroid or comet to be hurtling towards Earth? As I discuss in my book Colliding Worlds, collisions have occurred throughout the history of the Solar System. In its heady early days, the Earth and other planets were formed and shaped by massive collisions. Although things are quieter today, we know that asteroids—the rocky leftovers of planet formation found within Jupiter’s orbit—can occasionally skim the Earth. We also know from years of observation that there are very few asteroids close to Earth larger than five km (just 12 to be precise), and none of them has a serious probability of collision with the Earth for hundreds of thousands of years. By then, we would probably have gone extinct through other causes, or left the planet, so we don’t need to worry about these large asteroids. There are plenty of smaller asteroids, but they pose a more limited threat.

Comets, however, as correctly presented in the movie, are a different beast. They are much harder to observe when far away, beyond Jupiter’s orbit. And many of them are parked so far from Earth, in a wide spherical shell called the Oort Cloud more than 150 billion kilometers away, that they are simply not visible to us until they get dislodged and hurtle towards the inner Solar System. The likelihood of such objects colliding with the Earth are very low, but not zero; one in every 500 million Oort Cloud comets is a potential destroyer of life on Earth.

How can we mitigate this cosmic threat from the cold outer reaches of the Solar System? Or the more likely scenario of collision by a smaller asteroid that may not destroy life on Earth but would still be able to cause significant local damage?

Do look up! There is really no other way. Knowledge of how many hazardous objects are out there is the first course of action. The movie highlights and satirizes the tension between scientists trying to present the evidence and politicians more concerned with election prospects and lucrative interests (mining the comet, really?!), and a media too busy feeding celebrity trivia to a public suspicious about science. We know how it’s all going to end. The personal, obtuse interests of the few in power, swayed by the hare-brained schemes of technocrats, will prevail, with little hope for the human race. These are important messages for the failure to tackle climate change. But focusing on the celestial collision scenario, even if all of humanity could come together, would it even be possible to knock an astronomical foe from its course?

There is no way a 5-10 km comet could be deflected. Nor even a much smaller body. We simply do not know how to do this. Several ideas have been proposed, ranging from nuclear bombs to focused solar energy, but without an actual experiment we really don’t know what would work. And consider that building a space mission from scratch to intercept an object would likely require a few years. So, at the very least, we would need to identify a deflection method that works, and then have a spacecraft stand by, just in case. Not to sound pessimistic, but that is where we stand today. Still, it’s not all doom and gloom, and international efforts are under consideration. In October 2022, NASA’s DART mission will send a spacecraft to collide with a small asteroid (not a risk to Earth) and measure the resulting change in its trajectory. If successful, this could be an avenue for future, more capable missions.

The movie ends with a motley crew of rich and powerful humans, including the US president and the creepy tech billionaire who wanted to mine the comet, escaping Earth in a spaceship until, after hibernating in space for 27,000 years, they land on an Earth-like planet where, ironically, dinosaur-like creatures roam free. If the dinosaurs on Earth hadn’t been wiped out 66 million years ago by a large asteroid, giving a chance to early mammals, we wouldn’t be here. So, let’s consider the positive. In Colliding Worlds, I stress that collisions can be constructive too. We owe our existence to a random impact 66 million years ago, and maybe it was the multitude of early impacts that seeded the Earth with the ingredients for life. But all the same, now we’re here, and just in case, do look up!

The challenges and opportunities of studying the digital cultures of South Asia

Like all aspects of the cultural landscape in South Asia, the digital sphere is increasingly a site of fractious contestations where immense hope and optimism on social change and progress coexist alongside despair and anger around a host of social and political issues. South Asia’s postcolonial legacy, the teeming plurality of its cultural sphere, the ideological battles that play out in its electoral politics and the sheer scale of its digital population render its distinctions from other digital spheres as more than a mere cliché. These are further intensified by its smartphone-led digital economy that boasts of the lowest data rates in the world.

For scholars of the digital, this emerging space provides a rich site for insights into many key questions that have driven scholarship about the web from the time of its inception. What should be the balance of power between the people, the state, and the digital corporations that increasingly predominate the web? To what extent, if any, must free speech, commerce, and cultural creation and expression be regulated on a medium whose architecture can facilitate subversion by design and thus pose an existential threat to the sovereignty of the nation state? How do the eternal battles between national security and individual liberty play out in a region with its own historically rooted understanding of concepts such as liberty, subjectivity, community, and culture?

Home to a quarter of the world’s population, South Asia’s eight countries represent a broad spectrum of legal and political regimes of media regulation and ideological positions on free speech, which translate into varied attitudes towards emerging media technologies and the Internet. Having overcome their initial suspicions (often rooted in their colonial experience) towards the novelty and power of the digital media, these states have shifted gradually towards digitization and digital governance structures while walking a tightrope—they have tried to balance the medium’s potential in unleashing a communications revolution while also trying to shape it towards achieving specific national goals and values. The resulting patchwork of regimes, regulations and digital ecosystems make the region a microcosm of possibilities and challenges that will play a significant role in shaping the future of the web.

Signs of an alternative digital space shaped by the distinct historical lineage and contemporary politics of South Asia are visible in how citizens in the region are grappling with and responding to the challenge both of digital media oligopolies and the state’s overbearance in regulating the web (ostensibly on their behalf). These attempts can reveal glimpses of an alternative digital sphere that looks different from the established pathways elsewhere—the corporate-led digital ecosystem in the US, a state-led pushback as in the EU, and a seamless alignment between the digital sphere and the ideological party-state as in China. Juxtaposed alongside these visions lies the more utopian possibility of an organic, citizen-centered web that is propelled by and created for its users. While South Asia is far from achieving that in a full-fledged way, modest signs of alternative visions do appear. Perhaps the clearest exemplar of this vision is the activist-led and citizen-organized movement against Facebook basics in India that (in 2016) exerted enough pressure on the state that it had to renege on its commitments and overtures to the social media behemoth and ban its “free” connectivity scheme (that violated net neutrality) from the country. However fleeting a moment, the innovative strategies used by the #savetheinternet movement showed the possibilities of civic action mobilized around a digital cause (and against a Silicon valley technology giant) that revealed what sovereignty emerging from grassroots activism could look like in the digital era.

From “AIB : Save The Internet 2 – Judgement Day” by All India Bakchod on YouTube.

From “AIB : Save The Internet 2 – Judgement Day” by All India Bakchod on YouTube.Alongside these moments of hope exist those of worry and despair that manifest in cultures of extreme speech, internet shutdowns, state led disinformation campaigns, and attempts to suppress dissenting voices marginalized along the vectors of religion, caste, and gender (among others). Newly introduced rules for regulating online content in both India and Pakistan show these states’ creeping attempts to curb and rein-in potentially threatening speech under the guise of national security or “cultural and moral” concerns. Hence, valorizing the empowering aspects of South Asian digital culture does not mean ignoring these equally dystopian tendencies that are often fueled by a majoritarian will to dominate and disempower the weak and the voiceless.

As we recognize these manifestations of power and control, we must do so alongside the resistances they generate (including against the new digital regulations) that adopt novel forms and idioms unique to the region. A now famous exemplar of these is the protests against the YouTube ban in Pakistan when activists walked the streets of Karachi dressed in a box with the YouTube logo asking common citizens for a hug to show solidarity for re-allowing the platform in the country.

From “Hugs for YouTube! #KholoBC” by Ziad Zafar on Vimeo.

From “Hugs for YouTube! #KholoBC” by Ziad Zafar on Vimeo.As digital media make further inroads into the unconnected parts of the region, they will enmesh with pre-existing cultures generating dialectical forces of creation and censorship, state control, and user resistance as well as the three-way tussle between global digital oligopolies, sovereign states, and local innovation and ingenuity. This churning will yield rich case studies allowing us to build further on this forum’s commentaries to expand the burgeoning scholarship and theoretical categories for the region.

January 19, 2022

Hearsay? It depends on what you hear

Even if not without some difficulty, one can imagine the process of naming concrete objects and actions, as it happened millennia ago. Sound imitation and sound symbolism go a long way toward accounting for the origin of put, screech, squeal, break, crunch, drum, jig-jag-jog, and their likes. Not that one can look at those words and come up with a convincing etymological solution, but at least the impulses behind their creation does not appear to be too mysterious. But what about feel, hear, see, love, and hate?

Hear is especially tough. Before multiplying forms from many languages, I would like to give an example of an unpredictable stumbling block where one does not expect it. The German for “hear” is hören. It is a clear-cut cognate of English hear. Both go back to a form like haus-jan (-jan is the suffix of the infinitive and needn’t bother us), recorded in a fourth-century Gothic Bible (we have no older long consecutive text in Germanic than parts of the New Testament in Gothic). German auf means “on,” and the verb aufhören also exists (auf is a prefix, and hören is the root). Someone who does not know German will, naturally, conclude, that aufhören means “to listen.” But it means “to stop doing something.” As far I can judge, this strange word has never been explained to everybody’s satisfaction. True enough, in the past, hören could also mean “to stop,” and we read in dictionaries that when one wants to hear something, one stops and listens—hence the obsolete sense of hören and aufhören.

Hear! Hear!

Hear! Hear!(By UK Parliament via Flickr)

Perhaps so, but still surprising. Incidentally, hören auf, with auf used as a preposition after hören, means “to obey,” which makes sense: you hear and do what you are told. One expects some connection between a verb of hearing and sound, and this is what we find in English listen, even though the existence of listen, formerly list, is a puzzle: it is rare for hear and listen to derive from different roots. (For instance, Latin audīre means both!) The case of Russian is more typical: slyshat’ “to hear” versus slushat’ “to listen”: vowels alternate in the same root. Listen goes back to hlystan; such is the recorded Old English form. The word is fully opaque as long as we remain in Germanic, but if we remember that by the First Consonant Shift h corresponds to non-Germanic k, help will come from the related English loud, Old English hlūd, whose cognates are Greek klúein “to hear,” Latin cluēre “to be famed,” and so forth.

If even such seemingly transparent words pose problems, one can imagine how hard it is to reconstruct the origin of hear. As usual, the first question is whether hear is limited to Germanic, where its cognates are ubiquitous and, from an etymological point of view, unexciting. Greek a-koú-ein (compare English a-coustics) looks like a tolerably good partner if we succeed in getting rid of a-. This we can do, because even though initial a- in Greek has several functions, it is a prefix and thus plays no decisive role in determining the origin of the root. It will soon become clear why I added decisive to my statement.

Everybody has heard about him, and he is very famous.

Everybody has heard about him, and he is very famous.(Napoleon Bonaparte on the Bridge at Arcole by Antoine-Jean Gros, via Wikimedia Commons)

But what is kou-, the root of the Greek word? Rather probably, it is related to kûdos “honor, fame” (think of English kudos, which British students took over from Greek). The connection between kou– and kû– reminds us of what happed in the history of loud. Apparently, fame comes when something is proclaimed loudly enough, for everyone to hear. If “loud” is indeed the primary element in this semantic chain, we wonder: what is kûd? It does not resemble a typical onomatopoeic root. All other links in Greek, Latin, and Slavic lead us to the sense “notice.” To hear is to notice (fair enough), but, as usual, once we obtain a reliable root, we stop. What is there in the complex kûd or kūd that yielded the idea of hearing or listening? This is the blind alley I have so often discussed in my previous posts. We have a list of roots, but unless they are sound-imitative or sound-symbolic, we are puzzled by what we have found.

Not unexpectedly, the first question students ask when confronted with this array of forms is: “Are ear and hear related?” The two words sound almost alike in several Germanic languages. Etymological algebra separates them, but it is hard to imagine that such a coincidence is fortuitous. Desperate attempts to connect ear and hear exist. We have already come across the word acoustics. If we divide Greek akousio “I hear well” not into a-kous-io but into ak-ous-io (akousma means “hearing; something told; melody; story,” and so forth), with ak– “sharp” (as in Latin: compare English acrid and acrimonious), the desired connection between ear and hear will be restored. (This is why I italicized decisive above!) But this etymology is, most probably, implausible.

Finally, does Latin audire “to hear” and “to listen” throw any light, however dim, on our verb? It too resembles the Latin word for “ear” (auris: consider English aural), though not too closely. The verb is an innovation in Latin and has no etymology. With the perseverance perhaps worthy of a better cause I keep repeating that a word of unknown origin can never elucidate another equally obscure word but let us look at a rather hopeless hypothesis to get out of the impasse. Perhaps, it has been suggested, h- in Gothic hausjan is a prefix (speakers did not drop their h’s at that time—as far as we can judge). Then of course we get the root aus-, which immediately reminds us of Latin auscultare (English auscultate is a learned but recognizable verb), produces a link to audire and Gothic auso “ear,” and solves all problems. But the prefix h-, which would correspond to non-Germanic k-, does not seem to have existed, and we remain where were at the beginning of this paper chase. Slavic and Baltic do not provide any help. Russian slushat’ ~ slyshat’ (see them above) are related to such verbs as English listen and Old High German hlosen “to hear,” and others with l- from -hl.

An auditorium and an audience: both from Latin audire.

An auditorium and an audience: both from Latin audire.(Left: Frederic Köberl on Unsplash; Right: Antenna on Unsplash)

What then is the conclusion? The verb hear has no obvious cognates outside Germanic (also an innovation, as in Latin?). Latin audire is hopelessly isolated. The Greek verb and its cognates have an ascertainable root, but we don’t know why it means “hear” (to us it is just an arbitrary combination of sounds). Though the verb hear bears an almost uncanny resemblance to the noun ear, our vaunted etymological algebra has no means to connect them, though in real life, ears and hearing are connected in the most obvious way.

And now a last nail in the coffin of today’s etymology. Are the verbs hark and harken (hearken is a historically wrong spelling, influenced by hear) related to hear? Not necessarily so, though this conclusion sounds (!) almost incredible. The so-called intensifying (or frequentative) suffix k seems to have existed in Germanic. The same three pairs are always cited: lurk, allegedly from lower “to frown,” walk (from a rather obscure base), and talk from tell. Only the tell ~ talk pair is unobjectionable. Though those k-verbs have cognates in German and beyond, their derivation is rather unclear everywhere. Yet once again we wonder: Is it possible that hear is unrelated to ear and hark is unrelated to hear? How did those words influence one another? Whence this puzzling similarity? Their recorded history has been traced well, but the answer is hidden. Life would have been a dull thing if everything was clear.

Featured image by kyle smith on Unsplash

January 17, 2022

The morality of espionage: do we have a moral duty to spy?

As the Bible’s Book of Numbers tells the story (at 13:17ff), Moses sends out one man from each of the twelve tribes of Israel, with instructions to “go and spy the land” of Canaan. Caleb returns with the favourable news that Canaan is ripe for the taking; the others report that its fortified cities and strong population make it an impossible target. The Israelites decide not to invade the land. As a result, they incur the wrath of God and condemn themselves to wandering in the desert for 40 years—in possibly one of the earliest and most spectacular intelligence failures “on record.”

Ever since Moses, espionage has been an enduring tool of statecraft. As John Le Carré’s iconic character George Smiley vividly tells it,

Why spy? . . . For as long as rogues become leaders, we shall spy. For as long as there are bullies and liars and madmen in the world, we shall spy. For as long as nations compete, and politicians deceive, and tyrants launch conquests, and consumers need resources, and the homeless look for land, and the hungry for food, and the rich for excess, your chosen profession is perfectly secure, I can assure you.

The Secret Pilgrim

Smiley’s description of the world of intelligence is not exactly a ringing endorsement of Le Carré’s own early career as a spy. Smiley and his creator are correct, of course, that governments—and private corporations—shall always spy. In fact, espionage is, at least sometimes, the morally right thing to do—more strongly still, it is a moral duty.

This might seem controversial. Yet, the military strategist and general Sun Tzu offers an unambiguously moral defence of espionage in his classic treatise The Art of War (6 BC). War is so costly to the sovereign’s soldiers and subjects, particularly his poorest subjects, that the sovereign is under an obligation to try and shorten it by acquiring knowledge of the enemy’s intentions and dispositions. Given that the only way to acquire such knowledge is by using spies, a sovereign who refuses to use spies is “completely devoid of humanity.” Closer to us in time, Thomas Hobbes tells us in On the Citizen (1642) that since

“princes are obliged by the law of nature to make every effort to secure the citizens’ safety; it follows not only that they are permitted to send out spies, maintain troops, build fortifications and to exact money for the purpose, but also that they may not do otherwise.”

Sun Tzu and Hobbes focus on rulers’ duty to their subjects and justify it by appealing to the safety and wellbeing of those rulers’ subjects. But there is another justification for it. When our leaders take our country into war, order targeted drone strikes on foreign targets, or impose economic sanctions, they run the risk of causing serious harm to the innocent. They do so on our behalf and in our name, and so owe it to us to minimise that risk, failing which we too, ordinary citizens, will be tarred with the brush of wrongdoing.

Our government also owes it to the targets of its harmful policies to ensure, as far as possible, that it acts on the basis of accurate information. Suppose that our government justifiably seeks to stymie another state’s Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) programme. That state has so far resisted all attempts to inspect its facilities and refused to engage in diplomatic negotiations. Our government concludes that a targeted strike on the building which contains the IT mainframe for the WMD programme would be a necessary, effective, and proportionate response. It has information from one source that the WMD mainframe is located in a particular building, and information from another source that the building hosts the mainframe for that other state’s healthcare system. Only spies located in situ can help our government ascertain what the site is.

Let us suppose that the site contains the mainframe for the healthcare system. If our government orders its bombing, thousands of patients who depend on the good functioning of the mainframe will be grievously harmed and civilian IT workers will be killed. If it orders the bombing without sending spies out to check even though it is in a position to do so, it will unnecessarily subject those individuals to the risk of being killed unwarrantedly. Deliberately killing the innocent grievously wrongs them; doing so when one did not need to do so is much worse.

Is this to say, then, that intelligence agencies and their operatives ought to be given a free moral run? That they can deceive, coerce, blackmail, and exploit their targets with impunity? That their paymasters too can deceive and launch conquests? Certainly not. Just as there are moral limits on war, so there are moral limits on what governments can legitimately ask Smiley and his people to do. The fact that those limits might be observed in the breach as well as (more than?) in the observance does not make them any less stringent. But nor does it absolve our government of its duty to spy.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers