Oxford University Press's Blog, page 78

May 17, 2022

A Florence Price mystery solved (part two)

A significant find adds a new piece to the puzzle of Florence Price’s student experience as a woman of color in Boston’s cultural scene for the first time. This two-part blog series details research in progress for a volume on Florence Price written by Samantha Ege and Douglas Shadle for the Master Musicians Series. Read part one here.

A significant find adds a new piece to the puzzle of Florence Price’s student experience as a woman of color in Boston’s cultural scene for the first time. This two-part blog series details research in progress for a volume on Florence Price written by Samantha Ege and Douglas Shadle for the Master Musicians Series. Read part one here.Few direct traces of Florence Price’s time as a student at the New England Conservatory in Boston between 1903 and 1906 survive today, but we know that she was a high achiever. The 1906 catalog indicates that she was the only graduate to earn two diplomas that year, and concert programs show that she was an active performer on both piano and organ.

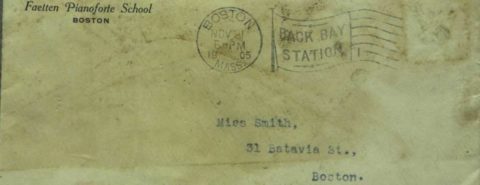

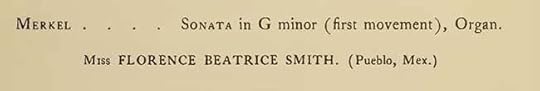

More pertinent to this story, the programs also shed light on her experiences specifically as an African American student. During her second year, 1904–5, two programs correctly list her hometown as Little Rock, Arkansas. In the following year, however, she is listed as a resident of Puebla, Mexico (“Pueblo”). No conservatory records explain this change. And, to my knowledge, only one surviving document—a 1967 note written by one of her daughters, Florence Robinson—addresses it directly. “My grandmother didn’t want my mother to be a Negro,” Robinson explained, “so when she took her to Boston, she rented an expensive apt. with a maid and forced my mother to say her birthplace was not Little Rock, but Mexico.”

Excerpts from Price (Smith) recitals, 26 Nov. 1904 and 5 Jan. 1906.

Excerpts from Price (Smith) recitals, 26 Nov. 1904 and 5 Jan. 1906.(Courtesy New England Conservatory Archives.)

Something prompted the hometown change—what exactly, we may never know. Her family certainly hadn’t moved to Mexico. But Robinson clearly linked it to Price’s living environment in Boston, thus connecting her experiences to those of previously displaced African American students like Fannie Barrier Williams, Maud Cuney, and Florida Des Verney.

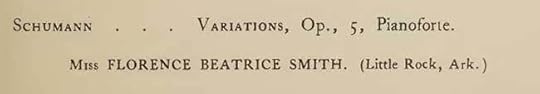

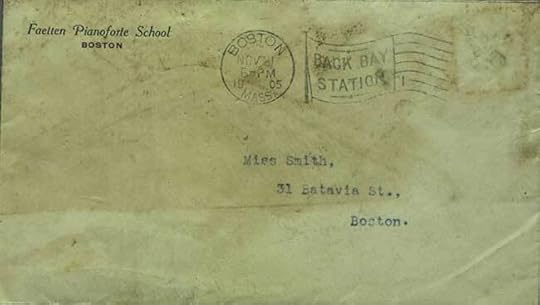

Price’s Boston address had eluded biographers until I visited the University of Arkansas Mullins Library in January. One afternoon, I was working through a relatively unprocessed collection that had sustained weather damage in the dilapidated rural house where it was found in 2009. And there it was: the address. Box 1B, Folder 24, marked “Publishing Information,” contains several letters from 1952, the year before Price died. Buried among them is a small envelope addressed to “Miss Smith” of 31 Batavia Street with a postmark dated November 1905.

Envelope addressed to Price (Smith) in Boston, Nov. 1905.

Envelope addressed to Price (Smith) in Boston, Nov. 1905.(Courtesy Special Collections, University of Arkansas Mullins Library.)

Boston city directory entries for 1905 and 1906 list a “Mrs. Florence I. Smith” at 31 Batavia—a name generic enough that it could be an unrelated person. But this Mrs Smith was unquestionably Price’s mother, Florence Irene, who had acquired an apartment there on her behalf. The envelope confirms it for the first time.

As part one showed, Batavia Street stood at the nexus of an emerging arts district and was ideally situated for students. But it was also not where most out-of-town students lived. After NEC moved from the South End in 1902, it contracted with private landlords to oversee residences for women just around the corner on Hemenway. The move, in fact, had been prompted in part by the administration’s aversion to running a dormitory. A delighted Charles Gardiner, president of the board, told the trustees in January 1903, “We have passed through the most remarkable and eventful year in the history of our Conservatory. We have vacated the building on Franklin Square, which we had occupied for 20 years, and in making this move to our present building we forever separated the academic department from the dormitory.”

Why, then, would Price live apart from her classmates? Although we have no definitive proof, circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that, like her predecessors, Price first lived in a conservatory-sponsored building but moved to 31 Batavia in response to racism from other residential students.

Price explained in a 1941 letter that she had moved to the northeast precisely to avoid racial discrimination. “When I graduated high school,” she wrote, “there was no opportunity open to me—a colored girl—for obtaining a formal and inclusive training in a course in music.” Her uncle, attorney J. Gray Lucas, had attended law school at Boston University in the 1880s, and his knowledge of the city might have informed her choice to look there. And she would have been especially attracted to the thirteen pipe organs in the new NEC building—“more than double the number of organs under any other single roof in the world,” as the 1902 catalog touted.

The new building also attracted a sizeable student population from other southern states—those where segregationist laws had been in force for over a decade. During Price’s first year, she was the only student from Arkansas, while 96 others (or 15% of the out-of-state enrollment) came from elsewhere in the South. Subsequent catalogs show that the total swelled to 119 over the next two years, including four more from Arkansas. Meanwhile, the enrollment from Mexico increased by one during the 1905–6 school year. That student must have been Price.

If nine white southerners left the conservatory after refusing to live with Cuney and Des Verney in 1890—and these were only the most resolute bigots among those who protested—it seems plausible that at least a handful objected to Price’s presence in one of the boarding houses and tormented her. Without direct control over the homes, the conservatory could do little to intervene in conflicts. To counter this behavior, then, Price’s mother insisted that she finish her diploma with a new residence, a new family background, and even a paid servant. If the conservatory wouldn’t provide the environment she thought her daughter deserved, she would.

As historian Kira Thurman has shown in her recent book Singing Like Germans, Black students (musicians or otherwise) routinely encountered racism from southern white students at predominantly white institutions despite receiving unqualified support from the faculty. For many of these students, Thurman explains, class-based respectability politics informed their responses to racist encounters. During the 1890 controversy, for example, Florida Des Verney told the Globe that she had “entered the conservatory with a determination to acquit myself in such a manner as to be a credit to my race”—an attitude that aligned with the values of Price’s immediate family, who were professionals in dentistry, law, and business. Price’s daughter found these attitudes distasteful, at least in retrospect, and accused her grandmother of denying their African heritage altogether.

Passing as Mexican (or “Spanish”) was not uncommon for relatively fair-skinned people of African ancestry. In 1907, it became a central point of conflict in Maud Cuney’s divorce from her first husband, who insisted that they avoid all contact with Black friends to maintain the public perception of Mexican ancestry—what historian Allyson Hobbs has called a “chosen exile.” But Price, like her predecessors, found herself facing an impossible dilemma in the absence of institutional intervention: how to manage racist behavior while maintaining her safety and continuing her education. Price and her mother might have believed that taking advantage of colorism while asserting their social class was the path of least resistance. After all, Price completed her difficult studies in only three years.

Although 31 Batavia Street may seem like a minor detail in the life of an extraordinary composer, it opens new vistas for considering how the built environment shapes people’s lives. During the arson-for-profit scandal of the 1970s, the cabal who set the fires blamed the behaviors of the Symphony Road neighborhood’s marginalized residents—students, sex workers, immigrants, the elderly, and so on—for their own victimization, compelling them to seek justice through community activism. The intersections of race and gender at the New England Conservatory offer a parallel case study in which institutional inaction led marginalized students—in this case, young women of color—to find solutions to problems not of their own making. “I cannot help it if am colored,” Cuney told the Globe in 1890, “and stay I shall.”

Thank you to Samantha Ege (Lincoln College, University of Oxford) and Maryalice Perrin-Mohr (Archives, New England Conservatory) for feedback on drafts of this essay, and to the Special Collections staff at the University of Arkansas Mullins Library.

May 16, 2022

Five ways to support international students studying in the UK

Going to university for the first time, or embarking on graduate study, is a significant transition for anyone. Doing it in an unfamiliar country, where you have no support network, are unaccustomed to the idiosyncrasies of the daily life and daunted by an alien academic culture, can be overwhelming—and that’s before we even consider that you may be doing all this in a second language!

In a globally mobile world where international experience is increasingly valued and intercultural skills are crucial, universities are constantly reviewing and improving how they prepare and support their international students, using tools like Epigeum’s International Student Success course to give students the head start they need to not only succeed but to thrive. Providing a solid knowledge base and using real-life examples to prepare students for the highs and lows of studying in a new country, such resources can be extremely powerful when the learning is then complemented by on-campus initiatives—from orientations to excursions to buddy schemes—once the students arrive. While we do not have unlimited resources at our disposal—least of all time—there are a number of things we can bear in mind as we, as education practitioners, continue to support international students on their exciting journey with us.

1. Knowledge is powerThere is a sort of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to studying in a new country: before students can thrive, they need a level of basic knowledge about the practical aspects of studying abroad, such as how to obtain a visa, how academic structures work, how assignments will be graded, what “plagiarism” means. They will also need to know how to function in their particular location—how to use local transport, where to buy food, where and how to ask for help. Once these needs are met—usually by a combination of pre-departure study such as International Student Success and in-country orientation and support—students are empowered to immerse themselves in their new environment.

2. Prepare for them to be unpreparedEven with the most conscientious preparation, anyone who finds themselves in a new environment—be they from Beijing, Boston, or Bradford—will inevitably come across situations that trip them up. Often as professionals we are so keen to impart every available bit of information to students that we forget to warn them that it is impossible to prepare for every eventuality. Being open to the unexpected is an important tool in anyone’s emotional armour and should be incorporated into any pre- or post-arrival activities.

3. Encourage involvementWhen I have one-to-one meetings with my students, I always ask them what they’re doing outside of class. Despite our attempts to promote the plethora of clubs, societies and other activities at their disposal, it always surprises me how many say they don’t have time for such things as they need to focus solely on their academic work, or on means-to-an-end endeavours such as securing an internship. While these things are of course important, I stress to my students the many benefits of extra-curricular participation are many: not only does it help develop skills that cannot be learned in the classroom, it is also important to wellbeing. Friendships, and, in turn, increased cultural confidence, can be fostered through such activities. While we, as educational professionals, know this, how do we actually encourage students to take up these opportunities, and how could we do better?

4. Nurture the individualEvery person is different. As busy professionals—indeed, as human beings—it’s tempting to put students into categories, the most obvious being home students and international students. But each person brings their own unique set of experiences and unique culture with them when they come to the UK; their race, sexuality, gender identity, socioeconomic background, hometown, schooling, interests, and political outlook will all have contributed to who they are alongside their broader national identity.

Studying abroad is a huge exercise in self-discovery, and reflective activities that encourage students to explore their identities beyond national borders are important in helping them find their place in their new world. Many activities on the Epigeum course encourage students to think about how they, as individuals, would feel and react to certain situations, and continuing to nurture the individual and encourage each student to forge their own path can reap huge rewards for student and institution alike.

5. Be proactiveLearning and adjustments don’t end with pre-departure briefings or an orientation. I have worked at institutions that have fun wonderful orientation programmes, but those programmes end with a sense that when the students, armed with everything they will need to survive in a new world we have explained to them in painstaking detail, are released into the wild, our attentions immediately turning to the next cohort. Conversely, I have seen students many months into their programme who have found themselves in my office when some incident—academic failure or misconduct, health concerns, lack of attendance—flagged to us that they were not in fact thriving. Those students have told me that they didn’t feel they could seek help earlier as they “should” have been able to cope on their own, and saw asking for help as a sign of weakness. Anything we can do to prevent students feeling this way, such as occasional check-ins, open house events, and refresher orientation sessions, to encourage and normalise the idea of seeking help when needed can make a huge difference.

May 13, 2022

The curious popularity of “however” in research articles

There are many ways to signal a change of direction or mood in a piece of text, but the most common is by inserting a “but”—as I’ve just done here. Alternatives such as “although,” “though,” “however,” “yet,” and “nevertheless” generally run a poor second. In fact, according to Google Books Ngram Viewer and the British National Corpus, each occurs around a tenth as often as “but.”

In research articles, though, the prevalence of “however” increases—especially in some disciplines.

I searched Elsevier’s Scopus database for article abstracts containing “however.” I then compared them with those containing “but” to bypass any differences in text length. In arts subjects, abstracts with “however” occurred around half as often as those with “but,” more precisely 54% as often, at the time of writing. In the social sciences and life sciences, it was 74% and 75%, respectively, and in the physical sciences, it was 85%. But in engineering it was 100% (1.4 million documents each for “however” and “but”).

Here’s an example from an engineering abstract, with sentences slightly shortened:

However, almost all the studies have been conducted using an actuated or electric device. However, using an electric device has several disadvantages.

The engineering enthusiasm for “however” isn’t peculiar to abstracts. I examined a sample of about 1,000 full journal articles from the physical, life, and behavioural sciences, mathematics, medicine, and engineering. In the non-engineering subjects, “however” appeared 65% as often as “but,” whereas in engineering subjects, it was 97%, within sampling error.

So, why do engineers particularly like “however”?

One possibility, suggested by a colleague, is that they’re more inclined to observe the rule that “but” should not start a sentence and they fall back on “however” instead. But as Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage points out, over several editions, the rule has no foundation in either grammar or good writing.

Moreover, in a closer look at that sample of articles, I found that engineers were little different from non-engineers in preferring “however” to “but” at the start of a sentence.

Another suggestion was that it’s not that engineers like “however” but that they dislike “but”—wherever it’s placed. They see it as less polished, less formal. Disappointingly for this idea, although “but” appeared in the sample less often in engineering subjects, so did the alternatives “although,” “though,” “yet,” and the clearly more formal “nevertheless”. It seems “but” isn’t the problem.

Rather, a simpler explanation might hold. Engineers—and others—are more likely to see “however” as a universal tool for signalling direction change, and the ready default in most circumstances. As one former engineer described it, “however” was his go-to option, something that could always be relied on.

Yet there are so many alternatives, each with a slightly different meaning and effect.

Along with those listed earlier, they include “still,” “even so,” “even then,” “even though,” “conversely,” “nonetheless,” “notwithstanding this,” “instead,” “for all that,” “all the same,” “despite this,” “in spite of this,” “that said,” “by contrast,” “in contrast,” “on the contrary,” “alternatively,” and “on the other hand” (which, incidentally, needn’t have an earlier “on the one hand” to work). Still more can be found in Quirk and colleagues’ A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language.

Whatever your research discipline, quantitative or not, if you’re a heavy user of “however,” why not try abstinence for a while and experiment with the alternatives? Though not too many at once in case they give the reader whiplash.

If you then want to reintroduce “however,” sparingly of course, follow the advice of the journalist and teacher William Zinsser in his guide On Writing Well:

Don’t start a sentence with “however”—it hangs there like a wet dishrag. And don’t end with “however”—by that time it has lost its howeverness.

Zinsser goes on to say that you should then put it as early as you reasonably can. But as “however” draws attention to what precedes it, finding that early position can sometimes be difficult. For example, in the previous sentence, if you wanted to insert “however” (having removed the leading “But”), the natural place for it would be at or near the end, where it doesn’t work.

Luckily, so far in this piece, I’ve been able to signal direction changes solely with alternatives to “however.” I’ve avoided using it at the beginning of a sentence and at the end, and indeed anywhere between the two. As an indulgence, however, I’ve allowed it into this last sentence—which is enough.

Featured image via Flickr (public domain)

May 11, 2022

The sour milk of etymology

In 2018, I devoted three blog posts to the origin of the English words bread and loaf (see the posts for 17 October, 24 October, and 7 November 2018). Once I even discussed brisket (20 October 2010). The time has come to write something about the etymology of the word milk. Don’t hold your breath: “origin unknown,” that is, no one can say why milk is called milk, but then no one can say why water is called water either, except for connecting wet with water. It would be useful to have some semantic ties, with milk meaning “white stuff” or “nourishing product,” and water going back to a word for “thirst.” Alas, in dictionaries, one finds bare roots: melg– and wat-, which are neither obviously sound-symbolic nor sound-imitating. Yet someone in the remotest past coined those names, and they evoked certain associations! Anyway, water was always around, at least in the form of rain, while the first contact of humans with milk must have been through breast feeding, that is, long before the most ancient speakers of Indo-European learned to milk cows. (I’ll return to breast feeding at the end of this post.) Or the word may have referred to some stuff seen on plants. Yet no word for “liquid’ or “white” resembles milk.

[image error]Madonna Lita (Madonna Lactans)(From The Hermatige, St. Petersburg, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

We can say with enough confidence that once upon a time the Indo-Europeans did use milk. English speakers take it for granted that the verb milk is derived from the noun milk, but the two words may go back to different roots (see below). More relevant to English is the adjective milch (a milch cow, that is, a cow giving milk), which, according to my experience, hardly anyone understands today.

The main riddle is the great similarity of words for “milk” in numerous languages, a true embarrassment of riches. In Germanic, Gothic miluks (recorded in the fourth century), German Milch, Icelandic mjölk, and so forth occur. The faraway Tocharian word is malke. Closer to home we find Latin mulgeo and Greek amélgo “I milk,” though side by side with those words, Latin lac/lactis (as in English lactate) and Greek gála/gálactos “milk” display a different root. Apparently, related to lact– is Hittite galaktar “a sweet plant juice used in rituals.”

The situation is confusing because many words related to milk and milking sound alike but do not seem to be cognate. A classic example is German Milch “milk” and melken “to milk.” The verb seems to be akin to Greek amélgo “to draw, pull” and Latin mulgēre “to milk” (Old Irish mlegon also means “drawing, milking”). It seems almost incredible that Milch and melken should be unrelated. Even if etymological algebra draws them apart, why are those near-twins offspring of different roots?

It has even been suggested that in the history of the words for milk some sounds were at one time changed deliberately under the influence of taboo. Indeed, milk was such an important product for both consumption and ritual purposes that the word may have been modified intentionally. Ritual words are often altered for fear of offending the powers that be. But the existence of taboo in history can seldom be demonstrated, and reference to it is destined to remain an ingenious guess. As far as we can judge, milk served as the name of the product, while milking was associated with drawing.

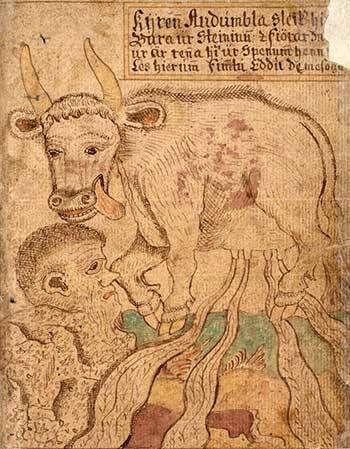

Authhumla, the primordial cow of the Norse myth. She fed the giant Ymir, from whose body the entire cosmos was made.

Authhumla, the primordial cow of the Norse myth. She fed the giant Ymir, from whose body the entire cosmos was made.(By Jakob Sigurðsson, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Even if we agree that a common very ancient Indo-European word for “milk” did not exist, we have enough trouble with Germanic. The trouble comes from the Slavic side. Slavic for “milk” sounded approximately mleko (Russian moloko, stress on the last syllable; Polish mleko, stress on the first syllable, and so forth.) Those who have read the post on loaf (see the beginning of this blog post) may remember that the Russian word khleb “bread” is almost certainly a borrowing from Germanic. If khleb could be taken over from Germanic, why not mleko? But we may ask: why should anyone borrow such basic words from the neighbors? As regards loaf ~ khleb, the answer is not far to seek. Bread existed in several forms (for example, leavened and unleavened; as a brick or as a flat pancake, and so forth). But milk from a cow is just milk, and borrowing seems to be unlikely. Yet nothing is certain in this area of knowledge. The Old Chinese word lac “milk” is believed to be a borrowing from eastern Indo-European. In Latin, melca “spiced milk” turned up, either a loan from Germanic (the prevailing opinion) or an illegitimate cognate.

Unexpectedly, the semantic base of the Slavic word is less opaque, because several words with the same root refer to wetness and dampness: “swamp; puddle; fog.” In Germanic, Gothic milhma “cloud” (a much-discussed noun) may be related. It appears that the Slavic root of the word for “milk” meant approximately “(a kind of) liquid.” No similar meaning suggests itself for Germanic. The few Sanskrit words that have been cited in this connection do not inspire confidence. Milk cannot be a legitimate cognate of mleko because Germanic k should correspond to non-Germanic g. For the same reason, Latin melca is a bad match for Germanic milk (by the First Consonant Shift, so often invoked in this blog, Germanic k should correspond to non-Germanic g).

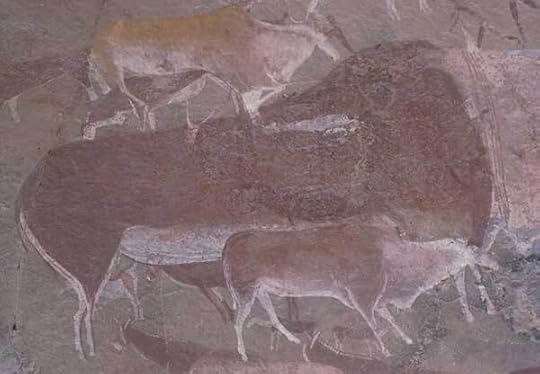

Cave paintings of cows are numerous.

Cave paintings of cows are numerous.(Eland cave, Drakensberg, South Africa, via Fondazione Passaré, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The story is disappointing. Over a huge territory, people used the m-l-k word for “milk” and “milking,” which often turn out to be partly unrelated, with most of them being of obscure origin. By way of compensation, I may add that the cow played a noticeable role in Indo-European mythology. In the Rig Veda, a collection of ancient Vedic hymns, a dairy cow and its milk are often used as symbols of world fertility. (If some of the most ancient beliefs connected milk and fertility, the idea of taboo again begins to look less fanciful, because saying aloud words connected with procreation is often prohibited). According to the Scandinavian creation myth, the giant Ymir was licked from the ice by the primordial cow Auth-humla, whose name is a matter of speculation. It must also be a great comfort to our readers that the etymology of the noun cow is indeed known (no connection with milk).

Not versed in Sanskrit etymology, I would dare make a suggestion, probably made and rejected many times before me. Sanskrit dádhi “yogurt” (as pointed out by specialists, perhaps of cultic significance because of a priest’s having a name with the same root) sounds very much like Gothic daddjan “to suckle.” Daddjan is usually traced to the form dajjan, but this verb seems to be such an obvious baby word (“a word of infantile origin,” as serious sources put it) that I doubt the validity of the current etymology, which is perhaps too learned. Surprisingly, in the many words for “milk” in Indo-European, no references to baby feeding has turned up, but this is only one of the many riddles briefly touched upon above.

Featured image from State Library of South Australia via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0.

May 10, 2022

A Florence Price mystery solved (part one)

A significant find adds a new piece to the puzzle of Florence Price’s student experience as a woman of color in Boston’s cultural scene for the first time. This two-part blog series details research in progress for a volume on Florence Price written by Samantha Ege and Douglas Shadle for the Master Musicians Series.

A significant find adds a new piece to the puzzle of Florence Price’s student experience as a woman of color in Boston’s cultural scene for the first time. This two-part blog series details research in progress for a volume on Florence Price written by Samantha Ege and Douglas Shadle for the Master Musicians Series.Composer Florence Price (1887–1953) has experienced an extraordinary resurgence on concert stages in recent years. Since January alone, dozens of orchestras in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, and even Chile have performed her radiant music, while outstanding new recordings are capturing it for posterity. The pronounced interest is long overdue. Price, an African American woman, fought to achieve a fraction of this recognition during her lifetime.

As her biographer Rae Linda Brown once noted, “the necessary evidence to write a detailed biography is surprisingly scant.” Indeed, even fundamental facts about Price’s life can be difficult to confirm. Yet a significant new find at the University of Arkansas Mullins Library, which holds most of Price’s manuscripts, puts in place a major puzzle piece surrounding her student experience as a woman of color at Boston’s New England Conservatory.

Price’s student address, 31 Batavia Street, had long eluded previous biographers. Called Symphony Road since the 1930s, the surrounding neighborhood comprises a pocket of streets and public alleys tucked between Symphony Hall and the Back Bay Fens. It’s also home to a fascinating, even scandalous history. In the 1970s, the neighborhood entered national headlines after its depleted residents uncovered a deadly arson-for-profit corruption scheme that had brutalized them for years. A few decades earlier, Babe Ruth was a frequent guest and even lived there for a time just after joining the Red Sox in 1914.

Beyond its proximity to the famed Symphony Hall, the neighborhood is also important in the history of American classical music, for it has housed students at the New England Conservatory since 1902, the year before Price matriculated there. At the time, the conservatory was one of only a few large musical institutions that admitted students of color, and providing safe housing for out-of-state residents posed perennial challenges. The conservatory went to great lengths to shield women from unwanted male callers, yet how to manage white women’s hostility toward women of color fell on the students themselves. Price developed multiple strategies for protecting herself, including living away from the main student residence. Though a seemingly minor detail, Price’s Boston address illuminates how race, gender, and the built environment converged to shape Price’s student experience.

31 Symphony Road, March 2022.

31 Symphony Road, March 2022.(Photos from the author’s collection.)Race, gender, and housing at the New England Conservatory

Founded in 1867 by choral conductor Eben Tourjée, the New England Conservatory originally operated in rooms attached to Boston’s downtown Music Hall (now the Orpheum Theatre). During its early years, the director gave advice to out-of-state students about where they could live but offered no guarantees about the suitability of rooming conditions. By 1882, the spaces in Music Hall had become insufficient for growing enrollment, prompting the trustees to purchase and then renovate the South End’s sumptuous St. James Hotel (now the Franklin Square Apartments) into a space for residential education.

Touted in the 1882 catalog as “the largest and finest conservatory building in the world,” the renovated hotel became the central marketing tool for attracting out-of-state students. Tourjée believed that the potential drawbacks of living away from campus—dishonest landlords, unsanitary conditions, unreliable transit, and so on—had convinced many parents to avoid the conservatory in the past, whereas he could now maintain far more control over the conditions in an attached dormitory. “The great Building is not only admirably adapted for Conservatory use,” the catalog boasted, “but has every modern advantage for a model home.”

In addition to bedrooms for 550 students, amenities in the new building included a concert hall, a library, reading rooms, practice rooms, and parlors, all overseen by a “Preceptress.” The park in the adjacent Franklin Square offered a beautiful outdoor environment. These were exactly the features that would have appealed to Norris Wright Cuney, a prominent political figure from Galveston, Texas, and Anthony Des Verney, a wealthy cotton broker from Savannah, Georgia. Their daughters, Maud and Florida, wanted to pursue sound musical training in addition to an excellent general education—precisely what the conservatory promised.

Maud Cuney Hare, ca. 1913

Maud Cuney Hare, ca. 1913( Norris Wright Cuney: A Tribune of the Black People by Maud Cuney-Hare, public domain.)

The two women matriculated in September 1890 and moved into adjacent bedrooms in the dormitory. Within weeks, a few white students complained about having to share living accommodations with Cuney and Des Verney, especially the dining area, and ultimately petitioned for their outright removal. Cuney and Des Verney, meanwhile, protested that the other women routinely harassed them. The conflict entered public view when the Globe reported that the conservatory administration had sent letters to Cuney’s and Des Verney’s parents apprising them of the situation, declaring that “there seems no adequate solution save in the disposition of the parents of colored pupils to provide them a home outside the Conservatory.”

This winding locution suggested that the incident wasn’t the first of its kind, and indeed it wasn’t. Tourjée quietly dismissed Fannie Barrier Williams from the conservatory altogether in 1884, arguing that threats from white students to leave the school endangered its solvency. The Globe report about Cuney and Des Verney, however, immediately circulated in major national newspapers, leading local Black citizens to mobilize on their behalf. Members of the Colored National League, a civil rights organization, threatened legal action on the grounds that the conservatory received state funds and was thereby required to offer all services equally. The trustees ultimately changed course and allowed the two women to stay in the dormitory if they wished. Des Verney declined, completing her studies for the term while living elsewhere, while Cuney remained and endured, as she put it, “petty indignities” from other students for the rest of the year. At least nine students from southern states left because the trustees allowed her to stay.

The Batavia Street neighborhood and urban expansionThe controversy’s broader context involved the rapidly changing geographies brought on by urban expansion, population booms, and especially improved transit. The year 1890 witnessed the introduction of several segregated railcar bills in southern states, for example, which drastically reshaped mobility patterns. By the time Price matriculated in 1903, Batavia Street and the surrounding area had also experienced a dramatic transformation that, as musicologist Jacob Cohen has argued, shifted the center of gravity of classical music in Boston.

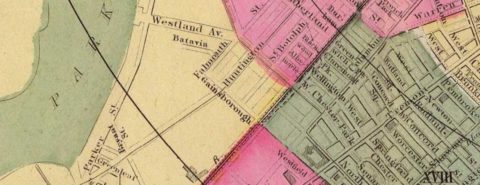

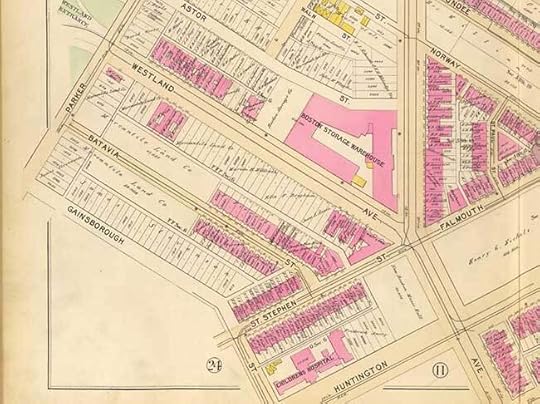

First laid in the mid-1880s by real estate speculators Ira Moore and Jesse Tirrell, Batavia initially offered a lower-cost alternative to the luxury homes available in the Back Bay to the north, as well as easy access to the Back Bay Fens park being developed by Frederick Law Olmsted just to the west. A map from 1888 shows an incomplete Batavia situated within an undeveloped area south of the Fens. The nearest notable landmark (not shown) is the 60-bed children’s hospital on the northwest corner of Huntington and Gainsborough. (This institution moved to Longwood Avenue next to Harvard Medical School in 1914.)

Batavia Street, ca. 1888

Batavia Street, ca. 1888(David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, public domain.)

Meanwhile, population growth was straining the city’s transit system, causing traffic congestion along main thoroughfares that lowered the quality of life. The Harvard Bridge, finished in 1892, relieved some of this pressure by connecting Cambridge to Boston via Massachusetts Avenue, ultimately making the neighborhood around Batavia accessible from all directions. Directories from the 1890s list students from MIT and Harvard with addresses there, particularly along Westland Avenue.

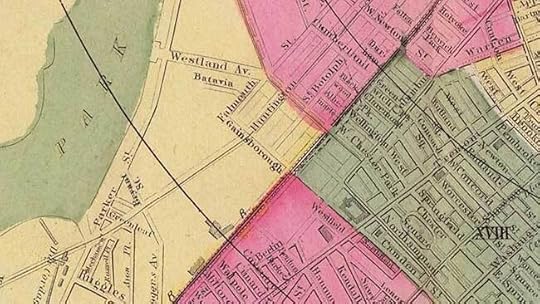

Construction of a new elevated train, proposed in 1893, threatened to disrupt activity at Music Hall, home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra since its founding in 1881. Although the project was ultimately scrapped in favor of the Tremont Street subway, orchestra executive Henry Lee Higginson purchased a plot for a new concert hall along Massachusetts between Huntington and St. Stephen—a location visible at the corner of Batavia. A detailed 1895 map shows that Jesse Tirrell owned a series of row homes along Batavia up to #33, with the rest of the land along the street owned by a land development company. (The children’s hospital and the eventual site of Symphony Hall are also clearly labeled.)

Batavia Street, ca. 1895

Batavia Street, ca. 1895(David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, public domain)

Soon after becoming director of the New England Conservatory in 1897, composer George Whitefield Chadwick urged the trustees to move out of the South End property because the dormitory was too expensive to maintain. Higginson suggested finding property near the proposed site of Symphony Hall, arguing that proximity to the orchestra would benefit students. Just a few months before the hall opened in 1900, the Globe remarked that it had “attracted the attention of investors and institutions as a most desirable location for large buildings for public purposes, being easily accessible from all points of Boston and suburbs.”

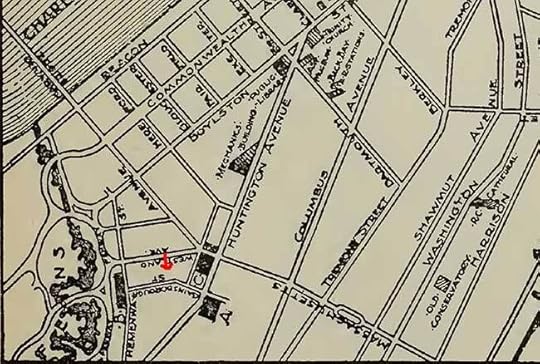

The conservatory trustees followed suit by purchasing a plot south of Gainsborough Street between Huntington and St. Botolph. Ground broke on the new building in 1901, and it opened for the fall session a year later. A new annual catalog boasted that “the building is directly in the art center of Boston, being located one block west of Symphony Hall and within a short walking distance of Boston’s famous public library, the Art Museum, and other public buildings of interest.” Indeed, by the time she arrived, it was ideally situated for a student like Price to absorb the city’s performing arts offerings in abundance, as the dozens of programs she collected attest.

Batavia Street, ca. 1907

Batavia Street, ca. 1907(From Map of the city of Boston and vicinity via The Library of Congress, public domain.)

Unlike the previous location, however, the new conservatory building did not contain a residence hall for women. Instead, the catalog noted, “young women coming from a distance to attend the Conservatory will find superior boarding accommodations in residences which have recently been completed and arranged for their exclusive benefit.” A map appended to the catalog shows that the new residences were along Hemenway Street (formerly Parker) along the edge of the Fens. How this new urban geography shaped Florence Price’s experiences at the conservatory is the subject of part two.

New England Conservatory Catalog, 1902, A. New building, B. Dormitory, C. Symphony Hall. New England Conservatory Archives.

New England Conservatory Catalog, 1902, A. New building, B. Dormitory, C. Symphony Hall. New England Conservatory Archives.

May 9, 2022

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is another tragic setback in our efforts at building a sustainable future

To say that wars cause disruption and hardship is stating the painfully obvious. Regardless of attempts—real or professed—at limiting civilian casualties, military conflict always unleashes suffering on the civilian population. Once again, as in the Balkans in the 90s, in Syria in 2011, and in countless other conflicts before, today in Ukraine civilians are huddling scared in basements or scuttling towards safety in neighboring lands.

Yet the Russian invasion of Ukraine brings another stark truth to the fore: without peace, our efforts at building a sustainable future are predestined to fail. The consequences of such a failure are dire. In March, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) announced in no uncertain terms that we are at a critical juncture and that only with immediate action can we avoid a climate disaster.

The fact is that we have in the last decade taken modest but meaningful steps towards a more sustainable future. This can be seen in our progress on achieving the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which were launched in 2015 as a unifying framework for achieving sustainable development.

The Coronavirus pandemic proved a major disruptor to these efforts, however. According to the UN’s own assessment, COVID-19 “led to the first rise in extreme poverty in a generation,” cast between 70 and 161 million people into hunger, and “wiped out twenty years of education gains”—to name but a few of the dire conclusions.

What we need today, as we slowly emerge from the worst of the pandemic, is a redoubling of our efforts at combating the global challenges of sustainable development. Yet the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the increasingly strained geopolitical climate that is following in its wake threatens to derail such efforts.

War obviously takes human lives, destroys vital infrastructure, derails economic activity, and causes a host of other social and economic damage in the region directly affected. History shows us, however, that the disruptive effect of war also runs deeper and far beyond the geographic limits of fighting. In recent decades, historians have documented in painstaking detail how past wars have thrown a monkey wrench in our delicate relationship to nature. Indeed, the mere threat of war—such as during the tensest days of the Cold War—can run roughshod over cultural and political constraints on overexploiting the environment. Such a ripple effect can already be felt today too, as the war in Ukraine is causing food prices to rise precipitously from Berlin to Benin.

The world was obviously not peaceful in the years before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Many have, rightly, called out the massive Western reaction to the war compared to other conflicts in the Global South as being at best a double standard, at worst racist. Be that as it may, it is exactly this overwhelming reaction that suggests that this war, more than others, will have far-reaching consequences for sustainability.

While the long-term consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the international system remain to be seen, there is some concern it is the foreboding of a new era of global conflict. This is especially so, if we read it in parallel with China’s increasing assertiveness and disengagement from the West. Whether predominantly cold or hot, such a systemic change would have a triple negative effect on sustainability efforts.

For one, it would stunt political will and sideline the climate crisis from the headlines, as Europe, the US, and other regions redirect needed human and financial resources to rearmament (already today, such commitments can be heard from the halls of Berlin and other capitols). Second, and equally destructive, a new Cold War would at best clog, and at worst sever the multilayered international connections that are fundamental to mounting a coordinated effort at addressing the global drivers of climate change and inequality. Finally, just as during the Cold War, financial and technological support to emerging economies may become contingent on ideological alignment rather than a commitment to the environment or citizens.

Since their inception in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals have been seen as intimately interlinked—the logic being that progress on, say, building sustainable cities (SDG 11) is contingent on responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), and so on. In a new book on the SDGs, Christine Smith-Simonsen writes of SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) that “it can be argued that the achievement of this one goal [peace] is a precondition for the success of the others.” Three months ago, Smith-Simonsen’s claim would have seemed exaggerated. Today, faced with a new reality, who would disagree.

Featured image by Karollyne Hubert on Unsplash (public domain)

May 6, 2022

A literary history of Modernism [timeline]

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a period of transformation in both artistic and philosophical movements. It was a movement that reflected the rapidly industrialising world, where literature was moving away from classical and traditional forms. Some consider modernism a mode of thinking, while others consider it a re-examination of all aspects of existence.

In the timeline, we explore some key figures and events that contributed to shaping modernism and celebrate 100 years since 1922—the pinnacle year of modernist publishing!

Featured Image: typewriters on the beach by Matt Artz via Unsplash

May 5, 2022

Renewable solar energy: how does it work and can it meet demand?

For years, solar energy has indirectly provided us with different sources of energy. The energy in fossil fuels originally comes from solar energy, trapped in the dead organisms such as algae, prehistoric plants and animals, and plankton that eventually transition to fuels. Also, bioethanol is produced from different crops, such as corn and sugar cane. Hydroelectric power would not be possible without solar energy to create rain and snow to grow rivers and wind energy relies on solar energy to heat the earth and create air movement.

What are the main solar energy technologies?The direct use of solar energy to produce electricity on a utility scale is more recent and falls under two main categories, namely solar photovoltaic (solar PV) and concentrating solar power (CSP). Solar PV is the production of electricity from sunlight via the photovoltaic effect, which is both a physical and chemical phenomenon. When a photon particle from sunlight strikes a photovoltaic cell, some is absorbed by a semiconductor in the cell to create electron current and, hence, electricity. These semiconductors are chemical compounds with limited ability to conduct electrical current and are neither good insulators nor good conductors. CSP, also known as solar thermal, concentrates sunlight using mirrors and then uses this heat to produce steam. This steam, once made, will power a turbine to generate electricity. In this respect, CSP generates electricity in the same way as conventional technologies such as natural gas, coal, and nuclear power.

CSP technologies are divided into two groups, based on whether the solar collectors concentrate sunlight along a focal line or a single focal point. The most common technology used is a focal line technology called the parabolic trough. Here, parabolic mirrors concentrate sunlight and heat a fluid in a central receiver tube. After heating, this hot fluid is used to boil water to make steam and power the steam turbine, which in turn powers the generator to make electricity. An example of the single focal point technology is the solar tower, which uses a field of mirrors to focus sunlight onto a receiver mounted high on a central tower. The mirrors in this field are computer-controlled to track the sun.

The growth of solar energy technologiesUtility scale electricity generation using these technologies has grown rapidly. Before 2005, there was very little solar PV, only 0.5 GW in the US and about 5 GW worldwide. For reference, a 1 GW power plant will provide electricity to around 180,000 homes. By 2020, solar PV had grown to 710 GW worldwide, a growth of around 900% over the last 10 years. Likewise, in the US, solar PV has grown to 73.8 GW, a growth of 1,300% over the last 10 years. In contrast, CSP has not seen the same growth, and in 2020 there was only 6.4 GW installed worldwide with most in the US and Spain.

The growth in solar PV can be attributed in large part to decreasing capital cost. In 2013, a solar PV plant cost $3,700/kW, but decreased to $1,300/kW in 2019, or 35% of the 2013 value. This makes it more competitive with a natural gas plant, with a capital cost of around $900/kW. By comparison, CSP has seen little change in capital cost and languishes around $7,000/kW.

Can solar energy meet global demand?Unlike fossil fuels or nuclear power, where it is possible to assess proven reserves, the assessment of solar energy potential is more difficult. Worldwide potential can, however, be estimated using a broad mathematical approach:

Taking into account the surface area of the earth and recognizing that the average solar flux striking the atmosphere of the earth is 342.5 W/m2 (watts/meter2), about 175,000 TW (terawatt = 1012 watt) reach the surface of the earth. Since 30% is reflected back to space and 19% is absorbed by the atmosphere and clouds, this leaves 89,300 TW reaching the earth to be absorbed by land and oceans. Ignoring the 71% of the earth that is ocean and the 3.5% of land that are in frigid zones as areas impractical for solar development, a potential of 2,500 TW can be calculated by assuming a solar PV cell efficiency of 10%. Solar panel efficiency is the percent of incoming sunlight that is converted to electricity, a value typically ranging from 10 to 15%. Assuming a capacity factor of only 10%, the 2,500 TW would generate 2,190,000 TWh in one year. As the world consumed 22,015 TWh in 2017, this means world energy consumption was only 1% of the potential electricity generation from solar energy!

The capacity factor is the fraction of electricity production compared to the maximum possible output, and this factor will vary based on latitude, the time of year, and cloud cover. While it is impractical to have solar panels dotting virtually every available surface of the earth, it does show the awesome potential of solar energy as a renewable energy to meet our needs for generations to come.

Featured image by Andreas Gucklhorn via Unsplash (public domain)

May 3, 2022

We are what we breathe: environmental factors in biological ageing

The world’s population is aging. For the first time ever there are more people over 65 than under five, according to the World Health Organization. By 2050, the world’s population of people aged 60 years and older will double. The number of persons aged 80 years or older is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050. There are two potential trends behind population aging: falling fertility and rising life expectancy. In a sense, population aging is a great achievement in the development of human society, but it is also linked to unanticipated and unprecedented medical and public health challenges. In particular, premature decline in physical function poses a threat to elderly pursuit of healthy aging.

Chronological age has always been how we define age. It does not, however, give a good indication of the degree of biological aging of individual—that is why you often see people who appear younger than they really are. Frailty is a good indicator of biological aging. It is a common geriatric syndrome characterized by multi-system impairments, along with a reduced capacity to resist external stressors. Imagine a young person or a middle-aged person who has experienced something bad, they will most likely recover quickly, whereas if the same thing happens to an older person, it is likely that they will never recover, or even be hospitalised or die, and this could be caused by frailty. Frailty is very common in the elderly population. Mounting evidence indicates a connection between frailty and environmental health which is crucial for understanding biological aging.

Environmental factors have been considered a global threat to accelerated biological aging. However, the effects of environmental pollutants on frailty have long been understudied, which raises concerns that one of the most vulnerable population groups may not be adequately protected from environmental exposures that young people are more likely to tolerate. Although previous studies have revealed mechanisms of pollutant damage in humans from the molecular level to the individual level, clarifying the relationship between environmental particulate matter (PM) exposure and frailty at the population level is not an easy task because there are two prerequisites to achieve this goal: first, a sample of the study population that is as widely distributed as possible, and second, a precise exposure data of PM that can be linked to the study sample population.

Research findings for environmental impact on agingIn our research, we have used a unique sample of six middle-income countries—China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russian Federation, and South Africa—across four continents to make our study more representative and have used NASA satellite remote sensing data for environmental pollutant exposure assessment. On this basis, we tried to find the evidence connecting long-term exposure to ambient ambient PM2.5—small particles in the air that are 2.5 micrometers (about 1 ten-thousandth of an inch) or less in diameter, which can penetrate deeply into the lung—with frailty in the elderly population. Our findings may reveal two disturbing facts:

Among the six middle-income countries, particulate air pollution is much worse in China and India. Considering China and India account for 37 % of the world’s population, and both populations are aging rapidly, older people in these countries face age-related decline in function that requires special attention. Particulate air pollution is associated with increased risk of frailty, but this association occurs only in rural areas. We do not yet know exactly the cause of this inconsistency—especially with the widespread media coverage of urban pollution in Beijing and New Delhi, for example—but could be related to the type of employment. Public health and policy measures would be crucial in preventing air pollution. Differences in how the policy is implemented and monitored in urban and rural areas may contribute to the differences. On the other hand, healthcare access and supply often differ between urban and rural areas in middle-income countries and may play a role in compensating for health loss caused by environmental pollution.How can we help people live longer in good health?Almost all environmental factors that have a deleterious effect on aging are modifiable, which is very relevant for delaying and reducing frailty through primary prevention measures. If we want to see more people age successfully, if we want to live a longer life in good health, individual-level efforts can make some difference, but over the long haul all that really matters is global coordination to change our current energy mix to reduce pollutant emissions, innovation to promote the widespread use of accessible clean energy, and strong policies to regulate.

May is Air Quality Awareness Month in the United States. While the current global pandemic and major geopolitical events have severely challenged our ambitions in addressing air pollution, it is still an opportunity to encourage people to take positive steps to improve the air quality.

May 2, 2022

Social work in the anti-science era: how to build trust in science-based practice

Over the past five to seven years there has been an increase in anti-science rhetoric and ideas which look to replace the reliance on science with misleading theories and discredit scientific experts. Unfortunately, non-scientific beliefs gained traction during the pandemic and show no signs of slowing. This post-truth and anti-science movement places the field of social work at an important crossroads.

Social workers are expected to explain diagnoses and treatment options to clients and deliver services based on empirical research. Practitioners frequently need to challenge unhealthy behaviors and distorted beliefs which impede clients’ progress. At the mezzo level, we seek to change stereotypical beliefs and inaccuracies about diverse groups based on facts gleaned from research. In addition, social workers advocate for changes or additions in legislation based on findings from science.

But the current skepticism toward scientific research has become entwined with politics, angst, and anger. Many citizens and political leaders have taken a large step back from science and critical thinking because they are following political groups’ opinions of science and truth—or worse social media’s perspectives. Moreover, students are entering social work programs with few critical thinking skills, and an unhealthy distrust and resistance to science and research.

This isn’t a new problem for our field; understanding and using evidence-supported practices has long been debated and students often enter social work programs believing we do little else than use our instincts to “talk to people.”

“But if science isn’t ‘believed’ or valued, then what comes next for professions which are based on science?”

But if science isn’t “believed” or valued, then what comes next for professions which are based on science? Roles like physician, dentist, dietician, and social worker, that apply or practice science—by which I mean evidence-supported assessments and interventions—might not be needed. The field of social work could return to the days of being “friendly visitors” or be discarded for para-professionals.

So, what can be done when clients, students, and politicians are suspicious of and hostile to science, its findings, and the professionals who use it?

Social workers hold key positions in pivotal places to answer questions, educate, clarify, and return value to truth and science. The field of social work will need to make assertive efforts to address these anti-science sentiments and hone our tactics to assist clients, social work students, as well as the public in enhancing their understanding of science and research. Staying silent about anti-science beliefs is not an option, so let’s work together to counter the movement.

Seven strategies social workers can apply to build trust in science-based practiceRemove the veil that hides and mystifies the research process and scientific methods by openly and frequently explaining the process to students, clients, and the public. Discuss the dangers of not using research-supported treatment in service to clients and the benefits of using it. However, avoid arguments, trying to scare, or becoming emotional when you talk with someone who disbelieves science. Try to find common ground.Increase social work students’ critical thinking skills through skill-based activities that teach thinking fallacies and cognitive distortions throughout their curriculum.Re-envision BSW, MSW and Doctoral-level training regarding an emphasis on science and research. We can do this by increasing the number of research studies available, teaching empirically-supported interventions, and focusing on the evidence-based process throughout all programs.Train students, faculty, and social workers to communicate scientific findings clearly with jargon-free language to provide useful and practical public presentations of science (for example, TEDx events, radio, podcasts, YouTube videos, etc.). Give credit to academics for these public presentations towards tenure and promotion.Social work professionals need to stay up-to-date on current theories, assessment, intervention, policies, diversity, and social problems, reading empirical findings and utilizing evidence-supported practices. They need open access and reasonably priced resources.Keep an open-mind to the constant changes in knowledge coming forth via research and recognize that science isn’t free of errors, bias, and/or limitations.Silence and time are not our allies in this struggle, post-truth and anti-science rhetoric are gaining momentum and impact our work and our profession. If the public and clients don’t value science; they won’t value a science-based profession like ours. We can strategically act to re-build trust in science and value in truth. But we will need to work collaboratively, use effective tactics and take action now.

Featured image by Mario Purisic on Unsplash (public domain).

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers