Oxford University Press's Blog, page 82

March 23, 2022

Souls searched for but not found (part two)

This is the second and last part of the series on the origin of the word soul. See part one in the post for 15 March 2022. The perennial interest in the etymology of this word should not surprise us. It is our inability to find a convincing solution that causes astonishment and disappointment. Those who can read German will find a good survey in the paper by Dr. Peter-Arnold Mumm in the 2018 Elke Ronneberger Festschrift. I’ll touch on the questions and comments in my next “gleanings.”

It is sometimes said that before Christianization, the ancestors of the Germanic-speaking people referred to souls only when they spoke about dead or unborn people. Allegedly, souls resided in some distant area, and hypotheses revolved round the place of that otherworldly realm. At first sight, such a hypothesis sounds reasonable. As mentioned a week ago, Bishop Wulfila knew how to translate Greek psychē into Gothic. Later, English- and German-speaking clerics had no trouble with the word for “soul” either. In this situation, a historical linguist has several options. Perhaps saiwol– is a native Germanic word and did refer to an entity existing before our birth and surviving the body after its death. This is thought-provoking guesswork, but references to such a state of affairs did not occur in any extant text.

In Old Scandinavian mythology and legends, life after death (only after death, not before one’s birth) is described in great detail. No immaterial substance is ever mentioned. On the contrary, the dead lead a busy life: fight, feast, compose poetry, sing songs, and occasionally return as malicious ghosts (so-called revenants). Last week, I mentioned a creature called fylgja. This is a human being’s protective spirit and may assume the form of a giantess or an animal, or some other creature. Meeting one’s fylgja (occasionally covered with blood) in real life or in a dream is a sign of imminent death: the protective spirit has deserted the body or perished. Allusions to what we call heredity also occurred, but nothing resembling the immortal soul is ever mentioned. The language of the Goths and other Germanic-speaking tribes has been most successfully searched for remnants of paganism. No hint of soul has turned up.

Sea burial: the god Baldr goes to the Other World.

Sea burial: the god Baldr goes to the Other World.(By W. G. Collingwood via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Among other things, reference to old mythology and literature is important, because the first three letters of saiwol– coincide with the root of the Germanic word for “sea.” Hence the idea that the two words are connected: after one’s death, human souls allegedly depart “overseas.” Sea burials are known very well (one is described in Beowulf, another in the myth of Baldr), but ships took bodies, not “souls” to the Other World. The seemingly obvious connection between soul and the word for “sea” was suggested by the great and almost infallible Jacob Grimm. Though his etymology looks convincing, unfortunately, the etymology of sea also remains a matter of dispute—a familiar quandary.

Two things should be said before we go on with this story. First: religious terms often fall victim to taboo or cannot be pronounced for some other reason. Perhaps saiwol– is a garbled version of some other word. This hypothesis, though supported by multiple evidence, naturally, does not explain anything. The other way out is reference to the substrate, that is, to some native and lost language of the Pre-Indo-European population from which the word for “soul” was borrowed. Here we face another blind alley, like the reference to taboo. The hypothetical source language is unknown and can never be known. Reference to it means: “Etymology is beyond recovery.” In Scandinavia, the speakers of Germanic interacted with Saami speakers and adopted some of their words and religious customs. Shamanism is not a Germanic phenomenon. Yet it exercised some influence on the ancestors on the Norwegians and Swedes. No Saami word for “soul” reached Old Norse. Nor is there a similar Celtic word for “soul” in Anglo-Saxon. To be sure, there is a third variant. The word may be “Nostratic,” that is, almost panhuman. My colleague, a specialist in Turkic and Altaic, alerted me to a word for “breath” in those languages which sounds very much like soul. Yet in Greek, Latin, Celtic, and Balto-Slavic, no match for it has been found.

Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), an illustration to Lermontov’s poem The Demon: “Demon and an angel with Tamara’s soul.”

Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), an illustration to Lermontov’s poem The Demon: “Demon and an angel with Tamara’s soul.”(Via Wikiart.org, public domain)

Some candidates, like Latin saeculum “age; generation, etc.” and Greek dzaō “to live” (the latter allegedly “by inserting l”!), were dropped almost at once, but aiólos “movable, agile, etc.,” a presumable cognate of soul, still has some supporters. Soul emerged from that reconstruction as a quick-moving animal (a mouse or a butterfly) leaving the body after its death. Some folklore supports this idea. (The absence of initial s in aiólos need not bother us. Time and again, we come across that equally agile word-initial consonant called s-mobile.) Yet the origin of the Greek adjective is far from clear, and we are once again reminded of the rule: “Never use an obscure word to explain another obscure one.”

There have been many attempts to present Germanic saiwalō as the compound sai– + wal. The first component resembles the Slavic and Baltic word for “force, strength,” and the second reminds us of the Germanic word for “a dead person” (as in Valkyrie and Valhalla). Part of this etymology is old, but Elmar Seebold (in his editions of Kluge’s etymological dictionary) discusses it at length (note that he misspelled the name of Levitsky or Lewitskij), and therefore, it has become known to many readers.

None of the hypotheses cited above is wrong by definition (naturally: they were offered by outstanding researchers!), but all of them illustrate the game I called last week etymological legerdemain, for which the respectable term is root etymology. Also last week, I mentioned Peter-Arnold Mumm’s paper on the origin of the word soul. He did not only examine all the earlier hypotheses but also proposed his own. He suggested that Germanic saiwalō is a compound, whose first component is related to Latin saevus “fierce, raging” and the second is wala– “dead person” (see it above). His reconstruction depends on the idea that the word for “soul” goes back to the belief in revenants (the dead returning to the human community). I have moderate enthusiasm for this hypothesis: the word “soul” must have meant something less frightening and perhaps less tangible. Also, as far I can remember, the best-known revenants were characters in Icelandic sagas, and all those living dead (or the undead, as they were called) appeared among the living if they were not buried properly.

My soul is dark.

My soul is dark.(“Lord Byron” by Richard Westall via National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

When the shining god Baldr was put on the funeral pyre, his father Othin (or Odin) whispered something to him. Many generations of scholars have tried to guess what he whispered. Of course, we will never know the answer. But from the ethnographers’ work we know what the survivors say to the departed. There are three main variants: “repose in peace,” “protect us while residing in the kingdom of the dead,” and “do not return.” From those rituals I don’t see much support in discovering the etymology of soul.

Since the oldest recorded word for “soul’ occurs in Gothic, it is discussed in the great etymological dictionary of Gothic by Sigmund Feist (1939). Feist argued for the Greek aiōlos as the word’s root and cited some ethnographic data in support of his reconstruction. Winfred P. Lehmann, in his 1985 reworking of Feist, returned to Jacob Grimm’s sea hypothesis, which Mumm dismisses as indefensible. Apparently, we know too little about the beliefs of Wulfila’s ancestors to reach a persuasive solution and have no clue to the origin of the word soul. I am really sorry, and my soul is dark.

Feature image by Giga Khurtsilava on Unsplash

March 21, 2022

Digital dance cultures: from online obscurity to mainstream recognition

I didn’t enter the world of digital dance cultures as a scholar. When I was introduced to TikTok and Dubsmash in October 2018 by my high school students, I first engaged with the platforms as a dancer. Despite having no formal training in dance and believing that any opportunity for me to become a dancer had passed me by, I was suddenly dancing alongside my students on a number of digital platforms that facilitated a growing screendance community. These platforms—namely TikTok, Dubsmash, and Triller—became part of my every day vernacular as the Gen Z dance moves that fill those spaces such as the Woah, the Mop, and the Wave became my choreography. Suddenly, I was a dancer.

In just over three years since TikTok’s entry into the United States and Dubsmash’s re-launch as a dance challenge app, so much has changed. When I joined these apps, posting videos dancing alongside my students, I was one of few adults among millions of teenagers. In fact, even today, Dubsmash is still an almost exclusively Gen Z space. TikTok, bolstered by the pandemic, has become a home for social media users of all ages even if young people continue to dictate the app’s dominant culture. TikTok and Dubsmash’s emergence as critical spaces for digital dance fall into a lineage of screendance platforms that have proliferated since the dawn of the internet. Although screendance has been steadily gaining popularity, the pandemic accelerated this trend.

As with most things during the pandemic, the digital dance world saw a dramatic shift that both changed the culture and solidified many of the trends that had been shifting on the sidelines well before March 2020. Seeing this, dance scholars Harmony Bench and Alexandra Harlig guest-edited a special issue of The Journal of Screendance that responded to the nuanced ways that the pandemic has shifted the ways we engage with dance on digital media. Bench and Harlig note, “Activities once on the sidelines of the dance field are the new normal: teaching technique on Zoom, holding online dance film festivals, DJing house parties on Instagram, streaming archival performance documentation, making TikToks.” Indeed, screens are where we dance now.

As digital dance cultures became more normalized, scholars and the general public began to take notice. This was no more apparent than on 12 March 2021 during the This Is Where We Dance Now: Covid-19 and the New and Next in Dance Onscreen Symposium, produced by Harmony Bench and Alexandra Harlig to coincided with the special journal issue. The online symposium began with a keynote roundtable featuring dance and digital media scholars Crystal Abidin, Kelly Bowker, Colette Eloi, Pamela Krayenbuhl, Chuyun Oh, and myself. Each scholar presented new research about how platforms such as Dubsmash and TikTok have exploded during the pandemic, making what was once something largely associated with teenagers in the US to something more universal. Now, dancing on TikTok, Triller, Dubsmash, and the like is not just an activity filling the hallways of high schools across the US. Rather, digital dance platforms have become an integral part of the mainstream.

As TikTok and Dubsmash have solidified themselves in mainstream US culture, so too have many of the conversations I engage with. Discussions about artist credit, monetization, choreography, activism, and community-building on social media apps, for example, are commonplace now. Casual onlookers now see these apps as serious spaces for artistic production which is the antithesis to how adults diminished young people’s content in the early days of these apps.

Take for instance the story of the Renegade Dance Challenge set to K-Camp’s song “Lottery.” The Renegade Dance entered the mainstream in Fall 2019 after Charli D’Amelio, TikTok’s most-followed creator, posted a video of her performing the dance. The dance took off, becoming what is arguably the most famous dance in TikTok’s short history. But TikTok isn’t where I first encountered Renegade and Charli D’Amelio wasn’t who I associated the dance with. I first learned about the dance from my high school students who had seen it on Dubsmash. The dance wasn’t created by D’Amelio, but was created by Jalaiah Harmon, a Black teen who wasn’t credited for her choreography and was seemingly left behind. After a media firestorm in January and February 2020, Harmon was rightfully credited as the mastermind behind the Renegade Challenge. Her popularity and career both took off, demonstrating the monetization that corresponds with social media virality.

The case of the Renegade signalled a shift in TikTok culture. Soon after, TikTok’s major talents such as D’Amelio and Addison Rae Easterling began giving dance credits in their videos, which modelled a culture of crediting artists. Their followers soon began giving credit, as well. By the time Keara Wilson choreographed one of 2020’s biggest dances, the Savage Challenge set to Megan Thee Stallion’s song of the same name, the entire landscape had changed. Wilson immediately was given credit, received the blue checks on Instagram and TikTok, had articles written about her, and even had the stamp of approval from Megan Thee Stallion. As TikTok grew in import throughout 2020, this became common practice, demonstrating how digital dance spaces became more recognized and respected by mainstream US culture as well as the media who had frequently disregarded TikTok and Dubsmash as silly spaces for teenagers.

Indeed, now looking forward into what the future might hold for screendance, we can see that the pandemic has ushered in many changes that were likely inevitable. Social media dance spaces have been normalized.

Feature image by Solen Feyissa on Unsplash.

March 19, 2022

Zenobia: warrior queen or political tactician?

Popular culture often romanticizes Zenobia of Palmyra as a warrior queen. But the ancient evidence doesn’t support that she fought in battles. Instead, we should remember Zenobia as a skilled political tactician. She became ruler without being dominated by the men of her court. She made bold, smart decisions in the face of harrowing pressure and overwhelming odds. Though ultimately defeated, Zenobia had to play a high-stakes game of survival in a time of immense change and violence. The lives of her and her son depended on it.

Where does Zenobia’s reputation as a warrior queen come from? Surely from how she waged a civil war with the Roman government. Otherwise, we can trace its origins to the infamous Historia Augusta. This ancient work consists of biographies of second and third-century Roman emperors that launch barrages of gossip, rumor, and misleading stereotypes. In its short bios of imperial usurpers, it states that Zenobia took part in her husband’s campaigns against the Persians and often marched with her troops. It never specifies that she fought in battles. But popular culture has made Zenobia into a warrior queen anyway.

When we look to the other major ancient source for Zenobia, the author Zosimus, we encounter a clarification. Zenobia traveled with her army but didn’t fight. When her army engaged Roman forces near Antioch in 272, she awaited the battle’s outcome from the city. No other ancient source disputes this. Even the later Arabic accounts of al-Zabba, a queen based on Zenobia, portray her as a hardened political tactician navigating serious violence. Avenging her murdered father, she lures his killer to his demise through a false marriage proposal. When he arrives at her court, she unveils her intention not to marry by exposing her braided pubic hair and then has him killed. But she doesn’t fight in wars.

For the most part, the Historia Augusta doesn’t even portray Zenobia as a virtuous warrior queen. In its bio of the emperor Aurelian, the man who defeated her, it depicts her as an immoral and ambitious despot. Its account is obviously hostile. It even forges insolent letters allegedly addressed by Zenobia to Aurelian. Otherwise it impugns her for doing exactly what powerful men did: violence and politics. But its portrayal is apt in one key way. Zenobia was politically astute.

Zenobia the skilled politician justifiably dominates modern histories. The ancient sources support how she navigated terrifying, lethal circumstances with aplomb. To understand her as modern historians do, we must understand how she came to power.

How Zenobia rose to powerZenobia was born (c. 240) on the eastern edge of a Roman empire where powerful men kept killing people that they once called friends (or enemies). It was a time of constant civil wars, military overthrows, murdered emperors, and foreign invasions. Zenobia’s husband Odainath rose to power at Syrian Palmyra in the 250s. Skilled at fighting Persians, he worked harmoniously with the imperial government. But during the 260s he ruled the Roman Middle East and adopted royal titles for himself and his eldest son by a prior marriage. When Odainath and Zenobia married, they had a son named Wahballath.

When Odainath and his eldest son were mysteriously murdered in 268, Zenobia emerged as ruler of Palmyra and Roman Syria. Her justification was that she was Wahballath’s guardian, Odainath’s underaged heir. But the ancient sources differ wildly in how they describe Odainath’s death and Zenobia’s seizure of power. We can dismiss the rumor that Zenobia had plotted against Odainath. The gossip-mongering Historia Augusta is responsible for that. More likely is that Odainath’s enemies at Palmyra had gotten to him and that Zenobia had them killed when she seized power. All that is clear is that Odainath’s friends and enemies alike had motive to kill her.

Odainath’s enemies aimed to eliminate his household altogether. This made both Zenobia and Wahballath into targets. But Odainath’s supporters were dangerous too. They could rule through Wahballath, Odainath’s surviving heir. They did not need Zenobia alive for that. Her sheer survival supports that she was not a puppet managed by powerful men. She had no value as one. If she hadn’t seized real power, she probably wouldn’t have lived.

Zenobia’s rise to power testifies to decisive moves that she made under terrifying circumstances. Sources written in Latin, Greek, rabbinic Hebrew, and Arabic agree that she wielded supreme authority, not her generals and advisors. But Zenobia came to power in a den of vipers where power-mongering and violence never ceased. Some notables at Palmyra were biding their time to betray her. Meanwhile the Roman government denied that she could transfer Odainath’s titles and authority to Wahballath. Classifying her as a usurper, it schemed to get rid of her. Zenobia faced overwhelming odds her entire reign.

Zenobia confronted these odds remarkably. The sources agree that she managed her realm admirably for four years. Only in 272 did the emperor Aurelian invade Roman Syria and remove her from power. Until then, she met and corresponded with orators, historians, and itinerant preachers. She imitated prior women rulers and pursued the regal ideals of philosophers. She waged an impressive, if failed, civil war with the imperial government. But two factors taint her record. One is the possibility that her offensive campaigns in Arabia, Egypt, and Anatolia were a strategic blunder. The other is that she betrayed her advisors, including the notable philosopher Longinus. Neither criticism is entirely fair.

“Zenobia survived by exploiting how men stereotyped women as weak and immoral. If she had been a man, her conduct would attract less scrutiny.”

It can be attractive to classify Zenobia’s offensive campaigns in 270-271 as a needless escalation, one that made reconciliation with the Roman government impossible. In theory, she could have just governed Syria, especially in the empire’s current instability. Her campaigns have even attracted to her what is often a backhanded compliment for women: “ambitious.” But Zenobia surely realized that the Roman government would not tolerate her rule and that war was inevitable. She had to move first to get the upper hand and amplify her resources. Initial success would make victory or renegotiation more likely. If she waited, defeat was much more certain. Even in its contemporary state, the Roman government was more powerful than hers.

Ancient sources also claim that Zenobia, once defeated, betrayed Longinus and other advisors to Aurelian. She posed as a feeble woman who had acted on their compelling advice. Some (like Edward Gibbon) have ascribed Zenobia’s actions to womanly weakness. But we shouldn’t hold her to a double standard when assessing her aspirations and actions. We don’t need to praise what Zenobia did. But we should accept that she was behaving like contemporary men who played political hardball. Sometimes survival involved betrayal. Zenobia survived by exploiting how men stereotyped women as weak and immoral. If she had been a man, her conduct would attract less scrutiny.

Ultimately, Zenobia’s political tactics enabled her and her son to survive. Despite some traditions that she starved herself to death, the best ancient testimony supports that Aurelian had her march in his triumph in Rome while weighed down by gold and jewels. But Aurelian decided that she and her household were worth sparing. Zenobia spent the rest of her life on an estate at Tivoli. It may look like an inglorious end to her story. But in truth, it’s a testament to her political skill.

Feature image: Herbert Gustave Schmalz, via Wikimedia Commons

March 18, 2022

New York City: the grid

In the 1830s, New York was a small city. While the island of Manhattan had a prosperous community at its southern end, its northern area contained farms, villages, streams, and woods. Then on the evening of 16 December 1835, a fire broke out near Wall Street. It swept away 674 buildings and though the devastation seemed absolute, citizens quickly rebuilt. They pushed development up the island, so that by the Civil War homes lined the streets near the new Central Park.

Learn about the Great Fire of 1835, and the city that existed before and grew after that blaze in this series of blog posts from Daniel S. Levy, author of Manhattan Phoenix: The Great Fire of 1835 and the Emergence of Modern New York.

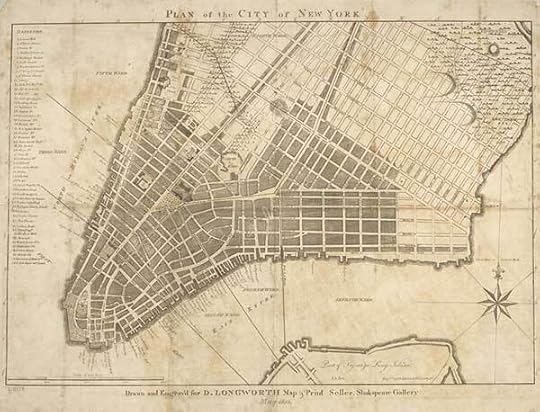

The gridThere had been attempts to lay out streets in New York going back to its founding. It was a process that would go on for the next few centuries, and would only accelerate in the decades before and after the Great Fire of 1835. In 1625, right after the Dutch settled what was then known as New Amsterdam, the engineer and surveyor Cryn Fredericksz devised a rough grid for the town’s roads. The Dutch were attracted to the southern tip of the island for its inlets and streams, and there created waterways similar to those found in Holland. Present-day Broad Street, for instance, was once a small stream that ran through a marshy area, which they transformed to Heere Gracht, Gentleman Canal.

By the late 18th century, the canals were covered and a number of streets in lower Manhattan were paved. Even so, traveling around the island could be rough going since much of it was covered by rocky outcroppings. At the start of the 19th century, most assumed that there would never be much growth to the north. By then, a field in what was then the northern part of the city—where City Hall and its park now stands—had become a popular spot for holding public rallies. It became known simply as “The Park.” When City Hall was built the early 1800s at the Park’s northern end, only the southern, western, and eastern facades were sheathed with white marble; the northern side featured less expensive brownstone, since it was assumed that no one would go around to the back.

At this point, the island’s original topography was being transformed. The Collect Pond, which stood to the north of City Hall, was gone. Streams like the Minetta, which flowed through what is now Washington Square Park, were routed through undergrounds channels. Sun Fish Pond in the lower 30s, where New Yorkers once fished for eels and sunfish and in the winter ice-skated, would soon be drained and filled.

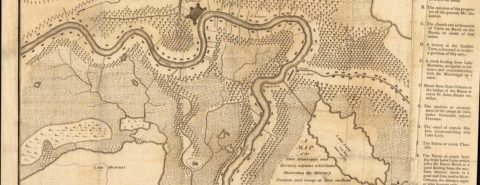

In the early 1800s, development of New York reached up to the area above Foley Square, and the Collect Pond stood where cars now flow.

In the early 1800s, development of New York reached up to the area above Foley Square, and the Collect Pond stood where cars now flow.(Grid, New York 1803, NYPL)

In order to ensure an orderly development for the island, the state legislature on 3 April 1807 appointed Gouverneur Morris, Simeon De Witt, and John Rutherfurd to decide the street pattern above Houston Street. The commissioners were granted the authority “to lay out streets, roads and public squares of such width, extent and direction as to them shall seem most conducive to public good.” To map the land, they hired the surveyor John Randel Jr. Randel started trekking across the island, making his way around the ponds, through meadows and marshes and over outcroppings, and staking the land.

Some did not care for his measuring and mapping their property. Historian Martha Lamb wrote how on one occasion, he and his crew were drawing the line of an avenue directly through the kitchen of “an estimable old woman, who had sold vegetables for a living upwards of twenty years.” As they worked, Randel and his men “were pelted with cabbages and artichokes until they were compelled to retreat.”

Undaunted, Randel finished his survey in 1810. His plan for the city included the suggestion that the varied topography be taken into consideration for a number of streets. Morris, De Witt, and Rutherfurd, though, ignored such concessions. Instead of creating a civic design with ovals and diagonal layouts—like that laid out by Pierre Charles L’Enfant in Washington, D.C.—their Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 set up a scheme that focused entirely on growth. To do that, they imposed upon the land a rigid grid of streets and avenues. As the commissioners noted, “a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided, and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in.”

All these perpendicular roads ran regardless of the location of streams, hills, and outcroppings. This regular system of roads included a dozen 100-foot-wide, north–south avenues. The streets began at Houston Street, with 155 east–west roadways set 200 feet apart. Since the city relied so heavily on the rivers for trade, the traffic naturally flowed toward the water. Broadway was the only existing road allowed to continue its meandering path. The idea that the whole island would be developed seemed chimerical at the time, and the commissioners saw no reason to plan above 155th Street. As they commented, “It may be a subject of merriment, that the Commissioners have provided space for a greater population than is collected at any spot on this side of China.”

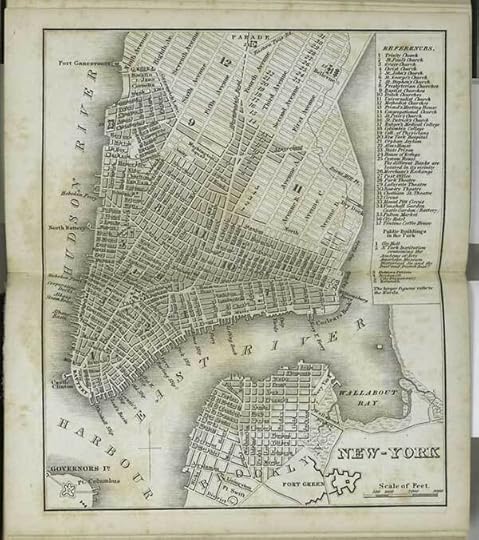

A year after the Great Fire construction was underway around Washington Square Park and builders were eyeing land further to the north.

A year after the Great Fire construction was underway around Washington Square Park and builders were eyeing land further to the north.(Grid, New York 1836, NYPL)

Hills were leveled and streams were filled. Since planned streets ran through private property, the city had to take possession of the land, a process that proved to be long and tortuous. Not surprisingly, many landowners objected to the grid. Author Clement Clarke Moore, for one, did not like the city taxing him for streets cutting through his Chelsea estate. In 1818, the author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” which begins with the line, “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” published A Plain Statement, Addressed to the Proprietors of Real Estate in the City and County of New York. In it he derided how “The great principle which appears to govern these plans is, to reduce the surface of the earth as nearly as possible to a dead level.”

But there was good money to be made as the populated parts of the city moved northwards. Prominent families started selling off their estates. The Stuyvesants developed their property around current-day Tompkins Square in the East Village. Swamps were drained, and in the mid-1830s the city created a small park, whose presence only further caused the area to boom. Soon even Moore got into the real estate business.

Many others were bitten by the real estate bug. Bowery Theatre manager Thomas Hamblin bought and sold some 20 lots. James Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s son, recalled how “From 1825, when I purchased eighty lots of ground, I devoted my attention to making money by dealing in real estate in New York and Brooklyn, and building houses, with very marked success.” Development was made easier by Randel’s grid, which standardized growth. So as its population soared, immigrants streamed in, developers subdivided the land, and buildings along with thousands of businesses and row houses rose, then were razed or burned down, they were quickly replaced by newer, grander ones.

As the city continued its northward expansion with streets stretching out, everything was being regimented to the grid. Walt Whitman would note in 1849 that “streets cutting each other at right angles, are certainly the last things in the world consistent with beauty of situation.” And while the plan allowed for structured expansion and—as a side benefit—made responding to fires easier, the grid sealed the city’s position as the ultimate real estate boomtown.

Read the next blog posts in the series:New York City: The Great Fire of 1835New York City: the life and times of the Bowery TheaterNew York City: the streams and waterways of ManhattanFeature image by William Bridges. Surveyed by John Randel Jr. This map is available from the United States Library of Congress Map Division under the digital ID g3804n.ct000812.

March 17, 2022

History repeats—yellow fever and COVID-19

See if this sounds familiar: misinformation, disinformation, and incomplete information are applied to an epidemic, its causes and treatments. A deadly disease emerges from an unknown, foreign source. Some people are sickened, others remain untouched. How it is spread is uncertain. Preventative tactics cause economic harm. Treatments include some that approach the bizarre.

Sure. All these have been in headlines daily for the past two years about COVID-19, in print, television, radio, or online.

Except I am not referring to COVID-19 of the past two years, but to 1878, and the yellow fever epidemic that decimated a wide swath of the southern reach of the Mississippi River.

History repeats.

It is 1878. An outbreak begins in New Orleans, as it has most years, to one degree or another. Where did it come from? Locals did not know, but for years, many in the South called the sickness, “Strangers Disease,” because it was associated with immigrants seeking work and allowed assigning blame. Or “Yellow Jack,” not due to the jaundiced skin of the ill, but the yellow flag ships flew to denote sickness aboard. Another name, “Black Jack,” so named because of the black vomit of some victims before death.

It was not a new disease, but it was a nasty, deadly disease. In New Orleans alone, 20 years earlier, 13,000 were left dead in just three summers. Sickened people mad with fever ran into the streets before dropping dead. Thousands of others, for unknown reasons, felt no effects. In addition to strangers, the fever was blamed on bad air, filth, and the ill-defined “miasma”—filth and “miasma” were where the poor and the immigrants were concentrated, often low, swampy areas, lacking sanitation. To clean the air, cannons were fired and tar was burned. Because of misinformation, those acts achieved nothing. Well, nothing positive, anyway. The disease inspired fear, as it had when death tolls mounted in earlier years. People fled, as medical refugees. Fleeing New Orleans generally meant on the River, sailing north on river boats.

Every landing at ports along the River spread the fever, but also spread ruin as small-town economies dried up—local populace either fled or dead. Memphis was the worst. The city, warned of the epidemic heading upriver, tried to protect itself by preventing ship landings, but an infected deckhand slipped ashore outside the city and found his way into town. Ground zero.

Misinformation flowed. The fever was caused by victims’ soiled clothes or bedding, all of which was burned in the streets. No good. To keep out the bad air, windows were shuttered and stoves were kept burning—in the Memphis summer! Sulfur was burned in houses but, because the fumes were toxic, windows were opened—what about the “bad air” outdoors? The dead were buried quickly, because everyone knew corpses spread disease. The fever came on shipped goods, such as bales of cotton. A ban on shipping cotton harmed growers and shippers; the fever was unharmed. More medical refugees. An estimated 25,000 fled Memphis, many of whom unknowingly took the sickness with them. Lacking ability to flee, 20,000 remained. Of those who stayed, 17,000 were sickened and 5,000 died. The sick were shunned and abandoned. Family members, even sick children, left behind by others fleeing. The fabric of society was unravelling. The Memphis police force had 48 members, 48 before yellow fever, anyway. All but five were sickened; ten died. Doctors and nurses—both locals and those Good Samaritans who came from everywhere to help—faced the same fate as the policeman or the average citizen. The fever did not discriminate; social standing or being a Good Samaritan mattered not; death continued.

At least the lack of information was due to misinformation, not disinformation. No one during the 1878 Memphis epidemic benefited by bad advice, not even gravediggers, their ranks depleted, too. There was no spin on the information—misinformation was due to missing knowledge, not an effort to mislead.

Science of the day did not have the knowledge at the time. More than 20 years would pass before the cause of yellow fever and its spread would be understood, explained and accepted.

Not strangers. A mosquito. Not unburied corpses. A mosquito. Not bad air, not miasma. That’s why burning clothes didn’t help, nor did a ban on shipping. Burning tar or sulfur and firing cannons only hurt human lungs and ears, not mosquitoes. The mosquito, Aedes aegypti, which affected human history for millennia, was a suspect, but the idea was soundly rejected in 1881—rejected by misinformation. Not until 1900 was that insect proven to cause yellow fever.

Information is power.

In 1878, misinformation about yellow fever occurred because so little was known. Without information, people were left powerless, and many people died.

Think now. Of the COVID-19 virus. So much more is known. Disinformation about the virus occurs, and not because little is known. Far from it. Much is known. Disinformation provides information that misleads. Disinformation occurs because information is power. Again, people are left powerless; again, many people die.

History repeats.

Featured image by Norman B. Leventhal Map Center via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 2.0.

Behind the cover: Human-Centered AI

Images have long shaped thinking. Graphic designers, especially for advertising companies, are well-versed in how to convey the luxury of new cars, the strength of professional sports teams, or the attraction of tourist destinations. These images create interest, set expectations, and shape behavior.

The metaphor of thinking machines has a long history, which was reinforced by images, which adorned books, magazines, corporate advertisements, and websites. A key image, showing a human finger reaching out to touch a robot finger, is based on Michelangelo’s painting, The Creation of Adam, showing God’s finger reaching out to Adam’s finger. That image, created during 1508-1512 in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, inspired many artists for 500 years, leading to the familiar AI and robotic portrayal of a human finger touching a robot finger, and then variations, such as human and robot handshakes.

A familiar portrayal of AI and robotic technology based on Michelangelo’s painting, The Creation of Adam.

A familiar portrayal of AI and robotic technology based on Michelangelo’s painting, The Creation of Adam.(Via Max Pixel, CC0 Public Domain)

Other robotic images depict humanoid robots with electronic wiring and human brains with chip circuitry. These compelling images support the misguided notion that future robots will be made in the form of humans, suggesting other human-like capabilities such as two-legged mobility, five-fingered dexterity, and dominance of voice interaction. These images also suggest that computers could or should be emotional, have beliefs, and possibly be conscious.

I’ve long felt that these images were misleading, thereby slowing research on technologies that ensured human control, which would be designed to amplify, augment, empower, and enhance human performance. My expectation for the future is that computers will become supertools, such as the AI-infused cellphone camera or navigation apps, or active appliances like Google’s Nest for home control and iRobot’s Roomba for house cleaning. These innovations give people super-powers by ensuring human control, while increasing the level of automation. They boost human capabilities.

Finding alternative images that overcome the strongly entrenched robotic presence proved to be a serious challenge. Sociologist Lewis Mumford’s writings helped me to understand that the “obstacle of animism”, the belief that new technologies would be modeled on human forms, had to be overcome in images as well as in metaphors, terminology, guidelines, and prototypes. My metaphors describe AI-infused supertools, tele-bots, active appliances, control centers, but I struggled to find visual representations.

In working on the cover for my book Human-Centered AI, I developed these guidelines for what I wanted:

images of people: individuals and teams working together to do something meaningful, supported by technologydiverse people: men/women, old/young, white/black/brown, abled/disabledenough human features such as eyes, nose, mouth, to appear expressive: happy/sad, playing/working (silhouettes can work)technology connecting them, empowering them: people using tools, standing on technology platforms, typing on keyboards, looking at screens, tapping on mobile devices, networked togethernatural world representations such as plants, birds, animals, butterflies, clouds, sunshine, rainbows.The challenge of finding other ways to present future technologies is still a wide open one. Fresh strategies are needed to make iconic images, compact logos, appealing animations, and compelling Hollywood films that provide helpful visions of what future technologies should do to empower people. The film Minority Report showed a wall-sized user interface that gave Tom Cruise ample room for physical sweeps and swipes across the screen. Howard Rheingold called computers “tools for thinking” in his book Mind Amplifier. Steve Jobs triggered interest when he called computers a “bicycle for the mind,” which led to appealing images in Apple ads.

“The challenge of finding other ways to present future technologies is still a wide open one.”

Bolder visions of amplified humans are superheroes with superpowers such as Marvel Comics’ Iron Man, in which wealthy inventor Tony Stark creates a magical body-covering suit that enables him to fly, fight, and save the world from evil forces. The move from comic books to action films gave special effects animators ample opportunities to explore visual representations of superpowers. Similarly, other comic book superheroes, from Superman to Wonder Woman, with superpowers showed how technology could enhance human performance. Wonder Woman, from DC Comics, was a founding member for the Justice League, which presumably was the inspiration for the Joy Buolamwini’s Algorithmic Justice League that fights against biased machine learning algorithms. Their story was told in the 2016 Netflix documentary Coded Bias.

Additionally, a team of seven authors wrote a serious technical paper titled “Superpowers as Inspiration for Visualization,” which offers delightful mind-expanding ideas. They used the Superpower Wiki as a guide to thousands of enhanced human abilities from fiction to shape their ideas of how to build superpowers into new technologies.

Due to this, my guidelines may be useful to others who seek to show how technology amplifies, augments, enhances, and empowers people, but I hope creative artists will make bold images that open our minds to new possibilities.

March 16, 2022

Soul searching, or the inscrutable word “soul” (part one)

If we expect someone to save our souls, this person won’t be an etymologist, because no language historian knows the origin of the word soul, and without a convincing etymology, how can anyone save the intangible substance it denotes? Yet nothing prevents us from looking at the main attempts to decipher the mysterious word.

Except for the Scandinavian runic inscriptions, all our texts in the oldest Germanic languages were written by Christian authors, and in those texts, the word soul meant what it does to us, but the idea of some perhaps immaterial, volatile, and immortal part of a human being predates the conversion of Europe by millennia. The Old English for soul was sāwol, a form very close to Gothic saiwola. We will see that in early Germanic, the form must have sounded approximately as it did in Gothic.

The Gothic version of the New Testament was written in the fourth century, that is, about 500 years before the oldest texts (not counting the runes) in any other Germanic language. Bishop Wulfila translated the Bible from Greek, and the Greek word he dealt with was psykhē (stress on the second syllable). The Gothic gloss on psychē occurred only once in the extant pages of the Bible (M 6:26; I’ll quote the Authorized Version: “For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?”), so that we cannot know how broad the semantic scope of the Gothic word was. Yet even though the Gothic noun turns up only once, we have the support of the adjective sama–saiwals “of the same mind,” a compound, somewhat reminiscent of English soul mate. It follows that saiwola also referred to one’s disposition.

King Alfred was not only a great king but also a great translator from Medieval Latin.

King Alfred was not only a great king but also a great translator from Medieval Latin.(King Alfred, Temple of British Worthies, Stowe. Philip Halling

via Geograph, cc-by-sa/2.0.)

Wulfila was a great master of variation and often used synonyms for rendering the same Greek nouns, adjectives, and verbs. This is not surprising. While translating a foreign text, we often do the same. Let us imagine that our original has beginnen (German) or commencer (French). We may, for the reasons perhaps not always clear even to ourselves, write begin in one sentence, start in another, and commence or initiate in a third one. Most translators probably do and have always done so. At least King Alfred, the greatest ruler of early Britain, resorted to this type of variation while translating from Latin into Old English.

Classical Greek had at least one synonym for psykhē, namely þȳmós “soul; breath, etc.” Breath is especially typical: it leaves the body and disappears. The Greeks sometimes represented the soul in the shape of a butterfly, but it was only one of several images for that elusive concept. In Homer, the souls of the dead were called eidola, and they resembled evanescent ghosts. On the other hand, Homer depicted souls as the doubles of the dead. The idea of some matter called soul goes back to the belief that the human body contains a substance capable of escaping and leading an existence of its own. This idea finds support in dreams (we seem to be doing all kinds of things while our body remains in its place) and in the belief that death is not the absolute end of our existence.

In Old Icelandic literature, we constantly read of a person’s double, who (which?) lives in a human body and protects it. Meeting this guardian presages death: once the hero of the tale meets the giantess who is his hamingja (such is the relevant Icelandic word; a feminine noun), it means that his protective spirit has left him and he is doomed, or to use the Scottish word, “fey.” As noted, the origin of soul has not been discovered, and below, I’ll be able only to list the ingenious hypotheses regarding its etymology, but the direction of the search is obvious: we should look for a word that in some way reflects the idea of the indestructible double of a human being, of one’s materialized essence freed from the body in sleep or after death.

A butterfly being released: a soul heading for Paradise?

A butterfly being released: a soul heading for Paradise?Greek psykhē, immediately recognizable from English psyche, is not too helpful for understanding what the Goths or the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons understood by this word, because in the history of Ancient Greece, the view of the soul did not remain unchanged. But from Greece we have numerous vases and funerary stelas (or steles) with the images of the butterfly, presumably the soul of the departed, while from the Germanic Middle Ages only the word naming a theological concept confronts us. The ancient idea underlying saiwola remains and will probably forever remain hidden. Obviously, Wulfila never bothered about the etymology of saiwala, the word he used. But for some reason, it satisfied him and the Christian scholars elsewhere who later sought an equivalent for Latin anima.

Canova: Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.

Canova: Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss.(Photo by Kimberly Vardeman, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

We should conclude that Wulfila, who knew the Greek noun and (as a matter of course) also Latin anima, had a clear idea of their equivalent in his language. Why did he? What did the saiwala “do” in the Gothic community? Did it fly, torment people in their sleep, fly or walk away from those who died? Did it resemble a bird (this suggestion has some support in the art of the Ancient Greeks) or an animal? When a shaman is in a trance, his soul takes on the shape of an animal or a bird and fights a similar beast or bird, the emanation of another shaman. What could the saiwala’s material substance be? Saiwala was certainly not a mere philosophical concept! Germanic clerics worked in close contact and occasionally met to discuss the words they should use in their translation from Latin and Greek. German and Dutch do have a cognate of soul (Modern German Seele, Dutch ziel), but the Old Norse noun was borrowed from Old English. It follows that the Scandinavians preferred not to use any of the words like hamingja and felt satisfied with a borrowing that meant nothing to them but enjoyed prestige in the rest of the Germanic-speaking world.

The question then is: “What could be the original meaning of Germanic saiwalō? (The reconstructed form with a final long vowel predated Gothic saiwala.) This will be the subject matter of the next post, but one consideration is worthy of note even here. There is no certainty that in this word, saiw– is the root and the rest some sort of obscure suffix. The Germanic noun can well be a compound, that is, sai-wala or saiw-ala. Be that as it may, the entity we expect to reconstruct should be something tangible and observable: a bird, a butterfly, a monster, a puff of breath—anything. We are not interested in etymological legerdemain for its own sake. Most probably, Wulfila had a physical object in mind when he used the word saiwala. Today, when asked to define soul, we are in trouble, but to Wulfila saiwala must have been as material as hamingja was to the Scandinavians. Mythological thinking did not indulge in abstractions. Such is my assumption, but of course there is no certainty that this assumption is correct. Soul searching is a complex and sometimes fruitless procedure.

March 15, 2022

Shared governance—not shareholder governance

The intellectual basis for shareholder control of firms is that what is good for shareholders is good for everyone. In turn that is rationalized by the claim that only shareholders bear risks that are not compensated by contracts. This idea should be viewed as comic relief. Nevertheless, it has been the canonical view of academics, professionals, and law-makers for more than half a century—only challenged by occasional tweaks of company law that square the circle by denying any fundamental conflict between shareholders and other parties. Increasingly, however, this view has become untenable in a world where wage growth has not kept up with productivity, where state interventions, especially since 2008, have protected shareholders from losses, and where company scandals, often environmentally related, have proliferated.

There are three main ways in which private corporations can be encouraged to do good and avoid bad: investor pressure, state action, and stakeholder control.

Investor pressureOf these, the first—investors seeking compliance with set goals—tends to get the best press. Issues of environmental sustainability, board diversity, executive pay, and supply chain ethics are now actively monitored by specialized information providers. Hundreds of variables of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) significance are combined into indices and metrics to judge the conformance of companies to ethical codes. A whole industry has grown up around this theme to quantify and sift information and it has met with acceptance, if not approval, from large global companies who, by and large, see it as a safer form of control than other options and a reasonable complement to established board governance. ESG thus follows an acceptable narrative as a way to correct market excesses such as an undue regard for short term interests, a disregard for spillover (externality) effects on society, excessive risk-taking, or an undermining of the moral foundations of markets. A key moment of approval for ESG came in a 2019 statement by the US Business Roundtable of senior CEOs who effectively endorsed stakeholder views. Nevertheless, not everyone is convinced. Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz was not the only critic to warn that it was a rhetorical and disingenuous device to avoid a backlash against continuing anti-social and tax-avoiding behaviour of many of the signatory companies.

The Financial Times columnist Robert Armstrong, a strong pro-capitalist commentator, has explained nine reasons why ESG is a false hope that simply acts as a displacement activity—one that shuffles shares between investors without materially affecting behaviour. This has been underscored by whistle blower Tariq Fancy, previously chief investment officer for sustainability at Blackrock. He claims that a market-based solution of financial trades in sustainability has been fraudulently pushed by senior executives who are well aware that it cannot solve major issues such as climate change.

State regulationThe second approach—regulation—is preferred by ESG sceptics such as Stiglitz. And certainly, it is hard to see any progress in such issues without the enforcement of minimal standards. But if the state is a social field of power, it is an uncertain ally of the less powerful. The regulatory approach invites some caution due to increasingly dense and strong state-to-company links exemplified by national champions, light-touch rules with the free choice of regulator, and revolving door appointments that have compromised regulatory agencies such as the US Environmental Protection Agency. In addition, there has been a reduction in state competence and capacity for effective regulation in areas such as the information sector or the gig economy, even as increased complexity warrants improvements.

Stakeholder corporate governanceThese pessimistic conclusions in relation to either regulation and ESG do not mean that these cannot be part of a solution. But the large question-marks that hang over them open the door to the third candidate for checking the power of corporations: stakeholder corporate governance. There is reason to believe that this is the most important channel to moderate company decisions. It is an institutional arrangement that is based in the company itself and thus provides the quantity and quality of information that is needed to check abuses inherent in the current one-sided power structure. Stakeholder governance transmits knowledge from below that is not available to financial analysts and markets, nor even to regulators. In recent years, accountants, auditors, board members, financiers, and regulators have increasingly claimed ignorance of fraud and social damage that they were supposed to prevent. Stakeholder governance provides a check on both directors’ and shareholders’ actions in a way that traditional company boards—no matter how full of “independent” directors—cannot match.

In recent years, we have seen an astonishing line-up of broad support for stakeholder ideas—only to stall in the face of difficulties in implementing them. In the UK, various interests, including the Royal Society of the Arts, the British Academy, the Trades Union Congress (TUC), the Institute for Public Policy Research, Bank of England, and even the Institute of Directors, have indicated that they are open to stakeholder initiatives. Nevertheless, nothing ever seems to happen and initiatives fizzle out. Why is that such an enduring pattern?

The Conservative Party under Theresa May backed the idea of placing workers on the boards of companies in 2016. This was later diluted to the idea of an advisory committee and eventually dropped entirely. The Labour Party too has flirted with stakeholding from the early days of Tony Blair; other proposals such as workers on boards or worker-owned investment funds have now been sidelined. These ideas, however well intentioned, were lamentably unthought through. Workers on boards means little unless organized within a context where there a level of trust between labour and management. That requires an institutional architecture to be constructed, something that was totally neglected in the proposals by both political parties. By contrast, the TUC recognizes the level of transformation of industrial relations that is needed for such reforms to be effective but lacks the buy-in and commitment from others for radical change.

Reforming corporate governanceThere are in fact multiple competing plans for corporate governance reform and this may be why radical change is so difficult to argue for. One approach is to reform the system of shareholder voting so as to give greater weight to long-term strategic interests that are at risk under dispersed ownership. This however would at best only address one of the drawbacks of shareholder governance. More promising candidates include a focus on the legal framework with the aim of broadening the duties of directors and changing the complementary shareholder centric “soft law” in the form of governance codes and takeover codes. Other proposals have also been made for parallel models—rather than wholesale replacement—of shareholder governance by encouraging new forms of incorporation, such as foundation companies or not-for-profit business forms. Yet it is unclear how these institutions could form a large weight in the economy; some Nordic countries where that is the case have particular historical trajectories that enabled it.

The country specificity of solutions is also the main objection to the importing of German-style co-determination to liberal market economies such as the UK. There is now much good evidence that such a system works well in the context of complementary institutions. So, the prize would be considerable if some way could be found to approximate these institutions by incremental steps so as to lay the groundwork for countervailing power in the boardroom, with interests such as employees having serious weight through direct representation on the main board or a new supervisory board. One way of bringing this about might be to internalize the strategic training role within the company—not necessarily in terms of provision but of procurement and design. In such a framework, stakeholders and particularly workers would have an incentive to democratize decision-making in the workplace in a collaborative exercise with management—something similar to the works councils found in continental Europe. Other suggestions are to arrange the restructuring of companies in a collaborative way between labour and management by norms of information sharing and for the preparation of alternative competing plans for discussion and resolution. For sure nothing will happen until a critical weight of opinion opts for radical change. The dogs bark but the caravan remains. Corporate governance, clearly, is still in contention.

March 14, 2022

Managing the power of music to foster safety and avoid harm

Pulitzer Prize recipient and American playwright Lynn Nottage shared in a recent interview, “What music can do is get to the emotion with incredible economy and efficiency.” This capacity that music holds to reach in and connect to the wide range of emotions we experience as human beings can be a wonderful asset as it accesses those feelings we want to revisit and are ready to express. This becomes challenging and potentially harmful when it relates to unexpressed or unresolved emotions and experiences. The potency of music can reach within us and connect to emotions and experiences we are not prepared or ready to feel, experience, or revisit.

The concept of trauma-informed care has evolved over the past three decades and is being applied in a wide range of community and clinical-based settings with students and clients of all ages. Trauma-informed care encourages teachers, healthcare professionals, and care providers to recognize and understand the role that trauma and the lingering effects of traumatic stress can play in the lives of the individuals they serve. Next, providers discover the steps and practices to implement to avoid adding new stress, triggering, or inadvertently re-traumatizing the client.

While music holds a potency to connect to our emotions, it has many characteristics that can be utilized to address different needs. As a result, it is important to explore with the client healthy uses of music versus unhealthy uses of music. This can help to ensure that the client can make informed decisions about using music in ways that support their health and well-being. This can also help them recognize when they may be using music in unhealthy ways, such as listening to a song repeatedly that keeps them fixated or stuck in a negative mood state.

It is important to determine the client’s needs, how they prefer and feel comfortable engaging with music, their desire to explore new ways of engaging with music, and when they want or need to use music in their day-to-day life. While we can listen, sing, play, improvise, and compose music, in a trauma-informed care approach, it is important to begin where a client feels safe. The client may be ready to move into other types of music experiences in time, but it is important to determine a starting place with music that does not cause the client to experience additional stress.

Listening to musicListening to music can help to manage stress and foster relaxation. These capacities innate in music are well suited to address the principles of trauma-informed care. Designing and structuring relaxation experiences with slow tempo music (60-80 beats per minute) that is preferred by the client, can help to slow down the heart and breathing rates and foster an overall relaxation response. Listening to music at these slower tempos allows the rhythms of the body to slow down, fostering a relaxation response. This in turn can help a client feel a greater sense of safety. Additionally, working with the client to identify their preferred music gives them the power of choice and helps them to feel more empowered in making decisions for their well-being.

Developing playlistsDeveloping playlists of music that are calming, supportive, or empowering can give the client tools to use and easily access in their everyday life. Working collaboratively with the client in this process can foster a sense of mutuality that helps them in building their knowledge and skills to create their playlists in time. Through this process, they discover what helps them to feel safe, develop a sense of trust as co-creators in the process, and feel empowered as they communicate their preferences, and make choices and decisions about the music. They can create playlists to address a wide array of needs including shifting or elevating their mood, fostering relaxation, providing distraction, or supporting sleep. Wellness Well Played: The Power of a Playlist by music therapist Jennifer Buchanan is a book dedicated to exploring the use of playlists and provides suggestions for creating them to support various aspects of health and wellbeing.

Creating musicSinging and playing music may be a familiar experience for some clients and very unfamiliar for others. If a client is interested and ready to create music it is important to understand where they feel ready to begin. Do they need something simple? Such as chanting words on a mantra that fosters a sense of safety. Is there a favorite song they want to sing or play that fosters their confidence and helps them feel strong and empowered? Will they feel grounded playing a slow heartbeat rhythm to a relaxing piece of music? The level of simplicity and complexity of the experience can be tailored to meet the needs of the client. Additionally, this type of active engagement with music can be adapted over time as the client is ready to explore engaging in the music in new or more complex ways.

ComposingComposing a song or music may feel like a daunting task to some clients. Maybe they have a favorite song or a song that inspires or motivates them? The song can be personalized by rewriting segments of or all lyrics, so the song expresses or communicates the client’s feelings or experiences. Maybe the client is interested in writing a mantra and the melody to chant it to? Supporting the client in using their voice to express what they want to say and/or hear can help them to discover how they can create their sense of safety and can discover a sense of empowerment as they sing and hear their own words in a song.

ImprovisingImprovising music may feel overwhelming to some clients as they may experience it as a lack of structure, which may leave them feeling vulnerable and exposed. If a client is interested and ready to explore improvisation, it will be important to determine the level of structure and support they need to feel safe and to be able to trust their co-creator(s) in the experience. The level of structure can be altered and changed when the client is ready, but it is important to explore this with the client so they are not caught off guard and feel unsafe in the music experience.

Music holds a great capacity to connect to our emotions and experiences, positive, challenging, and negative experiences. Integrating a trauma-informed care approach when using music and in music therapy helps to ensure that clients feel safe, secure, and are not triggered or inadvertently harmed. A vital element of trauma-informed practice is understanding how to use music and its elements to safely address the client’s needs. Clients may not always have an awareness that they have experienced trauma, so infusing a trauma-informed care approach in everyday practice is an important safety measure.

Featured image by Vinzent Weinbeer on Pixabay

March 13, 2022

The Piano meets The Power of the Dog

In Jane Campion’s 1993 film The Piano, a crated Broadwood grand sits abandoned on a remote and desolate beach, then later it gets carried through the muddy overgrown New Zealand jungle to a settler’s home. In Campion’s new film, The Power of the Dog, a Mason & Hamlin grand is carried by ranchers into the Burbank house in remote Montana so that Mrs Burbank can play it when the Governor comes for dinner. “No, it’s too good for me,” Rose modestly protests when the fancy instrument arrives. “I’m just very average, I only know tunes.”

In both films the grand piano serves as more than the emblematic instrument of feminine domestic music-making and of European bourgeois culture transported to the hinterlands of the nation or empire; it also functions as a gender technology because it regulates the metaphorical sound-body of the woman who plays it. As composer Michael Nyman explains about how his music for The Piano represents the character of Ada (Holly Hunter), “The sound of the piano becomes her character, her mood, her expressions, her unspoken dialogue, her body language.” Self-willed and temperamental, Ada is depicted as a “forte” woman whose passionate playing threatens her marriage and the patriarchal social order around her.

Rose (Kirsten Dunst) in The Power of the Dog, in contrast, is a meek and dutiful “piano” woman who tries to play gracefully within the constraints of society, marriage, and motherhood. As explained in Dreams of Love, “The piano woman’s playing is often overseen by a figure of patriarchal authority who represents the regulation and containment of her sound-body” (186). Rose’s nemesis in this story is her brother-in-law Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch), a talented but cruel and manipulative rancher who humiliates her and effectively silences her playing. When she hesitantly practices Strauss’s “Radetzky” March, which she played for silent picture shows before she got married, Phil maliciously mimics her efforts on his banjo from his room upstairs. Dunst explains that she held ice cubes in her hands before filming the dinner party scene so her fingers would be stiff and shaky with a trembling nervousness. Petrified by anxiety, Rose barely plays two notes before quickly pulling her hands off the keys. “I’m so sorry,” she apologizes to her disappointed guests, “I can’t seem to play.”

“The grand piano serves as more than the emblematic instrument of feminine domestic music-making and of European bourgeois culture… it also functions as a gender technology because it regulates the metaphorical sound-body of the woman who plays it.”

This moment in the film doesn’t seem to cohere with the backstory. Rose admits that she had once “played in the cinema pit for hours and hours,” a job which would involve improvising to whatever might be happening on the screen for an extended length of time, but now she can’t bring herself to play something, or even fake it, for a minute or two at this dinner in her home?

Campion’s film adheres to the original novel by Thomas Savage, first published in 1967, but the screenplay diverges from the novel in this scene. In the novel, Rose admits to her guests that “I’m terribly out of practice,” but she does play an entire piece, even if it is with an anxious detachment. “Somehow she got through an easy Strauss waltz, not daring to do more than play it mechanically as a child might repeats ABC’s, mindlessly” (154). When she next tries to play her husband’s favorite piece, however, she just freezes up, “appalled that her fingers had no feeling whatsoever, no knowledge. She folded her hands in her lap, and looked at them. … ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, ‘but I can’t remember it.’” There is a more complicated psychological dynamic at work here in the novel as Rose is torn between her love for her husband and her fear of her brother-in-law, who has deliberately skipped the dinner gathering. “It hadn’t been stage fright at all. Playing before a governor no more exposed oneself to criticism than playing before an audience in the pit of a motion picture palace or for a group of diners. Would he think it queer than she had simply been paralyzed by the eating utensils of someone not present?” (156)

While this portrayal of Rose conforms to established cinematic tropes around the “piano” woman who is self-deprecating about her talents and whose playing is constrained by patriarchy, these notions are also evident in real-life discussions about the film scene and the acting involved. In one interview, Dunst describes how she took lessons from piano coach Jeff Kite and practiced the Strauss march for this scene insistently, though her regimen was rather disruptive to domestic tranquility. “So that was really annoying in our household,” Dunst relates, “our friends hearing the same piece of music over and over every night.” Even her real-life husband (Jessie Plemons) found it somewhat tiresome, Dunst admits. “Every time after I’d put the kid to bed, I’d just work on the piano, work on the piano—they were so sick of these pieces.” In another interview, Dunst notes that she had to learn to “play piano badly” for the film, and her description of the dynamics of the playing scene in the film mirrors her practicing at home: “I think whatever’s happening in the house is really making her feel so insecure about even, like, working on her stuff.” Her NPR interviewer Terri Gross even recalls her own similar experience: “I was just, like, your average kid who took piano lessons and didn’t play very well. But I did sometimes have to play in front of the auditorium. … I’d get so nervous and so uncomfortable and always feel like I was going to blow it.”

In one scene in Campion’s The Piano, the weather-beaten Broadwood grand gets tuned after its arduous journey through the jungle, and Ada and her daughter are surprised to hear its newly harmonious scales. The “temperament” of a female pianist character can be represented sonically in a film by the strains of an (un)tuned piano, with those consonances or dissonances and the “regulation” of the instrument conveying her sound-body identity. Jonny Greenwood’s soundtrack score for The Power of the Dog includes a track titled “Paper Flowers” that utilizes an out-of-tune mechanical piano. The dissonant clanging timbres of this detuned pianola evoke the psychological condition of Rose’s character, as Greenwood explains: “Not only is her story wrapped up in the instrument, but it was also a good texture for her gradual mental unraveling.” The perpetual “piano woman” trope lives on in Campion’s most recent film both musically and visually, helping viewers understand this character and her condition even when she can’t play.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers