Oxford University Press's Blog, page 83

March 11, 2022

Five books to celebrate British Science Week

British Science Week is a ten-day celebration of science, technology, engineering and maths, taking place between 11-20 March 2022. To celebrate, join in the conversation, and keep abreast of the latest in science, delve into our reading list. It contains five of our latest books on evolutionary biology, the magic of mathematics, artificial intelligence, and more.

1. The Parrot in the Mirror: How evolving to be like birds made us human

How similar are your choices, behaviours, and lifestyle to those of a parrot?

Discover how many of our defining human traits are far more similar to birds than to our fellow mammals in The Parrot in the Mirror, by Antone Martinho-Truswell. From our lifespans to our intelligence, our relationships and our language, we can learn a great deal about ourselves by thinking of the human species as “the bird without feathers.” In this insightful read, learn more about how parrots, specifically, are our biological mirror image; an evolutionary parallel to ourselves. And how they are the only species to share one particular human trait: spite.

Read The Parrot in the Mirror: How evolving to be like birds made us human.

To learn more about how, much like humans, the senses of animals are key to their survival, discover Secret Worlds: The extraordinary senses of animals, by Martin Stevens.

2. Mind Shift: How culture transformed the human brain

The mental capacities of the human mind far outstrip those of other animals. Our imaginations and creativity have produced art, music, and literature; built bridges and cathedrals; enabled us to probe distant galaxies, and to ponder the meaning of our existence. What makes the human brain unique, and able to generate such a rich mental life? In this book, John Parrington draws on the latest research on the human brain to show how it differs strikingly from those of other animals in its structure and function at a molecular and cellular level. And he argues that this “shift,” was driven by tool use, but especially by the development of one remarkable tool—language.

Read Mind Shift: How culture transformed the human brain .

You can also read Parrington blog on what neuroscience can tell us about the mind of a serial killer, as well as listening to his podcast on culture and the human brain.

3. Colliding Worlds: How cosmic encounters shaped planets and life

In Colliding Worlds, Simone Marchi explores the key role that collisions in space have played in the formation and evolution of our solar system, the development of planets, and possibly even the origin of life on Earth. Analysing our latest understanding of the surfaces of Mars and Venus, gleaned from recent space missions, Marchi presents the dramatic story of cosmic collisions and their legacies. You can also read his blog’s on the Earth’s wild years and the creative destruction of cosmic encounters, as well as his response to Netflix’s “Don’t Look Up!” satire, Do Look Up! Could a comet really kill us all?

Read Colliding Worlds: How cosmic encounters shaped planets and life.

To learn more, discover our Very Short Introductions series, including Planetary Systems, Climate Change, Evolution, Human Evolution, and The Animal Kingdom.

4. The Wonderful Book of Geometry: A mathematical story

How can we be sure that Pythagoras’s theorem is really true? Why is the “angle in a semicircle” always 90 degrees? And how can tangents help determine the speed of a bullet?

David Acheson takes the reader on a highly illustrated tour through the history of geometry, from ancient Greece to the present day. He emphasizes throughout elegant deduction and practical applications, and argues that geometry can offer the quickest route to the whole spirit of mathematics at its best. Along the way, we encounter the quirky and the unexpected, meet the great personalities involved, and uncover some of the loveliest surprises in mathematics.

Read The Wonderful Book of Geometry: A mathematic a l story .

Take a sneak peek inside, and listen to Acheson explain the magic of geometry.

5. Human-centered AI

Focusing not on the risks of AI, but on the opportunities it presents and how to capitalize on them, Ben Shneiderman puts forward 15 recommendations about how programmers, business leaders, educators, professionals, and policy makers can implement human-centered AI. Bridging the gap between ethical considerations and practical realities to make successful, reliable systems, Schneiderman provides a range of human-centered AI design metaphors to show ways to get beyond current limitations and see new design possibilities that empower people, giving humans control.

Read Human-centered AI .

To learn more, discover our What Everyone Needs to Know® series, including titles on Artificial Intelligence (and a blog post on What is Artificial Intelligence?), and Evolution.

As an added bonus, you can also read more on the topics of evolutionary biology, the magic of mathematics, and artificial intelligence with the Oxford Landmark Science series. Including “must-read” modern science and big ideas that have shaped the way we think, browse the series here:

You can also explore more titles via our extended reading list via Bookshop UK.

New York City: the streams and waterways of Manhattan

In the 1830s, New York was a small city. While the island of Manhattan had a prosperous community at its southern end, its northern area contained farms, villages, streams, and woods. Then on the evening of 16 December 1835, a fire broke out near Wall Street. It swept away 674 buildings and though the devastation seemed absolute, citizens quickly rebuilt. They pushed development up the island, so that by the Civil War homes lined the streets near the new Central Park.

Learn about the Great Fire of 1835, and the city that existed before and grew after that blaze in this series of blog posts from Daniel S. Levy, author of Manhattan Phoenix: The Great Fire of 1835 and the Emergence of Modern New York.

The streams and waterways of ManhattanWe think of New York as an island packed with buildings, a place of concrete sidewalks and tarmacked avenues, a city that, as Frank Sinatra sang, “doesn’t sleep.” But Manhattan at the turn of the 19th century—in the years before its street grid was laid out and decades before the Great Fire of 1835, which would accelerate the city’s northward growth—was a very different sort of place. New York City back then was a sleepy town just on the island of Manhattan. The five boroughs—Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island—did not consolidate into Greater New York until 1898. And while there were a few scattered communities as well as farms and estates to the north of 14th Street, the main community sat on the southern tip of the island.

Much of Manhattan in the late 18th and early 19th century was still a wild place. Forests and marshes blanketed parts of the surface. The Lenapes lived here before the Dutch arrived, and these native Americans called their land Manahatta, which possibly means “Island of Many Hills” or “the place where we get bows.” Both names seem appropriate. Woods were dense with maples, chestnuts, beech, hickory, oak, and birches, and its abundance of wood served as a good source for weaponry. And the island was covered by 573 hills. Some like Bayard’s Mount in the area of current day Foley’s Square, were quite large, with lawyer William Duer writing how it “rose gradually from its margin to the height of one hundred feet.” Further uptown ran a string of sand hills, which the Dutch called Zandtberg. Harlem meanwhile had fertile meadows and plains.

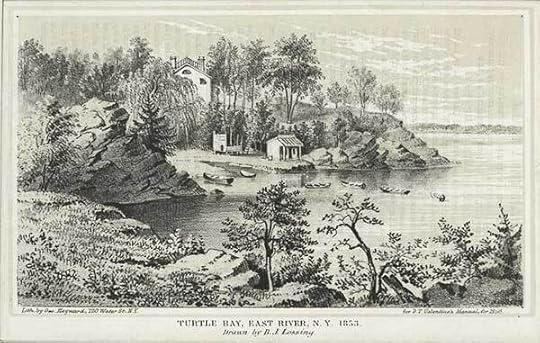

Turtle Bay, the area where the United Nations now stands, gets its name from a turtle-filled cove along the edge of the East River.

Turtle Bay, the area where the United Nations now stands, gets its name from a turtle-filled cove along the edge of the East River.(Turtle Bay, NYPL)

Thick berry bushes covered the ground, and the land was populated with deer and elk, as well as an occasional wolf, bear, and cougar. Beavers lived in the marshes, while wood ducks splashed in the ponds, and passenger pigeons blackened the sky. Parts of the island were water-logged, and the area of current day Pearl Street was a swampy meadow inhabited by partridges and heath hens.

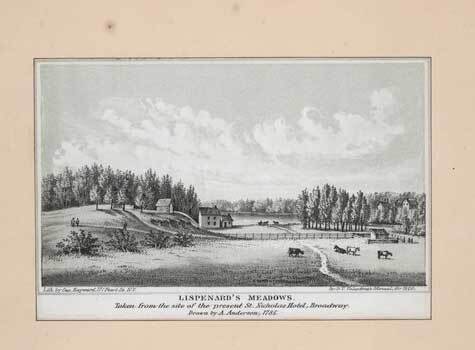

The island had 21 ponds and salt pannes, and near Bayard’s Mount stretched the Collect, a kettle pond that was created by glacial melt water. Its name is a corruption of the Kalch Hoek, Dutch for lime point, a name the settlers bestowed on the body of water after they came across large mounds of oyster shells left by the Lenapes. In the water lived killifishes and yellow-bellied cobblers. Future mayor Daniel Tiemann recalled how “We used to catch perch, sunfish, and eels in this lake in Summer.” To the west lay Lispenard’s Meadow where Tribeca now stretches, a marsh with pools and swamps, bulrushes and brambles, and filled with water snakes and bullfrogs. Other areas like Stuyvesant’s Meadows in the current-day East Village were lined with cattails, bladderworts, duckweed, water lilies, and pondweeds.

Lispenard’s Meadow, a swampy land filled with marshes, snakes and bullfrogs, used to cover the area now known as Tribeca.

Lispenard’s Meadow, a swampy land filled with marshes, snakes and bullfrogs, used to cover the area now known as Tribeca.(Lispenard’s Meadow, NYPL)

Springs dotted the surface. Author Washington Irving wrote how the center of the island has “a sweet and rural valley, beautified with many a bright wild flower, refreshed by many a pure streamlet.” Sixty-six miles of these waterways flowed through the island. Two of them met up at Sixth Ave. and 12th Street and flowed south and through what would become Washington Square Park. The Dutch called it Bestevaer’s Killetje, while the English named it Minetta Brook. Trout coursed in the waterway. Before it flowed into the Hudson River, it ran alongside Aaron Burr’s home on Richmond Hill. There the nation’s third vice president formed Burr’s Pond, on which his beloved daughter Theodosia loved to skate.

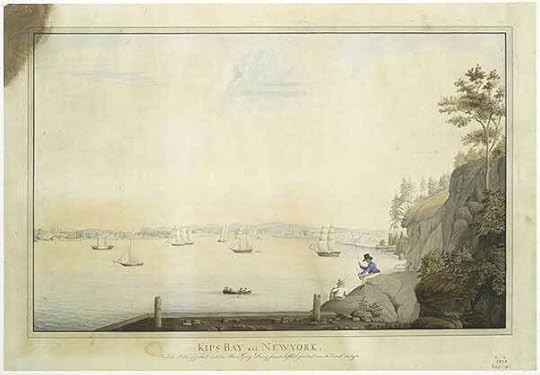

A stream started around Fifth Avenue and 46th Street and ran into Kip’s Bay. Another one began at Broadway and 44th Street and expanded at Madison Avenue in the lower 30s into Sun Fish Pond. It proved popular for fishermen. Children collected hickory nuts from the trees along its edges. To the north in the 40s lay Turtle Bay, named for a turtle-filled cove, which sat on the edge of the East River, a tidal estuary with porpoises, seals, and whales. Further up the island, there were such water sources as the Kill of Schepmoes, Unquenchable Spring, Montayne’s Rivulet, and Sherman Creek.

Kip’s Bay on the East River is where at the start of the American Revolution British troops landed and routed George Washington and his troops.

Kip’s Bay on the East River is where at the start of the American Revolution British troops landed and routed George Washington and his troops.(Kip’s Bay 1830, NYPL)

The British military occupied New York during the Revolutionary War. After they departed in 1783, citizens started settling to the north, as developers began straightening out and widening the town’s paths and laying out streets. In the process, property owners filled in streams, marshes, and ponds. By the early 19th century, the city had cut down the trees around the Collect and filled the body of water and nearby marsh. Bayard’s Mount was leveled and pushed into the Collect, and Lispenard’s Meadow dried out.

Then, in 1811, the city fathers decided on a grid pattern for orderly development above Houston Street. The town started selling parcels of public land, while families quickly divided up their farms and estates and offered building lots. Within five decades, settled streets had reached three miles north up to the newly created Central Park. Work had begun on the park in the mid 1850s, and by the time of the Civil War it had become a beloved and much needed refuge in a city that continued to give preference to development over nature.

March 9, 2022

Religious terminology: further benefits of blessing and the devious ways of cursing

Last week, we looked at the attempts to derive the English verb bless from Latin benidicere and from English blithe and bliss, and concluded that those approaches should, most probably or even certainly, be abandoned, even though at first sight, the bless ~ blithe idea looks reasonable. To exacerbate the problem, the only other answer to the question about the etymology of bless seemed to be: “Origin unknown.” In all fairness, it should be noted that our first English etymologist John Minsheu (1617) and a few others derived bless from Old English blōtan “to sacrifice.” The connection is attractive. Blōtan has cognates elsewhere in Germanic, and it may be related to Latin flāmen “sacrificial priest.” But modern philologists balked at the incompatibility of the final consonants s and t in the roots. In the seventeenth and even in the eighteenth century, such niceties did not bother anyone. However, for some reason, blithe, rather than blōtan, dominated the scene for many years.

Walter W. Skeat’s etymological dictionary was published in fascicles (installments), like the OED and all the major dictionaries of that time. Skeat accepted the bless ~ blithe idea, but in 1879, when the first fascicle of the dictionary appeared (naturally, the letter B was there), Henry Sweet, one of the founders of the history of English as a reliable branch of scholarship, published a review of that fascicle. In it, he excoriated Skeat for his neglect of phonetic correspondences, traced bless to the root of the word blood, and explainedthe verb as meaning “to redden with blood.” Here, as below, I’ll skip the phonetic basis of this hypothesis. Naturally, a specialist of Sweet’s caliber considered every detail of his reconstruction.

In a state of absolute bliss.

In a state of absolute bliss.(By Joe Ciciarelli on Unsplash)

From a semantic point of view, both ideas (bless from blithe and bless from blōtan) make sense, but as already noted, because of the seeming incompatibility of final t and s no one took Minsheu’s idea seriously. Nor can the old roots of blithe and bliss, one with long i (ī), the other with short e, be reduced to the same protoroot (those vowels do not alternate by ablaut). Skeat concluded work on the first edition of his dictionary with a traditional list of corrections and additions. Pugnacious and inflexible as he was, he admitted that the explanation of bless in the main body of the dictionary was “entirely wrong” and referred to Sweet’s publication. Later, Sweet returned to his etymology of the word bless in two short articles.

Four editions of Skeat’s dictionary exist, but the first three are reprints. He used to revise his etymologies in the Concise versions of his great work. Sweet’s etymology was incorporated into the main text only of the last, fourth, edition. The early versions are available online, and I suspect that the people who use them seldom bother to open the supplement. This caveat is also valid for many other important dictionaries: quite often, only the earlier versions appear in digital form, which is better than nothing, but such outdated sources should be consulted with caution.

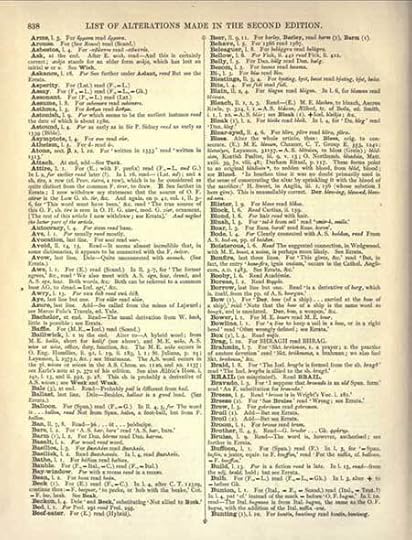

The contrite Walter W. Skeat.

The contrite Walter W. Skeat.(Page 838, An etymological dictionary of the English language, via archive.org)

Sweet’s etymology found universal acceptance. However, since 1879, a good deal has been written on the origin of English words. Unfortunately, as I mentioned last week, remarks on this subject in fugitive publications, especially in languages outside the magic circle of English-German-French (and even that circle is sometimes hard to square) disappear without a trace. At present, relatively few people study the etymology of English as their main subject. Hittite and Tocharian are more “prestigious” and attractive. Perhaps somewhere, in an article on Tocharian B, a chance remark on an English cognate may turn up, but who will look for it there? Unlike what happened in the nineteenth century, philological journals do not print word indexes in the supplement to each volume.

In the twentieth century, attempts to revive the blōtan-bless etymology have been made twice: once in Swedish, the other time in German, but for decades even the most authoritative sources available on the Internet kept copying the solution offered in the early edition of the OED. James A. H. Murray, the OED’s first great editor, of course knew all the relevant literature but preferred to side with Sweet, as Skeat had done before him. The first volume of the OED appeared in 1884. Only now the gigantic work of revising the dictionary is underway (see below).

Hermann Flasdieck, the author of the most detailed critic of Sweet’s etymology, paid special attention to the phonetic difficulty (final t in blōtan versus final s in bless), but let me repeat: discussing such details here will take me too far afield. Flasdieck’s reconstruction looks solid, and it convinced at least two serious language historians in Germany. I am not sure whether there have been any recent publications on the history of bless, but much to my satisfaction, the OED online has taken cognizance of Flasdieck’s contribution. It gives no references, chooses not to take sides in the argument, and cites both derivations as equally plausible. I prefer the blōtan solution.

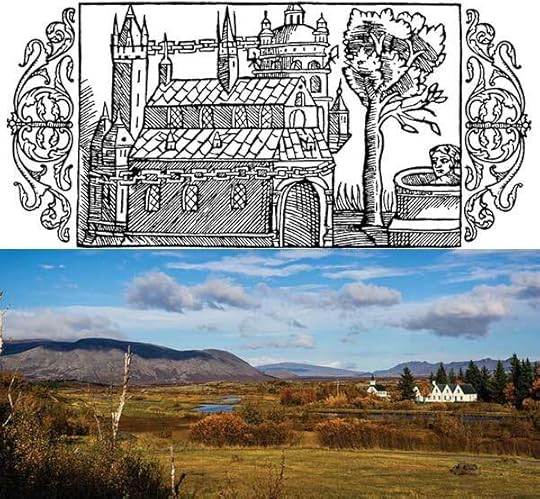

A pre-Christian Scandinavian temple and a modern view of the medieval Icelandic Fields of Parliament (Thingvellir), with a modern church in the background.

A pre-Christian Scandinavian temple and a modern view of the medieval Icelandic Fields of Parliament (Thingvellir), with a modern church in the background.(Top: the temple at Old Uppsala, via Wikimedia Commons. Bottom: Thingvellir National Park, Iceland, by Jason Krieger on Unsplash)

Be that as it may, the history of bless need not be reduced to its relation with blōtan. The problem was clear to Friedrich Kluge (see the previous post), though no one seems to have paid attention to his statement. Whether from blood or blōtan, bless will end up as a word reminiscent of pagan practices. Christian missionaries made great efforts to coin terms that evoked no associations with traditional rites and places of pagan worship. This is how the word church came into existence (words for pagan temples were numerous). God, whatever its etymology, was as obscure to the Germanic speakers as it is today and must have lost all ties with heathen practices by the time of the conversion. But why, in contrast to their neighbors, did the Anglo-Saxons save blōtan from extinction? We also wonder whether a thousand or so years ago, the speakers of Old English connected their verb blēdsian with blōd “blood” or with blōtan? The words sounded so much alike that the proximity could not escape the speakers, let alone the learned clerics who were responsible for creating the vocabulary of Christianity.

Obviously, we will never know the answers to such questions: there is no one to ask. But I cannot refrain from mentioning the fact that curse is another religious term not resembling its counterparts in the languages of the continent. One of the reason may be that English clerics, especially in the north, worked in close contact with their Irish colleagues. Let us not forget that Christianity came to England not only from Rome but from the already converted “barbarians.” There may have been a deliberate effort to use the vocabulary different from that of the “Germans.” In the history of bless, no Celtic influence can be detected, but curse, another important religious term, rather probably, goes back to cursus, the Latin formula of excommunication. It seems to have merged with a borrowing of OldIrish cúrsagad “reprimand” and yielded the modern form, which then is a blend. By the way, cross also reached England from Ireland.

Inscrutable are the ways of religious terminology.

Feature image by Tomasz Filipek on Unsplash

March 8, 2022

International Women’s Day: feminist philosophy with Clara Zetkin

8 March. A day to celebrate womanhood and women’s achievement? A day to protest regional and global gender injustice and call for radical change? 8 March is now a holiday adopted by the United Nations and marked across different continents, time zones, and political affiliations. It has become a day for all and thus, some worry, a day for no one.

Clara Zetkin (1857-1933) was not up for compromises. A German delegate at the International Socialist Women’s conference in Copenhagen in 1910, Zetkin was instrumental in establishing International Women’s Day. It did not take long to catch on. The following year International Women’s Day was marked by over a million people taking to the streets.

Zetkin, though, kept seeing International Women’s Day as an occasion to mark the fight against the sufferings of working women who confront illness, epidemics, death, poverty, violence, and imperialistic wars––sometimes, as she puts it, “with the aid and blessing of ‘democracy’.” The day must be international, she argued, because these sufferings are shared by all the oppressed, regardless of national borders. It is women’s day because, in her words, the inhuman burden of global capitalism weighs with especial heaviness on women.

In an age where women could not yet vote, Zetkin positioned herself as a flaming feminist within the socialist movement. For her, 8 March was a day that was and had to be politically motivated. It was not an occasion for joyful celebration, but a day to remind ourselves—through taking to the streets and articulating an uncompromising will not to give up fighting—that the struggle for equality is not won until every woman can assume safety, health, and equal work opportunities (and thus be in a situation in which womanhood can be celebrated).

Clara Zetkin during a congress in Zurich 1897

Clara Zetkin during a congress in Zurich 1897(By Gilbert Badia via Wikimedia Commons)

How, one could ask, did Zetkin square her feminist and socialist engagements? Wouldn’t her Marxist commitments bind her to fight for universal abolishment of private property rather than the improvement of the conditions for a particular group (in this case: women)? Zetkin grappled with questions around class and gender—which one should get priority? Do we need to prioritize the fight for one over the other?—all her life. In this sense, her writings investigate a series of arguments and positions that maneuver the difficult line between gender solidarity and solidarity with oppressed peoples regardless of gender. Assessments of her position, even her own assessment of her position (!), often take the form of checking it against the parameters of Marx’s thinking. This, though, is not the only context in which Zetkin’s work should be read. Indeed, this kind of reading betrays a blind spot in the history of women thinkers: to the extent that they are at all recognized as substantial contributors, their thoughts are related to a canonical male figure.

As a political thinker and activist, Zetkin positions herself in the wake of Marx, Engels, and other socialist luminaries. She should, however, also be placed within the context of a strong lineage of women thinkers to whom philosophy was an important and indisputable vehicle for social change. Zetkin’s friendship with Rosa Luxemburg is well-known. Less well-known is the formative role played by Louise Otto-Peters and Auguste Schmidt, whose institute in Leipzig Zetkin attended. Moreover, Zetkin follows and radicalizes the lead of Bettine Brentano-von Arnim, whose late work addresses poverty, class, illness, and political violence. We can also helpfully situate her contribution with respect to Hedwig Dohm’s critique of a biological notion of gender and the tendency to view women in light of their reproductive capacity.

Gender injustice, social issues, incarceration politics, war, and imperialism are just some issues women philosophers address in the nineteenth century—and address with force, consistency, and convincing arguments. Excluded from university positions, these women did not write for an audience of academic colleagues. They did not produce theoretical systems—and yet their work can help us think through central issues in a way that is both profound and systematic.

Placed within this line of philosophers, Zetkin’s contribution is clear: she offers a non-essentialist, non-biologist approach to gender, she delivers sharp arguments in favor of equal pay, voting rights, and education. She is among the first to analyze the challenges of intersectionality. Moreover, her focus on women’s rights—against the background of which her work for International Women’s Day emerged—should be understood with respect to a larger engagement for the oppressed. It is from this point of view that Zetkin engages systemic racism in the US. It is, moreover, from this position that she discusses child poverty and exploitation. And it is from this point of view that she, from the early 1920s onwards, bravely takes on fascism both in its budding and manifest forms.

The question, thus, is not to what extent her work is in line with socialist doctrines, but, rather, “what we can learn from this nineteenth-century philosopher?” And concerning 8 March and International Women’s Day, one of the takeaways from Clara Zetkin is that once her work is read within a broader context of women’s philosophical contribution, there is no tension between a radical fight for women’s rights and living conditions and a universalist analysis of oppression in its many shapes and forms. For Zetkin, 8 March could never be a celebration of womanhood. It was, instead, part of a sustained fight for a society under which women, of all colors and walks of life, could lead genuinely human lives. Her mission was radical; her message was universal.

Featured image by Miguel Bruna on Unsplash

Tawnie Olson: re-imagining the Magnificat

Considering how important she is to Christianity, it is surprising how little information the New Testament provides about the Blessed Virgin Mary. This is despite the fact that, even during Jesus’s lifetime, people held strong opinions about her. According to St. Luke, Christ’s preaching was once interrupted by a follower who shouted: “Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts that nursed you!” To which Jesus gave the quelling reply, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it!” (Luke 11:27,28 NRSV).

Over the centuries, Jesus’s suggestion that Christians focus on our relationship with God, rather than speculate about Christ’s earthly family, has been widely ignored. Theologically, artistically, poetically, and musically, we have not been able to resist filling in the enormous gaps in the Gospels’ accounts of Mary with our own ideas about what a woman worthy of bearing the Son of God must have been like. Sometimes, in our zeal to project our conceptions of The Ideal Woman onto this enigmatic first-century figure, we’ve strayed a bit from the little we do know.

Sandro Botticelli’s Madonna of the Magnificat, for example, portrays Mary as a stylish blonde Florentine aristocrat, surrounded by refined angel/courtiers as she coolly pens the Magnificat with one hand and dandles the infant Jesus in the other. It is a beautiful painting, far beyond my ability to praise adequately, but somehow, I just can’t imagine the woman it depicts giving birth in a barn.

Madonna of the Magnificat, Sandro Botticelli

Madonna of the Magnificat, Sandro Botticelli(Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Composers are, of course, no less guilty of projection than are painters. Several years ago, a choir in which I sang premiered a piece by a successful male composer. The music and text combined to suggest a Blessed Virgin who was inoffensively meek, sweet, and… small. I had a hard time reconciling this Mary with the woman who, in the Gospel of John, firmly overrules the Son of God, ignoring his ineffectual protests and “persuading” Christ to save the wedding at Cana by performing his first miracle.

I was not the only singer who found this composer’s vision unsatisfying. After one rehearsal, a normally-reserved alto named Karen Clute walked up to me and fumed, “Tawnie, you have to compose a feminist Magnificat!” And to my everlasting gratitude, she commissioned me to do just that.

When we met to discuss the prospective piece, we talked about the Mary we saw in Scripture: someone brave, thoughtful, and (at times) intimidating. We discussed the gap between this Mary and the sweet young thing in a blue dress we’d seen in too many paintings. We also talked about girls Mary’s age and how they, too, display grace, intelligence, and courage that our North American culture tends to ignore, perceiving and depicting them as merely shallow and petty (the phrase “like a teenaged girl” is not generally used as a compliment). Karen specially requested that my Magnificat setting be dedicated “to strong teenaged girls everywhere.”

As we spoke, I realized that I should compose my Magnificat for the Elm City Girls Choir, an organization whose founding mission is to provide girls with superb musical training, confidence, and leadership skills. The ensemble sings classical music beautifully, but they also excel at singing in the style of professional Bulgarian women’s choruses.

“My Magnificat isn’t just about Mary, however; it is also about how the rest of us relate to her and, by extension, to young women.”

In Bulgaria, singing has traditionally been the domain of women, whose vocalizing is characterized by a wide dynamic range (including a powerful fortissimo), chest voice, forward resonance, and the use of drones. When Bulgaria was a communist country, the government supported a number of professional women’s choruses who sang sophisticated folk tune arrangements in a polished version of the traditional singing style. It is not for me to say how these choruses are perceived by Bulgarians, but to me and to many other Westerners, their beautiful, intense sounds evoke feminine strength and power. This is the Mary I see in the New Testament, my Ideal Woman. She was not, of course, Bulgarian, but she was a formidable young woman who, in the Magnificat, celebrated God’s radical overturning of social order.

My Magnificat isn’t just about Mary, however; it is also about how the rest of us relate to her and, by extension, to young women. In my piece, a classical SATB chorus (at the premiere, the Yale Schola Cantorum) sings the text of the Ave Maria, supporting and responding to the Magnificat text sung in Bulgarian style by the upper voices.

The piece opens with the upper voices singing “Magnificat anima mea Dominum” (my soul magnifies the Lord). The adult chorus softly sustains the resonance of this melody, and from this resonance emerge the words “Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum” (Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with you); their recognition of Mary flows organically out of their echo of her praise for God. After Mary’s words “ecce enim ex hoc beata me dicent omnes generationes” (for behold, from henceforth all generations will call me blessed), the basses and second tenors softly chant “Benedicta tu in mulieribus” (blessed are you among women), a chant that spreads from section to section, swelling until it fills the SATB chorus in a musical depiction of the reverence for Mary passed down and growing from generation to generation. Toward the end of the piece, as the upper voices sing of the mighty cast down from their seats, the SATB chorus sings “ora pro nobis peccatoribus” (pray for us sinners). I hope that in life, as in this piece, we can increasingly recognize and praise the strength and courage both of Mary and of young women.

March 7, 2022

Inky thumbprints: what common women can tell us about reading, relationships, and resisting anti-intellectualism

In communities and state legislatures across the United States, there is a concerted movement underway to limit the kinds of ideas to which students are exposed. Often hidden behind claims to parental rights, balanced treatment, and a desire to avoid division, these efforts target students’ ability to think freely, to ask probing questions, and to engage with long-overdue reckonings with the past. In some communities these efforts have resulted in books on topics such as anti-racism, the Holocaust, and gender non-conformity being banned. The assumption seems to be that if ideas that bend the arc of history further towards justice can be eliminated from classrooms, they can be eliminated from the culture—that education is at odds with our most intimate domestic spaces and familial relationships. In fact, what history bears out time and again is that the pursuit of intellectual freedom is the most “kitchen table” of issues—a lesson we would be wise to remember as we explore the intellectual lives of non-elite and BIPOC women across the centuries.

In the Parliamentary Archives, there is a manuscript, confiscated in August 1646 when agents of the Stationers Company on order from the House of Lords arrested the Leveller Richard Overton for seditious printing. Riddled with editorial changes and inky thumbprints, the manuscript and its history stand as mute testimony to the dynamic nature of ideas and the domestic nature of justice. At least some of those thumbprints belong to Richard Overton, who printed the pamphlet. The neat hand that produced the fair copy has not been definitively identified, though it bears some resemblance to his wife Mary’s signature. As much as we remain uncertain about the material details of the manuscript, we are very certain that the Stationers agents who arrested Richard Overton viewed the couple’s most intimate spaces as an important source of intellectual dissidence.

“What history bears out time and again is that the pursuit of intellectual freedom is the most “kitchen table” of issues”

Sadly, the couple paid an equally intimate and more devastating price for their resistance to censorship. While her husband remained in Newgate prison, Mary and other members of her family continued the work of distributing dissident pamphlets undeterred until she and her brother were themselves arrested. Parliament committed Mary and the baby to which she’d given birth the summer before to Bridewell, where the baby died. Richard Overton memorialized Mary’s imprisonment and the loss of their child by proclaiming her one of the many “Commoners Wives who stand for their freedom and liberty.”

Whether we are talking about Alice Walker’s mother’s garden, Elizabeth Lilburne’s unsigned contributions to Leveller pamphlets, Joy Harjo’s kitchen table, where “children are given instructions on what it means to be human,” women have found ways to challenge, if not wholly cast off, the constraints on their minds and the minds of those they hold closest often in the most surprising ways. My own grandmother was a child of the Great Depression, the only surviving girl in a family six surviving children. A brother and a sister succumbed to illness, while a second brother died in a tragic household accident. Her constant refrain, as soon as she judged me old enough to hear it, was that her parents had too many children. There was seldom money for even the smallest of luxuries and never money for education. As soon as she was old enough to work, she did, noting at one point that she worked the night shift at the local canning factory because the men took the dayshifts. Towards the end of her life, she began to journal, writing down memories and admissions, including the admission that she had chosen to terminate two, unplanned pregnancies.

“Women have found ways to challenge, if not wholly cast off, the constraints on their minds and the minds of those they hold closest often in the most surprising ways.”

For my grandmother, this was her truth. No family should have more children than they wanted or for which they could provide. Neither of my grandparents went to college, but they valued education above all else. And although they lacked the resources to pay for my mother’s and my uncle’s educations entirely, all their children went to college, producing four master’s degrees and a Ph.D. My mother and my uncles were supported emotionally and materially when it was possible. The simple truth is that my grandmother’s decision to terminate those pregnancies made those degrees possible. The other simple truth is that my grandmother terminated those pregnancies when abortions were still illegal in the state where she lived. Not everyone will see her choice in this way, but for me, those terminations were acts of political defiance and became part of her own personal fight for her children’s educations, their abilities to ask probing questions, and to bend the arc of history a little closer to justice.

In the frenzied onslaught against intellectual inquiry we should not forget that the fight against the benighted forces of ignorance takes place in humble settings among women with fierce clarity. We should forget this neither as a historical proposition about where to look for evidence of past struggles, nor should we forget this as a guide for current practice. Anti-intellectualism tends to be episodic; the work of intellectual inquiry is ongoing, domestic, and intimate.

Feature image by Gareth David on Unsplash

A silver thread through history [video]

With a history spanning back over 2,000 years, coins are much more than just money. They are also a means of storing and communicating information, resembling tiny discs of information technology that convey images and text across vast swatches of time and territory. Coins are the first world wide web linking us together. While they can be made from many materials including gold, plastic, copper, and even cardboard, the most common material throughout history has been silver; looking carefully you can see this silver thread running through history linking the past and the present.

Watch the video with Frank L. Holt, author of Money Talks, to follow the silver thread and unravel the history of coins.

March 6, 2022

Letting foregones be bygones

I was reading a column in a chess magazine when I came across the description of a game’s finish as a bygone conclusion. “That’s really weird,” I thought, “It should have said foregone conclusion.”

Bygone, it turns out, is a Scottish word according to the OED, and it refers to things in the past. Bygone days are days gone by. As a noun, it can mean past offenses, as in the phrase “Let bygones be bygones” (or as we would say today “Get over it”). A foregone conclusion is one that is apparent in advance—before events, evidence, or actions.

I searched around a bit and it turns out that bygone conclusion in place of foregone conclusion is not a one-off mistake. A colleague even offered up an example from a novel by Henrietta Keddie, the nineteenth century Scottish novelist who wrote under the pseudonym Sarah Tytler. Her 1859 novel The Nut-Brown Maids has the line “Lee protested vehemently against this bygone conclusion.” A search of Newspapers.com brings up over a hundred examples of the expression from as early as 1831 (in the Caledonian Mercury in Scotland) to present day.

Bygone conclusion does not seem like an ordinary malapropism, like referring to the pineapple of success rather than pinnacle of success (as Richard Sheridan’s character Mrs Malaprop did in the eighteenth-century play The Rivals). Malapropisms usually create nonsensical meanings and are used for comic effect, often to lampoon a pontificating blowhard. An example is television’s Archie Bunker with his reference to someone sitting in an “ivory shower” and to a “lowly pheasant” serving the king.

Malapropisms occur in real life as well, either from a mislearned word or from a momentary word retrieval error, as when someone refers to returning books to the strawberry rather than the library or calls the garbage disposal the vacuum cleaner.

The phrase bygone conclusion is what is known as an eggcorn rather than a malapropism. An eggcorn is a similar concept, but involves a substitution that makes sense. If you are wondering about the term, eggcorn is an eggcorn of acorn, replacing an opaque word with a more transparent one. One of my favorite eggcorns is the phrase blasé-faire, which nicely captures the essence of laissez-faire. For all intensive purposes, nipping something in the butt, being an escape goat—eggcorns all.

How is bygone conclusion an eggcorn of foregone conclusion?

For some, the meaning “a conclusion determined beforehand” fits equally well (or better) with the “before” sense of bygone than with the semantically opaque foregone. To make sense of foregone conclusion, one needs to reverse engineer its parts as “a conclusion determined beforehand.” Since both foregone and bygone share the part gone, it is a logical enough substitution, much like blasé for laissez.

The phrase bygone conclusion is stuck in my head now, and I may drop it into conversations now and then to see how people react.

Feature image: “Ajedrez de Bolsillo” by Armando Olivo Martín del Campo. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

March 4, 2022

Ten new books to read this Women’s History Month [reading list]

Since 1987, Women’s History Month has been observed in the US annually each March as an opportunity to highlight the contributions of women to events in history and contemporary society. This month, we’re sharing some of the latest history titles covering a range of eras and regions but all charting the lives of women and the impact they made, whether noticed at the time or from the shadows.

Dissenting Daughters: Reformed Women in the Dutch Republic, 1572-1725 by Amanda C. PipkinDissenting Daughters reveals that devout women made vital contributions to the spread and practice of the Reformed faith in the Dutch Republic in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The six women at the heart of this study—Cornelia Teellinck, Susanna Teellinck, Anna Maria van Schurman, Sara Nevius, Cornelia Leydekker, and Henrica van Hoolwerff—were influential members of networks known for supporting a religious revival known as the Further Reformation.

Read: Dissenting Daughters

Cleopatra’s Daughter: and Other Royal Women of the Augustan Era by Duane W. RollerThis is the first study of the royal women who ruled in the Mediterranean in the latter half of the first century BC , in a symbiotic relationship with the Roman government. Several are discussed, with the most prominent being Cleopatra Selene (the daughter of the famous Cleopatra VII of Egypt) and Salome, the sister of Herod the Great.

Read: Cleopatra’s Daughter, now new in paperback

The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America by Nancy E. Davis

The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America by Nancy E. DavisIn 1834, a young Chinese woman named Afong Moy arrived in America, her bound feet stepping ashore in New York City. She was both a prized guest and advertisement for a merchant firm—a promotional curiosity used to peddle exotic wares from the East. Over the next few years, she would shape Americans’ impressions of China even as she assisted her merchant sponsors in selling the largest quantities of Chinese goods yet imported for the burgeoning American market.

Read: The Chinese Lady, now new in paperback.

Propaganda, Gender, and Cultural Power: Projections and Perceptions of France in Britain c1880-1944 by Charlotte FaucherCharlotte Faucher analyses the powerful motivations that fueled members of civil society, and in particular women, to dedicate their resources in the pursuit of improving the image of France in Britain through cultural strategies.

Read: Propaganda, Gender, and Cultural Power

Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States by Laura F. Edwards

Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States by Laura F. EdwardsWhat can dresses, bedlinens, waistcoats, pantaloons, shoes, and kerchiefs tell us about the legal status of the least powerful members of American society? In the hands of eminent historian Laura F. Edwards, these textiles tell a revealing story of ordinary people and how they made use of their material goods’ economic and legal value in the period between the Revolution and the Civil War.

Read: Only the Clothes on Her Back

Fulvia: Playing for Power at the End of the Roman Republic by Celia E. SchultzFulvia is the first full-length biography focused solely on Fulvia, daughter of Sempronia and Bambalio, who is best known as the wife of Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony). It peels away the heavily biased accounts of her to reveal a strong-willed, independent woman who was, by many traditional measures, a successful Roman matron.

Read: Fulvia

The Voices of Nîmes: Women, Sex, and Marriage in Reformation Languedoc by Suzannah Lipscomb

The Voices of Nîmes: Women, Sex, and Marriage in Reformation Languedoc by Suzannah LipscombFor the most part, we cannot hear the voices of ordinary French women—but this study allows us to do so. Based on the evidence of 1,200 cases brought before the consistories—or moral courts—of the Huguenot church of Languedoc between 1561 and 1615, The Voices of Nimes allows us to access ordinary women’s everyday lives: their speech, behaviour, and attitudes relating to love, faith, and marriage, as well as friendship and sex.

Read: The Voices of Nîmes, now new in paperback.

Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts by Nadine AkkermanElizabeth Stuart is one the most misrepresented—and underestimated—figures of the seventeenth century. Labelled a spendthrift more interested in the theatre and her pet monkeys than politics or her children, and long pitied as “The Winter Queen,” the direct ancestor of Elizabeth II was widely misunderstood. Nadine Akkerman’s biography reveals an altogether different woman, painting a vivid picture of a queen forged in the white heat of European conflict.

Read: Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts

The Secret Listener: An Ingenue in Mao’s Court by Yuan-tsung Chen

The Secret Listener: An Ingenue in Mao’s Court by Yuan-tsung ChenA first-hand account of what life was like in the period before the revolution and in Mao’s China, The Secret Listener gives a unique perspective on the era, and Chen’s vantage point provides us with a new perspective on the Maoist regime-one of the most radical political experiments in modern history and a force that genuinely changed the world.

Read: The Secret Listener

Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement, 1968-present by Margaretta JollyThis ground-breaking history of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement shows why and how feminism’s “second wave” mobilized to demand not just equality but social and gender transformation. Oral history testimonies power the work, tracing the arc of a feminist life from 1950s girlhoods to late life activism today. Peppered with personal stories, the book casts new light on feminist critiques of society and on the lives of prominent and grassroots activists.

Read: Sisterhood and After, now new in paperback.

Feature image: Floating book by Jaredd Craig. Public domain via Unsplash .

New York City: the life and times of the Bowery Theater

In the 1830s, New York was a small city. While the island of Manhattan had a prosperous community at its southern end, its northern area contained farms, villages, streams, and woods. Then on the evening of 16 December 1835, a fire broke out near Wall Street. It swept away 674 buildings and though the devastation seemed absolute, citizens quickly rebuilt. They pushed development up the island, so that by the Civil War homes lined the streets near the new Central Park.

Learn about the Great Fire of 1835, and the city that existed before and grew after that blaze in this series of blog posts from Daniel S. Levy, author of Manhattan Phoenix: The Great Fire of 1835 and the Emergence of Modern New York.

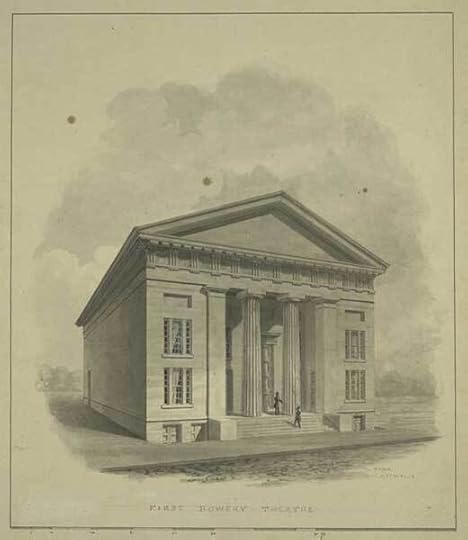

The Bowery TheaterIn the mid-1820s, New York had three theaters: the Park, the Chatham, and the Lafayette. Some citizens felt there should be more and in October 1825, the New York Association started work on a new house. They chose a site between the Bowery and Elizabeth Street just south of Canal Street, and Mayor Philip Hone officiated at the laying of the cornerstone. “This spot which a few years since was surrounded by cultivated fields,” he told the gathered, “where the husbandman was employed in reaping the generous harvest, and cattle grazed for the use of the city, then afar off, has now become the centre of a compact population.”

The theater was just what New York needed. The city’s economy was booming. Just the year before, the Erie Canal opened, helping to establish a transportation network that gave New York access and financial dominance over the nation. Five hundred trade and commercial businesses opened in the city, and development was spreading north of the area around Canal Street, bringing with it clerks for the offices and counting houses, and laborers for the textile factories, breweries, and iron works. All searched for things to do when not at work. The grand Greek Revival theater with the imposing Doric columns by the Connecticut-born architect Ithiel Town opened on 23 October 1826 and offered citizens one such welcomed activity. For the first performance, theater Manager Charles Gilfert staged Thomas Holcroft’s ominously named comedy The Road to Ruin.

Architect Ithiel Town designed the first Bowery Theatre in 1826.

Architect Ithiel Town designed the first Bowery Theatre in 1826.(The Bowery Theatre, Ithiel Town, NYPL)

The house was initially called the New York Theatre, but would soon appropriately be known as the Bowery Theatre. Gilfert catered to the city’s upper class, focused on comedies, and hired British actors. His shows attracted large audiences, but in May 1828 a fire started at a nearby stable, spread down the block, and destroyed the theater. Less than three months later, workers completed Joseph Sera’s new design for the building. Marble steps at the entrance led to a portico fronted by six Doric columns, and the new Bowery possessed the largest stage in America. Frances Trollope, mother of British novelist Anthony Trollope, singled out the Bowery “as pretty a theatre as I ever entered, perfect as to size and proportion, elegantly decorated, and the scenery and machinery equal to any in London.”

Manager Gilfert died in July 1829, and in August 1830 actor Thomas Hamblin took over and started staging shows. While he hired actors like his friend Junius Brutus Booth—the father of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes—Hamblin generally avoided the so-called star system and downplayed his highbrow Shakespearean roots.

The Bowery neighborhood was a workingman and -woman’s place with dance halls, oyster houses, billiard halls, brothels, taverns, gambling dens, bowling alleys, dime museums, boxing matches, and cock fights. Hamblin, who had gotten his start in London playhouses and would run the theater for two decades, wisely appealed to the tastes of his local clientele. He did this by joyfully wrapping himself and the house in the Stars and Stripes and bestowing upon his theater a decidedly democratic American tone. Most of all, Hamblin offered elaborate melodramas and lively spectacles, including horse-and-dog exhibitions and shows. He aggressively advertised the theater, seizing every chance to tout the differences between his house and those of his competitors.

“Hamblin, who had gotten his start in London playhouses and would run the theater for two decades, wisely appealed to the tastes of his local clientele. He did this by joyfully wrapping himself and the house in the Stars and Stripes and bestowing upon his theater a decidedly democratic American tone.”

His plan worked, and audiences embraced the theater and its mix of comedies, tragedies, dramas, French dances, minstrelsy, and circuses. For just 25¢, crowds jammed into the gallery. The lawyer and journalist Matthew Hale Smith commented on the mass assembled there as “News-boys, street-sweepers, rag-pickers, begging girls, collectors of cinders,” along with its journeymen butchers, mechanics, artisans, firemen, folding-girls and seamstresses, milliners’ apprentices and shop-girls, all cheering or booing performers as they littered the floors with peanut shells.

To feed their appetites for spectacle, Hamblin offered larger and more realistic sets as well as bigger casts. Throughout, he featured the work of such playwrights as the European-born Louisa Medina, putting on extravagant performances: an ash-spewing volcano for a staging of The Last Days of Pompeii; 200 soldiers attacking a fortress for The Spectre King, and His Phantom Steed; and even bringing out an elephant for The Elephant of Siam and the Fire-Fiend! According to the author and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, “gorgeous decorations, fantastic tricks, terrific ascensions, and performances full of fire, blood, and thunder” filled the Bowery, not to forget its “vaunting drama, and boastful song.”

A shrewd businessman, Hamblin managed to make it all work, even with continued tragedies. For in a city with a deadly combination of wood, foul chimneys, oil lamps, and chain smokers that was beset by catastrophic fires, the Bowery burnt down for a second time in 1836, just nine months after the Great Fire of 1835 destroyed much of downtown New York. It was rebuilt with a design by architect Calvin Pollard, only to burn once more in February 1838, with a new Pollard-designed structure going up in May 1839. On 25 April 1845 it caught fire for the fourth time. Lawyer George Templeton Strong ran over when he heard word of the blaze. When he arrived he watched, aghast, as “one or two dazzling little streams of fire ran like lightning along the cornices, and in one minute the whole area of the building was a mere furnace, sending high up into the air such a mass of intense raging flame as I never saw before.”

When Thomas Hamblin became owner of the second Bowery Theatre, he turned the house into an entertainment center for both the common man and woman.

When Thomas Hamblin became owner of the second Bowery Theatre, he turned the house into an entertainment center for both the common man and woman.(Bowery, Thomas Hamblin, NYPL)

Forty minutes after the discovery of the fire, the interior of the Bowery collapsed in upon itself. Hamblin did not have insurance for his theater, and as he watched the theater crumble, he bemoaned, “There go the labors of seven years!” Hone wondered whether it was “the voice of fate,” discouraging anyone from building “another temple of the drama on the forbidden ground.”

The former mayor was wrong, however, for even as the men were extinguishing the fire, Hamblin proclaimed, “We are not dead yet boys!” The following day the impresario had crews clearing the site, and he made plans for a new house by architect the John Trimble. It opened on 4 August 1845. Edgar Allan Poe’s Broadway Journal reported that “its general arrangements are excellent,” and “the stage is capacious, and well appointed.” Unlike its predecessors in a city that was constantly burning and being rebuilt, that structure had a long life, and survived until 1929.

Featured image: by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Artist unknown. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-2519 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers